Abstract

Alternative splicing is a critical component of the early to late switch in papillomavirus gene expression. In bovine papillomavirus type 1 (BPV-1), a switch in 3′ splice site utilization from an early 3′ splice site at nucleotide (nt) 3225 to a late-specific 3′ splice site at nt 3605 is essential for expression of the major capsid (L1) mRNA. Three viral splicing elements have recently been identified between the two alternative 3′ splice sites and have been shown to play an important role in this regulation. A bipartite element lies approximately 30 nt downstream of the nt 3225 3′ splice site and consists of an exonic splicing enhancer (ESE), SE1, followed immediately by a pyrimidine-rich exonic splicing suppressor (ESS). A second ESE (SE2) is located approximately 125 nt downstream of the ESS. We have previously demonstrated that the ESS inhibits use of the suboptimal nt 3225 3′ splice site in vitro through binding of cellular splicing factors. However, these in vitro studies did not address the role of the ESS in the regulation of alternative splicing. In the present study, we have analyzed the role of the ESS in the alternative splicing of a BPV-1 late pre-mRNA in vivo. Mutation or deletion of just the ESS did not significantly change the normal splicing pattern where the nt 3225 3′ splice site is already used predominantly. However, a pre-mRNA containing mutations in SE2 is spliced predominantly using the nt 3605 3′ splice site. In this context, mutation of the ESS restored preferential use of the nt 3225 3′ splice site, indicating that the ESS also functions as a splicing suppressor in vivo. Moreover, optimization of the suboptimal nt 3225 3′ splice site counteracted the in vivo function of the ESS and led to preferential selection of the nt 3225 3′ splice site even in pre-mRNAs with SE2 mutations. In vitro splicing assays also showed that the ESS is unable to suppress splicing of a pre-mRNA with an optimized nt 3225 3′ splice site. These data confirm that the function of the ESS requires a suboptimal upstream 3′ splice site. A surprising finding of our study is the observation that SE1 can stimulate both the first and the second steps of splicing.

Removal of introns from primary transcripts (pre-mRNAs) by RNA splicing is an essential step in maturation of most eukaryotic mRNAs. The initial machinery of pre-mRNA splicing involves recognition of a 5′ splice site by U1 snRNP and a 3′ splice site by U2 auxiliary factor (U2AF) and then U2 snRNP. The conventional 3′ splice site consists of three critical elements: the branch point sequence (BPS), a polypyrimidine tract (PPT), and an AG dinucleotide at the 3′ end of the intron. Although the yeast BPS (UACUAAC) is highly conserved and optimized for base pairing with a conserved region (GUAGUA) of U2 snRNA (26), the mammalian consensus BPS (YNYURAY) is fairly degenerate and yet does base pairing with U2 snRNA (3, 45, 54). However, many higher eukaryotic cellular and viral transcripts have a nonconsensus (suboptimal or weak) BPS. The PPT is a run of 15 to 40 pyrimidines (usually U's) that lies between the BPS and the AG dinucleotide (15, 30, 48). The PPT has binding sites for U2AF, a heterodimer of U2AF65 and U2AF35 (17, 27, 35, 46). Any purines that are interspersed in the PPT will weaken the binding of U2AF and make the PPT suboptimal (30, 31, 36, 47). It has been shown previously that a strong PPT can offset the effect of a nonconsensus BPS or vice versa and make the pre-mRNA be spliced more efficiently (3, 11, 22, 24, 34, 37, 38). Downstream of the PPT is an AG dinucleotide. The nature of the nucleotide preceding the AG has a profound effect on splicing. It has been reported previously that GAG (but not CAG, UAG, or AAG) trinucleotides at the 3′ splice junction inhibit the second step of splicing (30, 36). Statistical analysis of the nucleotide preceding the AG dinucleotide has shown that the yeast 3′ splice site has solely CAG (21), whereas mammalian 3′ splice sites have either CAG or UAG, but CAG is twice as common as UAG (48).

In general, suboptimal 3′ splice sites are often subject to both positive and negative regulation by a variety of cis splicing elements. Exonic splicing enhancers (ESEs) increase utilization of a suboptimal splice site by recruiting essential splicing factors to that site (39, 55). Exonic splicing suppressors (ESS) or silencers are recently described cis elements that inhibit splicing of pre-mRNAs. ESS elements share few sequence similarities. However, they are often found adjacent to an ESE and together form bipartite splicing elements. We have recently summarized most of the published ESS elements along with their functional core sequences (52). Studies of the mechanisms by which an ESS functions in vitro and in vivo have demonstrated that many cellular splicing factors are probably involved in splicing suppression by an ESS. These include SR proteins (53) for the bovine papillomavirus type 1 (BPV-1) ESS, SC35 for the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) tat exon 3 ESS (20), hnRNP H for the rat β-tropomyosin exon 7 ESS (6), and hnRNP A1 for the fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) 2 K-SAM ESS and for the HIV-1 tat exon 2 ESS (5, 9). Moreover, the fibronectin EDA ESS has been implicated in the maintenance of an RNA conformation that facilitates display of the adjacent ESE SR protein binding sequences (23).

The papillomaviruses are a family of small DNA tumor viruses which contain an 8-kb circular genome. Infection of humans and many animals causes epithelial and fibroepithelial lesions including benign warts or papillomas and invasive cancers. It has been well documented that the virus life cycle of all family members requires a differentiating squamous epithelium. BPV-1 has served as the prototype for studies of papillomavirus molecular biology for more than 2 decades. Regulation of BPV-1 gene expression at the posttranscriptional level involves both alternative splicing and alternative polyadenylation. The majority of the viral early transcripts are processed using a common 3′ splice site at nucleotide (nt) 3225 and the early poly(A) site at nt 4203 in the undifferentiated keratinocyte at early stages of virus infection. However, maturation of the viral late primary transcript to generate the major capsid (L1) mRNA requires utilization of an alternative 3′ splice site at nt 3605 and the late specific poly(A) site at nt 7175. Previous in situ hybridization studies in our laboratory demonstrated that the nt 3605 3′ splice site is utilized only in the fully differentiated keratinocytes during late stages of the virus life cycle (2). Further investigations into the molecular mechanisms that regulate BPV-1 alternative splicing lead us to identify three cis-acting elements between the nt 3225 3′ splice site and the nt 3605 3′ splice site. We demonstrated previously that two ESEs, SE1 and SE2, are essential for preferential utilization of the nt 3225 3′ splice site in vitro and in vivo and that this function is mediated through interaction with cellular SR protein splicing factors (50, 51). Another cis-acting element was designated an ESS because it suppresses use of the nt 3225 3′ splice site in vitro. The BPV-1 ESS is immediately downstream of SE1 and 125 nt upstream of SE2 (see Fig. 1A). The ESS is 48 nt long and can be divided into three regions based on sequence composition. Analysis of the proteins binding to the ESS has shown that the U-rich 5′ region of the ESS binds U2AF65 and PTB, the C-rich central part binds 35- and 55-kDa SR proteins, and the AG-rich 3′ end binds ASF/SF2 (53). The activity of the ESS maps to the central C-rich core (GGCUCCCCC), which, along with additional nonspecific downstream nucleotides, is sufficient for partial suppression of splicing of BPV-1 late pre-mRNAs at or before assembly of spliceosome complex A. Moreover, the inhibition of in vitro splicing by the ESS can be partially relieved by excess purified HeLa SR proteins (53). We have also demonstrated using homologous and heterologous pre-mRNAs that the function of the ESS in vitro requires a suboptimal upstream 3′ splice site, but not an upstream ESE (52). Both the nt 3225 3′ splice site and nt 3605 3′ splice site have been shown to be functionally suboptimal and are characterized by nonconsensus BPSs and PPTs interspersed with purines. The weak nature of these sites allows them to be subject to regulation by ESEs and ESSs (50; Z.-M. Zheng et al., unpublished data).

