Abstract

Primary simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) isolated from sooty mangabey (SIVsm [n = 6]), stumptail (SIVstm [n = 1]), mandrill (SIVmnd [n = 1]), and African green (SIVagm [n = 1]) primates were examined for their ability to infect human cells and for their coreceptor requirements. All isolates infected human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from a CCR5+/+ donor, and seven of eight isolates tested also infected CCR5−/− PBMCs. Analysis of coreceptor utilization using GHOST and U87 cell lines revealed that all of the isolates tested used CCR5 and the orphan receptors STRL33 and GPR15. Coreceptors such as CCR2b, CCR3, CCR8, and CX3CR1 were also utilized by some primary SIV isolates. More importantly, we found that CXCR4 was used as a coreceptor by the SIVstm, the SIVagm, and four of the SIVsm isolates in GHOST and U87 cells. These data suggest that primary SIV isolates from diverse primate species can utilize CXCR4 for viral entry, similar to what has been described for human immunodeficiency viruses.

Chemokine receptors (primarily CCR5 and CXCR4) are the major coreceptors used by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) for viral entry. In general, macrophage-tropic non-syncytium-inducing HIV-1 isolates use CCR5 for entry, while T-cell-tropic syncytium-inducing viruses use CXCR4 or multiple coreceptors, including CCR1 to CCR5, CXCR4, and GPR15 (also called BOB) (2, 3, 4, 11, 14, 20, 45, 47). Recent studies have also suggested that a switch in coreceptor use from CCR5 to CXCR4 or to multiple coreceptors correlates with disease progression (10, 46).

HIV-2 strains have similar tropism in which the predominant coreceptor used is CCR5. However, other coreceptors, including CCR1 to CCR5, CXCR4, STRL33 (also called Bonzo), and GPR15, can also be used by some HIV-2 strains (6, 23, 32, 37, 43; A. Heredia, A. Vallejo, V. Soriano, J. S. Epstein, and I. K. Hewlett, Letter, AIDS 11:1198–1199, 1997). Likewise, while CCR5 is known to be a coreceptor for simian immunodeficiency viruses (SIVs), until recently CXCR4 was thought not to function as a coreceptor for SIV, even by laboratory-adapted strains (7, 15, 24, 26, 29, 30, 42).

The inability of SIV isolates to use CXCR4 but to grow in CD4+ CCR5− human cells led to the discovery of two orphan receptors, STRL33 (17, 19; G. Alkhatib, F. Liao, E. A. Berger, J. M. Farber, and K. W. Peden, Letter, Nature 388:238, 1997) and GPR15 (12, 17, 19), which have been shown to be used by many SIV strains. The inability of SIV strains to use CXCR4 is unexpected, since phylogenetic analysis suggests that HIV-1 and HIV-2 originated from simian viruses found in chimpanzees and sooty mangabeys, respectively (21, 22). Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that various simian species from which SIVs have been isolated (chimpanzees, rhesus macaques, and sooty mangabeys) have CXCR4 genes that are highly homologous (>97%) to the human CXCR4 gene (7, 9, 30). Additionally, it has been demonstrated that the rhesus macaque CXCR4 can function as a coreceptor for HIV-1 T-cell-tropic isolates when expressed on human cells (9, 30). These findings suggest that the CXCR4 molecules expressed on simian cells should be capable of functioning as a coreceptor for SIVs. The demonstration that rhesus macaque CXCR4 is functional on human cells, together with the high homology of SIV isolates from sooty mangabeys to HIV-2 and the ability of HIV-2 to use CXCR4, led us to investigate the coreceptor utilization of primary SIV isolates derived from sooty mangabeys (SIVsm), a stumptail macaque (SIVstm), a mandrill (SIVmnd), and an African green monkey (SIVagm). We provide evidence that several primary SIV isolates are capable of using CXCR4. However, in some cases, the interaction between the SIV envelope and CXCR4 may occur in a manner slightly different than that reported for HIV-1 and CXCR4. The CXCR4 ligand SDF-1, a monoclonal antibody to CXCR4, and the CXCR4 antagonistic compounds T-22 and AMD3100 had variable abilities to block the entry of some of the CXCR4-utilizing SIV strains at concentrations that completely blocked HIV-1 entry.

Primary SIVs were isolated by cocultivation with either staphylococcal enterotoxin B-stimulated pigtail macaque (Macaca nemistrina) peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) or human PBMCs (both CCR5+/+ and CCR5−/−) that had been stimulated with phytohemagglutinin as described previously (35). The isolates used for coreceptor determination included six isolates from sooty mangabeys (SIVsm3, -9, -21, -54, -55, and -156, isolated at Yerkes Primate Center, Emory University, Atlanta, Ga.) and one isolate each from a stumptail macaque (SIVstm, isolated at California Regional Primate Center, Davis), an African green monkey (SIVagm Kenya, isolated at Institute of Primate Research, Nairobi, Kenya), and a mandrill (SIVmnd BK-12, isolated at California Regional Primate Center).

