Abstract

Textile-toxic synthetic dyes, which possess complex aromatic structures, are emitted into wastewater from various branches. To address this issue, the adsorption process was applied as an attractive method for the removal of dye contaminants from water in this article. An unprecedented integrated experimental study has been carried out, accompanied by theoretical simulations at the DFT-B3LYP/6-31G (d,P) level of theory to investigate how single Maxilon Blue GRL (MxB) dye or and its mixture with MG (Malachite Green) dyes interact with the adsorbent and compare the obtained results with the data obtained through experimentation. The full geometry optimization revealed the physical adsorption of dyes on the Al2O3 surface. Non-linear optical properties (NLO) results emphasized that the complex MG-Al2O3-MxB is a highly promising material in photo-applications, and the adsorbed binary system is energetically more favorable compared to the adsorbed sole dye system. The experimental results for (MxB) dye adsorption onto γ-Al2O3 affirmed that the optimum conditions to get more than 98% uptake were at dye concentration 100 ppm, pH 10, adsorbent content 0.05 g, and equilibrium time only 20 min. The kinetic and isothermal studies revealed that the adsorption accepted with the pseudo-second-order and Freundlich isotherm model, respectively. The removal efficiency of the mixture of MxB and MG dyes was the highest but did not change clearly with increasing the % of any of them. The details of the interaction mechanisms of the sole and binary dyes were proven.

Keywords: Adsorption, DFT studies, Al2O3, Maxilon blue dye, Mechanism

Subject terms: Catalysis, Environmental chemistry, Theoretical chemistry

Introduction

Undoubtedly, today's environmental pollutants, specifically water pollution, are deemed huge obstacles mankind confronts. Water pollution necessitates a primary and inherent resolution due to its status as one of the most severe ecological predicaments. As an additional illustration, the textile industry generates a substantial quantity of effluent, which comprises numerous undesirable substances, such as corrosive dissolved solids, acidic and poisonous organic or inorganic compounds. A great number of dyes are hazardous and toxic to organisms, and they have the potential to induce a range of illnesses, including those suspected to be carcinogenic and mutagenic impact1,2. Various industrial sectors, particularly the dye manufacturing and textile finishing branches, release these substances into wastewater3. The textile synthetic dyes are derived not only from the food coloring, cosmetics, paper, and carpet industries but also from a variety of complex aromatic structures. These dyes possess intricate physico-chemical, thermal, and optical properties4,5. Azo dyes, for instance (MxB) has one or more nitrogen to nitrogen double bonds [–N=N–) and constitute a significant portion of dyes that are used in the textile industry6–8. Malachite green (MG) is a cationic dye pertinence to triphenylmethane group and its shining green color makes it appropriate for dyeing in different industries9,10. There are many ways to get rid of excess textile dye from water, one of this ways is the adsorption, reverse osmosis, and ultra-filtration, etc.11–17. Among others, the sorption process provides an attractive alternative for the treatment of contaminated water, especially if the sorbent is inexpensive and does not require an additional pretreatment step (such as activation) before its application4,18. Moreover, the utilization of this procedure, wherein the adsorbent content is kept at a minimum, becomes imaginable when dealing with diluted concentrations of contaminants in water. However, a complication arises when attempting to address the issue of water pollution caused by the presence of multiple dye types. Up until now, various academic institutions have endeavored to engineer novel adsorbents or modify existing ones in order to effectively remove a combination of cationic and/or anionic dyes, acting as organic pollutants, from the contaminated water17–20. Nevertheless, a lot of these adsorbents have several disadvantages in terms of high cost and difficulty of their preparation, so, in this article, the authors try to examine the adsorption process for a mixture of dyes over a cheap and easily prepare among all adsorbents as alumina. Alumina with numerous structural phases, namely α, β, γ, η, θ, κ, and χ is a well-known metal oxide, one of the special functional materials and common adsorbents used in environmental engineering and in a wide range of applications, including the electronics, metallurgy, optoelectronics, catalyst carrier, and fine ceramics, owing to its high purity, tiny particle size, uniform distribution, and high surface area21,22. On the other hand, compared to other powders, alumina powder is more pH sensitive since it is an amphoteric oxide. As a result, it's critical to keep the pH level and solution concentration consistent throughout the reaction solution. Recently, many studies about alumina have been conducted to examine its adsorption ability to remove pollutants as single cationic or anionic dyes from wastewater21,22. The majority of these investigations have mostly concentrated on increasing the dye's ability to be adsorbed on the adsorbent surface. Conversely, limited studies have been proceeded on the adsorption of mixtures of organic dyes on the alumina material. Further, neither experimental nor theoretical studies have been performed on alumina as an adsorbent for the adsorption of single MxB or its mixture with other cationic dyes from aqueous solution. Moreover, there is a lack of a thorough knowledge of the behavior of the interactions between the alumina adsorbent and the single dye, such as MxB or binary cationic dyes, in comparison to the experimental adsorption data. Herein, aiming to overcome these shortages, a great deal of information about the adsorption process and the interactions involved may be gained from quantum chemical simulations. Additionally, density functional calculations will be used to evaluate the plausibility of the adsorption of mixed dyes; geometrical features, electronic structures, and the adsorption properties of the interacting systems have all been thoroughly investigated. To bridge gaps from earlier studies and enhance the understanding of adsorption mechanisms, this work will be use the density functional theory in conjunction with the classical isotherm and kinetic models to provide a deeper description of the adsorption mechanism of single and binary dye molecules onto the solid adsorbent. Finally, it can be concluded that (DFT) theory has turned into a powerful and missionary tool to: (i) achieve the properties of a “functionalized” material to remove mixtures of cationic dyes; (ii) foresee the feasibility of adsorption of a particular adsorbent targeting a certain adsorbate and understanding of these molecular interactions23; and (iii) Investigate the nonlinear- optical properties of the resulted complexes after adsorption process. To the best of our knowledge, there is no report on the NLO properties of the complex MG-Al2O3-MxB.

The novelty of this paperwork will be appeared in evaluating the simulation study by (DFT) calculations for the behavior of the interactions between single or binary cationic dyes and the (γ-Al2O3) nanoparticles adsorbent against the experimental adsorption data. The Global reactivity Descriptors and NLO properties will be investigated theoretically. The detailed reaction mechanism for the dual system is going to be postulated. Experimentally, different parameters to determine the optimum condition toward (MxB) adsorption, like dye concentration, adsorbent content, pH, contact time, the kinetic and isotherm models will be studied.

Experimental study

Materials

Malachite Green (molecular formula C52H54N4O12; molecular weight: 927.02 g/mol and λmax = 617 nm) and Maxilon Blue GRL (molecular formula C20H26N4O6S2; molecular weight: 482.57 g/mol and λmax = 609 nm) were purchased from DyStar. Al (NO3)3 and analytical grade (NH4)2CO3 were purchased from (Merck) and (Win Lab), respectively, and distilled water was used throughout the studies.

Preparation of adsorbent

The sample of alumina was prepared by the precipitation method and it is worth mentioning that the applied adsorbent in this work has already been reported previously, evaluated using X-ray diffractometer, the surface area (SBET), and pore volume measurements24. Briefly, a solution of aluminum nitrate was prepared, and NH4CO3 (1M) was added slowly to the solution with stirring until a precipitate was composed at pH 7 with stirring for one hour. Then, the precipitate filtration and drying were performed at 120 °C. Finally, the solid was calcined at 500 °C for 3 h and was nominated as Al-2.

Characterization of adsorbent

For an additional estimate, the morphology of the adsorbent and its nanostructure are characterized by TEM (Jeol 2100).

Adsorption studies

Single dye

Adsorption study of MxB on Al-2 was carried out in batch mode, where a fixed amount of 100 mg of (Al-2) adsorbent was inserted into 100 mL of the dye solution (initial concentration: 100 mg/L). The stirring of the obtained dye solution continued at the wanted temperature and pH . At different time intervals, the solution was taken out, centrifuged for 15 min (at 7000 rpm), and the absorbance was specified by a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Jasco V-550, Japan) at λ ranging from 400 to 800 nm, with the maximum value obtained at 609 nm. The percentage of MxB dye removal and its adsorbed amount per unit adsorbent (mg/g) were calculated by applying Eqs. (1) and (2), respectively:

| 1 |

| 2 |

where V is the solution volume (L), Co is the initial concentration (mg/L) of the dye, Ce is the equilibrium concentration of the dye in solution (mg/L), m is the weight of ɤ-alumina (g), and qe is the adsorption capacity (mg/g). Then, studying the effect of different factors that have an influence on the removal percentage of MxB was done. The first one is the impact of pH ranging between 4 and 10, with an adsorbent dose of 0.1 g at room temperature, an initial MxB dye concentration 100 mg/L, and contact time (0–180). The second factor is the influence of the initial MxB dye concentration (10, 25, 50, 75, and 100 ppm) performed with an adsorbent dose 0.1 g at room temperature, pH 10, and at equilibrium time (20 min). Further, studying the impact of adsorbent doses (0.03, 0.05, and 0.1 g for 100 mg/L MxB dye solution, at pH 10, room temperature, and equilibrium contact time (20 min). Finally, the kinetics of MxB adsorption and the adsorption isotherms were investigated.

