Many doctors, both general practitioners and specialists, find endometriosis difficult to manage. Equally, many patients are dissatisfied with the care they receive. Endometriosis is the presence of endometrium at sites outside the endometrial cavity. It has long been known that the symptoms experienced by a patient may seem disproportionate to the extent of the disease observed within that patient's pelvis. For the patient it is not the endometriosis that is important but rather the illness that they experience. In this article I address the treatment of symptomatic endometriosis and infertility associated with the disease.

Summary points

Endometriosis is a common cause of pelvic pain

The disease is difficult to diagnose because patients may present with a variety of symptoms

In primary care first line management should include non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the combined oral contraceptive

Referral is indicated when first line management fails or infertility is a problem

Controversy exists over the precise role of surgery and further evidence is required

Methods

This review is based on information from the controlled trials register of the Cochrane Library and the personal experience of the author.

Managing symptomatic endometriosis

Patients with endometriosis may present with many different symptoms. The most common symptom is dysmenorrhoea. Often the patient presents when the dysmenorrhoea increases in severity. Dysmenorrhoea may precede the onset of menstruation. Endometriosis is the underlying cause in 15% of cases of pelvic pain.1 The variety of symptoms and their different presentations lead to difficulties in diagnosing the condition. In addition to pain the patient may present with the non-specific symptoms of fatigue, general malaise, and sleep disturbance. Some of the symptoms associated with endometriosis are listed in the box .

Diagnostic difficulty

A recent survey by the National Endometriosis Society (a support organisation for patients in the United Kingdom) of over 200 patients with a proved diagnosis of endometriosis highlighted the problem; the survey found that large numbers of patients were referred to other specialists before seeing a gynaecologist. Of those surveyed, 32% saw one other specialist before being referred to a gynaecologist, and 25% consulted two other specialists before seeing a gynaecologist (A Barnard, personal communication, 2000). Before diagnosis, over half the patients had been told that there was nothing wrong. The consequence of this is to delay the start of effective treatment and cause disillusionment in the patient. Painful symptoms in women of childbearing age may be caused by endometriosis, particularly when the symptoms have a cyclical element. All doctors, therefore, should be alert to this possibility even when the patient presents with apparently non-gynaecological symptoms.

Symptoms of endometriosis

| • Dyschezia (pain on defecation) | |

| •Dysmenorrhoea | • Loin pain |

| • Pelvic pain | • Pain on micturition |

| • Lower abdominal pain or back pain | • Pain on exercise |

| • Dyspareunia | |

Management strategies

Symptomatic endometriosis can be managed medically or surgically. The rationale behind both types of treatment is to remove the endometrial tissue that has been implanted outside the uterus. This rationale may be flawed: treatment may fail to remove the implanted tissue or indeed the implant may not be causing the symptoms. Furthermore, medical treatments for endometriosis act in a variety of ways to abolish the trophic effect of oestradiol on both the eutopic and ectopic endometrium. Drugs commonly used to treat endometriosis and their side effects are shown in the box . Medical treatment probably does not remove the implants but merely suppresses them. Consequently, the patient develops amenorrhoea as all endometrial tissue becomes inactive.

Many patients receive treatment aimed only at resolving the disease, and more consideration of treatments aimed at relieving symptoms, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, is required.2 It is clear, however, that although medical treatment may relieve symptoms it does not bring about resolution of the disease: visible recurrence of disease is associated with continued relief of symptoms.3 All medical treatments seem to be equally effective in managing endometriosis; about 80-85% of patients have improvement in their symptoms.3–6 The difference between various medical treatments is in their side effects, with some treatments being more acceptable than others.

Medical treatment for endometriosis

| Drug | Side effects |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (such as diclofenac, ibuprofen, mefenamic acid) | Gastric irritation |

| Progestogens (such as dydrogesterone, medroxyprogesterone acetate, norethisterone) | Bloating, fluid retention, breast tenderness, nausea |

| Synthetic androgens (such as danazol, gestrinone) | Seborrhoea, acne, weight gain, muscle cramps, menopausal symptoms (excluding osteoporosis) |

| Combined oestrogens and progestogens | Similar to those associated with combined oral contraceptives |

| Gonadotrophin releasing hormone analogues (such as buserelin, goserelin, leuprorelin acetate, nafarelin, triptorelin) | Menopausal symptoms (including osteoporosis) |

| Gonadotrophin releasing hormone analogues and any combined hormone replacement therapy (continuous or sequential) or tibolone | Adding hormone replacement therapy ameliorates the side effects of gonadotrophin releasing hormone analogues |

