Abstract

目的

排斥反应一直是限制移植肾存活的最重要因素。移植肾病理活检是排斥反应诊断的金标准,但因其局限性并不能作为常规监测手段。近来,外周血淋巴细胞亚群检测已成为评估机体免疫系统的重要手段,然而其在肾移植领域的应用价值和策略有待探究;此外,常规检验参数的新开发利用也是探索肾移植疾病诊断策略和预测模型的重要手段。本研究旨在结合血常规,探究外周血淋巴细胞亚群与T细胞介导的排斥反应(T cell-mediated rejection,TCMR)和抗体介导的排斥反应(antibody-mediated rejection,ABMR)的相关性及其协助诊断价值。

方法

回顾性分析2021年1至12月就诊于中南大学湘雅二医院且符合纳入标准的154例肾移植受者的基本资料以及临床资料。根据排斥反应是否发生及其类型分为稳定组、TCMR组和ABMR组。比较3组的基本资料,并将TCMR组和ABMR组排斥反应治疗前的移植肾功能、血常规和外周血淋巴细胞亚群数据与稳定组进行比较。

结果

稳定组、TCMR组和ABMR组在免疫抑制维持方案、移植肾来源等方面差异均无统计学意义(均P>0.05),但ABMR组的肾移植术后时间显著长于稳定组(P<0.001)和TCMR组(P<0.05)。在移植肾功能方面,ABMR组的血肌酐值均高于稳定组和TCMR组(均P<0.01),并且TCMR组也高于稳定组(P<0.01);TCMR组和ABMR组的尿素氮均显著高于稳定组(均P<0.01),而TCMR组和ABMR组之间差异无统计学意义(P>0.05);TCMR组和ABMR组的估算肾小球滤过率(estimated glomerular filtration rate,eGFR)均低于稳定组(均P<0.01)。在血常规方面:ABMR组的血红蛋白、红细胞数和血小板数均低于稳定组(均P<0.05);TCMR组的中性粒细胞比例和数量均高于稳定组(均P<0.05),ABMR组的中性粒细胞比例高于稳定组(P<0.05);TCMR组的嗜酸性粒细胞比例和数量均低于稳定组和ABMR组(均P<0.05);TCMR组和ABMR组的嗜碱性粒细胞比例和数量、淋巴细胞比例和数量均低于稳定组(均P<0.05);稳定组、TCMR组和ABMR组的单核细胞比例和数量差异均无统计学意义(均P>0.05)。在淋巴细胞亚群方面:TCMR组和ABMR组的CD45+细胞和T细胞数均低于稳定组(均P<0.05);TCMR组的CD4+ T细胞数、NK细胞数和B细胞数均低于稳定组(均P<0.05);稳定组、TCMR组和ABMR组在T细胞比例、CD4+ T细胞比例、CD8+ T细胞比例和数量、CD4+/CD8+ T细胞比值、NK细胞比例、B细胞比例方面差异均无统计学意义(均P>0.05)。

结论

排斥反应的发生导致移植肾功能受损,同时会伴有肾移植受者血常规、外周血淋巴细胞亚群部分指标的特征性变化。TCMR和ABMR发生时血常规、外周血淋巴细胞亚群部分指标改变特点的不同可能有助于预测和诊断排斥反应以及二者的鉴别。

Keywords: 肾移植, 抗体介导的排斥反应, T细胞介导的排斥反应, 血常规, 外周血淋巴细胞亚群

Abstract

Objective

Rejection remains the most important factor limiting the survival of transplanted kidneys. Although a pathological biopsy of the transplanted kidney is the gold standard for diagnosing rejection, its limitations prevent it from being used as a routine monitoring method. Recently, peripheral blood lymphocyte subpopulation testing has become an important means of assessing the body’s immune system, however, its application value and strategy in the field of kidney transplantation need further exploration. Additionally, the development and utilization of routine test parameters are also important methods for exploring diagnostic strategies and predictive models for kidney transplant diseases. This study aims to explore the correlation between peripheral blood lymphocyte subpopulations and T cell-mediated rejection (TCMR) and antibody-mediated rejection (ABMR), as well as their diagnostic value, in conjunction with routine blood tests.

Methods

A total of 154 kidney transplant recipients, who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria and were treated at the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University from January to December, 2021, were selected as the study subjects. They were assigned into a stable group, a TCMR group, and an ABMR group, based on the occurrence and type of rejection. The basic and clinical data of these recipients were retrospectively analyzed and compared among the 3 groups. The transplant kidney function, routine blood tests, and peripheral blood lymphocyte subpopulation data of the TCMR group and the ABMR group before rejection treatment were compared with those of the stable group.

