Corresponding Author

Key words: familial hypercholesterolemia, polygenic risk score, preventive cardiology

Since the Framingham Heart Study, the cardiovascular community has focused on identifying those at risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) to prevent myocardial infarction, stroke, and death. Identifying those at risk offers the opportunity to adopt lifestyle changes and use medications to mitigate ASCVD. In the United States, the most used risk prediction tool is the pooled cohort equations of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology. This risk calculator encompasses traditional risk factors (age, sex, blood pressure, smoking, diabetes, and lipid levels) but not others (eg, lipoprotein(a), inflammatory diseases, pre-eclampsia, family history, and socioeconomic status). Furthermore, the pooled cohort equations are only validated for middle-aged patients over the intermediate term (10 years), are not well validated in many race/ethnicities and fail to identify those at risk of ASCVD early in life, prior to onset of risk factors (“primordial prevention”).

Polygenic risk scores (PRSs) are powerful tools to predict risk of ASCVD. PRSs are derived from a weighted sum of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that increase or decrease risk of ASCVD. PRS performance has improved dramatically from initial efforts tallying a handful of SNPs,1 now incorporating millions of SNPs, even below traditional levels of significance of genome-wide association studies.2,3 Current PRSs are as good or better than traditional risk factors at predicting ASCVD.2 Because many of the ASCVD-associated SNPs influence risk independent of traditional risk factors, a PRS generally improves clinical risk prediction, even after adjusting for traditional risk factors.2,3

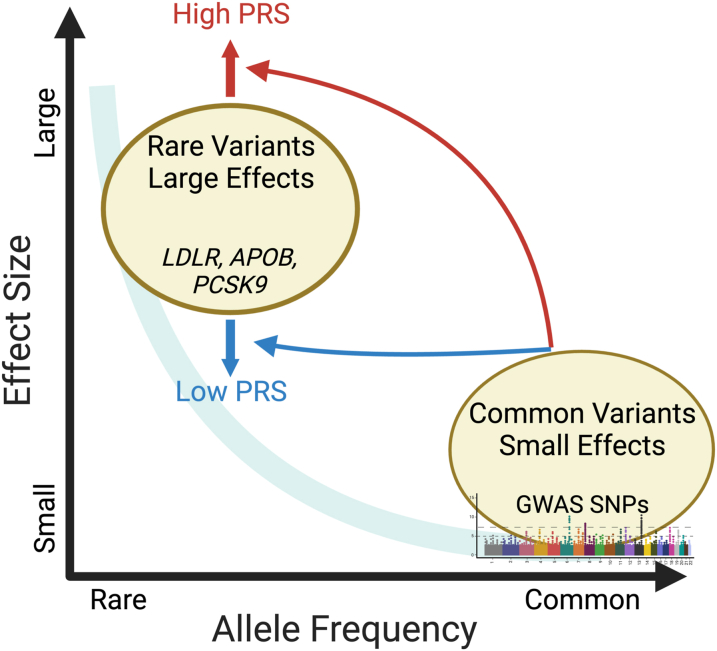

Although individuals have millions of SNPs contributing to disease risk, individual SNPs typically have small effect sizes (ie, odds ratios of <1.05) (Figure 1). This contrasts with large effects (ie, odds ratio of >3) from rare alleles causing Mendelian diseases. For instance, heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (HeFH) is caused by rare variants in LDLR, APOB, and PCSK9, which dramatically increase both low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-c) and risk of ASCVD. Beyond single pathogenic variants in patients with HeFH, the effect of polygenic risk of ASCVD is only partly understood. Among individuals with HeFH carrying known pathogenic mutations, the phenotypic spectrum of both LDL-c and ASCVD is quite heterogenous, suggesting that polygenic risk could further modify ASCVD risk in HeFH.4

Figure 1.

Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms Vary in Population Frequency and Magnitude of Effect

Rare variants tend to have larger effects, whereas common variants tend to have smaller effects. PRSs can alter the risk of CAD among individuals with pathogenic variants for HeFH. This figure was generated using BioRender. CAD = coronary artery disease; GWAS = genome-wide association studies; HeFH = heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia; PRS = polygenic risk score; SNP = single nucleotide polymorphism.

In this issue of JACC: Advances, Reeskamp et al5 examined the impact of a PRS for coronary artery disease (CAD) on individuals with HeFH harboring known pathogenic variants. The authors combined 2 cohorts from the Dutch National HeFH cascade screening program and the UK Biobank (UKBB) to form the largest study of genetically verified HeFH (n = 1,744). Within the Dutch National HeFH screening program, the authors demonstrate that a recently published PRS for CAD6 further stratifies the risk of incident CAD in individuals with HeFH, as measured by 1.35 HR/SD, a common PRS metric. HeFH carriers in the highest PRS quintile had the double the event rates (9.3 vs 4.2 per 1,000 person-years) relative to the lowest quintile, corresponding to nearly triple the risk of CAD (HR: 3.37 vs 1.24). The PRS was independently associated with risk of incident CAD after adjustment for untreated LDL-c, hypertension, diabetes, and obesity. Addition of the PRS to a risk model encompassing age, sex, and the first 5 principal components of ancestry did not increase CAD risk prediction in these HeFH patients, as assessed by the C-statistic, but power was limited given the available sample size and event rate. In the UKBB cohort, HeFH individuals at the highest PRS quintile had double the event rate for incident CAD relative to those at the lowest quintile (14.0 vs 6.8 per 1,000 person-years). Within the UKBB, addition of the PRS to a full clinical model slightly improved risk discrimination among those with HeFH (0.024 increase in the C-statistic).

