Abstract

Using a recently developed model for in vitro generation of pp65-positive polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNLs), we demonstrated that PMNLs from immunocompetent subjects may harbor both infectious human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) and viral products (pp65, p72, DNA, and immediate-early [IE] and pp67 late mRNAs) as early as 60 min after coculture with human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) or human embryonic lung fibroblasts (HELF) infected with a clinical HCMV isolate (VR6110) or other wild-type strains. The number of PMNLs positive for each viral parameter increased with coculture time. Using HELF infected with laboratory-adapted HCMV strains, only very small amounts of viral DNA and IE and late mRNAs were detected in PMNLs. A cellular mRNA, the vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 mRNA, which is abundantly present in both infected and uninfected HUVEC, was detected in much larger amounts in PMNLs cocultured with VR6110-infected cells than in controls. Coculture of PMNLs with VR6110-infected permissive cells in the presence or absence of RNA, protein, and viral DNA synthesis inhibitors showed that only IE genes were transcribed in PMNLs during coculture. Synthesis of IE transcripts in PMNLs was also supported by the finding that only the copy number of IE mRNA (and not the DNA or the pp67 mRNA) per infected PMNL increased markedly with time, and the pp67 to IE mRNA copy number ratio changed from greater than 10 in infected HUVEC to less than 1 in cocultured PMNLs. Fluorescent probe transfer experiments and electron microscopy studies indicated that transfer of infectious virus and viral products from infected cells to PMNLs is likely to be mediated by microfusion events induced by wild-type strains only. In addition, HCMV pp65 and p72 were both shown to localize in the nucleus of the same PMNLs by double immunostaining. Two different mechanisms may explain the virus presence in PMNLs: (i) one major mechanism consists of transitory microfusion events (induced by wild-type strains only) of HUVEC or HELF and PMNLs with transfer of viable virus and biologically active viral material to PMNLs; and (ii) one minor mechanism, i.e., endocytosis, occurs with both wild-type and laboratory strains and leads to the acquisition of very small amounts of viral nucleic acids. In conclusion, HCMV replicates abortively in PMNLs, and wild-type strains and their products (as well as cellular metabolites and fluorescent dyes) are transferred to PMNLs, thus providing evidence for a potential mechanism of HCMV dissemination in vivo.

Diagnosis of disseminated human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) infection in the immunocompromised host is based on virus detection and quantitation in blood, namely in peripheral blood polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNLs). Major diagnostic assays using ex vivo PMNL preparations are HCMV viremia, i.e., recovery of infectious virus from PMNLs (15); antigenemia, i.e., detection of HCMV pp65 in the nucleus of PMNLs (11, 14, 28, 34); leukoDNAemia, i.e., detection of viral DNA in PMNLs (13); and leukoRNAemia, i.e., detection of viral mRNAs, either immediate early (IE) (26, 35), late (1, 2, 12, 16, 17, 22, 25), or both (23, 24), in PMNLs. In addition, the development of diagnostic assays showing the presence of late mRNAs in PMNLs, besides that of IE mRNAs (10, 18) and infectious virus (12, 15), has strengthened the assumption that HCMV could productively replicate in PMNLs (3, 36). However, whether PMNLs are fully permissive for active HCMV replication or may support only a partial (abortive) virus replication or are passive carriers of virus or viral material disseminating the infection into multiple body sites remains to be determined. In addition, the mechanism underlying the dissemination by PMNLs is obscure, since PMNLs should degrade viral material uptaken by endocytosis.

In the present study, using a recently developed in vitro model for generation of pp65-positive PMNLs (27), we showed that virus and viral (as well as cellular) material detected in PMNLs are transferred from permissive infected cells (either endothelial or human fibroblasts) to PMNLs from immunocompetent individuals, while only abortive virus replication occurs in PMNLs. The phenomenon is mediated by microfusion events of infected cells and PMNLs, which occur only when infection is sustained by wild-type and not laboratory-adapted strains of HCMV. This mechanism has also been investigated by fusion assays using fluorescent probes and by electron microscopy (EM). Endocytosis, occurring with both wild-type and adapted strains, appears to play a minor role.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell cultures and virus strains.

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were obtained by trypsin treatment of umbilical cord veins and were used at passages three to six, as previously reported (27). Human embryonic lung fibroblasts (HELF) were derived from a cell strain originally developed in our laboratory and used at passages 20 to 30. HCMV strains AD169, Towne, and Davis (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, Md.) were routinely propagated in HELF cultures. A clinical strain (VR6110) isolated from the blood of an AIDS patient was adapted to growth on HUVEC, while it was propagated in parallel in HELF, as reported (27). In addition, 50 clinical isolates recovered from multiple body sites of both immunocompetent and immunocompromised individuals were propagated in HELF and tested for pp65 antigen in PMNLs following coculture.

Coculture of PMNLs and HCMV-infected cell cultures.

Concentrated PMNL preparations (degree of purity, >95%) were obtained from blood donors as reported (11, 27) and were routinely tested by nested PCR (13) and found to be negative for viral DNA. Then, PMNLs were cocultured with HUVEC or HELF infected with either wild-type or laboratory-adapted HCMV strains. In parallel, PMNL preparations were cocultured with uninfected HUVEC. PMNLs were used either on the day of collection or following overnight maintenance on uninfected HUVEC monolayers. Unless otherwise indicated, HCMV-infected cell cultures were used for coculture 96 h postinfection (p.i.). Coculture time ranged from 1 to 24 h. Following coculture, to separate PMNLs from infected HUVEC or HELF, cell mixtures were placed in the upper compartment of a cell culture insert of 6.5-mm diameter and 5-μm pore size (Transwell; Costar, Cambrige, Mass.) for 3 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere, while the bottom compartment contained 10−8 M formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.), as previously reported (11, 27).

FACS purification.

Migrated PMNLs were tested by different viral assays before and after fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) purification following PMNL staining with CD66b (Immunotech, Instrumentation Laboratory, Milan, Italy). Cell sorting was performed with a FACStar PLUS apparatus (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, Calif.). Laser output was 240 mW at 488 nm. Sorting was carried out according to standard FACStar specifications with a 3-drop deflection criterion using a 70-μm-diameter nozzle. In addition, some PMNL preparations were treated with 0.25% trypsin (GIBCO BRL, Paisley, Scotland) solution at 37°C for 10 min prior to and after cell sorting.

Interference of endocytosis with results of viral assays.

The following sets of experiments were carried out as follows: PMNLs were incubated for 3 h with Towne- or VR6110-infected HELF medium and PMNLs were cocultured for 3 h with Towne- or VR6110-infected HELF. These conditions allowed the determination of the amount of viral material taken up by endocytosis compared to the overall viral load of PMNLs following coculture with either wild-type or laboratory HCMV strain-infected HELF.

PMNL coculture and migration in the presence of mRNA, protein, and viral DNA synthesis inhibitors.

In experiments designed to investigate HCMV replication in PMNLs, these cells were cocultured for 3 h with VR6110-infected HUVEC in the presence of 10 μg of actinomycin D (Sigma) per ml, 100 μg of cycloheximide (Sigma) per ml, or 400 μM phosphonoformic acid (PFA) (Sigma). Inhibitors were maintained at the same concentration during the 3 h migration step.

HCMV load in VR6110-infected HUVEC and in cocultured PMNLs.

