Reducing “the rate of maternal mortality by 75% by 2015” is one of the development targets that has been endorsed at numerous international meetings.1 This target was selected because maternal ill health is the largest contributor to the disease burden affecting women in developing countries; because the lifetime risk of maternal death is much greater in the poorest countries than in the richest (1 in 12 for women in east Africa compared with 1 in 4000 in northern Europe); and because interventions are cost effective (costing £2 ($3) per woman and £153 ($230) per death averted).2–5

Summary points

Reducing maternal mortality in developing countries is an international priority

Preventing maternal deaths requires a functioning health system

Sector-wide approaches allow donors to support improvements in health systems

Sector-wide approaches offer the opportunity to make a sustainable impact on maternal mortality

Improvements in maternal health can be used to measure the performance of sector-wide approaches

Preventing maternal deaths: what works?

The technical interventions needed to prevent maternal deaths are well understood.6 Traditional maternal and child health interventions, such as providing antenatal care and training traditional birth attendants, have failed.2,7 The availability, accessibility, use, and quality of essential obstetric care for life threatening conditions, including complications after abortion, need to be improved (box).2,6,7 What is less clear is how an environment can be created to enable interventions to be made in settings with few resources.8

Causes of maternal deaths

Severe bleeding 25%

Indirect causes including anaemia, malaria, 20% heart disease

Infection 15%

Unsafe abortion 13%

Eclampsia 12%

Obstructed labour 8%

Other direct causes including ectopic pregnancy, 8% embolism, or complications of anaesthesia

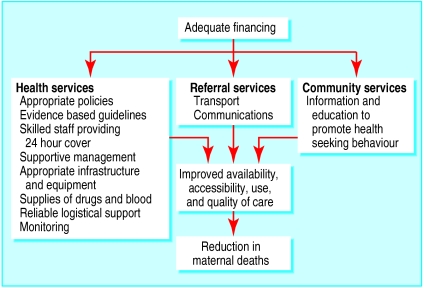

Creating a functioning health system is the most obvious means of providing this type of environment. Most of the resources needed to improve essential obstetric care exist as integral parts of district health systems, even if some of the parts do not function well or need updating (fig 1). In a functioning district health system the availability, accessibility, use, and quality of essential obstetric care are expected to be high and maternal mortality is expected to be low. Some developing countries, such as China, Sri Lanka, and Malaysia, have reduced maternal mortality dramatically after improving the coverage and quality of their health services.8 Conversely in Zimbabwe the progressive erosion of the general standard of health services has been associated with rising maternal mortality.9 Maternal mortality has been proposed for use as an indicator of accessible and functional health services.10

Components of essential obstetric care

There should be:

Parenteral antibiotics, oxytocics, and anticonvulsants available

Facilities for manual removal of the placenta if necessary

Facilities for removal of retained products of conception if necessary

Assisted vaginal delivery (for example, using vacuum extraction) available

Facilities for blood transfusion

Facilities for caesarean section

Figure 1.

Resources needed to improve essential obstetric care

The launch of the Safe Motherhood Initiative by the Interagency Group on Safe Motherhood offers real opportunities for countries to make progress in providing effective health care especially if the initiative is linked to financial support mechanisms designed to improve the quality of the health sector as a whole.

How can activities to improve maternal health be supported?

Governments and donors have three main options for funding large scale activities aimed at improving maternal health: they can take a vertical project approach, a reproductive health programme approach, or a sector-wide approach (table). All three approaches present opportunities and risks.

Vertical maternal health projects

Vertical funding, especially of pilot projects, has several advantages. The logic of doing a few things well rather than many things badly is undeniable. Visible short term gains from intensive, focused activity show that improvements are possible and create positive attitudes towards improving services on a wider scale. Also, the creation of visible links between resources from donors and improvements in service encourages continued funding by donors. However, the litany of adverse effects of vertical financing is familiar to anyone who has worked at district level in a developing country. For example, providers often must complete multiple forms each month, some vehicles can only be used for transporting people with specific health problems, or condoms can only be distributed to prevent AIDS. Similarly, sustainability is frequently mentioned in policy documents about vertical projects, but in reality most government personnel and, more importantly, project staff are focused on the immediate performance of the project and may be reluctant to sacrifice immediate results for longer term gains. Thus, improvements resulting from vertical approaches may raise expectations while undermining the overall system.

Despite the drawbacks of vertical funding, many safe motherhood projects initiated in the past few years, which include British funded projects in Malawi and Nepal and projects funded by the United States in Indonesia, Guatemala, Morocco, and Egypt, exhibit a number of vertical design features. However, the safe motherhood concept will almost certainly never attract the funds required to set up completely vertical and parallel health systems, and indeed this has never been proposed. Thus, despite having vertical design features these projects typically rely on government health infrastructure and health personnel and have been hampered by sector-wide deficiencies including the poor performance of health staff which is associated with low pay and adverse working conditions.

