Abstract

Background

Endometriosis is a chronic and debilitating disease that can affect the entire reproductive life course of women, with potential adverse effects on pregnancy. The aim of the present study is to investigate the association between hypertensive disorders in pregnancy and endometriosis.

Method

Relevant articles were searched from the Cochrane Library, PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science from inception up to December 2023. The full-text observational studies published in English that had a confirmed diagnosis of endometriosis were included. The case group included pregnant women diagnosed with endometriosis at any stage, while the control group consisted of pregnant women who had not been previously diagnosed with endometriosis. Two authors extracted and analyzed the data independently. Disagreements were reconciled by reviewing the full text by a third author. Endnote X9 was used for screening and data extraction. We used fixed and random effects models in Review Manager 5.3 to analyze the pooled data. The quality of the included studies was assessed using the Downs and Black checklist.

Results

Out of the 9863 articles reviewed, 23 were selected for meta-analysis. According to the results of this study, there was an association between endometriosis and gestational hypertension (OR = 1.11, 95% CI: 1.06, 1.16; I2 = 45%, P < 0.00001; N = 8), pre-eclampsia (OR = 1.26, 95% CI: 1.18, 1.36; I2 = 37%, P < 0.00001; N = 12), and hypertensive disorders in pregnancy (OR = 1.13, 95% CI: 1.06, 1.21; I2 = 8%, P = 0.0001; N = 8).

Conclusions

This study confirmed that endometriosis may elevate the risk of developing gestational hypertensive disorders. Raising awareness of this issue will help to identify effective strategies for screening and early diagnosis of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy.

Keywords: Endometriosis, Gestational hypertension, Preeclampsia, Systematic review

Introduction

Endometriosis is a chronic gynecological disease characterized by the presence and growth of estrogen-dependent endometrial structures outside the uterine cavity, particularly on ovaries, fallopian tubes, pelvic peritoneum, and uterosacral ligaments [1]. Pelvic pain and infertility are the most common symptoms of affected women, occurring in 10–15% of women of reproductive age [2]. In the diagnosis of endometriosis based on ESHER guidelines, the presence of clinical symptoms, along with symptoms detected in clinical examinations and imaging (MRI and ultrasound) are used, and in case of suspicion of peritoneal endometriosis, laparoscopy is used for definitive diagnosis along with histological examination [3]. Clinical symptoms of endometriosis include abnormal bowel movements, intestinal dysfunction, dyspareunia, lower abdominal pain, severe dysmenorrhea, and infertility [4]. On the other hand, the prevalence of psychological disorders such as anxiety and depression is reported high in affected women [5]. Surgical excision of the lesion is a common treatment method that can alleviate pain and greatly enhance quality of life [6]. Of course, in some cases, recurrence of the disease has been reported [7].

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (chronic hypertension, gestational hypertension, and pre-eclampsia) are so prevalent throughout the world and can lead to serious consequences for both the mother and the baby [8]. The global prevalence of this disorder is almost 116 per 100,000 women of reproductive age. However, it varies depending on the region [9]. Current risk factors for hypertensive disorders include primigravida, increasing age, pre-pregnancy obesity, twin or multiple pregnancy, and some chronic diseases like polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOs), overt diabetes, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and autoimmune disease [10]. Although the relationship between endometriosis and hypertensive disorders is not clearly defined, these two conditions seem to follow the same pathophysiological mechanisms.

Endometriosis is known as an immunological and chronic inflammatory disease [11]. It has been shown that the concentration of immunological and inflammatory factors such as macrophages, natural killer cells (NK cells), cytokines, B and T lymphocytes, growth factors, and angiogenesis stimulants is higher in women with endometriosis [10, 12], which can impede maternal and fetal adaptation with the normal changes of pregnancy. Additionally, a variety of immune cells and mediators have been associated with the onset of preeclampsia, a condition in which oxidative stress is linked to activation of the maternal inflammatory response. Immune cells such as regulatory T cells, macrophages, NK cells, and neutrophils are known to contribute significantly to the pathology of preeclampsia [13]. The interference caused by inflammatory and immunological responses can have a detrimental effect on trophoblast invasion and placental implantation that occurs by affecting the decidua and the placenta, which are crucial components of the process [14]. Defects in placental invasion or inappropriate remodeling of uterine spiral arteries can lead to blood pressure disorders in pregnancy [15]. Therefore, it seems that inflammatory and immunological factors play a role in pathogenesis of these two conditions and that they can affect each other.

However, the evidence regarding the link between hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and endometriosis seems to be conflicting. While some studies have shown a significant association between the two [16], others have suggested the opposite [17]. Moreover, some have found no relationship between these two conditions [18]. This disparity in results may stem from differences in study methodologies, sample sizes, endometriosis severity and location, or the presence of selection bias. Therefore, it is important to elucidate the role of endometriosis as a predictor of subsequent hypertensive disorders in patients with endometriosis who conceived spontaneously. The aim of the current systematic review was to investigate the potential link between hypertensive disorders during pregnancy and endometriosis.

Material and methods

Study protocol

This systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [19]. The protocol of this systematic review was registered in PROSPERO (Ref No: CRD 42024498946).

Search strategy

In this review, we included studies published in databases from inception up to December 2023. Systematic searches were performed on PubMed, Scopus, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science using MeSH keywords and terms. The keywords used were “Endometriosis” along with “Preeclampsia” and “Hypertension of pregnancy”.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The selection of relevant studies was according to the following inclusion criteria: observational studies (case–control, cross-sectional, or cohort) and studies published in English. Studies written in local languages or with qualitative, review, and interventional designs, case report studies, congress presentations, or study protocols were excluded from this review. Furthermore, studies without a clear statement about the diagnosis of endometriosis, those lacking data on exposure or outcome, and those whose full text was not available were also excluded.