Results

The stable, TCMR group, and ABMR group showed no statistically significant differences in immunosuppressive maintenance regimens or sources of transplanted kidneys (all P>0.05). However, the post-transplant duration was significantly longer in the ABMR group compared with the stable group (P<0.001) and the TCMR group (P<0.05). Regarding kidney function, serum creatinine levels in the ABMR group were higher than in the stable group and the TCMR group (both P<0.01), with the TCMR group also showing higher levels than the stable group (P<0.01). Both TCMR and ABMR groups had significantly higher blood urea nitrogen levels than the stable group (P<0.01), with no statistically significant difference between TCMR and ABMR groups (P>0.05). The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was lower in both TCMR and ABMR groups compared with the stable group (both P<0.01). In routine blood tests, the ABMR group had lower hemoglobin, red blood cell count, and platelet count than the stable group (all P<0.05). The TCMR group had higher neutrophil percentage (P<0.05) and count (P<0.05) than the stable group, and the ABMR group had a higher neutrophil percentage than the stable group (P<0.05). The eosinophil percentage and count in the TCMR group were lower than in the stable and ABMR groups (all P<0.05). Both TCMR and ABMR groups had lower basophil percentage and count, as well as lower lymphocyte percentage and count, compared with the stable group (all P<0.05). There were no significant differences in monocyte percentage and count among the 3 groups (all P>0.05). In lymphocyte subpopulations, the TCMR and ABMR groups had lower counts of CD45+ cells and T cells compared with the stable group (all P<0.05). The TCMR group also had lower counts of CD4+ T cells, NK cells, and B cells than the stable group (all P<0.05). There were no significant differences in the T cell percentage, CD4+ T cell percentage, CD8+ T cell percentage and their counts, CD4+/CD8+ T cell ratio, NK cell percentage, and B cell percentage among the stable, TCMR, and ABMR groups (all P>0.05).

Conclusion

The occurrence of rejection leads to impaired transplant kidney function, accompanied by characteristic changes in some parameters of routine blood tests and peripheral blood lymphocyte subpopulations in kidney transplant recipients. The different characteristics of changes in some parameters of routine blood tests and peripheral blood lymphocyte subpopulations during TCMR and ABMR may help predict and diagnose rejection and differentiate between TCMR and ABMR.

Keywords: kidney transplantation, antibody-mediated rejection, T cell-mediated rejection, blood routine, lymphocyte subpopulations

肾移植是治疗终末期肾病的最有效方法,然而排斥反应一直是限制移植肾长期生存的最重要因素,尤其是抗体介导的排斥反应(antibody-mediated rejection,ABMR)[1-2]。移植肾病理是排斥反应诊断的金标准,但因其有创性等缺点并不能作为常规监测手段。因此,临床急需一些替代手段,以期能够协助诊断排斥反应、预测移植肾功能以及体现移植免疫反应状态,同时又能日常便利开展[3]。然而,在开发适用于肾移植受者个体化治疗的评估标志物或预测模型方面,仍需进一步研究[4-5]。

新诊断项目的开发和既有项目的重新开发利用是探索肾移植受者疾病诊断策略和风险预测模型的2种重要手段[6]。排斥反应的本质是机体免疫系统活化从而清除“非我”移植器官的过程,因此监测受者免疫系统的变化尤为重要[7]。在众多免疫监测手段当中,血常规是最常见的检验项目;此外,近年来外周血淋巴细胞亚群(又称为TBNK淋巴细胞监测;以下简称“淋巴细胞亚群”)检测已成为评估机体免疫系统的重要手段[8]。虽然淋巴细胞亚群检测已被用于肾移植临床,但目前仍缺乏统一的应用策略[7, 9]。因此,本研究旨在通过回顾性分析肾移植受者的血常规、淋巴细胞亚群检测结果,探究发生T细胞介导的排斥反应(T cell-mediated rejection,TCMR)和ABMR受者之间的异同,为临床诊治TCMR和ABMR提供帮助。

1. 对象与方法

1.1. 对象及分组

将2021年1至12月就诊于中南大学湘雅二医院的肾移植受者列为研究对象。纳入对象为:移植时年龄≥18岁、首次肾移植、无排斥反应以外的可能影响机体免疫系统和移植肾功能的疾病,以及临床资料完善的受者。

根据排斥反应是否发生及其类型将纳入的154名受者分为移植肾功能稳定组(以下简称“稳定组”)、TCMR组和ABMR组。移植肾功能稳定定义为血肌酐低于176 μmol/L且无明显感染和排斥反应指征[10]。TCMR与ABMR均经移植肾病理穿刺活检确诊[11-12]。本研究经中南大学湘雅二医院伦理委员会批准(审批号:临研第126号)。

1.2. 数据采集

采集研究对象的临床资料,包括受者一般资料(性别、年龄等),受者的免疫抑制维持方案,常规实验室检测指标(血常规、肾功能、免疫抑制药物血药浓度、淋巴细胞亚群检测结果等),以及群体反应性抗体(panel reactive antibody,PRA)检测和移植肾病理穿刺活检结果等。淋巴细胞亚群检测分别采用CD45、CD3、CD4、CD8、CD19、CD16、CD56定义T细胞、CD4+ T细胞、CD8+ T细胞、B细胞和NK细胞,并采用绝对计数管进行计数。对于发生排斥反应的受者,血常规、淋巴细胞亚群检测、肾功能的检测结果为抗排斥反应治疗前的检测结果。采用肾脏病膳食改良(modification of diet in renal disease,MDRD)试验公式计算受者的估算肾小球滤过率(estimated glomerular filtration rate,eGFR)[13]。

