Abstract

Background

Uncertainty and inconsistency in terminology regarding the risk factors (RFs) for in-hospital falls are present in the literature.

Objective

(1) To perform a literature review to identify the fall RFs among hospitalized adults; (2) to link the found RFs to the corresponding categories of international health classifications to reduce the heterogeneity of their definitions; (3) to perform a meta-analysis on the risk categories to identify the significant RFs; (4) to refine the final list of significant categories to avoid redundancies.

Methods

Four databases were investigated. We included observational studies assessing patients who had experienced in-hospital falls. Two independent reviewers performed the inclusion and extrapolation process and evaluated the methodological quality of the included studies. RFs were grouped into categories according to three health classifications (ICF, ICD-10, and ATC). Meta-analyses were performed to obtain an overall pooled odds ratio for each RF. Finally, protective RFs or redundant RFs across different classifications were excluded.

Results

Thirty-six articles were included in the meta-analysis. One thousand one hundred and eleven RFs were identified; 616 were linked to ICF classification, 450 to ICD-10, and 260 to ATC. The meta-analyses and subsequent refinement of the categories yielded 53 significant RFs. Overall, the initial number of RFs was reduced by about 21 times.

Conclusion

We identified 53 significant RF categories for in-hospital falls. These results provide proof of concept of the feasibility and validity of the proposed methodology. The list of significant RFs can be used as a template to build more accurate measurement instruments to predict in-hospital falls.

Keywords: risk factors, systematic review, meta-analysis, accidental falls, hospitals

1. Introduction

Falls are a growing and under-recognized public health issue. A recent WHO report (1) estimated that 684,000 fatal falls occur each year, making it the second leading cause of unintentional injury death after road traffic injuries. Many factors, including aging populations and sedentary lifestyles, will likely increase global fall-related injury rates in the next decades. Falls in hospital settings are among the most common hospital-acquired conditions and contribute to morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs (2). Fall rates among hospitalized adults show great global variability, ranging from 3 to 11 falls per 1,000 bed days (3, 4). In particular, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality reports an inpatient fall rate of 7.6 per 1,000 discharges or 227,000 falls in hospitals in the United States in 2017 (5). Around 25% of hospital falls are injurious, resulting in fractures, soft-tissue injuries, and fear of falling (6). Given the enormous individual, social, and healthcare costs, preventing in-hospital falls is a public health priority (7).

For effective prevention of in-hospital falls, the early identification of inpatients at risk of falling is crucial for any intervention to prevent in-hospital falls (8). For this reason, several fall-predicting tools have been developed to summarize the individual patient’s risk into one single number (9). However, a 2013 guideline from the National Institute of Health Care Excellence (NICE) reported that all the tools screened did not have sufficient sensitivity and specificity for accurate and reliable predictions, thus not recommending the use of these tools to predict the individual’s patient risk of falling (9). There may be several explanations for the low predictive accuracy of fall prediction tools. First, although many studies have been conducted to identify the causality of falls, a direct comparison of their results is difficult due to methodological issues, including retrospective designs, different study populations, and follow-up periods. Second, although older age and a history of past falls have been reported as the most important key predictors of future falls in older people (10), accidental falls are likely to result from a complex interaction of multiple risk factors. Indeed, in-hospital falls have been associated with demographic, physical, psychological, medical, socioeconomic, environmental, and behavioral factors (9, 11–13) that interact dynamically and can change over time and settings (14). Thus, the attempt to summarize a multidimensional construct’s complexity, such as the risk of falling into a single number, could be a misleading oversimplification leading to ineffective interventions (9). Third, more than 400 risk factors have been described (9). This plethora of risk factors suggests a lack of clarity, consistency, and consensus regarding risk factor definitions (15), as well as issues surrounding selecting risk factors to be included in a given tool.

On the other hand, using clear and consistent terminology for risk factors would likely reduce their number, thus making selecting the most relevant risk factors much easier. This, in turn, may lead to an improvement in the diagnostic accuracy of fall prediction tools. Indeed, a workable solution to overcome the inconsistencies in risk factor definitions could be to link them to standardized healthcare concepts, such as those provided by conceptual categories of international health classifications. In particular, the World Health Organization Family of International Classifications (WHO-FIC) (14) is a group of integrated classification systems to be used alone or jointly to establish a common language, allowing comparisons of data across countries’ healthcare services and providing a conceptual framework of information dimensions related to health and health management.

Thus, this study aimed to provide proof of concept that it may be feasible to significantly reduce the reported inconsistencies in the description of fall risk factors and, subsequently, their number by adopting the standard terminology provided by international health classifications. We planned to reach this overall aim in the following four steps: (1) to perform a literature review to identify the fall risk factors among hospitalized adults; (2) to link the found risk factors to the corresponding WHO Health Classifications’ categories to reduce the heterogeneity of their definitions; (3) to perform a meta-analysis on the risk categories identified in the previous step to identify the significant ones to reduce further the number of relevant risk factors for hospitalized falls (16); (4) to refine the final list of significant categories by removing redundancies to reduce the number of risk factors further.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Literature review

2.1.1. Search strategy

The search was performed on four electronic databases: PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus, and CINAHL. The search strategy adopted was similar across the databases. Particularly, it was developed using the following keywords: “accidental falls,” “falls,” “falls in hospitals,” “risk factors,” “fall risk factor,” “hospital,” “hospitalization,” “acute care,” and “adult” (see Supplementary Table S1 for the full search strings). Given the constraints of time and resources and the extensive volume of available literature on the topic, we decided to limit our search to studies on humans published in either English or Italian from January 2015 to March 2022. The search results were exported and compiled into a common reference database using a reference manager. References were then de-duplicated to derive a unique set of records.

2.1.2. Criteria for considering studies for this review

Amongst the retrieved references, we included primary studies evaluating risk factors for falls according to the following inclusion criteria:

Population: patients admitted to the hospital, of both genders, aged over 16 years;

Intervention: not applicable;

Comparison: not applicable;

Outcome: one or more fall(s) during the hospitalization;

Method: observational study.

To ensure comprehensive coverage and capture all relevant researchers, we screened all the primary studies included in any secondary studies we retrieved, thus including them if they met the above inclusion criteria.

2.1.3. Study selection and data extraction

Two investigators (EB and EG) independently examined the search results and screened the titles and abstracts to exclude irrelevant reports. A third reviewer (GV) solved any disagreement. The full text of the selected articles was retrieved and critically evaluated for eligibility, and their reference lists were manually scanned to identify further eligible studies. In the case of multiple publications from the same study, we selected the most updated one and extracted the data for the maximum possible length of follow-up.

From each of the included studies, the following data were extracted: author, study design, location, publication year, inclusion criteria, sample size, percentage of male/female, age, Odds Ratio (OR) or Relative Risk (RR) with its 95% Confidence Interval (95%CI). When the OR or the RR was not provided, we computed a crude OR if possible (17).

2.1.4. Qualitative assessment of selected studies

Four independent reviewers (AN, SM, VP, and GV) evaluated the methodological quality of each included study. Studies were assessed using tailored National Institute of Health (NIH) Quality assessment tools for Case–control studies and for Observational cohort and cross-sectional studies (18).

The checklist included 12 and 14 questions, respectively, for case–control and cross-sectional studies. Possible answers included “yes,” “no,” “not reported,” “cannot determine,” or “not applicable.” Each study was rated for its overall quality as “good,” ‘fair’, or ‘poor’, based on the significance of the risk of bias and the consequent internal validity of its results. For instance, if a study had a ‘fatal flaw,’ the given rating was ‘poor’.

2.2. Linking of risk factors to international health classification categories

2.2.1. Selection of health classifications

Fall risk factors are usually categorized into intrinsic (15) (medical conditions, multiple aspects of functioning, medications, personal factors) and extrinsic (environmental factors) factors. According to this initial conceptual framework categorization, within the WHO-FIC, we considered several classifications with a hierarchical structure (i.e., the more distal the category, the more detailed the health concept is). Thus, we considered the following classifications for linking:

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF, 2017 version) that includes specific categories for functioning/disability (body functions, body structures, activity, and participation) as well as environmental and personal factors;

The International Classification of Diseases version 10 (ICD-10), that includes specific categories for medical conditions (diagnoses);

The Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification (ATC) (19) for medications and drugs.

We excluded:

the International Classification of Diseases version 11 (ICD-11), as it was not yet available at the time of data analysis;

the International Classification of Nursing Practice (ICNP), given its polyhierarchical structure;

The International Classification of Health Interventions (ICHI), as it only provides extension codes linked either to ICF or ICD-11.

2.2.2. Linking risk factors to a health classification

The risk factors extracted from the literature review were then linked to three selected health classifications (ICF, ICD-10, and ATC), which were used as theoretical reference models. The linking was conducted by two clinicians (FLP, SC) who had almost 15 years of clinical and research experience in applying the ICF linking technique (20). They independently linked each extracted risk factor to one or more of the above classifications using a modified version of the standard linking techniques available for ICF (21). In particular, they employed an algorithm by which each risk factor was linked at least to one of the following definitions of health domains, which, in turn, identified the chosen classification:

b (body function): the physiological functions of body systems, including psychological functions (ICF);

s (body structure): anatomical parts of the body such as organs, limbs, and their components (ICF);

d (activity and participation): the execution of a task or action by an individual or an involvement in a life situation (ICF);

e (environmental factor): the physical, social, and attitudinal environment in which people live and conduct their lives (ICF);

pf (person factor): the particular background of an individual’s life and living, and comprise features of the individual that are not part of a health condition or health states (e.g., gender, race, age, other health conditions, fitness, lifestyle, habits, upbringing, coping styles, social background, education, profession, past and current experience, overall behavior pattern and character style, individual psychological assets and other characteristics [ICF]);

nd (not defined); any aspect of functioning, other than pf, not yet classified within the ICF;

hc (health condition): a diagnosis or a health condition (ICD);

dr (drug): any natural or human-made object or substance gathered, processed, or manufactured for medicinal purposes (ATC);

nc (not classifiable): any risk factor not classifiable according to any of the previous labels.

