Abstract

Based on the auditory periphery and the small head size, Etruscan shrews (Suncus etruscus) approximate ancestral mammalian conditions. The auditory brainstem in this insectivore has not been investigated. Using labelling techniques, we assessed the structures of their superior olivary complex (SOC) and the nuclei of the lateral lemniscus (NLL). There, we identified the position of the major nuclei, their input pattern, transmitter content, expression of calcium binding proteins (CaBPs) and two voltage-gated ion channels. The most prominent SOC structures were the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body (MNTB), the lateral nucleus of the trapezoid body (LNTB), the lateral superior olive (LSO) and the superior paraolivary nucleus (SPN). In the NLL, the ventral (VNLL), a specific ventrolateral VNLL (VNLLvl) cell population, the intermediate (INLL) and dorsal (DNLL) nucleus, as well as the inferior colliculus’s central aspect were discerned. INLL and VNLL were clearly separated by the differential distribution of various marker proteins. Most labelled proteins showed expression patterns comparable to rodents. However, SPN neurons were glycinergic and not GABAergic and the overall CaBPs expression was low. Next to the characterisation of the Etruscan shrew’s auditory brainstem, our work identifies conserved nuclei and indicates variable structures in a species that approximates ancestral conditions.

Keywords: Auditory brainstem, Etruscan shrew, Inferior colliculus, Lateral lemniscus, Superior olivary complex

Subject terms: Auditory system, Neural circuits

Introduction

The Etruscan shrew (Suncus etruscus) is probably the smallest recent terrestrial mammal. This about 2 g and 4 cm large Eulipotyphla lives in the southern Palaearctic belt1,2. Due to their small body size and thus, a large surface-to-volume ratio, Etruscan shrews invest much time in hunting to meet their high-energy demands3. At close proximity to their prey, they make use of their sensitive vibrissae system3,4. In distance to a prey, they likely use their hearing abilities. Their good hearing performance may be derived from their large pinna, their estimated impedance at the eardrum and their hunting behaviour in darkness5. Etruscan shrews are considered to be high-frequency listeners because of their middle ear formation5 and their head size. Mammals with very small heads are proposed to unlikely detect sound sources based on low frequencies6,7. Together, these anatomical constraints might suggest that Etruscan shrews approximate the mammalian ancestral auditory periphery.

Auditory information is processed in the brainstem and hindbrain in various gross structures including the superior olivary complex (SOC), the nuclei of the lateral lemniscus (NLL) and the inferior colliculus (IC). The nuclei of these regions are considered to be functionally conserved throughout mammalian evolution6,7. Despite the conservative aspect, the shape and location of auditory nuclei can differ between species, especially in the SOC6,7 and the lateral lemniscus (LL)8. Following from their conserved presence, the connectivity between auditory nuclei is considered to be conserved on the gross scale. However, small but significant differences in the connectivity pattern and input location exist, as exemplified for inhibitory inputs in the medial superior olive (MSO)9. Therefore, the structural arrangement and the synaptic location is species-dependent.

The SOC is composed of at least six different sub-nuclei localised from medial to lateral: the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body (MNTB), the ventral nucleus of the trapezoid body (VNTB), the MSO, the superior paraolivary nucleus (SPN), the lateral superior olive (LSO) and the lateral nucleus of the trapezoid body (LNTB). Functionally, the MNTB is a temporally precise hub providing glycinergic feed-forward inhibition to SOC, NLL and thalamic nuclei10. Other local and long range inhibitory projections arise from the VNTB and LNTB11–14. The MSO and LSO are the binaural integration centres for low- and high-frequency sound source localisation6,7. The SPN is implicated in the detection of stimulus gaps and endings by generating offset responses15–17. Next to these main SOC nuclei, other less structured neuronal populations such as periolivary subregions as well as the medial and lateral olivocochlear bundle cells exist that provide important feedback to the cochlea.

Within the fibres of the LL, three nuclei can be identified termed according to their location in ventral, intermediate and dorsal nucleus of the lateral lemniscus (VNLL, INLL and DNLL)18,19. Within the VNLL, a subpopulation of globular neurons receive a large, somatic endbulb synapse20,21. Because this cell population locates at different positions within the VNLL across mammalian species, it obtained additional annotations8,19,22. The VNLL generates a rapid glycinergic and γ-aminobutyric-acid (GABA)-ergic feed-forward inhibition23 that serves to at least suppress spurious frequencies that occur during spectral splatter24. The INLL was indicated in cross-frequency integration in bats25. The reciprocal connection of GABAergic neurons in the DNLL serves various binaural functions26–28. Other neuronal populations in the lateral lemniscus are functionally less understood and consist of the subiculum, H-cells of the semilunar nucleus and the paralemniscal zone29,30. Most of the information of the SOC and the NLL is fed into the central nucleus of the inferior colliculus (ICc) in the midbrain, a main auditory integration centre.

Temporal precision is a hallmark of the auditory brainstem produced by structural and molecular adaptations. Large somatic synapses like the calyx of Held and endbulb synapses in the LNTB and VNLL allow for rapid synaptic information transfer21,31,32. Potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily A member 1 (Kv1.1) channels have low voltage activation accelerating sub-threshold integration to produce temporally precise supra-threshold output33–35. Hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated channel 1 (HCN1) channels underlie hyperpolarising activated cation currents producing short integration times and offset firing15,16,36,37. Finally, oligodendrocytes myelinate axons and axon/ myelin thickness is adapted to specific circuit requirements38–40 adjusting propagation speeds. Therefore, specific structural components and molecular compositions endow the auditory system with its temporal precision and rapid voltage signalling.

Here, we determined the architecture of the SOC and the NLL in the Etruscan shrew. To identify the nuclei of these auditory regions, we labelled structural markers (microtubule-associated protein 2 [MAP2] and neuronal nuclear antigen [NeuN]), synaptic markers (vesicular glutamate transporter 1 [VGluT1] and vesicular γ-Aminobutyric acid transporter [VGAT]), transmitters (GABA and glycine), calcium binding proteins (CaBPs; calbindin [CB], calretinin [CR] and parvalbumin [PV]) and voltage-gated ion channels (HCN1 and Kv1.1). Most major nuclei of the SOC and LL could be identified and morphologically characterised, but the MSO and VNTB could not be unambiguously addressed. In addition, the expression pattern of CaBPs and voltage-gated ion channels allows suggestions about functional aspects.

Results

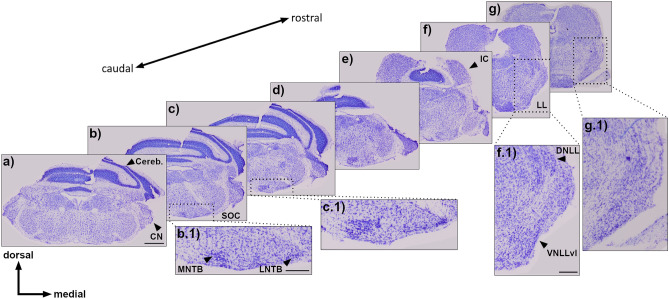

In Nissl stained serial sections of the Etruscan shrew (Fig. 1a–g), within the SOC, the MNTB and LNTB were identified by their densely packed roundish somata (Fig. 1b.1). Other SOC nuclei like the LSO, MSO or SPN were not unambiguously delineated. On the lateral edges of the caudal hindbrain sections, the cochlea nucleus and dorsally the cerebellum (Cereb.) could be identified. Within the LL, a region of densely packed roundish somata defined the ventrolateral part of the VNLL (VNLLvl, Fig. 1f.1). The remaining VNLL was not clearly separable from the dorsally located INLL. The DNLL appeared densely packed and oval. The IC could be distinguished morphologically by its position on the dorsolateral edge of the hindbrain.

Figure 1.

Nissl staining of brainstem to hindbrain sections. (a–g) Series of sections with every 120th µm shown from caudal to rostral, from SOC to NLL. Magnifications in (b.1) and (c.1) of the SOC are demarcated by dotted boxes, (f.1) and (g.1) show the NLL. Black arrow heads show key structures in the brain. Scale bar equals 500 µm. (b.1, c.1) Magnifications show SOC from two sections. Black arrow heads show key structures within the SOC. Scale bar equals 200 µm. Abbreviations: lateral nucleus of the trapezoid body, LNTB; medial nucleus of the trapezoid body, MNTB. (f.1, g.1) Magnifications show LL from two sections. Arrow heads show key structures of the LL. Scale bar equals 200 µm. DNLL dorsal nucleus of the lateral lemniscus, VNLLvl ventrolateral part of the ventral nucleus of the trapezoid body, Cereb cerebellum, CN cochlea nucleus, IC inferior colliculus, LL lateral lemniscus, SOC superior olivary complex.

Distribution of structural and synaptic markers

To seek identification and location of neuronal populations, we first used the neuronal post-synaptic markers MAP2 and NeuN in combination with VGluT1 that was used as a structural marker. With this combination, we identified in the SOC (from medial to lateral): MNTB, SPN, a central region, LSO and LNTB (Fig. 2a). The central region could not be further segregated and might be composed of a more heterogeneous cell population possibly including MSO and VNTB neurons. In the SOC, MAP2 immunofluorescence was weakest in somata and proximal dendrites of MNTB and LNTB neurons (Fig. 2a, b). In the SPN, the central region and the LSO, MAP2 immunofluorescence clearly labelled somata and proximal dendrites. NeuN immunofluorescence was present throughout the SOC neurons with variable intensity labelling their nucleus and soma (Fig. 2a, b).

Figure 2.

