B cells have a previously unrecognized helper function in triggering pathogenic differentiation of inflammatory TH subsets.

Abstract

B cells constitute abundant cellular components in inflamed human tissues, but their role in pathogenesis of inflammatory T helper (TH) subsets is still unclear. Here, we demonstrate that B cells, particularly resting naïve B cells, have a previously unrecognized helper function that is involved in shaping the metabolic process and subsequent inflammatory differentiation of T-cell receptor–primed TH cells. ICOS/ICOSL axis–mediated glucose incorporation and utilization were crucial for inflammatory TH subset induction by B cells, and activation of mTOR was critical for T cell glycolysis in this process. Consistently, upon encountering ICOSL+ B cells, activated effector memory TH cells from patients with rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus spontaneously differentiated into inflammatory TH subsets. Immunotherapy using rituximab that specifically depleted B cells in patients with rheumatoid arthritis efficiently abrogated the capabilities of memory TH cells to incorporate and use glucose, thereby impairing the pathogenic differentiation of inflammatory TH subsets.

INTRODUCTION

B cells are lymphocytes that, along with T cells, constitute the adaptive immune system (1–4). Once they are activated, mature B cells can produce antibodies that provide a specifically targeted response to infection or malignancy (5, 6). Nevertheless, in antibody-dependent pathways, B cells also trigger pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases (7, 8). In addition to secreting antibodies, B cells are dominant antigen-presenting cells (APCs) that initiate specific T helper (TH) cell responses during immunization with inactivated influenza virus (9). It should be emphasized that B cells are found not only in lymphoid organs but also in inflamed regions in a tissue, which represent the main site of inflammatory TH subsets (10, 11). To date, direct evidence is lacking to support a role for B cells in the immunopathogenesis of inflammatory TH subsets. Furthermore, a related issue that must be addressed in this context is whether the nature and activation status of B cells control the ability of those cells to polarize inflammatory TH cells, and, if so, how the B cells exert that effect.

Inflammatory TH subset differentiation is controlled by networks comprising both extrinsic and intrinsic factors (12, 13). Metabolic processes are now considered to represent a key regulator of T cell functional specification and fate, and hence, modulation of those processes can differentially influence development of TH subsets (14, 15). It is known that effector and inflammatory TH subsets require glycolysis, whereas memory and regulatory T cells depend on oxidative phosphorylation and fatty acid metabolism (16, 17). In parallel, excessive up-regulation of glucose uptake in TH cells by transfection of Glut1 leads to increased cytokine production and proliferation and, ultimately, to inflammatory diseases (18). Thus, to understand the differentiation and functional status of TH subsets in immunopathogenesis, it is essential to evaluate the metabolic processes of TH subsets under pathological conditions. Inasmuch as B cells are the APCs that most often cooperate with TH cells (19, 20), it is vital to determine whether and, if so, how B cells orchestrate metabolic processes of TH cells in pathological tissues.

Memory T cells are the most important cellular component in the protection against secondary infection (21), but knowledge is limited regarding the pathological roles of these cells in maintaining inflammation or with respect to the mechanisms involved in regulating that process. Here, we identify a direct helper function of B cells, particularly resting naïve B cells, in generating inflammatory TH subsets from memory T cells undergoing T cell receptor (TCR) triggering. ICOS (inducible T-cell costimulator)/ICOSL axis–elicited sequential mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) activation, increased glucose uptake, and enhanced glycolysis are essential for B cell–mediated generation of inflammatory TH subsets. Correspondingly, when activated effector memory TH cells from patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) or systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) encounter ICOSL+ B cells, without TCR triggering, they spontaneously differentiate into inflammatory TH subsets. In RA patients, immunotherapy using an anti-CD20 antibody (rituximab) that specifically depletes B cells effectively abrogates the capabilities of TH cells to incorporate and use glucose, impairs the inflammatory differentiation of TH cells, and suppresses disease progression.

RESULTS

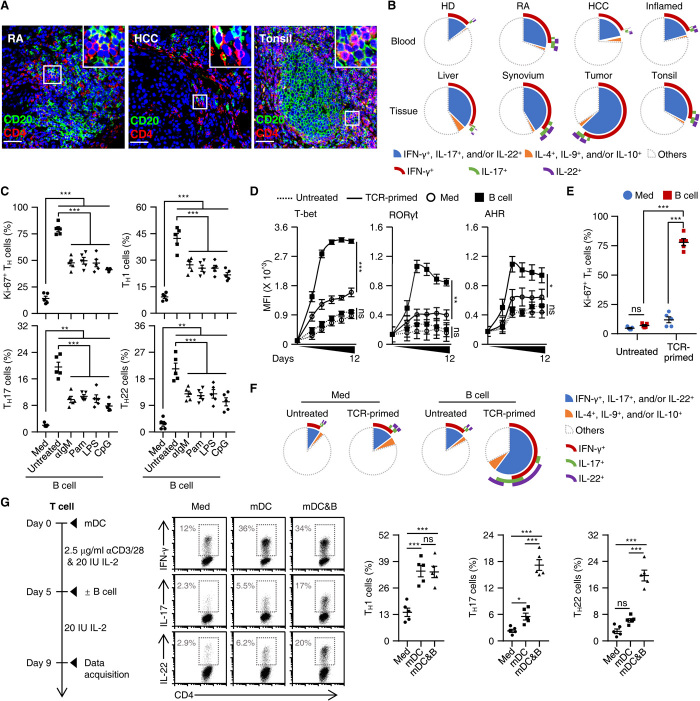

Identifying helper functions of B cells in generation of inflammatory TH subsets

APCs are critical for initiating and maintaining the TH responses. In pathological RA, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and inflamed tonsil tissues (n = 8, 11, and 11, respectively), B cells were the APCs that were most often in contact with TH cells (Fig. 1A and fig. S1A). Also, in such tissues, increased proportions of TH cells exhibited polyfunctional features coexpressing inflammatory interferon-γ (IFN-γ), interleukin-17 (IL-17), and/or IL-22 (Fig. 1B and fig. S1B). In contrast, anti-inflammatory TH subsets related to IL-4, IL-9, or IL-10 were rarely detected (Fig. 1B and fig. S1B). These data raise an important and previously unrecognized question: Can B cells directly polarize inflammatory TH subsets under pathological conditions? To address this, we explored conditions under which the process could be reliably induced. We used freshly isolated blood B cells as well as their activated counterparts. B cell activation was induced by an anti–immunoglobulin M (IgM) [B cell receptor (BCR)–triggering] antibody, Pam3CysSK4 [a Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) agonist], lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (a TLR4 agonist), or CpG-DNA oligodeoxynucleotide (ODN) (a TLR9 agonist), that is, not by poly(I:C) (a TLR3 agonist), as assessed by determining CD69 up-regulation and B and T lymphocyte attenuator (BTLA) down-regulation (fig. S1C).

Fig. 1. Identifying helper functions of B cells in generation of inflammatory TH subsets.

(A) Confocal microscopy analysis of expression of CD4 (red, TH cells) and CD20 (green, B cells) in samples from RA synovial tissue (n = 8), HCC tissue (n = 11), and inflamed tonsils (n = 11). Scale bars, 50 μm. (B) FACS analysis of IFN-γ, IL-17, IL-22, IL-4, IL-9, and IL-10 in TH cells from paired blood and tissue samples from healthy donors (HD) and patients with RA, HCC, or inflamed tonsils (each n = 5). (C) Purified total B cells were left untreated or were stimulated with an anti-IgM antibody (αIgM), Pam3CysSK4 (Pam), LPS, or CpG-DNA ODN (CpG) for 18 hours and then cultured with autologous T cells for 9 days. Expression of Ki-67 and indicated cytokines in TH cells were detected by FACS (n = 5). (D to F) Purified T cells were cultured in medium or with autologous total B cells for 9 days (E and F) or indicated times (D) in the presence or absence of TCR triggering, as described in Materials and Methods. Expression of indicated transcription factors (D), Ki-67 (E), and inflammatory cytokines (F) in TH cells was detected by FACS (n = 5). MFI, mean fluorescence intensity. (G) Purified T cells were cultured in medium or with mature myeloid dendritic cells (mDCs) in the presence or absence of total B cells as described in workflow. FACS analysis was performed to illustrate expression of IFN-γ, IL-17, and IL-22 in TH cells (n = 5). Data are presented as means ± SEM of four independent experiments (C to E and G). ns, nonsignificant. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 [one-way ANOVA test for (C), (D), and (G); two-way ANOVA test for (E)].

