Abstract

Previous studies provided evidence that nonstructural protein μNS of mammalian reoviruses is present in particle assembly intermediates isolated from infected cells. Morgan and Zweerink (Virology 68:455–466, 1975) showed that a subset of these intermediates, which can synthesize the viral plus strand RNA transcripts in vitro, comprise core-like particles plus large amounts of μNS. Given the possible role of μNS in particle assembly and/or transcription implied by those findings, we tested whether recombinant μNS can bind to cores in vitro. The μNS protein bound to cores, but not to two particle forms, virions and intermediate subvirion particles, that contain additional outer-capsid proteins. Incubating cores with increasing amounts of μNS resulted in particle complexes of progressively decreasing buoyant density, approaching the density of protein alone when very large amounts of μNS were bound. Thus, the μNS-core interaction did not exhibit saturation or a defined stoichiometry. Negative-stain electron microscopy of the μNS-bound cores revealed that the cores were intact and linked together in large complexes by an amorphous density, which we ascribe to μNS. The μNS-core complexes retained the capacity to synthesize the viral plus strand transcripts as well as the capacity to add methylated caps to the 5′ ends of the transcripts. In vitro competition assays showed that mixing μNS with cores greatly reduced the formation of recoated cores by stoichiometric binding of outer-capsid proteins μ1 and ς3. These findings are consistent with the presence of μNS in transcriptase particles as described previously and suggest that, by binding to cores in the infected cell, μNS may block or delay outer-capsid assembly and allow continued transcription by these particles.

The infectious virion of mammalian orthoreoviruses (reoviruses), prototype members of the Reoviridae family, has a genome composed of 10 double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) segments surrounded by two concentric protein capsids. The virion can be proteolytically cleaved in vitro to generate the intermediate subvirion particle (ISVP), which lacks outer-capsid protein ς3 and contains fragments of outer-capsid protein μ1. Further proteolysis removes the μ1 fragments and releases outer-capsid protein ς1, yielding the core particle (reviewed in reference 34). When provided with substrates, the core is transcriptionally active in vitro, using the dsRNA genome segments as templates for synthesis of the 10 full-length plus strand transcripts (3, 24, 39). In addition, these transcripts are modified to have a cap 1 structure (m7NGpppGm2′O) at their 5′ ends by viral enzymes within the core (15, 37). The resulting capped transcripts, which are released from the core as they are synthesized (4), are competent for translation into the reovirus proteins (38). Three of these proteins, μNS, ςNS, and ς1s, are synthesized in infected cells but are not found in purified virions (36, 49). The functions of these “nonstructural” proteins are not well understood, but all members of the Reoviridae family encode such proteins suggesting that they play important roles during infections by these viruses (13).

μNS (called μ0 in older papers), an 80,000-Mr (80K) nonstructural protein, is encoded by the reovirus M3 genome segment (27, 32). M3 encodes another protein, μNSC, whose Mr is approximately 5,000 smaller than that of μNS and that is recognized by μNS-specific monoclonal antibodies (23). μNSC is thought to be generated by translation initiation at a downstream start codon in the open reading frame that encodes μNS, such that μNSC lacks approximately 5,000 Da of sequences that are present at the amino (N) terminus of μNS (28, 44). Both μNS and μNSC are present in cells infected with the prototype isolates of all three reovirus serotypes (23), are expressed to moderate levels throughout infection (17), and are present in the infected cell at a μNS:μNSC ratio of 1:1 to 4:1 (44). Whether the two proteins have functional differences has not yet been addressed. Because the activities of μNSC have not been differentiated from those of μNS, the two proteins are generally referred to as μNS in this report.

Although the roles of μNS in the reovirus life cycle remain poorly understood, previous observations suggest several possibilities. In one study, antibodies to μNS coimmunoprecipitated the viral plus strand RNA transcripts soon after the transcripts were synthesized in infected cells (1). Through this RNA-protein interaction, μNS may be involved in translation of the viral transcripts, packaging of the RNA segments into new reovirus particles, synthesis of the minus strand RNA, or recognition and sorting of the 10 distinct RNA segments prior to packaging (1). In other studies, μNS was isolated from infected cells in association with different types of viral particles (30, 31, 50). These particles were believed to be assembly intermediates because they chased into virions later in infection (50). In one of these studies, newly assembled “transcriptase particles,” capable of synthesizing the viral plus strand transcripts in vitro, were isolated from cells and shown to comprise core-like particles plus large amounts of μNS (30). The precise function of μNS in these particles was unclear because cores are transcriptionally active in vitro in the absence of μNS (3, 24, 39) and because transcriptionally active particles isolated from cells in other studies contained less or no μNS (31, 40). Nevertheless, the findings of Morgan and Zweerink (30) suggest that μNS may play a role in the regulation of reovirus transcription or particle assembly. Other observations concerning μNS include its association with the cytoskeletal fraction from infected cells (29), possession of predicted α-helical coiled-coil motifs in the carboxyl (C)-terminal third of the μNS sequence (28), and coimmunoprecipitation with ςNS using ςNS-specific antibodies (23). M3 was additionally identified as a genetic determinant of genome segment deletion during passage of reovirus at high multiplicity in culture (6). These results suggest that μNS may be involved at several steps in the viral life cycle, but additional experiments should provide a better description of its roles.

To investigate the association of μNS with viral particles and its possible involvement in transcription or assembly, we obtained μNS protein from expression in insect cells using a recombinant baculovirus and studied its interactions with different types of reovirus particles. After demonstrating μNS binding to cores, but not to virions or ISVPs, we determined various characteristics of the μNS-bound cores (μNS cores), including their continued transcription and capping activities. We also showed that μNS can compete with outer-capsid proteins μ1 and ς3 for binding to cores. The results of these studies suggest several possible roles for μNS cores in the reovirus life cycle, including a role in enhancing production of the viral plus strand transcripts by blocking or delaying outer-capsid assembly on these particles.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

All enzymes were from New England Biolabs, Inc. (Beverly, Mass.), unless otherwise stated. All chemicals were from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.) unless otherwise stated.

Construction of M3 recombinant baculoviruses.

The type 3 Dearing (T3D) reovirus M3 genome segment was cloned by Cashdollar et al. (7) and subcloned into pUC8 by Wiener et al. (44). The clone was a generous gift from M. R. Roner (Florida Atlantic University). For our work, we cut the T3D M3 gene from pUC8 using the PshAI and AflII sites in the terminal nontranslated regions of T3D M3. The 5′ overhang of the AflII site was filled in using the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I (Pharmacia, Piscataway, N.J.). The T3D M3 gene fragment was then blunt end ligated to SmaI-cut pGEM4Z (Promega, Madison, Wis.) to generate pGEM4Z-M3(T3D). The T3D M3 gene was excised from pGEM4Z-M3(T3D) at the BamHI and KpnI sites and ligated to pFastBacI (Gibco-BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.) that had been cut with the same enzymes. The pFastBacI vector containing T3D M3 was transformed into DH10Bac cells (Gibco-BRL) following the manufacturer's instructions to produce a recombinant bacmid. The isolated bacmid was transfected into Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf21) cells (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) to yield a progeny recombinant baculovirus containing the reovirus T3D M3 gene [M3(T3D)-bac]. The stock was then subjected to two serial passages in Sf21 cells to increase viral titer.

