Abstract

Avian influenza, particularly the H9N2 subtype, presents significant challenges to poultry health, underscoring the need for effective antiviral interventions. This study explores the antiviral capabilities of Belamcanda extract, a traditional Chinese medicinal herb, against H9N2 Avian influenza virus (AIV) in specific pathogen-free (SPF) chicks. Through a comprehensive approach, we evaluated the impact of the extract on cytokine modulation and crucial immunological signaling pathways, essential for understanding the host-virus interaction. Our findings demonstrate that Belamcanda extract significantly modulates the expression of key inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1 (IL-1), interleukin-2 (IL-2), and interleukin-6 (IL-6), which are pivotal to the host's response to H9N2 AIV infection. Western blot analysis further revealed that the extract markedly reduces the expression of critical immune signaling molecules such as toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3), TIR-domain-containing adapter-inducing interferon-β (TRIF), and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB). These insights into the mechanisms by which Belamcanda extract influences host immune responses and hinders viral replication highlight its potential as an innovative antiviral agent for poultry health management. The study advances our comprehension of natural compounds' antiviral mechanisms and lays the groundwork for developing strategies to manage viral infections in poultry. The demonstrated ability of Belamcanda extract to modulate immune responses and inhibit viral replication establishes it as a promising candidate for future antiviral therapy development, especially in light of the need for effective treatments against evolving influenza virus strains and the critical demand for enhanced poultry health management strategies.

Key words: Belamcanda extract, H9N2 avian influenza virus, immunological signaling pathway, cytokine modulation, antiviral therapy

INTRODUCTION

Influenza viruses are categorized into 3 main types: A, B, and C, distinguished by variations in their nucleoproteins and M proteins (Nogales et al., 2019). Among Type A, the H9N2 subtype avian influenza virus (AIV) is notably prevalent in poultry due to its robust mutagenic and genetic recombination abilities (Imai et al., 2012, Wei and Li, 2018). Recent comparative studies further underscore the genetic diversity and evolving pathogenicity of H9N2 strains across different poultry populations, revealing variations in their seroprevalence and molecular characteristics (Eladl et al., 2019a). Despite its relatively low pathogenicity, H9N2′s pervasive presence in the poultry industry has culminated in considerable economic burdens and sporadic zoonotic transmissions, thereby elevating it to a significant public health threat (Wang et al., 2021, Zhang et al., 2022). Upon infecting avian hosts, H9N2 AIV mainly targets the respiratory system, triggering strong inflammatory responses and potential host fatalities (Xie et al., 2021). Co-infections, particularly with pathogens like Salmonella enteritidis, can exacerbate the disease severity, suggesting a complex interplay that may influence the pathogenesis and control of H9N2 infections (Arafat et al., 2020).The rapid evolutionary dynamics of this virus, coupled with its capacity to circumvent vaccine-induced immunity, underscores the urgency for novel countermeasures (de Vries et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2023). Furthermore, immunostimulants, including herbal extracts, have shown promise in enhancing vaccine efficacy and modulating immune responses in poultry challenged with H9N2, highlighting the potential of integrative approaches in disease management (Eladl et al., 2020).

The host's inflammatory response to AIV infection epitomizes a multifaceted interplay between the viral pathogens and the immune system, with Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) playing a pivotal role in this dynamic (Huo et al., 2018). Recent studies have demonstrated that following infections with highly pathogenic AIV, there is a significant increase in the expression of TLR3 and IFN-β in the pulmonary and cerebral tissues of chicks. This points to the central role of TLR3 in mediating the immune defenses against avian influenza (Raj et al., 2023). As a critical pattern recognition receptor, TLR3 is adept at identifying viral RNA, triggering a cascade of signaling mechanisms upon activation. These mechanisms predominantly activate the NF-κB signaling pathway, orchestrating the production of both inflammatory and antiviral responses. Specifically, in avian influenza scenarios, an overstimulated NF-κB pathway may intensify the inflammatory response of the host (Alexopoulou et al., 2001), potentially leading to severe physiological ramifications.

Belamcanda, a revered herb in traditional Chinese medicine documented in “Shennong's Herbal,” exhibits a rich pharmacological profile. Contemporary studies have elucidated its diverse array of bioactive components, notably tectoridin, tectorigenin, irigenin (Li et al., 2022; Patel, 2023), and others, encompassing flavonoids, terpenoids, quinones, phenolic compounds, ketones, and organic acids (Zhang et al., 2016). These constituents have demonstrated potent anti-inflammatory, antiviral, and antioxidant capabilities, modulating the immune system and mitigating inflammation-induced tissue damage (Woźniak and Matkowski, 2015). Particularly, flavonoids in Belamcanda are postulated to adjust the Th1/Th2 immune equilibrium and inhibit inflammatory mediator secretion (Gandhi et al., 2018). The herb's capabilities extend to boosting bacterial phagocytosis and reducing macrophage inflammatory responses during bacterial infections (Xiang et al., 2024). Notably, in the context of deadly inflammatory reactions triggered by viruses like H9N2, Belamcanda's attributes present valuable therapeutic possibilities, potentially interrupting the viral life cycle (Zhou et al., 2021). This herb's comprehensive pharmacological effects, evidenced by its roles in alleviating colitis, reducing asthma symptoms, and triggering apoptosis in breast cancer cells, underscore its versatile therapeutic potential (Szandruk et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2022; Guo et al., 2023). However, despite Belamcanda showing a spectrum of pharmacological activities, current research does not explicitly delineate its role in avian influenza. Considering the crucial role of the TLR3-TRIF-NF-κB signaling axis in viral pathogenesis, Belamcanda's potential modulation of this pathway, especially via its flavonoid components, might yield novel insights for managing H9N2 infections (Chen et al., 2021). Continued investigation into this signaling interaction and Belamcanda's influence therein holds significant promise for advancing therapeutic strategies in viral disease settings.

In this study, we explore the therapeutic potential of Belamcanda extract in combating H9N2 AIV infection, with a particular emphasis on modulating the TLR3/TRIF/NF-κB signaling pathway. Conducted in specific pathogen-free (SPF) chicks, our research aims to elucidate the impact of the extract on the complex immune responses triggered by H9N2 AIV. We have established a rigorous and scientifically robust H9N2 AIV infection model, encompassing detailed procedures such as the determination of the median tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) of H9N2 AIV, measurement of the median toxic concentration (TC50) of Belamcanda extract, evaluation of the antiviral pharmacodynamics of the extract, comprehensive pathological observations, and analysis of inflammatory cytokines and proteins related to the TLR3/TRIF/NF-κB signaling pathway. These methodologies ensure the reliability and relevance of our findings within the broader context of avian influenza research.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

All animal work in this study met the minimum standards of animal welfare as described in the International Guiding Principles for Biomedical Research involving Animals (at https://grants.nih.gov/grants/olaw/Guiding_Principles_2012.pdf). The ethical conduct of all animal-related procedures was rigorously ensured, complying with the protocols sanctioned by the Animal Care and Use Committee. The Institute of Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Medicine granted formal approval for this study (Permit number: BUA2022070), reflecting our commitment to ethical research practices. In line with these guidelines, we implemented comprehensive measures to minimize animal suffering and enhance their welfare, embodying the ethos of responsible and humane scientific inquiry. These measures included the use of anesthetics, optimized handling techniques, and a stringent adherence to the principle of the 3Rs (Replacement, Reduction, Refinement) to mitigate the impact on the animals involved (MacArthur Clark, 2018).