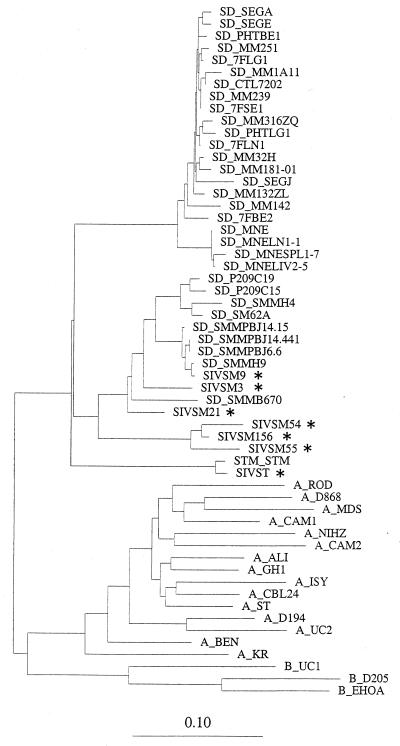

To determine the diversity present in the isolates used in the study, we PCR amplified, sequenced, and aligned the DNA sequences (300 to 350 bp) corresponding to the V3-to-V4 region of the envelope protein using primers and amplification conditions that have been previously described (1, 33, 37). Phylogenetic analysis of the SIVsm isolates using the neighbor-joining method (39) suggested that the SIVsm isolates demonstrated a distinct cluster pattern and suggested that each of the isolates represented a natural infection in the wild prior to captivity. Additionally, the SIVstm and the African green monkey viruses in our study clustered with viruses isolated from monkeys of the same lineage (Fig. 1 and data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of SIV V3-to-V4 envelope sequences using the neighbor-joining method (39). The data indicate that the SIVsm viruses in this study were likely acquired by monkeys in the wild prior to captivity. Isolates from the present study are indicated with asterisks.

Initial experiments were performed to determine the ability of the SIV primary isolates to infect human and pigtail macaque (M. nemistrina) PBMCs. These experiments also allowed expansion of the viruses to be used in future coreceptor experiments. All isolates were capable of infecting the CCR5+/+ human PBMCs, and all but two, SIVmnd and SIVsm156, infected the pigtail macaque PBMCs (Table 1). We next examined the SIV isolates for their ability to infect cells from a human donor homozygous for a CCR5 32-bp deletion (27) to determine the absolute CCR5 requirement of the primary SIV isolates. All isolates with the exception of SIVsm21 infected the CCR5−/− human PBMCs (Table 1), suggesting that CCR5 expression was not an absolute requirement for SIV isolates and that most SIVs were capable of using other receptors.

TABLE 1.

Virus replication measured by reverse transcriptase activity

| Isolate | Origin | Reverse transcriptase activity (104 cpm/ml) in:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macaque PBMC | Human PBMC

|

|||

| CCR5+/+ | CCR5−/− | |||

| SIVstm | Stumptail macaque | 17 | 30 | 3.2 |

| SIVmnd (BK12) | Mandrill | 0 | 18 | 37.1 |

| SIV agm | African green monkey | NDa | 28 | ND |

| SIVsm3 | Sooty mangabey | 62 | 498 | 147 |

| SIVsm9 | Sooty mangabey | 85 | 238 | 107 |

| SIVsm21 | Sooty mangabey | 44 | 32 | 0 |

| SIVsm54 | Sooty mangabey | 99 | 21 | 19 |

| SIVsm55 | Sooty mangabey | 34 | 145 | 194 |

| SIVsm156 | Sooty mangabey | 0 | 940 | 186 |

ND, not determined.

To further address the issue of coreceptor use by the primary SIV isolates, we infected GHOST4 or U87 cells expressing various chemokine receptors (obtained from the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health) as previously described (37). In some experiments, infection of GHOST and U87 cells expressing CCR5 and CXCR4 was conducted in the absence or presence of SDF-1 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn.) (3.5 μg/ml), a monoclonal antibody specific for CXCR4 (clone 44717.111; R&D Systems) (2 μg/ml), and two CXCR4-antagonistic compounds, T-22 (0.3 μM) (34) and AMD3100 (200 ng/ml) (41). The compounds or antibodies were added to the cells just prior to the addition of the virus to the cells. All compounds were maintained at the same concentration throughout the duration of the cultures. The percent inhibition was calculated based on the differences in p27 levels in the absence or presence of inhibitory compound, as follows: 100 − (p27 antigen concentration with inhibitor/p27 antigen concentration without inhibitor) × 100.

