Abstract

Background

In addition to other variables associated with PRP injections for Knee Osteoarthritis (OA), some confusion exists about the role of exogenous activators. The current study looks at matched groups getting PRP injections with or without activator (Calcium gluconate) in early knee OA patients.

Methods

Patients of early OA knee meeting inclusion criteria were randomly divided into 2 groups; Group A (43 patients) received 8 ml PRP injection alone, and Group B (48 patients) received 8 ml PRP along with 2 ml Calcium gluconate as activator. The patients were evaluated at baseline, 6 weeks, 3 months and 6 months for WOMAC Pain and Total WOMAC scores; secondary variables assessed were VAS score and patient satisfaction.

Results

The baseline characteristics of both groups were comparable. Leucocyte-depleted PRP with 5 times concentration and average absolute platelet numbers of 7.144 billion per knee was injected. Mean Pain WOMAC scores decreased in both groups from baseline (group A—8.68, group B—9.09) to final follow-up (group A—4.67, group B—5.11). Similarly, Mean Total WOMAC scores decreased from baseline (group A—37.81, group B—37.41) to (group A—21, group B—21.36) at the final follow-up in both groups. There was no significant difference between both groups, and both showed similar trends. Similar findings were noted for VAS scores. Patient satisfaction was also not different (group A, 90.69%, group B, 89.58%) at the end of 6 months.

Conclusion

Our study concluded doubtful role of adding exogenous activator to PRP preparation.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s43465-024-01159-7.

Keywords: Osteoarthritis, Knee, Platelet-rich plasma, Activators

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) knee is a clinically heterogeneous disease characterized by progressive articular cartilage destruction and patho-physiological changes in the synovial membrane [1]. Different pathomechanisms of OA knee have been targeted in the treatment, and Platelet Rich Plasma (PRP) has proven its role in the last decade, emerging as a potential frontrunner in the management of early disease i.e. Kellgren Lawrence stage 1 and 2 knee osteoarthritis [2]. Autologous PRP contains multiple growth factors which play a pivotal role in maintaining joint homeostasis; some anti-inflammatory effects and possibly chondral remodelling may have the potential to modify the disease progress [3–6]. Multiple RCTs and meta-analyses have established the efficacy of PRP in providing clinically significant symptomatic relief in the management of early OA knee and have also established its superiority over other intra-articular injections [4, 5]. Nevertheless, many variables pertaining to PRP with respect to dose, frequency, type of PRP and the need for activator still need to be defined precisely.

Of late, research into PRP in knee OA is being focussed on answering these questions. There have been studies emerging that favour multiple PRP injections over single injections, and Leucocyte Poor (LP) PRP seems to be preferred over Leucocyte Rich (LR) PRP owing to fewer local adverse reactions [7]. The need for additional exogenous activators along with PRP is still vaguely documented; some authors have used PRP with an activator [4–7] and some of them have not used an activator [8–10] and there is no established consensus as to what is the right approach. Proponents of activator use believe that growth factor release from alfa granules in platelets is facilitated by activator. On the other hand, researchers who do not use activator argue that platelets in PRP get spontaneously activated on coming in contact with native collagen present in the connective tissue [7, 8]. So far, there are not any direct comparative studies evaluating the superiority of using PRP with or without activators. In the present study, our primary objective was to compare PRP with activator against PRP without activator, with the aim of addressing this crucial parameter concerning PRP use in Knee OA.

Methodology

Trial Design

This was a prospective, triple-blinded, randomized clinical trial comparing two treatment groups with an allocation ratio of 1:1.15, after adequate Institutional Ethical Board clearance. The CONSORT guidelines (2010) were duly followed during this randomized control trial [11].

Sample Size

A priori analysis was conducted based on sample size calculations from prior studies by patel et al. and Görmeli et al. [4, 5]; a mean of 12 weeks based on the WOMAC pain subscale demonstrated that to identify a 4-point difference between groups using an alpha value of 0.05 and power set at 0.8, a minimum of 37 patients would be required for each group.