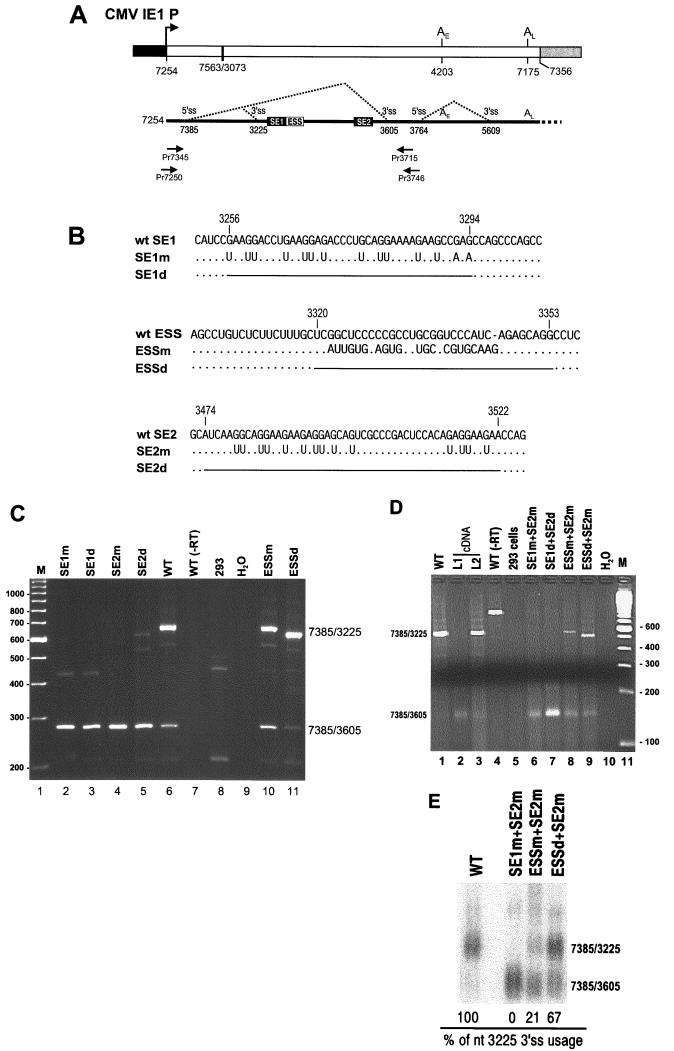

FIG. 1.

Double mutational analysis of both BPV-1 ESS and SE2 in vivo. (A) Diagrams of a BPV-1 late minigene expression vector (top) and the splicing pattern (bottom) of pre-mRNAs expressed from the vector. At the ends of the late minigene (open box) are the cytomegalovirus (CMV) IE1 promoter (solid box) and pUC18 (grey box). Numbers below the lines are the nucleotide positions in the BPV-1 genome. Early and late poly(A) sites are indicated as AE and AL, respectively, above the lines. A large deletion in the intron region of the genome is shown by a heavy vertical line. Below the minigene diagram is the structure of the minigene transcript. The relative positions of SE1, ESS, and SE2 are shown as well as the nucleotide positions of the 5′ splice site (5′ ss) and 3′ splice site (3′ ss). Two pairs of primers used for RT-PCR in panels C and D are indicated by arrows under the transcript and named by the location of their 5′ ends. (B) Nucleotide sequences of wt and mt SE1, ESS, and SE2 in the pre-mRNAs expressed from the following plasmids used for transfection of 293 cells: plasmids p3231 (wt), p3031 (SE1m), p3032 (SE1d), p3033 (SE2m), p3034 (SE2d), p3035 (ESSm), p3036 (ESSd), p3078 (SE1m + SE2m), p3079 (SE1d + SE2d), p3080 (ESSm + SE2m), and p3081 (ESSd + SE2m) (see Materials and Methods for construction of the plasmids with single or double mutations). Unchanged nucleotides (dots) and deletions (horizontal lines) are indicated. Deletion endpoints are labeled above each sequence and correspond to positions in the BPV-1 genome. (C and D) RT-PCR analysis of BPV-1 late mRNAs transcribed and spliced in 293 cells from the expression vectors with single (C) or double (D) mutations as labeled on the top of each gel. Total cell RNA was extracted and digested with RNase-free DNase I before RT-PCR analysis. Several controls were included for the assays including p3231 (wt)-transfected 293 cell RNAs, untransfected 293 cell RNAs, and water controls. Total cell RNAs extracted from p3231 (wt)-transfected 293 cells but not treated with RNase-free DNase I [WT (−RT)] and BPV-1 L1 cDNA and a 10:1 mixture of L2-L and L2-S cDNAs were also used as templates for PCR amplification in panel D. Predicted sizes of the RT-PCR products differ between panels due to the use of different sets of primers and are 658 bp (C) and 530 bp (D) for nt 3225 3′ splice site usage and 278 bp (C) and 150 bp (D) for nt 3605 3′ splice site usage. Numbers at left of panel C and right of panel D are molecular sizes in base pairs. (E) Northern blot analysis of the BPV-1 late mRNAs transcribed and spliced in 293 cells from the expression vectors with double mutations. Poly(A)-selected total cell RNA extracted from 293 cells transfected with plasmid p3078 (SE1m + SE2m), p3080 (ESSm + SE2m), and p3081 (ESSd + SE2m) was run on a 1% agarose–formaldehyde gel, blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane, and hybridized with 32P-labeled BPV-1 early probe. The ratio (percentage) of the nt 3225 3′ splice site usage was calculated based on the formula: % = nt 3225 3′ splice site/(nt 3225 + nt 3605 3′ splice site). One representative experiment of three for each panel, C, D, and E, is shown.

Our previous studies demonstrated that the BPV-1 ESS functions in vitro in several different pre-mRNAs, all of which contain only one 3′ splice site. These studies did not address the role of the ESS in the regulation of alternative splicing or its function in vivo, however. In this study, we have analyzed the function of the ESS in vivo in a BPV-1 late pre-mRNA with two alternative splice sites. We have found that the splicing suppressor activity of the ESS can be demonstrated in vivo using the late pre-mRNA in which SE2 has been mutated. This suggests that one role of SE2 is to counterbalance the effect of the ESS. Furthermore, optimization of the suboptimal nt 3225 3′ splice site counteracts the function of the ESS in vivo and in vitro and leads to selection of the nt 3225 3′ splice site even in the absence of SE2. Finally, we have demonstrated using BPV-1 late pre-mRNAs containing an optimized nt 3225 3′ splice site that a purine-rich ESE (SE1) stimulates not only the first step but also the second step of splicing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids and plasmid construction.