Mixed dyes

An adsorption study of binary MxB and MG dyes on Al-2 was conducted in batch mode under the following conditions: initial concentration (50 ppm), pH 7, and a fixed amount of 0.1 g of adsorbent. The adsorption procedure was consistent with what was previously described in the section on single-dye adsorption. Additionally, different ratios of (1MxB: 1MG), (1MG: 2MxB), and (2MG: 1MxB) were examined. The percentage of removal and adsorption capacity for the various mixed dye ratios were calculated using Eqs. (1) and (2), respectively.

Results and discussion

DFT theoretical study for adsorption of single MxB and mixture of two cationic (MxB + MG) dyes

Ground state and geometrical parameters

Firstly, in this part, theoretical simulation of MxB adsorption on alumina as an individual cationic dye was done, followed by studying the theoretical adsorption of MxB and MG as a mixture of two cationic dyes in a binary system to get the most stable configuration of the dyes on alumina. The single system of MG adsorption alone on alumina was studied earlier24. Once the determination of the configurations of MxB and MG on Al2O3 was achieved, the calculation of the adsorption energy of these dye molecules on the adsorbent was performed. Additionally, the calculation of the dipole moment, which serves as an estimation of the molecule's polarity and reflects the extent of charge distribution within the molecular system, was performed. To analyze the structural geometry of the sole MxB cationic dye in the gas phase, a complete geometry optimization was conducted. This optimization encompassed the optimized bond lengths, bond angles, and natural charges, employing the B3LYP/6-31G (d, p) method, as presented in Table S1 "see supplementary data". The geometrical optimization parameters and the natural charges of single MxB-Al2O3 were inserted in Table S2 "see supplementary data". The obtained results revealed that the optimized structure for a single MxB dye adsorbed on alumina is planar. Further, Table 1 includes the measured values of total energy, EHOMO (highest occupied molecular orbital energy), ELUMO (lowest unoccupied molecular orbital energy), energy gap, and dipole moment for the reacting MxB and/or MG dyes with Al2O3, according to the frontier molecular orbital (FMO) theory of chemical reactivity. This table showed that the Al2O3 adsorbent revealed a high tendency to donate electrons to an appropriate acceptor molecule with low energy or an empty electron orbital, in our case as a single MxB or mixed with MG dye. Fig. 1 illustrates the HOMO and LUMO of MxB orbitals. The energy of the LUMO indicates the susceptibility of molecules to nucleophilic attack. Density Functional Theory has become a successful way to obtain a better understanding of chemical reactivity and stability about molecules, the HOMO-LUMO energy gap (c.f. Table 1 and Fig. 1) refer to the difference between the HOMO and LUMO energy values, which indicated that the charge transfer interaction taking place within the molecule (MxB-Al2O3) was lower (means at the end of the adsorption process), but it had the highest value at the initial time for the adsorbent and adsorbate molecules.

Table 1.

Total energy, energy of HOMO, LUMO, energy gap, and natural charge of MxB, Al2O3 and MxB-Al2O3 computed at B3LYP/6-31G (d,P) level of theory.

| Compounds | Maxilon blue (MxB) | Al2O3 | MxB-Al2O3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| ET (au) | − 1505.31 | − 710.60 | − 3717.68 |

| EHOMO (eV) | − 8.19 | − 7.55 | − 2.79 |

| ELUMO (eV) | − 5.79 | − 3.59 | − 2.19 |

| Egap (eV) | 2.39 | 3.95 | 0.59 |

| B.E (a.u.) = EMxB-Al2O3 − (EMxB + EAl2O3(= − 3717.67813972 – (− 1505.306*2 + − 710.599) = 3.53 | |||

| µ (Debye) | 4.57 | 0 | 18.43 |

| Ionization potential (I = − EHOMO) eV | 8.19 | 7.55 | 2.79 |

| Electron affinity (A = − ELUMO) eV | 5.79 | 3.59 | 2.19 |

| Electronegativity χ = (I + A)/2) eV | 6.99 | 5.57 | 2.49 |

| Chemical potential p = (− χ) eV−1 | − 6.99 | − 5.57 | − 2.49 |

| Chemical hardness (η = (I − A)/2) ev | 1.20 | 1.98 | 0.30 |

| Chemical softness (S = 1/2η) eV−1 | 0.42 | 0.25 | 1.68 |

| Electrophilicity index (ω = p2/2η) eV | 20.43 | 7.85 | 10.43 |

Figure 1.

Optimized structure, numbering system, vector of dipole moment of Al2O3, MxB and MxB-Al2O3, HOMO, LUMO maps and energy gap of MxB using B3LYP 6-31G (d,p) level of theory.

Global reactivity descriptors

At the B3LYP/6-31G (d, p) level of theory, electron affinity (A, eV), ionization potential (I, eV), chemical hardness (, eV), the chemical potential (V, eV−1), electronegativity (, eV), global softness (S, eV−1) and global electrophilicity index, (ω, eV) of individual (MxB), Al2O3, and MxB-Al2O3 were computed and mentioned in Table 1. In general, molecules characterized by a minimal energy difference are ascribed to promoting chemical reactivity, lowering kinetic stability and are also known as soft molecules; on the other hand, those with a large energy gap have higher stability and are looked as hard molecules because they resist charge transfer and changes in their electron density and distribution. The energy of HOMO is directly connected to the ionization potential (IP = − EHOMO), but the energy of LUMO is attached with the electron affinity (EA = − ELUMO). Additionally, by utilizing these values, attractive properties such as electronegativity (χ), chemical hardness (η), electrophilicity index (ω), and electronic chemical potential (V) can be given. It is known that the difference in electronegativity between adsorbent (alumina) and adsorbate (MxB dye) reflected a stronger aggressiveness of nucleophilic attack that can promote adsorption capacity (as shown in Table 1).

Non-linear optical properties (NLO)

As no experimental or theoretical investigation has been conducted to examine the nonlinear optical properties of these types of dyes, our research interest is directed towards undertaking this study. Due to its importance in providing crucial optical modulation, switching, laser, frequency shifting, fiber, optical materials logic, and optical memory for new technologies such as telecommunications, optical interconnections, and signal processing, NLO is at the forefront of current research25,26. In order to investigate the relation between molecular structure and NLO, the polarizabilities and hyperpolarizabilities of the studied MxB cationic dye, Al2O3, MxB-Al2O3, and the binary system complex are calculated using the B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) level of theory. The mean polarizability α, the anisotropy of the polarizability Δα and the mean first-order hyperpolarizability (β) were mentioned in Table 2. The polarizabilities and first- order hyperpolarizabilities are called in atomic units (a.u.), the calculated values have been transformed into electrostatic units (esu) using a conversion factor of 0.1482 × 10–34 esu27 for α and 8.6393 × 10–33 esu28 for β. In the NLO research, the standard prototype P-nitro aniline (PNA) is used. As there were no experimental values for the NLO characteristics of the molecules under research, PNA was used in this work as a reference. The magnitude of the molecular hyperpolarizability β is one of the key factors in NLO system. The analysis of the β parameter for the studied molecules showed that MxB is 61 times greater than PNA, the complex MxB-Al2O3 is 125 times greater than PNA, and the complex MG-Al2O3-MxB is 534 times greater than PNA, implying their hopeful applications as NLO materials. The variation of Hyper-Rayleigh scattering (β HRS) and the depolarization ratio (DR) appearing in Table 2 can be rationalized by complexation and structural evidence29. The high value of β and DR in the MxB form and the lowest value in the case of Al2O3 (c.f. Table 2) confirmed the long bond length between the N-atom of MxB and the O-atom of Al-oxide 30 and hence weak bonding, resulting in a physisorption process.

Table 2.