Participants

Patients attending the Orthopaedics Outpatient Department during the study period from July 2018 to May 2019 were included in the study. A total of 187 patients who had early Knee Osteoarthritis as diagnosed by American College of Rheumatology criteria [12] and staged as per Kellgren and Lawrence staging [13] were screened and assessed for eligibility. 95 patients out of 187 patients met the pre-defined inclusion criteria, which were K.L grade 1 or 2 without significant deformity (less than 10 degrees of varus/valgus; less than 10 degree flexion deformity). 92 patients were excluded based upon the exclusion criteria which were OA secondary to inflammatory arthritis, crystal arthropathy, generalized osteoarthritis, associated metabolic disease, co-existing back pain, advanced and late stages of OA, patients receiving intra articular injections in past 3 months, patients with history of thrombocytopenia, patients on anti-coagulant or anti-platelet treatment. Patients who declined to participate (informed consent) were also excluded Out of 95 subjects selected only 91 were randomized as 4 subjects were declared unfit on the day of intervention.

Randomization

The participants were randomly divided by computer-generated random number chart into two groups (Group A and B). Group A had 43 patients (79 knees) and group B had 48 patients (91 knees). Allocation concealment was done as randomization was done by a non-clinical staff and the intervener was not aware of the group under which the patient would come until the day of intervention. Non-clinical staff performed the randomization and a single surgeon performed the standard injection procedure and was not involved in any other aspect of patient recruitment or the study follow-up. The patient recruitment, follow-up, results and analysis were performed by the primary research team. Volunteer participants, the outcome scores evaluator and the statistician were all blinded and unaware of the treatment received by Group A and Group B. The surgeon who provided the injection was aware of the groups, and revealed the nature of treatment received by both groups after the data results and conclusion.

Interventions and Groups

Group A (43 patients) received 8 ml of PRP injection.

Group B (48 patients) received 8 ml of PRP along with 2 ml of activator (Calcium gluconate).

PRP Preparation Technique

The platelet-rich plasma was prepared by the Department of Transfusion Medicine on the day of the procedure. Under aseptic precautions, 50 ml blood was drawn from the anti-cubital vein of the patient and collected in a blood bag (Terumo Penpol Limited, Trivandrum, India) with CPDA (Citrate–Phosphate–Dextrose and Adenine) as anticoagulant preservative solution. Constant efforts were made throughout to avoid irritation and trauma to platelets which were in a resting state. The whole blood was then transferred from the blood bag into sterile tube using a blood transfusion set, inside a biosafety cabinet, class IIA (BIOAIR Safe flow1.2, Euroclone, Siziano, Italy). PRP was prepared with double spin platelet pellet method. The first spin was for 15 min at 1300 rpm (280 g) using a tabletop centrifuge (Remi lab instruments, India). The supernatant plasma (which has all the platelets and few WBCs) was extracted through a pipette and transferred to another sterile tube. It was then subjected to a second spin at 2300 rpm (885 g) for 5 min. The whole platelets settled down at the bottom as a platelet pellet. The supernatant platelet-poor plasma at the top was pipetted out leaving behind 16 ml of plasma. Re-suspension of platelet button was done with the remaining plasma and the final PRP product was dispensed in two 10 ml syringes (8 ml PRP per knee). Total leucocyte count and platelet count were measured from the patient’s peripheral blood as well as in the final PRP. The PRP was leucocyte depleted PRP and platelets concentrated five times above baseline.

Inj. Calcium Gluconate was diluted with Normal Saline (1:7) to make calcium content (M/40). 2 ml of diluted calcium gluconate (M/40) was dispensed in a separate syringe. 2 ml calcium gluconate for 8 ml of PRP (1:4 ratio).

