ABSTRACT

The COVID-19 pandemic posed a grave threat not only to Indigenous people’s health and well-being, but also to Indigenous communities and societies. This applies also to the Indigenous peoples of the Arctic, where unintentional effects of public health actions to mitigate the spread of virus may have long-lasting effects on vulnerable communities. This study aim was to identify and describe Sámi perspectives on how the Sámi society in Sweden was specifically affected by the pandemic and associated public health actions during 2020–2021. A mixed-method qualitative case study approach was employed, including a media scoping review and stakeholder interviews. The media scoping review included 93 articles, published online or in print, from January 2020 to 1 September 2021, in Swedish or Norwegian, regarding the pandemic-related impacts on Sámi society in Sweden. The review informed a purposeful selection of 15 stakeholder qualitative interviews. Thematic analysis of the articles and interview transcripts generated five subthemes and two main themes: “weathering the storm” and “stressing Sámi culture and society”. These reflect social dynamics which highlight stressors towards, and resilience within, the Sámi society during the pandemic. The results may be useful when evaluating and developing public health crisis response plans concerning or affecting the Sámi society in Sweden.

KEYWORDS: Indigenous health, Saami, qualitative study, circumpolar, minority health, social science, interview study, thematic analysis, public health

Introduction

Early during the coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic it became clear that some populations would be more vulnerable than others as the risk of disease and death varied greatly according to the underlying health status and conditions (older age, obesity, transplanted organs, haematological cancer, lung cancer, diabetes etc.) and their social context [1]. As Indigenous populations globally often experience a higher burden of disease than non-Indigenous counterparts [2–4], concern was expressed that Indigenous peoples would be at particular risk [5]. Similarly, specific factors of the Arctic Indigenous communities, like the pre-existing health inequities [6], and weak health care systems [7,8], were thought to represent pandemic-impact-vulnerabilities, along with environmental, social and geographical conditions (i.e. rurality, remoteness, dependence on fly-in-fly-out workers, unemployment rates and poverty) [9]. Despite this, many Arctic Indigenous communities managed to use their precarious situation to their advantage by imposing strict travel restrictions to their rural and remote locations during the first and second waves [10]. However, in some countries, the COVID-19 pandemic was just temporally delayed in the North, meaning that communities in Alaska, Arctic Russia, and -particularly- northern Sweden, experienced higher infection and death rates compared to the general population in each respective country during the second phase of the pandemic [11,12].

The Indigenous Sámi people refer to their homelands in northern Norway, Sweden, Finland and northwestern Russia as Sápmi. They share a history of having been colonised and seeing their society, culture, language and religion oppressed, but contemporary social, political and health situations differ between Sámi in the different countries. The Sámi demography is unknown, but estimates suggest 75 000 living in the Arctic, with about a third of those residing in the two northernmost regions of Sweden, where they account for about 5% of the total population [13]. The Indigenous status of the Sámi in Sweden was recognised by the Swedish parliament in 1977, and Sweden has signed the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) in 2007. Nonetheless, Sámi [14], national [15], and international critics [16] argue that Sweden still has a long way to go in order to fully realise the special status of the Sámi in health policies. For example, the Sámi do not have the right to use their own language when receiving care from Sweden’s universal health system.

As Sámi ethnicity is not entered into administrative health and death registers, not much is known about how the COVID-19 pandemic impacted the Sámi in Sweden in terms of disease and death. However, a recent population-based survey found that Sámi self-reported a similar but slightly lower prevalence rate (8.4%), compared to the national Swedish average (11.5%), for having tested positively to COVID-19 [17]. Furthermore, pandemic-related impacts on loneliness and time spent outdoors were weaker among Sámi, suggesting the Sámi society may have been less affected by indirect effects as well [17]. Also, health care avoidance did not differ between Sámi and non-Sámi in Sweden during the first year of the pandemic. However, risk groups for such avoidance among the Sámi included Sámi women, young Sámi (18–29 years of age), Sámi living outside Sápmi, Sámi with low income and Sámi experiencing economic stress [18].

A growing body of literature has investigated how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected the Arctic populations beyond a strictly medical perspective, for example examining impacts on mental health and well-being, regional economies, social and cultural environments, knowledge production, mobility, impacts on food security and other social issues [19]. However, Spence & Krishnan [19] found that articles investigating the pandemic-related social dynamics in Indigenous Arctic populations mostly concern the Canadian northern context, and we are unaware of English language articles elucidating how the pandemic affected the Sámi in Sweden, aside from two studies using the SámiHET public health questionnaire data [17,18]. Therefore, in order to understand and learn from how the Sámi in Sweden experienced the pandemic, empirical evidence is needed.

Aim

The aim of this case study is to identify and describe Sámi perspectives on how the Sámi society in Sweden was specifically affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and associated public health actions during 2020–2021.