Cell Lines and Viruses

In this study, we utilized Madin Darby Canine Kidney (MDCK) cells and the H9N2 AIV to assess the antiviral properties of Belamcanda extract.

MDCK Cells: MDCKs, preserved in our laboratory, were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM; BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco-BRL, New York) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin antibiotic/antimycotic mixture (GIBCO-BRL, New York), and maintained at 37℃ in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Viruses: The low pathogenicity avian influenza virus (LPAIV) H9N2 subtype, with GenBank accession numbers FJ499463-FJ499470, was obtained from the laboratory of the China Agricultural University. These viruses were propagated in either MDCKs or 9-day-old SPF embryonated chicken eggs, as previously described (Mostafa et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020).

Hemagglutination Assay

For the HA assay, we followed a 2-stage process, adapted from established protocols (Awadin et al., 2019), focusing on the preparation of a 1% Chicken RBC Suspension and the Hemagglutination Test. This involved collecting blood from SPF roosters, preparing the RBC suspension, and conducting the assay using a 96-well V-bottom plate to determine the HA titer. Detailed steps and conditions are consistent with those described in the referenced literature, ensuring both reproducibility and clarity in our methodology.

Determination of H9N2 AIV EID50

The 50% egg infectious dose (EID50) for H9N2 was calculated using the Reed-Muench method (Reed and Muench, 1938). Starting from a virus sample with a 210 HA titer, it was serially diluted in PBS (10−1 to 10−10). Each dilution (0.1 mL) was inoculated into five 9-day-old SPF embryonated chicken eggs, incubated at 37℃ for 120 h. Eggs that perished were refrigerated immediately.

After 5 d, eggs were refrigerated overnight at 4℃. Allantoic fluids were extracted, and HA titers assessed, with HA≥1:128 indicating infection. The EID50 is calculated using the following formula:

Note: L represents the log dilution factor of the highest dilution causing less than 50% mortality.

d is the log interval between successive dilutions.

s denotes the span of the percentage response between 2 adjacent dilutions.

F is the fractional part of the response that 50% lies above at the dilution L.

Determination of H9N2 AIV TCID50

TCID50 for H9N2 in MDCK cells was determined using the Reed and Muench method (Ramakrishnan, 2016). MDCK cells at 1×104 cells/ml were seeded into a 96-well plate and cultured at 37℃, 5% CO2 to 80% confluence. After PBS washing, viral titration was performed with tenfold serial dilutions (10−1 to 10−10) of H9N2 AIV. Post 1-hour adsorption at 37℃ in 5% CO2, cells were maintained in 2% DMEM. Wells with >70% Cytopathic Effect (CPE) after 72 h indicated positive infection.

Separately, MDCK cells in 6-well plates at >90% confluence were exposed to 1x, 50x, and 100x TCID50 of the virus to identify the optimal dose for CPE induction, based on cell observation and analysis.

Determination of TC50 of Belamcanda Extract

The TC50, or the concentration causing 50% cytotoxicity, of Belamcanda extract was determined using the Reed-Muench method. The extract was serially diluted in trypsin-containing medium across ten concentrations (5,000 to 9.8 µg/mL) at 2-fold intervals. MDCK cells in a 96-well plate were prepared by discarding growth medium and performing 3 PBS washes, followed by the addition of 200 µL of each extract concentration to quadruplicate wells. The plates were incubated at 37℃ and 5% CO2.

Cell morphology changes were observed under a microscope over 72 h, with a control group of normal cells for comparison. The calculation of the TC50 was conducted employing the Reed-Muench method, analogous to the approach used for EID50 determination.

Antiviral Pharmacology Study of Belamcanda Extract

The antiviral effects of Belamcanda extract were assessed through 3 approaches, using dilutions ranging from 20,000 µg/mL to 625 µg/mL.

Prophylactic Administration (Antiviral Adsorption): MDCK cells in a 96-well plate were pre-treated with 100µL of extract for 4 h, then exposed to 100 TCID50 of the virus for 2 h. Postexposure, cells were maintained at 37℃ in 5% CO2 for 72 h. Controls included cells with maintenance medium and virus-infected cells.

Therapeutic Administration (Inhibition of Virus Synthesis and Release): After a 2-h virus exposure, cells were treated with the extract for 4 h, followed by the same post-treatment protocol as in prophylactic administration..

Direct Virucidal Activity of the Drug: A mixture of extract and 100 TCID50 virus solution was incubated for 2 h, then applied to cells for an additional 2 h, followed by a 72-h culture in maintenance medium.

CPE was observed daily, and antiviral efficacy quantified via MTT assay, measuring OD at 490 nm. Inhibition rate was calculated using the formula:

Animal Handling and Experimental Design

Our study utilized 60 SPF embryonated chicken eggs for virus amplification and EID50 determination. Additionally, 120 SPF Bai Ling broiler chickens, supplied by Beijing Boehringer Ingelheim Co., Ltd. (SCXK (Beijing) 2022-0007), were divided into 2 main experiments:

Experiment 1 assessed the pathogenicity of the H9N2 Avian Influenza Virus (AIV) in specific pathogen-free (SPF) chickens. We divided forty-eight 21-day-old chickens into 4 groups (12 chickens each), which were exposed to varying concentrations of H9N2 AIV, in addition to a control group (Table 1). Each chicken received their specific viral dose via oral gavage, ensuring precise and consistent dosing across all subjects. Following the methodology of Arafat et al. (2018), clinical signs scores, alongside parameters such as body temperature, weight changes, and mortality rates, were meticulously monitored over a period of 7 d postinfection.

Table 1.

Experiment 1: Impact of H9N2 avian influenza virus on SPF chickens.

| Group number | Description | Treatment details | Number of chickens | Age of chickens | Monitoring period |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Low concentration | Infected with 10 times the EID50 of H9N2 AIV | 12 | 21 days old | 7 d |

| 2 | Medium concentration | Infected with 100 times the EID50 of H9N2 AIV | 12 | 21 days old | 7 d |

| 3 | High concentration | Infected with 1000 times the EID50 of H9N2 AIV | 12 | 21 days old | 7 d |

| 4 | Control group | Given PBS only | 12 | 21 days old | 7 days |

Experiment 2 aimed to evaluate the efficacy of Belamcanda extract in combating H9N2 AIV. For this purpose, seventy-two 21-day-old SPF chickens were organized into 6 groups (12 chickens each), including a blank control, a virus control, and 4 treatment groups (Table 2). The treatment groups received varying doses of Belamcanda extract administered via oral gavage to ensure uniform dosing. Observations over a 7-d period postinfection mirrored those of Experiment 1, with additional emphasis on assessing the antiviral effects of the extract.

Table 2.

Experiment 2: efficacy of Belamcanda extract against H9N2 AIV.

| Group number | Description | Treatment details | Number of chickens | Age of chickens | Monitoring period |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Blank Control | Given PBS only | 12 | 21 days old | 7 d |

| 2 | Virus Control | Infected with H9N2 AIV, no subsequent treatment | 12 | 21 days old | 7 d |

| 3 | Low-Dose Belamcanda | Infected with H9N2 AIV and treated with 300 mg/kg/day Belamcanda extract | 12 | 21 days old | 7 d |

| 4 | Medium-Dose Belamcanda | Infected with H9N2 AIV and treated with 600 mg/kg/day Belamcanda extract | 12 | 21 days old | 7 d |

| 5 | High-Dose Belamcanda | Infected with H9N2 AIV and treated with 1200 mg/kg/day Belamcanda extract | 12 | 21 days old | 7 d |

| 6 | Antiviral Control | Infected with H9N2 AIV and treated with Amantadine (100 ppm) | 12 | 21 days old | 7 d |

Sample Collection and Procedure

Sampling was conducted at 1, 3, 5, and 7 d postinfection with H9N2 Avian Influenza Virus to monitor the progression of the infection and the corresponding immune response. On these specified days, 3 chickens from each group were selected at random for blood collection via cardiac puncture. The blood samples were immediately placed into anticoagulant tubes for plasma preparation.

