Abstract

Background

TNF (tumor necrosis factor)‐alpha inhibitors block a key protein in the inflammatory chain reaction responsible for joint inflammation, pain, and damage in ankylosing spondylitis.

Objectives

To assess the benefit and harms of adalimumab, etanercept, golimumab, and infliximab (TNF‐alpha inhibitors) in people with ankylosing spondylitis.

Search methods

We searched the following databases to January 26, 2009: MEDLINE (from 1966); EMBASE (from 1980); the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2008, Issue 4); ACP Journal Club; CINAHL (from 1982); and ISI Web of Knowledge (from 1900). We ran updated searches in May 2012, October 2013, and in June 2014 for McMaster PLUS. We searched major regulatory agencies for safety warnings and clinicaltrials.gov for registered trials.

Selection criteria

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing adalimumab, etanercept, golimumab and infliximab to placebo, other drugs or usual care in patients with ankylosing spondylitis, reported in abstract or full‐text.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently assessed search results, risk of bias, and extracted data. We conducted Bayesian mixed treatment comparison (MTC) meta‐analyses using WinBUGS software. To investigate a class‐effect of harms across biologics, we pooled harms data using Review Manager 5.

Main results

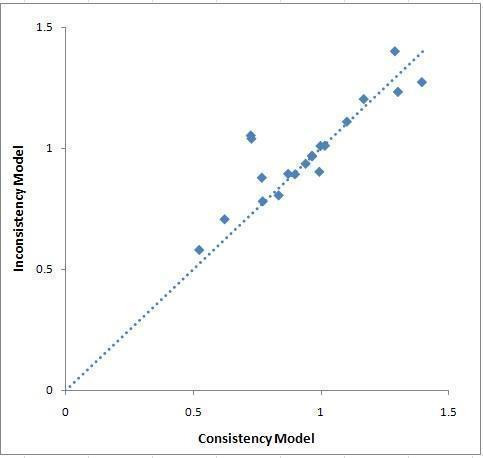

We included twenty‐one, short‐term (24 weeks or less) RCTs with a total of 3308 participants; 18 contributed data to the MTC analysis: adalimumab (4 studies), etanercept (8 studies), golimumab (2 studies), infliximab (3 studies), and one head‐to‐head study (etanercept versus infliximab) which was unblinded and considered at a higher risk of bias. The risk of selection and detection bias was low or unclear for most of the studies. The risk of selective outcome reporting was low for most studies as they reported on outcomes recommended by the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society. We found little heterogeneity and no significant inconsistency in the MTC analyses. The majority of the studies were funded by pharmaceutical companies. Most studies permitted concomitant therapy of stable doses of disease‐modifying anti‐rheumatic drugs, non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs, or corticosteroids, but allowances varied across studies.

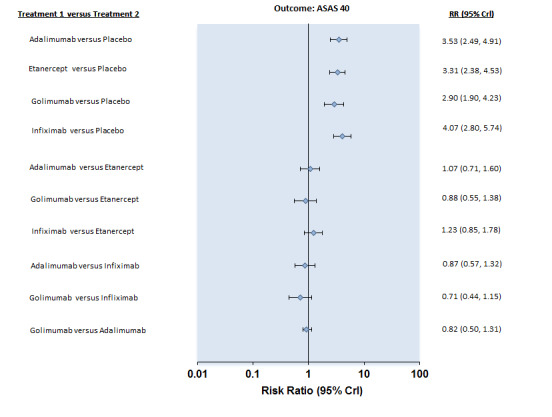

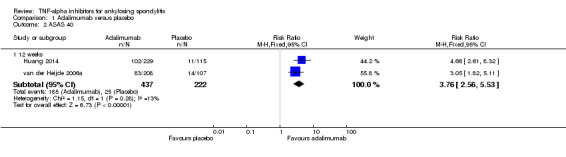

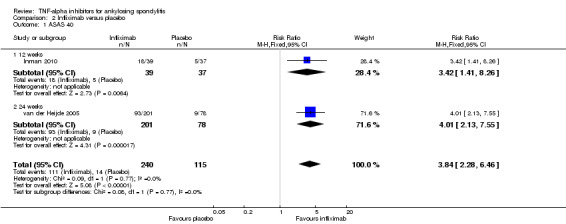

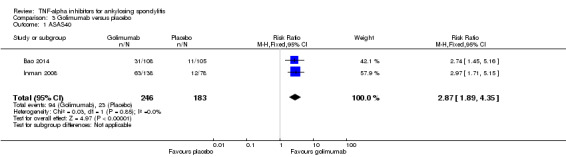

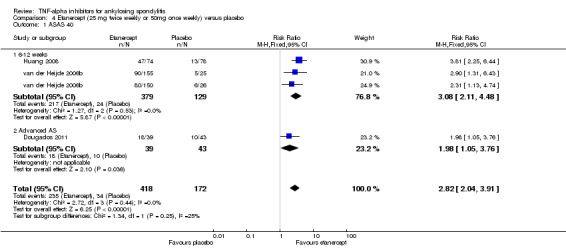

Compared with placebo, there was high quality evidence that patients on an anti‐TNF agent were three to four times more likely to achieve an ASAS40 response (assessing spinal pain, function, and inflammation, as measured by the mean of intensity and duration of morning stiffness, and patient global assessment) by six months (adalimumab: risk ratio (RR) 3.53, 95% credible interval (Crl) 2.49 to 4.91; etanercept: RR 3.31, 95% Crl 2.38 to 4.53; golimumab: RR 2.90, 95% Crl 1.90 to 4.23; infliximab: RR 4.07, 95% Crl 2.80 to 5.74, with a 25% to 40% absolute difference between treatment and placebo groups. The number needed to treat (NNT) to achieve an ASAS 40 response ranged from 3 to 5.

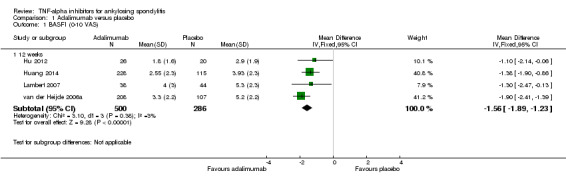

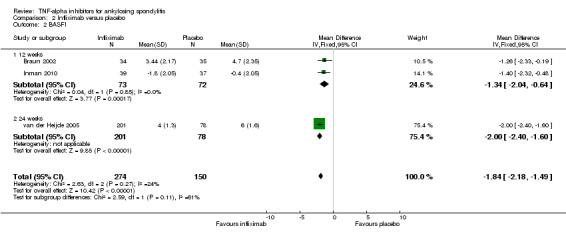

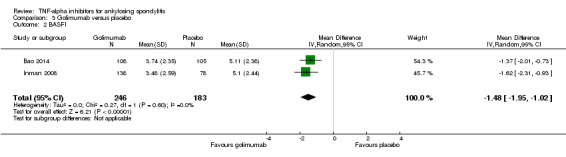

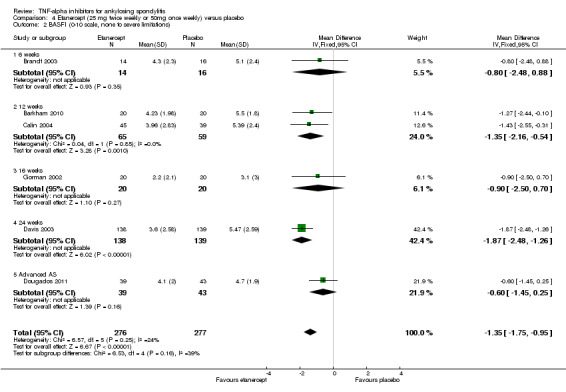

There was high quality evidence of improvement in physical function on a 0 to 10 scale (adalimumab: mean difference (MD) ‐1.6, 95% Crl ‐2.2 to ‐0.9; etanercept: MD ‐1.1, 95% CrI ‐1.6 to ‐0.6; golimumab: MD ‐1.5, 95% Crl ‐2.3 to ‐0.7; infliximab: MD ‐2.1, 95% Crl ‐2.7 to ‐1.4, with an 11% to 21% absolute difference between treatment and placebo groups. The NNT to achieve the minimally clinically important difference of 0.7 points ranged from 2 to 4.

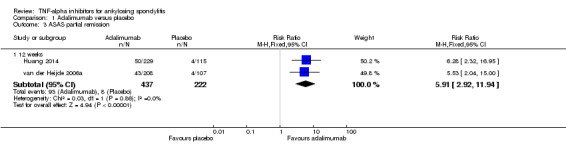

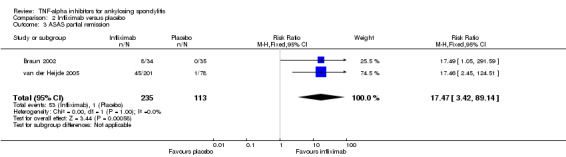

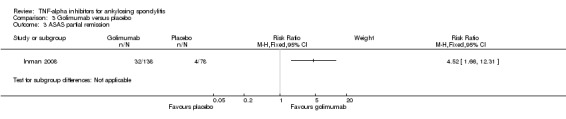

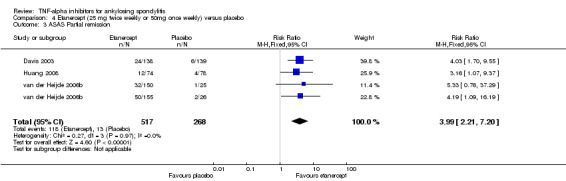

Compared with placebo, there was moderate quality evidence (downgraded for imprecision) that patients on an anti‐TNF agent were more likely to achieve an ASAS partial remission by six months (adalimumab: RR 6.28, 95% Crl 3.13 to 12.78; etanercept: RR 4.24, 95% Crl 2.31 to 8.09; golimumab: RR 5.18, 95% Crl 1.90 to 14.79; infliximab: RR 15.41, 95% Crl 5.09 to 47.98 with a 10% to 44% absolute difference between treatment and placebo groups. The NNT to achieve an ASAS partial remission response ranged from 3 to 11.

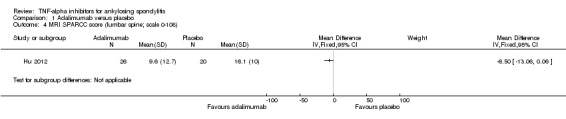

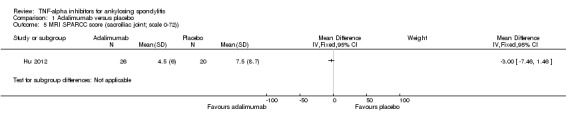

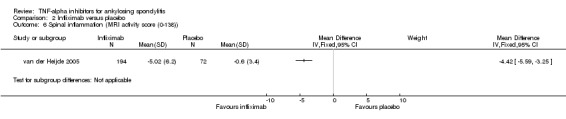

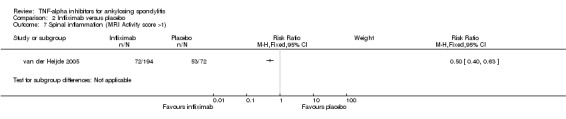

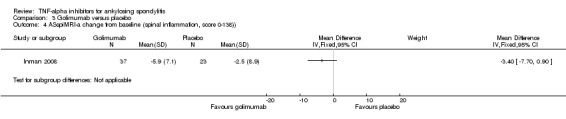

There was low to moderate level evidence of a greater reduction in spinal inflammation as measured by magnetic resonance imaging though the absolute differences were small and the clinical relevance of the difference was unclear: adalimumab (1 trial; ‐6% (95% confidence interval (CI) ‐12% to 0.05%); 1 trial: 53.6% mean decrease from baseline versus 9.4% mean increase in the placebo group), golimumab (1 trial; ‐2.5%, (95% CI ‐5.6% to ‐0.7%)), and infliximab (1 trial; ‐3% (95% CI ‐4% to ‐2.4%)).

