Abstract

Hepadnaviruses are known to be sensitive to various extracellular mediators. Therefore, bacterial endotoxin, which induces the secretion of proinflammatory mediators in the liver, was studied for its effect on hepadnavirus infection in vitro using the duck hepatitis B virus (DHBV) model. In initial experiments, endotoxin was shown to inhibit DHBV replication in primary duck hepatocyte cultures prepared by standard collagenase perfusion. As a primary endotoxin target, hepatic nonparenchymal cells (NPC) contaminating primary hepatocyte cultures, and among these probably macrophages (Kupffer cells), were identified to secrete polypeptide mediators into the cell culture medium. When added during DHBV infection, these mediators elicited the principal antiviral effect in a dose-dependent fashion. On the molecular level, they inhibited accumulation of viral proteins as well as amplification of the nuclear extrachromosomal DHBV DNA templates. In hepatocytes with an established DHBV infection, DHBV protein and progeny virus production was inhibited while the levels of established nuclear DHBV DNA templates and viral transcripts remained unaffected. Finally, in hepatocytes infected with a replication-deficient recombinant DHBV-green fluorescent protein (GFP) virus, the endotoxin-induced mediators markedly reduced GFP expression from chimeric DHBV-GFP transcripts, indicating that the major effect is at a level of translation of viral RNAs. Taken together, the data obtained demonstrate that antiviral mediators, and among these the cytokines alpha interferon (IFN-α) and IFN-γ, are released from hepatic NPC, most probably liver macrophages, upon endotoxin stimulation; furthermore, these mediators act at a posttranscriptional step of hepadnavirus replication.

Hepatitis B viruses are small, enveloped hepatotropic DNA viruses (hepadnaviruses), that replicate their partially double-stranded DNA genome through reverse transcription of an RNA intermediate and therefore have been classified as pararetroviruses. Hepadnaviruses employ an episomal covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) as a nuclear transcription template and establish a cccDNA pool to regulate gene expression by copy number. They are noncytopathic viruses, often vertically transmitted, and establish a long-term persistent infection (for a review see references 10 and 31). This requires a well-balanced replication strategy that allows a variation in viral gene expression in response to changes of the state of the host hepatocyte as well as to extracellular stimuli.

An influence of the state of the cell is exemplified by aging cultured hepatocytes that vastly overamplify cccDNA; this suggests that regulatory mechanisms are evoked to compensate for reduced viral gene expression (48). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), which influences the state of differentiation of hepatocytes, improves the competence of cultured hepatocytes to efficiently replicate hepadnaviruses (9, 13). In duck hepatitis B virus (DHBV), the large envelope protein (L), although a structural viral protein, has been implicated in the regulation of cccDNA synthesis (46). More recent observations suggested that it is involved in cell-signaling, becoming phosphorylated in response to the state of the cell (37). Extracellular soluble mediators such as the cytokines alpha interferon (IFN-α) (34, 43, 44), IFN-γ, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) (15, 42), the peptide hormone glucagon (20), glucocorticoids, and androgens (7) have been shown to influence gene expression and replication of the hepatitis viruses.

In vivo, the liver is in permanent contact with endotoxin (lipopolysaccharide [LPS]), a constituent of the outer cell membrane of gram-negative bacteria. In the physiological situation, endotoxin derived from the large number of gram-negative bacteria in the intestinal lumen reaches the liver via the portal vein. In the liver, it is mainly eliminated by hepatic NPC, such as the resident macrophages, Kupffer cells, and liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (28). In particular, Kupffer cells are activated upon contact with endotoxin to release a variety of proinflammatory mediators such as TNF-α and prostaglandins (33). Hepatocytes also take up endotoxin and excrete it into the bile (30), but to date there is no evidence that hepatocytes are stimulated by endotoxin.

Macrophages such as Kupffer cells are key players in the innate immune response to bacterial as well as to viral infections. Activation of macrophages is associated with an increase in cytokine production, with an enhanced oxidative metabolism, and with an increase in phagocytotic activity. The major role of macrophages upon contact with the infectious agent is to recruit additional immune cells and effector molecules to the site of infection. Endotoxin stimulation of macrophages has been reported to suppress retroviral (1), reoviral (32), and vaccinia virus (36) replication. Cytokines or nitric oxid, at least in part, mediates this reduction. HIV replication can be enhanced by endotoxin-induced monokines (8), whereas endotoxin-induced chemokines suppress HIV infection in macrophages and T cells (50). In transgenic mice expressing the hepatitis B virus (HBV) envelope proteins, intraperitoneal injection of high doses of endotoxin was observed to negatively regulate expression of the hepatitis B surface antigen in the liver in vivo (12). It remains unknown, however, whether endotoxin influences viral replication in liver cells.

Accordingly, we wanted to investigate whether endotoxin influences hepadnavirus replication in cultured liver cells and to study the mode of action. We used the duck model of HBV infection (41), which allowed us to do controlled studies in the early stages of infection of primary duck hepatocyte cultures in vitro. Endotoxin was found to inhibit DHBV replication in duck hepatocytes in an indirect fashion. Inhibition occurred through the stimulation and release of soluble mediators from hepatic NPC, most probably Kupffer cells, present in the primary hepatocyte cultures. Our results indicate that the endotoxin-induced inhibition of DHBV replication occurs posttranscriptionally during the establishment of an intracellular viral replication cycle.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

LPS and lipid A from Salmonella minnesota, LPS from Escherichia coli 055:B5, and cell culture media and supplements were purchased from Sigma Chemicals Co. (St. Louis, Mo.). Cycloheximide and actinomycin D were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie (Deisenhofen, Germany). l-NG-monomethylarginine and indomethacin were purchased from Serva (Heidelberg, Germany). Duck interferons were produced in Cos7 cells (42) or in LMH cells (34) as described previously.

Isolation of primary duck hepatocytes.

Primary duck hepatocytes (PDH) were isolated by standard two-step collagenase perfusion and subsequent differential centrifugation essentially as described previously (9). Briefly, livers from 2- to 3-week-old ducklings were perfused via the portal vein and hepatocytes were sedimented three times at 50 × g and seeded at a density of 106 cells per ml (2 × 105/cm2) in 6- or 12-well plates or 60-mm-diameter dishes. Cells were maintained at 37°C (5% CO2) in supplemented Williams E medium (50 μg of gentamicin per ml, 50 μg of streptomycin per ml, 50 IU of penicillin per ml, 2.25 mM l-glutamine, 0.06% glucose, 23 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 4.8 μg of hydrocortisone per ml, 1 μg of inosine per ml, 1.5% DMSO) without the addition of serum.

Isolation and stimulation of hepatic NPC.

