Abstract

Background:

The landscape of modern aesthetic medicine has witnessed a paradigm shift from traditional doctor-led care to a consumer-driven model, presenting a plethora of ethical challenges. This review discusses the ethical dimensions of medical aesthetics, exploring the implications of consumer demand, societal influences, and technological advancements on patient care and well-being.

Methods:

Drawing upon a comprehensive analysis of existing literature, this review synthesizes evidence regarding the rise of aesthetic medicine, ethical challenges encountered in practice, and the implications of social media and marketing in shaping patient perceptions and decision-making.

Results:

Aesthetic medicine confronts unique ethical challenges stemming from its elective nature and the pervasive influence of societal beauty standards. Concerns include the commodification of beauty, conflicts of interest, limited evidence-base of treatments, and the rise of nonphysician providers. Moreover, the evolving role of social media influencers and medical marketing raises ethical dilemmas regarding transparency, patient autonomy, and professional integrity.

Conclusions:

The ethical landscape of aesthetic medicine necessitates a proactive approach to address emerging challenges and safeguard patient well-being. Guided by principles of autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice, recommendations are proposed to enhance informed consent practices, mitigate appearance anxiety, facilitate shared decision-making, and promote responsible use of social media. Professional societies are urged to establish clear ethical guidelines and standards to uphold professionalism and patient trust in the field of aesthetic medicine.

Takeaways

Question: What impact does the medicalization of beauty, combined with scientific advancements, increasing accessibility of aesthetic services, and the pervasive influence of social media collectively have on ethical discourse?

Findings: As the field of aesthetic medicine continues to evolve, it is essential to reflect on the foundational principles of autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice to better navigate these challenges.

Meaning: We have identified a concerning lack of well-defined ethical guidelines within the realm of aesthetic medicine. Professional aesthetic societies must establish formal guidelines and ethical training standards for non-surgical aesthetic providers to ensure the highest level of professionalism and patient well-being.

INTRODUCTION

In times past, the doctor–patient relationship followed a straightforward path: a patient sought care for a medical concern, and a doctor provided a diagnosis and treatment plan. However, in the realm of modern aesthetic medicine, patients often present with specific treatment requests, marking a shift toward a more “consumer-driven” medical paradigm.1 This transformation introduces a myriad of ethical challenges. The medicalization of beauty, combined with scientific advancements, increasing accessibility of aesthetic services, and the pervasive influence of social media collectively demand a concurrent advancement in ethical discourse. This review examines these ethical dimensions of medical aesthetics, aiming to highlight areas of concern and propose strategies to foster ethical practice.

THE RISE OF AESTHETIC MEDICINE

Medical aesthetics covers nonsurgical cosmetic treatments for the face and body, like injectables (eg, botulinum toxin and dermal fillers), energy-based therapies, chemical peels, and body sculpting. These are performed by specialized physicians, general practitioners, and nonphysician technicians, distinguishing them from invasive plastic surgical procedures, which need specialized plastic surgeons.

The evolving landscape of consumer perspectives on wellness, beauty, and healthy aging has fostered an increased awareness and acceptance of aesthetic treatments, positioning them as integral components of routine self-care. Based on a comprehensive McKinsey survey in 2021, the annual revenue of aesthetic medicine is projected to grow by 12% over the next 5 years.2 In line with this surge in demand, the latest American Society of Plastic Surgeons annual survey reported a more than 70% increase in botulinum toxin, hyaluronic acid filler, and noninvasive fat reduction treatments compared with prepandemic rates in 2019.3

This growing demand reflects a heightened societal focus on physical appearance in the midst of a rapidly advancing digital era. Despite the excitement generated by new cosmetic products and trends, the swift pace of growth in the industry raises concerns about safety, professionalism, and equitable access to care. It is important to ensure that the quest for beauty remains anchored in principles of safety, authenticity, and overall well-being. Beyond mere enhancements in appearance, the underlying essence of these procedures lies in fostering confidence and self-worth.

THE ETHICAL CHALLENGES OF MEDICAL AESTHETICS

Medical aesthetics faces distinct ethical challenges due to its elective nature (Fig. 1), unlike fields focused on saving lives and treating illnesses.4–6 Patients often come to consultations with an interest in particular treatments and outcomes, at times influenced by external factors such as social media and societal pressures,7 shifting the dynamic from a conventional “doctor-led” model to a “consumer-led” approach.8 In another departure from other medical specialties, the decision to pursue aesthetic treatments is complex and often influenced by external factors. Societal and interpersonal pressures play a significant role in motivating individuals to seek cosmetic procedures9 to fit in with evolving standards of “normalcy.”10 Individuals are especially vulnerable to psychosocial pressures during significant life events, such as divorce, which can significantly impact their decision-making.11

Fig. 1.

