Abstract

The preexistence of immune cells in the tumor microenvironment substantiates the efficacy of immunotherapy in cancer patients. Although the complex intratumoral immune heterogeneity has been extensively studied in single cell resolution, hi-res spatial investigations are limited. In this study, we performed a spatial transcriptome analysis of 4 colorectal adenocarcinoma specimens and 2 paired distant normal specimens to identify the molecular pattern involved in a discontinuous inflammatory response in pathologically annotated cancer regions. Based on the location of spatially varied gene expression, we unmasked the spatially-varied immune ecosystem and identified the locoregional “warmed-up” immune response in predefined “cold” tumor with substantial infiltration of immune components. This “warmed-up” immune profile was found to be associated with the in-situ copy number variance and the tissue remodeling process. Further, “warmed-up” signature genes indicated improved overall survival in CRC patients obtained from TCGA database.

Keywords: Colorectal adenocarcinoma, Mismatch repair, Inflammation, Spatial transcriptomics, Tumor microenvironment

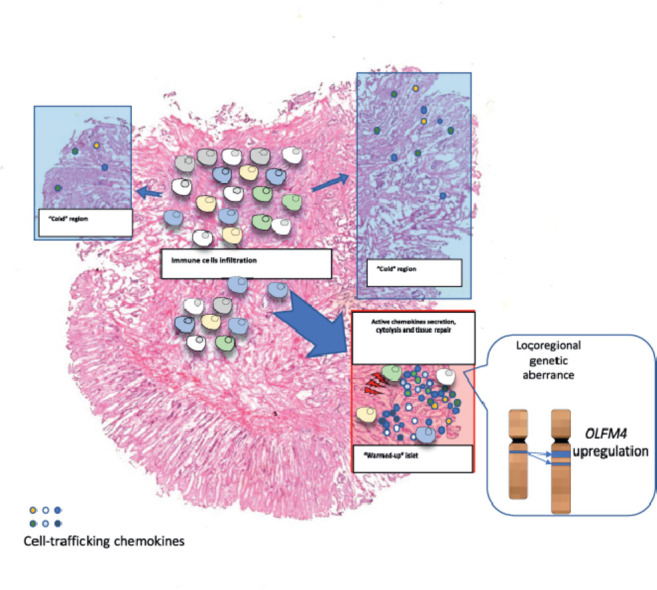

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Cancer is often complicated by unpredictable genetic mutations and surrounding environmental cues that reciprocally interact with cancer cells. Immune components infiltrating into TME leads to “hot” anti-tumor response and hence sensitizes cancer cells to immunotherapy [1,2]. Several studies have shown that a “hot” or “cold” TME is associated with clinical outcomes following immune checkpoint-based immunotherapy [3]. However, majority of the cancer patients exhibits an inadequate response to immunotherapy due to the low tumor mutation burden and insufficient immune cells infiltration [4]. The mismatch repair (MMR) system is a complex consisting of 4 pivotal elements that correct mismatch during DNA replication and recombination. Defects of one or more elements lead to high microsatellite instability (MSI-hi), cause the malfunction of MMR system and ultimately induce oncogenesis [5]. In colorectal cancer (CRC), proficient-MMR/microsatellite stable (pMMR/MSS) tumors show sparse T lymphocyte infiltration, a limited cytolytic cytokine enrichment [6] and worse response to immune checkpoint blockade by anti-Program Death1(PD1) mono-treatment [4,7]. Given that genetic instability is associated with cancer immunogenicity, the distinguished outcome between the dMMR and pMMR cohorts can be primarily attributed to a varied intratumoral immune composition between these two cohorts. Unfortunately, only 15% of CRC patients have a deficiency in the MMR system [8], leaving more than 80% CRC patients insensitive to immunotherapy.

Plate and droplet-based single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) offers the possibility to decipher solid tumor tissue at single-cell resolution. Extensive studies have unfolded the existence and alteration of intratumoral immune cells as common cellular traits across broad types of human cancers [9]. Cancers enriched with immunosuppressive components such as cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAF), tumor-associated macrophages (TAM) and regulatory T cells (Treg) are associated with immune evasion and accelerated disease progression [10], [11], [12], while cancers enriched with cytolytic T lymphocytes (CTL), natural killer cell (NK) and dendritic cells are associated with improved clinical prognosis [9,13,14]. These studies highlight the significance of understanding how immune cells reshape the intratumoral structure in evaluating the response to immunotherapy. However, given that tissue dissociation is required for scRNA-seq, in-depth single-cell transcriptome is obtained at the cost of losing information about spatial distribution of cells. Therefore, it remains unknown if distinct ecosystems could be identified in the same cancer patient.