Adhering to ethical standards, the selected chickens were humanely euthanized using inhaled CO2 to minimize distress on the 7th d postinfection with H9N2 Avian Influenza Virus. Following euthanasia, tracheal, lung, and duodenal tissues were carefully harvested, rinsed with saline to remove any contaminants, and processed for further analysis. Tissue segments intended for histological examination were fixed in 10% formalin, while others were preserved at -80℃ for subsequent cytokine analysis, RNA, and protein extractions, facilitating detailed future studies.

Pathological Observation Post H9N2 AIV Infection and Belamcanda Treatment

The histological examination of the collected tissues was conducted to assess the impact of H9N2 AIV infection and Belamcanda treatment (Awadin et al., 2020). After fixation in 10% formaldehyde for 24 h, tissues were processed, paraffin-embedded, sectioned (4 µm), and stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E). Observations were made using a DP80 Digital light microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), with images captured for analysis.

Using ImagePro Plus 6.0, morphometric analysis was conducted, including measurements of villus height and crypt depth in duodenal tissues, and assessment of tracheal and lung tissues for epithelial integrity, ciliary morphology, alveolar wall thickening, and inflammatory cell infiltration. At least ten fields per sample were examined for robustness.

ELISA Determination of Cytokine Levels

Blood samples for cytokine analysis were collected from 3 euthanized chickens per group on d 1, 3, 5, and 7 postinfection. Blood was allowed to settle at room temperature for 30 min, centrifuged for 15 min, and the supernatant stored at -80℃.

IL-1, IL-2, IL-6, and TNF-α levels were measured using ABclonal ELISA kits (Wuhan, China), following the manufacturer's protocols. Samples were homogenized, centrifuged at 1,000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4℃, and the supernatant used for ELISA. OD readings at 450 nm were taken using a TECAN F50 spectrophotometer (Mannedorf, Switzerland).

RNA Extraction and Real-Time Quantitative PCR

On d 1, 3, 5, and 7, pharyngeal and cloacal swabs were collected from 3 chickens per group using sterile cotton swabs. RNA was isolated using the TransZol Up kit (Takara, Dalian, China), reverse transcribed to cDNA, and stored at -80℃.

RT-qPCR was conducted with 2 × Hieff UNICON Universal Blue qPCR Master Mix (Yeasen, Shanghai, China). The protocol included UDG activation (50℃ for 2 min), denaturation (95℃ for 2 min), followed by 40 cycles of 95℃ for 15 sec (denaturation) and 60℃ for 30 sec (annealing/extension). A melting curve analysis confirmed PCR product specificity. Samples were run in triplicate. β-actin rRNA was the endogenous control (Meng et al., 2022). Gene expression was quantified using the 2−ΔΔCT method. Data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8.

Western Blotting Analysis for Protein Expression in lung tissue

Lung tissues from SPF chicks stored at -80℃ were used for Western blot. Tissues were homogenized in cold RIPA buffer with PMSF (100:1) and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 20 min at 4℃. The supernatants were reserved for protein analysis, with concentrations determined by BCA assay (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Proteins were separated via 15% SDS-PAGE and transferred to membranes at 100 V for 2 h. The membranes were blocked and incubated overnight at 4℃ with primary antibodies, including TLR3, NF-κB p65, IRF3 (Jiangsu Qinke Biotechnology), β-actin, and GAPDH (Wuhan Sanying Biotechnology). This was followed by 90 minutes of secondary antibody incubation. Protein bands were visualized using an Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI-COR Biosciences) and quantified against β-actin or GAPDH using ImageJ software.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism (Version 8.0, San Diego, CA), with results presented as means ± SD. Unpaired Student's t-tests were used for 2-group comparisons, while one-way ANOVA was applied for multiple group comparisons.

Relative quantification in RT-qPCR was performed using the 2-ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). Western blot band intensities were quantified with ImageJ software. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 for all analyses.

RESULTS

H9N2 AIV Hemagglutination Assay Results and EID50 Determination

We established the initial HA titer of the H9N2 avian influenza virus stock at 6log2, which, following propagation in chicken embryos, increased to 9log2. The Reed-Muench method facilitated the calculation of the EID50 for H9N2 AIV, determined to be 10−7.67/100µL. This measurement is instrumental in understanding the viral infectivity and ensuring accurate dosing in our experimental infection model.

TCID50 of H9N2 AIV and TC50 of Belamcanda Extract

In assessing the pathogenicity of H9N2 AIV and the therapeutic potential of Belamcanda extract, we quantified the TCID50 for the virus and the TC50 for the extract. The TCID50 of H9N2 AIV was calculated as 10−4.85/100µL using the Reed-Muench method, indicating the virus's potency. Similarly, the TC50 for Belamcanda extract was determined to be 20000 × 2−2.263 (Table 3), reflecting the concentration at which the extract begins to exhibit cytotoxic effects. These findings provide a quantitative basis for evaluating the antiviral efficacy of Belamcanda extract in comparison to the viral challenge posed by H9N2 AIV.

Table 3.

TC50 toxic effects of Belamcanda extract in MDCK cells.

| Belamcanda extract (µg/mL) | Observed CPE |

Cumulative CPE |

Infection rate (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Well count | CPE positive wells | CPE negative wells | Cumulative CPE positive wells | Cumulative CPE negative wells | Proportion of CPE positive wells | CPE positive rate (%) | |

| 20,000 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 17/17 | 100 |

| 10,000 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 11/11 | 100 |

| 5,000 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 5/7 | 71.43 |

| 2,500 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 1/8 | 12.5 |

| 1,250 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 13 | 0/13 | 0 |

| 625 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 19 | 0/19 | 0 |

CPE, cytopathic effect.

Body Weight and Tissue Pathology in H9N2 AIV Infected Chicks

As shown in Table 4, chicks in the blank control group exhibited a consistent increase in body weight, with no notable pathological changes observed. In contrast, chicks infected with the H9N2 Avian Influenza Virus demonstrated varied responses dependent on the viral concentration. Notably, those in high virus concentration groups exhibited the slowest weight gain, highlighting the impact of viral load on growth rates. Beyond weight changes, infected chicks displayed distinct clinical signs indicative of avian influenza infection. These included ruffled feathers, signs of lethargy, and notable alterations in water and feed intake, particularly in groups subjected to higher concentrations of the virus.

Table 4.

Body weight changes of chicks 1 to 7 d after attack with H9N2 subtype AIV.

| Group | Average initial weight (g) | Average final weight (g) | Average weight gain (g) | Relative weight gain rate (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blank control group | 185.00 ± 6.02 | 294.92 ± 6.63 | 112.87 ± 8.95 | 61.01 | ns |

| Low virus concentration group | 195.25 ± 5.58 | 284.42 ± 4.08 | 89.17 ± 6.91 | 45.67 | 0.0004 |

| Medium virus concentration group | 178.42 ± 11.44 | 259.83 ± 4.11 | 81.42 ± 12.15 | 45.63 | 0.0004 |

| High virus concentration group | 181.67 ± 12.53 | 259.25 ± 5.28 | 77.58 ± 13.59 | 42.70 | 0.0006 |

n = 12 replicates per treatment.

