Highlights

-

•

Connectome gradient dysfunction at voxel level and network level in children with BECTS.

-

•

The gradient score of the left PCG is significantly associated with the VIQ.

-

•

The principal gradient map of the children with BECTS significantly predicted their VIQ.

Keywords: Connectome gradient, Hierarchy, Functional connectivity, Benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes, Resting-state fMRI

Abstract

Objective

Benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (BECTS) affects brain network hierarchy and cognitive function; however, it remains unclear how hierarchical change affects cognition in patients with BECTS. A major aim of this study was to examine changes in the macro-network function hierarchy in BECTS and its potential contribution to cognitive function.

Methods

Overall, the study included 50 children with BECTS and 69 healthy controls. Connectome gradient analysis was used to determine the brain network hierarchy of each group. By comparing gradient scores at each voxel level and network between groups, we assessed changes in whole-brain voxel-level and network hierarchy. Functional connectivity was used to detect the functional reorganization of epilepsy caused by these abnormal brain regions based on these aberrant gradients. Lastly, we explored the relationships between the change gradient and functional connectivity values and clinical variables and further predicted the cognitive function associated with BECTS gradient changes.

Results

In children with BECTS, the gradient was extended at different network and voxel levels. The gradient scores frontoparietal network was increased in the principal gradient of patients with BECTS. The left precentral gyrus (PCG) and right angular gyrus gradient scores were significantly increased in the principal gradient of children with BECTS. Moreover, in regions of the brain with abnormal principal gradients, functional connectivity was disrupted. The left PCG gradient score of children with BECTS was correlated with the verbal intelligence quotient (VIQ), and the disruption of functional connectivity in brain regions with abnormal principal gradients was closely related to cognitive function. VIQ was significantly predicted by the principal gradient map of patients.

Significance

The results indicate connectome gradient disruption in children with BECTS and its relationship to cognitive function, thereby increasing our understanding of the functional connectome hierarchy and providing potential biomarkers for cognitive function of children with BECTS.

1. Introduction

Benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (BECTS) is a most common focal epilepsy, affecting 8–23% of children with epilepsy (GBD 2016 Neurology Collaborators, 2019, McGinnity et al., 2017). Several recent studies have found that children with BECTS have cognitive dysfunction, which is mainly manifested in language processing, executive function, and memory deficits (Overvliet et al., 2013, Yan et al., 2017, Wickens et al., 2017), and has a greater impact on children’s learning and life. Additionally, some patients need to take medicines for life, placing a heavy economic burden on their families and society. However, the etiology of BECTS remains unknown. Therefore, it is essential to understand the brain mechanisms underlying functional impairments in children and identify the corresponding objective biomarkers.

MRI is a noninvasive and comprehensive detection tool, it is useful for studying spontaneous neural activity of the brain at rest and to evaluate functional connections and networks of various brain regions. It has been widely used in research on neuropsychiatric disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment (Ibrahim et al., 2021), psychosis (Collin et al., 2020), epilepsy (Chen et al., 2022). In patients with BECTS, discharge sites are mainly located in the center of the brain sensorimotor cortex (Dryżałowski et al., 2018), which exhibits abnormal changes in the functional connections of exercise-related networks (Jiang et al., 2020). Studies have shown decreased voxel-mirrored inter-hemispheric functional connectivity (FC) within the primary sensorimotor cortex (Cao et al., 2017). In addition, patients with BECTS exhibit abnormalities in advanced networks, with a significant reduction in activation strength of the default mode network (DMN) (Oser et al., 2014) during a task, which is related to cognitive function. Previous studies have shown that children with BECTS show abnormal brain functional activities and connections in both higher cognitive systems (e.g., DMN) and lower cognitive systems (e.g., sensorimotor network) (Jiang et al., 2020, Cao et al., 2017, Zeng et al., 2015, Xiao et al., 2016, Li et al., 2017, Li et al., 2019).

In recent years, a newly proposed connection gradient analysis has provided researchers with a more complete perspective by exploring continuous spatial connection patterns in the human brain (Margulies et al., 2016). When using the gradient method, each cortical vertex can be described by a set of values, which are called gradient scores, reflecting its position in the new dimension. The gradient method finds the principal axis of variance in the data through decomposition or embedding techniques, such as diffusion graph embedding (Margulies et al., 2016, Coifman et al., 2005) and the original dimension of the data is replaced by a set of new dimensions. The new dimension is inherently orderly, so the first dimension explains most of the variance (principal variance) in the data, and the second dimension explains the second largest variance of the data, and so on, that displays macroscale networks continuously in space (Margulies et al., 2016, Haak et al., 2018, Marquand et al., 2017). Specifically, it refers to the functional coordinate system from the low-level perceptual movement to the high-level multifunctional association, which moves towards the high-level association cortex and enables the brain to process more abstract and complex information. This hierarchical architecture promotes the separation of specialized functions (e.g., sensory and cognitive processes). Concurrently, it also realizes the dynamic reorganization and cross-communication of different levels of networks to realize more complex and abstract psychological activities (Huntenburg et al., 2018, Fulcher et al., 2019). Based on resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI), Margulies found a whole-brain principal gradient in the human cerebral cortex, which manifested as a spatial distribution from the primary/monomodal cortex to the cross-modal regions, confirming the principle of cerebral cortex layering (Margulies et al., 2016). This method has been widely applied in neuropsychiatric diseases such as depression (Xia et al., 2022), autism (Hong et al., 2019), schizophrenia (Dong et al., 2021, Lei et al., 2023), and Alzheimer's disease (Hu et al., 2022). Although previous studies have shown hierarchical changes in patients with BECTS (Zhang et al., 2023), our understanding of macroscale networks' continuous spatial arrangement remains limited. Further, it is unclear whether these large-scale functional network changes in children are related to cognitive function.