Stereo-seq is a novel chip-based sequencing technology embedded with spatially-barcoded DNA nanoball, which provides further chance to study the tumor microenvironment in the 2-dimensional coordinate axis [15]. In this study, we spatially resolved transcriptomes of 4 pMMR COAD specimens and 2 paired distant normal tissue at a resolution of 50 µm. In addition, we integrated droplet-based scRNA-seq data to dissect the intratumoral heterogeneity in pMMR tumors, and hence confirmed the presence of a discordant inflammation in pathologically annotated cancer regions. A dMMR-like “warmed-up” reactivity, presented by dMMR-associated immune genes enrichment, was identified in a pMMR tumor. Intriguingly, this “warmed-up” cluster was accompanied by in-situ copy number gain of OLFM4 and the macrophage-mediated tissue remodeling process.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Human patient specimens

COAD tumors and paired distant normal tissues were collected from the surgically resected colon tissues from 6 patients diagnosed with curative adenocarcinoma. Four pairs of fresh specimens were embedded in the optical cutting tissue (OCT) compound (Tissue-Tek, Sakura Finetek USA Inc., Torrance, CA), and then preserved in a -80 °C freezer for stereo-seq. Two tumor specimens were preserved in MACS® Tissue Storage Solution (Miltenyi Biotec, 130-100-008) at 4 °C and then shipped to China National Genebank for scRNA-seq within 24 h.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Cancer Center of SUN YAT-SEN University and the Institutional Review Board of Beijing Genomic Institute (BGI). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients participating in this study before surgical resection.

2.2. Spatial transcriptomics

Spatial transcriptomic analysis was performed on 1 cm 1 cm stereo-chips as previously described [15]. Tissue sections at 10-µm thickness were fixed with methanol at -20 °C for 30 min and then incubated at 37 °C with permeabilization enzyme for 10 min for mRNA capture. After in-situ reverse transcription, the cDNA was released from the stereo-chips for amplification, library construction, and sequencing by MGISEQ-T10. The raw sequencing data were processed as described [15] and mapped to the human genome (hg38). Regions of interest were manually lassoed out for further analysis.

2.3. Single‐cell RNA sequencing

The Tumor Dissociation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec, 130-095-929) was used to prepare a single-cell suspension. The transcriptome of 17,503 cells from 2 COAD patients was generated using BGI droplet-based platform and sequenced by using MGISEQ-T1 instrument at a mean depth of 1,299 genes per cell and 5,652 unique molecular identifier counts per cell. The raw data was processed by BGI-developed scRNA-pipeline and then mapped to the human genome (hg38).

2.4. Computational analysis

Unsupervised cell clustering of scRNA-seq was performed by using Seurat [16]. No batch effect was observed between 2 patients (Fig. S5b). Cell types were annotated manually with the identified cell markers (Fig. 3a). Bayesspace was utilized for spatial transcriptomics clustering [17]. The cluster numbers of each specimen were designated based on the serial negative log-likelihood prediction.