Radiographic progression was measured in one trial (N = 60) of etanercept versus placebo and it found that radiologic changes were similar in both groups (detailed data not provided).

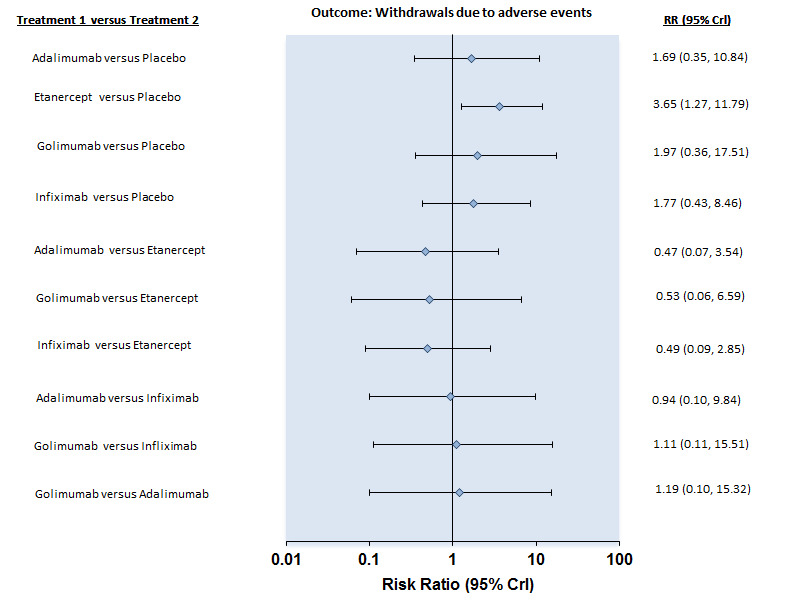

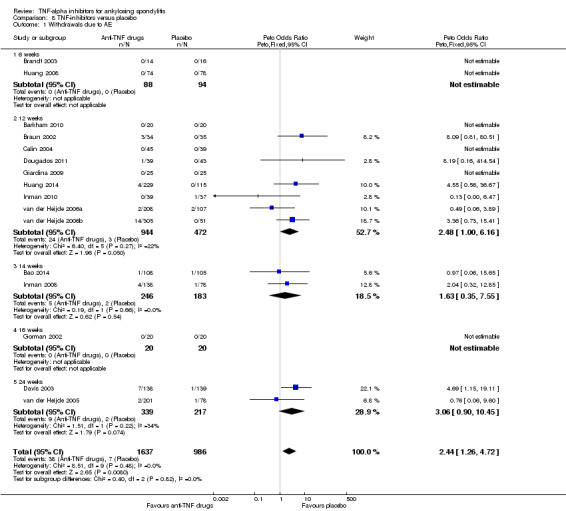

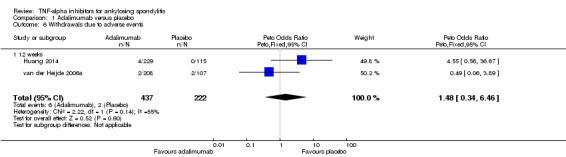

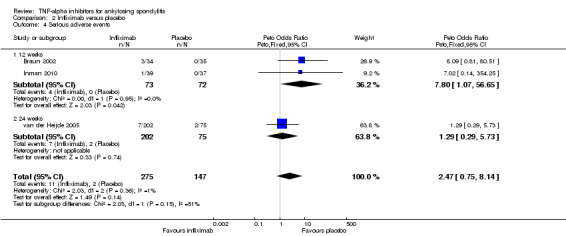

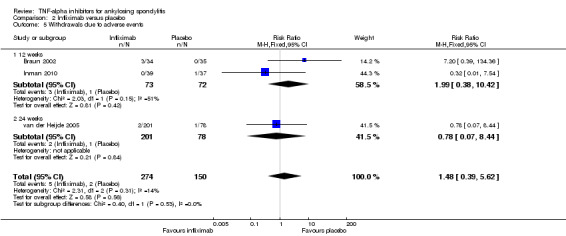

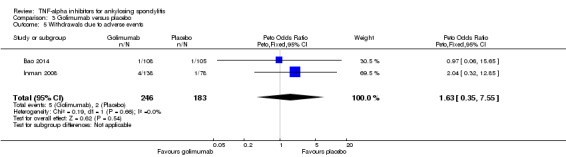

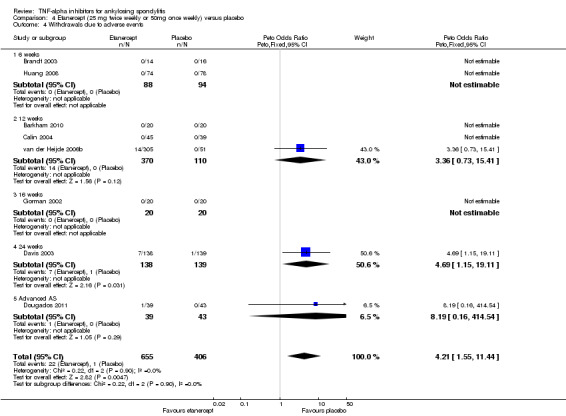

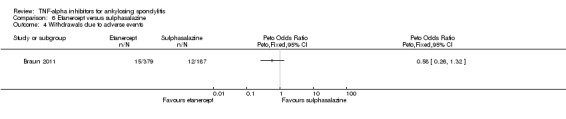

There were few events of withdrawals due to adverse events leading to imprecision around the estimates. When all the anti‐TNF agents were combined against placebo, there was moderate quality evidence from 16 studies of an increased risk of withdrawals due to adverse events in the anti‐TNF group (Peto odds ratio (OR) 2.44, 95% CI 1.26 to 4.72; total events: 38/1637 in biologic group; 7/986 in placebo) though the absolute increase in harm was small (1%; 95% CI 0% to 2%).

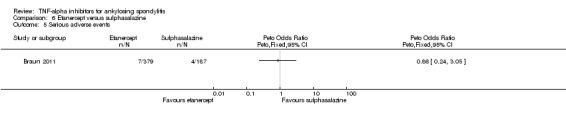

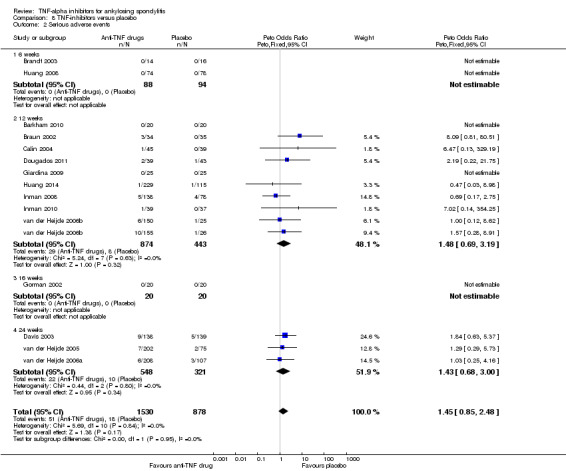

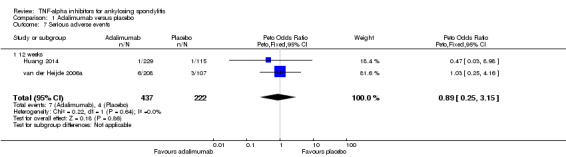

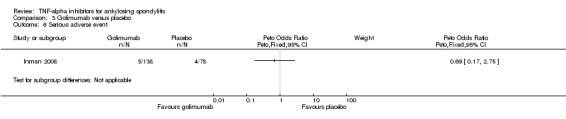

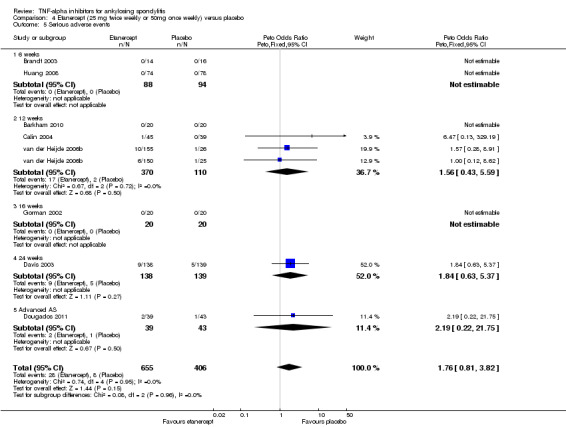

Due to low event rates, evidence of the effect of individual TNF‐inhibitors against placebo or for all four biologics pooled together versus placebo on serious adverse events is inconclusive (moderate quality; downgraded for imprecision). For all anti‐TNF pooled versus placebo based on 16 studies: Peto OR 1.45, 95% CI 0.85 to 2.48; 51/1530 in biologic group; 18/878 in placebo; absolute difference: 1% (95% CI 0% to 2%).

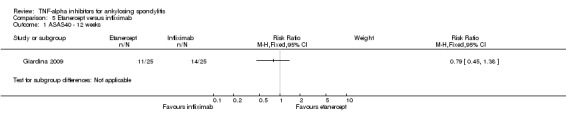

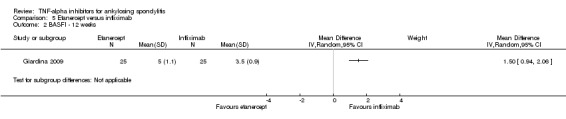

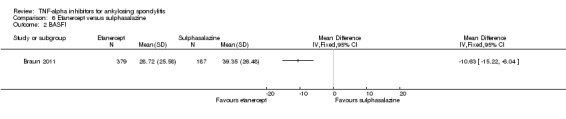

Using indirect comparison methodology, and one head‐to‐head study of etanercept versus infliximab, wide confidence intervals meant that results were inconclusive for evidence of differences in the major outcomes between different anti‐TNF agents. Regulatory agencies have published warnings about rare adverse events of serious infections, including tuberculosis, malignancies and lymphoma.

Authors' conclusions

There is moderate to high quality evidence that anti‐TNF agents improve clinical symptoms in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. More participants withdrew due to adverse events when on an anti‐TNF agent but we did not find evidence of an increase in serious adverse events, though event rates were low and trials had a short duration. The short‐term toxicity profile appears acceptable. Based on indirect comparison methodology, we are uncertain whether there are differences between anti‐TNF agents in terms of the key benefit or harm outcomes.

