Abstract

Background

Maternal hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDPs) are strongly associated with offspring congenital heart defects.

Objectives

This study assessed whether infants exposed to maternal HDPs were also more likely to have subtle cardiac structural and functional abnormalities than unexposed infants.

Methods

We used regression analyses to compare: 1) left ventricular parameters from conventional echocardiography performed in infants from the Copenhagen Baby Heart Study born to mothers with preeclampsia, gestational hypertension (GH), or no HDP; and 2) advanced echocardiographic parameters for 545 term infants born to mothers with preeclampsia and 545 matched infants not exposed to HDPs.

Results

Compared with infants unexposed to HDPs (n = 17,384), infants exposed to preeclampsia (n = 754) had a thicker interventricular septum in end-diastole (adjusted mean difference [± SD] 0.05 [±0.02] mm; P = 0.004), thicker left ventricular posterior wall (0.04 [±0.02] mm; P = 0.009), larger left ventricular internal diameter (0.12 [±0.06] mm; P = 0.04), and larger left ventricular volume (0.21 [±0.10] mL; P = 0.03). Systolic function changes included increased fractional shortening (0.36% [±0.14%]; P = 0.01) and stroke volume (0.18 [±0.07] mL; P = 0.006), whereas diastolic function changes included lower transmitral early peak inflow velocity (−1.76 [±0.49] mL; P = 0.0003), lower mitral annulus lateral wall a' (−0.21 [±0.09] cm/s; P = 0.02), and smaller lateral E/e’ (−1.06 [±0.38] cm/s; P = 0.005). Conversely, there was little evidence of any association between maternal GH (n = 469) and offspring left ventricular parameters.

Conclusions

Maternal preeclampsia, but not GH, was associated with subtle newborn cardiac morphological and functional alterations, including thickening of the left ventricular myocardium and altered systolic and diastolic function.

Key words: echocardiography, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, infants, preeclampsia, risk factors

Central Illustration

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDPs), including gestational hypertension (GH), preeclampsia, and eclampsia, affect approximately 10% of pregnancies.1 Preeclampsia has been associated with offspring congenital heart defects (CHDs).2, 3, 4 In a Danish study, the association was consistent across CHD subtypes and across pregnancies, with the strongest associations observed for early preterm preeclampsia (onset <34 weeks’ gestation),4 suggesting that maternal mechanisms link preeclampsia and offspring CHD.

GH is defined as incident hypertension beginning ≥20 weeks’ gestation in the absence of additional preeclampsia-defining features.1,5 Whether GH is also associated with offspring CHDs is unclear; the previously mentioned Danish study found little evidence of any association between GH and offspring CHDs of any type.4

Maternal preeclampsia is associated with elevated umbilical cord and child serum levels of potential markers of fetal cardiac damage in infants without CHDs.6, 7, 8 These findings suggest that maternal preeclampsia could also be associated with subtle changes in offspring cardiac structure and function, but this has never been studied systematically in a large cohort of unselected infants. We used the Copenhagen Baby Heart Study (CBHS) echocardiographic data to investigate the extent to which maternal preeclampsia and GH are associated with left ventricular structural and functional parameters evaluated using conventional and advanced echocardiography.

Methods

Copenhagen Baby Heart Study

The CBHS is a prospective, population-based cohort study of cardiac structure and function from birth onward in children born at the 3 main maternity wards in the Copenhagen metropolitan area, Denmark, between April 2016 and October 2018. A description of the CBHS’ design and a cohort profile have previously been published.9,10 Data on the pregnancy, delivery, parental health, family history of disease, and lifestyle factors were collected from medical records. Clinical examination of each infant included transthoracic echocardiography performed according to a standardized protocol.9 Of the 27,595 infants in the CBHS, 25,590 (92.7%) had usable transthoracic echocardiography data from an examination performed within 60 days of delivery.

Study cohorts

For analyses of parameters obtained using conventional echocardiography, the study cohort included all CBHS participants with an echocardiographic scan acquired within 60 days of delivery and available maternal obstetric information. For analyses of parameters obtained via advanced echocardiography, the study cohort included 545 infants who were born at term (gestational age ≥37 weeks) after pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia and whose echocardiograms permitted tissue Doppler imaging (TDI), speckle-tracking echocardiography (STE) analyses, or both (89.6% of 608 term infants exposed to maternal preeclampsia). These 545 infants were then matched 1:1 with infants born at term after pregnancies without preeclampsia or GH. Infants were matched on sex, singleton/twin pregnancy, gestational age at birth (±maximum 5 days), age at echocardiography (±maximum 3 days), and weight (±maximum 200 g).

Maternal HDP (exposure)

For infants born at 2 of the 3 participating hospitals (Rigshospitalet and Hvidovre Hospital), information on maternal HDP was obtained from an obstetric database maintained by the obstetrics departments. This database includes data registered by midwives during and after labor and delivery and discharge diagnoses provided by obstetricians and senior midwives. Database information shows excellent agreement with medical chart information (kappa coefficients 0.7-1.0).11 For infants born at the third hospital (Herlev Hospital), the obstetric database was incomplete. As a result, obstetric information was only available for 1,752 (19.4%) of 9,011 CBHS participants enrolled at this hospital. We defined maternal preeclampsia and GH as registration with one of the following International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision, codes: preeclampsia, O14.0-O14.2 or O15.0-O15.9; GH, O13.9.

Infant left ventricular cardiac parameters (outcome)

The protocol used on all children included subxiphoid, apical, left parasternal, and suprasternal views acquired with cardiac sector transducers 12S-D and 6S-D using Vivid E9 ultrasound equipment (General Electric, Horten, Norway).9 Conventional echocardiographic measurements were obtained in accordance with the American Society of Echocardiography’s guidelines for pediatric echocardiography12 and validated by a separate team of analysts (see Supplemental Material 1 for details). The following left ventricular parameters were ascertained from 2-dimensional (2D) echocardiography in the parasternal long-axis view: interventricular septal end-diastolic thickness (IVSd), left ventricular posterior wall end-diastolic thickness, left ventricular internal diameter in end-diastole (LVIDd), left ventricular internal diameter in end-systole (LVIDs). End-diastolic and end-systolic volume, fractional shortening, and stroke volume were calculated by the GE Vivid 9 system using Teichholz’s formulas. Transmitral flow velocities were measured using pulsed-wave Doppler in the apical 4-chamber view. Peak flow velocities during early diastole (peak E wave) and atrial contraction (peak A wave), as well as the mitral valve E wave deceleration time, were measured according to guidelines.12

Advanced analyses were performed off-line by a single physician (R.O.B.V.) using EchoPAC software, version 113 (GE Healthcare Danmark A/S). Parameters derived from off-line color TDI included average peak systolic (s’), early diastolic (e’), and late diastolic (a’) myocardial velocities at both the lateral mitral annulus and the basal interventricular septum, whereas parameters derived from the STE analyses included peak midline systolic strain (peak S) and peak midline global strain (peak G). Supplemental Material 2 and Supplemental Table 1 provide details of the methods used to derive TDI and STE parameters.

