Abstract

Background

Youth involved in child welfare have high rates of mental health problems and are known to receive mental health services from multiple settings. Still, gaps remain in our understanding of service use patterns across settings over the course of youth’s involvement with child welfare.

Objective

To examine the settings, reasons for contact, persons involved in initiating care, and timing of each mental health service contact for individuals over their involvement with the child welfare system, and to identify factors that predict multi-setting use.

Methods

Data on mental health service contacts were collected retrospectively from charts for youth aged 11–18 (n=226) during their involvement with child welfare services in Montreal, Quebec. Logistic regression analysis was conducted to determine predictors of multi-setting mental health services use (defined as ≥3 settings).

Results

83% of youth had at least one mental health service contact over the course of their child welfare services follow-up, with 45% having multi-setting use. Emergency Departments were the top setting for mental health services. Youth with a higher number of placements and from neighborhoods with greater social and material deprivation were significantly likelier to use ≥3 mental health service settings over the course of their follow-up.

Conclusion

These findings suggest a need for enhanced collaboration between youth-serving sectors to ensure that continuous and appropriate mental health care is being offered to youth followed by child welfare systems. The relationship between placement instability and multi-setting mental health service use calls for specific policies to ensure that young people do not experience multiple discontinuities of care.

Keywords: youth, mental health services, child welfare, service use

Résumé

Contexte

Les jeunes impliqués dans le système de la protection de la jeunesse ont des taux élevés de problèmes de santé mentale et il et ils reçoivent souvent des services de santé mentale dans plusieurs types d’établissements. Pourtant, des lacunes subsistent dans notre compréhension des trajectoires d’utilisation des services à travers divers contextes au cours du suivi d’un jeune dans le système de protection de la jeunesse.

Objectif

Examiner les contextes, les raisons pour les contacts, les personnes impliquées dans l’initiation des soins, et le moment de chaque contact avec les services de santé mentale pour les personnes pendant la durée de leur suivi en protection de la jeunesse et identifier les facteurs qui prédisent une trajectoire impliquant de multiples établissements.

Méthodes

Des données sur les contacts avec les services de santé mentale ont été recueillies rétrospectivement des dossiers de jeunes de 11 à 18 ans (n=226) leur suivi en protection de la jeunesse à Montréal, Québec. Une analyse de régression logistique a été menée pour déterminer les prédicteurs de l’utilisation des services de santé mentale multi-établissements (définie à ≥3 établissements).

Résultats

Quatre-vingt-trois pour cent des jeunes avaient au moins un contact avec un service de santé mentale au cours de leur suivi en protection de la jeunesse, et 45 % avaient une trajectoire impliquant de multiples établissements. Les services d’urgence étaient l’établissement le plus fréquenté pour les services de santé mentale. Les jeunes ayant un nombre plus élevé de placements et provenant de quartiers d’une plus grande défavorisation sociale et matérielle étaient significativement plus susceptibles d’utiliser ≥3 établissements de services de santé mentale au cours de leur suivi.

Conclusion

Ces résultats démontrent le besoin d’une collaboration améliorée entre les secteurs des services aux jeunes pour faire en sorte que les jeunes en protection de la jeunesse reçoivent des soins de santé mentale continus et appropriés. La relation entre l’instabilité de placement et les trajectoires complexes à travers les services de santé mentale exige de politiques spécifiques afin d’assurer que les jeunes ne connaissent pas de multiples discontinuités de soins.

Mots clés: jeunes, services de santé mentale, protection de l’enfance, utilisation des services

Introduction

Youth involved with the child welfare system (CWS) are known to have high rates of mental health problems, with estimates ranging from 25 to 61% (1, 2). A 2016 meta-analysis of epidemiological surveys reported a pooled prevalence of 49% for mental disorders among youth involved with the CWS, which is nearly four times greater than the prevalence among youth in the general population, estimated at 13% (3). A recent systematic review reported that the most common psychiatric conditions among youth involved in the CWS were conduct disorders, substance use disorders, suicidality, major depressive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, and attachment disorders; and that comorbid conditions were common (4). Youth in child welfare services have rates of suicide attempts that are four times higher than youth in the general population, and rates of substance use that are five times higher than their peers. Such high rates of mental health problems have been reported whether the youth were placed into care outside of their home (1, 5, 6) or remained in their family home during child welfare involvement (1, 7, 8).

Numerous studies have also shown that many young people within the CWS do not receive mental health services when needed, and that in fact, these youth commonly experience barriers in accessing appropriate, continuous, quality mental health care (9–11). A survey of a nationally representative sample of children followed by child welfare agencies in the United States (US) found that only 44% of children in need of mental health services received care (1). A recent study, also from the US, found that at age 17, 68% of child welfare-involved youth had behavioural health problems, but only half of these youth were receiving mental health services (12). A recent study from Canada showed that many youth with a history of maltreatment and of child welfare involvement had never received mental health services, despite having high needs (13). Among child welfare-involved youth, factors related to the receipt of mental health services include non-kin placements (1, 14), parental risk factors, such as mental illness (1, 14), being a child of immigrants (a USA study) (15), gender [(mixed findings, with females (16) or males (1, 14, 17) being more likely to use services], having experiences of childhood adversity (1, 14, 18, 19), and higher social/material deprivation (20).

For youth in the CWS who do receive mental health services, these are often provided across different settings, including schools, hospitals, and community-based primary health centres (14). A two-timepoint investigation of mental health utilization across various settings in the US found that up to one-third of child welfare youth had received mental health services from three or more distinct settings (14). Such knowledge is crucial as this may indicate that youth in the CWS may be at higher risk for falling through gaps in service delivery (21), and face more transitions and instability in their experiences of care. To our knowledge,, studies looking at multi-setting service use in by children in the CWS have used either cross-sectional data or data for a specific time period (e.g., previous 12 months.) Little is known about the use of mental health services, over the entire period of youths’ involvement with the CWS. Such data are important to inform policy and service delivery for youth in CWS. It can also serve to answer questions about whether and how the CWS is responding to the needs of young people in their care.

A recent survey based in Quebec showed that mental health needs of child welfare-involved youth increased after they aged out of the system (22). However, there is a still a lack of information in Canada on the individual mental health service use of young people while still involved with the CWS, and of individuals’ use of multiple service settings. This is partly attributable to a lack of reporting on service trajectories and service provision in the CWS, and to difficulties in linking child welfare and administrative health datasets (23). We aimed to address these gaps by conducting an in-depth, longitudinal, chart-based study of individuals’ mental health service use throughout their years of involvement with child welfare services in Montreal, Canada. The study had two aims: 1) to examine the settings, reasons for contact, persons involved in initiating care, and timing of each mental health service contact for individuals over their involvement with the CWS, and 2) to identify factors that predict multi-setting use, (i.e., use of mental health services across multiple different settings).

