Abstract

This theory-guided review draws on 30 years of published data to examine and interrogate the current and future state of pain disparities research. Using the Hierarchy of Health Disparity Research framework, we present an overview of “three generations” of pain disparities scholarship, while proposing directions for adopting a “fourth generation” that redefines, explains, and theorizes future pain disparities research in a diverse society. Prior research has focused on describing the scope of disparities, and throughout the historical context of human existence, racialized groups have been subjected to inadequate pain care. It is imperative that research not only illuminates existing problems but also provides solutions that can be implemented and sustained across varying social milieus. We must invest in new theoretical models that expand on current perspectives and ideals that position all individuals at the forefront of justice and equity in their health.

Keywords: pain, health disparities, pain research, Black Americans, equity, Hierarchy of Health Disparity Research

Introduction

The high prevalence of chronic pain has become a national public health crisis, concurrent with the opioid and racism epidemics in the United States (U.S.). In the U.S., approximately 50 million adults report chronic pain, and 20 million report high-impact chronic pain (i.e., pain that highly interferes with function and activities) (Dahlhamer et al., 2018). The prevalence of chronic pain has been described as a “sensitive barometer of population health and well-being” that requires proactive population-focused management approaches (Zajacova, Grol-Prokopczyk, and Zimmer, 2021, p. 304; Johnson & Booker, 2021). The disparate impact of pain and unequal treatment in high-risk populations merits not only change but a health equity revolution (Baker, Janevic, & Booker, 2022). A recent consensus paper from the American Academy of Nursing contends that health equity (See Table 1 Definitions of key concepts) in populations cannot be achieved until factors that contribute to disparities, such as systemic racism, are eliminated (Kuehnert et al., 2022).

Table 1.

Definitions of Key Concepts

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Health Disparity | Preventable differences in the burden of disease, injury, violence, or opportunities to achieve optimal health in socially disadvantaged and marginalized populations (e.g., race, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, gender, economic status) (Healthy People, 2030). |

| Health Parity | Resolution of preventable differences in the burden of disease. |

| Health Inequity | Differences in health status or the distribution of health resources between (and within) different population groups as a result of social conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age (World Health Organization, 2018). |

| Health Equity | The state in which everyone has a fair opportunity to attain the highest level of health (Healthy People, 2030). |

| Pain Disparity | Simple or complex differences in the burden of pain that are not always necessarily driven by moral failings (Meghani and Gallagher, 2008). |

| Pain Inequity | State of being unfair in applying services or care to treat and manage pain or understanding and characterizing pain based on moral error (Meghani and Gallagher, 2008). |

| Health Liberation (or Liberation Health) | A method or strategy to assist individuals, families, and communities understand the interacting biopsychosocial, institutional, and system factors that contribute to their health issues and act to change or liberate (or ‘free’) themselves from these oppressive conditions (Belkin Martinez, 2014). |

| Intersectionality | Overlap of various social identities, such as race, gender, sexuality, and class, contributes to the specific type of systemic oppression and discrimination (Carbado et al., 2013). |

| Syndemic theory | Occurrence of sequential diseases and social and environmental factors that may result in the negative effects of disease interactions and outcomes. This approach similarly examines why certain diseases cluster and the influence that social inequality and injustice may have in contributing to such clustering (Singer et al., 2017). |

| Health Equity Action Research | Use of comprehensive interventions to address race, racism, and structural inequalities and advancing evaluation methods to eliminate disparities. This addresses the researcher’s personal biases as part of the research process (Thomas et al., 2011). |

Pain disparities research has overwhelmingly centered race/ethnicity as the primary population factor, but alone, this minimizes lived realities and life-space intersections and illuminates the more immediate need to deconstruct pain-related disparities research across populations, pain conditions, and settings of care. Findings from the Institute of Medicine (2011) clearly acknowledged that pain disparities extend beyond that of the social construction of race. Thus, in developing a population health-level strategy, the Federal Pain Research Strategy prioritized investigating “biological, psychological, social mechanisms that contribute to population group differences in chronic pain” (Interagency Pain Research Coordinating Committee [IPRCC] and the National Institutes of Health, Office of Pain Policy, 2017a, pp. 18–19). The purpose of this theory-guided, non-exhaustive review is not to criticize the current pain literature, but rather to highlight the historical progress of this research, while envisioning and mapping the fourth ‘generation’ that positions the individual as an empowered, activated, and liberated participant in their pain treatment.