MAP2, NeuN and VGluT1 labelling in the SOC allows approximate identification of nuclei. (a) Overview of MAP2 (green), NeuN (magenta) and VGluT1 (blue) co-labelling in the SOC. The different SOC regions were delineated (dotted lines) and show from i (medial) to v (lateral): the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body (MNTB; i), superior paraolivary nucleus (SPN; ii), central SOC region (iii), lateral superior olive (LSO; iv) and the lateral nucleus of the trapezoid body (LNTB; v). The location of the labelling (i–v) corresponds to the region from which the images in b were taken. Scale bar equals 200 µm. (b) Magnifications of each identified region (i–v) shown as overlay (top row) with the corresponding gray scaled images depicted vertically. Scale bar equals 20 µm.

All annotated SOC regions receive glutamatergic synaptic input detected by VGluT1 labelling (Fig. 2b). In the MNTB, large somatic VGluT1-positive synapses, presumably calyces of Held, were present. Sparse VGluT1 labelling dorsolateral to the MNTB is in accord with earlier identifications of the SPN22,41. Within the central region, small VGluT1 labelled synaptic structures were observed, but did not support further subdivision of this region (Fig. 2a, b). The LSO displays moderate VGluT1 labelling. Large somatic VGluT1-positive synapses identified the LNTB on the ventrolateral edge of the SOC (Fig. 2b).

To verify this initial identification, we seek insights into the input patterns originating from the cochlear nucleus, by biocytin labelling (Fig. 3). Ipsilateral applied biocytin labelled a large fiber bundle on the ventral edge of the section that crossed the midline (Fig. 3a). Ipsilaterally, biocytin labelling was observed in the SPN, the central region, the LSO and the LNTB but hardly in the MNTB (Fig. 3b). Contralaterally, in the MNTB, calyx terminals were visible. Furthermore, contralateral inputs were observed in the SPN, the central region and the LNTB. These input patterns corroborated our previous SOC annotations, as they are in line with the known mammalian circuitry42.

Figure 3.

Biocytin tracing in Etruscan shrew. (a) Overview of ventral brainstem after biocytin injection (magenta) in the left cochlear nucleus (ipsilateral) and VGluT1 co-labelling (green). Previously identified nuclei are marked alongside by i–v. The location of the labelling (i–v) corresponds to the region from which the images in b were taken. Scale bar equals 200 µm. (b) Magnifications of the different ipsi- and contralateral SOC regions (i–v) shown as overlay. Below each overlay are the gray scale images of the tracer. Scale bar equals 20 µm.

Since the co-labelling of structural markers with VGluT1 successfully identified SOC nuclei, we continued to determine the presence of known nuclei in the LL and the IC by this labelling approach (Fig. 4). The ICc could be distinguished by the intense and dense NeuN and VGluT1 labelling, whereas MAP2 labelling appeared less intense (Fig. 4b). Ventral to the IC, minor VGluT1, strong NeuN and faint MAP2 labelling indicated the position of the DNLL (Fig. 4b) matching the Nissl staining. Compared to the DNLL, the INLL and the VNLL have stronger VGluT1 labelling. In these structures, NeuN labelled cell nuclei and somata, while MAP2 labelling was more distinct and localized at somata and dendrites (Fig. 4b). More intensive NeuN labelling occurred in the VNLL compared to the INLL (Fig. 4a, b). The VNLLvl was clearly distinguishable by its big, somatic glutamatergic endbulb synapses (Fig. 4b), specific for this cell population20,21.

Figure 4.

MAP2, NeuN and VGluT1 labelling in the NLL and IC supports the nuclei identification. (a) Overview of MAP2 (green), NeuN (magenta) and VGluT1 (blue) co-labelling in the LL and IC. Nuclei were delineated (dotted lines), showing from dorsal (top; i) to ventral (bottom; v): central nucleus of the inferior colliculus (ICc; i), the dorsal nucleus of the LL (DNLL; ii), the intermediate nucleus of the LL (INLL; iii), the ventral nucleus of the LL (VNLL; iv) and the ventrolateral part of the VNLL (VNLLvl; v). The location of the labelling (i–v) corresponds to the region from which the images in b were taken. Scale bar equals 200 µm. (b) Magnifications of each identified region (i–v) shown as overlay (left column) with the corresponding gray scaled images depicted horizontally. Scale bar equals 20 µm.

VGluT1 labelling supported the identification of the different auditory nuclei in Etruscan shrew, consistent with the expression pattern in other mammals. Therefore, we employed VGluT1 labelling as reference marker for further co-labelling.

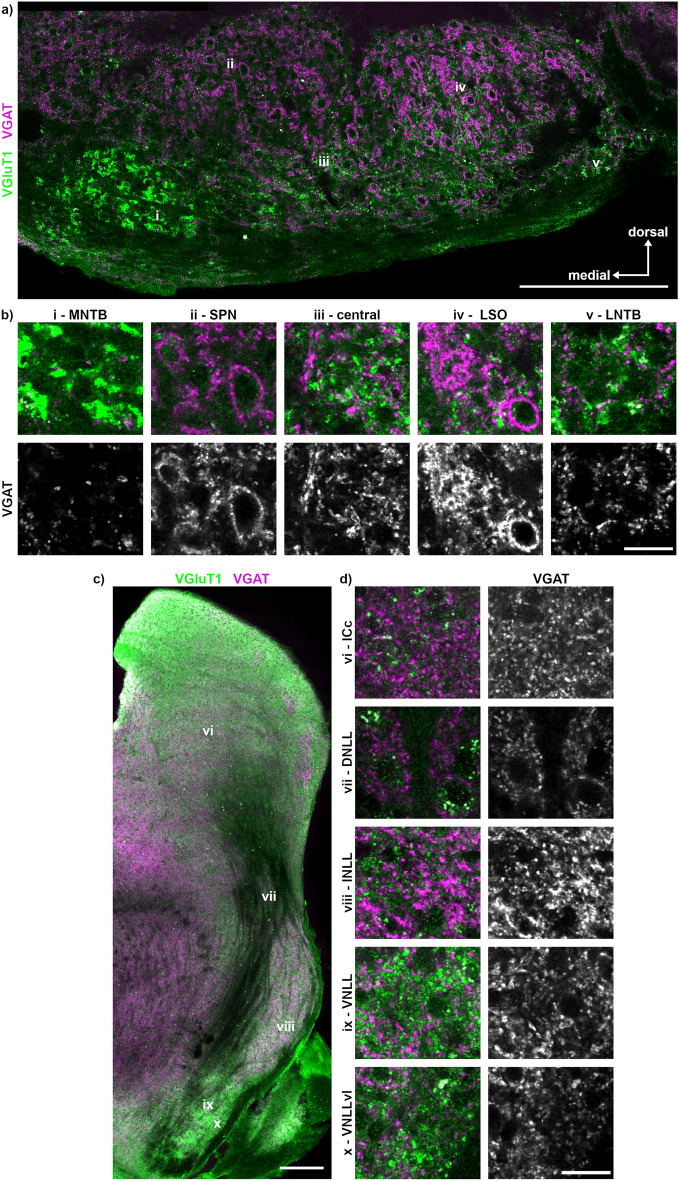

Next to the distribution of excitatory inputs, the distribution of inhibitory synapses was assayed by VGAT labelling (Fig. 5). We used this antibody directed to detect inhibitory synapses in general, because trials with various GlyT2 antibodies were unsuccessful to label specific glycinergic synapse. In the MNTB, the intensity and density of the VGAT labelling was lowest compared to other SOC nuclei (Fig. 5a, b). In the SPN and LSO, VGAT labelling surrounded somata, while in the central region and the LNTB it appeared more disbursed. Throughout the NLL and the IC, VGAT labelling was present and appeared of high intensity in the INLL (Fig. 5c, d).

Figure 5.

Distribution of inhibitory synapses within the SOC, NLL and IC. (a) Overview of the SOC showing the previously identified nuclei (i–v) with VGAT (magenta) and VGluT1 (green) labelling. The location of the labelling (i–v) corresponds to the region from which the images in b were taken. Scale bar equals 200 µm. (b) Magnifications of the different SOC regions (i–v) shown as overlay (top row) with the corresponding gray scaled VGAT images. Scale bar equals 20 µm. (c) Overview of the previously identified nuclei (vi–x) of the NLL and the IC. The location of the labelling (vi–x) corresponds to the region from which the images in d were taken. Scale bar equals 200 µm. (d) Magnifications of the ICc and the NLL (vi–x) shown as overlay (left column) with the corresponding gray scaled VGAT images. Scale bar equals 20 µm.