The type 1 Lang (T1L) M3 genome segment was reverse transcribed from transcripts and amplified by PCR as described previously (28). For PCR, a primer corresponding to the 29 5′-most nucleotides of the minus strand of the T3D M3 sequence (44) with extra sequence at the 5′ end containing a BamHI restriction site (5′-GCAGGGGATCC-3′) and a primer corresponding to the 35 5′-most nucleotides of the plus strand from the T3D M3 sequence (44) with extra sequence at the 5′ end containing a SalI restriction site (5′-GCGGTCGGTCGAC-3′) were used. The PCR-amplified T1L M3 gene was cut with BamHI and SalI and ligated to pGEM4Z that had been cut with the same enzymes, generating pGEM4Z-M3(T1L). The T1L M3 gene was excised from pGEM4Z-M3(T1L) at the KpnI and SphI sites and ligated to pFastBacI that had been cut with the same enzymes to yield pFastBacI-M3(T1L). The cloned T1L M3 gene was then sequenced and found to contain one nucleotide change at position 242 (G to A) that caused an amino acid change in the encoded protein sequence compared to the published sequence (28). To correct the nucleotide change at 242, part of M3 was removed from pFastBacI-M3(T1L)-G242A and swapped with PCR fragments containing an introduced restriction site. pFastBacI-M3(T1L)-G242A was cut in the multiple cloning site of the vector and at nucleotide 660 in the M3 gene with PstI. The fragment consisting of the pFastBacI vector and nucleotides 661 to 2241 of T1L M3 was gel isolated. Reverse transcripts from the T1L M3 genome segment were amplified by PCR with a primer at the 5′ end containing extra sequence with a PstI site (5′-AGGATCCTGCAGCTAGCTAAAGTGACCGTGGTC-3′) and an internal primer (5′-GCACAATATCAACCCTGAC-3′) as described previously (28). The PCR product was cut with PstI and ligated to the gel-isolated pFastBacI and M3 fragment. The resulting pFastBacI-M3(T1L) was sequenced to ensure that the encoded amino acid sequence from the cloned T1L M3 gene matched the published sequence (28). A recombinant baculovirus containing the T1L M3 gene [M3(T1L)-bac] was constructed as described above for the T3D M3 gene.

Expression of recombinant μNS.

To express μNS protein, 7.5 × 106 Trichoplusia ni cells (High Five, Invitrogen) were plated on a 100-mm-diameter dish, infected with M3(T3D)-bac at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1, and incubated at 27°C. The cells were harvested at 52 h postinfection by being pelleted at 500 × g for 10 min at 4°C, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (137 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 8 mM Na2HPO4, 1 mM KH2PO4), and repelleted. The cell pellet was resuspended in 500 μl of lysis buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 2.5 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NaCl2, 0.5% Triton X-100, 5 μg of leupeptin/ml, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM dithiothreitol) and placed on ice for 30 min with mixing every 5 min. The insoluble fraction was removed by spinning the mixture at 500 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The amount of μNS expressed in the lysate varied from 0.3 to 0.8 μg of μNS per μl of lysate as estimated from Coomassie blue-stained gels with bovine serum albumin standards. The μNS protein used in the experiments described in this paper was T3D μNS unless otherwise specified.

Production of μNS polyclonal antibodies.

To direct expression of μNS with an N-terminal histidine tag, the T3D M3 gene was removed from pGEM4Z-M3(T3D) at the BamHI and KpnI sites and ligated to pRSETB (Invitrogen) that had been cut with the same enzymes. The plasmid was transformed into BL21-DE3 cells (Novagen, Madison, Wis.), and the histidine-tagged μNS was expressed and purified following the protocol in the pET system manual (Novagen). In brief, expression was induced with isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (0.19 mg/ml), and the cells were grown at 37°C for 3 h. Intact cells were pelleted, resuspended, and lysed by sonication. The insoluble fraction containing μNS was spun down and solubilized in 8 M urea. The histidine-tagged μNS was purified with His-bind resin (Novagen) in column format. The eluent was dialyzed into phosphate-buffered saline and concentrated with polyethylene glycol. The antiserum was generated in a rabbit by the polyclonal antibody service in the animal care unit of the University of Wisconsin Medical School (Madison, Wis.).

Growth of reovirus and purification.

Infections and purification of reovirus T1L and T3D virions were performed as described previously (14). ISVPs were prepared by digestion of particles with chymotrypsin as described previously (33). Reovirus cores were prepared by digestion as described for reoviruses T3D (25) and T1L (12). Cores were alternatively prepared using an expedited protocol as described previously (9). To obtain particles labeled with [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine, 5 mCi of Easy Tag Express protein labeling mixture (Dupont, Wilmington, Del.) was added per 4 × 108 cells in spinner culture. All particles were purified using equilibrium centrifugation in CsCl density gradients, followed by dialysis into virion buffer (VB) (10 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 10 mM MgCl2, 150 mM NaCl) and storage at 4°C. The concentrations of virions and cores were determined using 1.0 A260 = 2.1 × 1012 virions/ml (42) and 1.0 A260 = 4.2 × 1012 cores/ml (10).

SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis.

Samples were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) in 10% polyacrylamide gels as described previously (18). Proteins were visualized by staining with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 (Coomassie blue). Gels with radiolabeled proteins were dried onto filter paper and visualized by phosphorimaging (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, Calif.). To estimate relative amounts of reovirus proteins from Coomassie blue-stained gels, gels were scanned with a laser densitometer (Molecular Dynamics) and volume-based intensities of the protein bands were determined using the ImageQuant program (Molecular Dynamics). For immunoblots, protein samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) at 4°C for 1 h at 100 V in transfer buffer (25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, pH 8.3). Binding of the primary antibody was detected with alkaline phosphatase-coupled goat anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin (Bio-Rad) and colorimetric reagents p-nitroblue tetrazolium chloride and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate p-toluidine salt (Bio-Rad).

Incubation of μNS lysate with reovirus particles and gradient fractionation.

The buffer conditions for binding were 10 mM Tris, 100 to 120 mM NaCl, 3 to 6 mM MgCl2, and 0.3 to 0.5% Triton X-100. Fifty microliters of insect cell lysate containing μNS was mixed with 2 × 1012 particles (cores, ISVPs, or virions) in VB. For the lysate-alone gradients, 50 μl of insect cell lysate containing μNS was mixed with VB. For the particle-alone gradients, 2 × 1012 particles in VB were mixed with lysis buffer. Samples were incubated for 1 h at 37°C, except for ISVPs, which were incubated at room temperature due to instability at 37°C. The samples were layered onto preformed 3.5-ml CsCl density gradients (1.26 to 1.47 g/cm3 for cores and 1.2 to 1.45 g/cm3 for ISVPs and virions) in an SW60 tube and spun in a Beckman ultracentrifuge for 2 h at 50,000 rpm at 5°C. The gradients were fractionated with a peristaltic pump into 200-μl fractions. The optical density at 280 nm (OD280) and refractive index of each fraction were determined. The density of each fraction was determined based on its refractive index.

Identification of proteins bound to reovirus particles.

Cores, virions, or ISVPs (1012) were mixed with 140 μl of insect cell lysate containing μNS as described above except that all samples were incubated at room temperature. After centrifugation, the particle bands were visualized by light scattering and were harvested by puncturing the bottom of the tube, except for μNS cores, which were harvested with a Pasteur pipette from the top of the gradient. Samples were dialyzed into VB prior to analysis by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

ςNS-expressing recombinant baculovirus and protein expression.

The recombinant baculovirus expressing the T1L ςNS protein was previously described (18). T. ni cells were infected with recombinant baculovirus as described previously (18). Cell lysate was prepared as described above for μNS.

RNase A treatment of μNS cores and μNS lysate.

μNS cores (approximately 2 × 1012) purified on a CsCl gradient and dialyzed into VB were treated with 20 μg of RNase A for 2 h at 37°C and then purified on another CsCl gradient. Untreated μNS cores were analyzed in parallel as a control. μNS lysate (50 μl) was treated with 4 μg of RNase A for 30 min at 25°C and then incubated with 2 × 1012 cores for 1 h at 25°C. Untreated μNS lysate was also analyzed in parallel as a control. The samples were layered on CsCl gradients and spun to equilibrium. Particles were removed from the gradients with a Pasteur pipette and analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

Gradients with different amounts of μNS.

