Clinical governance was the centrepiece of an NHS white paper introduced soon after the Labour government came into office in the late 1990s.1 The white paper provides the framework to support local NHS organisations as they implement the statutory duty of quality, which was placed on them through the 1990 NHS act.2 Clinical governance provides the opportunity to understand and learn to develop the fundamental components required to facilitate the delivery of quality care—a no blame, questioning, learning culture, excellent leadership, and an ethos where staff are valued and supported as they form partnerships with patients. These elements have perhaps previously been regarded as too intangible to take seriously or attempt to improve. Clinical governance demands the re-examination of traditional roles and boundaries—between health professions, between doctor and patient, and between managers and clinicians—and provides the means to show the public that the NHS will not tolerate less than best practice.

In 1998 Scally and Donaldson set out the vision of clinical governance: “A framework through which NHS organisations are accountable for continually improving the quality of their services and safeguarding high standards of care by creating an environment in which excellence in clinical care will flourish.”3 In this paper we take the story forward. Two years on, how is clinical governance faring in the NHS, and, with the advent of the national plan for the NHS,4 how is it being developed in practical terms?

Summary points

Clinical governance represents the systematic joining up of initiatives to improve quality

Since the introduction of governance in the NHS, structures have been put in place to set standards and ensure that they are met

New approaches are needed to leadership, strategic planning, patient involvement, and management of staff and processes

The NHS Clinical Governance Support Team is providing task based training for health professionals, who learn as they do

Why clinical governance?

For most of its first 40 years the NHS worked with an implicit notion of quality, building on the philosophy that the provision of well trained staff, good facilities, and equipment was synonymous with high standards. The quality initiatives that followed, such as medical and clinical audit, took a more systematic approach. However, they were often criticised as professionally dominated and somewhat insular activities whose benefits were not readily apparent to the health service or to patients.5

During the 1980s, managers and policymakers in many parts of the public sector, including health care, tried to apply the approaches of total quality management and continuous quality improvement. These approaches, which were developed in Japanese industry,6,7 were not widely accepted, perhaps because they were viewed as too management driven with no clearly identified role for clinical staff.

An internal market was introduced into the NHS in the early 1990s, but there was little evidence that opportunities were taken to embed quality improvements into the health service at a structural level.8 However, around the same time the NHS was given a national research and development function, and this forced it to re-examine of the role of clinical decision making in improving quality. Adoption of the philosophy of evidence based medicine9 has resulted in more effective and consistent transfer of the lessons of research into routine practice. This has been carried forward as a core component of clinical governance.

Clinical governance was introduced at the end of a decade in which quality had been more explicitly addressed than ever before. It offers a means to integrate previously rather disparate and fragmented approaches to quality improvement—but there was another driver for change. The series of high profile failures in standards of NHS care in Britain over the past five years10–12 caused deep public and professional concern and threatened to undermine confidence in the NHS. Unwittingly, these events seem to have fulfilled a key criterion for achieving successful change in organisations—the need to establish a sense of urgency.13

Framework to support quality improvement

Clinical governance is the central element of a framework that supports the delivery of quality. The box lists the national structures and mechanisms that help to develop and reinforce local clinical governance. The National Institute for Clinical Excellence and national service frameworks are important in setting quality standards. The National Institute for Clinical Excellence has a key role in appraising new technology (such as drugs and medical devices), providing guidance on the appropriate use of treatment interventions and procedures, and developing clinical guidelines for the management of specific diseases. The institute also produces clinical audit tools to support clinicians in local clinical governance activities. National service frameworks define evidence based best practice for specific chronic diseases or patient groups.14 The standard setting mechanisms of these bodies are reinforced by the Commission for Health Improvement, which inspects clinical governance arrangements and provides feedback to local NHS organisations to inform development.

Key elements of the NHS quality strategy

Standards:National Institute for Clinical ExcellenceNational service frameworks

Local duty of quality:Clinical governanceControls assurance

Assuring quality of individual practice:NHS performance proceduresAnnual appraisalRevalidation

Scrutiny:Commission for Health ImprovementEducational inspection visits

Learning mechanisms:Adverse incident reportingLearning networksContinuing professional development

Patient empowerment:Better informationNew patient advocacy serviceRights of redressPatients' views soughtPatients involved throughout the NHS

Underpinning strategies:Information and information technologyResearch and developmentEducation and training

Policies to deal with poor practitioner performance15 and to learn effectively from adverse events and errors16 have been added to clinical governance structures to improve the safety of the clinical environment. The national system of rapid assessment to examine concerns about a doctor's practice will enable poor performance to be recognised earlier and tackled through a range of flexible interventions. It will also be more effectively linked to a reformed system of professional regulation.17

The NHS plan has strengthened ways in which patient and citizen participation can influence the quality of health services.4 A patient advocacy and liaison service will be established, and patient advocate teams (with access to chief executives and with their own executive powers) will be available for patients and their families. The plan commits the NHS to improving patient information, consent, and participation. There will be patients' forums and more lay contribution through trust boards to the work of the National Institute of Clinical Excellence, Commission for Health Improvement, and professional regulatory bodies, as well as to the work of the new NHS Modernisation Board. A new NHS charter will formalise these commitments.

