Abstract

The current mixed-methods study is the first to explore Black women’s (N = 153) cognitive (e.g., worry about being perceived as sexually unresponsive) and emotional (e.g., sadness) responses to sexual pain based on age and relationship status, and coping strategies. Findings indicated significant differences in and single Black women’s cognitive and emotional responses to sexual pain compared to older and coupled Black women. Qualitative responses revealed Black women engage in several proactive coping strategies to mitigate their sexual pain, including non-penetrative activities, foreplay, tools for increasing arousal, making physical adjustments, and intimacy and sexual communication. Implications for sexual health providers are discussed.

Painful sex is a common experience among women (Fuldeore & Soliman, 2017; Orr et al., 2020; Seehusen, Baird, & Bode, 2014). In addition to physical discomfort (Yong, Mui, Allaire, & Williams, 2014), sexual pain is associated with sexual difficulties, including decreased arousal and desire, decreased sexual satisfaction, decreased sexual functioning, and increased sexual distress (Seehusen et al., 2014; Tayyeb & Gupta, 2020; Vercellini et al., 2012). Sexual pain also negatively affects general well-being (Schneider et al., 2020; Thomtén & Linton, 2013) and mental health symptoms associated with depression (De Graaff, Van Lankveld, Smits, Van Beek, & Dunselman, 2016). For example, Schneider et al. (2020) found adolescent and young adult women experiencing dyspareunia (severe genital pain during vaginal intercourse), had diminished psychological and physical functioning, decreased quality of life, and feelings of inadequacy and unattractiveness, which impaired their ability to enjoy sex. Sexual pain’s impact on women’s psychological well-being, sexual well-being, and sexual functioning necessitates identifying and using effective coping strategies to experience pleasurable sex. This study adds to the literature by exploring cognitive and emotional responses to sexual pain and coping among pre-menopausal Black women, an understudied group of women.

Most studies on coping strategies and sexual pain rely on White samples; however, White women are more likely to be diagnosed and treated than their Black counterparts (Bougie, Yap, Sikora, Flaxman, & Singh, 2019; Labuski, 2017). One in five Black women report sexual pain during their most recent sexual encounter (Townes, Fu, Herbenick, & Carter, 2019). These numbers do not account for Black women who may forgo reporting sexual pain due to cultural interpretations of sexual pain (Labuski, 2017), provider mistrust (Wells & Gowda, 2020), or providers simply not asking (Witzeman et al., 2020). Additionally, pain management literature reveals Black women are more likely than White women and non-Black women of color to be more susceptible to pain and less likely to receive adequate treatment (Mossey, 2011; Townes et al., 2019), yet, little is known about how Black women cope with sexual pain.

Proactive coping model

There are two types of coping: passive and active coping. Passive coping involves relinquishing control or responsibility for a stressful experience and is characterized by activities such as avoidance, denial, or escape (Stanisławski, 2019). Alternatively, active coping involves embracing and resolving a stressful experience through problem-solving (Stanisławski, 2019). Greenglass and Fiksenbaum (2009) refer to this type of active coping as proactive coping.

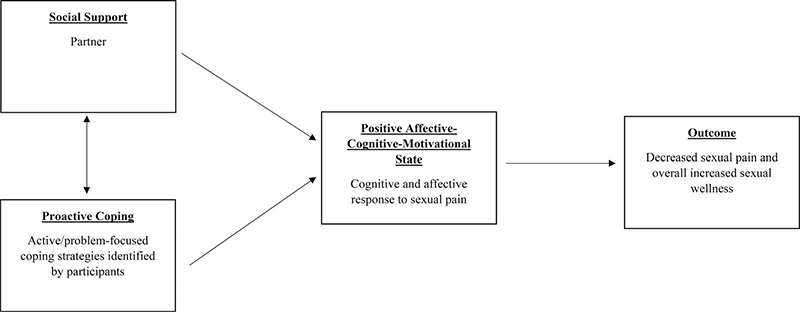

The proactive coping model (Greenglass & Fiksenbaum, 2009) posits proactive coping, social support, and affective-cognitive motivational states influence positive outcomes (see Figure 1). Typically, coping models take on a reactive approach, viewing coping as reactive to an experience of stress (Greenglass & Fiksenbaum, 2009). However, the proactive coping model uses a strengths-based approach by proposing that individuals arrive at a stressor with the ability to apply resources and discernment to engage and disengage with the stressor in appropriate ways; thus, indicating the presence of proactive coping strategies. In this paper, social support (e.g., partner support) and proactive coping share a synergistic relationship that contributes to positive affective-cognitive motivational states, which, in turn, increases the odds of positive outcomes. Examples of the positive outcomes that could result from social support, proactive coping, and a positive affective-cognitive motivational state are decreased sexual pain, decreased cognitive and emotional responses to pain, and improved sexual wellness (Blair, Pukall, Smith, & Cappell, 2015; Flink, Thomtén, Engman, Hedström, & Linton, 2015; Rosen, Bergeron, Leclerc, Lambert, & Steben, 2010; Thomtén & Linton, 2013).

Figure 1.

Proactive coping model applied to sexual pain.

The proactive coping model has been applied to various health outcomes, including psychological distress and pain from surgery (Greenglass & Fiksenbaum, 2009). To our knowledge, this is the first study to use the proactive coping model to investigate the ways Black women experience and cope with sexual pain. Black women are often conceptualized through a deficit lens that overlooks their strengths and assets relevant to sexual health (Hargons et al., 2020; Ware, Thorpe, & Tanner, 2019). Through the proactive coping model, Black women are actively engaged in problem-solving and finding ways to cope with their sexual pain so they can have pleasurable sex.