Method

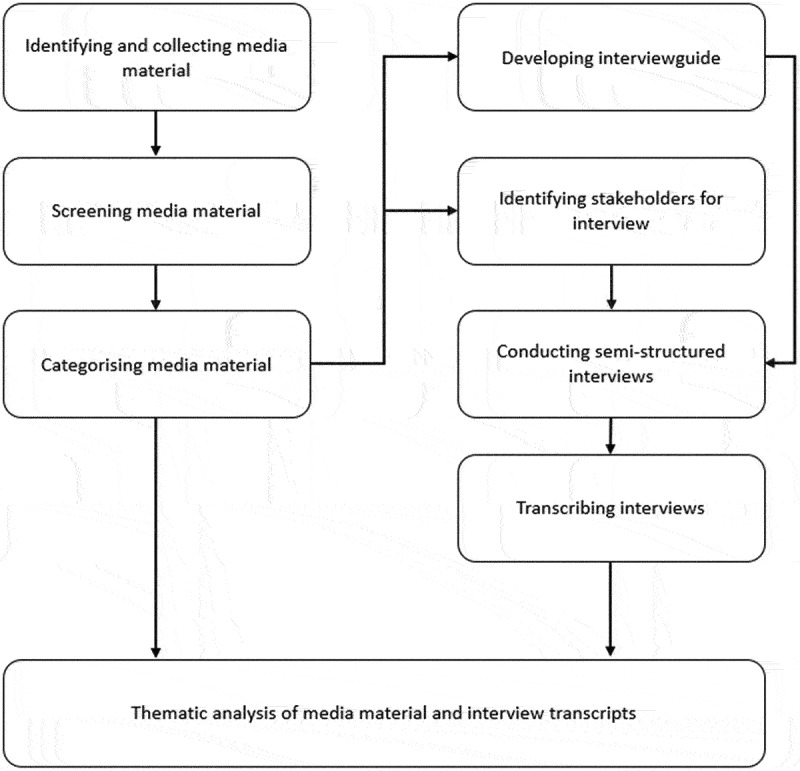

Data collection was carried out in two steps: 1) reviewing media articles, and 2) conducting in-depth interviews (see Figure 1, for a schematic description). The articles identified in the media review informed the interview guide and the purposeful recruiting of interview participants.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the collection of empirical data for the study.

Scoping review method

With assistance from a librarian at Umeå University Library and using the “Mediearkivet” online media archive database, mass media articles were collected from Nordic and Sámi media outlets relating to experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic on the Sámi society on the Swedish side of Sápmi. Both online and printed media articles were included. The keywords used were: “Sámi”, “covid”, “corona”, “Sápmi”, “Sapmi”. A supplementary search was carried out on the “Oddasat.se”1 website to specifically capture Sámi news articles labelled “Corona i Sápmi” (a label used to tag news articles relating to the pandemic in Sápmi). The time period covered was 1 January 2020, to 1 September 2021, and the language was limited to Swedish and Norwegian. Identified media material included news, debate articles and radio features from both printed and online sources.