The total mean polarizability (<α˃), the anisotropy of the polarizability (Δα), and the mean first-order hyperpolarizability (<β˃), of cationic MxB, Al2O3, MxB-Al2O3 and MG-Al2O3-MxB computed at B3LYP/6-31G(d,P).

| Property | PNA | MxB | Al2O3 | MxB-Al2O3 | MG-Al2O3-MxB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <α > × 10−24esu | 22 | − 11.79 | − 7.29 | − 47.20 | − 50.23 |

| Δα × 10−24esu | 28.58 | 6.77 | 20.94 | 9.01 | |

| <β>× 10−24esuc | 15.5 | 948.52 | 0 | 1943.22 | 8282.07 |

| DR | 0.16 | 0 | 0.07 | 0.004 | |

| βHRS | 41.06 | 0 | 174.87 | 74.03 |

Theoretical study for the interaction of cationic dyes with Al2O3

Maxilon Blue (GRL)

From the theoretical study, the difference in the electronegativity and the other calculated parameters, we can predict the theoretical interaction between MxB and alumina. This interaction has been attributed to electrostatic forces between the cationic ion groups (–N+) of MxB and the negatively charged ion groups (–Al–O−) on the alumina surface. As the MxB molecule possesses an N atom that is positively charged, which facilitates the adsorption on Al2O3 surface. It is due to the lone pair on the N atom being delocalized over the ring, which makes the electrons less available and hence more subjected to attack by nucleophiles. The outcome is a creation of an electrostatic interaction between a positively charged N atom of MxB and a negative O atom in alumina. In the present study, two molecules of the cationic MxB and one molecule of Al2O3 have been used to form MxB-Al2O3 complex. The studied MxB, Al2O3 and MxB-Al2O3 complex were optimized at the B3LYP/6-31G (d, p) level of theory. The optimized bond length N–O between MxB (N) and the Al-oxide (O) was 1.37829 Å (literature experimental N–O is 1.1–1.36 Å31) "Table S2". The intensity of the contact between the MxB and Al surface decreases as the N–O bond increases, and as a result, the adsorption is physical. The optimum bond length between dye and oxide is larger than the experimental one, as revealed by the theoretical calculation, which supports the physisorption process.

Binary maxilon blue (GRL) and malachite green

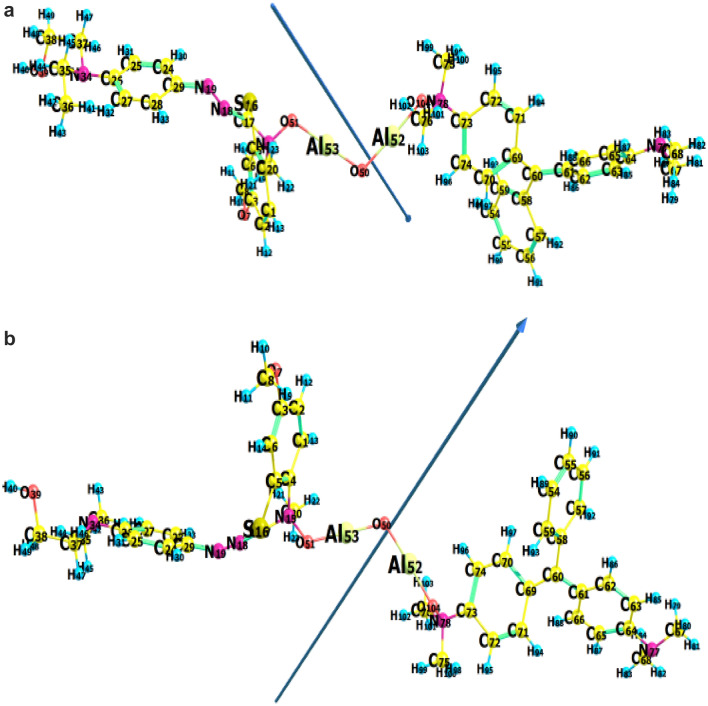

The studied MG-Al2O3-MxB complex was optimized at the B3LYP/6-31G (d, p) level of theory. The optimized bond lengths, bond angles, dihedral angles, and the vector of the dipole moment are presented in Fig. 2 and Table S3 "see supplementary data". It was clear from the obtained results of dihedral angles that the optimized structure of the binary adsorbed system was non-planar. Also, the total energy, energy of HOMO and LUMO, energy gap, binding energy (a.u.), dipole moment, the ionization potential (I, eV), electron affinity (A, eV), chemical hardness (η, eV), global softness (S, eV−1), chemical potential (V, eV−1), electronegativity (χ, eV), and global electrophilicity index, (ω, eV), of MG-Al2O3-MxB were estimated and listed in Table 3. Many theoretical reactivity descriptor parameters, such as EHOMO, ELUMO, energy gap, global softness, and dipole moment, are used in discussing the mechanism of chemical reactions. It is known that the molecule EHOMO reflects its electron-donating ability, while the ELUMO represents its electron-accepting ability32. In Tables 1 and 3, it is clear that the EHOMO, ELUMO, energy gap, electronegativity, ionization potential, and chemical softness values for the two cationic MxB and MG dyes are relatively close together. So, these data referred that there is no preferable dye in the mixed binary system for adsorbing over alumina. Further, the dipole moment μ (Debye) and the electrophilicity ω (eV) reflect the polarity of the whole molecule, so higher the dipole moment, the electrophilicity values, the high chemical reactivity will be obtained. Tables 1 and 3 showed that the sole MxB dye had a higher dipole moment value (4.57 Debye) and electrophilicity values (20.43 eV) than the MG dye (3.19 Debye and 18.36 eV, respectively). Therefore, the MxB dye is the most electrophilic dye and consequently will be adsorbed first.

Figure 2.

(a) Optimized structure, numbering system, vector of dipole moment, HOMO, LUMO maps and energy gap of MG-Al2O3-MxB calculating at B3LYP 6-31G (d,p) level of theory. (b) Optimized structure, numbering system and vector of dipole moment of MxB-Al2O3-MG.

Table 3.

Total energy, energy of HOMO, LUMO, energy gap, dipole moment, the ionization potential (I, eV), electron affinity (A, eV), chemical hardness (η, eV), global softness (S, eV−1), chemical potential (V, eV−1), electronegativity (χ, eV), and global electrophilicity index (ω, eV) of MG-Al2O3, MxB-Al2O3 and MG-Al2O3-MxB computed at B3LYP/6-31G (d,P) level of theory.

| Parameters | MG24 | MG-Al2O3 | MxB-Al2O3 | MG-Al2O3-MxB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ET (a.u) | − 1000.84 | − 2712.54 | − 3717.68 | − 3216.97 |

| EHOMO (a.u) | − 8.19618 | − 3.17 | − 2.79 | − 3.68 |

| ELUMO (a.u) | − 5.60374 | − 2.82 | − 2.19 | − 2.90 |

| Energy gap = (EHOMO − ELUMO) eV | 2.59 | 0.35 | 0.59 | 0.78 |

| B.E (a.u.) = EMG-Al2O3-MxB − (EAl2O3-MG + EAl2O3-MxB (= − 3216.967 – (− 2712.543/2 + − 3717.678/2) = − 1.86 | ||||

| Dipole moment μ (debye) | 3.190 | 10.21 | 18.43 | 4.97 |

| Ionization potential (I = − EHOMO) eV | 8.20 | 3.17 | 2.79 | 3.68 |

| Electron affinity (A = − ELUMO) eV | 5.60 | 2.82 | 2.19 | 2.90 |

| Electronegativity χ = (I + A)/2 eV | 6.90 | 2.99 | 2.49 | 3.29 |

| Chemical potential p = − χ eV | − 6.90 | − 2.99 | − 2.49 | − 3.29 |

| Chemical hardness (η = (I − A)/2) ev | 1.30 | 0.17 | 0.30 | 0.39 |

| Chemical softness (S = 1/2η) eV | 0.39 | 2.87 | 1.68 | 1.28 |

| Electrophilicity index ω = p2/2η eV | 18.36 | 25.75 | 10.43 | 13.87 |

From the theoretical study and calculated parameters, we can propose the theoretical interaction between the mixed cationic dyes MxB and MG with alumina. As shown from the structure of cationic MxB (Fig. 1), it has an appositively charged N atom and the cationic MG also has an appositively charged N atom on its skeleton. On the other hand, alumina possesses two negative oxygen atoms, therefore, in this system; electrostatic forces are generated when the MG and MxB ratio (1:1) exist with alumina. So, we can say the interaction occurs due to the attraction force between the positive center (–N-atom) of one (MG) molecule with one negatively charged oxygen atom in alumina, and the second negative oxygen atom in alumina attracts the positive –N-atom of (MxB) dye (one molecule). So, this interaction has been assigned to electrostatic forces between the cationic groups (–N+) of MxB and MG (equal ratio) and the negatively charged groups (-Al-O-) on the alumina surface and a single bond is formed between the negative oxygen atoms and positive nitrogen atoms in the system (Fig. 2). The optimized bond length as shown in Table S2, N–O between MxB (N) and the Al-oxide (O), N–O between MG (N) and the Al-oxide is 1.38606 Å (literature experimental N–O is 1.1–1.36 Å31). It is clear that the increase in the N–O bond between MxB and alumina surface, MG and alumina surface decreased the strength of the interaction, so, physisorption process was confirmed for the mixture of cationic dyes as occurs in the individual dyes and this is a good point in the adsorption as the presence of other dyes doesn’t impact on the efficiency of adsorption. This result may be related to the excellent surface we use for the adsorption and conciliation in selection of adsorbent.