The copy number of viral DNA, IE mRNA, and pp67 mRNA per infected cell was determined in HUVEC at 96 h p.i. To determine the number of PMNLs positive for DNA or mRNAs, serial PMNL mixtures containing a progressively decreasing number of cocultured PMNLs in a progressively increasing number of PMNLs from healthy donors were prepared and then tested in 105 aliquots. In parallel, aliquots of 105 cocultured and unmixed PMNLs were tested by different assays for the total amount of viral nucleic acids. Then, the copy number of viral DNA, IE mRNA, and pp67 mRNA per infected PMNL was calculated by dividing the total copy number for each viral nucleic acid per 105 PMNLs by the number of PMNLs positive for each parameter. In addition, the number of p72- and pp65-positive PMNLs and the number of PMNLs carrying infectious virus was determined according to well-standardized procedures (see below).

Viral assays.

The number of pp65- and p72-positive PMNLs was determined on 105 PMNL cytospin preparations that were fixed and stained according to a previously reported procedure (11, 14). Quantification of infectious virus carried by PMNLs following coculture was performed by inoculating 105 PMNLs onto HELF monolayers grown in shell vials and by counting the number of HCMV p72-positive nuclei, which were stained 16 to 24 h p.i. by using a monoclonal antibody to the HCMV major IE protein p72 (15). HCMV DNA was quantified in 105 PMNL aliquots according to a reported quantitative PCR method by using a primer pair relevant to exon 4 of the IE-1 gene (13). In a set of experiments, viral DNA was quantified in parallel in cocultured PMNLs and in isolated PMNL nuclei from the same cocultured preparations.

Nucleic-acid-sequence-based amplification (NASBA) for pp67 mRNA determination (Nuclisens CMV pp67; Organon Teknika, Boxtel, The Netherlands) was carried out following manufacturer's instructions. IE mRNA was similarly determined by NASBA by using a qualitative experimental assay developed by the same manufacturer. Details of test performance have been recently reported for NASBA pp67 mRNA determination (2, 12). Briefly, 106 PMNLs were added to 1.0 ml of NASBA lysis buffer, and the mixture was stored at −80°C. A standard amount of system control RNA, which served as an internal positive control for the isolation, amplification, and detection of RNA during the NASBA procedure, was added prior to nucleic acid isolation. The nucleic acids were then eluted in 50 μl of 1.0 mM Tris (pH 8.5) and were examined (5 μl/test, corresponding to 105 PMNL) or stored at −80°C. The NASBA reaction was performed with a pair of primers designed to amplify a fragment of the mRNA encoding HCMV pp67 (the UL65 late gene product) or a region of the IE-1 transcript encoding HCMV p72. Following hybridization of the amplification products with a specific capture and a specific ruthenium-labeled detection probe, final reading of test results was achieved by using an electrochemiluminescence instrument (NASBA QR System; Organon Teknika). Semiquantification of IE and pp67 mRNA was achieved by serial dilution of RNA extracts, taking into account that the sensitivity of NASBA assay was 70 copies of input RNA of either IE or pp67 mRNA (J. Middeldorp, Organon Teknika, personal communication). A preliminary comparison of semiquantitative NASBA results and quantitative determinations performed using a quantitative NASBA assay now under evaluation showed that results obtained by the two methods were within 50% variations of the mean (data not shown).

Detection of VCAM-1 mRNA in HUVEC and PMNLs by RT-PCR.

A new reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) technique for detection of the two spliced forms of vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1) mRNA (7, 20) was developed. In detail, total RNA was extracted from 6 × 106 aliquots of infected and uninfected HUVEC as well as from 3 × 106 PMNLs cocultured with infected and uninfected HUVEC by using the RNAzol B kit (Tel-Test, Inc., Friendswood, Tex.) according to manufacturer's instructions. Then, a region spanning domains 3, 4, and 5 of the VCAM-1 longer transcript as well as a region spanning domains 3 and 5 of the VCAM-1 shorter transcript were retrotranscribed by using the antisense primer R6 (5′ AGC TTA CAG TGA CAG AGC TC 3′, nucleotides [nt] 2275 to 2256) and were subsequently amplified by PCR by using primers F3 (5′ TCA CCT TAA TTG CTA TGA GG 3′, nt 1685 to 1704) and R6. Reverse transcriptase (RT) reaction was performed in a 20-μl total volume (15 pmol of R6 primer, 12 nmol of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 1× PCR buffer, 200 U of Moloney murine leukemia virus RT) for 30 min at 37°C, using 106 and 105 aliquots of HUVEC and PMNL, respectively. PCR was performed for 55 cycles (30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 55°C, and 45 s at 72°C) by adding 30 μl of PCR mixture (1× PCR buffer, 25 pmol of F3 primer, 10 pmol of R6 primer, 2.5 U of Taq polymerase) to RT products. Finally, PCR products were submitted to 20 additional cycles of amplification using nested primers (F5, 5′ GGA ATT TAT GTG TGT GAA GGA G 3′, nt 1717 to 1738; R4, 5′ ATC TCG ATT TCT GGA TCT C 3′, nt 2233 to 2215). Predicted sizes of nested RT-PCR products were 377 bp for the VCAM-1 longer transcript and 99 bp for the shorter mRNA.

Blocking of HCMV transmission from PMNLs to uninfected HELF.

PMNL preparations cocultured with infected cell cultures were further cultured, following migration, onto cell culture inserts of a 0.4-μm-pore-size membrane (Becton Dickinson), thus preventing the contact of PMNLs with the underlying uninfected HELF cell monolayer. In addition, prior to inoculation onto HELF cell cultures, in vitro-generated HCMV-positive PMNLs were incubated overnight with uninfected HELF in the presence or absence of either 6.9 μg of anti-CD18 (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) per ml or 15.2 μg of anti-ICAM-1 (DAKO) monoclonal antibody per ml, or both. In parallel control experiments, monoclonal antibodies anti-E-selectin, anti-ICAM-3, and anti-PECAM-1 (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, Minn.) were tested at their optimal concentrations.

Fusion assays.

To demonstrate fusion of VR6110-infected HUVEC or HELF and PMNLs during coculture, two vital fluorescent dyes were used: 5-chloromethylfluorescein diacetate (CMFDA) (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.) and 5- and 6-([4-chloromethylbenzoyl)amino]tetramethylrhodamine (CMTMR, Molecular Probes). Each dye was used as a 5 mM stock solution in dimethylsulfoxide (Sigma). VR6110-infected and uninfected HUVEC (or HELF) were stained with 10 μM CMFDA (Cell Tracker Green), whereas PMNLs were stained with 1 μM CMTMR (Cell Tracker Orange) according to a reported procedure (21). Microscopic observation of PMNLs and their dual fluorescing fusion products was achieved by using a fluorescent microscope (model DM RBE; Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) with filter G/R 513803 (Leitz) designed for simultaneous excitation by 490 ± 20 and 575 ± 30 nm fluorescent light.

HCMV pp65 and p72 nuclear localization assays.