Distribution of inhibitory neurotransmitters

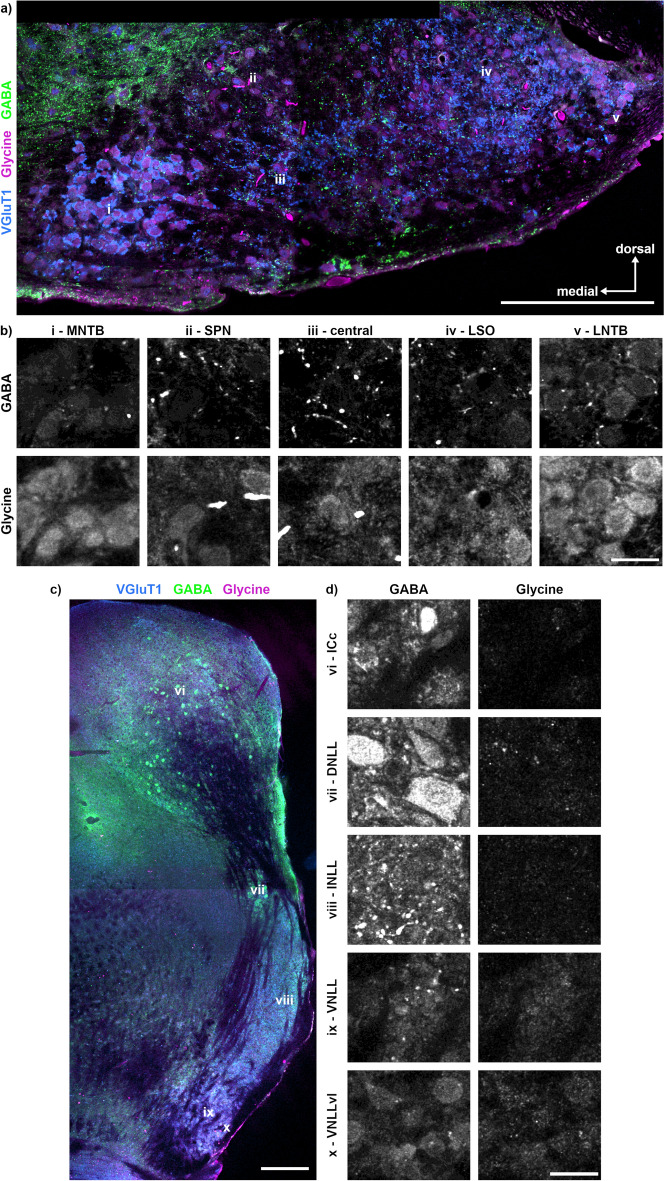

Next to the distribution of synaptic input types, the transmitter content of neurons is an indicator of nucleus identity. Therefore, we labelled sections with antibodies targeted against GABA and glycine (Fig. 6). Glycinergic neurons were found in all SOC nuclei, yet dominating in the MNTB, SPN and LNTB. In the MNTB and LNTB, a partial GABA co-labelling was observed (Fig. 6b). GABA labelling yielded punctate structures in the SPN, central region, LSO and LNTB that might indicate GABAergic synaptic inputs to these neurons. In the NLL and IC, inhibitory neurons were mainly GABAergic with some glycinergic co-labelling in the VNLLvl (Fig. 6c, d). DNLL neurons were clearly GABA-positive (Fig. 6d). In the INLL, no GABAergic somata but punctate structures reminiscence of buttons were observed (Fig. 6d). Overall, we observed a ventrodorsal increase and decrease of GABAergic and glycinergic labelling, respectively, in the NLL. Moreover, the lack of somatic glycine and GABA labelling in various structures indicates antibody specificity.

Figure 6.

Distribution of GABA and glycine within the SOC, NLL and IC. (a) Overview of the previously identified nuclei (i–v) of the SOC with GABA (green), glycine (magenta) and VGluT1 (blue) labelling. The location of the labelling (i–v) corresponds to the region from which the images in b were taken. Scale bar equals 200 µm. (b) Magnifications of the different SOC regions (i–v) for GABA and glycine. Scale bar equals 20 µm. (c) Overview of the previously identified nuclei (vi–x) of the NLL and the IC. The location of the labelling (vi–x) corresponds to the region from which the images in d were taken. Scale bar equals 200 µm. (d) Magnifications of the ICc and the NLL (vi – x) for GABA and glycine. Scale bar equals 20 µm.

Distribution of CaBPs

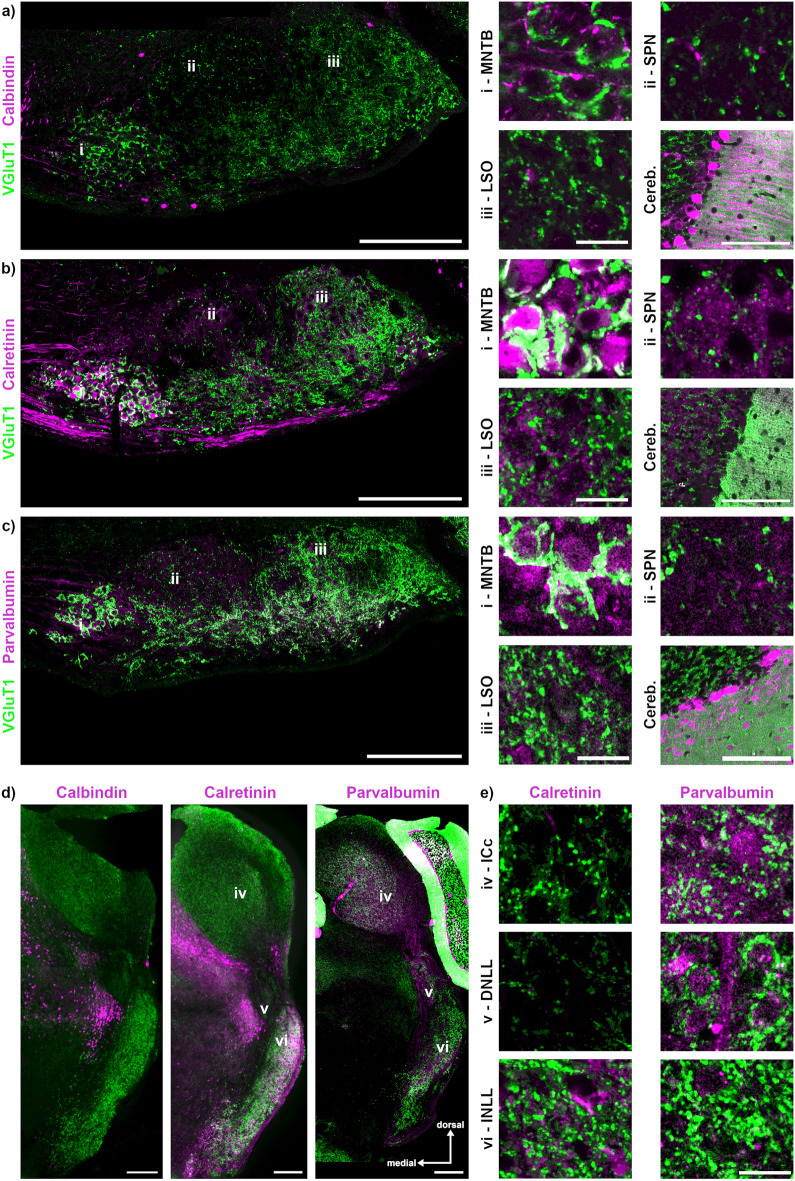

CaBPs influence neuronal signalling43–46. In the auditory brainstem, their differential presence was used to identify nuclei localisation and development47–52 as well as projection patterns53. The expression patterns of CB, CR and PV are species-dependent22,48,49,51,52. Here, we co-labelled CB, CR and PV together with VGluT1 (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Distribution of calcium binding proteins within the SOC, NLL and IC. (a) Left: Overview of SOC labelled with calbindin (CB; magenta) and VGluT1 (green), i–iii mark the nuclei shown as insets on the right. The location of the labelling corresponds to the region from which the images to the right were taken. Right: Magnifications from MNTB (i), SPN (ii), LSO (iii) and cerebellum (Cereb.). Cerebellum image was taken from the same section. Scale bars equal 200 µm (overview), 20 µm (SOC magnifications) and 100 µm (Cereb.). (b) Same as in (a) for calretinin (CR). (c) Same as in (a) for parvalbumin (PV). (d) Overview of sections containing the NLL and IC labelled with CB, CR or PV (magenta) and VGluT1 (green), numbers (iv–vi) alongside the magnified nuclei in e. The location of the labelling corresponds to the region from which the images in e were taken. Scale bars equal 200 µm. (e) Magnifications of the ICc (iv), DNLL (v) and INLL (vi) for CR and PV (magenta) with VGluT1 (green) co-labelling. Scale bar equals 20 µm.

Somatic CB labelling was nearly absent in the SOC (Fig. 7a). Exemplified for the MNTB, SPN and LSO, some labelling of CB occurred in the neuropil (Fig. 7a). However, this supposedly synaptic labelling did not co-localize with VGluT1, indicating a possible inhibitory calbindinergic input. To illustrate that the absence of CB from the SOC is not dependent on the antibody, we used cerebellar labelling as a control. As expected from other species22,54, Purkinje neurons were CB-positive (Fig. 7a). In the SOC, CR-positive somata were restricted to the MNTB and LNTB (Fig. 7b). In some cases, CR labelling co-localized with VGluT1-positive synapses in the MNTB. In the SPN and LSO, CR labelled non-VGluT1-positive, punctate structures in the neuropil (Fig. 7b), suggesting calretinergic inhibition, possibly originating from CR-positive neurons of the MNTB. CR-positive labelling of the neuropil was also detected in the cerebellum (Fig. 7b). PV labelling was weak but distributed similarly to CR labelling in the SOC (Fig. 7c). Some weak pre- and postsynaptic PV labelling was detected in the MNTB and non-VGluT1 co-localizing puncta in the SPN and LSO. To corroborate this finding, our approach yielded strong PV-positive signals in cerebellar Purkinje cells, as has been described for other species54,55.

In the NLL and the IC, CB was not detected by immunofluorescence, yet, it is present in the medial paralemniscal zone (Fig. 7d). Somatic CR labelling was nearly absent in the IC and DNLL, but found in the lateral parts of the INLL and VNLL and the medial paralemniscal zone (Fig. 7d). Sparse neuropil labelling of CR occurred in the ICc and INLL (Fig. 7e). PV labelling appeared present in fibers passing the NLL and the IC (Fig. 7d). Some somata were labelled in the ICc and very weakly in the DNLL (Fig. 7e). Taken together, weak somatic CaBP expression was restricted to the MNTB, LNTB, lateral INLL, DNLL and IC, while it was absent in SPN, central region, LSO, VNLLvl and large parts of VNLL and INLL.