Moreover, in order to construe the stability of the adsorbed dye molecules at various adsorption sites, the adsorption energy Eads (Binding Energy) of each model is calculated according to the following formula:

| 3 |

where Etotal, E adsorbent surface, and E dye molecule are the total energies of the adsorbed system, the clean Al2O3 surface, and the isolated dye molecule before adsorption, respectively. Accordingly, the stability of the adsorbed molecules after adsorption will be examined based on the positive or negative adsorption energy. In other words, if the adsorption energy is negative, the adsorption process releases heat, indicating that the adsorbed molecule is more stable after adsorption, and vice versa. Consequently, the adsorption energy of those sole and mixed dye molecules onto Al2O3 was calculated through B.E. Equation (3) 33 (c.f. Tables 1 and 3). The obtained results demonstrated that the negative adsorption energy for the binary system (− 1.86 a u) reflected that the adsorbed binary system is energetically more favorable compared to the adsorbed single dye system. So, this result represented that the stability of the adsorbed molecules can be arranged as the following: (Al2O3-MxB) < (MG-Al2O3) < (MG-Al2O3-MxB).

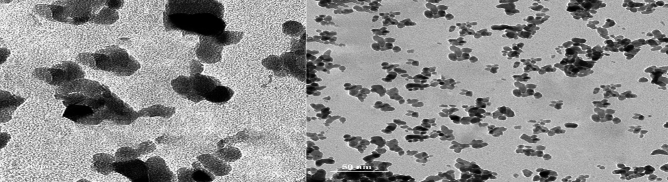

Morphology of alumina sample

TEM analysis was applied to confirm the actual particle size of alumina which is at the nanoscale (6.25 nm), applicable to X-ray data (4.1 nm)24 and represented spherical pores shape as shown in Fig. 3. Also, TEM picture showed very good dispersion and less agglomeration, which will expect to enhance the dye adsorption process.

Figure 3.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) pictures of γ-Al2O3.

Experimental study for impact of different factors on MxB dye removal

Contact time and pH of MxB dye solution

To apply this adsorption process in an industrial ambience, the minimum contact time is preferable for cleaning the dye solution with a high degree of purity. So, the impact of contact time on the adsorption of MxB onto the applied adsorbent at various pH values of MxB solutions is shown in Fig. 4a. The figure represented that the elimination of the MxB dye increased by passing the contact time to the equilibrium for all studied adsorption experiments at different pH values for the dye solution. Because of the availability of more vacant adsorption sites and the easiest penetration of MxB molecules into the mesopores of the adsorbent; the adsorption process of the MxB onto alumina adsorbent was rapid at the premier stages of the contact duration. Then, as the contact time enhanced, the adsorption sites became less available and a slower adsorption phase was reached until equilibrium after only 20 min.

Figure 4.

Impact of (a) contact time of (MxB) dye solution with different pH, (b) pH of (MxB) dye at equilibrium time on its removal % (adsorbent dose 0.1 g, room temp., initial dye conc. 100 mg/L), (c)concentration of (MxB) dye solution (adsorbent dose 0.1 g at room temp., pH 10, and at equilibrium time), and (d) adsorbent dose (pH 10, room temp., initial dye conc. 100 mg/L, and at equilibrium contact time), on the adsorption capacity of MxB dye.

Figure 4b illustrated the study of the MxB solution's adsorption behavior on ɤ-alumina at pH values of 4 ("acid media"), 7 ("neutral"), and 10 ("an alkaline medium"). The results showed that the pH of the dye solution had a significant impact on the adsorption process; the percent of purification of the solution ranged from a low of 49 percent at pH 4 to a maximum of 92.1 percent at pH 10. By going back to the pHzpc of the adsorbent, as shown in Fig. 4b, it is possible to examine the high removal of MxB dye at high pH. As known, the pHzpc influences the extent of zero charge on a solid surface in the lack of specific sorption, which is carried out using the powder addition method34. Alumina's pHzpc was found to be 7.5, while MxB, a cationic dye releases positive ions when dissolved in water. The surface of the adsorbent becomes negatively charged at pH > pHzpc, favoring the adsorption of cationic dye owing to an increase in the electrostatic force of attraction. As a result, cation adsorption on ɤ-alumina will be advantageous at this pH level. The opposite, however, occurs at low pH (< pHzpc); the positively charged adsorbent surface will repel the positively charged MxB cations to generate unoccupied adsorption sites, which reduces dye sorption. Hence, the ion diffusion acts as physical forces which impact on the behavior of the adsorbate molecules in the nearness area of the adsorbent ‘ɤ-alumina’ surface.

However, we can conclude that for the next experiments, the optimum pH and equilibrium time will be achieved at 10 and 20 min, respectively.

Maxilon Blue concentration

Figure 4c shows the relationship between the adsorption capacity of MxB dye on ɤ-Al2O3 at equilibrium time (room temperature = 293 K) and dye concentration varying between 10 and 100 ppm. It was found that the percentage of dye adsorbed rose when the dye concentration increased. This might be the result of unsaturated sites existing on the surface of ɤ-alumina. In order to check all of the MxB adsorption experiments below, it is preferable to achieve 100 ppm MxB concentration in the experiments that follow.

Adsorbent amount

The efficiency of the adsorption capacity of MxB on γ-Alumina was investigated at optimum conditions by changing the adsorbent dose (0.03–0.1 g), and the results are offered in Fig. 4d. According to this figure, the value of adsorption capacity increased until the adsorbent dose reached 0.05 g. But augmentation of the adsorbent dose led to decreasing the dye adsorption capacity and this result may be associated with an agglomeration and crowding of a greater amount of adsorbents, which block the pores and of course the adsorption process will decrease.

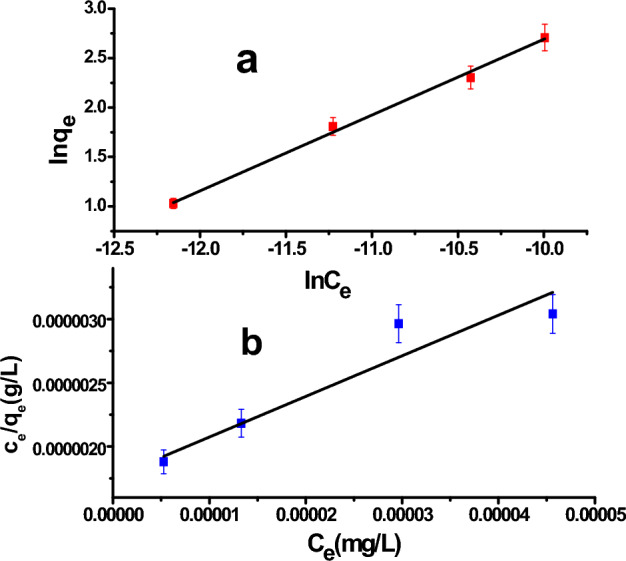

Experimental adsorption isotherm study

The retention or release of a material from the aqueous phase to the solid phase at a constant temperature is shown by the adsorption isotherm, as is well know. Understanding the properties of the adsorption surface as well as the mechanism of interaction between the adsorbate and the adsorbent surface is crucial35. In the present work, two isotherm models were studied, namely the Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm models, to obtain the best of equilibrium curves36. The mathematical equations of the selected isotherm models and their parameter description37–40 are listed in Table 4; four calculated model constants and six statistical parameters obtained from the two selected isotherm models are also summarized in Table 4, and the experimental results are shown in Fig. 5a and b.

Table 4.

Estimated isotherm models and statistical parameters for MxB dye adsorption on ɤ-Al2O3.

| Models | Langmuir* |

Freundlich* |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Qm (mg/g) | Kl (L/mg) | Kf (mg/g) | 1/n |

| 31.37 | 18.16 × 103 | 31.79 × 103 | 0.76 | |

| Adj-R2 | 0.89 | 0.99 | ||

| F-value | 26.17 | 604.39 | ||

| Sum of squares | 60.31 | 222.29 | ||

| Mean squares | 60.30 | 222.29 | ||

| Prob > f | 0.036 | 0.002 | ||

| DF | 2 | 2 | ||

Figure 5.

(a) Freundlich isotherm model, and (b) Langmuir isotherm model of MxB dye adsorption on ɤ-Al2O3 at room temperature.