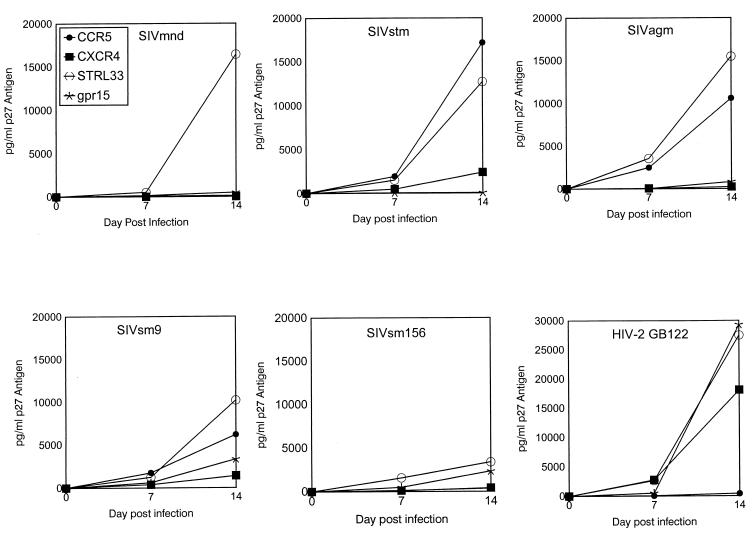

Nine SIV isolates grown in either human or pigtail macaque PBMCs along with a multiple coreceptor using a control HIV-2 isolate (GB122) were used to infect CD4+ GHOST4 cells expressing various chemokine receptors (Table 2). As expected, all SIV isolates tested could use CCR5 for entry. Likewise, the coreceptors STRL33 and GPR15, previously identified as major coreceptors for SIV strains, were used by all isolates included in our study (Table 2). Additionally, other coreceptors, such as CCR2b, CCR3, CCR5, CXC3R1, and CCR8, were used by several SIV isolates (Table 2). Interestingly, an SIVstm isolate, an SIVagm isolate, and four SIVsm isolates were capable of using the coreceptor CXCR4 for entry into GHOST4 cells (Table 2; Fig. 2). Figure 2 illustrates the time course of production of p27 antigen in the GHOST4 CCR5, CXCR4, STRL33, and GPR15 cell lines. Three of the primary SIV isolates, SIVsm3, SIVsm9, and SIVsm55, isolated from sooty mangabeys consistently produced low levels of p27 antigen in the parental GHOST4 cell line. However, in multiple experiments the levels of antigen expressed from the GHOST CXCR4 cell line were always at least 2.5-fold higher than antigen levels observed in the parental cell line (Fig. 3B).

TABLE 2.

Coreceptor utilization by primary SIV isolates in GHOST4 cell lines

| Isolate | p27 antigen (pg/ml) at day 14 postinfection

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parental | CCR1 | CCR2b | CCR3 | CCR4 | CCR5 | CXCR4 | STRL33 | GPR15 | CCR8 | CX3 CR1 | |

| SIVsm21 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 93 | 0 | 295 | 209 | 0 | 0 |

| SIVsm54 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 125 | 0 | 153 | 158 | 0 | 0 |

| SIVmnd | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 197 | 0 | 16,430 | 494 | 0 | 0 |

| SIVst | 0 | 0 | 154 | 126 | 279 | 17,181 | 1,479 | 12,720 | 54 | 0 | 603 |

| SIVsm156 | 0 | 0 | 120 | 144 | 430 | 754 | 414 | 3,380 | 2,332 | 0 | 0 |

| SIVsm9 | 50 | 138 | 121 | 314 | 1,545 | 6,190 | 1,401 | 10,200 | 3,320 | 591 | 1,400 |

| SIVsm3 | 95 | 130 | 0 | 97 | 481 | 758 | 279 | 12,727 | 311 | 0 | 94 |

| SIVsm55 | 59 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 52 | 1,711 | 145 | 358 | 398 | 0 | 0 |

| SIVagm | 31 | 460 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10,640 | 200 | 11,550 | 400 | 0 | 0 |

| HIV-2 GB122 | 0 | 0 | 1,252 | 1,022 | 0 | 493 | 19,250 | 4,220 | 9,050 | 3,025 | 2,578 |

FIG. 2.

Data shown indicate the time course of production of p27 antigen from day 0 to day 14 of culture from representative experiments of GHOST4 cell line infections with SIVmnd, SIVstm, SIVagm, and two representative SIVsm isolates (SIVsm9 and SIVsm156). These data indicate multiple coreceptor use by all SIV isolates tested. HIV-2 isolate GB122, which has been previously shown to use multiple coreceptors, was included as a control. The data are from one representative experiment. Symbols identifying a particular cell line are the same for all viruses and are shown in the SIVmnd panel.

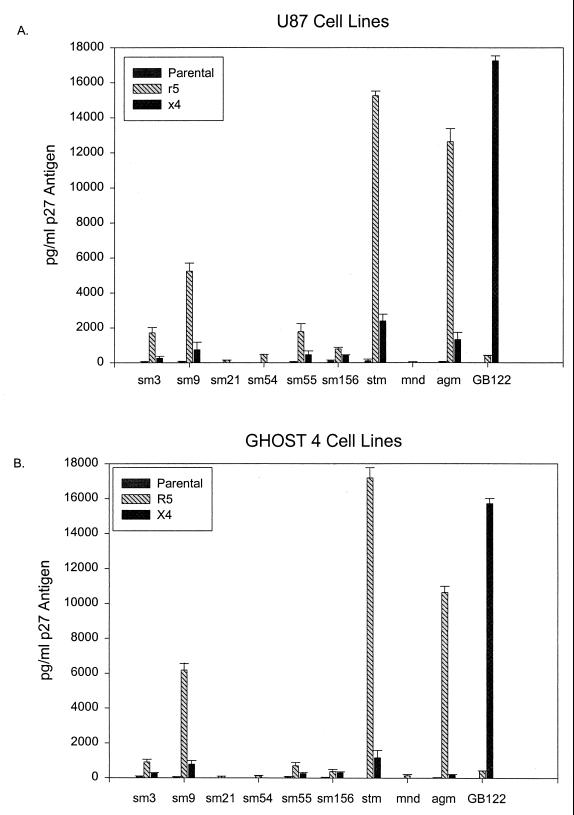

FIG. 3.