Distribution of HCN1 and Kv1.1 channels

In the Etruscan shrew’s SOC, HCN1-positive labelling was present in the SPN, the central region and especially in the LSO and nearly absent in the MNTB and LNTB (Fig. 8a, b). HCN1 did not co-label with VGluT1 and, together with the labelled structures, we interpret HCN1 location as mainly somatic and dendritic. In the NLL, HCN1-positive labelling was observed in the VNLL, INLL and ICc but not in the VNLLvl and DNLL (Fig. 8c, d). In the ICc, some neurons were positively labelled for HCN1, indicating a heterogeneous expression pattern.

Figure 8.

Distribution of HCN1 within the SOC, NLL and IC. (a) Overview of the previously identified nuclei (i–v) of the SOC with HCN1 (magenta) and VGluT1 (green) labelling. The location of the labelling (i–v) corresponds to the region from which the images in b were taken. Scale bar equals 200 µm. (b) Magnifications of the different SOC regions (i–v) shown as overlay (top row) with the corresponding gray scaled images below. Scale bar equals 20 µm. (c) Overview of the previously identified nuclei (vi–x) of the NLL and the IC. The location of the labelling (vi–x) corresponds to the region from which the images in d were taken. Scale bar equals 200 µm. (d) Magnifications of the ICc and the NLL (vi–x) shown as overlay (left column) with the corresponding gray scaled images to the right. Scale bar equals 20 µm.

In Etruscan shrew, Kv1.1 immunofluorescence was detected throughout the SOC neurons (Fig. 9a) and in the juxta-nodal region of nodes of Ranvier (Fig. 9b). Within each SOC nucleus, Kv1.1 labelling was strong in the somata and weaker in the dendrites and did not overlay with glutamatergic synapses (Fig. 9c). Since the Kv1.1 labelling reliable detects neurons and VGluT1 supports nuclei identification in the SOC, we used this antibody combination in serial sections (n = 2) to highlight the major nuclei and their caudorostral appearance (Fig. 9d). The LSO and LNTB started most caudally and was followed by the SPN, and finally by the MNTB. The MNTB extended most rostrally compared to the other nuclei. In the serial section, the central region did not highlight specific cell populations with distinct organization (Fig. 9d). All neurons in the DNLL appeared intensely labelled (Fig. 9e). In the INLL and VNLL, Kv1.1 labelling was either absent or weaker compared to other LL structures (Fig. 9f). In the VNLLvl and in a subpopulation of ICc neurons, Kv1.1 labelling was detected. Our labelling indicates a predominant post-synaptic localisation of Kv1.1, because of its shape and the nearly absence of co-labelling with VGluT1.

Figure 9.

Distribution of Kv1.1 within the SOC, NLL and IC. (a) Overview of the previously identified nuclei (i–v) of the SOC with Kv1.1 (magenta) and VGluT1 (green) labelling. The location of the labelling (i–v) corresponds to the region from which the images in c were taken. Approximate location of the magnification shown in b is marked with the number vi. Scale bar equals 200 µm. (b) Magnification of nodes of Ranvier (vi) within the fiber bundle ventral to the LNTB (v). Scale bar equals 20 µm. (c) Magnifications of the different SOC regions (i–v) shown as overlay (top row) with the corresponding gray scaled images below. Scale bar equals 20 µm. (d) Serial sections of Kv1.1 and VGluT1 labelled SOC region. Number of the sections is given in the top left corner of the overlay images, every 50 µm is shown. Kv1.1 labelling is also shown below in gray scale. Scale bar equals 200 µm. (e) Overview of the previously identified nuclei (vii – xi) of the NLL and the IC. The location of the labelling (vii–xi) corresponds to the region from which the images in f were taken. Scale bar equals 200 µm. (f) Magnifications of the ICc and the NLL (vii–xi) shown as overlay (left column) with the corresponding gray scaled images to the right. Scale bar equals 20 µm.

To give an estimate about the size of auditory nuclei in the Etruscan shrew, we measured the cross-section area of the MNTB, LSO and DNLL. Extracted from different labellings the size of the MNTB was 0.034 ± 0.001 mm2 (n = 45), from the LSO 0.05 ± 0.001 mm2 (n = 46) and from the DNLL 0.05 ± 0.018 mm2 (n = 34). This compares to about a 3 and fivefold smaller size to the MNTB and LSO of gerbil respectively56.

Discussion

Here, we describe the architecture of the SOC and the LL and therein the expression patterns of marker proteins in the Etruscan shrew summarized in Fig. 10. The combination of immunofluorescently detected protein expression and Nissl staining allows us to identify in the SOC the MNTB, SPN, LSO and LNTB while a MSO and a VNTB could not unambiguously be determined. In the LL, the three major nuclei and their subdivision (DNLL, INLL, VNLL, VNLLvl) were identified. The inhibitory and excitatory presence and distribution of synaptic terminals agrees with that of other mammals (Fig. 10a + b). A peculiarity exists in the apparent low expression level of CaBPs (Fig. 10e + f). All nuclei except the SPN share the known presence of transmitter types (Fig. 10c + d). HCN1 and Kv1.1 expression largely compared to rodents (Fig. 10g + h).

Figure 10.

Schematic summary of the probed expression patterns in the SOC and NLL of the Etruscan shrew. Explanations of the symbols are given on the right. More symbols indicate an apparent higher intensity of labelling and does not necessarily reflect the percentage of labelled somata. (a, b) Distribution of synaptic labelling. (c, d) Distribution of GABA- and glycinergic cells. (e, f) Distribution of CaBPs. (g, h) Distribution of HCN1 and Kv1.1 channels.

Identification and arrangement of auditory nuclei

In the Etruscan shrew, the MNTB and LNTB appear as the major landmarks for the SOC by their densely packed globular cells readily apparent in Nissl staining. The neuronal markers NeuN and MAP2 helped little in further separating the SOC nuclei. Using the pre-synaptic markers VGluT1 and VGAT, the MNTB, SPN, LSO and LNTB could be distinguished. MNTB and LNTB were distinguished by the large somatic VGluT1-positive synapses, e.g.41, SPN by its predominant inhibitory input22 and the LSO by the mixture of VGluT1 and VGAT22,57. Yet again, no subdividing of the central region was feasible. The same difficulty for the central region was given by other markers such as voltage-gated ion channels, CaBPs or transmitters despite an overall heterogeneous appearance. Therefore, we conclude that the SOC in Etruscan shrew is dominated by the MNTB, SPN, LSO and LNTB and that other structures such as the MSO, VNTB and lateral and medial olivocochlear bundle cells are either strongly reduced, merged into a heterogeneous cell population or moved to unexpected positions. Since we were unable to untangle the cell population in the central SOC further, we termed it the central region.

In the LL, a well-stained Nissl region of globular neurons on the ventrolateral side stood out. This sub-region contained large VGluT1 labelled terminals on GABA and glycine co-labelled somata. Therefore, this region resembled the fast relaying cells that receive endbulb synapses20,21. Thus, similar to mice and some bats (Phyllostomus discolor and Carollia perspicillata), this cell population is located ventrolaterally in Etruscan shrew and differs in its location from bats like Eptesicus fuscus, Rhinolophus ferrumequinum or Petronotus parnellii where it is located either more medially, dorsally or ventrally8. Etruscan shrews are separated from rodents by 94 MYA and from bats by about 86 MYA58. Thus, the ancestral location of this cell population might be the ventrolateral position and further rearrangements in some bats might have followed other so far unknown adaptations.

From all three NLL, the DNLL can most easily be distinguished. The DNLL is marked by high intensity GABA and Kv1.1, low intensity VGluT1 labelling and the presence of pre- and partially post-synaptic PV labelling and matches therefore with other mammalians22,59–62. The border between INLL and VNLL is difficult to morphologically delineate19,63. However, the specific transmitter types of these nuclei seem to be the key feature for their separation59,61,64. In Etruscan shrew, we found that next to a difference in transmitter types a more intense VGAT, CaBP and HCN1 labelling in the INLL compared to the VNLL additionally helped to separate these structures.

In conclusion, the Etruscan shrew’s auditory brainstem is overall similar to other mammals, yet with specific differences. First, the MSO could not be unambiguously identified. This is in line with the concept that the small heads of terrestrial mammals are not suited to detect interaural time differences and that this processing task is the key feature of the MSO. Second, the INLL and VNLL could well be separated by a distinct pattern of markers. Each of the several markers indicated slight differences that accumulated into a clear distinction that is supported by the known difference in neurotransmitter content. Third, the arrangement of the VNLLvl follows that of rodents and some bats and therefore likely reflects the ancestral one.

Cellular distribution of inhibitory neurotransmitter

The distribution of cells with GABA- and glycinergic neurotransmitter content appear to largely match that of other mammals59–61,64–68. One difference was the glycinergic and not GABAergic transmitter content of SPN neurons. The SPN is regarded to be GABAergic or mixed GABA/glycinergic for example in rat, guinea pig, gerbil or bat65–68. The glycinergic cell population of the SPN in Etruscan shrew agrees more with macaques, where a similar area of the SOC lacks GAD but contains glycinergic neurons60. Thus, despite being generally inhibitory, this cell population might use different transmitters, irrespectively of head size.