Intra-articular Injection

The injections were given within 30 min of preparation. The patients were made to lie down comfortably in supine position with the knee in full extension. Under aseptic precautions, the PRP injections were given with an 18 gauge needle into the suprapatellar pouch through a superolateral approach. In Group B, the needle was retained in place and 2 ml of calcium gluconate was additionally administered. The knees were made to flex and extend 10 times, and the patients were discharged after 30 min of observation. Post PRP injection, all patients were subjected to a cooling off period of 1 week for inflammation to subside inside the knee joint. All patients were then subjected isometric quadriceps exercises; Vastus Medialis Obliquus strengthening protocol and hip abductor exercises under supervision.

Outcome Measures

The primary efficacy criterion was change in joint pain from baseline, measured using the WOMAC pain subscale. Secondary efficacy variables included changes in WOMAC total score. The WOMAC parameters were measured before injection and at 6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months after injection. Patients were also assessed for pain by VAS and for satisfaction (satisfied, partly satisfied, not satisfied) at the end of 6 months. Adverse effects related to treatment were also recorded for their nature, time of onset, duration, and severity.

Statistical Analysis

Data acquired through questionnaires (WOMAC pain scores, WOMAC total scores and VAS scores) was entered into Microsoft Excel sheet. All the errors were removed from the data to finalize a master sheet. The finalized master sheet was exported to Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS v.21) and then analyzed for various tests considering the variables acquired through data collection. Measurable data were tested for normality using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The normally distributed parameters were compared for their means using the Analysis of Variance followed by post hoc tests like ‘Student Newman Keul’s’ and ‘Dunnett t’ procedures. Non-normal data were expressed as median and inter-quartile range and their distribution for two groups was compared using Mann–Whitney U Test and Wilcoxon’s Signed Rank tests. The association of various Categorical/Classified data including complications, within the two groups were analyzed using Chi-square Test.

Within groups, the data on pre-levels and post-levels was compared using Student’s t-test and paired or Wilcoxon Signed Rank test as applicable. Their difference (Pre-level–Post-level) was compared using Student’s t-test or Mann Whitney U Test as applicable. The data were also depicted graphically using Histograms and bar diagrams. The data at various follow-ups were analyzed using Repeated Measure Anova followed by post hoc tests. A ‘p’ value of <0.05 was considered significant in all tests.

Results

One patient was lost to follow-up from group A. Analysis of 42 patients from group A and 48 patients from group B was possible (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

CONSORT flow diagram

There was no difference in two groups in terms of baseline characteristics, namely age, sex, BMI and baseline WOMAC scores (Table 1). PRP in both groups were comparable in terms of their baseline characteristics (Table 2). The PRP was leucocyte depleted PRP (mean leucocyte levels of PRP = 2300/μl) with leucocytes less than baseline (mean leucocyte levels of whole blood = 7500/μl) and the platelets concentrated 5 times the base line, and the absolute number of platelets injected per knee was 6.79 billion platelets in group A and 7.144 billion platelets in group B.

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline variables between group A and group B

| Group A (PRP injection; n = 79) | Group B (PRP + activator injection; n = 91) | p value (between groups) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD | 52.23 ± 7.496 | 51.33 ± 8.578 | 0.598 |

| Sex, M:F | 7:36 | 7:41 | 0.541 |

| BMI, mean ± SD | 22.995 ± 1.231 | 23.046 ± 1.148 | 0.840 |

| Osteoarthritis | |||

| KL Grade 1 | 5 (6.3%) | 1 (1.1%) | 0.0983 |

| 2 | 74 (93.7%) | 80 (98.9%) | |

| WOMAC pain score, mean ± SD | 8.68 ± 1.057 | 9.09 ± 0.927 | 0.901 |

| WOMAC total score, mean ± SD | 6.06 ± 0.667 | 6.11 ± 0.674 | 0.652 |

| VAS score, mean ± SD | 37.81 ± 8.911 | 37.31 ± 8.059 | 0.700 |

Table 2.