Initially, the nuclear localization of HCMV pp65 and p72 was investigated by double immunological staining of the same PMNL cytospin preparations, which was performed as follows. First, following fixation with paraformaldehyde and permeabilization (14), cells were stained with a p72-specific monoclonal antibody (15) and an anti-mouse immunoglobulin G fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled conjugate (Cappel, Organon Teknika, West Chester, Pa.). Then the same cell preparations were restained with guinea pig HCMV antiserum prepared in the laboratory and previously shown to stain pp65 in PMNL nuclei, followed by a secondary anti-guinea pig conjugate labeled with either FITC or horseradish peroxidase (Cappel). Double staining with two FITC-labeled conjugates was discriminating due to the markedly different pattern of distribution of the two HCMV proteins inside PMNL nuclei. Subsequently, PMNL preparations were double stained for immunofluorescence laser confocal microscopy by simultaneous incubation with the same two primary antibodies from mouse and guinea pig for 30 min and secondary anti-species antibodies labeled with FITC or rhodamine (Cappel), respectively, for an additional 30 min. The samples were examined with a PCM 2000 Confocal Microscope System (Nikon, Melville, N.Y.) equipped with a Nikon Diaphot 300 inverted microscope and a 40X (1.3 numerical aperture) Nikon oil fluorescence objective. The 488-nm Argon laser line and the green He-Ne laser line were directed to the sample with a single-mode fiber optic cable via high-precision laser coupler. Pinhole size was set at 20 μm. Fluorescence emission light was passed back through a first dichroic mirror and was divided by a second dichroic mirror into light greater or less than 565 nm. Green emission fluorescence of FITC continued through a BA 515- to 530-nm-spectrum filter on CH1, and red emission fluorescence of rhodamine was passed through a BA 590- to 660-nm-spectrum filter on CH2. The image size was set at 512 by 512 or 1,024 by 1,024 pixels.

EM study.

In vitro-generated HCMV-positive PMNLs and HCMV-infected HUVEC or HELF were fixed with a mixture of two parts of 1% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer and one part of 2.5% glutaraldehyde in the same buffer. Fixed samples were resuspended in saline solution and then were placed in 0.25% uranyl acetate for 30 min, dehydrated, and embedded in Epon 812. Ultrathin sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and were finally examined with a Philips CM12 STEM electron microscope (Philips, Eindhoven, The Netherlands).

RESULTS

Kinetics of infectious virus and viral products in cocultured PMNLs.

The kinetics of infectious virus and viral products in PMNLs was investigated following 1-, 3-, and 24-h coculture times with VR6110-infected HUVEC. Results reported in Table 1 indicate that not only pp65, p72, and IE mRNA, but also viral DNA, pp67 mRNA, and infectious virus are detected in PMNLs after as little as 1 h of coculture with VR6110-infected HUVEC at 96 h p.i. Thus, the presence in PMNLs of late pp67 mRNA and infectious virus, at very early coculture times, indicates uptake or transfer of viral material from permissive infected HUVEC to PMNLs. Levels of viral DNA, pp65, and p72 as well as viral mRNAs increased after 3 and 24 h of coculture, whereas the levels of infectious virus decreased (Table 1). Following 3 h of coculture, levels of viral DNA were distributed in comparable amounts between nucleus and cytoplasm (data not shown). Examples of pp65 detection in PMNLs freshly collected or maintained in vitro overnight prior to 3 h of coculture with infected HUVEC are given in Fig. 1A and B, respectively, while examples of detection of p72 in PMNL nuclei following overnight in vitro maintenance and 3 h of coculture with infected HUVEC are shown below (see Fig. 5A and B).

TABLE 1.

HCMV load in PMNLs after different coculture times with VR6110-infected HUVEC and Towne-infected HELF at 96 h p.i.

| Viral parameter | HCMV loada median values (range) in PMNLs after coculture with

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VR 6110 (h)

|

Towne (24 h)b | |||

| 1 | 3 | 24 | ||

| pp65 antigen | 375 (250–550) | 1,100 (1,000–7,000) | 5,000 (3,000–15,000) | 0 |

| p72 antigen | 150 (110–220) | 500 (300–600) | 2,500 (2,000–3,000) | 0 |

| Infectious virus | 5 (2–33) | 60 (15–200) | 17.5 (11–100) | 0 |

| DNA | 71 (62–250) | 365 (100–1,000) | 400 (100–1,000) | 4 (1–10) |

| IE mRNA | +++c | +++/++++ | ++++ | + |

| pp67 mRNA | ++ | ++/+++ | +++ | +/− |

Quantification units indicate the following: number of HCMV pp65- or p72-positive per 105 PMNLs examined, for pp65 and p72 antigen, respectively; numbers of HCMV p72-positive HELF nuclei (i.e., number of PMNLs carrying infectious virus) per 105 PMNLs inoculated onto a shell vial monolayer, for infectious virus; number of HCMV genome equivalents (10−3) of HCMV DNA per 105 PMNLs (0.5 μg of DNA) examined, for DNA. Number of experiments ranged from 5 to 10 for each value.

Similar results were obtained with AD169 and Davis strains.

+, positive; number of + signs indicates a semiquantitative evaluation of viral mRNAs based on endpoint dilutions of extracts from aliquots of 105 PMNLs; +/−, indicates occasional positive values close to the cutoff of the assay.

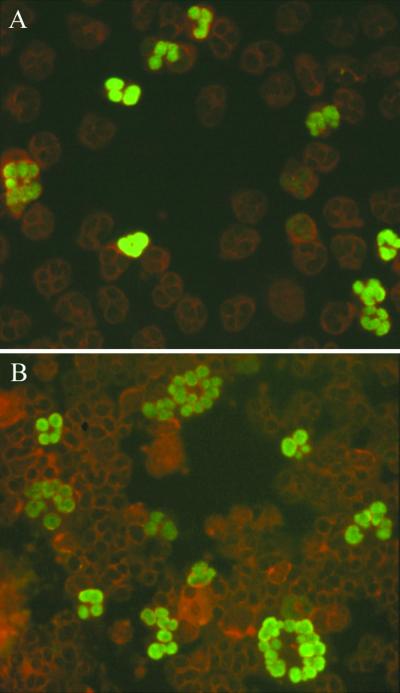

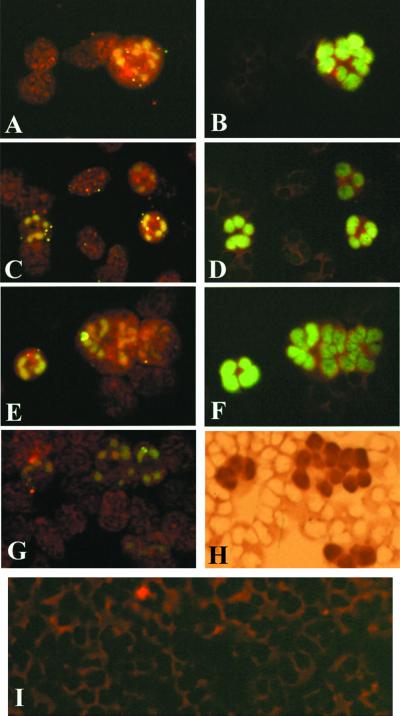

FIG. 1.

In vitro-generated pp65-positive PMNLs. (A) freshly collected and cocultured for 3 h with HUVEC infected with VR6110 at 96 h p.i. and (B) cocultured for 3 h with infected HUVEC at 96 h p.i., following overnight in vitro maintenance on HUVEC. (A) Single pp65-positive PMNLs; (B) giant pp65-positive PMNLs.

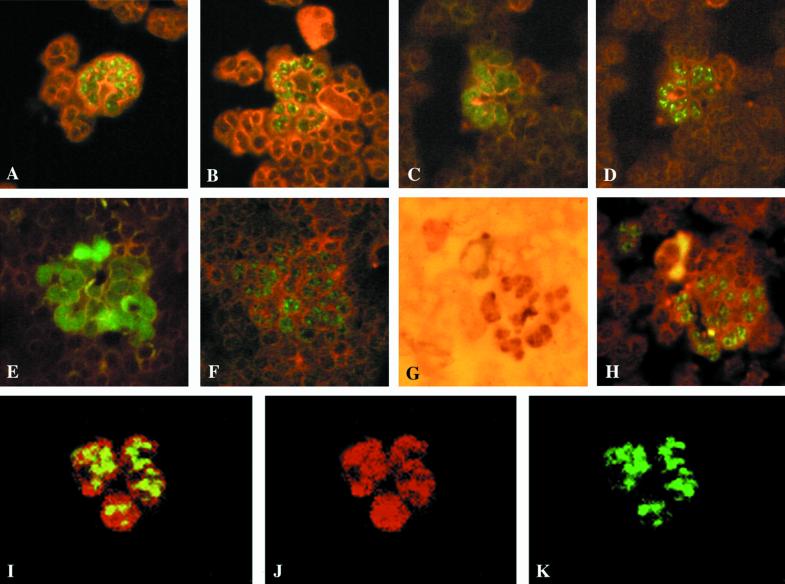

FIG. 5.