Keywords: Humans; Adalimumab; Anti‐Inflammatory Agents, Non‐Steroidal; Anti‐Inflammatory Agents, Non‐Steroidal/therapeutic use; Antibodies, Monoclonal; Antibodies, Monoclonal/therapeutic use; Antibodies, Monoclonal, Humanized; Antibodies, Monoclonal, Humanized/therapeutic use; Etanercept; Immunoglobulin G; Immunoglobulin G/therapeutic use; Infliximab; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Receptors, Tumor Necrosis Factor; Receptors, Tumor Necrosis Factor/therapeutic use; Spondylitis, Ankylosing; Spondylitis, Ankylosing/drug therapy; Tumor Necrosis Factor‐alpha; Tumor Necrosis Factor‐alpha/antagonists & inhibitors

Plain language summary

Anti‐TNF‐alpha drugs for treating ankylosing spondylitis

Researchers looked at trials done up to June 2014 on the effect of anti‐TNF drugs (adalimumab (Humira®), etanercept (Enbrel®), golimumab (Simponi®), and infliximab (Remicade®)) on ankylosing spondylitis. They found 21 trials with 3308 participants. Most studies were funded by pharmaceutical companies.

What is ankylosing spondylitis and what are anti‐TNF drugs?

Ankylosing spondylitis is a type of arthritis, usually in the joints and ligaments of the spine, but it may also affect other joints. Pain and stiffness occurs and limits movement in the back and affected joints. It can come and go, last for long periods, and be quite severe.

Anti‐TNF drugs target a protein called 'tumor necrosis factor' that causes inflammation. These drugs suppress the immune system and reduce the inflammation in the joints, with the aim of preventing damage. Even though suppressing the immune system can make it slightly harder to fight off infections, it also helps to stabilize an overactive immune system.

The review shows that in people with ankylosing spondylitis, using anti‐TNF drugs for up to 24 weeks:

‐ improves pain, function and other symptoms of ankylosing spondylitis; ‐ may increase the chance of achieving partial remission of symptoms of ankylosing spondylitis; ‐ probably slightly improves spinal inflammation, as measured by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); and ‐ probably causes slightly more people to drop out of studies because of side effects.

We do not have precise information about side effects and complications, but in these short‐term studies there was no evidence of an increase in serious adverse events. Possible side effects may include a serious infection (like tuberculosis) or upper respiratory infection. Rare complications may include certain types of cancer.

Best estimate of what happens to people with ankylosing spondylitis who take anti‐TNF drugs for up to 24 weeks:

ASAS40 (40% improvement in pain, function, and inflammation as measured by morning stiffness, and patient overall well‐being) Compared to 13 people out of 100 who experienced an improvement with a placebo, among people who took:

‐ adalimumab: 46 people out of 100 experienced improvement (33% improvement); ‐ etanercept: 43 people out of 100 experienced improvement (30% improvement); ‐ golimumab: 38 people out of 100 experienced improvement (25% improvement); and ‐ infliximab: 53 people out of 100 experienced improvement (40% improvement).

Partial remission (defined as a value of less than 2 on a 0 to 10 scale in each of pain, function, and inflammation as measured by morning stiffness, and patient overall well‐being) Compared to 3 people out of 100 who experienced an improvement with a placebo, among people who took:

‐ adalimumab: 19 people out of 100 experienced partial remission (16% improvement); ‐ etanercept: 13 people out of 100 experienced partial remission (10% improvement); ‐ golimumab: 16 people out of 100 experienced partial remission (13% improvement); and ‐ infliximab: 47 people out of 100 experienced partial remission (44% improvement).

Physical function (lower score means better function; 0 to 10 scale)

Compared to a score of 5 in people who took placebo, among people who took:

‐ adalimumab, they rated their function to be 3.4 (16% improvement); ‐ etanercept, they rated their function to be 3.9 (11% improvement); ‐ golimumab, they rated their function to be 3.5 (15% improvement); and ‐ infliximab, they rated their function to be 2.9 (21% improvement).

Spinal inflammation as measured by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) Compared to people who took placebo, a small improvement in spinal inflammation was seen in:

‐ adalimumab (6% improvement); ‐ golimumab (2.5% improvement); and ‐ infliximab (3% improvement).

X‐rays of the joints

Only one study looked at x‐rays and found that joint changes were similar in both groups (detailed data not provided).

Side effects

When all the anti‐TNF drugs were combined, 16 people out of 1000 dropped out of the study because of side effects compared to 7 people out of 1000 who took placebo (absolute increase 1%).

There may be little or no difference in the number of people who have a serious side effect with an anti‐TNF drug compared to people who take a fake pill.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Summary of findings table.

| TNF‐alpha inhibitors for ankylosing spondylitis (short‐term results < 24 weeks) | |||||||

| Outcome |

Intervention and comparison |

Illustrative comparative risks |

Relative effect (95% CrI) |

Number of participants (studies) |

Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

Comment | |

|

Assumed risk with comparator1 |

Corresponding risk with intervention (95% CI or Crl) |

||||||

| Placebo | TNF‐alpha inhibitor | ||||||

| ASAS40 | |||||||

| Adalimumab versus placebo | 13 per 100 | 46 per 100 (32 to 64) | RR 3.53 (2.49 to 4.91) | 659 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | Absolute increased benefit % = 33% (95% Crl 19% to 51%) Relative % change= 253% (95% CI 149% to 391%) NNT = 4 (95% CI 2 to 6) |

|

| Etanercept (25 mg twice weekly or 50 mg once weekly) versus placebo | 13 per 100 | 43 per 100 (31 to 59) | RR 3.31 (2.38 to 4.53) | 584 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | Absolute increased benefit % = 30% (95% Crl 18% to 46%) Relative % change = 231% (95% CI 138% to 353%) NNT = 4 (95% Cl 3 to 6) |

|

| Golimumab versus placebo | 13 per 100 | 38 per 100 (25 to 55) | RR 2.90 (1.90 to 4.23) | 429 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | Absolute increased benefit % = 25% (95% Crl 12% to 42%) Relative % change = 190% (95% CI 90% to 323%) NNT = 5 (95% CI 3 to 9) |

|

| Infliximab versus placebo | 13 per 100 | 53 per 100 (36 to 75) | RR 4.07 (2.80 to 5.74) | 355 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | Absolute increased benefit % = 40% (95% Crl 23% to 62%) Relative % change = 307% (95% CI 180% to 474%) NNT= 3 (95% CI 2 to 5) |

|

| BASFI (0 to 10 scale) | |||||||

| Adalimumab versus placebo | The mean BASFI in the control groups was 5 points | The mean BASFI in the intervention groups was 1.6 lower (2.2 to 0.9 lower) | 786 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | Absolute increased benefit % = ‐16% (95% Crl ‐22% to ‐9%); Relative % change from baseline = ‐32% (‐44% to ‐18%); NNT to achieve the MCID of 0.7 points = 4 (95% CI 3 to 5) | ||

| Etanercept (25 mg twice weekly or 50 mg once weekly) versus placebo | The mean BASFI in the control groups was 5 points | The mean BASFI in the intervention groups was 1.1 lower (1.6 to 0.6 lower) | 553 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | Absolute increased benefit % =‐11% (95% Crl ‐16% to ‐6%); Relative % change from baseline = ‐22% (‐32% to ‐12%); NNT to achieve the MCID of 0.7 points = 4 (4 to 6) |

||

| Golimumab versus placebo | The mean BASFI in the control groups was 5 points | The mean BASFI in the intervention groups was 1.5 lower (2.3 to 0.7 lower) | 429 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | Absolute increased benefit % =‐15% (95% Crl ‐23% to ‐7%) Relative % change from baseline = ‐30% (‐46% to ‐14%) NNT to achieve the MCID of 0.7 points = 4 (3 to 5) |

||

| Infliximab versus placebo | The mean BASFI in the control groups was 5 points | The mean BASFI in the intervention groups was 2.1 lower (2.7 to 1.4 lower) | 348 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | Absolute increased benefit % = ‐21% (95% Crl ‐27% to ‐14%) Relative % change from baseline = ‐42% (‐54% to ‐28%) NNT to achieve the MCID of 0.7 points = 2 (2 to 3) |

||

| ASAS partial remission | |||||||

| Adalimumab versus placebo | 3 per 100 | 19 per 100 (9 to 38) | RR 6.28 (3.13 to 12.78) | 659 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ moderate2 | Absolute increased benefit % = 16% (95% Crl 6% to 35%) Relative % change = 528% (95% CI 213% to 1178%) NNT = 7 (95% CI 3 to 16) |

|

| Etanercept (25 mg twice weekly or 50 mg once weekly) versus placebo | 3 per 100 | 13 per 100 (7 to 24) | RR 4.24 (2.31 to 8.09) | 785 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ moderate2 | Absolute increased benefit % = 10% (95% Crl 4% to 21%) Relative % change = 324% (95% CI 131% to 709%); NNT = 11 (95% CI 5 to 26) | |

| Golimumab versus placebo | 3 per 100 | 16 per 100 (6 to 44) | RR 5.18 (1.90 to 14.79) | 216 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ moderate2 | Absolute increased benefit % = 13% (95% Crl 3% to 41%) Relative % change = 418% (95% CI 90% to 1379%); NNT = 8 (95% CI 3 to 38) | |

| Infliximab versus placebo | 3 per 100 | 47 per 100 (16 to 90) | RR 15.41 (5.09 to 47.98) | 348 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ moderate2 | Absolute increased benefit % = 44% (95% Crl 13% to 87%) Relative % change = 1441% (95% CI 409% to 4698%) NNT = 3 (95% CI 2 to 8) |

|

| MRI of spinal inflammation | |||||||

| Adalimumab versus placebo Lumbar spine MRI; SPARCC score (0 to 108) |

The mean SPARCC score in the control groups was 16.1 | The mean SPARCC score in the intervention groups was 6.5 lower (13.06 to 0.06 higher) | 46 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ moderate3 | Absolute increased benefit % = ‐6% (95% CI ‐12% to 0.05%) Relative % change = ‐33% (95% CI ‐66% to 0%) NNT = n/a 2nd study with MRI data: Lambert 2007 (N = 82): % change from baseline in SPARCC score, week 12 (no variance provided) 1. Spine: Adalimumab group = 53.6% mean decrease Placebo group = 9.4% mean increase Between group: P < 0.001 2. Sacroiliac joint, % mean decrease: Adalimumab group = 52.9%, Placebo group = 12.7% Between group: P = 0.017 |

||

| Etanercept (25 mg twice weekly or 50 mg once weekly) versus placebo | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 0 (0) | See comment | No studies assessed this outcome | |

| Golimumab versus placebo Change from baseline in AS spine MRI activity score (0 to 138; lower means less erosions or edema) |

The mean change in the control group was ‐2.5 points | The mean change in the golimumab group was

3.4 points lower (7.7 to 0.90 points lower) |

60 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖ low3,4 | Absolute increased benefit % = ‐2.5% (95% CI ‐5.6% to ‐0.7%) Relative % change = ‐35% (95% CI ‐80% to 9%) NNT = n/a |

||

| Infliximab versus placebo Change from baseline in AS spine MRI activity score (0 to 138; lower means less erosions or edema) |

The mean change in the control group was ‐0.6 points | The mean change in the infliximab group was