As is common knowledge, the Langmuir isotherm postulates that once an adsorbate has occupied a spot, no more adsorption occurs there, creating a discriminating plateau in the curve, and there is no side commerce or steric interference between molecules that have been adsorbed38,41. On the other hand, the Freundlich isotherm could be considered an empirical model in which there is an interaction between adsorbed molecules (multilayer adsorption) on heterogeneous surfaces with a uniform energy distribution40,42. Also, this model proved that the (adsorbate) dye concentration on the adsorbent surface will be increased if there is a growing of adsorbate concentration in the solution without attaining saturation43. According to the obtained results in Table 4, adj. R2 values revealed a strong linear connection (0.995 close to 1) between the Freundlich model predicted and the experimental values, which is over and above assured by lower values of other statistical parameters such as the probability factor. But the reverse was got by carrying out the Langmuir model. Hence, these results reflected that the experimental values of MxB dye adsorption have a stronger correlation with the Freundlich isotherm than Langmuir model. Further, adsorption is a favorable physical process because of the appearance of 1/n parameter in the range of 0–136,44. As well, the qm value was calculated by applying the Langmuir equation, and it was equal to 31.37 mg/g.

Where: *20,45,46, qe (mg/g): equilibrium adsorption capacity, qm (mg/g): maximum adsorption capacity, Kl (L/mg): Langmuir constant, Ce (mg/L): equilibrium adsorbate concentration in solution, KF (mg/g): Freundlich constant, n: Heterogeneity factor.

Adsorption kinetic study of single Maxilon Blue dye

It is necessary to understand the kinetics and mechanism of adsorption in order to establish a good water treatment system. As liquid solution is adsorbed onto the solid adsorbent surfaces in many phases, the slowest step actually controls the entire process. Simulations of the linear form of the pseudo-first order (PFO) were carried out using data from the adsorption kinetic studies for different dye concentration solutions, pseudo-second order (PSO), and Elovich models to look into the sorption process of MxB dye onto ɤ-alumina adsorbent. Their equation forms are listed below Table 5.

Table 5.

Kinetic and statistical parameters of MxB dye adsorption onto ɤ-Al2O3 at different dye concentrations (10–100 mg/L).

| Kinetic model | Parameters | Sum of squares | Mean square | F-value | DF | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K1 (min−1) | qe (mg/g) | Adj-R2 | |||||||

| PFO* | |||||||||

| 10 | 0.001 | 0.94 | 0.69 | 4.38 | 4.38 | 27.64 | 11 | 2.70 × 10–4 | |

| 25 | 0.026 | 2.48 | 0.90 | 18.50 | 18.50 | 97.88 | 10 | 1.75 × 10–6 | |

| 50 | 0.030 | 1.03 | 0.96 | 40.68 | 40.68 | 281.98 | 11 | 3.46 × 10–9 | |

| 75 | 0.029 | 2.91 | 0.78 | 36.17 | 36.17 | 44.16 | 11 | 3.63 × 10–5 | |

| 100 | 0.025 | 8.55 | 0.93 | 26.54 | 26.54 | 155.84 | 11 | 7.74 × 10–8 | |

| Kinetic model | Parameters | Sum of squares | Mean square | F-value | DF | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| qe(exp.) (mg/g) | K2 (Conc−1 min−1) | qe (mg/g) | Adj-R2 | ||||||

| PSO** | |||||||||

| 10 | 2.8 | 0.1 | 2.57 | 0.99 | 6679.77 | 6679.77 | 1333.26 | 11 | 7.83 × 10–13 |

| 25 | 6.1 | 0.03 | 6.24 | 0.99 | 704.17 | 704.17 | 1511.98 | 10 | 3.02 × 10–12 |

| 50 | 10 | 0.13 | 10.03 | 0.99 | 439.38 | 439.38 | 1.78 × 105 | 11 | 0 |

| 75 | 15 | 0.04 | 14.91 | 0.99 | 198.54 | 198.54 | 1.12 × 104 | 11 | 0 |

| 100 | 31.7 | 0.01 | 31.76 | 0.99 | 43.78 | 43.78 | 1.88 × 104 | 11 | 0 |

| Kinetic model | Parameters | Sum of squares | Mean square | F-value | DF | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α (mg/g min) | β (g/mg) | Adj-R2 | |||||||

| Elovich*** | |||||||||

| 10 | 8.65 | 3.12 | 0.61 | 3.35 | 3.35 | 19.61 | 11 | 0.001 | |

| 25 | 5.18 | 1.08 | 0.79 | 24.31 | 24.31 | 43.09 | 10 | 6.35 × 10–5 | |

| 50 | 176.29 | 0.93 | 0.39 | 37.91 | 37.91 | 8.54 | 11 | 0.0139 | |

| 75 | 166.90 | 0.60 | 0.44 | 89.51 | 89.51 | 10.40 | 11 | 0.008 | |

| 100 | 113.06 | 0.25 | 0.61 | 524.34 | 524.34 | 19.54 | 11 | 0.001 | |

*ln (qe − qt) = ln(qe) – k1t34,44, ** 44,45,48,*** qt = ln (α β) + ln t33, where, qt is the amount of dye adsorbed at time t (mg/g), k1 is the first order rate constant (min−1), k2 is the pseudo-second order rate constant (conc. min)−1, α (mg/g min) is the initial sorption rate, and the parameter β (g/mg) is related to the extent of surface coverage.

As in Fig. 6a–e, the linearity plots of ln (qe–qt) versus time “t” for the pseudo-first order (PFO) model were obtained. The kinetic parameter values of k1, qe, the adj. correlation coefficient (R2) values, and the statistical parameters of fitting the (PFO) for MxB dye adsorption are listed in Table 5. From Table 5, it is clear that the lower value of adj. R2 and the higher value of statistical parameters indicated that the adsorption process did not obey the (PFO) model. On the other side, the parameters of linear forms of (PSO) equations emphasized that the rate-limiting step resulted from the chemical interaction between the solute and the adsorption sites at the adsorbent surface. To understand the achievement of this model, linear plots of t/qt versus time “t” for different concentrations were shown in Fig. 7a–e. The k2, qe, adj-R2, and statistical parameters were calculated from the plots and recorded in Table 5. As shown in this table, the theoretical adsorption capacity qe determined from the (PSO) model is nearby to the practical adsorption capacity qexp. Furthermore, the adj. R2 is also greater than 0.99 (∼ 1), and statistical parameters have the lowest value (prob. value = 0). We can definitely say that the pseudo-second-order model could well describe the system.

Figure 6.

Linear form of PFO of MxB dye adsorption on ɤ-Al2O3 at room temperature for different dye concentrations (10, 25, 50, 75, and 100 mg/L) (a–e), respectively.

Figure 7.

Linear form of PSO of adsorption of MxB dye on ɤ-Al2O3 at room temperature for different concentrations (10, 25, 50, 75, and 100 mg/L) for (a–e), respectively.

Elovich kinetic model in linear form showed that a linear relationship was obtained between qt and ln t over the whole adsorption period as shown in supplementary data (see Fig. S1a–e) and Elovich parameters were recorded in Table 5. These parameters are associated with the activation energy for the chemisorption process and are helpful in describing the adsorption on highly heterogeneous adsorbents as alumina, which possesses heterogeneous surface-active sites47.

Adsorption of mixture of MxB and MG dyes

For the mixture of two cationic dyes MG and MxB which were studied at the conditions mentioned earlier, the UV–vis spectra of the different mixtures (MxB: MG) Fig. 8a–c reflected that a new λmax = 612 nm appeared that is not far away from the λmax of two single dyes (609 nm for MxB and 617 nm for MG) but in between, which emphasized the equivalent selectivity toward the removal of two dyes in the binary system at equilibrium time as shown in Fig. 8d without forming an intermediate. So far, the removal efficiency of the mixture of MxB and MG significantly did not change with increasing the percent of each of them. Only a very small increase in the R% didn't exceed 1.8% for 2 MG: 1 MxB. This behavior not only revealed the greater affinity for both dyes but also proved the absence of selectivity of the adsorbent toward adsorbing these dyes in the bi-adsorbate system. This might be attributed to the similarity in their cationic nature. Further, the removal percentage of various mixed dyes at the same conditions was close to R% for sole MxB and MG (~ 93.6, 98.3%, respectively). From these obtained results, it is clear that the prepared adsorbent gave very high decolorization efficiency for a mixture of cationic dyes, showing its qualification for water treatment, especially in binary systems.

Figure 8.

(a–c) UV–visible Absorbance of a mixture of MG and MxB with different ratio, and (d) the removal % of these mixtures of dyes with different percentages (pH 7, room temp., 0.1 g dose of ɤ-Al2O3 and dye conc. = 50 mg/L).