Sexual pain

Women’s sexual pain and difficulties have been defined with and without identified pathology. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) provides guidance for classifying sexual pain symptoms as Genito-Pelvic Pain/Penetration Disorder (GPPPD). According to the DSM-5, GPPPD diagnosis requires persistent or recurring difficulties with one or more of the following for at least six months: (1) vaginal penetration, (2) vulvovaginal or pelvic pain during vaginal intercourse or penetration, (3) fear or anxiety occurring during, before, or because of vaginal intercourse or penetration, (4) and tensing or tightening pelvic floor muscles during or before attempting vaginal penetration (p. 437). A lesser studied topic is sexual pain without diagnosis (Al-Abbadey et al., 2016). This study adds to the literature by providing insight into sexual pain experienced in the absence of pathology.

In this study, sexual pain is defined as unwanted and recurring genital pain during sexual intercourse. Traditionally, sexual intercourse was defined as sexual contact involving vaginal and penile penetration (Jones & Lopez, 2013). However, sex between women is excluded under this definition. Therefore, a definition of sexual intercourse was not provided for this study, which allowed participants of varying sexual orientations to determine what intercourse meant to them. Sexual pain research among samples of queer women or women who have sex with women is limited (Sobecki-Rausch, Brown, & Gaupp, 2017). Nevertheless, queer women experience sexual pain in similar and different ways than heterosexual women or women who have sex with men (Blair et al., 2015; Paine, Umberson, & Reczek, 2019). For example, a study by Paine and colleagues (2019) found that while penetration may not have been a source of pain during intercourse, some lesbian women experienced pain that made any form of sexual vaginal contact uncomfortable. Thus, this study relies on a more inclusive definition of intercourse that includes penetrative and non-penetrative sexual contact.

Responses to sexual pain

Black women must become aware of their responses to sexual pain to develop useful coping strategies. Besides addressing physical discomfort, women seek relief from adverse cognitive and emotional responses to sexual pain (Donaldson & Meana, 2011). Cognitive responses are characterized by thinking or worrying about pain, such as concerns about being a bad sexual partner or being perceived as sexually unresponsive (Dargie, Holden, & Pukall, 2017). Emotional responses, like sadness or guilt, are inner emotional states arising from experiencing sexual pain (Dargie et al., 2017). Unaddressed cognitive and emotional responses to sexual pain result in myriad consequences like increased psychological distress (e.g., pain catastrophizing, anxiety, depression; De Graaff et al., 2016; Thomtén & Linton, 2013 ) and decreased quality of sexual communication with partners (Pazmany, Bergeron, Verhaeghe, Van Oudenhove, & Enzlin, 2014).

Black women’s cultural orientation to pain may inform their pain management and responses. For example, Black women’s experiences and responses to pain often go unheard or dismissed by society (Mossey, 2011; Sabin, 2020). As a result, partners, providers, and counselors may endorse the belief that Black women have a higher pain tolerance than other groups or women. Black women’s assumed pain tolerance is grounded in gendered racism asserting there are biological differences in pain, such that Black bodies can withstand more pain and suffering than White bodies (Hoffman, Trawalter, Axt, & Oliver, 2016). Moreover, sometimes Black women internalize high pain tolerance as part of gendered racial stereotypes, roles, or scripts (i.e., Freak, Strong Black Woman/Superwoman Schema), resulting in underreporting or ignoring emotions and experiences of pain (Collins, 2008; Lewis, Mendenhall, Harwood, & Browne Huntt, 2016; Woods-Giscombé, 2010). Sexual scripts such as the promiscuous and hypersexual “Freak” or “Jezebel” influence Black women’s sexual identity development beginning in adolescence and may influence how they engage in sex as adults (Bowleg et al. 2015). Under these roles Black women are expected to be “sexually aggressive, wild, and lacking inhibitions” – inhibitions such as pain – during sex (Stephens & Phillips, 2003, p. 20). Depending on the severity of their sexual pain responses, coping strategies, social support, and cultural orientation to pain may need investigation to determine a better pathway to pleasurable sex.

Age and relationship status may also influence Black women’s responses to sexual pain. Depending on age and experience, Black women may have different responses to pain and coping. For example, younger women are less likely to advocate for themselves during painful sexual encounters due to the normalization of painful sex and prioritizing their partners (Carter et al., 2019). Pain normalization and prioritizing partners are common traits under sociocultural and gendered racial scripts Black women navigate (Bowleg et al. 2015; Collins, 2008; Lewis et al., 2016). As a result, younger women may have less pleasurable sex and engage in passive coping strategies such as avoiding or ignoring their pain. Alternatively, older women may engage in proactive coping strategies such as communicating painful sex to their partner because they have moved past cultural or gendered scripts that may inhibit younger women. Further, partners may serve as social supports that assist women in navigating sexual pain (Pazmany et al., 2014). Understanding Black women’s responses to pain broadly and based on age and relationship status contributes to the literature on how Black women cope with painful sex.

The current study

The purpose of this mixed-methods study was to quantitatively examine Black women’s cognitive and emotional responses to sexual pain. Differences in the intensity of cognitive and emotional responses based on age (under 30 versus over 30) and relationship status (single versus coupled) were explored. It was hypothesized women under 30 would have more cognitive and emotional responses to pain. This hypothesis is informed by the potential influence cultural stereotypes have on young Black women, resulting in passive coping (Bowleg et al. 2015). It was also hypothesized coupled Black women would have less thinking or worrying and negative emotions in response to pain due to partner support possibly assisting in navigating sexual pain (Pazmany et al., 2014).