4.4 points lower (5.6 to 3.3 points lower) |

266 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ moderate5 | Absolute increased benefit % = ‐3% (95% CI ‐4% to ‐2.4%) Relative % change = ‐62% (95% CI ‐79% to ‐46%) NNT = 3 (95% CI 3 to 5) Inman 2010 assessed MRI in a substudy (N = 26): "when the evaluation was based on the entire spine (23 DVU score), the infliximab group had a mean reduction of 57.2% compared to 3.4% in the placebo group (P < 0.001)" |

||

| Radiographic progression | |||||||

| Adalimumab versus placebo | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 0 (0) | See comment | No studies assessed this outcome | |

| Etanercept (25 mg twice weekly or 50 mg once weekly) versus placebo | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 0 (0) | See comment | No studies measured this outcome | |

| Golimumab versus placebo | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 0 (0) | See comment | No studies measured this outcome | |

| Infliximab versus placebo | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 0 (0) | See comment | Braun 2002 (N = 60) used the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Radiology Index (BASRI) to measure radiographic progression but detailed data was not provided. The results stated the "initial degree of radiological axial changes assessed by the BASRIs was similar in both groups" | |

| Withdrawals due to adverse events | |||||||

| Adalimumab versus placebo | 7 per 1000 | 12 per 1000 (3 to 80) | RR 1.69 (0.35 to 10.84) | 659 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ moderate2 | Absolute increased harm % = 0.6% (95% Crl ‐0.4% to 7%) Relative % change = 69% (95% CI ‐65% to 984%) NNT = n/a |

|

| Etanercept (25 mg twice weekly or 50 mg once weekly) versus placebo | 7 per 1000 | 26 per 1000 (9 to 83) | RR 3.65 (1.27 to 11.79) | 1061 (8 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ moderate2 | Absolute increased harm % = 2% (95% Crl 0.2% to 8%) Relative % change = 265% (95% CI 27% to 1079%) NNTH = 54 (95% CI 14 to 530) |

|

| Golimumab versus placebo | 7 per 1000 | 14 per 1000 (3 to 123) | RR 1.97 (0.36 to 17.51) | 429 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ moderate2 | Absolute increased harm % = 1.6% (95% Crl ‐0.4% to 11.6%) Relative % change = 97% (95% CI ‐64% to 1651%) NNTH = n/a |

|

| Infliximab versus placebo | 7 per 1000 | 12 per 1000 (3 to 59) | RR 1.77 (0.43 to 8.46) | 424 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ moderate2 | Absolute increased harm % = 0.5% (95% Crl ‐0.4% to 5.6%) Relative % change = 77% (95% CI ‐43% to 746%) NNT = n/a |

|

| All anti‐TNF agents versus placebo | 7 per 1000 | 16 per 1000 (8 to 33) | Peto OR 2.44 (1.26 to 4.72 | 2623 (16 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ moderate2 | Absolute increased harm % = 1% (95% CI 0% to 2%) Relative % change = 130% (95% CI 12% to 371%) NNTH = 101 (95% CI 555 to 40) |

|

| Serious adverse events | |||||||

| Adalimumab versus placebo | 15 per 1000 | 14 per 1000 (4 to 59) | RR 0.92 (0.26 to 3.93) | 659 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ moderate2 | Absolute increased harm %= ‐0.2% (95% Crl ‐1.1% to 4.4%); Relative % change= ‐8% (95% CI ‐74% to 293%); NNT = n/a | |

| Etanercept (25 mg twice weekly or 50 mg once weekly) versus placebo | 15 per 1000 | 25 per 1000 (11 to 56) | RR 1.69 (0.76 to 3.72) | 1061 (8 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ moderate2 | Absolute increased harm % = 1% (95% Crl ‐0.4% to 4.1%) Relative % change = 67% (95% CI ‐27% to 282%) NNT = n/a |

|

| Golimumab versus placebo | 15 per 1000 | 10 per 1000 (2 to 50) | RR 0.69 (0.15 to 3.32) | 216 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ moderate2 | Absolute increased harm % = ‐0.5% (95% Crl ‐1.3% to 3.5%); Relative % change= ‐31% (95% CI ‐85% to 232%); NNT = n/a | |

| Infliximab versus placebo | 15 per 1000 | 38 per 1000 (11 to 166) | RR 2.53 (0.76 to 11.09) | 422 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ moderate2 | Absolute increased harm % = 2.3% (95% Crl ‐0.4% to 15.1%) Relative % change = 153% (95% CI ‐24% to 1009%) NNT = n/a |

|

| All anti‐TNF agents versus placebo | 15 per 1000 | 22 per 1000 (13 to 36) | Peto OR 1.45 (0.85 to 2.48) | 2408 (15 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ moderate2 | Absolute increased harm % = 1% (95% CI 0% to 2%) Relative % change = 41% (95% CI ‐15% to 136%) NNTH = n/a |

|

95% CI = 95% confidence interval; 95% Crl = 95% credible interval; n/a = not applicable; NNTH = Number needed to treat for harm; RR = risk ratio; OR = odds ratio; SI = sacroiliac joint; SPARCC = Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada

NNT = not applicable for non‐statistically significant results

Note: Results for ASAS40, BASFI, ASAS partial remission, withdrawals due to adverse events, and serious adverse events are based on the mixed treatment comparison analyses. The 'All anti‐TNF agents versus placebo' results for withdrawals due to adverse events and serious adverse events are based on standard meta‐analyses in Review Manager 5.3.

1 Assumed risk based on the placebo event rate as calculated in the mixed treatment comparison analysis.

2 Downgraded for imprecision; fewer events than 300 (a threshold rule‐of‐thumb) and wide confidence interval.

3 Downgraded for imprecision: total population is < 400.

4 MRI substudy (N = 60 for placebo and 50 mg golimumab arms) conducted at 10/57 participating sites; N = 216 in full RCT; readers were blinded but concerns regarding only modest level of agreement. Downgraded for concerns regarding missing data (12% did not have baseline and follow‐up MRIs and imputed 7% of scores at week 14).

5 Downgraded for imprecision; total population is < 400. MRI data available for 194/201 in infliximab group; 72/78 in placebo group.

Background

Description of the condition

Ankylosing spondylitis is a chronic, inflammatory rheumatic disease characterized by inflammatory back pain due to sacroiliitis and spondylitis, enthesitis, and the formation of syndesmophytes (bony growths) leading to ankylosis. Extraspinal manifestations are common, including peripheral arthritis (25% to 50%), uveitis (eye inflammation) (25% to 40%), and inflammatory bowel disease (26%), and contribute to disease morbidity (Edmunds 1991; Inman 2011).

The etiology of the disease is not yet fully understood but there is a strong association with the HLA‐B27 gene (Inman 2011). Studies have shown the prevalence of ankylosing spondylitis in the adult general population to vary from 0.4% (Alaskan Inuit) to 1.4% (Northern Norway) (Khan 2002). A general rule is that the prevalence of ankylosing spondylitis is highest in HLA‐B27‐positive patients with a family member who also has the disease (20%), is least in the general population (0.2%), and is about 2% in those positive for HLA‐B27 (Inman 2011). The peak age of onset is in young adults between 20 and 30 years, although there is often a five to six year delay in diagnosis (Khan 2002).

Clinical symptoms usually begin with back pain and stiffness in adolescence and early adulthood which shows improvement with exercise and can lead to impaired spinal mobility, or chest expansion, or both. The disease course of ankylosing spondylitis is highly variable, with back pain and stiffness often the primary features early in the process, and chronic pain and joint changes later on (Inman 2011). The burden of disease in ankylosing spondylitis has been found to be similar to that of rheumatoid arthritis in terms of pain, disability and decreased well‐being (Zink 2000). Additionally, compared to the general population, those with ankylosing spondylitis experience higher work disability and absence from work, which can lead to substantial direct and indirect socioeconomic costs (Boonen 2001a; Boonen 2001b; Montacer 2009).

The goals of treatment of ankylosing spondylitis are to relieve symptoms (pain, stiffness, joint swelling), improve physical function, and delay or avoid structural damage which leads to physical impairments and deformities. Ankylosing spondylitis requires a multidisciplinary treatment approach and is usually managed with a combination of exercises, physiotherapy and drug therapy. Regular exercise is crucial for maintaining or improving spinal mobility and physical function (Dagfinrud 2008). Non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the mainstay of symptomatic drug therapy, reducing the pain and stiffness of inflammation. Although these interventions can alleviate the symptoms of the disease, it is not clear whether they are able to prevent or delay the structural damage leading to physical disability. Some evidence suggests continuous NSAID therapy may have an effect on the spinal radiographic changes seen in ankylosing spondylitis (Wanders 2005). At least one‐third of patients respond insufficiently to NSAID therapy or experience serious side effects from NSAIDs and thus require disease controlling drugs in addition to symptom‐modifying treatment. In contrast to rheumatoid arthritis, there are no established disease‐modifying anti‐rheumatic treatments in ankylosing spondylitis, although sulphasalazine may be effective for peripheral joint symptoms but not for axial disease (Dougados 2002; Chen 2014).

Description of the intervention

A major advance in treatment options for ankylosing spondylitis is the development of biologic therapies which target specific elements of the immune system. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)‐alpha is a protein that the body produces during the inflammatory response. TNF‐alpha promotes inflammation and subsequent pain, tenderness, swelling and fever in several inflammatory conditions, including ankylosing spondylitis. Four anti‐TNF agents, also known as TNF‐inhibitors, have been developed to target the binding of this protein, thus reducing the pain, swelling, and inflammation associated with ankylosing spondylitis. The generic and trademark drug names are: adalimumab (Humira®), etanercept (Enbrel®), golimumab (Simponi®), and infliximab (Remicade®). Infliximab is given as an intravenous infusion over one to two hours while etanercept, adalimumab, and golimumab are given as subcutaneous injections. Etanercept and adalimumab are given as weekly or bi‐weekly injections, while golimumab is injected once a month. Recognized contraindications for treatment include tuberculosis, multiple sclerosis, lupus, malignancy, pregnant or lactating women, heart failure, hepatitis, and pneumonia.

How the intervention might work

As the result of research demonstrating that tumor necrosis factor‐alpha (TNF‐alpha) is present in inflamed sacroiliac joints (Braun 1995), treatments were developed to block TNF‐alpha. Etanercept is a receptor fusion protein that binds to TNF‐alpha, thus competitively inhibiting the binding of TNF‐alpha to the cell surface. Infliximab is a chimeric (mouse/human) monoclonal antibody of the IgG1κ isotype that binds with a high affinity to TNF‐alpha. Adalimumab is a recombinant human IgG1 monoclonal antibody specific for human TNF‐alpha, and golimumab is a human monoclonal antibody that binds to both soluble and transmembrane TNF‐alpha. These four agents prevent TNF‐alpha from promoting inflammation and therefore are thought to interrupt the processes responsible for the pain, tenderness, and swelling of joints in patients with ankylosing spondylitis.

Why it is important to do this review

Early open label studies demonstrated that biologics are efficacious in ankylosing spondylitis (Brandt 2000; Haibel 2004; Maksymowych 2002; Marzo‐Ortega 2001; Stone 2001) and RCTs showed them to be effective in improving disease activity, spinal mobility, function, and pain (Braun 2002; Gorman 2002; Van Den Bosch 2002). Recognized adverse effects of anti‐TNF‐alpha therapy include serious infections such as tuberculosis, allergic reactions and autoimmune reactions.

The relatively high cost of treatment and possible serious side effects of anti‐TNF‐alpha therapy led the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) (Braun 2003; van der Heijde 2011) and the Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada (Maksymowych 2003) to develop recommendations for the use of TNF‐alpha inhibitors in ankylosing spondylitis.

While these biologics offer an important therapeutic advance by appearing to reduce disease activity and improve function and well‐being of patients, it is important to understand and try to quantify not only the potential benefits of this treatment, but also the potential harms. Clinicians and patients need this information in order to make an informed decision about the trade‐offs of using this treatment option. The evidence base for the individual biologics compared to each other is of interest to patients and other healthcare decision makers. We will include certolizumab in an update of this review. Head‐to‐head studies (i.e. one biologic versus another) are usually rare so we will undertake indirect comparisons using network meta‐analysis methodology to address this question.