Understanding the relationship between changes in the functional hierarchy and brain dysfunction based on abnormal gradients can help detect functional reorganization in epilepsy. Thus, the objective of this study was to examine alterations in the macro-network function hierarchy in individuals with benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (BECTS) and its potential contribution to cognitive function in children with BECTS. Towards this goal, we systematically characterized connectome gradient abnormalities at the network and voxel levels in children with BECTS using rs-fMRI. We also focused on these gradient abnormalities and studied their relationship with cognitive function based on the gradient scores to predict cognitive function of children with BECTS by the relevance vector regression (RVR).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design and participants

The present study received approval from the medical ethics committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University, China. In accordance with the Helsinki Declaration, the researchers obtained written informed consent from all participants and their respective families.

This study involved 50 children with BECTS (mean (range) age: 9.80 ± 2.519 years (6–16 years); 24 girls, 26 boys). Here are the criteria for inclusion: (1) based on the criteria of the International League Against Epilepsy for diagnosing and classifying BECTS (Scheffer et al., 2017), (2) a routine structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examination revealed no abnormalities, and (3) age 6–16 years. These were the criteria for exclusion: (1) incomplete rs-fMRI scan, (2) history of other neuropsychiatric diseases, (3) craniocerebral trauma or surgical history, (4) head motion exceeding ±3 mm or ±3° and 0.5 mm of mean framewise displacement. The children with BECTS underwent the Chinese version of Children's Wechsler Intelligence, on the same day as the MRI scan. (There were 13 patients lacking intelligence test results due to non-cooperation or inability to perform intelligence tests during patient testing).

In addition, 69 healthy controls (HC) (mean (range) age: 10.53 ± 2.581 years (6–16 years); 30 girls, 39 boys) were included according to the following inclusion criteria: (1) no abnormalities on conventional structural MRI and (2) age 6–16 years. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) incomplete rs-fMRI scans, (2) history of any neurological disorder or psychiatric illness, (3) poor image quality, (IV) head motion exceeding 3 mm or 3° and a mean framewise displacement of 0.5 mm.

2.2. Data acquisition and processing

A 3.0-T MRI system was used (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA) to acquire the MRI data. The functional imaging of the resting state images were acquired using the whole brain gradient echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequence with the following parameters: repetition time = 2000 ms; echo time = 30 ms; inversion time = 900 ms; flip angle = 90°; field of view, 240 mm × 240 mm; slice thickness = 4.0 mm; and scan time = 420 s; voxel size = 3.75 mm × 3.75 mm × 4 mm. The following parameters were used to acquire high-resolution three-dimensional T1-weighted structural data: repetition time = 1900 ms, echo time = 2.1 ms, inversion time = 900 ms, flip angle = 15°, field of view = 240 mm × 240 mm, slice thickness = 1 mm, and scan time = 208 s. During the scanning process, participants were instructed to keep their eyes closed, not fall asleep, and move as little as possible. Preprocessing of rs-fMRI data was conducted with SPM12 (https://fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/) and DPABI (https://rfmri.org/dpabi). Initially, the initial 10 time points for each participant were excluded; subsequently, the execution of slice timing and head motion corrections was carried out. The functional images that had been realigned were subjected to normalization to the MNI standard space through utilization of an echo planar imaging template, followed by resampling to achieve 3-mm isotropic voxels. Next, the functional images underwent smoothing using a Gaussian kernel with a full-width at half-maximum of 6 mm.

Additionally, linear detrending was performed. We then regressed the nuisance covariates containing the friston-24 estimates of head motion, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid. Further, functional images were filtered for temporal bandpasses (0.01–0.08 Hz). Finally, a “scrubbing” technique was employed on the individual preprocessed datasets to eliminate outlier data caused by head motion. Specifically, participants who exhibited head motion exceeding ±3 mm or ±3° displacement were excluded from all subsequent analyses. Additionally, time frames exceeding an FD value of 0.5 mm, as well as their adjacent time frames, were excluded from the analysis. We substituted volumes and neighboring volumes (two frames forward and one frame backward) with linearly interpolated data when the framewise displacement exceeded a threshold of 0.5 mm.

2.3. Connectome gradient analysis

Functional connectomes were generated at the voxel level for each individual. The functional connectome was estimated by applying diffusion map embedding to capture the gradient components (Margulies et al., 2016, Hong et al., 2019) was applied to capture the gradient components and estimate the functional connectome. Specifically, top 10% of the connections of each node representing the backbone of the connectome were kept to characterize the most common connectivity profile of each node, while excluding weak connections resulting from noise. Taking advantage of the low complexity and applicability of sparse vectors, the cosine similarity between the thresholded connectivity profiles of each node pair was calculated. Negative values in the similarity matrix might result in imaginary numbers in subsequent dimensional reduction, and their biological meaning in the connectome gradient is unclear (Lariviere et al., 2020, Paquola et al., 2019). Thus, to prevent negative values, the normalized angle matrix was derived by scaling the similarity matrix. The functional connectome's connectivity pattern variance was explained by utilizing diffusion map embedding to capture the gradient components. To ensure alignment of the gradient maps among subjects, a procrustes rotation was executed (Hong et al., 2019, Lariviere et al., 2020).