NPC (especially Kupffer cells and sinusoidal endothelial cells) are known to make up a significant portion of liver cells after collagenase perfusion (22). Liver cell cultures enriched for NPC were prepared by a two-step differential centrifugation of the total cell suspension from DHBV-negative ducklings obtained by two-step collagenase perfusion (2). Hepatocytes were removed by centrifugation at 50 × g. Subsequently, smaller NPC present in the supernatant were sedimented by centrifugation at 250 × g and seeded onto 6-well plates at a density of 107 cells/ml (2 × 106 cells/cm2) in the maintenance medium described above. Sinusoidal endothelial cells were purified from the NPC suspension by centrifugal counterflow elutriation (24). Cells were stimulated 24 h postplating with 20 ng of LPS per ml in maintenance medium for 3 h. After extensive washing to remove the LPS, the culture medium was collected after 12 h, centrifuged to remove cell debris, and stored at −70°C until further use. To obtain control supernatants, NPC were treated accordingly, except that no LPS was added. Unless otherwise stated, primary hepatocyte cultures were incubated with a 1:2 dilution of the NPC media during DHBV infection and subsequent cultivation.

Characterization of primary duck liver cell cultures.

Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells were identified by receptor-mediated uptake of acetylated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) (21), and Kupffer cells were identified as macrophages by phagocytosis. PDH cultures were incubated with either tetramethyl rhodamine isocyanate labeled, red fluorescent acetylated LDL (Dil-Ac-LDL; Paesel & Lorei, Duisburg, Germany [21]) or 1-μm-diameter amine-modified yellow-green fluorescent latex beads (Sigma-Aldrich Chemie [29]) for 2 to 3 h. After careful washing, labeled NPC were identified by fluorescence microscopy.

Characterization of the endotoxin-induced mediators.

To estimate the molecular weight of endotoxin-induced mediators, 2.5 ml of endotoxin-conditioned NPC medium was subjected to size exclusion chromatography on a Sephadex column with an exclusion limit of 5 × 103 for globular protein (PD10 columns; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) according to the manufacturer's instructions. One 3.5-ml fraction containing proteins with masses of >5 kDa and a second 5-ml fraction containing proteins with masses of <5 kDa were eluted.

To characterize the class of mediators, actinomycin D (100 ng/ml), an inhibitor of transcription; cycloheximide (20 μg/ml), an inhibitor of translation; indomethacin (500 nM), a cyclooxygenase inhibitor blocking prostaglandin synthesis; or l-N-monomethylarginine (47 nM), a competitive inhibitor of inducible nitric oxide synthase, was added to NPC cultures either with or without endotoxin. The doses of actinomycin D and cycloheximide were chosen to completely block synthesis of viral proteins after addition to hepatocyte cultures; the doses of indomethacin and l-NG-monomethylarginine were fivefold greater than the 50% inhibitory concentration.

To determine whether interferons are secreted by LPS-stimulated NPC, we monitored the accumulation of Mx and IRF-1 transcripts, as markers for the presence of IFN-α/β or IFN-γ, respectively, in PDH cultures by Northern blotting. Cells from a 60-mm-diameter dish (corresponding to 3.5 × 106 cells) were lysed 24 h after the addition of endotoxin-stimulated or control NPC medium, and total RNA was prepared with the RNeasy RNA preparation kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). RNA was size fractionated by electrophoresis through a 1.2% formaldehyde agarose gel and blotted onto a nylon membrane. The membranes were sequentially hybridized with radiolabeled chicken IRF-1 (23), duck Mx (4), and chicken glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) cDNA probes as described previously (42).

DHBV infection of primary duck hepatocytes.

For in vitro DHBV infection, a duck serum containing 1010 virions per ml (measured as enveloped DNA-containing particles) was used (20). Replication-deficient recombinant DHBV (rDHBV) in which the S gene was replaced by a green fluorescent protein (GFP) coding sequence (rDHBV-GFP) were produced as recently described (34), concentrated by precipitation with polyethylene glycol, and stored in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)–10% glycerol at −20°C. DHBV 16-containing duck serum was diluted in prewarmed maintenance medium to a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 50 virus particles (vp) per cell; rDHBV-GFP was diluted to an MOI of 100 or 150 vp/cell. Cells were infected overnight at 37°C at day 2 postplating in the presence or absence of LPS and/or other supplements as indicated below. The inoculum was washed off twice with Hank's buffered salt solution, and the cells were maintained as described above in the presence of the various supplements. Daily visual inspection of the cell cultures and crystal violet staining of living cells after up to 8 days of treatment revealed no evidence of a cytotoxic effect. The number of cells in treated and untreated cell cultures was determined by nuclear staining with Hoechst dye 33258. PDH with an established DHBV infection obtained from 2- to 3-week-old ducklings infected with 109 DHBV 16 particles the day after hatching were subjected to treatment from 2 h postplating until the end of the culture period.

Assays detecting DHBV infection. (i) Immunofluorescence staining of intracellular viral protein.

Cell monolayers were fixed with 100% methanol at −14°C at day 4 postinfection (p.i.). The number of infected cells was determined by immunofluorescence staining of intracellular viral antigens using a polyclonal rabbit antiserum recognizing the pre-S domain of DHBV L protein (39) and one recognizing the DHBV core protein (40) as well as a DTAF-labeled secondary goat-anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G antibody (Dianova, Hamburg, Germany).

(ii) Detection of GFP fluorescence.

Cells infected with rDHBV-GFP were monitored daily for green fluorescence by fluorescence microscopy using a standard fluorescein isothiocyanate filter set with excitation by blue light (488 nm) and photographed at maximal fluorescence.

(iii) Western blot analysis of intracellular viral proteins.

For Western blot analysis of intracellular viral protein, 106 primary hepatocytes were lysed at day 6 p.i. in 250 μl of protein sample buffer (200 mM Tris-Cl [pH 8.8], 10% glucose, 5 mM EDTA, 0.1% bromophenol blue, 3% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 2% β-mercaptoethanol). Twenty-five microliters (equivalent to 105 cells) of lysates of newly infected cells or 10 μl (equivalent to 4 × 104 cells) of lysates of cells from DHBV-infected ducklings was separated by SDS–10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and blotted to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and viral proteins were detected using the antisera against DHBV-L or -core protein or monoclonal antibody 4F8 recognizing amino acids 100 to 105 of the pre-S domain (kindly provided by Christa Kuhn, Zentrum für Molekulare Biologie, University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany) and an appropriate peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Dianova). Protein bands were visualized using the enhanced chemiluminescence system (ECL; Amersham, Cleveland, Ohio) or quantified on a fluoroimager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, Calif.) using the enhanced chemifluorescence system (ECF; Amersham).

(iv) DNA dot blot analysis of viral DNA.

A 50-μl volume (2 × 105 cells) of protein sample buffer lysate was digested with proteinase K (2 mg/ml in 250 μl of 10 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 100 mM NaCl, 25 mM EDTA, 0.5% SDS). Intracellular DNA was purified by standard phenol-chloroform extraction. DHBV DNA from 6 × 104 cells or 500 μl of cell culture medium (corresponding to 5 × 105 cells) was detected by dot blot hybridization with a 32P-labeled DHBV DNA probe (specific activity, ∼108 cpm/μg) and quantified using a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics). A dilution series of DHBV DNA served as a standard.