Functional considerations

Labelling of transmitter specific presynaptic structures allows the detection of input patterns of nuclei. VGluT1 and VGAT immunofluorescence thereby discriminates between excitatory and inhibitory inputs. In Etruscan shrew, the gross input patterns in auditory brainstem nuclei are similar to that of other mammals22,41,57,62,69. Thus, we consider the overall circuit architecture of the auditory system conserved in Etruscan shrews.

In the auditory brainstem, the presence of Kv1.1 and HCN1 channels are functionally important. In Etruscan shrew, Kv1.1 channel distribution matches that of other mammals22,33. Interestingly, the expression pattern of Kv1.1 is similar in DNLL and MNTB neurons. In MNTB neurons, Kv1.1 is implicated in supporting onset action potential firing by suppression excitability33. DNLL neurons in rodents have been shown to fire continuously to current injections70,71. Whether in the DNLL ongoing firing behavior is absent in Etruscan shrews or these neurons use Kv1.1 for different purposes is so far not explored and cannot be answered by histology. In the auditory brainstem of Etruscan shrew, HCN1 channels are similarly distributed to gerbils, naked mole rat and mice57,72 but differ from bats where MNTB neurons are HCN1-positive22. The heterogeneous expression of HCN1 in the INLL of Etruscan shrew would suggest that some neurons either generate short integration times or off-set inhibition. Whether this heterogeneity matches the reported heterogeneity of cell morphology19,62,63 is unresolved so far.

Calcium binding proteins are endogenous calcium buffers. The largely soluble CaBPs CB, CR and PV are implicated in shaping calcium signals relevant for synaptic transmission44,45 and dendritic calcium signaling43,46. In fast spiking neurons, CaBPs can be considered to buffer the excess calcium influx generated by action potential sequences. In the auditory brainstem of many mammals, these proteins are highly expressed in agreement with the high firing rates. Thereby, the CaBP expression patterns differ between mammals22,48,49,73. In Etruscan shrew, the low expression or absence of CaBPs is peculiar. This limited presence of CaBPs is expected to influence calcium signaling. For example, synaptic short-term plasticity in auditory circuits might be biased to facilitation in Etruscan shrew rather than depression as in other mammals74. For viability, in Etruscan shrew to restrict intracellular free calcium accumulation either other CaBPs are expressed as buffers, calcium channel densities are lower or extrusion rates are faster compared to other mammals.

Our labelling of different marker and functional proteins enables the differentiation of the main auditory brainstem nuclei in the SOC and LL in the smallest terrestrial mammal and gives insights into their functionality. For the SOC, the main nuclei are the MNTB, SPN, LSO and LNTB. For the LL, the VNLL, VNLLvl, INLL, DNLL and the paralemniscal region are highlighted. We argue that the head size and the peripheral auditory structures are in agreement with ancestral mammalian features. These constrains will hinder sound source location by interaural time differences and thereby allow for a reduction of the MSO in Etruscan shrews. The presence of the MSO in exclusively high frequency listening mammals such as bats can be explained by their suggested differences in circuitry and functionality75. Thus, the Etruscan shrew might serve as system to illuminate the ancestral mammalian auditory brainstem structures relevant for exquisite hunters.

Methods

Experimental animals

In this study, we included 37 between three and 22 months old Etruscan shrews (Suncus etruscus) of both sexes, bred in the institute’s colony. The shrews were housed in terraria containing a layer of dry soil, moss, stones, pieces of wood and small flowerpots. Their diet consisted of field crickets (every second day) and water ad libitum. Light cycle was constant throughout the year with 12 h of light and dark phase each. Ambient temperature was maintained at ~ 26 °C and relative humidity at 26 ± 0.6% (mean ± SEM).

Brain Tissue Preparation

All experiments were in accord with ARRIVE guidelines, the national laws and local regulations and were approved by the animal welfare officer on the local animal protocol TiHo-T-2021–4. Animals were euthanized with CO2 and declared dead after ~ 2 min of breathing arrest. Animals were perfused with Ringer-Heparin solution followed by either 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for Nissl staining or different PFA solutions for immunofluorescence labelling. Dependent on the primary antibody, we used 4% PFA, 3.7% PFA with 0.3% glutaraldehyde or 2% PFA with 15% picric acid in PBS (Table 1). The 2% PFA solution was used as standard, because it conserves more epitopes. Following perfusion, the brains were removed and post-fixed in the matching PFA solution over night at 4 °C.

Table 1.

Primary antibodies.

| Target | Host | Type | Dilution | PFA (%) | Used 2nd AB | Company | RRID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calbindin D-28 k | Mouse | Monoclonal | 1:5000 | 2 | Cy3 | Swant (Cat#300) | AB_10000347 |

| Calretinin | Mouse | Monoclonal | 1:5000 | 2 | Cy3 | Swant (Cat#6B3) | AB_10000320 |

| GABA | Mouse | Monoclonal | 1:5000 | 3.7 | A488, Cy3 | Swant (Cat#3A12) | AB_2721208 |

| Glycine | Rabbit | Polyclonal | 1:1500 | 3.7 | Cy3 | MoBiTec (Cat#1015GE) | AB_2560949 |

| HCN1 | Rabbit | Polyclonal | 1:400 | 2 | Cy3 | Synaptic systems (Cat# 338 003) | AB_2620083 |

| Kv1.1 | Rabbit | Polyclonal | 1:2500 | 2 | A488, Cy3 | Alomone labs (Cat# APC-009) | AB_2040144 |

| MAP2 | Chicken | Polyclonal | 1:3000 | 2 | AMCA, A488 | Neuromics (Cat# CH22103) | AB_2314763 |

| NeuN (D4G4O) XP | Rabbit | Monoclonal | 1:400 | 2 | Cy3 | Cell Signaling technology (Cat# 24307) | AB_2651140 |

| Parvalbumin | Mouse | Monoclonal | 1:5000 | 4 | A488, Cy3 | Swant (Cat# 235) | AB_10000343 |

| VGAT | Guinea pig | Monoclonal | 1:8000 | 2 | A488, Cy3 | Synaptic systems (Cat# 131 308) | AB_2832243 |

| VGluT1 | Guinea pig | Polyclonal | 1:2000 | 2, 3.7, 4 | A488, A647, Cy3 | Synaptic systems (Cat# 135 304) | AB_887878 |

| VGluT1 | Mouse | Monoclonal | 1:1000 | 2 | A488, A647 | Synaptic systems (Cat# 135 311) | AB_887880 |

For biocytin labelling, animals were deeply anesthetised with isoflurane before decapitation. After brain removal, a small biocytin crystal (B4261, Sigma-Aldrich) was pushed onto the cochlear nucleus. The brains containing biocytin were incubated for 3 h in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (125 mM NaCl, 25 mM NaHCO3, 2.5 mM KCl, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 1 mM MgCl2, 1.2 mM CaCl2, 25 mM glucose, 0.4 mM ascorbic acid, 3 mM myo-inositol and 2 mM Na-pyruvate, pH 7.4), saturated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 at 33–35 °C. Brains were fixed in 2% PFA with 15% picric acid in PBS over night at 4 °C. For immunofluorescence co-labelling, tissue was embedded in 4% agar in deionized water and 50 µm transversal sections were cut with a vibratome (7000smz-2, Campden) at room temperature.

For the Nissl staining, transversal sections were cut with a cryostat (HM 500 OM, Microm) after cryoprotection in 15% and 30% sucrose dissolved in PBS at 4 °C each at least for 24 h. As tissue freezing medium, a solution of 2% gelatine in deionized water was used. The slicing temperature was set to −20 °C and the section thickness to 30 µm.

Nissl staining and immunofluorescence labelling

Nissl staining (n = 4) was carried out with a standard protocol with on slides mounted sections using incubation times of 22 min in the cresyl violet staining solution. For free-floating immunofluorescence (n = 33), an aldehyde-reduction protocol for background reduction was used. After three PBS washes, the sections were incubated on ice in NaBH4 (1 g/l) dissolved in PBS four times each 10 min as aldehyde reduction step. After washing three times in PBS, sections were blocked for 30 min in blocking solution containing 0.5% triton v/v, 1% bovine serum albumin w/v and 0.1% saponin w/v in PBS. Sections were incubated in blocking solution containing primary antibodies (Table 1) for 72 h at 4 °C. Before incubation with the respective secondary antibodies (s. Table 2), sections were washed in washing solution (0.5% triton v/v and 0.1% saponin w/v in PBS) three times for 10 min. The secondary antibodies were diluted in blocking solution and incubated for 4 h at room temperature. Afterwards, the sections were washed with washing solution (three times 10 min) and transferred to PBS, before mounting on gelatinized slides with Vectra shield and sealed with nail polish. To fix GABA and glycine more effective, a PFA solution with glutaraldehyde was used, since this binds stronger to amino groups. For the PV labelling, the PFA solution was switched to 4% according to the literature 76. The following amounts of sections from at least three animals with the age range given in Table 3 were used for each antibody combination: biocytin + VGluT1 n = 16/9 (SOC/NLL); MAP2 + NeuN + VGluT1 n = 32/16; VGAT + VGluT1 n = 32/16; GABA + glycine + VGluT1 n = 20/14; CB + VGluT1 n = 18/10; CR + VGluT1 n = 18/10; PV + VGluT1 n = 40/20; HCN1 + VGluT1 n = 14/6; Kv1.1 + VGluT1 n = 42/21.

Table 2.