Objectives

To assess the benefits and harms of adalimumab, etanercept, golimumab, and infliximab (TNF‐alpha inhibitors) in people with ankylosing spondylitis.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and controlled clinical trials (CCTs). We defined 'short‐term' benefit and harms as those with equal to or less than six months duration and 'long‐term' benefit and harms as longer than six months.

Types of participants

We included studies of patients meeting the following ankylosing spondylitis classification criteria: 1961 Rome, 1966 New York, or modified 1984 New York. We did not apply any additional restrictions in studies with regard to age of patients, past or present (co‐)medication or ankylosing spondylitis‐related comorbidity. We included studies on spondyloarthropathies that mentioned ankylosing spondylitis patients as a subgroup, as far as the subgroup was properly randomized and outcome measures were available, specifically for the ankylosing spondylitis subgroup. We included patients on other medications, and with or without ankylosing spondylitis‐related comorbidity (e.g. peripheral joint impairment, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis). We did not impose restrictions on age or disease duration. We did not include diagnoses of axial spondyloarthritis, though we may consider this for an update of this review based on the classification criteria developed by ASAS (Rudwaleit 2009a; Rudwaleit 2009b).

Types of interventions

Adalimumab versus placebo, other medications, or usual care.

Etanercept versus placebo, other medications, or usual care.

Golimumab versus placebo, other medications, or usual care.

Infliximab versus placebo, other medications, or usual care.

Note that we added golimumab after the protocol for this review (Zochling 2005).

We did not impose any restrictions with regard to dose or concomitant treatments in the placebo group (for example, physical exercises, or NSAIDs, or both).

Types of outcome measures

The primary and secondary outcomes defined in the protocol and listed in the Differences between protocol and review section were chosen in 2005 when the protocol for this review was published (Zochling 2005). Since then, the Cochrane Collaboration has developed Summary of Findings tables which require choosing a maximum of seven major outcomes for presentation in the table. The Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (formerly ASsessment in Ankylosing Spondylitis) (ASAS) Working Group) (http://www.asas‐group.org) has developed core sets of standardized outcome measures for use in clinical practice and trial settings. This work has been undertaken in conjunction with the OMERACT (Outcome Measures in Rheumatology, www.omeract.org) initiative which aims to establish standardized, validated outcome measures for use in clinical trials in the field of rheumatology. Following discussion with experts from ASAS, the following outcomes were chosen to be the major outcomes for this review:

ASAS40 (Brandt 2004)

BASFI (Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index) (Calin 1994)

ASAS partial remission (Anderson 2001)

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for evidence of inflammation

Radiographic progression

Withdrawals due to adverse events

Serious adverse events

The criteria for an ASAS40 response is: at least a 40% improvement with a minimum of 20 units (0 to 100 scale) improvement compared with baseline in at least three of four domains (spinal pain, function (BASFI), inflammation as measured by the mean of intensity and duration of morning stiffness in the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI), and patient global assessment), and with no worsening in the fourth domain. Partial remission is defined as a value of less than 2 on a 0 to 10 scale in each of the four domains as described above for the ASAS40.

Search methods for identification of studies

The Cochrane Musculoskeletal Group's Trial Search Co‐ordinators developed the search strategies. In the original search in January 2009, we searched the following electronic databases: Cochrane Library (2008, Issue 4) including the following databases: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), Cochrane Library Health Technology Assessment Database (CLHTA), and NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED); MEDLINE (1966 to January 26, 2009); EMBASE (1980 to January 26, 2009); CINAHL (1982 to January 26, 2009); ISI Web of Knowledge (1900 to January 2009).

We reviewed the reference section of retrieved articles. We contacted authors of relevant papers and experts in the field regarding any further published or unpublished work. One review author (LM) handsearched conference proceedings from the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR, http://www.abstracts2view.com/eular/ textword search: ankylosing AND etanercept OR infliximab OR adalimumab) from 2005 to 2009, for both benefit and harms.

We conducted an updated search in May 2012. In October 2013, we conducted another updated search of all databases and also included a search for 'golimumab' from database inception. From September 2013 to June 2014 we received alerts of potential new studies identified by the McMaster PLUS database (McMaster PLUS evidence updates) through a service provided for Cochrane Musculoskeletal Group authors.

In October 2014 a search of clinicaltrials.gov was conducted for any completed trials meeting the review's inclusion criteria using 'ankylosing spondylitis' in condition and Phase 3 and 4 trials.

For safety assessments, we searched the websites of the regulatory agencies (US Food and Drug Administration‐MedWatch (http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/default.htm), European Medicines Evaluation Agency (http://www.emea.europa.eu), Australian Adverse Drug Reactions Bulletin (http://www.tga.gov.au/adr/aadrb.htm), and UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) pharmacovigilance and drug safety updates (http://www.mhra.gov.uk); note 'Current Problems in Pharmacovigilance' was superseded by 'Drug Safety Update' in July 2007) using the terms “ankylosing spondylitis,” “adalimumab,” "humira", "etanercept", "enbrel", "infliximab", and "remicade” on April 1, 2010. We updated this search and included "golimumab"/"simponi" in November 2014.

We did not impose any language restrictions.

There were some abstracts from conference proceedings that were later published as full‐text articles; in this case, we only included the full‐text article, however, if the abstract provided additional important information that was not provided in the full‐text article, then we also included the data from the abstract. Some trials had more than one publication with the secondary publications reporting on other outcomes such as health‐related quality of life, patient‐reported outcomes, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data.

The original MEDLINE search strategy is in Appendix 1. The other search strategies are available in Appendix 2 and Appendix 3.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two people independently reviewed the results of the search strategy. The authors involved in screening the different search results were: JZ, JS, LM, MBJ, MV. We reviewed abstracts and if more information was required to determine whether the trial met the inclusion criteria, we obtained the full text. Disagreement was resolved by a third author (AB, GW).

Data extraction and management

Four review authors (JZ, LM, JS, MVS) independently extracted data from the included trials and entered the data into Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2014). We pilot‐tested data extraction forms on a selection of trials.

We extracted the following data.

General study information such as title, authors, contact address, publication source, publication year, country, study sponsor.

Characteristics of the study: design, study setting, inclusion/exclusion criteria, risk of bias criteria (e.g. randomisation method, allocation procedure, blinding of patients, caregivers and outcome assessors).

Characteris`tics of the study population and baseline characteristics of the intervention and control groups (age, sex, type of classification criteria, duration of disease, presence of comorbidity and peripheral disease, concomitant treatments, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI), Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI), patient global assessment) and numbers in each group.

Characteristics of the intervention, such as treatment comparators, dose, method of administration, frequency of administration and duration of treatment.

Outcomes measures as noted above.

Results for the intention‐to‐treat population (where possible), summary measures with standard deviations, confidence intervals and P values where given, dropout rate and reasons for withdrawal.

When data for more than one time point was provided, we used the longest time point for the blinded phase and prior to any early‐escape option for the meta‐analysis. However, for some of the harms data, only results for the double‐blind period was reported, without providing data prior to the early‐escape option. In this case, we used the double‐blind period data with data for those that did not crossover.

We extracted both change and final values, as reported in the publication. The network meta‐analysis required only end of study values so we calculated those when only a change value had been provided and used the standard deviation at baseline for the end of study standard deviation.

We used Plot Digitizer software to estimate results from five graphs (Plot Digitizer 2014) .

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two independent reviewers (LM, JZ, MV, CM, MB) assessed risk of bias in the included RCTs. As recommended by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), we assessed the following methodological domains.

Random sequence generation ‐ was the method used to generate the allocation sequence appropriate to produce comparable groups?

Allocation sequence concealment ‐ was the method used to conceal the allocation sequence appropriate to prevent the allocation being known in advance of, or during, enrolment?

Blinding of participants, personnel ‐ were measures used to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received? We assessed patient‐ and physician‐assessed outcomes separately.

Blinding of outcome assessors ‐ were measures used to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received? We assessed patient‐ and physician‐assessed outcomes separately.

Incomplete outcome data ‐ how complete was the outcome data for the primary outcomes? Were dropout rates and reasons for withdrawal reported? Was missing data imputed appropriately? We considered an overall completion rate of 80% or higher as a low risk of bias. If completion rates were only provided by group, a less than 80% completion rate in the treatment group was considered a high risk of bias.

Selective outcome reporting ‐ were appropriate outcomes reported and were any key outcomes missing?

Ascertainment of outcome ‐ did the researchers actively monitor for adverse events (low risk of bias) or did they simply provide spontaneous reporting of adverse events that arise (high risk of bias)?

Definition of adverse outcomes‐ were definitions provided for general 'adverse event' or 'serious adverse event'?

We explicitly judged each of these criteria using: low risk of bias; high risk of bias; or unclear, meaning either lack of information or uncertainty over the potential for bias. We provided a reason for each judgement in the 'Risk of bias' table.

Measures of treatment effect

Methods for indirect and mixed treatment comparisons

For dichotomous outcome, we derived point estimates and 95% credible intervals for odds ratios (ORs), risk ratios (RR) and risk differences (RD). For continuous outcomes, we derived mean differences (MD) and 95% credible intervals.

Methods for direct treatment comparisons

In addition to the mixed treatment comparisons, we pooled data for serious adverse events and withdrawals due to adverse events to investigate a class‐effect of harms of biologics. We analysed this using Peto odds ratio (Peto OR) with 95% CIs given that the Peto OR is recommended when the outcome is a rare event (approximately less than 10%).

Unit of analysis issues

For studies with more than two arms, we halved the number of events and patients in the placebo arm to avoid double‐counting the placebo participants in the meta‐analysis. We only assessed the standard doses for each of the biologics for inclusion in the network meta‐analysis when multiple trial arms with different dosages were reported.

Dealing with missing data

We performed the following calculations for the purpose of entering data into Review Manager 5 when the mean and standard deviation was not provided in the published article. When the median change from baseline and interquartile range (IQR) change from baseline were reported (as in Inman 2008 and van der Heijde 2005), we assumed the median change to be the mean change and calculated the standard deviation as the IQR at baseline divided by 1.35 and this standard deviation (SD) assumed for the end of study score, as per the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Where no SD at end of study was reported or the variance for the change from baseline was provided in the study report as the standard error of the change, the baseline SD was assumed for the end of study SD (Braun 2011; van der Heijde 2006a).

In Davis 2003, the standard error of the mean (SEM) was transformed to SD by the calculation SD = SEM *sqrt(N). In Barkham 2010 the 95% CI about the mean change was converted to SD using the formula in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). In Inman 2010, the SD was calculated from the P value for continuous outcomes. In Gorman 2002, the median was assumed for the mean for continuous beneficial outcomes.

We conducted sensitivity analyses to check the robustness of the estimates to these imputations.

For continuous outcomes, we calculated the mean difference (MD) based on the number of patients analysed at that time point. When the number of patients analysed was not presented for each time point, we used the number of randomized patients in each group at baseline.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Both network meta‐analysis and traditional meta‐analysis require studies to be sufficiently similar in order to pool their results. As a result, we carefully assessed heterogeneity across trials in terms of patient characteristics, trial methodologies, and treatment protocols across trials.

