Abstract

Purpose

The sacroiliac joint (SIJ), a synovial joint with irregular surfaces, is crucial for stabilizing the body and facilitating daily activities. However, recent studies have reported that 15–30% of lower back pain can be attributed to instability in the SIJ, a condition collectively referred to as sacroiliac joint dysfunction (SIJD). The aim of this study is to investigate how the morphological characteristics of the auricular surface may influence the SIJ range of motion (ROM) and to examine differences in SIJ ROM between females and males, thereby contributing to the enhancement of SIJD diagnosis and treatment.

Methods

We measured SIJ ROM using motion-analysis cameras in 24 fresh cadavers of Korean adults (13 males and 11 females). Using three-dimensional renderings of the measured auricular surface, we investigated the correlations between the morphological characteristics of the auricular surface and the ROM of the SIJ.

Results

The SIJ ROM was between 0.2° and 6.7° and was significantly greater in females (3.58° ± 1.49) compared with males (1.38° ± 1.00). Dividing the participants into high-motion (3.87° ± 1.19) and low-motion (1.13° ± 0.62) groups based on the mean ROM (2.39°) showed no significant differences in any measurements. Additionally, bone defects around the SIJ were identified using computed tomography of the high-motion group. In the low-motion group, calcification between auricular surfaces and bone bridges was observed.

Conclusion

This suggests that the SIJ ROM is influenced more by the anatomical structures around the SIJ than by the morphological characteristics of the auricular surface.

Keywords: Sacroiliac joint, Sacroiliac joint ROM, Auricular surface, Morphological sex differences, Three-dimensional morphological analysis

Introduction

The sacroiliac joint (SIJ) is a highly stable joint that distributes loads to the lower extremities, helping maintain balance in the human body [1–9]. It enables various everyday movements, such as walking, sitting, and running. Several studies have reported that 15–30% of lower back pain is caused by instability in the SIJ [10–14]. This condition, known as sacroiliac joint dysfunction (SIJD), can be caused by various factors such as incorrect posture, trauma, pregnancy, and childbirth [15–17].

The SIJ is an articulation of the sacrum and the ilium connected by the anterior sacroiliac ligament, the interosseous sacroiliac ligament, and the posterior sacroiliac ligament [18]. The surface of the joint is typically L-shaped and is known as the “auricular surface” because it resembles an ear [19]. In the SIJ, the sacral auricular surface is covered largely by hyaline cartilage, creating a concave shape. In contrast, the iliac auricular surface is covered by fibrocartilage and has a convex shape [5, 20]. The SIJ is a synovial joint, but its auricular surface is not smooth and has an irregular texture, allowing it to interlock with the opposing surface [18, 21]. SIJ motions can be classified as nutation or counternutation. Nutation is the forward tilting of the sacrum and backward rotation of the ilium, while counternutation is the backward tilting of the sacrum and forward rotation of the ilium [8, 11, 19, 22–26]. The SIJ is characterized by irregularly articulated auricular surfaces. The anterior sacroiliac ligament, interosseous sacroiliac ligament, posterior sacroiliac ligament, sacrotuberous ligament, and sacrospinous ligament, which connect the sacrum and the ilium, provide stability by limiting motion [4, 10, 11].

Multiple studies have been conducted on the stability of the SIJ, its range of motion (ROM), and the characteristics of the auricular surface. In previous studies, the mean SIJ ROM was between 0.7° and 4° [24, 27–33]. One study found that the SIJ ROM was 0° in patients with pelvic and lumbar pain, while it was 2.1° in those without pain [34]. However, other studies found no significant difference in SIJ ROM between patients with and without pain [28]. Additionally, studies have been carried out on the size, shape [7, 20, 35–39] and degenerative changes of the auricular surface [38, 40–43]. Differences in shape of the auricular surface have been used to distinguish the sex of a skeleton [7, 25, 39, 42, 44]. However, few studies have investigated the relationships between SIJ ROM and the morphological characteristics of the auricular surface. The aim of this study is to investigate how the morphology of the auricular surface influences SIJ ROM and to identify any differences between females and males. The results are expected to contribute to the improvement of diagnosis and treatment of SIJD.

Materials and methods

The study was conducted using 24 fresh cadavers of adults Koreans (11 females and 13 males; mean age 81.6 [49–96] years; mean height 160.3 cm [142–180]) that were donated to the College of Medicine of The Catholic University of Korea. The cadavers were randomly selected, and written consent for use of cadavers in the study was obtained from the donors or their legal representatives. This study was conducted in compliance with the Anatomy and Preservation of Corpses Act of the Republic of Korea (No. 14,885) and received approval from the Anatomy Review Committee of The Catholic University School of Medicine (No. R19-A019).

