Especially in low

and middle-income countries, key constraints such as dense traffic flows, jams, and pollution constitute frequent issues that potentially explain many negative consequences in terms of (e.g.) efficiency, sustainability, and mobility safety. In this regard, recent evidence supports the idea that fostering public transportation is crucial to offering solutions for this difficult panorama. However, transport mode-related choices and shifts have been proven to depend highly on key perceptions and needs of potential users. The aim of this study was to analyze a set of key users’ perceptions, usage, and perceived quality of public transportation in the Dominican Republic, as well as to explore the most relevant features for Dominicans from the “desired quality” paradigm. For this research at a national level, data retrieved from a nationwide sample of 1254 inhabitants of the Dominican Republic was used, proportional to the ONE census in terms of sex, age, habitat, and region. Overall, the results show that the general quality of transportation is 6.70 points out of 10. The use of public transportation in the Dominican Republic has a medium-low rating and is very focused on urban buses (41 %) and public cars (27.1 %). Nonetheless, the metro remains the most highly rated means of transport (M = 8.75). Concerning the quality variables analyzed, the highest scores are for accessibility (M = 7.08) and frequency of service (M = 6.99). Further, Dominicans focus on improving comfort, vehicle conditions, and safety. This study constitutes a first approximation to the desired quality of public transportation for Dominican Citizens, which may help policymakers scope user-based needs in public transportation systems and encourage a more frequent (and friendlier) public transport use in the country.

Keywords: Dominican Republic, Public transportation, Quality, Perception, Safety, Mobility

1. Introduction

After several decades, one of the most traditional concerns explaining mobility issues of many cities remains the extensive number of private vehicles daily crowding urban areas [1]. Apart from the classic problem of traffic jams, this situation also encompasses other negative outcomes, such as deepening social inequities, commuting stress among occasional and frequent road users, high levels of environmental pollution, and (overall) impaired transport dynamics [2,3]. Additionally, this panorama explains that traffic crash rates can worsen, while many users may avoid using public transportation as it is usually considered inefficient and insecure [4].

Notwithstanding, what in the first light seems to be the problem could partake in the solution. We speak, of course, of the strengthening of public transport as an effective strategy to decongest the streets and improve the mobility habits of the population, especially in the case of low and middle-income countries (LMICs), where a large part of the population uses it mainly for convenience [5,6]. On the other hand, private cars have shown to be the preferred alternative in many industrialized or high-income countries, even though they constitute those vehicles with the highest energy need per traveler and kilometer, as they use twice as much energy as metros and up to four times more than what is needed for a bus [7]. Therefore, during the past few years, many efforts have been made to improve the efficiency and quality of public transportation, thus aiming to make it more attractive for citizens and potentially fostering its daily use among them [8].

Similarly, a paradigm change has been shown in transportation research dynamics during the last few years. Traditional research on perceived quality trends provides knowledge on the impact triggered by the decisions taken by transport companies on their users (commonly perceived as “clients”). In contrast, current studies are growingly starting to focus on users themselves as key stakeholders for assessing both the current quality and further needs of public transportation systems [9].

This emphasis has shown to have a certain potential for developing contextual insights, helping transport planners and policymakers to adjust new actions and strategies to users' actual needs. In other words, the objective pursued by this paradigm is that perceived quality may be equal to users' desired quality. Likewise, recent studies highlight how important it is to change the public's habits of daily public transportation, favoring the choice of more sustainable alternatives for their movements that may encompass improvements in further spheres, such as their economy, security, and mental health [10]. Moreover, most studies dealing with public transport-related actions performed during the last decade also agree on the fact that knowing the movement dynamics of a context before intervening is crucial so that the public transportation offer would be more likely to adjust to the motivations and needs of users [8].

1.1. Study framework

The study of public transport on a global scale reveals the complexity of the criteria that influence the choice between this mode of transport and private alternatives [11]. Generally, the user can always choose between different displacement modes with very heterogeneous characteristics. Therefore, factors such as cost, accessibility, convenience, and environmental concerns are critical determinants in this choice [12]. Cost plays an important role, as affordable public transport systems tend to attract higher ridership, especially in urban contexts where the costs of operating a private vehicle can be significant [13]. In addition, the accessibility of public transport stops and stations, as well as their proximity to origin and destination locations, strongly influence the decision to use public transport [14].

Convenience and service quality are crucial factors [15]. Public transport systems that offer reliable frequency and punctuality tend to be more attractive to users [16]. The ability to make direct trips without transfers is also valued for the efficiency it brings to travel time [17]. Furthermore, in congested urban areas, where finding parking and dealing with traffic are challenges, public transport can present itself as a more convenient alternative [18].

On the other hand, there are reasons to avoid public transportation. Some individuals prefer the convenience, privacy, and flexibility private vehicles offer [19]. Travel time is another decisive factor: if public transport involves indirect routes or long waits, some users may opt for faster means of transportation [20]. The perception of service quality also plays a significant role, including aspects such as cleanliness, safety, and overall travel experience [21]. In relation to safety, several studies have shown that it is a particularly relevant factor in women's choice of transport, with public transport vehicles and bus stops or stations being perceived as unsafe and more likely to suffer a situation of harassment or sexual aggression, especially at night [22,23].

Moreover, as a result of the several constraints generated by COVID-19 (which also impacted greatly the public transportation sphere), many people choose not to use public transport to avoid crowds and maintain social distancing [24]. The reduction in the use of public transport as a result of the restrictions implemented during the pandemic has been evidenced in research in different countries such as China [25], Spain [26], the United States [27], and Australia [28], among others, being a majority scenario at the international level.

In addition to the previously mentioned attributes or characteristics of the transport service, the choice of transport is influenced by other factors, such as individual characteristics, lifestyle, psychological factors, and situational variables [29]. Along these lines, Klöckner & Friedrichsmeier (2011) [30] propose a multilevel approach model that integrates psychological variables (such as car use habit, social norms, intention or attitudes) and situational conditions (such as trip purpose, vehicle access, weather conditions, or trip duration) to explain travel mode choice, which has been empirically demonstrated.

Complementarily, considering different factors, Beirão & Cabral (2007) [31] point out that users mostly identify cost, the ability to rest during the trip, and the lower stress compared to driving a motor vehicle as advantages of public transport. On the contrary, the main disadvantages are related to the lack of comfort, the large number of people occupying the vehicle, the lack of flexibility, and the travel and waiting time, especially when more than one mode of transport is to be used.

In the context of emerging Latin American countries, the situation is particularly complex. Population density in many cities in the region can favor the viability of public transport but can also generate challenges in terms of congestion and urban planning [32]. Moreover, the growth of the middle class in these countries may lead to increased demand for customized transportation options, which could have implications for public transport utilization [33]. Socioeconomic inequalities also influence transport mode choice, as economic and social factors can disproportionately impact vulnerable segments of the population [34].

Insufficient investment and funding in public transport infrastructure and services can result in unreliable and low-quality systems, negatively affecting adoption [35]. Consequently, citizens' opinions about this service are often negative [36]. In this regard, to date, several studies address the "perceived quality" of public transport as seen by users [9]. However, none of them has been conducted in the Dominican Republic. Following this approach, the quality of public transport systems comprises many factors, including users' evaluations of their accessibility [37], service frequency and transit transfer [38], cost and affordability [39], safety [21], safety [40] time required for the trip [41], condition, cleanliness, and comfort of the vehicles [32]. Therefore, this seems a relevant topic to explore in the case of an emerging country whose population could benefit from user-based improvements in the configuration of available public transport modes [42].