1.3. 统计学处理

应用SPSS 22.0软件和GraphPad Prism 10.0软件进行数据统计分析和绘图。计量资料以均数±标准差表示,计数资料以例数和百分比进行描述。符合正态分布且方差齐的计量资料采用方差分析进行比较,否则采用非参数Whitney U检验进行分析。计数资料采用χ 2检验进行比较,对于不满足χ 2检验应用要求的计数资料采用Fisher精确概率法进行比较。P<0.05为差异具有统计学意义。

2. 结 果

2.1. 患者基本资料的比较

稳定组、TCMR组和ABMR组在年龄、性别、供体类型、免疫抑制维持方案、移植肾来源等方面差异均无统计学意义(均P>0.05)。在术后时间方面,ABMR组显著长于稳定组和TCMR组(均P<0.05)。在PRA阳性率方面,ABMR组显著高于TCMR组 (P<0.01)。在移植肾功能方面,ABMR组的血肌酐值显著高于稳定组和TCMR组(均P<0.05),并且TCMR组也高于稳定组(P<0.05);TCMR组和ABMR组的尿素氮均显著高于稳定组(均P<0.05),而TCMR组和ABMR组之间差异无统计学意义(P>0.05);TCMR组和ABMR组的eGFR值均显著低于稳定组(均P<0.05),而TCMR组和ABMR组之间差异无统计学意义(P>0.05,表1)。

表1.

受者基本资料的比较

Table 1 Comparison of the general data from the recipients

| 基本资料 | 稳定组(n=133) | TCMR组(n=9) | ABMR组(n=12) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 年龄/岁 | 37.17±11.85 | 43.00±8.94 | 38.67±6.11 | 0.317 |

| 性别(男/女) | 72/61 | 7/2 | 8/4 | 0.271 |

| 术后时间/月 | 28.31±32.37 | 21.67±29.79 | 66.40±58.03*† | 0.001 |

| PRA阳性/[例(%)] | 12(9.02) | 2(22.22) | 5(41.67)† | 0.005 |

| 供体类型/例 | 1.000 | |||

| 尸体供肾 | 112 | 8 | 10 | |

| 活体供肾 | 21 | 1 | 2 | |

| 免疫抑制维持方案/例 | 0.128 | |||

| 他克莫司+霉酚酸+激素 | 119 | 6 | 11 | |

| 环孢素+霉酚酸+激素 | 14 | 3 | 1 | |

| 血肌酐/(μmol·L-1) | 113.91±29.66 | 201.67±55.22* | 309.32±208.85*† | <0.001 |

| 尿素氮/(mmol·L-1) | 8.00±3.20 | 15.26±6.70* | 17.58±11.33* | <0.001 |

| 尿酸/(μmol·L-1) | 345.45±88.45 | 392.22±88.48 | 389.93±112.03 | 0.104 |

| eGFR/(mL·min·1.73 m-2) | 79.86±27.67 | 43.98±20.49* | 35.75±24.51* | <0.001 |

*与稳定组比较,P<0.05;†与TCMR组比较,P<0.05。eGFR:估算肾小球滤过率;TCMR:T细胞介导的排斥反应;ABMR:抗体介导的排斥反应;PRA:群体反应性抗体。

