Abstract

Background:

Since the resurgence of mpox disease in 2017, Nigeria alone has accounted for about 60% of confirmed cases reported in the African region. This study therefore aimed to understand the knowledge and perception of the general public towards the mpox infection.

Methods:

We conducted a cross-sectional study among 958 community members across three states (Oyo, Lagos and Jigawa) in Nigeria. Knowledge of mpox infection was assessed across four domains: (1) general knowledge, (2) transmission, (3) signs and symptoms, and (4) prevention and treatment where we assigned a score of 1 for each correct response. Binary logistic regression was conducted to explore factors associated with knowledge of mpox infection at 5% level of significance. We assessed perception of mpox infection across 5 constructs (perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, and self-efficacy) from the health belief model, using 3-point Likert scales. We used Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney- U tests to assess factors associated with each construct.

Results:

Overall, only about one-third (38.3%) of community members were aware of mpox infection. There were variations in perceptions and knowledge across the three states. Knowledge of mpox infection transmission, prevention, and treatment was low across the states. Only 28.9% of respondents knew that sharing utensils with an infected person is a means of contracting the disease, and just 15.9% were aware that mpox infection may resolve spontaneously. The mean of general knowledge scores was higher in Jigawa 14.8 (±3.2) compared to Lagos 12.1 (±4.1) and Oyo states 12.5 (±5.6) (p<0.001).

Respondents with tertiary-level education (p=0.001) were significantly more likely to perceive themselves as susceptible to mpox while males (p<0.001) and respondents who live in Jigawa state (p=0.002) were significantly more likely to perceive mpox as severe with 90.5% believing that being infected will stop their daily activity (p<0.001). Perceived barriers to adherence to mpox preventive strategies were higher in Jigawa state (p<0.001), with 68.3% reporting that use of hand sanitizers might be expensive for them.

Conclusion:

The analysis of our findings revealed significant knowledge gaps and a very low level of public awareness about mpox. Key areas of limited knowledge included the disease's route of transmission, as well as its prevention and treatment. To control the spread of mpox infection, there is need to strengthen public health risk communication focusing on the transmission and preventive actions.

Keywords: Knowledge, Severity, Risk perception, Disease, Outbreak, MPOX, Sub-Saharan Africa

BACKGROUND

Mpox is a re-emerging zoonosis disease that was first identified in humans in 1970.1 While initially originating and prevalent in central and western Africa, mpox spread beyond the continent in 2003 when the United States reported its first case2, thereafter, sporadic cases of mpox have been reported across Africa. On July 23, 2022, mpox was officially declared a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) by the World Health Organisation (WHO) due to the discovery of multiple cases of human-to-human transmission in previously non-endemic, high-income countries including the United States and the United Kingdom.3 Between January 1, 2022, and January 30, 2023, WHO reported 85,449 confirmed global cases of mpox, with 89 resulting in death.4 The majority of these cases occurred in region of the Americas (57,989; 68%), followed by Europe (25,804; 30%), and the African region (1,302;1.5%).5 However, underreporting of mpox infection and other related diseases is a significant concern in Africa, particularly in rural areas, due to limited medical facilities, self-medication, and a poor illness reporting culture.6 To facilitate an effective public health response and community engagement, it is essential to understand the knowledge and perception of the general public towards the mpox infection.

Between 2017-2022, Nigeria reported sporadic cases of mpox infection, with only 512 suspected cases and 226 confirmed cases between 2017 and 2021. However, the number of reported cases surged significantly in 2022, with the country documenting 2,123 suspected cases and 762 confirmed cases across 34 states and the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) in that year alone. This figure accounts for approximately 60% of confirmed cases in the African region.7

Since the resurgence of the disease in 20178, the Nigerian government has implemented specific response activities to protect the health of Nigerians. These measures include providing technical assistance to high burden states, establishing immediate and real-time reporting, provision of specific guidelines for the disease, and training of personnel on early case detection and reporting of mpox infection and other high priority diseases using an integrated disease approach among other initiatives.9 Despite these efforts, the National Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (NCDC) reported 71 newly confirmed cases of mpox infection between January 1, 2023 and April 16, 2023.7 This indicates a continuing challenge, especially considering that most control plans are aimed at healthcare workers. While this increase in number of cases may be due to the effects of climate change and increased interaction between man and animal, the awareness and knowledge of community members about mpox infection are important for community actions that can prevent outbreaks and limit contagion if an outbreak occurs.

Previous studies on mpox infection knowledge and perception have primarily focused on healthcare workers (HCW) and critical stakeholders. Some of these studies were conducted through online surveys on social media platforms, limiting reach to rural populations where technology use is lowest and disease underreporting is highest.10-12 To the best of our knowledge, there is limited evidence of in-person survey on mpox infection among community members in many Nigerian states including Jigawa. There are also no studies comparing mpox knowledge and risk perception across geo-political zones. Therefore, to address this gap, our study aims to measure the knowledge and risk perception of mpox infection among community members in Jigawa, Oyo, and Lagos States. The results of this study will help develop effective strategies to educate the public and guide policy formulation for public health intervention towards the prevention and control of mpox infection in Nigeria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

We conducted a community-based cross-sectional study among members in three states in Nigeria: Jigawa (northwest geopolitical zone), Oyo and Lagos (southwest geopolitical zone) from August 15, 2022 to November 30, 2022.

Study settings

Jigawa state in northwest Nigeria is predominantly inhabited by Hausa and Fulani ethnic groups, with Islam as the predominant religion. Oyo and Lagos are located in southwest Nigeria and both states are predominantly inhabited by the Yoruba ethnic group with a fairly equal distribution of Christians and Muslims. Lagos state has the highest projected population estimate of the three states, with a population of over 12 million, while both Oyo and Jigawa state stand at 7.5 million and 6.7 million respectively.13

In Jigawa state, Kiyawa (rural) and Dutse (Urban) Local Government Areas (LGAs) were selected. In Oyo state, Lagelu (peri-urban) and Ibadan southwest LGA (urban) were selected, while in Lagos state, Ikorodu LGA (peri-urban), was selected. This selection offers a geographically diversified picture of Nigeria in terms of culture and socioeconomic factors. We used convenient sampling to select the state and the LGAs, based on an ongoing research in these settings, unrelated to mpox infection.14,15

Study population

The data was collected from community members present at the facility on the day of the visit, and participation in the study was voluntary and did not include compensation.