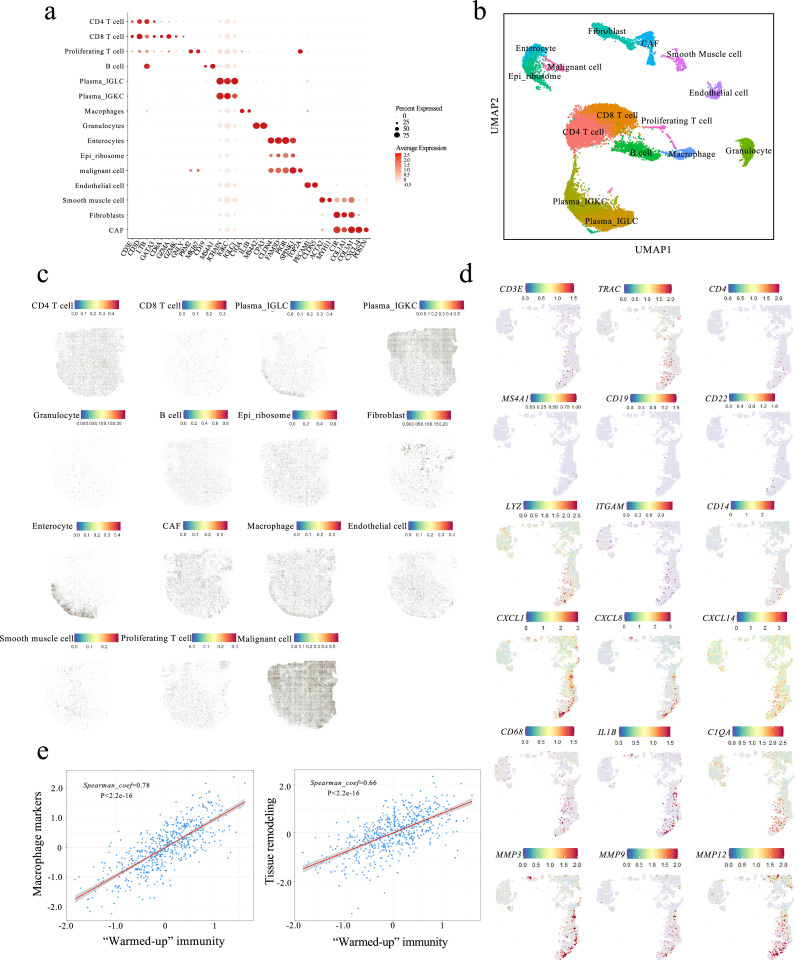

Fig. 3.

“Warmed-up” cluster was enriched with immune cell infiltration. The transcriptomes of 17503 single cells were obtained, clustered and annotated based on the gene expression of interest (a-b). (c) Spotlight projection of single cell distribution onto the spatial map. (d) Transcriptomic map highlighting the representative marker genes. (e) The “Warmed-up” immune genes were positively correlated with macrophage-associated tissue remodeling in 266 COAD patients obtained from TCGA database. The correlation was calculated using Spearman's correlation coefficient.

2.5. Data availability

The processed stereo-seq and single-cell RNA-seq data can be accessed via CNGB Nucleotide Sequence Archive (CNSA: http://db.cngb.org accession number CNP0002432).