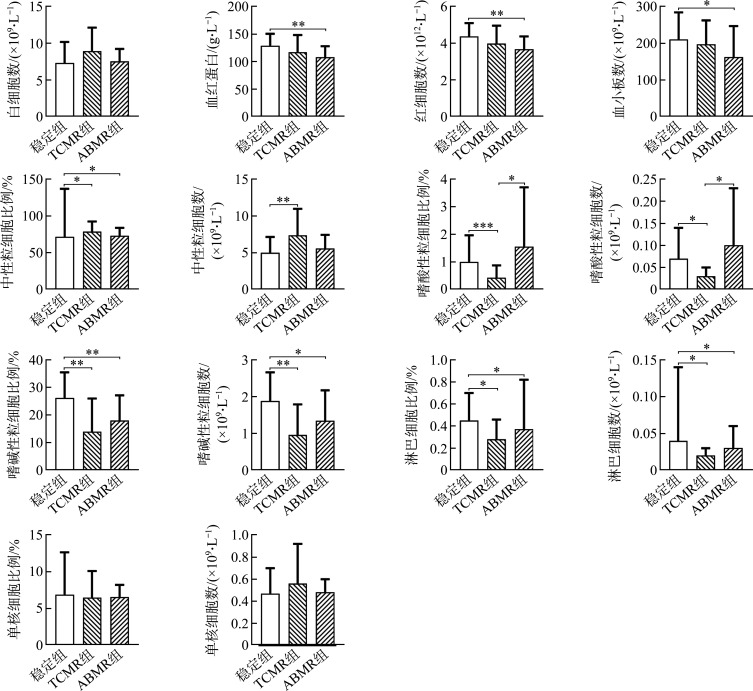

2.2. 血常规结果比较

稳定组、TCMR组和ABMR组在白细胞数量、单核细胞的数量和比例方面的差异均无统计学意义(均P>0.05)。然而,与稳定组相比,ABMR组具有更低的血红蛋白浓度、红细胞数、血小板数(均P<0.05)。在中性粒细胞方面,TCMR组和ABMR组的中性粒细胞比例均高于稳定组(均P<0.05),并且TCMR组的中性粒细胞数量显著高于稳定组(P<0.01)。在嗜酸性粒细胞方面,稳定组和ABMR组的嗜酸性粒细胞比例和数量均高于TCMR组(均P<0.05)。在嗜碱性粒细胞方面,TCMR组和ABMR组的嗜碱性粒细胞比例和数量均低于稳定组(均P<0.05)。在淋巴细胞方面,TCMR组和ABMR组的淋巴细胞比例和数量均低于稳定组(均P<0.05,图1)。

图1.

稳定组、TCMR组和ABMR组之间血常规参数的比较

Figure 1 Comparison of blood routine parameters among the stable group, TCMR group, and ABMR group

*P<0.05, **P<0.01. TCMR: T cell-mediated rejection; ABMR: Antibody-mediated rejection.

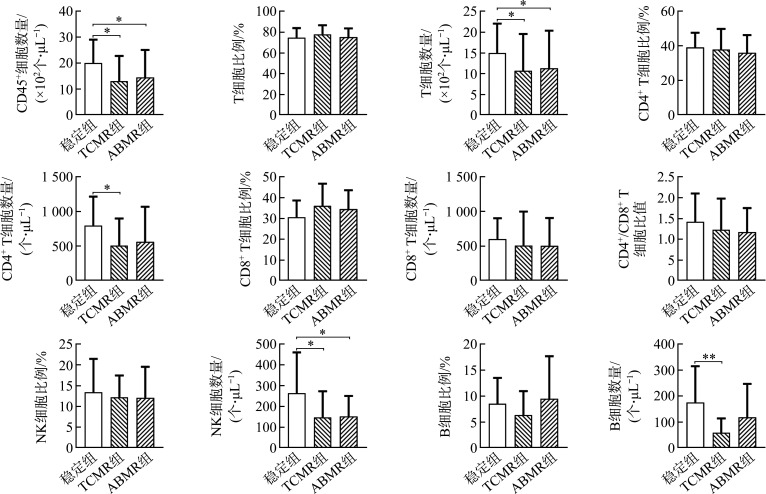

2.3. 淋巴细胞亚群检测结果比较

与血常规中淋巴细胞数量的结果一致,TCMR组和ABMR组的CD45+细胞总数均显著低于稳定组(均P<0.05)。3组受者的T细胞、CD4+ T细胞、和CD8+ T细胞比例和数量差异均无统计学意义(均P>0.05),但TCMR组和ABMR组的T细胞数量、TCMR组的CD4+ T细胞数量均显著低于稳定组(均P<0.05)。在CD4+/CD8+ T细胞比值方面,3组之间的差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。3组NK细胞比例的差异无统计学意义(P>0.05),但TCMR组和ABMR组的NK细胞数量均显著低于稳定组(均P<0.05)。3组B细胞比例的差异无统计学意义(P>0.05);但在B细胞数量方面,TCMR组显著低于稳定组(P<0.01;图2、图3)。

图2.

稳定组、TCMR组和ABMR组间外周血淋巴细胞亚群检测结果比较

Figure 2 Comparison of peripheral blood lymphocyte subsets among the stable group, the TCMR group, and the ABMR group

*P<0.05, **P<0.01. TCMR: T cell-mediated rejection; ABMR: Antibody-mediated rejection; NK: Natural killer.