Comparison of infection in GHOST4 and U87 CD4, parental, CCR5, and CXCR4 cell lines using nine primary SIV isolates, with HIV-2 GB122 as a control. Infection levels of CCR5- and CXCR4-expressing GHOST and U87 cell lines are comparable. The data are average p27 antigen values at day 10 postinfection. A minimum of two infection experiments (duplicate cultures in each experiment) were used to calculate the mean values of p27 produced. The thin bars represent the standard errors of the means observed between multiple infection experiments.

Since the parental GHOST4 cells have low-level expression of CXCR4, we next examined the coreceptor utilization of these isolates using U87 cell lines transfected with various coreceptors. The coreceptor use identified in GHOST and U87 cells were identical for all the coreceptors tested in both cell lines (Fig. 3 and data not shown). In particular, all isolates shown to use CXCR4 in GHOST cells were also capable of using CXCR4 expressed on U87 cells (Fig. 2), further demonstrating that SIV isolates from diverse primate species can utilize CXCR4 for cell entry.

To further confirm the specificity of CXCR4 utilization, three of the SIV isolates (SIVst, SIVsm55, and SIVsm156) were used to infect the GHOST4 cells expressing CCR5 or CXCR4 in the absence or presence of SDF-1, the ligand for CXCR4 (5, 35, 44), monoclonal antibody to CXCR4 (clone 44717.111; R&D Systems), and two small-molecule antagonist compounds, T-22 and AMD3100 (34, 41). While both T-22 and AMD3100 blocked infection with HIV-1 LAI by more than 95% in multiple experiments, more-variable levels of inhibition were observed with the SIV isolates tested. For instance, SIVstm and SIVsm156 were significantly blocked by T-22 (99 and 70.3%, respectively), while no effect on SIVsm55 was observed (Table 3). Only one isolate (SIVsm156) was inhibited by AMD3100. Likewise, SDF-1 and a monoclonal antibody to CXCR4 had various degrees of inhibitory activity on the SIV isolates examined (Table 3 and data not shown). In contrast, enhancement of infection was observed with most infections of GHOST CCR5 cell lines in the presence of these CXCR4 antagonists (Table 3). Results from blocking infections conducted with the U87 cells expressing CXCR4 showed inconsistent blocking with all the compounds tested (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Infection of GHOST4 CXCR4 and CCR5 cell lines in the presence of CXCR4 antagonists

| Receptor and agent(s) | p24 antigen (pg/ml) on day 10 postinfectiona

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expt 1

|

Expt 2

|

|||||

| SIVstm | SIVsm55 | SIVsm156 | SIVstm | SIVsm55 | SIVsm156 | |

| CXCR4 | ||||||

| Virus | 222 | 95 | 206 | 320 | 439 | 263 |

| Virus + T-22 | 15 (99) | 120 | 61 (70.3) | ND | ND | ND |

| Virus + AMD3100 | 336 | 458 | 0 (100) | ND | ND | ND |

| Virus + MAb | NDb | ND | ND | 114 (64.5) | 329 (25.2) | 151 (42.3) |

| Virus + SDF-1 | ND | ND | ND | 203 (36.8) | 403 (8.2) | 272 |

| CCR5 | ||||||

| Virus | 338 | 1,208 | 637 | 1,637 | 313 | 118 |

| Virus + T-22 | 738 | 1,682 | 1,565 | ND | ND | ND |

| Virus + AMD3100 | 2,309 | 2,147 | 1,197 | ND | ND | ND |

| Virus + MAb | ND | ND | ND | 1,283 (21.6) | 408 | 109 |

| Virus + SDF-1 | ND | ND | ND | 2,500 | 637 | 110 |

Numbers in parentheses are percent inhibition. MAb is a monoclonal antibody (R&D clone 44717.111) directed against CXCR4.

ND, not determined.

To determine if specific envelope sequences within the C2V3 region of the envelope correlated coreceptor use by SIV isolates, predicted amino acid sequences derived from the sequenced PCR products were analyzed. Based on this analysis no consensus motif that would distinguish between those isolates that used only CCR5, GPR15, and STRL33 and those isolates that were capable of using CXCR4 or other coreceptors was found (data not shown).

Unlike the hypervariability of HIV-1 in this region, the V3 loop region of the SIV isolates (from the same monkey species) was highly conserved, similar to data described previously (26, 36). A similar finding for HIV-2 isolates which share close genetic homology to the SIVsm isolates has also been previously described by our laboratory (37). These data suggest that coreceptor use by SIV isolates is dependent on envelope sequences other than the V3 loop.

Previous studies have demonstrated that diverse groups of SIV, including those of both the non-syncytium-inducing macrophage-tropic and syncytium-inducing T-cell-tropic phenotypes, use CCR5 as a coreceptor for entry into human cells (7, 9, 26, 29, 30). These findings were further confirmed by the results of this study, in which all of the isolates tested were capable of using CCR5 as a coreceptor for entry. Furthermore, some SIV isolates can use CCR5 as a primary receptor and can infect CD4− CCR5+ cells, such as rhesus brain capillary endothelial cells (16). The conserved use of CCR5 by primary HIV and SIV isolates occurs despite specific changes identified in the CCR5 receptors of different primate species (40).