3. Results

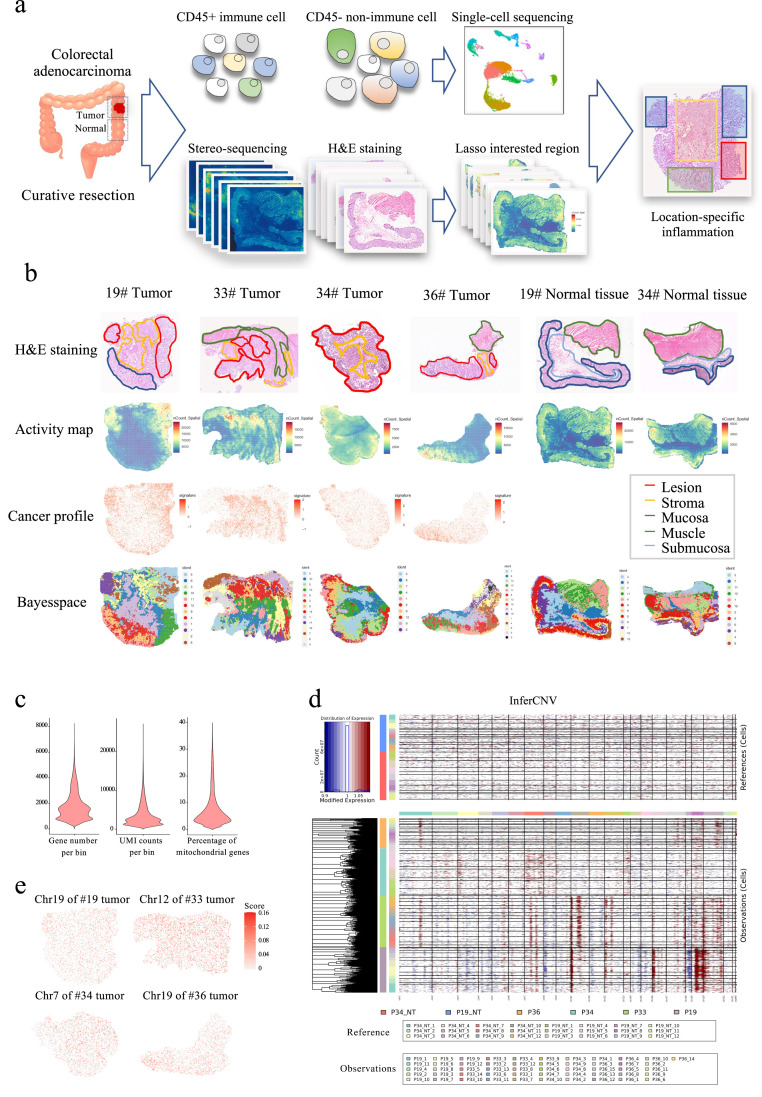

3.1. The interior architecture of COAD is well recapitulated by stereo-seq

The interior transcriptional landscape of the cancer profile was generated via spatial transcriptome of 4 treatment-naive stages II to III COAD specimens and 2 paired distant normal tissues after curative resection (Fig. 1a and b). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was performed to the next serial slide for pathological annotation. On average, approximately ∼1,800 genes were captured by stereo-seq in each of the bin100-defined spots (50 µm 50 µm, Fig. 1c). The average expression of COAD-overexpressed genes including MKI67, E-cadherin (CDH1), epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EPCAM), and keratin (KRT 8/19/20) was plotted to the transcriptomic map as cancer profile (Fig. 1b). The perfect recapitulation of the pathologically annotated cancer region in the spatial transcriptome map suggests the accuracy of in-situ mRNA capture.

Fig. 1.

Stereo-seq illustrating a well recapitulated intratumoral heterogeneity. (a) Schematic graph of the study design. (b) Pathological annotation, transcriptomic activity map, cancer profile and spatial clusters of each examined specimen. The bin size was set to 100 for spatial clustering and downstream analysis. (c) Quality control of spatial transcriptomics. (d) CNV was inferred by setting reference to normal tissues. (e) Accumulative inferCNV score of the designated chromosome was plotted onto the spatial map of each tumor tissue.

A spatially varied transcriptional landscape has been previously described in prostate cancer [18]. To decipher the interior architecture of the COAD tumor, a Bayesian statistical method Bayesspace was used to cluster spatial bins of each specimen [17]. A hi-res pathological annotation-matched cluster was plotted of each tumor and normal tissue section (Fig. 1b and S1). The role of copy number variance (CNV) and rewired transcriptomic landscape has been broadly discussed in the context of oncogenesis [19]. However, the spatial distribution of genetic dysregulation is still poorly understood. Referring to the distant normal tissues, we inferred CNV loss and gain and plotted inferCNV score in each cluster (Fig. 1d). As expected, each specimen exhibited the deviated inferCNV pattern in distinguished chromosome regions. Spatial genetic aberrance was further explored by projecting inferCNV scores of regions of interest within the designated chromosome on the transcriptomic map. The inferCNV deviation was associated with cancer cell distribution as annotated by the pathologists (Fig. 1b and e). Collectively, the above data demonstrated that stereo-seq is a powerful tool that could be leveraged to decipher intratumoral heterogeneity with spatial specificity.

3.2. A treatment‐naive pMMR tumor exhibited discontinuous inflammation in cancer regions

COAD is an epithelial-derived malignancy. To understand the immunological dynamics of COAD, we integrated the mucosa subsets of both cancer and normal specimens and then performed gene ontology (GO) term analysis (Fig. S2b) and gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA, Fig. S2a) for 593 cancer-upregulated genes (Table S1). The malignant mucosa exhibited enhanced mitochondrial activity, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, cellular respiration and neutrophil-involved inflammation (Fig. S2). A recent phase II clinical trial demonstrated that a certain proportion of pMMR CRC patients can also benefit from combinatorial immunotherapy [20], implicating a potential immune response in these pMMR patients. The intratumoral biological process in pMMR tumors was therefore dissected by GO term analysis of differentially expressed genes within each specimen (Fig. 2a and S3). As expected, although each specimen exhibited spatially-distinct biological processes, most examined cancer specimens (3 out of 4) did not show adaptive immune activity in cancer clusters or stromal clusters (Fig. S3). Interestingly, we found that the neutrophil-involved response was enriched in all three cancerous mucosal clusters of patient #19 (Fig. 2a and b). These findings are consistent with a recent study pinpointing that neutrophil infiltration is tilted to luminal margin as opposed to the cancer center [21].