Comparing baseline PRP variables

| Group A | Group B | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of spin | Double spin | Double spin | – |

| Platelet concentration, mean ± SD (× 106/ml) | 849.81 ± 395.544 | 893.02 ± 413.534 | 0.613 |

| Increase in Platelet conc from baseline, mean ± SD | 4.959 ± 2.373 | 4.655 ± 1.443 | 0.457 |

| Absolute number of platelets injected | 6.79 billion | 7.14 billion | 0.671 |

Outcome Scores

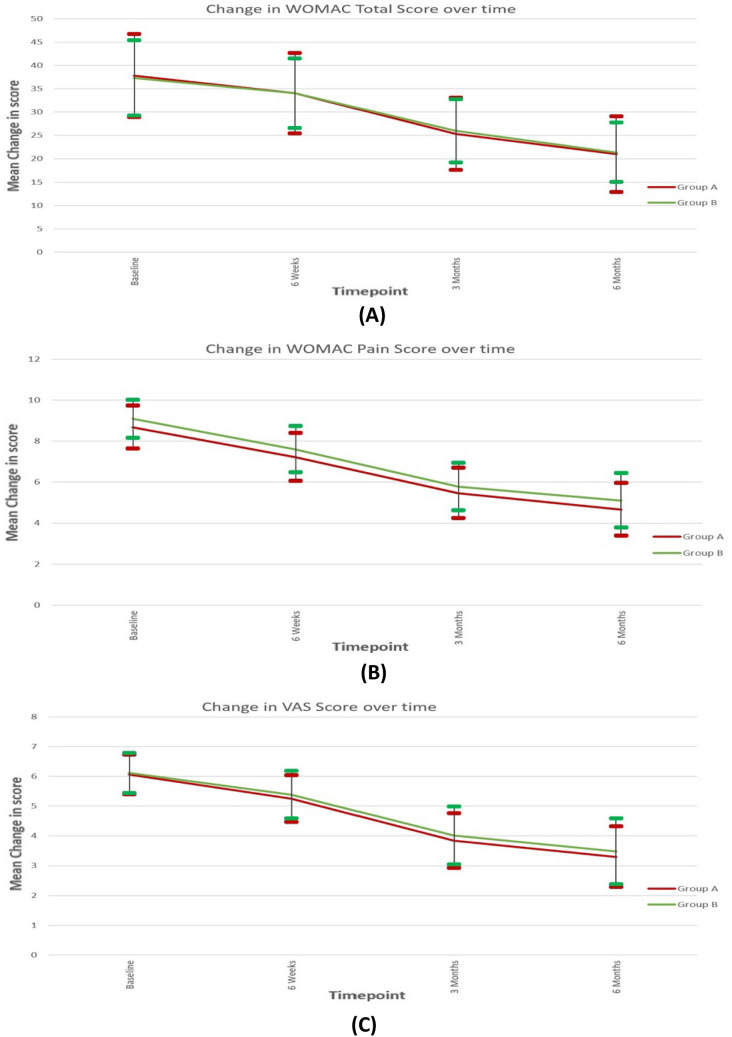

A statistically significant improvement in all parameters of WOMAC scores were documented in both group A and B compared to baseline and both groups followed similar trend (Fig. 2A). The mean WOMAC pain score decreased from baseline over sequential follow-up till final follow-up, and the mean WOMAC pain score was lowest at the final follow-up at 6 months (Table 3has details of mean scores and p values). There was a continuous trend of improvement. The change in WOMAC Pain scores was statistically significant at all time frames for both group A and B. However, there was no difference between the groups at any time frame.

Fig. 2.

Graph depicting trend change in total WOMAC scores, WOMAC pain scores and VAS scores over sequential follow-up between group A and B

Table 3.