Detection of p72 and nuclear localization of p72 and pp65 in PMNL nuclei. (A and B) Morphological patterns of p72 in PMNL nuclei following overnight in vitro maintenance on HUVEC and 3 h coculture with VR6110-infected HUVEC. Two examples of nuclear localization of pp65 (C and E) and p72 (D and F) using sequential double immunofluorescent staining (different fluorescent patterns), sequential double immunostaining of pp65 (G) by immunoperoxidase and p72 (H) by immunofluorescence, and simultaneous detection (I) of pp65 (J, rhodamine-labeled) and p72 (K, FITC-labeled) in a PMNL nucleus by confocal microscopy are shown.

Comparable results for pp65 antigen and infectious virus in PMNLs were consistently obtained following coculture with HELF infected with as many as 50 clinical HCMV isolates, whereas pp65 antigen and recovery of infectious virus were consistently negative following coculture of PMNLs with HELF infected with laboratory-adapted HCMV strains (Towne, AD169, and Davis) and levels of viral nucleic acids were very low (Table 1).

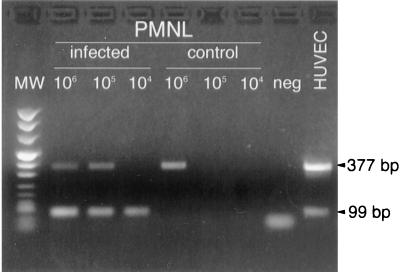

Detection of VCAM-1 mRNA in HUVEC and PMNLs by RT-PCR.

In both infected and uninfected HUVEC, longer and shorter VCAM-1 mRNAs appeared to be expressed, with the longer form expressed at a higher proportion. However, while both longer and shorter VCAM-1 mRNAs were detected in aliquots of 106 and 105 PMNLs cocultured for 24 h with infected HUVEC and the shorter form of mRNA only in aliquots of 104 PMNLs, the longer transcript could be detected only in aliquots of 106 PMNLs cocultured with uninfected HUVEC, whereas the aliquots of 105 and 104 PMNLs were negative for both forms of VCAM-1 transcripts (Fig. 2). Thus, the shorter form was detected only in PMNLs cocultured with infected HUVEC.

FIG. 2.

Detection of VCAM-1 mRNAs in PMNLs and endothelial cells by RT-PCR. The longer form (377-bp band) is detected in aliquots of 106 and 105 PMNLs cocultured for 24 h with infected HUVEC but is absent in aliquots of 104 and 105 PMNLs cocultured with uninfected HUVEC (control). The shorter form (99-bp band) is detected only in aliquots of 106, 105, and 104 PMNLs cocultured with infected HUVEC but is absent in aliquots of PMNLs cocultured with uninfected HUVEC.

Virus and viral products detected in cocultured PMNLs are not due to contaminating infected HUVEC or cell debris.

To verify whether virus and viral products carried by cocultured PMNLs could be due to contaminating HCMV-infected HUVEC or HUVEC debris, preparations of PMNLs cocultured for 1 and 24 h were submitted to FACS analysis after Transwell migration. In parallel, preparations of migrated PMNLs obtained prior to and after FACS purification were treated with trypsin. Results reported in Table 2 indicate that pp65 antigen and infectious virus, as well as DNA, IE mRNA, and pp67 mRNA levels did not change after trypsin treatment of 1-h-cocultured PMNLs or after cell sorting. Substantially overlapping results were obtained by using the same procedure on 24-h-cocultured PMNL preparations (data not shown), thus confirming previously reported findings (27).

TABLE 2.

Effect of FACS purification and trypsin treatment on HCMV load of PMNLs cocultured for 1 h with VR6110-infected HUVEC at 96 h p.i.

| Treatment | HCMV load in PMNLs

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presorting

|

Postsorting

|

|||||||||

| pp65 antigen | Infectious virus | DNAa | IE mRNAa | pp67 mRNAa | pp65 antigen | Infectious virus | DNAa | IE mRNAa | pp67 mRNAa | |

| Trypsin | 600 | 4 | 165 | 10 | 1 | 200 | 2 | 199 | 10 | 1 |

| None | 400 | 1 | 151 | 3 | 0.3 | 280 | 2 | 165 | 3 | 0.3 |

Copy number (10−3) per 105 PMNLs. IE mRNA and pp67 mRNA were semiquantified by the dilution method by using the NASBA procedure (Organon Teknika) with an approximate sensitivity of 70 copies per 105 PMNLs. Comparative assays performed using the semiquantitative method and a quantitative assay now being developed showed overlapping results within 50% variations of the mean.

Contribution of endocytosis to HCMV load of cocultured PMNLs.

As reported in Table 3, following incubation of PMNL preparations for 3 h with either Towne or VR6110 cell-free virus suspensions or coculture with Towne-infected HELF at 144 h p.i., pp65 and p72 antigen as well as infectious virus were never detected, whereas DNA as well as IE and pp67 mRNAs were weakly positive in PMNLs as compared to coculture with VR6110-infected HELF at 144 h p.i. Based on these results, it was concluded that a minor part of viral material carried by PMNLs after cocultivation might be represented by nucleic acids uptaken by endocytosis.

TABLE 3.

HCMV load of PMNLs incubated for 3 h with Towne or VR6110 cell-free virus suspensions and with Towne- or VR6110-infected HELF: role of endocytosis

| PMNLs coincubated with | HCMV load in PMNLsa

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pp65 antigen | Infectious virus | DNAb | IE mRNAb | pp67 mRNAb | |

| Towne cell-free virus suspension | 0 | 0 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 0.4 |

| VR6110 cell-free virus suspension | 0 | 0 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 0.3 |

| 144-h Towne-infected HELF | 0 | 0 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.1 |

| 144-h VR6110-infected HELF | 1,400 | 49 | 265 | 68 | 21 |

Results of three representative experiments.

Copy number (10−3) per 105 PMNLs.

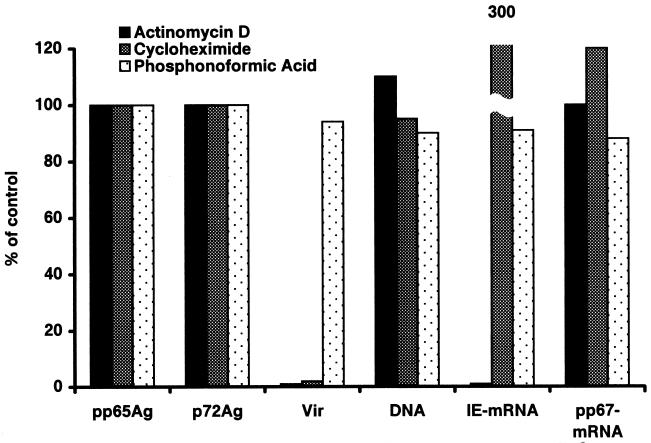

Effect of inhibitors on viral load of PMNLs.