Measurement of the SIJ ROM

To measure the SIJ ROM when the cadaver was moved from an unweighted position to a body-weighted position, five motion-analysis cameras (Kestrel 1300, Motion Analysis, USA) were installed in front of and to the side of the cadaver at various angles. We fixed markers with diameters of 12.7 mm to six specific locations (the superior sacral crest, inferior sacral crest, right lateral ilium, left lateral ilium, right posterior ilium, and left posterior ilium) on the posterior pelvis of each cadaver using screws to ensure recognition by the cameras (Fig. 1a). To observe the SIJ ROM, we lifted the axillary region of the cadaver using a lift machine, placing it in a state of zero weight on the SIJ. We then lowered the lift to bring the lower part of the cadaver’s sacrum into contact with the chair, transitioning it into an SIJ-weighted state. The angle between the line connecting the superior and inferior parts of the sacrum’s median crest and the line connecting the lateral and posterior parts of the iliac crest was used to measure the SIJ ROM (Fig. 1b). The ROM on both sides of each SIJ was measured three times as the difference in angles between the unloaded state (where there was no weight on the SIJ) and the loaded state (where there was weight on the SIJ).

Fig. 1.

Marker configurations for measurement. (a) Fixation of six markers directly to the bone: four on the ilium and two on the sacrum. LL: left lateral, RL: right lateral, LP: left posterior, RP: right posterior, SS: superior sacral crest, IS: inferior sacral crest. (b) Lateral view of the angle calculation. The change of angle was calculated between the RL and RP connecting lines and the SS and IS connections

Auricular surface 3D modeling and measurements

After experimental measurements of the SIJ ROM the sacrum and hip bone were removed from each cadaver while preserving the anterior sacroiliac ligament, interosseous sacroiliac ligament, posterior sacroiliac ligament, sacrotuberous ligament, and sacrospinous ligament. The surrounding soft tissues were also removed. Subsequently, three-dimensional (3D) models of the sacrum and hip bone were created using digital imaging and communications in medicine (DICOM) data acquired from a computed tomography (CT) scanner. The CT slices had a thickness of 0.625 mm. The DICOM files were then imported into Mimics, an image-based 3D modeling software (Mimic Ver. 21.0; Materialise, Leuven, Belgium). For morphological analysis of the iliac auricular surface, measurements s were performed using a geometric model of the iliac and sacral auricular surfaces built in STL CAD software (3-matic, Ver. 8.0; Materialise). The landmark points and measurements for analyzing the morphology of the auricular surface were defined by referring to previous studies, and all measurements were calculated with landmark points on the 3D model (Figs. 2 and 3; Table 1) [20, 42, 45]. Based on the 3D models, we measured the posterior angle of the auricular surface and classified the shapes into three types. To determine whether any degenerative changes in the bone could affect the SIJ ROM, we observed the auricular surface, as well as the surrounding bone bridge and bone defects, in sagittal, coronal, and axial views of CT images.

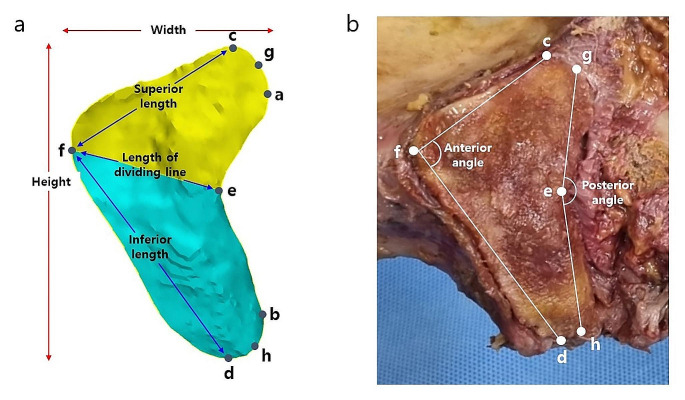

Fig. 2.

Landmark points and measurement variables. (a) Linear dimensions of the iliac auricular surface on the 3D model. The yellow region is the upper portion area and the blue region is the lower portion area. (b) Angular dimensions of the iliac auricular surface

Fig. 3.

Surface groove and spacing of the SIJ. (a) The groove is the distance from the red line to both the medial (inner) and lateral (outer) surfaces, respectively. (b) Surface spacing is the distance between the iliac surface and the sacral surface

Table 1.

Definitions of landmark points on the iliac auricular surface

| Landmark points | Definition |

|---|---|

| a | The most protruding point at the superior posterior of the auricular surface |

| b | The most protruding point at the inferior posterior of the auricular surface |

| c | The highest point on the superior part of the auricular surface |

| d | The lowest point on the inferior part of the auricular surface |

| e | The most concave point on the back of the auricular surface |

| f | The most protruding point on the front of the auricular surface |

| g | The midpoint between point a and point c |

| h | The midpoint between point b and point d |

Statistical analysis

When the data followed a normal distribution, descriptive statistics were presented as mean and standard deviation. For comparisons of group differences, such as between females and males in SIJ ROM and auricular surface morphology measurements, as well as between the high-motion and low-motion groups based on the mean ROM of the SIJ, independent-sample t-tests were used to assess the significance of differences. A p < 0.05 indicated statistical significance. To assess intra-rater reliability, a single examiner measured each measurement twice and confirmed the intraclass correlation coefficients.