Construction of BPV-1 late minigene plasmids p3030 (pZMZ19-1), p3231 (pCCB458-2), and p3033 (SE2 mutation only) has been described in our previous publications (50, 51). To replace the BPV-1 BPS at the nt 3225 3′ splice site with the human β-globin BPS as well as to substitute pyrimidines for purines in the PPT, an overlap extension PCR (10, 16) was performed on plasmid p3030. Basically, two pairs of primers were used for PCR. Primer Pr3169 (oZMZ162; 5′-GTAAGAGATCAGGACAGAGTGT ATGCTGGTCACTGACCCTCCTCTTCTTTTTTCAGAGATCGCCCAGAC GGAGTCTGG-3′) was complementary to Pr3246 (oZMZ191; 5′-CCAGACTC CGTCTGGGCGATCTCTGAAAAAAGAAGAGGAGGGTCAGTGACCAG CATACACTCTGTCCTGATCTCTTAC-3′). Pr3169 and Pr3246 contain the BPS and PPT mutations mentioned above in the middle of the oligonucleotide sequence and were combined, respectively, with primers Pr3715 (oZMZ161; 5′-TTTCAGCACCGTTGTCAGCAACTGTG-3′) and Pr7276 (oFD127, a chimeric T7/BPV-1 primer; 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGA/GCGCCTGGCACCGAATCC-3′) for separate PCRs (see diagram in Fig. 2A). The two PCR products were then gel purified and annealed together through their overlapping sequences. Finally, the annealed PCR mix was reamplified by PCR by using the primer Pr7276 in combination with the primer Pr3715. The reamplified PCR products were digested with XhoI and Asp718. The XhoI and Asp718 fragment with a size of about 380 bp was cloned into the XhoI and Asp718 site of plasmid p3033 (51). The new plasmid, p3082 (pZMZ62-7), containing both human β-globin BPS and mutant PPT, was verified by sequencing and used for in vitro and in vivo splicing analysis.

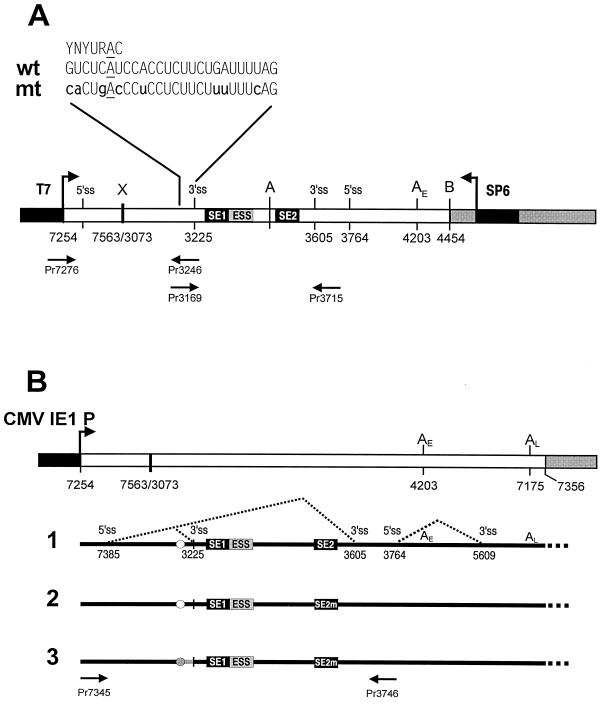

FIG. 2.

Strengthening the nt 3225 3′ splice site counteracts the function of the BPV-1 ESS in vivo. (A) Diagram of an overlap extension PCR strategy used to introduce human β-globin BPS and PPT mutations at the nt 3225 3′ splice site in a BPV-1 late minigene. The schematic diagram, as in Fig. 1A, is of a BPV-1 late minigene plasmid, p3030 (50). Promoters (black boxes) are T7 on the 5′ end and SP6 on the 3′ end of the vector. Grey boxes at the 3′ end are pUC18. Restriction sites XhoI (X), Asp718 (A), and BamHI (B); 3′ or 5′ splice sites; and the early poly(A) site (AE) are indicated on the top of the vector. Two pairs of primers (Pr7276 and Pr3246 as well as Pr3169 and Pr3715) were used for the overlap extension PCR (see Materials and Methods). The constructed plasmid p3082 has a pre-mRNA transcript containing both human β-globin BPS and mt PPT at the nt 3225 3′ splice site, which are shown on the top of the diagram with branch points underlined and substitutions lowercased (mt). Mammalian BPS consensus YNYURAC and wt BPV-1 BPS and PT are shown for comparison. (B) A BPV-1 late minigene expression vector (top) and the splicing patterns of pre-mRNAs expressed from the vector (below) are schematically diagrammed as in Fig. 1A. Structures of pre-mRNAs 1, 2, and 3 and the nucleotide sequences of SE1, ESS, and SE2 or SE2m are shown as in Fig. 1A and B. The wt BPV-1 BPS is shown in an open circle, and the human β-globin BPS is shown in a grey circle. The PPT region between BPS and the nt 3225 3′ splice site is diagrammed as a black line (wt) or a grey line (mt form). The nucleotide composition of the mt BPS and PPT in the pre-mRNA 3 is shown in panel A. The pre-mRNAs 1, 2, and 3 were transcribed, respectively, from plasmids p3231, p3033 (51), and p3082. Their splicing patterns were analyzed by RT-PCR using a 5′ sense primer, Pr7345 (oCCB48; 5′-CAATGGGACGCGTGCAAAGC-3′), combined with a 3′ antisense primer, Pr3746 (oCCB57; 5′-AAGGTGATCAGTATTTGTGC-3′), as shown below the pre-mRNA 3. (C) A representative agarose gel of the RT-PCRs from three separate transfections. Total cell RNA was extracted from 293 cells transfected by individual plasmids and digested with RNase-free DNase I before RT-PCR analysis. The pre-mRNAs 1, 2, and 3 (lanes 5 to 7, respectively) labeled above the agarose gel correspond to the pre-mRNAs 1, 2, and 3 in panel B. An untransfected 293 cell RNA control (lane 8) was also included. Mixtures of L2-S and L2-L cDNAs (spliced at nt 3605 and 3225, respectively) were prepared at the specified ratios and were used as PCR templates for quantitation and size controls. Predicted sizes of the RT-PCR products are 561 bp for nt 3225 3′ splice site usage and 181 bp for nt 3605 3′ splice site usage.