Theoretical Framework

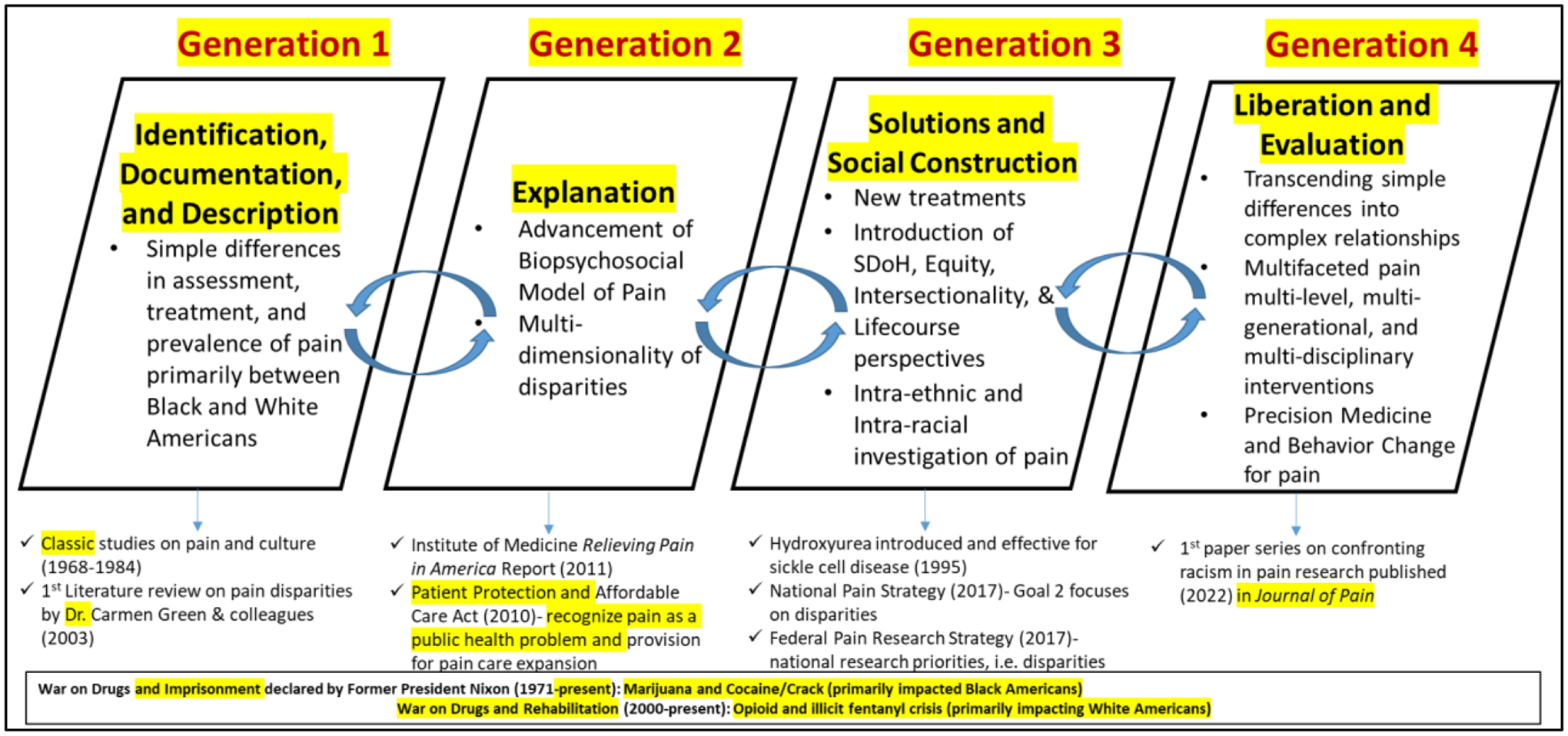

The Hierarchy of Health Disparity Research framework provides an organizational structure to document and categorize health disparities research into four ‘generations’ of disparities work (Thomas et al., 2011). A generation is defined as “a form, type, class, etc., of objects existing at the same time and having many similarities, or developed from a common model or ancestor (often used in combination)” (Merriam-Webster). To date, pain disparities can be characterized by three generations of research, regardless of chronology, that (1) clustered around common goals for understanding and (2) focused largely on Black-White differences:

“Do pain disparities exist?”: Generation one provided a foundational description of the experience of pain and the simple differences in care and outcomes between race, age, and gender groups.

“Why do pain disparities exist?”: The second generation advanced such descriptions and sought to explain the causes of pain disparities by considering the biopsychosocial factors that mediate or moderate the unequal experience, response to, and treatment of pain.

“Are pain interventions accessible and effective?”: The third generation is currently initiating interventions that begin to address the multidimensionality and intersectionality of pain.

“How can we transform disparities into equities through health liberation?”: While not actualized, generation four aims to close the parity gap by disrupting the more traditional descriptive pain research agenda to a solution-focused initiative.

Rather than a strictly chronologic process of describing and organizing research, these four generations represent important bodies of knowledge derived from eras united by common scientific goals, perspectives, theories, or approaches to research (Figure 1). Moving forward with each generation does not make the prior generation obsolete; instead, each generation seeks to close gaps and advance the science of pain and pain care.

Figure 1.

Four Generations of Pain Disparities Research

Methods

To survey the landscape of pain disparities research, we (1) conducted multiple literature searches in PubMed, CINAHL, and PyschInfo databases for articles published between 1960–2021, (2) leveraged the two senior authors’ expertise to identify additional formative and relevant articles [Initials blinded], and (3) reviewed key literature reviews on pain (systematic and narrative). Combinations of keywords included chronic pain, pain, pain disparities, social determinants of health, inequities, culture, intersectionality, rac*(race, racial), ethni*(ethnic, ethnicity), pain assessment, and pain treatment. Four small teams were developed to focus on each generation, and each team organized, reviewed, and synthesized the research for each generation. Articles were sorted and organized based on their focus: descriptive and epidemiological studies (Gen 1), explanation of disparities (Gen 2), solutions and interventions (Gen 3), and transformation and liberation from disparities to equity (Gen 4). Because this was not a systematic review, each team was responsible for identifying relevant articles to help characterize and summarize a particular generation.

The Evolution of Generations of Pain Disparities Research

During the past quarter of a century, pain disparities research has emphasized understanding the pain experience among marginalized populations (Craig et al., 2020; Green et al., 2003; Mathur et al., 2022; Booker, Tripp-Reimer, and Herr, 2020). While this has resulted in purposeful scholarship, it has not entirely captured the complexities and salient differences observed within and between these populations, because prior work failed to address race as a social construct created to oppress and disregard. Hence, disparities observed across demographic identities are intensely embedded in differential treatment, rights, and privileges that are defined by historical, geographic, social, cultural, and economic contexts. Despite the socially constructed nature of race, traditional methodologies have studied variability in pain from the perspective of race similarities or differences (Booker et al., 2021). Researchers must now question if current theoretical models are applicable across race, age, economic, and gendered constructs; while also acknowledging the influence of culture on health (and pain) outcomes. The first generation of disparities research involved identifying populations vulnerable to health disparities and inequities and acknowledging differences in the detection and documentation of health outcomes (Thomas et al., 2011).

First Generation: Identification, Documentation, and Description

The mid-to-late 20th century witnessed a new interest in considering how cultural influences affect the pain experience. Wolff and Langley (1968) commented on a number of pain studies (primarily experimental) regarding their lack of measurement validity, while also addressing the concern of conflating race with culture. Their work inevitably strengthened the dialogue about sociological underpinnings and cultural differences in the pain experience, from differentiating the sensation and experience of pain to that of attitudinal factors. These findings are subsequent to Zborowski’s (1952) and antecedent to Lipton and Marbach’s (1984) and Gaston-Johansson’s (1984) early research allowing scholars to assess methods that disentangle cultural influences on the pain experience. While these pioneering studies underscore the importance of cultural factors, they also highlight the existence of differences within and between (race) groups, in the perception, diagnosis, treatment, and management of pain. Of importance, the first generation debunked the mischaracterization of pain being non-existent or of less magnitude in Black Americans relative to White Americans (Woodrow et al., 1972). In fact, this generation went on to establish that sensitivity to pain in individuals racialized and socialized as ethnic minorities (i.e., Black Americans, Asian Americans, and American Indians) are often more pronounced and severe (Kim et al., 2017; Ahn et al., 2017; Rhudy et al., 2020). Early populations-focused research described racial disparities in veterans (Burgess et al., 2013; 2014), people living with sickle cell disease (Haywood et al., 2014; Smith et al., 2005), and healthy individuals from different ethnic/racial groups (Edwards, Fillingim, & Keefe, 2001; Campbell, Edwards & Fillingim, 2005).