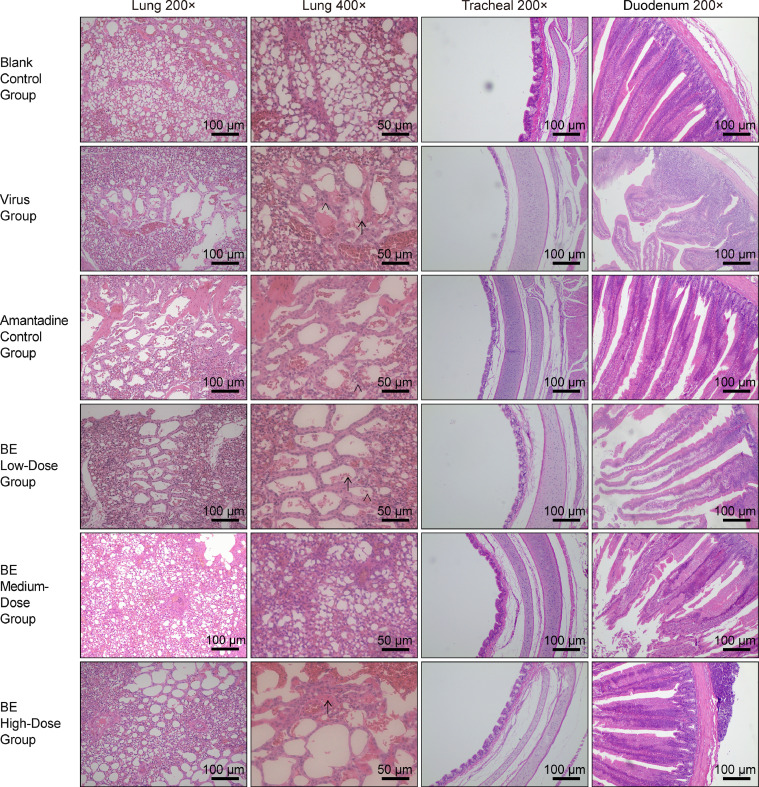

Lung tissue pathology on d 7 postinfection varied with virus concentration. In the control group, lung tissues appeared normal, devoid of any pathological changes. Conversely, the high concentration groups demonstrated pronounced erythrocyte infiltration and significant exudate accumulation within tertiary bronchi, indicative of severe inflammatory response. Medium concentration groups showed a moderate degree of erythrocyte infiltration and minimal exudate, whereas low concentration groups were characterized by scant exudate presence, negligible cell infiltration, and slight capillary wall thickening, suggesting a milder inflammatory reaction.

Tracheal changes showed intact cilia in the control group, reflecting healthy tracheal tissue. In contrast, both high and medium viral concentration exposures resulted in sparse cilia, disrupted cell arrangement, and noticeable structural alterations in mucosal and cartilaginous layers. The low concentration group, however, exhibited a more organized cellular structure with minimal structural deviations, illustrating a lesser degree of pathogenic impact.

Duodenal pathology in the control group showed intact, neatly arranged villi and glands. High viral concentrations severely disrupted villous architecture, evidenced by extensive exudate and cellular disorganization. Medium concentration infections led to moderate villi disruption, less exudate, and mild cellular disorganization. In contrast, low concentrations resulted in minor villous shortening and disruption, without significant alterations in the muscular or serous layers, indicating minimal duodenal tissue compromise (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Histopathological analysis of lung, tracheal, and duodenal tissues in chickens following H9N2 AIV infection. The group designations, noted on the left margin of each row, from top to bottom, include the blank control group, low virus concentration group, medium virus concentration group, and high virus concentration group. The magnifications of the tissues, indicated at the top of each column, from left to right, are Lung 200×, Lung 400×, Tracheal 200×, and Duodenum 200×, respectively. Inflammatory cells and exudates in the images are indicated by → and >, respectively. Scale bar = 100 μm or 50 μm, as applicable.

Antiviral Effects of Belamcanda Extract

Anti-Adsorption Effect on H9N2 AIV: Based on Table 5A, Belamcanda extract at concentrations of 62.5 to 250 and 1,000 to 2,000 μg/mL significantly increased OD490 nm values compared to the virus control group (P < 0.05), indicating an inhibitory effect on H9N2 AIV adsorption.

Table 5A.

Effect of Belamcanda extract on H9N2 AIV adsorption.

| Group | Concentration (µg/ml) | OD490nm | Inhibition Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Belamcanda Extract | 2000 | 0.608 ± 0.011**# | 13.9 |

| 1000 | 0.683 ± 0.008*# | 23.9 | |

| 500 | 0.701 ± 0.065* | 26.3 | |

| 250 | 0.703 ± 0.022**# | 26.6 | |

| 125 | 0.723 ± 0.019**# | 29.3 | |

| 62.5 | 0.654 ± 0.030**# | 20.1 | |

| Blank Control Group | ——— | 1.255 ± 0.083 | ——— |

| Virus Group | ——— | 0.503 ± 0.036** | ——— |

The asterisks indicate the level of statistical significance where * p < 0.05 and ** p < 0.01 compared to the virus control group. The hash symbol (#) denotes p < 0.05 compared to the negative control group. The OD490nm values are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Anti-Replication Effect on H9N2 AIV:Table 5B shows that OD490 nm values in the virus control group were lower than in the blank control (P < 0.05). Belamcanda extract at 62.5, 250 to 1,000 μg/mL, especially at 125 μg/mL, significantly improved OD490 nm values (P < 0.01), suggesting inhibition of H9N2 AIV replication.

Table 5B.

Effect of Belamcanda extract on H9N2 AIV replication.

| Group | Concentration (µg/ml) | OD490nm | Inhibition Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Belamcanda extract | 2000 | 0.608 ± 0.011*** | 15.7 |

| 1000 | 0.729 ± 0.035**# | 30.8 | |

| 500 | 0.749 ± 0.021***# | 33.3 | |

| 250 | 0.808 ± 0.078***# | 40.6 | |

| 125 | 0.781 ± 0.041**## | 34.6 | |

| 62.5 | 0.800 ± 0.013***# | 39.6 | |

| Blank control group | ——— | 1.285 ± 0.015 | ——— |

| Virus group | ——— | 0.482 ± 0.054* | ——— |

The asterisks indicate the level of statistical significance where * p < 0.05 and ** p < 0.01 compared to the virus control group. The hash symbol (#) denotes p < 0.05 compared to the negative control group. The OD490nm values are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Direct Virucidal Effect on H9N2 AIV: Referring to Table 5C, Belamcanda extract at 62.5, 500, and 2,000 μg/mL notably raised OD490 nm values compared to the virus control (P < 0.05), suggesting a direct virucidal effect against H9N2 AIV.

Table 5C.