All the included studies had a confirmed diagnosis of endometriosis either by the presence of lesions during surgery (with or without histological confirmation), by imaging modality, or by International Classification of Disease (ICD)-coded medical records in women who conceived spontaneously. Due to the higher risk of obstetric complications such as pregnancy-induced hypertension and preeclampsia associated with pregnancies conceived through ART [20], we excluded studies on these topics in order to eliminate their potential impact on the relationship between endometriosis and hypertensive disorders. Diagnosis of the gestational hypertension was defined as a systolic blood pressure of ≥ 140 mmHg or a diastolic blood pressure of ≥ 90 mmHg after 20 weeks of gestation or based on definition of International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 8, 9, 10 codes for gestational hypertensive disorders or etc.

Study participants

The case group in this study included pregnant women diagnosed with endometriosis at any stage or severity, while the control group consisted of pregnant women who had not been previously diagnosed with endometriosis. All the studies included in the review involved only women who had conceived naturally. Women who had become pregnant using in vitro fertilization were excluded from the study.

Types of outcome measures

Outcomes of this study were the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy including pre-eclampsia and gestational hypertension.

Study selection and data extraction

FSH and SHF conducted a search on the databases and screened the titles and abstracts of the search results based on specific criteria. They independently extracted data from eligible full texts. In case of any discrepancies or conflicts, a third author was consulted to resolve the issue. Endnote X9 was used for screening and data extraction. A table was created for data extraction, and the following pieces of information were extracted: study author’s name, study location, study type, participants’ age, sample size of the control and case groups, definitions of PIH and endometriosis, and outcomes.

Assessment of study quality

FSH and SHF evaluated the quality of the studies included in the research using the checklist of Downs and Black (1998). The checklist comprised of twenty-seven questions that evaluated various areas. It included ten questions for assessing reporting bias, three for assessing external validity, seven for evaluating internal validity, six for assessing selection bias, and one question for assessing the power of the study [21]. The total quality score was classified as follows: a score of less than 14 was considered poor, a score between 15 and 19 was considered fair, and a score more than 20 was considered good [22].

Statistical analysis

We conducted a meta-analysis using Review Manager version 5.4 (RevMan 5.4; Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK) and set the significance level at less than 0.05. Mean differences (MD) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were used to compare variables between groups. We used a fixed-effect meta-analysis to combine the mean differences of each study and demonstrated effect sizes and 95% CI using forest plots. We measured heterogeneity using I2, where an I2 value of 0–50% indicated low or moderate heterogeneity, and I2 > 50% indicated substantial heterogeneity. We used the random effects model when I2 > 50%. We conducted a sensitivity analysis to investigate potential sources of heterogeneity in case there was statistically significant heterogeneity across studies. In the sensitivity analyses, we systematically excluded one study at a time to test the strength of uncertainty in the meta-analysis [23]. We also statistically evaluated potential publication biases using funnel plots and Begg’s and Egger’s tests using STATA [24]. A funnel plot was used to assess publication bias whenever there were more than ten studies in the meta-analysis [25].

Results

Study selection

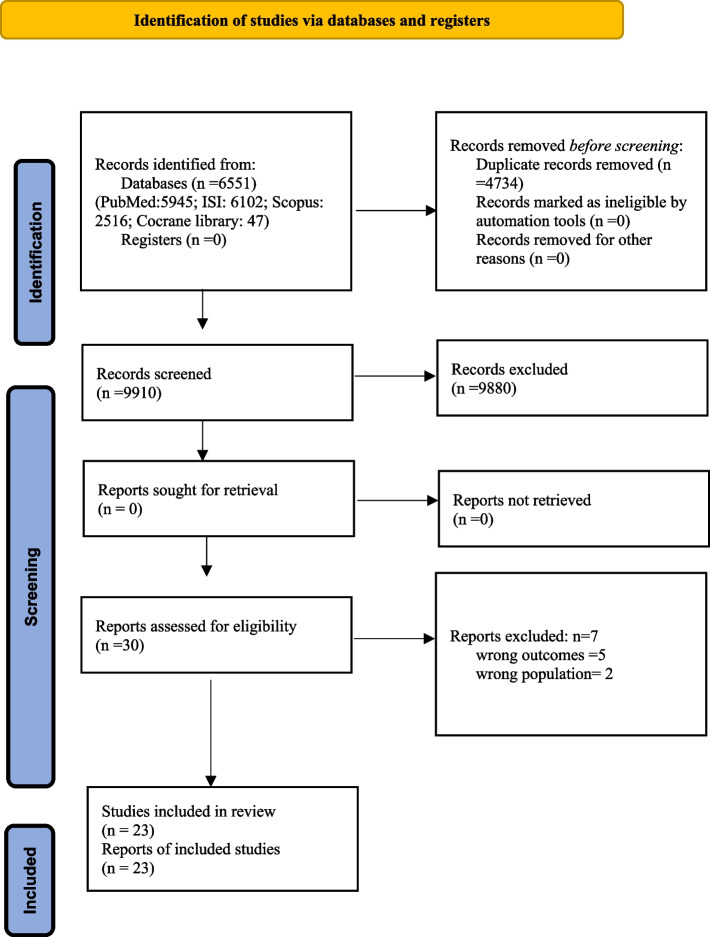

We obtained 14610 publications via the electronic search strategy (Web of Sciences: 6102; PubMed: 5945; Scopus; 2516; Cochrane Library: 47) from inception to 15 December 2023. Of these publications, 4734 duplicates were removed, and 9910 were subjected to title and abstract screening. Thirty articles were selected for eligibility at full-text review of which, 23 were eligible to be included in this review. Figure 1 shows the flowchart of the study.

Fig. 1.