Methods

Healthcare and child welfare context

In the province of Quebec, healthcare organizations (including community-based primary health centres, rehabilitation and youth centres, residential centers, and specialized and general hospitals) are organized geographically, with services planned and delivered to address the needs of a population within a defined catchment area. Mental health services are offered in primary care settings (i.e., local, community-based primary health centres); secondary care settings (i.e., specialized services, hospital-based inpatient or outpatient centres); and tertiary care settings (i.e., residential programs). Private-sector mental health services are also widely used (24–26), predominantly through private psychologists, psychotherapists, and social workers.

The Youth Protection Act, adopted in 1979, governs the child welfare system in Quebec. Child welfare agencies provide an array of services, including psychosocial, rehabilitation and social integration services, family support and supervision, adoption, court reports, care placements, etc., for youth who have been deemed to have experienced abuse (physically, psychologically, sexually), been neglected, or exhibit behavioural problems. In Canada, youth involved with child welfare services typically remain involved for an average of four years, though many remain involved much longer (27). Placements refer to the placing of children outside of their family home, often with other family members (kin), with non-kin foster parents, or in group home settings, on a temporary or permanent basis. Child welfare workers may offer certain mental health interventions (e.g., risk assessment, psychotherapy), to youth in care. However, most often, youth involved in child welfare services end up using public or private mental health services when needed.

Ethics

This study was approved by the Centre Jeunesse de Montréal-Institut Universitaire Institutional Ethics Committee (REB Approval ID: CJM- IU: 16-06-12).

Study design and sample

Our study used a descriptive retrospective chart and case file review methodology.

Our sample included 226 youth aged 11–17 who received child welfare services from two agencies in Montreal (Agency one, n=142; and Agency two, n=84) between 2013 and 2015. Charts were selected based on parents’ postal codes being located within two distinct catchment areas. The two sites were chosen as they were a part of a large scale youth mental health transformation project implemented in 2015 (28). Data from the two cohorts was continuously collected from youth’s entry in child welfare services until 2019, or when the youth aged out of the system. Other than age restrictions, no inclusion/exclusion criteria were used.

Data collection

Trained research assistants systematically collected information from welfare records, using a detailed template created for the study (coding book available from the authors on request). Medical and psychosocial records held by child welfare agencies are extensive, allowing for chart review methodology to capture trajectories through services and care. On intake, child welfare workers collect a full oral family history pertaining to physical and mental health, service use, referrals to services, parental histories, etc., dating from the child’s birth to present. Whenever available, police, medical and school records are included in the charts. Ten percent of all charts were randomly picked for independent review to ensure coding accuracy. Inter-rater reliability was high (mean Cohen’s kappa κ =.71, range 0.54–0.82 (29).

To complement chart review, data from administrative electronic files were also retrieved. This clinical and administrative dataset is a common platform used across child welfare settings in Quebec for management and research purposes. Child welfare workers enter information related to reports, assessments, referrals, and case reviews (30). These data were used to obtain information on youth and parent demographic information, maltreatment history, and placement history. Social and material deprivation were derived by matching youths’ postal codes with relevant indices from the Institut national de santé publique (46). These extensively used indices were developed from census data using six neighbourhood-level population indicators known to be proxies for deprivation: completion of secondary education; employment status; living situation; average income; marital status; and proportion of single parent family units.

In our analysis, social and material deprivation indices were combined and divided into quintiles, with the most severe deprivation indicated as quintiles four and five.

To document service use, all mental health contacts (defined as contacts involving a mental health professional and/or for a mental health problem) were noted. To distinguish between episodes of care, multiple appointments with one service (e.g., treatment occurring over a defined period) was counted as one contact.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were calculated for socio-demographic, childhood adversity, placement, and parental risk factors (parental history of mental illness or child welfare involvement) variables.

Aim 1

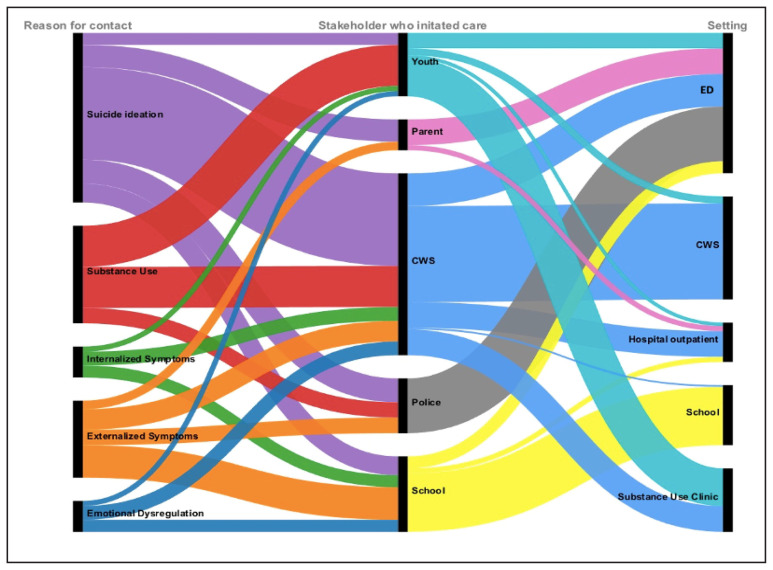

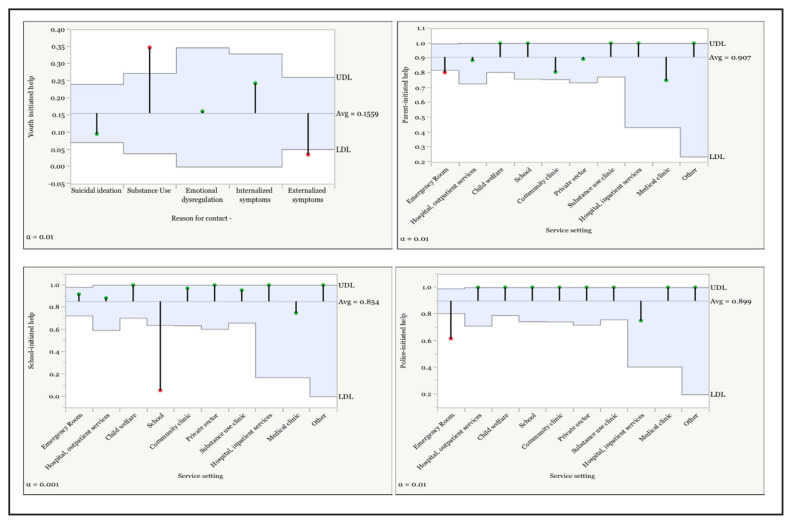

Characteristics of each mental health service contact were examined, beginning with the type of mental health problem requiring care, the stakeholder who initiated care, and the setting within which care was received. To compare the proportion of stakeholders initiating care for each type of mental health problem, we used an Analyses of the Means (ANOM) of Proportions (31). This analysis compares the absolute deviations of group means from their overall mean. An alluvial diagram was built to depict these patterns using RawGraphs 2.0. An alluvial diagram is a visual representation across categorical variables which allows a visual display across different domains.