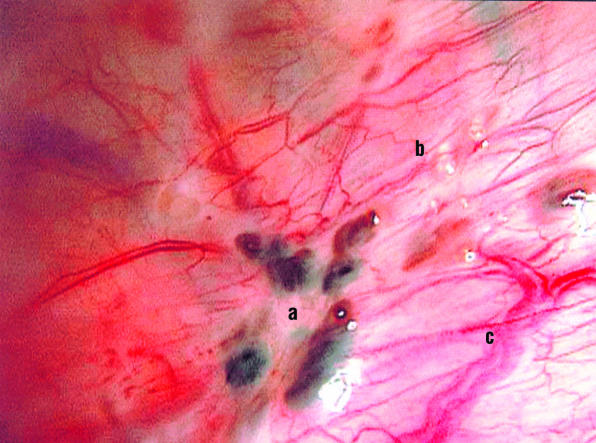

One of the difficulties in diagnosing endometriosis is the need for laparoscopy. It is not possible for every patient in primary care to have laparoscopy. A laparoscopic view of endometrial tissue implanted in the peritoneum is shown in figure 1. In patients who have been newly diagnosed as having endometriosis on the basis of symptoms alone it is appropriate to begin treatment with a combined oral contraceptive or appropriate analgesia, or both. In patients who have previously been diagnosed as having endometriosis and who present with a recurrence of similar symptoms it is acceptable to begin treatment with either the combined oral contraceptive or another effective medical treatment, such as a gonadotrophin releasing hormone analogue. Those patients who do not respond to such interventions should be referred to a gynaecologist. They may require surgical intervention if further medical treatment is ineffective.

Figure 1.

Endometrial tissue implanted in the peritoneum has a varied appearance: blue-black lesions (a), white plaques and clear vesicles (b), and newly formed blood vessels (c)

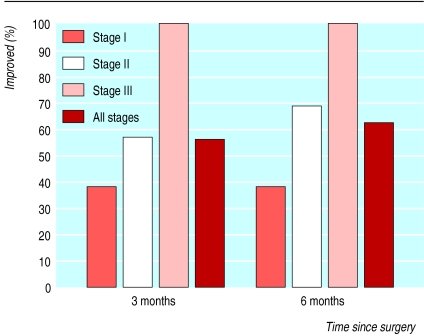

Surgical treatment can be either conservative or radical. Conservative surgery aims to retain the reproductive potential of the patient. However, such surgery may be comparatively radical and involve dissection of the urinary tract, the bowel, and the rectovaginal septum. In common with many surgical treatments, the surgical management of endometriosis has been the subject of fewer randomised controlled trials than medical treatment has, although the evidence base for medical management is not large. One well conducted study of 63 women identified a benefit from conservative surgery, and this benefit seemed to be greater in those with the most severe disease (fig 2).7 Unfortunately, there were only two participants in the group with severe disease, and ethical permission was withheld for the inclusion of patients with even more severe disease.

Figure 2.

Percentage of women whose symptoms improved at three months and six months after surgery for endometriosis.6 Women with more severe disease (stage 3) were likely to have a greater benefit

It has been known since the 1920s that total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy relieve the symptoms of endometriosis. What is less well known is that even if this operation is performed not all of the endometrial tissue implanted outside the uterus will be removed from some patients and thus symptoms may persist. Among patients who do not have a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy there is an appreciable chance that further surgery will be necessary for recurrent symptoms; however, repeat surgery after bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is rare.8When radical surgery is contemplated consideration should also be given to performing a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.

Managing infertility associated with endometriosis

It is well established that a relation exists between endometriosis and infertility. In more severe cases of endometriosis it is obvious that the disease is a cause of the patient's infertility. In such cases fertility is compromised as a consequence of the anatomical distortion of the pelvis caused by adhesions or endometriotic ovarian cysts, or both. In common with other aetiologies that distort the normal reproductive anatomy, such as pelvic infection, the management of infertility is either surgical, to restore normal anatomical relations, or involves in vitro fertilisation. Unlike an infection, endometriosis does not damage the luminal epithelium of the Fallopian tube and thus surgery is more likely to be successful.

In minimal or mild cases of endometriosis, the exact nature of the relation between the disease and infertility is unclear. For example, it is unclear how the superficial peritoneal lesions in figure 2 would give rise to infertility, especially if they were distant from the fimbria of the tubes or ovaries. Consequently, the most appropriate management is also less clear. It is now universally accepted, however, that there is no place for medical treatment with drugs that are also potent contraceptives in the treatment of patients who are infertile.9 The role of ablative surgery is controversial, with practice varying from one gynaecological unit to another in the United Kingdom, although recent guidelines from the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists have advocated its use.10 The guidelines cover all aspects of the management of endometriosis.