During much of the early 21st century, pain researchers expanded on their scholarly work recognizing chronic disparities across a myriad of groups. A formative review by Green and colleagues reflected on this “unequal burden” of pain (Green et al., 2003). The synthesis of evidence in this seminal review prompted discussions regarding how we define fair and equal treatment among people experiencing pain across varying demographic identities. This highly cited review persuasively declared that pain disparities are beyond that of race as the sole factor, and subsequent reviews over the next 15 years have confirmed the scope of disparities extends to the social determinants and social indicators, especially in Black Americans (Ezenwa et al., 2006; Booker, 2016; Knoebel, Starck, and Miller, 2021). The 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act impelled two national reports by the Institute of Medicine (Relieving Pain in America, 2011) and the IPRCC (Federal Pain Research Strategy, 2017), which similarly identified inequalities and inequities in pain care and treatment and made recommendations to surveil and address these. Indeed, systemic disparities were noted across the spectrum of care from the prevalence of pain to diagnosis and treatment. This report also provided recommendations to combat the nation’s pain through research, education, and practice transformation.

One limitation of the first generation’s early descriptive work was the dearth of epidemiological studies reporting the prevalence of pain in under-represented populations; within the past 18 years, more studies have explored the prevalence of chronic pain across race groups (Portenoy et al., 2004; Meghani and Cho, 2009; Nahin, 2015; 2019; Janevic et al., 2017). Nonetheless, pain is still less likely to be assessed and more likely to be under/misdiagnosed, undertreated, and mismanaged in Black, Asian, and Hispanic patients (Booker, 2016; Burgess et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2019). Many factors contribute to these differences, such as medical and psychological comorbidities, provider bias, discrimination, access to care, assumed criminality, and expectations for care (Hoffman et al., 2016; Meints et al., 2019; Aronowitz et al., 2020; Charleston, 2021). Yet, these differences are evidence of an intricate intersection of behavioral, social, and psychological processes, reflecting the complexity inherent in how we define, measure, and study pain. This first generation of pain scholarship has positioned us to move beyond simplistic descriptive differences to questioning how and why these disparities occur while assessing more tangible outcomes like suffering, delayed recovery, and pain interference.

Second Generation: Explanation

The second generation explained demographic-based differences through the lens of multiple interacting factors that underpinned (pain) disparities. Historically, chronic pain was conceptualized through a dualistic biomedical lens and focused disproportionately on main effects of biological/pathological and medical mechanisms of pain (Bendelow, 2013). The biomedical approach, however, did very little to incorporate the co-influence and interaction effects of psychological, social, behavioral, and cultural factors. The integration of these indicators, as theorized by the biopsychosocial model, advances our knowledge in understanding how psychological (e.g., depression, anxiety, coping), social (e.g., discrimination, social relationships), and cultural (lifestyle behaviors, acculturation) constructs impact who experiences pain and how it is personally experienced (Gatchel et al., 2007; Meints et al., 2019). This conceptual framework underscores the importance of (a) understanding the biopsychosocial mechanisms driving differential pain experiences and (b) the need for interdisciplinary, multi-modal approaches to care. However, it has been challenging for researchers to elucidate how these multiple biopsychosocial factors interact and the strength to which these relationships contribute to pain experiences in different populations. Further, the biopsychosocial model focuses heavily on patient/person-level factors rather than systemic or provider-level factors. Critiques of this model challenged the linearity of the biopsychosocial inputs (i.e., the initial focus and presumed cause of pain are biological and sequentially affect the social experience of pain) and advocated instead for models that emphasize the non-linear interactions that may occur among the triad of variables (Quintner et al., 2008). This integration of social and psychological determinants is yet another framework to consider in defining pain and pain disparities, particularly among diverse racial and ethnic populations (Meints et al., 2019).

Third Generation: Social Construction and Solutions

While the first two generations provided critical perspectives on how we first identify and describe pain within and between groups, the third (and current) generation introduces new theoretical perspectives to address some of the ingrained societal drivers that perpetuate pain disparities. Intersectionality framework challenges the notion of a universal, gendered experience of pain (Samulowitz et al., 2018) and considers the vast permutations of identities and social experiences that impact development, diagnosis, and treatment of pain. Dunn and colleagues (2013) argue that our limited understanding and incorporation of the lifecourse perspective (i.e., current health is shaped by earlier and cumulative exposures to biological, behavioral, and social factors) and the accumulated impact of social determinants on pain is overdue. Taking on this perspective acknowledges that circumstances contributing to pain and disease likely begin in early life, culminating in the additive effects of social determinants such as environment, socioeconomic instability, area deprivation, geographic location, and lifestyle behaviors (Goosby, 2013). This paradigm shift recognizes that social determinants of health (SDoH) play an undeniable role in defining health and pain outcomes for people both individually and as a community (Baker, Janevic, & Booker, 2022). SDoH reflect systems in which people are born, grow up, live, work, and age, but more importantly, that individuals’ lives and health are shaped by the distribution of money, power, resources, and opportunities across all levels of society (Lucyk & McLaren, 2017). This generation identified significant links between pain and lower-income neighborhood (Green & Hart-Johnson, 2012), financial difficulty and residential status (Evans, Bazargan, Cobb, & Assari, 2019), and cumulative disadvantage and perceived discrimination (McClendon et al., 2021). SDoH address indicators beyond that of the individual (patient) and provide meaning to the individual’s circumstances before, during, and after the diagnosis of a pain condition. Indeed, syndemic theory was developed to characterize the concurrent and or sequential adverse interactions between health/health behaviors and social conditions (Singer, Bulled, Ostrach, & Mendenhall, 2017); however, very few studies have applied this concept to investigate chronic pain (Booker & Content, 2020; Slagboom et al., 2021; Strozzi et al., 2020).

Meghani and colleagues offered some of the first extensive agendas with practical strategies to combat pain disparities (Meghani et al., 2012; Campbell et al., 2012). Many of these strategies have been implemented at various levels, but more importantly, their agenda provided a springboard to advance the next generation of pain disparities science. Further, this third generation endeavors to develop national and federal agendas and guidelines for practice and research reform by reducing bias in health care and improving access to health care (IPRCC and the Office of Pain Policy of the National Institutes of Health 2017a; 2017b). While these and other guidelines present multiple ways to combat health disparities, they stop short of addressing other causes and contributors of disparities. Thus, Thomas et al. (2011) stated, “… the third-generation research is necessary, but not sufficient to eliminate disparities and to move toward health equity” (p. 406), and “the current generation of research in health disparities needs to expand beyond social determinants” (Duran & Pérez-Stable, 2019a, p. S8). Therefore, a fourth generation that is grounded in justice is needed to eliminate health disparities (Booker et al., 2021; Thomas et al., 2011).