Three global metrics were computed, namely the gradient explanation ratio, range, and variation (Xia et al., 2022). A two-sample t-test was employed to evaluate the disparities in voxel-level connectome gradient score and global metrics between the case and control groups, while accounting for the potential confounding effects of age, sex, and education. The voxel-wise comparison was conducted with a significance level of P < 0.001 at the voxel-level, and a cluster-level Gaussian random field (GRF) correction was applied with a threshold of P < 0.05. We utilized a standardized functional network partition consisting of seven network parcellations to estimate the discrepancies in gradient score between the groups at the network level (Yeo et al., 2011). A two-sample t-test was conducted to evaluate the variances in the network-level connectome gradient score between the BECTS and HC groups, while accounting for age, sex, and education as controlling factors. The FDR correction (P < 0.05) was used to establish the level of significance threshold. To study the clinical relevance of the differential connectome gradient scores, the correlation of the clinical variables (duration, age of onset, VIQ, PIQ, and FSIQ) with the gradients in abnormal brain regions was analyzed using Pearson’s correlation. The analysis primarily obtained the codes from Xia et al. (2022) (github.com/mingruixia/MDD_ConnectomeGradient), and we partially modified the codes.

2.4. The principal gradient difference of seed-based functional connectivity

Although the BECTS discharge area mainly affects the sensory-motor area, it is also reported that DMN is often involved. Connectome gradient studies have shown a continuous spatial arrangement from the initial sensory system to the trans-modal DMN in the principal gradient. Our study focused primarily on the principal gradient changes associated with BECTS. Based on the comparison of voxel-level gradients, we selected areas of the brain with obviously different gradients as the seed points to calculate the Pearson correlation coefficient between the ROI of each participant and other areas of the brain in the entire brain. Following that, we performed a Fisher-z transform to obtain a FC map using the seed points. The FC between the BECTS and HC groups was assessed by conducting a two-sample t-test, after accounting for the influences of age, sex, and education (GRF-corrected, voxel P < 0.001, cluster P < 0.05). To study clinical relevance of differential FC values in BECTS, we conducted Pearson's correlation analysis to assess the relationship between clinical variables (duration, age of onset, VIQ, PIQ, and FSIQ) with FC in abnormal brain regions.

2.5. Predicting cognitive function score outcomes with a machine learning model

The RVR algorithm was employed to assess the predictive capacity of principal gradients in relation to cognitive function scores among children diagnosed with BECTS. The principal gradient maps were used as a prediction feature, the accuracy of the prediction was estimated using leave-one-out cross-validation, this is calculated as Pearson's correlation coefficient between observed and predicted IQ. Nonparametric permutation tests were performed to evaluate the prediction accuracy, and the labels of the observed cognitive function of the subjects were random shuffling before RVR and cross-validated to obtain the corresponding accuracy rate after the cognitive function was disrupted. The upset was repeated 5000 times, and the accuracy of the 5000 times was calculated to be greater than that of the original data correlation coefficients. If the number of correlation coefficients after scrambling (random version data set) exceeded the number of correlation coefficients without scrambling (real data set) by less than 250, then the accuracy rate obtained was considered to be significant. The prediction analysis primarily utilized libsvm (https://www.csie.ntu.edu.tw/∼cjlin/libsvm/) and modified codes obtained from Cui and Gong (https://github.com/ZaixuCui/Pattern_Regression) (Cui and Gong, 2018).

2.6. Validation analysis

To assess the robustness of the main results, different parameters were used to repeat the entire processing flow, including multiple thresholds (row-wise 15% and row-wise 20%), z scores in FC matrix, and regression of global signals. The assessment of the spatial concordance of the gradient patterns was conducted through the computation of voxel correlations among distinct processing parameters (Yang et al., 2020). In order to conduct a more comprehensive assessment of the similarity in change gradient, we performed a calculation of the Dice coefficient for the clusters resulting from the significant group comparison by comparing the groups acquired using different processing parameters.

3. Results

3.1. Clinicodemographic participant characteristics

No statistically significant disparities were observed in terms of gender, age, or educational attainment between the BECTS and HC. The clinicodemographic characteristics of both the BECTS and control groups are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the sample.

| Characteristics | BECTS | HC | t/χ2 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects | 50 | 69 | − | − |

| Gender (female/male) | 24/26 | 30/39 | 0.239 | 0.625a |

| Age (years) | 9.80 ± 2.519 | 10.53 ± 2.581 | 0.344 | 0.128b |

| Education (years) | 4.72 ± 2.407 | 5.20 ± 3.075 | 2.759 | 0.358b |

| Duration (months) | 12(1.75 ∼ 32.25) | − | − | − |

| Age of onset (years) | 8.15 ± 1.890 | − | − | − |

| VIQ | 101.78 ± 20.508 | − | − | − |

| PIQ | 97.86 ± 18.091 | − | − | − |

| FSIQ | 100.39 ± 19.713 | − | − | − |

Chi-square test.

Two-sample t-test VIQ, Verbal intelligence quotient; PIQ, Performance intelligence quotient; FSIQ, Full-scale intelligence quotient.