Unrealistic outliers in outcome parameter values were removed in a 2-step procedure: 1) removing measurements >10 SDs from the mean; and 2) subsequently removing measurements >5 SDs from the recalculated mean.

Covariates

We obtained information on maternal height, weight, prepregnancy body mass index, parity, smoking, and comorbidities and the child’s gestational age at birth, birthweight and length, Apgar score, and birth method (planned/acute cesarean section, spontaneous/assisted vaginal delivery) from the hospitals’ obstetric database. Maternal comorbidities of interest included prepregnancy diabetes (International Classification of Diseases-10 codes E10.0-E11.9, O24.0, O24.1, O24.5), cardiomyopathy (I42.0-I42.9), Marfan syndrome (Q87.4), and any CHD (Q20.0-Q26.9, Q89.3).

Statistical analyses

Parameters from conventional (2D) echocardiography

In our main analyses, we used a linear mixed model to compare left ventricular structural and functional parameters in infants born to mothers with preeclampsia, mothers with GH but no preeclampsia, and mothers with no HDPs. Analyses were adjusted for child sex as a categorical variable and for the linear effects of gestational age at birth (days), birth length (centimeters), birthweight (grams), and age at transthoracic echocardiography (days) as continuous variables. To account for correlation among observations made by each individual echocardiograph analyst (see Supplemental Material 1 for details), random effects of analyst and month of examination within analyst were also included in the model.

We also evaluated the association between maternal HDPs and extreme left ventricular parameter values using binomial models. If the effect estimate from the linear mixed model (described previously) was negative, we evaluated the association between maternal preeclampsia or GH and left ventricular parameter values ≤5th percentile. If the main effect estimate was positive, we evaluated the association with left ventricular parameter values ≥95th percentile. The dichotomous outcomes were analyzed using generalized estimating equation models with a logit link function and a compound symmetry covariance matrix allowing measurements to be correlated within analyst and within month of examination for each analyst. The analyses were adjusted for the same covariates as the main analyses.

Parameters from advanced echocardiography

We used multiple linear regression to compare TDI- and STE-derived measurements from infants born at term after pregnancies complicated with preeclampsia with measurements from the matched group of infants born at term after pregnancies not complicated by maternal HDPs. We also evaluated the association between maternal preeclampsia and extreme values of the advanced echocardiographic parameters, dichotomized as described for the conventional parameters, using logistic regression. Both linear and logistic regression models were adjusted for the matching variables: child sex, singleton/twin, gestational age at birth (days), birthweight (grams), and age in days at echocardiography.

Sensitivity analyses

To test the robustness of the associations observed in the main analyses between maternal preeclampsia or GH and conventional echocardiography parameters, we conducted a number of sensitivity analyses. To test whether the observed associations might be explained by maternal or offspring CHDs, we repeated the analyses excluding infants with CHDs diagnosed by CBHS echocardiography (see footnote to Table 1 for a list of defects) and mothers with CHDs. Pregestational diabetes is a risk factor for HDPs, especially preeclampsia,16 and maternal prepregnancy diabetes has been associated with increased risks of offspring CHDs.17 To ensure that our results reflected only the association of maternal HDPs with infant cardiac parameters, we repeated our analyses after further excluding infants born to women with pregestational diabetes. Finally, to assess how much the observed estimates were affected by adjustment variables measured at or after birth, we assessed the associations adjusting only for child sex.

Table 1.

Maternal Delivery and Offspring Characteristics for Infants Born to Mothers With Preeclampsia (N = 754), Gestational Hypertension (N = 469), and No Hypertensive Disorder of Pregnancy (N = 17,384) in the Copenhagen Baby Heart Study, Denmark, 2016 to 2018

| Maternal Hypertensive Disorder of Pregnancy |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preeclampsia | Gestational Hypertension | No Hypertensive Disorder of Pregnancy | |

| Maternal characteristics | |||

| Maternal age at delivery (y) | |||

| <25 | 36 (4.8) | 16 (3.4) | 717 (4.1) |

| 25-29 | 230 (30.5) | 122 (26.0) | 4,845 (27.9) |

| 30-34 | 292 (38.7) | 201 (42.9) | 7,099 (40.8) |

| 35-39 | 145 (19.2) | 97 (20.7) | 3,757 (21.6) |

| ≥40 | 51 (6.8) | 33 (7.0) | 966 (5.6) |

| Maternal prepregnancy BMIa | |||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 17 (2.3) | 11 (2.3) | 692 (4.0) |