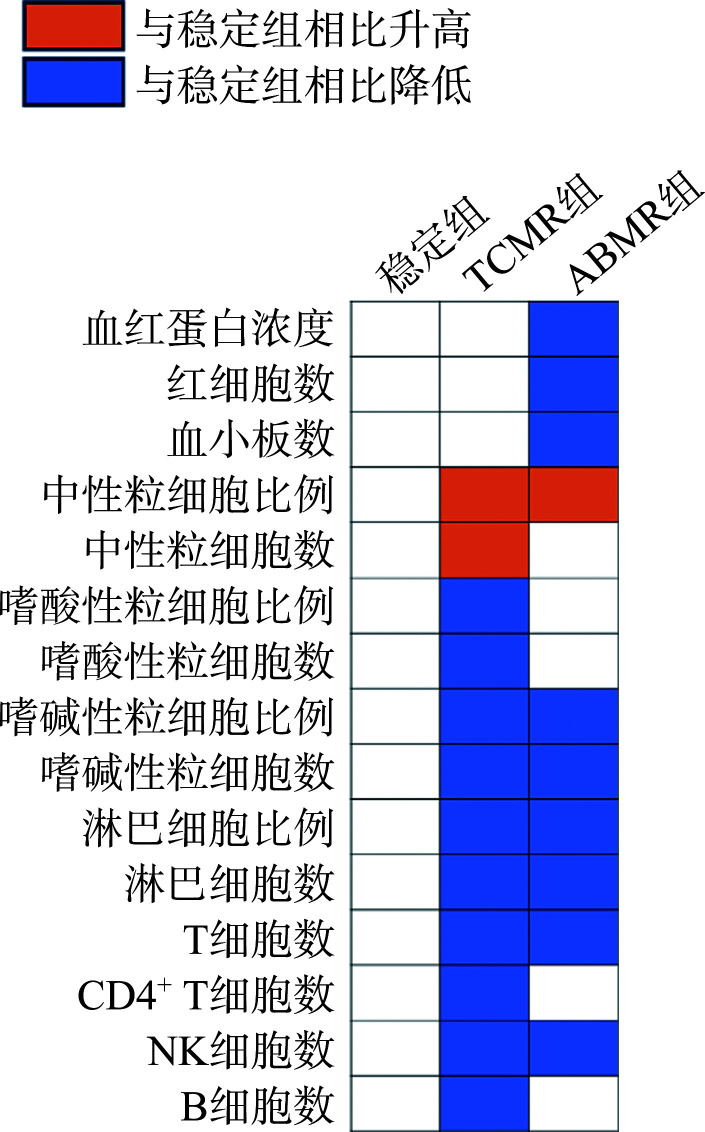

图3.

稳定组、TCMR组和ABMR组之间的血常规、淋巴细胞亚群差异性指标的变化趋势

Figure 3 Variation trend of blood routine and lymphocyte subpopulation difference indexes among the stable group, the TCMR group, and the ABMR group

TCMR: T cell-mediated rejection; ABMR: Antibody-mediated rejection; NK: Natural killer.

3. 讨 论

通过技术手段准确评估和预测患者的免疫功能状态,有助于实现个体化治疗和提升免疫相关疾病的临床诊疗效果[14]。精准的免疫风险评估是推动肾移植术后受者个体化管理的关键[7]。本研究通过分析移植肾功能稳定受者、TCMR受者和ABMR受者的临床资料,发现排斥反应发生时,TCMR受者和ABMR受者在血常规、淋巴细胞亚群方面存在诸多异同。

在本研究中,ABMR的发生显著晚于TCMR,并且发生时伴随移植肾功能的减退。TCMR主要发生于肾移植术后早期,然而随着移植术后时间的延长(>1年),ABMR变成肾移植排斥反应的主要类型[15]。与发生时间相对应,TCMR是移植术后早期移植肾失功的主要原因,而ABMR是移植术后晚期移植肾失功的主要原因[2]。

血常规是临床常规检验项目之一。本研究发现在血常规的各项指标方面,发生TCMR或ABMR的受者与移植肾功能稳定受者之间存在一些差异。ABMR受者的血红蛋白浓度以及红细胞数显著低于稳定组,并且似乎也低于TCMR组(虽然差异无统计学意义)。既往的研究[16-18]提示ABMR与血红蛋白之间存在交互作用。移植肾功能减退促进贫血的发生;而低血红蛋白浓度(<10 g/dL)是新生供者特异性抗体(donor-specific antibodies,DSA)产生的风险因素,并且低血红蛋白也是移植肾失功的独立风险因素[16-18]。研究[19-20]表明TCMR并不会影响受者的血小板数量,而ABMR受者会发生血小板数量的降低[21]。本研究发现ABMR的发生会伴随血小板的降低,但TCMR发生时不具有此类现象。此外,血小板在移植肾内聚集是ABMR病理特征之一,并且血小板的聚集与移植肾的损伤程度相关[22]。目前对于粒细胞与肾移植排斥反应的研究较少。本研究发现TCMR的发生会伴随中性粒细胞比例和数量的显著升高;ABMR的发生伴随中性粒细胞比例轻微增加。然而,其他学者[19]认为TCMR的发生并不会出现中性粒细胞数量的改变。因此,对于中性粒细胞与排斥反应的关系,需要更多的研究进行证实。对于嗜酸性粒细胞的变化,有研究[23]揭示嗜酸性粒细胞数量≥0.3×109/L是肾移植术后3个月内发生排斥反应的独立风险因素,这种风险是嗜酸性粒细胞数量<0.3×109/L受者的3倍。另有研究[24]认为嗜酸性粒细胞的增加预示着急性排斥反应的预后较差,嗜酸性粒细胞比例≥4%的急性排斥病例中37.9%的病例为不可逆性排斥反应。本研究的数据提示,在TCMR和ABMR发生时嗜酸性粒细胞比例和数量的改变存在差异,TCMR的发生伴随二者显著减少,而ABMR的发生伴随二者轻度升高。嗜酸性粒细胞比例和数量的改变或许有助于区分TCMR和ABMR。本研究发现,发生TCMR和ABMR的受者相较于稳定受者而言具有较低的嗜碱性粒细胞比例和数量。虽然暂无研究揭示嗜碱性粒细胞在肾移植受者长期生存过程中的动态变化特征,但有研究[25-26]提示嗜碱性粒细胞的减少与狼疮肾炎的发生存在关联。这提示嗜碱性粒细胞的减少可能与肾损伤存在关联。