Sample size

The sample size calculation was based on the formula , where q = 1 - p for estimating proportions, where p is the level of awareness of mpox infection which is taken as 92% based on study conducted in Bayelsa state among community members.16

= 124 respondents in each state (after adjusting for 10% non-response rate which is 11.3)

Sampling technique

We obtained a list of registered primary healthcare facilities in each chosen LGA from the government database, and randomly selected 10 operational primary healthcare facilities, excluding the health posts. Overall, we included 50 primary health centres (see appendix) across all 5 LGAs. We employed convenience sampling approach to select community members for the study as long as the participant was up to 18 years of age and was able to communicate in English language or the predominant native languages (Hausa, Fulani and Yoruba) in the selected states.

Data collection

Data collectors with a minimum of secondary education and who have proficiency in the local dialects of the study area were engaged and trained to carry out an interviewer administered survey. Data collectors were exposed to a 3-day classroom training and another 3 days field practice. Thereafter, we conducted a study pretest which lasted for a period of 2 weeks at health posts within the 5 LGA selected for the study. Data was collected on Android tablets using Open Data Kit (ODK). Each selected facility was visited between 1 to 3 times, and to minimize duplicating interviews, we assigned data collectors to specific facilities and we asked if respondents had been approached for the study within the time frame of commencement. The study team met every two weeks to swiftly address arising issues and to periodically clean and verify the data to ensure its quality.

Data Management and Analysis

We described respondents’ sociodemographic characteristics and awareness of mpox infection using summary statistics. We then evaluated knowledge of mpox infection based on information provided on mpox infection by the WHO and NCDC.(1,9) To ensure a clear understanding of individual knowledge, we categorized knowledge questions into four distinct areas: (1) general knowledge of mpox, (2) mode of transmission of mpox, (3) signs and symptoms of mpox, and (4) prevention and treatment of mpox. We assigned a score of 1 (one) to each correct response based on the scoring system outlined in the National Mpox Public Health Response Guidelines,17 resulting in maximum score of 21 (twenty-one) for anyone who answered all questions correctly. The composite score was then reclassified as good if the participant scores at least 13 points (mean) and poor if the point was less than 13. Association between respondent’s sociodemographic characteristics and good knowledge of mpox infection were assessed using logistic regression.

We assessed respondents’ perception on mpox infection using the Health Belief Model (HBM), a theoretical framework that explains individuals perceive health risks and their propensity to engage in health-related behaviours.18 The five constructs from the HBM include: perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, and self-efficacy.19 This model has been used for studies on other diseases and infections in this setting. They include, diabetes mellitus,20 COVID-19,21 HIV/AIDS22 amongst others. We used a 3-point Likert scale to ask questions that measured respondents’ perceptions of each construct of the HBM, while assigning a score of 1 point to the response that favours the focus of each question. Subsequently, we calculated the overall score for each HBM construct and analysed using Kruskal-Wallis and Mann Whitney U test to assess associated factors where appropriate. The Kruskal-Wallis test is most suitable for showing differences between 3 groups, while the Mann Whitney U test shows whether there is a rank sum difference between independent samples with dependent variables that are not normally distributed.

Ethical Considerations

The Helsinki Declaration and the Nigerian National Code of Health Research Ethics were followed in this investigation. Ethical approval was obtained from the relevant authorities, including the Jigawa State Government (ref: JGHREC/2022/110), Lagos State Government (LREC/06/10/2022) and Oyo State Ministry of Health (ref: AD/13/479/44533). All participants gave verbal consent prior to taking part, and they were given the chance to read the informed consent form. Participants were specifically informed that participation was voluntary and that the information gathered would only be utilized for research purposes.

RESULTS

Participants Description

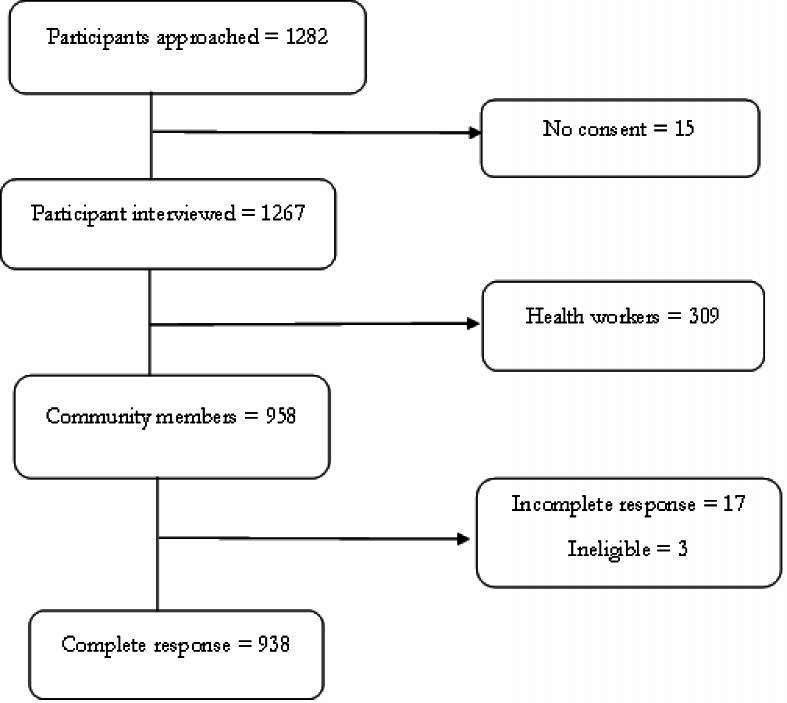

In total, we recruited 958 community members, and excluded 17 community members with a high number of incomplete responses, and 3 ineligible respondents, leaving us with 938 community members for analysis (Fig 1). Of the 938 eligible participants, 421 (44.9%) were recruited from Oyo state, 268 (28.6%) from Jigawa state and 249 (26.5%) from Lagos state. The majority (81.3%) of respondents in Jigawa did not attain higher than a primary education while respondents in Lagos (94.4%) and Oyo (79.3%) had a minimum of secondary education. In addition, more than three-quarters of respondents in Oyo (87.2%), Jigawa (78.7%), and Lagos (77.1%) were females. Furthermore, respondents in Lagos (79.9%) and Oyo (96.7%) states were mostly Yoruba, while those in Jigawa were all (100.0%) Hausa/Fulani (Table 1).