Results

Comparison of the SIJ ROM

The ROMs of the right and left sides of the SIJ were measured separately. The SIJ ROM was from 0.2° to 6.7°, with a mean of 2.39°. The mean ROM for females was 3.58°, and that for males was 1.38° (p < 0.01). When dividing the data into high-motion and low-motion groups based on the mean ROM, the high-motion group had a mean ROM of 3.87°, and the low-motion group had a mean ROM of 1.13° (p < 0.01) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Measurement of the SIJ ROM (comparison between females and males and between high-motion group and low-motion group)

| SIJ ROM | Sex | |||

| Females | Males | Combined | P | |

| Mean ± SD | 3.58° ± 1.49 | 1.38° ± 1.00 | 2.39° ± 1.65 | < 0.01 |

| SIJ ROM | SIJ Mobility | |||

| High-motion group | Low-motion group | P | ||

| Mean ± SD | 3.87° ± 1.19 | 1.13° ± 0.62 | < 0.01 | |

When comparing sides, the difference in SIJ ROMs was from 0.0° to 2.6°. The mean of the ROMs from 0.0° to 2.6° was 0.9°, based on which we divided the participants into symmetric and asymmetric groups. The group with symmetrical motion on the two sides (a difference of 0.00° to 0.80°) accounted for 66.67% of the cadavers, and the group with asymmetrical motion (1.20° to 2.60°) accounted for 33.33% (p < 0.01). In a comparison based on sex, 62.50% of the symmetrical group were males and 37.50% were females, while 62.50% of the asymmetrical group were females and 37.50% were males (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison between symmetric and asymmetric groups of the SIJ ROM

| Symmetry of the SIJ ROM | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetric group (0.00°–0.80°) |

Asymmetric group (1.20°–2.60°) |

P | |

| Mean ± SD | 1.86° ± 0.49 | 0.41° ± 0.28 | < 0.01 |

| Females | 37.50% | 62.50% | |

| Males | 62.50% | 37.50% | |

| Combined | 66.67% | 33.33% | |

Morphological analysis by measurements

Auricular surface 3D models were created using 3-Matic software, and the shapes were classified. The morphological characteristics of the auricular surface were determined based on the measurements. The results are presented as mean and standard deviation. Statistically significant differences were observed in comparisons of sex, high-motion and low-motion groups, and groups with symmetrical and asymmetrical motion (p < 0.05). However, there was no significant correlation between the morphological characteristics of the auricular surface and the SIJ ROM (p = 0.09–0.49). To assess the intra-rater reliability of the measurements, a random sample of 10% of the 48 specimens was selected. The intraclass correlation coefficient indicated high reliability within a range of 0.862 to 0.999.

Classification of the shape of the auricular surface

The posterior angle was used to classify types and was measured between points of the upper and lower posterior auricular surfaces and the most concave point on the posterior auricular surface. This method was described by Jesse et al., who referred to the measurement as the alpha angle [7]. An angle less than 130° was defined as type 1, an angle between 130° and 160° was defined as type 2, and an angle greater than 160° was defined as type 3 (Fig. 4) [7, 36, 46]. Type 2 was the most common overall (77.08%) and found among males (39.58%) and females (37.50%), followed by type 3 (20.83%) and type 1 (2.08%). Additionally, in both the high-motion and low-motion groups, type 2 was most common, in 39.58% and 37.50% of patients, respectively (Table 4).

Fig. 4.

Types of shapes of the auricular surface. Type 1: Less than 130°, type 2: between 130° and 160°, type 3: greater than 160° (Jesse et al., 2017)

Table 4.

Comparisons between females and males and between high-motion and low-motion groups based on shape of the auricular surface

| Shape | Sex | SIJ mobility | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | Males | High-motion group | Low-motion group | ||

| Type 1 < 130° | 0.00% | 2.08% | 0.00% | 2.08% | |

| 130° ≤ type 2 ≤ 160° | 37.50% | 39.58% | 39.58% | 37.50% | |

| 160° < type 3 | 8.33% | 12.50% | 6.25% | 14.58% | |

Comparison of auricular surface morphology by sex

The measurements in the 3D models were categorized as means for females, males, and combined (Table 5). Males had significantly higher values than females for height, inferior length, superior area, inferior area, total area, and surface medial groove (p < 0.05). Females had higher posterior angles and surface spacing. Males had higher values for dividing line, superior length, anterior angle, and surface lateral groove measurements, but the differences were not significant (p = 0.06–0.49).

Table 5.