According to this algorithm, each risk factor could be linked to one or more classifications. A third reviewer (GL) solved any disagreement.

2.2.3. Linking risk factors to specific categories of health classifications

The next step was performed by three clinicians (FLP, SC, EG, and GL), who independently linked each risk factor to the appropriate categories of the identified classification. In particular, each risk factor was linked to the following hierarchical levels of each classification:

For ICF: 1st-level categories (chapters), blocks, and 2nd-level categories;

For ICD-10: chapters, blocks, categories, and subcategories;

For ATC: 1st-and 2nd-level categories.

In case of discrepancy about the linking outcome for some specific risk factors, the four investigators resolved by consensus, choosing together the most appropriate categories according to indications given by the latest version of the ICF linking rules (21).

2.3. Meta-analysis

As all risk factors were traced back to specific categories of the three international classifications, it was possible to aggregate the single factors within the same category and then carry out the meta-analyses. We estimated a pooled OR (based on OR for case–control and cross-sectional studies and on RR or hazard risk for cohort studies) for each risk factor using random effect models (22). The pooled OR was derived from the inverse variance method, which involved computing the weighted average using standard error. All meta-analyses were performed using Stata software (version 14) (23).

The meta-analyses were carried out using a bottom-up approach. The latter entailed starting the meta-analysis from the more ‘distal categories’ and proceeding subsequently with the more ‘proximal categories.’ In doing so, if the estimated pooled OR was not significant for a given category, all the linked risk factors were excluded from the meta-analysis of the upper-level category.

2.4. Refinement of the final list of significant risk factors

The significant risk factors linked to the various health classifications were then screened independently by two clinicians (FLP, SC) looking for redundancies (i.e., the same risk factors linked to categories of different classifications). When redundancies were found, just one category was retained according to the following criteria: most appropriate classification (i.e., ICD-10 for medical diagnosis vs. ICF for aspects of functioning), higher pooled OR, and higher number of selected studies. Finally, categories with pooled OR < 1 (protective factors) were excluded. Any disagreement was solved by a third reviewer (GL).

3. Results

3.1. Literature review

3.1.1. Study identification and selection

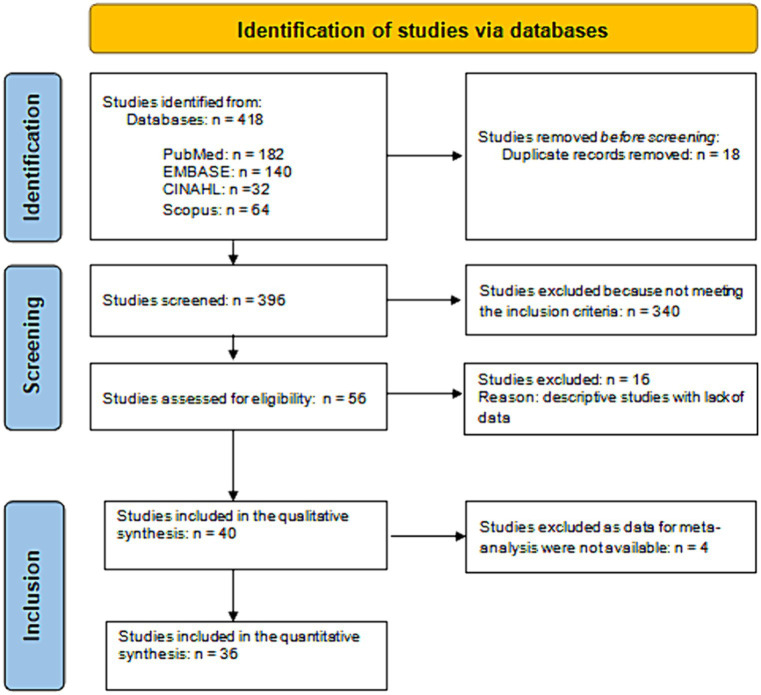

After excluding duplicates and irrelevant records, the literature search identified 400 references (Figure 1). Of these, 344 were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Thus, we found 56 studies eligible for inclusion and obtained full-text details. From full-text analysis, 16 further studies were excluded as descriptive studies with a lack of data. Therefore, 40 articles (24–63) were included in the qualitative synthesis, yielding 3,495,552 included patients.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the literature review.

3.1.2. Characteristics of the included studies

Amongst the 40 included studies, 19 were case–control, 9 were cross-sectional, and 12 were cohort studies. Detailed characteristics of the included studies are reported in Table 1. Most studies were conducted in the United States and had a mean/median cohort age < 80 years, with a prevalence of male subjects between 22.1 and 71.7%.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies investigating risk factors for falls.

| Study | Study design | Country | Publication year | Sample size | Inclusion criteria | Age (mean (SD)/median [Q1-Q3]) | Male n (%) | Study quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akgün et al. 2022 (23) | Cross sectional | Netherland | 2022 | 905 | Patients with age > 65 years | Falls: 82.0 [78.0–87.0] No Falls: 81.0 [76.0–85.0] |

437 (48.3%) | Fair |

| al Tehewy et al. 2015 (24) | Cross sectional | Egypt | 2015 | 411 | Patients with age > 60 years | 67.6 (6.7) | 224 (54.5%) | Good |

| Aranda-Gallardo et al. 2017 (25) | Cohort | Spain | 2017 | 977 | Patients with age > 16 years and length of stay longer than 48 h | 65.6 (17.6) | 518 (53.0%) | Good |

| Aryee et al. 2017 (26) | Case control | United Kingdom | 2017 | 437 | Adult patients | 67.7 (NR) | 246 (56.3%) | Fair |

| Brand & Sundararajan, 2010 (27) | Cohort | Australia | 2010 | 3,345,415 | Patients with age > 18 years and length of stay longer than 48 h | 75.9 (NR) | 1,392,936 (41.6%) | Fair |

| Chang et al. 2011 (29) | Case control | Taiwan | 2011 | 330 | Patients with aged ≥65 years | 76.2 (NR) | 200 (60.6%) | Good |

| Cho et al. 2020 (28) | Case control | Korea | 2020 | 1788 | Patients with age > 18 years | 61.0 (NR) | 985 (55.1%) | Good |

| Cox et al. 2017 (30) | Case control | United States | 2017 | 856 | Patients with age > 18 years and a diagnosis of a hematological malignancy | Falls: 64.7 (12.2) No Falls: 64.5 (14.0) |

453 (52.9%) | Fair |

| Eglseer et al. 2020 (31) | Cross sectional | Australia | 2020 | 3,702 | Patients with age > 65 years | 77.6 (7.6) | 1,676 (45.3%) | Poor |

| Fehlberg et al. 2017 (32) | Case control | United States | 2017 | 1888 | Adult patients | 63.1 (17.8) | 866 (45.6%) | Good |

| Forrest & Chen, 2016 (33) | Cross sectional | United States | 2016 | 2,524 | Patients admitted to an inpatient rehabilitation unit. |

64.3 (NR) | 1,312 (52%) | Good |

| Guzzo et al. 2015 (34) | Case control | Italy | 2015 | 152 | Patients admitted to a general hospital | 67 (NR) | 109 (71.7%) | Good |

| Hanger et al. 2014 (35) | Cross sectional | New Zealand | 2013 | 401 | Older patients (65 years and older) With stroke |

Falls: 79.1 [73.0–84.0] No Falls: 79.8 [74.0–85.0] |

185 (46.1%) | Poor |

| Hauer et al. 2020 (36) | Cohort | Germany | 2020 | 102 | Patients diagnosed with dementia | 82.8 (6.2) | 21 (20.6%) | Fair |

| Hou et al. 2017 (37) | Cohort | Taiwan | 2016 | 37,437 | Patients with age > 18 years and length of stay longer than 24 h | 56.2 (NR) | NR | Fair |

| Ishibashi et al. 2020 (38) | Case control | Japan | 2020 | 1,620 | Hospitalized patients who had their first fall |

76.2 (NR) | 770 (47.5%) | Fair |

| Ishikuro et al. 2017 (39) | Cross sectional | Japan | 2017 | 1,362 | Hospitalized patients | 57.1 (NR) | 637 (46.8%) | Good |

| Jung & Park, 2018 (40) | Case control | Korea | 2018 | 15,440 | Patients with age > 18 years | 58.3 (NR) | 8,331 (54%) | Good |

| Juraschek et al. 2019 (41) | Cohort | United States | 2019 | 3,973 | Participants without known coronary heart disease, heart failure, or stroke |

75.7 (5.0) | 1,510 (38%) | Good |

| Kim et al. 2019 (42) | Cohort | Korea | 2019 | 60,049 | Patients admitted to integrated care units |