In subsequent experiments, autologous TH cells were incubated with B cells or such cells stimulated with an anti-IgM antibody, Pam3CysSK4, LPS, or CpG-DNA ODN, and this was done in the absence or presence of CD3–cross-linking antibodies. We measured T cell proliferation and production of IFN-γ, IL-17, and IL-22 by these cells on day 9 after incubation with IL-2. Unexpectedly, all B cells actively promoted proliferation and differentiation of the TCR-primed TH cells (Fig. 1C and fig. S1D). More notably, the resting B cells, but not their activated counterparts, showed the greatest potential to generate functional inflammatory TH subsets expressing IFN-γ, IL-17, and/or IL-22 (Fig. 1C and fig. S1, D and E), which is in contrast to the general view that activated APCs are essential in triggering specific TH responses (22–26). Measuring lineage-specifying transcription factors over time revealed rapid up-regulation of T-bet, RORγt, and AHR, respectively, in TCR-primed TH cells incubated with B cells, and this increase reached a plateau within 5 days (Fig. 1D and fig. S1F). B cells also elicited transient generation of CXCR5+ T follicular helper (Tfh) cells: Coculture of autologous B cells and CXCR5− TH cells resulted in a rapid occurrence of CXCR5+ Tfh cells, and this process reached a maximum on day 3 and subsequently declined (fig. S1G). In contrast, in no cases did B cells have any distinct effect on production of IL-4, IL-9, or IL-10 by TCR-primed TH cells (fig. S1D). Notably, without TCR triggering, TH cells incubated with B cells did not proliferate or differentiate (Fig. 1, D to F). In addition, exposing TCR-primed TH cells to mature myeloid dendritic cells (mDCs) also generated TH1 cells at levels comparable to those induced by B cells, but this process only weakly triggered TH17 and TH22 (Fig. 1G). Also, in such a system, subsequent addition of B cells successfully endowed mDC-induced TH1 cells with increased capacity to produce IL-17 and/or IL-22 (Fig. 1G). Together, these data reveal a previously unrecognized helper role of B cells in generating inflammatory TH subsets after TCR engagement.

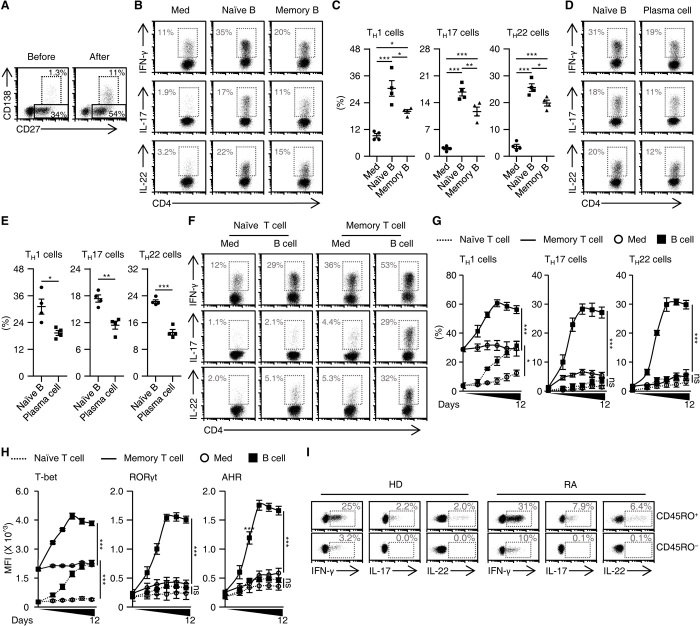

Naïve B cells are more potent B cell subpopulations in triggering memory inflammatory TH subsets

Considering the fact that exposing of B cells to TCR-primed TH cells could lead to generation of memory B cells and plasma cells (Fig. 2A), we afterward compared the capabilities of B cell subpopulations to trigger inflammatory TH subsets. To achieve that goal, we used fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to purify naïve and memory B cells (fig. S2A) and unexpectedly found that naïve B cells were significantly superior to memory B cells in inducing IFN-γ+, IL-17+, and/or IL-22+ TH cell subsets (Fig. 2, B and C). We subsequently compared the capabilities of naïve B cells and effector B cells (also termed plasma cells) (fig. S2B) to trigger inflammatory TH subsets. Analogously, naïve B cells also had a greater capacity to generate inflammatory TH cell subsets (Fig. 2, D and E). Thus, these observations reveal that, although most B cell subpopulations contribute to inflammatory polarization of TH subsets, naïve B cells are more potent in that process.

Fig. 2. Naïve B cells are more potent B cell subpopulations in triggering memory inflammatory TH subsets.

(A) Purified total B cells were cultured with T cells for 7 days in the presence of TCR triggering. The differentiation of B cells before and after coculture was analyzed by FACS (n = 3). (B to E) Purified T cells were cultured in medium or with naïve or memory B cells (B and C), or with naïve B cells or plasma cells (D and E) for 7 days as described in Materials and Methods. Expression of IFN-γ, IL-17, and IL-22 in TH cells was detected by FACS (each n = 4). (F to H) Purified naïve or memory T cells were cultured in medium or with autologous total B cells for 7 days (F) or indicated times (G and H), as described in Materials and Methods. Expression of inflammatory cytokines (F and G) and transcription factors (H) in CD4+ T cells was detected by FACS (n = 4 for each). (I) FACS analysis of IFN-γ, IL-17, and IL-22 in naïve (CD45RO−) or memory (CD45RO+) TH cells from blood of healthy donors and RA patients (each n = 3). Data are presented as means ± SEM of four independent experiments (C, E, G, and H). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 [one-way ANOVA test for (C), (G), and (H); unpaired Student’s t test for (E)].

We subsequently probed functions of B cells in generating inflammatory TH cell subsets from naïve or memory CD4+ T cells (fig. S2C). We found that B cells rapidly and effectively triggered production of IFN-γ+, IL-17+, and/or IL-22+ TH subsets from memory CD4+ T cells, which reached a plateau within 7 days (Fig. 2, F and G). By comparison, CD4+ naïve T cells primed by B cells gave rise to only moderate production of IFN-γ+ TH cells, and this effect required an additional induction process (Fig. 2, F and G). In support of these findings, expression of T-bet, RORγt, and AHR was rapidly and clearly up-regulated in B cell–primed memory CD4+ T cells, whereas there was only a gradual increase in expression of T-bet in B cell–primed naïve CD4+ T cells (Fig. 2H and fig. S2D). In addition, analysis of cytokine expression in naïve/memory (CD45RO−/CD45RO+) TH subsets revealed that IFN-γ could be detected in both naïve and memory CD4+ T cells from blood samples obtained from healthy donors or patients with RA (Fig. 2I). In support of those observations, inflammatory IL-17 and IL-22 were selectively expressed by memory CD4+ T cells (Fig. 2I). These results indicate that naïve B cells are the most potent B cells generating memory inflammatory TH subsets.