Accordingly, several studies point out that to increase the use of public transport, the characteristics of the service must be designed and planned to adapt to the requirements and needs of users, in order to attract potential customers [43]. Strategies aimed at encouraging the use of public transport should focus on improving its public perception. Nevertheless, at the same time, public transport systems must become more efficient and competitive in the market [44]. This implies improving the quality of service, which can only be achieved by understanding in detail the travel patterns and the needs and expectations of users [45].

1.2. The Dominican Republic in figures: road traffic and mobility context

The Dominican Republic is a country located in Central America with more than 11 million inhabitants. In recent years, the National Institute of Traffic and Land Transportation (INTRANT) has undertaken multiple actions to reduce the country's road accident rates, which are among the highest in the world [45]. In fact, the Pan American Health Organization places the Dominican Republic among the top five countries with the highest rate of road traffic fatalities from 2000 to 2019 [46].

These high figures are the consequence of a set of factors such as poor infrastructure, lack of road education and training for drivers, or the poor condition of vehicles [47,48]. In this sense, the choice of mode of transport for regular commuting is also an influencing variable. According to the 2022 statistical bulletin of the General Directorate of Internal Taxes [49], the vehicle fleet increased to 5,463,996 units, representing an increase of 6 % over the previous year. Thus, motorcycles, which have presented the highest number of accidents according to available statistics, had a growth of 6.6 % with respect to 2021, with 189,114 new registrations. This type of vehicle represents more than half of the entire vehicle fleet and represents the main form of travel for Dominican citizens.

In addition to travel by private means of transportation, some citizens opt for the use of public transportation. The National Mobility Survey [50] reflects that approximately half of the population has made some of its trips in one of the available public transportation modes. In this sense, the most used are urban buses (called "guagua") and motorcycle cabs (called "motoconchos"). Although this may seem a positive aspect, the characteristics of these means of transport can lead to traffic jams in urban areas and mobility problems. Urban buses and, especially, motorcycle cabs involve a large number of vehicles with small passenger capacity and high age, which do not have specific programmed routes but adjust to the needs of their customers to design their routes and stops, which are changeable [51]. Therefore, this circumstance causes difficulties in directing vehicular traffic and for an adequate traffic flow [52].

There are also other means of public transportation, although they are not available in all regions of the country. This is the case of the metro and the metropolitan buses (called "Autobuses OMSA", for its acronym Oficina Metropolitana de Servicios Públicos de Autobuses del país). In both cases, they only exist in some cities, such as Santo Domingo or Santiago, so they can only transport a small percentage of the population that uses public transportation [53]. Furthermore, in recent years, national and local authorities have tried to promote sustainable transport through communication and awareness campaigns [54,55]. However, the lack of safety perceived by users and deficits in infrastructure do not favor this type of travel. Thus, 2018 data indicate that only 21 % regularly travel on foot, and less than 1 % make regular trips by bicycle [50].

Therefore, the Dominican Republic presents different challenges related to reducing road accidents in the region and improving the fluidity and mobility of vehicles, especially in the urban centers of its cities [56]. Some of the factors that explain the current problems are related to the overpopulation of motorized vehicles and the age and conditions of these vehicles. Further, the majority presence of motorcycles and motorcycle cabs, although they provide a convenient and economical form of travel for many Dominicans, also present important challenges in terms of road safety because they generally operate without regulation and with deficient safety standards [51]. This traffic context is similar to other emerging countries, especially in Latin and Central America, because the accelerated growth of cities and the mobility needs of citizens have not been sufficiently accompanied by specific actions and efficient transport networks in many of these countries.

Complementarily, one of the objectives of the authorities responsible for transport in the country has been to majorly improve the characteristics of public transport and invest in infrastructure to favor soft and sustainable modes of travel [57]. However, and especially in relation to collective transport, it is important to address the needs and requests of citizens in terms of accessibility, cost, safety, cleanliness, and comfort, as well as other formal aspects related to the established routes and stops of the country's public transport networks [[58], [59], [60]]. In the same way, the results obtained can be extrapolated to other regions with similar characteristics in terms of socioeconomic conditions and urban mobility context, especially in Latin America and Central America.

1.3. Objectives of the study

Bearing in mind the aforementioned considerations, this study aimed to analyze a set of key users’ perceptions, usage and perceived quality of public transportation in the Dominican Republic, as well as to explore the most relevant features for Dominicans under the desired quality paradigm.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

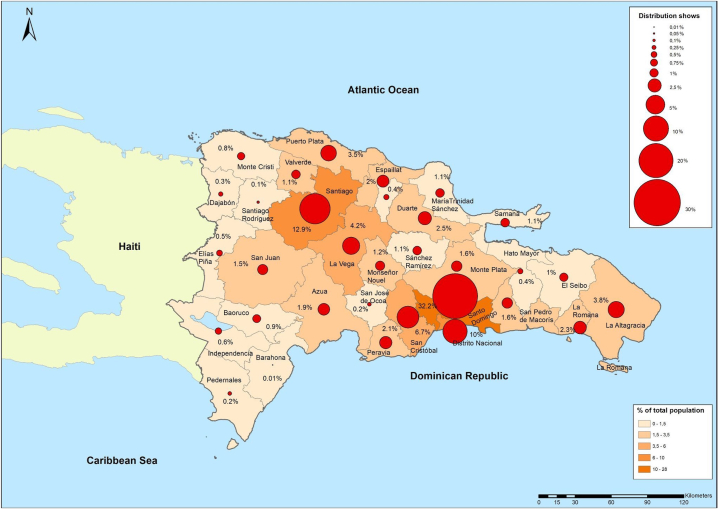

For this cross-sectional study, the data gathered from a nationwide sample was used, involving a total of n = 1254 Dominican citizens. A detailed summary of the partakers’ demographic features is shown in both Table 1, and the regional coverage in Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic data of the study participants.

| Variable | Category | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 628 | 50 % |

| Female | 628 | 50 % | |

| Total | 1254 | 100 % | |

| Age range | 18–24 | 260 | 20.6 % |

| 25–34 | 311 | 24.7 % | |

| 35–49 | 360 | 29.0 % | |

| 50–64 | 221 | 17.5 % | |

| >65 | 102 | 8.1 % | |

| Total | 1254 | 100 % | |

| Marital Status | Single | 431 | 34.2 % |

| Unmarried with partner | 50 | 4.0 % | |

| Married | 644 | 51.6 % | |

| Divorced/separated | 83 | 6.6 % | |

| Widow/widower | 46 | 3.7 % | |

| Total | 1254 | 100 % | |

| Do you have children? | Yes | 965 | 77.1 % |

| No | 289 | 22.9 % | |

| Total | 1254 | 100 % | |

| Educational level | Primary studies or lower | 379 | 30.2 % |

| Secundary-hight school | 609 | 48.6 % | |

| Technical studies | 6 | 0.5 % | |

| Undergraduate studies | 252 | 20.1 % | |

| Post-graduate studies | 8 | 0.6 % | |

| Total | 1254 | 100 % | |

| Working situation | Unemployed | 458 | 41.6 % |

| Retired | 41 | 3.7 % | |

| Employed full time | 213 | 19.3 % | |

| Employed part-time | 390 | 35.4 % | |

| Total | 1102 | 100 % | |

| Do you usually drive? | Yes | 437 | 37.3 % |

| No | 787 | 62.7 % | |

| Total | 1254 | 100 % |

Fig. 1.

Sample distribution according to participants' region of provenance, in correspondence with national census (ONE census) data.

Regarding the representativeness of the sample, it is worth acknowledging that the sample size was larger than necessary to ensure that the sample was representative. The minimum required assuming a level of confidence of 95 %, a maximum margin of error of 5 % (α = 0.05), and a beta (β) of 0.20, was n = 680 participants, but we obtained almost twice as many n = 1254 participants. In addition, the sample was representative of the national census of the Dominican Republic (ONE Census) for the variables gender, age (older than 18), province, and habitat. Subsequently, samples were randomly selected from each stratum proportional to their size in the population.