Cores (1012) in 20 μl of VB were mixed with twofold-increasing amounts of insect cell lysate containing μNS (4.3, 8.5, 17, 34, 68, and 140 μl) and brought to a final volume of 170 μl with lysis buffer. Cores (1012) in 20 μl of VB were mixed with 150 μl of lysis buffer or 140 μl of lysate from insect cells infected with wild-type baculovirus and 10 μl of lysis buffer. For the lysate-alone sample, 140 μl of insect cell lysate containing μNS was mixed with 30 μl of lysis buffer. The samples were incubated at room temperature for 1 h and then layered onto preformed 3.5-ml CsCl gradients (1.31 to 1.50 g/cm3) in an SW60 tube. The samples were spun at 50,000 rpm for 2 h at 5°C and visualized with a high-intensity lamp.

Negative-stain electron microscopy (EM).

Samples were negatively stained with 1% uranyl acetate and viewed with a Philips 120 transmission electron microscope at 100 kV as described previously (8).

Sucrose gradient velocity sedimentation of lysate containing μNS.

Insect cell lysate containing μNS (150 μl) was layered on a preformed 11-ml sucrose gradient (5 to 20%) in an SW41 tube and spun in a Beckman ultracentrifuge at 40,000 rpm for 15 h at 5°C. An additional gradient contained 2 mg of each marker, gamma globulin (7S) and thyroglobulin (19S). The gradients were fractionated with a piston gradient fractionator (BioComp Instruments, Inc., New Brunswick, Canada) into 26 equal fractions. The positions of the markers were determined by OD260. Samples from the gradient of μNS lysate were analyzed by immunoblotting.

Transcription and methylation assay.

T3D cores were mixed with various amounts of μNS lysate, incubated for 1 h at room temperature, purified on CsCl gradients, and dialyzed into VB. Cores were also incubated with lysate from wild-type baculovirus-infected cells (the same amount of lysate used to make μNS cores with 980 molecules of μNS per core) and purified on CsCl gradients. μNS cores for transcription reactions were made with [35S]methionine- and [35S]cysteine-labeled T3D cores. The amount of μNS per core was determined from densitometry of Coomassie blue-stained gels. Transcription reactions and transcription/methylation reactions were performed as described previously (26). The aggregated nature of μNS cores led to variability of particle input, so transcription activity was expressed as a ratio of the 32P incorporated into trichloroacetic acid (TCA)-precipitable counts to 35S in the TCA-precipitable counts to standardize the amount of RNA synthesized to the number of 35S-labeled cores in each reaction mixture. Methylation activity was expressed as a ratio of 3H incorporated into TCA-precipitable counts to 32P incorporated into TCA-precipitable counts to standardize for differences in transcription activity.

μNS and μ1-ς3 competition for core binding.

The baculovirus to express T1L μ1 and ς3 proteins was previously described (9). μ1- and ς3-containing lysate (μ1-ς3 lysate) was prepared as described for μNS. T3D cores (5 × 1010) were mixed with 25 μl of lysis buffer, with 20 μl of μ1-ς3 lysate and 5 μl of lysis buffer, or with 5 μl of μNS lysate and 20 μl of lysis buffer as controls for the positions of the resulting particles, cores, recoated cores and μNS cores, respectively. T3D cores (5 × 1010) were mixed with 5 μl of μNS lysate and incubated for 1 h at 37°C, and then 20 μl of μ1-ς3 lysate was added, followed by incubation for 2 h at 37°C. T3D cores (5 × 1010) were mixed with 20 μl of μ1-ς3 lysate and incubated at 37°C for 2 h, and then 5 μl of μNS lysate was added, followed by incubation for 1 h at 37°C. The amount of μ1-ς3 lysate added was sufficient to recoat cores completely as demonstrated previously (9). The amount of μNS lysate was chosen to add approximately the same amount of μ1 and μNS to each sample as estimated from Coomassie blue-stained gels of lysate. After incubation at 37°C, the samples were layered on performed 5.4-ml CsCl density gradients (1.30 to 1.40 g/cm3) in an SW50 tube and spun in a Beckman ultracentrifuge at 40,000 rpm for 2 h 45 min at 5°C. Fractions were TCA precipitated by adding 30 μg of bovine serum albumin as a carrier and 900 μl of cold TCA. Samples were incubated on ice for 20 min and spun for 15 min at 16,000 × g in a microcentrifuge. The supernatant was removed, and the pellet was washed with 500 μl of 70% ethanol, allowed to air dry, resuspended in 20 μl of 1× Laemmli sample buffer (125 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 2% β-mercaptoethanol, 1% SDS, 0.1% bromophenol blue), and incubated at 100°C for 5 min. Samples were analyzed by immunoblotting. μNS, μ1, and the core λ proteins were detected using polyclonal antiserum specific to μNS, polyclonal antiserum specific to reovirus core proteins (S. Noble and M. L. Nibert, unpublished data), and a monoclonal antibody specific to μ1, 10H2 (43).

Computer software.

Images for the figures were scaled uniformly and adjusted for optimal brightness and contrast in Photoshop 4.0 (Adobe System, San Jose, Calif.). All figures were produced in Illustrator 7.0 (Adobe).

RESULTS

Reovirus μNS protein is expressed to high levels in insect cells.

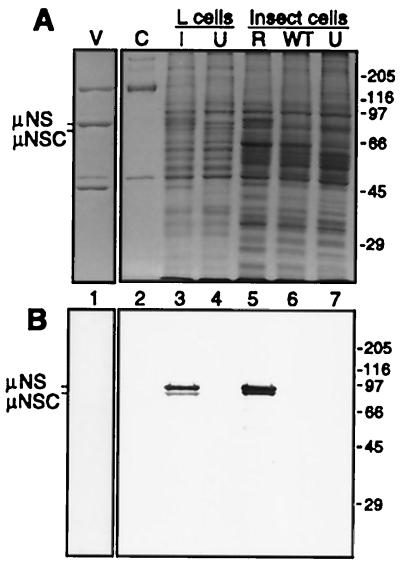

To obtain large amounts of μNS for study, we generated recombinant baculovirus M3(T3D)-bac containing the entire coding region of the T3D reovirus M3 genome segment under transcriptional control of the baculovirus polyhedrin promoter. Insect cells infected with this virus produced a prominent protein doublet with a size of approximately 80K in SDS-polyacrylamide gels, similar to those of the μNS and μNSC proteins from reovirus-infected L cells (Fig. 1A). The doublet is found mostly in the cytoplasmic fraction of lysed insect cells (data not shown). Both the 80K doublet from M3(T3D)-bac-infected cells and μNS and μNSC from reovirus-infected cells were recognized in immunoblots by a polyclonal antiserum that we raised against μNS expressed in Escherichia coli (Fig. 1B). These proteins were also recognized in immunoblots by a monoclonal antibody to μNS (23) (data not shown). The ratio of the two proteins in the doublet varied with each preparation (data not shown). Experiments are in progress to determine whether the lower protein in this doublet has the same origin as μNSC from reovirus-infected cells (44) or may instead represent a breakdown product of μNS. In the subsequent text, we refer to both proteins in the 80K doublet from M3(T3D)-bac-infected cells as μNS. A recombinant baculovirus [M3(T1L)-bac] containing the T1L M3 gene was also constructed and directed expression of an 80K doublet, recognized by the polyclonal μNS antiserum, to levels as high as those for the T3D protein (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis of μNS expression. Murine L cells were infected with T3D reovirus at an MOI of 40 and harvested at 24 h postinfection. Insect cells were infected with M3(T3D)-bac at an MOI of 1 and harvested at 52 h postinfection. (A) An SDS-polyacrylamide gel was loaded with 5 × 1010 reovirus virions (V), 5 × 1010 reovirus cores (C), cytoplasmic lysate of 8.8 × 104 L cells infected with reovirus (I), cytoplasmic lysate of 8.8 × 104 uninfected L cells (U), cytoplasmic lysate of 2.8 × 104 insect cells infected with M3(T3D)-bac (R), cytoplasmic lysate of 3.9 × 104 insect cells infected with wild-type baculovirus (WT), and cytoplasmic lysate of 2.3 × 104 uninfected insect cells (U). (B) An identically loaded gel was analyzed by immunoblotting with a polyclonal antiserum specific to μNS. The positions of μNS and μNSC from infected L cells are indicated to the left, and those of molecular mass markers (kilodaltons) are indicated to the right of each panel.