Comparison between two groups in terms of mean values of WOMAC pain, WOMAC total and VAS score at different time frame

| WOMAC pain score | WOMAC total score | VAS score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | Group B | Group A | Group B | Group A | Group B | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Baseline | 8.68 (1.05) | 9.09 (0.93) | 37.80 (8.86) | 37.31 (8.06) | 6.06 (0.66) | 6.11 (0.67) |

| 6 weeks | 7.22 (1.17) | 7.60 (1.13) | 34.02 (8.62) | 34.04 (7.43) | 5.25 (0.79) | 5.38 (0.80) |

| 3 months | 5.47 (1.23) | 5.78 (1.16) | 25.29 (7.73) | 25.96 (6.75) | 3.84 (0.92) | 4.01 (0.97) |

| 6 months | 4.67 (1.28) | 5.11 (1.32) | 20.97 (8.11) | 21.36 (6.36) | 3.30 (1.02) | 3.48 (1.11) |

| p value for change in outcome parameter over time within each group (Friedman Test) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Overall p value for comparison of change in outcome parameter over time between the two groups (Generalized estimating equations) | 0.690 | 0.116 | 0.723 | |||

Friedman Test was used to assess change in a particular outcome measure over time within that group

The total WOMAC scores also followed a similar trend in both groups A and B and decreased from baseline till final follow-up with a continuous trend of improvement with the lowest mean value at final follow-up (Fig. 2B, Table 3). The change in total WOMAC scores was statistically significant at all time frames for both groups A and B, there was no difference between the groups at any time frame.

VAS scores also followed a similar trend in both groups and there was continuing trend of improvement till last follow-up (Fig. 2C). The change in VAS scores over time was statistically significant in both groups, and there was no difference between the groups. Patient satisfaction with the procedure and whether they would recommend the procedure for others was assessed at the end of final follow-up. In our study, 90.6% subjects in group A and 89.5% subjects in group B were satisfied with the intervention.

The mean percentage improvement at final follow-up was compared to baseline. Improvement in Total WOMAC and WOMAC pain score in group A was 45.63 and 44.84%, respectively, and in group B was 43.65 and 42.48%, respectively. We calculated MCID [14] for Indian population by comparing the minimum difference required in the WOMAC pain and WOMAC total score between baseline and final follow-up (6 months), using patient satisfaction as the outcome variable. Our data (details mentioned in Table 4) showed that the improvement in WOMAC pain was 3.99 and 3.98 (group A and group B); and WOMAC total scores was 17 and 15.95 (group A and group B), respectively, which was above the calculated MCID values for Indian population (3.9 for WOMAC pain score and 12 for WOMAC Total score.)

Table 4.

Comparison between two groups in terms of percentage change and absolute change of WOMAC pain, WOMAC Total and VAS score at different time frames

| Outcome parameter | Timepoint comparison | Change in outcome parameters from baseline to follow-up timepoints | Comparison of the two groups in terms of difference of outcome parameters from baseline to follow-up timepoints | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group: A | Group: B | ||||||||

| Mean (SD) of absolute change | Mean (SD) of % Change | p value of change within group | Mean (SD) of absolute change | Mean (SD) of % change | p value of change within group | p value of absolute change | p value of % change | ||

| WOMAC pain score | 6 weeks—baseline | −1.45 (0.69) | −16.8% (7.9) | <0.001 | −1.48 (0.86) | −16.3% (9.2) | <0.001 | 0.614 | 0.751 |

| 3 months—baseline | −3.20 (1.00) | −37.0% (10.5) | <0.001 | −3.31 (1.09) | −36.3% (11.1) | <0.001 | 0.516 | 0.706 | |

| 6 months—baseline | −3.99 (1.14) | −46.1% (11.8) | <0.001 | −3.98 (1.36) | −43.7% (13.6) | <0.001 | 1.000 | 0.295 | |

| WOMAC total score | 6 weeks—baseline | −3.78 (1.87) | −10.2% (5.2) | <0.001 | −3.26 (2.02) | −8.7% (5.0) | <0.001 | 0.052 | 0.043 |

| 3 months—baseline | −12.51 (4.13) | −33.4% (9.1) | <0.001 | −11.35 (4.11) | −30.5% (9.6) | <0.001 | 0.107 | 0.039 | |

| 6 months—baseline | −17.00 (5.17) | −45.5% (11.0) | <0.001 | −15.95 (6.05) | −42.5% (12.8) | <0.001 | 0.284 | 0.152 | |