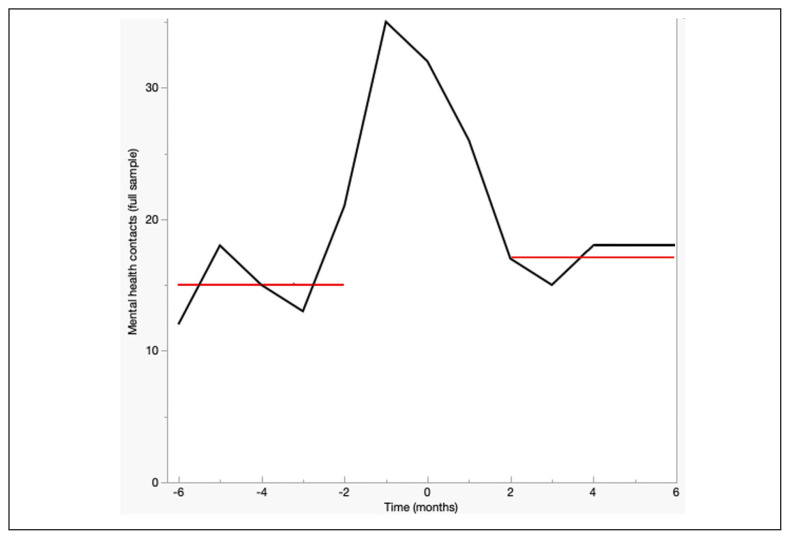

We then examined whether a youths’ involvement with child welfare agencies was linked to an increase in mental health service use. For this, we used a change-point analysis procedure, which detects abrupt changes in data when a property of the time-series changes (32), in this case, the initial involvement of child welfare services. We established the number of mental health service contacts per month in the six months prior to child welfare services involvement and then in the subsequent first six months of child welfare services involvement. We used the changepoint package in R to detect the change in variance of the data. The cpt.meanvar function with binary segmentation (BinSeg) method was employed to determine the number of changes in the mean and/or variance of the data. This analysis allows us to find the sequence of observations where a change in mean is detected and the percentage of this mean difference.

Aim 2

We then examined what factors were associated with youths’ multi-setting use. Multi-setting use was defined as using ≥3 settings for mental health care during the course of child welfare involvement. This definition was operationalized based on the frequency distribution of number of settings in this sample and informed by previous literature, particularly a prior study (14) that had previously investigated multi-setting service use. Given the binary outcome, a logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify predictors associated with multi-setting use. Analyses were performed using JMP 16 Pro.

Results

Sample characteristics

As outlined in Table 1, the median age for youth at their first involvement with child welfare services was 12 years old (Interquartile range 7–13 years). Our sample had slightly more females than males (54% vs 46%). 53% of the total sample belonged to a visible minority group, and 46% of the sample were either born outside of Canada or had at least one parent born outside of Canada. 71% of the sample lived in areas with high or very high levels of social and material deprivation.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics (n=226)

| % (n) | |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 46 (103) |

| Female | 54 (123) |

| Visible minority status | |

| Visible minority | 53 (113) |

| Non-visible minority | 47 (101) |

| Immigration status | |

| 1st generation (immigrant) | 19 (41) |

| 2nd generation (1 or 2 parents born outside Canada) | 27 (59) |

| 3rd generation or higher (non- immigrant) | 54 (119) |

| Environment | |

| Social and/or material deprivation, (Q4&Q51) | 71 (155) |

| Maltreatment history2 | |

| Physical neglect, yes | 23 (50) |

| Sexual abuse, yes | 28 (61) |

| Psychological abuse, yes | 56 (123) |

| Physical abuse, yes | 56 (122) |

| Neglect, yes | 83 (183) |

| Parental history | |

| Parental history of child welfare involvement3 | |

| No | 77 (168) |

| Yes | 23 (51) |

| Parental history of death by suicide | |

| Yes | 14 (31) |

| No | 86 (188) |

| Parental history of mental health problems | |

| Yes | 77 (169) |

| No | 23 (50) |

| Child welfare trajectory | |

| Placement during child welfare involvement (yes ) | 78 (170) |

| Median, Mean, IQR4 | |

|

| |

| Number of total placements | 3, 4, 1–5.25 |

| Age at child welfare involvement (years) | 12, 9, 7–13 |

| Age at first placement out of home (years) | 13, 10, 8–14 |

| Age at first noted symptom (years) | 10, 8, 6–12 |

| Duration of child welfare involvement (years) | 4.4, 4.8, 3.4–5.5 |

A variable reflecting a composite score of social and material deprivation was created. High deprivation was categorized as the two highest quintiles of that variable (Q4 and Q5).

At onset of child welfare involvement

For youth born in Quebec

Interquartile range

Aim 1. Examining mental health service use

Of the overall sample (n=226), 83% (n=188) of youth had at least one contact with mental health services over the course of their follow-up by child welfare. Of these 188 youth, 49% (n=92) had had contacts with mental health services prior to their involvement with child welfare services.

A. Reasons for service use

The most common reason for contact with mental health services during child welfare involvement was suicidal ideation (17% of all contacts); followed by externalized symptoms (15%) and substance use (11%). One-third of youth service users had at least one episode of care that followed them expressing suicidal ideation during their involvement with child welfare. See Table 2 for more details.

Table 2.