61.2 (17.2) | 26,388 (43.9%) | Fair |

| Lackoff et al. 2020 (43) | Cohort | Australia | 2020 | 1849 | Patients with age > 18 years | 67 (18.3) | 1,043 (56.4%) | Good |

| Lucero et al. 2019 (44) | Case control | United States | 2019 | 814 | Patients with age > 18 years | 57.8 (NR) | 397 (49.0%) | Good |

| Magnuszewki et al. 2020 (45) | Cross sectional | Poland | 2020 | 358 | Patients, admitted for the first time to the department of geriatrics | 82 [76–86] | 79 (22.1%) | Fair |

| Mamun & Lim, 2009 (46) | Case control | Singapore | 2010 | 598 | Patients with age > 65 years | 75.8 (n.r) | 361 (60.4%) | Fair |

| Mazur et al. 2016 (47) | Cross sectional | Poland | 2016 | 788 | Geriatric patients | 79.5 | 268 (34.0%) | Fair |

| Morishita et al. 2022 (48) | Case control | Japan | 2022 | 508 | Patients with age > 18 years | Falls: 67.5 (14.3) No Falls: 67.5 (14.3) |

290 (57.1%) | Good |

| Najafpour et al. 2019 (49) | Case control | Iran | 2019 | 1,326 | Patients admitted to a general hospital | 57.8 (NR) | 708 (53.4%) | Poor |

| Nanda et al. 2011 (50) | Case control | United States | 2011 | 564 | Geriatric-psychiatric patients | 80.3 (NR) | 123 (54.7%) | Poor |

| Noh et al. 2021 (51) | Case control | Korea | 2021 | 620 | Patients with age > 55 years | Falls:73.7 (8.4) No Falls:73.6 (8.4) |

365 (58.9%) | Good |

| Obayashi et al. 2013 (52) | Cohort | Japan | 2013 | 3,683 | Hospitalized patients | 56.5 (20.2) | 1965 (53.4%) | Good |

| Oneil et al. 2018 (53) | Case control | United States | 2015 | 476 | Hospitalized patients | 59.5 (NR) | 446 (49.3%) | Good |

| Pauley et al. 2006 (54) | Cohort | Canada | 2006 | 1,267 | Inpatient rehabilitation patients with diagnosis of amputation | 66.7 (12.6) | 849 (67%) | Fair |

| Severo et al. 2018 (55) | Case control | Brazil | 2018 | 358 | Patients with age > 18 years | 58.9 (16.2) | 204 (54%) | Fair |

| Sullivan & Harding, 2019 (56) | Cohort | Australia | 2019 | 149 | Patients with stroke in rehabilitation | 75.6 (NR) | 85 (57%) | Good |

| Swartzell et al. 2013 (57) | Cross sectional | United States | 2013 | 107 | Patients aged 65 to 85 years | 75 (NR) | 44 (41%) | Fair |

| Toye et al. 2019 (58) | Cohort | Australia | 2019 | 397 | Patients with age > 70 years | 84.8 (7.2) | 169 (42.6%) | Good |

| Vela et al. 2018 (59) | Case control | United States | 2017 | 168 | Patients with age > 18 years | Falls: 56.6 (13.3) No Falls: 53.6 (11.3) |

93 (55.4%) | Fair |

| Wedmann et al. 2019 (60) | Case control | Germany | 2019 | 962 | Patients with age > 65 years | 82 (NR) | 396 (41.0%) | Fair |

| Yip et et al. 2016 (61) | Case control | Singapore | 2016 | 421 | Patients with age > 21 years | 65.1 (NR) | 249 (59.2%) | Fair |

| Yu et al. 2010 (62) | Cohort | Canada | 2010 | 370 | Patients undergoing lower limb amputation | Falls: 64.6 (16.2) No Falls: 65.0 (17.1) |

NR | Good |

SD, standard deviation; Q1, first quartile; Q3, third quartile; N, number, NR, not reported.

3.1.3. Methodological quality of the included studies

As shown in Table 1, the overall methodological quality of cross-sectional and cohort studies was classified as good (N = 10), fair (N = 9), and poor (N = 2) quality. All included studies clearly defined the research question and the outcome measures. Twenty studies (95%) specified the population and confounding variables, 15 (71%) studies had at least 50% of eligible participants, 17 (85%) reported that the subjects were recruited from similar populations, and 8 (40%) provided a sample size justification. The exposure of interest was measured before the outcome in 18 (90%) studies and was defined in 17 (81%) studies. Twelve studies (57%) examined different levels of exposure, 4 (19%) reported a timeframe sufficient to determine an association between exposure and outcome, and 3 (14%) assessed the exposure more than once. The blinding of the outcome assessor was reported in only one study, and 15 (71%) studies reported a loss to follow-up by 20% or less (Supplementary Table S2).

The overall methodological quality of case–control studies was good (N = 9), fair (N = 8), and poor (N = 2). All studies clearly defined the research question. All studies except one reported that the control subjects were recruited from similar populations that gave rise to the cases and clearly described the case population. Sixteen (84%) studies clearly explained the study population and reported using concurrent controls, but only 4 provided a sample size justification. Potential confounding variables were measured in 16 (84%) studies; 14 (74%) studies reported definitions, inclusion and exclusion criteria, or processes used to identify cases and controls, and 8 (42%) studies specified the random selection of case and control. The exposure/risk was clearly defined in 12 (63%) studies and occurred before the development of the condition in 13 (68%) studies. The assessor of exposure/risk was blinded to the case or controls in only two studies (Supplementary Table S3).

3.2. Linking of risk factors to international health classification categories

3.2.1. Linking risk factors to a health classification

The literature review yielded 1,111 different records. Table 2 shows that it was possible to link 896 records (80.6%) to one classification only, whereas the remaining 19.4% (n = 215) were linked to two classifications. The ICF was the classification with the highest number of uniquely linked records (401, 36.1%), followed by the ATC (260, 23.4%), and finally the ICD-10 (235, 21.1%). Besides, 215 records (19.4%) were linked to the ICF and ICD-10 classifications. ICF or ICD-10 shared no records with ATC (Table 2). As shown in Table 3, the ICF was the classification with the highest number of linked records (616), followed by ICD-10 (450) and ATC (260).

Table 2.

Outcome of the risk factor linking to health classifications.

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of records | 1,111 | |

| Not classified | 0 | 0.0% |

| Linked to one classification only | 896 | 80.6% |

| Linked to two classifications | 215 | 19.4% |

| Distribution by classification | ||

| ICF only | 401 | 36.1% |

| ICD10 only | 235 | 21.1% |

| ATC only | 260 | 23.4% |

| ICF and ICD10 | 215 | 19.4% |

| ICF and ATC | 0 | 0.0% |

| ICD10 and ATC | 0 | 0.0% |

N, number; %, percentage; ICF, International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health; ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases; ATC, Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification.

Table 3.

Outcome of the risk factor linking to health classifications (detailed view by category level).

|

N records |

N categories |

N 1st-level categories |

N blocks |

N 2nd-level categories |

N 3rd-level categories |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICF | ||||||

| N categories | 616 | 105 | 15 | 18 | 63 | 9 |

| N records per category | ||||||

| Minimum value | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Median | 34 | 13 | 4 | 4 | ||

| Maximum value | 329 | 52 | 64 | 17 | ||

| ICD-10 | ||||||

| N categories | 450 | 131 | 17 | 57 | 57 | - |

| N records per category | ||||||

| Minimum value | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | ||

| Median | 13 | 3 | 3 | - | ||

| Maximum value | 84 | 67 | 38 | - | ||

| ATC | ||||||

| N categories | 260 | 82 | 9 | - | 41 | 32 |

| N records per category | ||||||

| Minimum value | 3 | - | 1 | 1 | ||

| Median | 11 | - | 3 | 2 | ||

| Maximum value | 115 | - | 48 | 19 |

N, number; ICF, International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health; ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases; ATC, Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification.

3.2.2. Linking risk factors to specific categories of health classifications

As shown in Table 3, the 616 ICF records were linked to 105 categories, divided into 15 first-level, 18 blocks, 63 s-level, and nine third-level categories, yielding a median of 34, 13, 4, and 4 records. Following the linking procedure, it was possible to link the 450 ICD-10 records to 131 categories. In particular, we identified 17 first-level, 57 blocks, and 57 s-level categories, with a median of 13, 3, and 3 records. Finally, the 260 ATC records could be linked to 82 categories: nine were first-level, 41 were second-level, and 32 were third-level categories. The median values of linked records for the three types of categories were, respectively, 11, 3, and 2.

The ICD-10 was the classification with the highest number of linked categories (131), followed by ICF (105) and ATC (82). The linkage process allowed the grouping of the 1,111 initial records into 152 risk factors with an overall 7.3 reduction factor.

3.3. Meta-analysis

The number of articles included in the quantitative synthesis was 36, as four articles had to be excluded because they had no data usable for the meta-analysis (Figure 1). Table 4 shows the significant combined ORs for the risk factors linked to the ICF classification. In particular, the meta-analysis identified 52 risk factors as non-significant (Supplementary Table S4). On the other hand, 50 risk factors linked to 523 records could be identified as significant. Their OR values ranged from 0.022 (b280-b289 Pain) to 8.633 (d420 Transferring oneself).

Table 4.

