Abstract

Introduction

Traditionally, plate osteosynthesis of the anterior column combined with an antegrade posterior column screw is used for fixation of anterior column plus posterior hemitransverse (ACPHT) acetabulum fractures. Replacing the posterior column screw with an infraacetabular screw could improve the straightforwardness of acetabulum surgery, as it can be inserted using less invasive approaches, such as the AIP/Stoppa approach, which is a well-established standard approach. However, the biomechanical stability of a plate osteosynthesis combined with an infraacetabular screw instead of an antegrade posterior column screw is unknown.

Material and methods

Two osteosynthesis constructs were compared in a synthetic hemipelvis model with an ACPHT fracture: Suprapectineal plate + antegrade posterior column screw (APCS group) vs. suprapectineal plate + infraacetabular screw (IAS group). A single-leg stance test protocol with an additional passive muscle force and a cyclic loading of 32,000 cycles with a maximum effective load of 2400 N was applied. Interfragmentary motion and rotation of the three main fracture lines were measured.

Results

At the posterior hemitransverse fracture line, interfragmentary motion perpendicular to the fracture line (p < 0.001) and shear motion (p < 0.001) and at the high anterior column fracture line, interfragmentary motion longitudinal to the fracture line (p = 0.017) were significantly higher in the IAS group than in the APCS group. On the other hand, interfragmentary motion perpendicular (p = 0.004), longitudinal (p < 0.001) and horizontal to the fracture line (p = 0.004) and shear motion (p < 0.001) were significantly increased at the low anterior column fracture line in the APCS group compared to the IAS group.

Conclusions

Replacing the antegrade posterior column screw with an infraacetabular screw is not recommendable as it results in an increased interfragmentary motion, especially at the posterior hemitransverse component of an ACPHT fracture.

Keywords: Acetabulum fracture, Anterior column plus posterior hemitransverse fracture, Antegrade posterior column screw, Infraacetabular screw, Suprapectineal plate, Biomechanical testing

Introduction

The incidence of acetabulum fractures in Germany raised from 2009 to 2019 by + 58% due to an aging society with a higher risk of fragility- and osteoporosis-associated fractures [1, 2]. Especially in elderly patients, the main trauma mechanism for acetabulum fractures is a ground-level fall on the greater trochanter resulting in an anterior column type fracture frequently associated with a posterior hemitransverse fracture line, a so-called anterior column plus posterior hemitransverse (ACPHT) fracture [2–7].

The incidence of a posttraumatic osteoarthritis after surgically treated acetabulum fractures is up to 30% [8–10]. An exact anatomical reduction and a biomechanically stable osteosynthesis are crucial for the survival of the hip joint, since they are the main predictors for clinical and radiological outcome of acetabulum fractures [8, 11–13]. Especially in geriatric patients with osteoporotic bone, a biomechanically stable osteosynthesis was found to be important for the radiological outcome [7]. Additionally in elderly patients, a biomechanically stable fracture fixation is important to ensure early mobilization to prevent immobilization-associated complications and mortality [14–16].

The surgical treatment of ACPHT fractures usually requires open reduction and internal stabilization of both columns [17]. Traditionally, fixation of the anterior column is performed by plate and screw osteosyntheses and fixation of the posterior column by an antegrade posterior column screw via an ilioinguinal approach as a standard [18–24]. In the last few years, a trend towards less invasive techniques in acetabular fracture surgery could be observed [25–28]. The use of less invasive approaches has been proven to be beneficial, especially in geriatric patients, which is why the ilioinguinal approach has been replaced by the modified Stoppa (AIP) approach as well as the Pararectus approach [18, 23, 25, 28–32]. However, the implantation of an antegrade posterior column screw requires an additional small incision to the first ilioinguinal window, if the plate osteosynthesis is performed via the modified Stoppa approach, while this will be not necessary with the Pararectus approach [19, 21, 31, 33, 34].

The so-called infraacetabular screw was first described by Culeman et al. in 2011 as a transfixation of both columns through an additional pathway anterior and inferior to the acetabulum [35]. Several biomechanical studies demonstrated, that an infraacetabular screw augments the biomechanical stability of osteosynthetically stabilized fractures involving both columns [36–39]. The infraacetabular screw can be inserted using all established less invasive approaches [19, 34, 40]. Consequently, if the antegrade posterior column screw could be replaced by an infraacetabular screw for stabilization of ACPHT fractures, the surgical straightforwardness would further be improved. However, the biomechanical stability of a plate osteosynthesis of the anterior column combined with an infraacetabular screw instead of an antegrade posterior column screw is unknown so far. Hence, the aim of this biomechanical study is to compare a plate osteosynthesis of the anterior column plus an antegrade posterior column screw with a plate osteosynthesis of the anterior column plus an infraacetabular screw in a synthetic hemipelvis model of an ACPHT fracture. We hypothesized that the infraacetabular screw has an inferior biomechanical stability compared to the antegrade posterior column screw.