Measurements of the auricular surface. Significant differences are evident between females and males in width, height, inferior length, superior area, inferior area, total area, and surface medial groove

| Measurements | Sex | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | Males | Combined | P | |

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | ||

| Width (mm) | 30.45 ± 3.83 | 32.65 ± 3.30 | 31.43 ± 3.63 | 0.02 |

| Height (mm) | 54.35 ± 4.49 | 60.51 ± 3.49 | 57.68 ± 5.01 | < 0.01 |

| Length of dividing line (mm) | 23.73 ± 3.58 | 24.62 ± 3.40 | 24.21 ± 3.48 | 0.19 |

| Superior length (mm) | 30.17 ± 5.20 | 32.06 ± 3.44 | 31.19 ± 4.39 | 0.08 |

| Inferior length (mm) | 44.43 ± 6.17 | 48.81 ± 4.53 | 46.80 ± 5.73 | < 0.01 |

| Anterior angle (°) | 91.93 ± 9.40 | 95.81 ± 8.03 | 94.03 ± 8.81 | 0.06 |

| Posterior angle (°) | 149.07 ± 10.36 | 149.01 ± 11.05 | 149.04 ± 10.63 | 0.49 |

| Superior area (mm²) | 506.92 ± 114.75 | 560.88 ± 89.06 | 536.15 ± 104.12 | 0.04 |

| Inferior area (mm²) | 615.80 ± 131.33 | 805.61 ± 109.22 | 718.61 ± 152.27 | < 0.01 |

| Total area (mm²) | 1122.71 ± 214.27 | 1366.49 ± 176.86 | 1254.76 ± 228.52 | < 0.01 |

| Surface medial groove (mm) | 3.12 ± 0.84 | 3.66 ± 0.85 | 3.42 ± 0.88 | 0.02 |

| Surface lateral groove (mm) | 4.71 ± 2.08 | 4.73 ± 1.27 | 4.72 ± 1.67 | 0.48 |

| Surface spacing (mm) | 1.38 ± 0.53 | 1.25 ± 0.41 | 1.31 ± 0.47 | 0.18 |

Comparison of auricular surface morphology between high-motion and low-motion groups

Measurements were compared from the high-motion and low-motion groups divided based on a mean SIJ ROM of 2.39°. Four measurements (length of dividing line, superior length, superior area, and surface spacing) were higher in the high-motion group compared with the low-motion group. In the remaining measurements, the low-motion group had higher values, but none were significantly different (p = 0.09–0.49) (Table 6).

Table 6.

The comparison of measurements between the high-motion and low-motion groups; no significant differences were observed in any of the measurements between the two groups

| Measurements | SIJ mobility | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| High-motion group | Low-motion group | P | |

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | ||

| Width (mm) | 31.21 ± 4.47 | 31.62 ± 2.82 | 0.49 |

| Height (mm) | 57.31 ± 4.72 | 58.00 ± 5.32 | 0.32 |

| Length of dividing line (mm) | 24.53 ± 4.12 | 23.95 ± 2.89 | 0.29 |

| Superior length (mm) | 31.22 ± 5.65 | 31.17 ± 3.07 | 0.49 |

| Inferior length (mm) | 46.34 ± 6.66 | 47.19 ± 4.91 | 0.31 |

| Anterior angle (°) | 93.60 ± 7.29 | 94.39 ± 10.05 | 0.38 |

| Posterior angle (°) | 148.96 ± 8.66 | 149.10 ± 12.22 | 0.48 |

| Superior area (mm²) | 559.50 ± 125.88 | 516.39 ± 78.64 | 0.09 |

| Inferior area (mm²) | 688.56 ± 172.60 | 744.04 ± 130.76 | 0.11 |

| Total area (mm²) | 1248.06 ± 273.14 | 1260.42 ± 188.23 | 0.43 |

| Surface medial groove (mm) | 3.39 ± 0.94 | 3.44 ± 0.84 | 0.41 |

| Surface lateral groove (mm) | 4.57 ± 1.58 | 4.85 ± 1.76 | 0.28 |

| Surface spacing (mm) | 1.37 ± 0.55 | 1.26 ± 0.38 | 0.21 |

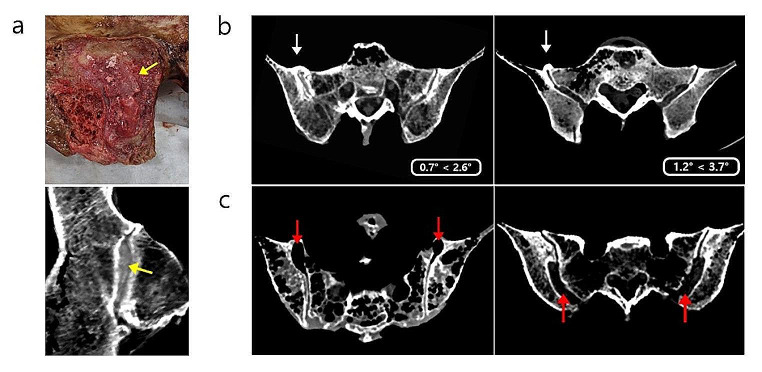

Degenerative changes in the bones (bone bridge and bone defection)