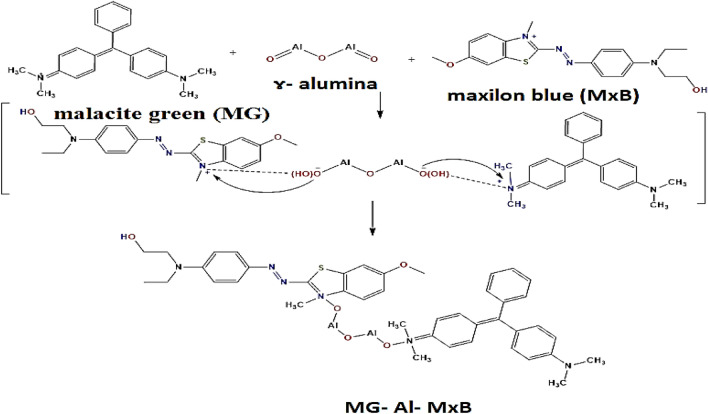

Interaction mechanism of MxB and/or MG mixture dyes with Al2O3 adsorbent

To the best of our knowledge, the surface behavior of ɤ-alumina, the structure of the dye molecule, and the interaction of the dye with the adsorbent are responsible for the mechanism of the process. The mechanism of dye adsorption through the electrostatic interaction was expected to be the main energetic force, which had been confirmed by previous research48,49.

In discussion of the interaction mechanism of MxB and/or MG mixture dyes with Al2O3, initially, the theoretical results obtained by DFT calculations can be concluded in the following:

The sole or binary dye adsorption mechanism occurred through electrostatic interaction because of the creation of an electrostatic interaction between the (N+) ion of MxB or MG and (O−2) on the alumina surface. So, this interaction occurred between two MxB and/or MG dye molecules and one alumina molecule.

The optimized bond length N–O between dye and oxide adsorbent is larger than the literature, which supports the physisorption process for the adsorption of single or binary cationic dye systems.

The similarity of many theoretical reactivity descriptor parameters for MxB and MG proved that there was no preferable dye in the mixed binary system for adsorbing over alumina.

The negative adsorption energy data of those sole and mixed dye molecules onto Al2O3 are arranged as follows: (Al2O3-MxB) < (MG-Al2O3) < (MG-Al2O3-MxB), which referred that the MxB dye is the less stable dye to be adsorbed.

According to the previous outcome, energetically, the adsorbed binary system is more favorable than the adsorbed sole dye.

On the other side the experimental results revealed the following:

The low-cost alumina adsorbent can be used as a highly efficient adsorbent for cationic dyes from an aqueous solution due to its advantages of small nanometer scale, high SBET, high porosity, and good dispersion.

The MxB cationic dye releases positive ions when dissolved in water, while the adsorbent surface becomes negatively charged at high pH (> pHzpc), favoring the occurrence of electrostatic interactions between the positively charged nitrogen and the negative oxygen center (Scheme 1).

The behavior of the dye molecules in the vicinity of the adsorbent "ɤ-alumina" surface is affected by the physical force of ion diffusion.

The experimental data of MxB dye adsorption represented a stronger correlation with the Freundlich isotherm, so, the physical mechanism of adsorption is a favorable process.

Kinetically, the pseudo-second-order model could well describe the system.

Further, the adsorption abilities toward the binary system (MxB and MG) were favorable owing to electrostatic attractive forces between the more positively active centers in two cationic dyes and the more negatively charged centers in the alumina surface with the physisorption process (Scheme 2).

The adsorbent's lack of selectivity in the bi-adsorbate system for adsorbing MG and MxB dyes.

Scheme 1.

Schematic illustration of the interaction mechanism of the sole dye adsorption process onto Al2O3 adsorbent.

Scheme 2.

Schematic illustration of the interaction mechanism of the binary dye adsorption process onto Al2O3 adsorbent.

From the previous integrated results, it is clear the good agreement between the experimental and theoretical outcomes.

In order to extra analyze the adsorption mechanism of dyes onto alumina, the FTIR spectra of alumina are shown in Fig. 9a. In comparison with adsorbent before and after adsorbing different dyes, certain changes were detected in the FTIR spectra, at which the peak at 1450 cm−1 was attributed to the non-bridging of O–H transformed into 1438 cm−1 in Al2O3-MxB and MG-Al2O3-MxB. In addition to the appearance of the bands at 870 and 531 cm−1 which are assigned to some interaction among Al (III) and oxygen or hydroxide bridge50. Based on the above-mentioned changes in FTIR spectra, it can be deduced that the adsorption mechanism of single MxB or its doublet with MG dye adsorption may occur through hydrogen bonding between the hydrogen of –OH groups on the surface of alumina and the nitrogen in the dye molecules for adsorbing MxB / MG (Schemes 1–2). Further, from the arrangements of MG and MxB over Al2O3 in the binary system (Fig. 2a,b), we noticed that the dimethyl amino group in MG revealed a tilt in the aromatic ring; however, for MxB, the entire aromatic ring is aligned over the adsorbent. So, the adsorption process can be expected to occur through the dispersion interaction, firstly for MxB over alumina with the physisorption process.

Figure 9.

(a) FT-IR spectrum of (a) adsorbent before dye adsorption, (b) after MxB dye adsorption, and (c) after MxB and MG mixture dye adsorption. (b) Comparison the removal efficiency % for sole and mixture of cationic dyes with different percentages (pH 7, room temp., at equilibrium time, 0.1 g dose of Al2O3 and dye conc. = 50 mg/L).

Figure 9b showed that at the end of the adsorption process, a comparison of the decolorization efficiency onto alumina adsorbent for different single and double cationic dyes at equilibrium time was the lowest for MxB over Al2O3, and this result may be due to its low stability as shown previously from the adsorption energy values (Table 3).

Thermodynamic behavior of the adsorbent solid toward MG adsorption was experimentally studied in our previous work24, which indicated that the adsorption process for cationic dye is spontaneous, endothermic in nature and increase the entropy occurred reflecting an increase in the randomness near the solid/solution interface. Logically, the adsorption behavior of MxB dye thermodynamically will be the same as the MG dye adsorption.

Finally, the last information can be summarized: the dye adsorption mechanism occurred through electrostatic interaction and/or hydrogen bonding through the physisorption process. The binary adsorption system exhibited the higher stability of the complex (MG-Al2O3-MxB) on alumina than other complexes.

Regeneration studies

A critical factor in determining commercial viability is the efficiency of an adsorbent to be reused. In this section, the used adsorbent was washed several times with distilled water, vacuum-dried at 110 °C, and then utilized again in subsequent cycles for adsorption. Generally, the % R over Al-2 adsorbent for 4 cycles of MxB dye adsorption was investigated as in Fig. S2 "see supplementary data". The obtained results revealed that the % R over the regenerated adsorbent was slightly decreased at the fourth cycle, but it could still represent around 70%. The stability of the Al-2 adsorbent after reusing it for the MxB adsorption process has been investigated by XRD, as shown in supplementary data (see Fig. S3). According to the XRD study, the Al-2 after regeneration did not significantly alter peak locations or powder size. This result indicated that the prepared adsorbent has significant stability even after severally uses and certain adsorbent mass may be consumed with repeated use. Further, the prepared adsorbent efficiency toward cationic dyes was the highest compared with other previously studied adsorbent results, as shown in Table 622,24,48,51–60. Finally, we can conclude that the nano-adsorbent demonstrated excellent stability in both theoretical and experimental results compared with previous studies61–66.

Table 6.

Comparison of cationic dyes removal efficiency using different materials via adsorption.

| No. | Adsorbent | Cationic dye | Adsorption condition | Efficiency (%) | Ref. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dye conc | Adsorbent dose, mg | Time, min | Temp., °C | |||||

| 1 | CNC | MB | – | 100 | 180 | RT | 78 | 54 |

| 2 | MCMFCs | 20 ppm | 10 | 150 | – | 92 | 55 | |

| 3 | CMC/GOCOOH | 20 ppm | 50 | 300 | RT | 95 | 56 | |

| 4 | HPAM/CNC | 5 ppm | 2 | 240 | – | 90 | 57 | |

| 5 | CMC coated Fe3O4@SiO2 MNPs | 50 ppm | 50 | 720 | – | 85 | 58 | |

| 6 | CoFe2O4/H6 300 °C | 100 ppm | 100 | 120 | RT | 40 | 48 | |

| 7 | CoFe2O4/H8 300 °C | 100 ppm | 100 | 120 | RT | 50 | 48 | |

| 8 | Chitosan beads | MG | 40ppm | 25 | 300 | – | 88 | 59 |

| 9 | ZIF-8 | 50 ppm | 62 | 240 | – | 80 | 51 | |

| 10 | MgO nano-rod | 50 ppm | 10 | 1500 | – | 92 | 52 | |

| 11 | Al-2 | 50 ppm | 100 | 20 | 25 | 98.8 | 24 | |

| 12 | Sepiolite | MxB | 2.5 × 10−3 M | 5 × 103 | 180 | 25 | 85 | 60 |

| 13 | Al-2 | 100 ppm | 50 | 20 | 20 | 99 | Present study | |

| 14 | Nano-alumina | Rhodamine blue | 10–6 M | 30 | 180 | – | 80 | 22 |

| 15 | Activated carbon from apple leaves "AC1" | Basic dye C.I. base blue 47 | 60 ppm | 100 | 150 | 25 | 50.4 | 53 |