(v) Northern blot analysis of intracellular viral RNA.

Intracellular viral RNA was analyzed by Northern blot. Total RNA was prepared as described previously (3) from 8 × 106 hepatocytes isolated from DHBV-infected ducklings at the time points indicated or from 1.2 × 107 newly infected hepatocytes at day 4 p.i. mRNA was purified using oligo(dT)25-coated magnetic beads (Dynabeads; Dynal, Oslo Norway). Half of the mRNA was size fractionated by electrophoresis through a 1.0% formaldehyde agarose gel and blotted onto nylon membrane. Viral RNAs were detected using a 32P-labeled DHBV DNA probe, and chimeric DHBV-GFP RNAs were detected using a 32P-labeled GFP DNA probe.

(vi) Southern blot analysis of intracellular viral DNA.

cccDNA was isolated by a modification of the Hirt lysis method (46). Briefly, 4 × 106 PDH from a DHBV-positive duck or in vitro-infected PDH were lysed in 1 ml of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 10 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1% SDS). Protein-bound DNA was precipitated on ice for 5 min with 250 μl of 2.5 M KCl and removed by centrifugation. cccDNA was isolated from the supernatant by phenol-chloroform extraction, ethanol precipitated, and dissolved in 100 μl of 10 mM Tris–0.1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]. After RNase digestion (5 μg/ml, 15 min, 37°C), 25 μl of the DNA was analyzed by Southern blotting and DHBV DNA was detected by a 32P-labeled DHBV DNA probe.

RESULTS

Endotoxin inhibits DHBV replication in hepatocyte cultures.

To test whether endotoxin influences hepadnaviral replication in cultured primary duck hepatocytes, LPS was added in low physiological concentrations (11) to the hepatocyte medium during the DHBV infection period. In the presence of LPS, the amount of intracellular viral protein, as determined by Western blot analysis of cellular lysates, was reduced in a dose-dependent fashion. This was accompanied by a reduction in progeny DHBV release into the cell culture media, as determined by DHBV DNA dot blot analysis (Fig. 1). In different experiments, 10 pg to 10 ng of LPS/ml reduced the amount of progeny DHBV from day 4 to day 8 p.i. by two- to sixfold. No difference between various endotoxin preparations was observed. In contrast to LPS, the addition of lipid A, the conserved lipid constituent of LPS, showed no effect on DHBV replication in hepatocyte cultures (Fig. 1).

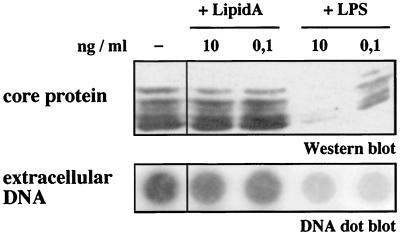

FIG. 1.

Endotoxin, but not lipid A, inhibits DHBV replication in vitro. When added to PDH cultures during DHBV infection, low concentrations of LPS inhibited DHBV core protein synthesis (shown by Western blot analysis of cellular lysates taken at day 8 p.i.) as well as DHBV progeny release (shown by dot blot analysis of cell culture media collected from day 4 to 8 postinfection). In contrast to LPS, lipid A, the lipid portion of endotoxin, did not elicit an inhibitory effect.

PDH cultures contain hepatic NPC.

The liver consists of various cell types, including hepatocytes which represent 60 to 65% of the liver cell population and NPC which account for 35 to 40% (2, 5). NPC include 15 to 20% sinusoidal endothelial cells, 8 to 12% Kupffer cells, and lower amounts of stellate cells, intrahepatic lymphocytes, and bile duct epithelial cells. Primary hepatocyte cultures from mouse or rat are known to contain 3 to 20% NPC (2, 22). Therefore, PDH cultures were analyzed for the presence of NPC, which may secrete mediators in response to endotoxin. For any given PDH preparation, 5 to 10% of the total number of cells were identified, by uptake of acetylated LDL, to be liver sinusoidal endothelial cells and 0.5 to 2% were identified, by phagocytosis of 1-μm-diameter beads, to be Kupffer cells (Fig. 2).

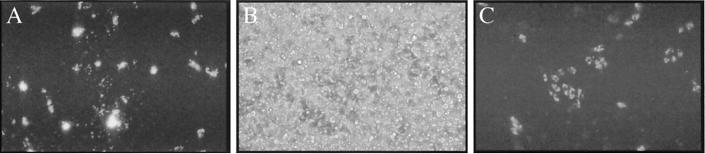

FIG. 2.

Characterization of NPC in PDH cultures. Liver macrophages (Kupffer cells) present in PDH cultures (B, phase contrast) were identified by their ability to phagocytose 1 μM green-fluorescent latex beads (A). Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells in the primary hepatocyte cultures were identified by receptor-mediated uptake of acetylated LDL labeled with a red-fluorescent dye (C).

Endotoxin stimulates hepatic NPC to secrete antiviral mediators.

To assess whether endotoxin elicits its effect via NPC stimulation, NPC cultures enriched by differential centrifugation for Kupffer cells by approximately 10-fold and sinusoidal endothelial cells enriched by approximately 2-fold were treated with endotoxin and supernatants were tested for an antiviral effect on hepatocyte cultures during DHBV infection. Significantly fewer hepatocytes treated with supernatant from endotoxin-treated NPC stained positive for intracellular DHBV core and L protein than untreated hepatocytes (compare Fig. 3A and B), whereas supernatants from unstimulated NPC showed no effect (Fig. 3C). In comparison, addition of LPS to hepatocyte cultures had an only minor effect (Fig. 3D). The number of cells in treated and untreated cell cultures was equivalent, as determined by nuclear staining (Fig. 3E and F), excluding a cytotoxic effect of the supernatant.

FIG. 3.

Soluble mediators secreted by endotoxin-stimulated liver macrophages inhibit DHBV infection of hepatocytes. Immunofluorescence staining of DHBV core and L protein in primary duck hepatocytes (day 4 p.i.) in untreated (A and E) and treated (B–D and F) hepatocyte cultures. The addition of supernatant of endotoxin-stimulated hepatic NPC significantly reduced the number of hepatocytes staining positive for the DHBV proteins (B), whereas the supernatant of unstimulated hepatic NPC showed no effect (C). Direct addition of endotoxin to hepatocyte cultures had an inferior effect (D). Nuclear staining proved that the same number of untreated cells (E) and cells treated with the supernatant of endotoxin-stimulated hepatic NPC (F) were stained. This identified mediators secreted by hepatic NPC after endotoxin stimulation to be responsible for the inhibition of DHBV replication.