| VAS score | 6 weeks—baseline | −0.81 (0.55) | −13.4% (8.8) | 0.001 | −0.73 (0.62) | −11.8% (9.8) | 0.004 | 0.295 | 0.244 |

| 3 months—baseline | −2.22 (0.76) | −36.9% (12.1) | <0.001 | −2.10 (0.82) | −34.6% (13.3) | <0.001 | 0.345 | 0.237 | |

| 6 months—baseline | −2.75 (0.93) | −45.6% (14.6) | <0.001 | −2.63 (1.04) | −43.2% (16.4) | <0.001 | 0.401 | 0.332 | |

Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare difference between two groups for a particular timepoint

Pain and stiffness were the major self-limiting complications following injections that were noticed in post injection period and these lasted from 2 to 7 days with an average period of 4 days. In group A, 95.3% subjects had pain and 27.3% had stiffness. In group B, 95.8% subjects had pain and 72.7% had stiffness. Both the groups had similar self-limiting adverse reaction profile, but there was significantly more stiffness in group B (p = 0.004).

Discussion

Many RCTs [4, 5, 9, 14] and meta-analyses [15–18] provide evidence of statistically significant improvement in early OA knee in terms of pain and functional improvement with PRP use, and the present study also documents the clinically significant benefits in outcome scores above the MCID [14].

In our study, we have aimed to define whether there is any added role of activator along with PRP in terms of clinical improvement. The term “activation of PRP” revolves around 2 key processes that are initiated during PRP preparation: firstly, release of growth factors by degranulation of alpha granules in platelets, and secondly matrix formation initiated by fibrinogen cleavage, a clotting process which allows the formation of a platelet gel, and therefore, confines the secretion of molecules to the chosen site. Exogenous activation refers to use of activator along with PRP such as Bovine or autologous thrombin, 10% CaCl2 or a combination. Calcium chloride is the most common activator and has been used in the majority of clinical studies [4, 6, 7]. The other type of activation is endogenous activation and it happens when platelets come in contact with tissue inside the joint. The proponents of using PRP alone for injection without an exogenous activator [8–10] rely on this endogenous activation of PRP. The use of these activators leads to an increase in level of GFs that is immediate and sustained up to 24 h. Cavalo et al. compared various activation methods and also noticed increased levels of growth factors to correlate with marked clinical improvement [19].

There is no established consensus about use of additional exogenous activator along with PRP as it has just been a practice for some researchers to use PRP with activator [4–7] and others to use PRP without activator. There are no studies directly comparing these two treatment groups so far and ours is the first RCT focusing on this specific research question. We found no statistically significant difference between PRP with activator and PRP without activator, in terms of pain relief and functional improvement, and hence we conclude that there is no added advantage of adding activator to PRP.

There are a lot of variables concerning PRP and there is always a discussion for standardizing the PRP preparations. Classification for various PRP types by Mishra et al. [20], DeLong et al. [21] and others have taken into account the need for exogenous activators apart from platelet concentration and presence of leucocytes. The results of our study are significant as they clear the confusion and address one important aspect of standardization of PRP product.

We have used 8 ml PRP for each knee with 5 times platelet concentration compared to baseline. The mean platelet count of the final product was 872.60 × 103/μL (849.81 × 103/μL in group A and 893.02 × 103/μL in group B) and the mean absolute number of platelets injected per knee was 6.79 billion in group A and 7.144 billion in group B. We refer to this PRP preparation and dose as Superdose PRP [22]. Recent studies have noted the dose to be crucial and critical for long-term clinical efficiency and Bansal et al. have observed 10 billion platelets as the absolute number essential for sustained clinical effects [23].

We also noted a significant percentage of patients have self-limiting short-term complications (pain, stiffness and swelling) in both groups A and B, which were more than that noted in a previous study done by Patel et al. [4]. These may be due to the higher dose of the PRP (8 ml) used here, as compared to other studies that have used 4 ml PRP [9, 19]. Complications were, however, mild and self-limiting in nature.