As outlined in the papers by Bucher 1997 and Song 2009, there are several key assumptions that must be met when undertaking indirect comparisons. Song breaks these assumptions into three components: i.homogeneity; ii. similarity of trial; iii. consistency of evidence. Homogeneity refers to the standard assumptions used for pooling studies in a meta‐analysis; ie. trials comparing two treatments must be both clinically and methodologically similar to be combined. Trial similarity is comprised of clinical similarity and methodological similarity and the similarity of the bridging treatment. By 'bridging treatment' we mean the common comparator (ie. in a trial of A versus C and B versus C, the bridging treatment is 'C'). The assumption of consistency means that the results of direct and indirect evidence should not be heterogeneous and that there is a consistent effect across the direct comparisons.

To ensure that the consistency assumption is valid, we formally assessed inconsistency by comparing the deviance and deviance information criterion statistics of the consistency and inconsistency models (Dias 2010; Dias 2011c). To help identify the loops in which inconsistency was present, we plotted the posterior mean deviance of the individual data points in the inconsistency model against their posterior mean deviance in the consistency model (Dias 2010). Using the plots, loops in which inconsistency is present could be identified.

In the standard Review Manager 5 meta‐analyses, we tested heterogeneity of the data by visual inspection of the forest plots and by using the I2 statistic (Higgins 2003). A value greater than 50% may be considered substantial heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We visually inspected funnel plots to assess publication bias when there were more than 10 included studies for an outcome; however, this applied to only two outcomes: the pooled results for all anti‐TNF agents versus placebo for withdrawals due to adverse events and serious adverse events.

Data synthesis

We combined data in a meta‐analyses only when we decided it was meaningful to do so, i.e. when the treatments, participants and the underlying clinical question were similar enough for pooling to make sense. We planned to analyze and present separately 'short‐term' outcomes ( less than or equal to 6 months duration) and 'long‐term' outcomes ( greater than 6 months). However, all included studies were short‐term.

We made a post‐hoc decision to present the results combined for etanercept trials which used either 25 mg administered twice a week or 50 mg administered once a week. The results from the van der Heijde 2006b study showed these dosing regimens to be equivalent in both benefit and safety. We also pooled infliximab doses of 3 mg/kg and 5 mg/kg together as there was very little heterogeneity when the major outcomes for these two doses were pooled together in a standard meta‐analyses.

Methods for direct treatment comparisons

We conducted a pooled analyses in RevMan5 for all the included anti‐TNF inhibitors to assess for a class‐effect of harms of anti‐TNF agents. We used the Peto OR statistic which uses a fixed‐effect model because the data consisted of rare events (< 10%). Although not specified a priori, we decided to perform a sensitivity analysis using the Mantel‐Haenszel OR method with a standard continuity correction of 0.5 on those meta‐analyses in which we had used the Peto OR to check the robustness of our results (as recommended by Sweeting 2004).

Methods for indirect and mixed comparisons

Our primary analysis presents refined placebo estimates for the major outcomes ASAS40, partial remission, withdrawals due to AE, SAE and BASFI for each of the biologics using the network meta‐analysis methods described below. Using a Bayesian framework, the mixed treatment comparison (MTC) method provides a refined estimate of the treatment effect by combining the information from the direct and indirect data to strengthen the precision of the estimate of effect. This methodology utilizes techniques to preserve the randomisation inherent in the RCTs. It avoids the “naive” method of pooling the results across trials from the different treatment arms of interest and then comparing the results of treatment A versus treatment B versus treatment C. This naive method ignores the randomisation that was present in the original RCTs and introduces biases expected in an observational cohort (i.e. potential confounders are no longer likely to be randomly distributed between the treatment groups) (Bucher 1997; Wells 2009).

We used WinBUGS software (MRC Biostatistics Unit, Cambridge, UK) to conduct the Bayesian mixed treatment comparison meta‐analysis using a binomial likelihood model for dichotomous outcomes or a normal likelihood model for continuous outcomes which allows for the use of multi‐arm trials (Dias 2011a; Dias 2011b; Spiegelhalter 2003) and used the placebo as the reference group. We assigned vague priors, such as N(0, 1002), for basic parameters of the treatment effects in the model (Dias 2011b) and considered informative priors for the variance parameter in the random‐effects model (Turner 2005). To ensure convergence was reached, we assessed trace plots and the Brooks‐Gelman‐Rubin statistic (Spiegelhalter 2003). Three chains were fit in WinBUGS for each analysis, with at least 10,000 iterations, and a burn‐in of at least 10,000 iterations (Ades 2008; Spiegelhalter 2003).

We conducted both fixed‐effect and random‐effects network meta‐analyses; we assessed the deviance information criterion and compared the residual deviance to the number of unconstrained data points to assess model fit and determine the choice of model (Dias 2011a; Dias 2011b; Spiegelhalter 2003). For all analyses, the deviance information criterion and residual deviance for both models were close to each other. We used the random‐effects model as the primary results, as this model takes into consideration between‐study variation, whereas fixed‐effect models assume all the trials are estimating the same treatment effect (Cooper 2009; Dias 2011b).

For the continuous outcome, we derived mean and standard deviation for mean difference (MD) using Markov Chain Monte Carlo methods. We assigned vague priors for both basic parameters and the variance parameter in the models.

Summary of Findings table

We compiled 'Summary of findings' tables using GRADEpro (GRADEpro 2014) to improve the readability of the review. The outcomes included in the 'Summary of findings' table are: ASAS40, ASAS partial remission, BASFI, MRI, radiographic progression, withdrawals due to adverse events, and serious adverse events.

For dichotomous outcomes, we calculated the number needed to treat (NNT) from the control group event rate and the risk ratio using the Visual Rx NNT calculator (Cates 2008). We calculated the corresponding risk as per the GRADEPro Help file (Schünemann 2009): Risk (per 1000 people) = 1000 × assumed control risk × risk ratio (RR). We obtained the assumed control risk from the placebo estimate in the network meta‐analysis. The absolute increased benefit or harm and 95% CI was calculated as the corresponding risk minus the assumed control risk. The relative percentage change was calculated as the RR‐1.

For continuous outcomes, we calculated the NNT for the continuous measures of BASFI using the Wells calculator (available at the Cochrane Musculoskeletal Group editorial office). We used a minimally clinically important improvement of 0.7 points on a 0 to 10 scale as per the findings of Pavy 2005. We calculated the absolute benefit as the improvement in the intervention group minus the improvement in the control group, in the original units. We calculated relative percentage change as the absolute benefit divided by the control event rate.

We used the GRADE considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias) to assess the quality of a body of evidence as it relates to the studies which contribute data to the meta‐analyses for the prespecified outcomes. We used the methods and recommendations described in Section 8.5, 8.7, Chapter 11, and Section 13.5 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011; Schünemann 2011) using GRADEpro software. We provided footnotes to justify all decisions to down‐ or up‐grade the quality of studies.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned the following subgroup analyses a priori in order to explore possible effect size differences.

Intervention ‐ different dose; trial duration.

Characteristics of participants ‐ different ankylosing spondylitis classification criteria; severity of baseline disease (based on BASDAI, BASFI); age; disease duration; sex; with or without peripheral joint involvement.

Sensitivity analysis

We prespecified sensitivity analysis to assess the effect of study quality (proper generation of randomisation sequence, and adequate allocation concealment and blinding) on the overall estimates of effect.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

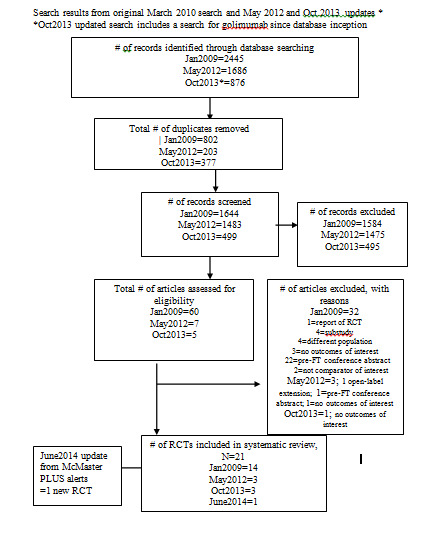

January 2009: The search of the electronic databases listed in the methods section for RCTs resulted in 2445 records. After de‐duplication, there were 1644 records left to screen. We assessed a total of 60 records in depth to see if they met the inclusion criteria. We included two additional articles from handsearching European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) abstracts on their website.

After assessing all the records, we included 14 trials, with 24 published articles (either abstracts or full‐text articles) related to those trials. The additional articles related to a trial are listed as secondary references in the reference section.

Updated search May 2012: The search of the electronic databases listed in the methods section for RCTs resulted in 1686 records. After de‐duplication, there were 1483 records left to screen. We assessed seven records to see if they met the inclusion criteria. We did not conduct any handsearching since American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and EULAR conference abstracts were indexed electronically. We added three new studies.

Updated search October 2013: This search also included a search for golimumab from database inception as well as an update of the original search. After de‐duplication, we screened 499 records. We assessed four articles in depth and identified three new studies.

An update from the McMaster PLUS database in June 2014 alerted us to one new study and the full‐text publication of a previously included abstract.

A search of clinicaltrials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov/) in October 2014 found 89 records, but we did not identify any new completed trials.

A flow chart of the search results is provided in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow chart Note: October 2013 search included retrospective search for golimumab from database inception

Included studies

Further details on each included study are available in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Twenty‐one RCTs met the inclusion criteria with a total of 3308 participants. One thousand and twelve people received etanercept in 10 studies (Barkham 2010; Brandt 2003; Braun 2011; Calin 2004; Davis 2003; Dougados 2011; Gorman 2002; Giardina 2009, Huang 2008; Navarro‐Sarabia 2011; van der Heijde 2006b); 327 people received infliximab in 5 studies (Braun 2002;Giardina 2009; Inman 2010; van der Heijde 2005) (28 in combination with methotrexate (Marzo‐Ortega 2005); 501 received adalimumab in 4 studies (Hu 2012; Huang 2014; Lambert 2007; van der Heijde 2006a); 246 received golimumab in 2 studies (Bao 2014; Inman 2008). One study was an open‐label head‐to‐head study of etanercept (N = 25) and infliximab (N = 25) (Giardina 2009).

Eighteen RCTs contributed data to the mixed treatment comparison analysis: adalimumab (4 studies; Hu 2012; Huang 2014; Lambert 2007; van der Heijde 2006a), etanercept (8 studies; Barkham 2010; Brandt 2003; Calin 2004; Davis 2003; Dougados 2011; Gorman 2002; Huang 2008; van der Heijde 2006b), golimumab; 2 studies (Bao 2014; Inman 2008), infliximab (3 studies; Braun 2002; Inman 2010; van der Heijde 2005)) and one head‐to‐head study of etanercept to infliximab (Giardina 2009).

Additional data

We received additional data from the trial authors for the following studies: Brandt 2003, Braun 2002, Calin 2004, and Davis 2003 (though we were unable to use data from Davis 2003 since variance was not provided in the additional information received). This was mainly to obtain data on clinical endpoints where the published results for continuous outcomes had been reported as a statistic different from the mean and SD which is required for entry into Review Manager 5. We also sought additional details to clarify risk of bias items for some studies (Davis 2003; van der Heijde 2006a).

Participants

The majority of participants were Caucasian males in their early forties. The percentage of male participants in the treatment groups ranged between 65% to 80%, and 74% to 100% in the control groups. The mean age ranged from 38 to 45 years in the treatment groups and 39 to 47 years in the control groups. Between 75% and 98% of the participants in the treatment groups were Causasian with a similar distribution in the control groups (70% to 97%).