Secondly, to create a more in-depth picture, we qualitatively examined Black women’s coping strategies. The open-ended research question asked: how do Black women cope with sexual pain? In support of the proactive coping model, Black women were predicted to have proactive approaches to coping with their sexual pain. Combined, these research questions would provide an understanding of Black women’s psychophysiological experience of sexual pain and methods for navigating pain to achieve pleasurable sex.

Methods

Participants

Data were from phase one of a larger IRB-approved mixed-methods study on Black women’s sexual pain and pleasure. Specific goals of the larger study included (1) determining the prevalence of sexual pain, sexual anxiety, and sexual pleasure among Black premenopausal women and (2) understanding how sociocultural factors influenced Black women’s sexual communication with their medical providers and partners. This study relied on responses to questions on responses to sexual pain and coping strategies. Eligible individuals identified as Black cisgender women. Additionally, eligible women were pre-menopausal, lived in the southern United States, and reported participation in sexual intercourse. Table 1 provides sample descriptives. The sample consisted of 153 Black women aged 19–45 (M = 29.62, SD = 5.90). Participants were predominantly heterosexual (n = 121, 79.1%) and African American (n = 140, 91.5%). Additionally, a little over half were single (n = 81, 52.9%), had a graduate or professional degree (n = 80, 52.3%), and had male sexual partners (n = 79, 51.6%).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for study variables.

| n (%) | M | SD | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Age | 29.62 | 5.90 | 19 | 45 | |

| 18–29 | 85 (55.6%) | ||||

| 30+ | 68 (44.4%) | ||||

| Ethnic identity (expressed as select all that apply) | |||||

| African | 10 (6.5%) | ||||

| Caribbean | 14 (9.2%) | ||||

| Afro-Latinx | 7 (4.6%) | ||||

| African American | 140 (91.5%) | ||||

| Other | 4 (2.6%) | ||||

| Sexual orientation | |||||

| Heterosexual | 121 (79.1%) | ||||

| Bisexual | 14 (9.2%) | ||||

| Gay/Lesbian | 5 (3.3%) | ||||

| Queer | 6 (3.9%) | ||||

| Pansexual | 7 (4.6%) | ||||

| Education | |||||

| Technical college | 4 (2.6%) | ||||

| Some college | 18 (11.8%) | ||||

| Bachelor’s Degree | 51 (33.3%) | ||||

| Graduate or professional degree | 80 (52.3%) | ||||

| Couple status | |||||

| Single | 81 (52.9%) | ||||

| In a relationship | 72 (47.1%) | ||||

| Gender of primary partner | |||||

| Male | 79 (51.6%) | ||||

| Female | 8 (5.2%) | ||||

| Non-binary | 1 (0.7%) | ||||

| Transgender (male to female) | 1 (0.7%) | ||||

| Cognitive response to pain | 2.01 | 1.09 | 1 | 4.86 | |

| Emotional response to pain | 1.80 | 0.78 | 1 | 4.07 | |

Procedure

In November of 2020, the research team conducted online recruitment (e.g., Instagram, Facebook, Twitter) using snowball sampling. Snowball sampling is a non-probability sampling technique allowing participants to engage in recruitment by sharing study materials with individuals meeting eligibility criteria (Johnson, 2014). Participants completed a 10–15-minute Qualtrics survey that included quantitative measures and open-ended qualitative questions about sexual pain and pleasure. In addition, they had the option to enter a raffle for a $25 gift card at the end of the survey. The raffle participants entered their email after the study, and a random number generator selected raffle winners.

Measures

The research team selected a convergent mixed-methods approach to answer the research questions. Convergent mixed-methods studies seek to compare quantitative and qualitative data collected simultaneously to draw conclusions (Creswell & Creswell, 2017). Quantitative measures informed research question one, and qualitative measures informed research question two.

Cognitive and emotional response to pain: quantitative measures

Demographics

Participants reported their age, sexual orientation, ethnic identity, relationship status, level of education, and gender of sexual partners. For this study, the research team dichotomized age and relationship status. The dichotomous age variable reflected women under 30 (0) and 30 and older (1), based on differences in women’s response to pain and coping at different developmental ages (Arnett, 2000). The dichotomous relationship status variable reflected single (0) and coupled (1). Coupled women included those who were married, in a relationship, or cohabiting. Single women were those who were single, divorced, widowed, dating, or ethically non-monogamous.

Cognitive and emotional responses to pain

Participants completed the Vulvar Pain Assessment Questionnaire (VPAQ; Dargie et al., 2017). The VPAQ evaluates biopsychosocial symptoms, responses, and factors that influence chronic vulvar pain. All responses were on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = Not At All to 5 = Very Much. The research team selected two of the four subscales for this study: cognitive response to pain and emotional response to pain. Emotional response to pain (15 items; α = 0.93) assessed how participants felt about their sexual pain. Example items included, “I feel bad about myself because of the pain” and “I feel that I am not a worthwhile person.” Higher scores reflect increased distressed feelings about sexual pain. Cognitive responses to pain (7 items; α = .94) assessed how often participants thought or worried about their sexual pain. Example items were, “I think or worry that people would think less of me because of my pain” and “I think or worry that my partner(s) might think I am sexually unresponsive.” Higher scores indicate increased thoughts or worry about sexual pain. According to Dargie et al. (2017) for both subscales, a mean score of 2.0 or greater demonstrated symptoms of greater significance, such that a person with at least a 2.0 rating experienced a higher intensity of cognitive and emotional responses. The authors suggested the 2.0 rating from preliminary norms based on mean scores. Scores below 2.0 are indicative of mild to no pain severity, “lower intensity of cognitive and emotional responses, and minimal interference in various life domains” to pain (p. 1593; see Dargie et al., 2017 for more details).