Toward a Fourth Generation: Liberation and Evaluation

The fourth generation is emergent, and to date, is under-developed in addressing pain. This generation beckons us to “take action” by applying equitable and comprehensive research frameworks to inform implementation and evaluation of long-term solutions (Booker et al., 2021; Letzen et al., 2022; Ali et al., 2021). As the science of pain moves forward, we must ask ourselves some critical questions to move from disparities to equity:

Why do we minimize the diverse realities of disparities and inequities in pain research?

How can we intercept differences in the pain experience that could lead to disparities?

What does a futuristic pain (disparities) research agenda look like?

What perspectives are missing from the science and discipline of pain, and why are they missing?

Although the science of eliminating pain disparities represents a long-term research enterprise, we propose short-term (ST), intermediate-term (IT), and long-term (LT) ways to dismantle and rebuild pain disparities research, which neither diminishes nor discredits the past and current work of pain scholars. We propose five general actions to guide the fourth generation of pain disparities research.

Action 1 (ST): Engage people with lived experience of pain and their caregivers.

The success of the fourth generation cannot be accomplished with providers’ and researchers’ knowledge and experience alone. At the core of moving from disparities to equity is to involve people who live with chronic pain as well as their caregivers who are key partners, “lay scientists,” and personal experts in transforming our understanding and solutions. Such partnerships would help reduce the development and distribution of misinformation about chronic pain, complex pain syndromes, causes of racialized disparities, and related issues such as substance use disorder and psychological stigmatization. This includes integrating people with pain onto our community advisory boards (CABs), research teams, and practice networks. We must place equal emphasis and respect on the lived experience as crucial scientific evidence and expertise that can guide research, clinical practice, education initiatives, and policy-making. Although we must not assume that all racially minoritized individuals have worse health across all outcomes compared to other populations (Duran & Pérez-Stable, 2019b), disparities research must do its role in centering the voices of those who suffer (patients and communities) from the imbalances that are ingrained within health care in order to influence research design and advocacy of pain management (Belton & Smith, 2021; Letzen et al., 2022).

Action 2 (IT): Re-shape our thinking.

One of the key messages from the Relieving Pain in America (Institute of Medicine, 2011) report was the compelling need to transform the perception, treatment, and education around chronic pain. While there have been significant contributions and breakthroughs in the field of pain, the changing social dynamics and population characteristics offers a prime opportunity to restructure how people conceptualize and confront disparities. We contend that different social constructions of the complexity of pain are needed to fully understand the dynamic pain experience in health disparity populations (Craig et al., 2020; Webster et al., 2022). This necessitates investigating the layered effect of multiple bi-directional determinants. Indeed, the critical work on social circumstances and pain, including various levels of suffering and types of discrimination beyond race and gender/sexuality (e.g., weight, intellectual/developmental), has propelled the discovery of meaningful biopsychosocial-behavioral mechanisms and predictors, including new concepts like chronic struggle, social harm, etc. (Webster et al., 2022; Merriwether et al., 2022). In (re)defining how we understand, measure, and intervene on pain among diverse populations, researchers must engage multiple disciplines (e.g., psychology, sociology, nursing, medicine, pharmacy, epidemiology) early in the process of identifying and labeling the problem and proposing solutions and best practices (Akintobi et al., 2019). In defining the context of disparities, what remains overlooked is how we address the upstream and downstream factors that counteract systemic health disparities.

Action 3 (LT): Strike down systems of inequity.

Innovation using multi-level, multi-generational, and multi-disciplinary interventions is central to striking down individual and “structured systems of inequity” (Jones, Holden, & Belton, 2019). A silent undercurrent perpetuating the stagnancy of pain disparities research is structural racism, which represents a “confluence of institutions, culture, history, ideology, and codified practices that generate and perpetuate inequity among racial and ethnic groups” (Hardeman, Medina, & Kozhimannil, 2016, p. 2113). Structural racism limits the freedom of knowledge generated through the processes of “knowing and becoming”. Structural racism and its ancillary attendants, discrimination, prejudice, racial bias, and macroaggressions, are ongoing issues within health care and society and have direct implications on how we treat patients, conduct research, and interpret scientific findings. Another layer to this discourse is the need to refute inaccurate claims that are construed as positive and a safeguard, but in reality, perpetuate inequities and injustices in the provision of pain management and health care (examples include: racial bias in opioid prescribing is protective for Blacks against the addiction crisis, or that providers are no longer discriminating against Blacks regarding opioid prescribing [e.g., Bailey, 2018; Frakt and Monkovic, 2019]). The pervasive adverse impacts of racism and discrimination are strong predictors of pain outcomes (Ghoshal et al., 2020; Merriwether et al., 2021) and should be viewed well beyond a social threat but as physically and psychologically-traumatic events. As this nation works toward anti-racism and racial reconciliation, investigators should carefully measure and interpret the subtle and overt impacts of racism on the development, diagnosis, prognosis, and management of pain (Booker et al., 2021; Morais et al., 2022).

Traditional research-based solutions focus on eliminating disparities from either a top-down, bottom-up, or ‘sideways’ approach (Alvidrez and Stinson, 2019) rather than a comprehensive approach to chronic pain care and science. Further, complicating advances in pain management is that the above approaches use a deficits-based model rather than an asset enhancement model which promotes population health equity. Hence, multi-level interventions and frameworks are necessary to elucidate the causes, contributors, and consequences of disparities in pain care and research. According to Alvidrez and colleagues (2019), applying an innovative and progressive framework could account for the complexities of the different identities and cultures of the people being treated. Frameworks, such as the health equity action research trajectory ([HEART]; Thomas et al., 2011) and the eco-psychopolitical validity (EPV) model (Tankwanchi, 2018), offer potential ways to study and combat pain disparities. These frameworks motion for proactive research that accounts for social conditions, environmental factors, and policy relevant to pain disparities, health equity, and social justice. They further recommend shifting attention toward understanding how macrosocial determinants (e.g., corporate practices, political ideologies, economic philosophies, industrialization, taxation) shape how we conceptualize pain outcomes, particularly among diverse populations. Promisingly, recent Requests for Applications from the National Institutes of Health’s Helping to End Addiction Long-term (HEAL) focus on advancing health equity in pain through culturally and linguistically appropriate interventions that address multiple socioecological levels of influence in health disparity populations (e.g., RFA-NS-22–037; RFA-NS-22–002).

Action 4 (ST): Foster health empowerment.