As previously reported for other SIV isolates (17), the SIV strains included in our study used both the coreceptors STRL33 and GPR15. Additionally, some of the isolates in the study were capable of using additional coreceptors, including CCR1, CCR2b, CCR3, CCR4, CCR5, CXCR4, CXC3R1, and CCR8. The use of CCR2b and CCR8 was not surprising, since other SIV isolates have been shown to use these coreceptors for entry (8, 38). The relevance of this multiple coreceptor use to transmissibility or pathogenesis has yet to be determined.

Interestingly, until recently no SIV isolates were found to use CXCR4, a coreceptor that plays an important role in cell entry and pathogenesis for both HIV-1 and HIV-2. In our study, we demonstrated that multiple SIV isolates, including SIVstm, SIVsm, and SIVagm, could utilize CXCR4 as a coreceptor for entry into human cells. Recently one SIV strain, SIVmnd (GB-1), was shown to use CXCR4 but not CCR5 as a coreceptor (42). It was postulated that this different coreceptor use by SIVmnd (GB-1) might be explained by the lack of sequence homology in the Env protein of SIVmnd and other groups of primate lentiviruses. In this study we demonstrated that additional primary SIV isolates, including four SIVsm, one SIVst, and one SIVagm isolate, were capable of using CXCR4 as a coreceptor. These conclusions are based on experiments conducted with two separate cell lines expressing the CXCR4 coreceptor (GHOST4 and U87). Also, we demonstrated that the mandrill isolate was not capable of using CXCR4 as a coreceptor. These data suggests that species of origin of SIV isolates does not necessarily correlate with a specific coreceptor requirement.

The SIVagm isolate and three of the SIVsm isolates (SIVsm3, SIVsm9, and SIVsm55) that were capable of using CXCR4 demonstrated low levels of replication in the parental cell lines (GHOST4 and U87). However, in all cases the p27 antigen levels produced in the CXCR4 cell lines were higher than those produced in the parental cell lines. The low level of virus expression in the parental GHOST cell line is most likely due to the low levels of CXCR4 expressed on the GHOST4 cells and thus further supports the use of CXCR4 as a coreceptor for the SIV isolates. Likewise, low levels of STRL33 expression on the U87 cell line may explain the limited p27 antigen production by some isolates in the U87 parental cell line.

The specificity of CXCR4 utilization was further addressed by SIV blocking experiments with GHOST CXCR4 and GHOST CCR5 cell lines. The addition of SDF-1, antagonistic compounds AMD3100 and T-22, or a monoclonal antibody raised against CXCR4 inhibited to various degrees the CXCR4 entry of the SIV isolates into GHOST cells (Table 3). One possibility for the variable efficiency of these compounds in blocking SIV infection in GHOST4 cells (compared to HIV-1 isolates in the same cell lines) could be that the SIV Env interaction with CXCR4 is different than the interaction between envelopes of HIV-1 and CXCR4. For example, the envelopes of the SIV isolates described in this study may interact with regions of the CXCR4 molecule other than the domains required for SDF-1, antagonist, or antibody binding. Recent data by Doranz et al. (13) indicate that the interaction between CXCR4 and HIV-1 involves complex conformational epitopes and that utilization of CXCR4 by HIV-1 is independent of the ability of CXCR4 to signal or bind SDF-1. Additionally, it has been shown that the ability of SDF-1 to block HIV-1 coreceptor utilization is variable and is often dependent on the particular HIV-1 Env protein used (44). Likewise, SIV interactions with the coreceptor that involve complex conformational epitopes could likely differ between SIV isolates. Indeed, recent studies that demonstrate CD4 independent usage of chemokine receptors by HIV and SIV isolates have suggested that the envelope glycoproteins of HIV-2 and SIV form a conformation subtly different from that of HIV-1 (18, 38).

We were not able to consistently block the entry of SIV isolates in the U87 CXCR4 cell line. Lack of inhibition in these cells could be due to the fact that the U87 line has a low level of STRL33 expression; thus, the infection of these cells in the presence of the CXCR4 antagonistic compounds might be mediated through STRL33. It is also not known how these antagonistic compounds might affect the levels of STRL33 contained on the U87 cells. It is conceivable that the presence of the CXCR4 antagonistic compounds could increase the expression of STRL33. Recent data by Lee et al. (B. Lee, M. Sharron, S. Pohlmann, K. Price, M. Tang, F. Kirchhoff, and R. W. Doms, 7th Int. Conf. Retrovir. Opportunistic Infect., poster 147, 2000) demonstrated cell surface expression of STRL33 on PBMCs and showed that this coreceptor can be used by SIV isolates to infect PBMCs. Future experiments using the STRL33 antibody described in this work are planned to address the issue of modulation of STRL33 expression by CXCR4 antagonists.

Another intriguing finding in this study was the apparent enhancement of viral replication in the CCR5 cell lines in the presence of either the CXCR4 ligand, the monoclonal antibody, or the antagonistic compounds. The mechanism for this enhancement is unknown but could involve the ability of these compounds to induce an activation signal in the CCR5 cells. Alternatively, as has been proposed for STRL33, the presence of the antagonistic compounds could affect the cell surface expression of CCR5 and thus affect virus entry and production in the CCR5 cells. The phenomenon should be further studied due to its important implications for using chemokine receptor blocking agents as therapeutic targets.