To create the ESS mutations or deletion in plasmid p3231, in vitro site-directed mutagenesis was carried out using a transformer site-directed mutagenesis kit (Clontech Laboratories, Inc., Palo Alto, Calif.). Two mutagenic primers and one selection primer were used for the mutagenesis. The mutagenic primer ESSm (5′-GCCCAGCCTGTCTCTTCTTTGCTCATTGTGCAGTGCTTGCGCGTGCAAGAGAGCAGGCCTCGG-3′) had extensive mutations in the central C-rich functional core sequence (53). The mutagenic primer ESSd (5′-CCCAGCCTGTCTCTTCTTTGCCCTCGGTTGGGTACGGG-3′) had an entire deletion of both the central C-rich region and the AG-rich 3′ end of the ESS. The selection primer (5′-GGGACGCCAATTGGTAATCATGG-3′) spans the EcoRI site at the junction between BPV-1 and pUC18 and destroys this restriction endonuclease cleavage site. All mutations were verified by DNA sequencing. The new plasmid with the ESS mutations was named p3035 (pZMZ TM5-3 or pESSm), and the new plasmid with the ESS deletion was named p3036 (pZMZ TM6-1 or pESSd).

Four of our previously published plasmids, p3031, p3032, p3033, and p3034 (51), were used to create a double mutation of both SE1 and SE2 in a BPV-1 late transcript expression vector. Briefly, the XhoI and Asp718 fragments containing SE1 mutations in plasmid p3031 or an SE1 deletion in plasmid p3032 were swapped, respectively, into the corresponding sites of plasmid p3033 (pSE2m) and p3034 (pSE2d). This strategy created a plasmid, p3078 (pZMZ58), with both SE1 and SE2 mutations and a plasmid, p3079 (pZMZ59), with both SE1 and SE2 deletions.

To create a BPV-1 late pre-mRNA expression vector containing a double mutation of both the ESS and SE2, the XhoI and Asp718 fragments containing ESS mutations in plasmid p3035 or an ESS deletion in plasmid p3036 were individually swapped into the corresponding sites of plasmid p3033 (pSE2m). The new plasmids created are p3080 (pZMZ60 or pESSm+SE2m) and p3081 (pZMZ61 or pESSd+SE2m).

DNA template preparation, in vitro splicing, and detection of splicing products.

Plasmid p3030, which transcribes a BPV-1 late pre-mRNA with a wild-type (wt) 3′ splice site at nt 3225, and plasmid p3082, which transcribes a BPV-1 late pre-mRNA with a human β-globin BPS and optimal PPT at the nt 3225 3′ splice site, were used for preparation of DNA templates by PCR using a common 5′ sense primer, Pr7276 (oFD127, a chimeric T7/BPV-1 primer), in combination with one of the following 3′ antisense primers: oZMZ127 (pre-mRNA 1 in Fig. 3A), oZMZ84 (pre-mRNA 2 in Fig. 3A), or oZMZ102 (pre-mRNA 3 in Fig. 3A). The sequences of the three primers oZMZ127, oZMZ84, and oZMZ102 have been reported in our previous publication (52).

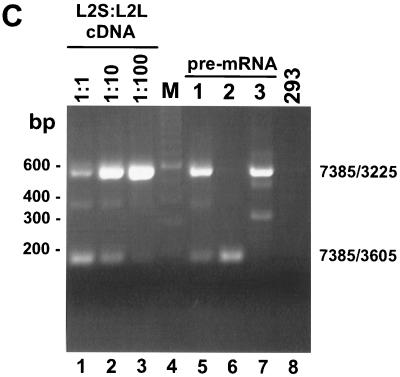

FIG. 3.

Conversion of the suboptimal nt 3225 3′ splice site to an optimal 3′ splice site in BPV-1 late pre-mRNAs overcomes suppression of in vitro splicing by the ESS. (A) Structures of the pre-mRNAs used for in vitro splicing assay. Numbers above pre-mRNA exons (large boxes) and introns (lines) are the nucleotide positions in the BPV-1 genome. mt ESE (Py3)2 and BPV-1 SE1 and ESS are shown as labeled boxes. Both wt or mt BPS and PPT at the 3′ end of each intron are shown as a thick grey line, and their sequence compositions are displayed in Fig. 2A. Plasmid p3030, which transcribes a pre-mRNA with a wt 3′ splice site at nt 3225, and plasmid p3082, which transcribes a pre-mRNA with a human β-globin BPS and strong PPT at the nt 3225 3′ splice site, were used for preparation of DNA templates by PCR. Thus, the pre-mRNAs with or without SE1 and/or an ESS element transcribed from p3030 DNA templates have a wt nt 3225 3′ splice site, whereas the pre-mRNAs with the same structures transcribed from p3082 DNA templates have an mt nt 3225 3′ splice site. Splicing efficiency for each pre-mRNA (% = spliced products/spliced products + unspliced RNA) was calculated from the splicing gel in panel B. (B) Electrophoresis of splicing products after in vitro splicing reactions carried out at 30°C for 2 h in the presence of 40% HeLa nuclear extracts and 0.5 mM MgCl2. Electrophoresis was performed on an 8% polyacrylamide gel containing 8 M urea. The identities of the spliced products and splicing intermediates are shown on the right of the gel. One representative splicing gel of three is shown.

Pre-mRNAs were prepared using Promega's riboprobe system (Promega, Madison, Wis.). In vitro runoff transcription was carried out with T7 RNA polymerase in the presence of the cap analog (m7GpppG) and [α-32P]rGTP as described by the company protocol. HeLaSplice nuclear extracts used for in vitro splicing assays were commercially obtained from Promega. The in vitro splicing assay and detection of splicing products have been described in our previous report (49).

Transfection of 293 cells and reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) and Northern blot analysis of spliced BPV-1 late mRNAs.

Transfectam reagent (Promega) was used to transfect 2 μg of wt or mutant (mt) expression vector DNA into human 293 cells plated in 60-mm-diameter dishes. Total cellular RNA was prepared after 48 h using TRIzol (GIBCO BRL, Rockville, Md.) following the manufacturer's instructions. Following DNase I treatment, 500 ng of total cellular RNA was reverse transcribed at 42°C using random hexamers as primers and then amplified for 35 cycles using different pairs of primers as described in the figure legends. An L1 cDNA and a mixture of L2-L and L2-S cDNAs generated from L2 mRNAs spliced using the nt 3225 3′ splice site and nt 3605 3′ splice site, respectively, were used as PCR controls.

For Northern blot analysis, total cell RNA (40 μg) was poly(A) selected using the Promega PolyATtract mRNA Isolation System III. Equal amounts of the poly(A)-selected RNAs were then denatured at 55°C for 15 min in formaldehyde-formamide sample buffer (60% formamide, 2.2 M formaldehyde, 25 μg of ethidium bromide per ml, 1× MOPS [morpholinepropanesulfonic acid] buffer) and run on a 1% agarose-formaldehyde gel. After electrophoresis was completed, the gel was washed for 5 min with water, partially hydrolyzed for 5 min in 50 mM NaOH–10 mM NaCl, neutralized for 5 min in 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) buffer, and transferred in 20× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) for 1.5 h to a GeneScreen membrane using a Pharmacia vacuum blotting device. After UV cross-linking in a Stratalinker (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) and photography, the membrane was hybridized with 32P-labeled BPV-1 early probe based on Church's protocol (8). The probe was prepared from a PCR-generated BPV-1 DNA template (nt 3211 to nt 4230) and was labeled using a Prime-It II random primer labeling kit (Stratagene) to a specific activity of ∼4 × 109 cpm/μg and used at ∼3 × 106 cpm/ml in the hybridization reaction. The 32P-labeled BPV-1 early probe should hybridize to all species of the alternatively spliced mRNAs.