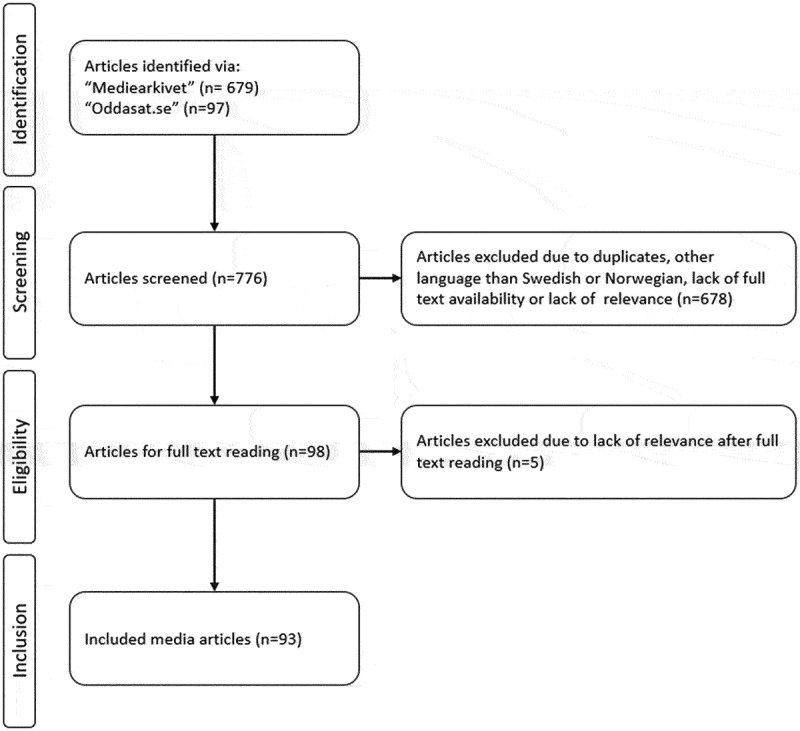

Initial screening of identified articles (n = 776) was carried out by a one of the co-authors, OS. Screened articles were excluded if not being in Swedish or Norwegian language, if full text was not available or if not being of relevance to the study. Articles were considered relevant if they could be said to respond to “how the Sámi society in Sweden was specifically affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and associated public health actions during 2020–2021” (i.e. articles were excluded if merely reporting infection statistics in Sámi areas). The remaining articles (n = 98) were checked for eligibility through independent full text reading by JPAS, OS, and LMN, with exclusion being based on consensus. Thus, all articles considered relevant by at least one reader were included (in 67 cases all agreed of inclusion, in 20 cases two readers agreed and in 6 cases only one reader agreed of inclusion). Of 776 articles, 93 (~12%) remained after the screening process, which is summarised in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow chart for media scoping review.

Of the 93 articles retained, 80 articles were in Swedish (including two Finnish-produced Swedish-language articles) and 13 in Norwegian; 63 articles were radio features with associated short web articles, 24 articles were from printed press (newspapers or magazines, and their corresponding online editions), and the remaining six were web articles for TV features.

All included articles (n = 93) were independently categorised by JPAS, OS and LMN based on what domains of Sámi society the article content concerned (dissenting opinions were discussed and consensus on categorisation was reached). The identified domains included “business life”, “culture and religion”, “politics and activism”, “education and learning”, “healthcare”, “digitisation”, “nature”, and “border closures”. Subsequently, OS re-read and summarised the findings within each identified domain and these texts were used to identify topics for in-depth investigation through interviews, to develop an interview guide and to identify relevant stakeholders and key persons to interview.

Interview method

Purposeful sampling was employed: the authors identified relevant stakeholders and potential participants to best cover the topics of interest identified in the media review. Furthermore, a diverse mix of participants pertaining to their sex, age, and geographical distribution within Sápmi on the Swedish side, was prioritised. The participants had different occupations, including health care worker, teacher, administrator, reindeer herder, tourism entrepreneur and retired. Participants characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Interview participants’ characteristics.

| Characteristics | Number of participants |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 5 |

| Female | 10 |

| County | |

| Norrbotten | 7 |

| Västerbotten | 5 |

| Jämtland and Härjedalen | 3 |

| Age group | |

| 18–35 | 2 |

| 36–55 | 8 |

| 56+ | 5 |

Participants were invited and informed about the study by phone and email. The voluntary nature and the right to withdraw participation at any time without stating reasons, or suffering negative consequences, was stressed. Informed consent was obtained verbally (recorded by the interviewer) before interviews commenced.

An interview guide developed from the domains identified in the media scoping review was used to carry out semi-structured interviews. In total, 16 interviews (30 to 70 minutes, in Swedish) were conducted using phone or a digital meeting program. Interview notes were taken, and audio was recorded and later transcribed verbatim. OS carried out the interviews except for when risk of pre-established relations affecting the interview were detected (JPAS and LMN carried out one interview each, to avoid that). One participant withdrew consent, resulting in 15 interview transcripts for analysis.

Reflexive thematic analysis of media and interview material

The summaries from the media scoping review and the transcribed interviews were analysed inductively employing reflexive thematic analysis [20,21], using the NVivo program. In practice, this meant identifying, delimiting, and distinguishing meaning-bearing units that could be related to the purpose of the study. This can also be described as searching through the data to find and highlight patterns of meaning, thus determining how the data should be understood.

Patterns of meaning were first noted based on identifying text excerpts that described how particular institutions, organisations, family units or individuals were affected. Those text excerpts were then sorted into categories. The categories were summarised in text and illustrated by quotes. This work was carried out by OS, who discussed the on-going process with JPAS and LMN, who also read and commented on the summaries of categories. Thereafter JPAS used the categories, summaries and text excerpts to identify themes and describe these in text (interpreting patterns of latent meaning). All authors provided feedback on the interpretations and formulations of themes, eventually arriving at the results presented here.

Ethics

Ethical permit was sought and approved by The Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Dnr. 2021–04467). In addition, in line with ethical guidelines in Indigenous health research [22,23], support for the study’s implementation was sought from Sámi stakeholders. The research plan was therefore presented to the Sámediggi (Sámi Parliament in Sweden) board and to the Sámiid Riikkasearvi, neither of them expressing any objections to the study. Personal data collected in connection with the study has been handled in accordance with Umeå University’s data storage policy.