Two of the isolates that were used in this study, SIVsm21 and SIVsm54, showed poor replication in both human PBMCs (low reverse transcriptase counts) and the GHOST4 and U87 cell lines (low antigen values). In general, all of the SIVsm isolates had lower levels of replication in the GHOST and U97 cells than the SIVstm and SIVagm isolates. The reason for the low but consistent levels of viral replication is unknown. However, one hypothesis is that these viruses are not capable of high levels of virus production in human PBMCs or cell lines because of other viral genes that are important for replication at stages subsequent to viral entry.

It is clear that coreceptor use for SIV is as complex as has been demonstrated for HIV-1 and HIV-2. However, information concerning the genetic determinants for coreceptor use by SIV strains is still poorly understood. In the present study, analysis of the V3 region from the SIV isolates did not reveal any distinct sequences that could be associated with CXCR4 usage. In fact, unlike in HIV-1, this region was well conserved among SIV isolates from the same monkey species. Previously this conservation in the V3 loop was demonstrated for a series of primary HIV-2 isolates (37) as well as other SIV isolates (36). The relative conservation of the V3 region of gp120 and gp125 suggests that envelope regions other than V3 may play important roles in determining coreceptor use by SIV and HIV-2 isolates. Further sequence analysis of other envelope regions is needed to identify the viral sequences important in SIV and HIV-2 coreceptor utilization. Identification of the viral gene sequences that are important for SIV coreceptor use may lead to a better understanding of the protein structures that are important for the entry of all primate lentiviruses, including HIV-1 and HIV-2, into susceptible hosts.