Figure. 1:

Source of information on Mpox infection by state

Table 1:

Respondents’ characteristics and awareness of mpox among community members in Nigeria (N= 938)

| Respondent variables | Jigawa | Lagos | Oyo | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | ||

|

| |||||||

| Total | 268 | (28.6) | 249 | (26.5) | 421 | (44.9) | |

| Age* | 18-29 years | 142 | (53.4) | 87 | (38.2) | 137 | (55.5) |

| 30-44 years | 106 | (39.8) | 101 | (44.3) | 88 | (35.6) | |

| 45 years and above | 18 | (6.8) | 40 | (17.5) | 22 | (8.9) | |

| Highest Level of Education | Primary or less | 218 | (81.3) | 14 | (5.6) | 87 | (20.7) |

| Secondary | 37 | (13.8) | 93 | (37.3) | 203 | (48.2) | |

| Tertiary/further | 13 | (4.9) | 142 | (57.1) | 131 | (31.1) | |

| Ethnicity | Yoruba | 0 | (0.0) | 199 | (79.9) | 407 | (96.7) |

| Hausa/Fulani | 268 | (100.0) | 5 | (2.0) | 4 | (0.9) | |

| Igbos and others | 0 | (0.0) | 45 | (18.1) | 10 | (2.4) | |

| Marital status | Never married | 239 | (89.2) | 186 | (74.7) | 342 | (81.2) |

| Ever married | 29 | (10.8) | 63 | (25.3) | 79 | (18.8) | |

| Religion** | Christianity | 1 | (0.4) | 183 | (73.8) | 238 | (57.6) |

| Islam | 267 | (99.6) | 65 | (26.2) | 175 | (42.4) | |

| Gender | Female | 211 | (78.7) | 192 | (77.1) | 367 | (87.2) |

| Male | 57 | (21.3) | 57 | (22.9) | 54 | (12.8) | |

| Occupation*** | Farming/Manual labour | 97 | (36.5) | 47 | (18.9) | 137 | (33.6) |

| Business owner | 80 | (30.1) | 105 | (42.3) | 152 | (37.4) | |

| Professional | 13 | (4.9) | 62 | (25.0) | 57 | (14.0) | |

| Not working/Apprentice | 76 | (28.5) | 34 | (13.7) | 61 | (15.0) | |

| Average Monthly Income | Less than 30,000 | 148 | (55.3) | 20 | (8.0) | 63 | (15.0) |

| 30,000 and above | 11 | (4.1) | 36 | (14.5) | 38 | (9.0) | |

| No response | 109 | (40.7) | 193 | (77.5) | 320 | (76.0) | |

| Awareness of mpox**** | No | 208 | (76.8) | 71 | (28.6) | 259 | (61.7) |

| Yes | 63 | (23.2) | 177 | (71.4) | 161 | (38.3) | |

Missing respondent age (n= 190)

Missing respondent religion (n=9)

Missing occupation (n=17)

Missing awareness (n=2)

Awareness of Mpox among community members in Nigeria

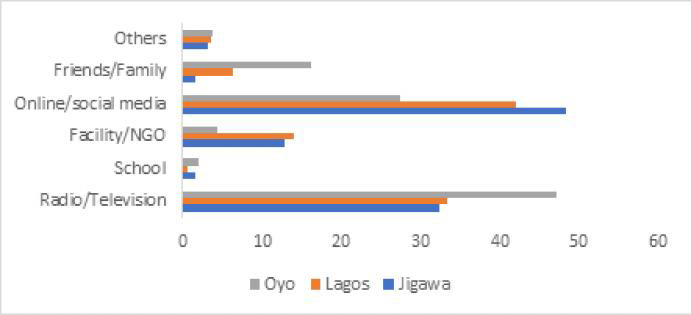

Overall, 42.6% (401/941) of community members reported being aware of mpox infection. Awareness of mpox infection was highest in Lagos state (177/249, 71.4%), and lowest in Jigawa state (63/271, 23.2%). Of the 401 participants who were aware of mpox infection, 63/401 (15.7%), 161/401 (40.2%) and 177/401 (44.1%), and were from Jigawa, Oyo and Lagos states, respectively. Radio/television (151, 37.7%) and internet/social media (146, 36.4%) were the major sources of information across all three states (Fig 1).

Knowledge of Mpox among community members in Nigeria

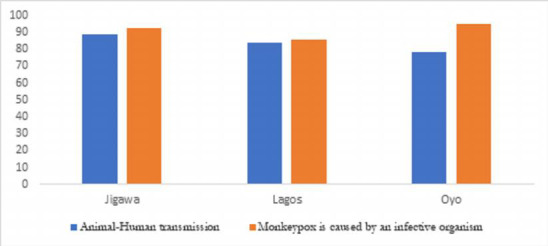

Among respondents who reported awareness of mpox infection across the three states, about 90% (362/401) knew that mpox infection is caused by an infectious organism and can be transmitted from animals to human (Fig 2). However, knowledge of mpox infection transmission was relatively low compared to other domains. Only about a quarter of the respondents (28.9%) knew that mpox infection can be transmitted through sharing of utensils with an infected person (28.6% in Jigawa, 26.5% in Lagos, and 31.7% in Oyo), and 65.3% knew that transmission can occur through contact with infected animals while one-third (32.9%) knew that mpox infection can be transmitted through sexual intercourse with an infected person. Just 23.7% knew that there is an available vaccine for mpox, which is the smallpox vaccine (Table 2).

Figure. 2:

General knowledge of Mpox by state

Table 2:

Knowledge of mpox among community members in Nigeria (N= 401)

| Variables - Knowledge of Mpox | Jigawa | (n=63) | Lagos | (n=177) | Oyo | (n=161) | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freq | (%) | Freq | (%) | Freq | (%) | Freq | (%) | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Knowledge of transmission | Mpox can be transmitted through | |||||||||

| Sharing of clothing, towel and bedding with infected person | Yes | 34 | (53.9) | 73 | (41.2) | 77 | (47.8) | 184 | (45.9) | |

| Sitting in the same vehicle with infected person | Yes | 13 | (20.6) | 46 | (26.0) | 44 | (27.3) | 103 | (25.7) | |

| Contact with body fluid of infected person | Yes | 44 | (69.8) | 106 | (59.9) | 109 | (67.7) | 259 | (64.6) | |

| Contact with infected animal | Yes | 52 | (82.5) | 95 | (53.7) | 62 | (38.5) | 209 | (52.1) | |