Secondary antibodies.

| Antigen | Conjugate | Host | Dilution | Company | Catalogue number | RRID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chicken | Alexa488 | Donkey | 1:300 | Dianova | 703-546-155 | AB_2340376 |

| Guinea pig | Alexa488 | Donkey | 1:800 | Dianova | 706-546-148 | AB_2340473 |

| Mouse | Alexa488 | Donkey | 1:200 | Dianova | 715-545-150 | AB_2340846 |

| Rabbit | Alexa488 | Donkey | 1:800 | Dianova | 711-545-152 | AB_2313584 |

| Guinea pig | Alexa647 | Donkey | 1:200 | Dianova | 706-606-148 | AB_2340477 |

| Mouse | Alexa647 | Donkey | 1:200 | Dianova | 715-606-150 | AB_2340865 |

| Chicken | AMCA | Donkey | 1:100 | Dianova | 703-156-155 | AB_2340362 |

| Biotin | Cy3 | Streptomyces avidinii | 1:500 | Dianova | 016-160-084 | AB_2337244 |

| Guinea pig | Cy3 | Donkey | 1:800 | Dianova | 706-165-148 | AB_2340460 |

| Mouse | Cy3 | Donkey | 1:200 | Dianova | 715-165-151 | AB_2315777 |

| Rabbit | Cy3 | Donkey | 1:800 | Dianova | 711-165-152 | AB_2307443 |

Table 3.

Animal age used in the different labelling.

| Labelling | # of animals | Age range [months] | Age average [months] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nissl | 4 | 3–22 | 10.25 |

| MAP2 + NeuN | 4 | 7–14 | 10.5 |

| Biocytin | 3 | 11–18 | 14.33 |

| VGAT | 3 | 8–21 | 14.33 |

| GABA + Gly | 3 | 3–6 | 4.33 |

| CB | 5 | 5–10 | 8.8 |

| CR | 5 | 5–10 | 8.8 |

| PV | 4 | 7–18 | 13.25 |

| HCN1 | 3 | 6–19 | 11.67 |

| Kv1.1 | 5 | 9–18 | 12.8 |

| VGluT2 | 3 | 7–14 | 11.33 |

Antibody characterisation

The reactivity of most primary antibodies has not be tested in the Etruscan shrew so far, apart from a description of CB77,78 and PV76. The following description of labelling feasibility and specificity shows that the used antibodies have been successfully applied in brain sections of other species.

Within the auditory brainstem, anti-CB labels somata and neuropil in geckos79, gerbils53 and bats22. The anti-CB antibody was purified from chicken gut80. It was tested for specificity in various mammals by western blot and by knock-out mice (company description). In the Etruscan shrew, this antibody was successfully used in the hippocampus and cortex77,78.

The anti-CR antibody was produced against recombinant human calretinin-22 k in mice. It was tested for specificity in various animals via Western Blot and knock-out mice (company description). This anti-CR antibody labels neuronal structures in cat81, human82 and bat22.

The anti-GABA antibody was purified in mice and verified by ELISA83. In the auditory brainstem, this GABA antibody labels somata and neuropil in frogs84, chicken85,86 and gerbil62.

The anti-glycine antibody was raised in rabbit with conjugates of glycine-glutaraldehyde-carriers and verified by ELISA87. It has been successfully used in fish88 and labelled specifically somata of glycinergic neurons in the auditory brainstem of guinea pig89 and gerbil62.

The anti-HCN1 antibody was produced in rabbit against rat recombinant HCN1 (company description). Its reactivity was tested in rats and mice (company description) and labelled neuronal somata in bat22.

The anti-Kv1.1 antibody was raised against mouse KCNA1 (company description). It was verified by a knock-out mouse90 and by western blots (company description). In the auditory brainstem of bats, Kv1.1 labels somata, neuropil, and highlights nodes of Ranvier22,35.

The anti-MAP2 antibody was produced in chicken against the human recombinant protein and its reactivity was tested against humans, primates, mice and rats (company description). It labels neuronal somata and dendrites in neurons e.g., of gerbil53,62 and bat35.

The anti-NeuN antibody was raised against recombinant NeuN in rabbit and tested for reactivity in humans, mice and rats (company description). It is specifically expressed in the soma and cell nucleus of most neuronal cells of the brain91.

The anti-PV antibody was produced in mouse, tested for various species and applications (company description) as well as verified by knock-out92. It labels specifically neuronal structures in gecko79, rat93, bats22, hedgehogs94 and Etruscan shrews76.

The anti-VGAT antibody was purified against rat recombinant VGAT and was verified by knock-out (company description). It labels specifically inhibitory – namely GABAergic and glycinergic–synapses in at least mouse, rat and gerbil62,95,96.

The anti-VGluT1 antibody was produced in guinea pig against recombinant VGluT1 of rat, near the carboxy terminus (company description). It is verified by knock-out97 to label glutamatergic synapses in bat22, guinea pigs98 and gerbil99.

A second anti-VGluT1 antibody was raised in mice against the same locus than the latter and was also verified by knock-out (company description). It labels the glutamatergic synapses in the auditory brainstem at least in guinea pig and gerbil62,100.

Image Acquisition and data analysis

The Nissl sections were photographed on a Light Therapy Lamp (model TT-CL011, Taotronics) using a Canon EOS 60D camera with an EFS 18–55 objective on retro modus with an exposure time of 5 ms. Post-hoc, the pictures were cut to the same size and the background was unified with FastStone Image Viewer.

Fluorescence was imaged using inverted confocal microscopes (TCS SP5, Leica, and TCS SP8, Leica) excited with a 405 nm, an argon, a 561 nm and a 633 nm laser to detect AMCA, Alexa 488, Cy3 and Alexa 647 at emission filtered wavelengths of 420–470 nm, 495–540 nm, 565–585 nm and 653–695 nm, respectively. As objective, a 10 × dry/ NA 0.40, a 20 × oil/ NA 0.75, a 40 × oil/ NA 1.25 or a 63 × oil/ NA 1.40 was used. The laser intensity and detection gain was constant for all images taken from a given section. The fluorescent images were acquired in monochrome and colour maps were applied to the images post-acquisition. Post-hoc, linear brightness and contrast adjustment were applied uniformly to the images with Fiji. Colour channels were post-hoc combined before merging the tile images using the Fiji stitching plugin101.

Cross-section areas of the MNTB, LSO and DNLL were determined by encircling the nuclei identified by VGluT1 labelling in Fiji with the free hand section tool. The nucleus sizes were measured from their ROIs and averaged over different sections of different labelling combinations from different animals.

Acknowledgements

We like to thank Alexandra Benn for technical support with the immunofluorescence labelling, Sönke von den Berg for providing the camera set-up for Nissl photography and a Fiji macro as well as Tjard Bergmann for coding R routines. We thank Dr. Christina Pätz-Warncke for comments on the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- CaBP

Calcium binding protein

- CB

Calbindin

- Cereb

Cerebellum

- CN

Cochlear nucleus

- CR

Calretinin

- DNLL

Dorsal nucleus of the lateral lemniscus

- GABA

γ-Aminobutyric acid

- HCN1

Potassium/sodium hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated channel 1

- IC

Inferior colliculus

- ICc

Central nucleus of the inferior colliculus,

- INLL

Intermediate nucleus of the lateral lemniscus,

- Kv1.1

Potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily A member 1

- LL

Lateral lemniscus

- LNTB

Lateral nucleus of the trapezoid body

- LSO

Lateral superior olive

- MAP2

Microtubule-associated protein 2

- MNTB

Medial nucleus of the trapezoid body

- MSO

Medial superior olive

- NeuN

Neuronal nuclear antigen

- NLL

Nuclei of the lateral lemniscus

- PBS

Phosphate-buffered saline

- PFA

Paraformaldehyde

- PV

Parvalbumin

- SOC

Superior olivary complex,

- SPN

Superior paraolivary nucleus

- VGAT

Vesicular γ-aminobutyric acid transporter,

- VGluT1

Vesicular glutamate transporter type 1

- VNLL

Ventral nucleus of the lateral lemniscus

- VNLLvl

Ventrolateral part of the ventral nucleus of the lateral lemniscus

Author contributions

AC.Z.: data acquisition, analysis, writing; F.F.: study design and concept, data analysis, writing.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This work was supported by the University of Veterinary Medicine Foundation Hannover.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Spitzberger, F. Suncus etruscus (Savi, 1822) - Etruskerspitzmaus, in Handbuch der Säugetiere Europas-Insektenfresser-Insectivora. Herrentiere, Vol. 3. 523 (eds Krapp F. & Niethammer J), (Aula - Verlag, 1990).