Density of cores, but not virions and ISVPs, is decreased after incubation with insect cell lysate containing μNS.

Based on the observation from Morgan and Zweerink (30) that transcriptase particles from reovirus-infected cells represent core-like particles plus μNS protein, we tested the capacity of μNS from M3(T3D)-bac-infected insect cells to bind reovirus cores as well as other particle types. In initial experiments, lysate from insect cells expressing μNS (μNS lysate) was mixed with purified T3D cores, T1L ISVPs, or T3D virions. T3D ISVPs were not tested because of their instability at high concentrations. As controls, cores, ISVPs, and virions without insect cell lysate and μNS lysate without cores were analyzed separately. After a period of incubation, a floccular precipitate became visible in the cores-plus-μNS sample, but not in the other samples (data not shown). To separate the reovirus particles and particle-bound proteins from nonbound proteins, the samples were subjected to equilibrium centrifugation in CsCl density gradients. Following centrifugation, virus particles and/or other abundant proteins formed visible bands in the gradients (data not shown). The virions-plus-μNS and ISVPs-plus-μNS gradients contained well-defined bands near the positions of virions and ISVPs observed in the gradients with each of those particles alone (ρ ≈ 1.36 and 1.38 g/cm3, respectively). In the cores-plus-μNS gradient, however, the core band was absent from its expected position, and instead a flocculent white band was seen at a higher position (lower density) than that of cores in the gradient with cores alone (ρ ≈ 1.43 g/cm3). A second prominent band was observed at the top of the cores-plus-μNS, ISVPs-plus-μNS, and virions-plus-μNS gradients, at the same position as the band in the gradient with μNS lysate alone (ρ ≈ 1.30 g/cm3). The loss of the core band and the appearance of a new band at lower density suggested that the RNA-to-protein ratio of the particles had been lowered by the binding of a lysate protein(s) to the cores.

To provide better documentation of the preceding results, the gradients were fractionated and the fractions were analyzed for absorbance at 280 nm and buoyant density. The strong absorbance seen at the top of all gradients was attributable to Triton X-100 in the lysis buffer (data not shown). The gradient profile of μNS lysate alone showed a peak of absorbance near the expected density of protein alone, 1.30 g/cm3, and that of cores alone showed a peak of strong absorbance near the expected density of cores, 1.43 g/cm3 (Fig. 2A). In contrast, the gradient profile of cores plus μNS lacked an absorbance peak at the expected density for cores but exhibited a strong absorbance peak at a lower density, near 1.39 g/cm3 (Fig. 2A), in agreement with the qualitative results described above. Cores were found to migrate near the expected density of 1.43 g/cm3 after incubation with insect cell lysate that lacked μNS, either from uninfected cells or from wild-type baculovirus-infected cells (data not shown). In contrast to what was found for cores, strong absorbance peaks near the densities expected for virions and ISVPs, 1.36 and 1.38 g/cm3, respectively, were noted for these particles in either the presence or absence of μNS lysate (Fig. 2B and C). Taken together, these data indicate that μNS-containing lysate altered the density of reovirus cores, but not those of virions and ISVPs, and that lysate which lacked μNS did not alter the density of cores.

FIG. 2.

Analysis of reovirus particle density shifts in the presence of lysate containing μNS. Reovirus cores (A), virions (B), and ISVPs (C) (2 × 1012) were incubated with 50 μl of buffer or insect cell lysate containing μNS. Lysate was also incubated alone. Samples were subjected to equilibrium centrifugation in CsCl density gradients and fractionated. The buoyant density and OD280 were determined for each fraction. The strong absorbance seen at the top of the gradient (lowest density) is due to detergent in the lysis buffer.

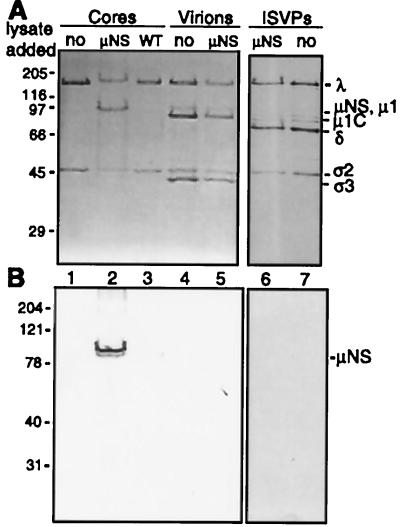

μNS binds cores but not virions or ISVPs.

To determine if a specific lysate protein was interacting with cores, experiments similar to those described above were performed with an increased amount of μNS lysate to allow for detection of particle-bound protein by Coomassie blue staining. The prominent bands in the CsCl gradients were collected and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The sample collected from the gradient of cores plus μNS contained both core proteins and an additional protein of approximately 80K (Fig. 3A, lane 2). This protein was not present in the samples collected from gradients of cores alone or of cores plus wild-type baculovirus lysate (Fig. 3A, lanes 1 and 3). Samples isolated from gradients containing virions and ISVPs, whether previously incubated with μNS lysate or not, contained only proteins present in the respective virus particles (Fig. 3A, lanes 4 through 7). Immunoblot analysis of the gradient-isolated material confirmed that μNS was present as an 80K protein doublet comigrating with cores (Fig. 3B, lane 2). μNS and cores comigrated in gradients after incubation at temperatures from 4 to 37°C and with core concentrations between 1.8 × 1012 and 2.4 × 1013 cores/ml (data not shown). At all ratios of cores to μNS lysate tested to date, both proteins in the μNS doublet bound to cores (data not shown). No detectable μNS comigrated with virions or ISVPs (Fig. 3B, lanes 5 and 6). Similar results were obtained for T3D μNS binding to reovirus T1L particles: the μNS doublet bound to cores but not to virions (data not shown). Thus, the capacity to interact with cores was not specific to the strain or serotype of the virus particles. Moreover, the T1L μNS protein doublet was shown to bind to T1L and T3D cores but not to T1L and T3D virions or T1L ISVPs (data not shown), demonstrating that the selectivity of μNS binding to cores was not specific to the strain or serotype of the virus from which μNS was derived.

FIG. 3.

SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis of μNS binding to reovirus particles. Reovirus cores, virions, or ISVPs (2 × 1012) were incubated in the presence and absence of μNS lysate. Cores were also incubated with wild-type baculovirus lysate. Samples were subjected to equilibrium centrifugation in CsCl density gradients. (A) Particle bands isolated from CsCl density gradients were analyzed by SDS-PAGE with 5 × 1010 particles loaded per lane. Samples (lanes): no, no lysate added; μNS, μNS lysate added; WT, wild-type baculovirus lysate added. (B) An identically loaded gel was subjected to immunoblot analysis with a polyclonal antiserum generated against μNS. For both panels, molecular mass markers (kilodaltons) are on the left and protein mobilities are on the right.

To determine whether similar results might be obtained with ςNS, the other major nonstructural protein of reovirus, cores and insect cell lysate containing ςNS were mixed and then subjected to equilibrium centrifugation in a CsCl density gradient. The appearance and migration of the core band were unchanged in the presence of ςNS. In addition, no ςNS was detected in the harvested core band by immunoblot analysis with polyclonal antiserum to ςNS (18) (data not shown). Thus, ςNS and μNS have different capacities to bind to cores.