RESULTS

The BPV-1 ESS inhibits selection of an upstream 3′ splice site in vivo.

Our previous studies demonstrated that BPV-1 late pre-mRNAs have three cis elements that reside between two alternative 3′ splice sites, the nt 3225 3′ splice site and the nt 3605 3′ splice site (Fig. 1A). We have utilized a series of BPV-1 late minigene expression vectors to analyze the function of these cis elements in vivo. Since the BPV-1 late promoter is inactive in cell culture, the BPV-1 late transcription unit was cloned downstream of the cytomegalovirus IE1 promoter. Care was taken to ensure that the 5′ ends of the BPV-1 late mRNAs expressed in transfection assays were similar to those expressed from the late promoter in BPV-1-infected warts. In transfection assays, the nt 3225 3′ splice site is used predominantly for splicing of the BPV-1 late pre-mRNA (51), (Fig. 1C, lane 6). Selection of this 3′ splice site requires both SE1 and SE2 (51). Mutation of either one of these enhancers results in splicing of the pre-mRNA using the nt 3605 3′ splice site (lanes 2 to 5 in Fig. 1C). However, mutation or deletion of only the ESS does not significantly affect BPV-1 late pre-mRNA splicing in 293 cells (Fig. 1C, lanes 10 and 11). These observations suggest that two strong ESEs (SE1 and SE2) are required to overcome suppression of the nt 3225 3′ splice site by the ESS. If this assumption is correct, SE1 should be sufficient for selection of the nt 3225 3′ splice site in the absence of the ESS. To address this fundamental question, we replaced or deleted the most important functional region of the ESS (53) in the context of a BPV-1 late gene expression vector which already had SE2 mutations or deletions (51). These plasmids were used to transfect 293 cells, and splicing of the BPV-1 late pre-mRNA was analyzed by RT-PCR and Northern blotting. As expected, wt BPV-1 late pre-mRNA is predominately spliced using the nt 3225 3′ splice site, and mutation or deletion of both SE1 and SE2 resulted in a switch to predominant utilization of the nt 3605 3′ splice site (Fig. 1D and E). The effects of double ESE mutations are similar to that seen for SE1 or SE2 mutation alone (lanes 2 to 5 in Fig. 1C). However, point mutations in the ESS in the context of a pre-mRNA containing point mutations in SE2 (ESSm + SE2m) partially restored utilization of the nt 3225 3′ splice site (lane 8 in Fig. 1D; also Fig. 1E). Even more dramatic was the effect of deletion of the ESS (ESSd + SE2m) (lane 9 in Fig. 1D; also Fig. 1E). Two-thirds of this pre-mRNA was spliced at the nt 3225 3′ splice site (Fig. 1E). This experiment suggests that SE1 enhances selection of the nt 3225 3′ splice site in the absence of the ESS. We conclude from these in vivo experiments that the ESS suppresses SE1-stimulated pre-mRNA splicing. In addition, SE2 is required to compensate for this suppression, even though SE2 is positioned 125 nt downstream of the ESS and 252 nt downstream of the nt 3225 3′ splice site.

Strengthening the weak nt 3225 3′ splice site counteracts the function of the ESS in vivo.

Previously, we have shown that the BPV-1 ESS functions only in a suboptimal 3′ splice site-containing pre-mRNA and that its negative effect on splicing is independent of ESEs (52). We also demonstrated that the BPV-1 nt 3225 3′ splice site contains a suboptimal BPS and PPT (50). This suggests that we may be able to neutralize the function of the ESS in a BPV-1 late pre-mRNA by strengthening the weak nt 3225 3′ splice site. To test this hypothesis, a strong BPS from the human β-globin pre-mRNA intron 1 was introduced to replace the suboptimal BPS at the nt 3225 3′ splice site of a BPV-1 late pre-mRNA expression vector containing SE2 point mutations (Fig. 2A). Human β-globin pre-mRNA intron 1 has a consensus BPS (CACUGAC) similar to the mammalian consensus BPS (YNYURAC) (30). In addition, three point mutations (R to U) in the PPT and a UAG-to-CAG mutation in the 3′ splice junction (Fig. 2A) were also made in the nt 3225 3′ splice site of the same plasmid (see Materials and Methods). These mutations in the nt 3225 3′ splice site should convert this suboptimal splice site to an optimal splice site which would allow us to test our assumption. The new construct was then used to transfect 293 cells, and total cell RNA was analyzed by RT-PCR for alterations in splice site usage.

As we showed in Fig. 1C, mutation of SE2 in the context of a pre-mRNA containing a wt nt 3225 3′ splice site (pre-mRNA 2) switched splice site selection from nt 3225 to nt 3605 (lane 6 in Fig. 2C). In contrast, mutation of SE2 had no significant effect on nt 3225 3′ splice site utilization in a pre-mRNA containing an optimal nt 3225 3′ splice site (pre-mRNA 3) (lane 7 in Fig. 2C). These data suggest that splicing in vivo at the nt 3225 3′ splice site no longer requires SE2 because the ESS cannot suppress an optimal 3′ splice site. We conclude that a suboptimal nt 3225 3′ splice site is a prerequisite for the function of the BPV-1 ESS in vivo.

In vitro splicing of the BPV-1 pre-mRNAs with an optimized nt 3225 3′ splice site.

To further confirm the observation from our in vivo study described above, we used in vitro splicing assays to test if an optimized 3′ splice site in a pre-mRNA could counteract suppression of pre-mRNA splicing by the ESS. These studies look at the absolute effect of the ESS on a single 3′ splice site rather than on alternative splicing. Two sets of pre-mRNAs with either a suboptimal (wt) or an optimized (mt) 3′ splice site were prepared by in vitro transcription (see Materials and Methods). Each set of pre-mRNAs consisted of three different transcripts in which exon 2 contained either a mutant ESE, (Py3)2 (42, 50, 51); SE1; or SE1 plus the ESS (Fig. 3A, pre-mRNAs 1, 2, and 3, respectively). These pre-mRNAs were then spliced in vitro using HeLa nuclear extracts. The results are shown in Fig. 3B and summarized in Fig. 3A as splicing efficiency (percent spliced) for individual pre-mRNA species. As expected, the ESS suppressed splicing of a wt pre-mRNA with a threefold reduction of splicing efficiency (compare wt pre-mRNA 3 to wt pre-mRNA 2 in both Fig. 3A and B). However, when the pre-mRNAs had an optimized (mt) nt 3225 3′ splice site, both mt pre-mRNAs were spliced with similar efficiencies (compare mt pre-mRNA 3 to mt pre-mRNA 2 in both Fig. 3A and B). The data from these in vitro experiments confirm that the ESS is not able to suppress an optimal nt 3225 3′ splice site.

The BPV-1 ESE SE1 stimulates the second step of splicing of a BPV-1 late pre-mRNA.