目前,在肾移植排斥反应诊疗方面如何应用淋巴细胞亚群检测结果尚存争议。有研究[21, 27]发现发生TCMR受者和慢性ABMR受者的外周血淋巴细胞比例和数量显著降低。然而,也有研究[19]认为急性TCMR会伴有淋巴细胞比例的显著升高。本研究中的血常规结果和淋巴细胞亚群检测结果均提示TCMR和ABMR受者的淋巴细胞较稳定受者显著减少。

对于T细胞,本研究数据提示TCMR受者和ABMR受者伴有T细胞减少,并且TCMR受者伴有CD4+ T细胞数量的减少。Zhang等[28]发现发生急性TCMR受者与发生感染受者之间的CD4+ T细胞和CD8+ T细胞的数量似乎并无显著差异,这意味着急性TCMR受者可能具有较低的CD4+ T细胞和CD8+T细胞数量。研究发现:急性排斥反应的发生会导致CD4+ T细胞比例升高而CD8+T细胞的比例降低,从而出现CD4+/CD8+ T细胞比值升高[29];TCMR的发生会导致外周CD8+ T细胞比例的升高[27];急性排斥反应的发生会造成受者总T细胞数量、CD4+T细胞数量、CD4+/CD8+ T细胞比值升高[30]。有研究[21, 31]提示DSA的产生和ABMR的发生均不会影响CD4+ T细胞和CD8+ T细胞的数量。本研究结果与该研究结果相符。而另有研究[32]认为DSA的出现会导致CD4+ T细胞的比例降低,并且幼稚CD4+ T细胞比例增加以及记忆/效应CD4+ T细胞比例降低。因此,目前对于排斥反应的发生与外周血T细胞的改变之间的相关性分歧较大。

对于NK细胞,本研究发现TCMR和ABMR的发生并不影响外周血NK细胞的比例,但会伴随NK细胞数量减少。然而,有研究[28]提示急性TCMR的发生似乎并不影响NK细胞的数量。也有研究[29]认为急性排斥反应的发生会造成NK细胞比例的升高。有研究[31, 33-34]证实ABMR受者出现DSA会导致NK细胞比例和数量的减少,这种变化也许与ABMR的发生伴随移植肾内细胞毒性NK细胞的募集有关。因此,ABMR的发生伴随受者外周血NK细胞数量减少。

对于B细胞,有研究[35]证实急性排斥反应的发生伴有外周血B细胞比例及数量的减少。然而,不同的观点[36]认为虽然TCMR发生时移植肾内会浸润大量B细胞,但这并不影响外周血中B细胞的比例。本研究发现与稳定受者相比,TCMR的发生伴有B细胞数量的减少,而ABMR的发生似乎并不影响B细胞的比例和数量。对于ABMR受者中B细胞的变化趋势尚不明确,有研究[31]发现DSA的出现伴随B细胞比例的降低,而不同观点[33]认为DSA的出现不会影响B细胞的比例。结合本研究的发现以及其他研究结论,笔者推测ABMR的发生并不会导致B细胞数量的增高;此外B细胞数量的变化也许可以用于TCMR和ABMR的鉴别诊断。

综上所述,肾移植受者发生排斥反应时会伴有血常规、淋巴细胞亚群检测部分指标的变化,通过动态评估这些指标的变化可能有助于评估受者发生排斥反应的风险。此外,在发生TCMR和ABMR时,受者的血常规、淋巴细胞亚群的部分指标的变化趋势或程度存在不同,这些指标也许可以辅助鉴别TCMR和ABMR。当然,本研究也存在一些局限之处:TCMR受者和ABMR受者的样本量较小以至于无法建立预测模型;基于数据的可及性无法回顾性分析所纳入受者在排斥反应发生前的血常规、淋巴细胞亚群检测结果的动态变化过程。

基金资助

国家自然科学基金(82070774,82370760);湖南省自然科学基金(2021JJ40864,2024JJ2088)。This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation (82070774, 82370760) and the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (2021JJ40864, 2024JJ2088), China.

利益冲突声明

作者声称无任何利益冲突。

作者贡献

罗帅宇 数据收集与分析,论文撰写;聂曼华、宋磊、谢益欣、钟明达、谭书波、安荣、李潘 数据收集与分析;谭亮、谢续标 研究指导,论文修改。所有作者阅读并同意最终的文本。