The flow diagram of the systematic review for selection of the studie

Study characteristics

Description of the studies is shown in Table 1. The reviewed observational studies included cohort studies (13 papers), case–control studies (7 papers), and longitudinal design (3 papers). As far as the country of origin of the studies was concerned, four were performed in Italy [26–29], three in Japan [30–32], three in China [6, 33, 34], three in Australia [18, 35, 36], two in the UK [17, 37], two in Denmark [38, 39], two in the USA [40, 41], one in France [42], one in Taiwan [10], one in Sweden [16], and one in Canada [43]. The number of participants in the studies varied from 40 to 1,429,585. In all studies, women of reproductive age were included. The diagnosis of endometriosis in the included studies was based on the results of laparoscopy, surgery, diagnosis code of International Classification of Diseases ICD 9—ICD10, or imaging. In this review, 133,941 women with endometriosis were compared with 8,932,888 healthy women in terms of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Table 2 shows the definitions of hypertensive disorders and endometriosis across all included studies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the systematic review

| No | Study | Location | Study type | Age (y); mean ± SD | No. of participants | Gravidity of participants | Main outcomes: N (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Control | Case | Control | Case | Control | |||||

| 1 | Brosens et al. 2007 [17] | UK | Retrospective case–control study | 32 (21– 44) | 33 (20– 44) | 245 | 274 | Nulliparous and multiparous | Pre-eclampsia | |

| 2 (0.8%) | 16 (5.8%) | |||||||||

| 2 | Berlac et al. 2017 [38] | Denmark | National cohort study | 31.4 | 30.4 | 11 739 | 615 533 | Nulliparous and multiparous | Hypertension | |

| 404 (2.1%) | 18984 (1.8%) | |||||||||

| Pre-eclampsia | ||||||||||

| 588(3.0%) | 23 625 (2.2%) | |||||||||

| 3 | Conti et al. 2015 [26] | Italy | Cohort study | - | - | 219 | 1331 | Nulliparous and multiparous | Gestational hypertension | |

| 8 (3.7%) | 77 (5.8%) | |||||||||

| Preeclampsia | ||||||||||

| 5 (2.2%) | 16 (1.2%) | |||||||||

| 4 | Epelboin et al. 2021 [42] | France | Longitudinal study | 31.7 ± 4.8 | 30.0 ± 5.3 | 31,101 | 4,083,732 | Nulliparous and multiparous | Preeclampsia | |

| 679 (2.18%) | 64,288 (1.57%) | |||||||||

| 5 | Farland et al. 2019 [40] | USA | Prospective cohort study | 29.1 ± 5.3 | 29.1 ± 5.3 | 8,875 | 187,847 | Nulliparous and multiparous | Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy | |

| 541/5,665 (9.5%) | 8,730/131,970 (6.6%) | |||||||||

| 6 | Farland et al. 2022 [41] | USA | Cohort study | 33.0 ± 4.03 | 34.54 ± 4.23 | 1,560 | 73,868 | Nulliparous and multiparous | PIH/Pre-eclampsia | |

| 213 (13.7%) | 9,440 (10.5%) | |||||||||

| 7 | Gebremedhin et al. 2023 [35] | Australia | Population-based retrospective cohort study | 15–49 | 15–49 | 19,476 | 893,271 | Nulliparous and multiparous | Preeclampsia | |

| 1468 (7.5%) | 54,098 (6.1%) | |||||||||

| 8 | Glavind et al. 2017 [39] | Denmark | Danish cohort study | 30–34 | 25–29 | 1,719 | 81,074 | Nulliparous and multiparous | Pre-eclampsia | |

| 89 (5.18%) | 3519 (4.34%) | |||||||||

| 9 | Hadfield et al. (2009) [18] | Australia | Population-based, longitudinal study | 31.4 ± 5.1 | 28.3 ± 5.7 | 3239 | 205 640 | Nulliparous and multiparous | Gestational hypertension | |

| 352(10.9%) | 23 186 (11.3%) | |||||||||

| Pre-eclampsia | ||||||||||

| 103 (3.2%) | 6564 (3.2%) | |||||||||

| 10 | Harada et al. (2016) [30] | Japan | Prospective cohort study | 15–45 | 15–45 | 330 | 8,856 | Nulliparous and multiparous | Pre-eclampsia | |

| 8 (2.4%) | 281(3.1%) | |||||||||

| 11 | Ibiebele et al. 2022 [36] | Australia | Population-based cohort study | 32.0 ± 5.1 | 29.7 ± 5.7 | 13 406 | 556922 | Nulliparous and multiparous | Pregnancy hypertension | |

| 1378 (10.3%) | 50 231 (9.0%) | |||||||||

| 12 | Lin et al. 2015 [33] | China | Retrospective cohort study | 32.8 ± 4.0 | 30.6 ± 3.5 | 249 | 249 | Nulliparous—multiparous | Pregnancy-induced hypertension | |

| 9 (3.6%) | 11 (4.4%) | |||||||||

| 13 | Liu et al. 2023 [6] | China | Retrospective study | 31.96 ± 4.38 | 31.75 ± 4.33 | 1026 | 2783 | Nulliparous and multiparous | Gestational hypertension | |

| 19 (1.85%) | 60 (2.16%) | |||||||||

| Preeclampsia | ||||||||||

| 38 (3.70%) | 61 (2.19%) | |||||||||

| 14 | Mekaru et al. 2013 [31] | Japan | Retrospective analysis | 33.0 ± 3.8 | 33.6 ± 4.1 | 49 | 59 | Nulliparous and multiparous | Pregnancy-induced hypertension | |

| 6 (15%) | 6 (12.5%) | |||||||||

| 15 | Miura et al. 2019 [32] | Japan | Case–control study | 34.2 ± 4.6 | 32.9 ± 5.2 | 80 | 2689 | Nulliparous and multiparous | Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy | |

| 4 (5.0%) | 187 (7.0%) | |||||||||

| 16 | Pan et al. 2017 [10] | Taiwan | Population-based longitudinal cohort study | 31.77 ± 5.76 | 31.77 ± 5.76 | 2578 | 10312 | Nulliparous and multiparous | Gestational hypertension-preeclampsia | |