This figure presents a concise summary of the intricate and distinctive ethical dilemmas confronted by practitioners of aesthetic medicine. It encapsulates the multifaceted nature of these challenges, offering insight into the complex ethical landscape specific to the field.

Despite the surge in global demand for aesthetic procedures, there is a conspicuous absence of well-defined ethical guidelines within the realm of aesthetic medicine. The Nuffield Council on Bioethics underscored the urgent necessity for comprehensive ethical reflection on aesthetic procedures, to address both their potential for enhancing self-confidence as well as societal concerns.9 The prevalence of these procedures has the potential to reinforce certain appearance ideals and perpetuate societal norms related to gender, age, and race, thus necessitating a nuanced ethical approach.10 Establishing and enforcing formal ethical guidelines by professional societies should prioritize patient safety and ethical practice in aesthetic medicine. In the following sections, ethical issues commonly faced in aesthetic medical practice will be discussed.

THE CHALLENGE OF MEASURING “BEAUTY”

One of the primary challenges of aesthetic medicine is the inherent difficulty of measuring outcomes. Unlike other specialties where outcomes are clear, defining beauty proves to be an elusive task.10 Objective measures are scarce, with physicians often relying on aesthetic scales or a broad assessment of aesthetic improvement,12 both inherently subjective in nature. This highlights the need for validated patient-reported outcomes, such as the FACE-Q questionnaire,13 which evaluates patient satisfaction and improvements in quality of life after surgical and nonsurgical facial rejuvenation.13,14 Despite these tools being available, their routine use in clinical settings is still rare.

APPEARANCE AND AGING ANXIETY

The prevailing conviction that beauty is tied to success and happiness15 is relentlessly reinforced by the media, which promotes a narrow definition of beauty, idealizing youthfulness, symmetry, and thinness.16 Consequently, individuals find themselves pressured to align with these beauty standards irrespective of their personal values.10 Notably, women bear a disproportionate burden of beauty standards, and those of non-White ethnicity often struggle with additional pressures to conform to Eurocentric ideals.17 The emergence of social media has bred heightened appearance anxiety, driving patients to pursue an increasing number of procedures to meet these elusive standards.18 Furthermore, the inundation of “filtered” imagery has distorted our understanding of what is “normal.”19 With the use of filters, we now compare ourselves not with magazine covers but with airbrushed versions of ourselves. This phenomenon has been scientifically demonstrated with studies observing that repeated exposure to enhanced images influences participants’ perceptions of the ideal body shape20 and desire for lip filler.21 This relentless pressure to conform to unattainable beauty standards can adversely affect mental well-being, as demonstrated by increasing evidence of the associations of social media use with markers of depression, particularly among teenagers and young adults.10,22,23

Although beauty standards evolve, youthfulness remains a constant feature of attractiveness.7 The apprehension surrounding aging transcends an individual’s self-esteem; it may result in concerns about the potential consequences of visible aging, such as its impact on employment opportunities or relationships.19 Ageism (prejudicial treatment based on age) manifests in various forms and can significantly compromise the mental well-being of adults, leading to depression and other psychological health issues.24 The societal obsession with preserving a youthful appearance not only places undue pressure on individuals but also inadvertently perpetuates harmful stereotypes surrounding aging.

In the quest for “anti-aging” treatments, aesthetic providers must acknowledge the potential to perpetuate age-related stigma and negative perceptions of older age.

LIMITED EVIDENCE-BASE OF AESTHETIC TREATMENTS

The use of unvalidated techniques and procedures is a common issue in aesthetic fields. In stark contrast to the rigorous scrutiny endured by other medical therapies, emerging aesthetic surgical techniques frequently undergo exploration without being subjected to thoroughly peer-reviewed clinical studies. For instance, polynucleotides from fish sources like salmon and trout are widely used in clinics across Southeast Asia, despite limited clinical studies.25 Another example is Gouri, an injectable liquid polycaprolactone marketed in the region, which lacks published clinical studies yet is commonly used as a dermal filler.26 This deficiency in standardized scrutiny for innovation within medical aesthetics raises ethical questions concerning potential benefits, informed consent, patient safety, and public deception in aesthetics.