| Normal weight (18.5-24.9) | 421 (55.8) | 225 (48.0) | 12,350 (71.0) |

| Preobese (25.0-29.9) | 163 (21.6) | 124 (26.4) | 3,032 (17.4) |

| Obese I (30.0-34.9) | 87 (11.5) | 66 (14.1) | 859 (4.9) |

| Obese II/III (≥35.0) | 61 (8.1) | 40 (8.5) | 351 (2.0) |

| Missing | 5 (0.7) | <5 | 100 (0.6) |

| Maternal race | |||

| White | 624 (82.8) | 376 (80.2) | 14,411 (82.9) |

| Black | 6 (0.8) | <5 | 174 (1.0) |

| Asian | 34 (4.5) | 16 (3.4) | 720 (4.1) |

| Otherb | 10 (1.3) | 5 (1.1) | 252 (1.5) |

| Missing | 80 (10.6) | 69 (14.7) | 1,827 (10.5) |

| Smoking during pregnancyc | |||

| Nonsmoker | 254 (33.7) | 181 (38.6) | 6,431 (37.0) |

| Current smoker | 5 (0.7) | 5 (1.1) | 279 (1.6) |

| Former smoker | 78 (10.3) | 51 (10.9) | 1,620 (9.3) |

| Missing | 417 (55.3) | 232 (49.5) | 9,054 (52.1) |

| Parity (live birth or stillbirth >20 wk) | |||

| 0 | 573 (76.0) | 336 (71.6) | 10,160 (58.4) |

| 1 | 147 (19.5) | 104 (22.2) | 5,481 (31.5) |

| 2 | 28 (3.7) | 22 (4.7) | 1,455 (8.4) |

| ≥3 | 5 (0.7) | 7 (1.5) | 288 (1.7) |

| Missing | <5 | <5 | <5 |

| Mode of delivery | |||

| Vaginal delivery | 320 (42.4) | 258 (55.0) | 10,130 (58.3) |

| Cesarean section | 220 (29.2) | 82 (17.5) | 2,727 (15.7) |

| Missing | 214 (28.4) | 129 (27.5) | 4,527 (26.0) |

| Newborn characteristics | |||

| Child sex | |||

| Male | 388 (51.5) | 243 (51.8) | 8,933 (51.4) |

| Female | 366 (48.5) | 226 (48.2) | 8,451 (48.6) |

| Gestational age at birth (wk) | |||

| <34 | 27 (3.6) | <5 | 134 (0.8) |

| 34-36 | 119 (15.8) | 19 (4.1) | 654 (3.8) |

| 37 | 146 (19.4) | 52 (11.1) | 953 (5.5) |

| 38 | 150 (19.9) | 104 (22.2) | 2,279 (13.1) |

| 39 | 126 (16.7) | 102 (21.7) | 3,573 (20.6) |

| 40 | 113 (15.0) | 107 (22.8) | 5,043 (29.0) |

| 41 | 69 (9.2) | 80 (17.1) | 4,251 (24.5) |

| ≥42 | <5 | <5 | 497 (2.9) |

| Birthweight (g) | |||

| <2,000 | 43 (5.7) | <5 | 130 (0.7) |

| 2,000-2,499 | 98 (13.0) | 25 (5.3) | 470 (2.7) |

| 2,500-2,999 | 172 (22.8) | 75 (16.0) | 2,096 (12.1) |

| 3,000-3,499 | 231 (30.6) | 180 (38.4) | 5,797 (33.3) |

| 3,500-3,999 | 144 (19.1) | 133 (28.4) | 6,164 (35.5) |

| ≥4,000 | 65 (8.6) | 54 (11.5) | 2,726 (15.7) |

| Missing | <5 | <5 | <5 |

| Weight for gestational age and sexd | |||

| <3rd percentile | 89 (11.8) | 25 (5.3) | 554 (3.2) |

| 3rd-9th percentile | 87 (11.5) | 46 (9.8) | 1,399 (8.0) |

| 10th-90th percentile | 521 (69.1) | 362 (77.2) | 13,995 (80.5) |

| >90th percentile | 56 (7.4) | 36 (7.7) | 1,434 (8.2) |

| Missing | <5 | <5 | <5 |

| Birth length (cm) | |||

| <45.0 | 47 (6.2) | <5 | 152 (0.9) |

| 45-49.9 | 231 (30.6) | 103 (22.0) | 2,465 (14.2) |

| 50-54.9 | 418 (55.4) | 331 (70.6) | 13,061 (75.1) |

| ≥55 | 49 (6.5) | 33 (7.0) | 1,646 (9.5) |

| Missing | 9 (1.2) | <5 | 60 (0.3) |

| Body surface area at birthe | |||

| <0.1 | <5 | 0 (0) | 9 (0.1) |

| 0.1-0.19 | 234 (31.0) | 69 (14.7) | 1,737 (10.0) |

| 0.2-0.29 | 509 (67.5) | 400 (85.3) | 15,576 (89.6) |

| ≥0.3 | <5 | <5 | <5 |

| Missing | 9 (1.2) | <5 | 60 (0.3) |

| 5-min Apgar score ≤7 | |||

| Yes | 13 (1.7) | 5 (0.9) | 133 (0.8) |

| No | 740 (98.1) | 463 (98.7) | 17,236 (99.1) |

| Missing | <5 | <5 | 15 (0.1) |

| Need for resuscitation at birth | |||

| Yes | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 11 (0.1) |

| No | 752 (99.7) | 469 (100) | 17,364 (99.9) |

| Missing | <5 | 0 (0) | 9 (0.1) |

| Congenital heart defectsf | |||

| Yes | 48 (6.4) | 28 (6.0) | 1,222 (7.0) |

| No | 706 (93.6) | 411 (94.0) | 16,162 (93.0) |

| Missing | - | - | - |

Values are n (%).

Apgar = appearance, pulse, grimace, activity, and respiration; BMI = body mass index.

Defined according to World Health Organization’s obesity criteria.13

Other race is defined as mixed origin and races not included in the categories mentioned earlier.

First-trimester smoking, as reported to the midwife.

Marsal formula.14

Haycock formula.15

Congenital heart defects: atrial septal defects, ventricular septal defects, bicuspid aortic valve, aortic stenosis, pulmonary stenosis, quadricuspid aortic valve, quadricuspid pulmonary valve, coarctation of the aorta, tetralogy of Fallot, transposition of the great arteries, atrioventricular septal defect, congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries, situs inversus, Epstein’s anomaly, cardiac tumors, supradiaphragmatic total anomalous pulmonary venous return.

Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC).

Written consent was obtained from the parents of all participants included in the CBHS. The CBHS (NCT02753348) complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee of the Capital City Region of Denmark (H-16001518) and the Danish Data Protection Agency (I-Suite No. 04546, ID-No. HGH-2016-53).

Results

Associations for infant left ventricular cardiac parameters assessed using conventional echocardiography

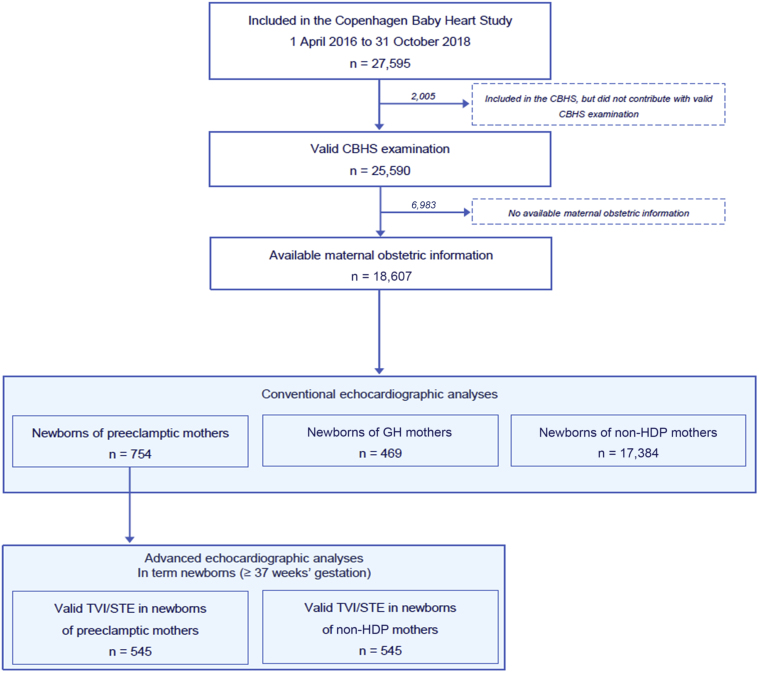

In the analyses of conventional echocardiographic parameters, our cohort included 754 infants born to mothers with preeclampsia, 469 infants born to mothers with GH, and 17,384 infants born to mothers with neither preeclampsia nor GH (Figure 1). Table 1 shows maternal, pregnancy, delivery, and newborn characteristics of the cohort by maternal disease status. Compared with infants whose mothers did not have HDPs, there was a greater prevalence of maternal nulliparity and maternal preobesity or obesity among infants born to mothers with preeclampsia or GH. Infants exposed to maternal preeclampsia were more likely to have been delivered by cesarean section and to have been born preterm (<37 weeks’ gestation); consequently, there were also proportionally more infants with lower birthweights (<3,000 g), shorter birth lengths (<50 cm), and smaller body surface areas (<0.2) among infants born to mothers with preeclampsia.