We also observed a continuing trend of improvement in the WOMAC parameters (WOMAC pain and WOMAC total scores) from 3 to 6 months follow-up, contrary to previous published studies with weaning effects at 6 months compared to 3 months [4, 24, 25]. This could be attributed to higher concentration of PRP and higher absolute platelet count delivered in our Superdose PRP compared to previous studies.

Younger age and lower BMI were correlated with better improvement in WOMAC total scores and pain scores. Similar findings were observed by Kon et al. [26].

The highlight of the study is that it is a triple-blind RCT where the patients, outcome evaluators and statisticians were all blinded. There are certain limitations of the study, such as the small sample size (as both groups were intervention groups with established clinical benefits). In such a scenario, we may need a larger sample size to detect possible minor differences between these groups (if any). Another limitation is the fact that this is a uni-centric study which needs to be explored and extrapolated by the fellow orthopedic surgeons to study the utility of an exogenous activator for PRP usage.

Conclusion

Our study, while reconfirming the positive role of PRP in early Knee OA, has shown that there is no added advantage of using an exogenous activator along with PRP. This eliminates one of the variables that tend to confuse surgeons and physicians when they’re comparing outcomes related to PRP administration.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Funding

No funding was required.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author would like to declare there are no potential conflicts of interest.

Ethics Approval

This kind of study does not require ethical approval.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wearing SC, Hennig EM, Byrne NM, Steele JR, Hills AP. Musculoskeletal disorders associated with obesity: A biomechanical perspective. Obesity Reviews: Official Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2006;7(3):239–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langworthy MJ, Saad A, Langworthy NM. Conservative treatment modalities and outcomes for osteoarthritis: The concomitant pyramid of treatment. The Physician and Sportsmedicine. 2010;38(2):133–145. doi: 10.3810/psm.2010.06.1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pietrzak WS, Eppley BL. Platelet rich plasma: Biology and new technology. The Journal of Craniofacial Surgery. 2005;16(6):1043–1054. doi: 10.1097/01.scs.0000186454.07097.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel S, Dhillon MS, Aggarwal S, Marwaha N, Jain A. Treatment with platelet-rich plasma is more effective than placebo for knee osteoarthritis: A prospective, double-blind, randomized trial. American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2013;41(2):356–364. doi: 10.1177/0363546512471299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Görmeli G, Görmeli CA, Ataoglu B, Çolak C, Aslantürk O, Ertem K. Multiple PRP injections are more effective than single injections and hyaluronic acid in knees with early osteoarthritis: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2017;25(3):958–965. doi: 10.1007/s00167-015-3705-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li M, Zhang C, Ai Z, Yuan T, Feng Y, Jia W. Therapeutic effectiveness of intra-knee-articular injection of platelet-rich plasma on knee articular cartilage degeneration. Journal of Reparative and Reconstructive Surgery. 2011;25(10):1192–1196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Filardo G, Kon E, Pereira Ruiz MT, Vaccaro F, Guitaldi R, Di Martino A, et al. Platelet-rich plasma intra-articular injections for cartilage degeneration and osteoarthritis: Single- versus double-spinning approach. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2012;20(10):2082–2091. doi: 10.1007/s00167-011-1837-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duymus TM, Mutlu S, Dernek B, Komur B, Aydogmus S, Kesiktas FN. Choice of intra-articular injection in treatment of knee osteoarthritis: Platelet-rich plasma, hyaluronic acid or ozone options. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2017;25(2):485–492. doi: 10.1007/s00167-016-4110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spaková T, Rosocha J, Lacko M, Harvanová D, Gharaibeh A. Treatment of knee joint osteoarthritis with autologous platelet-rich plasma in comparison with hyaluronic acid. American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2012;91(5):411–417. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e3182aab72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raeissadat SA, Rayegani SM, Hassanabadi H, Fathi M, Ghorbani E, Babaee M, et al. Knee osteoarthritis injection choices: Platelet- rich plasma (prp) versus hyaluronic acid (A one-year randomized clinical trial) Clinical Medicine Insights: Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2015;8:1–8. doi: 10.4137/CMAMD.S17894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Journal of Pharmacology and Pharmacotherapeutics. 