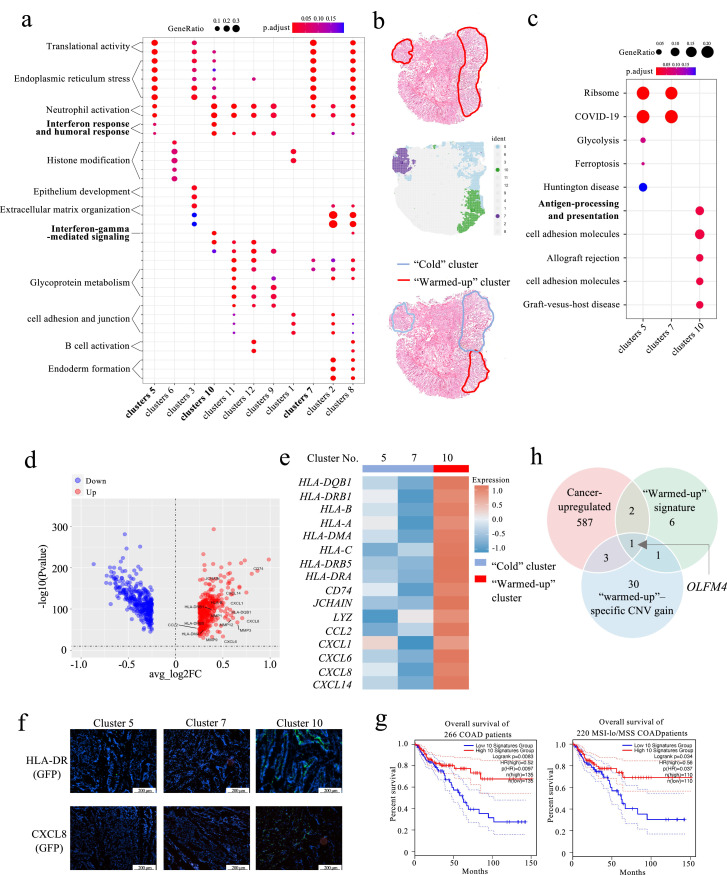

Fig. 2.

A discontinuous inflammatory pattern was observed in the cancer specimens. (a) GO term analysis of spatial clusters demonstrating enhanced interferon-gamma-involved response in cancer cluster 10 over cancer clusters 5 and 7. (b) Spatial cluster (below) recapitulated pathologically-annotated cancer region (up). The “Cold” cluster is marked in blue and the “warmed-up” cluster is marked in red. (c) Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway analysis of the three cancer clusters. Volcano plot (d) and heatmap (e) showed upregulation of the immune-related genes in the “warmed-up” cluster. (f) Representative HLA-DR and CXCL8 immunofluorescence images of regions of interest. The scale bar is set at 200 µm. (g) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of all 266 COAD patients (up) and 220 MSS/MSI-lo patients (below) obtained from the TCGA database. Patients were separated based on the “warmed-up” signature genes expression. (h) Venn plot displaying the intersection among the 593 cancer-upregulated genes, the 10 “warmed-up” signature genes and the 35 genes displaying a “warmed-up”–specific CNV gain.

In addition, we also noticed an upregulated interferon-gamma-related response and enhanced antigen processing and presentation activity in cancer cluster 10 of patient #19, suggesting a locoregional “warmed-up” cytotoxicity against cancer cells (Fig. 2a and c). Differential gene analysis of the “cold” clusters and the “warmed-up” cluster featured chemoattraction, antigen presentation, myeloid cells and B cells engagement, as well as tissue remodeling in cluster 10 (Fig. 2d and e). Human leukocyte antigen – DR isotype (HLA-DR) and interleukin-8 (CXCL8) protein expression were further validated by immunofluorescent staining (Fig. 2f and Table S2). Given that reactive immunity is associated with improved survival in COAD patients, 10 upregulated genes with top fold changes in cluster 10 were selected as “warmed-up” signature and were used to plot the survival curve of 266 COAD patients obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA, 2012) database. The results showed that the patients with a higher “warmed-up” signature exhibited improved survival in all COAD patients (left, p<0.01) and in the MSS/MSI-low cohort (right, p<0.05, Fig. 2g). Further, 8 out of the 16 “warmed-up” immune genes were found significantly upregulated in MSI-hi tumors when compared with MSI-lo and MSS CRC tumors (Fig. S4), suggesting a similarity between dMMR phenotype and “warmed-up” signatures.

Given that the local mutational diversity drives loci-specific immune heterogeneity, our observation incited us to investigate spatially-varied CNV aberrance. By comparing the copy number gain/loss score crossing “warmed-up” and “cold” clusters, we identified 35 genes that showed copy number gain specifically in the “warmed-up” region (Fig. 2h). Moreover, the intersection among the 593 cancer-upregulated genes, the 10 “warmed-up” signature genes and the 35 genes displaying a “warmed-up”–specific CNV gain suggested that copy number gain-mediated olfactomedin 4 (OFLM4) overexpression could be potentially responsible for the inflammatory islet formation (Fig. 2g, S4b and c). This result is consistent with previous findings that OLFM4 is a stemness marker for COAD and is actively secreted in the active inflammatory bowel disease murine model [22], [23], [24].