Figure 1.

Study Cohorts

Flow chart illustrating the generation of the study cohort from the Copenhagen Baby Heart Study, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016 to 2018.

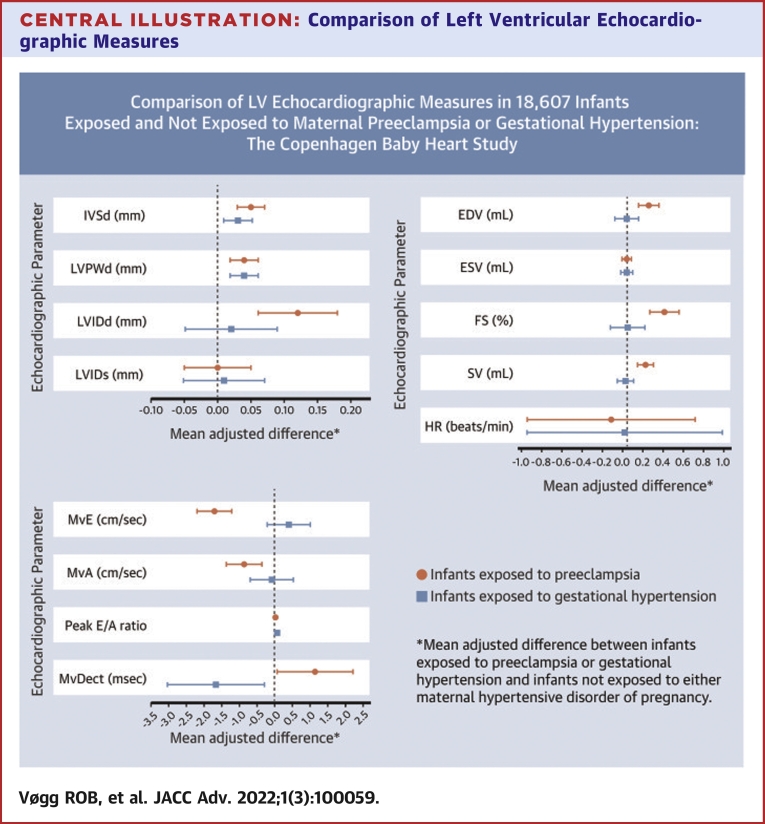

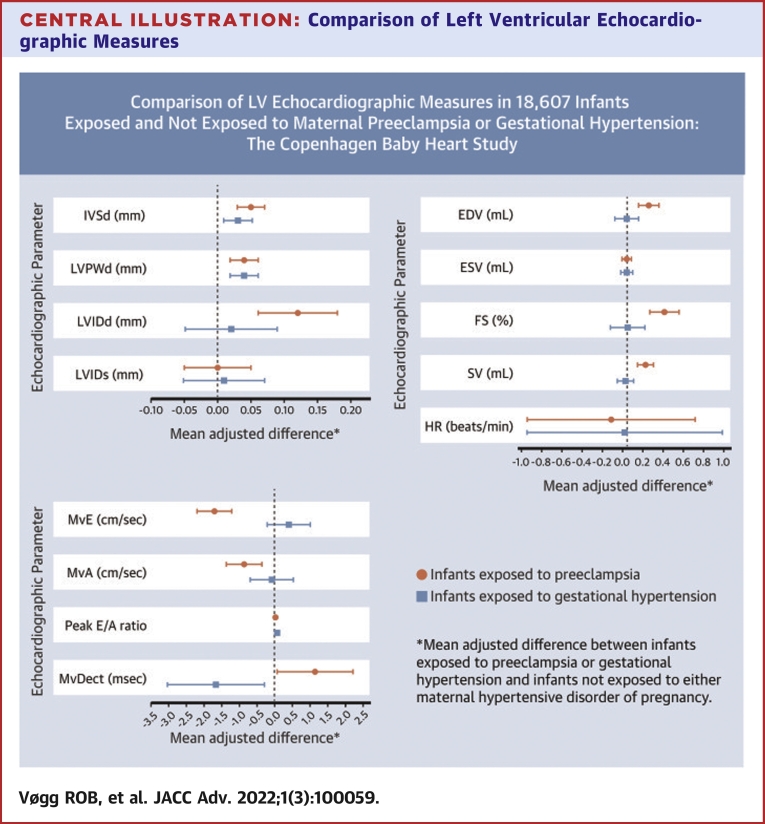

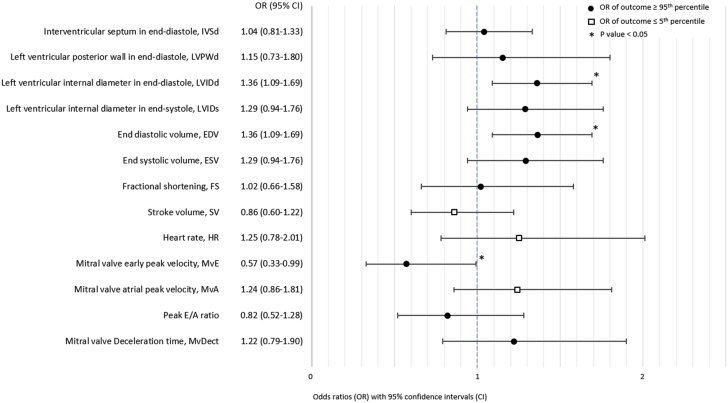

The details of infant left ventricular parameters measured using conventional echocardiography are summarized in Supplemental Table 2. Associations between maternal disease status and these parameters are presented in the Central Illustration and Table 2. Compared with infants born to mothers without HDPs, infants exposed to maternal preeclampsia had significantly thicker left ventricular walls with thicker IVSd and thicker left ventricular posterior wall end-diastolic thickness. LVIDd was significantly larger in the children of mothers with preeclampsia, as was end-diastolic volume. LVIDs and end-systolic volume measures showed little evidence of an association with maternal preeclampsia. Infants exposed to preeclampsia also had significantly larger measures of systolic function (fractional shortening and stroke volume), although heart rate did not differ for exposed infants. In terms of diastolic function, maternal preeclampsia was associated with reduced transmitral early peak inflow velocity, and transmitral atrial peak inflow velocity tended to be reduced. Mitral valve E wave deceleration time was not affected by maternal preeclampsia. There was little evidence of an association between maternal GH and any of the left ventricular structural or functional parameters measured using conventional echocardiography (Central Illustration, Table 2).

Central Illustration.