| 100 (3.88%) | 168 (1.63%) | |||||||||

| 17 | Saraswat et al. 2016 [37] | UK | National population-based cohort study | 30.5 ± 5.2 | 27.2 ± 6.1 | 5375 | 8280 | Nulliparous and multiparous | Hypertensive disorders | |

| 350 (8.3%) | 452 (6.7%) | |||||||||

| 18 | Stephansson et al. 2009 [16] | Sweden | Population-based longitudinal study | < 20-> 35 | < 20- > 35 | 13 090 | 1 429 585 | Nulliparous and multiparous | Pre-eclampsia | |

| 441 (3.37%) | 41 377 (2.89%) | |||||||||

| 19 | Porpora et al. 2020 [27] | Italy | Prospective cohort study | 31(18–45) | 29(18–42) | 145 | 280 | Nulliparous women | Pregnancy induced hypertension | |

| 7 (5%) | 16 (6%) | |||||||||

| Preeclampsia | ||||||||||

| 3 (2%) | 2 (1%) | |||||||||

| 20 | Scala et al. 2019 [28] | Italy | Retrospect analysis | 30.2 (26.8–33) | 30.3(27–33) | 40 | 80 | Nulliparous and multiparous | Preeclampsia | |

| 9 (7.5%) | 6 (7.5%) | |||||||||

| 21 | Uccella et al. 2019 [29] | Italy | Retrospective case–control study | 34(22–45) | 31(15–48) | 118 | 1,690 | Nulliparous women | Hypertension/preeclampsia | |

| 13 (11%) | 99 (5.9%) | |||||||||

| 22 | Velez et al. 2022 [43] | Canada | Population-based cohort study | 32.95 ± 4.88 | 30.03 ± 5.6 | 19,099 | 768,350 | Nulliparous and multiparous | Hypertensive disorder | |

| 1042 (5.5%) | 37660 (4.9%) | |||||||||

| 23 | Xie et al. 2023 [34] | China | Case–control study | 30.96 ± 3.32 | 30.23 ± 2.98 | 188 | 188 | Nulliparous and multiparous | Hypertensive disorder in pregnancy | |

| 10 | 11 | |||||||||

Table 2.

Definition of hypertensive disorders and endometriosis in the included studies

| Study | Gravidity of participants | Definitions of PIH | Definitions of endometriosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brosens et al. 2007 [17] | Nulliparous and multiparous | Persistently raised blood pressure (140/90 mmHg) starting after the 20th week of gestation. Pre-eclampsia was defined as PIH with proteinuria (> 300 mg/24 h) | Laparoscopy |

| Berlac et al. 2017 [38] | Nulliparous and multiparous | International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 codes | women who underwent surgical interventions for their disease before pregnancy |

| Conti et al. 2015 [26] | Nulliparous and multiparous | Systolic blood pressure over 140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure over 90 mmHg after 20 weeks of gestation. preeclampsia: hypertension developing after 20 weeks of gestation with proteinuria | pathology following surgical removal of the lesions |

| Epelboin et al. 2021 [42] | Nulliparous and multiparous | - | The diagnosis of endometriosis was recorded if reported in previous hospitalizations since 2008 |

| Farland et al. 2019 [40] | Nulliparous and multiparous | self-report | Laparoscopy |

| Farland et al. 2022 [41] | Nulliparous and multiparous | ICD 9 and 10 codes | ICD9 and ICD10 codes |

| Gebremedhin et al. 2023 [35] | Nulliparous and multiparous | ICD-9/ICD-9-CM | ICD-9/10th revision-Australian Modification) |

| Glavind et al. 2017 [39] | Nulliparous and multiparous | using the relevant ICD-8 and ICD-10 from the Danish National Patient Registry | laparoscopic surgery |

| Hadfield et al. (2009) [18] | Nuliparous and multiparous | The ICD-10 codes used to define | The ICD-10 codes used to define |

| Harada et al. (2016) [30] | Nuliparous and multiparous |

as persistently raised blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mmHg, occurring after > 20 weeks Preeclampsia with severe features was defined as severe blood pressure elevation and severe proteinuria |

Questionnaire |

| Ibiebele et al. 2022 [36] | Nuliparous and multiparous | - | Australian modification (ICD10-AM) |

| Lin et al. 2015 [33] | Nulliparous—multiparous |

Elevated blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mmHg after 20 weeks of gestation Preeclampsia is gestational hypertension with proteinuria |

confirmed histologically and visually at the surgical procedure |

| Liu et al. 2023 [6] | Nulliparous and multiparous | ‘Hypertension in pregnancy’ was defined as a systolic blood pressure of ≥ 140 mmHg or a diastolic blood pressure of ≥ 90 mmHg. When measured with semiquantitative urine dipsticks, proteinuria of at least 1 + in the presence of hypertension, with no evidence of urinary tract infection, was considered significant | Diagnosis of endometriosis was done by laparoscopic examination, and the stage of endometriosis (was determined based on the revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine (rASRM) classification |

| Mekaru et al. 2013 [31] | Nulliparous and multiparous | - | laparoscopic evaluation |

| Miura et al. 2019 [32] | Nulliparous and multiparous | - | laparoscopy with histological confirmation |

| Pan et al. 2017 [10] | Nulliparous and multiparous | International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) | Surgical assessment by laparoscopy or laparotomy |

| Saraswat et al. 2016 [37] | Nulliparous and multiparous | - | surgically confirmed |

| Stephansson et al. 2009 [16] | Nulliparous and multiparous | ICD-9 codes | - |

| Porpora et al. 2020 [27] | Nulliparous women | - | surgical/histological or clinical /instrumental diagnosis of endometriosis |

| Scala et al. 2019 [28] | Nulliparous and multiparous | Gestational hypertension and concomitant proteinuria | Ultrasonographic diagnosis of endometriosis |

| Uccella et al. 2019 [29] | Nulliparous women | - | Pervious surgery |

| Velez et al. 2022 [43] | Nulliparous and multiparous | - | surgery with a diagnosis code of International Classification of Diseases ICD 9–617 or ICD10-N80 |

| Xie et al. 2023 [34] | Nulliparous and multiparous | Increase in blood pressure of ≥ 140/ 90 mmHg after 20 weeks of gestation. Preeclampsia is gestational hypertension with proteinuria | Histological examination |