Because μNS may bind RNA (1) and because cores produce RNA transcripts, we performed additional experiments to address the possibility that RNA may serve as a required intermediate for μNS binding to cores. Gradient-purified μNS cores were treated with RNase A and then purified in another CsCl gradient. This treatment was not sufficient to disrupt the μNS-core interaction (data not shown). μNS lysate was also treated with RNase A prior to incubation with cores, and this treatment did not prevent μNS cores from forming (data not shown). These findings suggest that μNS associates with cores via protein-protein interactions and not through a single-stranded RNA intermediate.

Density of μNS-core complexes changes with the amount of μNS.

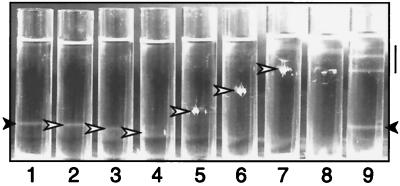

To determine if μNS forms a defined layer on the outside of the core similar to the outer-capsid proteins μ1 and ς3 in virions (9), we investigated whether μNS binding to cores is saturable. Equal numbers of cores were incubated with increasing volumes of μNS lysate. The mixtures were then analyzed in CsCl density gradients to determine their buoyant densities. As controls, cores alone, μNS lysate alone, and cores mixed with wild-type baculovirus lysate were also analyzed. Following centrifugation to equilibrium, the abundant proteins were visualized by direct observation. μNS cores generated with different volumes of μNS lysate were found at different positions in the separate gradients and, therefore, exhibited different buoyant densities. As the volume of added μNS lysate was increased in gradients 5 through 7 (Fig. 4), the buoyant densities of μNS cores continuously decreased. The complexes formed with smaller amounts of μNS lysate in gradients 3 and 4 (Fig. 4), appeared to migrate at a slightly higher density than cores alone in this experiment. This may have been due either to a small increase in the density of the complexes or to slight inconsistencies in the way the different gradients were formed. The complexes formed using the largest lysate volume (Fig. 4, gradient 7) migrated close to the position of the protein alone in the gradient of μNS lysate alone (Fig. 4, gradient 8). After isolation of the μNS-core complexes from the gradients, SDS-PAGE analysis showed that increasing amounts of μNS were bound to the cores, corresponding to the increase in added lysate (data not shown). As in previous experiments, migration of the core band was unchanged after incubation with wild-type baculovirus lysate (Fig. 4, gradient 9). The overall trend of decreasing buoyant density of complexes with increasing μNS, with the density ultimately approaching that of protein alone, suggested that the binding of μNS to cores is not saturable. The progressively larger amounts of μNS bound to a fixed number of cores may reflect the capacity of μNS molecules to self-associate.

FIG. 4.

CsCl density gradients of cores incubated with increasing amounts of lysate containing μNS. Cores (1012) were incubated alone (gradient 1); with 4.3 (gradient 2), 8.5 (gradient 3), 17 (gradient 4), 34 (gradient 5), 68 (gradient 6), or 140 μl (gradient 7) of μNS lysate; or with 140 μl of wild-type baculovirus lysate (gradient 9). μNS lysate (140 μl) was incubated alone (gradient 8). The samples were subjected to equilibrium centrifugation in CsCl density gradients and visualized with a high-intensity light. Solid arrowheads, bands of cores; open arrowheads, complexes of μNS cores; line, position of bands from the lysate alone.

Negative-stain EM of μNS cores reveals cores linked together in large complexes.

To investigate the morphology of μNS cores, the complexes from the gradients in Fig. 4 were examined by negative-stain EM. Micrographs of μNS cores from gradients 5 and 6 revealed intact cores embedded within large complexes (Fig. 5A and B). Cores, the appearance of which is well defined (8, 42), are shown for comparison (Fig. 5B, inset). The cores in the μNS core samples were linked together by an amorphous density which we attribute to μNS. The large complexes and amorphous density surrounding the cores were not present in samples containing either cores alone or cores that had been mixed with wild-type baculovirus-infected cell lysates before gradient isolation (Fig. 5B, inset, and data not shown). μNS cores from other gradients exhibited similar morphology (data not shown). Notably, the cores in samples with smaller amounts of μNS were also linked together in complexes (data not shown). Since nonphysiological cysteine bond formation between μNS molecules was one possible explanation for the observations, in a subsequent experiment 1 mM dithiothreitol was added to the lysis buffer, the core-binding reaction mixture, and the CsCl gradient; however, the presence of this reducing agent did not affect the aggregated nature of μNS cores (data not shown). In sum, these data provide evidence that (i) μNS bound to cores such that a regularly structured outer capsid of protein was not formed and (ii) the intact particles were linked together.

FIG. 5.

Negative-stain EM of μNS cores and velocity sedimentation analysis of μNS lysate. μNS cores were purified on a CsCl gradient, dialyzed into VB, stained with uranyl acetate, and viewed by EM. (A) μNS cores viewed at low resolution. Bar, 200 nm. (B) μNS cores viewed at higher resolution. The inset provides an image of cores for comparison. Bars, 100 nm. (C) μNS lysate was subjected to velocity sedimentation on a sucrose gradient. The gradient was fractionated and subjected to immunoblot analysis with polyclonal antiserum specific to μNS. Markers (7S and 19S) were analyzed on a parallel gradient, and the positions were determined by OD260. The positions of the 7S and 19S markers and the top and bottom of the gradient are indicated. The 19S marker was pelleted at the bottom of the gradient with the centrifugation conditions used in this experiment. The position of μNS is indicated to the right.

μNS may have been present in the lysate as large complexes before binding to cores. We could not test this by visualization with EM because the lysate contained too many proteins and other contaminants. Instead, we analyzed μNS lysate by velocity sedimentation in sucrose gradients to estimate the size of μNS complexes present in the lysate prior to incubation with cores. μNS sedimented as a single peak near the 7S marker (Fig. 5C). The 19S marker was pelleted under these sedimentation conditions. The predicted S values for a globular 80-kDa protein are 4.7 for a monomer, 7.4 for a dimer, and 9.7 for a trimer (47). Thus, μNS in the lysate appears to be a monomer or small oligomer that forms large complexes only when incubated with cores.

μNS cores retain transcriptional activity.

If the μNS-core complexes formed in vitro are similar to transcriptase particles isolated from reovirus-infected cells (30), the complexes should be transcriptionally active. The transcriptional activities of μNS cores containing different amounts of bound μNS were therefore tested and compared to that of cores. Cores mixed with wild-type baculovirus-infected lysate and then gradient purified were included as a control to address whether cellular factors from the lysate could affect the transcriptional activity of cores. Because the aggregated nature of μNS cores made them difficult to aliquot consistently, the transcriptional activity of each sample was standardized to the number of input particles by use of cores labeled with [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine. Transcriptional activity was expressed as the ratio of 32P incorporated into acid-precipitable counts to the 35S counts in each reaction mixture. Results of a representative experiment are shown in Fig. 6A. μNS cores containing approximately 50 or 1,300 μNS molecules per core were slightly less active at transcription than either the original cores or cores mixed with wild-type baculovirus-infected lysate prior to purification. In four different experiments, the transcriptional activities of μNS cores ranged from 46 to 84% (mean, 66% ± 13%) of that of cores. The transcripts from cores and μNS cores were indistinguishable when separated on denaturing gels (data not shown). To verify that μNS remained bound to cores during transcription, transcription reaction mixtures containing μNS cores were layered on CsCl density gradients, spun to equilibrium, and fractionated. μNS continued to comigrate with cores in this experiment (data not shown), suggesting that it remained bound to cores. In sum, the results indicate that the binding of μNS to cores did not inhibit the core transcriptional activity as assembly of outer-capsid proteins is believed to do (2, 11, 21, 46; D. L. Farsetta, K. Chandran, and M. L. Nibert, unpublished data).