Comparison of Left Ventricular Echocardiographic Measures

Mean adjusted differences comparing left ventricular measures in newborns exposed to maternal preeclampsia (n = 754) or gestational hypertension (n = 469) with those in newborns not exposed to hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (n = 17,384) in a cohort of 18,607 infants from the Copenhagen Baby Heart Study, Denmark, 2016 to 2018. EDV = end-diastolic volume; ESV = end-systolic volume; FS = fractional shortening; HR = heart rate; IVSd = interventricular septal thickness at end-diastole; LVIDd = left ventricular internal diameter at end-diastole; LVIDs = left ventricular diameter at end-diastole; LVPWd = left ventricular posterior wall thickness at end-diastole; MvA = transmitral atrial peak inflow velocity; MvDect = mitral valve deceleration time; MvE = transmitral peak inflow velocity; SV = stroke volume.

Table 2.

Comparison of Left Ventricular Measures in Newborns Exposed to Maternal Preeclampsia (N = 754) or Gestational Hypertension (N = 469) With Those in Newborns Not Exposed to Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy (N = 17,384) in a Cohort of 18,607 Infants From the Copenhagen Baby Heart Study, Denmark, 2016 to 2018

| Infants Born to Mothers With Preeclampsia |

Infants Born to Mothers With Gestational Hypertension |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Adjusted Difference [±SE] | P Value | Mean Adjusted Difference [±SE] | P Value | |

| Left ventricular structure | ||||

| Interventricular septal thickness at end-diastole (mm) | 0.05 [±0.02] | 0.004 | 0.03 [±0.02] | 0.17 |

| Left ventricular posterior wall thickness at end-diastole (mm) | 0.04 [±0.02] | 0.01 | 0.04 [±0.02] | 0.05 |

| Left ventricular internal diameter at end-diastole (mm) | 0.12 [±0.06] | 0.04 | 0.02 [±0.07] | 0.77 |

| Left ventricular internal diameter at end-diastole (mm) | 0.00 [±0.05] | 0.99 | 0.01 [±0.06] | 0.92 |

| Systolic function | ||||

| End-diastolic volume (mL)a | 0.21 [±0.10] | 0.03 | 0.00 [±0.11] | 1.00 |

| End-systolic volume (mL)a | 0.00 [±0.04] | 0.97 | 0.00 [±0.05] | 0.95 |

| Fractional shortening (%)a | 0.36 [±0.14] | 0.01 | 0.01 [±0.16] | 0.95 |

| Stroke volume (mL)a | 0.18 [±0.07] | 0.01 | −0.01 [±0.08] | 0.85 |

| Heart rate (beats per min) | −0.14 [±0.80] | 0.86 | −0.02 [±0.94] | 0.98 |

| Diastolic function | ||||

| Transmitral early peak inflow velocity (cm/s) | −1.76 [±0.49] | 0.0003 | 0.38 [±0.61] | 0.53 |

| Transmitral atrial peak inflow velocity (cm/s) | −0.90 [±0.50] | 0.07 | −0.11 [±0.62] | 0.86 |

| Peak E/A ratio | −0.01 [±0.01] | 0.51 | 0.02 [±0.01] | 0.18 |

| Mitral valve deceleration time (ms) | 1.12 [±1.09] | 0.31 | −1.69 [±1.38] | 0.22 |

Reference group: infants born to mothers without hypertensive disorder of pregnancy.

All estimates adjusted for child sex, gestational age at birth, age in days at time of examination, birth weight and length, and random effects of echocardiographic analyst and month of examination.

Calculated using Teichholz formula.

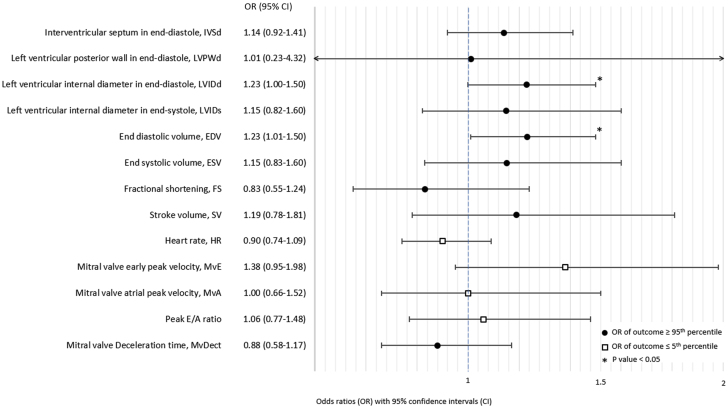

Infants exposed to maternal preeclampsia were more likely than infants born to mothers without HDPs to have extremely large (≥95th percentile) values of LVIDd (odds ratio: 1.23; 95% CI: 1.00-1.50) (Figure 2) and, consequently, end-diastolic volume, as this parameter is calculated based on LVIDd. There was also the suggestion of associations between maternal preeclampsia and extremely large IVSd values (odds ratio: 1.14; 95% CI: 0.92-1.41) and extremely small transmitral early peak inflow velocity values (odds ratio: 1.38; 95% CI: 0.95-1.98). Otherwise, there was little evidence of an association between maternal preeclampsia and extreme values of the other left ventricular measurements (Figure 2). Maternal GH was also associated with extremely large values of LVIDd (odds ratio: 1.36; 95% CI: 1.09-1.69) and end-diastolic volume and with extremely small values of transmitral early peak inflow velocity (odds ratio: 0.57; 95% CI: 0.33-0.99; Figure 3). Infants exposed to maternal GH also tended to have extremely large values of LVIDs (odds ratio: 1.29; 95% CI: 0.94-1.76) and therefore also end-systolic volume. There was little evidence of an association between maternal GH and extreme values of other left ventricular measurements (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Associations Between Maternal Preeclampsia and Extreme Offspring Values of Conventional Echocardiographic Parameters

Odds ratios for extreme values of conventional echocardiographic parameters (values ≤5th or ≥95th percentile) comparing infants born to mothers with preeclampsia and infants born to mothers without hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. The direction of the effect estimate from the main analyses (linear mixed models) determined whether the ≤5th or ≥95th percentile was evaluated.

Figure 3.

Associations Between Maternal Gestational Hypertension and Extreme Offspring Values of Conventional Echocardiographic Parameters

Odds ratios for extreme values of conventional echocardiographic parameters (values ≤5th or ≥95th percentile) comparing infants born to mothers with gestational hypertension and infants born to mothers without hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. The direction of the effect estimate from the main analyses (linear mixed models) determined whether the ≤5th or ≥95th percentile was evaluated.