Meta-analysis of outcomes

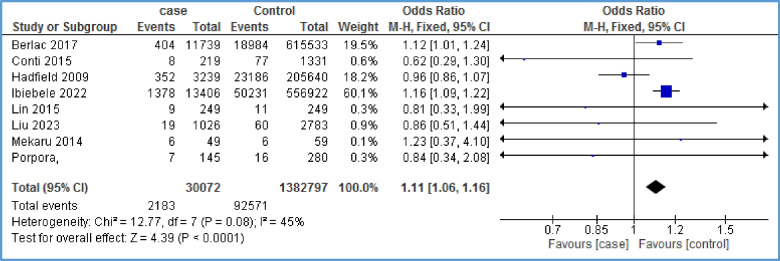

Gestational hypertension

The relationship between gestational hypertension and endometriosis was investigated in 8 studies [6, 18, 26, 27, 31, 33, 36, 38]. The evidence showed a positive and significant statistical relationship between the two mentioned variables (OR = 1.11, 95% CI: 1.06, 1.16; I2 = 45%, P < 0.0001; N = 8) (Fig. 2). Due to the limited number of papers on the relationship between gestational hypertension and endometriosis, it was not possible to generate a funnel plot.

Fig. 2.

Forest plot showing the relationship between gestational hypertension and endometriosis between the two case and control group

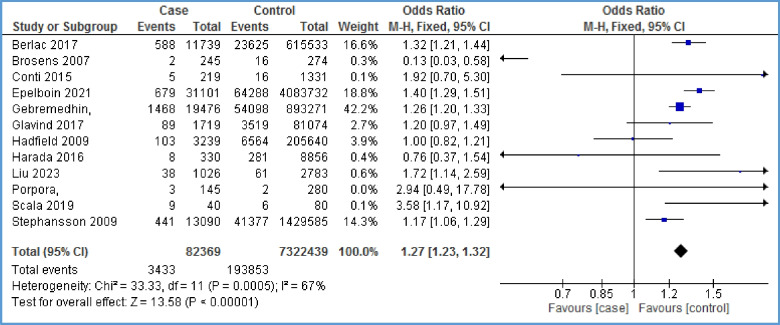

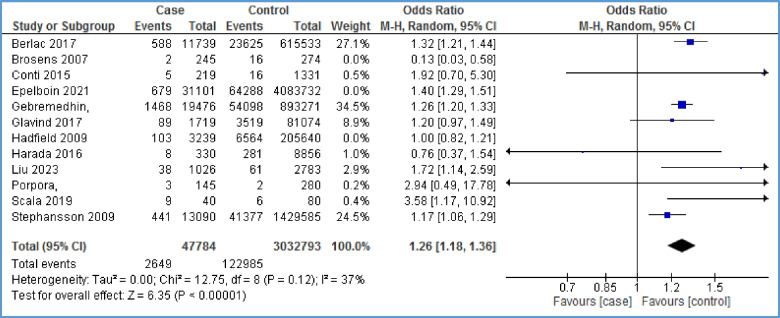

Pre-eclampsia

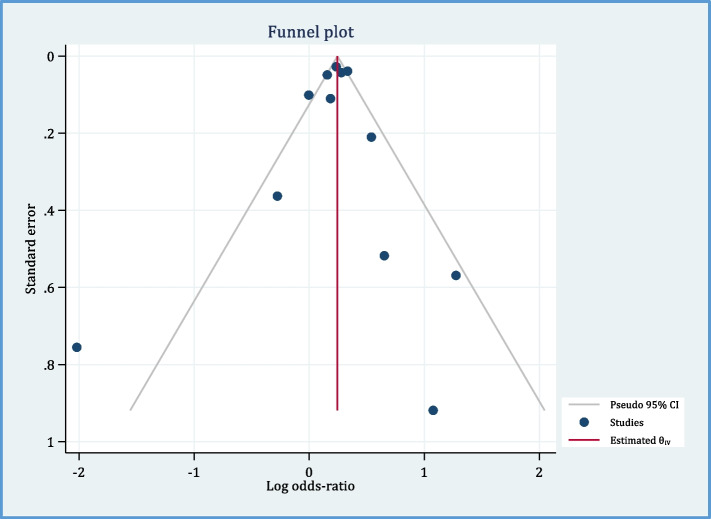

Twelve papers reported the relationship between pre-eclampsia and endometriosis [6, 16–18, 26–28, 30, 35, 38, 39, 42]. As Fig. 3 shows, there is a positive relationship between pre-eclampsia and endometriosis (OR = 1.27, 95% CI: 1.23, 1.32; I2 = 67%, P < 0.00001; N = 12). Because of high heterogeneity, we performed sensitivity analysis. By removing the effect of three studies [17, 18, 42] on the overall results, heterogeneity reached 44%, and still, the evidence indicated a statistically significant positive relationship between endometriosis and preeclampsia (OR = 1.26, 95% CI: 1.18, 1.36; I2 = 37%, P < 0.00001) (Fig. 4). Based on this, the chance of developing pre-eclampsia in the case group is 1.26 times that of the control group. In other words, the chance of developing pre-eclampsia in the case group is 26% higher than that in the control group. The distribution of points in the funnel plot (Fig. 5) as well as the Egger test results in Table 3 show that there is no publication bias (P-value = 0.808).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot showing the relationship between pre-eclampsia and endometriosis between the two case and control group

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of sensitivity analysis showing the relationship between pre-eclampsia and endometriosis between the two case and control group

Fig. 5.