Acknowledgments

We thank Feng Gao for performing the phylogenetic analysis and Christopher Miller for helping with the SIVagm isolate. We also thank Dominique Schols for providing AMD3100 and N. Yamamoto for providing T-22. The GHOST and U87 cell lines were obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH, from Vineet N. KewalRamani, Hong Kui Deng, and Dan R. Littman.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albert J, Stalhandske P, Marquina S, Karis J, Fouchier R A, Norby E, Chiodi F. Biological phenotype of HIV type 2 isolates correlates with V3 genotype. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1996;12:821–828. doi: 10.1089/aid.1996.12.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alkhatib G, Combadiere C, Broder C C, Feng Y, Kennedy P E, Murphy P M, Berger E A. CC CKR5: a RANTES, MIP-1alpha, MIP-1beta receptor as a fusion cofactor for macrophage-tropic HIV-1. Science. 1996;272:1955–1958. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5270.1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bazan H A, Alkhatib G, Broder C C, Berger E A. Patterns of CCR5, CXCR4, and CCR3 usage by envelope glycoproteins from human immunodeficiency virus type 1 primary isolates. J Virol. 1998;72:4485–4491. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4485-4491.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berger E A, Murphy P M, Faber J M. Chemokine receptors as HIV-1 coreceptors: roles in viral entry, tropism, and disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:657–700. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bleul C C, Farzan M, Choe H, Parolin C, Clark-Lewis I, Sodroski J, Springer T A. The lymphocyte chemoattractant SDF-1 is a ligand for LESTR/fusin and blocks HIV-1 entry. Nature. 1996;382:829–832. doi: 10.1038/382829a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bron R, Klasse P J, Wilkinson D, Clapham P R, Pelchen-Matthews A, Power C, Wells T N, Kim J, Peiper S C, Hoxie J A, Marsh M. Promiscuous use of CC and CXC chemokine receptors in cell-to-cell fusion mediated by a human immunodeficiency virus type 2 envelope protein. J Virol. 1997;71:8405–8415. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8405-8415.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Z, Zhou P, Ho D D, Landau N R, Marx P A. Genetically divergent strains of simian immunodeficiency virus use CCR5 as a coreceptor for entry. J Virol. 1997;71:2705–2714. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.2705-2714.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Z, Kwon D, Jin Z, Monard S, Telfer P, Jones M S, Lu C Y, Aguilar R F, Ho D D, Marx P A. Natural infection of a homozygous delta24 CCR5 red-capped mangabey with an R2b-tropic simian immunodeficiency virus. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2057–2065. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.11.2057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Z, Gettie A, Ho D D, Marx P A. Primary SIVsm isolates use the CCR5 coreceptor from sooty mangabeys naturally infected in west Africa: a comparison of coreceptor usage of primary SIVsm, HIV-2, and SIVmac. Virology. 1998;246:113–124. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Connor R I, Sheridan K E, Ceradidni D, Choe S, Landau N R. Change in coreceptor use correlates with disease progression in HIV-1 infected individuals. J Exp Med. 1997;185:621–628. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.4.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deng H, Liu R, Ellmeier W, Choe S, Unutmaz D, Burkhart M, Di Marzio P, Marmon S, Sutton R E, Hill C M, Davis C B, Peiper S C, Schall T J, Littman D R, Landau N R. Identification of a major co-receptor for primary isolates of HIV-1. Nature. 1996;381:661–666. doi: 10.1038/381661a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deng H K, Unutmaz D, KewalRamani V N, Littman D R. Expression cloning of new receptors used by simian and human immunodeficiency viruses. Nature. 1997;388:296–300. doi: 10.1038/40894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doranz J, Orsini M J, Turner J D, Hoffman T L, Berson J F, Hoxie J A, Peiper S C, Brass L F, Doms R W. Identification of CXCR4 domains that support coreceptor and chemokine receptor function. J Virol. 1999;73:2752–2761. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.2752-2761.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dragic T, Litwin V, Allaway G P, Martin S R, Huang Y, Nagashima K A, Cayanan C, Maddon P J, Koup R A, Moore J P, Paxton W A. HIV-1 entry into CD4+ cells is mediated by the chemokine receptor CC-CKR-5. Nature. 1996;381:667–673. doi: 10.1038/381667a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edinger A L, Amedee A, Miller K, Doranz B J, Endres M, Sharron M, Samson M, Lu Z H, Clements J E, Murphey-Corb M, Peiper S C, Parmentier M, Broder C C, Doms R W. Differential utilization of CCR5 by macrophage and T cell tropic simian immunodeficiency virus strains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4005–4010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.4005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edinger A L, Mankowski J L, Doranz B J, Margulies B J, Lee B, Rucker J, Sharron M, Hoffman T L, Berson J F, Zink M C, Hirsch V M, Clements J E, Doms R W. CD4-independent, CCR5-dependent infection of brain capillary endothelial cells by a neurovirulent simian immunodeficiency virus strain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14742–14747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edinger A L, Hoffman T L, Sharron M, Lee B, O'Dowd B, Doms R W. Use of GPR1, GPR15, and STRL33 as coreceptors by diverse human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and simian immunodeficiency virus envelope proteins. Virology. 1998;249:367–378. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edinger A L, Blanpain C, Kinstman K J, Wolinsky S M, Parmentier M, Doms R W. Functional dissection of CCR5 coreceptor function through the use of CD4-independent simian immunodeficiency virus strains. J Virol. 1999;73:4062–4073. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.4062-4073.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farzan M, Choe H, Martin K, Marcon L, Hofmann W, Karlsson G, Sun Y, Barrett P, Marchand N, Sullivan N, Gerard N, Gerard C, Sodroski J. Two orphan seven-transmembrane segment receptors which are expressed in CD4-positive cells support simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J Exp Med. 1997;186:405–411. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.3.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feng Y, Broder C C, Kennedy P E, Berger E A. HIV-1 entry cofactor: functional cloning of a seven-transmembrane, G protein coupled receptor. Science. 1996;272:872–877. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5263.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao F, Yue L, White A T, Pappas P G, Barchue J, Hanson A P, Greene B M, Sharp P M, Shaw G M, Hahn B H. Human infection by genetically diverse SIVSM-related HIV-2 in west Africa. Nature. 1992;358:495–499. doi: 10.1038/358495a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao F, Bailes E, Robertson D L, Chen Y, Rodenburg C M, Michaels S C, Cummins L B, Arthur L O, Peeters M, Shaw G M, Sharp P M, Hahn B H. Origin of HIV-1 in the chimpanzee Pan troglodytes troglodytes. Nature. 1999;397:436–439. doi: 10.1038/17130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guillon C, van der Ende M E, Boers P H, Gruters R A, Schutten M, Osterhaus A D. Coreceptor usage of human immunodeficiency virus type 2 primary isolates and biological clones is broad and does not correlate with their syncytium-inducing capacities. J Virol. 1998;72:6260–6263. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.6260-6263.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hill C M, Deng H, Unutmaz D, Kewalramani V N, Bastiani L, Gorny M K, Zolla-Pazner S, Littman D R. Envelope glycoproteins from human immunodeficiency virus types 1 and 2 and simian immunodeficiency virus can use human CCR5 as a coreceptor for viral entry and make direct CD4-dependent interactions with this chemokine receptor. J Virol. 1997;71:6296–6304. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6296-6304.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson P R, Hamm T E, Goldstein S, Kitov S, Hirsch V M. The genetic fate of molecularly cloned simian immunodeficiency virus in experimentally infected macaques. Virology. 1991;185:217–228. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90769-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirchhoff F, Pohlmann S, Hamacher M, Means R E, Kraus T, Uberla K, Di Marzio P. Simian immunodeficiency virus variants with differential T-cell and macrophage tropism use CCR5 and an unidentified cofactor expressed in CEMx174 cells for efficient entry. J Virol. 1997;71:6509–6516. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6509-6516.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liao F, Alkhatib G, Peden K W, Sharma G, Berger E A, Farber J M. STRL33, a novel chemokine receptor-like protein, functions as a fusion cofactor for both macrophage-tropic and T cell line-tropic HIV-1. J Exp Med. 1997;185:2015–2023. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.11.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu R, Oaxton W A, Choe S, Ceradini D, Martin S R, Horuk R, McDonald M E, Stuhlmann H, Koup R A, Landau N R. Homozygous defect in HIV-1 coreceptor accounts for resistance of some multiply-exposed individuals to HIV-1 infection. Cell. 1996;86:367–377. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marcon L, Choe H, Martin K A, Farzan M, Ponath P D, Wu L, Newman W, Gerard N, Gerard C, Sodroski J. Utilization of C-C chemokine receptor 5 by the envelope glycoproteins of a pathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus, SIVmac239. J Virol. 1997;71:2522–2527. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.2522-2527.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marx P A, Chen Z. The function of simian chemokine receptors in the replication of SIV. Semin Immunol. 1998;10:215–223. doi: 10.1006/smim.1998.0135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marx P A. Simian immunodeficiency viruses: their biology, origin and evolution. In: Saksena N, editor. Human immunodeficiency viruses. Biology, immunology and molecular biology. Genoa, Italy: Medical Systems S.P.A.; 1998. pp. 413–438. [Google Scholar]