Effect of Belamcanda extract on direct inactivation of H9N2 AIV.

| Group | Concentration (µg/mL) | OD490nm | Inhibition rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Belamcanda extract | 2000 | 0.729 ± 0.050*# | 23.7 |

| 1000 | 0.758 ± 0.060* | 27.7 | |

| 500 | 0.782 ± 0.066# | 31.0 | |

| 250 | 0.710 ± 0.061* | 21.1 | |

| 125 | 0.637 ± 0.043** | 10.9 | |

| 62.5 | 0.697 ± 0.055*# | 19.3 | |

| Blank control group | ——— | 1.280 ± 0.089 | ——— |

| Virus group | ——— | 0.558 ± 0.024** | ——— |

The asterisks indicate the level of statistical significance where * p < 0.05 and ** p < 0.01 compared to the virus control group. The hash symbol (#) denotes p < 0.05 compared to the negative control group. The OD490nm values are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Belamcanda Extract Treatment for Chicks Infected with Different Concentrations of H9N2 AIV: Changes in Body Weight and Pathological Observations

Post 24-hour infection, SPF chicks were medicated, and weight changes were recorded (Table 6). The virus control group had a reduced weight gain rate compared to the blank control. Both medium and high-dose Belamcanda extract treatments increased the growth rate compared to the virus control. The low-dose group also showed improvement.

Table 6.

Body weight changes on the 1st to 7th day after treatment with Belamcanda extract.

| Group | Average initial weight (g) | Average final weight (g) | Average weight gain (g) | Relative weight gain rate (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blank control group | 187.75 ± 6.61 | 301.08 ± 7.39 | 113.33 ± 8.14 | 60.36 | ns |

| Virus group | 190.42 ± 4.40 | 268.50 ± 5.42 | 78.08 ± 5.82 | 41.00 | < 0.0001 |

| BE low dose group | 194.33 ± 3.77 | 278.75 ± 4.99 | 84.42 ± 3.92 | 43.44 | < 0.0001 |

| BE medium dose Group | 191.58 ± 7.38 | 282.75 ± 4.09 | 91.17 ± 8.91 | 47.59 | 0.0021 |

| BE high dose group | 185.92 ± 9.04 | 286.92 ± 5.63 | 101.00 ± 9.20 | 54.32 | 0.0393 |

| Amantadine control group | 189.00 ± 7.84 | 277.08 ± 5.23 | 88.08 ± 8.97 | 47.17 | 0.0005 |

n = 12 replicates per treatment, Abbreviation: BE, Belamcanda extract.

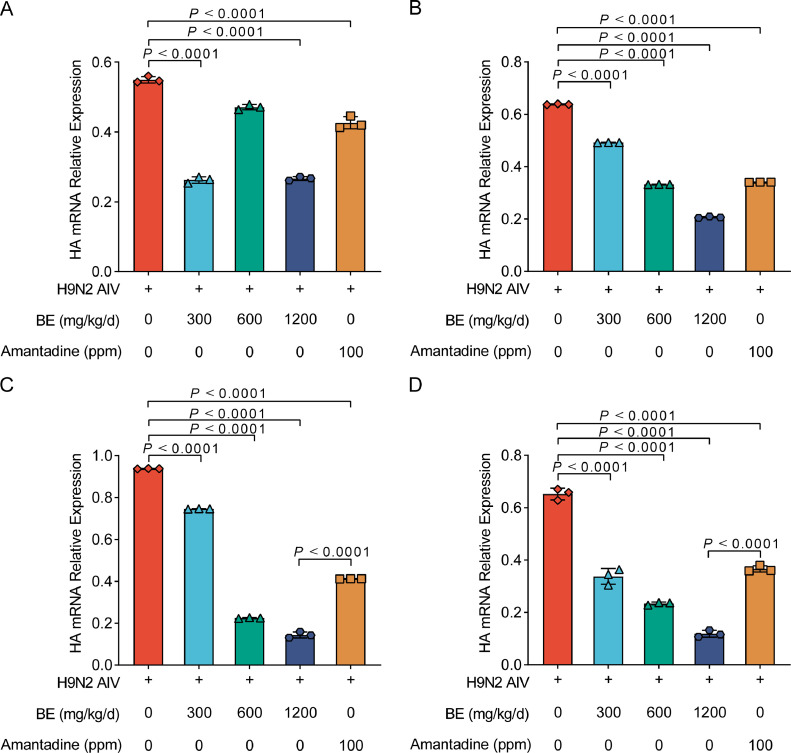

In the investigation of lung tissue pathology postinfection with H9N2 AIV, varying responses were observed across different groups. In the blank control group, lung tissues displayed standard morphology, characterized by thin-walled capillaries. However, significant pathological changes were evident in the positive control group, including marked erythrocyte infiltration, the presence of exudates, and irregular bronchial structures. Notably, treatment with both high and low doses of Belamcanda extract, as well as Amantadine, resulted in minimal inflammatory cell presence and led to more regular bronchial walls and capillary thickening. Specifically, the medium dose of Belamcanda extract showed no exudation while maintaining regular bronchial walls but was associated with capillary thickening and a reduction in lumen size.

Tracheal tissue changes further delineated the impact of treatments. The blank control samples preserved intact cilia and demonstrated a neat cellular arrangement. In contrast, the virus control group's tracheal samples revealed sparse cilia, irregular cell formation, and an increased distance between mucosa and cartilage. Treatment with Amantadine and various doses of Belamcanda extract showed improvements, with clearer mucosal structures and fewer elastic fibers. Particularly, the medium dose of Belamcanda resulted in neatly arranged cells, clear elastic fibers, and a mucosal layer closer to the cartilage, indicating a protective effect.

The duodenal tissue assessment also mirrored these findings. The blank control group exhibited intact and orderly arranged villi and glands, while the positive control group showed disrupted villi structure, characterized by noticeable exudate and cell disorganization. Treatment with Amantadine and high doses of Belamcanda extract led to shorter villi, albeit without significant changes in the muscular or serous layers. Interestingly, both medium and low doses of Belamcanda caused visible disruptions in villi, exudation, and less distinct gland boundaries, suggesting a dose-dependent effect on the gastrointestinal tract (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Histopathological analysis of lung, tracheal, and duodenal tissues in chickens post H9N2 AIV infection and Belamcanda extract treatment. The group designations, noted on the left margin of each row from top to bottom, are as follows: blank control group, virus group, amantadine control group, BE (Belamcanda extract) low-dose group, BE medium dose group, and BE high-dose group. The magnifications of the tissues, indicated at the top of each column from left to right, are Lung 200×, Lung 400×, Tracheal 200×, and Duodenum 200×, respectively. Inflammatory cells and exudates in the images are indicated by → and >, respectively. Scale bar = 100 μm or 50 μm, as applicable.

Quantitative PCR Analysis of H9N2 AIV HA Gene Expression

As shown in Figure 3, through fluorescent quantitative PCR analysis, a significant reduction trend in the expression of the H9N2 AIV HA gene was observed in the mucosal secretions from SPF chicks across various postinfection d (1, 3, 5, and 7) and different treatment groups. Initially (Figure 3A), just a single gavage treatment with medium Belamcanda extract and Amantadine significantly lowered HA mRNA levels compared to the virus control group (P < 0.01), with both high and low concentration groups also displaying notable reductions (P < 0.05). This effect was sustained and even more pronounced after 3 d (Figure 3B) of continuous medication across all Belamcanda extract concentrations and the Amantadine group, relative to the virus control (P < 0.01). By the fifth day of consistent treatment (Figure 3C), the decline in HA mRNA levels was significant across high, medium, and low concentration Belamcanda extract groups, as well as the Amantadine group, in comparison to the virus control (P < 0.01). Extending the treatment to seven days (Figure 3D)resulted in a marked decline in HA mRNA levels in all treatment groups when compared to the virus group (P < 0.01), indicating a sustained and robust antiviral effect of Belamcanda extract over time

Figure 3.