| Sexual intercourse with infected person | Yes | 31 | (49.2) | 59 | (33.3) | 42 | (26.1) | 132 | (32.9) | |

| Sharing utensils with an infected person | Yes | 18 | (28.6) | 47 | (26.5) | 51 | (31.7) | 116 | (28.9) | |

| Variables - Knowledge of signs and symptoms as listed by WHO1 | ||||||||||

| Fever | Yes | 62 | (98.4) | 146 | (82.5) | 123 | (76.4) | 331 | (82.5) | |

| Headache | Yes | 52 | (82.5) | 132 | (74.6) | 122 | (75.8) | 306 | (76.3) | |

| Back pains | Yes | 43 | (68.2) | 80 | (45.2) | 101 | (62.7) | 224 | (55.8) | |

| Swollen lymph nodes | Yes | 40 | (63.5) | 116 | (65.5) | 120 | (74.5) | 276 | (68.8) | |

| Rashes | Yes | 60 | (95.2) | 153 | (86.4) | 144 | (89.4) | 357 | (89.0) | |

| Variables - Knowledge of prevention and treatment | ||||||||||

| Avoiding consumption of bushmeat | Yes | 61 | (96.8) | 106 | (59.9) | 115 | (71.4) | 282 | (70.3) | |

| Disinfecting object regularly | Yes | 55 | (87.3) | 138 | (77.9) | 118 | (73.3) | 311 | (77.6) | |

| Proper cooking of animal product | Yes | 57 | (90.5) | 117 | (66.1) | 114 | (70.8) | 288 | (71.8) | |

| Following the healthcare worker's advice is important if I suspect that I have mpox | Yes | 63 | (100.0) | 149 | (84.2) | 142 | (88.2) | 354 | (88.3) | |

| People with mpox should avoid scratching their skin | Yes | 56 | (88.9) | 121 | (68.4) | 103 | (63.9) | 280 | (69.8) | |

| People with mpox should have enough sleep | Yes | 45 | (71.4) | 92 | (51.9) | 86 | (53.4) | 223 | (55.6) | |

| Mpox may resolve spontaneously | Yes | 16 | (25.4) | 19 | (10.7) | 29 | (18.0) | 64 | (15.9) | |

| There is an available vaccine for mpox | Yes | 16 | (25.4) | 50 | (28.2) | 29 | (18.0) | 95 | (23.7) | |

| Knowledge scores | Jigawa state | Lagos state | Oyo state | Total | ||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | (SD) p-value* | |||

| Knowledge of transmission (maximum possible score=6) | 3.0 | 1.5 | 2.4 | 1.8 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 2.5 (1.8) | 0.035 | ||

| Knowledge of signs and symptoms (maximum possible score=5) | 4.1 | 1.2 | 3.5 | 1.6 | 3.7 | 1.7 | 3.7 (1.6) | 0.060 | ||

| Knowledge of prevention and treatment (maximum possible score=8) | 5.8 | 1.3 | 4.5 | 2.0 | 4.6 | 2.3 | 4.7 (2.1) | <0.001 | ||

| Overall Knowledge of mpox (maximum possible score=21) | 14.8 | 3.2 | 12.1 | 4.1 | 12.5 | 5.6 | 12.7 (4.7) | <0.001 | ||

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA)

The overall mean knowledge score was higher in Jigawa (14.8 ± 3.2) compared to Lagos (12.1 ± 4.1) and Oyo (12.5 ± 5.6) (p<0.001). Knowledge of transmission (p<0.035) and knowledge of prevention and treatment (p<0.001) were higher in Jigawa state (Table 2). Community members who were ever married were twice as likely to have a good score (>13) in the general knowledge of mpox infection compared to those who were never married (AOR=2.93, 95% CI: 1.24-6.89), after adjusting for state and gender (Table 3).

Figure. 3:

Participant inclusion flow diagram

Perception of mpox infection among community members in Nigeria

When asked questions on perceived susceptibility to mpox infection, 314 (78.3.%) respondents agreed that mpox infection can affect anyone; however, only 31.7% believed they were personally susceptible to the disease. Furthermore, more than three-quarters (78.5%) of the respondents across the states perceived mpox infection as a severe disease, but only 36.4% believed they can die from the disease. In Jigawa state, a higher proportion (88.9%) of respondents perceived adherence to recommended protective measures against mpox infection to be difficult, compared to 61.6% in Lagos and 39.7% in Oyo state. Additionally, the cost of hand sanitizers was reported as a barrier for 68.3% of respondents in Jigawa state, compared to 26.0% in Lagos and 11.8% in Oyo who agreed that hand sanitizers were expensive (Table 4).

Table 4:

Perception of mpox among community members in Nigeria (N= 401)

| Total | Jigawa | Lagos | Oyo | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | ||

| 63 | (15.7) | 177 | (44.1) | 161 | (40.2) | 401 | (100.0) | ||

|

| |||||||||

| Perceived susceptibility about mpox | |||||||||

| I cannot contract mpox | Disagree (1) | 24 | (38.1) | 67 | (37.8) | 36 | (22.4) | 127 | (31.7) |

| It does not affect people in my locality | Disagree (1) | 17 | (26.9) | 77 | (43.5) | 67 | (41.6) | 161 | (40.1) |

| People around me are not at risk of mpox | Disagree (1) | 24 | (38.1) | 68 | (38.4) | 40 | (24.8) | 132 | (32.9) |

| I am immune to mpox | Disagree (1) | 15 | (23.8) | 73 | (41.2) | 85 | (52.8) | 173 | (43.1) |

| Mpox does not affect children | Disagree (1) | 32 | (50.8) | 107 | (60.4) | 82 | (50.9) | 221 | (55.1) |

| Mpox is severe in people with chronic health condition | Agree (1) | 35 | (55.5) | 87 | (49.1) | 95 | (59.0) | 217 | (54.1) |

| I may get mpox by having sexual intercourse with infected person | Agree (1) | 46 | (73.0) | 93 | (52.5) | 97 | (60.2) | 236 | (58.8) |

| It can affect anyone | Agree (1) | 60 | (95.2) | 144 | (81.4) | 110 | (96.1) | 314 | (78.3) |

| Variables – Perceived severity of mpox | |||||||||

| I think mpox is a very serious disease | Agree (1) | 57 | (90.5) | 140 | (79.1) | 118 | (73.3) | 315 | (78.5) |

| I will feel sick if I have mpox | Agree (1) | 59 | (93.6) | 139 | (78.5) | 123 | (76.4) | 321 | (80.0) |