Participants took part in the study voluntarily and anonymously, filling out an informed consent explaining the core ethical considerations of this research. Any personal information was treated in compliance with the existing laws on data protection and following the current ethical guidelines applied to research involving human subjects.

2.2. Design, procedure and instruments

The data used in this study were collected through the National Survey on Mobility of the Dominican Republic, whose collection phase was carried out during the second half of 2019 [[61], [62]]. The questionnaire involved questions related to public transportation, knowledge of institutions and traffic laws, private transportation, mobility by bike, mobility on foot, and ITS systems and measures, which included the variables analyzed in this research.

The survey was carried out through in-person interviews. The sample was gathered from November 24th to December 7th. A CAPI system (computer-assisted interviews) was used to conduct the data collection, with the aid of recorded and geo-referenced tablets, so that the time of the interview would be reduced and record mistakes would be minimized.

To achieve the proposed objectives, we considered the following variables.

-

-

Public transportation use: frequency of general use, requiring a single response on the subjective demand of public transportation means (i.e., daily, few times a week, few times per month or less, and never); most frequently used public transportation, with an open answer; and public transportation means available in the city/town of residence, same as those means that subjects might consider are needed in their city, with an open answer format.

-

-

Reasons for using/not using public transportation: (i) Motives discouraging their demand for public transport services use, and features that the respondent considers must be improved to use this means of transport on a more frequent basis, following an open answer format; and (ii) Motives easing their use of public transportation, such as license withdrawal, fear of driving, environmental sustainability, health reasons, economic reasons, and no specific reason, measured on a symmetric scale ranging from 0 (total disagreement) to 10 (total agreement).

-

-

Assessment of public transportation: general and specific assessment of the following elements: comfort, cleanness, safety, punctuality, frequency, and accessibility, using a standard 0 (very poor) to 10 (excellent) scale. Assessment of different transport modes of the Dominican Republic, such as metro, public cars (informal taxis also called “pirate taxis”), motorcycle taxis, urban buses, and metropolitan buses (belonging to the OMSA metropolitan system), also measured on a scale ranging from 0 (very bad overall balance) to 10 (excellent balance).

-

-

Sociodemographic variables and driving data: basic questions about the individual, to favor their categorization and the differentiation of their perceptions from those with different possible socio-demographic profiles, namely: sex, age, habitat, working situation, do you usually drive? (“usually” as in 3 or more days per week).

2.3. Data processing

In order to describe and characterize Dominicans' movements on public transportation, as well as their opinions on the various factors involved and the motivations and needs that should be satisfied by this transportation mode in order for them to use it more, descriptive (frequency) analyses were carried out after careful data curation and coding.

For comparative purposes, robust Welch's tests were used to conduct comparative analyses based on categorical sociodemographic traits of Dominican people, such as sex (male/female) and age groups. Welch's tests are t-based and non-parametric calculations that have a number of benefits over parametric tests commonly employed in social science research, such as ANOVA, especially when variances are unequal (i.e., homoscedasticity is not achieved) and compared groups are disproportional in terms of one or more features.

Subsequently, a multiple linear regression analysis was also performed to identify the explanatory variables of the level of quality of public transport perceived by the participants. IBM SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences), version 26.0 (Armonk, NY, USA), was used for all descriptive statistical analyses, and SigmaPlot software, version 12.0, was used to plot all of the figures used in the research (Berkshire, UK).

2.4. Ethics

Prior to conducting the research, the study protocol was assessed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the INTRAS - University of Valencia, granting its accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (IRB approval number: HE0001251019). All participants gave their informed consent before participating in the study, after the research staff provided them with an explanation of the research objectives and all the previously mentioned considerations.

3. Results

The first descriptive outcome of this study corresponded to the overall quality assessment of public transportation as a suitable alternative for mobility, which was M = 6.70 (SD = 3.32) on a scale ranging between 0 (lower quality perceived) and 10 (higher quality perceived).

Regarding the frequency of use of public transportation among Dominicans, 21.8 % of them reported using at least one of the available means on a daily basis, 36.7 % a few times per week, and 30.3 % use it a few times per month or less; 11.1 % never use it.

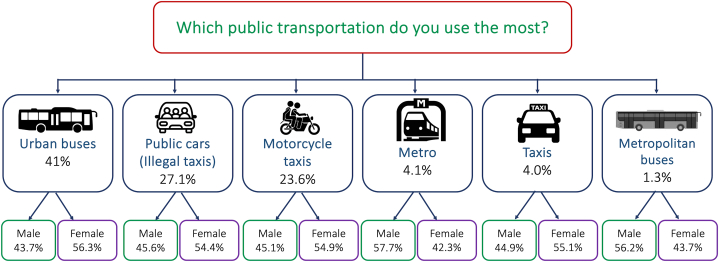

On the other hand, it is noticeable how least-regulated transportation means group most public transport users: the most used public transportation modes among Dominicans were (in descending order) urban bus (41 %), illegal/collective fixed-route taxis (public cars; 27.1 %), and motorcycle taxis (23.6 %), as it is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Use of different public transport means in the Dominican Republic.

Given that the evidence provided by the existing data (which, as aforementioned, is really scarce) does not address potential motives or constraints discouraging Dominicans from using public transportation, this was one of the key questions of this research. As a result, an important number of them do not really attribute any specific reason for it (22.6 %), which makes it hypothesizable that many motives (a “systemic failure”) could be simultaneously explaining this phenomenon. However, there are some key public transport-related features highlighted by Dominicans as “in need of improvement”, that could potentially enhance the attractiveness of public transport systems in the Dominican Republic: this is the case of comfort (22.3 %), vehicle status and maintenance (17.7 %), and trip safety (8.4 %). It is surprising how 8.7 % state they would prefer avoiding public transportation in no case, even if all these substantial improvements had already occurred.

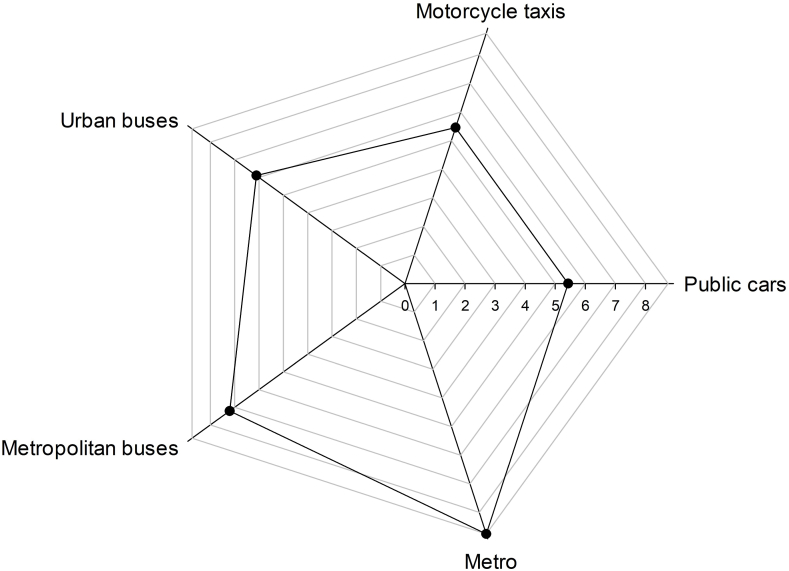

In order to make mode-based comparisons easier to interpret, the overall scores given to the different public transport means are graphically displayed in Fig. 3. The metro particularly stands out (M = 8.75; SD = 2.03), followed by OMSA buses (M = 7.21; SD = 2.65). The worst assessment goes to public cars (M = 5.43; SD = 3.54). The assessment of public cars (r2 = −0.068; p = 0.016) and motorcycle taxis (r2 = −0.078; p = 0.007) present a small and negative correlation to age. Nevertheless, there are no significant differences in the assessment of any transport mode based on users’ sex, habitat, working situation, and driving habits.

