Between 30 and 35 children undergoing heart surgery at Bristol Royal Infirmary died between 1991 and 1995 who would probably have survived if treated elsewhere, the long awaited report into children's heart surgery at Bristol has concluded.

These “excess” deaths took place in a unit where mortality at the time for children aged under 1 was probably double that for England as a whole, and even higher for neonates. Around a third of children who underwent open heart surgery received less than adequate care.

The inquiry report, published last week, painted a picture of a flawed system of care with poor teamwork between professionals, “too much power in too few hands,” and surgeons who lacked the insight to see that they were failing and to stop operating.

But the failings were not those of the surgeons alone. An expert review of 80 cases carried out for the inquiry showed inadequacies at every point, from referral to diagnosis, surgery, and intensive care.

The physical setup was “dangerous,” with surgeons on one site—at the Royal Infirmary—and paediatric cardiologists several hundred metres away at the children's hospital. The operating theatre and intensive care unit were on different floors, and children had to be transported by a lift that could be called at any time by others.

The inquiry—chaired by Ian Kennedy, professor of health law, ethics, and policy at University College London—acknowledged that those working with the children were caring and dedicated. But “some lacked insight and their behaviour was flawed.”

It said: “To a very great extent, the flaws and failures of Bristol were within the hospital, its organisation and culture, and within the wider NHS as it was at the time. That said, there were individuals who could and should have acted differently.”

There was a mindset of “professional hubris,” that, as a teaching hospital, Bristol had to be at the leading edge. Clinicians were actively collecting and discussing data but were quick to deny any adverse inferences drawn from the data.

The senior management was close to the “old guard” of clinicians and supported them. There was a “club culture,” with insiders and outsiders. The style of management had a punitive element, and the environment did not make speaking out or openness safe or acceptable.

NHS is still failing to learn

The most significant change needed, the 461 page report said, is a change in the culture of the NHS.

A raft of reforms by government and professional bodies are already in train as a result of the Bristol debacle. But Professor Kennedy said: “We must guard against an attack of complacency breaking out too early. We have taken account of what the government has done, and still we say there is much to be done on a lot of fronts.”

The report warned: “The NHS is still failing to learn from the things that go wrong and has no system to put this right. This must change. Even today, it is not possible to say, categorically, that events similar to those which happened at Bristol could not happen again in the UK—indeed, are not happening at this moment.”

The report said that half of the recommendations could be implemented with no or relatively modest expenditure. But it warned that sustained additional funding must be forthcoming annually to achieve the service that patients should expect.

Among the recommendations is a call for a council for the quality of health care, independent of government, to include the new bodies set up to oversee standards of health care, such as the National Institute for Clinical Excellence, the Commission for Health Improvement, and the planned National Patient Safety Agency.

Another overarching council would bring together the General Medical Council and the other bodies regulating healthcare professionals.

Bolsin “right to persist”

The problems at Bristol were eventually brought to light by a whistleblower, consultant anaesthetist Stephen Bolsin. He said his part in the saga prevented him from finding another job in Britain, and he now works as head of anaesthesia at Geelong Hospital near Melbourne, Australia.

“He persisted and he was right to do so,” said the report, which recommended that whistleblowers who report concerns to the National Patient Safety Agency should have protection under the Public Interest Disclosure Act.

The report called for a new culture of openness, with a non-punitive system for reporting serious incidents. It recommended abolition of clinical negligence litigation, which is part of the culture of blame and secrecy, replacing it with an administrative scheme for awarding compensation.

Stephen Thornton, chief executive of the NHS Confederation, said: “Bristol has proved an extraordinary catalyst to improve standards. We may not be able to give absolute guarantees that Bristol-type mistakes will never occur, but we should be able to guarantee that they do not persist in the way they did at Bristol.”

Ian Bogle, chairman of the BMA's council, said: “We are absolutely determined to see that some good comes out of the tragedy by working with government and with colleagues throughout the NHS to detect problems at an early stage, to provide better information for parents and patients, and to improve safety and quality.” (See editorial on p 179)

Learning from Bristol is available from the Stationery Office, price £32. (summary and recommendations, £8.) And at www.bristol-inquiry.org.uk

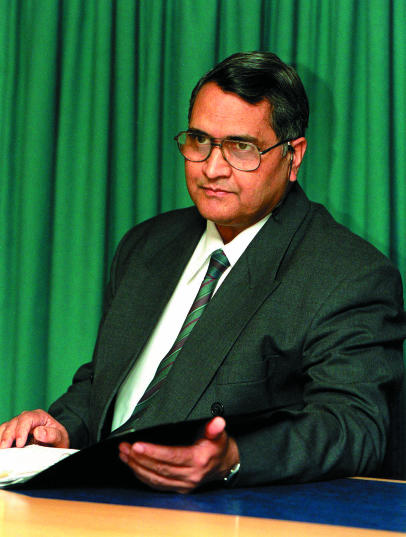

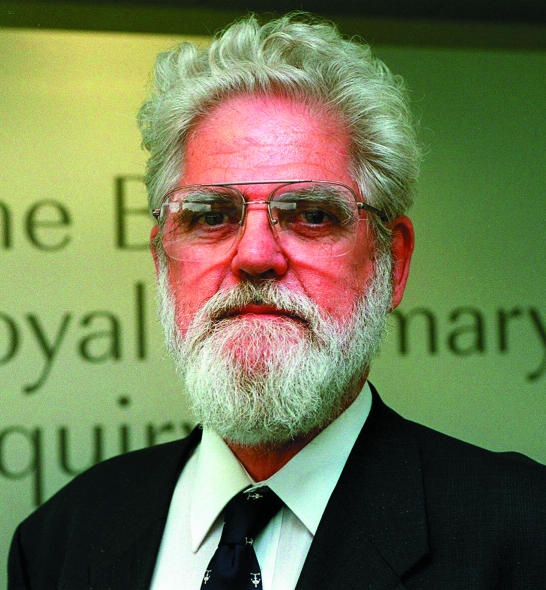

Figure.

SOUTHWEST NEWS SERVICE

Parents at the Bristol heart inquiry

Figure.

SOUTHWEST NEWS SERVICE

SOUTHWEST NEWS SERVICE

SOUTHWEST NEWS SERVICE

From left: James Wisheart, John Roylance, and Janardan Dhasmana