Analysis

Data were exported to SPSS 28 software (IBM Corp, 2021). The research team conducted a series of independent samples t-tests to answer research question one. Independent samples t-tests determine if there is a significant difference in the means of two separate groups (Mertler & Vannatta, 2016). The assumptions for independence, normality, and homogeneity of variance were met (Mertler & Vannatta, 2016).

Coping strategies: Qualitative measures

The qualitative portion of this study relied on 121 participant responses to an open-ended question: “What sexual activities have been the most useful to help you engage in sexual pleasure despite sexual pain?”

Analysis

The research team used thematic analysis supported by a constructivist research paradigm to understand how participants coped with sexual pain. Thematic analysis is a valuable qualitative technique for “identifying, analyzing and reporting patterns within data” (Braun & Clarke, 2006, p. 79). The authors completed a six-step process outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006). Step one entailed familiarization with the data by reading the open-ended responses and completing memos. After step one, the research team members individually revisited the data and generated initial codes using a deductive process guided by the proactive coping model. Next, the research team collapsed their individual codes identified in step two into themes and sub-themes. During step four, the research team presented and compared their individual themes. After establishing inter-rater reliability, the team agreed on themes and developed theme descriptions for step five. The qualitative report of this mixed-methods study was developed as the final step.

Data trustworthiness was established using criteria proposed by Nowell, Norris, White, and Moules (2017). Data credibility was established by triangulating open-ended responses with memos and content from weekly peer debriefing meetings. For transferability, the research team revisited codes for thick descriptions (Nowell et al., 2017). Thick descriptions ensure that qualitative themes and sub-themes are as detailed as possible to support study generalizability (Nowell et al., 2017). Finally, an audit or decision trail supported the dependability and confirmability of the qualitative results.

Subjectivities statement

The research team consisted of six Black (ethnically African American) cisgender women of heterosexual and queer identities who were all pre-menopausal and highly educated (i.e., two doctoral students, one doctoral candidate, and three PhDs). All research team members were from the rural south except for one who grew up in the northeast. Regarding relationship status, two were single, and four were coupled at the time of the study.

Results

Mean differences are presented in Table 2. Participants averaged a score of 2.01 (SD = 1.09) on cognitive response to pain and 1.80 (SD = 0.78) on emotional response to pain.

Table 2.

Mean differences for vulvar pain assessment.

| Age 18–29 | Age 30+ | t(df) | P | d | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Cognitive response | 1.77 | 0.99 | 2.22 | 1.13 | −2.64 (150) | .009*** | 0.43 |

| Emotional response | 1.58 | 0.64 | 1.97 | 0.84 | −3.29 (150.7) | .001*** | 0.53 |

| Single | Coupled | ||||||

| Cognitive response | 2.19 | 1.19 | 1.81 | 0.94 | 2.19 (147.8) | .030* | 0.04 |

| Emotional response | 1.81 | 0.78 | 1.78 | 0.78 | .238 (151) | .812 | 0.35 |

Age

An independent-samples t-test was conducted to compare emotional and cognitive responses to pain for participants who were younger than 30 and 30 or older (see Table 2). There was a significant difference in scores for participants younger than 30 (M = 2.22, SD = 1.13) and participants 30 and older (M = 1.77, SD = 0.99), such that participants under 30 had more intense cognitive responses to sexual pain, t(150) = −2.64, p = .009. Additionally, there was a significant difference in the scores for participants younger than 30 (M = 1.97, SD = 0.84) and participants 30 and older (M = 1.57, SD = 0.64), such that participants under 30 had more intense emotional responses to sexual pain, t(150.72) = −3.29, p = .001.

Relationship status

An independent-samples t-test was conducted to compare emotional and cognitive responses to pain for participants who were coupled and single (see Table 2). There was a significant difference in the scores for coupled participants (M = 1.81, SD = 0.94) and single participants (M = 2.19, SD = 1.19), such that coupled participants had less intense cognitive response to sexual pain, t(147.85) = 2.19, p = .03. There was not a significant difference between coupled and single participants in emotional responses to sexual pain. Chi-square analysis did not indicate a significant difference in relationship status based on age (i.e., under 30 or 30 and up); therefore, no relationship existed between these two variables.

Qualitative results

Next, we outline how participants coped with sexual pain. Qualitative findings revealed five proactive themes: non-penetrative sexual activities, foreplay, tools for increasing arousal, making physical adjustments, and intimacy and sexual communication. Additionally, passive coping emerged as a theme.

Non-penetrative sexual activities

The top coping strategy for sexual pain was engaging in non-penetrative sexual activities (n = 82 reports) when sexual pain occurs. Participants appreciated when their partners were open to non-penetrative sexual activities. For example, one participant said, “non-penetrative sex and being verbally assured by my partner that penetration never has to happen when we have sex” (age 29, in a relationship). Some participants relied on non-penetrative sexual activities more often, such as a participant who stated, “we don’t do penetrative sex often, especially close to the beginning or end of my period” (age 23, in a relationship). It is important to note this theme may have been more relevant to women engaging in sex with partners who had penises or used penetrative toys. A participant who had sex with women shared, “sexual contact with women is far less painful and any contact that does not involve penetration” (age 32, single).

The two most used non-penetrative coping activities, which participants considered foreplay, were oral sex and masturbation. Participants reported giving and receiving oral sex (n = 38 reports) as one of their most preferred ways to cope with sexual pain. Participants described oral sex as “oral” (age 31, married), “cunnilingus” (age 24, single), and “fellatio” (age 32, in a relationship). Additionally, participants frequently discussed “self-pleasure” through masturbation to cope with sexual pain (n = 16 reports). They described masturbation as “clitoral stimulation during masturbation” (age 29, married) and “mutual masturbation” (age 26, single).