We have reported previously that wt BPV-1 late pre-mRNAs without SE1 are very inefficiently spliced in vitro in comparison to wt pre-mRNAs containing SE1 (50, 52). In the experiment shown in lanes 4 and 5 in Fig. 3B, pre-mRNA 1 containing a wt (suboptimal) nt 3225 3′ splice site and mutant ESE (Py3)2 (wt pre-mRNA 1 in Fig. 3A) was spliced nine times less efficiently than the wt pre-mRNA containing SE1 (wt pre-mRNA 2 in Fig. 3A). In contrast, both pre-mRNAs, 1 and 2, were spliced efficiently when they contained an mt (optimal) nt 3225 3′ splice site (compare mt pre-mRNAs 1 and 2 in Fig. 3A). Surprisingly, a careful examination of the spliced products revealed that splicing of the mt pre-mRNA 1 with (Py3)2 produced mostly splicing intermediates generated from the first step of the splicing reaction (lane 1 in Fig. 3B). No fully spliced products resulting from the ligation of exon 1 to exon 2 were detected. In contrast, mt pre-mRNA 2 with SE1 produced not only splicing intermediates but also fully spliced products (lane 2 in Fig. 3B). The percentage of the starting pre-mRNA found in splicing intermediates was 56% for the mt pre-mRNA 1 with (Py3)2 and only 36% for the mt pre-mRNA 2 with SE1. The smaller amount of splicing intermediates from mt pre-mRNA 2 with SE1 is most likely due to increased efficiency of the second step of splicing for this pre-mRNA. These data suggest that BPV-1 SE1 can function not only by stimulating early steps in spliceosomal assembly but also by enhancing the second step of splicing. Thus, although a strong 3′ splice site is sufficient for the first step of splicing, in some cases a strong ESE may be required for the second step.

DISCUSSION

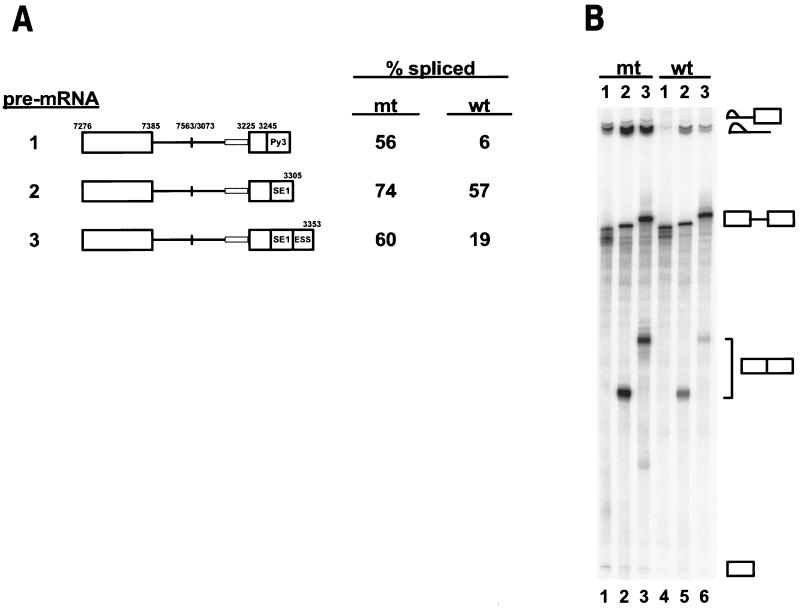

The BPV-1 ESS was originally identified in an in vitro splicing assay using pre-mRNAs containing only the nt 3225 3′ splice site (50). In this context, the ESS blocks splicing enhanced by the enhancer SE1. Here we have used these constructs in transfection assays and demonstrated that the ESS also acts as a splicing suppressor in vivo and plays an important role in the regulation of alternative splicing in a BPV-1 late pre-mRNA that contains both the nt 3225 3′ splice site and the nt 3605 3′ splice site. Our data are consistent with the model presented in Fig. 4 where two strong ESEs (SE1 and SE2) are required to overcome the effect of the ESS and select the nt 3225 3′ splice site as the dominant splice site at early stages of the viral life cycle. Thus, when both SE1 and SE2 are present, mutation of the ESS has little effect on alternative splicing. Deletion of the ESS may give a slight increase in usage of the nt 3225 3′ splice site with a reciprocal decrease in utilization of the nt 3605 3′ splice site, but this is difficult to accurately assess using a competitive PCR assay (Fig. 1C, lanes 10 and 11). In contrast, the splicing suppressor activity of the ESS can easily be demonstrated when the balance between nt 3225 and nt 3605 3′ splice site selection is altered by mutations in one of the splicing enhancers (Fig. 1D and E).

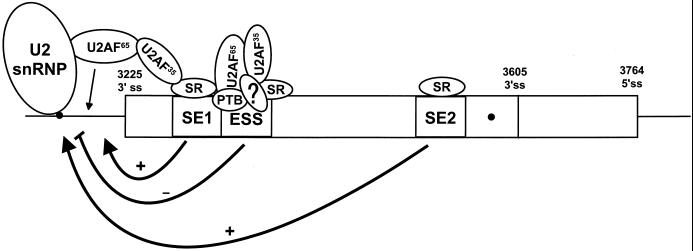

FIG. 4.

A proposed model for the function of the BPV-1 ESS in regulation of BPV-1 alternative splicing. Selection of the suboptimal nt 3225 3′ splice site is regulated through three viral cis-acting elements, two ESEs (SE1 and SE2) and one ESS. The ESEs stimulate splicing at the nt 3225 3′ splice site through recruitment of splicing factors at early stages of spliceosome assembly (55). The ESS plays a negative role in the selection of the nt 3225 3′ splice site through interaction with different cellular splicing factors (53). In the normal context, the combination of two ESEs overcomes the negative effect of the ESS on the nt 3225 3′ splice site and drives splicing to use predominately the nt 3225 3′ splice site. Cellular splicing factors such as SR proteins appear to play a key role in this regulation, and their physiological status might affect each cis element's function and consequently alternative splicing of the BPV-1 late pre-mRNA. 3′ ss, 3′ splice site; 5′ ss, 5′ splice site; ?, hypothetical factor(s). Circles, BPS.

The data presented here also provide further evidence in support of the notion that the function of the BPV-1 ESS requires a suboptimal 3′ splice site (52). Whereas two enhancers are needed in vivo to overcome splicing suppression by the ESS in the context of the wt suboptimal nt 3225 3′ splice site, only one enhancer is required when the nt 3225 3′ splice site has been optimized (Fig. 2). Optimization of the nt 3225 3′ splice site leads to a reciprocal increase in usage of the nt 3225 3′ splice site and a decrease in usage of the nt 3605 3′ splice site due to competition between the two sites. Likewise, in in vitro experiments the ESS gave only a 20% reduction of splicing of a pre-mRNA containing the optimized nt 3225 3′ splice site (Fig. 3). Our strategy to optimize the nt 3225 3′ splice site was to strengthen both the BPS and the PPT. This was achieved by replacing the suboptimal 3′ splice site with a combination of a human β-globin BPS (CACUGAC) and a 16-nt pyrimidine stretch followed by a CAG trinucleotide (30). This 3′ splice site should strongly bind both the U2 snRNP and U2AF65, even in the absence of a splicing enhancer. These data, taken together with our previous data showing that the function of the ESS does not require a splicing enhancer, suggest that the ESS blocks the binding of splicing factors to the suboptimal 3′ splice site. Several lines of evidence suggest that other ESS also require a suboptimal 3′ splice site for their function. In HIV-1 tat ESS studies, mutation of the interspersed purines to pyrimidines in the PPT of the HIV-1 tat exon 2 3′ splice site results in a significant increase in splicing efficiency of an ESS-containing pre-mRNA in vitro (34). Likewise, optimization of either the BPS or the PPT in the HIV-1 tat exon 3 3′ splice site also eliminates most of the splicing suppression by the ESS3 in vivo (38).