What might clinical governance look like on the ground?

From listening to NHS audiences across England over the past two years, we sense that healthcare professionals feel clinical governance is the right idea. Most want to work in an organisation with a strong positive culture of teamwork, and all want to find better ways to deliver quality care.

Delivery of clinical governance will include new approaches to leadership, strategic planning for quality, patient involvement, information and analysis, the management of staff, and process management. There is no one way to develop each of these areas, but certain underpinning organisational attributes are essential to successful implementation. Whatever their style, organisations need a clear understanding of what might be expected under each criterion.

Effective leadership

An organisation benefits from being clear about (and being able to describe) how it is led and how this leadership is followed through at every level in the organisation. A well led organisation will know how the vision, values, and methods of clinical governance are being communicated effectively to all staff. Such communication gives staff a common and consistent purpose and clear expectations. Good leadership empowers teamwork, creates an open and questioning culture, and ensures that both the ethos and the day to day delivery of clinical governance remain an integral part of every clinical service.

Planning for quality

Clinical governance cannot be developed by doing what “seems right.” Health organisations need a plan to develop the quality of their clinical services. The plan should be based on an objective assessment of the needs and views of patients, assessed exposure to clinical risk, regulatory requirements, staff capabilities, unmet training needs, and a realistic appreciation of how present performance compares with that of similar services and best practice standards. It is also important to ensure that key underpinning strategies (such as information technology, education and training, and research and development) are serving the purposes of quality assurance and quality improvement. Ownership of the plans needs to be generated not just at board level but right down the organisation in individual teams.

Being truly patient centred

Health organisations must be clear how information and feedback from former and current patients is used to assess and improve the quality of services. Empowering patients with information, and increasing their contribution to planning services, can greatly influence the development of clinical governance. Contributions from patients will affect not just the responsiveness and performance of services but the process through which quality improvement initiatives are identified and prioritised (box).

Case study: family centred care for children with complex needs

Traditional management (as described by professionals from the NHS Trust)

Children were referred to each therapist individually

After referral the child and family attended clinics in various places at various times

Reports were returned, at various intervals, to the referring doctor

Reports were reviewed in isolation—without the benefit of collaboration between professionals

The child and family attended several clinics and often became confused about objectives, possibilities, work required, etc

It could take 2 years for a child to reach the end of the evaluation process, during which time need had often changed

Response

Multiprofessional collaboration has facilitated the design of a family focused, effective, speedy package of care that is planned and delivered to suit the convenience and needs of the child and his or her family. A new service is currently being piloted.

Solution

On first referral a child is visited at home by a member of the locality based team and the family's health visitor

Areas of need are identified and appropriate professionals arrange to assess the child and family at a time and place that suits the child and family

All assessments are completed within 6 weeks and a single needs assessment report is produced in conjunction with the child and family

Together, the child, family, and healthcare professionals agree the goals of healthcare intervention and formulate an action plan

Progress is reviewed regularly

All staff need to be patient centred in their work—from the doctor discussing treatment options with a patient in the consulting room, to the primary care nurse ensuring that the elderly diabetic woman can get in contact for advice if she has worries, to the hospital manager spending time in wards and clinics to see the care patients receive and listen to their comments.

Information, analysis, insight

A health organisation establishing a culture of clinical governance must develop excellence in the selection, management, and effective use of information and data to support policy decisions and processes. For information and data to be useful they must be valid, up to date, and presented in a way that provides insight. Good data and information used to highlight, for example, differences in outcome, shortfalls in standards, comparisons with other services, and time trends, are essential. This information is vital to tell staff how they are doing and show where there is room to do even better (box).