FIG. 6.

Analysis of μNS cores for transcription and methylation activities. (A) Standard transcription reactions were performed in triplicate with purified 35S-labeled cores (core), purified 35S-labeled cores previously mixed with wild-type baculovirus lysate (WT), and purified 35S-labeled cores with two different amounts of μNS bound. The approximate amount of μNS per core was determined by densitometry. The mean transcriptional activity ± standard deviation is reported as TCA-precipitable 32P counts relative to 35S counts to normalize for particle input. (B) Methylation activity was monitored using standard transcription reaction mixtures containing the methyl donor [3H]SAM. Activity is expressed as TCA-precipitable 3H counts normalized to the amount of transcription with TCA-precipitable 32P counts. These results are from four separate experiments with three separately prepared μNS core samples. The average activity of cores in each experiment was normalized to one, and the other samples were scaled appropriately. Cores mixed with wild-type baculovirus lysate and purified (WT), μNS cores with 350 molecules of μNS per core, and μNS cores with 980 molecules of μNS per core were assayed once in triplicate. The other samples of μNS cores were assayed twice in triplicate.

μNS cores may have elevated transcript 5′-end capping activities.

To evaluate the effects of μNS on the capping of the viral transcripts, μNS cores and cores were quantitatively compared for 5′ cap methylation. RNA methylation activity was assayed in a standard transcription assay mixture containing [α-32P]GTP and the methyl donor S-adenosyl-l-[methyl-3H]-methionine ([3H]SAM). In addition to assaying cap methylation, this approach indirectly assesses the RNA triphosphatase and guanylyltransferase capping activities of particles since these reactions must precede methylation (15). Methylation activity was expressed as a ratio of acid-precipitable 3H counts to acid-precipitable 32P counts to adjust for any differences in transcription activity between samples. The activities of μNS cores with approximately 60 or 350 molecules of μNS bound per core and of cores mixed with wild-type baculovirus-infected lysate and then purified were similar to that of cores (Fig. 6B). However, when more μNS molecules were bound per core (530 to 3,800 molecules of μNS), the methylation activity was increased to approximately twofold that of cores (Fig. 6B). To test if the increased methylation activity was due to a contaminating methylase or nonspecific trapping of [3H]SAM when such large amounts of μNS were bound to cores, we repeated the assay using μNS cores containing either 60 or 980 molecules of μNS under conditions that are not permissive for full-length transcript production: in the presence of GTP only at 45°C, ATP only at 45°C, or all four nucleotides at 4°C. None of these conditions supported detectable methylation activity with either preparation of μNS cores or cores alone (data not shown). Thus, we conclude that the methylation increase observed with higher levels of μNS per core was dependent on transcript production, suggesting that it was due to an increase in transcript capping.

μNS incubation with cores greatly decreases the efficiency of recoated core formation.

To test if μNS can inhibit the binding of the outer-capsid proteins to cores, we mixed μNS lysate and lysate containing μ1 and ς3 (μ1-ς3 lysate) with cores in vitro. Relative amounts of the two lysates were chosen to provide approximately the same amount of μNS and μ1 for binding to the core surface. Cores were incubated alone, with μNS lysate, or with μ1-ς3 lysate to provide controls for the positions of the resulting particles, cores, μNS cores, and recoated cores, respectively, in CsCl gradients. Cores were incubated with both μNS lysate and μ1-ς3 lysate together, with μNS lysate first then with μ1-ς3 lysate, or with μ1-ς3 lysate first then with μNS lysate to see if the incubation of μNS with cores during or before the addition of μ1 and ς3 would affect the formation of recoated cores. The samples were layered on CsCl density gradients, spun to equilibrium, fractionated, and subjected to immunoblot analysis. Cores alone migrated to the bottom of the gradient (Fig. 7A), whereas recoated cores migrated into the lower half of the gradient (Fig. 7B). Note that some core proteins and μ1 remained trapped at the top of the gradient, migrating with protein alone (Fig. 7B). μNS cores migrated only into the upper half of the gradient (Fig. 7C), near protein alone at the top of the gradient. When cores were incubated first with μ1-ς3 lysate, allowing the formation of recoated cores before μNS lysate was added, both the core proteins and μ1 were detected in the lower half of the gradient at the position of recoated cores (Fig. 7D). In addition, no μNS was detected in the fractions containing core proteins and μ1 at the position of recoated cores, confirming that recoated cores had been formed. This agrees with the result that μNS does not bind to virions (Fig. 3). When cores were incubated first with μNS lysate, allowing the formation of μNS cores before μ1-ς3 lysate was added, little or no core proteins or μ1 was detected in the lower half of the gradient (Fig. 7E), suggesting that the formation of recoated cores was greatly reduced by prior formation of μNS cores. When μ1-ς3 lysate and μNS lysate were mixed prior to addition of cores, little or no core proteins or μ1 was detected in the lower half of the gradient (Fig. 7F), suggesting that formation of recoated cores was greatly reduced by simultaneous incubation with μNS. From these results, we conclude that the incubation of μNS with cores greatly reduces the capacity of μ1 and ς3 to bind to cores in a manner conducive to recoated core formation.

FIG. 7.

Incubation of cores with μNS lysate and/or μ1 and ς3 lysate. Cores were incubated alone or with combinations of lysate containing μNS or μ1 and ς3. Samples were layered on CsCl density gradients and spun to equilibrium. Gradients were fractionated, and the fractions were subjected to immunoblot analysis. (A) Cores incubated with lysis buffer. (B) Cores incubated with μ1 and ς3 lysate. (C) Cores incubated with μNS lysate. (D) Cores incubated with μ1 and ς3 lysate followed by addition of μNS lysate and further incubation. (E) Cores incubated with μNS lysate followed by addition of μ1 and ς3 lysate and further incubation. (F) μ1 and ς3 lysate and μNS lysate mixed, followed by addition of cores and incubation. Antibodies used in the immunoblots are listed to the left, and proteins are labeled on the right. The top and bottom of the gradients are labeled below. The positions of recoated cores and cores are labeled at the top.

DISCUSSION

μNS cores are similar to transcriptase particles.

The μNS-coated cores that we formed in vitro from purified cores and recombinant μNS protein share a number of characteristics with the transcriptase particles previously isolated from reovirus-infected cells (30). (i) They have similar protein compositions, including μNS in place of outer-capsid proteins. (ii) They have a complete dsRNA genome (30, 31), in contrast to “replicase” particles isolated from infected cells, which contained little or no μNS and were in the process of converting single-stranded RNA to dsRNA (30, 31). (iii) They are capable of synthesizing the viral plus strand transcripts, although the transcription activity of μNS cores was slightly lower than the activity of cores in this study (Fig. 6A). The activity of transcriptase particles was not quantitatively compared to that of cores in the previous study (30). The μNS cores that we generated in vitro also exhibit mRNA capping activities (Fig. 6B), whereas the capping activities of transcriptase particles were not tested in the previous study (30).

Transcriptase particles isolated from infected cells by another group were inactive for capping of transcripts (40). Gel electrophoresis indicated that these particles did not contain μNS, but they were extracted with Freon prior to electrophoresis, which may have removed μNS (40). Additionally, late transcripts isolated from infected cells by these investigators were uncapped (41), leading to a hypothesis that the presence of μNS may inactivate the capping activities of cores (48). We did not find this to be the case with in vitro-assembled μNS cores; instead, cap methylation was enhanced to twofold that of cores when μNS cores had 530 or more molecules of μNS per core (Fig. 6B). While these data do not directly refute the idea that “late” transcripts are uncapped, they suggest that binding of μNS to cores is not sufficient to result in uncapped transcript production.