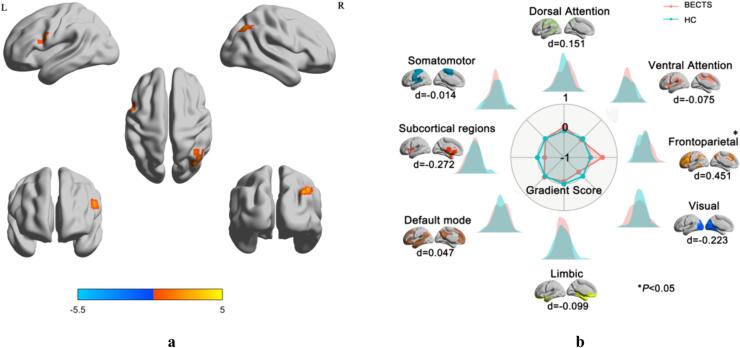

3.2. Macroscale gradients

Gradient functional networks at the voxel level were organized along a gradual gradient from the sensorimotor network (SMN) to the DMN in patients with BECTS and HC in the principal gradient (Fig. 1a) and along a gradual axis from DMN to dorsal attention network (DAN) in the secondary gradient (Fig. S1). The group statistical comparisons showed that the primary gradient between the BECTS and HC have no statistically significant in the three global metrics. Between-group comparisons revealed that the BECTS group exhibited a narrower range of secondary gradient score in the primary-to-transmodal gradient compared to the HC group (d = 0.367, P = 0.05), (Fig. S2, Table S1). Principal gradient maps for BECTS and HC showed strikingly similar spatial patterns. Upon visual examination of the histogram, it was observed that the extremes of the primary-to-transmodal gradient exhibited greater contraction within the BECTS range compared to the HC range (Fig. 1b). We conducted two sample t-tests across voxels to compare the gradient score between the averaged maps of the BECTS and HC groups for each system. In principal gradient, the BECTS group exhibited elevated gradient score in the DMN, frontoparietal network (FPN), and DAN but lower scores in the other networks compared with the HC group (Fig. 1c, Table S2). In the secondary gradient, the BECTS group exhibited elevated gradient score in the DAN, VAN, FPN, and SUB but lower scores in the SMN, VIS, LIM, and DMN (Table S3).

Fig. 1.

(a) The group-average cortical connectome gradient patterns. The principal gradient was averaged across patients with BECTS and HC. Surface rendering was generated using BrainNet Viewer. (b) Global and system-based histograms. The extreme values were contracted in the patients with BECTS relative to those in the HC. (c) System-based histogram of gradient. The direction of the significant differences between the BECTS and HC. VIS visual network, SMN sensorimotor network, DAN dorsal attention network, VAN ventral attention network, SUB subcortical regions, LIM limbic network, FPN frontoparietal network, DMN default mode network, BECTS Benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes, HC Health Control.

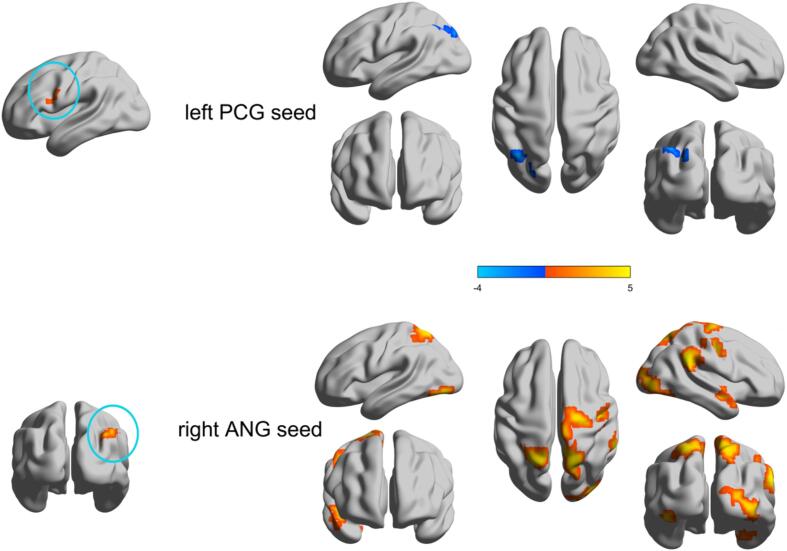

3.3. Voxel-level principal gradient alteration

We further conducted a comparative analysis of the principal gradients among different groups at the voxel level. The principal gradient exhibited elevated gradient score in the left precentral gyrus (PCG) and right angular gyrus (ANG) among patients diagnosed with BECTS (GRF-corrected, voxel P < 0.001, cluster P < 0.05) (Fig. 2a, Table S4). Patients diagnosed with BECTS exhibited a notable elevation in the gradient score within the left inferior frontal gyrus, triangular part in the secondary gradient, but the left precuneus and bilateral cuneus exhibited a significant reduction. (GRF-corrected, voxel P < 0.001, cluster P < 0.05) (Fig. S3a, Table S4).

Fig. 2.

(a) Voxel wise statistical comparisons between the HC and BECTS in the principal gradient. Higher values in BECTS are presented as warm. The statistical significance level was set as GRF-corrected (voxel P value < 0.001 and cluster P value < 0.05). (b) Network-level gradient comparisons between the HC and BECTS. The radar chart shows the gradient score (with respect to healthy controls) of the two groups. The FPN was increased (P < 0.05, uncorrected). Each network’s spatial location was anchored in the corresponding position, and Cohen’s d was computed.

Fig. 3.

The two group-difference of seed-based functional connectivity profiles of regions with abnormal principal gradients. Two clusters of the left PCG and right ANG were extracted as seeds respectively to examine the seed-cortex connectivity differences between the two groups. Higher/lower values in BECTS are presented as warm/cold colors, who had increased and decreased functional connectivity. The statistical significance level was set as GRF-corrected (voxel P value < 0.001 and cluster P value < 0.05). PCG precentral gyrus, ANG angular gyrus.