Characteristics of mental health service contacts during child welfare involvement

| Reason for Contact | Total mental health service contacts (N=861) % (n) | Total service users (N=188) % (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Suicidal ideation | 17 (141) | 32 (61) |

| Externalized symptoms | 15 (132) | 39 (73) |

| Substance Use | 11 (87) | 21 (39) |

| Internalized symptoms | 7 (57) | 21 (40) |

| Decline in functioning | 8 (66) | 25 (47) |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 4 (38) | 14 (26) |

| Emotional dysregulation | 4 (35) | 14 (27) |

| Medication related follow-up | 4 (32) | 13 (25) |

| Self-harm | 3 (29) | 9 (16) |

| Eating disorder | 2 (15) | 4 (7) |

| Suicide attempt | 4 (38) | 10 (19) |

| Borderline personality traits | 1 (11) | 3 (6) |

| Hallucinations | 1 (9) | 4 (7) |

| Somatic symptoms | 1 (8) | 3 (5) |

| Other | 14.5 (127) | - |

| Missing | 4 (36) | -- |

|

| ||

| Stakeholder initiating care | ||

| Child welfare worker | 36 (292) | 64 (120) |

| School staff | 15 (119) | 41 (77) |

| Youth themselves | 11 (87) | 24 (46) |

| Family | 7 (62) | 23 (44) |

| Judge | 8 (64) | 22 (41) |

| Police | 6 (49) | 18 (34) |

| Hospital staff | 7 (59) | 16 (30) |

| Emergency Department staff | 4 (25) | 13 (25) |

| Community-based primary healthcare staff | 5 (33) | 11 (21) |

| Medical clinic staff | 2 (14) | 6 (12) |

| Private sector professional | 0.2 (2) | 1 (2) |

| Substance use facility staff | 0.2 (2) | 1 (2) |

|

| ||

| Setting of mental health contact | ||

| Emergency Department | 19 (157) | 39 (74) |

| Hospital outpatient clinic | 18 (154) | 43 (81) |

| Child welfare agency | 16 (135) | 36 (68) |

| School | 3 (111) | 43 (81) |

| Community-based primary healthcare centre | 13 (112) | 37 (70) |

| Private sector | 8 (71) | 28 (53) |

| Substance use clinic | 6 (54) | 16 (30) |

| Inpatient unit | 3 (27) | 8 (15) |

| Medical other | 3 (30) | 13 (24) |

| Missing | 1 (10) | NA |

B. Stakeholders involved in initiating care

We examined the key stakeholders involved in initiating contact with mental health services.

Child welfare services were the most common initiators of mental health contacts, followed by schools and youth themselves. Almost one-quarter of all youth had at least one contact with mental health services that they had initiated themselves, and one-fifth had at least one contact initiated by a judge.

C. Settings of mental health service contacts

Emergency departments (EDs) were the most common setting for mental health services, with almost 20% of all mental health contacts occurring at the ED, followed closely by hospital outpatient clinics and services within the child welfare agency (Table 2). Nearly 40% of youth who had received mental health services had had at least one contact with an ED over the course of their follow-up by child welfare services. 8% of all contacts were with the private sector, with 28% of youth who had sought mental health services having accessed private services at least once.

D. Characteristics of care episodes

We examined the patterns between stakeholder initiating care, mental health problem, and service setting contacted (See Figure 1). We conducted an Analysis of means for proportions to determine whether group proportions differed significantly from the overall sample proportions. From these analyses (see Figure 2) we found that youth were significantly more likely to self-initiate care for substance use problems, and to seek help from substance use clinics. Schools were most likely to initiate mental health help-seeking for youths’ externalized symptoms, and to seek help within school-based settings. Finally, both parents and police were most likely to initiate care contacts at the ED.

Figure 1.

Pathways from mental health symptoms to initiators of care and mental health contact setting

Figure 2.

Analyses of means of proportions (ANOMs) for youth-, parent -, school- and police-initiated mental health contacts

UDL: Upper decision limit; LDL = lower decision limit. The UDL and LDL define a confidence interval, in this case, for α = 0.01. When a statistic falls outside of the decision limits (indicated by a red dot), this is an indication of a statistical difference between that group’s average and the overall average for all the groups.

E. Timing of mental health service contacts

Change point detection analysis was conducted to examine whether there were significant changes in the frequency of mental health service contacts in the six months before and the six months after involvement with the child welfare system (See Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Change point analysis was used to detect changes in the mean number of mental health contacts for the sample in the 6 months preceeding and 6 months following CWS involvement,

Monthly mean number of contacts (black lines) and change poiny locations (red lines) are shown with significant change points detected at −2 and +2 months.

Two change points were detected which resulted in three distinct time-series segments. At six months prior to the involvement of child welfare services, the mean number of contacts for the entire sample was 14.5 contacts/month. At the first change point, which occurred two months before the involvement of child welfare services, the number of contacts began increasing significantly until child welfare services got involved (i.e., at −1 month, the mean number of contacts rose to 35 contacts/month, an increase of 241%”).The second change point, which occurred at two months after child welfare services got involved, represented a decrease in contacts (mean 17 contacts/month).

Given the high number of contacts occurring at the start of involvement of child welfare services, further analyses were conducted to investigate the types of mental health contacts occurring in these first weeks. Of the 35 mental health contacts that occurred within the first month following the start of child welfare involvement, 15 occurred on the same day that a youth was flagged to child welfare. These contacts were primarily ED visits initiated by entities other than child welfare services.

Aim 2: Examining multi-setting use

We investigated the use of multiple settings over the course of young people’s follow-up by child welfare services. In line with prior research, we defined multi-setting use as having accessed mental health services at three or more settings over the course of follow-up by child welfare services. Many youth (45%) had accessed mental health services in at least three distinct setting types, (e.g., school, private sector, ED). The median number of settings for this group was 4.4 settings, with a range from 3–8 settings.

We conducted a logistic regression to examine multi-setting use for mental health problems in relation to the following variables — gender, visible minority status, immigration status, social and material deprivation; childhood adversity measures including physical neglect, emotional neglect, physical abuse, emotional abuse, and sexual abuse; parental history of mental illness or child welfare involvement; number of placements and duration of follow-up by child welfare services. Tests to ensure that our data met the assumption of collinearity were conducted, using variance inflation factors. These tests indicated that multicollinearity was not a concern (VIF range = 1.21–2.31).