Fig. 3.

Overall (average) assessment of public transportation means in the Dominican Republic.

On the other hand, the public transport features with the highest assessments in public transportation are accessibility (M = 7.08; SD = 3.18), route frequency (M = 6.99; SD = 3.08), and punctuality (M = 6.42; SD = 3.39), as graphically shown in Fig. 4. Cleanness and comfort present significant differences depending on habitat, while accessibility and cleanness present differences depending on sex (Table 2). Likewise, a slight but positive correlation was found between perceived comfort and users’ age (r = 0.072; p < 0.010).

Fig. 4.

Study participants' assessment of six key public transport features, from lesser to greater values (0–10 scale).

Table 2.

Crossed public transportation features and sociodemographic variables.

| Variable | Feature | Category | n | Average | SD | Welch's test |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | df | Sig. | ||||||

| Sex | Accessibility | Male | 630 | 6.90 | 3.17 | 2.046 | 1,1258 | 0.041 |

| Female | 630 | 7.27 | 3.18 | |||||

| Cleanness | Male | 630 | 5.04 | 3.56 | −2.601 | 1,1248 | 0.009 | |

| Female | 630 | 5.80 | 3.72 | |||||

| Habitat | Comfort | Urban | 1029 | 5.01 | 3.56 | −2.233 | 1,1258 | 0.026 |

| Rural | 231 | 5.58 | 3.52 | |||||

| Cleanness | Urban | 1029 | 5.27 | 3.67 | −3.067 | 1,1258 | 0.002 | |

| Rural | 231 | 6.09 | 3.56 | |||||

The linear regression analysis showed the existence of a relationship between the variables studied and the perception of the general quality of public transportation (dependent variable), which is explained by equation Y = +11.874 + 3.946X1 + 1.854X2 + 1.811X3 + 5.109X4 + 4.210X5 – 1.499X6 + 2.744X7, Y being overall perceived quality; X1 is the assessment of accessibility; X2 is the assessment of the frequency; X3 is the assessment of punctuality; X4 is the assessment of security/safety; X5 is the assessment of comfort; X6 is the assessment of cleanliness X7 is the valuation of the economic cost.

The typed regression coefficients and their probability values are presented in Table 3 (see right columns). The fixed coefficient of determination (R square) was R2 = 0.224, being 22.4 %, the percentage in which the dependent variable is predictable using the independent variables included in the model.

Table 3.

Regression coefficients of the variables retained in the significant regression model.

| Variable | UCa | SEb | βc | Td | Sig.e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Constant) | 2.904 | 0.245 | 11.874 | <0.001 | |

| Accessibility | 0.133 | 0.034 | 0.127 | 3.946 | <0.001 |

| Route frecuency | 0.066 | 0.036 | 0.061 | 1.854 | 0.064 |

| Punctuality | 0.060 | 0.033 | 0.061 | 1.811 | 0.070 |

| Security/Safety | 0.174 | 0.034 | 0.181 | 5.109 | <0.001 |

| Comfort | 0.157 | 0.037 | 0.169 | 4.210 | <0.001 |

| Cleanness | −0.050 | 0.033 | −0.055 | −1.499 | 0.134 |

| Economic cost | 0.076 | 0.028 | 0.078 | 2.744 | 0.006 |

Notes.

UC=Unstandardized regression (path) coefficient.

SE = Standard Error.

β (Beta) = Standardized path coefficients.

T = Test statistic.

Sig. = Test significance level (p-value).

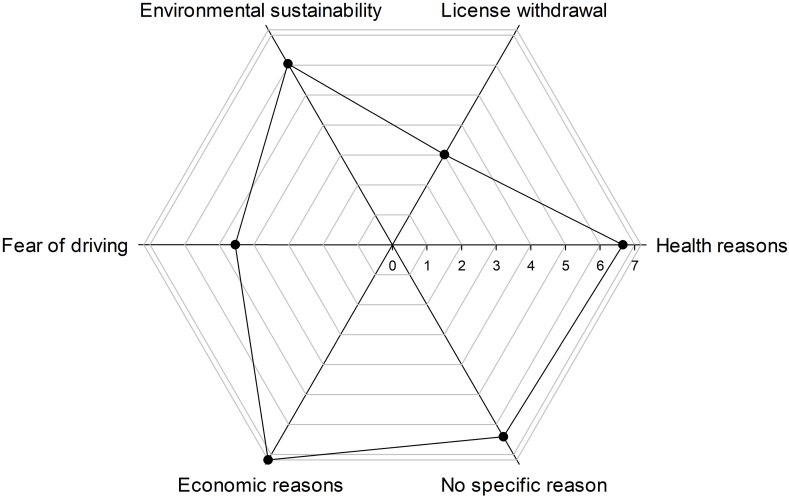

In addition to understanding the potential reasons that largely explain the considerably scarce use of public transportation in the Dominican Republic, it is important to know why users do, indeed, use public transportation, or in other words, to address the potential motivators driving people to use it. Economic reasons stand out (M = 7.18; SD = 3.11), while the fear of driving (M = 4.54; SD = 4.18) and the withdrawal of the driving license (M = 3.01; SD = 3.86) are, comparatively, less common reasons, as illustrated graphically in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Self-reported core reasons for using public transportation among Dominican citizens, from lesser to greater valued (0–10 scale).

Further, it is interesting to point out the significant differences found in the function of the analyzed sociodemographic characteristics, such as sex, habitat, and the fact of owning (or not) a vehicle. In brief, females give significantly higher scores than males due to health reasons and fear of driving. Regarding the habitat, inhabitants of urban zones score higher in economic and health-related issues, as well as for no specific reason, and people who do not usually drive score higher for no specific reason and fear of driving. On the other hand, they score significantly lower in license withdrawal as a reason for using public transportation which could be associated with the outstanding differences in the use of private vehicles, with males being those who drive the most, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Reported motives for using public transportation, according to key users’ sociodemographic variables.

| Variable | Stated reason | Category | n | Ma | SDb | Welch's test |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tc | dfd | Sig.e | ||||||

| Sex | Health issue | Male | 619 | 6.45 | 3.37 | −2.209 | 1,1232 | 0.027 |

| Female | 615 | 6.88 | 3.39 | |||||

| Fear of driving | Male | 616 | 3.88 | 3.97 | −5.689 | 1,1216 | 0.001 | |

| Female | 602 | 5.22 | 4.28 | |||||

| Habitat | Economic reason | Urban | 1018 | 7.38 | 3.03 | 4.685 | 1,1246 | 0.001 |

| Rural | 230 | 6.32 | 3.28 | |||||

| Health issue | Urban | 1010 | 6.77 | 3.36 | 2.310 | 1,1232 | 0.021 | |

| Rural | 224 | 6.19 | 3.48 | |||||

| No specific reason | Urban | 1003 | 6.53 | 3.35 | 2.680 | 1,1219 | 0.007 | |

| Rural | 218 | 5.85 | 3.43 | |||||

| Owns a vehicle? | No specific reason | Yes | 462 | 6.12 | 3.42 | −2.348 | 1,1219 | 0.019 |

| No | 759 | 6.58 | 3.33 | |||||

| Fear of driving | Yes | 467 | 3.59 | 3.95 | −6.364 | 1,1216 | 0.001 | |

| No | 751 | 5.13 | 4.21 | |||||

| License withdrawal | Yes | 439 | 3.42 | 3.90 | 2.864 | 1,1135 | 0.041 | |

| No | 698 | 2.75 | 3.80 | |||||

Notes.