Results

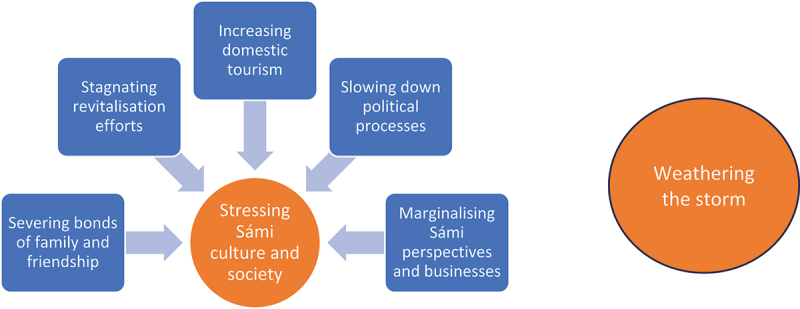

The analysis resulted in two main themes “weathering the storm” and “stressing Sámi culture and society”. The latter of these contained five subthemes (see Figure 3). The themes are presented in the following, with interview excerpts (pseudonymized participant quotes) for illustrative purposes.

Figure 3.

Main themes (in orange) and sub-themes (in blue) that emerged from the analysis.

Main theme: Stressing Sámi culture and society

This theme captures the participants’ views on how the COVID-19 pandemic stressed the Sámi society in specific ways, somehow different in dynamics or magnitude from how Swedish society at large was affected. For example, it includes how the public health measures taken to limit the spread of the corona virus affected the individual, family, and societal fabrics of Sámi life, and how that was detrimental to Sámi identities, knowledge transfer, language revitalisation and political life.

Sub-theme: Severing bonds of family and friendship

Participants shared an understanding of the Sámi society as being held together by the informal bonds of family and friendship, often bridging generational, geographical and jurisdictional borders. This reliance on informal relations was perceived by participants as having left the Sámi society more vulnerable to undesirable side effects of the Swedish COVID-19 pandemic public health response, as it focused on social distancing. A participant explained this:

One of the distinguishing features of Sámi society is that the relatives, the family, get together across the generations. If you then look at those who have their elderly in nursing homes - all of a sudden they are not allowed to meet. It has been devastating, especially for the elderly. And then that you are used to seeing relatives on the Norwegian side and the Finnish side, and there you have different rules for entry and exit and so on. It has naturally also affected the public health situation. People are very upset about not being able to meet. (Saara)

Concern was expressed that the severed relational bonds and increased loneliness may have led to more severe consequences for Sámi mental health and substance use, than for other populations. Aside from border-closures and “closed door” policies on care homes for elderly, the ban on large gatherings was also highlighted as severing bonds. For example, weddings and funerals are often very large in Sámi tradition, as they represent a time for the extended family to meet. A participant commented on this, recalling how family groups at funerals would try to deal with the restriction of no more than eight people (at one point) being allowed to gather, while taking turns to say goodbye to the deceased:

They waved to each other from a distance in the winter darkness. These are quite tragic events. (Alfred)

Sub-theme: Stagnating revitalisation efforts

The participants pointed to how the Sámi society in Sweden is a minority culture, and therefore how the survival of the culture and language in many ways are dependent upon bringing people from different contexts together. Thus, the cancellation of culture festivals, concerts, markets, and language education events were experienced as highly detrimental to Sámi language and culture revitalisation efforts. This affected long standing events like the Jokkmokk winter market, a yearly event gathering tens of thousands of attendees that was cancelled for the first time in more than 400 years. However, it also stopped important events for Sámi identity development and sub-cultures, such as the religious confirmation camp gathering Sámi youth from across the country, and the Sámi Pride.

What we do know is that Sámi activities have a very important role in keeping Sámi civil society together. Because it contributes to the creation of identity and to well-being also for the individual. (Ina)

Furthermore, the systems put in place to revitalise Sámi culture and language were seen as more vulnerable and not sufficiently protected. For example, while Sweden did not lock down schools for children under the age of 16, still the Sámi language classes were often affected as the few local Sámi students would often share language teachers between several schools – and teachers were not allowed to teach physically at different schools, to stop the spread in between. Another important aspect brought up was the detrimental effect on traditional knowledge transfer. This includes the organised education, for example at the Sámij åhpadusguovdásj (the “Sámi educational centre”) which could not continue traditional handicraft classes as usual. Also, in order to protect elderly Sámi, many reindeer herding communities limited the number of representatives from each family to join the yearly reindeer corrals to mark the calves (this is usually a very important event where all families -and generations- still involved in reindeer husbandry will gather to help out). Indeed, as the holders of traditional knowledge are usually elders and the learners are youth, any hindrance to inter-generational meetings would also have represented a lost opportunity for knowledge transfer. A participant recalled the moment he realised the embedded and far-reaching meanings of individuals choosing seemingly mundane option to socially distance themselves:

I remember a specific occasion when one of the slightly older Sámi I met… I met that person at a grocery store in the spring-summer - and then that person said, “This year I’m not going to the mountains at all”. (Alfred)

Sub-theme: Increasing domestic tourism

Many Swedes were hindered from visiting southern Europe during the summer, but no travel restrictions existed within Sweden. Participants regarded the resulting influx of tourists, and its effect both on Sámi society and lands, as a double-edged sword. While Sámi tourist entrepreneurs were supported by tourism, participants also shared frustration that their relatives (living down south) would refrain from visiting so as to not spread the virus – but that domestic tourism increased.