Footnotes

http://dx.chinadoi.cn/10.11817/j.issn.1672-7347.2024.230543

原文网址

http://xbyxb.csu.edu.cn/xbwk/fileup/PDF/202403417.pdf

参考文献

- 1. Chong AS. Mechanisms of organ transplant injury mediated by B cells and antibodies: Implications for antibody-mediated rejection[J]. Am J Transplant, 2020, 20: 23-32. 10.1111/ajt.15844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mayrdorfer M, Liefeldt L, Wu KY, et al. Exploring the complexity of death-censored kidney allograft failure[J]. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2021, 32(6): 1513-1526. 10.1681/ASN.2020081215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Burrello J, Monticone S, Burrello A, et al. Identification of a serum and urine extracellular vesicle signature predicting renal outcome after kidney transplant[J]. Nephrol Dial Transplant, 2023, 38(3): 764-777. 10.1093/ndt/gfac259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bestard O, Cravedi P. Monitoring alloimmune response in kidney transplantation[J]. J Nephrol, 2017, 30(2): 187-200. 10.1007/s40620-016-0320-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sirolli V, Piscitani L, Bonomini M. Biomarker-development proteomics in kidney transplantation: an updated review[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2023, 24(6): 5287. 10.3390/ijms24065287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dendle C, Mulley WR, Holdsworth S. Can immune biomarkers predict infections in solid organ transplant recipients? A review of current evidence[J]. Transplant Rev, 2019, 33(2): 87-98. 10.1016/j.trre.2018.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. 郑瑾, 薛武军. 肾移植排斥反应免疫风险评估与监测[J]. 器官移植, 2021, 12(6): 643-650. 10.3969/j.issn.1674-7445.2021.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; ZHENG Jin, XUE Wujun. Assessment and monitoring of immune risk of kidney transplantation rejection[J]. Organ Transplantation, 2021, 12(6): 643-650. 10.3969/j.issn.1674-7445.2021.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. 中华医学会健康管理学分会 . TBNK淋巴细胞检测在健康管理中的应用专家共识[J]. 中华健康管理学杂志, 2023, 17(2): 85-95. 10.3760/cma.j.cn115624-20221126-00861. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; Chinese Medical Association Branch of Health Management . Expert consensus on the application of TBNK lymphocytes detection for health management[J]. Chinese Journal of Health Management, 2023, 17(2): 85-95. 10.3760/cma.j.cn115624-20221126-00861. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. 中华医学会器官移植学分会 . 肾移植组织配型及免疫监测技术操作规范(2019版)[J]. 器官移植, 2019, 10(5): 513-520. 10.3969/j.issn.1674-7445.2019.05.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; Branch of Organ Transplantation of Chinese Medical Association . Technical operation specification for tissue matching and immune monitoring techniques in renal transplantation (2019 edition)[J]. Organ Transplantation, 2019, 10(5): 513-520. 10.3969/j.issn.1674-7445.2019.05.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. 马锡慧, 韩永, 李彬钰, 等. 肾移植术后稳定状态受者淋巴细胞亚群的动态变化及其与肾功能的相关性分析[J]. 器官移植, 2020, 11(5): 559-565. 10.3969/j.issn.1674-7445.2020.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; MA Xihui, HAN Yong, LI Binyu, et al. Dynamic changes of lymphocyte subsets and their correlation with renal function in recipients with stable graft status after renal transplantation[J]. Organ Transplantation, 2020, 11(5): 559-565. 10.3969/j.issn.1674-7445.2020.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Haas M, Loupy A, Lefaucheur C, et al. The Banff 2017 Kidney Meeting Report: Revised diagnostic criteria for chronic active T cell-mediated rejection, antibody-mediated rejection, and prospects for integrative endpoints for next-generation clinical trials[J]. Am J Transplant, 2018, 18(2): 293-307.10.1111/ajt. 14625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Loupy A, Haas M, Solez K, et al. The Banff 2015 kidney meeting report: current challenges in rejection classification and prospects for adopting molecular pathology[J]. Am J Transplant, 2017, 17(1): 28-41. 10.1111/ajt.14107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Levey AS, Coresh J, Balk E, et al. National Kidney Foundation practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification[J]. Ann Intern Med, 2003, 139(2): 137-147. 10.7326/0003-4819-139-2-200307150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Forlin R, James A, Brodin P. Making human immune systems more interpretable through systems immunology[J]. Trends Immunol, 2023, 44(8): 577-584. 10.1016/j.it.2023.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Halloran PF, Chang J, Famulski K, et al. Disappearance of T cell-mediated rejection despite continued antibody-mediated rejection in late kidney transplant recipients[J]. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2015, 26(7): 1711-1720. 10.1681/ASN.2014060588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jouve T, Noble J, Naciri-Bennani H, et al. Early blood transfusion after kidney transplantation does not lead to dnDSA development: the BloodIm study[J]. Front Immunol, 2022, 13: 852079. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.852079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pascual J, Jiménez C, Franco A, et al. Early-onset anemia after kidney transplantation is an independent factor for graft loss: a multicenter, observational cohort study[J]. Transplantation, 2013, 96(8): 717-725. 10.1097/TP.0b013e31829f162e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Okumi M, Okabe Y, Unagami K, et al. The interaction between post-transplant anemia and allograft function in kidney transplantation: The Japan Academic Consortium of Kidney Transplantation-II study[J]. Clin Exp Nephrol, 2019, 23(8): 1066-1075. 