PROCEDURES BY NONPHYSICIANS

In several countries, nonphysicians and providers without medical training are authorized to perform nonsurgical aesthetic procedures.27,28 In the United States, medical spas have proliferated to the extent that they outnumber physician-based cosmetic practices in 73% of major US cities.29 These facilities often lack oversight and rely on providers with varying levels of training, which may contribute to adverse events such as burns, pigmentary alterations, and scarring.29 In the United Kingdom, up to 23% of aesthetic procedures are performed by practitioners who are not medically trained,27 such as aestheticians, allied health care professionals, dental nurse students, and pharmacists. The significant variation in provider training has serious consequences for patient care. In a recent study, differences in training as categorized by certification from either the American Board of Plastic Surgery (which is recognized by the American Board of Medical Specialties) versus the American Board of Cosmetic Surgery (which is not recognized by the American Board of Medical Specialties and includes nonsurgically trained doctors such as internists and dermatologists) demonstrated higher rates of disciplinary action against members of the latter group, illustrating the impact of quality of training.30,31 The increased demand for aesthetic procedures has led to a rise in complications, including severe filler-induced complications such as blindness or stroke.32 Many beauty service providers lack adequate training, posing a risk to patients. Ideally, only extensively trained, licensed healthcare professionals should administer cosmetic procedures. To improve patient safety, licensing bodies in the United Kingdom33 and Australia34 are tightening regulations for practitioner certifications.

OVERFILLED SYNDROME

The overzealous use of aesthetic treatments, such as dermal fillers, can result in visually striking outcomes. Referred to colloquially as the “overfilled face,” patients with this adverse outcome are characterized by excessively rounded apple cheeks, leaving the patient with a perpetual squint. The origin of this appearance is multifactorial, stemming from factors like inaccurate assessment, incorrect technique, poor choice of filler, and the cumulative effects of prior dermal filler administrations. A contributing behavioral factor to this has been referred to as “perception drift.”36 In settings where the overfilled aesthetic becomes prevalent, the distorted appearance transforms into the norm, potentially becoming an aesthetic ideal. With each successive treatment, gradual alterations accumulate, obscuring memory of the patient’s natural appearance.37 As exposure to manipulated features increases, our perception of attractiveness becomes distorted. This means aesthetic procedures, although potentially beneficial, can lead to negative societal views when performed without discretion.

MEDICAL MARKETING AND THE PHYSICIAN INFLUENCER

Social media raises ethical concerns with the rise of influencers promoting aesthetic procedures and physicians using these platforms for marketing. Because the digital realm operates beyond the scrutiny of peer-review, it is susceptible to the proliferation of misinformation.38 The informality inherent in social media platforms also provides a breeding ground for exaggerated claims and false information.39 Many influencers wield substantial online followings and are increasingly becoming a pivotal source of information about aesthetic treatments.40 Their role is to create engagement for the products or services they endorse,41 at times through the use of provocative content.42 There is rarely formal credential authentication for these influencers, making it challenging to discern what recommendations are evidence-based.42 Influencers strategically present themselves as reliable figures, cultivating an image of approachability and relatability. At the same time, some influencers foster unrealistic patient expectations by highlighting only the best outcomes and underreporting associated risks, complications, and the need for ongoing maintenance.43

Despite ethical challenges, social media is an essential medical marketing tool,44 allowing physicians to connect with and educate patients before appointments. The influence of online information is profound, with studies indicating that up to 70% of patients rely on the internet for evaluating plastic surgeons and understanding procedures.45 Although a social media presence can help physicians build trust with their patients, it also introduces a potential ethical quandary. This preexisting personal connection can make it difficult for physicians to say “no” to patients seeking treatments that are not appropriate.39,46 Patients often link extensive social media presence with professional skill, prompting ethical inquiries into physicians’ use of social media for service promotion.43

Misleading assertions have also been documented in online advertising, as evidenced by a recent study revealing the utilization of the terms “plastic surgeon” and “plastic surgery” by nonaccredited or board-certified practitioners on platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, and websites to describe their services.47 The evolving online interactions between aesthetic physicians and patients demand a proactive response from professional societies.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Medical aesthetics is rife with potential financial conflicts of interest.48 Its growing integration into the wellness and beauty industries attracts multiple industry stakeholders. Industry sponsorship of trials, gifts to physicians, and speaking fees are common,49,50 yet physicians often hesitate to disclose these relationships publicly, despite considering such gifts acceptable.42,51