3.4. Network-level principal gradient alteration

We conducted a comparative analysis of the principal gradients among the groups at the network level. In the principal gradient, the FPN was higher in patients with BECTS than in HC (Cohen’s d = 0.450, P = 0.016, FDR uncorrected) (Fig. 2b, Table S5). In the secondary gradient, the DAN (Cohen’s d = 0.422, P = 0.025, FDR uncorrected) and FPN (Cohen’s d = 0.542, P = 0.004, FDR corrected) were also higher in patients with BECTS (Fig. S3b, Table S6).

3.5. Functional connectivity differences of abnormality regions in the principal gradient

The study investigated the alterations in functional connectivity associated with the principal gradient by examining seed-based functional connectivity patterns. We chose two seed from the voxel-level results of the principal gradient. The first cluster of seeds is mainly located in the left PCG, which showed that its functional connectivity with the left ANG decreased (GRF-corrected, voxel P < 0.001, cluster P < 0.05). The second cluster seed, which pertained to the right ANG, exhibited augmented functional connectivity with the right hippocampus, right middle occipital gyrus, right supramarginal gyrus, right PCG, right precuneus gyrus, left inferior occipital gyrus, and left superior parietal gyrus (GRF-corrected, voxel P < 0.001, cluster P < 0.05) (Fig. 3 and Table S7).

3.6. Clinical relations of functional connectome gradients in BECTS

There was a negative correlation observed between the principal gradient score of the left PCG and the verbal intelligence quotient (VIQ) among patients diagnosed with BECTS (r = −0.343, P = 0.038) (Fig. 4a, Table S8). The functional connectivity (FC) between the right ANG and the left inferior occipital gyrus(IOG) exhibited a positive correlation with both PIQ (r = 0.405, P = 0.013; Fig. 4b; Table S9) and FSIQ(r = 0.363, P = 0.027; Fig. 4c; Table S9) in individuals diagnosed with BECTS. However, the change in gradient score was not correlated with the seizure duration and age of onset.

Fig. 4.

(a) Pearson correlation between gradient score of left PCG and VIQ of the principal gradient in BECTS patients; (b) Pearson correlation between FC of right ANG and left IOG with PIQ of the BECTS patients; (c) Pearson correlation between FC of right ANG and left IOG with FSIQ of the BECTS patients. FC functional connectivity, PCG precentral gyrus, IOG inferior occipital gyrus, VIQ verbal intelligence quotient, PIQ performance intelligence quotient, FSIQ full-scale intelligence quotient. Note: There were 13 patients lacking intelligence test results due to non-cooperation or inability to perform intelligence tests during patient testing.

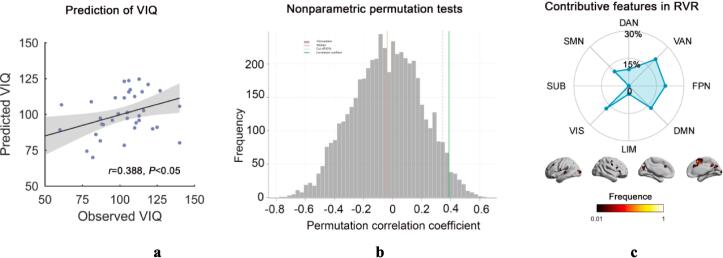

3.7. Predicting the cognitive function score of connectome gradients in patients diagnosed with BECTS

Patients' principal gradient maps significantly predicted their VIQ (r = 0.388, P = 0.017) (Fig. 5a), with the nonparametric permutation test showing the significance of the prediction accuracy (P = 0.029; Fig. 5b). The most significant contributing features were located in VAN (20.7%), FPN (19.9%), VIS (17.6%), and DMN (17.2%) (Fig. 5c). (There were 13 patients lacking intelligence test results due to non-cooperation or inability to perform intelligence tests during patient testing).

Fig. 5.

(a) Scatter plot presents the correlation between the observed VIQ and the predicted VIQ change derived from the RVR analysis (P = 0.017), Each dot represents the data from one patient, and the dashes indicate the 95 % prediction error bounds. (b) Nonparametric permutation tests (P = 0.029). (c) The absolute summed weights in leave-one-out cross validation were mapped onto the brain surface. Regions with higher/lower predictive power were colored in white/red. The radar map represents the distribution of predictive power in different systems. VIQ verbal intelligence quotient, RVR relevance vector regression. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article).

3.8. Validation results

There were similar patterns of principal gradients across groups with multiple thresholds and z scores, and global signals were regressed (Fig. S4). The main findings exhibited strong spatial correlations (all r > 0.96) with several processing parameters (Fig. S5), consistent with recent findings (Yang et al., 2020, Meng et al., 2021). The gradient patterns exhibited a high degree of similarity, indicating that the different parameters were robust. In addition, voxel-wise difference clusters and group comparison results had a moderate overlap (Dice coefficient) (Wilson et al., 2017) (Dice with main result: 0.58 ± 0.11, range: 0.43–0.78) (Fig. S6).

