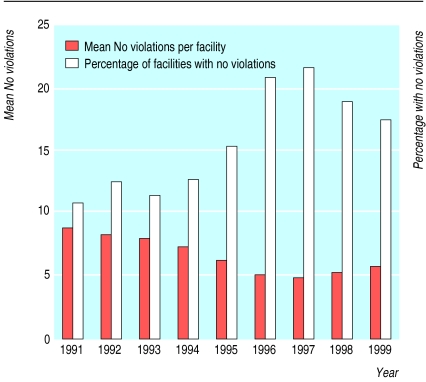

Poor quality care has been an enduring feature of many of the 16 500 residential nursing facilities that provide care to 1.6 million people in the United States.1 Despite three decades of public concern, government surveys and data collected by the federal government continue to show that residents of nursing homes experience problems in their care (figure). In 1998 and 1999, 25-33% of nursing homes had serious or potentially life threatening problems in delivering care and were harming residents.3,4 In 1999, state inspectors found that 26% of the nation's nursing facilities had poor food hygiene; 21% provided care that was inadequate; 19% had environments that contributed to injuries in residents; and in 18% pressure sores were treated improperly. The eight most common deficiencies identified in 1999 are shown in the box.2 About 77% of facilities that were performing poorly had problems in subsequent surveys conducted by state licensing and certification agencies.2

Summary points

Poor quality care for the 1.6 million people in nursing homes in the United States has existed for 25 years

Care in as many as one third of nursing homes jeopardises the health and safety of residents

The largely profit making nursing home industry provides fewer nurses and poorer quality of care than non-profit homes and government run nursing homes

A fundamental cause of poor care is the low number of nurses and other staff required by law

Monitoring and enforcement of quality standards, which has been devolved to the states, has been weak because standards are lax

The US government has failed to hold the nursing home industry accountable for how government funds are spent and to protect residents from poor care

Between 1993 and 1999, there was an increase in the number of residents developing contractures, pressure sores, and incontinence; being bedbound; and receiving psychotropic drugs.2 In a study of nursing home residents who had died, more than half had received unacceptable care that endangered their health or safety; this care included failure to properly treat pressure sores, failure to manage pain, and some had had a dramatic, unplanned loss of weight.4 Given the scale and chronic nature of quality of care issues and the failures in resolving them, what can the United Kingdom learn from the experiences of the United States?

Ownership and quality of care

Of the nursing homes for older people in the United States, 67% are run by profit making organisations, and 52% are part of an organisation that owns more than one facility.2 The six largest providers of residential care in the United States also own a large number of facilities internationally.1 The table shows the companies that own the greatest number of facilities. Sun Healthcare Group, one of the largest companies, had revenues of $2.5bn (£1.8bn) in 1999, and operated 145 long term care facilities with 8320 beds in the United Kingdom, had 1640 licensed beds in Spain, 3339 in Australia, and 1217 in Germany.5 It also owned hospitals, pharmacies, providers of rehabilitation services, and respiratory therapy services.

Non-profit nursing homes are associated with better staffing and higher quality services6 as well as with residents having a lower probability of death and infection.7 Facilities owned by investors have fewer nurses and higher rates of violations, or deficiencies, on annual surveys of nursing homes.8,9 Profit making facilities were found to have 30% more violations of standards assessing quality of care and more deficiencies in measures assessing quality of life than non-profit facilities.9

Not surprisingly, litigation is increasing. In 2000, the Supreme Court of Texas upheld an $11m judgment against the Horizon Health Care Corporation for the death of a resident.10 In Florida, Extendicare, another nursing home operator, was fined $17m in punitive damages and $3m in compensation for negligent care.11

Federal regulation

Under federal regulations, each state has a licensing and certification agency that inspects facilities that have a contract with the federal government. This is analogous to regulations in the Care Standards Act 2000 in the United Kingdom except that in the United Kingdom a central agency handles inspection and enforcement; this will be discussed in the third paper in the series.12 In the United States, federal regulations require each nursing facility to conduct standardised, comprehensive assessments of all patients when they are admitted and periodically thereafter and to implement care plans that meet the individual needs of residents.