When PMNLs were both cocultured for 3 h with VR6110-infected HUVEC at 96 h p.i. and migrated in the presence of actinomycin D, IE mRNA was reduced by 99% in PMNLs, whereas the levels of pp67 mRNA did not change significantly as well as the other virologic parameters (Fig. 3), indicating that IE mRNA synthesis apparently occurs in PMNLs during coculture. On the other hand, levels of pp65 and p72 antigens, DNA, IE mRNA, and pp67 mRNA in the presence or absence of cycloheximide and PFA were comparable within a 3-h coculture time, except for an increase in IE mRNA in the presence of cycloheximide with respect to controls. Infectious virus was not recovered from PMNLs in the presence of actinomycin D and was drastically reduced in titer or was absent in the presence of cycloheximide, whereas it was not affected by PFA. Apparently, this effect was not due to carryover of the inhibitor as shown by comparable recovery of infectious virus from cocultured PMNL preparations either mixed or not mixed with actinomycin D-treated PMNLs. Virus recovery was also abolished if cocultured PMNLs were treated with actinomycin D for 1 h either prior to or after coculture, whereas it was not affected by cycloheximide in the same experimental conditions (data not shown). Only reduction of actinomycin D concentration from 10 to 1 μg/ml and reduction of treatment duration (30 min) allowed reversion of the inhibitory effect on infectious virus recovery.

FIG. 3.

HCMV load in PMNLs cocultured for 3 h with VR6110-infected HUVEC at 96 h p.i. in the presence of actinomycin D, cycloheximide, and phosphonoformic acid. Results are expressed as percent values in the presence of inhibitors with respect to control values obtained in the absence of inhibitors. pp65Ag, pp65 antigen; p72Ag, p72 antigen; Vir, infectious virus.

HCMV load in VR6110-infected HUVEC and in PMNLs after coculture with infected HUVEC.

The approximate copy numbers of viral DNA and pp67 mRNA per infected cell were in the same order of magnitude in infected HUVEC at 96 h p.i., whereas that of IE mRNA was more than 10 times lower. The number of PMNLs positive for each of the six viral parameters determined, as well as the approximate copy number of viral DNA and mRNA per infected PMNL was calculated prior to (data not reported) and after FACS purification following 1 and 3 h of coculture (Table 4). After sorting, it was found that the ratio of positive to negative (P/N) PMNLs for viral DNA was 1/31.6 cells after 1 h and 1/7.1 cells after 3 h of coculture, respectively, while at the same times the P/N ratios for pp65 antigen were 1/242 and 1/19.6, and for IE mRNA 1/151 and 1/32.3, respectively, while the lowest P/N ratios were obtained for infectious virus (1/5,000 and 1/625) and pp67 mRNA (1/16,666 and 1/3,125, respectively). In addition, the P/N ratio for p72 antigen was 1/497 after 1 h and 1/43 after 3 h of coculture. Results obtained prior to cell sorting were fully comparable to those obtained after cell sorting. In particular, (i) the number of PMNLs positive for each parameter consistently increased between 1- and 3-h coculture times; (ii) levels of nucleic acids in infected cells were about 3 log10 lower in PMNLs than in infected HUVEC for DNA and pp67 mRNA, whereas they were only 1 log10 lower for IE mRNA; (iii) the pp67 to IE mRNA copy number ratio, which was 15.2 in infected HUVEC for both copy number per infected cell and total RNA amount per 105 cells, reached levels of 0.3 and 0.003 in 3-h-cocultured PMNLs, respectively; (iv) the maximal increase in copy number per infected PMNL between 1- and 3-h coculture times was relevant to IE mRNA. Comparable P/N results were obtained in an AIDS patient with disseminated HCMV infection (data not shown).

TABLE 4.

HCMV load in VR6110-infected HUVEC at 96 h p.i. and in PMNLs following 1 and 3 h of coculture and cell sorting

| Sample | HCMV loada

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antigen

|

Infectious virus | DNA | IE mRNA | pp67 mRNA | ||

| pp65 | p72 | |||||

| VR6110-infected HUVEC (no. copies/infected cell) | NAb | NA | NA | 89,000 | 2,300 | 35,000 |

| PMNLs after 1 h of coculture | ||||||

| No. positive/105 PMNLs | 412 (1/242) | 201 (1/497) | 20 (1/5,000) | 3,160 (1/31.6) | 660 (1/151) | 6 (1/16,666) |

| No. copies/infected PMNL | NA | NA | NA | 42 | 17 | 17.5 |

| PMNLs after 3 h of coculture | ||||||

| No. positive/105 PMNLs | 5,100 (1/19.6) | 2,300 (1/43) | 160 (1/625) | 14,000 (1/7.1) | 3,100 (1/32.3) | 32 (1/3,125) |

| No. copies/infected PMNL | NA | NA | NA | 30.9 | 160.0 | 54.8 |

For each parameter the ratio of positive to negative PMNLs is reported in parentheses.

NA, not applicable.

Blocking of HCMV transmission from PMNLs to uninfected HELF.

As previously shown for transfer of viral products from HCMV-infected permissive cells to PMNLs (25), transmission of virus from in vitro-generated HCMV-positive PMNLs to uninfected HELF was similarly prevented or markedly reduced by either lack of contact between the two cell populations or by incubation during coculture with either anti-CD18 (72% reduction of infectious virus) or anti-ICAM-1 (86% reduction) or both monoclonal antibodies (90 to 100% reduction). Anti-E-selectin, anti-ICAM-3, and anti-PECAM-1 monoclonal antibodies only reduced the level of infectious virus transmitted to PMNLs by 10 to 20%.

Fusion assays.

Labeling of VR6110-infected HUVEC with a green fluorescent probe allowed tracing of PMNLs transiently fusing with infected HUVEC. In addition, the rapid transfer to the nucleus of fused PMNLs of the green fluorescent probe according to a pattern resembling the pp65 antigen staining pattern suggested that the fluorescent probe could be bound to pp65 (or some other protein with nuclear targeting). Small dots of the green fluorescent probe were also infrequently observed in the cytoplasm of PMNLs cocultured with infected HUVEC. No fluorescent probe was observed in PMNLs cocultured with uninfected HUVEC. A preliminary indication that pp65 could somehow mediate migration of the fluorescent probe to the nucleus was supported by the finding that in parallel experiments a comparable number of pp65-positive PMNLs and PMNLs with fluorescent probe-labeled nuclei was observed. In this respect, conclusive evidence that the same PMNL nuclei were both chemically and immunologically labeled was provided by the sequential staining of the same PMNLs with the fluorescent probe and the pp65-specific monoclonal antibody pool, using either the immunofluorescence or the immunoperoxidase technique (Fig. 4A to I).

FIG. 4.

Nuclear localization of the green fluorescent probe and HCMV pp65 in the nuclei of PMNLs stained with the orange fluorescent probe following coculture with VR6110-infected HUVEC stained with the green fluorescent probe. The same PMNL nuclei stained by the green fluorescent probe in panels A, C, E, and G are stained immunologically (using a pp65-specific monoclonal antibody pool) by immunofluorescence in panels B, D, and F and by immunoperoxidase in panel H. (I) PMNLs stained with the orange fluorescent probe following coculture with uninfected HUVEC stained with the green fluorescent probe.

Nuclear localization studies.