The logistic regression model was significant, (χ2 (14) = 45.72, p<0.0001). It explained 18% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance and accurately classified 79% of the cases as having used ≥3 settings versus one or two settings. The model (Table 3) revealed that higher numbers of placements and higher levels of social/material deprivation were associated with the use of ≥3 settings. Adjusted odds ratios are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Logistic regression on factors predicting multi-setting use

| Multi-setting use (≥3 settings) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| OR | 95% CI | X2 | p | |

| Gender (ref.=male) | 1.13 | 0.51–2.52 | 0.10 | 0.74 |

| Immigrant (ref.=none) | 0.76 | 0.21–2.68 | 0.42 | 0.52 |

| Visible minority (ref.=no) | 1.40 | 0.54–3.67 | 0.49 | 0.48 |

| Social & Material Deprivation1 (ref.=Q1–3)1 | 2.87 | 1.28–6.48 | 6.49 | 0.01 |

| Psychological abuse (ref.=No) | 0.79 | 0.17–1.51 | 0.36 | 0.55 |

| Emotional Neglect (ref.=No) | 0.51 | 0.17–1.51 | 1.48 | 0.22 |

| Physical Abuse (ref.=No) | 0.96 | 0.45–2.03 | 0.01 | 0.92 |

| Sexual abuse (ref.=No) | 1.97 | 0.86–4.50 | 2.60 | 0.10 |

| Physical neglect (ref.=No) | 0.53 | 0.22–1.30 | 1.89 | 0.17 |

| Parent with history of child welfare involvement (ref.=No) | 1.21 | 0.51–2.86 | 0.18 | 0.67 |

| Parent with history of mental illness (ref.=No) | 1.95 | 0.71–5.33 | 1.71 | 0.19 |

| Years of child welfare involvement after age 11 | 1.20 | 0.93–1.53 | 1.98 | 0.16 |

| Number of placements | 1.26 | 1.10–1.43 | 12.46 | <.001 |

| Whole model test | X2 | df | R2 | p |

|

| ||||

| 45.72 | 14 | 0.18 | <.0001 | |

OR: Odds ratio; CI: Confidence interval; ref.=reference group

A variable reflecting a composite score of social and material deprivation was created. High deprivation was categorized as the two highest quintiles of that variable (Q4 and Q5). The reference group was the lower deprivation category (quintiles Q1, Q2, Q3)

Discussion

This study examined the patterns of mental health service use by youth in the CWS. Overall, a large majority of youth (83%) had contact with mental health services over the course of their involvement with the CWS. In any given year, between 36–45% of the sample had at least one contact with mental health services, which is about double that of the estimate for the general Canadian youth population according to a 2018 population survey (17%) (33).

Overall mental health service use

As previously described by our group (26), EDs were the leading point of service receipt for youth in the CWS. High rates of ED use for mental health problems have also been noted in the general youth populations, with some reports estimating a 75% increase in ED visits for mental health reasons for youth under the age of 24 in the last decade (34). In Quebec, the number of youth with ED visits for mental health reasons increased by 69% during the pandemic (35). Our findings are consistent with a previous literature review that reported that many youth (between 22% – 43%) presenting at the ED for mental health problems had current or prior experiences of child welfare involvement (36, 37). Given these high rates of ED use, their associated costs, and the fact that EDs are not designed as a youth-friendly entry into care, special attention must be paid to ensure that youth involved in CWS can access appropriate services prior to the emergence of a mental health crisis.

We also noted the relatively high use of mental health contacts being made in private settings for youth during their involvement with child welfare. These services were most often initiated by judges involved in the youth’s case. Judge-initiated care is commonly mandated to occur within a certain time frame, and public services often fail to provide services within these timelines. As such, private sector services are utilized by CWS to ensure that treatment or evaluations are provided within court-mandated timeframes. This may represent an inability of the of the public health system to meet demands, resulting in government-funded child welfare services having to resort to expensive private services.

Timing of contacts with mental health services

In three US-based studies, involvement with welfare agencies appeared to trigger or arguably facilitate entry to mental health services, with studies showing a significant increase in the use of mental health services immediately after initial contact with child welfare services (1, 38, 39). The immediate impact on mental health service use upon CWS involvement has thus far not been examined in the Canadian context. Our study replicated the findings from a prior study (39) which revealed an increase in mental health service use around the commencement of the CWS involvement. Our findings expanded on this research by showing that mental health service use increases steadily in the two months prior to the beginning of child welfare involvement, then reaches a peak during the first month of child welfare involvement, and decreases thereafter, with rates of mental service use after three months of child welfare involvement being only slightly higher than pre- child welfare rates. The rise in mental health contacts prior to child welfare involvement may be explained by a pre-existing need for mental health services among these youth. Previous research has demonstrated that existing psychological problems may increase youths’ involvement with child welfare (4, 40) ). Another study noted that the need for mental health services was the strongest predictor of youths’ eventual placement in the foster care system (41).

The peak in contacts just following the commencement of child welfare involvement may be related to early scrutiny of youths’ well-being as part of the initial investigation by child welfare workers. One survey from the US revealed that many youth were placed in the custody of child welfare services by their parents in order to receive mental health services (42). Our analysis also revealed that the initial referral to child welfare was made on the same day as many mental health contacts, notably at the ED, suggesting that healthcare services may have played a role in reporting youth to child welfare, reinforcing the importance of a strong relationship between child welfare and healthcare settings (43), and the need for communication and collaboration amongst health and social service sectors. Healthcare professionals play an important role in reporting to child welfare services(44)

Stakeholders involved in initiating care

Our study provided a novel examination of who initiates mental health services for this population. Notably, a wide range of actors were involved in initiating contact, including schools, judges, police, parents and others. This is particularly significant because child welfare workers are often viewed as “brokers” for services needed by youth in child welfare services (45), and youth involved with child welfare services have been considered ‘help-receivers’, whose decisions regarding healthcare are made for them by others (46). However, the help-seeking ability of these youth is of particular importance, given that help-seeking skills can be vital once their involvement with child welfare ceases at age 18 (47). A recent survey out of Quebec showed that mental health needs of child welfare-involved youth increased after they aged out of the system (22), yet others have shown that mental health service use can drop by as much as 60% once youth age out of care (48).

In our sample, 24% of youth had themselves initiated contact with mental health services at least once. This finding adds to the growing impetus to implement interventions to increase help-seeking behaviours for youth in child welfare systems (49). The top reason for which youth themselves initiated contact was for substance use problems. This finding is salient given prior evidence that youth are reluctant to seek help for substance use disorders, with youth help-seeking rates for substance use being lower than those for other psychiatric conditions (50–52). Our finding may be explained by the fact that in Quebec, substance use clinics specifically target outreach activities at child welfare systems so that youth in need are identified earlier (53). Altogether, this may suggest that broader-spectrum early identification interventions should specifically target youth in child welfare services.

Multi-setting use

Many youth had contacts with mental health services across multiple settings over the course of their involvement with the CWS. This is consistent with studies from youth in the general population, who often present to a multitude of medical and social service sectors for mental health problems (54, 55). The use of mental health services from different settings may reflect the natural course of mental health problems and the changing needs or desires of youth. On the other hand, it may also reflect a poor response to treatment, disengagement with care, a failure to appropriately assess and respond to a young person’s needs or poor coordination between settings. In all cases, the combination of services from different settings provides an impetus for increased collaboration between the settings that interact and serve youth involved with child welfare agencies. Intersectoral collaboration and continuity of care is a matter of considerable importance for all youth. Youth experiencing multiple transitions through care have described the experience as ‘overwhelming’, due to lack of preparation and uncertainties (56). Such experiences may be particularly salient for child-welfare-involved youth, whose frequent exposure to multiple placements, and transitions to multiple health and social service providers, can have important negative consequences (57).