Funnell plot of included studies to assess the potential publication bias

Table 3.

Egger test results for publication bias

| Beta (SE) | Z | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Egger test for pre-eclampsia | -0.11 (0.47) | -0.24 | 0.808 |

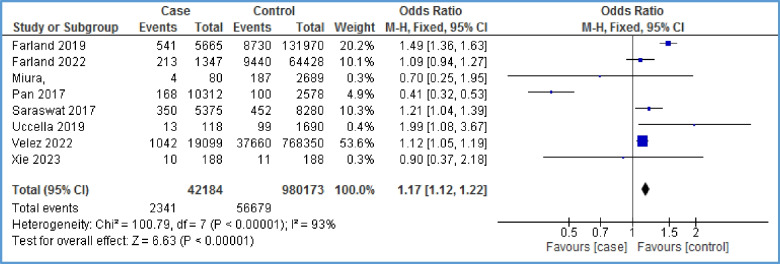

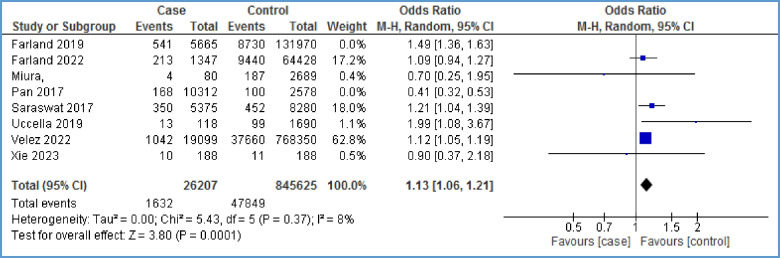

Hypertensive disorders

Eight papers [10, 29, 32, 34, 37, 40, 41, 43] assessed the overall occurrence of hypertensive disorders (combined gestational hypertension-preeclampsia) in women affected with endometriosis. The meta-analysis showed a statistically significant relationship between hypertensive disorders and endometriosis with high heterogeneity (OR = 1.17, 95% CI: 1.12, 1.22; I2 = 93%, P < 0.00001; N = 8) (Fig. 6). To reduce heterogeneity, we omitted the effect of two papers [10, 40] on the overall results. Heterogeneity reached eight percent, and a statistically significant relationship between the two variables was identified (OR = 1.13, 95% CI: 1.06, 1.21; I2 = 8%, P = 0.0001) (Fig. 7). In other words, the chance of developing hypertensive disorder in the case group is 13% higher than that in the control group. A funnel plot could not be generated due to the limited number of papers on the relationship between hypertensive disorders and endometriosis.

Fig. 6.

Forest plot showing the relationship between hypertensive disorders and endometriosis between the two case and control group

Fig. 7.

Forest plot of sensitivity analysis showing the relationship between hypertensive disorders and endometriosis between the two case and control group

Assessment of the risk of bias within studies

The quality assessment of the included studies is shown in Table 4. The median total quality score was 16 which represented moderate quality.

Table 4.

Quality assessment of the articles reviewed

| Study ID (Author, Year) | Clarity | External validity | Internal validity | Power | Total score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bias | Confounding | |||||

| Brosens et al. 2007 [17] | 9 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 17 |

| Berlac et al. 2017 [38] | 7 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 16 |

| Conti et al. 2015 [26] | 7 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 14 |

| Epelboin et al. 2021 [42] | 9 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 18 |

| Farland et al. 2019 [40] | 9 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 19 |

| Farland et al. 2022 [41] | 9 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 19 |

| Gebremedhin et al. 2023 [35] | 8 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 17 |

| Glavind et al. 2017 [39] | 8 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 18 |

| Hadfield et al. 2009 [18] | 7 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 16 |

| Harada et al. 2016 [30] | 8 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 17 |

| Ibiebele et al. 2022 [36] | 9 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 19 |

| Lin et al. 2015 [33] | 9 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 15 |

| Liu et al. 2023 [6] | 7 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 16 |

| Mekaru et al. 2013 [31] | 7 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 15 |

| Miura et al. 2019 [32] | 9 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 19 |

| Pan et al. 2017 [10] | 9 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 21 |

| Saraswat et al. 2016 [37] | 9 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 21 |

| Stephansson et al. 2009 [16] | 9 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 20 |

| Porpora et al. 2020 [27] | 7 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 14 |

| Scala et al. 2019 [28] | 9 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 15 |

| Uccella et al. 2019 [29] | 5 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 9 |

| Velez et al. 2022 [43] | 9 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 19 |

| Xie et al. 2023 [34] | 8 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 18 |

| Mean range | 16 | |||||

Discussion

This systematic review aimed to evaluate the correlation between hypertensive disorders in pregnancy and endometriosis. We included 23 observational studies which had a moderate quality score on average. The pooled evidence in this meta-analysis showed that the odds of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia were higher in women with endometriosis when compared to those without endometriosis. Endometriosis is an important cause of infertility. Pathophysiological speaking, it is expected to affect pregnancy outcomes [14]. Hormonal and inflammatory changes that occur in pregnancy are essential to ensure proper decidualization and placentation. In addition, these changes are also necessary to maintain pregnancy and active labor at term. Similarly, in endometriosis, there are hormonal changes and inflammatory factors that can overlap with pregnancy changes, ultimately causing disruption in pregnancy processes [44]. Cytokines, proteases, and matrix metalloproteinases play a major role in proper decidualization, which is necessary for successful blastocyst implantation. In endometriosis, inflammatory pathways that are regulated by decidua cells may be changed, which could lead to impaired proper trophoblast invasion and implantation [44]. Studies conducted on the relationship between endometriosis and hypertension disorders have yielded conflicting results. Similar to our findings, a systematic review by Breintoft et al. (2021) showed that endometriosis due to placental dysfunction is associated with an increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes including gestational hypertension and preeclampsia [45]. Although our study focused on women who conceived spontaneously, the population in Breintoft et al. consisted of all women who conceived with ART or spontaneously. Also, the number of included studies was small in the mentioned study.