Reduction in H9N2 AIV HA gene expression in SPF chicks treated with Belamcanda extract. (A–D) The trend of HA mRNA expression in mucosal secretions from SPF chicks infected with H9N2 AIV and subsequently treated with Belamcanda extract. The panels show the levels of HA mRNA after 1, 3, 5, and 7 days of treatment postinfection (A) D 1, (B) D 3, (C) D 5 (D) D 7. A significant decrease in viral HA mRNA is observed in chicks treated with medium, high, and low concentrations of Belamcanda extract as well as the Amantadine group, compared to the virus control group. Experiments were performed in triplicate, and the mean ± S.D. (n = 3) is shown. P values were determined by nonparametric 1-way ANOVA.

Effects of Belamcanda Extract on Cytokines in Chickens Infected With H9N2 AIV

In our study, we evaluated the impact of Belamcanda extract on cytokine expression in SPF chicks infected with H9N2 AIV. The expression levels of key cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1, IL-2, and IL-6, were quantified using ELISA, and the results were analyzed using GraphPad 8.3 and IBM SPSS Statistics 2.1. As depicted in Figure 4A, TNF-α levels in the serum of chicks treated with high and medium concentrations of Belamcanda extract, as well as the Amantadine group, were significantly elevated compared to the blank control. Notably, a significant increase in TNF-α expression was observed after just 1 d of postinfection treatment in these groups (P < 0.01), with the low concentration group showing a moderate increase (P < 0.05). Over the following days, high concentration Belamcanda extract and Amantadine treatments demonstrated a significant reduction in TNF-α levels compared to the virus control. Similarly, IL-1 levels showed a significant increase in the virus control and Amantadine groups after 1 d of treatment (P < 0.01), with a moderate increase in the low concentration Belamcanda extract group (P < 0.05) as shown in Figure 4B. However, the medium concentration Belamcanda extract group exhibited a notable reduction in IL-1 levels over time when compared to the virus group (P < 0.05). As for IL-2 expression, analyzed and presented in Figure 4C, there was a significant increase in the high concentration Belamcanda extract and Amantadine groups compared to the blank control after 1 d of treatment (P < 0.01). However, the low concentration Belamcanda extract group showed a non-significant reduction in IL-2 levels over the course of the study. Lastly, the IL-6 levels, as shown in Figure 4D, indicated a significant increase in the low concentration Belamcanda extract group after one day of treatment (P < 0.05). By d 7 postinfection, both the medium concentration Belamcanda extract and Amantadine groups demonstrated a significant reduction in IL-6 expression (P < 0.01).

Figure 4.

Cytokine expression in SPF Chicks Infected with H9N2 AIV Following Treatment with Belamcanda Extract. (A–D) The cytokine expression levels post H9N2 AIV infection and subsequent treatment with Belamcanda extract at various dosages. (A) TNF-α levels, (B) IL-1 levels, (C) IL-2 levels, and (D) IL-6 levels in the serum of treated chicks. Experiments were performed in triplicate, and the mean ± S.D. (n = 3) is shown. P values were determined by non-parametric one-way ANOVA.

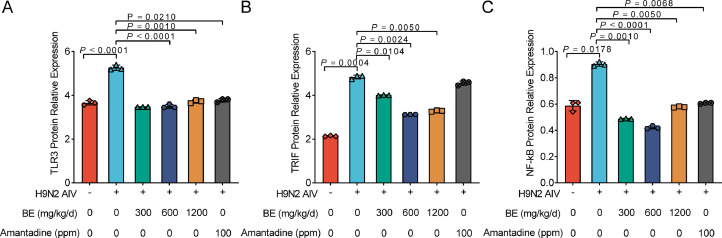

Effects of Belamcanda Extract on TLR3, TRIF, and NF-κB Protein Expression in H9N2 AIV Infected Chicks

In assessing the impact of Belamcanda extract on key immunological proteins in the lung tissues of SPF chicks infected with H9N2 AIV, Western blotting was employed to measure the expression of TLR3, TRIF, and NF-κB over a 7-d period. The analysis revealed a marked modulation of these proteins in response to treatment. Specifically, the expression of TLR3 showed a significant decrease in chicks treated with all concentrations of Belamcanda extract and the Amantadine group, compared to the virus control group (P < 0.01), as depicted in Figure 5A. This was mirrored in the expression of TRIF, where a similar trend of significant reduction was observed in all treatment groups, with Belamcanda extract showing a more pronounced effect (P < 0.01) than Amantadine (P < 0.05), as seen in Figure 5B. The expression of NF-κB followed a comparable pattern, with both the Amantadine group and high concentration Belamcanda extract presenting a notable decrease in expression levels (P < 0.05), while medium and low concentration Belamcanda extract groups exhibited even greater reductions (P < 0.01). Notably, when compared to the blank control, the high concentration Belamcanda extract group showed a marked reduction in NF-κB protein expression (P < 0.05), as illustrated in Figure 5C. These results underscore the potent effect of Belamcanda extract in modulating key immunological pathways in chicks infected with H9N2 AIV. The significant downregulation of TLR3, TRIF, and NF-κB proteins is in line with the anticipated therapeutic action of the extract, highlighting its potential as an effective agent in managing H9N2 AIV infection.

Figure 5.

Modulation of TLR3, TRIF, and NF-κB protein expression in SPF chicks infected with H9N2 AIV and treated with Belamcanda extract. (A–C) Western blot analysis of key immunological protein expression in lung tissues of SPF chicks infected with H9N2 AIV and treated with Belamcanda extract. (A) TLR3 expression, (B) TRIF expression, and (C) NF-κB expression at various post-infection time points. The treatment groups included high, medium, and low concentrations of Belamcanda extract as well as an Amantadine group, compared to a virus control group. The significant decrease in the expression of these proteins was observed in the treatment groups, especially in the medium and high concentration Belamcanda extract groups. Experiments were performed in triplicate, and the mean ± S.D. (n = 3) is shown. P values were determined by nonparametric one-way ANOVA.

DISCUSSION

In delving into the complexities of H9N2 AIV and its potential countermeasures, this study substantially extends our existing understanding of low-pathogenic avian influenza viruses. The array of pathological changes induced by H9N2 AIV in SPF chickens, including detrimental effects on respiratory and intestinal tissues (Yitbarek et al., 2018), slow weight gain, and significant decline in feed conversion ratio, pose a significant impact on poultry farming (Zhang et al., 2020). These findings are consistent with recent reports indicating the complex interplay of H9N2 infections with host health, highlighting the need for innovative approaches to mitigate (Arafat et al., 2018, Eladl et al., 2019b) these effects .Given that Belamcanda extract has been demonstrated to possess various biological activities and pharmacological effects, it emerged as an ideal candidate in our fight against H9N2 AIV. Our study thoroughly investigates the anti-inflammatory and antiviral efficacy of Belamcanda extract against H9N2 AIV infection in chickens, particularly its impact on key cytokine expression and immune signaling pathways. Our results distinctly showcase the significant role of Belamcanda extract in modulating levels of crucial cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1, IL-2, and IL-6, which play pivotal roles in the inflammatory response induced by H9N2 AIV infection. Moreover, through Western blot analysis, we observed an effective reduction in the expression of immune signaling molecules like TLR3, TRIF, and NF-κB by Belamcanda extract. The modulation of these pathways is crucial for the immune response to viral infections, aligning with findings from other studies that have explored the impact of natural compounds on viral pathogenesis (Li et al., 2022; Patel, 2023).