Bone bridges and bone defects between the sacrum and hip bone were observed by CT, and we investigated whether these defects could affect SIJ ROM (Fig. 5). Bone bridges were observed in 39.58% of cadavers, with 5 of 24 cadavers having them in both joints and 9 of 24 cadavers having them in one joint. These bone bridges were observed in 29.17% of males and 10.42% of females, as well as in 6.25% of the high-motion group and 33.33% of the low-motion group. However, bone defection was observed in only 18.75% of females and not in males. In the high-motion group, bone defection was observed in 16.67% (Table 7). We observed differences in the SIJ ROM in joints with no bone bridges or bone defection, joints with only one affected side, and joints with both sides affected. In relation to the bone bridge, SIJ ROM was greatest in joints without a bone bridge, followed by joints with a bone bridge on only one side and then joints with a bridge on both sides. With respect to bone defection, SIJ ROM was greatest in joints with bone defection on both sides, followed by joints with bone defection on only one side and then joints with no bone defection (Table 8).

Fig. 5.

Bone degeneration. (a) Ossification of the cartilage between the auricular surfaces (yellow arrows). (b) CT axial view of a bone bridge (white arrows). The mobility on the side with the bone bridge is lower than that on the unaffected side. (c) CT axial view of bone defection (red arrows)

Table 7.

Percentages of bone bridge and bone defection by sex and motion groups

| Bone degeneration | Sex | SIJ mobility | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | Males | High-motion group | Low-motion group | ||

| Bone bridge | 10.42% | 29.17% | 6.25% | 33.33% | |

| Bone defection | 18.75% | 0.00% | 16.67% | 2.08% | |

Table 8.

The SIJ ROM of bones with bridge and defection on both sides, one side, or no sides

| Bone degeneration | SIJ ROM (mean ± SD) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Both sides | One side | None | ||

| Bone bridge | 1.14° ± 0.88 | 2.05° ± 1.02 | 3.32° ± 1.91 | |

| Bone defection | 4.50° ± 1.45 | 3.85° ± 0.21 | 1.87° ± 1.31 | |

Discussion

In this study, we focused on the SIJ ROM and the auricular surface, which comprises the SIJ, as potential causes of SIJD. We investigated whether there was a significant relationship between SIJ ROM and the morphology of the iliac auricular surface. The mean overall ROM value was 2.39°, the mean ROM for females was 3.58°, and the mean ROM for males was 1.38°, with significantly greater motion in females than males. According to previous studies, the difference in sex may be attributable to the increased flexibility of the surrounding ligaments due to hormones such as relaxin, which relaxes the ligaments and joints, during pregnancy and childbirth in females. It also suggests that the SIJ in males is stiffer than in females [16, 40, 45]. In the high-motion group with an SIJ ROM exceeding the mean of 2.39° and the low-motion group with motion below the mean, the respective mean ROMs were significantly distinguishable at 3.87° and 1.13°. Some cadavers showed a similar or same ROM on the two sides, while others showed a large difference between the sides. The group with symmetrical motion (0.00°– 0.80°) accounted for 66.67% of cases, and the group with asymmetrical motion (1.20°–2.60°) accounted for 33.33%. There were approximately twice as many cadavers in the symmetrical group than in the asymmetrical group, with females observed at a rate 1.67 times greater than that of males. These results suggest that female SIJs may be less stiff than male SIJs, potentially influencing SIJ instability.

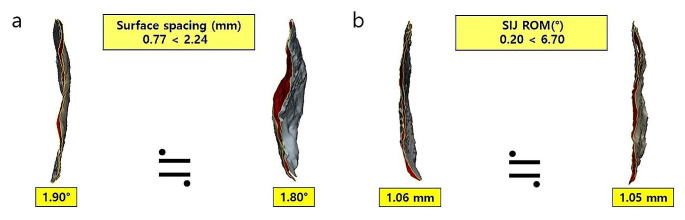

According to the posterior angle of the auricular surfaces, type 2 (between 130° to 160°) was most common among both females and males, as well as in both the high-motion and low-motion groups. However, none of the three types of shape affected the SIJ ROM (p = 0.48–0.49). Males showed significantly greater widths, heights, inferior lengths, superior areas, inferior areas, total areas, and surface medial grooves compared with females (p < 0.05). However, in a comparison of the high-motion and low-motion groups, no significant differences were found in any of the measurements (p = 0.09–0.49). Surface spacing, which measures the distance between the auricular surfaces of the sacrum and ilium, revealed that, even with similar distances, the SIJ ROM can be significantly different with a similar SIJ ROM in different spacings (Fig. 6). This confirms that the distance between the two surfaces did not affect the SIJ ROM.