Emergency departments, schools, and hospital outpatient settings were the most common points of service receipt for youth in child welfare services, reinforcing the importance of strengthening the collaboration between these settings and child welfare agencies. Schools in particular may be well equipped to support early identification efforts and entry into services (58). Strengthened linkages between ED personnel and child welfare agencies could facilitate coordinated discharge planning and increase the likelihood of recommended outpatient follow-up. Such measures, characterized by better communication, shared policy development, formalized collaborative agreements, and cohesive treatment philosophies and goals, have been linked to greater service use and better mental health outcomes for young people in child welfare (59).

In our sample, higher numbers of placements were linked to an increased likelihood of multi-setting contacts for mental health problems. Placements changes have previously been linked to greater rates of outpatient service use (60) and higher rates of ED visits (61). It has been suggested that higher rates of mental health issues are a predictor of placement instability (62, 63) while others have noted that disruptive placement changes can themselves negatively impact a young person’s emotional and mental health (62–65). Notwithstanding our inability to tease these two possibilities apart, our findings point to the reality that many youth in the CWS experience a multitude of disruptions, in both home and healthcare environments. This is particularly critical as strong evidence exists for the importance of continuity of attachment ties for youth in welfare services (66), including continuity in healthcare (67). Evidence also suggests that preventing placement instability can improve mental health outcomes for youth and their need for emergency mental health care (61). Interestingly, one successful pilot project was associated with reduced placements within child welfare by making a mental health clinician available on site at two foster care agencies (68).

Social determinants

The rate of visible minority youth in our sample (53%) far exceeds the expected rate of 28%, based on census data from our two catchment-area based populations (69). Racial disproportionality within child welfare systems has been the subject of multiple studies emerging out of Canada (70–74). There is a need to acknowledge that the historical legacies of social policies and institutional practices within Canada have placed a disproportionate burden on specific visible minority and immigrant communities, and that these legacies continue to affect youth and families in Canada today. While further examination of this matter is crucial, it should also be noted that many of these issues, including specifically anti-Black and anti-Indigenous racism within child welfare services in Canada, have been decried for over two decades (70, 75–77).

Limitations

One limitation of this study is the reliance on case files, as there are inherent limitations in what is being documented. For example, notes contain a lack of information on clinical severity, precluding any examination of whether youth with greater clinical needs were seen more frequently, or in greater numbers of settings. We were also unable to gather information on all possible organizations providing care for young people, including in the community sector. Our sample size also limited our power to test other variables which may be associated with patterns of service use, such as stakeholders involved in initiating care, and reasons for needing mental health services.

Overall, our findings suggest that the organization of health and social services in Quebec does not necessarily translate into service users having access to coordinated, integrated services with strong continuity of care, even for those connected to services such as child welfare. Many factors are known to prevent the coordination of services, including the reluctance to share resources, defending professional territoriality through specialization and the designation of professional acts, and the scarcity of financial resources and their inefficient use (78). These factors are intrinsically linked to a need to strengthen integrated youth mental health services globally. Integrated services, which are gaining traction across different healthcare jurisdictions across the world (79, 80), aim to address the broader issues of service gaps, lack of inter-sectorial collaboration, and concomitant service use by providing one-stop mental health services for youth with varying needs. These types of integrated services may greatly benefit youth involved with child welfare services, who have diverse needs and already present to multiple different settings. By integrating services at a systemic level, the broad range of needs that many youths in child welfare services may be addressed more cohesively. This will however require the commitment of key stakeholders, such as, for example, through specific partnerships between integrated youth services and child welfare agencies and continuous evaluation of the effectiveness of such partnerships in terms of improved pathways and outcomes.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding sources: The project was carried out under the aegis of ACCESS Open Minds, which is a Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR) network funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Grant number: 01308-000) and the Graham Boeckh Foundation.