Two randomised controlled trials have been carried out to examine the effect on subsequent fertility of the ablation or resection of endometrial tissue implanted outside the uterus.11,12 The first of these, a large multicentre study in Canada of 348 women, showed that there was some benefit from surgical intervention.11 However, the pregnancy rates observed in the intervention group were still comparatively poor when compared with the rates in the control groups in trials of medical treatment of infertility. Additionally, participants in the intervention group also received significant co-interventions that in themselves may have been responsible for some of the benefit. In contrast, the results of another randomised controlled trial of 77 women, which was performed in Italy, found no benefit from surgical intervention.12 Thus despite the royal college's guidelines there remains scientific doubt as to the benefit of surgical intervention.

Conclusions

Endometriosis remains a difficult clinical problem. For the patient it is important that the doctor considers that endometriosis may be causing her problems. Once the diagnosis is made it is equally important that the practitioner determines what underlying problem should be treated—infertility or alleviating painful symptoms—and focuses on the illness rather than the disease. Managing the combined problems of infertility and pain can be particularly difficult; the patient may have to be supported through difficult clinical choices. Whether or not infertility is a problem the patient should always be asked what her future reproductive plans are as this may have an impact on further treatment.

First line treatment for painful symptoms should be medical, including offering appropriate advice on analgesia, and surgery should be reserved for cases in which medical treatment has failed or for patients with more severe disease. In infertility, surgery and assisted conception have a role in moderate and severe disease, but the appropriate management of less severe cases is still uncertain. Certainly in milder cases it would be appropriate to use assisted conception techniques and treat the patient as if she had unexplained infertility; guidelines in the United Kingdom also support the role of surgery. The understanding of endometriosis is evolving and this should eventually translate into an evolution in clinical management.

Additional educational resources

Prentice A et al. Progestagens and antiprogestagens for pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;(2):CD002122.

Wilson M et al. Dysmenorrhoea. In: Clinical evidence. London: BMJ Publishing Group, 2000:1045-57. (December.)

Selak V et al. Danazol for pelvic pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;(2):CD000068.

Moore J et al. Modern combined oral contraceptives for pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;(2):CD001019.

Prentice A et al. Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone analogues for pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;(2):CD000346.

Hughes E et al. Ovulation suppression for endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;(2):CD000155.

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. The investigation and management of endometriosis. Available at www.rcog.org.uk/guidelines/endometriosis.html

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Mahmood TA, Templeton A. Prevalence and genesis of endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 1991;6:544–549. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prentice A, Deary AJ, Bland E. Progestagens and antiprogestagens for pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(2):CD002122. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson M, Farquhar C. Clinical evidence. London: BMJ Publishing Group; 2000. Dysmenorrhoea; pp. 1045–1057. . (December.) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Selak V, Farquhar C, Prentice A, Singla A. Danazol for pelvic pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(2):CD000068. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore J, Kennedy S, Prentice A. Modern combined oral contraceptives for pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(2):CD001019. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prentice A, Deary AJ, Goldbeck-Wood S, Farquhar C, Smith SK. Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone analogues for pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(2):CD000346. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sutton CJ, Ewen SP, Whitelaw N, Haines P. Prospective, randomised, double blind controlled trial of laser laparoscopy in the treatment of pelvic pain associated with minimal, mild, and moderate endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1994;62:696–700. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)56990-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henderson AF, Studd JWW. The role of definitive surgery and hormone replacement therapy in the treatment of endometriosis. In: Thomas E, Rock J, editors. Modern approaches to endometriosis. Carnforth: Kluwer Academic; 1991. pp. 275–290. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hughes E, Fedorkow D, Collins J, Vandekerckhove P. Ovulation suppression for endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(2):CD000155. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. The investigation and management of endometriosis. London: RCOG; 2000. . (guideline No 24.) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marcoux S, Maheux R, Berube S. Laparoscopic Surgery in infertile women with minimal or mild endometriosis. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:217–222. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199707243370401. . (Canadian Collaborative Group on Endometriosis.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parazzini F. Ablation of lesions or no treatment in minimal-mild endometriosis in infertile women: a randomized trial. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:1332–1334. doi: 10.1093/humrep/14.5.1332. . (Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio dell'Endometriosi.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]