Sure, it’s crazy. It wasn’t just Swedish tourists - now there were an extremely large number of Swedish tourists who came - but also to a certain extent foreigners who have driven to Sweden, for example. And it’s a lot of work. It’s obviously great fun that they want to come up to the mountains, but also strange that… that you can’t stay at home. (Yvonne)

Heavier usage from tourism was understood to result in more damaged land, and both the increased numbers as well as influx of inexperienced wildlife-tourists, led to extra work for reindeer herders whose animals became more dispersed due to tourists lack of experience in how to behave in relation to reindeer. Sub-theme: Slowing down political processes

Except for the Sámi parliament2 elections in May 2021, no democratic elections were scheduled nor took place in Sweden during the study period, 2020–2021. However, all public political debates and other campaign activities leading up to that election were cancelled or were moved to digital arenas. Although participants did not report instances of parties being treated unfairly, this of course impacted the political process. Furthermore, the day to-day political processes within the Sámi parliament were hampered and participants expressed that the Sámi parliament was not prepared to quickly adjust to digital meetings, resulting in postponing some debates and decision processes. Also, some parties and elected parliament members did not attend all scheduled meetings (both due to perceiving them as not safe enough and because of lacking access, for example because of lacking digital infrastructure or knowledge).

I see a democratic problem. How can democracy be accommodated in an acceptable way when people choose, for their own safety, not to come? (Ánte)

The Sámi political life outside organised democratic processes were also said to have slowed down during the pandemic, for example as the (previously lively) Sámi Indigenous movement did not gather for activism. On the other hand, participants also suggested that the rapid adaptation to using digital tools for political meetings and processes may have forced digital competency and infrastructure development, potentially supporting the Sámi political life in the future.

Sub-theme: Marginalising Sámi perspectives and businesses

In a number of different ways, participants suggested that Swedish authorities, government and other actors had overlooked, marginalised or ignored Sámi perspectives and needs during the pandemic. No reporting on COVID-related diseases and deaths among Sámi is one example, although participants meant this is an effect of Sweden not registering Sámi ethnicity in Swedish health registers (making it extremely work-intensive and difficult to report on Sámi-specific numbers). However, Swedish authorities including health care organisations and public health authorities- on both national and regional levels are obliged to consult with the Sámi on matters affecting them. Yet, participants could not recall any extraordinary pandemic-related consultations taking place, and a participant indicated that the ordinary consultation with her regional health care authority had taken place without any focus on the pandemic, nor associated public health measures. Very few directly virus-related consultations were identified to have taken place at all, the exceptions being the Sámi parliament plenary secretary consulting a regional infectious disease officer to inquire about virus mitigation strategies during parliament plenary meetings, and local reindeer herding communities petitioning to local health centres for vaccination priority (which were denied), to enable traditional husbandry activities.

Like most business activities, the Sámi business sector was also affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and the public health measures. Examples include the tourism industry which first took a step turn downwards but later recovered, and the reindeer meat industry which lost sales because of being much dependent on selling to restaurants (which lost their customers). Participants and news articles suggested that while larger Swedish businesses were offered crisis relief and economic support, the Sámi reindeer husbandry industry did not qualify due their distinctive small-scale and “jack-of-all-trades” structure (herders may simultaneously work as entrepreneurs and within cultural-creative business as artists, language workers or with traditional handicraft). On the other hand, a participant suggested that the “jack-of-all-trades” structure may have provided resilience for the Sámi businesses:

We have this habit of being able to adapt and have more support legs as well, and that means that… I don’t think anyone has gone bankrupt, from what I’ve heard, but then it’s probably that they put it on hold. And then it is also very much about the fact that these are very small individual entrepreneurs. It’s not so much limited companies and other things, either. (Maja)

Main theme: Weathering the storm

The participants and the media material did not only suggest problematic ways in which the Sámi society experienced the COVID-19 pandemic, but a central theme was also an understanding that most Sámi had adapted well -and remained loyal- to the social distancing recommendations. This was assumed to be contingent upon the strong Sámi values of centring family, and therefore protecting the elderly. Other Sámi cultural values were also referred to as resources providing crisis readiness and resiliency. Indeed, the Sámi close-to-nature lifestyle was suggested to mean both that Sámi were used to living life far removed from any crowds, being well prepared to fend for themselves both in terms of having stocked traditional foods in the freezer and being emotionally independent, ready to adapt to realities of life.

I think we are quite flexible. I think it is a part of our culture, the Sámi culture, that there is a lot of “weather and wind” that governs/ … /it’s just to accept the way things are and try to make the best of the situation. (Asta)

As mentioned, participants shared that at least parts of Sámi society managed to rapidly transition to and take advantage of digital arenas for purposes such as political meetings, maintaining social relations, selling services and cultural experiences, and for language and cultural educative purposes.