Fig. 6.

Surface spacing and SIJ ROM do not affect each other. (a) Despite similar SIJ ROMs, there is a significant difference in the distance between the two auricular surfaces. (b) Conversely, a similar distance between the two auricular surfaces resulted in a substantial difference in the SIJ ROM

In a previous study, bone bridges were reported to be approximately 6.7 times more common in the pelvis of males than in females [47]. In this study, bone bridges were found in 39.58% of the cadavers, with 29.17% in males and 10.42% in females, a difference of approximately 2.8 times. In addition, bridges were approximately 5.3 times more common in the low-motion group (33.33%) than in the high-motion group (6.25%). Formation of a bone bridge appears to affect the SIJ ROM, with motion angles of 3.32° without a bone bridge, 2.05° with a bone bridge on one side, and 1.14° with a bone bridge on both sides. Individuals with bone bridges had a smaller SIJ ROM compared with those without bone bridges. Bone defects were observed on CT in 18.75% of cadavers, all of which were females. Furthermore, bone defection was found in a much higher percentage in the high-motion group (16.67%) than in the low-motion group (2.08%). Bone bridges are caused by ossification of ligaments and tendons in contact with the SIJ, and bone defections are seen where bone loss occurs in and around the auricular surfaces [47]. All these factors may affect the SIJ ROM.

Our findings help elucidate the relationship between SIJ ROM and auricular surface morphology by providing insights into the anatomical structures and biomechanical factors that influence SIJ ROM. Additionally, our findings, which included the discovery of bilateral asymmetry in the SIJ ROM, sex-specific differences in the SIJ ROM, and the influence of surrounding structures on the SIJ ROM, may contribute to the development of sex-specific criteria for SIJD diagnosis and enhance the accuracy of diagnosis. One limitation of this study is that the specimens were donated cadavers, resulting in a high mean age at the time of death (81.6 years, range 49–96 years). As age increases, the SIJ may change, and the surrounding tissues may weaken. However, this study investigated the relationship between SIJ ROM and auricular surface morphology by measuring the SIJ ROM and analyzing the auricular surface morphologically, which could help elucidate both anatomical and biomechanical aspects of the SIJ.

Conclusion

Females had greater SIJ ROM than males, but the morphological characteristics of the auricular surface do not affect SIJ ROM. We divided cadavers into high-motion and low-motion groups based on the mean SIJ ROM and compared them based on the morphology of the iliac auricular surface. However, no significant differences in the morphology of the auricular surface were found between the high-motion and low-motion groups. The SIJ ROM is likely more highly affected by the ligaments connecting the sacrum and ilium to the surrounding muscle tissue and to the bone formed within and around the SIJ than by the morphological characteristics of the auricular surfaces. Understanding the differences in SIJ ROM between females and males can help assess the risk of SIJ problems based on sex and may lead to the development of new preventive strategies and provide guidelines that aid in disease prevention and good health.

Author contributions

Dai-Soon Kwak conceptualized the study. Seonjin Shin curated the data. Seonjin Shin and Dai-Soon Kwak performed the formal analysis. Seonjin Shin and U-Young Lee performed the investigation. Dai-Soon Kwak administered the project. Dai-Soon Kwak and U-Young Lee validated the process. Seonjin Shin visualized the data. Dai-Soon Kwak acquired funding. Seonjin Shin original drafted the manuscript. Dai-Soon Kwak and U- Young Lee edited the manuscript prior to the final version.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. NRF-2019R1A2C1002609) and the Industry-Academy Cooperation Program through the Industry Academic Cooperation Foundation of the Catholic University of Korea.

Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was conducted in compliance with the Anatomy and Preservation of Corpses Act of the Republic of Korea (No. 14885) and received approval from the Anatomy Review Committee of The Catholic University School of Medicine (No. R19-A019).