Significant risk factors linked to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health.

| Risk factor | N records | OR | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b1 Mental Functions | 63 | 2.133 | 1.630 | 2.793 | <0.001 | |||

| b110-b139 Global Mental Functions | 36 | 1.978 | 1.602 | 2.441 | <0.001 | |||

| b110 Consciousness functions | 9 | 3.660 | 2.637 | 5.079 | <0.001 | |||

| b114 Orientation functions | 5 | 3.214 | 2.692 | 3.837 | <0.001 | |||

| b117 Intellectual functions | 17 | 3.984 | 1.867 | 8.499 | <0.001 | |||

| b140-189 Specific Mental Functions | 27 | 2.334 | 1.506 | 3.618 | <0.001 | |||

| b140 Attention functions | 1 | 3.981 | 1.345 | 11.784 | 0.013 | |||

| b147 Psychomotor functions | 5 | 4.761 | 3.271 | 6.930 | <0.001 | |||

| b164 Higher-level cognitive functions | 8 | 2.570 | 1.668 | 3.961 | <0.001 | |||

| b180 Experience of self and time functions | 1 | 4.010 | 2.865 | 5.612 | <0.001 | |||

| b2 Sensory functions and pain | 24 | 2.796 | 1.429 | 5.472 | 0.003 | |||

| b210-b229 Seeing and related functions | 8 | 3.867 | 1.643 | 9.103 | 0.002 | |||

| b210 Seeing functions | 8 | 3.867 | 1.643 | 9.103 | 0.002 | |||

| b230-b249 Hearing and vestibular function | 14 | 3.391 | 2.040 | 5.634 | <0.001 | |||

| b230 Hearing functions | 4 | 2.744 | 1.524 | 4.940 | 0.001 | |||

| b240 Sensations associated with hearing and vestibular function | 10 | 3.840 | 1.609 | 9.166 | 0.002 | |||

| b250-b279 Additional sensory functions | 1 | 2.768 | 1.126 | 6.804 | 0.027 | |||

| b265 Touch function | 1 | 2.768 | 1.126 | 6.804 | 0.027 | |||

| b280-b289 Pain | 1 | 0.022 | 0.018 | 0.028 | <0.001 | |||

| b280 Sensation of pain | 1 | 0.022 | 0.018 | 0.028 | <0.001 | |||

| b4 Functions of the cardiovascular, haematological, immunological, and respiratory systems | 14 | 1.264 | 1.149 | 1.390 | <0.001 | |||

| b410-b429 Functions of the cardiovascular system | 9 | 1.168 | 1.001 | 1.363 | 0.049 | |||

| b430-b439 Functions of the haematological ann immunological system | 5 | 1.431 | 1.235 | 1.583 | <0.001 | |||

| b430 Haematological system functions | 2 | 1.366 | 1.063 | 1.756 | 0.015 | |||

| b435 Immunological system function | 3 | 1.366 | 1.139 | 1.639 | 0.001 | |||

| b5 Functions of the digestive, metabolic and endocrine systems | 33 | 1.363 | 1.136 | 1.636 | 0.001 | |||

| b510-b539 Functions related to the digestive system | 16 | - | - | - | n.s. | |||

| b525 Defecation functions | 1 | 4.209 | 1.571 | 11.278 | 0.004 | |||

| b540-b559 Functions related to metabolism and endocrine system | 17 | 1.532 | 1.258 | 1.867 | <0.001 | |||

| b540 General metabolic functions | 11 | 1.432 | 1.123 | 1.825 | 0.004 | |||

| b5401 Carbohydrate metabolism | 11 | 1.432 | 1.123 | 1.825 | 0.004 | |||

| b545 Water, mineral and electrolyte balance functions | 4 | 1.764 | 1.443 | 2.157 | <0.001 | |||

| b5452 Electrolyte balance | 4 | 1.764 | 1.443 | 2.157 | <0.001 | |||

| b7 Neuromuscoloskeletal and movement-related functions | 20 | 2.005 | 1.506 | 2.670 | <0.001 | |||

| b730-b749 Muscle functions | 8 | 1.728 | 1.077 | 2.775 | 0.023 | |||

| b730 Muscle power functions | 8 | 1.728 | 1.077 | 2.775 | 0.023 | |||

| b750-b789 Movement functions | 12 | 2.195 | 1.641 | 2.935 | <0.001 | |||

| b755 Involuntary movement reaction functions | 8 | 1.960 | 1.413 | 2.720 | <0.001 | |||

| b770 Gait pattern functions | 4 | 3.184 | 1.674 | 6.053 | <0.001 | |||

| d4 Mobility | 24 | 2.127 | 1.532 | 2.953 | <0.001 | |||

| d410-d429 Changing and maintaining body position | 3 | 3.186 | 1.039 | 9.767 | 0.043 | |||

| d420 Transferring oneself | 1 | 8.633 | 4.449 | 16.751 | <0.001 | |||

| d450-d459 Walking and moving | 21 | 2.006 | 1.411 | 2.853 | <0.001 | |||

| d450 Walking | 21 | 2.006 | 1.411 | 2.853 | <0.001 | |||

| d5 Self-care | 4 | 2.911 | 1.060 | 7.994 | 0.038 | |||

| d510 Washing oneself | 1 | 6.159 | 3.381 | 11.217 | <0.001 | |||

| e1 Products and technology | 41 | - | - | - | n.s. | |||

| e110 Products or substances for personal consumption | 18 | 1.556 | 1.196 | 2.024 | 0.001 | |||

| e120 Products and technology for personal indoor and outdoor mobility and transportation | 4 | 3.420 | 1.349 | 8.674 | 0.010 | |||

| nd Not Defined | 2 | 1.660 | 1.043 | 2.644 | 0.033 | |||

| Frailty | 2 | 1.660 | 1.043 | 2.644 | 0.033 | |||

N, number; OR, odds ratio, CI, confidence interval, n.s., non-significant.

The combined ORs for the risk factors linked to the ICD-10 classification are reported in Table 5. Specifically, 101 risk factors were identified as non-significant (Supplementary Table S5). Fifty-one significant risk factors were reported for a total of 509 records; the pooled OR values ranged from 0.199 (M00-M99 Unspecified diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue) to 3.789 (Y74.1 Therapeutic (nonsurgical) and rehabilitative devices).

Table 5.

Significant risk factors linked to the International Classification of Diseases 10.

| Risk factor | N records | OR | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 02 Neoplasms | 10 | 1.619 | 1.442 | 1.818 | <0.001 | |||

| C00-C97 Malignant neoplasms | 10 | 1.619 | 1.442 | 1.818 | <0.001 | |||

| C76-C80 Malignant neoplasms of ill-defined, secondary and unspecified sites | 7 | 1.581 | 1.430 | 1.748 | <0.001 | |||

| 03 Diseases of the blood and blood forming organs… | 3 | 1.366 | 1.100 | 1.695 | 0.005 | |||

| D60-D64 Aplastic and other anaemias | 3 | 1.366 | 1.100 | 1.695 | 0.005 | |||

| D64 Other anaemias | 3 | 1.366 | 1.100 | 1.695 | 0.005 | |||

| 04 Endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases | 30 | 1.336 | 1.109 | 1.608 | 0.002 | |||

| E10-E14 Diabetes mellitus | 11 | 1.432 | 1.123 | 1.825 | 0.004 | |||

| E14 Unspecified diabetes mellitus | 11 | 1.432 | 1.123 | 1.825 | 0.004 | |||

| E70-E90 Metabolic disorders | 4 | 1.764 | 1.443 | 2.157 | <0.001 | |||

| E86 Volume depletion | 1 | 1.921 | 1.370 | 2.700 | 0.0002 | |||

| E87 Other disorders of fluid, electrolyte and acid–base balance | 3 | 1.747 | 1.312 | 2.326 | <0.001 | |||

| 05 Mental and Behavioral disorders | 63 | 2.079 | 1.583 | 2.731 | <0.001 | |||

| F00-F09 Organic, includic symptomatic, mental disorders | 50 | 2.336 | 1.724 | 3.165 | <0.001 | |||

| F00 Dementia in Alzheimer disease | 1 | 0.242 | 0.134 | 0.438 | <0.001 | |||

| F05 Delirium, not induced by alcohol and other psychoactive substances | 26 | 3.310 | 2.616 | 4.186 | <0.001 | |||

| F06 Other mental disorders due to brain damage and dysfunction and to physical disease | 10 | 2.080 | 1.008 | 4.292 | 0.047 | |||

| 06 Diseases of the nervous system | 17 | 1.499 | 1.043 | 2.153 | 0.029 | |||

| G20-G26 Extrapyramidal and movement disorders | 7 | 2.647 | 1.502 | 4.666 | 0.001 | |||

| G20 Parkinson’s disease | 7 | 2.647 | 1.502 | 4.666 | 0.001 | |||

| G40-G47 Episodic and paroxysmal disorders | 4 | 1.759 | 1.013 | 3.053 | 0.045 | |||

| G40 Epilepsy | 1 | 2.785 | 1.851 | 4.190 | <0.001 | |||

| G80-G83 Cerebral palsy and other paralytic syndromes | 1 | 3.106 | 2.952 | 3.268 | <0.001 | |||

| G82 Paraplegia and tetraplegia | 1 | 3.106 | 2.952 | 3.268 | <0.001 | |||

| 09 Disease of the circulatory system | 40 | 1.211 | 1.024 | 1.432 | 0.025 | |||

| I30-I52 Other forms of heart disease | 10 | 1.343 | 1.046 | 1.723 | 0.021 | |||

| I50 Heart failure | 9 | 1.384 | 1.071 | 1.789 | 0.013 | |||

| I70-I79 Diseases of arteries, arterioles and capillaries | 3 | 1.501 | 1.351 | 1.666 | <0.001 | |||

| I70 Atherosclerosis | 3 | 1.501 | 1.351 | 1.666 | <0.001 | |||

| K70-K77 Diseases of the liver | 2 | 1.943 | 1.752 | 2.156 | <0.001 | |||

| K76 Other diseases of the liver | 2 | 1.943 | 1.752 | 2.156 | <0.001 | |||

| K00-K93 Unspecified disease of the digestive system | 1 | 0.541 | 0.343 | 0.852 | 0.003 | |||