Conflicting interests arise when external relationships begin to impact physicians’ decision-making processes. Studies show that financial conflicts of interest impact clinical practice, with one literature review revealing a seven-fold increased likelihood of presenting positive outcomes among industry-sponsored studies.52 Such conflicts also influence prescribing behaviors, as physicians receiving financial compensation from drugmakers prescribe specific drugs up to 58% more than those without such benefits.53 Personal finances, including ownership of surgical centers and variations in remuneration, have also been shown to influence treatment recommendations.54 Thus, financial relationships may compromise physicians’ objective decision-making.53

BEAUCHAMP AND CHILDRESS’ FOUR CORE ETHICAL PRINCIPLES AND AESTHETIC MEDICINE

The moral theory of principalism, introduced by Beauchamp and Childress in 1979, plays a pivotal role in guiding ethical discourses in various fields of medicine.55 This framework is anchored in four fundamental principles: respect for autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice. Beauchamp and Childress’ ethical principles have become a cornerstone of contemporary medical practice. Ethical dilemmas in medicine are impossible to fully anticipate, making core principles crucial for decision-making. Aesthetic practitioners must carefully balance patient autonomy with their well-being and equitable access to care when faced with ethical challenges. These principles and their applications within the context of aesthetic medicine are outlined in Table 1. Although adaptable, Beauchamp and Childress’ principles do not fully address the unique ethical challenges in aesthetics. Clear guidelines are needed to ensure a standardized foundation of ethical training for the diverse range of aesthetic practitioners. Such formal training on ethical principles may be of particular importance in the field of aesthetic medicine and plastic surgery.56 In the following section, we provide evidence-based recommendations as a starting point for promoting ethically-informed care and fostering greater patient trust in the field of aesthetic medicine.

Table 1.

Beauchamp and Childress’ Ethical Principles52 in the Context of Aesthetic Medicine

| Respect for Autonomy | |

|---|---|

| Definition | Patients have the right to privacy and decision-making in their care |

| Aesthetic applications | Informed consent and shared decision-making ensure patient values and privacy are respected |

| Example ethical challenge | Limited patient recall of risk and complications55,56; sharing patient images on social media platforms |

| Strategies | Comprehensive informed consent discussions,54 the “SHARE” Approach for shared decision-making,57 obtaining consent for the use of patient images on social media44 |

| Beneficence | |

| Definition | Moral obligation to provide treatments that benefit the patient |

| Aesthetic applications | Noninvasive treatments can improve patient concerns64–66 and offer psychological benfits67–69 |

| Example ethical challenge | Defining aesthetic “benefits” is challenging given the subjective nature of aesthetic outcomes and evolving beauty standards10 |

| Strategies | Use of validated patient-reported outcome measures like the FACE-Q Aesthetic module for aesthetic procedures13,70 |

| Nonmaleficence | |

| Definition | Treatments must not cause harm to the patient |

| Aesthetic applications | Practitioners must ensure that treatments are in the patient’s the best interest and avoid aesthetic procedures that are unnecessary or associated with excessive risk59 |

| Example ethical challenge | Excessive use of dermal fillers can lead to unnatural “overfilled” outcomes, distorting the patient’s and the public’s perceptions of “normal” or ideal35 |

| Strategies | Use of shared decision-making to understand patient goals,57 declining procedures that do not align with ethical practices or the patient’s best interests60 |

| Distributive justice | |

| Definition | Access to care should be equitable regardless of clinical or demographic factors |

| Aesthetic applications | The elective nature of aesthetic procedures introduces financial barriers, creating a two-tiered system that favors patients from higher socioeconomic backgrounds. |

| Example ethical challenge | Prioritization of appointments for high-paying clients71; off-label use of drugs such as semaglutide for weight loss, leading to drug shortages and cost inflation for diabetic patients72 |

| Strategies | Physicians should consider the boarder societal implications of their clinical decisions, exercising careful selection treatments and implementing creative strategies, such as payment plans, to ensure the affordability of care |

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR ETHICAL AESTHETIC PRACTICES

Guidelines for Informed Consent

Informed consent is foundational to patient autonomy. The current medical landscape has embraced the “reasonable patient” paradigm as the standard for disclosure of information during the informed consent process.57 Informed consent must include information a prudent patient needs to make decisions about treatment benefits, risks, and alternatives58 Studies highlight the importance of evaluating patient health literacy and tailoring information accordingly, ensuring alignment between decision-making and the informed consent process.59 This is of particular significance, as evidenced by a recent study indicating that 21% of plastic surgery patients within a singular facility had not completed their high school education. Additionally, 76% of physicians report encountering challenges in effectively communicating with patients from diverse cultural backgrounds.60

Optimal comprehension among surgical patients was observed when the informed consent process lasted 15–30 minutes.61 Using both oral and written communication also enhances patient recall.62 Consultations should be comprehensive, cover “off-label” treatment use, and allow ample time for patient concerns.63,64 Finally, the healthcare professional administering the procedure should be the one obtaining consent to ensure accurate information.