Inhibition of DHBV replication diminished in a dose-dependent fashion (1:20 to 1:2,000 dilution) (Fig. 4) with little or no detectable progeny DHBV, intracellular DHBV DNA, or DHBV protein following incubation with maximal concentration (1:2 dilution) of supernatant from endotoxin-treated NPC (Fig. 4). In contrast, supernatants of endotoxin-treated purified duck liver sinusoidal endothelial cells did not inhibit DHBV replication (data not shown). From these data, we conclude that endotoxin inhibits productive DHBV infection indirectly: it stimulates hepatic NPC, most probably liver macrophages (Kupffer cells), to secrete soluble mediators.

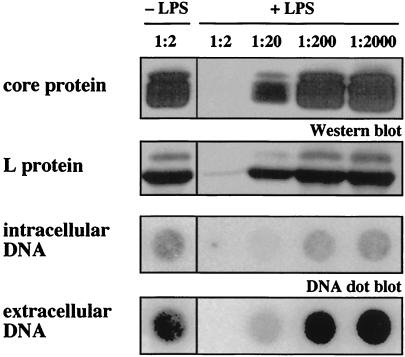

FIG. 4.

Endotoxin-induced mediators block DHBV replication in a dose-dependent fashion. Soluble mediators released by endotoxin-stimulated liver macrophages abrogated in primary hepatocytes the synthesis of intracellular DHBV core and L protein (Western blot analysis of hepatocyte lysates on day 8 p.i.), intracellular DHBV DNA (dot blot analysis of DNA extracted from hepatocyte lysates on day 8 p.i.) and DHBV progeny release (DNA dot blot analysis of cell culture medium collected from day 4 to 8 p.i.). The effect diminished in a dose-dependent fashion (+LPS); supernatants of unstimulated NPC (−LPS) did not affect DHBV replication.

Endotoxin induces expression of antiviral cytokines in hepatic NPC.

Endotoxin-induced mediators were analyzed for their approximate molecular weight by size exclusion chromatography. Two fractions containing molecules of <5 kDa or >5 kDa were tested for their antiviral effect when added during DHBV infection. Figure 5A shows that the inhibitory effect on DHBV replication (monitored by DHBV protein synthesis) was elicited by molecules with molecular masses greater than 5 kDa. Heat treatment for 10 min at 95°C inactivated the antiviral activity of the supernatant, indicating that the active component was proteinaceous (data not shown).

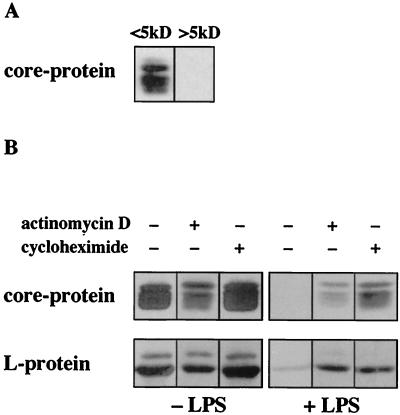

FIG. 5.

Endotoxin-induced mediators are polypeptides. (A) Supernatant of endotoxin-stimulated hepatic NPC was subjected to size exclusion chromatography. Fractions containing molecules with molecular masses of <5 kDa or >5 kDa, respectively, were added to primary hepatocytes during DHBV infection. Western blot analysis of DHBV core protein in primary hepatocytes (day 7 p.i.) revealed that mediators of >5 kDa were responsible for the inhibitory effect on DHBV replication. (B) Addition of protein synthesis inhibitors actinomycin D and cycloheximide during endotoxin stimulation (+LPS) prevented production of inhibitory mediators by hepatic NPC (Western blot analysis of intracellular DHBV core and L protein in hepatocyte lysates day 7 p.i.). Supernatant of unstimulated non-parenchymal liver cells (−LPS) used as a control did not affect DHBV protein synthesis in duck hepatocytes.

Inhibition of protein synthesis (by actinomycin D and cycloheximide) during endotoxin stimulation largely abolished the production of the antiviral mediators (Fig. 5B). In contrast, neither the addition of indomethacin, an inhibitor of prostaglandin synthesis, nor the addition of l-NG-monomethylarginine, a blocker of the inducible nitric oxide synthase to NPC cultures during endotoxin stimulation, had any effect (data not shown). Taken together, these data showed that polypeptides, most probably cytokines, are the responsible antiviral mediators secreted by NPC upon endotoxin challenge.

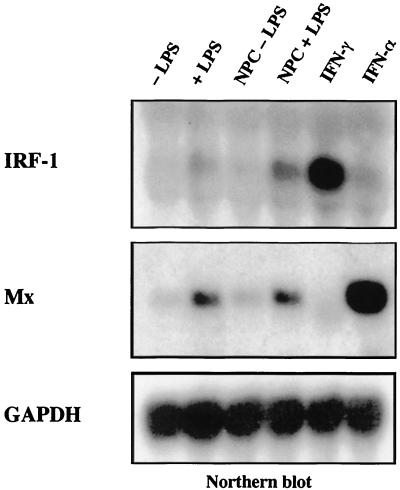

Northern blot analysis of RNA extracted from lysates of treated, untreated, and mock-treated hepatocyte cultures revealed that Mx and IRF-1 transcripts were upregulated in hepatocyte cultures treated either with 10 ng of endotoxin per ml or with the endotoxin-induced mediators (1:2 dilution) (Fig. 6). The gene encoding Mx is induced by IFN-α, while IRF-1 transcription is mainly induced by IFN-γ (IRF-1) (Fig. 6, last two lanes [42]). This result suggests that supernatants of endotoxin-stimulated NPCs contain the cytokines IFN-α and IFN-γ.

FIG. 6.

IFN-α and IFN-γ are released after endotoxin treatment. Hepatocyte cultures were treated either with endotoxin (+LPS), with plain medium (−LPS), with supernatant from endotoxin stimulated (NPC + LPS), with supernatant from unstimulated hepatic NPC (NPC − LPS), or with supernatants from COS cells transfected with expression constructs encoding duck IFN-γ or duck IFN-α and lysed 24 h after treatment. Samples (10 μg) of total RNA were analyzed by Northern blotting. The blot was sequentially hybridized with radiolabeled chicken IRF-1, duck Mx, and chicken GAPDH cDNA probes as described previously (42). IRF-1 transcripts accumulate after treatment of cells with IFN-γ; Mx transcripts accumulate after treatment of cells with IFN-α. IRF-1 as well as Mx genes were induced in hepatocyte cultures treated either with LPS or with endotoxin-induced mediators released by nonparenchymal liver cells, indicating that both cytokines were among the endotoxin-induced mediators.

Endotoxin-induced mediators interfere with accumulation of progeny DHBV cccDNA.