Reproductive health programmes

The integrated funding of reproductive health programmes is often proposed as an alternative to the vertical funding of essential reproductive health activities. The central role of safe motherhood programmes within such reproductive health programmes was supported within the plan of action agreed at the 1994 international conference on population and development.11 However, the concept of reproductive health covers a wide range of issues, and the strong focus needed to improve maternity care may be lost in an integrated approach, especially when it is expressed in the language of primary health care.12 This loss of focus may be exacerbated by the fact that many agencies and groups involved in reproductive health care originally worked in family planning, and strategies for providing family planning services (for example subsidising the marketing of contraceptives) differ from those needed for providing essential obstetric care. Another emerging issue for donors is whether the concept of reproductive health can be strengthened without creating a vast vertically funded structure, albeit one that replaces several others.

Health programmes supported by the United Nations Population Fund typically adopt a reproductive health strategy. In some countries, such as Morocco, Mozambique, and Bangladesh, reproductive health programmes include a large essential obstetric care component. However, this is not always the case. In a reproductive health initiative supported by the United Nations Population Fund and the European Commission, which involves seven Asian countries, only 11 out of 40 projects mention any aspect of maternal health.13

Sector-wide approaches

Sector-wide approaches and other comprehensive frameworks were developed and applied to health care because they were thought to offer better prospects for success than piecemeal projects financed separately.14 They also have the potential to eliminate the duplication of activities14 and the distortions created within health systems by vertically funded, single issue programmes. Sector-wide approaches present a good opportunity for donors to support policies that will lead to the development of effective and efficient health systems.

Opportunities for promoting safe motherhood programmes

There seem to be no donor supported, sector-wide approaches that have emphasised safe motherhood as an indicator condition or goal. In contrast, health sector assistance strategies have been known to omit maternal mortality as an issue, even in countries where there are serious maternal health problems.10 Nevertheless, there are two main reasons for promoting safe motherhood through sector-wide approaches.

Firstly, donors invest considerable resources in both health services and the health sector generally. In 1990, it was estimated that 46% of external assistance to the health and population sectors was allocated to general health services (of which 5% was spent on hospitals) and 46% to reproductive health. Within reproductive health care, the proportion spent on vertical safe motherhood programmes was 0.2%; 41.9% was spent on family planning and population issues.15 For this reason, it may make better tactical sense for maternal health programmes to be linked with and tap into the greater funds available for health sector development rather than to compete with a large, articulate constituency for family planning funds.

Secondly, the dependence of initiatives for promoting safe motherhood on health systems means that health sector reforms have huge implications for these programmes. For example, the introduction of user fees has been associated with a reduced use of maternity care in some situations (for example, in Kenya and Zimbabwe) and an increase in others (for example, in Cambodia).10,16 Many proposed solutions, such as insurance schemes, fail to cover precisely those interventions that could save lives. For example, in Yunnan, China, an insurance scheme covered antenatal and postnatal care but not delivery.17 Linking safe motherhood programmes to sector-wide approaches at an early stage may mean that the implications of proposed solutions to providing better care can be tested and considered.

Of course there are several areas of concern for advocates of safe motherhood. A reliance on sector-wide approaches might mean that crucial areas of care are not supported. Donor agencies that support sector-wide approaches need to be aware that some key activities that are essential to improving maternity care might not be covered by broad approaches to funding. These include reviewing and updating obstetric protocols and curriculums; training trainers in specific techniques, such as manual vacuum aspiration; updating maternity recording systems; and initiating obstetric audits and other quality control measures. It is also important to support the training and use of midwives with a view towards increasing the availability of skilled personnel, particularly if the goal of having skilled attendants present at all births is adopted.18 These and related activities need focused technical assistance and funding.

Benefits of focusing on safe motherhood initiatives

Advocates of sector-wide approaches may be concerned that linking resources to indicators associated with safe motherhood is a covert tactic in a move towards verticalisation. In reality it can be seen as an opportunity to test the robustness of sector-wide approaches against a few agreed health priorities. The link need not focus on safe motherhood alone but could be broadened to include clinical conditions, such as tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS, and malaria, that have been recognised as global priorities.19 Linking safe motherhood to sector-wide approaches can help counter donors' fears that they are being asked to contribute to a bottomless pit within the health sector and can promote a process of evaluation that measures outcomes, something which has so far been lacking.20

Conclusion

In the long term, sustaining affordable improvements in safe motherhood depends on improving the functioning of health systems as a whole. Gains made in countries such as Malaysia and Sri Lanka were achieved by making maternity care a priority that guided changes in health services. Efforts to achieve similar gains in other developing countries need pragmatic support. Sector-wide approaches and other routes to health system reform, intended to offer alternatives to failing public systems and provide improved health services in a spirit of equity, are compatible with a focus on maternal health services. If performance, as measured by indicators of safe motherhood as well as other essential health indicators, was a condition of funding, the placing of maternal health services at the centre of the sector could be assured. In political environments in which partnerships between donors and governments are likely to succeed, sector-wide approaches present a unique opportunity for advocates of safe motherhood to make a sustainable impact on maternal mortality.