| Being infected will stop my daily activities | Agree (1) | 57 | (90.5) | 134 | (75.7) | 117 | (72.7) | 308 | (76.8) |

| I may require hospitalization if I get mpox | Agree (1) | 58 | (92.0) | 133 | (75.1) | 131 | (81.4) | 322 | (80.3) |

| I think I can die from mpox | Agree (1) | 38 | (60.3) | 67 | (37.8) | 41 | (25.5) | 146 | (36.4) |

| Other members of my household will feel sick if I get mpox | Agree (1) | 49 | (77.8) | 117 | (66.1) | 116 | (72.0) | 282 | (70.3) |

| Variables – Perceived benefits of adherence to mpox preventive and control strategies | |||||||||

| My household will be safer if I protect myself from mpox | Agree (1) | 60 | (95.2) | 157 | (88.7) | 145 | (90.1) | 362 | (90.3) |

| I will not get mpox if I follow recommended precautionary measures | Agree (1) | 60 | (95.2) | 154 | (87.0) | 146 | (90.7) | 360 | (89.8) |

| Variables – Perceived barriers to adherence mpox preventive and control strategies | |||||||||

| Someone with mpox will be stigmatized | Agree (1) | 55 | (87.3) | 149 | (84.2) | 114 | (70.8) | 318 | (79.3) |

| Adherence to the recommended protective measures against Mpox is not easy | Agree (1) | 56 | (88.9) | 109 | (61.6) | 64 | (39.7) | 229 | (57.1) |

| Use of hand sanitizer is difficult because it is expensive for me. | Agree (1) | 43 | (68.3) | 46 | (26.0) | 19 | (11.8) | 108 | (26.9) |

| Variables – Perceived self-efficacy towards mpox preventive and control strategies | |||||||||

| I feel confident in my ability to stay safe from mpox | Agree (1) | 62 | (98.4) | 136 | (76.8) | 130 | (80.7) | 328 | (81.8) |

| I can comfortably abide by prevention guidelines released by the government | Agree (1) | 63 | (100.0) | 153 | (86.4) | 151 | (93.8) | 367 | (91.5) |

| Jigawa State | Lagos State | Oyo State | Total | ||||||

| Perception scores | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | |

| Perception of susceptibility (maximum possible score=8) | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| Perception of severity (maximum possible score=6) | 5 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 2 | |

| Perception on benefits of adherence (maximum possible score=2) | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| Perception on barriers to adherence (maximum possible score=3) | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |

| Perception on self-efficacy (maximum possible score=2) | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

Males (p=0.006) and respondents with tertiary-level education (p=0.001) were significantly more likely to perceive themselves as susceptible to mpox while males (p<0.001) and respondents who live in Jigawa state (p=0.002) were significantly more likely to perceive mpox as severe. In addition, male gender (p=0.011), living in Jigawa state (p<0.001), lower level of education (p<0.001) and practicing Islam (p<0.001) were associated with higher level of perceived barrier to mpox preventive strategies. We also found state (p=<0.001) and religion (p=<0.001) to be associated with higher perception of self-efficacy towards mpox infection preventive and control strategies, with higher self-efficacy among Muslims and residents of Jigawa state (Table 5).

Table 5:

Association between perception and selected respondents’ characteristics (N= 401)

| Perception of Susceptibility | |||||

| Respondent variables | Mean | SD | Mean ranking | P-value | |

|

| |||||

| State | Jigawa | 4.01 | 1.69 | 200.66 | 0.769* |

| Lagos | 4.04 | 2.39 | 205.38 | ||

| Oyo | 3.80 | 2.57 | 196.32 | ||

| Highest Level of Education | Primary or less | 3.24 | 2.15 | 165.69 | 0.001*α |

| Secondary | 3.42 | 2.28 | 175.40 | ||

| Tertiary/further | 4.41 | 2.36 | 224.62 | ||

| Respondent religion | Christianity | 4.07 | 2.46 | 206.64 | 0.126** |

| Islam | 3.75 | 2.21 | 188.77 | ||

| Gender | Female | 3.74 | 2.43 | 191.56 | 0.006** |

| Male | 4.48 | 2.08 | 226.92 | ||

| Occupation | Farmer | 3.65 | 1.53 | 180.18 | 0.009*v |

| Unskilled manual labour | 6.00 | 0.00 | 307.50 | ||

| Skilled manual labour | 3.32 | 2.54 | 171.52 | ||

| Business owner | 3.77 | 2.42 | 191.59 | ||

| Professional | 4.43 | 2.20 | 225.08 | ||

| Not working | 4.41 | 2.29 | 224.18 | ||

| Perception of Severity | |||||

| Respondent variables | Mean | ±SD | Mean ranking | P-value | |

| State | Jigawa | 5.04 | 1.12 | 245.97 | 0.002*β |

| Lagos | 4.12 | 1.97 | 194.01 | ||

| Oyo | 4.01 | 2.13 | 191.08 | ||

| Highest Level of Education | Primary or less | 4.29 | 2.07 | 213.77 | 0.198** |

| Secondary | 3.85 | 2.19 | 186.49 | ||

| Tertiary/further | 4.41 | 1.76 | 205.74 | ||

| Respondent religion | Christianity | 4.09 | 2.01 | 191.21 | 0.067** |

| Islam | 4.44 | 1.85 | 211.95 | ||

| Gender | Female | 4.05 | 2.03 | 190.25 | 0.001** |

| Male | 4.69 | 1.67 | 230.53 | ||

| Occupation | Farmer | 4.95 | 1.50 | 246.57 | 0.010* |

| Unskilled manual labour | 6.00 | 0.00 | 344.50 | ||

| Skilled manual labour | 3.75 | 2.11 | 173.66 | ||

| Business owner | 3.97 | 2.15 | 190.50 | ||

| Professional | 4.48 | 1.71 | 210.38 | ||

| Not working | 4.68 | 1.62 | 223.64 | ||

| Perception of benefits of adherence to mpox preventive and control strategies | |||||