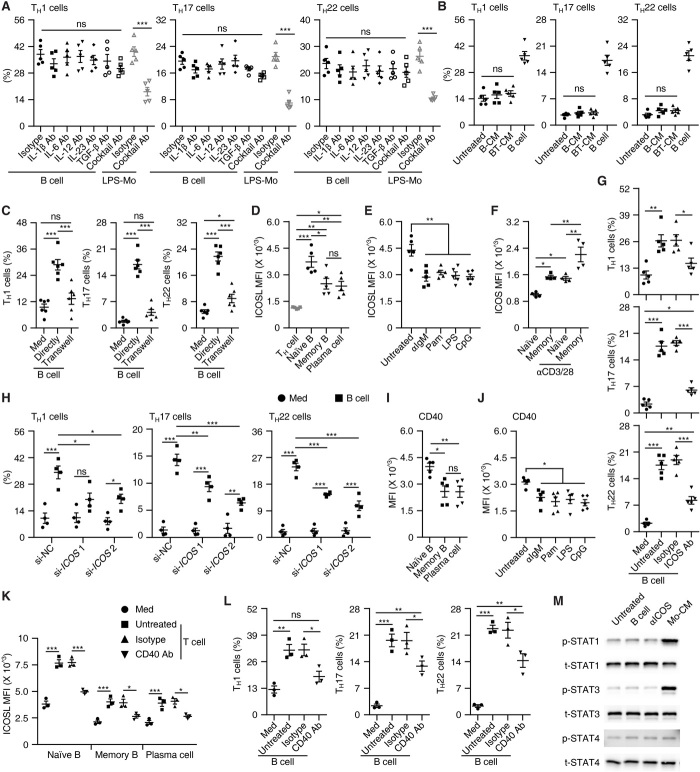

Factors that are required for B cell–elicited polarization of inflammatory TH subsets

It is noteworthy that inflammatory mediators released by APCs are critical for inflammatory TH subset polarization (12, 27), and research has shown that, among these mediators, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, IL-23, and/or transforming growth factor–β (TGF-β) participate in the induction of TH1, TH17, or TH22 (22, 27, 28). Nevertheless, we found that the neutralizing cytokines mentioned above, separately or together, barely influenced the B cell–elicited inflammatory TH subset polarization, although such treatments did impair the effects of LPS-activated monocytes (Fig. 3A and fig. S3A). Likewise, in our coculture system of autologous B cells and T cells, we detected almost no IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, IL-23, or TGF-β (fig. S3B), which suggested involvement of unrecognized inflammatory mediators that contribute to B cell–elicited TH subset polarization. However, this assumption was rapidly refuted by the further observation that conditioned medium from culture of B cells alone or together with T cells did not enable generation of inflammatory TH subsets (Fig. 3B). Ultimately, we found that when TH cells were cultured indirectly with B cells in different chambers, generation of inflammatory TH subsets was completely abrogated (Fig. 3C and fig. S3C). Thus, cell-cell contact is crucial for B cell–mediated inflammatory TH subset differentiation.

Fig. 3. Factors required for B cell–elicited polarization of inflammatory TH subsets.

(A) Neutralizing indicated cytokines separately or together hardly affected B cell–mediated TH subset differentiation on day 7. (B) Effects of total B cells or conditioned medium from the culture of total B cells (B-CM) or of total B cells plus T cells (BT-CM) on TH subset differentiation on day 7. (C) Analysis of TH subsets after cultured for 7 days in medium or with total B cells directly or in a transwell chamber. (D and E) FACS analysis of ICOSL in indicated cells from blood of healthy donors (D) or in total B cells left untreated or stimulated with αIgM, Pam3CysSK4, LPS, or CpG for 18 hours (E). (F) FACS analysis of ICOS in indicated cells left untreated or stimulated with CD3–cross-linking antibodies for 24 hours. (G and H) Blocking (G) or silencing (H) ICOS in T cells abrogated B cell–mediated TH subset differentiation on day 7. (I and J) FACS analysis of CD40 in indicated cells from blood of healthy donors (I) or in total B cells left untreated or stimulated with αIgM, Pam3CysSK4, LPS, or CpG for 18 hours (J). (K) FACS analysis of ICOSL in indicated cells cultured for 18 hours in medium or with TCR-primed TH cells in the presence or absence of CD40-neutralizing antibody. (L) Blocking CD40 abrogated B cell–mediated TH subset differentiation on day 7. (M) Analysis of STAT activation in TH cells cultured alone or stimulated with total B cells, ICOS agonist, or conditioned medium from LPS-stimulated monocytes for 2 days (n = 3). Data are presented as means ± SEM (A to L). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 [one-way ANOVA test for (A) to (G) and (I) to (L); two-way ANOVA test for (H)].

It has been demonstrated that ICOS signaling instructs Tfh differentiation in germinal centers (29). In general, we noted that ICOSL was substantially expressed by all B cell populations (Fig. 3D), and that the ICOSL intensities were much higher on naïve B cells than on memory B cells and plasma cells (Fig. 3D). Moreover, a remarkable reduction in ICOSL occurred on B cells after BCR triggering or exposure to a TLR agonist (Fig. 3E). In parallel, we found significantly higher expression of ICOS on memory TH cells than on naïve TH cells (Fig. 3F). Also, ICOS was markedly up-regulated on both memory and naïve TH cells after TCR triggering, although the up-regulation was more pronounced on memory T cells (Fig. 3F). These data indicate that the ICOSL/ICOS axis may be responsible for B cell–elicited inflammatory TH subset differentiation. To address this question, we used an antibody to specifically shield the ICOS receptor on T cells and found that such treatment successfully abrogated the inflammatory TH subset differentiation induced by B cells (Fig. 3G and fig. S3D). Consistent with this, transfecting TH cells with small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) for ICOS (fig. S3, E and F) also effectively suppressed B cell–elicited inflammatory TH subset differentiation (Fig. 3H and fig. S3G).

It has been shown that CD40/CD40L axis up-regulated ICOSL on germinal center B cells (30). We observed that CD40 intensities were much higher on naïve B cells than memory B cells, plasma cells, and B cells activated by TLR or BCR agonists (Fig. 3, I and J). Accordingly, ICOSL intensities on B cells, particularly on naïve B cells, were further up-regulated after exposing to TCR-primed TH cells, and this process could be considerably attenuated by blocking the CD40 signals (Fig. 3K). In support of our hypothesis, blocking the CD40 signals also partially suppressed B cell–mediated TH polarization (Fig. 3L). Furthermore, it is known that signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) proteins such as STAT1, STAT3, and STAT4 play crucial roles in inflammatory TH subset differentiation (31–33). However, in our study, exposure to either B cells or an ICOS agonist did not lead to marked activation of STAT1, STAT3, or STAT4 in TH cells (Fig. 3M and fig. S3H). It should also be pointed out that conditioned medium from LPS-activated monocytes rapidly and substantially induced activation of STAT1 and STAT3 in TH cells (Fig. 3M and fig. S3H). These data suggest that inflammatory TH subsets are generated by B cell ICOSL in a STAT signal–independent manner.

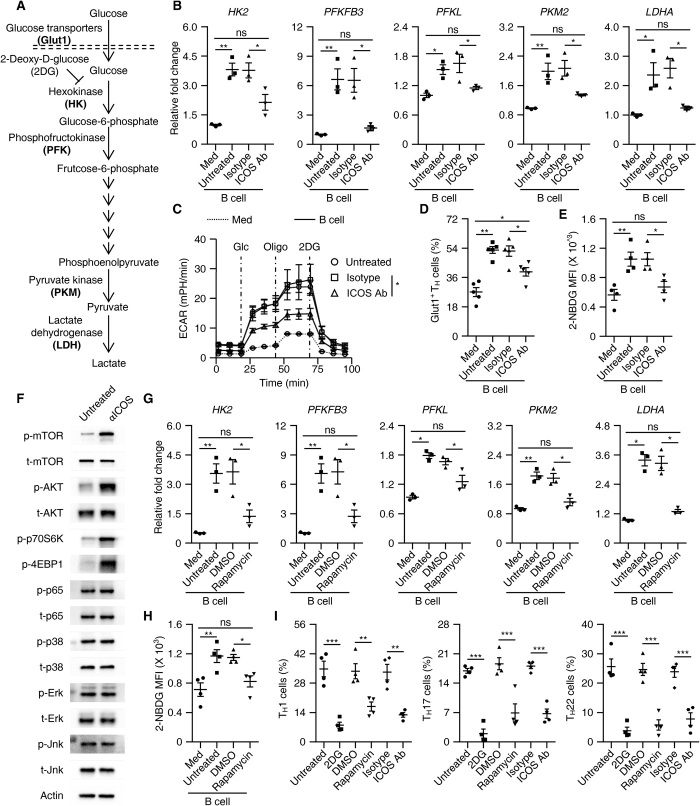

ICOSL-elicited glucose uptake is involved in inflammatory TH polarization by B cells