A key question to answer is whether we are “reducing health disparities or improving minority health?” (Partin and Burgess, 2012, p. 887). Duran and Pérez-Stable (2019) unveiled a “science visioning” for advancing health disparities research that centers on clearly defining and distinguishing between minority health and health disparities and outlined specific health outcomes that will lead to novel discoveries. Granted, description of racial differences (née disparities) has helped to illuminate the disparate conditions under which many live and manage pain but has concurrently, unintentionally siloed and marginalized disadvantaged groups from progressively moving towards health empowerment and liberation (Baker, Janevic, and Booker, 2022).

Transformational research paradigms are needed to foster the full liberation of transgenerational health for individuals racialized and socialized as ethnic minorities (Akintobi et al., 2019). Transformational research considers solutions and the means whereby people and communities can liberate themselves from current oppressive ecological systems in order to advance their personal and collective health well-being (Tankwanchi, 2018). This form of health empowerment can be accomplished through integrative, collaborative, and community-engaged models of pain care that center justice at the forefront and consider injustice as a measurable outcome. Recently, Mathur and colleagues (2022) challenged scholars to investigate pain disparities through a set of interacting cultural, structural, and interpersonal injustice lenses.

Thus, a fourth generation of pain disparities research will need to develop solutions that foster health empowerment and liberation in the most just way that refrains from “minoritizing” populations and their differences and instead ‘indigenize’ treatments and care for chronic health conditions, including pain, across the lifecourse of different populations (Baker et al., 2017). The result of culturally-agnostic interventions is a continuation of health disparities (Jones N.L. et al., 2019). Yet, merely superimposing interventions that were not developed with, for, or by the target population will only result in a revolving door of trial and error, in a time where the resolution of chronic pain is more urgent than ever. Health liberation requires “redirecting society’s priorities to the benefits of evidence-based and population-level prevention and management programs that account for risk factors endemic to disparate populations” (Baker et al., 2017, p. no page). Such interventions and programs will be more successful when (1) informed by people with lived experience of pain and community stakeholders, (2) culturally tailored to an individual’s, community’s, or ethnic group’s identity, and (3) sustainable over the lifecourse for the underserved, poorly served, and never-served populations.

Action 5 (LT): Apply Precision Behavior Change.

The science of behavior change investigates the mechanisms that drive human behaviors or improvement of behaviors (Davidson & Scholz, 2020), but few have considered how this science applies to reducing pain disparities. Coaching, coping skills training, and self-efficacy enhancement are a few pain-related behavioral intervention targets that have been trialed in Black Americans (Allen et al., 2019; Hazard Vallerand et al., 2018; Burgess et al., 2022). Future investigations require an exploration of imbalances and inequities created by structural racism and societal stigmas that challenge patients’ resilience to implement and sustain positive behavior change and health autonomy in preventing and managing pain. Important to consider is how adverse exposures become embodied and embedded within the biological and behavioral fabric of health disparity populations’ lives, such as Black Americans (Booker et al., 2021). This is essential to identifying and addressing ways to prevent pain and keep racialized individuals with pain “healthy”. Two challenges underlying precision behavior change are the lack of data diversity in pain research and the absence of validated instruments that measure culturally-relevant behaviors and indicators of pain. Indeed, scholars have recently called for a more standardized and unified approach to measuring pragmatic health disparities outcomes (Duran and Pérez-Stable, 2019b). We also need more precise and consistent measurement of SDoH, ancestry (genetic heterogeneity and propensity for high-risk pain), and qualitative studies to identify relevant pain-related common data elements. We are careful to point out that genetic investigations should not reify biased biology-based pain beliefs (Booker et al., 2021), but within the context of social genomics, can provide important information about genealogical health risks that place individuals at risk for pain conditions or increased pain sensitivity (Aroke et al., 2019), in addition to rare diseases that do not allow individuals to feel pain.

Implications for Nursing

Understanding and treating pain and related disparities is an interdisciplinary challenge. However, the late Dr. Jo Eland boldly pronounced, “Nurses own pain” (St. Marie and Arnstein, 2016, p. 37). Nurses and nurse scientists can approach pain management and pain research not only with a holistic view but now more than ever, through justice and equity lenses. Nurses have made an indelible mark in generating new knowledge, translating evidence into practice, and developing models of pain care. Van Cleave and colleagues (2021) highlight numerous influential nurses that have advanced the science and practice of pain management, particularly in the areas of opioid use, health policy, and clinical practice models.

To move from pain disparities research to pain equity research, we must uphold the fundamental position that “Nurses have an ethical responsibility to relieve pain and the suffering it causes” (American Nurses Association, 2018). In the same regard, Berkowitz and McCubbin (2016) stated that nurses have a moral responsibility to address health disparities, and they proposed a framework to eliminate health disparities. First, trust must be restored in historically underrepresented communities (Bowen, Epps, Lowe, & Guilamo-Ramos, 2022), respecting cultural behaviors, and addressing bias, SDoH, and systems-level factors that negatively impact pain management for patients and their caregivers (Booker et al., 2022). But more importantly, we must take the stories of the people living with pain to our legislators and payers, educating them on the reality of pain disparities, inequities, and injustices that many experience. Exploring the progress made in the field of pain over the past three decades is necessary to cross-map achievement in national pain goals and develop a roadmap for the future.

Conclusion

We have summarized a growing scientific base regarding pain disparities and have presented a bold outlook for a paradigm shift for investigating and mitigating pain disparities (i.e., fourth generation). A new framework must be adopted— one that not only addresses familiar factors but also introduces and expands on what is missing from the conversation. The time is now to move away from a linear model that looks no further than the present to explain the inequities that exist within our health care system. This will spur a new era in health care that views people with lived experiences of pain through a prism and not a single lens.

Acknowledgements:

We would to thank Dr. Roger Fillingim for critical review of a version of this paper.

Funding:

Dr. Booker is supported by the National Institutes of Health/NIAMS (K23AR076463).

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest: None of the authors report any actual or perceived conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Staja Q. Booker, University of Florida, College of Nursing, 1225 Center Drive, Gainesville, FL 32610.

Tamara A. Baker, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Department of Psychiatry, 306 MacNider Bldg., 333 S. Columbia Street, Chapel Hill, NC 27599

Darlingtina Esiaka, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, Rutgers University, Newark, NJ 07102.

Jacquelyn A. Minahan, Health Psychology Service, Rocky Mountain Regional VA Medical Center, 1700 N Wheeling Street, Aurora, CO 80045

Ilana J. Engel, The University of Kansas, Department of Psychology, 426 Fraser Hall, Lawrence, KS 66045

Kasturi Banerjee, The University of Kansas, Department of Psychology, 426 Fraser Hall, Lawrence, KS 66045.