| Respondent variables | Mean | ±SD | Mean ranking | P-value | |

| State | Jigawa | 1.90 | 0.34 | 212.69 | 0.251* |

| Lagos | 1.75 | 0.59 | 196.05 | ||

| Oyo | 1.80 | 0.53 | 201.86 | ||

| Highest Level of Education | Primary or less | 1.77 | 0.53 | 194.27 | 0.577* |

| Secondary | 1.78 | 0.54 | 198.80 | ||

| Tertiary/further | 1.81 | 0.53 | 204.00 | ||

| Respondent religion | Christianity | 1.78 | 0.56 | 198.00 | 0.593** |

| Islam | 1.82 | 0.49 | 201.74 | ||

| Gender | Female | 1.77 | 0.56 | 198.55 | 0.237** |

| Male | 1.85 | 0.44 | 207.71 | ||

| Occupation | Farmer | 1.90 | 0.31 | 208.30 | 0.557* |

| Unskilled manual labour | 2.00 | 0.00 | 227.00 | ||

| Skilled manual labour | 1.76 | 0.58 | 195.50 | ||

| Business owner | 1.75 | 0.59 | 193.46 | ||

| Professional | 1.86 | 0.45 | 207.96 | ||

| Not working | 1.83 | 0.53 | 206.69 | ||

| Perception of self-efficacy towards mpox preventive and control strategies | |||||

| Respondent variables | Mean | ±SD | Mean ranking | P-value | |

| State | Jigawa | 2.44 | 0.81 | 293.96 | <0.001*ε |

| Lagos | 1.71 | 0.87 | 209.89 | ||

| Oyo | 1.22 | 0.93 | 154.84 | ||

| Highest Level of Education | Primary or less | 2.22 | 1.15 | 271.47 | <0.001*ε |

| Secondary | 1.60 | 1.05 | 198.59 | ||

| Tertiary/further | 1.49 | 0.82 | 183.76 | ||

| Respondent religion | Christianity | 1.46 | 0.91 | 179.45 | <0.001** |

| Islam | 1.89 | 1.01 | 229.63 | ||

| Gender | Female | 1.55 | 0.99 | 192.45 | 0.011** |

| Male | 1.85 | 0.90 | 224.48 | ||

| Occupation | Farmer | 2.50 | 0.69 | 299.75 | <0.001*n |

| Unskilled manual labour | 3.00 | 0.00 | 357.50 | ||

| Skilled manual labour | 1.37 | 1.05 | 171.96 | ||

| Business owner | 1.74 | 1.00 | 213.40 | ||

| Professional | 1.52 | 0.83 | 187.63 | ||

| Not working | 1.63 | 0.94 | 248.41 | ||

| Perception of self-efficacy towards mpox preventive and control strategies | |||||

| Respondent variables | Mean | ±SD | Mean ranking | P-value | |

| State | Jigawa | 1.98 | 0.12 | 238.52 | <0.001*β |

| Lagos | 1.63 | 0.66 | 187.59 | ||

| Oyo | 1.74 | 0.53 | 201.05 | ||

| Highest Level of Education | Primary or less | 1.87 | 0.37 | 221.40 | 0.103* |

| Secondary | 1.69 | 0.58 | 194.65 | ||

| Tertiary/further | 1.71 | 0.60 | 199.16 | ||

| Respondent religion | Christianity | 1.65 | 0.62 | 187.90 | <0.001** |

| Islam | 1.84 | 0.45 | 216.93 | ||

| Gender | Female | 1.71 | 0.58 | 197.29 | 0.129** |

| Male | 1.79 | 0.52 | 211.19 | ||

| Occupation | Farmer | 1.95 | 0.22 | 231.65 | 0.394* |

| Unskilled manual labour | 2.00 | 0.00 | 241.00 | ||

| Skilled manual labour | 1.68 | 0.61 | 193.69 | ||

| Business owner | 1.69 | 0.61 | 194.37 | ||

| Professional | 1.74 | 0.57 | 202.61 | ||

| Not working | 1.78 | 0.50 | 207.68 | ||

Kruskal-Wallis H test

Mann-Whitney U test

pairwise comparison using Dunn’s test showed that Tertiary education is significant different from Primary education (p=<0.001) and Secondary education (p=<0.001)

pairwise comparison using Dunn’s test showed that Jigawa state is significant different from Oyo state (p=0.001) and Lagos state (p=0.002)

pairwise comparison using Dunn’s test showed that Jigawa state is significant different from Oyo state (p=<0.001) and Lagos state (p=<0.001)

pairwise comparison using Dunn’s test showed that Skilled manual labour is significant different from Professional/TBA (p=0.012) and Not working (p=0.029).

pairwise comparison using Dunn’s test showed that Farming is significantly different from Skilled manual labour (p=<0.001), Business owner (p=0.009), Professional/TBA (p==<0.001) and Not working (p=0.003).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we assessed community members’ levels of knowledge, awareness, and risk perception of mpox infection in three states in Nigeria: Jigawa, Lagos, and Oyo States. We found that overall awareness of mpox infection was low, with variations in perceptions and knowledge across the three states. Less than half of our respondents were aware of mpox infection, indicating a very low level of awareness among community members. Similarly, even when there is awareness, knowledge of mpox infection transmission, prevention, and treatment were uniformly low across the states, consistent with the findings of Al-Mustapha et al. in 202312. The highest knowledge gap was found in knowledge of transmission, considering that only very few of our participants knew that sharing of utensils with an infected person could lead to contracting the disease, and not many people knew that mpox could be transmitted through sexual intercourse with an infected person. Participants in this study commonly reported TV/radio and social media as their primary sources of information which is corroborated by other findings11, 12, 16. While social media is a valuable and reliable information source, it is also known for spreading misinformation23–25. Thus, public health authorities in Nigeria may consider establishing a radio station which is largely accessible to all.

We discovered variation in perceived severity of mpox infection and perceived susceptibility to mpox infection among community members. While many admitted that mpox infection can be severe and can affect anyone, their belief about the likelihood of contracting the disease was generally low. Given that respondents with a higher level of knowledge had a positive perception to susceptibility, low perceived susceptibility towards mpox infection may be linked to poor knowledge about the transmission of the disease26 affecting engagement and compliance with preventive behavior, as found in a study by Bawazir A et al. on knowledge and perceived susceptibility of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) among Saudi female teachers26. The positive perception to susceptibility seen amongst males may be a function of occupation, given that positive perception of mpox infection was higher amongst farmers compared to other job categories and the majority of the farmers in our study are males. Anecdotally, this might be because farmers work primarily in forests, where they feel more exposed to animals. However, there is need for more research to be done to highlight the interaction between gender and perceptions to susceptibility of an individual towards mpox infection. In addition, the reason for higher perceived severity of mpox in Jigawa could be attributed to geographical factors, given the disparities in the distribution of healthcare resources and access to care across states and geopolitical zones, with the most significant health inequity observed in Northern Nigeria where Jigawa belongs.27, 28.