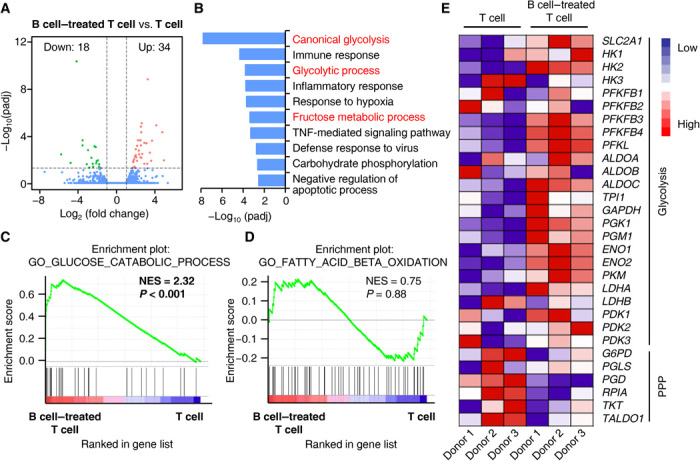

Fundamental processes in T cell biology, such as TH lineage differentiation, are closely linked to changes in the cellular metabolic programs (34). To examine the metabolic process of TH cells after interaction with autologous B cells, we applied RNA sequencing to analyze the transcriptional profiles of the TH cells. We identified 52 genes that were up-regulated or down-regulated at least twofold in TH cells cultured with B cells and annotated these genes using Gene Ontology (GO) (Fig. 4, A and B). Among the top 10 enrichment GO terms, three pathways related to glycolysis were intensively enriched (Fig. 4B). We also noted pathways involving pathological processes, including immune activation, inflammatory response, or defense response to virus (Fig. 4B). Using gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA), we confirmed that TH cells that interacted with B cells expressed genes related to glucose catabolic process (Fig. 4C and fig. S4A) but not genes related to fatty acid catabolic process (Fig. 4D and fig. S4B). Notably, we observed opposite changes in key enzymes related to pentose phosphate pathway in TH cells that interacted with B cells (Fig. 4E).

Fig. 4. Glycolysis is significantly up-regulated in T cells polarized by B cells.

(A) Volcano plot showing changes in genes in TH cells cultured together with total B cells (B cell–treated T cell) for 7 days versus TH cells cultured alone (T cell) for 7 days. Each gene was symbol-coded according to its adjusted P value generated using DESeq2 with a Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) correction. (B) Functional annotation analysis using DAVID tool listing differential gene expression in (A). The top 10 enrichment GO terms are shown. (C and D) GSEA of glucose catabolic process (C) and fatty acid beta oxidation (D) in TH cells cultured together with total B cells for 7 days versus TH cells cultured alone for 7 days. NES, normalized enrichment score. (E) Heat map showing expression of genes associated with glycolysis and pentose phosphate pathway (PPP).

At this point, we considered whether an ICOS signal is required for B cell–elicited glycolysis of TH cells. To address this issue, we used an antibody to specifically shield the ICOS signal in a culture system of TH cells and B cells. As expected, blockade of the ICOS signal successfully suppressed up-regulation of the key rate-limiting glycolytic enzymes HK2, PFKFB3, PFKL, PKM2, and LDHA in TH cells (Fig. 5, A and B). We simultaneously evaluated the extracellular acidification rate (ECAR), which quantifies proton production as a surrogate for lactate production and thus reflects overall glycolytic flux (35). In support of our assumption, TH cells interacting with B cells continued to exhibit substantially (more than fourfold) higher basal and maximal glycolytic rates compared to B cells cultured alone in medium, and this process was effectively abrogated by shielding the ICOS signal (Fig. 5C and fig. S5, A and B). We also detected a marked up-regulation of glucose transporter Glut1 in TH cells after incubating with B cells, and this was also regulated by the ICOS signal (Fig. 5D), suggesting that B cells enhance the ability of TH cells to incorporate glucose in an ICOS signal–dependent manner. Accordingly, we used the fluorescent glucose analog 2-(N-[7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl] amino)-2-deoxyglucose (2-NBDG), which allows direct quantification of glucose incorporation in living cells (36). Consistently, after interacting with B cells, TH cells incorporated significantly more 2-NBDG, and such incorporation was abolished by shielding the ICOS signal (Fig. 5E).

Fig. 5. ICOSL-ICOS axis–elicited glycolysis is involved in T cell polarization by B cells.

(A) Process and key rate-limiting enzymes during glycolysis. (B to E) Purified T cells were cultured in medium or with total B cells in the presence or absence of isotype antibody or ICOS-neutralizing antibody for 7 days, as described in Materials and Methods. Expression of key rate-limiting glycolytic enzymes, ECAR, and capabilities of glucose incorporation (Glut1+ or 2-NBDG intensity) were determined using real-time PCR (B, n = 3), a Seahorse Extracellular Flux XF-24 analyzer (C, n = 3), and FACS (D and E, n = 5 for each), respectively. (F) TCR-primed T cells were left untreated or were stimulated with ICOS agonist antibody for 1 hour. Activation of the indicated signals was detected by immunoblotting (n = 4). (G and H) Using rapamycin to inhibit the mTOR signal impaired B cell–mediated up-regulation of key rate-limiting glycolytic enzymes (G, n = 3) and the incorporation of glucose in TH cells (H, n = 4). DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide. (I) Using 2DG, rapamycin, and ICOS-neutralizing antibody to inhibit glycolysis, the mTOR signal, and the ICOS signal, respectively, suppressed B cell–meditated inflammatory TH subset differentiation on day 7 (n = 5). Data are representative of three independent experiments (B to I). Data are presented as means ± SEM (B to E and G to I). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 (one-way ANOVA test).

To further probe the signaling pathways involved in ICOS signal–mediated inflammatory TH cell differentiation, we examined activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), nuclear factor κB (NFκB), and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT/mTOR pathways in TH cells stimulated with an ICOS agonist. Notably, after undergoing TCR triggering, most signaling pathways in the T cells we analyzed were activated, although to varying extents (Fig. 5F and fig. S5C). In TH cells, an ICOS agonist robustly activated the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways, but not other signals (Fig. 5F and fig. S5C), suggesting that ICOS-induced mTOR activation is involved in B cell–mediated glucose uptake and utilization in TH cells. In line with this, using rapamycin to inhibit the mTOR activation effectively attenuated the expression of key rate-limiting glycolytic enzymes and the incorporation of 2-NBDG in TH cells (Fig. 5, G and H). Also, in support of our view that ICOS signal–elicited mTOR activation and subsequent enhanced glycolysis are essential for the B cell–mediated inflammatory TH subset differentiation, we found that suppressing the mTOR activation with rapamycin or inhibiting the glycolysis with 2-deoxy-d-glucose (2DG) in TH cells considerably attenuated B cell–mediated inflammatory TH subset differentiation to levels comparable to those achieved with an ICOS-shielding antibody (Fig. 5I).