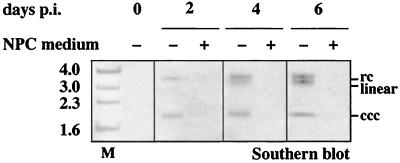

As shown in Fig. 4, intracellular viral proteins, total intracellular DHBV-DNA and progeny virus production were reduced in parallel after addition of the endotoxin-induced mediators, suggesting that an early step during the establishment of an intracellular DHBV replication was affected. In time-course experiments, an identical inhibitory effect was also observed when the endotoxin-induced mediators were added up to 24 h after termination of DHBV infection by exposure to pH 2.2. A reduced inhibition was observed when endotoxin-induced mediators were added 48 h p.i. (data not shown). This timespan coincides with the time of initial amplification of nuclear cccDNA in vitro (20, 25). Southern blot analysis confirmed that the treatment blocked the accumulation of progeny cccDNA after DHBV infection (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Endotoxin-induced mediators inhibit accumulation of cccDNA after DHBV infection. Primary duck hepatocytes were infected with DHBV at day 2 postplating with (+) or without (−) the addition of medium from endotoxin-stimulated NPC. DHBV cccDNA was isolated from duck hepatocytes at the time indicated and subjected to Southern blot analysis. Gel migration positions of relaxed circular (rc), linear, and covalently closed circular (ccc) forms of viral DNA are indicated. In cells treated with endotoxin-induced mediators released by hepatic NPC, the accumulation of progeny cccDNA was observed in the untreated cells after DHBV infection was blocked. M, marker.

Endotoxin-induced mediators affect hepadnaviral gene expression.

To further define the step during intracellular DHBV replication which was blocked by the endotoxin-induced mediators, we used PDH isolated from an DHBV-infected duckling. In contrast to in vitro-infected PDH, an intracellular replication cycle was already established in these cells.

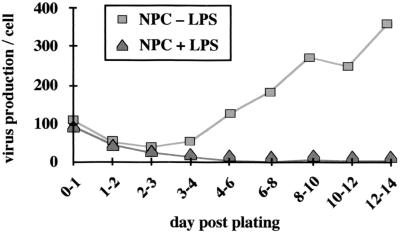

As depicted in Fig. 8, hepatocytes with an established DHBV infection showed significant variation in virus production depending on the time postplating. Preformed virus was released during the first 24 h postplating; then DHBV production decreased two- to threefold by day 3; thereafter, virus production again increased until it reached a constant level around day 8. If these cells were treated with endotoxin-induced mediators directly after plating, progeny virus production was reduced from day 2 to 4 postplating; from day 4 postplating, progeny production was undetectable by DHBV DNA dot blot (Fig. 8). Even if only added from day 5 postplating, endotoxin-induced mediators resulted in a continuous reduction of progeny virus production (4-fold at day 11, about 50-fold at day 21 postplating [data not shown]).

FIG. 8.

Endotoxin-induced mediators block progeny virus production by hepatocytes with an established DHBV infection. Hepatocytes with an established DHBV infection show significant changes in virus production depending on the time postplating: preformed virus is released directly after plating before DHBV production goes down until day 3 postplating (quantitation of extracellular DHBV-DNA after dot blot analysis of cell culture media). From day 4 postplating, virus production increases again until it reaches a constant level around day 8 postplating. When endotoxin-induced mediators were added to these cells, initial virus release was identical to that from cells treated with supernatant from unstimulated NPC. After 2 days, progeny virus production decreased in treated cells and stayed at a low level.

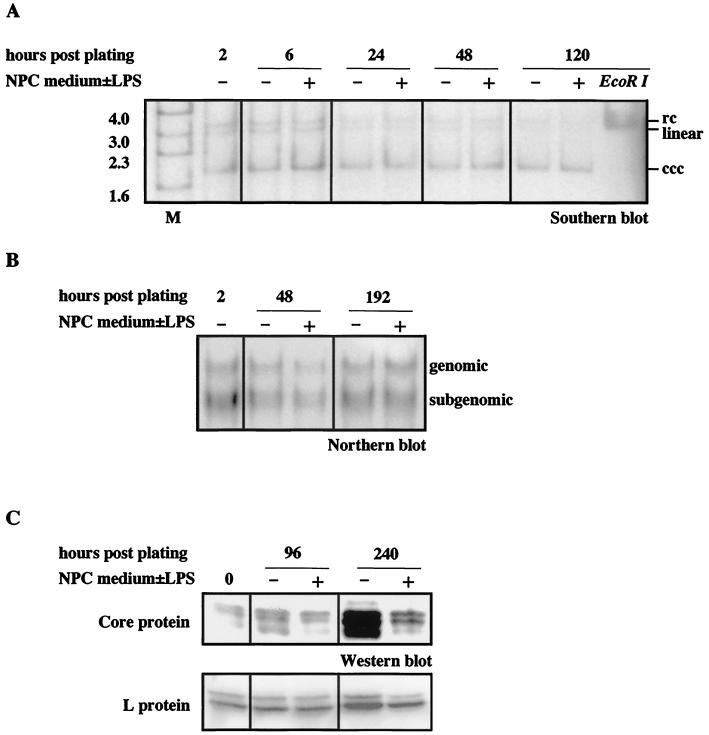

Treatment with the endotoxin-induced mediators during the whole culture period, however, diminished neither preexisting cccDNAs serving as transcription templates (as analyzed by Southern blotting [Fig. 9A]) nor genomic or subgenomic viral transcripts (as analyzed by Northern blotting [Fig. 9B]). In the same cells, the amount of relaxed circular and single-stranded replicative intermediates was reduced by a factor of three (at day 6 postplating) with single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) being reduced earlier (from day 1 postplating) than relaxed circular DNA (rcDNA) (after day 2 postplating). Levels of viral proteins were also reduced during treatment (as shown by Western blotting [Fig. 9C]). Quantitation using a fluoroimager revealed a threefold reduction of the amount of core and L protein at day 10 postplating in cells treated with the endotoxin-induced mediators. Metabolic 35S-labeling of the cells also showed a two- to threefold reduction of L protein synthesis in treated cells, whereas the amount of cellular proteins was equal in treated and untreated cells (data not shown). Taken together, these data suggest that the endotoxin-induced mediators interfere with a posttranscriptional step required for intracellular DHBV replication.

FIG. 9.

Viral cccDNA and transcript levels are not influenced by endotoxin-induced mediators in hepatocytes with an established infection. Hepatocytes used were isolated from an DHBV-infected duckling, and endotoxin-induced mediators were added to these cells directly postplating. The amount of DHBV cccDNA during treatment was determined by Southern blot analysis (A), the amount of DHBV RNAs was determined by Northern blot analysis (B), and the amount of DHBV core and L protein was determined by Western blot anlysis (using ECL for detection of core and ECF for detection of L protein on the same blot) (C). No changes in the level of cccDNA or of viral RNAs were observed, whereas protein levels were significantly reduced during treatment with endotoxin-induced mediators (+) in comparison to untreated (−) cells. Duck hepatocytes were lysed for isolation of viral nucleic acids and for analysis of viral proteins at the time point indicated. Gel migration positions of relaxed circular (rc), linear, and covalently closed circular (ccc) forms of viral DNA (A) and of pregenomic and subgenomic RNAs (B) are indicated. M, marker.

Endotoxin-induced mediators act before encapsidation of viral RNAs.