M = Aritmethic mean.

SD = Standard Deviation.

T = Test statistic.

df = Degrees of Freedom (group 1, group 2).

Sig. = Test significance level (p-value).

Although to the date, there are no studies in this regard, some institutional documents suggest that another reason behind the low use of public transportation in the country could be that specific transport means aimed at this purpose are unequally represented in different territories (INTRANT, 2020). Accordingly, 82.1 % of participants consider that the urban bus availability is considerable, and 74.4 % believe motorcycle taxis are easy to find in their areas of residence. However, other transportation modes, such as metros (31.9 %) or taxis (38.8 %) are available only in very specific urban zones.

Notwithstanding, 37.5 % of Dominicans consider that their city/town of residence does not need more public transportation coverage. On the other hand, 20.2 % of participants consider more metro lines and metropolitan buses (10.2 %) are needed.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to analyze usage and perceived quality of public transportation means in the Dominican Republic, as well as to explore the most relevant features for Dominican citizens, aiming at finding possible solutions to enhance more efficient mobility and sustainability based on strengthening the public transport demand. In this regard, and besides the perceived quality reported by users, the appraisals on their desired improvements or expectations to make it a more attractive option were considered, as several empirical shreds of evidence point that daily transport choices have a direct impact on the quality of life [63,64]. In this sense, it could be hypothesized that efficient measures to improve both the offer and features of public transport supported by adequate information strategies (e.g., communication campaigns) would not only help to attract more potential users but also contribute to strengthening transport sustainability [65].

4.1. Use, disuse and key desired features of public transport in the Dominican Republic

Overall, the findings of this study show a low average use of public transportation in the Dominican Republic. The highest-rated public transportation modes were metro and metropolitan (OMSA) buses. In both cases, the service is carried out in very specific urban areas of the country, mainly in the city of Santo Domingo. Therefore, it is not random that “preferred” transport modes by Dominican citizens correspond to those implemented in higher-income areas, which at the same time correspond to urban locations [66]. This makes us reflect on previous studies problematizing that unequal transport system developments contribute to raising and deepening social gaps and life quality disparities [67]. At this point, the assessment given to the different features of public transport means becomes important. Accessibility and frequency positively stand out, with scores higher than safety, while cleanness and comfort remain the lowest valued features among Dominicans.

Nonetheless, this outcome is mainly related to the most used transport modes. In Santo Domingo, metros and metropolitan (OMSA) buses only move 10 % of the population that actually uses public transportation despite currently being the safest and most financially accessible modes [51]. Why is that? A matter of coverage or accessibility?

One potential explanation is that approximately 75 % of users of this transport mode need to perform an intermodal integration at one of the two ends of their trip. Thus, if passengers choose the metro, they must pay two fares; however, if they use public cars, they only have to pay one [68]. On the other hand, OMSA (metropolitan) buses cover the main routes of the city, but they cannot fulfil the demands of the main passenger concentration points or “dense spots” [69]. Therefore, it would be interesting to widen the network offered by metro and OMSA buses through a preliminary study on the population's most common movement patterns or establish a combined and intermodal transport system allowing Dominicans to perform their usual trips without paying higher prices.

Another issue worth mentioning is that most intermodal movements (trips) interchanging with metropolitan buses are performed by using public cars (illegally shared taxis), urban buses, and motorcycle taxis, which (being generally part of an informal economy) usually do not have established stops. Nevertheless, they would rather pick up passengers wherever they waited, thus leading to traffic jams [51]. One of the key attributable reasons for such an outcome is that these are, mostly, older vehicles with a lower capacity [52], which negatively influences the perceived cleanness and comfort. These two issues are better assessed in rural areas than in urban ones, which is determined by a higher number of people using these transport modes there. This is a phenomenon that repeats itself in most Latin American countries, where these service-related features are perceived as deficient, being affected by the agglomerations produced inside vehicles [70,71].

In this sense, policymakers and decision-makers in the transport sector could develop measures aimed at digitizing the different modes of public transport. The design of fixed routes and the establishment of mobile applications that allow users to coordinate their routes and intermodality easily could help reduce waiting and travel time, improving the public's perception of these modes of transport. In this same regard, other previous studies have shown that, technology can help collect real-time data to enable the use of data analysis and predictive models to anticipate problems and improve planning, the implementation of fleet management and electronic ticketing systems to collect accurate data, and the facilitation of real-time communication with users through mobile applications and social networks, helping to plan their trips [35,44].

4.2. Cleanness and bio-security after COVID-19: an emerging feature to strengthen?

One key limitation of this study is that data was collected just a couple of months before the first COVID-19 outbreak, which indeed increased the importance attributed to bio-security and the prevention of contagions in transport means that are usually crowded during weekdays. Therefore, regardless of the low valuation given by Dominicans to this key feature on this occasion, it is worth stating this as an essential issue for future user attraction dynamics during and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

In other recent empirical experiences carried out during the pandemic, improving the cleanness levels of public transportation has emerged as, perhaps, the most relevant issue for many users, even over trip safety and affordability [72,73]. In other words, as a generalized decrease in the use of public transportation has taken place for biosecurity reasons, an inverse logic might partly help rebuild public transport dynamics [74]. This also represents an economic issue since a lower demand implies a decrease in revenue, at the same time as more resources are needed for maintenance and disinfection [75].

4.3. Security in transport: a latent matter in Latin American systems

Similarly to other studies, the outcomes of this research highlight how important security issues become for users’ avoidance of public transport, especially among females, who remain the most vulnerable and affected group in Latin American transit environments [40]. Globally, different studies have shown that security and safety are the elements that influence the choice of a trip or transport mode the most [76].

In this case, it is remarkable how no differences were found depending on sex since this is a differential factor [77]. A survey carried out by the Thomson Reuters Foundation has established that Latin American cities are those with the most unsafe and dangerous public transportation for women, where 6 out of 10 females have suffered physical harassment [78], something that has been endorsed by some recent studies addressing the perception of users, especially for the case of females [40]. For this reason, it is necessary to keep exploring contextually based security measures that potentially help to face and prevent crime and victimization incidents in transport environments, including harassment in public transportation, which is usually underestimated or underreported in statistical figures [79].

Also, economic reasons stand out as to the reasons behind the choice of public transport [5,63]. As in most LMICs (low and middle-income countries), wealth distribution remains unequal in the Dominican Republic, and many individuals do not have a high enough income to afford buying and maintaining a private vehicle, which leads them to choose other transport modes for their movements in a forced way [39]. On the other hand, there are significant differences by sex in what concerns the “fear of driving” and the “license withdrawal”, which are determined by the few women who drive in the Dominican Republic [62,80].

Finally, it is convenient to highlight that more than one-third of Dominicans (precisely 37.5 % of them) do not believe that the incorporation of new public transport choices is necessary for their city. This is a very introductory but interesting fact worth further exploring. Yet, it could be initially hypothesized that the actual needs of users exceed the mere coverage and may refer rather to public transport planning, integration and scheduling through a system that can foster adequate mobility for citizens, as well as the environment's sustainability, leading to a better organization and structure in the country's transport system.

4.4. Recommendations on possible actions to be applied in the Dominican Republic

The pollution and road safety problems caused, among other factors, by the high number of motorized vehicles that travel daily in the Dominican Republic could be reduced if citizens opted to a greater extent to use collective means of transport [81]. Nonetheless, in view of the present study's results, several elements make it difficult for users to use public transport for their daily commute.

The responsible entities must be aware of the importance of improving the quality and perception of the service, especially in relation to the attributes that are worst valued by citizens [82]. In this way, user comfort and convenience must be improved through the modernization and improvement of the conditions of the public vehicle fleet, as well as the establishment of sufficient standards of cleanliness to guarantee adequate service. Establishing clear protocols for preventive and corrective maintenance of vehicles and stations is recommended to maintain a reliable and safe service [83].