- 32.McKnight A, Dittmar M T, Moniz-Periera J, Ariyoshi K, Reeves J D, Hibbitts S, Whitby D, Aarons E, Proudfoot A E, Whittle H, Clapham P R. A broad range of chemokine receptors are used by primary isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 2 as coreceptors with CD4. J Virol. 1998;72:4065–4071. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4065-4071.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Müller M C, Saksena N K, Nerrienet E, Chappey C, Hervé V M A, Durand J-P, Legal-Campodonico P, Lang M-C, Digoutte J-P, Georges A J, Georges-Courbot M-C, Sonigo P, Barré-Sinoussi F. Simian immunodeficiency viruses from central and west Africa: evidence for a new species-specific lentivirus in tantalus monkeys. J Virol. 1993;67:1227–1235. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.3.1227-1235.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murakami T, Nakajima T, Koyanagi Y, Tachibana K, Fujii N, Tamamura H, Yoshida N, Waki M, Matumoto A, Yoshie O, Kishimoto T, Yamamoto N, Nagasawa T. A small molecule CXCR4 inhibitor that blocks T-cell line–tropic HIV-1 infection. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1389–1393. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.8.1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oberlin E, Amara A, Bachelerie F, Bessia C, Virelizer J L, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Schwartz O, Heard J M, Clark-Lewis I, Legler D F, Loetscher M, Baggiolini M, Moser B. The CXC chemokine SDF-1 is the ligand for LESTR/fusin and prevents infection by T-cell-line-adapted HIV-1. Nature. 1996;382:833–835. doi: 10.1038/382833a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Overbaugh J, Rudensey L M, Papenhausen M D, Benveniste R E, Morton W R. Variation in simian immunodeficiency virus env is confined to V1 and V4 during progression to simian AIDS. J Virol. 1991;65:7025–7031. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.12.7025-7031.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Owen S M, Ellenberger D, Rayfield M, Wiktor S, Michel P, Grieco M H, Gao F, Hahn B H, Lal R B. Genetically divergent strains of human immunodeficiency virus type 2 use multiple coreceptors for viral entry. J Virol. 1998;72:5425–5432. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.5425-5432.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reeves J D, Hibbitts S, Simmons G, McKnight A, Azevedo-Pereira J M, Moniz-Pereira J, Clapham P R. Primary human immunodeficiency virus type 2 (HIV-2) isolates infect CD4-negative cells via CCR5 and CXCR4: comparison with HIV-1 and simian immunodeficiency virus and relevance to cell tropism in vitro. J Virol. 1999;73:7795–7804. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.9.7795-7804.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saksena N K, Wang B, Novembre F J, Bolton W, Smit T K, Lal R B. Species-specific changes in the CCR5 gene from African and Asian nonhuman primates. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1999;15:479–483. doi: 10.1089/088922299311231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schols D, Struyf S, Van Damme J, Este J A, Henson G, De Clercq E. Inhibition of T-tropic HIV-1 strains by selective antagonization of the chemokine receptor CXCR4. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1383–1388. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.8.1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schols D, De Clercq E. The simian immunodeficiency virus mnd(GB-1) strain uses CXCR4, not CCR5, as coreceptor for entry in human cells. J Gen Virol. 1998;79:2203–2205. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-9-2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sol N, Ferchal F, Braun J, Pleskoff O, Treboute C, Ansart I, Alizon M. Usage of the coreceptors CCR-5, CCR-3, and CXCR-4 by primary and cell line-adapted human immunodeficiency virus type 2. J Virol. 1997;71:8237–8244. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8237-8244.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trkola A, Paxton W A, Monard S P, Hoxie J A, Siani M A, Thompson D A, Wu L, Mackay C R, Horuk R, Moore J P. Genetic subtype-independent inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication by CC and CXC chemokines. J Virol. 1998;72:396–404. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.396-404.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xiao L, Owen S M, Goldman I, Lal A A, deJong J J, Goudsmit J, Lal R B. CCR-5 coreceptor usage of NSI HIV-1 isolates is independent of phylogenetically distinct isolates. Virology. 1998;240:83–92. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xiao L, Rudolph D, Owen S M, Spira T, Lal R B. Adaptation to promiscuous usage of CC and CXC chemokine coreceptors in vivo correlates with HIV-1 disease progression, whereas exclusive usage of CCR5 correlates with non-progression. AIDS. 1998;12:F137–F143. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199813000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang Y J, Dragic T, Cao Y, Kostrikis L, Kwon D S, Littman D R, Kewal Ramani V N, Moore J P. Use of coreceptors other than CCR5 by non-syncytium-inducing adult and pediatric isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is rare in vitro. J Virol. 1998;72:9337–9344. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.9337-9344.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]