Michaela Poitevien, Barry University, Department of Biomedical Sciences, Miami Shores, FL 33161.

REFERENCES

- Ahn H, Weaver M, Lyon DE, Kim J, Choi E, Staud R, & Fillingim RB (2017). Differences in clinical pain and experimental pain sensitivity between Asian Americans and Whites with knee osteoarthritis. Clinical Journal of Pain, 33(2), 174–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akintobi TH, Hopkins J, Holden KB, Hefner D, & Taylor HA Jr. (2019). Tx ™: An approach and philosophy to advance translation to transformation. Ethnicity and Disease, 29(Suppl 2), 349–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali J, Davis AF, Burgess DJ, Rhon DI, Vining R, Young-McCaughan S, Green S, & Kerns RD (2021). Justice and equity in pragmatic clinical trials: Considerations for pain research within integrated health systems. Learning Health Systems, 6(2), e10291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen KD, Somers TJ, Campbell LC, Arbeeva L, Coffman CJ, Cené CW, Oddone EZ, & Keefe FJ (2019). Pain coping skills training for African Americans with osteoarthritis: Results of a randomized controlled trial. PAIN, 160(6), 1297–1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvidrez J, & Stinson N Jr. (2019). Sideways progress in intervention research is not sufficient to eliminate health disparities. American Journal of Public Health, 109(S1), S102–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aroke EN, Joseph PV, Roy A, Overstreet DS, Tollefsbol TO, Vance DE, & Goodin BR (2019). Could epigenetics help explain racial disparities in chronic pain? Journal of Pain Research, 12, 701–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronowitz SV, Mcdonald CC, Stevens RC, & Richmond TS (2020). Mixed studies review of factors influencing receipt of pain treatment by injured Black patients. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(1), 34–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey L (2018, May 1). Blacks, whites equally as likely to be prescribed opioids for pain. Michigan News. Retrieved from https://news.umich.edu/blacks-whites-equally-as-likely-to-be-prescribed-opioids-for-pain/ [Google Scholar]

- Baker TA, Janevic M, & Booker SQ (2022). Chronic pain and the movement toward progressive healthcare. In Berger Z (Ed.), Health for everyone: A guide to politically and socially progressive healthcare (pp. 19–26). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Baker TA, Clay OJ, Johnson-Lawrence V, Minahan JA, Mingo CA, Thorpe RJ, Ovalle F, & Crowe M (2017). Association of multiple chronic conditions and pain among older Black and White adults with diabetes mellitus. BMC Geriatrics, 17(1), 255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belkin Martinez D (2014). Liberation health: An introduction. In Belkin Martinez D and Fleck-Henderson A (Eds.), Social justice in clinical practice: A liberation health framework for social work. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Belton J, & Smith B (2020). The IASP Global Alliance of Partners for Pain Advocacy (GAPPA): Incorporating the lived experience of pain into the study of pain. Accessed https://www.iasp-pain.org/publications/relief-news/article/the-iasp-global-alliance-of-partners-for-pain-advocacy-gappa-incorporating-the-lived-experience-of-pain-into-the-study-of-pain/

- Bendelow G (2013). Chronic pain patients and the biomedical model of pain. Virtual Mentor, 15(5), 455–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz B, & McCubbin M (2005). Advancement of health disparities research: A conceptual approach. Nursing Outlook, 53(3), 153–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booker SQ (2016). African Americans’ perceptions of pain and pain management: A systematic review. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 27(1), 73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booker SQ, Baker TA, Epps F, Herr KA, Young HM, & Fishman S (2022). Interrupting biases in the experience and management of pain. American Journal of Nursing, 122(9), 48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booker SQ, Bartley EJ, Powell-Roach K, Palit S, Morais C, Thompson OJ, Cruz-Almeida Y, & Fillingim RB (2021). The imperative for racial equality in pain science: A way forward. Journal of Pain, 22(12), 1578–1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booker SQ, & Content VG (2020). Chronic pain, cardiovascular health and related medication use in ageing African Americans with osteoarthritis. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(13–14), 2675–2690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booker SQ, Tripp-Reimer T, & Herr KA (2020). “Bearing the pain”: The experience of aging African Americans with osteoarthritis pain. Global Qualitative Nursing Research, 7, 2333393620925793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen FR, Epps F, Lowe J, & Guilamo-Ramos V (2022). Restoring trust in research among historically underrepresented communities: A call to action for antiracism research in nursing. Nursing Outlook, 70(5), 700–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess DJ, Hagel Campbell E, Hammett P, Allen KD, Fu SS, Heapy A, Kerns RD, Krein SL, Meis LA, Bangerter A, Cross LJS, Do T, Saenger M, & Taylor BC (2022). Taking ACTION to reduce pain: A randomized clinical trial of a walking-focused, proactive coaching intervention for Black patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Journal of General Internal Medicine, Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess DJ, Gravely AA, Nelson DB, van Ryn M, Bair MJ, Kerns RD, Higgins DM, & Partin MR (2013). A national study of racial differences in pain screening rates in the VA health care system. Clinical Journal of Pain, 29(2), 118–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess DJ, Nelson DB, Gravely AA, Bair MJ, Kerns RD, Higgins DM, van Ryn M, Farmer M, & Partin MR (2014). Racial differences in prescription of opioid analgesics for chronic noncancer pain in a national sample of veterans. Journal of Pain, 15(4), 447–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell CM, Edwards RR, & Fillingim RB (2005). Ethnic differences in responses to multiple experimental pain stimuli. PAIN, 113(1–2), 20–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell LC, Robinson K, Meghani SH, Vallerand A, Schatman M, & Sonty N (2012). Challenges and opportunities in pain management disparities research: Implications for clinical practice, advocacy, and policy. Journal of Pain, 13(7), 611–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbado DV, Crenshaw KW, Mays VM, & Tomlinson B (2013). Intersectionality: Mapping the movements of a theory. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research in Race, 10(2), 303–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charleston L 4th. (2021). Headache disparities in African-Americans in the United States: A narrative review. Journal of the National Medical Association, 113(2), 223–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig KD, Holmes C, Hudspith M, Moor G, Moosa-Mitha M, Varcoe C, & Wallace B (2020). Pain in persons who are marginalized by social conditions. PAIN, 161(2), 261–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlhamer J, Lucas J, Zelaya C, Nahin R, Mackey S, DeBar L, Kerns R, Von Korff M, Porter L, & Helmick C (2018). Prevalence of chronic pain and high-impact chronic pain among adults — United States, 2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67(36), 1001–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson KW, & Scholz U (2020). Understanding and predicting health behaviour change: A contemporary view through the lenses of meta-reviews. Health Psychology Review, 14(1), 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran DG, & Pérez-Stable EJ (2019a). Novel approaches to advance minority health and health disparities research. American Journal of Public Health, 109(S1), S8–S10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran DG, & Pérez-Stable EJ (2019b). Science visioning to advance the next generation of health disparities research. American Journal of Public Health, 109(S1), S11–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn KM, Hestbaek L, & Cassidy JD (2013). Low back pain across the life course. Best Practice and Research: Clinical Rheumatology, 27(5), 591–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards CL, Fillingim RB, & Keefe F (2001). Race, ethnicity and pain. PAIN, 94(2), 133–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans MC, Bazargan M, Cobb S, & Assari S (2019). Pain intensity among community-dwelling African American older adults in an economically disadvantaged area of Los Angeles: social, behavioral, and health determinants. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(20), 3894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezenwa MO, Ameringer S, Ward SE, & Serlin RC (2006). Racial and ethnic disparities in pain management in the United States. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 38(3), 225–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frakt A, & Monkovic T (2019, Nov. 25). A ‘rare case where racial biases’ protected African-Americans. New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/25/upshot/opioid-epidemic-blacks.html [Google Scholar]