| M05-M14 Inflammatory polyarthropaties | 3 | 1.692 | 1.250 | 2.292 | 0.001 | |||

| M12 Other specific arthropaties | 3 | 1.692 | 1.250 | 2.292 | 0.001 | |||

| M15-M19 Artrhosis | 1 | 3.726 | 1.360 | 10.250 | 0.002 | |||

| M19 Other arthrosis | 1 | 3.726 | 1.360 | 10.250 | 0.002 | |||

| M30-M36 Systemic connective tissue disorder | 1 | 1.387 | 1.215 | 1.530 | <0.001 | |||

| M35 Other systemic involvement of connective tissue | 1 | 1.387 | 1.215 | 1.530 | <0.001 | |||

| M00-M99 Unspecified diseases of the muscoloskeletal system and connective tissue | 3 | 0.199 | 0.046 | 0.853 | 0.030 | |||

| 18 Symptoms, signs, and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings | 33 | 2.040 | 1.684 | 2.470 | <0.001 | |||

| R25-R29 Symptoms and signs involving the nervous and musculoskeletal systems | 25 | 2.211 | 1.774 | 2.754 | <0.001 | |||

| R29 Other symptoms and signs involving the nervous and musculoskeletal systems | 25 | 2.211 | 1.774 | 2.754 | <0.001 | |||

| R29.6 Tendency to fall, not elsewhere classified | 25 | 2.211 | 1.774 | 2.754 | <0.001 | |||

| R50-R69 General symptoms and signs | 6 | 1.498 | 1.258 | 1.784 | <0.001 | |||

| R55 Syncope and collapse | 1 | 2.170 | 1.077 | 4.371 | 0.030 | |||

| R65 Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome | 5 | 1.462 | 1.221 | 1.751 | <0.001 | |||

| 19 Injury, poisoning and certain other consequences of external causes | 10 | 1.304 | 1.021 | 1.666 | 0.034 | |||

| T08-T14 Injuries to unspecified part of trunk, limb or body region | 5 | 1.390 | 1.048 | 1.844 | 0.022 | |||

| 20 External causes of morbidity and mortality | 14 | - | - | - | n.s. | |||

| W00-X59 Other external causes of accidental injury | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| W19 Unspecified Falls | 1 | 2.650 | 1.313 | 5.350 | 0.007 | |||

| Y70-Y82 Medical devices associated with adverse incidents in diagnostic and therapeutic use | 13 | - | - | - | n.s. | |||

| Y74 General hospital and personal-use devices associated with adverse incidents | 13 | - | - | - | n.s. | |||

| Y74.1 Therapeutic (nonsurgical) and rehabilitative devices | 3 | 3.789 | 1.359 | 10.560 | 0.011 | |||

| 21 Factors influencing health status and contact with health services | 42 | - | - | - | n.s. | |||

| Z40-Z54 Persons encountering health services for specific procedures and health care | 29 | - | - | - | n.s. | |||

| Z50 Care involving use of rehabilitation procedures | 3 | 2.913 | 2.788 | 3.045 | <0.001 | |||

N, number; OR, odds ratio, CI, confidence interval; n.s., non-significant. Note: for simplicity, the Roman numerals in ICD10 have been replaced by Arabic numerals.

Table 6 shows the combined ORs for the risk factors linked to the ATC classification. After excluding 65 risk factors because they were non-significant (Supplementary Table S6), the metanalyses yielded twenty-six significant risk factors for 294 records. The pooled OR values ranged from 0.348 (G04C Drugs used in benign prostatic hypertrophy) to 8.609 (B01AD Enzymes).

Table 6.

Significant risk factors linked to the anatomical therapeutic chemical classification.

| Risk factor | N records | OR | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A Alimentary tract and metabolism | 23 | - | - | - | n.s. |

| A02 drugs for acid-related disorders | 3 | - | - | - | n.s. |

| A02A Antacids | 1 | 0.690 | 0.501 | 0.950 | 0.023 |

| A04 Antiemetics | 3 | 0.691 | 0.557 | 0.858 | 0.001 |

| A04A Antiemetics and antinauseants | 1 | 0.610 | 0.450 | 0.827 | 0.001 |

| A07 Antidiarrheal, intestinal antiinflammatory/antiinfective agents | 2 | 1.874 | 1.324 | 2.651 | <0.001 |

| A10 Drugs used in diabetes | 6 | 1.939 | 1.205 | 3.120 | 0.006 |

| B Blood and blood forming organs | 10 | - | - | - | n.s. |

| B01 Antithrombotic agents | 10 | - | - | - | n.s. |

| B01AD Enzymes | 1 | 8.609 | 3.486 | 21.264 | <0.001 |

| C Cardiovascular system | 56 | - | - | - | n.s. |

| C03 Diuretics | 11 | - | - | - | n.s. |

| C03D Potassium-sparing agents | 2 | 0.556 | 0.375 | 0.827 | 0.004 |

| G Genito-urinary system and sex hormones | 3 | - | - | - | n.s. |

| G04 Urologicals | 2 | - | - | - | n.s. |

| G04C Drugs used in benign prostatic hypertrophy | 1 | 0.348 | 0.131 | 0.922 | 0.034 |

| L Antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents | 5 | - | - | - | n.s. |

| L01 Antineoplastic agents | 2 | 2.165 | 1.331 | 3.520 | 0.002 |

| M Muscolo-skeletal system | 7 | - | - | - | n.s. |

| M03 Muscle relaxants | 1 | 0.430 | 0.279 | 0.663 | <0.001 |

| N Nervous System | 100 | 1.661 | 1.411 | 1.956 | <0.001 |

| N02 Analgesics | 15 | 1.521 | 1.018 | 2.274 | 0.041 |

| N02B Other analgesics and antipyretics | 1 | 0.646 | 0.427 | 0.976 | 0.038 |

| N03 Antiepileptics | 12 | 2.009 | 1.508 | 2.677 | <0.001 |

| N05 Psycholeptics | 44 | 1.829 | 1.566 | 2.138 | <0.001 |

| N05A Antipsychotic | 17 | 1.862 | 1.439 | 2.411 | <0.001 |

| N05B Anxiolytics | 12 | 1.930 | 1.572 | 2.369 | <0.001 |

| N05C Hypnotics and sedatives | 15 | 1.685 | 1.193 | 2.380 | 0.003 |

| N06 Psychoanaleptics | 18 | 1.331 | 1.007 | 1.760 | 0.045 |

| N06A Antidepressants | 13 | 1.299 | 1.045 | 1.613 | 0.018 |

| R Respiratory system | 14 | - | - | - | n.s. |

| R01 Nasal preparation | 1 | 0.520 | 0.324 | 0.835 | 0.007 |

| R03 Drugs for obustructive airway disease | 6 | 0.790 | 0.662 | 0.943 | 0.009 |

| R03B Other drugs for obstruct airway diseases, inhalants | 2 | 0.660 | 0.511 | 0.851 | 0.001 |

| R05 Cough and cold preparation | 1 | 5.949 | 1.725 | 20.521 | 0.005 |

N, number; OR, odds ratio, CI, confidence interval; n.s., non-significant.

In summary, the meta-analyses allowed the initial risk factors to be reduced from 152 to 71, i.e., a 2.1 reduction factor.

3.4. Refinement of the final list of significant risk factors

Table 7 reported the combined ORs after deleting 18 categories because they were redundant or protective factors. In particular, eleven factors were excluded because they were protective (one, three, and seven were linked to ICF, ICF-10, and ATC), whereas seven (five from ICF and two from ICD-10) were excluded because they were deemed redundant.

Table 7.

Refinement of the final list of significant risk factors.

| CL | Proximal category | Intermediate category | Distal category | Notes | Rec | OR | L 95% CI | U 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICF | b1 Mental functions | b110-b139 Global Mental Functions | b110 Consciousness functions | – | 9 | 3.660 | 2.637 | 5.079 | <0.001 |

| ICF | b1 Mental functions | b110-b139 Global Mental Functions | b114 Orientation functions | – | 5 | 3.214 | 2.692 | 3.837 | <0.001 |

| ICF | b1 Mental functions | b110-b139 Global Mental Functions | b117 Intellectual functions | – | 17 | 3.984 | 1.867 | 8.499 | <0.001 |

| ICF | b1 Mental functions | b140-189 Specific Mental Functions | b140 Attention functions | – | 1 | 3.981 | 1.345 | 11.784 | 0.013 |

| ICF | b1 Mental functions | b140-189 Specific Mental Functions | b147 Psychomotor functions | 5 | 4.761 | 3.271 | 6.930 | <0.001 | |

| ICF | b1 Mental functions | b140-189 Specific Mental Functions | b164 Higher-level cognitive functions | – | 8 | 2.570 | 1.668 | 3.961 | <0.001 |

| ICF | b1 Mental functions | b140-189 Specific Mental Functions | b180 Experience of self and time functions | – | 1 | 4.010 | 2.865 | 5.612 | <0.001 |

| ICF | b2 Sensory functions and pain | b210-b229 Seeing and related functions | b210 Seeing functions | – | 8 | 3.867 | 1.643 | 9.103 | 0.002 |

| ICF | b2 Sensory functions and pain | b230-b249 Hearing and vestibular function | b230 Hearing functions | – | 4 | 2.744 | 1.524 | 4.940 | 0.001 |