In our further in-depth exploration, our findings underscore the regulatory role of Belamcanda extract in modulating the inflammatory response induced by H9N2 AIV, aligning with existing literature on other natural extracts and antiviral treatments (Stan et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2021). Notably, the initial increase followed by a significant reduction in pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6 observed with Belamcanda extract may reflect a complex immunomodulatory process (Gandhi et al., 2021). This pattern mirrors the actions of some natural remedies described in prior research, which activate the immune system during early stages of inflammation and subsequently modulate excessive inflammatory responses, thereby alleviating tissue damage (Paramita Pal et al., 2023). Additionally, our findings of Belamcanda extract significantly inhibiting the expression of key immune pathway proteins such as TLR3, TRIF, and NF-κB further emphasize its vital role in modulating host responses to viral infections. These results not only corroborate existing research on the antiviral mechanisms of traditional Chinese medicine but also provide new insights into the complex mechanisms by which these natural compounds regulate host immune responses.

Furthermore, the outcomes of this study provide significant practical guidance for understanding and addressing H9N2 AIV and other respiratory viral infections. We discovered that Belamcanda extract is effective in multiple aspects, including hindering the adsorption, replication, and direct neutralization of H9N2 AIV. Notably, even at lower doses, Belamcanda extract effectively mitigates the pathological changes caused by H9N2 AIV and reduces the expression of key cytokines, suggesting its potential as an adjunct therapy for improving immune responses and tissue damage post viral infection. In the context of the ongoing global threat posed by influenza viruses and other respiratory pathogens, the development of new antiviral strategies is especially crucial (Loregian et al., 2014; Yin et al., 2021). The antiviral and immunomodulatory properties of Belamcanda extract, particularly its regulation of signaling pathways like TLR3, TRIF, and NF-κB, provide valuable insights for the development of novel antiviral treatments. However, further studies are required to ascertain its effects on different types of viral infections and its safety and efficacy in clinical applications.

While our study marks considerable progress in exploring the efficacy of Belamcanda extract against H9N2 AIV, further investigations are necessary to fully understand its potential and applications. The primary reliance on SPF chicks as our experimental model, and the relatively limited sample size, underscore the need for broader research encompassing various poultry breeds and real-world conditions to validate and extend our findings (Baek et al., 2023). Isolating and identifying the active components within Belamcanda extract will be crucial for developing targeted antiviral therapies, potentially in synergy with existing medications, to enhance treatment efficacy and combat drug resistance. This study thus lays a foundational step towards leveraging natural extracts in devising more effective solutions for controlling the spread of H9N2 AIV and related viruses.

CONCLUSIONS

This study comprehensively investigated the anti-inflammatory and antiviral effects of Belamcanda extract on SPF chicks infected with H9N2 AIV. The results clearly demonstrate that Belamcanda extract effectively mitigates the inflammatory response triggered by viral infection, significantly reducing the expression levels of key cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1, IL-2, and IL-6. Additionally, through Western blot analysis, we discovered that Belamcanda extract markedly decreases the expression of crucial immune signaling molecules like TLR3, TRIF, and NF-κB. These findings provide new insights into the potential mechanisms by which Belamcanda extract regulates host immune responses and inhibits viral replication.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yan : Investigation, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Formal analysis. Jingjie Wei: Investigation, Writing – original draft. Zhenyi Liu: Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft. Qian Zhang: Investigation, Supervision. Tao Zhang: Investigation, Funding acquisition. Ge Hu: Conceptualization, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by theBeijing Nova Program (No. 20220484226, China), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32273050, China)