- Gatchel RJ, Peng YB, Peters ML, Fuchs PN, & Turk DC (2007). The biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain: Scientific advances and future directions. Psychological Bulletin, 133(4), 581–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaston-Johansson F (1984). Pain assessment: Differences in quality and intensity of the words pain, ache and hurt. PAIN, 20(1), 69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghoshal M, Shapiro H, Todd K, & Schatman ME (2020). Chronic noncancer pain management and systemic racism: Time to move toward equal care standards. Journal of Pain Research, 13, 2825–2836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goosby BJ (2013). Early life course pathways of adult depression and chronic pain. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 54(1), 75–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green CR, Anderson KO, Baker TA, Campbell LC, Decker S, Fillingim RB, Kalauokalani DA, Lasch KE, Myers C, Tait RC, Todd KH, & Vallerand AH (2003). The unequal burden of pain: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in pain. Pain Medicine, 4(3), 277–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green CR, & Hart-Johnson T (2012). The association between race and neighborhood socioeconomic status in younger Black and White adults with chronic pain. Journal of Pain, 13(2), 176–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardeman RR, Medina EM, & Kozhimannil KB (2016). Structural racism and supporting Black lives— The role of health professionals. New England Journal of Medicine, 375(22), 2113–2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haywood C Jr., Diener-West M, Strouse J, Carroll CP, Bediako S, Lanzkron S, Haythornthwaite J, Onojobi G, Beach MC; IMPORT Investigators. (2014). Perceived discrimination in health care is associated with a greater burden of pain in sickle cell disease. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 48(5), 934–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazard Vallerand A, Hasenau SM, Robinson-Lane SG, & Templin TN (2018). Improving functional status in African Americans with cancer pain: A randomized clinical trial. Oncology Nursing Forum, 45(2), 260–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healthy People 2030. (Updated August 2, 2021). Healthy People 2030 questions and answers. https://health.gov/our-work/healthy-people/healthy-people-2030/questions-answers

- Health People 2030. Health Equity in Healthy People 2030. https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/health-equity-healthy-people-2030

- Hoffman KM, Trawalter S, Axt JR, & Oliver MN (2016). Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the United States of America, 113(16), 4296–4301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (IOM). 2011. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Interagency Pain Research Coordinating Committee and the Office of Pain Policy of the National Institutes of Health. 2017a. “Federal pain research strategy.” Retrieved from https://www.iprcc.nih.gov/sites/default/files/iprcc/FPRS_Research_Recommendations_Final_508C.pdf

- Interagency Pain Research Coordinating Committee and the Office of Pain Policy of the National Institutes of Health. 2017b. “National pain strategy report: A comprehensive high-level strategy for pain.” Retrieved from https://www.iprcc.nih.gov/sites/default/files/HHSNational_Pain_Strategy_508C.pdf