Strategies for Mitigating Appearance Anxiety

Aesthetic practitioners, although not directly responsible for societal appearance anxieties, must acknowledge their potential role in exacerbating such pressures. Caution is vital during consultations, as discussions of aesthetic concerns may unveil previously unrecognized anxieties in patients. As we navigate the ethical landscape of medical aesthetics, it is imperative to critically examine the impact of our language and practices on attitudes toward beauty and aging. We should move away from narrow beauty definitions, embracing diversity and dignity at all life stages. This can help mitigate unrealistic beauty standards and create a more inclusive society. As objective outcome measures emerge in aesthetics, it is crucial to validate these and ensure they don’t perpetuate unrealistic beauty standards.

Facilitating Effective Shared Decision-making

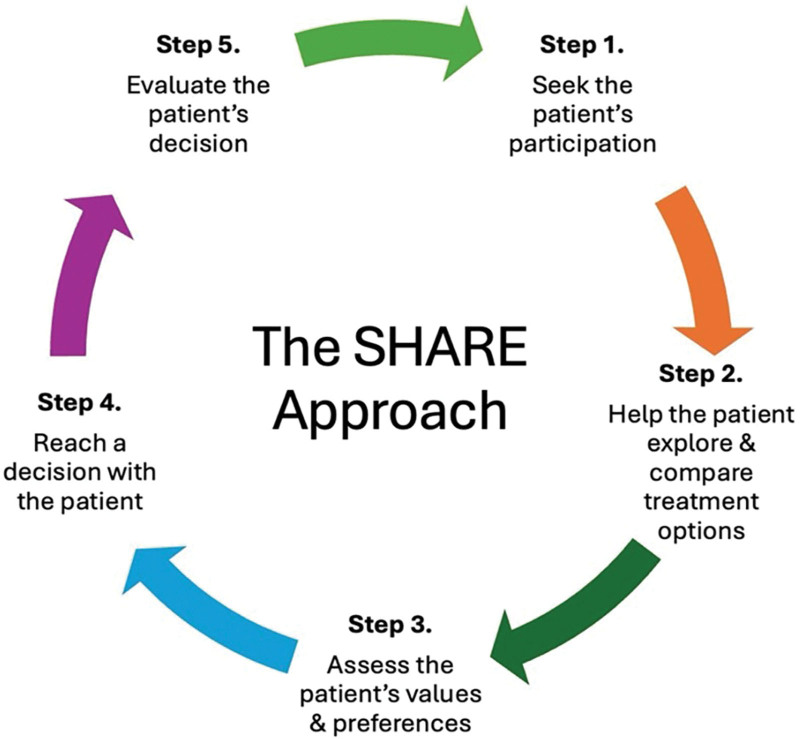

Shared decision-making is an integral element of patient-centered care. In this collaborative approach, the consultation is seen as a partnership between doctor and patient. In shared decision-making, patients share goals and preferences, and doctors offer expertise and clarify outcomes. Despite its importance, this collaborative approach is underutilized in aesthetics and other medical fields. To overcome these challenges, the US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality proposes the “SHARE” Approach as a structured methodology for shared decision-making (Fig. 2).65

Fig. 2.

This figure outlines the US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality SHARE Approach, designed to facilitate shared decision-making as applied to aesthetic medicine. Shared decision-making is fundamental to patient-centered care, as patients actively participate in the treatment planning process.

Shared decision-making is especially useful when negotiating with patients who request specific treatments. Despite the importance of patient autonomy, patients should not unduly influence physicians to undertake clinically unnecessary procedures. Herein lies a potential contradiction between patient autonomy and nonmaleficence. Aesthetic providers should decline a procedure if, in their professional judgment, it does not align with the patient’s realistic expectations and desired outcomes.66 Aesthetic physicians should guide patients towards their goals in a way that upholds professional and ethical standards.8 This involves careful evaluation to ensure that treatments truly serve the patient’s best interests.67 Understanding the patient’s aesthetic goals is key and may lead to recommending more effective treatment options. For example, in the case of patients requesting excessive filler treatments, the patient’s underlying concern with skin laxity may ultimately be corrected more effectively with surgical intervention outside the scope of nonsurgical aesthetic practice. In such situations, we recommend thorough discussions of the limitations of the patients’ desired treatment, setting expectations about realistic outcomes, and suggesting reasonable alternatives to achieve the patient’s goals.68 These discussions should be documented carefully.