3.3. Increased immune cell infiltration and enhanced tissue remodeling are locoregionally associated in “warmed‐up” hotspot

We then investigated the immune components identified in the “warmed-up” hotspot. After quality control and filtering, 17,503 single cell transcriptomes were reviewed from 2 COAD tumor specimens by droplet-based scRNA-seq (Fig. S5a and b). From these transcriptomes, a total of 15 cell clusters were identified by unsupervised clustering [16]. Spotlight is a recently released tool to deconvolute spatially-indexed dataset and predict the single-cell distribution [25]. The cell clusters were then projected to transcriptome map of patient #19 by Spotlight (Fig. 3a, b, S5c and d). The cell type specific topic profiles showed consistency across all designated iterations (Fig. S6). Consistent with pathological annotation, the enterocytes were projected onto the normal mucosa region while malignant cancer cells were projected to cancer lesions without “cold” or “warmed-up” discrimination (Fig. 3c). The CD4 T cells, fibroblasts, macrophages and B cells showed increased infiltration within the “warmed-up” lesion when compared with the “cold” lesions (Fig. 3c). This observation was further validated by highlighting marker genes of each cell type (Fig. 3d). Given that chronic inflammation promotes macrophage-mediated tissue remodeling [26], we observed locational upregulation of macrophage markers (complement C1qA Chain (C1QA), interleukin 1β (IL1B), CD68) and tissue remodeling molecules matrix metallopeptidase (MMP) 3/9/12 within the “warmed-up” hotspot. This observation suggests locoregional association between enhanced immunity and the tissue remodeling process. These findings were further confirmed by the strong correlation between the “warmed-up” immune genes and both macrophage and tissue remodeling markers within 594 CRC patients obtained from the TCGA database (PanCancer Atlas, Fig. 3e).

4. Discussion

The concept of spatial immunologic heterogeneity has been previously reported in various cancers including squamous cell carcinoma [27], colorectal cancer and liver metastasis [21,28,29], prostate cancer [30], and lung cancer [31]. These studies described spatially-varied transcriptome and inflammatory molecules within the stromal area, cancer center and stroma-cancer leading edge. Numerous cohort studies identified a link between genomic aberrance and immunogenicity including a dMMR status and increased T cell activity [4,32]. However, few studies evaluated the exhibition of the loci-specific genetic aberrance and distinguished immune infiltration within annotated cancer regions of the same specimen. Since CNV deviation can be inferred by transcriptomic data [33,34], we showed that the copy number gain-mediated OLFM4 overexpression could be potentially causing infiltration of locoregional inflammatory molecules.

The in-depth scRNA-seq procedure requires enzymatic dissociation of the interested tissue, leading to unclear cell distribution within the TME. Given that the cell-to-cell interactions are primarily based on ligand-receptor communication, spatial distance should be taken into consideration when deciphering intercellular crosstalk [35]. For a long time, the lack of a proper tool slowed incorporation of spatial continuity and genome-wide integrity. To overcome this problem in our study, we adopted chip-based spatial transcriptomic approach to unfold the distinct transcriptomic patterns in consecutive tumor sections and profile the non-uniform inflammation into one tumor section.

However, spatial transcriptomics do not offer a comparable depth of sequencing to scRNA-seq. This technology has a maximum capture capability of up to 500 genes in a single cell-sized spot (∼bin20, 10 µm 10 µm) [15], while scRNA-seq can capture up to about 12,000 genes per cell [36]. Therefore, reconstruction of the intratumoral architecture at single cell resolution requires a fine-tuned deconvolution strategy or a precise cell segmentation. In order to pinpoint the single-cell distribution within spatial transcriptomic map, we utilized Spotlight to project the cell profile from the in-house generated scRNA-seq data [25]. The accuracy of prediction was further confirmed by highlighting the representative markers of each cell type.