We also found perceived barrier to adherence to mpox preventive and control strategies to be high among respondents across all states, with plenty of respondents reporting that adherence to the recommended protective measure against mpox is not easy and several others concerned about the level of stigmatization that may be associated with the disease. Fear of being stigmatized may lead to delay in disease disclosure which increases the risk of disease transmission. Thus, the need for the government to implement an anti-stigma intervention as proposed by Chang et al. based on socio-ecological model29.

Furthermore, many participants also reported the inability to afford hand sanitizers. This is plausible considering the high poverty headcount rate in Nigeria as of 201930, 31. Hence the need for the government to increase investments in social determinants of health such as poverty which is affecting human wellbeing. Likewise, practicing Islam was associated with a higher perceived barrier, although this may be a function of residence and education considering the fact that almost all the respondents from Jigawa state practice Islam and the majority of them have below secondary education, compared to residents in Lagos and Oyo state. As such, there should be improved provision for formal education across the country, particularly in Northern Nigeria.

Study Limitation

The main limitation of the study was that we did not include all six regions in Nigeria. As a result, the generalisability of our findings may be restricted to some areas. Secondly, participants were recruited in health facilities, so respondents in our study may have higher health literacy level. The strength of this study lies in its potential in adding to the body of knowledge especially in the areas of risks of transmission, social determinants of health, geographical variation in knowledge of mpox.

CONCLUSION

There are significant knowledge gaps and a very low level of public awareness about mpox infection especially in the route of transmission, as well as its prevention and treatment. Therefore, in order to control the spread of mpox infection, there is a need to strengthen public health risk communication with a focus on creating awareness and increasing transmission and preventive actions.

Table 3:

Unadjusted and multivariable logistic regression analysis of knowledge of mpox among community members in Nigeria

| Variables | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | p-value | Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | p-value | ||

|

| |||||||

| Respondent's age | 15-29 years | Ref | ref | ||||

| 30-44 years | 0.74 | (0.40 1.36) | 0.337 | 0.80 | (0.41 1.54) | 0.506 | |

| 45 years and above | 0.66 | (0.30 1.47) | 0.316 | 0.91 | (0.37 2.22) | 0.837 | |

| Level of Education | Primary or less | ref | ref | ||||

| Secondary | 0.71 | (0.27 1.86) | 0.496 | 0.81 | (0.29 2.20) | 0.681 | |

| Tertiary/further | 1.09 | (0.40 2.95) | 0.854 | 1.20 | (0.42 3.42) | 0.726 | |

| Respondent ethnicity | Yoruba | ref | ref | ||||

| Hausa/Fulani | 1.00 | (0.39 2.58) | 0.986 | 0.27 | (0.01 5.08) | 0.384 | |

| Others | 0.80 | (0.36 1.77) | 0.592 | 1.18 | (0.51 2.70) | 0.686 | |

| Marital status | Single/Never married | ref | ref | ||||

| Married/Married before | 2.77 | (1.26 6.10) | 0.011 | 2.93 | (1.24 6.89) | 0.013 | |

| Respondent religion | Christianity | ref | ref | ||||

| Islam | 1.17 | (0.63 2.17) | 0.610 | 0.83 | (0.42 1.62) | 0.589 | |

| Average Monthly Income | Less than 30,000 | ref | ref | ||||

| 30,000 and above | 1.35 | (0.53 3.42) | 0.516 | 1.53 | (0.57 4.08) | 0.388 | |

| No response | 0.56 | (0.26 1.21) | 0.144 | 0.79 | (0.36 1.75) | 0.576 | |

| Occupation | Farming/Manual | ref | ref | ||||

| Business owner | 0.57 | (0.30 1.09) | 0.094 | 0.59 | (0.30 1.19) | 0.145 | |

| Professional | 1.13 | (0.51 2.50) | 0.751 | 1.25 | (0.54 2.88) | 0.587 | |

| Not working/Apprentice | 0.61 | (0.24 1.55 | 0.300 | 0.55 | (0.20 1.49) | 0.247 | |

Table 6:

All knowledge of signs and symptoms

| Variables - Knowledge of signs and symptoms | Jigawa (n=80) | Lagos (n=83) | Oyo (n=76) | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freq | (%) | Freq | (%) | Freq | (%) | Freq | (%) | ||

|

| |||||||||

| Fever | Yes | 77 | (96.3) | 80 | (96.4) | 74 | (97.4) | 231 | (96.6) |

| Headache | Yes | 65 | (81.3) | 73 | (88.0) | 70 | (92.1) | 208 | (87.0) |

| Back pains | Yes | 49 | (61.3) | 47 | (56.6) | 53 | (69.7) | 149 | (62.3) |

| Swollen lymph nodes | Yes | 57 | (71.2) | 73 | (87.9) | 67 | (88.2) | 197 | (82.4) |

| Rashes | Yes | 77 | (96.3) | 83 | (100.0) | 72 | (94.7) | 232 | (97.1) |

| Vomiting of blood | Yes | 30 | (37.5) | 26 | (31.3) | 32 | (42.1) | 88 | (36.8) |

| Nose bleeding | Yes | 27 | (33.7) | 33 | (39.8) | 30 | (39.5) | 90 | (37.7) |

| Bloody urine | Yes | 24 | (30.0) | 25 | (30.1) | 26 | (34.2) | 75 | (31.4) |

| Limp paralysis | Yes | 22 | (27.5) | 22 | (26.5) | 27 | (35.5) | 71 | (29.7) |

| Cough | Yes | 55 | (68.7) | 40 | (48.2) | 59 | (77.6) | 154 | (64.4) |

| Sore throat | Yes | 52 | (65.0) | 54 | (65.1) | 59 | (77.6) | 165 | (69.0) |

Table 7:

| Respondent variables | Perception of Susceptibility | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean ranking | P-value | ||

|

| |||||

| Highest Level of Education | Farmer | 5.20 | 2.11 | 596.15 | 0.011** |

| Unskilled manual labour | 3.00 | 0.00 | 175.00 | ||

| Skilled manual labour | 3.09 | 2.07 | 169.32 | ||

| Business owner | 3.15 | 2.01 | 236.72 | ||

| Professional | 3.44 | 1.88 | 194.38 | ||

| Not working | 3.28 | 1.83 | 140.20 | ||

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO) Mpox (monkeypox), Key facts, overview, transmission, signs and symtoms, diagnosis, treatments and vaccination, selfcare and prevention, outbreaks, WHO respose. Internet. 2023. [cited 2023 May 21]. https://www.who.int/newsroom/fact-sheets/detail/monkeypox.