A large population-based cohort study confirmed that there is a higher risk of preeclampsia in women with endometriosis compared to those without endometriosis [35]. It included a very large sample size, and its results support a significant association of endometriosis with an increased risk of preeclampsia and other outcomes including placenta previa and preterm birth. However, the results of a systematic review including more than one million women showed that endometriosis had no relationship with gestational hypertension or preeclampsia [46]. This is probably due to the limitations noted in that study, namely a) inconsistently adjusted confounding factors that applied among the multiple sets of data and b) diagnosis and management of pregnancy complications that could differ across the studies. In addition, in the mentioned review, the participants were women who had become pregnant after in vitro fertilization (IVF), but our study included women who had become pregnant spontaneously. Conversely, a cohort study involving 787,449 women with singleton pregnancies showed that endometriosis was associated with an increased risk of hypertensive disorders during pregnancy [43]. This finding may be explained by the fact that in women with endometriosis, changes in cytokines and thicker junctional zones of the myometrium cause inappropriate trophoblast invasion [44, 47]. Since the conversion of spiral arteries in the myometrial junctional zone is a necessary process for the formation of normal placenta, various characteristics of the junctional zone of endometriosis patients can cause abnormal placental function and thus increase the risk of pregnancy-induced hypertension disorders [47, 48].

This study has a significant strength because of the large number of studies reviewed and the large number of participants recruited, which increases the reliability of the conclusions. The accuracy of data was improved due to the absence of publication bias. Also, the diagnosis of endometriosis was confirmed in most cases using surgery and laparoscopy. To maintain consistency in the study results, we only included women who conceived naturally and excluded those who conceived through IVF.

Despite these strengths, this study had a number of limitations. Unfortunately, there was insufficient data in most studies to perform subgroup analysis based on endometriosis extension, clinical severity, duration of the illness, staging, and women’s age and parity, which could be considered as confounding factors. Additionally, about 50% of pregnant women with ovarian or deep endometriosis may be unaware of their condition [49]. As a result, there could be a significant number of women with endometriosis who are misdiagnosed due to lack of awareness about their condition, potentially impacting research results. It is important to note that adenomyosis, a condition related to endometriosis where the endometrium invades the myometrium, was not taken into account in this review. In addition, the study with the greatest significance in this meta-analysis was the one conducted by Ibiebele et al. (2022) [36], which established a strong and positive relationship between gestational hypertension and endometriosis. Other studies included in the analysis did not demonstrate a significant relationship between the two conditions. Therefore, more high-quality studies are needed to prove the relationship between these two medical conditions.

Conclusion and recommendations

Our results showed that the odds of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia were higher in women with endometriosis compared to those without endometriosis. This finding help physicians to apply effective strategies for the screening and early diagnosis of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy, which could reduce the risk of maternal and fetal morbidity during pregnancy. However, we recommend that more high-quality studies be conducted to prove the relationship between gestational hypertension and endometriosis. Also, there is a need to conduct longitudinal observational studies to investigate the effect of endometriosis on hypertensive disorders based on the severity, staging, and location of endometriosis. The effect of endometriosis on spontaneous versus induced pregnancies with assisted reproductive methods should also be compared and examined.

Acknowledgements

This study was extracted from a research project (No. 50004150) approved by the Student Research Committee, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran. We express our gratitude to the officials of the Clinical Research Development Center, Motazedi Hospital, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran.

Abbreviations

- PCOs

Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome

- CKD

Chronic Kidney Disease

- IUGR

Intrauterine Growth Restriction

- LBW

Low Birth Weight

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis

- ICD

International Classification of Disease

- MD

Mean differences

- CI

Confidence intervals

- IVF

In vitro Fertilization

- NK cells

Natural Killer cells

Authors’ contributions

SHF and FSH equally contributed to the conception and design of the research. ZM did the search. SHF and FSH contributed to the acquisition and analysis of the data. ZJ and FA interpreted the data. SHF and FSH drafted the first version of the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript, agree to be fully accountable for ensuring the integrity and accuracy of the work, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was not funded by any funding resource.