A surprising finding of our study is the observation that the BPV-1 ESE SE1 is capable of stimulating not only the first step of splicing but also the second step of the two-step transesterification reaction. While we were preparing the manuscript, Chew and coworkers (7) also demonstrated that an ASF/SF2-specific ESE promotes the second step in splicing. The first catalytic step involves cleavage at the 5′ splice site, which generates a free 5′ exon and a lariat (intron)-containing 3′ exon. The second step is the cleavage at the 3′ splice site with simultaneous joining of the two exons and release of the intron as a lariat form (21, 25, 43). Splicing of mammalian pre-mRNAs, which frequently have suboptimal 3′ splice sites, in many cases depends upon ESEs in the 3′ exon which bind SR proteins (29, 51). In currently accepted models for the function of an ESE, the RS domain of ESE-bound SR proteins interacts with the RS domain of U2AF35, which then recruits U2AF65 to the suboptimal PPT, promoting the binding of the U2 snRNP to the suboptimal BPS (3, 14, 55). However, it is unclear what role the ESE and SR proteins play during the second step of splicing. Our data suggest that a consensus BPS or optimal PPT or both promotes only the first step of splicing. This observation indicates that the presence of an ESE in 3′ exons is essential for a complete splicing reaction and therefore suggests that ESEs should be universally present no matter whether the 3′ splice site is suboptimal or whether it is optimal. This ESE may not be limited to a purine-rich enhancer. Consistent with this hypothesis, a recent report indicates that splicing of the human β-globin intron 1, which contains a consensus BPS, also requires an ESE in the 3′ exon (33). One possible role for SR proteins and ESEs in the second step of splicing is to directly promote bridging across the intron (40).