Case study: sharing information to improve quality in trauma and orthopaedics

Traditional system (as described by professionals from the trust)

No system for benchmarking performance against national outcomes

Clinical data were not shared

No forum for discussion of clinical incidents or complaints

No system to agree and implement new policy, guidelines, or protocols

After multidisciplinary review and agreement of shared objectives

Weekly team meeting of all 7 surgeons, nurses, physiotherapists, managers, and junior doctors

Care pathways and protocols have been agreed and are shared

Agreed mechanism exists for implementing national recommendations and guidelines

Mechanisms have been developed to review and deal with clinical incidents and complaints

Clinical outcome data are shared and reviewed to allow modification of practice across the service

Clinical outcome data are collected for benchmarking purposes

Ordinary people doing extraordinary things

People who work in the NHS must be able to make the best possible contribution, individually and collectively, to improving health care. The ideal of a service that enables all staff to develop and use their full potential, which is aligned with the organisation's objectives, is rarely met.

One step towards this goal is for education and training to support the organisation's implementation of clinical governance so that knowledge and skills are reinforced in the workforce. However, developing a workforce that is fit for purpose goes much wider than this. At the most basic level it means ensuring that staff feel valued, that they share in the policy discussions about developing clinical governance, and that management is seen to be trying to tackle their problems and concerns as well as seeking their ideas for improvement and innovation.

An effective workforce also needs appropriate technical support—for example, access to valid best evidence to support clinical decisions. Finally, the creation of a culture that is free of blame and encourages an open examination of error and failure is a key feature of services dedicated to quality improvement and to learning.

Good service design

It is important to step back and examine how processes in the delivery of health care can be better designed. An organisation working towards implementing clinical governance could begin to describe how new, modified, and patient specific services are designed and implemented. It could include how changing patient requirements and changing technology are incorporated into healthcare service designs; how processes for delivering healthcare services are designed to meet patient, quality, and operational requirements (including best practice requirements); and how design and delivery processes are coordinated and tested to ensure trouble free and timely introduction and delivery of services. An integral part of process management includes examining how processes to design healthcare services are evaluated and improved to achieve better performance.

Demonstrating success

The ability to measure the quality of services is essential for successful implementation of a culture that supports clinical governance. Measures of effectiveness might include waiting times and turn around times; waste reduction, such as reducing repeat tests; strategic indicators, such as innovation rates, effectiveness of innovations, and time to introducing new services.

Clinical governance development programme

The NHS Clinical Governance Support Team was established in 1999 to support the development and implementation of clinical governance.18 The team is now a part of the Modernisation Agency. Its aims are to promote the goals of clinical governance throughout the health service; to act as a focus of expertise, advice, and information; and to offer a training and development programme for clinical teams and NHS organisations.

The team runs a clinical governance development programme for multidisciplinary delegate teams drawn from organisations across the NHS. Delegate teams attend a series of five, task oriented workshops (learning days) punctuated by eight week action intervals spread over nine months. During this time delegates lead project teams in their organisations as they review, design, and deliver quality improvement initiatives. To date, 250 organisations have committed multidisciplinary teams to the five day programme.

The support team reinforces top down support for delegates by visiting health organisations and meeting their boards. The team helps boards to understand what staff have already achieved and plan support structures and dissemination strategies to spread clinical governance initiatives throughout the organisation. The visits help the board to develop an organisational culture that supports whole system, multilevel improvement initiatives and healthcare professionals who “learn as they do.”

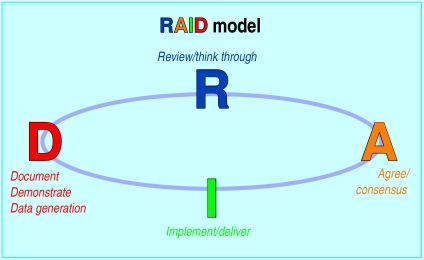

The programme follows the RAID (review, agree, implement, demonstrate) model (figure) to initiate a project culture within their organisation. The first stage is a large scale review of current service. Delegates gather staff and patient views, come to understand and define the baseline existing service, and collect evidence about current best practice. The process encourages the examination of traditionally accepted unwritten rules and beliefs.

Examples of improvement initiatives undertaken by delegate teams

Primary care group where care of women with postnatal depression was found to be “hit and miss”—Early warning signs were often missed. Women with postnatal depression, and staff supporting them, felt that there was inadequate support. All professionals have agreed to implement the Edinburgh post natal depression scale, training has been agreed and implemented, and interprofessional, evidence based assessment and management protocols have been developed

Urology: discharge summaries found to be of variable quality and value—Eight surgeons and primary care professionals have collaborated. Discharge information is now produced by computer. It is legible, accurate, and timely, with full details of investigations planned, results to date, follow up plans, etc. Because data are now shared by all surgeons, the information provides a database for audit and measuring performance