- 2.Vogel P. Biologische beobachtungen an etruskerspitzmäusen. Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde. 1969;35:173–185. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brecht M, et al. The neurobiology of Etruscan shrew active touch. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2011;366:3026–3036. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anjum F, Turni H, Mulder PG, van der Burg J, Brecht M. Tactile guidance of prey capture in Etruscan shrews. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:16544–16549. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605573103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunt RM, Jr, Korth WW. The auditory region of dermoptera: Morphology and function relative to other living mammals. J. Morphol. 1980;164:167–211. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1051640206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grothe B, Pecka M. The natural history of sound localization in mammals—A story of neuronal inhibition. Front. Neural Circuits. 2014;8:116. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2014.00116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nothwang HG. Evolution of mammalian sound localization circuits: A developmental perspective. Prog. Neurobiol. 2016;141:1–24. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2016.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Covey E. Neurobiological specializations in echolocating bats. Anat. Rec. Part A Discov. Mol. Cell. Evol. Biol. 2005;287:1103–1116. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.20254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kapfer C, Seidl AH, Schweizer H, Grothe B. Experience-dependent refinement of inhibitory inputs to auditory coincidence-detector neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 2002;5:247–253. doi: 10.1038/nn810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burchell A, Mansour Y, Kulesza R. Leveling up: A long-range olivary projection to the medial geniculate without collaterals to the central nucleus of the inferior colliculus in rats. Exp. Brain. Res. 2022;240:3217–3235. doi: 10.1007/s00221-022-06489-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Albrecht O, Dondzillo A, Mayer F, Thompson JA, Klug A. Inhibitory projections from the ventral nucleus of the trapezoid body to the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body in the mouse. Front. Neural Circuits. 2014;8:83. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2014.00083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuwabara N, Zook JM. Projections to the medial superior olive from the medial and lateral nuclei of the trapezoid body in rodents and bats. J. Comp. Neurol. 1992;324:522–538. doi: 10.1002/cne.903240406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nordeen KW, Killackey HP, Kitzes LM. Ascending auditory projections to the inferior colliculus in the adult gerbil Meriones unguiculatus. J. Comp. Neurol. 1983;214:131–143. doi: 10.1002/cne.902140203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schofield BR, Cant NB. Organization of the superior olivary complex in the guinea pig: II. Patterns of projection from the periolivary nuclei to the inferior colliculus. J. Comp. Neurol. 1992;317:438–455. doi: 10.1002/cne.903170409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Felix RA, 2nd, Fridberger A, Leijon S, Berrebi AS, Magnusson AK. Sound rhythms are encoded by postinhibitory rebound spiking in the superior paraolivary nucleus. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:12566–12578. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2450-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kopp-Scheinpflug C, et al. The sound of silence: Ionic mechanisms encoding sound termination. Neuron. 2011;71:911–925. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kulesza RJ, Jr, Kadner A, Berrebi AS. Distinct roles for glycine and GABA in shaping the response properties of neurons in the superior paraolivary nucleus of the rat. J. Neurophysiol. 2007;97:1610–1620. doi: 10.1152/jn.00613.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glendenning KK, Brunso-Bechtold JK, Thompson GC, Masterton RB. Ascending auditory afferents to the nuclei of the lateral lemniscus. J. Comp. Neurol. 1981;197:673–703. doi: 10.1002/cne.901970409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schweizer H. The connections of the inferior colliculus and the organization of the brainstem auditory system in the greater horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus ferrumequinum) J Comp Neurol. 1981;201:25–49. doi: 10.1002/cne.902010104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adams JC. Projections from octopus cells of the posteroventral cochlear nucleus to the ventral nucleus of the lateral lemniscus in cat and human. Audit. Neurosci. 1997;3:335–350. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berger C, Meyer EM, Ammer JJ, Felmy F. Large somatic synapses on neurons in the ventral lateral lemniscus work in pairs. J. Neurosci. 2014;34:3237–3246. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3664-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pätz C, Console-Meyer L, Felmy F. Structural arrangement of auditory brainstem nuclei in the bats phyllostomus discolor and carollia perspicillata. J. Comp. Neurol. 2022;530:2762–2781. doi: 10.1002/cne.25355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moore LA, Trussell LO. Corelease of inhibitory neurotransmitters in the mouse auditory midbrain. J. Neurosci. 2017;37:9453–9464. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1125-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spencer MJ, et al. Broadband onset inhibition can suppress spectral splatter in the auditory brainstem. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0126500. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Portfors CV, Wenstrup JJ. Responses to combinations of tones in the nuclei of the lateral lemniscus. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2001;2:104–117. doi: 10.1007/s101620010057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ito M, van Adel B, Kelly JB. Sound localization after transection of the commissure of probst in the albino rat. J. Neurophysiol. 1996;76:3493–3502. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.5.3493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meffin H, Grothe B. Selective filtering to spurious localization cues in the mammalian auditory brainstem. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2009;126:2437–2454. doi: 10.1121/1.3238239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pecka M, et al. Inhibiting the inhibition: A neuronal network for sound localization in reverberant environments. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:1782–1790. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5335-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caicedo A, Herbert H. Topography of descending projections from the inferior colliculus to auditory brainstem nuclei in the rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 1993;328:377–392. doi: 10.1002/cne.903280305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gomez-Martinez M, Rincon H, Gomez-Alvarez M, Gomez-Nieto R, Saldana E. The nuclei of the lateral lemniscus: unexpected players in the descending auditory pathway. Front. Neuroanat. 2023;17:1242245. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2023.1242245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borst JG, Helmchen F, Sakmann B. Pre- and postsynaptic whole-cell recordings in the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body of the rat. J. Physiol. 1995;489(Pt 3):825–840. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin KH, Oleskevich S, Taschenberger H. Presynaptic Ca2+ influx and vesicle exocytosis at the mouse endbulb of Held: A comparison of two auditory nerve terminals. J. Physiol. 2011;589:4301–4320. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.209189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dodson PD, Barker MC, Forsythe ID. Two heteromeric Kv1 potassium channels differentially regulate action potential firing. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:6953–6961. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-16-06953.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gittelman JX, Tempel BL. Kv1.1-containing channels are critical for temporal precision during spike initiation. J. Neurophysiol. 2006;96:1203–1214. doi: 10.1152/jn.00092.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kladisios N, Wicke KD, Patz-Warncke C, Felmy F. Species-specific adaptation for ongoing high-frequency action potential generation in MNTB neurons. J. Neurosci. 2023;43:2714–2729. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2320-22.2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khurana S, et al. An essential role for modulation of hyperpolarization-activated current in the development of binaural temporal precision. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:2814–2823. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3882-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koch U, Grothe B. Hyperpolarization-activated current (Ih) in the inferior colliculus: Distribution and contribution to temporal processing. J. Neurophysiol. 2003;90:3679–3687. doi: 10.1152/jn.00375.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ford MC, et al. Tuning of ranvier node and internode properties in myelinated axons to adjust action potential timing. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8073. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moore S, et al. A role of oligodendrocytes in information processing. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:5497. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19152-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sinclair JL, et al. Sound-evoked activity influences myelination of brainstem axons in the trapezoid body. J. Neurosci. 2017;37:8239–8255. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3728-16.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blaesse P, Ehrhardt S, Friauf E, Nothwang HG. Developmental pattern of three vesicular glutamate transporters in the rat superior olivary complex. Cell Tissue Res. 2005;320:33–50. doi: 10.1007/s00441-004-1054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cant NB, Benson CG. Parallel auditory pathways: Projection patterns of the different neuronal populations in the dorsal and ventral cochlear nuclei. Brain Res. Bull. 2003;60:457–474. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(03)00050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barski JJ, et al. Calbindin in cerebellar purkinje cells is a critical determinant of the precision of motor coordination. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:3469–3477. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03469.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Caillard O, et al. Role of the calcium-binding protein parvalbumin in short-term synaptic plasticity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:13372–13377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.230362997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Muller M, Felmy F, Schwaller B, Schneggenburger R. Parvalbumin is a mobile presynaptic Ca2+ buffer in the calyx of held that accelerates the decay of Ca2+ and short-term facilitation. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:2261–2271. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5582-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schmidt H, Stiefel KM, Racay P, Schwaller B, Eilers J. Mutational analysis of dendritic Ca2+ kinetics in rodent purkinje cells: Role of parvalbumin and calbindin D28k. J. Physiol. 2003;551:13–32. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.035824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bazwinsky I, Bidmon HJ, Zilles K, Hilbig H. Characterization of the rhesus monkey superior olivary complex by calcium binding proteins and synaptophysin. J. Anat. 2005;207:745–761. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2005.00491.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Caicedo A, d'Aldin C, Puel JL, Eybalin M. Distribution of calcium-binding protein immunoreactivities in the guinea pig auditory brainstem. Anat. Embryol. (Berl.) 1996;194:465–487. doi: 10.1007/BF00185994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Felmy F, Schneggenburger R. Developmental expression of the Ca2+-binding proteins calretinin and parvalbumin at the calyx of held of rats and mice. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2004;20:1473–1482. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lohmann C, Friauf E. Distribution of the calcium-binding proteins parvalbumin and calretinin in the auditory brainstem of adult and developing rats. J. Comp. Neurol. 1996;367:90–109. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960325)367:1<90::AID-CNE7>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vater M, Braun K. Parvalbumin, calbindin D-28k, and calretinin immunoreactivity in the ascending auditory pathway of horseshoe bats. J. Comp. Neurol. 