The survey, which is carried out by state agencies, requires that residents be interviewed or assessed and that observations be made to evaluate whether some 185 quality requirements (in 17 different categories) and “life safety” requirements have been met. The surveys examine both the process and the outcomes of care to ensure that minimum standards are met.13 Data on compliance with regulations and the characteristics of individual nursing homes are collected centrally and published on the internet, where they are available to the public.

The 1987 law established new enforcement procedures that use intermediate sanctions (penalties that fall short of closing nursing homes) against facilities that fail to meet federal standards14; these sanctions include the ability to issue fines, deny payment for newly admitted residents, and bring in managers from outside. If these sanctions are not effective, the federal government can issue a notice of immediate termination and decertification—that is, withdraw federal payments. The intermediate sanctions, however, were not implemented until 1995.

Reform of regulations

Prompted by scandals in care in nursing homes, the US Senate Special Committee on Aging held a series of hearings between 1963 and 1974. These led to reform of the federal and state laws regulating nursing facilities.15,16 When the Reagan administration attempted to deregulate the nursing home industry in 1982, Congress asked the Institute of Medicine to study the regulations. The institute's report showed that there were widespread problems in the quality of care provided17; Congress's investigative agency, the General Accounting Office, also issued a report. The office's report found that over one third of the nation's nursing homes did not meet federal standards.18 In 1987, Congress passed a bill, the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987, that brought important reforms to the regulation of nursing homes. This act established federal regulations for all facilities serving clients whose care was publicly funded, such as those on Medicare (which pays for care for elderly people and disabled people) and Medicaid (which pays for care for poor people). The federal regulations have three parts: the standards, the survey or monitoring procedures, and the enforcement procedures.

Staffing

Two of the fundamental causes of problems with the quality of care in US nursing homes are inadequate staffing and a poor mix of skills. Federal regulations require only that one registered nurse is on duty eight hours a day for seven days a week and that a registered nurse or a licensed practical nurse (also known as a licensed vocational nurse) is on duty during other shifts regardless of the size of the facility.2 (Registered nurses have between two and four years of training and licensed practical nurses have one year of training.) Numerous studies have recommended that standards for staffing should be higher14,19,20 and have found enormous variation in staffing within and across states.14,20

Most common violations found in US nursing homes, 19992

| Violation | Percentage of facilities |

| Improper use of restraints | 11 |

| Inadequate care plans | 13 |

| Inadequate attention to activities of daily living | 14 |

| Respect for personal autonomy and privacy | 16 |

| Improper care of pressure sores | 18 |

| Unsafe environment that contributes to injuries | 19 |

| Poor quality of care | 21 |

| Inadequate food hygiene | 26 |

Amount of time nurses spend in nursing homes per resident per day, 19992

Registered nurses—124 minutes

Licensed vocational nurses—42 minutes

Nursing assistants—44 minutes

On average, nursing assistants care for 12 residents, and registered nurses and licensed vocational nurses oversee 32 to 34 residents.2,20 Since nursing facilities report on their own staffing levels, these levels may actually be lower than reported, and facilities commonly increase the number of staff during surveys.14 Profit making facilities have 20% fewer staff than non-profit and government run facilities. Poor quality care in nursing homes is associated with low wages and few benefits, high rates of employee turnover, and heavy workloads.21

Many states have proposed legislative changes to increase the number of staff required in nursing homes (for example, in 1999 California passed legislation requiring a total of 3.2 hours of direct care for each resident each day). In 2000 President Clinton proposed allocating $1bn in new funds for staffing for nursing homes so that states could voluntarily address staffing problems.22 Additionally, legislation was introduced in the Senate, through the Nursing Home Improvement Act 2000, to require the Health Care Financing Administration (a government agency responsible for administering public funds for Medicare and Medicaid) to set minimum staffing requirements for nurses and to boost staffing in nursing facilities by spending $1bn over two years. There is growing concern, however, that the Health Care Financing Administration will not increase the minimum levels to those that are necessary to ensure quality because of the high cost to government of setting higher standards, in terms of funding for Medicare and Medicaid.