Foreplay

Participants indicated “lots of foreplay” (age 27, in a relationship) was important when coping with sexual pain (n = 28 reports). Foreplay was essential for helping participants relax after experiencing sexual pain and had additional benefits. For example, one participant said, “heavy foreplay helps take away the emotional insecurities” (age 25, married). Participants reported a variety of foreplay activities including “massage” (age 30, single), “bodily kissing” (age 28, in a relationship), and “nipple stimulation” (age 31, in a relationship).

Tools for increasing arousal

The second most common coping strategy was tools for increasing arousal. Participants were resourceful and relied on various tools to increase arousal and decrease sexual pain (n = 25 reports). Examples of tools were lubricant, toys, porn, and alcohol. For example, participants shared, “I use [the] Use Your Mouth Card game™” (age 30, married), “using lube, using a vibrator over panties instead of it directly on the clitoris” (age 22, single), “drinking alcohol to relax and take my mind off of the pain that I may experience” (age 35, dating), and “small toys help a lot” (age 23, in a relationship). The most common arousal tools were toys (n = 13 reports) and using lubricant (n = 12 reports).

Making physical adjustments

Participants often coped with sexual pain by switching positions or intentionally building more arousal. The main physical adjustment participants made was switching positions to make penetration less painful (n = 10 reports). For example, “missionary and side positions as opposed to from the back” (age 24, single) alleviated sexual pain. For two participants, “sex positions where I am on top” (age 37, married) and “doggy style” (age 36, single) were helpful. In addition to switching positions, some participants discussed asking their partner to go slower (e.g., “having my partner go slow with no deep penetration” [age 39, cohabitating]) or be gentler with penetration (e.g., “penetration that is gentle” [age 26, single]).

Some participants used edging, or the practice of stopping orgasm moments before climax (Herbenick et al., 2018), to build more arousal (n = 20 reports). They felt building more arousal could ease sexual pain by increasing vaginal lubrication or helping them relax. Two participants provided insight into building more arousal stating, “asking my partner to perform acts that stimulate arousal in between periods of penetration” (age 25, dating) and “giving myself time to become aroused” (age 24, single).

Intimacy and sexual communication

Participants indicated intimacy and sexual communication with their partners as ways they coped with their sexual pain. Intimacy (n = 14 reports) was described as building emotional and physical closeness through “verbal communication” (age 24, single) or “cuddle time” (age 35, married). One participant stated, “emotional intimacy and my partner’s patience” (age 30, single) eased sexual pain. For another participant, “building trust and intimacy before having sex” (age 30, married) were important.

Regardin sexual communication for coping with pain (n = 9 reports), participants either communicated with their partners or with themselves. Participants demonstrated sexual communication when they voiced their discomfort to their partners. Intimate communication occurred when participants’ partners expressed their desire for them during sex. A participant captured both intimacy and sexual communication stating, “having my desirability expressed to me and communication [with my partner]” (age 23, single). Participant’s communication with themselves looked like a mindful commitment to enjoying sex despite sexual pain. For example, one participant said, “learning to enjoy pleasure in my body as a conscious choice” (age 44, single) was helpful. Another participant discussed “staying in the moment” (age 24, single).

Passive coping

Passive coping represented when participants were passive about their sexual pain. For example, some participants (n = 6 reports) did nothing to cope with their sexual pain (e.g., “nothing” [age 22, dating]). Other participants coped by “avoiding vaginal intercourse” (age 39, married), “ignoring it” (age 27, single) or focusing on their partner instead (e.g., “I usually just take care of my husband” [age 33, married]).

Discussion

With theoretical support from the proactive coping model, this mixed-methods study examined Black women’s cognitive and emotional responses to sexual pain and coping strategies. Younger Black women reported significantly more intense cognitive and emotional responses to sexual pain compared to their older counterparts. This finding is less surprising considering sexual pain may be highest among younger women (Donaldson & Meana, 2011). However, young Black women’s sociocultural context may provide a unique explanation for this study’s sample. Socioculturally, younger Black women may experience more pressure to fulfill specific sexual script roles while engaging in sex (Bowleg et al. 2015). For example, as part of the Freak script, Black women are expected to forgo reports of pain or discomfort to maintain a sexually aggressive and wild image and performance during sex (Bowleg et al. 2015). Pressure to fulfill the Freak sexual script, among others, may lead younger Black women to engage in more passive coping like ignoring sexual pain since proactive coping departs from the expectations the sexual scripts imposed on them at an early age. As a result, they likely experience increased cognitive response to pain and more negative emotions during sexual experiences.

Alternatively, older Black women may be less concerned about fulfilling sociocultural expectations imposed on them. They may be more willing to engage in proactive coping such as non-penetrative activities or making adjustments because they have overcome stereotypes and sexual scripts. Older Black women’s ability to depart from harmful sociocultural messaging combined with an increased ability to identify proactive coping strategies that work effectively with age (Maeng et al., 2017) likely informed less cognitive and emotional responses to pain.

Partner support has a critical role in the proactive coping model and may explain why coupled Black women reported less cognitive response to sexual pain than single Black women. This study did not measure if participants had receptive partners and received support from them to cope. However, intimacy and sexual communication emerged in the qualitative results as a proactive coping strategy the participants used with partners. Research indicates sexual pain intensity decreases with partner support and communication (Rosen et al., 2010). When women have supportive partners to help mitigate sexual pain, they are less likely to worry about their sexual pain (Rosen et al., 2010; Thomtén & Linton, 2013).