2010;1(2):100–107. doi: 10.4103/0976-500X.72352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Altman, R., Asch, E., Bloch, D., Bole, G., Borenstein, D., Brandt, K., et al. (1986). Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis. Classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee of the American Rheumatism Association. Arthritis & Rheumatology, 29 (8), 1039–49. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Kohn MD, Sassoon AA, Fernando ND. Classifications in brief: Kellgren-Lawrence classification of osteoarthritis. Clinical Orthopaedics. 2016;474(8):1886–1893. doi: 10.1007/s11999-016-4732-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tubach F, Wells GA, Ravaud P, Dougados M. Minimal clinically important difference, low disease activity state, and patient acceptable symptom state: Methodological issues. Journal of Rheumatology. 2005;32(10):2025–2029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kon E, Mandelbaum B, Buda R, Filardo G, Delcogliano M, Timoncini A, et al. Platelet-rich plasma intra-articular injection versus hyaluronic acid visco supplementation as treatments for cartilage pathology: From early degeneration to osteoarthritis. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(11):1490–1501. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang K-V, Hung C-Y, Aliwarga F, Wang T-G, Han D-S, Chen W-S. Comparative effectiveness of platelet-rich plasma injections for treating knee joint cartilage degenerative pathology: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2014;95(3):562–575. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laudy ABM, Bakker EWP, Rekers M, Moen MH. Efficacy of platelet-rich plasma injections in osteoarthritis of the knee: A systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2015;49(10):657–672. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2014-094036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shen L, Yuan T, Chen S, Xie X, Zhang C. The temporal effect of platelet-rich plasma on pain and physical function in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery. 2017;12:16. doi: 10.1186/s13018-017-0521-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cavallo C, Roffi A, Grigolo B, Mariani E, Pratelli L, Merli G, et al. Platelet-Rich plasma: The choice of activation method affects the release of bioactive molecules. BioMed Research International. 2016;2016:6591717. doi: 10.1155/2016/6591717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mishra A, Harmon K, Woodall J, Vieira A. Sports medicine applications of platelet-rich plasma. Current Pharmaceutical Biotechnology. 2012;13(7):1185–1195. doi: 10.2174/138920112800624283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeLong JM, Russell RP, Mazzocca AD. Platelet-rich plasma: The PAW classification system. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(7):998–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2012.04.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel S, Gahlaut S, Thami T, Chouhan DK, Jain A, Dhillon MS. Comparison of conventional dose versus superdose platelet-rich plasma for knee osteoarthritis: A prospective, triple-blind, randomized clinical trial. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine. 2024;12(2):23259671241227863. doi: 10.1177/23259671241227863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bansal H, Leon J, Pont JL, Wilson DA, Bansal A, Agarwal D, et al. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) in osteoarthritis (OA) knee: Correct dose critical for long-term clinical efficacy. Science and Reports. 2021;11(1):3971. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-83025-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chouhan DK, Dhillon MS, Patel S, Bansal T, Bhatia A, Kanwat H. Multiple platelet- rich plasma injections versus single platelet-rich plasma injection in early osteoarthritis of the knee: An experimental study in a guinea pig model of early knee osteoarthritis. American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2019;47(10):2300–2307. doi: 10.1177/0363546519856605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dhillon MS, Patel S, Bansal T. Improvising PRP for use in osteoarthritis knee- upcoming trends and futuristic view. Journal of Clinical Orthopaedics and Trauma. 2019;10(1):32–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2018.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kon E, Buda R, Filardo G, Di Martino A, Timoncini A, Cenacchi A, et al. Platelet-rich plasma: Intra-articular knee injections produced favorable results on degenerative cartilage lesions. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2010;18(4):472–479. doi: 10.1007/s00167-009-0940-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Not applicable.