B cell ICOSL-elicited glycolysis maintains pathogenic differentiation of TH subsets in patients with inflammatory disease

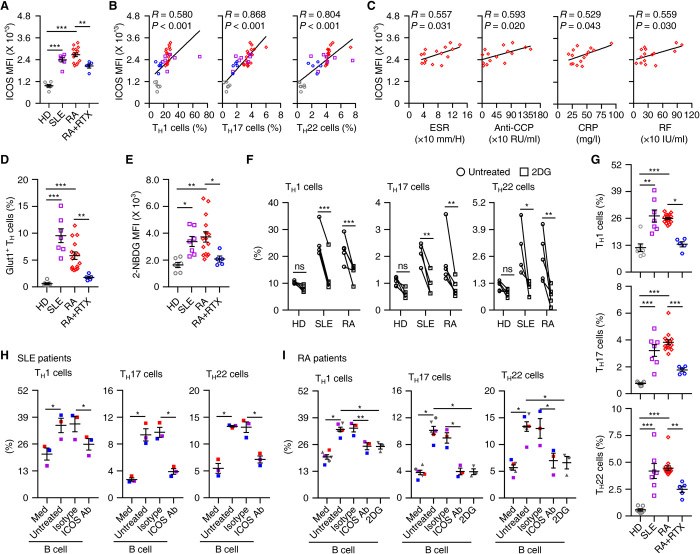

The results described above suggest that ICOSL/ICOS axis–elicited glycolysis plays a pathogenic role in patients with inflammatory diseases. TH cells from blood of RA or SLE patients strongly expressed ICOS receptor at intensities similar to their abilities to produce inflammatory IFN-γ, IL-17, and IL-22 (Fig. 6, A and B). Also, we found significant correlations between ICOS receptor intensities and the pathological parameters rheumatoid factor (RF), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody (CCP), and C-reactive protein (CRP) in RA patients (Fig. 6C). Analogously, the TH cells from blood of RA or SLE patients expressed significantly more Glut1 and actively incorporated 2-NBDG (Fig. 6, D and E). In support of the mentioned observations, exposing these TH cells to the glycolysis inhibitor 2DG for 12 hours markedly attenuated the ability of the cells to produce IFN-γ, IL-17, and IL-22 (Fig. 6F and fig. S6A). Such treatment did not affect inflammatory signature of healthy blood TH cells (Fig. 6F and fig. S6A).

Fig. 6. Depleting B cells attenuates CD4+ T cell inflammation and glycolysis in SLE and RA patients.

(A to E and G) FACS analysis of ICOS expression (A), Glut1 (D), incorporated 2-NBDG (E), and inflammatory cytokines (G) in circulating TH cells from healthy donors (n = 7), SLE patients (n = 7), RA patients (n = 15), and RA patients treated with rituximab (n = 5). Correlations between ICOS expression and inflammatory cytokines in circulating TH cells are shown in (B); correlations between ICOS expression and pathological parameters in circulating TH cells from RA patients are presented in (C). P and R values were calculated based on the analysis of Pearson’s correlation. (F) Purified T cells from blood of healthy donors (n = 5) or patients with SLE (n = 4) or RA (n = 5) were cultured for 12 hours in the presence or absence of 2DG. Expression of IFN-γ, IL-17, and IL-22 in TH cells was detected by FACS. (H and I) Purified CD69+ effector TH cells were cultured in medium or with blood total B cells from patients with SLE (H, n = 3) or RA (I, n = 6) for 7 days in the absence or presence of ICOS-neutralizing antibody or 2DG. Expression of IFN-γ, IL-17, and IL-22 in TH cells was detected by FACS. Data are representative of six independent experiments (F, H, and I). Data are presented as means ± SEM (A, D, E, and G to I). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 [one-way ANOVA test for (A), (D), (E), and (G) to (I); two-way ANOVA test for (F)].

B cells are considered to be a pathogenic factor in autoimmune diseases, and they serve as an important source of ICOSL (Fig. 3, D and E). Therefore, our next goal was to determine the inflammatory signature of TH cells, as well as the ability of such cells to incorporate and use glucose in RA patients who were or were not treated with rituximab, a monoclonal antibody that targets the CD20 B cell–specific antigen (fig. S6B). As expected, TH cells obtained from RA patients after 1 month of rituximab treatment exhibited reduced expression of ICOS and Glut1, and also incorporated significantly less 2-NBDG (Fig. 6, A, D, and E). In support of our hypothesis, the proportion of inflammatory TH subsets sharply declined in RA patients after 1 month of rituximab (Fig. 6G). Furthermore, the percentages of TH cells exhibiting an activated effector memory phenotype (CD69+CD45RA−CCR7−) were significantly increased in blood from RA or SLE patients compared with normal blood (fig. S6C). In an ex vivo coculture system of TH cells and autologous B cells from blood obtained from untreated RA or SLE patients, we observed that B cells efficiently expanded inflammatory TH subsets from activated effector memory TH cells, but not from the CD69− TH cells, and this process was attenuated by an ICOS antibody or a glycolysis inhibitor (Fig. 6, H and I, and fig. S6, D and E). It is important to note that, in the described system, we cultured TH cells and B cells without additional TCR triggering and only under serum conditions, which supports our hypothesis that B cells, under pathological conditions, can spontaneously polarize inflammatory TH subsets.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have established the central roles of B cells in adaptive host defense (5, 37), and in the present investigation, we identified a previously unrecognized helper function of B cells, particularly resting naïve B cells. This function is involved in shaping the metabolic process and subsequent pathogenic differentiation of inflammatory TH subsets, and we used multiple complementary strategies to map the conditions, mechanisms of regulation, and clinical relevance of this interplay during pathological processes.

Mature B cells act via an antibody-dependent pathway to mobilize effector cells (macrophages and natural killer cells) to enhance antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (38). However, during chronic inflammation, participation of mature B cells, also in an antibody-dependent manner, is implicated in pathogenic M2b macrophage differentiation (23, 39, 40). Analogously, memory B cells function via an HLA-DR (human leukocyte antigen–DR)–dependent pathway to present antigens that initiate TH1 responses (41, 42), whereas regulatory B cells, which frequently display a CD27+/high memory phenotype, defeat cytotoxic T cells by releasing IL-10 (43–45). Thus, B cells are versatile in that they create either immune surveillance or suppression according to their differentiation stages or environmental signals. In the present study, resting B cells spontaneously triggered inflammatory TH subsets from memory CD4+ T cells undergoing TCR triggering. Comparing the functions of naïve B cells, memory B cells, and plasma cells in generating inflammatory TH subsets reveals that naïve B cells have the greatest potential during that process. It is plausible that B cell maturation can represent a feedback mechanism that hampers the ability of these cells to trigger inflammation. This notion is supported by our finding that B cells preexposed to TLR or BCR agonists that activate signals associated with B cell maturation (46, 47) displayed an impaired potential to generate inflammatory TH subsets.

In both mice and humans, phosphorylation of STAT3 is involved in TH17 and TH22 development, whereas STAT1 is selective for TH1 (32, 33). We have previously demonstrated that TH1/TH17 and TH1/TH22 subset development is promoted by inflammatory cytokines that are released by activated monocytes operating via pathways dependent on both STAT1 and STAT3 (22, 48). However, in the current investigation, we observed that B cells generate inflammatory TH subsets via mechanisms that differ from those used by activated monocytes. We found that the ICOSL/ICOS axis is vital for B cell–mediated inflammatory TH subset differentiation, and this is supported by the results of four sets of experiments. First, most types of B cells we analyzed express ICOSL, and their abilities to trigger inflammatory TH subsets depend on ICOSL intensities. Second, upon TCR triggering, TH cells exhibited amplified ICOS expression, and they were subsequently able to differentiate into inflammatory TH subsets after interacting with B cells. Third, either blocking the ICOS receptor by a specific antibody or silencing ICOS expression by an siRNA successfully abrogated such B cell–mediated inflammatory TH subset differentiation. Fourth, an ICOS agonist effectively activated the mTOR signal in TH cells, and inhibiting the mTOR signal terminated polarization of the inflammatory TH cells by B cells. Therefore, modulation of ICOSL/ICOS interaction may represent a mechanism that controls the inflammatory response mediated by T cells. In support of our findings, although not directly related to inflammatory TH17 and TH22, studies have identified the ICOSL/ICOS axis as an important regulator of differentiation of germinal center Tfh cells (29).