- Janevic MR, McLaughlin SJ, Heapy AA, Thacker C, & Piette JD (2017). Racial and socioeconomic disparities in disabling chronic pain: Findings from the Health and Retirement Study. Journal of Pain, 18(12), 1459–1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A, & Booker SQ (2021). Population-Focused approaches for proactive chronic pain management in older adults. Pain Management Nursing, 22(6), 694–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CP, Holden KB, & Belton A (2019). Strategies for achieving health equity: Concern about the whole plus concern about the hole. Ethnicity and Disease, 29(Suppl 2), 345–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones NL, Breen N, Das R, Farhat T, & Palmer R (2019). Cross-cutting themes to advance the science of minority health and health disparities. American Journal of Public Health, 109(S1), S21–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Yang GS, Greenspan JD, Downton KD, Griffith KA, Renn CL, Johantgen M, & Dorsey SG (2017). Racial and ethnic differences in experimental pain sensitivity: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PAIN, 158(2), 194–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoebel RW, Starck JV, & Miller P (2021). Treatment disparities among the Black population and their influence on the equitable management of chronic pain. Health Equity, 5(1), 596–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehnert P, Fawcett J, DePriest K, Chinn P, Cousin L, Ervin N, Flanagan J, Fry-Bowers E, Killion C, Maliski S, Maughan ED, Meade C, Murray T, Schenk B, & Waite R (2022). Defining the social determinants of health for nursing action to achieve health equity: A consensus paper from the American Academy of Nursing. Nursing Outlook, 70(1), 10–27. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2021.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee P, Le Saux M, Siegel R, Goyal M, Chen C, Ma Y, & Meltzer AC (2019). Racial and ethnic disparities in the management of acute pain in us emergency departments: Meta-Analysis and systematic review. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 37(9), 1770–1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letzen JE, Mathur VA, Janevic MR, Burton MD, Hood AM, Morais CA, Booker SQ, Campbell CM, Aroke EN, Goodin BR, Campbell LC, & Merriwether EN (2022). Confronting racism in all forms of pain research: Reframing study designs. Journal of Pain, 23(6), 893–912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton JA, & Marbach JJ (1984). Ethnicity and the pain experience. Social Science and Medicine, 19(12), 1279–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucyk K, & McLaren L (2017). Taking stock of the social determinants of health: A scoping review. PLoS ONE, 12(5), e0177306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur VA, Trost Z, Ezenwa MO, Sturgeon JA, & Hood AM (2022). Mechanisms of injustice: What we (do not) know about racialized disparities in pain. PAIN, 163(6), 999–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClendon J, Essien UR, Youk A, Ibrahim SA, Vina E, Kwoh CK, & Hausmann LRM (2021). Cumulative disadvantage and disparities in depression and pain among veterans with osteoarthritis: The role of perceived discrimination. Arthritis Care and Research (Hoboken), 73(1), 11–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meints SM, Cortes A, Morais CA, Edwards RR (2019). Racial and ethnic differences in the experience and treatment of noncancer pain. Pain Management, 9(3), 317–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meghani SH, & Gallagher RM (2008). Disparity vs inequity: Toward reconceptualization of pain treatment disparities. Pain Medicine, 9(5), 613–623. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2007.00344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meghani SH, & Cho E (2009). Self-reported pain and utilization of pain treatment between minorities and nonminorities in the United States. Public Health Nursing, 26(4), 307–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meghani SH, Polomano RC, Tait RC, Vallerand AH, Anderson KO, & Gallagher RM (2012). Advancing a national agenda to eliminate disparities in pain care: Directions for health policy, education, practice, and research. Pain Medicine, 13(1), 5–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merriwether EN, Wittleder S, Cho G, Bogan E, Thomas R, Bostwick N, Wang B, Ravenell J, & Jay M (2021). Racial and weight discrimination associations with pain intensity and pain interference in an ethnically diverse sample of adults with obesity: a baseline analysis of the clustered randomized-controlled clinical trial the goals for eating and moving (GEM) study. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 2201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morais CA, Aroke EN, Letzen JE, Campbell CM, Hood AM, Janevic MR, Mathur VA, Merriwether EN, Goodin BR, Booker SQ, & Campbell LC (2022). Confronting racism in pain research: A call to action. Journal of Pain, 23(6), 878–892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahin RL (2015). Estimates of pain prevalence and severity in adults: United States, 2012. Journal of Pain, 16(8), 769–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahin RL, Sayer B, Stussman BJ, Feinberg TM (2019). Eighteen-year trends in the prevalence of, and health care use for, noncancer pain in the United States: Data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Journal of Pain, 20(7), 796–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partin MR, & Burgess DJ (2012). Reducing health disparities or improving minority health? The end determines the means. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 27(8), 887–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portenoy RK, Ugarte C, Fuller I, & Haas G (2004). Population-based survey of pain in the United States: Differences Among White, African American, and Hispanic Subjects. Journal of Pain, 5(6), 317–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samulowitz A, Gremyr I, Eriksson E, & Hensing G (2018). “Brave men” and “emotional women”: A theory-guided literature review on gender bias in health care and gendered norms towards patients with chronic pain. Pain Research and Management, 2018, 6358624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slagboom MN, Reis R, Tsai AC, Büchner FL, van Dijk DJA, & Crone MR (2021). Psychological distress, cardiometabolic diseases and musculoskeletal pain: A cross-sectional, population-based study of syndemic ill health in a Dutch fishing village. Journal of Global Health, 11, 04029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith WR, Bovbjerg VE, Penberthy LT, McClish DK, Levenson JL, Roberts JD, Gil K, Roseff SD, & Aisiku IP (2005). Understanding pain and improving management of sickle cell disease: the PiSCES study. Journal of the National Medical Association, 97(2), 183–193. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintner JL, Cohen ML, Buchanan D, Katz JD, & Williamson OD (2008). Pain medicine and its models: Helping or hindering? Pain Medicine, 9(7), 824–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhudy JL, Lannon EW, Kuhn BL, Palit S, Payne MF, Sturycz CA, Hellman N, Güereca YM, Toledo TA, Huber F, Demuth MJ, Hahn BJ, Chaney JM, & Shadlow JO (2020). Assessing peripheral fibers, pain sensitivity, central sensitization, and descending inhibition in Native Americans: Main findings from the Oklahoma Study of Native American Pain Risk. PAIN, 161(2), 388–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer M, Bulled N, Ostrach B, & Mendenhall E (2017). Syndemics and the biosocial conception of health. Lancet, 4(10072), 941–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strozzi AG, Peláez-Ballestas I, Granados Y, Burgos-Vargas R, Quintana R, Londoño J, Guevara S, Vega-Hinojosa O, Alvarez-Nemegyei J, Juarez V, Pacheco-Tena C, Cedeño L, Garza-Elizondo M, Santos AM, Goycochea-Robles MV, Feicán A, García H, Julian-Santiago F, Crespo ME, Rodriguez-Amado J, Rueda JC, Silvestre A, Esquivel-Valerio J, Rosillo C, Gonzalez-Chavez S, Alvarez-Hernández E, Loyola-Sanchez A, Navarro-Zarza E, Maradiaga M, Casasola-Vargas J, Sanatana N, Garcia-Olivera I, Goñi M, Sanin LH, Gamboa R, Cardiel MH, & Pons-Estel BA; GEEMA (Grupo de Estudio Epidemiológico de Enfermedades Músculo Articulares) and Group COPCORD-LATAM (Explicar la abreviatura); GLADERPO (Grupo Latino Americano De Estudio de Pueblos Originarios). (2020). Syndemic and syndemogenesis of low back pain in Latin-American population: A network and cluster analysis. Clinical Rheumatology, 39(9), 2715–2726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tankwanchi ABS (2018). Oppression, liberation, wellbeing, and ecology: Organizing metaphors for understanding health workforce migration and other social determinants of health. Globalization and Health, 14(1), 81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas SB, Quinn SC, Butler J, Fryer CS, & Garza MA (2011). Toward a fourth generation of disparities research to achieve health equity. Annual Review of Public Health, 32, 399–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster F, Connoy L, Sud A, Rice K, Katz J, Pinto AD, Upshur R, & Dale C (2022). Chronic struggle: An institutional ethnography of chronic pain and marginalization. Journal of Pain. Online ahead of print. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2022.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff BB, & Langley S (1968). Cultural factors and the response to pain: A review. American Anthropologist, 70(3), 494–501. [Google Scholar]

- Woodrow KM, Friedman GD, Siegelaub AB, & Collen MF (1972). Pain tolerance: Differences according to age, sex and race. Psychosomatic Medicine, 34(6), 548–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2018). Health inequities and their causes. https://www.who.int/features/factfiles/health_inequities/en/

- Zajacova A, Grol-Prokopczyk H, & Zimmer Z (2021). Sociology of pain. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 62(3), 302–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zborowski M (1952). Cultural components in responses to pain. Journal of Social Issues, 8(4), 16–30. [Google Scholar]