Partner gender likely also matters, as roughly 20% of the study’s sample identified as LGBQ. Same-gender relationships are reported to have greater flexibility in terms of sexual communication because LGBQ women may not endorse heteronormative sexual scripts as much as heterosexual women, which could lessen cognitive response to pain (Blair et al., 2015). Heteronormative scripts may influence heterosexual women to passively cope with pain due to the prioritization of vaginal-penile intercourse in their relationships (i.e., the coital imperative; Frith, 2013). On the contrary, based on the qualitative results, heterosexual women do engage in other forms of intercourse; yet, communicating about painful penetration could be harder to do with male partners. The combination of intimacy and sexual communication with partners may have informed lower cognitive responses among coupled Black women.

Coping with sexual pain

Six themes emerged from the qualitative data exploring Black women’s coping strategies: (1) engaging in non-penetrative sexual activities, (2) foreplay, (3) using tools for increasing arousal, (4) making physical adjustments, (5) intimacy and sexual communication, and (6) passive coping. Themes indicated that Black women identify primarily proactive coping strategies for navigating sexual pain. Findings also demonstrate Black women identify passive coping strategies, which may inform within-group differences warranting further examination.

Findings support the proactive coping model by showing participants arrive at experiences of sexual pain with proactive coping strategies available to implement. Additionally, many of the themes, such as intimacy and sexual communication, further demonstrated the role of social support in the proactive coping model. Proactive coping (e.g., cuddling) and social support (e.g., partner support) work together and lead to positive cognitive responses (Greenglass & Fiksenbaum, 2009). Intimacy and sexual communication with partners may also explain why coupled participants indicated less cognitive responses to sexual pain. However, while qualitative results indicate Black women are actively coping with their sexual pain, quantitative results do not indicate lower cognitive scores. It is possible Black women may be aware of proactive coping strategies for reducing sexual pain, but do not engage these strategies enough for them to work effectively. Additionally, since the sample’s emotional response scores were slightly lower on average, Black women’s current coping skills are possibly helping them emotionally, but not cognitively.

Passive coping among a small subsample of participants suggests some Black women are aware of their sexual pain but do not actively cope with it (e.g., participants reported that they did nothing to cope with their pain). However, some women chose to avoid adjusting when experiencing pain, minimized their pain, or focused on their partner instead. Often Black women are socialized to cater to the needs of others before themselves as part of gendered racial stereotypes (e.g., the Mammy; Collins, 2008; Lewis et al., 2016). As a result, their sexual pain may be secondary to their partner during sex. Additionally, Black women may be more reluctant to disclose their sexual pain if they believe it will solicit a negative response from their partner such as being labeled difficult or a bad sex partner (Thomtén & Linton, 2013). Additionally, Black women may be adhering to Strong Black Woman/Superwoman Schema through their reluctance to disclose their sexual pain to maintain an image of strength (Woods-Giscombé, 2010).

According to the proactive coping model, proactive coping strategies combined with social support are essential to developing positive cognitive and affective motivational states that facilitate positive outcomes (Greenglass & Fiksenbaum, 2009). When Black women do not cope with their sexual pain, they are predisposed to negative cognitive and emotional responses leading to adverse outcomes related to their pain. Therefore, for Black women to experience more positive cognitive and emotional outcomes related to their sexual pain, proactive coping and partner support must be emphasized as key components to reducing sexual pain.

Limitations

Although this study contributes to the literature, it is not without limitations. First, this was a convenience sample of highly educated Black women in the Southern US. Therefore, the results of this study may not be generalizable to Black women without college or technical training or reside in other regions of the US. Second, although there are benefits to providing participants with an open-ended question, future research should use a validated scale to triangulate qualitatively reported coping strategies (e.g., CHAMP Sexual Pain Coping Scale, Flink et al., 2015). For instance, the CHAMP coping scale measures avoidance, endurance, and alternative coping strategies that participants may not have mentioned in the current study. Third, this study did not examine differences in engagement coping strategies by age or relationship status, which presents a line of inquiry relevant for future studies. Additionally, partner support was not explored, nor were participants asked to describe how their partner supports them during sexual pain. However, coupled status was used as a proxy measure or potential indicator of partner support. More research on partner support is needed to clearly understand how partner support influences Black women’s sexual experiences. Finally, more research on Black queer women is needed to determine how experiences of sexual pain differ or are similar as a result of being in a same-sex relationship.

Implications

Overall, this study provides implications for sex therapists and counselors working with Black women clients experiencing recurring sexual pain in the absence of pathology. Despite the prevalence of sexual pain concerns among Black women, few seek treatment (Labuski, 2017). While it is possible Black women do not seek treatment due to comfort with partners or having more sexual experience, barriers such as cost, lack of familiarity with treatment, or provider mistrust may also influence their decision to forego visiting a provider (Wilson, 2016). In addition to increasing cultural competency and understanding barriers to treatment, sexual health professionals should complete intentional outreach to Black women.

Sex therapists and counselors should focus on building proactive coping strategy toolkits for Black women experiencing sexual pain. Although proactive coping strategies can have a positive impact on Black women’s psychological and emotional health, Black women should refrain from engaging in solely proactive strategies without leaning into their social support. The constant anticipation of stressors and overuse of proactive coping strategies could result in Black women adhering to the Superwoman Schema (Woods-Giscombé, 2010), by feeling the need to cope with their pain by themselves and exhibit unwavering strength and resilience despite their pain and access to social support. Social supports such as partners or other Black women may buffer against Black women’s engagement in proactive coping to the point of endorsing Superwoman Schema or other cultural scripts.