Despite recent success in demonstrating the importance of glycolysis in maintaining the development and functions of inflammatory T cells (14), the mechanisms that reshape the metabolic program of T cells during that process are still unclear. It has been established that the TCR signal is an important inducer of T cell glycolysis (49). However, TCR triggering alone only marginally trigger inflammatory polarization of TH subsets. Our data show that, after encountering ICOSL+ B cells, TCR-primed T cells additionally acquire the capacity to efficiently incorporate and use glucose, and subsequently differentiate into pathogenic inflammatory TH subsets. Besides being improved by ICOSL+ B cells, T cell glycolysis is also enhanced by activated myeloid cells (13, 50). Notably, ICOSL+ B cells enhance T cell glycolysis via cell-to-cell contact, whereas activated myeloid cells promote T cell glycolysis by releasing inflammatory mediators (13, 50, 51). Together, these observations reveal a complicated contexture of T cells using glycolysis. Analogously, TCR triggering can activate multiple signaling pathways in T cells, and ICOSL exclusively induces phosphorylation of mTOR signal in those cells and contributes to subsequent TH subset differentiation. Therefore, studying the mechanisms that can selectively modulate the activities of T cell glycolysis might provide a novel approach to therapeutic strategies for inflammatory diseases.

Under chronic pathological conditions, TH cells often play a pathogenic role by initiating and maintaining inflammation, even though most of these cells exhibit an activated effector memory phenotype (52–54). Our results provide important new insights into the previously unrecognized helper role of B cells during the immunopathogenesis of T cell inflammation. After interacting directly with ICOSL+ B cells, TCR-primed memory TH cells acquire the ability to incorporate and use glucose, and they subsequently differentiate into pathogenic inflammatory TH subsets and thereby create conditions that are conducive to chronic inflammation. Consistent with this, when activated effector memory TH cells derived from blood of RA or SLE patients encounter autologous B cells, they spontaneously polarize into inflammatory TH subsets. A strategy that specifically targets B cells with an anti-CD20 antibody in RA patients effectually retracts the increased glucose uptake and glycolysis in TH cells, and successfully abrogates the pathogenic differentiation of those cells. In addition to being of biological importance, our work may be relevant in clinical management of inflammatory diseases. Our data raise an important clinical question: Is B cell depletion suitable for patients suffering from autoimmune diseases with a high degree of inflammatory TH cell infiltration? We suggest that B cell–associated therapeutic strategies should target not only autoantibody-elicited tissue damage but also the pathogenic inflammatory responses of TH cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and specimens

Blood samples were collected from RA and SLE patients at the Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Chinese Medicine and The Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University. The specific characteristics of the RA and SLE in the patients are outlined in tables S1 and S2. Rituximab therapy was administered intravenously at a dose of 1000 mg at baseline and week 2. All patients given rituximab therapy had active disease before treatment and thereafter were responding (American College of Rheumatology >50). The synovial biopsy specimens were obtained from all RA patients by needle arthroscopy of the affected knee at baseline.

HCC samples were obtained from patients undergoing curative resection at the Cancer Center of Sun Yat-sen University (table S3). None of the patients had received anticancer therapy before sampling, and those with concurrent autoimmune disease, HIV, or syphilis were excluded. Paired fresh blood samples taken on day of surgery and tumor tissues from seven patients with HCC who underwent surgical resections in 2015 were used to isolate peripheral and tissue-infiltrating leukocytes. Clinical stages were classified according to the guidelines of the International Union Against Cancer.

Human tonsil tissue samples from patients with tonsillitis undergoing routine tonsillectomies were obtained from The Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University.

All samples were anonymously coded in accordance with local ethical guidelines (as stipulated by the Declaration of Helsinki). Written informed consent was obtained from the patients, and the protocol was approved by the Review Board of Sun Yat-sen University.

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence

Paraffin-embedded human HCCs, tonsils, and RA samples were cut in 5-μm sections, which were processed for immunohistochemistry. The sections were subsequently incubated with antibodies against human CD4 (1:200, Abcam), CD20 (1:200, ZSBio), CD68 (1:200, Dako), or S100 (1:200, ZSBio) and then stained in the Envision System (DakoCytomation).

Sections (5 μm) of frozen HCCs, tonsils, and RA samples were processed for immunofluorescence. The sections were stained with rabbit anti-human CD4 (1:200, Abcam) and mouse anti-human CD20 (1:200, ZSBio), followed by Alexa Fluor 555–conjugated anti-rabbit IgG and Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated anti-mouse IgG. Positive cells were detected by confocal microscopy (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

Isolation of mononuclear cells from peripheral blood and tissues

Peripheral mononuclear leukocytes were isolated by Ficoll density gradient centrifugation, and fresh tissue–infiltrating mononuclear leukocytes were obtained as described previously (22). Thereafter, the mononuclear cells were washed and resuspended in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Isolation of total B cells, T cells, naïve T cells, and memory T cells from the leukocytes was achieved with a MACS column purification system (Miltenyi Biotec). CD19+IgD+CD27− naïve B cells, CD19+IgD−CD27+ memory B cells, CD19+CD38++CD27++CD138+ plasma cells, and CD19+CD38−CD27− naïve B cells were further sorted by FACS (MoFlo, Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA) (fig. S2, A and B). These cells were used in subsequent experiments.

Flow cytometry (FACS)

T and B cells from peripheral blood, tissues, and ex vivo or in vitro culture were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies and then analyzed by FACS. The peripheral leukocytes, tissue-infiltrating leukocytes, and T cells from in vitro culture were stimulated with Leukocyte Activation Cocktail (BD Pharmingen) at 37°C for 5 hours. Thereafter, the cells were stained with surface markers, fixed and permeabilized with IntraPrep reagent (Beckman Coulter), and finally stained with intracellular markers. To detect T-bet, RORγt, AHR, and Ki-67 in nuclei, the cells were fixed and permeabilized using reagent from eBioscience. Data were acquired using a Gallios flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter). The fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies used are shown in table S4.

Immunoblotting

Proteins from cells were extracted as previously described (41). The antibodies used are shown in table S4.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Concentrations of the inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12p70, IL-23, TGF-β, IFN-γ, IL-17, and IL-22 in the supernatants from in vitro culture systems were detected using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions (eBioscience). The antibodies used are shown in table S4.

Real-time polymerase chain reaction

TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) was used to isolate total RNA of cells from an in vitro culture system. Aliquots (2 μg) of the RNA were reverse-transcribed using Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Promega). The specific primers used to amplify the genes are listed in table S4. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed in triplicate using SYBR Green Real-Time PCR MasterMix (TOYOBO) in a Roche LightCycler 480 System. All results are presented in arbitrary units relative to 18S ribosomal RNA expression.

In vitro T cell culture system

Purified autologous total T cells, naïve T cells, and memory T cells (Miltenyi Biotec) were left untreated; were pretreated with an ICOS neutralizing antibody (10 μg/ml), 2DG (5 mM), or rapamycin (20 nM); or were infected with siRNA. Thereafter, the T cells were cultured for 2 days in medium alone or with CD19+ B cells, naïve B cells, memory B cells, plasma cells, or culture supernatant from B cells or B cells plus T cells in the presence or absence of anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 (2.5 μg/ml) (eBioscience). Subsequently, the cells were maintained in RPMI medium supplemented with IL-2 (20 IU/ml) (eBioscience) for indicated times in the presence of different cells or antibodies. In some cases, CD19+ B cells were stimulated with anti-IgM antibody (5 μg/ml), Pam3CysSK4 (5 μg/ml), LPS (5 μg/ml), poly(I:C) (5 μg/ml), or CpG ODNs (2.5 μg/ml) for 18 hours and then washed and cultured with T cells. Other culture systems were treated with neutralizing antibodies against IL-1β (10 μg/ml), IL-6 (25 μg/ml), IL-12p70 (10 μg/ml), IL-23 (10 μg/ml), or TGF-β (25 μg/ml) (all from R&D Systems); the neutralizing antibodies were present throughout the entire culture processes and are listed in table S4.