Associations with infant left ventricular cardiac parameters assessed using advanced echocardiography

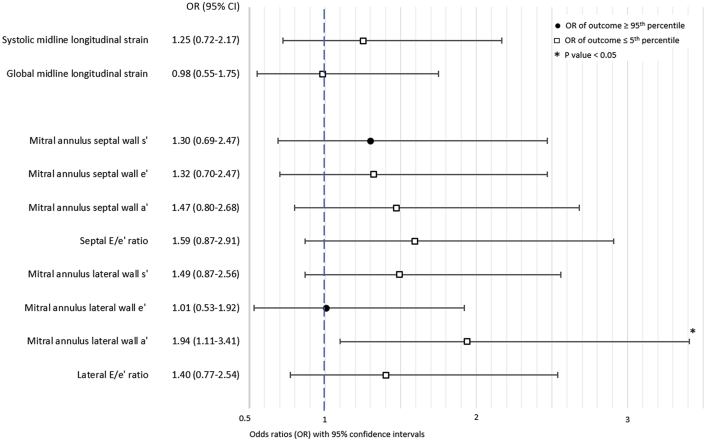

The details of infant left ventricular strain parameters measured using advanced echocardiography are summarized in Supplemental Table 3. Table 3 shows associations between maternal preeclampsia and these parameters. There was little evidence of an association between maternal preeclampsia and either systolic or global midline longitudinal strain in the infant heart. In contrast, compared with children born to mothers without HDPs, infants exposed to preeclampsia had significantly lower velocities of the mitral annulus lateral wall a’ and smaller lateral and septal E/e’ ratios. However, none of the other measures of left ventricular tissue velocity was associated with exposure to maternal preeclampsia.

Table 3.

Comparison of Advanced Left Ventricular Measures in 545 Term Infants Exposed to Maternal Preeclampsia and 545 Matched Term Infants Whose Mothers Did Not Have Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy From the Copenhagen Baby Heart Study, Denmark, 2016 to 2018

| Mean Adjusted Difference [±SE] | P Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Speckle-tracking echocardiography | ||

| Systolic midline longitudinal strain (%) | −0.12 [±0.16] | 0.45 |

| Global midline longitudinal strain (%) | −0.06 [±0.16] | 0.69 |

| Tissue Doppler imaging | ||

| Mitral annulus septal wall s' (cm/s) | 0.004 [±0.04] | 0.92 |

| Mitral annulus septal wall e' (cm/s) | −0.02 [±0.06] | 0.79 |

| Mitral annulus septal wall a' (cm/s) | −0.13 [±0.07] | 0.07 |

| Septal E/e’ ratio | −0.55 [±0.28] | 0.05 |

| Mitral annulus lateral wall s' (cm/s) | −0.08 [±0.04] | 0.07 |

| Mitral annulus lateral wall e' (cm/s) | 0.04 [±0.08] | 0.63 |

| Mitral annulus lateral wall a' (cm/s) | −0.21 [±0.09] | 0.02 |

| Lateral E/e’ ratio | −1.06 [±0.38] | 0.01 |

Infants born at term (≥37 weeks’ gestation) to mothers with preeclampsia were matched 1:1 with infants born at term to mothers with no hypertensive disorder of pregnancy on the following: sex, singleton/twin pregnancy, gestational age at birth (≤±5 days), age at echocardiography (≤±3 days), and weight (≤±200 g). If weight at birth for newborns of mothers with preeclampsia was not available, weight at examination was used for both the exposed and unexposed infant in the matched pair.

When looking at extreme values of parameters derived from TDI and STE analyses, infants exposed to preeclampsia were almost twice as likely to have an extremely low mitral annulus lateral wall a’ velocity (≤5th percentile), compared with infants born to mothers without HDPs (odds ratio: 1.95; 95% CI: 1.11-3.42) (Figure 4). There was little evidence of an association between maternal preeclampsia and extreme values of other left ventricular strain measurements.

Figure 4.

Associations Between Maternal Preeclampsia and Extreme Offspring Values of Advanced Echocardiographic Parameters

Odds ratios for extreme values of advanced echocardiographic parameters (values ≤5th or ≥95th percentile) comparing infants born at term to mothers with preeclampsia and matched infants born at term to mothers without hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. The direction of the effect estimate from the main analyses (linear regression models) determined whether the ≤5th or ≥95th percentile was evaluated.

Sensitivity analyses

Adjusting only for child sex changed most of our findings dramatically, illustrating the importance of adjusting for variables related to the child’s age and size (Supplemental Table 4, Supplemental Figures 1 and 2). Restricting the cohort to infants born to mothers without diabetes did not materially change our results for conventional echocardiographic parameters (Supplemental Table 5). Similarly, excluding infants born to mothers with CHDs affected our results very little (Supplemental Table 6). Restricting to newborns without CHDs attenuated the estimates for children exposed to preeclampsia but had no material influence in children exposed to GH (Supplemental Table 7). Excluding infants exposed to maternal diabetes or maternal CHDs and infants who themselves had CHDs had little effect on the results for advanced echocardiographic parameters (Supplemental Table 8).

Discussion

In this large population-based cohort study, infants exposed to maternal preeclampsia were more likely than infants born to mothers without HDPs to exhibit signs of myocardial remodeling, particularly thickening of the left ventricular walls. Infants born to mothers with preeclampsia also had increased left ventricular diastolic volumes but similar systolic volumes and, consequently, increased systolic function. They also had decreased peak inflow velocities, suggesting compromised ventricular relaxation with diastolic impairment. In contrast, there was little evidence of an association between maternal GH and changes to infant cardiac morphology and function.

Increases in left ventricular myocardial thickness, fractional shortening, and stroke volume observed in infants exposed to preeclampsia might reflect an adaptation of the fetal heart to the increased resistance in the placental arteries described in preeclampsia.18 Increased placental vascular resistance affects fetal cardiac loading conditions, leading to increased fetal cardiac afterload, which has ultimately been suggested to influence fetal cardiac function and cause mild myocardial dysfunction already in fetal life.19

Studies of the association between maternal preeclampsia or GH and newborn cardiac structure and systolic function assessed by conventional echocardiography are limited and have had small sample sizes (maximum 80 preeclampsia-exposed children).20,21 Breatnach et al21 found left ventricular systolic dysfunction with significantly lower ejection fraction within 48 hours of birth in infants born at term to mothers with GH, compared with infants born to healthy mothers, which contrasts with our findings of larger fractional shortening in infants exposed to preeclampsia but not in infants exposed to GH. Aye et al20 found that although left and right ventricular masses were similar at birth in infants born at term after pregnancies with preeclampsia, GH, and no HDP, respectively, right ventricular end-diastolic volume was smaller in infants exposed to HDPs, preeclampsia in particular.