References

- 1.Burns BJ, Phillips SD, Wagner HR, Barth RP, Kolko DJ, Campbell Y, et al. Mental health need and access to mental health services by youths involved with child welfare: A national survey. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43(8):960–70. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000127590.95585.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McMillen JC, Zima TB, Scott DL, Jr, Auslander WF, Munson MR, Ollie TM, et al. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among older youths in the foster care system. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44(1):88–95. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000145806.24274.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Polanczyk GV, Salum GA, Sugaya LS, Caye A, Rohde LA. Annual research review: A meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry. 2015;56(3):345–65. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Engler AD, Sarpong KO, Van Horne BS, Greeley CS, Keefe RJ. A systematic review of mental health disorders of children in foster care. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2022;23(1):255–64. doi: 10.1177/1524838020941197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clausen JM, Landsverk J, Ganger W, Chadwick D, Litrownik A. Mental health problems of children in foster care. Journal of child and family studies. 1998;7(3):283–96. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pilowsky D. Psychopathology among children placed in family foster care. Psychiatric services. 1995 doi: 10.1176/ps.46.9.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berrick JD, Barth RP, Needell B. A comparison of kinship foster homes and foster family homes: Implications for kinship foster care as family preservation. Children and Youth Services Review. 1994;16(1–2):33–63. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farmer EM, Burns BJ, Chapman MV, Phillips SD, Angold A, Costello EJ. Use of mental health services by youth in contact with social services. Social Service Review. 2001;75(4):605–24. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bunger AC, Chuang E, McBeath B. Facilitating mental health service use for caregivers: Referral strategies among child welfare caseworkers. Children and youth services review. 2012;34(4):696–703. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marcenko MO, Hook JL, Romich JL, Lee JS. Multiple jeopardy: Poor, economically disconnected, and child welfare involved. Child Maltreatment. 2012;17(3):195–206. doi: 10.1177/1077559512456737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wherry JN, Huey CC, Medford EA. A national survey of child advocacy center directors regarding knowledge of assessment, treatment referral, and training needs in physical and sexual abuse. Journal of child sexual abuse. 2015;24(3):280–99. doi: 10.1080/10538712.2015.1009606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Courtney ME, Charles P. Mental health and substance use problems and service utilization by transition-age foster youth: Early findings from CalYOUTH. Chicago, IL: Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Racine N, Dimitropoulos G, Hartwick C, Eirich R, van Roessel L, Madigan S. Characteristics and service needs of maltreated children referred for mental health services at a child advocacy centre in Canada. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2021;30(2):92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farmer EM, Mustillo SA, Wagner HR, Burns BJ, Kolko DJ, Barth RP, et al. Service use and multi-sector use for mental health problems by youth in contact with child welfare. Children and Youth Services Review. 2010;32(6):815–21. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finno-Velasquez M, Cardoso JB, Dettlaff AJ, Hurlburt MS. Effects of parent immigration status on mental health service use among Latino children referred to child welfare. Psychiatric Services. 2016;67(2):192–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garland AF, Aarons GA, Brown SA, Wood PA, Hough RL. Diagnostic profiles associated with use of mental health and substance abuse services among high-risk youths. Psychiatric Services. 2003;54(4):562–4. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.4.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blumberg E, Landsverk J, Ellis-MacLeod E, Ganger W, Culver S. Use of the public mental health system by children in foster care: Client characteristics and service use patterns. The journal of mental health administration. 1996;23(4):389–405. doi: 10.1007/BF02521024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kolko DJ, Baumann BL, Caldwell N. Child abuse victims’ involvement in community agency treatment: Service correlates, short-term outcomes, and relationship to reabuse. Child Maltreatment. 2003;8(4):273–87. doi: 10.1177/1077559503257101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kolko DJ, Selelyo J, Brown EJ. The treatment histories and service involvement of physically and sexually abusive families: Description, correspondence, and clinical correlates. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1999;23(5):459–76. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim M, Garcia AR, Yang S, Jung N. Area-socioeconomic disparities in mental health service use among children involved in the child welfare system. Child abuse & neglect. 2018;82:59–71. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenheck RA, Resnick SG, Morrissey JP. Closing service system gaps for homeless clients with a dual diagnosis: Integrated teams and interagency cooperation. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics. 2003;6(2):77–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goyette M, Blanchet A, Bellot C. The Covid-19 pandemic and needs of youth who leave care. Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trocmé N, Roy C, Esposito T. Building research capacity in child welfare in Canada. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health. 2016;10(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s13034-016-0103-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moroz N, Moroz I, D’Angelo MS, editors. Healthcare management forum. SAGE Publications Sage CA; Los Angeles, CA: 2020. Mental health services in Canada: barriers and cost-effective solutions to increase access. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Canadian Mental Health Association. Mental health in the balance: Ending the health care disparity in Canada. Canadian Mental Health Association; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacDonald K, Laporte L, Desrosiers L, Iyer SN. Emergency Department Use for Mental Health Problems by Youth in Child Welfare Services. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2022;31(4) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nichols N, Schwan K, Gaetz S, Redman M, French D, Kidd S, et al. Child Welfare and Youth Homelessness in Canada. Toronto, Canada: Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iyer SN, Shah J, Boksa P, Lal S, Joober R, Andersson N, et al. A minimum evaluation protocol and stepped-wedge cluster randomized trial of ACCESS Open Minds, a large Canadian youth mental health services transformation project. BMC psychiatry. 2019;19(1):1–17. doi: 10.1186/s12888-019-2232-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and psychological measurement. 1960;20(1):37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lavergne C, Clément M, Cloutier R. PIBE ou la création d’une fenêtre sur des données de recherche dans le domaine de la protection des enfants au Québec. Intervention. 2005;122(1):31–41. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nelson PR, Wludyka PS, Copeland KA. The analysis of means: a graphical method for comparing means, rates, and proportions. Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Killick R, Eckley I. changepoint: An R package for changepoint analysis. Journal of statistical software. 2014;58(3):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wiens K, Bhattarai A, Pedram P, Dores A, Williams J, Bulloch A, et al. A growing need for youth mental health services in Canada: examining trends in youth mental health from 2011 to 2018. Epidemiology and psychiatric sciences. 2020:29. doi: 10.1017/S2045796020000281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paltser G, Martin-Rhee M, Cheng C, Wagar B, Gregory J, Paillé B, et al. Care for Children and Youth with Mental Disorders in Canada. Healthcare quarterly (Toronto, Ont) 2016;19(1):10–2. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2016.24616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chadi N, Ryan NC, Geoffroy M-C. COVID-19 and the impacts on youth mental health: Emerging evidence from longitudinal studies. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2022;113(1):44–52. doi: 10.17269/s41997-021-00567-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chatagner A, Olliac B, Lh C, Botbol M, Raynaud J. Teenagers urgently received in child and adolescent psychiatry: Who are they? What about their trajectories? What social and/or judicial support. Neuropsyc Enfance Adolesc. 2015;63:124–32. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chatagner A, Raynaud J-P. Adolescents et urgences pédopsychiatriques: revue de la littérature et réflexion clinique. Neuropsychiatrie de l’enfance et de l’adolescence. 2013;61(1):8–16. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bellamy JL, Gopalan G, Traube DE. A national study of the impact of outpatient mental health services for children in long-term foster care. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010;15(4):467–79. doi: 10.1177/1359104510377720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leslie LK, Hurlburt MS, James S, Landsverk J, Slymen DJ, Zhang J. Relationship between entry into child welfare and mental health service use. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56(8):981–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.8.981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McMillen JC, Scott LD, Zima BT, Ollie MT, Munson MR, Spitznagel E. Use of mental health services among older youths in foster care. Psychiatric Services. 2004;55(7):811–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.7.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Glisson C, Green P. The effects of organizational culture and climate on the access to mental health care in child welfare and juvenile justice systems. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2006;33(4):433. doi: 10.1007/s10488-005-0016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Child Welfare and Juvenile Justice. Federal agencies should play a stronger role in helping states reduce the number of children placed solely to obtain mental health services. Washington, DC: US General Accounting Office. Washington, DC, General Accounting Office; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Joh-Carnella N, Livingston E, Kagan-Cassidy M, Vandermorris A, Smith JN, Lindberg DM, et al. Understanding the roles of the healthcare and child welfare systems in promoting the safety and well-being of children. Frontiers in psychiatry. 2023;14:1195440. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1195440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.King B, Lawson J, Putnam-Hornstein E. Examining the evidence: reporter identity, allegation type, and sociodemographic characteristics as predictors of maltreatment substantiation. Child maltreatment. 2013;18(4):232–44. doi: 10.1177/1077559513508001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dorsey S, Kerns SE, Trupin EW, Conover KL, Berliner L. Child welfare caseworkers as service brokers for youth in foster care: Findings from project focus. Child maltreatment. 2012;17(1):22–31. doi: 10.1177/1077559511429593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Unrau YA, Conrady-Brown M, Zosky D, Grinnell RM., Jr Connecting youth in foster care with needed mental health services: Lessons from research on help-seeking. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work. 2006;3(2):91–109. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Unrau YA, Grinnell RM., Jr Exploring out-of-home placement as a moderator of help-seeking behavior among adolescents who are high risk. Research on Social Work Practice. 2005;15(6):516–30. [Google Scholar]