T cells infected with siRNA

The candidate sequences for human si-ICOS or si-NC were transferred into the cells through nucleofection technology (Nucleofector 4D Device, Lonza). The efficiency of knockdown was determined by FACS 24 hours later, and the cells were used in subsequent experiments. The specific siRNA sequences are listed in table S4.

ECAR analyses

Measurement of the ECAR of T cells was done using the XF-24 Extracellular Flux Analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience). T cells were pretreated with ICOS-neutralizing antibody or isotype and then cultured alone or with autologous B cells for 7 days. T cells were isolated from a culture system using a MACS column purification system (Miltenyi Biotec). The purified cells were subsequently resuspended in XF Base Medium Minimal DMEM (pH 7.4) with l-glutamine (2 mM) and then placed on a cell culture microplate (5 × 105 cells per well; XF-24, Seahorse Bioscience). Glucose (10 mM), oligomycin A (1 μM), and 2DG (50 mM) were added to the cells before performing real-time measurement of the ECAR.

Glucose uptake assay

Purified T cells were starved of glucose by incubation for 1 hour in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then stained with 2-NBDG (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min at 37°C and subjected to flow cytometric analysis.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as means ± SEM. Group data were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Student’s t test. All data were assessed using two-tailed tests, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. No statistical method was used to predetermine sample size.

Acknowledgments

We thank P. Ödman for linguistic revision of the manuscript. Funding: The study was supported by project grants from the National Key Research and Development Plan of China (2018ZX10302205 and 2016YFA0502600); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31830025, 91942309, and 81802403); the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, China (2018B030308010); and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (19lgjc09, 19lgpy167, and 19lgpy171). Author contributions: Q.-H.Z., Y.W., X.-M.L., and D.-P.C. performed most of the experiments and analyzed the results. X.-M.L., M.H., and Y.L. provided clinical samples and analyzed the related clinical data. Y.W. and D.-P.C. contributed to FACS and analyzed the data. Q.-Y.L. and C.-X.H. performed immunohistochemical staining and image analysis. L.Z. and B.L. made technical and intellectual contributions. D.-M.K., Y.C., and G.-B.Z. contributed to study design, supervised the study, and/or contributed to writing the manuscript. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data associated with this study are present in the paper or the Supplementary Materials. The materials that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. RNA sequencing data have been deposited in GEO: GSE144339.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/37/eabb6296/DC1