Conclusion

An innovative study for the adsorption of single (MxB) and its mixture with (MG) cationic dye from aqueous solution in different ratios was carried out on γ-alumina experimentally and simulated theoretically by DFT theory. Theoretically, the full geometry optimization of MxB and its mixture with MG dyes with a ratio of 1:1 was performed to investigate the structure geometry and energetics by applying the B3LYP/6-31G (d, p) level of theory. There was a good agreement between the theoretical and the experimental results, as the following: (i) the optimized bond length N–O between N-atom of the dye and the (O) atom of Al-oxide was higher than the literature. This result confirmed the physical adsorption process in the sole or binary systems. (ii) Studying the non-linear optical properties of the formed complexes after adsorption showed that the complex MG-Al2O3-MxB is promising as an NLO material and can be used in photo- applications. (iii) Also, a comparison of the removal efficiency for the single and the mixture of cationic dyes was performed experimentally and theoretically. The outcomes referred that the adsorption of the mixture of binary dyes on alumina is more preferable than the single system due to its high stability. But, the similarity of some theoretical reactivity descriptor values for MxB and MG, and their experimental adsorption results reflected that there was no better dye in the mixed binary system for adsorbing on alumina. (iv) Further, the interaction mechanism for MxB and/or MG was proved and may be due to the electrostatic interaction between the cationic groups (–N+) of MxB and/or MG (equal ratio) and the negatively charged groups (–Al–O−) on the alumina surface or through hydrogen bonding.

Some experimental items were studied on the adsorption of sole dye onto nanoadsorbent for optimization. It was revealed that the MxB removal reached to 99% at ideal conditions (pH 10, dye concentration = 100 mg/L, adsorbent dose = 50 mg, and equilibrium time = 20 min). The adsorption of MxB was found to obey pseudo- second order model and Freundlich isotherm for adsorption the kinetics and isotherms, respectively. The nano-adsorbent demonstrated excellent stability and reusability across four cycles.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The Researchers would like to thank the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Qassim University for financial support (QU-APC-2024-9/1).

Author contributions

Shaimaa M. Ibrahim, Sahar. A. El-Molla, EL-Shimaa Ibrahim: Conceived, designed, and performed the experiments; Analyzed and calculated the experimental and theoretical data, Wrote, and revised the paper. Also, Nouf F. Al-Harby revised the paper, paid the publication fees and shared in the publication procedures.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Shaimaa M. Ibrahim, Email: shimaaabdelaal@edu.asu.edu.eg

Nouf F. Al-Harby, Email: hrbien@qu.edu.sa

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-65649-2.