- 48.McMillen JC, Raghavan R. Pediatric to adult mental health service use of young people leaving the foster care system. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;44(1):7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Blakeslee JE, Kothari BH, Miller RA. Intervention development to improve foster youth mental health by targeting coping self-efficacy and help-seeking. Children and Youth Services Review. 2023;144:106753. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2022.106753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Merikangas KR, He J-p, Burstein M, Swendsen J, Avenevoli S, Case B, et al. Service utilization for lifetime mental disorders in US adolescents: results of the National Comorbidity Survey–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;50(1):32–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reavley NJ, Cvetkovski S, Jorm AF, Lubman DI. Help-seeking for substance use, anxiety and affective disorders among young people: results from the 2007 Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;44(8):729–35. doi: 10.3109/00048671003705458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Winstanley EL, Steinwachs DM, Stitzer ML, Fishman MJ. Adolescent substance abuse and mental health: problem co-occurrence and access to services. Journal of Child & Adolescent substance abuse. 2012;21(4):310–22. doi: 10.1080/1067828X.2012.709453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Programme Accès Jeunesse en Toxicomanie (PAJT) Québec:Régie régionale de la santé et des services sociaux de Québec. 2001. p. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reid GJ, Cunningham CE, Tobon JI, Evans B, Stewart M, Brown JB, et al. Help-seeking for children with mental health problems: Parents’ efforts and experiences. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2011;38(5):384–97. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0325-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.MacDonald K, Fainman-Adelman N, Anderson KK, Iyer SN. Pathways to mental health services for young people: a systematic review. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology. 2018;53(10):1005–38. doi: 10.1007/s00127-018-1578-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kokorelias KM, Lee T-SJ, Bayley M, Seto E, Toulany A, Nelson ML, et al. “I Have Eight Different Files at Eight Different Places”: Perspectives of Youths and Their Family Caregivers on Transitioning from Pediatric to Adult Rehabilitation and Community Services. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023;12(4):1693. doi: 10.3390/jcm12041693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Havlicek J. Patterns of movement in foster care: An optimal matching analysis. Social Service Review. 2010;84(3):403–35. doi: 10.1086/656308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dimitropoulos G, Cullen E, Cullen O, Pawluk C, McLuckie A, Patten S, et al. “Teachers often see the red flags first”: perceptions of school staff regarding their roles in supporting students with mental health concerns. School mental health. 2021:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bai Y, Wells R, Hillemeier MM. Coordination between child welfare agencies and mental health service providers, children’s service use, and outcomes. Child abuse & neglect. 2009;33(6):372–81. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.James S, Landsverk J, Slymen DJ, Leslie LK. Predictors of outpatient mental health service use—the role of foster care placement change. Mental health services research. 2004;6(3):127–41. doi: 10.1023/b:mhsr.0000036487.39001.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fawley-King K, Snowden LR. Relationship between placement change during foster care and utilization of emergency mental health services. Children and Youth Services Review. 2012;34(2):348–53. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Newton RR, Litrownik AJ, Landsverk JA. Children and youth in foster care: Disentangling the relationship between problem behaviors and number of placements. Child abuse & neglect. 2000;24(10):1363–74. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(00)00189-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Barber JG, Delfabbro PH. Placement stability and the psychosocial well-being of children in foster care. Research on Social Work Practice. 2003;13(4):415–31. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rubin DM, O’Reilly AL, Luan X, Localio AR. The impact of placement stability on behavioral well-being for children in foster care. Pediatrics. 2007;119(2):336–44. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rubin DM, Alessandrini EA, Feudtner C, Mandell DS, Localio AR, Hadley T. Placement stability and mental health costs for children in foster care. Pediatrics. 2004;113(5):1336–41. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.5.1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gauthier Y, Fortin G, Jéliu G. Clinical application of attachment theory in permanency planning for children in foster care: The importance of continuity of care. Infant Mental Health Journal: Official Publication of The World Association for Infant Mental Health. 2004;25(4):379–96. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Holland S, Faulkner A, Perez-del-Aguila R. Promoting stability and continuity of care for looked after children: a survey and critical review. Child & Family Social Work. 2005;10(1):29–41. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Collado C, Levine P. Reducing transfers of children in family foster care through onsite mental health interventions. Child welfare. 2007;86(5):133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Statistics Canada. Census of Population, geographic summary. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ma J, Fallon B, Richard K. The overrepresentation of First Nations children and families involved with child welfare: Findings from the Ontario incidence study of reported child abuse and neglect 2013. Child abuse & neglect. 2019;90:52–65. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Antwi-Boasiako K, King B, Fallon B, Trocme N, Fluke J, Chabot M, et al. Differences and disparities over time: Black and White families investigated by Ontario’s child welfare system. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2020;107:104618. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.King B, Fallon B, Boyd R, Black T, Antwi-Boasiako K, O’Connor C. Factors associated with racial differences in child welfare investigative decision-making in Ontario, Canada. Child abuse & neglect. 2017;73:89–105. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Akuoko-Barfi C, McDermott T, Parada H, Edwards T. “We Were in White Homes as Black Children:” Caribbean Youth’s Stories of Out-of-home Care in Ontario, Canada. Journal of Progressive Human Services. 2021:1–31. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mohamud F, Edwards T, Antwi-Boasiako K, William K, King J, Igor E, et al. Racial disparity in the Ontario child welfare system: Conceptualizing policies and practices that drive involvement for Black families. Children and Youth Services Review. 2021;120:105711. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pon G, Gosine K, Phillips D. Immediate response: Addressing anti-Native and anti-Black racism in child welfare. International Journal of Child, Youth and Family Studies. 2011;2(3/4):385–409. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Blackstock C, Trocmé N, Bennett M. Child maltreatment investigations among Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal families in Canada. Violence against women. 2004;10(8):901–16. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Trocmé N, Knoke D, Blackstock C. Pathways to the overrepresentation of Aboriginal children in Canada’s child welfare system. Social Service Review. 2004;78(4):577–600. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ross T. Child welfare: The challenges of collaboration. The Urban Insitute; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Halsall T, Manion I, Iyer SN, Mathias S, Purcell R, Henderson J, editors. Healthcare management forum. SAGE Publications; Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA: 2019. Trends in mental health system transformation: Integrating youth services within the Canadian context. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hetrick SE, Bailey AP, Smith KE, Malla A, Mathias S, Singh SP, et al. Integrated (one-stop shop) youth health care: Best available evidence and future directions. Medical Journal of Australia. 2017;207(S10):S5–S18. doi: 10.5694/mja17.00694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]