These findings also highlight the importance of including partners in the coping and treatment process. Research has shown that when male partners are knowledgeable about sexual pain disorders and the impact it has on their female partners and their relationship, they develop higher self-efficacy to cope and assist their partner (Sadownik, Smith, Hui, & Brotto, 2017). However, little research has been conducted on the role of same-sex partners in coping with sexual pain. Since women are more likely to understand each other’s bodies there may be more empathy and sexual communication in these relationships, thus creating safe spaces for women to lean into their partner for support (Blair et al., 2015). Because sexual pain can cause psychological distress for both partners and result in negative emotions such as anger, anxiety, and frustration (Sadownik et al., 2017), it is important for couples to go to sex therapy and engage in open and clear communication about their experiences. Black women need to feel comfortable expressing their concerns to their partners and their partners need healthy ways to cope with these experiences so they can be supportive.

Conclusion

Sexual pain can hinder Black women’s sexual wellness. More specifically, overwhelming cognitive and emotional responses to sexual pain can negatively influence women’s sexual desire and arousal and decrease overall sexual satisfaction. Whereas younger Black women reported more cognitive and emotional responses to sexual pain, women over 30 did not. Additionally, women in relationships reported less cognitive responses to sexual pain. Overall, soliciting social support through sexual communication with partners and engaging in proactive coping strategies such as non-penetrative sexual activities and supplemental tools seems to enhance sexual pleasure and reduce sexual pain among this group. Black women who report a lack of coping strategies are especially important targets for interventions to mitigate sexual pain. Our study substantiates the need to promote and continue establishing proactive coping strategies related to Black women’s sexual pain given the prevalence of sexual pain in this population (Townes et al., 2019) and experiences of misdiagnosis (Harlow & Stewart, 2003).

Funding

Funding was provided, in part, by the Lyman T. Johnson Postdoctoral Fellowship (Dr. Shemeka Thorpe: PI).

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Al-Abbadey M, Liossi C, Curran N, Schoth DE, & Graham CA (2016). Treatment of female sexual pain disorders: A systematic review. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 42(2), 99–142. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2015.1053023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair KL, Pukall CF, Smith KB, & Cappell J (2015). Differential associations of communication and love in heterosexual, lesbian, and bisexual women’s perceptions and experiences of chronic vulvar and pelvic pain. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 41(5), 498–524. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2014.931315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bougie O, Yap MI, Sikora L, Flaxman T, & Singh S (2019). Influence of race/ethnicity on prevalence and presentation of endometriosis: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 126(9), 1104–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2018.09.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L, Burkholder GJ, Noar SM, Teti M, Malebranche DJ, & Tschann JM (2015). Sexual scripts and sexual risk behaviors among Black heterosexual men: Development of the Sexual Scripts Scale. Archives of sexual behavior, 44(3), 639–654. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0193-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, & Clarke V (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter A, Ford JV, Luetke M, Fu TJ, Townes A, Hensel DJ, Dodge B, & Herbenick D (2019). “Fulfilling His Needs, Not Mine”: Reasons for not talking about painful sex and associations with lack of pleasure in a nationally representative sample of women in the United States. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 16(12), 1953–1965. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins PH (2008). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. London, UK: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW, & Creswell JD (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Dargie E, Holden R, & Pukall C (2017). The Vulvar Pain Assessment Questionnaire: Factor structure, preliminary norms, internal consistency, and test-retest reliability. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 14, 1585–1596. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2017.10.072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Graaff AA, Van Lankveld J, Smits LJ, Van Beek JJ, & Dunselman GAJ (2016). Dyspareunia and depressive symptoms are associated with impaired sexual functioning in women with endometriosis, whereas sexual functioning in their male partners is not affected. Human Reproduction, 31(11), 2577–2586. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson RL, & Meana M (2011). Early dyspareunia experience in young women: Confusion, consequences, and help-seeking barriers. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 8(3), 814–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flink IK, Thomtén J, Engman L, Hedström S, & Linton SJ (2015). Coping with painful sex: Development and initial validation of the CHAMP sexual pain coping scale. Scandinavian Journal of Pain, 9(1), 74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.sjpain.2015.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith H (2013). Labouring on orgasms: Embodiment, efficiency, entitlement and obligations in heterosex. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 15(4), 494–510. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2013.767940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuldeore MJ, & Soliman AM (2017). Prevalence and symptomatic burden of diagnosed endometriosis in the United States: National estimates from a cross-sectional survey of 59,411 women. Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation, 82(5), 453–461. doi: 10.1159/000452660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenglass ER, & Fiksenbaum L (2009). Proactive coping, positive affect, and well-being: Testing for mediation using path analysis. European Psychologist, 14(1), 29–39. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040.14.1.29 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hargons CN, Dogan J, Malone N, Thorpe S, Mosley DV, & Stevens-Watkins D (2020). Balancing the sexology scales: A content analysis of Black women’s sexuality research. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 23(2), 1–15. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2020.1776399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow BL, & Stewart EG (2003). A population-based assessment of chronic unexplained vulvar pain: Have we underestimated the prevalence of vulvodynia? Journal of the American Medical Women’s Association (1972), 58(2), 82–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbenick D, Fu TC, Arter J, Sanders SA, & Dodge B (2018). Women’s experiences with genital touching, sexual pleasure, and orgasm: Results from a US probability sample of women ages 18 to 94. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 44(2), 201–212. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2017.1346530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman KM, Trawalter S, Axt JR, & Oliver MN (2016). Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between Blacks and Whites. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(16), 4296–4301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1516047113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. (2021). SPSS for Macbook, version 28. Chicago, IL: SPSS Inc. [Computer software]. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TP (2014). Snowball sampling: Introduction. In Balakrishnan N, Colton T, Everitt B, Piegorsch W, Ruggeri F & Teugels JL (Eds.), Wiley statsRef: Statistics reference online. Retrieved from 10.1002/9781118445112.stat05720 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RE, & Lopez KH (2013). Human reproductive biology. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Labuski CM (2017). A Black and White issue? Learning to see the intersectional and racialized dimensions of gynecological pain. Social Theory & Health, 15(2), 160–181. doi: 10.1057/s41285-017-0027-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JA, Mendenhall R, Harwood SA, & Browne Huntt M (2016). “Ain’t I a woman?” Perceived gendered racial microaggressions experienced by Black women. The Counseling Psychologist, 44(5), 758–780. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1177/0011000016641193 doi: 10.1177/0011000016641193 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maeng S, Oh H, Song M, Kim Y, Cha S, Bae J, … & Sohn N (2017). Changes in coping strategy with age. Innovation in Aging, 1(Suppl 1), 897. 10.1093/geroni/Figx004.3218 doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mertler CA, & Vannatta RA (2016). Advanced and multivariate statistical methods: Practical application and interpretation. Abingdon, UK: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Mossey JM (2011). Defining racial and ethnic disparities in pain management. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 469(7), 1859–1870. 10.1007/s11999-011-1770-9 doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1770-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, & Moules NJ (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1–13. doi: 10.1177/1609406917733847 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orr N, Wahl K, Joannou A, Hartmann D, Valle L, Yong P, … & Renzelli-Cain RI (2020). Deep dyspareunia: Review of pathophysiology and proposed future research priorities. Sexual Medicine Reviews, 8(1), 3–17. doi: 10.1016/j.sxmr.2018.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paine EA, Umberson D, & Reczek C (2019). Sex in midlife: Women’s sexual experiences in lesbian and straight marriages. Journal of marriage and the family, 81(1), 7–23. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pazmany E, Bergeron S, Verhaeghe J, Van Oudenhove L, & Enzlin P (2014). Sexual communication, dyadic adjustment, and psychosexual well-being in premenopausal women with self-reported dyspareunia and their partners: A controlled study. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 11(7), 1786–1797. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen NO, Bergeron S, Leclerc B, Lambert B, & Steben M (2010). Woman and partner-perceived partner responses predict pain and sexual satisfaction in provoked vestibulodynia (PVD) couples. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7(11), 3715–3724. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01957.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabin Janice A. (2020, January 6). How we fail Black patients in pain. AAMC. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/how-we-fail-black-patients-pain [Google Scholar]