Efforts should also be made to restructure the available transportation network. As previously mentioned, a significant portion of Dominicans do not consider implementing new public transport options necessary, given that there is already a sufficiently broad set of travel options. Yet, the design of routes and stops should be adapted to the needs of citizens [84]. Many of them opt for private vehicles because no route covers their entire journey. In some cases, it is required to use two or more public vehicles to complete the entire route. This occurs in three-quarters of public transport users, which is a waste of time and money that discourages the use of this mode of transport. Therefore, it is recommended that a study of the routes and routes most frequented by users be carried out, which will allow the optimization of public transportation systems, making them a much more efficient and attractive option for Dominicans. In relation to this point, it is also recommended to review and optimize schedules to ensure greater frequency and punctuality of service, including, to the extent possible, an investment in monitoring technologies and mobile applications to improve coordination and operational efficiency [85,86].

In addition, given the potential influence of social perception in changing travel patterns, awareness campaigns should be promoted to encourage public transport as a viable and sustainable option [87]. The communication strategy should be aimed at two objectives. On the one hand, to raise awareness of the individual and collective benefits of using public transport and other soft modes of travel [88]. Evidence indicates that in the Dominican Republic there is a distortion in the perception of the importance of problems such as road accidents or pollution, with no real perception of their seriousness and underestimation of their negative consequences [65,89]. In this way, the knowledge and acceptability of this transport option will be favored, providing information on how to use the service in an effective and safe manner [65].

4.5. Limitations of the study

The study has some limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. The data were collected before the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, there is evidence that recommendations to maintain social distance from other people have affected the commuting routines and transportation choices of citizens worldwide [90,91]. Therefore, it is a factor to be considered as perceptions and use of transport modes today may differ from the results obtained in the study. However, this circumstance also offers the possibility of replicating the research in the present in order to analyze the potential differences that may have occurred and the implications they may have on the development and planning of public transport in the Dominican Republic.

Moreover, this is a cross-sectional study, so it provides information only for the time period the data were collected, without following up on possible changes over time. Also, no specific questions have been addressed on the attributes or characteristics of the different modes of public transport. These are general questions that provide a fist approximation to the problem, but which could be supplemented in future research [92,93]. In this sense, and also considering the first limitation mentioned above, we emphasize the importance of carrying out future research to identify and explain the potential evolution in the use and perceptions of the means of transport analyzed.

Finally, a self-reported questionnaire has been used for data collection. As a result, social desirability bias may occur, thus influencing the participants' responses [94,95] despite reporting no right or wrong answers and guaranteeing the anonymity of the sample.

5. Conclusions

This study, which pioneers the study of public transport user’ perceptions in the Dominican Republic targets different issues, insights, and practical implications useful for the development of massive transport policies and practices, namely:

Although not the only constraints identified, public transportation in the Dominican Republic remains particularly challenging for users, especially regarding three key issues: comfort, vehicle conditions, and safety.

In areas where public transportation is closer to fulfilling these three features, such as the metro system and metropolitan buses, additional challenges persist, particularly concerning transport accessibility and intermodality. This includes the inability to seamlessly transition between different modes of transportation to complete a single trip.

At a practical level, considering insights from both this study and previous literature, a feasible short-term proposal involves incentivizing public transport usage through incremental enhancements, such as improved route planning and intermodal payment systems.

Moreover, promoting integrated public transport services and enhancing their attractiveness for citizens is expected to increase public transportation usage, thereby fostering safer, more efficient, and more sustainable mobility in the region.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Institute of Transit and Land Transportation (INTRANT) and its Permanent Observatory in Road Safety (OPSEVI; public agency of the Dominican Republic) - Grant number: 20170475. This work was supported by the research grant ACIF/2020/035 (MF) from “Generalitat Valenciana”. Funding entities did not contribute to the study design or data collection, analysis, and interpretation or writing of the manuscript.

Data availability statement

The data used in this study are available upon request to the corresponding author.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Francisco Alonso: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Project administration, Investigation, Conceptualization. Cristina Esteban: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Mireia Faus: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Sergio A. Useche: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:The corresponding author (Dr. Francisco Alonso) is an Associate Editor of the journal. This does not alter our adherence to the ethical policies of Heliyon. Further, the authors of this study declare the inexistence of competing interests.

Contributor Information

Francisco Alonso, Email: francisco.alonso@uv.es.

Cristina Esteban, Email: cristina.esteban@uv.es.

Mireia Faus, Email: mireia.faus@uv.es.

Sergio A. Useche, Email: sergio.useche@uv.es.

References

- 1.Bergman N., Schwanen T., Sovacool B.K. Imagined people, behaviour and future mobility: insights from visions of electric vehicles and car clubs in the United Kingdom. Transport Pol. 2017;59:165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2017.07.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shang J., Zheng Y., Tong W., Chang E., Yu Y. Inferring gas consumption and pollution emission of vehicles throughout a city”. Proc. ACM SIGKDD Int. 2014:1027–1036. doi: 10.1145/2623330.2623653. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhandarkar S. Vehicular pollution, their effect on human health and mitigation measures. Veh Eng. 2013;1(2):33–40. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pojani D., Stead D. Sustainable urban transport in the developing world: beyond megacities. Sustainability. 2015;7(6):7784–7805. doi: 10.3390/su7067784. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elshahat S., O'Rorke M., Adlakha D. Built environment correlates of physical activity in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2020;15(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0230454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Llamazares J., Useche S.A., Montoro L., Alonso F. Commuting accidents of Spanish professional drivers: when occupational risk exceeds the workplace. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2021;27(3):754–762. doi: 10.1080/10803548.2019.1619993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.González M. Los medios de transporte en la cuidad: Un análisis comparativo, Ecologistas en. Acción. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dell'Olio L., Ibeas A., Cecin P. The quality of service desired by public transport users. Transport Pol. 2011;18(1):217–227. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2010.08.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dell'Olio L., Ibeas A., Cecín P. Modelling user perception of bus transit quality. Transport Pol. 2010;17(6):388–397. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2010.04.006. 2010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang D.D. Assessing road transport sustainability by combining environmental impacts and safety concerns. Transp Res D Transp Environ. 2019;77:212–223. doi: 10.1016/j.trd.2019.10.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ye X., Pendyala R.M., Gottardi G. An exploration of the relationship between mode choice and complexity of trip chaining patterns. Transport Res B-Meth. 2007;41(1):96–113. doi: 10.1016/j.trb.2006.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dalton A.M., Jones A.P., Panter J.R., Ogilvie D. Neighbourhood, route and workplace-related environmental characteristics predict adults' mode of travel to work. PLoS One. 2013;8(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu X.H., Li Y.L. Studying of passenger transportation pattern choosing in transport corridor with thinking about time factor. Adv. Mater. Res. 2014;962:2541–2544. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jäppinen S., Toivonen T., Salonen M. Modelling the potential effect of shared bicycles on public transport travel times in Greater Helsinki: an open data approach. Appl. Geogr. 2013;43:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2013.05.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eboli L., Mazzulla G. Performance indicators for an objective measure of public transport service quality. 2012. http://hdl.handle.net/10077/6119