Associations between maternal HDP and diastolic function in infants have also only been studied in small numbers of children (maximum 53 HDP-exposed children).8,22 Narin et al8 found lower peak A-wave and peak E/A ratio among infants exposed to preeclampsia when they examined neonates within 24 hours of birth. Cetinkaya et al22 observed reduced left ventricular end-diastolic dimensions and signs of diastolic dysfunction (smaller peak E-wave, peak A-wave, and peak E/A ratio) 1 to 3 days after delivery in infants exposed to preeclampsia and born prematurely, compared with infants born to normotensive mothers. We also observed a smaller pressure gradient between the left atrium and left ventricle (smaller peak E-wave) in infants exposed to preeclampsia. Pulsed-wave Doppler analyses of mitral valve inflow velocities are sensitive to ventricular relaxation and compliance as well as atrial pressure. In the adult heart, a stiff ventricle (due to, eg, left ventricular hypertrophy, fibrosis, or infiltrations) impairs early left ventricular filling, leading to decreased E wave magnitudes. Similarly, the decrease in peak E wave we observed in newborns exposed to preeclampsia may reflect increased thickness (and correspondingly increased stiffness) of the left ventricular myocardium in these infants.

Strain reflects myocardial systolic function more directly than conventional cavity-based echocardiographic parameters, which are also insensitive to early changes in myocardial function, making STE useful for assessing potential subclinical differences in infant cardiac structure.23,24 Breatnach et al21 demonstrated that infants born to mothers with GH exhibited diminished left ventricular function as reflected by decreased deformation and left ventricular global longitudinal strain and twist values. In contrast, we found no differences in systolic or global midline longitudinal strain for children born at term to mothers with and without preeclampsia.

The average differences in cardiac parameters between exposed and unexposed infants in our study were modest in absolute terms but should be considered relative to the size of infant cardiac structures. For instance, a 0.1 mm increase in IVSd translates to a relative increase of 5%. Whether these subtle structural and functional cardiac differences, observed in a cohort of asymptomatic infants, have any clinical impact or prognostic importance later in life, is currently unknown. Children exposed to maternal HDPs are at increased risk of hypertension and cardiovascular events,25,26 and previous studies reported associations between maternal HDPs and offspring cardiac morphology and function in older children,27,28 suggesting that the cardiac changes we observed shortly after birth in infants exposed to maternal preeclampsia may persist and even worsen later in childhood. One study found signs of concentric hypertrophy with increased left ventricular wall thickness and reduced left ventricular end-diastolic volume in adolescents exposed to maternal preeclampsia,27 in agreement with our finding of larger left ventricular walls in exposed infants but contrasting with the small increase in end-diastolic volume we observed. In contrast, Fugelseth et al28 found that at 5 to 8 years of age, children exposed to preeclampsia had significantly smaller hearts, with smaller end-diastolic left ventricular lengths measured from apex to mitral valve, and increased heart rates. However, in line with our findings, they also observed increased late diastolic velocity (a’ wave) at mitral attachments on TDI in the offspring of mothers with preeclampsia. Conversely, a small study of the association between maternal HDPs and left ventricular mass in preadolescents and adolescents found no difference between exposed and unexposed children.29

Peak a' velocity is a function of atrial contraction. Contrary to e’ and E/e’, a’ is not regularly used as a clinical marker of diastolic function, nor has it been investigated as thoroughly. Our finding of a reduced lateral wall a' suggests that a' may be valuable in the assessment of diastolic function in children born to mothers with preeclampsia.

Follow-up examinations are crucial to determine whether the subtle structural and functional changes observed at birth persist, resolve, or worsen as the children age and to advance our understanding of the long-term cardiovascular health of the offspring of women with preeclampsia. The CBHS is currently conducting follow-up examinations on the children exposed to preeclampsia to investigate whether the differences in cardiac structure and function observed at birth persist through childhood.

Strengths and potential limitations

Our cohort’s unprecedented size allowed us to detect small between-group differences, which is crucial when evaluating structures as small as the infant heart. The study cohort was drawn from a large population-based study that offered echocardiography to all infants born in the Copenhagen metropolitan area in a specified time period, reducing the risk of selection bias. The echocardiography analysts had no knowledge of maternal preeclampsia or GH status, minimizing the risk of ascertainment bias.

An evaluation of intra- and inter-observer variability in the CBHS’ echocardiographic data showed good intra- and inter-observer agreement in image acquisition for most 2D parameters and good measurement reliability and agreement for most imaging modalities.30 To minimize variability in left ventricular measurements from the parasternal long-axis view, a specially trained team validated all 2-dimensional left ventricular measurements in the 25,590 echocardiographic examinations performed by the CBHS. To further account for any variability among analysts, we adjusted our analyses for the random effects of echocardiography analyst and month of examination. Any variability added by either the sonographer or the validation team was expected to be random because they were blinded to maternal HDP status.

STE-derived measurements have high reproducibility and provide accurate and angle-independent measurements of left ventricular dimensions and strain.31 In this study, STE analyses were based only on the apical 4-chamber view, as the CBHS’ standard echocardiographic protocol did not include apical 2- and 3-chamber views. In the adult myocardium, localized areas of fibrosis or regional ischemia are the most common reasons for regional variance in ventricular performance. Because such regional dysfunction is unlikely in newborns, the 4-chamber view was considered sufficient to produce accurate representations of strain.

Infants exposed to preeclampsia were well represented in the CBHS, but infants born preterm, particularly very premature infants, were underrepresented.10 Consequently, infants born to women with preterm (early onset) preeclampsia were underrepresented in our study and therefore our results may not be generalizable to such infants. Furthermore, because the vast majority of infants were born to Caucasian women, our study was not powered to examine whether race/ethnicity modified the observed associations, and our results may not be generalizable to populations of other ethnicity.

Sensitivity analyses adjusting only for child sex yielded results that were markedly different from the fully adjusted results. Children born to mothers with HDPs were more often delivered preterm, had lower birthweights, smaller birth lengths, and smaller body surface areas. Estimates unadjusted for these factors were heavily influenced by these differences between exposed and unexposed infants, underlining the importance of accounting for the normal physiological effects of age and size on cardiac measurements, particularly in rapidly growing infants.

The results from sensitivity analyses excluding mothers with pregestational diabetes or CHDs suggested that these maternal conditions could not explain the observed associations. However, excluding infants with CHDs attenuated the results for some parameters assessed using conventional echocardiography. Preeclampsia is associated with offspring CHDs,2, 3, 4 and the decrease in effect magnitudes seen in the sensitivity analyses could reflect the removal of the structural and functional consequences such defects have for the infant heart.

Conclusions

In the largest population-based cohort of infants examined to date, we showed that maternal preeclampsia is associated with subtle cardiac morphological and functional alterations in infants. Our results suggest that exposure to preeclampsia may be associated with signs of preclinical cardiac dysfunction, including thickening of the left ventricular myocardium, increased left ventricular end-diastolic internal diameter and volume, and altered systolic function, even in asymptomatic newborns.

Funding support and author disclosures

This Copenhagen Baby Heart sub-study was supported by the Danish Heart Foundation, the Lundbeck Foundation, King Christian X's Foundation, Carl and Ellen Hertz' Foundation for Danish Medical and Natural Sciences, and the Hede Nielsen Family Foundation. Dr Boyd was supported by a grant from the Novo Nordisk Foundation. The funders played no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of manuscripts; or in decisions to publish results. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

PERSPECTIVES.