The addition of cap 1 structures to reovirus transcripts can approach 100% efficiency in vitro under appropriate conditions: high GTP concentration (0.5 mM), addition of SAM, and inclusion of pyrophosphatase (16). Reaction mixtures that lack pyrophosphatase but contain SAM and a high concentration of GTP have been previously reported to allow cap 1 formation on only 50 to 75% of the transcripts while the remaining transcripts contain diphosphorylated uncapped 5′ ends (5, 15). The reaction conditions used in this study (SAM, high GTP concentration, no pyrophosphatase) were thus similar to the latter conditions and allowed us to detect either an increase or decrease in capping activities by μNS cores. Further studies are required to determine which enzymatic activity(ies) in capping is elevated in μNS cores and what is the mechanism of the increased activity.

μNS core large-complex formation.

The interaction of recombinant μNS with cores links them together within large complexes, as viewed by negative-stain EM. μNS binding to cores could produce such aggregates if μNS were present in insect cell lysate as large oligomers formed solely from μNS-μNS interactions; these large oligomers could bind to many cores, yielding large complexes. However, this seems unlikely since μNS sediments as a monomer or small oligomer in velocity gradients (Fig. 5C), suggesting that formation of large complexes is specific to the interaction with cores. If μNS is a monomer or small oligomer, it could link cores together by the binding of one μNS molecule to multiple core particles or by the oligomeric association of μNS molecules bound to different core particles. Once all of the μNS binding sites on the cores are occupied, additional μNS might be added to the complexes by μNS-μNS interactions so that the binding of μNS to cores is not saturable. Further studies on the oligomeric status of μNS and the localization of the μNS binding site(s) for cores may provide insight into the formation of the μNS-core complexes.

Possible role(s) of μNS-core interaction.

In the infected cell, the interaction of the nonstructural protein μNS with the reovirus core may function in steps as diverse as regulation of outer-capsid assembly, virus particle assembly, and RNA translation or sorting. The binding of μNS to newly formed cores within infected cells could prevent the assembly of outer-capsid proteins, as suggested by in vitro findings in this study (Fig. 7), allowing those particles to continue synthesizing viral plus strand transcripts. Prevention of outer-capsid assembly onto certain cores may be required in the cell because assembly of the outer-capsid proteins is believed to shut off transcription by the enclosed core-like particles (2, 11, 21, 46; D. L. Farsetta, K. Chandran, and M. L. Nibert, unpublished data) and because the outer-capsid proteins are present throughout infection in high levels (17). It has been calculated that secondary transcriptase particles (newly formed particles within infected cells) produce 95% of the reovirus mRNA in infected cells (19, 20, 22). μNS could bind a subset of newly assembled cores, sequestering them away from outer-capsid proteins and dedicating them to produce mRNA. Alternatively, μNS cores could be formed only transiently on the assembly pathway from core to virion, but long enough to allow more transcript production than would occur in the absence of μNS.

The μNS-core interaction could be involved in other ways in reovirus particle assembly. It is possible that μNS might be required for directing assembly of the outer-capsid proteins onto the core. However, recent work demonstrated that the reovirus outer-capsid proteins can assemble on cores in vitro in the absence of μNS (9; K. Chandran and M. L. Nibert, unpublished data) (Fig. 7), indicating that μNS is not strictly required for outer-capsid assembly. Furthermore, the results from mixing cores with μNS, μ1, and ς3 in vitro suggest that μNS prevents outer-capsid assembly (Fig. 7). μNS might also function during the assembly of cores. However, assembly of core-like particles containing ς2, λ1, and λ2 has been shown to occur in the absence of μNS (45; J. Kim, S. Noble, and M. L. Nibert, unpublished data), suggesting that μNS is not strictly required for assembling the protein components of cores, although it might be needed to get RNA inside the particle (see next paragraph). Characterization of μNS-bound particles from reovirus-infected cells may provide further evidence for μNS involvement in assembly.

Yet another possibility is that μNS is closely associated with the transcriptase particles in infected cells in order to bind the plus strand RNA transcripts soon after synthesis, as reported previously (1). Through RNA interactions, μNS may assist either in sorting and packaging the 10 different viral transcripts or during minus strand synthesis in the early steps of progeny particle assembly. It may also serve a function in protein translation from these transcripts. For example, μNS may be similar to the rotavirus nonstructural protein NSP3, which interacts with eIF4GI and is believed to enhance translation of the rotavirus transcripts (35). Experiments investigating μNS-RNA interactions should allow these hypotheses to be tested.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to M. R. Roner for supplying the T3D M3 clone and monoclonal antibodies to μNS and to K. L. Tyler and H. W. Virgin IV for supplying the μ1 monoclonal antibody. Special thanks to Wai-Ming Lee for assistance with RNA denaturing gels. We thank A. L. Gillian and K. Chandran for baculovirus stocks for expression of reovirus proteins ςNS, μ1, and ς3; S. J. Harrison for technical assistance; J. Lugus and C. Chapman for laboratory support; the other members of our laboratory for helpful discussions; and D. L. Farsetta, A. L. Gillian, and C. L. Luongo for reviews of a preliminary manuscript. We also thank L. C. Vanderploeg from the Biochemistry Media Lab for photographing gradients and C. Nicolet and colleagues in the DNA sequencing facility at the UW Biotechnology Center for DNA sequencing.

This work was supported by NIH grant R29 AI39533, a USDA Hatch grant awarded through the College of Agricultural and Life Sciences, and a grant to the Institute for Molecular Virology from the Lucille P. Markey Charitable Trust. M.L.N. received additional support as a Shaw Scientist from the Milwaukee Foundation. T.J.B. received additional support from predoctoral fellowships from the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation and NIH grant T32 GM07215 to the Molecular Biosciences Training Grant (University of Wisconsin-Madison).