What has happened is that people have understood how good the digital meeting room is as an arena. We have also got this page on Facebook/ … /where people have actually only met to speak Sámi. (Niila)

Perhaps these values and resources contributed to why some participants suggested that Sámi living in rural areas were not much affected by the pandemic.

I think we lived as usual, that everything worked. Of course, we didn’t hang on to each other and kissed and hugged, but we spent time together like the Sámi usually do. (Ahkka)

Discussion

The themes identified in this study highlight specific dynamics that were experienced within the Sámi society due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the implementation of public health prevention measures to decrease infection during 2020 and 2021. Border closures, social distancing, isolation of the elderly, cancellation of Sámi culture and language arenas, effects on Sámi democratic and political life, and marginalisation of Sámi perspectives in government pandemic responses stands out as important challenges experienced by participants. Overall, we have documented resiliency but also concern that the pandemic and associated societal processes may have led to weakening of the social ties that hold the Sámi community together, and associated difficulties in language education, identity development, and intergenerational transfer of traditional knowledge. However, this study does not reveal how common or problematic these social dynamics have been for Sámi.

Although increased loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic is well-documented globally [24] as in the Nordic countries [25], the findings that Sámi experienced a smaller increase in loneliness compared to the general Swedes [17] would suggest that fears voiced by the participants in this study, that Sámi were more dramatically affected by loneliness, might be overstated. However, it is unknown if the health-related effects of loneliness were different among Sámi vs non-Sámi. Furthermore, because loneliness increased progressively during the pandemic, and certain risk-groups were severely more affected [25], the findings from the 2021 SámiHET-study [17] may not be reflecting the dynamics throughout the entire pandemic. It is also possible that the expressed “additional” concern for the lonely Sámi might be more related to elevated Sámi concerns about health risks during the pandemic, which have been also shown by Nilsson, San Sebastián & Stoor [17]. Regardless, despite our uncertainty as to what may explain it, we find the discrepancy noteworthy and hope that future research may shed more light in the issue.

The obstructions to Sámi language and culture revitalisation efforts documented in this study are indeed troubling. However, according to the yearly status reports on the Sámi languages in Sweden, the problem with decreased social contacts between younger and older generation was most prominent during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic [26], after which the effects faded [27]. After that, the pandemic-related problems with language revitalisation were mostly affecting the Sámi children and adults who did not already have someone in their immediate family who spoke the language [28]. On the other hand -albeit being a very crude measure of revitalisation success- the number of Sámi children receiving digital language teaching increased, as did the number of adults studying Sámi language at Swedish universities during 2020–2021 [28]. In another report from the Sámi parliament, the Sámi cultural sector seem largely to agree with the perspectives brought forward by the participants in this study, with regards to the large setback of cultural revitalisation among Sámi in Sweden due to the pandemic [29]. Although the Swedish government put in place several economic crisis support grants for Sámi cultural workers, the long-term effects may be hard to judge. For example, local Sámi associations reported a steep decline in members, potentially affecting the whole Sámi non-governmental sector looking ahead [29]. Regardless, a main obstacle, that has not changed during the pandemic, is the general lack of Sámi statistics in Sweden – making it very difficult to assess for example whether the number of Sámi speakers are increasing, declining or remaining the same – and what processes and challenges affect this [26].

Participants suggested Sámi perspectives were marginalised by Swedish authorities during the pandemic, including for example the Sámi cultural sector, tourism sector and reindeer husbandry. However, the lack of Sámi statistics also makes it very hard to assess the economic effects on the Sámi business life [30]. It may be noted that while the Sámi cultural sector was provided with economic crisis support from the Swedish Ministry of Cultural Affairs, pleas for similar support for other Sámi businesses such as tourism or reindeer husbandry from the Ministry of Enterprise and Innovation [31] were not granted. Similarly, participants suggested no meaningful consultations were held by the Public Health Agency of Sweden regarding the implementation of culturally adapted public health measures. From the perspective of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples [32], including the right to self-determination, it seems problematic if the Swedish government indeed did not consult with the Sámi as regards the best ways and potential impacts of public health policies fundamentally affecting the Sámi society during the pandemic.

Similar to scholarly work from Canadian contexts in the Arctic, this study also identified perspectives suggesting that the Indigenous society remained resilient during the COVID-19 pandemic [33–36], or at least were able to draw from particular strengths to handle negative experiences. However, the Arctic is very diverse, and the Swedish parts of the Arctic are “outliers” in several respects. For example, no Sámi community is responsible for initiating or carrying out public health measures (that responsibility rests with local, regional, and national authorities over which Sámi have no control). Perhaps consequently, pandemic-related social dynamics reflecting Indigenous resiliency in this study was less centred around responsible government handling and more around drawing from Sámi cultural values to act responsibly and patiently: weathering the storm as a family and community, without support from authorities.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this study is the first to qualitatively investigate Sámi experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic in Sweden. As such, the explorative methodology including a review of media and in-depth interviews with diverse Sámi stakeholders seem reasonable. Furthermore, the broad findings reflecting social dynamics in many sectors of Sámi society is likely a result of this particular approach. However, the broad scope also meant that it was not possible to focus on single issues, and only to a limited extent explore divergent opinions and experiences within the dataset. Furthermore, it is important to highlight that the qualitative design used here was not intended to yield representative results of the general Sámi experience. However, this study documents that Sámi in Sweden have experienced these dynamics, at least to some extent.