1994;341:534–558. doi: 10.1002/cne.903410409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zettel ML, Carr CE, O'Neill WE. Calbindin-like immunoreactivity in the central auditory system of the mustached bat Pteronotus parnelli. J. Comp. Neurol. 1991;313:1–16. doi: 10.1002/cne.903130102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Couchman K, Grothe B, Felmy F. Medial superior olivary neurons receive surprisingly few excitatory and inhibitory inputs with balanced strength and short-term dynamics. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:17111–17121. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1760-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bastianelli E. Distribution of calcium-binding proteins in the cerebellum. Cerebellum. 2003;2:242–262. doi: 10.1080/14734220310022289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tolosa de Talamoni N, et al. Immunocytochemical localization of the plasma membrane calcium pump, calbindin-D28k, and parvalbumin in purkinje cells of avian and mammalian cerebellum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:11949–11953. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zacher AC, Hohaus K, Felmy F, Patz-Warncke C. Developmental profile of microglia distribution in nuclei of the superior olivary complex. J. Comp. Neurol. 2023 doi: 10.1002/cne.25547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gessele N, Garcia-Pino E, Omerbasic D, Park TJ, Koch U. Structural changes and lack of hcn1 channels in the binaural auditory brainstem of the naked mole-rat (Heterocephalus glaber) PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0146428. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kumar S, et al. TimeTree 5: An expanded resource for species divergence times. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2022 doi: 10.1093/molbev/msac174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ito T, Bishop DC, Oliver DL. Expression of glutamate and inhibitory amino acid vesicular transporters in the rodent auditory brainstem. J. Comp. Neurol. 2011;519:316–340. doi: 10.1002/cne.22521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ito T, Inoue K, Takada M. Distribution of glutamatergic, GABAergic, and glycinergic neurons in the auditory pathways of macaque monkeys. Neuroscience. 2015;310:128–151. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Saint Marie RL, Shneiderman A, Stanforth DA. Patterns of gamma-aminobutyric acid and glycine immunoreactivities reflect structural and functional differences of the cat lateral lemniscal nuclei. J. Comp. Neurol. 1997;389:264–276. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19971215)389:2<264::AID-CNE6>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wicke KD, Oppe L, Geese C, Sternberg AK, Felmy F. Neuronal morphology and synaptic input patterns of neurons in the intermediate nucleus of the lateral lemniscus of gerbils. Sci. Rep. 2023;13:14182. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-41180-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mylius J, Brosch M, Scheich H, Budinger E. Subcortical auditory structures in the mongolian gerbil: I golgi architecture. J. Comp. Neurol. 2013;521:1289–1321. doi: 10.1002/cne.23232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vater M, Kossl M, Horn AK. GAD- and GABA-immunoreactivity in the ascending auditory pathway of horseshoe and mustached bats. J. Comp. Neurol. 1992;325:183–206. doi: 10.1002/cne.903250205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gonzalez-Hernandez T, Mantolan-Sarmiento B, Gonzalez-Gonzalez B, Perez-Gonzalez H. Sources of GABAergic input to the inferior colliculus of the rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 1996;372:309–326. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960819)372:2<309::AID-CNE11>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Helfert RH, Bonneau JM, Wenthold RJ, Altschuler RA. GABA and glycine immunoreactivity in the guinea pig superior olivary complex. Brain Res. 1989;501:269–286. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90644-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kulesza RJ, Jr, Berrebi AS. Superior paraolivary nucleus of the rat is a GABAergic nucleus. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2000;1:255–269. doi: 10.1007/s101620010054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Roberts RC, Ribak CE. GABAergic neurons and axon terminals in the brainstem auditory nuclei of the gerbil. J. Comp. Neurol. 1987;258:267–280. doi: 10.1002/cne.902580207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ebbers L, Weber M, Nothwang HG. Activity-dependent formation of a vesicular inhibitory amino acid transporter gradient in the superior olivary complex of NMRI mice. BMC Neurosci. 2017;18:75. doi: 10.1186/s12868-017-0393-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ammer JJ, Grothe B, Felmy F. Late postnatal development of intrinsic and synaptic properties promotes fast and precise signaling in the dorsal nucleus of the lateral lemniscus. J. Neurophysiol. 2012;107:1172–1185. doi: 10.1152/jn.00585.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wu SH, Kelly JB. In vitro brain slice studies of the rat’s dorsal nucleus of the lateral lemniscus. II. Physiological properties of biocytin-labeled neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 1995;73:794–809. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.2.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Koch U, Braun M, Kapfer C, Grothe B. Distribution of HCN1 and HCN2 in rat auditory brainstem nuclei. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2004;20:79–91. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816X.2004.03456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bazwinsky-Wutschke I, Hartig W, Kretzschmar R, Rubsamen R. Differential morphology of the superior olivary complex of Meriones unguiculatus and Monodelphis domestica revealed by calcium-binding proteins. Brain Struct. Funct. 2016;221:4505–4523. doi: 10.1007/s00429-015-1181-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Friauf E, Fischer AU, Fuhr MF. Synaptic plasticity in the auditory system: A review. Cell Tissue Res. 2015;361:177–213. doi: 10.1007/s00441-015-2176-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Grothe B, Park TJ. Structure and function of the bat superior olivary complex. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2000;51:382–402. doi: 10.1002/1097-0029(20001115)51:4<382::AID-JEMT7>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ray S, et al. Seasonal plasticity in the adult somatosensory cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:32136–32144. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1922888117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Beed P, et al. Species-specific differences in synaptic transmission and plasticity. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:16557. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-73547-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Naumann RK, et al. Conserved size and periodicity of pyramidal patches in layer 2 of medial/caudal entorhinal cortex. J. Comp. Neurol. 2016;524:783–806. doi: 10.1002/cne.23865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yan K, Tang YZ, Carr CE. Calcium-binding protein immunoreactivity characterizes the auditory system of gekko gecko. J. Comp. Neurol. 2010;518:3409–3426. doi: 10.1002/cne.22428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Celio MR, et al. Monoclonal antibodies directed against the calcium binding protein calbindin D-28k. Cell Calcium. 1990;11:599–602. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(90)90014-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Calvo PM, de la Cruz RR, Pastor AM, Alvarez FJ. Preservation of KCC2 expression in axotomized abducens motoneurons and its enhancement by VEGF. Brain Struct. Funct. 2023;228:967–984. doi: 10.1007/s00429-023-02635-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Arasaratnam CJ, et al. DARPP-32 cells and neuropil define striosomal system and isolated matrix cells in human striatum. J. Comp. Neurol. 2023;531:888–920. doi: 10.1002/cne.25473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Matute C, Streit P. Monoclonal antibodies demonstrating GABA-like immunoreactivity. Histochemistry. 1986;86:147–157. doi: 10.1007/BF00493380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Endepols H, Walkowiak W, Luksch H. Chemoarchitecture of the anuran auditory midbrain. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 2000;33:179–198. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(00)00029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Coleman WL, Fischl MJ, Weimann SR, Burger RM. GABAergic and glycinergic inhibition modulate monaural auditory response properties in the avian superior olivary nucleus. J. Neurophysiol. 2011;105:2405–2420. doi: 10.1152/jn.01088.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kuo SP, Bradley LA, Trussell LO. Heterogeneous kinetics and pharmacology of synaptic inhibition in the chick auditory brainstem. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:9625–9634. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0103-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Campistron G, Buijs RM, Geffard M. Glycine neurons in the brain and spinal cord. Antibody production and immunocytochemical localization. Brain Res. 1986;376:400–405. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90208-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rosner E, Rohmann KN, Bass AH, Chagnaud BP. Inhibitory and modulatory inputs to the vocal central pattern generator of a teleost fish. J. Comp. Neurol. 2018;526:1368–1388. doi: 10.1002/cne.24411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Peyret D, Campistron G, Geffard M, Aran JM. Glycine immunoreactivity in the brainstem auditory and vestibular nuclei of the guinea pig. Acta Otolaryngol. 1987;104:71–76. doi: 10.3109/00016488709109049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhou L, Zhang CL, Messing A, Chiu SY. Temperature-sensitive neuromuscular transmission in Kv1.1 null mice: Role of potassium channels under the myelin sheath in young nerves. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:7200–7215. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-18-07200.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mullen RJ, Buck CR, Smith AM. NeuN, a neuronal specific nuclear protein in vertebrates. Development. 1992;116:201–211. doi: 10.1242/dev.116.1.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Schwaller B, et al. Prolonged contraction-relaxation cycle of fast-twitch muscles in parvalbumin knockout mice. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;276:C395–403. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.276.2.C395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hartig W, et al. Perineuronal nets in the rat medial nucleus of the trapezoid body surround neurons immunoreactive for various amino acids, calcium-binding proteins and the potassium channel subunit Kv3.1b. Brain Res. 2001;899:123–133. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02211-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Roda E, Bottone MG, Insolia V, Barni S, Bernocchi G. Changes in the cerebellar cytoarchitecture of hibernating hedgehog Erinaceus europaeus L. (Mammalia): An immunocytochemical approach. Eur. Zool. J. 2017;84:496–511. doi: 10.1080/24750263.2017.1380722. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Campbell BFN, Dittmann A, Dreier B, Pluckthun A, Tyagarajan SK. A DARPin-based molecular toolset to probe gephyrin and inhibitory synapse biology. Elife. 2022;11:e80895. doi: 10.7554/eLife.80895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kuhse J, et al. Loss of extrasynaptic inhibitory glycine receptors in the hippocampus of an AD mouse model is restored by treatment with artesunate. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023;24:4623. doi: 10.3390/ijms24054623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Souter EA, et al. Disruption of VGLUT1 in cholinergic medial habenula projections increases nicotine self-administration. eNeuro. 2022;9:0481–1421. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0481-21.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Olthof BMJ, Gartside SE, Rees A. Puncta of neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) mediate NMDA receptor signaling in the auditory midbrain. J. Neurosci. 2019;39:876–887. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1918-18.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Callan AR, Hess M, Felmy F, Leibold C. Arrangement of excitatory synaptic inputs on dendrites of the medial superior olive. J. Neurosci. 2021;41:269–283. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1055-20.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Chen M, Min S, Zhang C, Hu X, Li S. Using extracochlear multichannel electrical stimulation to relieve tinnitus and reverse tinnitus-related auditory-somatosensory plasticity in the cochlear nucleus. Neuromodulation. 2022;25:1338–1350. doi: 10.1111/ner.13506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Preibisch S, Saalfeld S, Tomancak P. Globally optimal stitching of tiled 3D microscopic image acquisitions. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1463–1465. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.