Responsible Use of Social Media

Social media offers a powerful tool for education and patient connection, but aesthetic physicians must exercise caution to maintain professionalism. Separate personal and professional accounts are recommended.69 Accurately representing credentials is crucial, as patients rely on this for identifying reputable information sources.70 Ethical frameworks can guide content choices, emphasizing benefits, compliance, and informed consent for using patient photographs.46 Because patients often seek information online, the quality of content created by healthcare providers is of paramount importance. Noteworthy findings from recent studies indicate that the information presented on websites covering topics such as cosmetic injectables and breast implant selection surpasses the recommended educational criteria of sixth and eighth grade, as outlined by the American Medical Association and the National Institutes of Health, respectively.71,72 Finally, in compliance with legal standards,73 aesthetic professionals promoted by social media influencers must disclose any paid endorsements or discounted services provided to influencers.

CONCLUSIONS

Because of its focus on appearance-enhancing rather than life-saving treatments, aesthetic medicine faces a unique set of ethical constraints. As the field of aesthetic medicine continues to evolve, it is essential to reflect on the foundational principles of autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice as guides for navigating these challenges of aesthetic care. We have identified a concerning lack of well-defined ethical guidelines within the realm of aesthetic medicine. In light of this deficit, professional aesthetic societies must establish formal guidelines and ethical training standards for nonsurgical aesthetic providers to ensure the highest level of professionalism and patient well-being.

DISCLOSURE

The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We extend our deepest gratitude to Professor Kevin Chung for his invaluable inspiration in developing this project.

Footnotes

Published online 25 June 2024.

Disclosure statements are at the end of this article, following the correspondence information.