| ICF | b2 Sensory functions and pain | b230-b249 Hearing and vestibular function | b240 Sensations associated with hearing and vestibular function | – | 10 | 3.840 | 1.609 | 9.166 | 0.002 |

| ICF | b2 Sensory functions and pain | b250-b279 Additional sensory functions | b265 Touch function | – | 1 | 2.768 | 1.126 | 6.804 | 0.027 |

| ICF | b5 Functions of the digestive, metabolic and endocrine systems | b510-b539 Functions related to the digestive system | b525 Defecation functions | – | 1 | 4.209 | 1.571 | 11.278 | 0.004 |

| ICF | b7 Neuromuscoloskeletal and movement-related functions | b730-b749 Muscle functions | b730 Muscle power functions | – | 8 | 1.728 | 1.077 | 2.775 | 0.023 |

| ICF | b7 Neuromuscoloskeletal and movement-related functions | b750-b789 Movement functions | b755 Involuntary movement reaction functions | – | 8 | 1.960 | 1.413 | 2.720 | <0.001 |

| ICF | b7 Neuromuscoloskeletal and movement-related functions | b750-b789 Movement functions | b770 Gait pattern functions | – | 4 | 3.184 | 1.674 | 6.053 | <0.001 |

| ICF | d4 Mobility | d410-d429 Changing and maintaining body position | d420 Transferring oneself | – | 1 | 8.633 | 4.449 | 16.751 | <0.001 |

| ICF | d4 Mobility | d450-d459 Walking and moving | d450 Walking | – | 21 | 2.006 | 1.411 | 2.853 | <0.001 |

| ICF | d5 Self-care | – | d510 Washing oneself | – | 1 | 6.159 | 3.381 | 11.217 | <0.001 |

| ICF | e1 Products and technology | – | e110 Products or substances for personal consumption | Polypharmacotherapy | 18 | 1.556 | 1.196 | 2.024 | 0.001 |

| ICF | e1 Products and technology | – | e120 Products and technology for personal indoor and outdoor mobility and transportation | – | 4 | 3.420 | 1.349 | 8.674 | 0.010 |

| ICF | nd Not Defined | – | Frailty | – | 2 | 1.660 | 1.043 | 2.644 | 0.033 |

| ICD10 | 02 Neoplasms | C00-C97 Malignant neoplasms | C76-C80 Malignant neoplasms of ill-defined, secondary and unspecified sites | Malignant neoplasms | 7 | 1.581 | 1.430 | 1.748 | <0.001 |

| ICD10 | 03 Diseases of the blood and blood forming organs… | D60-D64 Aplastic and other anaemias | D64 Other anaemias | Anemias | 3 | 1.366 | 1.100 | 1.695 | 0.005 |

| ICD10 | 04 Endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases | E10-E14 Diabetes mellitus | E14 Unspecified diabetes mellitus | Diabetes mellitus | 11 | 1.432 | 1.123 | 1.825 | 0.004 |

| ICD10 | 04 Endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases | E70-E90 Metabolic disorders | E86 Volume depletion | – | 1 | 1.921 | 1.370 | 2.700 | 0.0002 |

| ICD10 | 04 Endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases | E70-E90 Metabolic disorders | E87 Other disorders of fluid, electrolyte and acid–base balance | Hyponatriemia | 3 | 1.747 | 1.312 | 2.326 | <0.001 |

| ICD10 | 06 Diseases of the nervous system | G20-G26 Extrapyramidal and movement disorders | G20 Parkinson’s disease | – | 7 | 2.647 | 1.502 | 4.666 | 0.001 |

| ICD10 | 06 Diseases of the nervous system | G40-G47 Episodic and paroxysmal disorders | G40 Epilepsy | – | 1 | 2.785 | 1.851 | 4.190 | <0.001 |

| ICD10 | 06 Diseases of the nervous system | G80-G83 Cerebral palsy and other paralytic syndromes | G82 Paraplegia and tetraplegia | – | 1 | 3.106 | 2.952 | 3.268 | <0.001 |

| ICD10 | 09 Disease of the circulatory system | I30-I52 Other forms of heart disease | I50 Heart failure | – | 9 | 1.384 | 1.071 | 1.789 | 0.013 |

| ICD10 | 09 Disease of the circulatory system | I70-I79 Diseases of arteries, arterioles and capillaries | I70 Atherosclerosis | – | 3 | 1.501 | 1.351 | 1.666 | <0.001 |

| ICD10 | 11 Disease of the digestive system | K70-K77 Diseases of the liver | K76 Other diseases of the liver | Liver disease | 2 | 1.943 | 1.752 | 2.156 | <0.001 |

| ICD10 | 13 Disease of the musculo-skeletal system and connective tissue | M05-M14 Inflammatory polyarthropaties | M12 Other specific arthropaties | Osteoarthritis, arthritis | 3 | 1.692 | 1.250 | 2.292 | 0.001 |

| ICD10 | 13 Disease of the musculo-skeletal system and connective tissue | M15-M19 Artrhosis | M19 Other arthrosis | History of joint replacement | 1 | 3.726 | 1.360 | 10.250 | 0.002 |

| ICD10 | 13 Disease of the musculo-skeletal system and connective tissue | M30-M36 Systemic connective tissue disorder | M35 Other systemic involvement of connective tissue | Connective tissue disease | 1 | 1.387 | 1.215 | 1.530 | <0.001 |

| ICD10 | 18 Symptoms, signs, and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings | R25-R29 Symptoms and signs involving the nervous and musculoskeletal systems | R29.6 Tendency to fall, not elsewhere classified | – | 25 | 2.211 | 1.774 | 2.754 | <0.001 |

| ICD10 | 18 Symptoms, signs, and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings | R50-R69 General symptoms and signs | R55 Syncope and collapse | – | 1 | 2.170 | 1.077 | 4.371 | 0.030 |

| ICD10 | 18 Symptoms, signs, and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings | R50-R69 General symptoms and signs | R65 Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome | Markers of acute infections (i.e., fever, leucocytosis, increased CRP) | 5 | 1.462 | 1.221 | 1.751 | <0.001 |

| ICD10 | 19 Injury, poisoning and certain other consequences of external causes | – | T08-T14 Injuries to unspecified part of trunk, limb or body region | Fractures, lower limb amputation | 5 | 1.390 | 1.048 | 1.844 | 0.022 |

| ICD10 | 19 Injury, poisoning and certain other consequences of external causes | Y70-Y82 Medical devices associated with adverse incidents in diagnostic and therapeutic use | Y74.1 Therapeutic (nonsurgical) and rehabilitative devices | Devices, e.g., bed restraints, bedrails, handrails, lines, tubes, drains, etc | 3 | 3.789 | 1.359 | 10.560 | 0.011 |

| ICD10 | 20 External causes of morbidity and mortality | W00-X59 Other external causes of accidental injury | W19 Unspecified Falls | Recent fall; fall as presenting complaint | 1 | 2.650 | 1.313 | 5.350 | 0.007 |

| ICD10 | 21 Factors influencing health status and contact with health services | Z40-Z54 Persons encountering health services for specific procedures and health care | Z50 Care involving use of rehabilitation procedures | Involvement in rehabilitation | 3 | 2.913 | 2.788 | 3.045 | <0.001 |

| ATC | A Alimentary tract and metabolism | – | A07 Antidiarrheals, intestinal antiinflammatory / antiinfective agents | – | 2 | 1.874 | 1.324 | 2.651 | <0.001 |

| ATC | A Alimentary tract and metabolism | – | A10 Drugs used in diabetes | – | 6 | 1.939 | 1.205 | 3.120 | 0.006 |

| ATC | B Blood and blood forming organs | B01 Antithrombotic agents | B01AD Enzymes | i.e., Trombolytic agents | 1 | 8.609 | 3.486 | 21.264 | <0.001 |

| ATC | L Antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents | – | L01 Antineoplastic agents | – | 2 | 2.165 | 1.331 | 3.520 | 0.002 |

| ATC | N Nervous System | – | N02 Analgesics | – | 15 | 1.521 | 1.018 | 2.274 | 0.041 |

| ATC | N Nervous System | – | N03 Antiepileptics | – | 12 | 2.009 | 1.508 | 2.677 | <0.001 |

| ATC | N Nervous System | N05 Psycholeptics | N05A Antipsychotic | – | 17 | 1.862 | 1.439 | 2.411 | <0.001 |

| ATC | N Nervous System | N05 Psycholeptics | N05B Anxiolytics | – | 12 | 1.930 | 1.572 | 2.369 | <0.001 |

| ATC | N Nervous System | N05 Psycholeptics | N05C Hypnotics and sedatives | – | 15 | 1.685 | 1.193 | 2.380 | 0.003 |

| ATC | N Nervous System | N06 Psychoanaleptics | N06A Antidepressants | – | 13 | 1.299 | 1.045 | 1.613 | 0.018 |

| ATC | R Respiratory system | – | R05 Cough and cold preparation | – | 1 | 5.949 | 1.725 | 20.521 | 0.005 |

| Excluded categories | |||||||||

| ICF | b2 Sensory functions and pain | b280-b289 Pain | b280 Sensation of pain | Protective factor | 1 | 0.022 | 0.018 | 0.028 | <0.001 |

| ICF | b4 Functions of the cardiovascular, haematological, immunological, and respiratory systems | b410-b429 Functions of the cardiovacular system | – | Overlap with I50 and I70 | 9 | 1.168 | 1.001 | 1.363 | 0.049 |

| ICF | b4 Functions of the cardiovascular, haematological, immunological, and respiratory systems | b430-b439 Functions of the haematological and immunological system | b430 Haematological system functions | Overlap with D64 ICD-10 | 2 | 1.366 | 1.063 | 1.756 | 0.015 |