- Sadownik LA, Smith KB, Hui A, & Brotto LA (2017). The impact of a woman’s dyspareunia and its treatment on her intimate partner: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 43(6), 529–542. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2016.1208697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider MP, Vitonis AF, Fadayomi AB, Charlton BM, Missmer SA, & DiVasta AD (2020). Quality of life in adolescent and young adult women with dyspareunia and endometriosis. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(4), 557–561. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.02.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seehusen DA, Baird D, & Bode DV (2014). Dyspareunia in women. American Family Physician, 90(7), 465–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobecki-Rausch JN, Brown O, & Gaupp CL (2017). Sexual dysfunction in lesbian women: A systematic review of the literature. In Seminars in reproductive medicine (Vol. 35, No. 5, pp. 448–459). New York, NY: Thieme Medical Publishers. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1604455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanisławski K (2019). The coping circumplex model: An integrative model of the structure of coping with stress. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 694. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens DP, & Phillips LD (2003). Freaks, gold diggers, divas, and dykes: The sociohistorical development of adolescent African American women’s sexual scripts. Sexuality and culture, 7(1), 3–49. doi: 10.1007/BF03159848 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tayyeb M, & Gupta V (2020). Dyspareunia. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls; [Internet]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomtén J, & Linton SJ (2013). A psychological view of sexual pain among women: Applying the fear-avoidance model. Womens Health, 9(3), 251–263. doi: 10.2217/whe.13.19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townes A, Fu T, Herbenick D, & Carter A (2019). Painful sex among White and Black women in the United States: Results from a nationally representative study. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 16(6), S26. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.03.512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vercellini P, Somigliana E, Buggio L, Barbara G, Frattaruolo MP, & Fedele L (2012). “I can’t get no satisfaction”: Deep dyspareunia and sexual functioning in women with rectovaginal endometriosis. Fertility and Sterility, 98(6), 1503–1511. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.07.1129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware S, Thorpe S, & Tanner AE (2019). Sexual health interventions for Black women in the United States: A systematic review of literature. International Journal of Sexual Health, 31(2), 196–215. doi: 10.1080/19317611.2019.1613278 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wells L, & Gowda A (2020). A legacy of mistrust: African Americans and the US healthcare system. Proceedings of UCLA Health, 24, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson J (2016). Who’s coming to sex therapy? Exploring Black Women’s willingness to seek treatment for sexual problems/dysfunctions. (Electronic Thesis or Dissertation). Retrieved from https://etd.ohiolink.edu/ [Google Scholar]

- Witzeman K, Flores OA, Renzelli-Cain RI, Worly B, Moulder JK, Carrillo JF, & Schneider B (2020). Patient-physician interactions regarding dyspareunia with endometriosis: Online survey results. Journal of Pain Research, 13, 1579. doi: 10.1097/01.aog.0000559306.07093.6a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods-Giscombé CL (2010). Superwoman schema: African American women’s views on stress, strength, and health. Qualitative Health Research, 20(5), 668–683. doi: 10.1177/1049732310361892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yong PJ, Mui J, Allaire C, & Williams C (2014). Pelvic floor tenderness in the etiology of superficial dyspareunia. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada, 36(11), 1002–1009. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(15)30414-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]