5. Conclusion

In summary, our study revealed a discontinuous inflammatory pattern in the pathologically annotated cancerous mucosa. We also demonstrated that a “warmed-up” phenotype with enhanced cytokine secretion and upregulated MHC-II molecules expression can be observed in a predefined “cold” tumor. Although the mechanism involved in locoregional gene regulation is still not clear, the initial findings of the inflammatory dynamics indicate that personalized strategy can be involved in the conversion between “cold” tumor and the “warmed-up” tumor. Given that enrichment of immune cells produces an antitumor effect following immunotherapy, our findings may shed lights on the combinatorial immunotherapy development in clinical practices.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest in this work.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82002628), Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2021A1515010096), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2019M660227), Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology Foundation (Y-HR2018-319, Y-L2017-002, and Y-JS2019-009), Sun Yat-sen University Basic Research Fund (19ykpy180), and the open research funds from the Sixth Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, Qingyuan People's Hospital (202011-103).

Biographies

Rongxin Zhang is a deputy chief surgeon of colorectal cancer in Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center. His research interests focus on the clinical efficacy of chemotherapy, immunotherapy, cancer metastasis and related mechanistic study in colorectal cancer. Dr. Zhang also managed 5 research grants including National Natural Science Funds and Guangdong Natural Science Funds.

Yu Feng joined BGI research institute of BGI-Shenzhen as a postdoctoral fellow after obtaining his doctor degree from the Chinese University of Hong Kong. His research interest focuses on tumor microenvironment of hepatocellular carcinoma and colorectal cancer. He has participated in EpiHK project since 2019 and his work has been published by top pioneer-reviewed scientific journals including Sci Trans Med.

Gong Chen is a professor and deputy director at Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center. Dr. Chen is experienced in surgical treatment for abdominal tumors, especially for gastrointestinal tumor and colostomy.

Xun Xu is the director of BGI-Research. His research focuses on the sequencing technologies and applications of sequencing technologies in precision medicine and biodiversity. He has authored or co-authored 242 scientific papers published in top peer-reviewed journals including Nature, Science, and Cell. Dr. Xu has led 15 major national scientific research projects and several international projects.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.fmre.2022.01.036.

Contributor Information

Longqi Liu, Email: Liulongqi@genomics.cn.

Ao Chen, Email: chenao@genomics.cn.

Gong Chen, Email: chengong@sysucc.org.cn.

Xun Xu, Email: xuxun@genomics.cn.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Yang W., Feng Y., Zhou J., et al. A selective HDAC8 inhibitor potentiates antitumor immunity and efficacy of immune checkpoint blockade in hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021;13(588) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaz6804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee N., Zakka L.R., Mihm M.C., Jr., et al. Tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes in melanoma prognosis and cancer immunotherapy. Pathology (Phila) 2016;48(2):177–187. doi: 10.1016/j.pathol.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang H., Qiao J., Fu Y.X. Immunotherapy and tumor microenvironment. Cancer Lett. 2016;370(1):85–90. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arora S., Velichinskii R., Lesh R.W., et al. Existing and emerging biomarkers for immune checkpoint immunotherapy in solid tumors. Adv. Ther. 2019;36(10):2638–2678. doi: 10.1007/s12325-019-01051-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiricny J. The multifaceted mismatch-repair system. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7(5):335–346. doi: 10.1038/nrm1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guidoboni M., Gafa R., Viel A., et al. Microsatellite instability and high content of activated cytotoxic lymphocytes identify colon cancer patients with a favorable prognosis. Am. J. Pathol. 2001;159(1):297–304. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61695-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schrock A., Ouyang C., Sandhu J., et al. Tumor mutational burden is predictive of response to immune checkpoint inhibitors in MSI-high metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2019;30(7):1096–1103. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boland C.R., Goel A. Microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(6):2073–2087. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.064. e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joyce, J.A. and D.T. Fearon, [Special Issue Review] T cell exclusion, immune privilege, and the tumor microenvironment. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Xing F., Saidou J., Watabe K. Cancer associated fibroblasts (CAFs) in tumor microenvironment. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed) 2010;15:166–179. doi: 10.2741/3613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kurahara H., Shinchi H., Mataki Y., et al. Significance of M2-polarized tumor-associated macrophage in pancreatic cancer. J. Surg. Res. 2011;167(2):e211–e219. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tosolini M., Kirilovsky A., Mlecnik B., et al. Clinical impact of different classes of infiltrating T cytotoxic and helper cells (Th1, th2, treg, th17) in patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71(4):1263–1271. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hinshaw D.C., Shevde L.A. The tumor microenvironment innately modulates cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2019;79(18):4557–4566. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-3962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wculek S.K., Cueto F.J., Mujal A.M., et al. Dendritic cells in cancer immunology and immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020;20(1):7–24. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0210-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen, A., S. Liao, K. Ma, et al., Large field of view-spatially resolved transcriptomics at nanoscale resolution. bioRxiv, 2021.