Enforcement

The weakness of the standards on staffing is made worse by an ineffective system of survey and enforcement in which responsibility is devolved to the states. Those who do the surveys are responsible for visiting nursing facilities every 9 to 15 months to conduct surveys and investigate complaints.13 The General Accounting Office has found that those conducting surveys are unable to detect serious problems in the quality of care particularly in terms of the number of preventable hospitalisations, deaths, falls that led to fractures, and infections and pressure, as well as the inappropriate use of restraints, the failure to dress and groom residents, and malnutrition.3,4

At the 1998 hearings of the US Senate Special Committee on Aging, which examined the General Accounting Office's findings, the committee criticised the Health Care Financing Administration's survey and enforcement efforts, and President Clinton announced a new initiative to improve the enforcement process by introducing stronger oversight of state inspections.23

Reimbursement

The government's payment policies are important to the nursing home industry: they account for 62% of the $87bn earned in revenue by nursing homes in l998.24,25 Under the federal Medicare prospective payment system (which covers short term care for elderly people and disabled people), reimbursement to nursing homes is made on the basis of the estimated amount of staff time and the skill mix needed to care for each resident, but facilities are under no obligation to provide the staff time for which they are paid or to provide care that exceeds minimum standards. Medicare payments (which were $264-385 per resident per day in 1999)1 and payments by private payers, which are the same for profit making, non-profit, and governmental facilities, are significantly higher than payments made by Medicaid (about $95 per day in 1998). Medicaid pays for 54% of the total number of private and public expenditures.

The low level of federal payments and state Medicaid payments are major deterrents to nursing homes increasing staffing.25 It has been estimated that increasing the total average time spent with a resident from 3.5 hours per resident per day to 4.55 hours per day would cost at least $6bn.25

The lack of government control over public funds is a cause for concern. Currently, less than 36 cents in every dollar spent on nursing facilities is spent directly on care.26 No limits are set on the amount of returns that can be allocated to shareholders, on salaries for chief executive officers, or on spending on capital and administrative costs. Robert Elkins, the former chief executive officer and founder of Integrated Health Systems (which runs a large number of nursing homes whose stock value dropped by 78% between 1997 and 1999) made over $14m in salary and stock bonuses annually27 and received a package worth $55m when he left the company.27

Financial fraud is not uncommon because there are no strong mechanisms of accountability for spending public funds. Beverly Enterprises, which runs the nation's largest chain of nursing homes (561 facilities in 30 states) has agreed to pay $175m to settle US Department of Justice charges of defrauding Medicare of $460m between 1992 and 1998; employees were found to have fabricated records to make it appear that nurses were devoting more time to Medicare patients than they actually were.28 Vencor, another operator of nursing homes, settled a fraud case brought by the government for $1.3bn and agreed to have an independent monitor for five years to ensure that quality standards are maintained and fraud is avoided.29

When Congress passed a new prospective payment system for Medicare in 1997, which used the case mix of residents (known as acuity) to control spending on care in nursing homes,30 some 2000 of the companies running the largest number of nursing homes filed for bankruptcy.31 Among them were Sun Healthcare Group, which reported losses of $700m in 1998 and $90m in 1999, and Vencor, which reported losses of $563m in 1998 and $612m in 1999.31 Sun Healthcare Group sold its holdings in the United Kingdom to management for $1 in a buyout and then reduced their workforce from 80 700 in 1999 to 57 100 in 2000.5

Although these corporations blamed Medicare's payment policies for their losses, the General Accounting Office found little evidence to support this, instead ascribing the companies' financial difficulties to “high capital-related costs” and substantial non-recurring expenses and write offs.32 Nonetheless, the nursing home industry was successful in its lobbying, and in 2000 Congress and the president implemented the Benefits Improvement and Protection Act which restored many of the cuts made to Medicare reimbursement.