- 16.Jeong J., Lee J., Gim T.H.T. Travel mode choice as a representation of travel utility: a multilevel approach reflecting the hierarchical structure of trip, individual, and neighborhood characteristics. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2022;101(3):745–765. doi: 10.1111/pirs.12665. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eluru N., Chakour V., El-Geneidy A.M. Travel mode choice and transit route choice behavior in Montreal: insights from McGill University members commute patterns. Public Transp. 2012;4:129–149. doi: 10.1007/s12469-012-0056-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chakrabarti S. How can public transit get people out of their cars? An analysis of transit mode choice for commute trips in Los Angeles. Transport Pol. 2017;54:80–89. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2016.11.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meurer J., Stein M., Randall D., Rohde M., Wulf V. Proc SIGCHI Conf Hum Factor Comput Syst. 2014. Social dependency and mobile autonomy: supporting older adults' mobility with ridesharing ict; pp. 1923–1932. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoh A., Iseki H., Smart M., Taylor B.D. Hate to wait: effects of wait time on public transit travelers' perceptions. Transport. Res. Rec. 2011;2216(1):116–124. doi: 10.3141/2216-13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nordfjærn T., Rundmo T. Transport risk evaluations associated with past exposure to adverse security events in public transport. Transp. Res. F: Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2018;53:14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.trf.2017.12.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Useche S.A., Colomer N., Alonso F., Faus M. Invasion of privacy or structural violence? Harassment against women in public transport environments: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2024;19(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0296830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chowdhury S., Van Wee B. Examining women's perception of safety during waiting times at public transport terminals. Transport Pol. 2020;94:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2020.05.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Das S., Boruah A., Banerjee A., Raoniar R., Nama S., Maurya A.K. Impact of COVID-19: a radical modal shift from public to private transport mode. Transport Pol. 2021;109:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2021.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Q., Liu Y., Zhang C., An Z., Zhao P. Elderly mobility during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative exploration in Kunming, China. J. Transport Geogr. 2021;96 doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2021.103176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gutiérrez A., Miravet D., Domènech A. COVID-19 and urban public transport services: emerging challenges and research agenda. Cities & Health. 2021;5(sup1):S177–S180. doi: 10.3390/s21196574. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiao J., Azimian A. Exploring the factors affecting travel behaviors during the second phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Transp. Lett. 2021;13(5–6):331–343. doi: 10.1080/19427867.2021.1904736. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beck M.J., Hensher D.A., Wei E. Slowly coming out of COVID-19 restrictions in Australia: implications for working from home and commuting trips by car and public transport. Transp. Geogr. 2020;88 doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2020.102846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johansson M.V., Heldt T., Johansson P. The effects of attitudes and personality traits on mode choice. Transp. Res. A Policy Pract. 2006;40(6):507–525. doi: 10.1016/j.tra.2005.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klöckner C.A., Friedrichsmeier T. A multilevel approach to travel mode choice–How person characteristics and situation specific aspects determine car use in a student sample. Transp. Res. F: Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2011;14(4):261–277. doi: 10.1016/j.trf.2011.01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beirão G., Cabral J.S. Understanding attitudes towards public transport and private car: a qualitative study. Transport Pol. 2007;14(6):478–489. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2007.04.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Núñez F.M., Freire C., Vayas T. Sondeo de opinión ciudadana a los usuarios de transporte público en el cantón Ambato. Bol Coyuntura. 2018;(16):11–15. ISSN: 2600-5727. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nazif-Munoz J.I., Batomen B., Nandi A. Does ridesharing affect road safety? The introduction of Moto-Uber and other factors in the Dominican Republic. Res. Glob. 2022;4 doi: 10.1016/j.resglo.2021.100077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vasconcellos E.A. Routledge; 2014. Urban Transport Environment and Equity: the Case for Developing Countries. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alonso F., Faus M., Cendales B., Useche S.A. Citizens' perceptions in relation to transport systems and infrastructures: a nationwide study in the Dominican Republic. Infrastructures. 2021;6(11):153. doi: 10.3390/infrastructures6110153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chowdhury S., Ceder A.A. Users' willingness to ride an integrated public-transport service: a literature review. Transport Pol. 2016;48:183–195. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2016.03.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bocarejo J.P., Oviedo D.R. Transport accessibility and social inequities: a tool for identification of mobility needs and evaluation of transport investments. 2012;24:142–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2011.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Navarrete F.J., de Dios Ortúzar J. Subjective valuation of the transit transfer experience: The case of Santiago de Chile. Transport Pol. 2013;25:138–147. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2012.10.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hernández D. Transporte público, bienestar y desigualdad: cobertura y capacidad de pago en la ciudad de Montevideo. Rev. CEPAL. 2017;122,:166–184. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Orozco-Fontalvo M., Soto J., Arévalo A., Oviedo-Trespalacios O. Women's perceived risk of sexual harassment in a Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system: the case of Barranquilla, Colombia. J. Transport Health. 2019;14 doi: 10.1016/j.jth.2019.100598. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parras M.A., Gómez É.L. Tiempo de viaje en transporte público. Aproximación conceptual y metodológica para su medición en la ciudad de Resistencia. Revista Transp. Terr. 2015;(13):66–79. doi: 10.34096/rtt.i13.1877. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alonso F., Faus M., Tormo M.T., Useche S.A. Could technology and intelligent transport systems help improve mobility in an emerging country? Challenges, opportunities, gaps and other evidence from the caribbean. Appl. Sci. 2022;12(9):4759. doi: 10.3390/app12094759. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nesheli M.M., Ceder A.A., Estines S. Public transport user's perception and decision assessment using tactic-based guidelines. Transport Pol. 2016;49:125–136. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2016.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grujičić D., Ivanović I., Jović J., Đorić V. Customer perception of service quality in public transport. Transp. 2014;29(3):285–295. doi: 10.3846/16484142.2014.951685. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chowdhury S., Hadas Y., Gonzalez V.A., Schot B. Public transport users' and policy makers' perceptions of integrated public transport systems. Transport Pol. 2018;61:75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2017.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.PAHO . Organización Panamericana de la Salud. 2020. Plan Estratégico de la Organización Panamericana de la Salud (2020-2025) [Google Scholar]

- 47.Musa M.F., Hassan S.A., Mashros N. The impact of roadway conditions towards accident severity on federal roads in Malaysia. PLoS One. 2020;15(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0235564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nazif J.I., Pérez G. 2018. Revisión del desempeño de la seguridad vial en la República Dominicana. [Google Scholar]

- 49.DGII. Boletín Estadístico . 2022. Parque Vehicuar 2022; Dirección General de Impuestos Internos: Santo Domingo, República Dominicana. [Google Scholar]