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Paquin JD, van der Rest M, Marie PJ, Mort JS, Pidoux I, Poole AR, Roughley PJ. Biochemical and morphologic studies of cartilage from the adult human sacroiliac joint. Arthritis Rheum. 1983;26(7):887–95. doi: 10.1002/art.1780260710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cole JD, Blum DA, Ansel LJ. Outcome after fixation of unstable posterior pelvic ring injuries. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;329160–79. 10.1097/00003086-199608000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Vleeming A, Stoeckart R, Volkers AC, Snijders CJ. Relation between form and function in the sacroiliac joint. Part I: clinical anatomical aspects. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1990;15(2):130–2. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199002000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vleeming A, Volkers AC, Snijders CJ, Stoeckart R. Relation between form and function in the sacroiliac joint. Part II: Biomechanical aspects. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1990;15(2):133–6. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199002000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowen V, Cassidy JD. Macroscopic and microscopic anatomy of the sacroiliac joint from embryonic life until the eighth decade. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1981;6(6):620–8. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198111000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bakland O, Hansen JH. The axial sacroiliac joint. Anat Clin. 1984;6(1):29–36. doi: 10.1007/bf01811211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jesse MK, Kleck C, Williams A, Petersen B, Glueck D, Lind K, Patel V. 3D morphometric analysis of normal sacroiliac joints: a new classification of surface shape variation and the potential implications in Pain syndromes. Pain Physician. 2017;20(5):E701–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toyohara R, Kaneuji A, Takano N, Kurosawa D, Hammer N, Ohashi T. A patient-cohort study of numerical analysis on sacroiliac joint stress distribution in pre- and post-operative hip dysplasia. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):14500. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-18752-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Toyohara R, Kurosawa D, Hammer N, Werner M, Honda K, Sekiguchi Y, Izumi SI, Murakami E, Ozawa H, Ohashi T. Finite element analysis of load transition on sacroiliac joint during bipedal walking. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):13683. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-70676-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen SP, Chen Y, Neufeld NJ. Sacroiliac joint pain: a comprehensive review of epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. Expert Rev Neurother. 2013;13(1):99–116. doi: 10.1586/ern.12.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kiapour A, Joukar A, Elgafy H, Erbulut DU, Agarwal AK, Goel VK. Biomechanics of the Sacroiliac Joint: anatomy, function, Biomechanics, sexual dimorphism, and causes of Pain. Int J Spine Surg. 2020;14(Suppl 1):3–13. doi: 10.14444/6077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lingutla KK, Pollock R, Ahuja S. Sacroiliac joint fusion for low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Spine J. 2016;25(6):1924–31. doi: 10.1007/s00586-016-4490-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sachs D, Capobianco R. One year successful outcomes for novel sacroiliac joint arthrodesis system. Ann Surg Innov Res. 2012;6(1):13. doi: 10.1186/1750-1164-6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwarzer AC, Aprill CN, Bogduk N. The sacroiliac joint in chronic low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1995;20(1):31–7. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199501000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Capobianco R, Cher D. Safety and effectiveness of minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion in women with persistent post-partum posterior pelvic girdle pain: 12-month outcomes from a prospective, multi-center trial. Springerplus. 2015;4:570. doi: 10.1186/s40064-015-1359-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gartenberg A, Nessim A, Cho W. Sacroiliac joint dysfunction: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Eur Spine J. 2021;30(10):2936–43. doi: 10.1007/s00586-021-06927-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buchanan P, Vodapally S, Lee DW, Hagedorn JM, Bovinet C, Strand N, Sayed D, Deer T. Successful diagnosis of Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction. J Pain Res. 2021;14:3135–43. doi: 10.2147/jpr.S327351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drake RL, Vogl AW, Mitchell A. W. M. Gray`s anatomy for students. 3. Philadelphia: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. Thieme atlas of anatomy. General anatomy and musculoskeletal system. New York: Thieme; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nishi K, Tsurumoto T, Okamoto K, Ogami-Takamura K, Hasegawa T, Moriuchi T, Sakamoto J, Oyamada J, Higashi T, Manabe Y, et al. Three-dimensional morphological analysis of the human sacroiliac joint: influences on the degenerative changes of the auricular surfaces. J Anat. 2018;232(2):238–49. doi: 10.1111/joa.12765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Valmassy RL. Clinical biomechanics of the lower extremities. St. Louis: Mosby; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sashin D, A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE ANATOMY AND THE PATHOLOGIC CHANGES OF, THE SACRO-ILIAC JOINTS J Bone Joint Surg. 1930;12(4):891–910. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vleeming A, Van Wingerden JP, Dijkstra PF, Stoeckart R, Snijders CJ, Stijnen T. Mobility in the sacroiliac joints in the elderly: a kinematic and radiological study. Clin Biomech (Bristol Avon) 1992;7(3):170–6. doi: 10.1016/0268-0033(92)90032-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katada S. Principles of Manual Medicine for Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction; Springer. 2019. 10.1007/978-981-13-6810-3_6.