4. Discussion

We used the gradient connection method to prove that both BECTS and HC exhibited a conspicuous canonical pattern in the gradient, suggesting a prominent transmission from sensory-motor systems at lower levels to transmodal areas. On different scales, the patients with BECTS showed connectome gradient dysfunction patterns, closely consistent with previous research results on the vertex level (Zhang et al., 2023). Specifically, the current study showed that children with BECTS had higher gradient score in the left PCG and right ANG at the voxel level and in the FPN at the network level. The gradient score of the left PCG was significantly associated with the VIQ. Moreover, the principal gradient map of the children with BECTS significantly predicted their VIQ. These findings present potential biomarkers for predicting the cognitive function of children with BECTS and enhance comprehension regarding the neurobiological mechanisms underlying cognition in individuals with BECTS.

We found an increase in the gradient score in default network areas (e.g., the ANG) and an increase in unimodal regions (e.g., the PCG). Rs-fMRI studies have shown that children with BECTS have abnormal brain functional activity in the sensorimotor (Jiang et al., 2019) and default network area (Jiang et al., 2020, Li et al., 2017, Oser et al., 2014, Ofer et al., 2018, Li et al., 2020, Luo et al., 2016, Xu et al., 2022, Tan et al., 2018). The ANG is located in the DMN area, which suggests that BECTS can cause memory, language, and attention dysfunctions (Bonnici et al., 2016). The PCG is situated anterior to the central sulcus within the frontal cortex and is the motor center of the human body, and located in the SMN area. The findings of this study indicate that there was an observed elevation in the gradient score of the PCG among children diagnosed with BECTS, and this was consistent with the area of abnormal BECTS discharge, a higher gradient score suggests that a region is positioned at one end of the functional spectrum, which could either be closer to the sensory-motor network SMN, and deviates from the advanced DMN. Changes in gradient scores across the brain thus reflect shifts in the functional hierarchy, providing insights into the brain's organizational changes that might occur due to development, disease, or other factors affecting neural function. This study describes the spatial representation of gradual connective group transition, suggesting abnormalities between macroscale functional networks in children with BECTS.

Additionally, this study observed an abnormal alteration in the gradient score of the principal gradient of the FPN. FPN dysfunction was found, consistent with previous studies (Garcia-Ramos et al., 2015, Karalok et al., 2019, Chen et al., 2018). FPN networks in children with BECTS have already been categorized as aberrant, reflecting abnormal connectivity features. Changes in functional gradients indicate alterations in the connectivity axis of the brain, as well as abnormal modifications in the low-level sensory system and cross-modal DMN (Friedrich et al., 2020). In the current study, the gradient score of the primary-transmodal gradient exhibited a decrease within the DMN, while experiencing an increase within the SMN. Further, the hierarchical architecture of the network was from the DMN to the SMN, indicating a smaller distance between the unimodal and transmodal regions within the primary-transmodal gradient. This alteration in patients with BECTS may be attributed to the extreme contraction between the primary and transmodal systems, resulting in the disruption of the inherent differentiation between the sensorimotor and advanced cognitive DMN systems in BECTS (Murphy et al., 2018). Furthermore, the functional connectivity analysis conducted on the left PCG revealed that regions exhibiting heightened principal gradients exhibited reduced connectivity with the FPN and some DMN regions. In the right ANG, regions exhibiting heightened principal gradients demonstrated enhanced connectivity with both the transmodal and unimodal systems. These results indicate a significant degree of integration between the aforementioned systems in children diagnosed with BECTS.

Previous studies have shown that the PCG is the control center of the brain’s motor network interaction and the PCG plays a critical role in facilitating advanced cognitive processes, including the processing of emotional information and language function (Silva et al., 2022). There was a negative correlation observed between the change in the gradient score of the left PCG and the VIQ. Therefore, the association between the left PCG and VIQ indicates that changes in the functional gradient of the left PCG may lead to a decline in language function, and this involved a potential neural mechanism. This study presents additional empirical support regarding the correlation between alterations in functional gradients and cognitive functioning in diagnosed with BECTS. It also proves that disruption of the connection group hierarchy structure of the left PCG may be a potential imaging biomarker for cognitive impairment in BECTS. Our results establish the relationship between the network gradient and topology change in BECTS. Further, the abnormal functional connection between the right ANG and left IOG is related to PIQ and FSIQ. This finding implies that the disruption of network topology in the right ANG and left IOG could serve as a potential imaging biomarker for assessing cognitive function in individuals with BECTS. In this study, we utilized the Relevance Vector Regression (RVR) algorithm, which employs multivariate pattern analysis to predict VIQ. This machine learning approach synthesizes information across all brain voxels within a high-dimensional space, sensitive to the spatial and subtle associations across the brain that traditional univariate methods might overlook. Using RVR, we are able to detect voxels that collectively predict VIQ, and these voxels are further categorized into networks based on their spatial locations, thereby suggesting that some networks may be more predictive of VIQ than others. This approach underscores the nuanced nature of how cognitive networks may relate to higher cognitive functions like VIQ. Importantly, we found that the principal gradient score of the FPN and DMN made a substantial contribution to our prediction model for VIQ outcomes. Children with BECTS have dysfunction in the FPN and DMN, which are related to cognitive function (Ofer et al., 2018), and our findings extend the existing body of knowledge in this field. Furthermore, In addition to the FPN and DMN, the VAN and VIS should also be considered are potential markers for predicting cognitive function in BECTS. We haven't found the network related to cognitive function, and we need more data to verify the results in the future.

This study was subject to certain limitations, including a small sample size and incomplete drug record; thus, we could not include drugs in the analysis. Future studies should include a subgroup analysis the impact of pharmaceutical interventions on the functional connection gradient in drug-naïve patients with BECTS, drug-treated patients with BECTS, and HC. Second, this study was conducted at a single center, and it is imperative to conduct multicenter studies with a larger sample size to further verify the results.