References and Notes

- 1.Germain R. N., The cellular determinants of adaptive immunity. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 1083–1085 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qiao J., Liu Z., Dong C., Luan Y., Zhang A., Moore C., Fu K., Peng J., Wang Y., Ren Z., Han C., Xu T., Fu Y. X., Targeting tumors with IL-10 prevents dendritic cell-mediated CD8(+) T cell apoptosis. Cancer Cell 35, 901–915.e4 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang W., Green M., Choi J. E., Gijon M., Kennedy P. D., Johnson J. K., Liao P., Lang X., Kryczek I., Sell A., Xia H., Zhou J., Li G., Li J., Li W., Wei S., Vatan L., Zhang H., Szeliga W., Gu W., Liu R., Lawrence T. S., Lamb C., Tanno Y., Cieslik M., Stone E., Georgiou G., Chan T. A., Chinnaiyan A., Zou W., CD8(+) T cells regulate tumour ferroptosis during cancer immunotherapy. Nature 569, 270–274 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kwak K., Akkaya M., Pierce S. K., B cell signaling in context. Nat. Immunol. 20, 963–969 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang S. S., Liu W., Ly D., Xu H., Qu L., Zhang L., Tumor-infiltrating B cells: Their role and application in anti-tumor immunity in lung cancer. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 16, 6–18 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cyster J. G., Allen C. D. C., B cell responses: Cell interaction dynamics and decisions. Cell 177, 524–540 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dorner T., Radbruch A., Burmester G. R., B-cell-directed therapies for autoimmune disease. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 5, 433–441 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu H., Deng Y., Feng Y., Long D., Ma K., Wang X., Zhao M., Lu L., Lu Q., Epigenetic regulation in B-cell maturation and its dysregulation in autoimmunity. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 15, 676–684 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hong S., Zhang Z., Liu H., Tian M., Zhu X., Zhang Z., Wang W., Zhou X., Zhang F., Ge Q., Zhu B., Tang H., Hua Z., Hou B., B cells are the dominant antigen-presenting cells that activate naive CD4(+) T cells upon immunization with a virus-derived nanoparticle antigen. Immunity 49, 695–708.e4 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu R. X., Wei Y., Zeng Q. H., Chan K. W., Xiao X., Zhao X. Y., Chen M. M., Ouyang F. Z., Chen D. P., Zheng L., Lao X. M., Kuang D. M., Chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 3-positive B cells link interleukin-17 inflammation to protumorigenic macrophage polarization in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 62, 1779–1790 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meffre E., O’Connor K. C., Impaired B-cell tolerance checkpoints promote the development of autoimmune diseases and pathogenic autoantibodies. Immunol. Rev. 292, 90–101 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu J., Yamane H., Paul W. E., Differentiation of effector CD4 T cell populations (*). Annu. Rev. Immunol. 28, 445–489 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saravia J., Chapman N. M., Chi H., Helper T cell differentiation. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 16, 634–643 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bantug G. R., Galluzzi L., Kroemer G., Hess C., The spectrum of T cell metabolism in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 18, 19–34 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biswas S. K., Metabolic reprogramming of immune cells in cancer progression. Immunity 43, 435–449 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phan A. T., Goldrath A. W., Glass C. K., Metabolic and epigenetic coordination of T cell and macrophage immunity. Immunity 46, 714–729 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Michalek R. D., Gerriets V. A., Jacobs S. R., Macintyre A. N., MacIver N. J., Mason E. F., Sullivan S. A., Nichols A. G., Rathmell J. C., Cutting edge: Distinct glycolytic and lipid oxidative metabolic programs are essential for effector and regulatory CD4+ T cell subsets. J. Immunol. 186, 3299–3303 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Macintyre A. N., Gerriets V. A., Nichols A. G., Michalek R. D., Rudolph M. C., Deoliveira D., Anderson S. M., Abel E. D., Chen B. J., Hale L. P., Rathmell J. C., The glucose transporter Glut1 is selectively essential for CD4 T cell activation and effector function. Cell Metab. 20, 61–72 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lanzavecchia A., Antigen-specific interaction between T and B cells. Nature 314, 537–539 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Constant S., Schweitzer N., West J., Ranney P., Bottomly K., B lymphocytes can be competent antigen-presenting cells for priming CD4+ T cells to protein antigens in vivo. J. Immunol. 155, 3734–3741 (1995). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farber D. L., Yudanin N. A., Restifo N. P., Human memory T cells: Generation, compartmentalization and homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 14, 24–35 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuang D. M., Xiao X., Zhao Q., Chen M. M., Li X. F., Liu R. X., Wei Y., Ouyang F. Z., Chen D. P., Wu Y., Lao X. M., Deng H., Zheng L., B7-H1-expressing antigen-presenting cells mediate polarization of protumorigenic Th22 subsets. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 4657–4667 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen M. M., Xiao X., Lao X. M., Wei Y., Liu R. X., Zeng Q. H., Wang J. C., Ouyang F. Z., Chen D. P., Chan K. W., Shi D. C., Zheng L., Kuang D. M., Polarization of tissue-resident TFH-like cells in human hepatoma bridges innate monocyte inflammation and M2b macrophage polarization. Cancer Discov. 6, 1182–1195 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu M. M., Pu Y., Han D., Shi Y., Cao X., Liang H., Chen X., Li X. D., Deng L., Chen Z. J., Weichselbaum R. R., Fu Y. X., Dendritic cells but not macrophages sense tumor mitochondrial DNA for cross-priming through signal regulatory protein α signaling. Immunity 47, 363–373.e5 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kryczek I., Wei S., Gong W., Shu X., Szeliga W., Vatan L., Chen L., Wang G., Zou W., Cutting edge: IFN-gamma enables APC to promote memory Th17 and abate Th1 cell development. J. Immunol. 181, 5842–5846 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilke C. M., Kryczek I., Zou W., Antigen-presenting cell (APC) subsets in ovarian cancer. Int. Rev. Immunol. 30, 120–126 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zou W., Restifo N. P., T(H)17 cells in tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10, 248–256 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee Y., Awasthi A., Yosef N., Quintana F. J., Xiao S., Peters A., Wu C., Kleinewietfeld M., Kunder S., Hafler D. A., Sobel R. A., Regev A., Kuchroo V. K., Induction and molecular signature of pathogenic TH17 cells. Nat. Immunol. 13, 991–999 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pedros C., Zhang Y., Hu J. K., Choi Y. S., Canonigo-Balancio A. J., Yates J. R. III, Altman A., Crotty S., Kong K. F., A TRAF-like motif of the inducible costimulator ICOS controls development of germinal center TFH cells via the kinase TBK1. Nat. Immunol. 17, 825–833 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu D., Xu H., Shih C., Wan Z., Ma X., Ma W., Luo D., Qi H., T-B-cell entanglement and ICOSL-driven feed-forward regulation of germinal centre reaction. Nature 517, 214–218 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang R., Tan Z., Deng L., Chen Y., Xia Y., Gao Y., Wang X., Sun B., Interleukin-22 promotes human hepatocellular carcinoma by activation of STAT3. Hepatology 54, 900–909 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kryczek I., Lin Y., Nagarsheth N., Peng D., Zhao L., Zhao E., Vatan L., Szeliga W., Dou Y., Owens S., Zgodzinski W., Majewski M., Wallner G., Fang J., Huang E., Zou W., IL-22(+)CD4(+) T cells promote colorectal cancer stemness via STAT3 transcription factor activation and induction of the methyltransferase DOT1L. Immunity 40, 772–784 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Shea J. J., Lahesmaa R., Vahedi G., Laurence A., Kanno Y., Genomic views of STAT function in CD4+ T helper cell differentiation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 11, 239–250 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kouidhi S., Noman M. Z., Kieda C., Elgaaied A. B., Chouaib S., Intrinsic and tumor microenvironment-induced metabolism adaptations of T cells and impact on their differentiation and function. Front. Immunol. 7, 114 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.TeSlaa T., Teitell M. A., Techniques to monitor glycolysis. Methods Enzymol. 542, 91–114 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamada K., Saito M., Matsuoka H., Inagaki N., A real-time method of imaging glucose uptake in single, living mammalian cells. Nat. Protoc. 2, 753–762 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scott A. M., Wolchok J. D., Old L. J., Antibody therapy of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12, 278–287 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nimmerjahn F., Ravetch J. V., Fcγ receptors: Old friends and new family members. Immunity 24, 19–28 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wei Y., Lao X. M., Xiao X., Wang X. Y., Wu Z. J., Zeng Q. H., Wu C. Y., Wu R. Q., Chen Z. X., Zheng L., Li B., Kuang D. M., Plasma cell polarization to the immunoglobulin G phenotype in hepatocellular carcinomas involves epigenetic alterations and promotes hepatoma progression in mice. Gastroenterology 156, 1890–1904.e16 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mantovani A., B cells and macrophages in cancer: Yin and yang. Nat. Med. 17, 285–286 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jelcic I., Al Nimer F., Wang J., Lentsch V., Planas R., Jelcic I., Madjovski A., Ruhrmann S., Faigle W., Frauenknecht K., Pinilla C., Santos R., Hammer C., Ortiz Y., Opitz L., Gronlund H., Rogler G., Boyman O., Reynolds R., Lutterotti A., Khademi M., Olsson T., Piehl F., Sospedra M., Martin R., Memory B cells activate brain-homing, autoreactive CD4(+) T cells in multiple sclerosis. Cell 175, 85–100.e23 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harp C. T., Ireland S., Davis L. S., Remington G., Cassidy B., Cravens P. D., Stuve O., Lovett-Racke A. E., Eagar T. N., Greenberg B. M., Racke M. K., Cowell L. G., Karandikar N. J., Frohman E. M., Monson N. L., Memory B cells from a subset of treatment-naïve relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients elicit CD4+ T-cell proliferation and IFN-γ production in response to myelin basic protein and myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein. Eur. J. Immunol. 40, 2942–2956 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xiao X., Lao X. M., Chen M. M., Liu R. X., Wei Y., Ouyang F. Z., Chen D. P., Zhao X. Y., Zhao Q., Li X. F., Liu C. L., Zheng L., Kuang D. M., PD-1hi identifies a novel regulatory B-cell population in human hepatoma that promotes disease progression. Cancer Discov. 6, 546–559 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Iwata Y., Matsushita T., Horikawa M., Dilillo D. J., Yanaba K., Venturi G. M., Szabolcs P. M., Bernstein S. H., Magro C. M., Williams A. D., Hall R. P., Clair E. W. S., Tedder T. F., Characterization of a rare IL-10-competent B-cell subset in humans that parallels mouse regulatory B10 cells. Blood 117, 530–541 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Masson A., Bouaziz J. D., Le Buanec H., Robin M., O’Meara A., Parquet N., Rybojad M., Hau E., Monfort J. B., Branchtein M., Michonneau D., Dessirier V., Sicre de Fontbrune F., Bergeron A., Itzykson R., Dhedin N., Bengoufa D., Peffault de Latour R., Xhaard A., Bagot M., Bensussan A., Socie G., CD24(hi)CD27(+) and plasmablast-like regulatory B cells in human chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood 125, 1830–1839 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burger J. A., Wiestner A., Targeting B cell receptor signalling in cancer: Preclinical and clinical advances. Nat. Rev. Cancer 18, 148–167 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bourke E., Bosisio D., Golay J., Polentarutti N., Mantovani A., The toll-like receptor repertoire of human B lymphocytes: Inducible and selective expression of TLR9 and TLR10 in normal and transformed cells. Blood 102, 956–963 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kuang D. M., Peng C., Zhao Q., Wu Y., Chen M. S., Zheng L., Activated monocytes in peritumoral stroma of hepatocellular carcinoma promote expansion of memory T helper 17 cells. Hepatology 51, 154–164 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Menk A. V., Scharping N. E., Moreci R. S., Zeng X., Guy C., Salvatore S., Bae H., Xie J., Young H. A., Wendell S. G., Delgoffe G. M., Early TCR signaling induces rapid aerobic glycolysis enabling distinct acute T cell effector functions. Cell Rep. 22, 1509–1521 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Revu S., Wu J., Henkel M., Rittenhouse N., Menk A., Delgoffe G. M., Poholek A. C., McGeachy M. J., IL-23 and IL-1beta drive human Th17 cell differentiation and metabolic reprogramming in absence of CD28 costimulation. Cell Rep. 22, 2642–2653 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Saha S., Shalova I. N., Biswas S. K., Metabolic regulation of macrophage phenotype and function. Immunol. Rev. 280, 102–111 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Omenetti S., Bussi C., Metidji A., Iseppon A., Lee S., Tolaini M., Li Y., Kelly G., Chakravarty P., Shoaie S., Gutierrez M. G., Stockinger B., The intestine harbors functionally distinct homeostatic tissue-resident and inflammatory Th17 Cells. Immunity 51, 77–89.e6 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Komuczki J., Tuzlak S., Friebel E., Hartwig T., Spath S., Rosenstiel P., Waisman A., Opitz L., Oukka M., Schreiner B., Pelczar P., Becher B., Fate-mapping of GM-CSF expression identifies a discrete subset of inflammation-driving T helper cells regulated by cytokines IL-23 and IL-1β. Immunity 50, 1289–1304.e6 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tumes D. J., Papadopoulos M., Endo Y., Onodera A., Hirahara K., Nakayama T., Epigenetic regulation of T-helper cell differentiation, memory, and plasticity in allergic asthma. Immunol. Rev. 278, 8–19 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/37/eabb6296/DC1