| ICF | b4 Functions of the cardiovascular, haematological, immunological, and respiratory systems | b430-b439 Functions of the haematological anndimmunological system | b435 Immunological system function | Overlap with R65 of ICD-10 | 3 | 1.366 | 1.139 | 1.639 | 0.001 |

| ICF | b5 Functions of the digestive, metabolic and endocrine systems | b540 General metabolic functions | b5401 Carbohydrate metabolism | Overlap with E14 of ICD-10 | 11 | 1.432 | 1.123 | 1.825 | 0.004 |

| ICF | b5 Functions of the digestive, metabolic and endocrine systems | b545 Water, mineral and electrolyte balance functions | b5452 Electrolyte balance | Overlap with E86 and E87 of ICD-10 | 4 | 1.764 | 1.443 | 2.157 | <0.001 |

| ICD10 | 05 Mental and Behavioral disorders | F00-F09 Organic, includic symptomatic, mental disorders | F00 Dementia in Alzheimer disease | Protective factor | 1 | 0.242 | 0.134 | 0.438 | <0.001 |

| ICD10 | 05 Mental and Behavioral disorders | F00-F09 Organic, includic symptomatic, mental disorders | F05 Delirium, not induced by alcohol and other psychoactive substances | Overlap with categories mapping onto b1 of ICF | 26 | 3.310 | 2.616 | 4.186 | <0.001 |

| ICD10 | 05 Mental and Behavioral disorders | F00-F09 Organic, includic symptomatic, mental disorders | F06 Other mental disorders due to brain damage and dysfunction and to physical disease | Overlap with categories mapping onto b1 of ICF | 10 | 2.080 | 1.008 | 4.292 | 0.047 |

| ICD10 | 09 Disease of the circulatory system | K00-K93 Unspecified disease of the digestive system | – | Protective factor | 1 | 0.541 | 0.343 | 0.852 | 0.003 |

| ICD10 | 09 Disease of the circulatory system | M00-M99 Unspecified diseases of the muscoloskeletal system and connective tissue | – | Protective factor | 3 | 0.199 | 0.046 | 0.853 | 0.030 |

| ATC | A Alimentary tract and metabolism | A02 drugs for acid-related disorders | A02A Antacids | Protective factor | 1 | 0.690 | 0.501 | 0.950 | 0.023 |

| ATC | A Alimentary tract and metabolism | A04 Antiemetics | A04A Antiemetics and antinauseants | Protective factor | 1 | 0.610 | 0.450 | 0.827 | 0.001 |

| ATC | C Cardiovascular system | C03D Potassium-sparing agents | – | Protective factor | 2 | 0.556 | 0.375 | 0.827 | 0.004 |

| ATC | G Genito-urinary system and sex hormones | G04 Urologicals | G04C Drugs used in benign prostatic hypertrophy | Protective factor | 1 | 0.348 | 0.131 | 0.922 | 0.034 |

| ATC | M Muscolo-skeletal system | M03 Muscle relaxants | – | Protective factor | 1 | 0.430 | 0.279 | 0.663 | <0.001 |

| ATC | R Respiratory system | R01 Nasal preparation | – | Protective factor | 1 | 0.520 | 0.324 | 0.835 | 0.007 |

| ATC | R Respiratory system | R03 Drugs for obustructive airway disease | R03B Other drugs for obstruct airway diseases, inhalants | Protective factor | 2 | 0.660 | 0.511 | 0.851 | 0.001 |

CL, classification; Rec, records; OR, odds ratio; L, lower; CI, confidence interval; U, upper. For simplicity, the Roman numerals in ICD10 have been replaced by Arabic numerals.

After this process, the purified list included 53 significant risk factors corresponding to 328 records. Of those risk factors, ICF and ICD-10 yielded twenty-one risk factors each, whereas the remaining eleven were linked to ATC. The pooled OR values of the purified risk factors list ranged from 1.299 (N06A Antidepressants) to 8.633 (d420 Transferring oneself). This final step, reducing the number of risk factors from 71 to 53, added a further 1.3 reduction factor. Overall, the whole process from meta-analysis to post-meta-analysis refinement reduced the initial set of 1,111 records to a final set of 53 significant risk factors, i.e., a 21 times reduction of the initial number.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to provide a proof of concept that it may be feasible to reduce the reported heterogeneity in the description of fall risk factors and, subsequently, their number by adopting the standard terminology provided by international health classifications. We achieved this aim in four subsequent steps. In particular, we first performed a literature review to identify the fall risk factors among hospitalized adults. After the study selection and their methodological evaluation, we linked the found risk factors to the corresponding ICF, ICD, and ATC health classifications categories, obtaining the first relevant reduction of the number of health concepts representing the found risk factors. Following this step, we performed a meta-analysis on these risk categories, identifying the significant ones, thus further reducing the number of categories. The post-meta-analysis refinement from linking redundancies and protective risk factors allowed us to enlist a final set of 53 risk factors across the three classifications, achieving a remarkable 21-reduction factor from the initial number of records. These results provided the proof of concept regarding the feasibility and validity of the proposed methodology.

This proof-of-concept study aimed to reduce the heterogeneity of fall risk factors by adopting a standard terminology provided by international health classifications. Thus, the first step was reviewing the literature, as in previous works, although we used a different approach to the study selection of earlier studies. For instance, Deandrea et al. included only studies with a prospective design, a sample size greater than 200 subjects, and subjects experiencing one or more falls during follow-up as an outcome (12). Furthermore, they considered only risk factors assessed by at least three studies. Following this selection, they found only six significant risk factors for hospital falls from 22 selected studies. This number of found risk factors is approximately in the same range as the number of items of some of the most common risk prediction tools [i.e., Stratify, Hendrick fall risk model II, Morse Fall scale, and Conley scale (64)], whose use was not recommended by the National Institute of Health Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines in 2013 (9), given their insufficient sensitivity and specificity for accurate and reliable predictions. On the other hand, our approach allowed us to enlist a final much larger set of risk factors (i.e., 53 distal-level categories vs. 6), thus possibly providing a more extensive content coverage of the ‘fall risk for inpatients’ phenomenon. We achieved this goal by adopting less restrictive criteria for study inclusion than those adopted by Deandrea et al. (12). In particular: (a) we included any observational study design without any low limitation for sample rather than just prospective studies with sample size >200 subjects as Deandrea et al. (12); (b) furthermore, while Deandrea et al. (12) selected only studies with 80% or more patients aged 65 years or older, we included studies conducted on inpatients of 16 years or older and excluded studies devoted only to nursing home residents. Thus, the selected sample will likely better represent the hospital inpatient population.

In the phase of extrapolating the risk factors from the selected studies, the extreme heterogeneity of these risk factors was immediately evident in terms of variability of the type of language used to define them and the methods of quantifying them. Indeed, we found great variability regarding the language used to describe them (which was not always consistent) and the methods used to quantify them as a risk factor, as they were different between the studies (e.g., the age defined by unequal classes for numbers of years or beyond a specific age). This extreme heterogeneity made the linking work quite complex and strengthened the need to develop a common terminology.

The linking process with the WHO Health Classifications was the core of this novel proof-of-concept study. We employed a modified version of the standard linking techniques available for the ICF, with different degrees of difficulty depending on the classification used. Regarding the ICF and the ATC, the association between fall risk factors and categories was relatively straightforward, as each risk factor could be linked to one of the 2nd-level categories of the two classifications. On the other hand, the same process with the ICD-10 was more complex because this classification has very specific categories and subcategories. In contrast, some risk factors were somehow too generic. Furthermore, as already reported, several risk factors could be linked to categories of different classifications (e.g., mental functions vs. corresponding diagnoses).

Indeed, the main outcome of the whole linking procedure is the empirical demonstration that the risk of falling is a multidimensional construct (9, 11, 12), with likely interactions between its various biological, behavioral, environmental, and socioeconomic dimensions, as proposed by the World Health Organization’s risk factor model for falls in older age (65). The multidimensionality of the fall risk construct emerged even within the ICF classification. Within the latter, we were able to link risk factors to different aspects of functioning, such as functions, activities, environmental, and personal factors, which are likely to interact with one another.

Amongst the functions, we identified various aspects of impairments of the cognitive functions (i.e., consciousness, orientation, intellectual, attention, psychomotor, higher-level), with OR ranging from 2.57 to 4.76. Our results are in line with those of Deandrea et al. (12), although they identified only one variable related to cognitive impairment, as quantified with the Mini-Mental State Examination and with a lower OR (1.52). Besides, further systematic reviews (without meta-analysis) reported these aspects as significant in determining falls (15, 66, 67), as well as the NICE guidelines (9). We also identified categories related to sensory impairments with high OR, such as alteration of the seeing function (OR: 3.86), confirmed by Todd et al.’s report (15) and by the NICE guidelines (9). This risk factor was reported by Deandrea et al. (12) as non-significant within the nursing home setting, although impaired vision can prevent, for instance, seeing obstacles along the way, causing trips, or correctly perceiving the distance from a chair in the postural change from standing to sitting. At the same time, we also found high OR for risk factors (i.e., dizziness and vertigo) linked to impairments of hearing and vestibular functions. Deandrea et al. (12) also identified these impairments with significant OR (1.52), although only for the nursing home setting, as other already cited studies (15, 67). Amongst the functions, we also identified the impairment of defecation that may lead to slips, trips and falls, especially if characterized by urge continence in association with sensory, cognitive, and/or motor deficits (68).