REFERENCES

- 1.Maio G. Ist die ästhetische Chirurgie überhaupt noch Medizin? Eine ethische Kritik [Is aesthetic surgery still really medicine? An ethical critique]. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2007;39:189–194; discussion 195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leclerc O, Peters N, Scaglione A, et al. From Extreme to Mainstream: the Future of Aesthetics Injectables; McKinsey & Company; 2021. Available at https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/life-sciences/our-insights/from-extreme-to-mainstream-the-future-of-aesthetics-injectables. Accessed January 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 3.2022 ASPS Procedural Statistics Release. Available at https://www.plasticsurgery.org/documents/News/Statistics/2022/plastic-surgery-statistics-report-2022.pdf. Published September 26, 2023. Accessed December 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller FG, Brody H, Chung KC. Cosmetic surgery and the internal morality of medicine. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 2000;9:353–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramirez SPB, Scherz G, Smith H. Characteristics of patients seeking and proceeding with non-surgical facial aesthetic procedures. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2021;14:197–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maisel A, Waldman A, Furlan K, et al. Self-reported patient motivations for seeking cosmetic procedures. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1167–1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dimitrov D, Kroumpouzos G. Beauty perception: a historical and contemporary review. Clin Dermatol. 2023;41:33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hostiuc M, Hostiuc S, Rusu MC, et al. Physician-patient relationship in current cosmetic surgery demands more than mere respect for patient autonomy-is it time for the anti-paternalistic model? Medicina. 2022;58:1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Archard D, Montgomery J, Caney S, et al. Cosmetic procedures: ethical issues. Available at https://www.nuffieldbioethics.org/assets/pdfs/Cosmetic-procedures-full-report.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed February 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liew S, Silberberg M, Chantrey J. Understanding and treating different patient archetypes in aesthetic medicine. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19:296–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Furnham A, Levitas J. Factors that motivate people to undergo cosmetic surgery. Can J Plast Surg. 2012;20:e47–e50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Narins RS, Brandt F, Leyden J, et al. A randomized, double-blind, multicenter comparison of the efficacy and tolerability of Restylane versus Zyplast for the correction of nasolabial folds. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:588–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klassen AF, Cano SJ, Scott A, et al. Measuring patient-reported outcomes in facial aesthetic patients: development of the FACE-Q. Facial Plast SurgAug. 2010; 26:303–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weinkle SH, Werschler WP, Teller CF, et al. Impact of comprehensive, minimally invasive, multimodal aesthetic treatment on satisfaction with facial appearance: the HARMONY study. Aesthet Surg J. 2018;38:540–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Voit M, Weiß M, Hewig J. The benefits of beauty—individual differences in the pro- attractiveness bias in social decision making. Curr Psychol. 2023;42:11388–11402. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jennifer SM, Amy S, Jacqueline H. Beauty, body image, and the media. In: Martha Peaslee L, ed. Perception of Beauty. IntechOpen; 2017:Ch. 8. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bueller H. Ideal facial relationships and goals. Facial Plast Surg. 2018;34:458–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang CWD, Calhoun KH. The changing definition of beauty. Facial Plast Surg. 2006;22:161–162. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Donizzetti AR. Ageism in an aging society: the role of knowledge, anxiety about aging, and stereotypes in young people and adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mele S, Cazzato V, Urgesi C. The importance of perceptual experience in the esthetic appreciation of the body. PLoS One. 2013;8:e81378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Love M, Saunders C, Harris S, et al. Redefining beauty: a qualitative study exploring adult women’s motivations for lip filler resulting in anatomical distortion. Aesthet Surg J. 2023;43:907–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Papapanou TK, Darviri C, Kanaka-Gantenbein C, et al. Strong correlations between social appearance anxiety, use of social media, and feelings of loneliness in adolescents and young adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20:4296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hawes T, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Campbell SM. Unique associations of social media use and online appearance preoccupation with depression, anxiety, and appearance rejection sensitivity. Body Image. 2020;33:66–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kang H, Kim H. Ageism and psychological well-being among older adults: a systematic review. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2022;8:23337214221087023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Araco A, Araco F, Raichi M. Clinical efficacy and safety of polynucleotides highly purified technology (PN-HPT) and cross-linked hyaluronic acid for moderate to severe nasolabial folds: a prospective, randomized, exploratory study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2023;22:146–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.GOURI PCL liquid skin booster. Available at https://gorgeousgouri.com/. Accessed January 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zargaran D, Zargaran A, Terranova T, et al. Profiling UK injectable aesthetic practitioners: a national cohort analysis. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2023;86:150–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Board of Facial Cosmetic Surgery. How to choose a provider for your injectable treatments. American Board of Facial Cosmetic Surgery. Available at https://ambrdfcs.org/blog/choosing-provider-for-injectable-treatments/. Published September 14, 2023. Accessed January 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Valiga A, Albornoz CA, Chitsazzadeh V, et al. Medical spa facilities and nonphysician operators in aesthetics. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:239–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gabrick K, Makhoul AT, Riccelli V, et al. Board certification in cosmetic surgery: an analysis of punitive actions. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2022;150:713–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Long EA, Gabrick K, Janis JE, et al. Board certification in cosmetic surgery: an evaluation of training backgrounds and scope of practice. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;146:1017–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soares DJ, Hynes SD, Yi CH, et al. Cosmetic filler–induced vascular occlusion: a rising threat presenting to emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med. 2024;83:59–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Royal College of Surgeons of England. Cosmetic surgery certification. Royal College of Surgeons of England. Available at https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/standards-and-research/standards-and-guidance/service-standards/cosmetic-surgery/certification/. Accessed January 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Medical Board Ahpra. Doctors on notice as cosmetic surgery practice and advertising changes come into effect. Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (Ahpra). Available at https://www.medicalboard.gov.au/News/2023-07-03-Cos-surgery-changes.aspx. Published July 3, 2023. Accessed January 1, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fakih N, Bertossi D, Vent J. The overfilled face. Facial Plast Surg. 2022;38:173–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sola C, Fabi S. Perception drift. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:1747–1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cotofana S, Gotkin RH, Frank K, et al. Anatomy behind the facial overfilled syndrome: the transverse facial septum. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:e16–e22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abroms LC. Public health in the era of social media. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(S2):S130–S131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith CP, George D. When is advertising a plastic surgeon’s individual “brand” unethical? AMA J Ethics. 2018;20:372–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boen M, Jerdan K. Growing impact of social media in aesthetics: Review and debate. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:45–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goanta C, Ranchordás S. The regulation of social media influencers: an introduction. In Goanta C, Ranchordas S. (eds), The Regulation of Social Media Influencers. Edward Elgar Publishing; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steinman MA, Shlipak MG, McPhee SJ. Of principles and pens: attitudes and practices of medicine housestaff toward pharmaceutical industry promotions. Am J Med. 2001;110:551–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Buzzaccarini G, Degliuomini RS, Borin M. The impact of social media-driven fame in aesthetic medicine: when followers overshadow science. Aesthet Surg J. 2023;43:NP807–NP808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shauly O, Marxen T, Goel P, et al. The new era of marketing in plastic surgery: a systematic review and algorithm of social media and digital marketing. Aesthet Surg J Open Forum. 2023;5:ojad024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wong WW, Gupta SC. Plastic surgery marketing in a generation of “tweeting.” Aesthet Surg J. 2011;31:972–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schoenbrunner A, Gosman A, Bajaj AK. Framework for the creation of ethical and professional social media content. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;144:118e–125e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen S, Makhoul AT, Janis JE, et al. Board certification in cosmetic surgery: an examination of online advertising practices. Ann Plast Surg. 2022;88(5 Suppl 5):S461–S465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zarei E, Ghaffari A, Nikoobar A, et al. Interaction between physicians and the pharmaceutical industry: a scoping review for developing a policy brief. Front Public Health. 2022;10:1072708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jia S, Brown D, Wall A, et al. Industry-sponsored clinical trials: the problem of conflicts of interest. Bull Am Coll Surg. 2013;98:32–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kjaergard LL, Als-Nielsen B. Association between competing interests and authors’ conclusions: epidemiological study of randomised clinical trials published in the BMJ. Br Med J. 2002;325:249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Madhavan S, Amonkar MM, Elliott D, et al. The gift relationship between pharmaceutical companies and physicians: an exploratory survey of physicians. J Clin Pharm Ther. 1997;22:207–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lopez J, Lopez S, Means J, et al. Financial conflicts of interest: an association between funding and findings in plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136:690e–697e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fresques H. Doctors prescribe more of a drug if they receive money from a pharma company tied to it. ProPublica. Available at https://www.propublica.org/article/doctors-prescribe-more-of-a-drug-if-they-receive-money-from-a-pharma-company-tied-to-it. Published December 20, 2019. Accessed January 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zbar RIS, Taylor LD, Canady JW. Ethical issues for the plastic surgeon in a tumultuous health care system: dissecting the anatomy of a decision. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122:1245–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 8th ed. Cary, NC: Oxford University Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Patrinely JR, Jr, Drolet BC, Perdikis G, et al. Ethics education in plastic surgery training programs. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;144:532e–533e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Spatz ES, Krumholz HM, Moulton BW. The new era of informed consent: getting to a reasonable-patient standard through shared decision making. JAMA. 2016;315:2063–2064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Beauchamp TL. Autonomy and consent. In: Miller F, Wertheimer A, eds. The Ethics of Consent: Theory and Practice. Oxford University Press; 2010:55–78:chapter 3. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tiourin E, Barton N, Janis JE. Health literacy in plastic surgery: a scoping review. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2022;10:e4247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barton N, Janis JE. Missing the mark: the state of health care literacy in plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2020;8:e2856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fink AS, Prochazka AV, Henderson WG, et al. Predictors of comprehension during surgical informed consent. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:919–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Makdessian AS, Ellis DA, Irish JC. Informed consent in facial plastic surgery: effectiveness of a simple educational intervention. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2004;6:26–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rohrich RJ, Janis JE, Reisman NR. Use of off-label and non-approved drugs and devices in plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112:241–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mithani Z. Informed consent for off-label use of prescription medications. Virtual Mentor. 2012;14:576–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.The SHARE Approach. Agency for healthcare research and quality. Available at https://www.ahrq.gov/health-literacy/professional-training/shared-decision/index.html. Updated March 2023. Accessed January 2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Eleanor M, Jennifer J. Rethinking autonomy and consent in healthcare ethics. In: Peter AC, ed. Bioethics. IntechOpen; 2016:Ch. 2. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nejadsarvari N, Ebrahimi A, Ebrahimi A, et al. Medical ethics in plastic surgery: a mini review. World J Plast Surg. 2016;5:207–212. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reisman NR. Ethics, legal issues, and consent for fillers. Clin Plast Surg. 2006;33:505–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kind T. Professional guidelines for social media use: a starting point. AMA J Ethics. 2015;17:441–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Branford OA, Kamali P, Rohrich RJ, et al. #PlasticSurgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;138:1354–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Patel AA, Joshi C, Varghese J, et al. Do websites serve our patients well? a comparative analysis of online information on cosmetic injectables. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2022;149:655e–668e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fanning JE, Okamoto LA, Levine EC, et al. Content and readability of online recommendations for breast implant size selection. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2023;11:e4787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.16 CFR Part 255: guides concerning the use of endorsements and testimonials in advertising. Federal Trade Commission. Federal Register/Vol. 88, No. 142/Wednesday, July 26, 2023/Rules and Regulations. Available at https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/07/26/2023-14795/guides-concerning-the-use-of-endorsements-and-testimonials-in-advertising. Accessed January 1, 2024. [Google Scholar]