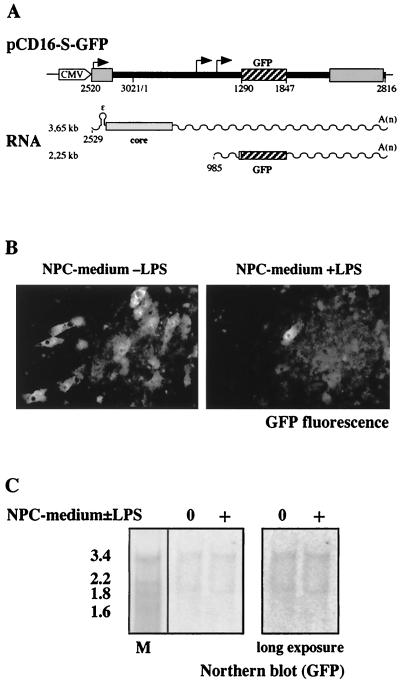

To distinguish whether the antiviral effect of endotoxin-induced mediators is at the level of translation or encapsidation of viral RNAs or whether it requires formation of viral capsids, we used rDHBV-GFP, a recombinant, replication-deficient DHBV carrying a GFP gene as described recently (34). In the rDHBV genome, the S coding region is exchanged for a GFP coding region which disrupts the overlapping viral polymerase open reading frame (Fig. 10A) (3). Because polymerase is lacking, pregenomic RNA cannot be encapsidated and reverse transcribed and amplification of the viral genome is prevented (3). GFP and DHBV core protein are the only gene products expressed from the incoming viral genome (Fig. 10A).

FIG. 10.

Expression of GFP after infection with a recombinant DHBV transferring a GFP gene is markedly reduced by endotoxin-induced mediators. Primary duck hepatocytes were infected with rDHBV-GFP at an MOI of 150 vp/cell. rDHBV-GFP is produced using construct pCD16-S-GFP as recently described (34). After infection, chimeric DHBV-GFP pregenomic (3.65-kb) and subgenomic (2.25-kb) messages are detected in which GFP sequences are flanked by the authentic DHBV sequences including the complete untranslated 5′ leader, the authentic AUG, and the first four codons of the S-message as well as 3′ DHBV sequences up to the DHBV polyadenylation site (A). Fluorescence microscopy of infected cells (B) revealed that in untreated cultures, markedly more hepatocytes expressed GFP at a detectable level than in cultures treated with supernatant from endotoxin-stimulated NPC. By Northern blot analysis using a GFP probe (C), however, the amount of GFP-containing transcripts was equal in treated and untreated cells at day 4 p.i.

Although the number of hepatocytes which expressed GFP at a detectable level was reduced at least 20-fold (Fig. 10B), the number of chimeric DHBV-GFP transcripts remained constant (Fig. 10C) when endotoxin-induced mediators were present during rDHBV-GFP infection. This shows that the same number of cells was infected in treated and untreated cultures and that transcriptional activity from the incoming DHBV-GFP genome was unchanged. It may be important that the expression level of GFP varies markedly between infected cells on the same dish (34). A few cells always remain unaffected by the treatment after infection with DHBV-GFP, as in infection with DHBV. Together with the data presented above, the reduction of GFP expression therefore strongly suggests that translation from viral transcripts is affected. This experiment shows, in addition, that the endotoxin-induced mediators elicit an effect prior to encapsidation of pregenomic RNA.

DISCUSSION

The data presented here demonstrate that endotoxin inhibits hepadnavirus replication in vitro in an indirect, noncytopathic fashion: it stimulates hepatic NPC, most probably liver macrophages, to secrete soluble antiviral mediators. When present during DHBV infection of duck hepatocytes, the antiviral mediators blocked intracellular viral protein synthesis and progeny virus production as well as cccDNA amplification, indicating that an early step of the DHBV replication cycle was affected. In hepatocytes isolated from a DHBV-infected duck, in which the intracellular replication cycle and a cccDNA pool were already established, viral protein synthesis was reduced and progeny virus production was blocked but cccDNAs and viral transcripts remained unaffected. These data strongly suggest that endotoxin-induced mediators act at a posttranscriptional step rather than affecting the initial steps of DHBV infection such as virus uptake, nuclear import of the viral genome, or conversion of the viral genome into nuclear cccDNA.

In addition, we showed that GFP expression was inhibited after infection with a replication-deficient recombinant virus, DHBV-GFP (34), which does not encapsidate pregenomic RNA and thus expresses GFP from the incoming viral genome. The number of chimeric DHBV-GFP genomic and subgenomic transcripts present, however, was not affected. GFP is translated from the subgenomic DHBV-GFP transcript which contains the authentic, relatively long 300-nucleotide leader, the authentic start codon plus the first three codons of the S-message and authentic 3′ sequences (Fig. 10A). These results led us to the conclusion that the block caused by the endotoxin-induced mediators is posttranscriptional. The major block appears to be prior to encapsidation, most probably at the level of translation of viral RNAs, but an additional effect on a latter step cannot be excluded.

Endotoxin is known to act mainly on monocytes and macrophages to produce and release a broad range of proinflammatory mediators: cytokines, chemokines, lipid mediators such as leukotrienes or prostaglandins, and low-molecular-weight oxygen radicals, peroxide, and nitric oxide (38, 47). In our studies, in which cultures of hepatic NPC stimulated with endotoxin secreted antiviral mediators, polypeptides were identified to be responsible for the antiviral effect. IFN-α (43) and IFN-γ (42), the only duck cytokines known so far, were identified to be among these mediators. Unfortunately, cytokines such as TNF-α, involved in regulation of HBV replication (16) and known to be induced by endotoxin (33), have not yet been characterized in the duck and thus could not be tested for. Furthermore, no blocking antibody to any duck cytokine is available to determine to which extent different cytokines contribute to the antiviral effect.

NPC preparations containing mainly Kupffer cells, the resident macrophages of the liver, but not purified sinusoidal liver endothelial cells did secrete antiviral mediators upon endotoxin stimulation. This suggests that Kupffer cells mediate the inhibitory effect of endotoxin on hepadnavirus replication. In most macrophages and in peripheral blood mononuclear cells, CD14 functions as the receptor for bacterial endotoxin. CD14 recognizes a complex of LPS and LPS-binding protein, which is an excess serum protein. LPS binds to LPS-binding protein via its lipid portion, lipid A (49). In our experiments, the addition of serum containing LPS-binding protein was not necessary for the endotoxin stimulation and lipid A could not substitute for LPS. Recently, it was reported that the Kupffer cells, unlike other tissue macrophages, do not bind endotoxin via CD14 (27). In addition to the above mentioned experimental data, this supports our conjecture that Kupffer cells are responsible for the cytokine-mediated suppression of hepadnaviral replication.