Lessons for the United Kingdom

Over the past three decades, the poor quality of care in nursing homes in the United States has continued to be a problem. The nursing home industry is increasingly controlled by large and politically powerful multinational corporations. These corporations have wide discretion over the spending of large amounts of public funds, but at the same time there is little financial accountability. Fraud and financial mismanagement are widespread throughout the industry as is poor quality care.

Although strong federal quality standards were established by law in 1987, the crucially important standards for staffing continue to be weak; staffing accounts for the largest share of the cost of care. Small numbers of staff, who are paid low wages and have few benefits, and high turnover rates are recognised features of the industry. The delayed implementation of enforcement and the weak sanctions available have yet to improve care because state survey systems are weak and government regulatory bodies are subject to lobbying by the industry. There is also a reluctance to use the enforcement penalties and sanctions available.

The government is reluctant to impose higher standards for staffing because of concerns over cost. Although the government pays 62% of nursing home bills,24 financial accountability for expenditure does not extend to rules governing the services to be provided, the types of services, how much profit can be made, and how much is spent on administrative costs and other expenditures.

The story of long term care in the United States holds lessons for the United Kingdom. Because the market is increasingly dominated by profit making corporate providers, the government must be prepared to intervene in areas that affect profit margins and must also retain control over the expenditures of providers in the areas of staffing, skill mix, training, and services provided. Failure to do this leaves regulation in the realm of symbolism and vulnerable, frail elderly people at risk of serious harm.

Figure.

Violations of care standards in nursing homes in the United States, 1991-92

Table.

Characteristics of the six largest corporations running nursing homes in the United States, 19991

| Company (headquarters) | No of beds | No of facilities | Revenue*

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of funds from federal and state governments | Total operating revenue | |||

| Beverly Enterprises (Fort Smith, Arizona) | 62 293 | 562 | 74 | $2.8bn |

| Mariner Post-Acute Network (Atlanta, Georgia) | 49 656 | 416 | 67 | $1.5bn |

| HCR Manor Care (Toledo, Ohio) | 47 138 | 297 | 51 | $2.2bn |

| Sun Healthcare Group (Albuquerque, New Mexico) | 44 941 | 397 | 83 | $2.5bn5 |

| Integrated Health Services (Owning Mills, Maryland) | 44 302 | 380 | 56 | $3bn |

| Vencor (Louisville, Kentucky) | 38 362 | 291 | 60 | $3bn |

$1.40=£1.00.

This is the second in a series of three articles

Footnotes

Series editors: Allyson M Pollock, Susan H Kerrison

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.American Health Care Association. Facts and trends 1999: the nursing facility sourcebook. Washington, DC: AHCA; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harrington C, Carrillo H, Thollaug S, Summers P. Nursing facilities, staffing, residents, and facility deficiencies, 1993-99. San Francisco: University of California; 2000. www.hcfa.gov/medicaid/ltchomep.htm . (Available at www.hcfa.gov/medicaid/ltchomep.htm.) .) [Google Scholar]

- 3.US General Accounting Office. California nursing homes: care problems persist despite federal and state oversight. Washington, DC: GAO; 1998. . (Report to the Special Committee on Aging, US Senate. GAO/HEHS-98-202.) [Google Scholar]