References

- 1.Vieiraa AP, Santanaa SAA, Bezerraa CWB, Silvaa HAS, Júlio JAPC, da Silva Filhod EC. Kinetics and thermodynamics of textile dye adsorption from aqueous solutions. J. Hazard. Mater. J. 2009;166:1272–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKay G, Otterburn MS, Aga JA. Fuller’s earth and fired clay as adsorbents for dyestuffs: Equilibrium and rate studies. Water Air Soil Pollut. 1985;24:307–322. doi: 10.1007/BF00161790. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janoš P, Buchtová H, Rýznarová M. Sorption of dyes from aqueous solutions onto fly ash. Water Res. 2003;37:4938–4944. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2003.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dogan M, Alkan M, Demirbas O. Adsorption kinetics of maxilon blue GRL onto sepiolite. Chem. Eng. J. 2006;124:89–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2006.08.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang G, Okajima I, Sako T. Decomposition and decoloration of dyeing wastewater by hydrothermal oxidation. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 2016;112:136–142. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2015.10.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gomathi Devi L, Girish Kumar S, Mohan Reddy K, Munikrishnappa C. Photo degradation of methyl orange an azo dye by advanced fenton process using zero valent metallic iron: Influence of various reaction parameters and its degradation mechanism. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009;164:459–467. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Erdemoğlu S, Aksu SK, Sayılkan F, İzgi B, Asiltürk M, Sayılkan H, Frimmel F, Güçer Ş. Photocatalytic degradation of Congo Red by hydrothermally synthesized. J. Hazardous Mater. 2008;155(3):469–476. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.11.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Emgili H, Yabalak E, Görmez Ö. Degradation of maxilon blue GRL dye using subcritical water and ultrasonic assisted oxidation. J. Sci. 2017;30:140–150. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chowdhury S, Mishra R, Saha P, Kushwaha P. Adsorption thermodynamics, kinetics and isosteric heat of adsorption of malachite green onto chemically modified rice husk. Desalination. 2011;265:159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.desal.2010.07.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vidya C, Manjunatha C, Chandraprabha MN, Megha Rajshekar ARMA. Hazard free green synthesis of ZnO nano-photo-catalyst.pdf. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017;5:3172–3180. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang X, et al. Adsorption of azo dyes and Naproxen by few-layer MXene immobilized with dialdehyde starch nanoparticles: Adsorption properties and statistical physics modeling. Chem. Eng. J. 2023;473:145385. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2023.145385. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diao Z, et al. Adsorption of food dyes from aqueous solution on a sweet potato residue-derived carbonaceous adsorbent: Analytical interpretation of adsorption mechanisms via adsorbent characterization and statistical physics modeling. Chem. Eng. J. 2024;482:148982. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2024.148982. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang WZ, An H. UV/TiO2 photocatalytic oxidation of commercial dyes in aqueous solutions. Chemosphere. 1995;31:4157–4170. doi: 10.1016/0045-6535(95)80015-D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janitabar-Darzi S. Structural and photocatalytic activity of mesoporous doped TiO2 with band-to-band visible light absorption. Nucl. Sci. Technol. Res. Inst. 2014;32:506–511. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aljeboree AM, Alkaim AF, Al-Dujaili AH. Adsorption isotherm, kinetic modeling and thermodynamics of crystal violet dye on coconut husk-based activated carbon. Desalin. Water Treatm. 2015;53:3656–3667. doi: 10.1080/19443994.2013.877854. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fil BA. Isotherm, kinetic and thermodynamic studies on the adsorption behavior of malachite green dye onto montmorillonite clay. Part. Sci. Technol. 2015;34:118–126. doi: 10.1080/02726351.2015.1052122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alrobayi EM, Algubili AM, Aljeboree AM. Investigation of photocatalytic removal and photonic efficiency of maxilon blue dye GRL in the presence of TiO2 nanoparticles. Part. Sci. Technol. 2017;35:14–20. doi: 10.1080/02726351.2015.1120836. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janoš P, Šmídová V. Effects of surfactants on the adsorptive removal of basic dyes from water using an organomineral sorbent-iron humate. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2005;291:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2005.04.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahmoud HR, Ibrahim SM, El-Molla SA. Textile dye removal from aqueous solutions using cheap MgO nanomaterials: Adsorption kinetics, isotherm studies and thermodynamics. Adv. Powder Technol. 2016;27:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.apt.2015.12.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ibrahim SM, Naghmash MA, El-Molla SA. Synthesis and application of nano-hematite on the removal of carcinogenic textile remazol red dye from aqueous solution. Desalin. Water Treat. 2020;180:370–386. doi: 10.5004/dwt.2020.25063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kasprzyk-Hordern B. Chemistry of alumina, reactions in aqueous solution and its application in water treatment. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2004;110:19–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chu TPM, et al. Synthesis, characterization, and modification of alumina nanoparticles for cationic dye removal. Materials. 2019;12:450. doi: 10.3390/ma12030450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giraldo S, Robles I, Godínez LA, Acelas N, Flórez E. Experimental and theoretical insights on methylene blue removal from wastewater using an adsorbent obtained from the residues of the orange industry. Molecules. 2021;26:4555. doi: 10.3390/molecules26154555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ibrahim ES, Moustafa H, El-Molla SA, Halim SA, Ibrahim SM. Integrated experimental and theoretical insights for Malachite Green Dye adsorption from wastewater using low cost adsorbent. Water Sci. Technol. 2021;84:3833–3858. doi: 10.2166/wst.2021.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Natorajan S, Shanmugam GMS. Growth and characterization of a new semi organic NLO material: L-tyrosine hydrochloride. Cryst. Res. Technol. 2008;43:561–564. doi: 10.1002/crat.200711048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chemia ZJ. Nonlinear Optical Properties of Organic Molecules and Crystals. Acad. Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng LT, Tam W, Stevenson SH, Meredith GR, Rikken G. Experimental investigations of organic molecular nonlinear optical polarizabilities. 1. Methods and results on benzene and stilbene derivatives. J. Phys. Chem. 1991;95:10631–10643. doi: 10.1021/j100179a026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaatz P, Donley EA. A comparison of molecular hyperpolarizabilities from gas and liquid phase measurements. J. Chem. Phys. 1998;108:849. doi: 10.1063/1.475448. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Champagne B, Plaquet A, Pozzo J, Rodriguez V. Nonlinear optical molecular switches as selective cation sensors. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134(19):8101–8103. doi: 10.1021/ja302395f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abdel-Haleem FM, et al. Carbon-based nanosensors for salicylate determination in pharmaceutical preparations. Electroanalysis. 2019;31:778–789. doi: 10.1002/elan.201800728. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sethuvasan S, Sugumar P, Ponnuswamy MN, Ponnuswamy S. Synthesis, spectral characterization, solution and solid-state conformations of N-nitroso-2,7-diaryl-1,4-diazepan-5-ones by NMR and XRD studies. J. Mol. Struct. 2021;1223:129002. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.129002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Regti A, et al. Experimental and theoretical study using DFT method for the competitive adsorption of two cationic dyes from wastewaters. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016;390:311–319. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2016.08.059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Molla A, et al. Selective adsorption of organic dyes on graphene oxide: Theoretical and experimental analysis. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019;464:170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.09.056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ibrahim SM, Hassanin HM, Abdelrazek MM. Synthesis, and characterization of chitosan bearing pyranoquinolinone moiety for textile dye adsorption from wastewater. Water Sci. Technol. 2020;81:421–435. doi: 10.2166/wst.2020.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Limousin G, et al. Sorption isotherms: A review on physical bases, modeling and measurement. Appl. Geochem. 2007;22:249–275. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeochem.2006.09.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murthy TPK, Gowrishankar BS, Chandra Prabha MN, Kruthi M. Studies on batch adsorptive removal of malachite green from synthetic. Microchem. J. 2019;146:192–201. doi: 10.1016/j.microc.2018.12.067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ergene A, Ada K, Tan S, Katircioǧlu H. Removal of Remazol Brilliant Blue R dye from aqueous solutions by adsorption onto immobilized Scenedesmus quadricauda: Equilibrium and kinetic modeling studies. Desalination. 2009;249:1308–1314. doi: 10.1016/j.desal.2009.06.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Langmiur L. The Constitution and fundamental properties of solids and liquids. Part I. Solids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1916;38:2221–2295. doi: 10.1021/ja02268a002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Akar ST, Özcan AS, Akar T, Özcan A, Kaynak Z. Biosorption of a reactive textile dye from aqueous solutions utilizing an agro-waste. Desalination. 2009;249:757–761. doi: 10.1016/j.desal.2008.09.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Freundlich HMF. Over the adsorption in solution. J. Phys. Chem. 1906;57:385–471. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Foo KY, Hameed BH. Insights into the modeling of adsorption isotherm systems. Chem. Eng. J. 2010;156:2–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2009.09.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rangabhashiyam S, Anu N, Giri Nandagopal MS, Selvaraju N. Relevance of isotherm models in biosorption of pollutants by agricultural byproducts. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2014;2:398–414. doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2014.01.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gimbert F, Morin-Crini N, Renault F, Badot PM, Crini G. Adsorption isotherm models for dye removal by cationized starch-based material in a single component system: Error analysis. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008;157:34–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.12.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang X, et al. Adsorption of methylene blue and Congo red from aqueous solution on 3D MXene/carbon foam hybrid aerogels: A study by experimental and statistical physics modeling. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023;11:109206. doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2022.109206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bahareh Rabeie NMM. Heterogeneous MIL-88A on MIL-88B hybrid: A promising eco-friendly hybrid from green synthesis to dual application (Adsorption and photocatalysis) in tetracycline and dyes removal. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024;654:495–522. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2023.10.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aqdam SR, Otzen DE, Mahmoodi NM. Adsorption of azo dyes by a novel bio-nanocomposite based on whey protein nanofibrils and nano-clay: Equilibrium isotherm and kinetic modeling. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021;602:490–503. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2021.05.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bulut E, Özacar M, Şengil IA. Adsorption of malachite green onto bentonite: Equilibrium and kinetic studies and process design. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2008;115:234–246. doi: 10.1016/j.micromeso.2008.01.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ibrahim SM, Badawy AA, Essawy HA. Improvement of dyes removal from aqueous solution by Nanosized cobalt ferrite treated with humic acid during coprecipitation. J. Nanostruct. Chem. 2019;9:281–298. doi: 10.1007/s40097-019-00318-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Badawy AA, Ibrahim SM, Essawy HA. Enhancing the textile dye removal from aqueous solution using cobalt ferrite nanoparticles prepared in presence of fulvic acid. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2020;30:1798–1813. doi: 10.1007/s10904-019-01355-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ibrahim MM. An efficient nano-adsorbent via surfactants/dual surfactants assisted ultrasonic co-precipitation method for sono-removal of monoazo and diazo anionic dyes. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2020;40:225–236. doi: 10.1016/j.cjche.2020.08.049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Abdi J, Vossoughi M, Mohammad N. Synthesis of metal-organic framework hybrid nanocomposites based on GO and CNT with high adsorption capacity for dye removal. Chem. Eng. J. 2017;326:1145–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2017.06.054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ghoniem MG, et al. Highly selective removal of cationic dyes from wastewater by MgO nanorods. Nanomaterials. 2022;12:1–14. doi: 10.3390/nano12061023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Helmy M, Aziz A, Zakaria E, Ashtoukhy E, Bassyouni M. DFT and experimental study on adsorption of dyes on activated carbon prepared from apple leaves. Carbon Lett. 2021;31:863–878. doi: 10.1007/s42823-020-00187-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Georgouvelas D, et al. All-cellulose functional membranes for water treatment: Adsorption of metal ions and catalytic decolorization of dyes. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021;264:118044. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.118044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li Y, et al. Novel composite adsorbent consisting of dissolved cellulose fiber/microfibrillated cellulose for dye removal from aqueous solution. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018;6(5):6994–7002. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b00829. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Eltaweil AS, et al. Carboxymethyl cellulose/carboxylated graphene oxide composite microbeads for efficient adsorption of cationic methylene blue dye. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020;154:307–318. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.03.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhou C, et al. Adsorption kinetic and equilibrium studies for methylene blue dye by partially hydrolyzed polyacrylamide/cellulose nanocrystal nanocomposite hydrogels. Chem. Eng. J. 2014;251:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2014.04.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zirak M, et al. Carboxymethyl cellulose coated Fe3O4@ SiO2 core–shell magnetic nanoparticles for methylene blue removal: Equilibrium, kinetic, and thermodynamic studies. Cellulose. 2018;25(1):503–515. doi: 10.1007/s10570-017-1590-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bekçi Z, Özveri C, Seki Y, Yurdakoç K. Sorption of malachite green on chitosan bead. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008;154:254–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Doğan M, Alkan M, Demirbaş Ö, Özdemir Y, Özmetin C. Adsorption kinetics of maxilon blue GRL onto sepiolite from aqueous adsorption kinetics of maxilon blue GRL onto sepiolite from aqueous solutions. Chem. Eng. J. 2006;124:89–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2006.08.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Iqbal MJ, Ashiq MN. Adsorption of dyes from aqueous solutions on activated charcoal. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007;139:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Allal H, et al. Structural, electronic, and energetic investigations of acrolein adsorption on B 36 borophene nanosheet: A dispersion-corrected DFT insight. J. Mol. Model. 2020;26(6):128. doi: 10.1007/s00894-020-04388-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bagheri A, Hoseinzadeh H, Hayati B, Mohammad N. Post-synthetic functionalization of the metal-organic framework: Clean synthesis, pollutant removal, and antibacterial activity. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021;9:104590. doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2020.104590. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jery AE, et al. Isotherms, kinetics and thermodynamic mechanism of methylene blue dye adsorption on synthesized activated carbon. Sci. Rep. 2024;14:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-50937-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Adam FA, Ghoniem MG, Diawara M, Rahali S. Enhanced adsorptive removal of indigo carmine dye by bismuth oxide doped MgO based adsorbents from aqueous solution: Equilibrium, kinetic and. RSC Adv. 2022;12:24786–24803. doi: 10.1039/D2RA02636H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Abolhassan S, Vossoughi M, Mohammad N. Clay-based electrospun nano fi brous membranes for colored wastewater treatment. Appl. Clay Sci. 2019;168:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.clay.2018.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.