In HBV transgenic mice, it has been highlighted that cytotoxic T lymphocytes can inhibit HBV gene expression and replication noncytopathically by secreting antiviral cytokines (i.e., IFN-α, IFN-γ, and TNF-α), which interrupt HBV replication (14, 15). In chimpanzees with acute HBV infection, noncytopathic antiviral mechanisms are mainly responsible for clearance of HBV infection (16). Cytokines were reported to activate two different pathways in vivo in HBV transgenic mice: firstly, replicative viral intermediates contained in nucleocapsids were removed from the cytoplasm (15); secondly, viral RNAs were destabilized posttranscriptionally (15, 17, 18). Recently, La autoantigen was identified in transgenic mice as an RNA-binding protein that binds to HBV transcripts and is associated with a cytokine-induced clearance of viral RNA from the liver (18, 19). In our experiments employing hepatocytes with an established DHBV infection and an established pool of viral transcripts as in the transgenic mice the number of transcripts remained constant. A similar phenomenon was reported when the HBV transgenic mice were treated with interleukin-12 (6) that induced IFN-α/β, TNF-α, and IFN-γ. Perhaps posttranscriptional degradation of hepadnaviral transcripts requires higher doses of cytokines than inhibition of translation of hepadnaviral proteins.

In vitro infection experiments employing DHBV suggested that in the presence of IFN-α viral capsids containing pregenomic RNA were selectively depleted from the cytoplasm of newly infected hepatocytes. In addition, IFN-α inhibited a core protein-dependent accumulation of viral transcripts (44). Studies in the same system showed that IFN-γ inhibited DHBV replication after initial conversion of the viral genomic DNA into cccDNA, but before the accumulation of progeny cccDNA; it seemed to inhibit the accumulation of ssDNA-containing capsids during reverse transcription or an earlier step in the viral replication cycle (42). In our experiments employing various cytokines, an inhibitory effect was observed independent of the encapsidation of pregenomic RNA. We cannot, however, exclude an additional effect on viral capsids.

The mechanism by which the endotoxin-induced cytokines block hepadnaviral replication in the hepatocyte remains unknown. Cytokines could directly elicit their antiviral effect in the hepatocyte. Alternatively, they could stimulate NPC or even hepatocytes to secrete antiviral effectors. In initial experiments, endotoxin-induced mediators did not elicit their inhibitory effect when inducible nitric oxide synthase was blocked in hepatocyte cultures, suggesting that nitric oxide may be such an antiviral effector. This hypothesis is in accordance with recent observations that Kupffer cells induce nitric oxide production in hepatocytes upon endotoxin challenge (45) and that nitric oxide is one of the key regulators of infection with different pathogens (26, 35). Taken together, the results obtained in this study further strengthen our notion that hepadnavirus gene expression and replication are very sensitive to extracellular stimuli that influence the state of the host cell.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Heike Oberwinkler for excellent technical assistance, Bärbel Glass for providing primary duck hepatocytes and DHBV16, Silke Hegenbarth for providing liver sinusoidal endothelial cells, and Percy Knolle, Stephan Urban, Andreas Limmer, and Elizabeth Grgaczic for discussion and helpful comments.