- 4.US General Accounting Office. Nursing homes: additional steps needed to strengthen enforcement of federal quality standards. Washington, DC: GAO; 1999. . (Report to the Special Committee on Aging, US Senate. GAO/HEHS-99-46.) [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Securities and Exchange Commission. SUN Healthcare Group Inc. Annual Report for FY ended December 31, 1999. Washington, DC: SEC; 2001. . (No 1-12040.) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aaronson WE, Zinn JS, Rosko MD. Do for-profit and not-for-profit nursing homes behave differently? Gerontologist. 1994;34:775–786. doi: 10.1093/geront/34.6.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spector WD, Seldon TM, Cohen JW. The impact of ownership type on nursing home outcomes. Health Economics. 1998;7:639–653. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1050(1998110)7:7<639::aid-hec373>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harrington C, Woolhandler S, Mullan J, Carrillo H, Himmelstein D. Does investor-ownership of nursing homes compromise the quality of care? Am J Public Health (in press.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Harrington C, Zimmerman D, Karon SL, Robinson J, Beutel P. Nursing home staffing and its relationship to deficiencies. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2000;55B:S278–S286. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.5.s278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Supreme Court upholds $11 million Horizon judgment. McKnight's Long-Term Care News. 2000;22:14. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Extendicare says it will appeal $20 million lawsuit. McKnight's Long-Term Care News. 2000;22:14. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kerrison SH, Pollock AM. Regulating the quality of nursing care for older people in the private sector. BMJ (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.US Department of Health and Human Services; Health Care Financing Administration. 2001 state operations manual. Provider certification. Washington, DC: DHHS; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 14.US Health Care Financing Administration. Report to Congress: appropriateness of minimum nurse staffing ratios in nursing homes. 1-3. Baltimore, MD: HCFA; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 15.US Senate Special Committee on Aging. Nursing home care in the US: failure in public policy. Washington, DC: US Senate; 1974. . (Supporting paper No. 11.) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vladeck B. Unloving care: the nursing home tragedy. New York: Basic Books; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Institute of Medicine; Committee on the adequacy of nurse staffing in hospitals and nursing homes. Nursing staff in hospitals and nursing homes: is it adequate? Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 18.US General Accounting Office. Medicare and Medicaid: stronger enforcement of nursing home requirements needed. Washington, DC: GAO; 1987. . (Report to the chairman, Subcommittee on Health and Long-Term Care, Select Committee on Aging, House of Representatives.) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wunderlich GS, Sloan FA . Nursing staff in hospitals and nursing homes: is it adequate? Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1996. , Davis CK, for the Institute of Medicine, Committee on the Adequacy of Nurse Staffing in Hospitals and Nursing Homes. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harrington C, Kovner C, Mezey M, Kayser-Jones J, Burger S, Mohler M, et al. Experts recommend minimum nurse staffing standards for nursing facilities in the United States. Gerontologist. 2000;40:5–16. doi: 10.1093/geront/40.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen JW, Spector WD. The effect of Medicaid reimbursement on quality of care in nursing homes. J Health Econ. 1996;15:23–28. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(95)00030-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pear R. President asks for more aid for elder care. New York Times 2000 September 9:A26.

- 23.US Department of Health and Human Services. Assuring the quality of nursing home care. Washington, DC: Health Care Financing Administration; 1998. . (HHS fact sheet.) [Google Scholar]

- 24.US Health Care Financing Administration. National health expenditures 1960-1998. Washington, DC: HCFA; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wunderlich GS, Kohler P, editors. Improving the quality of long-term care. Wshington, DC: National Academies of Science; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.HCIA, Arthur Andersen. 1998-99: the guide to the nursing home industry. Baltimore, MD: HCIA, Arthur Andersen; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nursing home CEO gets departure deal: Elkins led IHS chain to boom, bankruptcy. Baltimore Sun 2001 January 13:10C.

- 28.Hilzenrath DS. Nursing home firm settles fraud case. Washington Post 2000 Feb 4:G3.

- 29.Vencor agrees to improve standards. McKnight's Long-Term Care News. 2000;21:6. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Medicare program; prospective payment system and consolidated billing for skilled nursing facilities. Federal Register. 1998. p. 63. (228):65561-2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakhnikian E. Long term care provider.com extends its bankruptcy coverage. www.longtermcareprovider.com. (Accessed 6 April 2001.)

- 32.US General Accounting Office. Skilled nursing facilities: Medicare payment changes require provider adjustments but maintain access. Washington, DC: GAO; 1999. . (Report to the Special Committee on Aging, US Senate. GAO/HEHS-00-23.) [Google Scholar]