Future research

This study has explored a number of topics that may deserve more in-depth investigation, or to be investigated using other methods. Given that the findings in this study suggests a lack of consultation with Sámi stakeholders concerning the implementation of public health measures among Sámi, we suggest that it would be of particular interest to comparatively study how the relationships between the Sámi parliaments in Sweden, Norway and Finland and their respective national government may have converged or differed during the pandemic, and what may account for that.

Conclusion

This study has identified and described “weathering the storm” and “stressing Sámi culture and society” as two main themes highlighting Sámi perspectives on how the Sámi society in Sweden was specifically affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and associated public health actions during 2020–2021, reflecting both stressors and resiliency. The social dynamics described within these themes is of importance for understanding how this Arctic Indigenous society was affected and for improving pandemic and public health crisis response plans in the future.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Umeå University Library and librarian Helen Hed for the support during data collection for the media review. We would also like to thank the participants for generously sharing their experiences and opinions. Many thanks - ollu giitu!

Funding Statement

Funding for this research was provided by the Government of Canada as part of a broader Circumpolar research project, entitled ‘COVID-19 Public Health Outcomes in Arctic Communities: A Multisite Case Study Analysis’.

Footnotes

During the study period “Oddasat.se” was the joint publication platform of the Sámi branches within both the public service radio (Swedish Radio, SR) and television (Swedish Television, SVT) broadcasting companies in Sweden.

The Sámi parliament in Sweden is both a governmental authority and a democratically elected national body, representing the Sámi people in Sweden. Elections to the parliament is held every fourth year, with 9 226 individuals being eligible to vote in the 2021 elections.

Disclosure statement

The Public Health Agency of Sweden was responsible for the Swedish public health strategy during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Sámi parliament in Sweden is a democratically elected body mandated to act on behalf of the Sámi in Sweden. JPAS, LMN and MSS have had several commissioned research grants from Swedish authorities, including the Sámi parliament and the Public Health Agency. Projects finished during the last three years include: “A basis for national strategy in the area of mental health and suicide prevention” (JPAS and MSS: Sámi parliament, dnr 1.3.8-2020-1074), “A collective description of various health outcomes among the Sami in Sweden” (JPAS, LMN and MSS: the Public Health Agency of Sweden, dnr 01401- 2021.2.3.2), “Violence against Sámi women” (JPAS, LMN and MSS: Sámi parliament, Dnr 2021-1809) and “Follow-up of health among national minorities and the Indigenous Sami people” (JPAS and MSS: the Public Health Agency of Sweden, dnr 01700-2023). OS is a former elected member to the Sámi parliament, 2013-2017 and 2017-2021.

References

- [1].Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran K, et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature. 2020;584(7821):430–11. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2521-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Anderson I, Robson B, Connolly M, et al. Indigenous and tribal peoples’ health (the lancet–lowitja institute global collaboration): a population study. Lancet. 2016;388(10040):131–157. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00345-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Gracey M, King M.. Indigenous health part 1: determinants and disease patterns. Lancet. 2009;374(9683):65–75. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60914-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].King M, Smith A, Gracey M. Indigenous health part 2: the underlying causes of the health gap. Lancet. 2009;374(9683):76–85. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60827-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Curtice K, Choo E. Indigenous populations: left behind in the COVID-19 response. Lancet. 2020;395(10239):1753. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)31242-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Young TK, Broderstad AR, Sumarokov YA, et al. Disparities amidst plenty: a health portrait of indigenous peoples in circumpolar regions. International Journal Of Circumpolar Health. 2020;79(1):1805254. doi: 10.1080/22423982.2020.1805254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hansen KL. Access to health services by indigenous peoples in the Arctic region. State World’s Indigenous Peoples: United Nations. 2016. doi: 10.18356/6c96c7f1-en [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Young TK, Chatwood S. Health care in the north: what Canada can learn from its circumpolar neighbours. CMAJ. 2011;183(2):209–214. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.100948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Arctic Council . COVID-19 in the Arctic: briefing document for senior arctic officials. Tromsø, Norway: Arctic Council Secretariat; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Petrov AN, Welford M, Golosov N, et al. Lessons on COVID-19 from indigenous and remote communities of the Arctic. Nat Med. 2021;27(9):1491–1492. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01473-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Petrov AN, Welford M, Golosov N, et al. The “second wave” of the COVID-19 pandemic in the Arctic: regional and temporal dynamics. International J Circumpolar Health. 2021;80(1):1925446. doi: 10.1080/22423982.2021.1925446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Petrov AN, Welford M, Golosov N, et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics of the COVID-19 pandemic in the arctic: early data and emerging trends. International J Circumpolar Health. 2020;79(1):1835251. doi: 10.1080/22423982.2020.1835251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Young TK, Bjerregaard P. Towards estimating the indigenous population in circumpolar regions. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2019;78(1):1653749. doi: 10.1080/22423982.2019.1653749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Sámediggi . Hälsopolitiskt handlingsprogram [Health policy action program]. Kiruna, Sweden: Sámediggi [Sámi Parliament in Sweden]; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [15].SOU . 2017:60. Nästa steg? Förslag för en stärkt minoritetspolitik [the next step? Proposals for a strengthened minority policy]. Stockholm, Sweden: Kulturdepartementet [Ministry of Culture]; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hunt P. Report of the special rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, Paul Hunt - MISSION to SWEDEN; 2007.