The work was in part supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (PR 618-1) and from the BMBF (01KV9516/3). Uta Klöcker received a fellowship from the Graduiertenkolleg “Gene Expression of Pathogenic Microorganisms” of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. Ulrike Protzer is supported by a “Habilitationsprogramm der Ruprecht Karls-Universität Heidelberg”.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akarid K, Sinet M, Desforges B, Gougerot P M. Inhibitory effect of nitric oxide on the replication of a murine retrovirus in vitro and in vivo. J Virol. 1995;69:7001–7005. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.7001-7005.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alpini G, Phillips J O, Vroman B, LaRusso N F. Recent advances in the isolation of liver cells. Hepatology. 1994;20:494–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartenschlager R, Junker Niepmann M, Schaller H. The P gene product of hepatitis B virus is required as a structural component for genomic RNA encapsidation. J Virol. 1990;64:5324–5232. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.11.5324-5332.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bazzigher L, Schwarz A, Staeheli P. No enhanced influenza virus resistance of murine and avian cells expressing cloned duck Mx protein. Virology. 1993;195:100–112. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blouin A, Bolender R P, Weibel E R. Distribution of organelles and membranes between hepatocytes and nonhepatocytes in the rat liver parenchyma. A stereological study. J Cell Biol. 1977;72:441–445. doi: 10.1083/jcb.72.2.441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cavanaugh V J, Guidotti L G, Chisari F V. Interleukin-12 inhibits hepatitis B virus replication in transgenic mice. J Virol. 1997;71:3236–3243. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.3236-3243.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farza H, Salmon A, Hadchouel M, Tiollais P, Pourcel C. Hepatitis B surface antigen expression is regulated by sex steroids and glucocorticoids in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:1187–1191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.5.1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Folks T M, Clouse K A, Justement A, Rabson A, Duh E, Kehrl J H, Fauci A S. Tumor necrosis factor alpha induces expression of human immunodeficiency virus in a chronically infected T cell clone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:2365–2368. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.7.2365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galle P R, Schlicht H J, Kuhn C, Schaller H. Replication of duck hepatitis B virus in primary duck hepatocytes and its dependence on the state of differentiation of the host cell. Hepatology. 1989;10:459–465. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840100410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ganem D. Hepadnaviridae: the viruses and their replication. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 2703–2737. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gathiram P, Wells M T, Raidoo D, Brock U J, Gaffin S L. Changes in lipopolysaccharide concentrations in hepatic portal and systemic arterial plasma during intestinal ischemia in monkeys. Circ Shock. 1989;27:103–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilles P N, Fey G, Chisari F V. Tumor necrosis factor alpha negatively regulates hepatitis B virus gene expression in transgenic mice. J Virol. 1992;66:3955–3960. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.6.3955-3960.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gripon P, Diot C, Corlu A, Guguen Guillouzo C. Regulation by dimethylsulfoxide, insulin, and corticosteroids of hepatitis B virus replication in a transfected human hepatoma cell line. J Med Virol. 1989;28:193–199. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890280316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guidotti L G, Borrow P, Hobbs M V, Matzke B, Gresser I, Oldstone M B, Chisari F V. Viral cross talk: intracellular inactivation of the hepatitis B virus during an unrelated viral infection of the liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:4589–4594. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.4589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guidotti L G, Ishikawa T, Hobbs M V, Matzke B, Schreiber R, Chisari F V. Intracellular inactivation of the hepatitis B virus by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Immunity. 1996;4:25–36. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80295-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guidotti L G, Rochford R, Chung J, Shapiro M, Purcell R, Chisari F V. Viral clearance without destruction of infected cells during acute HBV infection. Science. 1999;284:825–829. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guilhot S, Guidotti L G, Chisari F V. Interleukin-2 downregulates hepatitis B virus gene expression in transgenic mice by a posttranscriptional mechanism. J Virol. 1993;67:7444–7449. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.7444-7449.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heise T, Guidotti L G, Cavanaugh V J, Chisari F V. Hepatitis B virus RNA-binding proteins associated with cytokine-induced clearance of viral RNA from the liver of transgenic mice. J Virol. 1999;73:474–481. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.474-481.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heise T, Guidotti L G, Chisari F. La autoantigen specifically recognizes a predicted stem-loop in hepatitis B virus RNA. J Virol. 1999;73:5767–5776. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5767-5776.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hild M, Weber O, Schaller H. Glucagon treatment interferes with an early step of duck hepatitis B virus infection. J Virol. 1998;72:2600–2606. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.2600-2606.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Irving M G, Roll F J, Huang S, Bissell D M. Characterization and culture of sinusoidal endothelium from normal rat liver: lipoprotein uptake and collagen phenotype. Gastroenterology. 1984;87:1233–1247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnston D E, Jasuja R. Purification of cultured primary rat hepatocytes using selection with ricin A subunit. Hepatology. 1994;20:436–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jungwirth C, Rebbert M, Ozato K, Degen H J, Schultz U, Dawid I B. Chicken interferon consensus sequence-binding protein (ICSBP) and interferon regulatory factor (IRF) 1 genes reveal evolutionary conservation in the IRF gene family. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3105–3109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knolle P A, Loser E, Protzer U, Duchmann R, Schmitt E, Meyer zum Büschenfelde K, Rosejohn S, Gerken G. Regulation of endotoxin-induced IL-6 production in liver sinusoidal endothelial cells and Kupffer cells by IL-10. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;107:555–561. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1997.d01-959.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Köck J, Schlicht H J. Analysis of the earliest steps of hepadnavirus replication: genome repair after infectious entry into hepatocytes does not depend on viral polymerase activity. J Virol. 1993;67:4867–4874. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.4867-4874.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Komatsu T, Srivastava N, Revzin M, Ireland D D, Chesler D, Shoshkes Reiss C. Mechanisms of cytokine-mediated inhibition of viral replication. Virology. 1999;259:334–341. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lichtman S N, Wang J, Lemasters J J. LPS receptor CD14 participates in release of TNF-alpha in RAW 264.7 and peritoneal cells but not in kupffer cells. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:G39–G46. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.275.1.G39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mathison J, Ulevitch R. The clearance, tissue distribution and cellular localization of intravenously injected lipopolysaccharide in rabbits. J Immunol. 1979;123:2133–2143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCuskey R S, McCuskey P A, Urbaschek R, Urbaschek B. Species differences in Kupffer cells and endotoxin sensitivity. Infect Immun. 1984;45:278–280. doi: 10.1128/iai.45.1.278-280.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mimura Y, Sakisaka S, Harada M, Sata M, Tanikawa K. Role of hepatocytes in direct clearance of lipopolysaccharide in rats. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:1969–1976. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90765-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nassal M, Schaller H. Hepatitis B virus replication—an update. J Viral Hepat. 1996;3:217–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.1996.tb00047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pertile T L, Karaca K, Sharma J M, Walser M M. An antiviral effect of nitric oxide: inhibition of reovirus replication. Avian Dis. 1996;40:342–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peters T, Karck U, Decker K. LPS activation of rat Kupffer cells—participation of tumor necrosis factor, prostaglandin E2, glucocorticoids and protein synthesis. In: Wisse E, Knook D L, McCuskey R S, editors. Cells of the hepatic sinusoid. Vol. 3. Leiden, The Netherlands: The Kupffer Cell Foundation; 1991. pp. 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Protzer U, Nassal M, Chiang P W, Kirschfink M, Schaller H. Interferon gene transfer by a hepatitis B virus vector efficiently suppresses wild-type virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:10818–10823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rimmelzwaan G F, Baars M M, de Lijster P, Fouchier R A, Osterhaus A D. Inhibition of influenza virus replication by nitric oxide. J Virol. 1999;73:8880–8883. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8880-8883.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rolph M S, Ramshaw I A, Rockett K A, Ruby J, Cowden W B. Nitric oxide production is increased during murine vaccinia virus infection, but may not be essential for virus clearance. Virology. 1996;217:470–477. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rothmann K, Schnoelzer M, Radziwill G, Hildt E, Moelling K, Schaller H. Host cell-virus crosstalk: phosphorylation of a hepatitis B virus envelope protein mediates intracellular signalling. J Virol. 1998;72:10138–10147. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.10138-10147.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schletter J, Heine H, Ulmer A J, Rietschel E T. Molecular mechanisms of endotoxin activity. Arch Microbiol. 1995;164:383–389. doi: 10.1007/BF02529735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schlicht H J, Kuhn C, Guhr B, Mattagliano R J, Schaller H. Biochemical and immunological characterization of the duck hepatitis B virus envelope proteins. J Virol. 1987;61:2280–2285. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.7.2280-2285.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schlicht H J, Salfeld J, Schaller H. The duck hepatitis B virus pre-C region encodes a signal sequence which is essential for synthesis and secretion of processed core proteins but not for virus formation. J Virol. 1987;61:3701–3709. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.12.3701-3709.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schödel F, Weimer T, Fernholz D, Schneider R, Sprengel R, Wildner G, Will H. The biology of avian hepatitis B viruses. In: McLachlan A, editor. Molecular biology of the hepatitis B virus. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1991. pp. 53–80. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schultz U, Chisari F V. Recombinant duck interferon gamma inhibits duck hepatitis B virus replication in primary hepatocytes. J Virol. 1999;73:3162–3168. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.3162-3168.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schultz U, Köck J, Schlicht H J, Staeheli P. Recombinant duck interferon: a new reagent for studying the mode of interferon action against hepatitis B virus. Virology. 1995;212:641–649. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schultz U, Summers J, Staeheli P, Chisari F V. Elimination of duck hepatitis B virus RNA-containing capsids in duck interferon-alpha-treated hepatocytes. J Virol. 1999;73:5459–5465. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5459-5465.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shiratori Y, Ohmura K, Hikiba Y, Matsumura M, Nagura T, Okano K, Kamii K, Omata M. Hepatocyte nitric oxide production is induced by Kupffer cells. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:1737–1745. doi: 10.1023/a:1018879502520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Summers J, Smith P M, Horwich A L. Hepadnavirus envelope proteins regulate covalently closed circular DNA amplification. J Virol. 1990;64:2819–2824. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.6.2819-2824.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sweet M J, Hume D A. Endotoxin signal transduction in macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 1996;60:8–26. doi: 10.1002/jlb.60.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tuttleman J S, Pourcel C, Summers J. Formation of the pool of covalently closed circular viral DNA in hepadnavirus-infected cells. Cell. 1986;47:451–460. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90602-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ulevitch R, Tobias P. Receptor-dependent mechanism of cell stimulation by bacterial endotoxin. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:437–457. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.002253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Verani A, Scarlatti G, Comar M, Tresoldi E, Polo S, Giacca M, Lusso P, Siccardi G, Vercelli D. C-C chemokines released by lipopolysaccharide-stimulated human macrophages suppress HIV-1 infection in both macrophages and T cells. J Exp Med. 1997;185:805–816. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.5.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]