By using a polyclonal guinea pig antiserum to HCMV able to stain pp65 and a mouse monoclonal antibody to p72, we were able to show the nuclear localization in the same PMNLs of the two HCMV proteins (Fig. 5C to H). Patterns of staining were very different since pp65 stained the entire nuclear area evenly (see Fig. 1 for comparison), although to a different degree, whereas p72 was present as discrete brilliant dots inside the nucleus (see Fig. 5A and B for comparison). However, p72 staining was weak or absent in PMNLs, whereas pp65 staining was strong. Thus, the number of pp65-positive PMNLs was greater than the number of p72-positive cells. Immunofluorescence laser confocal microscopy confirmed the presence of p72 and pp65 in nuclei of the same PMNLs (Fig. 5I to K).

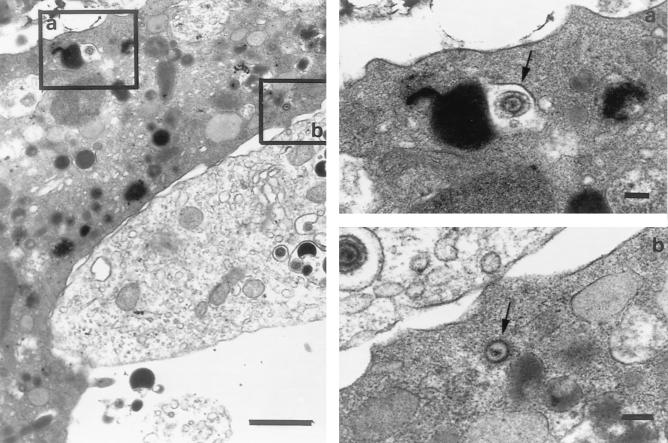

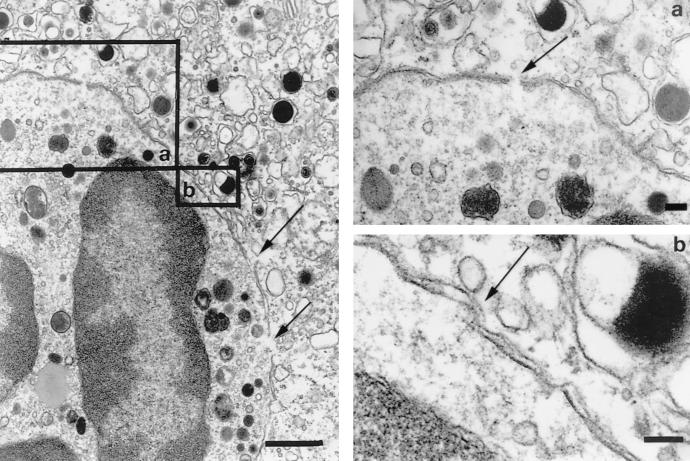

EM studies.

In order to investigate the morphological aspects of the fusion of infected HUVEC and uninfected PMNLs and the transfer of infected virus particles to PMNLs, cultures were fixed at different coculture times. Fusion events were apparently documented by discontinuation of some tracts of the membranes of two adhering cells with presence of a relatively small number of viral particles and dense bodies, often unenveloped, in the cytoplasm of PMNLs (Fig. 6 and 7). This finding was observed after 1, 3, and 24 h of coculture. In addition, virus particles and dense bodies were observed within vacuoles of endocytosis of PMNLs in a greater proportion with increasing coculture times. The relatively low number of virus particles detected by EM in a single PMNL following coculture appeared to correlate somewhat with the relatively low viral DNA copy number per PMNL.

FIG. 6.

Close contact and partial adhesion of a portion of a VR6110-infected endothelial cell (lower right) and a portion of a PMNL (upper left). The two inserts show, at a higher magnification, (a) a cytoplasmic vacuole of the PMNL containing an enveloped virus particle taken up by endocytosis (arrow) and (b) an unenveloped virus particle in the context of the PMNL cytoplasm (arrow). Bars: left, 1 μm; right (a and b), 100 nm.

FIG. 7.

Close interactions between a HCMV-infected endothelial cell (upper right) and a PMNL (lower left). Several points of discontinuation of the two adhering cell membranes are shown (see arrows). Higher resolutions of the two cell membranes are shown in the two inserts (a and b). Bars: left, 1 μm; right (a and b), 100 nm.

DISCUSSION

It is known that, unlike monocytes, PMNLs are not sites of HCMV persistence in healthy individuals (31–33). Results of the present study indicate that infectious virus and late viral products are detected in PMNLs after 1 to 3 h of cocultivation with HUVEC (or HELF) infected with a clinical HCMV strain. These findings confirm previous data (19, 27) at much earlier coculture times (1 to 3 h versus 16 to 24 h), and, together with the results provided by the semiquantitation of IE and pp67 mRNAs, unequivocally document that virions and most viral material detected in PMNLs after coculture are not the result of a complete viral replication process occurring inside PMNLs, but are the result of a direct transmission of previously assembled infectious virus and synthesized viral material to PMNLs through a cell-to-cell contact mechanism. This conclusion is supported by transfer to PMNLs of HUVEC metabolites, such as VCAM-1 mRNAs, and fluorescent probes.

Full or abortive HCMV replication in PMNLs has been claimed by different groups based upon detection of infectious virus and/or IE or late viral transcripts, which were considered markers of active virus replication inside PMNLs (1–3, 12, 16–18, 22–26, 35, 36). As an attempt to conclusively answer the question as to whether HCMV replication does occur in PMNLs or not, we used RNA and protein as well as viral DNA synthesis inhibitors during 3 h of cocultivation and 3 h of migration. Results showed that only HCMV IE gene transcription seems to occur inside PMNLs during 3 h of coculture. This conclusion is based on the following: (i) 99% reduction in IE mRNA (and not pp67 mRNA) levels in PMNLs following coculture in the presence of actinomycin D; (ii) the IE mRNA is the only mRNA in infected PMNL approaching the levels observed in infected HUVEC (only about 1 log10 reduction); (iii) the pp67 to IE mRNA copy number ratio, which is greater than 10 in HUVEC, becomes less than 1 in cocultured PMNLs; (iv) the IE mRNA is the only mRNA increasing in infected PMNL by about 1 log10 between 1 and 3 h coculture times among the three nucleic acids measured. These data are supported by the finding that viral DNA is distributed in comparable amounts between the nucleus and cytoplasm of cocultured PMNLs, thus suggesting that at least some virions entering PMNLs are uncoated and release viral DNA, which enters the nucleus, initiating IE transcription.

Thus, viral material (infectious virus, viral DNA, and late viral transcripts) detected in PMNLs at early coculture times (1 to 3 h) is acquired by transfer from infected cells. Therefore, apart from IE gene transcription, neither infectious virus nor late viral gene products detected in PMNLs represent a marker of active virus replication in these cells. The mechanism underlying the lack of recovery of infectious virus from PMNLs cocultured with infected HUVEC, following addition of actinomycin D either prior to, during, or after coculture, while occurring in the presence of PFA, remains to be clarified, but this mechanism seems to be related to a toxic effect of the inhibitor on PMNLs.

How does transfer of virus and viral material to PMNLs occur? It was previously shown that (i) lack of contact between infected HUVEC and PMNLs prevents transfer of virus and viral material to PMNLs (19, 27); (ii) blocking of adhesion by monoclonal antibodies anti-LFA-1 (CD18) and anti-ICAM-1 greatly reduced the number of pp65-positive PMNLs, i.e., transfer of viral material to PMNLs (27); and (iii) contact of PMNLs to infected cells was transitory (27). In our study, all viral products uptaken by PMNLs following incubation with infected cell culture medium were considered to be acquired by endocytosis. In these experiments, pp65 was not found in PMNL nuclei and infectious virus could not be recovered from PMNLs, thus indicating that virus uptaken by endocytosis lost infectivity and that nuclear pp65 in PMNLs did not derive from dense bodies uptaken by endocytosis. On the other hand, very small amounts of viral nucleic acids (DNA, IE mRNA, and pp67 mRNA) detected in PMNLs during endocytosis experiments were considered the results of an uptake process. From these experiments, it clearly appears that in PMNLs cocultured with HUVEC infected with clinical isolates, 100% of pp65 antigen and infectious virus and more than 90% of nucleic acids are derived from cell-to-cell transmission of virus and viral products and not from endocytosis.