One key issue that remains is what splicing factors regulate BPV-1 alternative splicing during the viral life cycle. The switch from utilization of the nt 3225 3′ splice site at early times of the viral life cycle to use of the nt 3605 3′ splice site at late stages is an integral component of the early to late switch in viral gene expression and is intimately linked to keratinocyte differentiation (2). Identification of the viral cis-acting splicing elements between the two alternative 3′ splice sites and elucidation of their functions in vitro and in vivo have provided a basis for understanding the mechanism of splice site selection (Fig. 4). Our in vivo studies suggest that the early to late switch in splicing could result from either a decrease in enhancer activity or an increase in activity of the ESS. As mentioned above, the functions of SE1 and SE2 are mediated at least in part by SR proteins (51). It is not yet known if the activity of one or more SR proteins changes during keratinocyte differentiation. However, it has been shown that SR protein levels and their differential expression as well as physiological status are all important for regulation of alternative splicing (1, 4, 12, 19, 28, 44). A recent study indicates that developmental regulation of SR protein activity in the nematode Ascaris lumbricoides plays a role in activation of pre-mRNA splicing during early development (32). Other reports also suggest that alterations in the expression of a subset of SR proteins and alternative splicing of a CD44 pre-mRNA accompany the transition from normal cells to mouse mammary adenocarcinoma (41) and human colon adenocarcinomas (13). Viral proteins can also regulate SR protein function. The adenovirus E4-ORF4 protein is an early viral protein that activates protein phosphatase 2A, leading to the dephosphorylation and inactivation of SR proteins (18). An early to late shift in 3′ splice site utilization results from decreased SR protein binding to an intronic splicing suppressor. The function of the BPV-1 ESS is also thought to be mediated through the binding of cellular splicing factors, including SR proteins and perhaps other as-yet-unidentified proteins (53). Therefore, we predict that the differential expression and/or modification of cellular splicing factors during keratinocyte differentiation and virus infection will be a key component of the regulation of BPV-1 gene expression at the posttranscriptional level.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bai Y D, Lee D, Yu T D, Chasin L A. Control of 3′ splice site choice in vivo by ASF/SF2 and hnRNP A1. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:1126–1134. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.4.1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barksdale S K, Baker C C. Differentiation-specific alternative splicing of bovine papillomavirus late mRNAs. J Virol. 1995;69:6553–6556. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.10.6553-6556.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buvoli M, Mayer S A, Patton J G. Functional crosstalk between exon enhancers, polypyrimidine tracts and branchpoint sequences. EMBO J. 1997;16:7174–7183. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.23.7174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caceres J F, Stamm S, Helfman D M, Krainer A R. Regulation of alternative splicing in vivo by overexpression of antagonistic splicing factors. Science. 1994;265:1706–1709. doi: 10.1126/science.8085156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caputi M, Mayeda A, Krainer A R, Zahler A M. hnRNP A/B proteins are required for inhibition of HIV-1 pre-mRNA splicing. EMBO J. 1999;18:4060–4067. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.14.4060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen C D, Kobayashi R, Helfman D M. Binding of hnRNP H to an exonic splicing silencer is involved in the regulation of alternative splicing of the rat β-tropomyosin gene. Genes Dev. 1999;13:593–606. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.5.593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chew S L, Liu H X, Mayeda A, Krainer A R. Evidence for the function of an exonic splicing enhancer after the first catalytic step of pre-mRNA splicing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:10655–10660. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Church G M, Gilbert W. Genomic sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:1991–1995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.7.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Del Gatto-Konczak F, Olive M, Gesnel M C, Breathnach R. hnRNP A1 recruited to an exon in vivo can function as an exon splicing silencer. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:251–260. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fang G, Weiser B, Visosky A, Moran T, Burger H. PCR-mediated recombination: a general method applied to construct chimeric infectious molecular clones of plasma-derived HIV-1 RNA. Nat Med. 1999;5:239–242. doi: 10.1038/5607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fu X Y, Ge H, Manley J L. The role of the polypyrimidine stretch at the SV40 early pre-mRNA 3′ splice site in alternative splicing. EMBO J. 1988;7:809–817. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02879.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ge H, Manley J L. A protein factor, ASF, controls cell-specific alternative splicing of SV40 early pre-mRNA in vitro. Cell. 1990;62:25–34. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90236-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghigna C, Moroni M, Porta C, Riva S, Biamonti G. Altered expression of heterogenous nuclear ribonucleoproteins and SR factors in human colon adenocarcinomas. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5818–5824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graveley B R, Hertel K J, Maniatis T. A systematic analysis of the factors that determine the strength of pre-mRNA splicing enhancers. EMBO J. 1998;17:6747–6756. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.22.6747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green M R. Pre-mRNA splicing. Annu Rev Genet. 1986;20:671–708. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.20.120186.003323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ho S N, Hunt H D, Horton R M, Pullen J K, Pease L R. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1989;77:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanaar R, Roche S E, Beall E L, Green M R, Rio D C. The conserved pre-mRNA splicing factor U2AF from Drosophila: requirement for viability. Science. 1993;262:569–573. doi: 10.1126/science.7692602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanopka A, Mühlemann O, Petersen-Mahrt S, Estmer C, Öhrmalm C, Akusjärvi G. Regulation of adenovirus alternative RNA splicing by dephosphorylation of SR proteins. Nature. 1998;393:185–187. doi: 10.1038/30277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krainer A R, Conway G C, Kozak D. The essential pre-mRNA splicing factor SF2 influences 5′ splice site selection by activating proximal sites. Cell. 1990;62:35–42. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90237-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mayeda A, Screaton G R, Chandler S D, Fu X D, Krainer A R. Substrate specificities of SR proteins in constitutive splicing are determined by their RNA recognition motifs and composite pre-mRNA exonic elements. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1853–1863. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moore M J, Query C C, Sharp P A. Splicing of precursors to messenger RNAs by the spliceosome. In: Gestland R F, Atkins J F, editors. The RNA world. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1993. pp. 303–357. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mullen M P, Smith C W, Patton J G, Nadal-Ginard B. Alpha-tropomyosin mutually exclusive exon selection: competition between branchpoint/polypyrimidine tracts determines default exon choice. Genes Dev. 1991;5:642–655. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.4.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muro A F, Caputi M, Pariyarath R, Pagani F, Buratti E, Baralle F E. Regulation of fibronectin EDA exon alternative splicing: possible role of RNA secondary structure for enhancer display. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2657–2671. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.2657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Norton P A. Polypyrimidine tract sequences direct selection of alternative branch sites and influence protein binding. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:3854–3860. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.19.3854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Padgett R A, Grabowski P J, Konarska M M, Seiler S, Sharp P A. Splicing of messenger RNA precursors. Annu Rev Biochem. 1986;55:1119–1150. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.005351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parker R, Siliciano P G, Guthrie C. Recognition of the TACTAAC box during mRNA splicing in yeast involves base pairing to the U2-like snRNA. Cell. 1987;49:229–239. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90564-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Potashkin J, Naik K, Wentz-Hunter K. U2AF homolog required for splicing in vivo. Science. 1993;262:573–575. doi: 10.1126/science.8211184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prasad J, Colwill K, Pawson T, Manley J L. The protein kinase Clk/Sty directly modulates SR protein activity: both hyper- and hypophosphorylation inhibit splicing. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:6991–7000. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.6991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramchatesingh J, Zahler A M, Neugebauer K M, Roth M B, Cooper T A. A subset of SR proteins activates splicing of the cardiac troponin T alternative exon by direct interactions with an exonic enhancer. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4898–4907. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.9.4898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reed R. The organization of 3′ splice-site sequences in mammalian introns. Genes Dev. 1989;3:2113–2123. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.12b.2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roscigno R F, Weiner M, Garcia-Blanco M A. A mutational analysis of the polypyrimidine tract of introns. Effects of sequence differences in pyrimidine tracts on splicing. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:11222–11229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanford J R, Bruzik J P. Developmental regulation of SR protein phosphorylation and activity. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1513–1518. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.12.1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schaal T D, Maniatis T. Multiple distinct splicing enhancers in the protein-coding sequences of a constitutively spliced pre-mRNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:261–273. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Si Z H, Amendt B A, Stoltzfus C M. Splicing efficiency of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 tat RNA is determined by both a suboptimal 3′ splice site and a 10 nucleotide exon splicing silencer element located within tat exon 2. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:861–867. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.4.861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singh R, Valcarcel J, Green M R. Distinct binding specificities and functions of higher eukaryotic polypyrimidine tract-binding proteins. Science. 1995;268:1173–1176. doi: 10.1126/science.7761834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith C W, Porro E B, Patton J G, Nadal-Ginard B. Scanning from an independently specified branch point defines the 3′ splice site of mammalian introns. Nature. 1989;342:243–247. doi: 10.1038/342243a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Staffa A, Cochrane A. The tat/rev intron of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is inefficiently spliced because of suboptimal signals in the 3′ splice site. J Virol. 1994;68:3071–3079. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.3071-3079.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Staffa A, Cochrane A. Identification of positive and negative splicing regulatory elements within the terminal tat-rev exon of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4597–4605. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Staknis D, Reed R. SR proteins promote the first specific recognition of pre-mRNA and are present together with the U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle in a general splicing enhancer complex. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:7670–7682. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.11.7670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stark J M, Bazett-Joness D P, Herfort M, Roth M B. SR proteins are sufficient for exon bridging across an intron. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2163–2168. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stickeler E, Kittrell F, Medina D, Berget S M. Stage-specific changes in SR splicing factors and alternative splicing in mammary tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 1999;18:3574–3582. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tanaka K, Watakabe A, Shimura Y. Polypurine sequences within a downstream exon function as a splicing enhancer. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:1347–1354. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.2.1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Umen J G, Guthrie C. The second catalytic step of pre-mRNA splicing. RNA. 1995;1:869–885. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang J, Manley J L. Overexpression of the SR proteins ASF/SF2 and SC35 influences alternative splicing in vivo in diverse ways. RNA. 1995;1:335–346. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu J, Manley J L. Mammalian pre-mRNA branch site selection by U2 snRNP involves base pairing. Genes Dev. 1989;3:1553–1561. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.10.1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zamore P D, Patton J G, Green M R. Cloning and domain structure of the mammalian splicing factor U2AF. Nature. 1992;355:609–614. doi: 10.1038/355609a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang L, Stoltzfus C M. A suboptimal src 3′ splice site is necessary for efficient replication of Rous sarcoma virus. Virology. 1995;206:1099–1107. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang M Q. Statistical features of human exons and their flanking regions. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:919–932. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.5.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zheng Z M, Baker C C. Parameters that affect in vitro splicing of bovine papillomavirus type 1 late pre-mRNAs. J Virol Methods. 2000;85:203–214. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(99)00172-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zheng Z M, He P J, Baker C C. Selection of the bovine papillomavirus type 1 nucleotide 3225 3′ splice site is regulated through an exonic splicing enhancer and its juxtaposed exonic splicing suppressor. J Virol. 1996;70:4691–4699. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4691-4699.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zheng Z M, He P J, Baker C C. Structural, functional, and protein binding analyses of bovine papillomavirus type 1 exonic splicing enhancers. J Virol. 1997;71:9096–9107. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9096-9107.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zheng Z M, He P J, Baker C C. Function of a bovine papillomavirus type 1 exonic splicing suppressor requires a suboptimal upstream 3′ splice site. J Virol. 1999;73:29–36. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.29-36.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zheng Z M, Huynen M, Baker C C. A pyrimidine-rich exonic splicing suppressor binds multiple RNA splicing factors and inhibits spliceosome assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14088–14093. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhuang Y, Weiner A M. A compensatory base change in human U2 snRNA can suppress a branch site mutation. Genes Dev. 1989;3:1545–1552. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.10.1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zuo P, Maniatis T. The splicing factor U2AF35 mediates critical protein-protein interactions in constitutive and enhancer-dependent splicing. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1356–1368. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.11.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]