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Alexopoulou L., Holt A.C., Medzhitov R., Flavell R.A. Recognition of double-stranded RNA and activation of NF-kappaB by Toll-like receptor 3. Nature. 2001;413:732–738. doi: 10.1038/35099560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arafat N., Abd El Rahman S., Naguib D., El-Shafei R.A., Abdo W., Eladl A.H. Co-infection of Salmonella enteritidis with H9N2 avian influenza virus in chickens. Avian Pathol. 2020;49:496–506. doi: 10.1080/03079457.2020.1778162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arafat N., Eladl A.H., Marghani B.H., Saif M.A., El-Shafei R.A. Enhanced infection of avian influenza virus H9N2 with infectious laryngeotracheitis vaccination in chickens. Vet. Microbiol. 2018;219:8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2018.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awadin W.F., Eladl A.H., El-Shafei R.A., El-Adl M.A., Ali H.S. Immunological and pathological effects of vitamin E with Fetomune Plus(®) on chickens experimentally infected with avian influenza virus H9N2. Vet. Microbiol. 2019;231:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2019.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awadin W.F., Eladl A.H., El-Shafei R.A., El-Adl M.A., Aziza A.E., Ali H.S., et al. Effect of omega-3 rich diet on the response of Japanese quails (Coturnix coturnix japonica) infected with Newcastle disease virus or avian influenza virus H9N2. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2020;228 doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2019.108668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek Y.G., Lee Y.N., Cha R.M., Park M.J., Lee Y.J., Park C.K., et al. Research note: comparative evaluation of pathogenicity in SPF chicken between different subgroups of H5N6 high pathogenicity avian influenza viruses. Poult. Sci. 2023;103 doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2023.103289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Lin J., Zhao Y., Ma X., Yi H. Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) regulation mechanisms and roles in antiviral innate immune responses. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B. 2021;22:609–632. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B2000808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries R.D., Herfst S., Richard M. Avian influenza A virus pandemic preparedness and vaccine development. Vaccines (Basel) 2018;6:46. doi: 10.3390/vaccines6030046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eladl A.H., Alzayat A.A., Ali H.S., Fahmy H.A., Ellakany H.F. Comparative molecular characterization, pathogenicity and seroprevalence of avian influenza virus H9N2 in commercial and backyard poultry flocks. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019;64:81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2019.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eladl A.H., Arafat N., El-Shafei R.A., Farag V.M., Saleh R.M., Awadin W.F. Comparative immune response and pathogenicity of the H9N2 avian influenza virus after administration of Immulant(®), based on Echinacea and Nigella sativa, in stressed chickens. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019;65:165–175. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2019.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eladl A.H., Mosad S.M., El-Shafei R.A., Saleh R.M., Ali H.S., Badawy B.M., Elshal M.F. Immunostimulant effect of a mixed herbal extract on infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV) vaccinated chickens in the context of a co-infection model of avian influenza virus H9N2 and IBDV. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2020;72:101505. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2020.101505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi G.R., Jothi G., Mohana T., Vasconcelos A.B.S., Montalvão M.M., Hariharan G., Sridharan G., Kumar P.M., Gurgel R.Q., Li H.B., Zhang J., Gan Anti-inflammatory natural products as potential therapeutic agents of rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Phytomedicine. 2021;93:153766. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2021.153766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi G.R., Neta M.T.S.L., Sathiyabama R.G., Quintans J.S.S., de Oliveira E Silva A.M., Araújo A.A.S., Narain N., Júnior L.J.Q., Gurgel R.Q. Flavonoids as Th1/Th2 cytokines immunomodulators: A systematic review of studies on animal models. Phytomedicine. 2018;44:74–84. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y.P., Yi P., Shi Q.Q., Yu R.R., Wang J.H., Li C.Y., Wu Cytotoxic compounds from Belamcanda chinensis (L.) dc induced apoptosis in triple-negative breast cancer cells. Molecules. 2023;28:4715. doi: 10.3390/molecules28124715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huo C., Jin Y., Zou S., Qi P., Xiao J., Tian H., et al. Lethal influenza A virus preferentially activates TLR3 and triggers a severe inflammatory response. Virus Res. 2018;257:102–112. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2018.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai M., Watanabe T., Hatta M., Das S.C., Ozawa M., Shinya K., et al. Experimental adaptation of an influenza H5 HA confers respiratory droplet transmission to a reassortant H5 HA/H1N1 virus in ferrets. Nature. 2012;486:420–428. doi: 10.1038/nature10831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Xu Z., Gu J. UGT1A1 and UGT1A9 are responsible for phase II metabolism of tectorigenin and irigenin in vitro. Molecules. 2022;27:4104. doi: 10.3390/molecules27134104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Zhu J., Jiang H., Zhang S., Tang S., Yang R., et al. Dual-directional regulation of belamcanda chinensis extract on ovalbumin-induced asthma in guinea pigs of different sexes based on serum metabolomics. Evid. Based Complement Alternat. Med. 2022;2022 doi: 10.1155/2022/5266350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loregian A., Mercorelli B., Nannetti G., Compagnin C., Palù G. Antiviral strategies against influenza virus: towards new therapeutic approaches. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71:3659–3683. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1615-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macarthur Clark J. The 3Rs in research: a contemporary approach to replacement, reduction and refinement. Br J Nutr. 2018;120:S1–S7. doi: 10.1017/S0007114517002227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng S., Xia F., Xu J., Zhang X., Xue M., Gu M., Guo F., Huang Y., Qiu H., Yang Y. Hepatocyte growth factor protects pulmonary endothelial barrier against oxidative stress and mitochondria-dependent apoptosis. Chin. Med. J. (Engl) 2022;135:837–848. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000001916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostafa A., Mahmoud S.H., Shehata M., Müller C., Kandeil A., El-Shesheny R., Nooh H.Z., Kayali G., Ali M.A., Pleschka S. PA from a recent H9N2 (G1-Like) avian influenza a virus (AIV) strain carrying lysine 367 confers altered replication efficiency and pathogenicity to contemporaneous H5N1 in mammalian systems. Viruses. 2020;12:1046. doi: 10.3390/v12091046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogales A., Aydillo T., Ávila-Pérez G., Escalera A., Chiem K., Cadagan R., DeDiego M.L., Li F., García-Sastre A., Martínez-Sobrido L. Functional characterization and direct comparison of influenza A, B, C, and D NS1 proteins in vitro and in vivo. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:2862. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paramita Pal P., Sajeli Begum A., Ameer Basha S., Araya H., Fujimoto Y. New natural pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β) and iNOS inhibitors identified from Penicillium polonicum through in vitro and in vivo studies. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023;117 doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2023.109940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel D.K. Medicinal importance, pharmacological activity and analytical aspects of flavonoid 'Irisflorentin' from Belamcanda chinensis (L.) DC. Curr Drug Res Rev. 2023;15:222–227. doi: 10.2174/2589977515666230202123308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj S., Alizadeh M., Shoojadoost B., Hodgins D., Nagy É., Mubareka S., Karimi K., Behboudi S., Sharif S. Determining the protective efficacy of toll-like receptor ligands to minimize H9N2 avian influenza virus transmission in chickens. Viruses. 2023;15:238. doi: 10.3390/v15010238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnan M.A. Determination of 50% endpoint titer using a simple formula. World J. Virol. 2016;5:85–86. doi: 10.5501/wjv.v5.i2.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed L.J., Muench H. A simple method of estimating fifty per cent endpoints12. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1938;27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- Stan D., Enciu A.M., Mateescu A.L., Ion A.C., Brezeanu A.C., Stan D., Tanase C. Natural compounds with antimicrobial and antiviral effect and nanocarriers used for their transportation. Front. Pharmacol. 2021;12:723233. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.723233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szandruk M., Merwid-Ląd A., Szeląg A. The impact of mangiferin from Belamcanda chinensis on experimental colitis in rats. Inflammopharmacology. 2018;26:571–581. doi: 10.1007/s10787-017-0337-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Zhu W., Yang L., Shu Y. The epidemiology, virology, and pathogenicity of human infections with Avian Influenza viruses. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2021;11 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a038620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Liang T., Luo Q., Li P., Zhang R., Xu M., et al. H9N2 swine influenza virus infection-induced damage is mediated by TRPM2 channels in mouse pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells. Microb. Pathog. 2020;148 doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2020.104408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei K., Li Y. Global genetic variation and transmission dynamics of H9N2 avian influenza virus. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2018;65:504–517. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woźniak D., Matkowski A. Belamcandae chinensis rhizome–a review of phytochemistry and bioactivity. Fitoterapia. 2015;107:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2015.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang T., Zou Y., Jiang X., Xu L., Zhang L., Zhou C., Hu Y., Ye X., Yang X.D., Jiang X., Zheng Y. Irisflorentin promotes bacterial phagocytosis and inhibits inflammatory responses in macrophages during bacterial infection. Heliyon. 2024;10 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e23225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie X.T., Yitbarek A., Astill J., Singh S., Khan S.U., Sharif S., Poljak Z., Greer A.L. Within-host model of respiratory virus shedding and antibody response to H9N2 avian influenza virus vaccination and infection in chickens. Infect. Dis. Model. 2021;6:490–502. doi: 10.1016/j.idm.2021.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin H., Jiang N., Shi W., Chi X., Liu S., Chen J.L., Wang S. Development and effects of influenza antiviral drugs. Molecules. 2021;26:810. doi: 10.3390/molecules26040810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yitbarek A., Taha-Abdelaziz K., Hodgins D.C., Read L., Nagy É., Weese J.S., Caswell J.L., Parkinson J., Sharif S. Gut microbiota-mediated protection against influenza virus subtype H9N2 in chickens is associated with modulation of the innate responses. Sci Rep. 2018;8:13189. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-31613-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Ye H., Liu Y., Liao M., Qi W. Resurgence of H5N6 avian influenza virus in 2021 poses new threat to public health. Lancet Microbe. 2022;3:e558. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(22)00148-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Wei K., Xu J., Yang D., Zhang C., Wang Z., Li M. Belamcanda chinensis (L.) DC-An ethnopharmacological, phytochemical and pharmacological review. J Ethnopharmacol. 2016;186:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N., Quan K., Chen Z., Hu Q., Nie M., Xu N., Gao R., Wang X., Qin T., Chen S., Peng D., Liu X. The emergence of new antigen branches of H9N2 avian influenza virus in China due to antigenic drift on hemagglutinin through antibody escape at immunodominant sites. Emerg. Microbes. Infect. 2023;12:2246582. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2023.2246582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Zhao Q., Ci X., Chen S., Chen L., Lian J., Xie Z., Ye Y., Lv H., Li H., Lin W., Zhang H., Xie Q. Effect of baicalin on bacterial secondary infection and inflammation caused by H9N2 AIV infection in chickens. Biomed. Res. Int. 2020;2020:2524314. doi: 10.1155/2020/2524314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou B., Wang L., Liang Y., Li J., Pan X. Arctiin suppresses H9N2 avian influenza virus-mediated inflammation via activation of Nrf2/HO-1 signaling. BMC Complement Med. Ther. 2021;21:289. doi: 10.1186/s12906-021-03462-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]