The mechanism by which transfer of viral material does occur was investigated by EM and by using vital fluorescent probes. Several tracts of discontinuation of the two adhering cell membranes were observed by EM, with presence of dense bodies and of enveloped and unenveloped virus particles in the PMNL cytoplasm. Since virus particles in vacuoles are most likely to be degraded, we considered virus particles present in the cytoplasm of cocultured PMNLs as potentially representing HCMV infectious virus. Similarly, we believe that the newly synthesized pp65, prior to being assembled into dense bodies, may travel through membrane discontinuation tracts, rapidly reaching PMNL nuclei driven by its nuclear localization signals (9, 30), whereas pp65 sequestered as dense bodies into endocytosis vacuoles is likely to be degraded. Recently, abortive human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection of HUVEC has been rescued by T cells after coculture. The mechanism has been attributed to a direct cell-to-cell contact followed by fusion events consisting of discrete tracts of discontinuity between the adhering membranes of HUVEC and T cells (8). Cell adhesion is mediated partially by interactions between ICAM-1 and LFA-1, which have been considered a critical step in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-mediated syncytia formation (5).

However, the direct demonstration of the fusion of the two adhering membranes was obtained by showing the appearance of a yellow-greenish staining in PMNL nuclei, derived from the mixing of two vital fluorescent dyes staining HUVEC (green) and PMNLs (orange), respectively. In addition, it was shown that one of these fluorescent probes was able to move rapidly to PMNL nuclei after coculture with VR6110-infected cells. This property was hypothetically attributed to the binding of the dye to a protein of infected cells with nuclear targeting. This protein was likely to be the HCMV pp65 due to its strong nuclear targeting in PMNLs (8, 28), its diffuse nuclear localization in PMNLs along with the fluorescent probe staining HCMV-infected HUVEC, and the overlapping number of pp65-positive and fluorescent probe-labeled PMNL nuclei observed in parallel experiments. This phenomenon was totally absent when laboratory-adapted HCMV strains were used. In addition, it was shown that both pp65 and p72 localize in the nucleus of the same PMNLs, thus confirming that different viral products entered the same cells.

In this study, no pp65-positive or infectious virus-positive PMNL was found after coculture with HELF infected with HCMV AD169, Towne, or Davis, thus confirming previously reported data (27). These findings support the view that a genetic viral factor (now under investigation) differentiates clinical and laboratory-adapted HCMV strains. In addition, unlike clinical isolates, attenuated strains AD169 and Towne were found to have a slower replication rate in thymic stromal cells of SCID-hu mice (4) and to lack a large region of DNA (6).

Furthermore, we investigated whether infectious virus transferred into PMNLs after 1 to 3 h of coculture could further be transmitted to susceptible HUVEC or HELF cells. It was found that transmission from cocultured PMNLs to susceptible cells occurred, as it was already known to occur for PMNLs from patients with disseminated HCMV infection (15, 29, 37). In this study, transmission could be prevented by lack of contact between the two cell populations and by the use of monoclonal antibodies to CD18 or ICAM-1 or both but not by monoclonal antibodies to E-selectin, PECAM-1, or ICAM-3. In this respect, it is well known that HCMV recovery from ex vivo PMNL is successful only when viable and nonsonicated cells are used, is improved by centrifuging PMNL suspensions onto cell monolayers, and occurs in such a way that a single HELF cell is infected by a single PMNL carrying infectious virus (15). All these data support the need for a cell-to-cell contact for recovery of HCMV from infected PMNLs.

The copy number of nucleic acids per infected HUVEC was in the order of 104 to 105, while it was in the order of 101 to 102 in PMNLs after coculture. On this basis, one can argue that active transfer must be mediated by very rapid microfusion events. In addition, the number of cocultured PMNLs positive for viral DNA approached 100% after 24 h of coculture (data not reported), while it was high for pp65 and p72 antigens and IE-mRNA and low for infectious virus and pp67 mRNAs. The finding that the great majority or the totality of PMNLs become DNA positive during a period of coculture of 24 h indicates that all PMNLs come in contact with infected cells and receive a small amount of infected material during such lag time.

Finally, the data reported in the present study indicate that HCMV infectious virus, pp65 and p72 antigens, viral DNA, and IE and pp67 mRNAs in ex vivo PMNL preparations from immunocompromised patients with disseminated infection are surrogate markers of HCMV infection and cannot be considered as direct indicators of HCMV replication in vivo.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are indebted to Luca Dossena and Gabriella Garbagnoli for excellent technical assistance. We thank Laura Salvaneschi for providing buffy coat preparations, Patrizia Vaghi for helping with confocal microscopy, and Linda D'Arrigo for revision of the English. We thank J. Middeldorp, Organon Teknika, for providing reagents for NASBA determinations.