This work by Reeskamp et al7 adds growing evidence that polygenic variants influence disease risk even among those with “Mendelian” genetic diseases. A PRS has been shown to improve risk discrimination of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer,8 Lynch syndrome,8 11 rare genetic diseases,9 hypertrophic cardiomyopathy,10 and 8 metabolic disorders.11 There has been prior work on the impact of a PRS on risk of ASCVD in much smaller HeFH cohorts. Fahed et al8 showed that among 56 individuals with pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants for HeFH, a PRS improved risk discrimination of CAD (OR/SD of 2.31). Additionally, Trinder et al4 show that among 275 patients with monogenic HeFH, a PRS for LDL-c significantly increased risk of premature cardiovascular disease (HR: 3.06) relative to controls. While the authors achieve parity with regard to sex (53% female), the genetic uniformity of the study population (93% European) make generalizability of the results in more diverse populations challenging.12

What, then, is clinical utility of a PRS in the setting of HeFH? Both U.S. and European guidelines recommend aggressive, lipid-lowering therapy among patients with HeFH.13,14 As demonstrated by Reeskamp et al7 and others,4,8 addition of a PRS may provide additional risk stratification for those with HeFH. As more clinical genetic testing for HeFH utilizes whole genome sequencing, PRSs can be derived simultaneously with standard analysis of LDLR, APOB, and PCSK9, thereby providing a more comprehensive risk assessment. This may be especially useful for patients with very high polygenic risk to trigger earlier prescription of and improved adherence to aggressive lipid lowering.7,15 Other strategies that need to be evaluated could include using a high PRS in HeFH patients to trigger earlier targeted use of imaging to detect subclinical plaque to guide antiplatelet use or to identify children or young adults that might benefit from very aggressive lifestyle modifications and lipid-lowering therapies.16 On the other hand, for the majority of HeFH patients with average or low polygenic risk, a PRS may not “de-risk” HeFH patients enough to withhold therapy given a 2- to 10-fold higher risk of early onset ASCVD.17

Funding support and author disclosures

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number F32HL165854 (to Dr Palmisano), the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers R01DK120565 (to Dr Knowles), R01DK106236 (to Dr Knowles), R01DK107437 (to Dr Knowles), P30DK116074 (to Dr Knowles), and the American Diabetes Association under award number 1-19-JDF-108 (to Dr Knowles). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

References

- 1.Kathiresan S., Melander O., Anevski D., et al. Polymorphisms associated with cholesterol and risk of cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1240–1249. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inouye M., Abraham G., Nelson C.P., et al. Genomic risk prediction of coronary artery disease in 480,000 adults: implications for primary prevention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:1883–1893. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.07.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel A.P., Wang M., Ruan Y., et al. A multi-ancestry polygenic risk score improves risk prediction for coronary artery disease. Nat Med. 2023;29:1793–1803. doi: 10.1038/s41591-023-02429-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trinder M., Li X., DeCastro M.L., et al. Risk of premature atherosclerotic disease in patients with monogenic versus polygenic familial hypercholesterolemia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:512–522. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reeskamp L.F., Shim I., Dron J.S., et al. Polygenic background modifies risk of coronary artery disease among individuals with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. JACC: Adv. 2023;2 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aragam K.G., Jiang T., Goel A., et al. Discovery and systematic characterization of risk variants and genes for coronary artery disease in over a million participants. Nat Genet. 2022;54:1803–1815. doi: 10.1038/s41588-022-01233-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knowles J.W., Zarafshar S., Pavlovic A., et al. Impact of a genetic risk score for coronary artery disease on reducing cardiovascular risk: a pilot randomized controlled study. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2017;4:53. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2017.00053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fahed A.C., Wang M., Homburger J.R., et al. Polygenic background modifies penetrance of monogenic variants for tier 1 genomic conditions. Nat Commun. 2020;11:3635. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17374-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oetjens M.T., Kelly M.A., Sturm A.C., Martin C.L., Ledbetter D.H. Quantifying the polygenic contribution to variable expressivity in eleven rare genetic disorders. Nat Commun. 2019;10:4897. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12869-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biddinger K.J., Jurgens S.J., Maamari D., et al. Rare and common genetic variation underlying the risk of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a National Biobank. JAMA Cardiol. 2022;7:715. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2022.1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodrich J.K., Singer-Berk M., Son R., et al. Determinants of penetrance and variable expressivity in monogenic metabolic conditions across 77,184 exomes. Nat Commun. 2021;12:3505. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-23556-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clarke S.L., Assimes T.L., Tcheandjieu C. The propagation of racial disparities in cardiovascular genomics research. Circ Genomic Precis Med. 2021;14 doi: 10.1161/CIRCGEN.121.003178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mach F., Baigent C., Catapano A.L., et al. 2019 ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:111–188. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grundy S.M., Stone N.J., Bailey A.L., et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(24):e285–e350. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kullo I.J., Jouni H., Austin E.E., et al. Incorporating a genetic risk score into coronary heart disease risk estimates: effect on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels (the MI-GENES clinical trial) Circulation. 2016;133:1181–1188. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.020109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marston N.A., Kamanu F.K., Nordio F., et al. Predicting benefit from evolocumab therapy in patients with atherosclerotic disease using a genetic risk score: results from the FOURIER trial. Circulation. 2020;141:616–623. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.043805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khera A.V., Won H.-H., Peloso G.M., et al. Diagnostic yield and clinical utility of sequencing familial hypercholesterolemia genes in patients with severe hypercholesterolemia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:2578–2589. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]