- 50.INTRANT (Instituto Nacional de Tránsito y Transporte Terrestre) Santo Domingo; 2019. National Mobility Survey of the Dominican Republic, Results REPORT 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 51.González P.D. Santo Domingo; 2015. Propuesta para la mejora del transporte público en el Distrito Nacional. PhD diss., University of Cartagena. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Santana E.A., Marte J.C. 2017. Propuesta estratégica para la mejora en la calidad del servicio de transporte público: caso Transporte Expreso Tarea, ruta Santo Domingo-Bonao, República Dominicana. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Headrick W.C., Piña C.A., Piña S.S., Roa C.R. 2021. Oficina Metropolitana De Autobuses (OMSA) [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alonso F., Faus M., Fernández C., Useche S.A. “Where have i heard it?” Assessing the recall of traffic safety campaigns in the Dominican Republic. Energies. 2021;14(18):5792. doi: 10.3390/en14185792. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Faus M., Alonso F., Javadinejad A., Useche S.A. Are social networks effective in promoting healthy behaviors? A systematic review of evaluations of public health campaigns broadcast on Twitter. Front. Public Health. 2022;10 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1045645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brandao R., Diez-Roux E., Taddia A.P., De la Peña Mendoza S.M., De la Peña E. Inter-American Development Bank; 2013. Diagnóstico de seguridad vial en América Latina y El Caribe: 2005-2009. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cruz I.S., Katz-Gerro T. Urban public transport companies and strategies to promote sustainable consumption practices. J. Clean. Prod. 2016;123:28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.12.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ramos S., Vicente P., Passos A.M., Costa P., Reis E. Perceptions of the public transport service as a barrier to the adoption of public transport: a qualitative study. Soc. Sci. 2019;8(5):150. doi: 10.3390/socsci8050150. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Friman M., Lättman K., Olsson L.E. Public transport quality, safety, and perceived accessibility. Sustainability. 2020;12(9):3563. doi: 10.3390/su12093563. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Van Lierop D., Badami M.G., El-Geneidy A.M. What influences satisfaction and loyalty in public transport? A review of the literature. Transport Rev. 2018;38(1):52–72. doi: 10.1080/01441647.2017.1298683. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.National Statistics Office . Santo Domingo: Government of the Dominican Republic; 2021. Data and Statistics.https://www.one.gob.do/datos-y-estadisticas/ Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 62.INTRANT (Instituto Nacional de Tránsito y Transporte Terrestre) Santo Domingo; 2020. National Mobility Survey of the Dominican Republic. Results REPORT 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang X., Rodríguez D.A., Sarmiento O.L., Guaje O. Commute patterns and depression: evidence from eleven Latin American cities. J. Transport Health. 2019;14 doi: 10.1016/j.jth.2019.100607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lee R.J., Sener I.N. Transportation planning and quality of life: where do they intersect? Transport Pol. 2016;48:146–155. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Faus M., Alonso F., Fernández C., Useche S.A. Are traffic announcements really effective? A systematic review of evaluations of crash-prevention communication campaigns. Saf. Now. 2021;7(4):66. doi: 10.3390/safety7040066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Muro-Rodríguez A.I., Perez-Jiménez I.R., Gutiérrez-Broncano S. Consumer behavior in the choice of mode of transport: a case study in the Toledo-Madrid corridor. Front. Psychol. 2017;8:1011. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Locatelli S.M., Sharp L.K., Syed S.T., Bhansari S., Gerber B.S. Measuring health-related transportation barriers in urban settings. J. Appl. Meas. 2017;18(2):178. PMID: 28961153; PMCID: PMC5704937. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dorrejo E., Negrín K., Pérez C. 2007. El sistema de transporte colectivo en la articulación del gran Santo Domingo. Cie soc. ISSN: 0378-7680. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Montañez M.R. Un nuevo modelo de transporte para el gran Santo Domingo. Cie soc. 2016;41(2):337–359. ISSN: 0378-7680. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cunha Linke C., Maciente Rocha J.P., Alcalá A., Palacios A., Suárez M., Gómez M., Pardo C. Transp des Am Lat. 2018:2. http://scioteca.caf.com/handle/123456789/1348 [Google Scholar]

- 71.Oscar V.E.G.A., Rivera-Rodríguez H.A., Malaver N. Contrastación entre expectativas y percepción de la calidad de servicio del sistema de transporte público de autobuses en Bogotá. Rev Espacios. 2017;38(43) ISSN: 0798 1015. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shen J., Duan H., Zhang B., Wang J., Ji J.S., Wang J.…Shi X. Prevention and control of COVID-19 in public transportation: experience from China. Environ. Pollut. 2020;266 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wong Y. To limit coronavirus risks on public transport, here’s what we can learn from efforts overseas. The Conversation. 2020 https://theconversation.com/to-limit-coronavirus-risk-on-public-transport-heres-what-we-can-learn-from-efforts-overseas-133764 [Google Scholar]

- 74.Musselwhite C., Avineri E., Susilo Y. Editorial JTH 16–The Coronavirus Disease COVID-19 and implications for transport and health. J. Transport Health. 2020;16 doi: 10.1016/j.jth.2020.100853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tirachini A., Cats O. COVID-19 and public transportation: current assessment, prospects, and research needs. J Public Trans. 2020;22(1):1–21. doi: 10.5038/2375-0901.22.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Galiani S., Jaitman L. 2016. El transporte público desde una perspectiva de género: Percepción de inseguridad y victimización en Asunción y Lima. Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo, División de Capacidad Institucional del Estado, División de Transporte. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Falú A. La fuerza estigmatizadora del acoso sexual: violencias en el transporte público. Vivienda Ciudad. 2017;(4):205–209. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Boros C. Fundación Thomson Reuters América Latina. 2014. Sondeo Seguridad Transporte en América Latina. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rainero L. Espacios públicos. Convivencia y seguridad ciudadana.¿ Dónde están seguras las mujeres? Vivienda Ciudad. 2014;(1):88–98. [Google Scholar]

- 80.DGII (Dirección General de Impuestos Internos) República Dominicana. 2020. Boletín estadístico: parque vehicular 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ibraeva A., de Sousa J.F. Marketing of public transport and public transport information provision. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014;162:121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.12.192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bamberg S. Is a stage model a useful approach to explain car drivers' willingness to use public transportation? J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2007;37(8):1757–1783. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2007.00236.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shen J., Duan H., Zhang B., Wang J., Ji J.S., Wang J.…Shi X. Prevention and control of COVID-19 in public transportation: experience from China. Environ. Pollut. 2020;266 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Grison E., Gyselinck V., Burkhardt J.M. Exploring factors related to users' experience of public transport route choice: influence of context and users profiles. Cognit. Technol. Work. 2016;18:287–301. doi: 10.1007/s10111-015-0359-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Siuhi S., Mwakalonge J. Opportunities and challenges of smart mobile applications in transportation. J. Traffic Transport. Eng. 2016;3(6):582–592. doi: 10.1016/j.jtte.2016.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Casquero D., Monzon A., García M., Martinez O. Key elements of mobility apps for improving urban travel patterns: a literature review. Future Transp. 2022;2(1):1–23. doi: 10.3390/futuretransp2010001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Alonso F., Faus M., Esteban C., Useche S.A. Who wants to change their transport habits to help reduce air pollution? A nationwide study in the Caribbean. J. Transport Health. 2023;33 doi: 10.1016/j.jth.2023.101703. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Magginas V., Karatsoli M., Adamos G., Nathanail E. Data Analytics: Paving the Way to Sustainable Urban Mobility: Proceedings of 4th Conference on Sustainable Urban Mobility (CSUM2018), 24-25 May, Skiathos Island, Greece. Springer International Publishing; 2019. Campaigns and awareness-raising strategies on sustainable urban mobility; pp. 264–271. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Alonso F., Faus M., Useche S.A. Far from reality, or somehow accurate? Social beliefs and perceptions about traffic crashes in the Dominican Republic. PLoS One. 2023;18(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0282601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Koehl A. Urban transport and COVID-19: challenges and prospects in low-and middle-income countries. Cities Health. 2021;5(sup1):S185–S190. doi: 10.1080/23748834.2020.1791410. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jenelius E., Cebecauer M. Impacts of COVID-19 on public transport ridership in Sweden: analysis of ticket validations, sales and passenger counts. Transp Res Pespectives. 2020;8 doi: 10.1016/j.trip.2020.100242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Peña M.V. 2017. Marco legal e institucional para el desarrollo del sector transporte de la República Dominicana (Doctoral dissertation, Universidad de León) [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ge J., Shi W., Wang X. Policy agenda for sustainable intermodal transport in China: an application of the multiple streams framework. Sustainability. 2020;12(9):3915. doi: 10.3390/su12093915. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Domínguez Espinosa A.D.C., Aguilera Mijares S., Acosta Canales T.T., Navarro Contreras G., Ruiz Paniagua Z. La deseabilidad social revalorada: más que una distorsión, una necesidad de aprobación social. Acta inv psicol. 2012;2(3):808–824. [Google Scholar]

- 95.La Paix Puello L. 2018. Recogida de datos y modelización de la demanda de transporte en la República Dominicana. Cie ing aplic. ISSN: 2613-876X. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are available upon request to the corresponding author.