This work was partially supported by Ministero della Sanità, Ricerca Finalizzata, grant no. 030RFM 98/01, by Istituto Superiore di Sanità, II Programma Nazionale di Ricerca, sull'AIDS, grant no. 50B.21, and by Ricerca Corrente 1998, IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bitsch A, Kirchner H, Dupke R, Bein G. Cytomegalovirus transcripts in peripheral blood leukocytes of actively infected transplant patients detected by reverse-transcription-polymerase chain reaction. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:740–743. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.3.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blok M J, Goossens V J, Vanherle S J V, Top B, Tacken N, Middeldorp J M, Christiaans M H L, van Hooff J P, Bruggeman C A. Diagnostic value of monitoring human cytomegalovirus late pp67 mRNA expression in renal-allograpt recipients by nucleic acid-sequence based amplification. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1341–1346. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.5.1341-1346.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boivin G, Handfield J, Toma E, Lalonde R, Bergeron M G. Expression of the late cytomegalovirus (CMV) pp150 transcript in leukocytes of AIDS patients is associated with a high viral DNA load in leukocytes and presence of CMV DNA in plasma. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:1101–1107. doi: 10.1086/314721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown J M, Kaneshima H, Mocarski E S. Dramatic interstrain differences in the replication of human cytomegalovirus in SCID-hu mice. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:1599–1603. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.6.1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butini L, De Fougerolles A R, Vaccarezza M, Graziosi C, Cohen D I, Montroni M, Springer T A, Pantaleo G, Fauci A S. Intracellular adhesion molecules (ICAM)-1, ICAM-2, and ICAM-3 function as counter-receptor for lymphocyte function-associated molecule 1 in human immunodeficiency virus-mediated syncytia formation. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:2191–2195. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cha T-H, Tom E, Kemble G W, Duke G M, Mocarski E S, Spaete R S. Human cytomegalovirus clinical isolates carry at least 19 genes not found in laboratory strains. J Virol. 1996;70:78–83. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.78-83.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cybulsky M I, Fries J W U, Williams A J, Sultan P, Eddy R, Byers M, Shows T, Gimbrone M A, Jr, Collins T. Gene structure, chromosomal location, and basis for alternative mRNA splicing of the human VCAM1 gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:7859–7863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.17.7859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dianzani F, Scheglovitova O, Gentile M, Scanio V, Barresi C, Ficociello B, Bianchi F, Fiumara D, Capobianchi M R. Interferon gamma stimulates cell-mediated transmission of HIV tipe 1 from abortively infected endothelial cells. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1996;12:621–627. doi: 10.1089/aid.1996.12.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallina A, Percivalle E, Simoncini L, Revello M G, Gerna G, Milanesi G. Human cytomegalovirus pp65 lower matrix phosphoprotein harbours two transplantable nuclear localization signals. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:1151–1157. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-6-1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerna G, Zipeto D, Percivalle E, Parea M, Revello M G, Maccario R, Peri G, Milanesi G. Human cytomegalovirus infection of the major leukocyte subpopulations and evidence for initial viral replication in polymorphonuclear leukocytes from viremic patients. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:1236–1244. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.6.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerna G, Percivalle E, Torsellini M, Revello M G. Standardization of the human cytomegalovirus antigenemia assay by means of in vitro generated pp65-positive peripheral blood polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3585–3589. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.12.3585-3589.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerna G, Baldanti F, Middeldorp J M, Furione M, Zavattoni M, Lilleri D, Revello M G. Clinical significance of expression of human cytomegalovirus pp67 late transcript in heart, lung and bone marrow transplant recipients as determined by nucleic acid sequence-based amplification. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:902–911. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.4.902-911.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerna G, Furione M, Baldanti F, Sarasini A. Comparative quantitation of human cytomegalovirus DNA in blood leukocytes and plasma of transplant and AIDS patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2709–2717. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.11.2709-2717.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerna G, Revello M G, Percivalle E, Morini F. Comparison of different immunostaining techniques and monoclonal antibodies to the lower matrix phosphoprotein (pp65) for optimal quantitation of human cytomegalovirus antigenemia. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1232–1237. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.5.1232-1237.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerna G, Revello M G, Percivalle E, Zavattoni M, Parea M, Battaglia M. Quantification of human cytomegalovirus viremia by using monoclonal antibodies to different viral proteins. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:2681–2688. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.12.2681-2688.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gozlan J, Salord J M, Chouaïd C, Duvivier C, Picard O, Mejohas M C, Petit J C. Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) late mRNA detection in peripheral blood of AIDS patients: diagnostic value for HCMV disease compared with those of viral culture and HCMV DNA detection. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1943–1945. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.7.1943-1945.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gozlan J, Laporte J P, Lesage S, Labopin M, Najman A, Gorin N C, Petit J C. Monitoring of cytomegalovirus infection and disease in bone marrow recipients by reverse trascription-PCR and blood and urine culture. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2085–2088. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.9.2085-2088.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grefte A, Harmsen M C, van der Giessen M, Knollema S, van Son W J, The T H. Presence of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) immediate-early mRNA but not pp UL83 (lower matrix protein pp65) mRNA in polymorphonuclear and mononuclear leukocytes during active HCMV infection. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:1989–1998. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-8-1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grundy J E, Lawson K M, MacCormac L P, Fletcher J M, Yong K L. Cytomegalovirus-infected endothelial cells recruit neutrophils by the secretion of C-X-C chemokines and transmit virus by direct neutrophil-endothelial cell contact and during neutrophil transendothelial migration. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:1465–1474. doi: 10.1086/515300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hession K, Tizard R, Vassallo C, Schiffer S B, Goff D, Moy P, Chi-Rosso G, Luhowski S, Lobb R, Osborn L. Cloning of an alternate form of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM1) J Biol Chem. 1991;266:6682–6685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaroszeski M J, Gilbert R, Heller R. Detection and quantitation of cell-cell electrofusion products by flow cytometry. Anal Biochem. 1994;216:271–275. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lam K M C, Oldenburg N, Khan M A, Gaylore V, Mikhail G W, Stroual P D, Middeldorp J M, Banner N, Yacoub M. Significance of reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction in the detection of human cytomegalovirus gene transcripts in thoracic organ transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1998;17:555–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meyer T, Reischl U, Wolf H, Schuller C, Arndt R. Identification of active cytomegalovirus infection by analysis of immediate-early, early and late transcripts in peripheral blood cells of immunodeficient patients. Mol Cell Probes. 1994;8:261–271. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.1994.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meyer-König U, Serr A, van Laer D, Kirste G, Wolff C, Haller O, Neuman-Haefelin D, Hufert F T. Human cytomegalovirus immediate-early and late transcripts in peripheral blood leukocytes: diagnostic value in renal transplant recipients. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:705–709. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.3.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nelson P N, Kawal B K, Boriskin Y S, Mathers K E, Powles R L, Steel H M, Tryhorn Y S, Butcther P D, Booth J C. A polymerase chain reaction to detect a spliced late transcript of human cytomegalovirus in the blood of bone marrow transplant recipients. J Virol Methods. 1996;56:139–148. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(95)01900-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Randhawa P S, Manez R, Frye B, Ehrlich G D. Circulating immediate-early mRNA in patients with cytomegalovirus infections after solid organ transplantation. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:1264–1267. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.5.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Revello M G, Percivalle E, Arbustini E, Pardi R, Sozzani S, Gerna G. In vitro generation of human cytomegalovirus pp65 antigenemia, viremia, and leukoDNAemia. J Clin Investig. 1998;101:2686–2692. doi: 10.1172/JCI1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Revello M G, Percivalle E, Zavattoni M, Parea M, Grossi P, Gerna G. Detection of human cytomegalovirus immediate early antigen in leukocytes as a marker of viremia in immunocompromised patients. J Med Virol. 1989;29:88–93. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890290204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saltzmann R L, Quirk M R, Jordan M C. Disseminated cytomegalovirus infection. Molecular analysis of virus and leukocyte interactions in viremia. J Clin Investig. 1988;81:75–81. doi: 10.1172/JCI113313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmolke S, Drescher P, Jahn G, Plachter B. Nuclear targeting of the tegument protein pp65 (UL83) of human cytomegalovirus: an unusual bipartite nuclear localization signal functions with other portions of the protein to mediate its efficient nuclear transport. J Virol. 1995;69:1071–1078. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.2.1071-1078.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stanier P, Taylor D L, Kitchen A D, Wales N, Tryhorn Y, Tyms A S. Persistence of cytomegalovirus in mononuclear cells in peripheral blood from blood donors. Br Med J. 1989;299:897–898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.299.6704.897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor-Wiedeman J, Hayhurst G P, Sissons J G P, Sinclair J H. Polymorphonuclear cells are not sites of persistence of human cytomegalovirus in healthy individuals. J Gen Virol. 1993;74:265–268. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-2-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor-Wiedeman J, Sissons J G P, Borysiewicz L K, Sinclair J H. Monocytes are a major site of persistence of human cytomegalovirus in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:2059–2064. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-9-2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van der Bij W, Schirm J, Torensma R, van Son W J, Tegzess A M, The T H. Comparison between viremia and antigenemia for detection of cytomegalovirus in blood. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:2531–2535. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.12.2531-2535.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Velzing J, Rothbarth P H, Kroes A C M, Quint W G V. Detection of cytomegalovirus mRNA and DNA encoding the immediate-early gene in peripheral blood leukocytes from immunocompromised patients. J Med Virol. 1994;42:164–169. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890420212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.von Laer D, Serr A, Meyer-König U, Kirste G, Hufert F T, Haller O. Human cytomegalovirus immediate early and late transcripts are expressed in all major leukocyte populations in vivo. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:365–370. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.2.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zaia J A, Forman S J, Gallagher M T, Vanderwal-Urbina E, Blume K G. Prolonged human cytomegalovirus viremia following bone marrow transplantation. Transplantation. 1984;37:315–317. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198403000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]