- [17].Nilsson LM, San Sebastian M, Stoor JP. The health experience of the COVID-19 pandemic among the Sámi in Sweden: A cross-sectional comparative study. Arct Yearb. Special Issue: Arctic Pandemics. 2023;1–13 . [Google Scholar]

- [18].Dresse MT, Stoor JP, San Sebastian M, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with healthcare avoidance during the COVID-19 pandemic among the Sámi in Sweden: the SámiHET study. International Journal Of Circumpolar Health. 2023;82(1):2213909. doi: 10.1080/22423982.2023.2213909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Spence J, Krishnan SSV. The state of research focused on COVID-19 in the Arctic: a meta-analysis. Arct Yearb. Special Issue: Arctic Pandemics. 2023;1–13. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Braun V, Clarke V, Terry G, et al. Thematic Analysis. In: Liamputtong P, editor. Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences. Springer Singapore: Singapore; 2019. p. 843–860. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Res in Phychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kvernmo S, Strøm Bull K, Broderstad A, et al. In: Proposal for ethical guidelines for sámi health research and research on sámi human biological material. Karasjok, Norway: Sámediggi [Sámi Parliament of Norway]; 2018. p. 50. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Lavoie J, Stoor JP, Cueva K, et al. Indigenous engagement in health research in circumpolar countries: an analysis of existing ethical guidelines. Int Indig Policy J. 2022;13(1). doi: 10.18584/iipj.2022.13.1.10928 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Ernst M, Niederer D, Werner AM, et al. Loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Am Psychol. 2022;77(5):660–677. doi: 10.1037/amp0001005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Aartsen M, Rothe F. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on social isolation and loneliness: A Nordic research review. Helsinki, Finland: Nordic Welfare Centre; 2023. p. 48. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Sámiediggie/Samiskt språkcentrum . Lägesrapport: De samiska språken i Sverige 2020 [Status report: The Sámi languages in Sweden 2020]: Sámiediggie/Samiskt språkcentrum; 2021.

- [27].Sámedigge/Samiskt språkcentrum . Lägesrapport: De samiska språken i Sverige 2021 [Status report: The Sámi languages in Sweden 2021]: Sámedigge/Samiskt språkcentrum; 2021.

- [28].Saemiedigkie/Gïelejarnge . Lägesrapport: De samiska språken i Sverige 2022 [Status report: The Sámi languages in Sweden 2022]. Saemiedigkie/Gïelejarnge; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Sevä T. Pandemins effekter på det samiska kulturlivet. Sammanställning av en undersökning bland samiska kulturaktörer och kulturutövare [The effects of the pandemic on Sámi cultural life. Compilation of a survey among the Sami cultural actors and cultural practitioners]. Kiruna, Sweden: Sametinget [the Sámi parliament in Sweden]; 2021. p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- [30].OECD . Linking the indigenous sami people with regional development in Sweden. Paris, France: OECD PUblishing; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Mikaelsson S. Samiska företagares möjligheter till coronastöd är orättvisa [Sámi entrepreneurs’ opportunities for corona support are unfair]: Sametinget. 2021. Available from: https://www.samediggi.se/158434

- [32].UN General Assembly . United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples: resolution / adopted by the General Assembly; 2007.

- [33].Akearok GH. Understanding the power of community during COVID-19. Arct Yearb. Special Issue: Arctic Pandemics. 2023;1–4. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Council of Yukon First Nations Alatini M, Johnston K, et al. Indigenous approaches to public health: Lessons learned from Yukon First Nation responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. Arct Yearb. Special Issue: Arctic Pandemics. 2023;1–21. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Fleury K, Chatwood S. Canadian Northern and Indigenous health policy responses to the first wave of COVID-19. Scand J Public Health. 2022;0(0):14034948221092185. doi: 10.1177/14034948221092185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Long R, Ford S, Crump J. Community responses to the COVID-19 pandemic in inuit nunaat. Arct Yearb. Special Issue: Arctit Pandemics. 2023;1–21. [Google Scholar]