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethics Committee of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences approved the present study (Ref. No IR.KUMS.REC.1403.037).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lee HJ, et al. Various anatomic locations of surgically proven endometriosis: a single-center experience. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2015;58(1):53–58. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2015.58.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang YX, et al. Miscarriage on endometriosis and adenomyosis in women by assisted reproductive technology or with spontaneous conception: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:4381346. doi: 10.1155/2020/4381346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becker CM, et al. ESHRE guideline: endometriosis. Hum Reprod Open. 2022;2022(2):hoac009. doi: 10.1093/hropen/hoac009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allaire C, Bedaiwy MA, Yong PJ. Diagnosis and management of endometriosis. CMAJ. 2023;195(10):E363–e371. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.220637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delanerolle G, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the Endometriosis and Mental-Health Sequelae The ELEMI Project. Womens Health (Lond) 2021;17:17455065211019717. doi: 10.1177/17455065211019717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu ZZ, et al. Effects of endometriosis on pregnancy outcomes in Fujian province. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2023;27(22):10968–10978. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202311_34465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yela DA, et al. Risk factors for recurrence of deep infiltrating endometriosis after surgical treatment. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2021;47(8):2713–2719. doi: 10.1111/jog.14837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu P, Green M, Myers JE. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. BMJ. 2023;381:e071653. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-071653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang L, et al. A global view of hypertensive disorders and diabetes mellitus during pregnancy. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2022;18(12):760–775. doi: 10.1038/s41574-022-00734-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pan ML, et al. Risk of gestational hypertension-preeclampsia in women with preceding endometriosis: a nationwide population-based study. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0181261. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mardanian F, Kianpour M, Sharifian E. Association between endometriosis and pregnancy hypertension disorders in nulliparous women. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertility. 2016;19(7):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang H, et al. Immune and endocrine regulation in endometriosis: what we know. J Endometriosis Uterine Disord. 2023;4:100049. doi: 10.1016/j.jeud.2023.100049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deer E, et al. The role of immune cells and mediators in preeclampsia. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2023;19(4):257–270. doi: 10.1038/s41581-022-00670-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lim HJ, et al. Endometriosis and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a nationwide population-based study. J Clin Med. 2023;12(16):5392. doi: 10.3390/jcm12165392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brosens I, Pijnenborg R, Benagiano G. Defective myometrial spiral artery remodelling as a cause of major obstetrical syndromes in endometriosis and adenomyosis. Placenta. 2013;34(2):100–105. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2012.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stephansson O, et al. Endometriosis, assisted reproduction technology, and risk of adverse pregnancy outcome. Hum Reprod. 2009;24(9):2341–2347. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brosens IA, et al. Endometriosis is associated with a decreased risk of pre-eclampsia. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(6):1725–1729. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hadfield RM, et al. Is there an association between endometriosis and the risk of pre-eclampsia? A population based study. Hum Reprod. 2009;24(9):2348–2352. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moher D, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Banica AM, Popescu SD, Vladareanu S. Obstetric and perinatal complications associated with assisted reproductive techniques - review. Maedica (Bucur) 2021;16(3):493–498. doi: 10.26574/maedica.2020.16.3.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(6):377–384. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.6.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Handler A, Kennelly J, Peacock N. Reducing racial/ethnic disparities in reproductive and perinatal outcomes: the evidence from population-based interventions. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kontopantelis E, Springate DA, Reeves D. A re-analysis of the Cochrane Library data: the dangers of unobserved heterogeneity in meta-analyses. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e69930. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Egger M, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.4 (updated August 2023). Cochrane, 2023. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

- 26.Conti N, et al. Women with endometriosis at first pregnancy have an increased risk of adverse obstetric outcome. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28(15):1795–1798. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2014.968843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Porpora MG, et al. Endometriosis and pregnancy: a single institution experience. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:401. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17020401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scala C, et al. Impact of endometriomas and deep infiltrating endometriosis on pregnancy outcomes and on first and second trimester markers of impaired placentation. Medicina (Kaunas) 2019;55(9):550. doi: 10.3390/medicina55090550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uccella S, et al. Pregnancy after endometriosis: maternal and neonatal outcomes according to the location of the disease. Am J Perinatol. 2019;36(S 02):S91–s98. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1692130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harada T, et al. Obstetrical complications in women with endometriosis: a cohort study in Japan. PLoS One. 2016;11(12):e0168476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mekaru K, et al. Endometriosis and pregnancy outcome: are pregnancies complicated by endometriosis a high-risk group? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;172:36–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miura M, et al. Adverse effects of endometriosis on pregnancy: a case-control study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):373. doi: 10.1186/s12884-019-2514-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin H, et al. Obstetric outcomes in Chinese women with endometriosis: a retrospective cohort study. Chin Med J (Engl) 2015;128(4):455–458. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.151077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xie L, et al. Adverse pregnancy outcomes associated with endometriosis and its influencing factors. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2023;2023:7486220. doi: 10.1155/2023/7486220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 35.Gebremedhin AT, Mitter VR, Duko B, Tessema GA, Pereira GF. Associations between endometriosis and adverse pregnancy and perinatal outcomes: a population-based cohort study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2024;309(4):1323–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Ibiebele I, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in women with endometriosis and/or ART use: a population-based cohort study. Hum Reprod. 2022;37(10):2350–2358. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deac186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saraswat L, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in women with endometriosis: a national record linkage study. BJOG. 2017;124(3):444–452. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berlac JF, et al. Endometriosis increases the risk of obstetrical and neonatal complications. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2017;96(6):751–760. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Glavind MT, et al. Endometriosis and pregnancy complications: a Danish cohort study. Fertil Steril. 2017;107(1):160–166. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Farland LV, et al. Endometriosis and risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134(3):527–536. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Farland LV, et al. Pregnancy outcomes among women with endometriosis and fibroids: registry linkage study in Massachusetts. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;226(6):829.e1–829.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.12.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Epelboin S, et al. Endometriosis and assisted reproductive techniques independently related to mother-child morbidities: a French longitudinal national study. Reprod Biomed Online. 2021;42(3):627–633. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2020.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Velez MP, et al. Mode of conception in patients with endometriosis and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a population-based cohort study. Fertil Steril. 2022;118(6):1090–1099. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2022.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salamonsen LA, et al. Complex regulation of decidualization: a role for cytokines and proteases–a review. Placenta. 2003;24 Suppl A:S76–85. doi: 10.1053/plac.2002.0928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Breintoft K, et al. Endometriosis and risk of adverse pregnancy outcome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2021;10(4):667. doi: 10.3390/jcm10040667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zullo F, et al. Endometriosis and obstetrics complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2017;108(4):667–672.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Exacoustos C, et al. The uterine junctional zone: a 3-dimensional ultrasound study of patients with endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(3):248.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leone Roberti Maggiore U, et al. A systematic review on endometriosis during pregnancy: diagnosis, misdiagnosis, complications and outcomes. Hum Reprod Update. 2016;22(1):70–103. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmv045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Knez J, et al. Natural progression of deep pelvic endometriosis in women who opt for expectant management. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2023;102(10):1298–1305. doi: 10.1111/aogs.14491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.