- 25.Vleeming A, Schuenke MD, Masi AT, Carreiro JE, Danneels L, Willard FH. The sacroiliac joint: an overview of its anatomy, function and potential clinical implications. J Anat. 2012;221(6):537–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2012.01564.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zlomislic VG, Steve R. Anatomy and biomechanics of the Sacroiliac Joint. Techniques Orthop. 2019;34(2):70–5. doi: 10.1097/BTO.0000000000000379. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palsson TS, Gibson W, Darlow B, Bunzli S, Lehman G, Rabey M, Moloney N, Vaegter HB, Bagg MK, Travers M. Changing the narrative in diagnosis and management of Pain in the Sacroiliac Joint Area. Phys Ther. 2019;99(11):1511–9. doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzz108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sturesson B, Selvik G, Udén A. Movements of the sacroiliac joints. A roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1989;14(2):162–5. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198902000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacob HA, Kissling RO. The mobility of the sacroiliac joints in healthy volunteers between 20 and 50 years of age. Clin Biomech (Bristol Avon) 1995;10(7):352–61. doi: 10.1016/0268-0033(95)00003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kibsgård TJ, Røise O, Stuge B, Röhrl SM. Precision and accuracy measurement of radiostereometric analysis applied to movement of the sacroiliac joint. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(11):3187–94. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2413-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kibsgård TJ, Røise O, Sturesson B, Röhrl SM, Stuge B. Radiosteriometric analysis of movement in the sacroiliac joint during a single-leg stance in patients with long-lasting pelvic girdle pain. Clin Biomech (Bristol Avon) 2014;29(4):406–11. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sturesson B, Uden A, Vleeming A. A radiostereometric analysis of movements of the sacroiliac joints during the standing hip flexion test. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25(3):364–8. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200002010-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nagamoto Y, Iwasaki M, Sakaura H, Sugiura T, Fujimori T, Matsuo Y, Kashii M, Murase T, Yoshikawa H, Sugamoto K. Sacroiliac joint motion in patients with degenerative lumbar spine disorders. J Neurosurg Spine. 2015;23(2):209–16. doi: 10.3171/2014.12.Spine14590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ito K, Morito T, Gamada K. The association between sacral morphology and sacroiliac joint conformity demonstrated on CT-based bone models. Clin Anat. 2020;33(6):880–6. doi: 10.1002/ca.23579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weigelt L, Laux CJ, Slankamenac K, Ngyuen TDL, Osterhoff G, Werner CML. Sacral dysmorphism and its implication on the size of the Sacroiliac Joint Surface. Clin Spine Surg. 2019;32(3):E140–4. doi: 10.1097/bsd.0000000000000749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Poilliot A, Hammer N, Toranelli M, Gay MH, Müller-Gerbl M. Auricular surface morphology and surface area does not influence subchondral bone density distribution in the dysfunctional sacroiliac joint. Clin Anat. 2023;36(3):447–56. doi: 10.1002/ca.23980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nishi K, Saiki K, Imamura T, Okamoto K, Wakebe T, Ogami K, Hasegawa T, Moriuchi T, Sakamoto J, Manabe Y, et al. Degenerative changes of the sacroiliac auricular joint surface-validation of influential factors. Anat Sci Int. 2017;92(4):530–8. doi: 10.1007/s12565-016-0354-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Igarashi Y, Uesu K, Wakebe T, Kanazawa E. New method for estimation of adult skeletal age at death from the morphology of the auricular surface of the ilium. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2005;128(2):324–39. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rmoutilová R, Dupej J, Velemínská J, Brůžek J. Geometric morphometric and traditional methods for sex assessment using the posterior ilium. Leg Med (Tokyo) 2017;26:52–61. doi: 10.1016/j.legalmed.2017.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lovejoy CO, Meindl RS, Pryzbeck TR, Mensforth RP. Chronological metamorphosis of the auricular surface of the ilium: a new method for the determination of adult skeletal age at death. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1985;68(1):15–28. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330680103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prassopoulos PK, Faflia CP, Voloudaki AE, Gourtsoyiannis NC. Sacroiliac joints: anatomical variants on CT. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1999;23(2):323–7. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199903000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nishi K, Saiki K, Oyamada J, Okamoto K, Ogami-Takamura K, Hasegawa T, Moriuchi T, Sakamoto J, Higashi T, Tsurumoto T, et al. Sex-based differences in human sacroiliac joint shape: a three-dimensional morphological analysis of the iliac auricular surface of modern Japanese macerated bones. Anat Sci Int. 2020;95(2):219–29. doi: 10.1007/s12565-019-00513-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Buckberry JL, Chamberlain AT. Age estimation from the auricular surface of the ilium: a revised method. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2002;119(3):231–9. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.10130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ulas ST, Diekhoff T, Ziegeler K. Sex disparities of the Sacroiliac Joint: Focus on Joint Anatomy and imaging appearance. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13(4). 10.3390/diagnostics13040642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Anastasiou E, Chamberlain AT. The sexual dimorphism of the sacro-iliac joint: an investigation using geometric morphometric techniques. J Forensic Sci. 2013;58(Suppl 1):S126–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2012.02282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ou-Yang DC, York PJ, Kleck CJ, Patel VV. Diagnosis and management of Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99(23):2027–36. doi: 10.2106/jbjs.17.00245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dar G, Peleg S, Masharawi Y, Steinberg N, Rothschild BM, Hershkovitz I. The association of sacroiliac joint bridging with other enthesopathies in the human body. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32(10):E303–308. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000261568.88404.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]