5. Conclusion

We reported a systematically disrupted functional gradient in patients with BECTS and its negative correlation with cognitive function. These findings improve our comprehension the neurobiological mechanisms that underllie cognitive function and offer potential imaging biomarkers for the assessment of cognitive function in BECTS.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jie Hu: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Conceptualization. Guiqin Chen: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. Zhen Zeng: Data curation. Haifeng Ran: Methodology, Investigation. Ruoxi Zhang: Data curation. Qiane Yu: Data curation. Yuxin Xie: Investigation, Data curation. Yulun He: Data curation. Fuqin Wang: Data curation. Xuhong Li: Writing – review & editing. Kexing Huang: Writing – review & editing. Heng Liu: Writing – review & editing. Tijiang Zhang: Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the members of their research group for useful discussions.

Funding statement

This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 82171919, and 81960312), Intelligent Medical Imaging Engineering Research Center of Guizhou Higher Education Institutions project (Grant No. Qianjiaoji [2023] 038), Scientific Research Project of Higher Education Institutions of Guizhou Province (Youth Project) (GrantNo. Qian Jiaoji [2022] No.230), Young Outstanding Scientific and Technological Talent of Guizhou Province (grant No. Qiankehepingtairencai[2021]5620), and Talent Program for Future Famous Clinical Doctors of Zunyi Medical University (rc220211205).

Ethics approval statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University.

Patient consent statement

Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Footnotes

We confirm that we have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2024.103628.

Contributor Information

Heng Liu, Email: zmcliuh@163.com.

Tijiang Zhang, Email: tijzhang@163.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

The data that has been used is confidential.