Table.

Approaches to funding improvements in maternal health

| Vertical project | Reproductive health programme | Sector-wide approach | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technical scope | Focuses exclusively on maternal health | Focuses on a wide range of reproductive health issues including family planning, adolescent health, reproductive rights, sexually transmitted diseases, and maternal health | Focuses on all essential components of health service including maternal health |

| Management | Project managed separately within ministry of health | Programme managed separately within ministry of health | Management of integrated services decentralised to district level |

| Personnel | Project funds key individuals to manage activities | Programme funds key individuals to manage activities | Changes in remuneration made as part of financial planning and human resources development |

| Training | Courses centrally planned and funded | Courses centrally planned and funded | Maternal health topics covered by in-service training plans for district |

| Supplies and monitoring | Separate systems for logistics and information | Separate systems for logistics and information | Integrated logistics and health information systems |

| Transport | Vehicles only used by project | Vehicles only used by programme | Vehicles used for variety of purposes |

Figure.

Moroccan women benefit from reproductive health programmes that have a large component of essential obstetric care

Footnotes

Funding: EG works for an organisation that receives support from the UK Department for International Development, the European Commission, and the Averting Maternal Death and Disability Program at Columbia University in New York; OC is supported through a programme funded by the UK Department for International Development.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Department for International Development. Better health for poor people: strategies for achieving the international development targets. London: DFID; 2000. p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inter-Agency Group for Safe Motherhood. Every pregnancy faces risks: ensure skilled attendance at delivery. In: Starrs A, editor. The safe motherhood action agenda: priorities for the next decade. Report on the safe motherhood technical consultation, 18-23 October, 1997, Colombo, Sri Lanka. New York: Family Care International; 1998. pp. 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Inter-Agency Group for Safe Motherhood. The safe motherhood action agenda: priorities for the next decade. Report on the safe motherhood technical consultation, 18-23 October, 1997, Colombo, Sri Lanka. New York: Family Care International; 1998. pp. 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jowett M. Safe motherhood interventions in low-income countries: an economic justification and evidence of cost effectiveness. Health Policy. 2000;53:201–228. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(00)00089-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization and United Nations Children's Fund. Revised 1990 estimates of maternal mortality. A new approach by WHO and UNICEF. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1996. . (WHO/FRH/MSM/96.11, UNICEF/PLN/96.1.) [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1994. Mother-baby package: implementing safe motherhood in countries. . (WHO/FHE/MSM/94.11.) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maine D. Safe motherhood programs: options and issues. New York: Center for Population and Family Health, Columbia University; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koblinsky MA, Campbell O, Heichelheim J. Organizing delivery care: what works for safe motherhood? Bull World Health Organ. 1999;77:399–406. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Central Statistical Office (Zimbabwe); Macro International. Zimbabwe demographic and health survey, 1994. Calverton, MD: Macro International; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Bank. Safe motherhood and the World Bank: lessons from 10 years of experience. Washington, DC: World Bank; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Family Care International. Action for the 21st century: reproductive health and rights for all. Summary report of recommended actions on reproductive health and rights of the Cairo International Conference on Population and Development Programme of Action, September 1994. New York: Family Care International; 1994. pp. 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lush L, Campbell O. International cooperation for reproductive health: too much ideology? In: McKee M, Farmer P, eds. International cooperation in health. Oxford: Oxford University Press (in press).

- 13.European Commission, United Nations Population Fund. EC/UNFPA initiative for reproductive health in Asia. http://www.asia-initiative.org/projects.html (accessed 9 November 2000).

- 14.Cassels A. A guide to sector-wide approaches for health development. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1997. . (WHO/ARA/97.) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zeitlin J, Govindaraj R, Chen LC. Financing reproductive and sexual health services. In: Sen G, Germain A, Chen LC, editors. Population policies reconsidered: health, empowerment, and rights. Boston: Harvard University Press; 1994. pp. 233–248. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graham W, Murray S. A question of survival? Review of safe motherhood in Kenya. Nairobi: Ministry of Health; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaufman J, Kaining Z, Jing F. Reproductive health financing, service availability and needs in rural China. Institute of Development Studies Bulletin. 1997;28:61–65. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campbell O. Measuring progress in safe motherhood programmes: uses and limitations of health outcome indicators. In: Berer M, Ravindran TKS, editors. Safe motherhood initiatives: critical issues. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 1999. pp. 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Bank. World development report: investing in health. Washington, DC: World Bank; 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garner P, Flores W, Tang S. Sector-wide approaches in developing countries. BMJ. 2000;321:129–130. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7254.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]