- 2.Singh S, Kumar R, Singh SK. All That We Need to Know About the Current and Past Outbreaks of Monkeypox: A Narrative Review. Cureus. 2022;14(11):e31109. doi: 10.7759/cureus.31109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO situation report. Multi-country monkeypox outbreak: situation update. Internet. 2022. [2023 Oct 12]. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreaknews/item/2022-DON393.

- 4.WHO. Multicountry outbreak of Mpox, Global trends. Internet. 2023. [2024 Feb 17]. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20230202_mpox_external-sitrep-15.pdf.

- 5.WHO. Multi-country outbreak of mpox. 2023 doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.001725. (October 2022):1–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oleribe OO, Momoh, Uzochukwu BSC, et al. Identifying key challenges facing healthcare systems in Africa and potential solutions. Int J Gen Med. 2019;12:395–403. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S223882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nigerian Centre for Disease Control. Title: Update on mpox in Nigeria. Situat Rep. Internet. 2023. https: ncdc.gov.ng.

- 8.Yinka-Ogunleye A, Aruna O, Dalhat M, et al. Outbreak of human monkeypox in Nigeria in 2017–18: a clinical and epidemiological report. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019 Aug;19(8):872–879. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30294-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.NCDC. Nigeria Centre for Disease Control and Prevention: NCDC Activates monkeypox emergency operations centre to strengthen in-country preparedness and contribute to the global response. Internet. 2022. [2023 May 21]. https://ncdc.gov.ng/news/368/ncdc-

- 10.Ugwu SE, Abolade SA, Ofeh AS, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and perception of monkeypox among medical/health students across media space in Nigeria. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2022 Nov;9(12):4391. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Awoyomi OJ, Njoga EO, Jaja IF, et al. Mpox in Nigeria: Perceptions and knowledge of the disease among critical stakeholders—Global public health consequences. PLoS ONE. 2023 Mar 1;18(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0283571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Mustapha AI, Ogundijo OA, Sikiru NA, et al. A cross-sectional survey of public knowledge of the monkeypox disease in Nigeria. BMC Public Health. 2023 Dec 1;23(1):591. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-15398-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Population Commission (NPC) [Nigeria] Nigeria’s Population: State by state according to NPC (2023) Internet. 2023. [2023 Jun 17]. https://schoolings.org/nigeriaspopulation-state-by-state-according-to-npc/

- 14.Graham HR, Olojede OE, Bakare AAA, et al. Pulse oximetry and oxygen services for the care of children with pneumonia attending frontline health facilities in Lagos, Nigeria (INSPIRINGLagos): Study protocol for a mixed-methods evaluation. [2022 May 2];BMJ Open. 2022 12(5) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-058901. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35501079/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.King C, Burgess RA, Bakare AA, et al. Integrated sustainable childhood pneumonia and infectious disease reduction in Nigeria (INSPIRING) through whole system strengthening in Jigawa, Nigeria: study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. [2022 Jun 24];Trials. 2022 23(1):95. doi: 10.1186/s13063-021-05859-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ajah Ikechukwu. Knowledge and Perception of Monkeypox Disease in Yenagoa, Bayelsa State 2020. https://www.academia.edu/82512924/Knowledge_and_Perception_of_Monkeypox_Disease_in_Yenagoa_Bayelsa_State.

- 17.NCDC. Monkeypox public health response guidelines. 2019.

- 18.Lee C. The Wiley Encyclopedia of Health Psychology. 2021. [cited 2024 Feb 17]. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/libarts_book/229/

- 19.Norman P, Conner M. Health Behavior. 2017 Jan 1. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/B9780128093245051439.

- 20.Agofure O, Oritseje EE, Oghenerume H. Applying the Health Belief Model on the Perception and attitude towards Diabetes Mellitus among public secondary school students in Southern Nigeria: A Cross-sectional Study. 2022 Oct 9;3 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adesina E, Oyero O, Amodu L, et al. Health belief model and behavioural practice of urban poor towards COVID-19 in Nigeria. [2021 Sep 20];Heliyon. 2021 7(9):e08037. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oyekale AS, Oyekale TO. Application of health belief model for promoting behaviour change among Nigerian single youth. Afr J Reprod Health. 2010;14(2):63–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanchan S, Gaidhane A. Social media role and its impact on public health: A narrative review. cureus. 2023;15(1):e33737. doi: 10.7759/cureus.33737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suarez-Lledo V, Alvarez-Galvez J. Prevalence of health misinformation on social media: systematic review. [2021 Jan 20];J Med Internet Res. 2021 23(1):e17187. doi: 10.2196/17187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.WHO review. Infodemics and misinformation negatively affect people’s health behaviours, new WHO review finds. 2022. [2023 Oct 12]. https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/01-09-2022-infodemics-andmisinformation-negatively-affect-people-s-healthbehaviours—new-who-review-finds.

- 26.Bawazir A. Knowledge and perceived susceptibility of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) among Saudi female teachers. [2020 Jun 29];Int Arch Public Health Community Med. 2020 4 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Musah K, Danjin M. Health inequities and socio-demographic determinants of health in Nigeria. 2018. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/350123782_Health_Inequities_and_Socio-demographic_Determinants_of_Health_in_Nigeria.

- 28.WHO. WHO | Regional Office for Africa. Addressing Inequity of Health Service-Delivery in Northern Nigeria. 2024. https://www.afro.who.int/news/addressing-inequityhealth-service-delivery-northern-nigeria.

- 29.Chang CT, Thum CC, Lim XJ, Chew CC, Rajan P. Monkeypox outbreak: Preventing another episode of stigmatization. Trop Med Int Health. 2022;27(9):754–757. doi: 10.1111/tmi.13798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Statista. Statista. Nigeria: poverty head count rate by state in Nigeria. 2019. [2023 Oct 12]. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1121438/poverty-headcount-rate-innigeria-by-state/

- 31.NBS. Nigeria Launches its Most Extensive National Measure of Multidimensional Poverty. National Bureau of Statistics. 2022. [2024 Feb 19]. https://nigerianstat.gov.ng/news/78.