COMPETENCY IN MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE: Not only do offspring exposed to maternal preeclampsia have increased risks of hypertension and cardiovascular disease in adulthood, they are also more likely to have subtle cardiac structural and functional abnormalities at birth than infants born to mothers without HDPs.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK: Whether there is a link between disease in adult life and the subclinical alterations in cardiac structure and function already present at birth in children exposed to preeclampsia is unknown. Further research should explore the impact of exposure to maternal preeclampsia on cardiac health through childhood and young adulthood and determine whether these offspring would benefit from increased clinical attention starting in childhood.

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

Appendix

For supplemental material, tables, and figures, please see the online version of this paper.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Brown M.A., Magee L.A., Kenny L.C., et al. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: ISSHP classification, diagnosis, and management recommendations for international practice. Hypertension. 2018;72:24–43. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.10803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Auger N., Fraser W., Healy-Profitós J., Arbour L. Association between preeclampsia and congenital heart defects. JAMA. 2015;314:1588–1598. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.12505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brodwall K., Leirgul E., Greve G., et al. Possible common aetiology behind maternal preeclampsia and congenital heart defects in the child: a cardiovascular diseases in Norway project study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2016;30:76–85. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyd H.A., Basit S., Behrens I., et al. Association between fetal congenital heart defects and maternal risk of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Circulation. 2017;136:39–48. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy Hypertension in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:1122–1131. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000437382.03963.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akil A., Api O., Can E.O., et al. Does preeclampsia have any adverse effect on fetal heart? J Matern Neonatal Med. 2016;29:2312–2315. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2015.1085013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karadeniz L., Coban A., Ince Z., Turkoglu U., Can G. Cord blood cardiac troponin T and nonprotein-bound iron levels in newborns of mild pre-eclamptic mothers. Neonatology. 2010;97:305–310. doi: 10.1159/000255162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Narin N., Çetin N., Kiliç H., et al. Diagnostic value of troponin T in neonates of mild pre-eclamptic mothers. Biol Neonate. 1999;75:137–142. doi: 10.1159/000014089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sillesen A.S., Raja A.A., Pihl C., et al. Copenhagen Baby Heart Study: a population study of newborns with prenatal inclusion. Eur J Epidemiol. 2018;34:79–90. doi: 10.1007/s10654-018-0448-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vøgg R.O.B., Basit S., Raja A.A., et al. Cohort profile: the Copenhagen Baby Heart Study (CBHS) Int J Epidemiol. 2022;50:1778–1779m. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyab147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brixval C.S., Thygesen L., Johansen N., et al. Validity of a hospital-based obstetric register using medical records as reference. Clin Epidemiol. 2015;7:509–515. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S93675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lai W.W., Geva T., Shirali G.S., et al. Guidelines and standards for performance of a pediatric echocardiogram: a report from the task force of the Pediatric Council of the American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2006;19:1413–1430. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.WHO/Europe | Nutrition - body mass index - BMI. https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/nutrition/a-healthy-lifestyle/body-mass-index-bmi

- 14.Marsál K., Persson P.H., Larsen T., Lilja H., Selbing A., Sultan B. Intrauterine growth curves based on ultrasonically estimated foetal weights. Acta Paediatr. 1996;85:843–848. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1996.tb14164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haycock G.B., Schwartz G.J., Wisotsky D.H. Geometric method for measuring body surface area: a height-weight formula validated in infants, children, and adults. J Pediatr. 1978;93:62–66. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(78)80601-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bartsch E., Medcalf K.E., Park A.L., Ray J.G. Clinical risk factors for preeclampsia determined in early pregnancy: systematic review and meta-analysis of large cohort studies. BMJ. 2016;353:i1753. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Øyen N., Diaz L., Leirgul E., et al. Prepregnancy diabetes and offspring risk of congenital heart disease: a nation-wide cohort study. Circulation. 2016;133:2243–2253. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.017465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Papageorghiou A.T., Yu C.K.H., Nicolaides K.H. The role of uterine artery Doppler in predicting adverse pregnancy outcome. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;18:383–396. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Api O., Emeksiz M.B., Api M., Ugurel V., Unal O. Modified myocardial performance index for evaluation of fetal cardiac function in preeclampsia. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;33:51–57. doi: 10.1002/uog.6272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aye C.Y.L., Lewandowski A.J., Lamata P., et al. Prenatal and postnatal cardiac development in offspring of hypertensive pregnancies. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.014586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Breatnach C.R., Monteith C., McSweeney L., et al. The impact of maternal gestational hypertension and the use of anti-hypertensives on neonatal myocardial performance. Neonatology. 2018;113:21–26. doi: 10.1159/000480396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cetinkaya M., Bostan Ö., Köksal N., Semizel E., Özkan H., Cakır S. Early left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in premature infants born to preeclamptic mothers. J Perinat Med. 2011;39:89–95. doi: 10.1515/jpm.2010.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsai H.R., Gjesdal O., Wethal T., et al. Left ventricular function assessed by two-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography in long-term survivors of Hodgkin’s lymphoma treated by mediastinal radiotherapy with or without anthracycline therapy. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:472–477. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pislaru C., Abraham T.P., Belohlavek M. Strain and strain rate echocardiography. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2002;17:443–454. doi: 10.1097/00001573-200209000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kajantie E., Eriksson J.G., Osmond C., Thornburg K., Barker D.J.P. Pre-eclampsia is associated with increased risk of stroke in the adult offspring the Helsinki birth cohort study. Stroke. 2009;40:1176–1180. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.538025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palmsten K., Buka S.L., Michels K.B. Maternal pregnancy-related hypertension and risk for hypertension in offspring later in life. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:858–864. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f3a1f9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Timpka S., Macdonald-Wallis C., Hughes A.D., et al. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and offspring cardiac structure and function in adolescence. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.003906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fugelseth D., Ramstad H.B., Kvehaugen A.S., Nestaas E., Støylen A., Staff A.C. Myocardial function in offspring 5-8 years after pregnancy complicated by preeclampsia. Early Hum Dev. 2011;87:531–535. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Himmelmann A., Svensson A., Hansson L. Five-year follow-up of blood pressure and left ventricular mass in children with different maternal histories of hypertension: the Hypertension in Pregnancy Offspring Study. J Hypertens. 1994;12:89–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sillesen A.S., Pihl C., Raja A.A., et al. Repeatability and reproducibility of neonatal echocardiography: the Copenhagen Baby Heart Study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2019;32:895–905. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2019.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amundsen B.H., Helle-Valle T., Edvardsen T., et al. Noninvasive myocardial strain measurement by speckle tracking echocardiography: validation against sonomicrometry and tagged magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:789–793. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.