- 16.Satija R., Farrell J.A., Gennert D., et al. Spatial reconstruction of single-cell gene expression data. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015;33(5):495–502. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao E., Stone M.R., Ren X., et al. Spatial transcriptomics at subspot resolution with BayesSpace. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41587-021-00935-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berglund E., Maaskola J., Schultz N., et al. Spatial maps of prostate cancer transcriptomes reveal an unexplored landscape of heterogeneity. Nat. Commun. 2018;9(1):2419. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04724-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mamlouk S., Childs L.H., Aust D., et al. DNA copy number changes define spatial patterns of heterogeneity in colorectal cancer. Nat. Commun. 2017;8(1):1–12. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chalabi M., Fanchi L.F., Dijkstra K.K., et al. Neoadjuvant immunotherapy leads to pathological responses in MMR-proficient and MMR-deficient early-stage colon cancers. Nat. Med. 2020;26(4):566–576. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0805-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pelka K., Hofree M., Chen J.H., et al. Spatially organized multicellular immune hubs in human colorectal cancer. Cell. 2021;184(18) doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.08.003. 4734-4752 e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gersemann M., Becker S., Nuding S., et al. Olfactomedin-4 is a glycoprotein secreted into mucus in active IBD. J. Crohn’s Colitis. 2012;6(4):425–434. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van der Flier L.G., Haegebarth A., Stange D.E., et al. OLFM4 is a robust marker for stem cells in human intestine and marks a subset of colorectal cancer cells. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(1):15–17. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oh H.-K., Tan A.L.-K., Das K., et al. Genomic loss of miR-486 regulates tumor progression and the OLFM4 antiapoptotic factor in gastric cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011;17(9):2657–2667. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-3152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elosua-Bayes M., Nieto P., Mereu E., et al. SPOTlight: seeded NMF regression to deconvolute spatial transcriptomics spots with single-cell transcriptomes. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 2021;49(9):e50. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bosurgi L., Cao Y.G., Cabeza-Cabrerizo M., et al. Macrophage function in tissue repair and remodeling requires IL-4 or IL-13 with apoptotic cells. Science. 2017;356(6342):1072–1076. doi: 10.1126/science.aai8132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ji A.L., Rubin A.J., Thrane K., et al. Multimodal analysis of composition and spatial architecture in human squamous cell carcinoma. Cell. 2020;182(2):497–514. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.039. e22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu Y., Yang S., Ma J., et al. Spatiotemporal immune landscape of colorectal cancer liver metastasis at single-cell level. Cancer Discov. 2021 doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-0316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bindea G., Mlecnik B., Tosolini M., et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics of intratumoral immune cells reveal the immune landscape in human cancer. Immunity. 2013;39(4):782–795. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berglund E., Maaskola J., Schultz N., et al. Spatial maps of prostate cancer transcriptomes reveal an unexplored landscape of heterogeneity. Nat. Commun. 2018;9(1):1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04724-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jia Q., Wu W., Wang Y., et al. Local mutational diversity drives intratumoral immune heterogeneity in non-small cell lung cancer. Nat. Commun. 2018;9(1):1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07767-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Overman M.J., Ernstoff M.S., Morse M.A. American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book; 2018. Where We Stand with Immunotherapy in Colorectal Cancer: Deficient Mismatch Repair, Proficient Mismatch Repair, and Toxicity Management; pp. 239–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patel A.P., Tirosh I., Trombetta J.J., et al. Single-cell RNA-seq highlights intratumoral heterogeneity in primary glioblastoma. Science. 2014;344(6190):1396–1401. doi: 10.1126/science.1254257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang L., Li Z., Skrzypczynska K.M., et al. Single-cell analyses inform mechanisms of myeloid-targeted therapies in colon cancer. Cell. 2020;181(2):442–459. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.048. e29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Asp M., Bergenstråhle J., Lundeberg J. Spatially resolved transcriptomes—next generation tools for tissue exploration. Bioessays. 2020;42(10) doi: 10.1002/bies.201900221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Picelli S., Faridani O.R., Björklund Å.K., et al. Full-length RNA-seq from single cells using Smart-seq2. Nat. Protoc. 2014;9(1):171–181. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The processed stereo-seq and single-cell RNA-seq data can be accessed via CNGB Nucleotide Sequence Archive (CNSA: http://db.cngb.org accession number CNP0002432).