The mean disease duration in the treatment groups ranged from 8 to 16 years, and 10 to 17 years in the control groups.

Interventions

Table 2 summarizes the concomitant therapy permitted in each study.

1. Concomitant permitted therapy by study.

| Study ID | Concomitant/Background treatment |

| Adalimumab | |

| Lambert 2007 | Not reported |

| van der Heijde 2006a | Allowed to continue sulphasalazine (3 g/day), methotrexate (25 mg/week), hydroxychloroquine (400 mg/day), prednisone or prednisone equivalent (10 mg/day), and NSAIDs, if the dose had remained stable for at least 4 weeks before the baseline visit |

| Hu 2012, Huang 2014 | Concomitant use of methotrexate (≦ 25 mg/week), sulphasalazine (≦ 3 g/day), prednisone (≦ 10 mg/day), NSAIDs and/or analgesics was allowed but dose adjustments, induction and/or discontinuation of these therapies was not permitted |

| Etanercept | |

| Brandt 2003 | Allowed NSAIDs at the same or less dose at baseline |

| Calin 2004 | Allowed prestudy physiotherapy |

| Davis 2003, Gorman 2002, van der Heijde 2006b | Allowed stable doses of DMARDs, NSAIDs, and oral corticosteroids |

| Huang 2008 | Allowed stable DMARDs doses |

| Barkham 2010 | Allowed stable doses of DMARDs (sulphasalazine or methotrexate) and/or a NSAID for the duration but not corticosteroids |

| Golimumab | |

| Bao 2014, Inman 2008 | Allowed to continue concurrent treatment with stable doses of methotrexate, sulphasalazine, and hydroxychloroquine |

| Inman 2008 | Allowed to continue concurrent treatment with stable doses of methotrexate, sulphasalazine, and hydroxychloroquine, corticosteroids, and NSAIDs |

| Infliximab | |

| Braun 2002, van der Heijde 2005 | Allowed to continue on stable doses of NSAIDs |

| Inman 2010 | Concomitant therapy of NSAIDs, corticosteroids, analgesics, and DMARDs were allowed as long as doses remained stable in the study |

| Marzo‐Ortega 2005 | Allowed concomitant use of NSAIDs or oral corticosteroids |

DMARD ‐ disease‐modifying anti‐rheumatic drug NSAID ‐ non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug

Adalimumab

Four studies assessed adalimumab at a dose of 40 mg every other week subcutaneously. Lambert 2007 and van der Heijde 2006a at 40 mg every other week for a 24‐week double‐blind period, though an early escape option was available after week 12. Both Hu 2012 and Huang 2014 had a 12‐week double‐blind phase.

Concomitant therapy

Lambert 2007 did not mention concomitant therapy. In van der Heijde 2006a, patients were allowed to continue sulphasalazine (3 g/day), methotrexate (25 mg/week), hydroxychloroquine (400 mg/day), prednisone or prednisone equivalent (10 mg/day), and NSAIDs, if the dose had remained stable for at least 4 weeks before the baseline visit. In Hu 2012 and Huang 2014, concomitant use of methotrexate (≦ 25 mg/week), sulphasalazine (≦ 3 g/day), prednisone (≦ 10 mg/day), NSAIDs and/or analgesics was allowed but dose adjustments, induction and/or discontinuation of these therapies was not permitted.

Etanercept

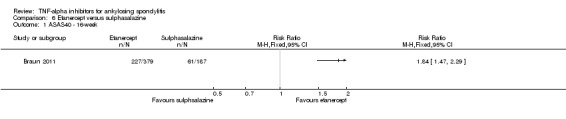

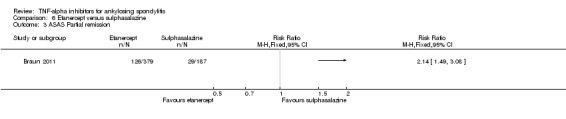

Four RCTs assessed etanercept at a dose of 25 mg twice weekly, delivered subcutaneously against placebo (Barkham 2010; Brandt 2003; Calin 2004; Davis 2003; Gorman 2002). van der Heijde 2006b assessed 50 mg once weekly versus 25 mg twice weekly versus placebo. Huang 2008 used 50 mg once weekly versus placebo. Navarro‐Sarabia 2011 assessed a high dose, 50 mg twice weekly, against the standard dose of 50 mg once weekly. Dougados 2011 assessed the effect of etanercept 50 mg once weekly against placebo in participants with advanced ankylosing spondylitis. Braun 2011 compared 50 mg once weekly to 3 g daily of sulphasalazine. The length of treatment ranged from 6 weeks (Brandt 2003 and Huang 2008) to 24 weeks (Davis 2003).

Concomitant therapy

Brandt 2003 allowed NSAIDs at the same or less dose at baseline; Calin 2004 allowed pre‐study physiotherapy; Davis 2003; Gorman 2002 and van der Heijde 2006b allowed stable doses of disease‐modifying anti‐rheumatic drugs, NSAIDs, and oral corticosteroids; Huang 2008 allowed stable disease‐modifying anti‐rheumatic drug doses; Barkham 2010 allowed stable doses of disease‐modifying anti‐rheumatic drugs sulphasalazine or methotrexate and/or a NSAID for the duration, but not corticosteroids.

Golimumab

Two studies assessed subcutaneous golimumab at a dose of 50 mg every 4 weeks (Bao 2014; Inman 2008). Both had a 24‐week double‐blind phase and an early escape option after week 16.

Concomitant therapy

In Bao 2014 and Inman 2008, patients were allowed to continue concurrent treatment with stable doses of methotrexate, sulphasalazine, and hydroxychloroquine. In Inman 2008, stable doses of corticosteroids, and NSAIDs were also allowed.

Infliximab

Four RCTs assessed infliximab; Braun 2002 assessed infliximab at 5 mg/kg intravenously at weeks 0, 2, and 6. van der Heijde 2005 delivered this same dose of infliximab at weeks 0, 2, 6, 12 and 18 weeks. Inman 2010 evaluated infliximab at 3 mg/kg delivered at weeks 0, 2, and 6. Marzo‐Ortega 2005 assessed infliximab (5 mg/kg) in combination with methotrexate against placebo plus methotrexate.

Concomitant therapy

In both Braun 2002 and van der Heijde 2005, patients were allowed to continue on stable doses of NSAIDs. It appears concomitant therapy of NSAIDs, corticosteroids, analgesics, and disease‐modifying anti‐rheumatic drugs were allowed as long as doses remained stable in the Inman 2010 study. Marzo‐Ortega 2005 allowed concomitant use of NSAIDs or oral corticosteroids.

Outcomes

All studies used the outcomes recommended by the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society. The primary outcome in two studies was the BASDAI ≥ 50% (Brandt 2003; Braun 2002) and the ASAS20 in 14 studies (Bao 2014; Braun 2011; Calin 2004; Davis 2003; Gorman 2002; Huang 2008; Huang 2014; Inman 2008; Inman 2010; Lambert 2007; Navarro‐Sarabia 2011; van der Heijde 2005; van der Heijde 2006a; van der Heijde 2006b). The change in BASDAI score was the primary outcome in Marzo‐Ortega 2005.

In Dougados 2011, the primary outcome was the area under the curve in the BASDAI between baseline and week 12.

In Barkham 2010, the primary outcome was a change in the work instability of patients after three months, as measured by the Ankylosing Spondylitis Work Instability Scale.

In the abstract of Giardina 2009, the primary outcome was stated to be the proportion of patients achieving a 50% BASDAI response at week 102; Secondary: ASAS50; BASFI, back pain, morning stiffness, C‐reactive protein, and spinal mobility. However, in the full‐text article, the outcome defined as primary is not stated, and the 50% BASDAI response is not reported. ASAS20, ASAS40, BASDAI, BASFI, and adverse events were reported.

Hu 2012 did not state a primary outcome. Clinical outcomes like BASDAI and BASFI were reported along with lab measures (C‐reactive protein and serum DKK‐1) and imaging (MRI of both the lumbar spine and sacroiliac joints).

Source of funding

A total of 17 studies reported some type of industry sponsorship.

van der Heijde 2005 was supported by Centocor. Braun 2002 was funded by a grant from the German Minstry of Research and by Essex Pharma who provided the study drug. Inman 2010 did not report the funding source in the abstracts but the trial protocol states the study was sponsored by Schering‐Plough. Marzo‐Ortega 2005 reported that the study was supported by a grant in aid from Schering‐Plough, UK.

Brandt 2003 was supported by a grant from the German Minstry of Research and by Wyeth Pharma who provided the study drug. Calin 2004 was funded by Wyeth Research. Gorman 2002 was funded by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases and Immunex. The trial report states that Immunex was "not involved in the study design, data collection, statistical analysis, or manuscript preparation". Davis 2003 was supported by Immunex Corporation. van der Heijde 2006b was supported by Wyeth Pharmaceuticals (study drug and grants to investigational sites) Braun 2011 and Dougados 2011 were also supported by Wyeth, which was acquired by Pfzier in 2009. Navarro‐Sarabia 2011 was supported by Pfizer.

van der Heijde 2006a and Lambert 2007 were sponsored by Abbott Laboratories. Huang 2014 was sponsored by AbbVie.

Bao 2014 was funded by Janssen Research and Development. Inman 2008 was supported by Centocor Research and Development, Inc. and the Schering‐Plough Research Institute, Inc.

Barkham 2010, Giardina 2009, Hu 2012, and Huang 2008 did not list any source of funding.

Excluded studies

We excluded 6 studies after assessing the full‐text articles. The Characteristics of excluded studies table provides more details for the exclusions. Briefly, the participants in three studies (Barkham 2008b;Breban 2008; Haibel 2008) did not meet the review's inclusion criteria; the intervention in Li 2008 assesses the effect of methotrexate, not infliximab; and there is no separate information provided for ankylosing spondylitis patients in Van den Bosch 2002 (and we were unable to obtain this from the author). Morency 2011 provided data on the open‐label extension results of an included study.

Risk of bias in included studies

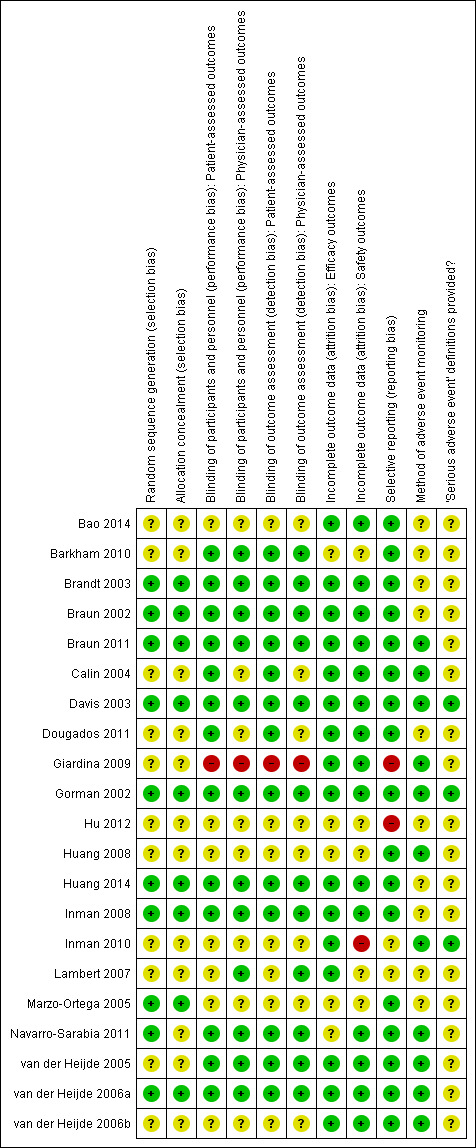

Figure 2 provides a graphical summary of the risk of bias of the included studies.