10.1007/s10157-019-01737-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Naranjo M, Agrawal A, Goyal A, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio predict acute cellular rejection in the kidney allograft[J]. Ann Transplant, 2018, 23: 467-474. 10.12659/AOT.909251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. 陈树汉, 付绍杰, 于立新, 等. 肾移植术受者急性排斥反应发生前后血小板参数变化及其意义 [J]. 山东医药, 2018, 58(23): 73-75. 10.3969/j.issn.1002-266X.2018.23.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; CHEN Shuhan, FU Shaojie, YU Lixin, et al. Changes in platelet parameters before and after acute rejection in renal transplant recipients and their significance[J]. Shandong Medical Journal, 2018, 58(23): 73-75. 10.3969/j.issn.1002-266X.2018.23.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shahi A, Salehi S, Afzali S, et al. Evaluation of thymic output and regulatory T cells in kidney transplant recipients with chronic antibody-mediated rejection[J]. Biomed Res Int, 2021, 2021: 6627909. 10.1155/2021/6627909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kuo HH, Fan R, Dvorina N, et al. Platelets in early antibody-mediated rejection of renal transplants[J]. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2015, 26(4): 855-863. 10.1681/ASN.2013121289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Colas L, Bui L, Kerleau C, et al. Time-dependent blood eosinophilia count increases the risk of kidney allograft rejection[J]. EBioMedicine, 2021, 73: 103645. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Weir MR, Hall-Craggs M, Shen SY, et al. The prognostic value of the eosinophil in acute renal allograft rejection[J]. Transplantation, 1986, 41(6): 709-712. 10.1097/00007890-198606000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liang PF, Tang Y, Lin L, et al. Low level of circulating basophil counts in biopsy-proven active lupus nephritis[J]. Clin Rheumatol, 2018, 37(2): 459-465. 10.1007/s10067-017-3858-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Charles N, Chemouny JM, Daugas E. Basophil involvement in lupus nephritis: a basis for innovation in daily care[J]. Nephrol Dial Transplant, 2019, 34(5): 750-756. 10.1093/ndt/gfy245.PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ko EJ, Seo JW, Kim KW, et al. Phenotype and molecular signature of CD8+ T cell subsets in T cell-mediated rejections after kidney transplantation[J/OL]. PLoS One, 2020, 15(6): e0234323[2023-11-05]. 10.1371/journal.pone.0234323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhang QQ, Xie YL, Zhang WJ, et al. Lymphocyte function based on IFN-γ secretion assay may be a promising indicator for assessing different immune status in renal transplant recipients[J]. Clin Chim Acta, 2021, 523: 247-259. 10.1016/j.cca.2021.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. 王旭珍, 薛武军, 田晓辉, 等. 肾移植后淋巴细胞亚群的变化及其对诊断急性排斥反应和CMV感染的意义[J]. 中华器官移植杂志, 2013, 34(11): 651-654. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-1785.2013.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; WANG Xuzhen, XUE Wujun, TIAN Xiaohui, et al. Clinical application of lymphocytes subsets monitoring in differential diagnosis of acute rejection and CMV infection in kidney transplant recipients[J]. Chinese Journal of Organ Transplantation, 2013, 34(11): 651-654. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-1785.2013.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. 尚文俊, 杨先雷, 王志刚, 等. 淋巴细胞亚群与肾移植术后感染及排斥反应的关系[J]. 中华器官移植杂志, 2017, 38(6): 353-358. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-1785.2017.06.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; SHANG Wenjun, YANG Xianlei, WANG Zhigang, et al. Relationship between lymphocyte subsets with infection and rejection after renal transplantation[J]. Chinese Journal of Organ Transplantation, 2017, 38(6): 353-358. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-1785.2017.06.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fischman C, Fribourg M, Fabrizio G, et al. Circulating B cells with memory and antibody-secreting phenotypes are detectable in pediatric kidney transplant recipients before the development of antibody-mediated rejection[J/OL]. Transplant Direct, 2019, 5(9): e481[2023-11-18]. 10.1097/TXD.0000000000000914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Louis K, Macedo C, Bailly E, et al. Coordinated circulating T follicular helper and activated B cell responses underlie the onset of antibody-mediated rejection in kidney transplantation[J]. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2020, 31(10): 2457-2474. 10.1681/ASN.2020030320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Crespo M, Yelamos J, Redondo D, et al. Circulating NK-cell subsets in renal allograft recipients with anti-HLA donor-specific antibodies[J]. Am J Transplant, 2015, 15(3): 806-814. 10.1111/ajt.13010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Louis K, Macedo C, Lefaucheur C, et al. Adaptive immune cell responses as therapeutic targets in antibody-mediated organ rejection[J]. Trends Mol Med, 2022, 28(3): 237-250. 10.1016/j.molmed.2022.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Alfaro R, Legaz I, González-Martínez G, et al. Monitoring of B cell in kidney transplantation: development of a novel clusters analysis and role of transitional B cells in transplant outcome[J]. Diagnostics, 2021, 11(4): 641. 10.3390/diagnostics11040641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Heidt S, Vergunst M, Anholts JDH, et al. Presence of intragraft B cells during acute renal allograft rejection is accompanied by changes in peripheral blood B cell subsets[J]. Clin Exp Immunol, 2019, 196(3): 403-414. 10.1111/cei.13269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]