REFERENCES

- 1.Antczak J B, Joklik W K. Reovirus genome segment assortment into progeny genomes studied by the use of monoclonal antibodies directed against reovirus proteins. Virology. 1992;187:760–776. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90478-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Astell C, Silverstein S C, Levin D H, Acs G. Regulation of the reovirus RNA transcriptase by a viral capsomere protein. Virology. 1972;48:648–654. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(72)90149-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banerjee A K, Shatkin A J. Transcription in vitro by reovirus-associated ribonucleic acid-dependent polymerase. J Virol. 1970;6:1–11. doi: 10.1128/jvi.6.1.1-11.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartlett N M, Gillies S C, Bullivant S, Bellamy A R. Electron microscopy study of reovirus reaction cores. J Virol. 1974;14:315–326. doi: 10.1128/jvi.14.2.315-326.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Both G W, Furuichi Y, Muthukrishnan S, Shatkin A J. Ribosome binding to reovirus mRNA in protein synthesis requires 5′ terminal 7-methylguanosine. Cell. 1975;6:185–195. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(75)90009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown E G, Nibert M L, Fields B N. The L2 gene of reovirus serotype 3 controls the capacity to interfere, accumulate deletions and establish persistent infection. In: Compans R W, Bishop D H L, editors. Double-stranded RNA viruses. New York, N.Y: Elsevier Science Publishing Co., Inc.; 1983. pp. 275–287. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cashdollar L W, Chmelo R, Esparza J, Hudson G R, Joklik W K. Molecular cloning of the complete genome of reovirus serotype 3. Virology. 1984;133:191–196. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(84)90438-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centonze V E, Chen Y, Severson T F, Borisy G G, Nibert M L. Visualization of individual reovirus particles by low-temperature, high-resolution scanning microscopy. J Struct Biol. 1995;115:215–225. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1995.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chandran K, Walker S B, Chen Y, Contreras C M, Schiff L A, Baker T S, Nibert M L. In vitro recoating of reovirus cores with baculovirus-expressed outer-capsid proteins μ1 and ς3. J Virol. 1999;73:3941–3950. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.3941-3950.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coombs K M. Stoichiometry of reovirus structural proteins in virus, ISVP, and core particles. Virology. 1998;243:218–228. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drayna D, Fields B N. Activation and characterization of the reovirus transcriptase: genetic analysis. J Virol. 1982;41:110–118. doi: 10.1128/jvi.41.1.110-118.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dryden K A, Farsetta D L, Wang G-J, Keegan J M, Fields B N, Baker T S, Nibert M L. Internal structures containing transcriptase-related proteins in top component particles of mammalian orthoreovirus. Virology. 1998;225:33–46. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fields B N. Reoviridae. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 1553–1555. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furlong D B, Nibert M L, Fields B N. ς1 protein of mammalian reoviruses extends from the surfaces of viral particles. J Virol. 1988;62:246–256. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.1.246-256.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Furuichi Y, Morgan M, Muthukrishnan S, Shatkin A J. Reovirus messenger RNA contains a methylated, blocked 5′-terminal structure: m-7G(5′)ppp(5′)G-mpCp- Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:362–366. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.1.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Furuichi Y, Shatkin A J. Differential synthesis of blocked and unblocked 5′-termini in reovirus mRNA: effect of pyrophosphate and pyrophosphatase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:3448–3452. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.10.3448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaillard R K, Jr, Joklik W K. The relative translation efficiencies of reovirus messenger RNAs. Virology. 1985;147:336–348. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(85)90136-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gillian A L, Nibert M L. Amino terminus of reovirus nonstructural protein ςNS is important for ssRNA binding and nucleoprotein complex formation. Virology. 1998;240:1–11. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ito Y, Joklik W K. Temperature-sensitive mutants of reovirus. I. Patterns of gene expression by mutants of groups C, D, and E. Virology. 1972;50:189–201. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(72)90359-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joklik W K. The structure and function of the reovirus genome. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1980;80:107–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1980.tb27961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joklik W K. Studies on the effect of chymotrypsin on reovirions. Virology. 1972;49:700–715. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(72)90527-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lai M H, Joklik W K. The induction of interferon by temperature-sensitive mutants of reovirus, UV-irradiated reovirus, and subviral reovirus particles. Virology. 1973;51:191–204. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(73)90379-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee P W K, Hayes E C, Joklik W K. Characterization of anti-reovirus immunoglobulins secreted by cloned hybridoma cell lines. Virology. 1981;108:134–146. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(81)90533-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levin D H, Mendelsohn N, Schonberg M, Klett H, Silverstein S, Kapuler A M, Acs G. Properties of RNA transcriptase in reovirus subviral particles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1970;66:890–897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.66.3.890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luongo C L, Contreras C M, Farsetta D L, Nibert M L. Binding site for S-adenosyl-L-methionine in a central region of mammalian reovirus λ2 protein. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:23773–23780. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.37.23773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luongo C L, Dryden K A, Farsetta D L, Margraf R L, Severson T F, Olson N H, Fields B N, Baker T S, Nibert M L. Localization of a C-terminal region of λ2 protein in reovirus cores. J Virol. 1997;71:8035–8040. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.8035-8040.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCrae M A, Joklik W K. The nature of the polypeptide encoded by each of the 10 double-stranded RNA segments of reovirus type 3. Virology. 1978;89:578–593. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(78)90199-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCutcheon A M, Broering T J, Nibert M L. Mammalian reovirus M3 gene sequences and conservation of coiled-coil motifs near the carboxyl terminus of the μNS protein. Virology. 1999;264:16–24. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mora M, Partin K, Bhatia M, Partin J, Carter C. Association of reovirus proteins with the structural matrix of infected cells. Virology. 1987;159:265–277. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(87)90464-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morgan E M, Zweerink H J. Characterization of transcriptase and replicase particles isolated from reovirus-infected cells. Virology. 1975;68:455–466. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(75)90286-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morgan E M, Zweerink H J. Reovirus morphogenesis. Corelike particles in cells infected at 39° with wild-type reovirus and temperature-sensitive mutants of groups B and G. Virology. 1974;59:556–565. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(74)90465-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mustoe T A, Ramig R F, Sharpe A H, Fields B N. Genetics of reovirus: identification of the ds RNA segments encoding the polypeptides of the μ and ς size classes. Virology. 1978;89:594–604. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(78)90200-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nibert M L, Fields B N. A carboxy-terminal fragment of protein μ1/μ1C is present in infectious subvirion particles of mammalian reoviruses and is proposed to have a role in penetration. J Virol. 1992;66:6408–6418. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.11.6408-6418.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nibert M L, Schiff L A, Fields B N. Reoviruses and their replication. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 1557–1596. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Piron M, Vende P, Cohen J, Poncet D. Rotavirus RNA-binding protein NSP3 interacts with eIF4GI and evicts the poly(A) binding protein from eIF4F. EMBO J. 1998;17:5811–5821. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.19.5811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sarkar G, Pelletier J, Bassel-Duby R, Jayasuriya A, Fields B N, Sonenberg N. Identification of a new polypeptide coded by reovirus gene S1. J Virol. 1985;54:720–725. doi: 10.1128/jvi.54.3.720-725.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shatkin A J. Methylated messenger RNA synthesis in vitro by purified reovirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:3204–3207. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.8.3204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shatkin A J, Kozak M. Biochemical aspects of reovirus transcription and translation. In: Joklik W K, editor. The reoviridae. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1983. pp. 79–106. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Skehel J J, Joklik W K. Studies on the in vitro transcription of reovirus RNA catalyzed by reovirus cores. Virology. 1969;39:822–831. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(69)90019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Skup D, Millward S. mRNA capping enzymes are masked in reovirus progeny subviral particles. J Virol. 1980;34:490–496. doi: 10.1128/jvi.34.2.490-496.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Skup D, Zarbl H, Millward S. Regulation of translation in L-cells infected with reovirus. J Mol Biol. 1981;151:35–55. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90220-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith R E, Zweerink H J, Joklik W K. Polypeptide components of virions, top component and cores of reovirus type 3. Virology. 1969;39:791–810. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(69)90017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Virgin H W, IV, Mann M A, Fields B N, Tyler K L. Monoclonal antibodies to reovirus reveal structure/function relationships between capsid proteins and genetics of susceptibility to antibody action. J Virol. 1991;65:6772–6781. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.12.6772-6781.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wiener J R, Bartlett J A, Joklik W K. The sequences of reovirus serotype 3 genome segments M1 and M3 encoding the minor protein μ2 and the major nonstructural protein μNS, respectively. Virology. 1989;169:293–304. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90154-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu P, Miller S E, Joklik W K. Generation of reovirus core-like particles in cells infected with hybrid vaccinia viruses that express genome segments L1, L2, L3, and S2. Virology. 1993;197:726–731. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yamakawa M, Furuichi Y, Shatkin A J. Reovirus transcriptase and capping enzymes are active in intact virions. Virology. 1982;118:157–168. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(82)90329-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Young B D. Measurement of sedimentation coefficients and computer simulation of rate-zonal separations. In: Rickwood D, editor. Centrifugation: a practical approach. 2nd ed. Oxford, United Kingdom: IRL Press; 1984. pp. 127–159. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zarbl H, Millward S. The reovirus multiplication cycle. In: Joklik W K, editor. The reoviridae. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1983. pp. 107–196. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zweerink H J, McDowell M J, Joklik W K. Essential and nonessential noncapsid reovirus proteins. Virology. 1971;45:716–723. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(71)90185-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zweerink H J, Morgan E M, Skyler J S. Reovirus morphogenesis: characterization of subviral particles in infected cells. Virology. 1976;73:442–453. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(76)90405-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]