2.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

We received additional information from study authors on methodology and data for Davis 2003, Gorman 2002, and van der Heijde 2006a.

Huang 2008 was reported as an abstract, and did not provide enough information to make a judgement about risk of bias, and so was judged as 'unclear'.

Sequence generation

Bao 2014, Barkham 2010, Calin 2004, Dougados 2011, Giardina 2009, Hu 2012, Inman 2010, Lambert 2007, van der Heijde 2005, and van der Heijde 2006b did not provide any information regarding sequence generation, and so the judgement was 'unclear'. The 10 other studies provided evidence of appropriate generation of the randomisation sequence.

Allocation

Bao 2014, Barkham 2010, Calin 2004, Dougados 2011, Giardina 2009, Inman 2010, Hu 2012, Lambert 2007, Navarro‐Sarabia 2011, van der Heijde 2005, and van der Heijde 2006b did not provide information regarding the method of allocation concealment. The nine other studies provided evidence of appropriate concealment of allocation of the randomisation sequence.

Blinding of patient assessed outcomes

Barkham 2010, Braun 2002, Braun 2011, Brandt 2003, Calin 2004, Davis 2003, Dougados 2011, Gorman 2002, Huang 2014, Inman 2008, and van der Heijde 2005 reported the patient was blinded. We were unclear about the methods of blinding in Bao 2014, Hu 2012, Inman 2010, Lambert 2007, Marzo‐Ortega 2005, van der Heijde 2006a, and van der Heijde 2006b which were reported only as "double blind". There was no blinding in Giardina 2009, which places it at a high risk of bias.

Blinding of physician reported outcomes

Barkham 2010, Braun 2002, Brandt 2003, Davis 2003, Gorman 2002, Hu 2012, Huang 2014, Inman 2008, Lambert 2007, van der Heijde 2005, and van der Heijde 2006a reported that the investigator was blinded. Calin 2004 did not specify who other than the patient was blinded and physician/investigator blinding was unclear in Dougados 2011, Marzo‐Ortega 2005, and van der Heijde 2006b. There was no blinding in Giardina 2009 which places it at a high risk of bias.

Incomplete outcome data

We judged all trials but five trials to be at low risk of incomplete outcome data bias for beneficial outcomes as there was a low rate of missing data and most conducted an intention‐to‐treat analysis. Five were judged as unclear.

Selective outcome reporting

We judged most of the trials to be at low risk of selective outcome reporting bias as they reported on outcomes recommended by the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society, with the exception of Giardina 2009 and Hu 2012 which we judged as 'high risk'. In Giardina 2009, the abstract we found first for this trial had the primary outcome listed as the proportion of people achieving a 50% response in BASDAI. However, the full‐text article did not report this outcome. We could not find a protocol for this trial. Hu 2012 did not state their primary outcome nor any adverse event data. In terms of risk of bias for selective adverse event reporting, we judged Inman 2010 and Lambert 2007 as ‘unclear’ given the lack of specifics provided on harms data. In Lambert 2007, the primary outcome was reported in an abstract but not in the full‐text article.

Method of adverse event monitoring

The following studies stated that the patients were actively monitored (though few details were provided on the specifics of the monitoring) for adverse events. These were judged to be at low risk of bias: Calin 2004, Davis 2003, Giardina 2009, Gorman 2002, Huang 2008, Navarro‐Sarabia 2011, van der Heijde 2005, van der Heijde 2006a, and van der Heijde 2006b. The rest of the studies did not mention how the patients were monitored for adverse events and were judged as 'unclear' risk of bias.

Definition of serious adverse event provided

The following studies used a common grading system, though the specific definition of serious adverse events was not provided in the articles: Davis 2003, Gorman 2002, Inman 2010; we judged these to be at low risk of bias. van der Heijde 2005 and van der Heijde 2006a did not provide general serious adverse events definitions, but each serious adverse event was clearly explained in the published report. The other studies did not report their definition of 'serious adverse events' and we judged them to be at unclear risk of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

The review prespecified that outcomes measured at six months or less would assess short‐term results and greater than six months would assess long‐term results; however, all outcomes in the placebo‐controlled trials were reported at six months or less.

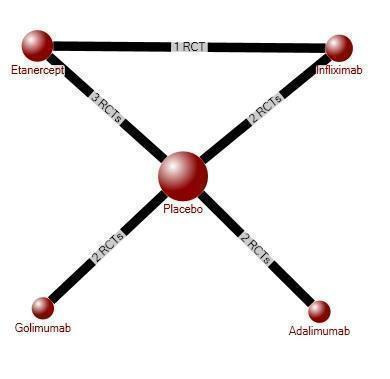

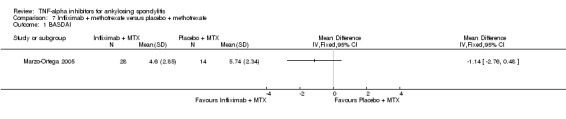

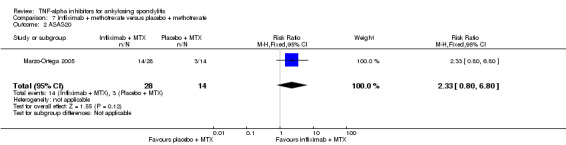

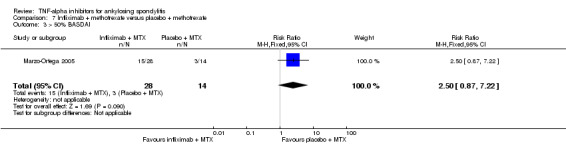

Table 1 provides an overview of the mixed treatment comparison refined placebo estimates for the major outcomes of ASAS40, physical function, ASAS partial remission, withdrawals due to adverse events and serious adverse events for the individual biologics and for the class‐effect analysis for the two adverse event outcomes. We did not pool data from magnetic resonance imaging and radiographic progression outcomes. Figure 3 shows the network diagram for ASAS40. Figure 4 and Figure 5 show the forest plots for the biologic versus placebo and head‐to‐head mixed treatment comparison estimates for the outcomes ASAS40 and withdrawals due to adverse events, respectively. The pairwise data for the individual trials that was used in the mixed treatment comparison analysis is available in the Data and Analyses section. Trace plots and Brooks–Gelman–Rubin statistic indicated convergence of the model in all analyses.

3.

ASAS40 Evidence Diagram

4.

Forest Plot: ASAS40

5.

Forest Plot: Withdrawals due to adverse events

Individual biologics

Adalimumab (40 mg every other week) versus placebo

Four studies assessed the effect of adalimumab versus placebo (Hu 2012; Huang 2014; Lambert 2007; van der Heijde 2006a). Lambert 2007 did not report all benefits and adverse events in the published article but they were reported in an abstract and other publications of the same trial (Maksymowych 2005; Maksymowych 2008). Hu 2012 did not report on any adverse outcomes.

Major outcomes

ASAS40: There was high quality evidence that the adalimumab group was more likely than placebo to achieve the ASAS40 criteria (risk ratio (RR) 3.53, 95% credible interval (Crl) 2.49 to 4.91, with an absolute improvement of 33% (95% Crl 19% to 51%) and a NNT = 4 (95% confidence interval (CI) 2 to 6)).

Physical function (BASFI 0 to 10 scale, lower is better): There was high quality evidence of a clinically important improvement in physical function (mean difference (MD) ‐1.6, 95% CrI ‐2.2 to ‐0.9), with an absolute increased benefit of ‐16% (95% Crl ‐22% to ‐9%)); relative percentage change from baseline = ‐32% (95% CrI ‐44% to ‐18%); and NNT to achieve the minimally important difference (MCID) of 0.7 points = 4 (95% CI 3 to 5).

ASAS partial remission: There was moderate quality evidence (downgraded for imprecision) that the adalimumab group was more likely than placebo to meet the criteria for partial remission (RR 6.28, 95% Crl 3.13 to 12.78), with an absolute improvement of 16% (95% Crl 6% to 35%) and a NNT = 7 (95% CI 3 to 16).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): There was moderate quality evidence of a small absolute improvement on spinal inflammation with unclear clinical relevance. Hu 2012 (N = 46) assessed spinal inflammation using the Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada (SPARCC) scoring method. SPARCC scores for the spine can range from 0 to 108 and SPARCC sacroiliac joint scores can range from 0 to 72. The MD for the lumbar spine was ‐6.5 (95% CI ‐13.06 to 0.06), with a small absolute benefit of ‐6% (95% CI ‐12% to 0.05%) and relative percentage change = ‐33% (95% CI ‐66% to 0%). The MD for the sacroiliac joint was ‐3.00 (95% CI ‐7.46 to 1.46).

Lambert 2007 used MRI to assess the effect of adalimumab compared to placebo in reducing spinal and sacroiliac joint inflammation using the SPARCC scoring method. MRIs were obtained for all participants (N = 82) at baseline and week 12. There was high quality evidence of a statistically significantly greater reduction in the mean spine SPARCC score of adalimumab‐treated patients (median change 6.3, range 34.0 to 2.0) compared with placebo‐treated patients (median change 0.5, range 26.0 to 13.5) (P < 0.001). The mean sacroiliac joint SPARCC score also decreased significantly between the adalimumab (median change 0.5, range 22.5 to 2.5) and placebo groups (median change 0.0, range 13.5 to 16.0) (P < 0.001). In terms of percentage change from baseline, placebo‐treated patients had a 9.4% mean increase in spine SPARCC scores compared to a 53.6% mean reduction in scores in adalimumab‐treated patients (P < 0.001). There was also a significant difference in the mean percentage reduction in adalimumab (52.9%) and placebo‐treated (12.7%) patients in the sacroiliac joint SPARCC score (P = 0.017).

Radiographic progression: Not reported.

Withdrawals due to adverse events: Based on moderate quality evidence, we are uncertain of the effect on withdrawals due to adverse events (RR 1.69, 95% CI 0.35 to 10.84) but the absolute numbers were low: 6/437 in the adalimumab group versus 2/222 in the placebo (absolute increased harm = 0.6% (95% Crl ‐0.4% to 7%); relative percentage change = 69% (95% CI ‐65% to 984%). We downgraded the evidence due to the low event rates and resulting imprecision.

Serious adverse events: Based moderate quality evidence, we are uncertain of the effect on serious adverse events (RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.26 to 3.93) but the absolute numbers were low: 7/437 in the adalimumab group versus 4/222 in the placebo (absolute increased harm = ‐0.2% (95% Crl ‐1.1% to 4.4%); relative percentage change = ‐8% (95% CI ‐74% to 293%)). We downgraded the evidence due to the low event rates and resulting imprecision.

Etanercept (25 mg twice weekly or 50 mg once weekly) versus placebo

Five studies assessed the effect of etanercept 25 mg twice weekly versus placebo (Barkham 2010; Brandt 2003; Calin 2004; Davis 2003; Gorman 2002). Two studies assessed the effect of 50 mg of etanercept once weekly versus placebo (Dougados 2011; Huang 2008).