Long delays for initial referral and poor patient focus in adolescent mental health service—Multidisciplinary teams are working with healthcare professionals in primary care to produce shared referral, assessment, and management guidelines. A triage system has been developed to reduce waiting times; evening clinics have been set up so that clients no longer need to take time out of education; guidelines and standards are being reviewed and agreed across professions and organisational boundaries

Ambulance service where blame culture meant critical incidents went unreported—In the past, a paramedic who made a drug error would have been instantly demoted to technician; there would have been an investigation, a disciplinary hearing, and a warning letter placed in the personal file. “Re-offence” within 12 months would result in dismissal. Now, with development of a “no blame” culture, system flaws are identified: drug storage has been amended so that systems became supportive of staff and protective of patients

Further examples of improvements made as a result of the clinical governance development programme are available at www.cgsupport.org

The agreement phase involves flagging up the route to initiate improvement. It ensures that all healthcare alliances and partners have been involved and are contributing to defining a vision for the service. This phase is about winning “hearts and minds.”

The implementation phase capitalises on the enthusiasm previously generated. Healthcare professionals are keen to measure, to know, and to prove that they are making an important difference for patients. They move naturally into the demonstration phase, where improvement activities are reflected in hard data that is then used to inform future development.

Each team of delegates works with a support team programme manager, who makes regular site visits. Delegates are helped to identify existing resources within their organisation and to secure more if necessary. Training, research, and educational materials are made available, and delegates have telephone and electronic access to the team and programme managers for advice and support. The box gives some examples of improvement initiatives that have been introduced by delegates. Further details of the programme are available on the BMJ 's website.

Conclusions

The first investigations into failing services carried out by the Commission for Health Improvement showed organisations that were poorly led.19,20 There were cliques and factions among groups of staff, management was ineffective, staff with concerns about standards of care were marginalised or worse, adequate systems were not in place, and the service was not seen through the patients' eyes. The fact that these dysfunctional organisations were associated with such poor quality care will not surprise anyone who has read the succession of inquiry reports into NHS failings over the past 10 years.

The NHS has been late in realising that healthy organisations matter to patients. The challenge of clinical governance is to transform the culture and service delivery of NHS organisations throughout the United Kingdom. This revolution has begun.

Supplementary Material

Figure.

RAID model developed by National Clinical Governance Support Team

Acknowledgments

We thank Laurence Wood, Ron Cullen, Eileen Smith, and Susanna Nicholls.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Nine declared.

Further details of the clinical governance development programme are available on the BMJ's website

References

- 1.Department of Health. The new NHS. London: Stationery Office; 1997. (Cm 3807). [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Health Service and Community Care Act 1990. London: HMSO; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scally G, Donaldson LJ. Clinical governance and the drive for quality improvement in the new NHS in England. BMJ. 1998;317:61–65. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7150.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Secretary of State for Health. The NHS plan. London: Stationery Office; 2000. (CM 4818-I). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomson RG, Donaldson LJ. Medical audit and the wider quality debate. J Pub Health Med. 1990;12:149–151. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubmed.a042539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deming WE. Out of the crisis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Juran JM. Managerial breakthrough. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gray JD, Donaldson LJ. Improving the quality of healthcare through contracting: a study of health authority practice. Qual Healthcare. 1996;5:201–205. doi: 10.1136/qshc.5.4.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evidence-based Medicine Working Group. Evidence-based medicine: a new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. JAMA. 1992;268:2420–2425. doi: 10.1001/jama.1992.03490170092032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malcolm AJ. Enquiry into the bone tumour service based at the Royal Orthopaedic Hospital. Birmingham: Birmingham Health Authority; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dyer C. Obstetrician accused of committing a series of surgical blunders. BMJ. 1998;317:767. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith R. Regulation of doctors and the Bristol inquiry. BMJ. 1998;317:1539–1540. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7172.1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kotter JP. Leading change: why transformation efforts fail. Harvard Business Review 1995 Mar/Apr 1995:59.

- 14.Department of Health. National service framework for mental health. London: DoH; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Department of Health. Supporting doctors, protecting patients. London: DoH; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Department of Health. An organisation with a memory: report of an expert group on learning from adverse events in the NHS. London: Stationery Office; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 17.General Medical Council. Revalidating doctors. London: GMC; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halligan A. How the national clinical governance support team plans to support the development of clinical governance in the workplace. J Clin Governance. 1999;7:155–157. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Commission for Health Improvement. Investigation into Carmarthenshire NHS Trust: report to the assembly minister for health and social services for the National Assembly for Wales. London: Commission for Health Improvement; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Commission for Health Improvement. Investigation into the North Lakeland NHS Trust: report to the secretary of state for health. London: Commission for Health Improvement; 2000. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.