References

- Bonnici H.M., Richter F.R., Yazar Y., et al. Multimodal feature integration in the angular gyrus during episodic and semantic retrieval. J. Neurosci. 2016;36(20):5462–5471. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4310-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao W., Zhang Y., Hou C., et al. Abnormal asymmetry in benign epilepsy with unilateral and bilateral centrotemporal spikes: a combined fMRI and DTI study. Epilepsy Res. 2017;135:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2017.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Fang J., An D., et al. The focal alteration and causal connectivity in children with new-onset benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes. Sci. Rep. 2018;8(1):5689. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-23336-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G., Hu J., Ran H., et al. Alterations of cerebral perfusion and functional connectivity in children with idiopathic generalized epilepsy. Front. Neurosci. 2022;16 doi: 10.3389/fnins.2022.918513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coifman R.R., Lafon S., Lee A.B., et al. Geometric diffusions as a tool for harmonic analysis and structure definition of data: diffusion maps. PNAS. 2005;102(21):7426–7431. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500334102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collin G., Nieto-Castanon A., Shenton M.E., et al. Brain functional connectivity data enhance prediction of clinical outcome in youth at risk for psychosis. Neuroimage Clin. 2020;26 doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2019.102108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Z., Gong G. The effect of machine learning regression algorithms and sample size on individualized behavioral prediction with functional connectivity features. Neuroimage. 2018;178:622–637. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong D., Yao D., Wang Y., et al. Compressed sensorimotor-to-transmodal hierarchical organization in schizophrenia. Psychol. Med. 2021:1–14. doi: 10.1017/S0033291721002129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dryżałowski P., Jóźwiak S., Franckiewicz M., et al. Benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes – current concepts of diagnosis and treatment. Neurol. Neurochir. Pol. 2018;52(6):677–689. doi: 10.1016/j.pjnns.2018.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich P., Forkel S.J., Thiebaut de Schotten M. Mapping the principal gradient onto the corpus callosum. Neuroimage. 2020;223 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.117317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulcher B.D., Murray J.D., Zerbi V., et al. Multimodal gradients across mouse cortex. PNAS. 2019;116(10):4689–4695. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1814144116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Ramos C., Jackson D.C., Lin J.J., et al. Cognition and brain development in children with benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes. Epilepsia. 2015;56(10):1615–1622. doi: 10.1111/epi.13125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2016 Neurology Collaborators Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(5):459–480. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30499-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haak K.V., Marquand A.F., Beckmann C.F. Connectopic mapping with resting-state fMRI. Neuroimage. 2018;170:83–94. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.06.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S.J., Vos de Wael R., Bethlehem R.A.I., et al. Atypical functional connectome hierarchy in autism. Nat. Commun. 2019;10(1):1022. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08944-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Q., Li Y., Wu Y., et al. Brain network hierarchy reorganization in Alzheimer's disease: a resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2022;43(11):3498–3507. doi: 10.1002/hbm.25863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntenburg J.M., Bazin P.L., Margulies D.S. Large-scale gradients in human cortical organization. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2018;22(1):21–31. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2017.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim B., Suppiah S., Ibrahim N., et al. Diagnostic power of resting-state fMRI for detection of network connectivity in Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2021;42(9):2941–2968. doi: 10.1002/hbm.25369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S., Luo C., Huang Y., et al. Altered static and dynamic spontaneous neural activity in drug-naïve and drug-receiving benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2020;14:361. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2020.00361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y.C., Song L., Li X., et al. Dysfunctional white-matter networks in medicated and unmedicated benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2019;40(10):3113–3124. doi: 10.1002/hbm.24584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karalok Z.S., Öztürk Z., Gunes A. Cortical thinning in benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (BECTS) with or without attention-deficit/hyperactivity (ADHD) J. Clin. Neurosci. 2019;68:123–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2019.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lariviere S., Vos de Wael R., Hong S.J., et al. Multiscale structure-function gradients in the neonatal connectome. Cereb. Cortex. 2020;30(1):47–58. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhz069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei W., Xiao Q., Wang C., et al. The disruption of functional connectome gradient revealing networks imbalance in pediatric bipolar disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2023;164:72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2023.05.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Ji G.J., Yu Y., et al. Epileptic discharge related functional connectivity within and between networks in benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes. Int. J. Neural Syst. 2017;27(7):1750018. doi: 10.1142/S0129065717500186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Sun Y., Niu K., et al. The relationship between neuromagnetic activity and cognitive function in benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes. Epilepsy Behav. 2020;112 doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.107363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Wang L., Chen H., et al. Abnormal dynamics of functional connectivity density in children with benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes. Brain Imaging Behav. 2019;13(4):985–994. doi: 10.1007/s11682-018-9914-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo C., Yang F., Deng J., et al. Altered functional and effective connectivity in anticorrelated intrinsic networks in children with benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95(24) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margulies D.S., Ghosh S.S., Goulas A., et al. Situating the default-mode network along a principal gradient of macroscale cortical organization. PNAS. 2016;113(44):12574–12579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1608282113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquand A.F., Haak K.V., Beckmann C.F. Functional corticostriatal connection topographies predict goal directed behaviour in humans. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2017;1(8):0146. doi: 10.1038/s41562-017-0146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinnity C.J., Smith A.B., Yaakub S.N., et al. Decreased functional connectivity within a language subnetwork in benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes. Epilepsia Open. 2017;2(2):214–225. doi: 10.1002/epi4.12051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Y., Yang S., Chen H., et al. Systematically disrupted functional gradient of the cortical connectome in generalized epilepsy: initial discovery and independent sample replication. Neuroimage. 2021;230 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.117831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy C., Jefferies E., Rueschemeyer S.A., et al. Distant from input: evidence of regions within the default mode network supporting perceptually-decoupled and conceptually-guided cognition. Neuroimage. 2018;171:393–401. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ofer I., Jacobs J., Jaiser N., et al. Cognitive and behavioral comorbidities in Rolandic epilepsy and their relation with default mode network's functional connectivity and organization. Epilepsy Behav. 2018;78:179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2017.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oser N., Hubacher M., Specht K., et al. Default mode network alterations during language task performance in children with benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (BECTS) Epilepsy Behav. 2014;33:12–17. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overvliet G.M., Besseling R.M., van der Kruijs S.J., et al. Clinical evaluation of language fundamentals in Rolandic epilepsy, an assessment with CELF-4. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2013;17(4):390–396. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paquola C., Vos De Wael R., Wagstyl K., et al. Microstructural and functional gradients are increasingly dissociated in transmodal cortices. PLoS Biol. 2019;17(5):e3000284. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheffer I.E., Berkovic S., Capovilla G., et al. ILAE classification of the epilepsies: position paper of the ILAE commission for classification and terminology. Epilepsia. 2017;58(4):512–521. doi: 10.1111/epi.13709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva A.B., Liu J.R., Zhao L., et al. A neurosurgical functional dissection of the middle precentral gyrus during speech production. J. Neurosci. 2022;42(45):8416–8426. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1614-22.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan G., Xiao F., Chen S., et al. Frequency-specific alterations in the amplitude and synchronization of resting-state spontaneous low-frequency oscillations in benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes. Epilepsy Res. 2018;145:178–184. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2018.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickens S., Bowden S.C., D'Souza W. Cognitive functioning in children with self-limited epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epilepsia. 2017;58(10):1673–1685. doi: 10.1111/epi.13865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson S.M., Bautista A., Yen M., et al. Validity and reliability of four language mapping paradigms. Neuroimage Clin. 2017;16:399–408. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2016.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia M.R., Liu J., Mechelli A., et al. Connectome gradient dysfunction in major depression and its association with gene expression profiles and treatment outcomes. Mol. Psychiatr. 2022;27(3):1384–1393. doi: 10.1038/s41380-022-01519-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao F., An D., Lei D., et al. Real-time effects of centrotemporal spikes on cognition in rolandic epilepsy: an EEG-fMRI study. Neurology. 2016;86(6):544–551. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu K., Wang F., Geng B., et al. Abnormal percent amplitude of fluctuation and functional connectivity within and between networks in benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes. Epilepsy Res. 2022;185 doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2022.106989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan X., Yu Q., Gao Y., et al. Cognition in patients with benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes: a study with long-term VEEG and RS-fMRI. Epilepsy Behav. 2017;76:120–125. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2017.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S., Meng Y., Li J., et al. The thalamic functional gradient and its relationship to structural basis and cognitive relevance. Neuroimage. 2020;218 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.116960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo B.T., Krienen F.M., Sepulcre J., et al. The organization of the human cerebral cortex estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J. Neurophysiol. 2011;106(3):1125–1165. doi: 10.1152/jn.00338.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng H., Ramos C.G., Nair V.A., et al. Regional homogeneity (ReHo) changes in new onset versus chronic benign epilepsy of childhood with centrotemporal spikes (BECTS): a resting state fMRI study. Epilepsy Res. 2015;116:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2015.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Li J., He Y., et al. Atypical functional connectivity hierarchy in Rolandic epilepsy. Commun. Biol. 2023;6(1):704. doi: 10.1038/s42003-023-05075-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that has been used is confidential.