We found other significant risk factors (OR range: 1.73–8.63) linked to motor functions and activities, such as impairments of muscle power, involuntary movement reactions, gait patterns, transfers, walking, and washing oneself. Indeed, an impairment of the cognitive, sensory, and/or motor functions is likely to lead to the most recognized risk factors for falling (69), such as transfers and washing oneself, which yielded the highest OR (8.63 and 6.16, respectively). These activities have already been described in the literature as exposing patients to a greater risk of falling (9, 13, 15, 66, 67). In particular, safe transfers require executing a series of subsequent steps (e.g., bringing the wheelchair to the bed, placing both brakes, etc.) that may be difficult to perform in case of concurrent sensory, cognitive, or motor impairments. Those impairments may easily lead to lower limb failure during standing with subsequent falls. On the other hand, washing oneself is associated with an increased risk of falling if coupled with water spillage on the floor, leading to a slip and subsequent loss of balance.

Among the ICF environmental factors, walking and mobility aids could be linked to one significant ICF environmental category (e120). This finding could be explained considering that the use of these aids is often seen in older patients with impaired gait who often assume psychotropic medications (70). Interestingly, this risk factor was reported by Todd et al. (15) and found to be significant by Deandrea et al. (12) only within the nursing home population. This is probably due to the larger scope of our literature review compared to the more restrictive one of Deandrea et al. (12), as mentioned previously. Within ICF’s environmental factors, we could also link up to 278 medication records to just one category (i.e., e110). However, considering the need to distinguish between classes of medications, we decided to link to e110 only the 18 records that were not specifically linkable to a drug class (e.g., ‘polypharmacotherapy’).

In contrast, we linked the remaining 260 records to specific categories of the ATC classification. In this way, we were able to find significant ORs for several classes of medications, such as alimentary tract and metabolism medications (i.e., antidiarrheal and drugs for diabetes), thrombolytic agents, antineoplastic agents, several classes of psychotropic medications (i.e., analgesics, antiepileptics, anxiolytics, hypnotic and sedatives, and antidepressants), and preparations for coughs and colds. Sedatives and antidepressants were also identified as prominent risk factors by Deandrea et al. (12) and by further authors in systematic reviews without meta-analysis (13, 15, 66). Given their interference with several body functions, these medications are likely associated with fall risk. For instance, psychotropic drugs are likely to have a direct impact on cognitive and motor functions (71). In contrast, antithrombotic agents (whose OR was the highest one within the various ATC classes) are likely to have an indirect impact, as these medications are used in acute stroke that, in turn, leads to sensory, cognitive, and motor impairments. Also, cough and cold preparations were associated with a high OR: this could be explained considering that these medications often contain codeine, which is an opiate known to interfere with cognitive functioning.

Amongst the personal factors, De Andrea et al. (12), in their systematic review and meta-analysis of risk factors in older people in nursing homes and hospitals, used an ad hoc statistical method for risk factors requiring a dose–response analysis (e.g., age), which allowed their comparison even when reported in different ways between studies. However, as we included more studies (36 vs. 22), we found significant heterogeneity in how age was reported between studies. In particular, in those where age was expressed as categories that could be homogenously dichotomized (e.g., in ≤70 or > 70 years), the OR was 1.25 (95%CI: 0.33–4.77). In contrast, when age was reported as a continuous variable, the pooled OR was 0.11 (95%CI: −0.06–0.27). In both cases, the pooled OR were not statistically significant. Our results also showed that both genders were not associated with a significantly increased risk of falls, as the OR was 1.11 (95%CI: 0.94–1.32) for males and 0.75 (95%CI: 0.48–1.15) for females.

We were able to find further significant fall risk factors, such as Parkinson’s disease, epilepsy, paraplegia, and tetraplegia, which were linked to the ICD-10 (OR range: 1.76–3.11). All these factors are classified as diseases of the nervous system that cause motor and balance impairment, which can easily be associated with an increased fall risk (10). We also found other pathologies linked to the ICD-10, like diabetes mellitus or malignant neoplasms, associated with significant risk factors (OR 1.43 and 1.62, respectively). Although these pathologies are traditionally considered risk factors by themselves, we should consider that they may increase fall risk indirectly by acting upon the various aspects of functioning described by ICF. For instance, patients with diabetes mellitus may suffer from diabetic neuropathy that is characterized by motor (i.e., b730) and sensitive impairments (b265). Also, patients with diabetes may suffer from visual function impairments (b210) (15). In the most extreme cases, a severe diabetic neuropathy associated with arterial vasculopathy (I70) may lead to limb amputations (T18-T14), which exposes the subject to a further increase in the risk of falling (67). Also, malignant tumors, especially in an advanced stage, can cause severe muscle weakness (b730), which in turn exposes the patient to the risk of falling (13). We also found an OR above 2 for a history of falls, which is confirmed to be one of the most frequently reported risk factors for inpatient falls (9, 13, 15, 66, 67). As discussed by De Andrea et al. (12), this is not a causal factor but probably a manifestation of real underlying causal agents, such as impaired balance.

The last step of this novel proof-of-concept approach was a qualitative refinement undertaken post-meta-analysis. The latter regarded: (1) the removal of one of the conceptually overlapping categories between ICF and ICD-10 and (2) the deletion of modifiable risk factors found to be protective. The latter choice was in line with the main goal of this work, which was focused on fall risk factors rather than on factors to prevent falls. Furthermore, it would make little sense to include protective risk factors that are either health conditions or aspects of functioning that could not be replicated (e.g., dementia) or would be unethical to replicate if not present (e.g., pain) or even medications (e.g., antacids, antiemetics, medication for benign prostatic hypertrophy) that may not be appropriate to administer to an individual outside of the recommended prescribing indications.

There are other published systematic reviews related to fall risk factors within the hospital (13, 66, 67) and/or the nursing home setting (15). Some of these reviews reported as significant risk factors anti-hypertensive drugs (13, 67) and diuretics usage [13; 15; 65], urinary incontinence (13, 15, 66), age (15, 67, 72), and having had a stroke (15, 67, 73). On the other hand, other studies did not report at all factors related to blood pressure functions (66), neither age nor stroke (13), and gave evidence of the use of diuretics (67) as a non-significant risk factor. Our results did not confirm the significance of several well-known fall risk factors such as those related to b420 blood pressure functions (i.e., hypertension, orthostatic hypotension and related medications), b6 genitourinary and reproductive functions (i.e., urinary incontinence, use of a urinary catheter, and renal insufficiency), to personal factors (i.e., age), and I60-I69 cerebrovascular diseases (i.e., stroke). Therefore, we excluded them from the final risk factor list.

These discrepancies between our results and those of the studies mentioned above should be viewed in light of the different methodologies applied. In particular, those studies included one literature report (15) and three systematic reviews (13, 66, 67), but none of them performed a meta-analysis. Indeed, those studies reported the significance of certain fall risk factors only according to the reports of single primary studies, without verifying the actual significance across the various studies by performing a quantitative synthesis of the results. On the other hand, the only study that conducted a meta-analysis (Deandrea et al.) reported only age as a significant hospital risk factor. In contrast, hypertension, orthostatic hypotension and related medications did not even meet the criteria to perform the meta-analysis. Furthermore, urinary incontinence and stroke resulted as non-significant risk factors within the meta-analysis conducted for the nursing home setting (12). In other words, with the exception of age, our results can be considered quite in line with those from the only study where a quantitative analysis (i.e., a meta-analysis) was performed (12).

This study has further limitations that should be highlighted. First, we included only articles published in English and Italian; thus, possibly relevant articles in different languages were not included in our literature review. Second, although we adopted some of the standards provided by the PRISMA statement, our literature review cannot be considered systematic. In particular, we included some primary studies, but not all of them were published before 2015. We also performed a literature search limited to four but not all available databases (e.g., PsychINFO and Web of Science were not included). Besides, we did not perform an accurate risk-of-bias assessment, including the publication bias. However, it should be pointed out that the units of analysis were the risk factors and not the studies, and therefore, it made little sense to investigate this bias. Third, as the outcome detection was implemented with different modalities across the selected studies, this issue might have influenced our results. Finally, the suboptimal quality of some of the included studies may have negatively affected some of the risk factors found.

Notwithstanding these limitations, this proof-of-concept study demonstrated that adopting a clear and consistent terminology derived from standardized international classifications may lead to a marked reduction and systematization of fall risk factors among hospitalized adults. Even though preventing in-hospital falls is a public health priority (7), current evidence suggests there are neither valid instruments for predicting fall risk factors (9) nor ultimate effective interventions to reduce falls for inpatients (74). Thus, the larger set of risk factors proposed here may be useful for critically appraising the content coverage of existing tools for predicting falls, developing better prediction tools, and, likely, novel therapeutic interventions to prevent falls in future research. Finally, once refined, the methodology adopted within this work may pave the way toward developing a standardized taxonomy of fall risk factors. This will undoubtedly improve the reporting of fall risk factors and the methodological quality of future studies exploring the assessment of risk factors and interventions to reduce in-hospital falls.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

FP: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GV: Formal analysis, Investigation, Software, Writing – review & editing. GL: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. AN: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Software, Writing – review & editing. LP: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. EB: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. SC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. VP: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. EG: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding Statement

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1390185/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Step Safely: Strategies for Preventing and Managing Falls Across the Life-Course. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hendrich AL, Bufalino A, Groves C. Validation of the Hendrich II fall risk model: the imperative to reduce modifiable risk factors. Appl. Nurs. Res. (2020) 53:151243. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2020.151243, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]