Materials and methods

Fracture model and osteosynthesis constructs

In this study, 12 synthetic left hemipelves (Composite, 17 PCF solid foam core, 4th generation, Sawbones, Malmö, Sweden) were used. An anterior column plus posterior hemitransverse fracture was created in a standardized manner with an oscillating saw as described previously by Tanoglu et al. [41]. Afterwards, the 12 hemipelves were randomly assigned to one of the following groups:

APCS group (n = 6): Suprapectineal plate osteosynthesis plus an antegrade posterior column screw

IAS group (n = 6): Suprapectineal plate osteosynthesis plus an infraacetabular screw

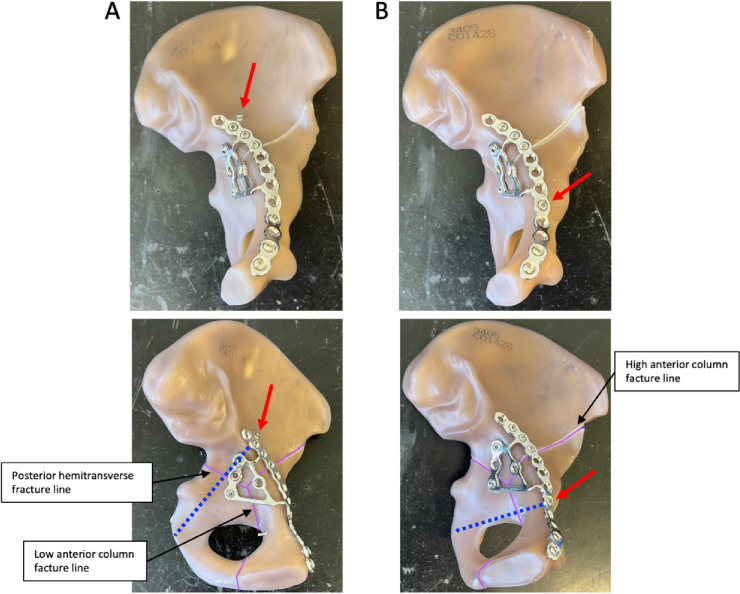

In both groups, the fracture was stabilized with a suprapectineal plate with quadrilateral buttress (PRO Pelvis and Acetabulum System, Stryker, Amsterdam, Netherlands) as the basic osteosynthesis. Bicortical 3.5 mm screws were used for fixation of the plate as it is shown in Fig. 1. For the APCS group, a 3.5 mm antegrade posterior column screw was inserted as described previously by Jung et al. outside the plate [21]. For the IAS group, a 3.5 mm infraacetabular screw was inserted as described previously by Baumann et al. through the fifth plate hole from ventral [40]. Both osteosynthesis constructs are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Fixation of a standardized generated anterior column plus posterior hemitransverse fracture with a suprapectineal plate plus an antegrade posterior column screw (A) or plus an infraacetabular screw (B). Red arrows indicate either the antegrade posterior column screw or the infraacetabular screw and the blue doted lines their respective course. The fracture lines are outlined in purple and the three main fracture lines are labeled

Test setup

Biomechanical testing was performed with a single-leg stance model as described by Becker et al. [42]. As recently described in a review, the biomechanical test setup of Becker et al. is an optimal model to simulate the physiological forces and force angles of the hip joint, since it is based on the observations made by Bergmann et al. in vivo with telemetric hip implants [43–45].

The hemipelvis was rigidly connected to a sacrum substitute (polyurethane cast, RenCast FC 53 A/B, Gößl + Pfaff GmbH, Karlskron/Brautlach, Germany) via three threaded rods with corresponding nuts to ensure an equal load distribution between the testing machine and the synthetic hemipelvis. The sacrum substitute was connected via a ball joint, which consisted of a 36 mm diameter ceramic ball and an artificial acetabular cup embedded in an aluminum cylinder, to a linear slide. The linear slide in turn was attached to the actuator of an electro-dynamic testing machine (LTM10 T, ZwickRoell AG, Ulm, Germany). Force was applied proximally via the testing machine to the hemipelvis. The linear slide ensured a vertical force direction by enabling lateral movements, and in combination with the ball joint, movement of the hemipelvis in all three axes was allowed. Distally the hemipelvis was moveably connected via a 28 mm ball and a 55 mm dual head cup to a hip prosthesis revision stem, which was embedded in an aluminum cylinder. An additional tension mechanism with a 3 mm UHMWPE fiber cord (LIROS GmbH, Berg, Germany) was mounted via a plate and three screws at the ala of the os ilium to prevent collapsing of the hemipelvis and to generate a secondary, passive force mimicking the main muscle forces at the pelvis. A load cell (U3, measuring range 1 kN, HBM GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany) was used to measure the additional, secondary force and a turnbuckle was used to adapt the length of the tension mechanism to achieve physiological loading angles, as observed by Bergman et al. [43–45]. The effective loading force at the acetabulum was the sum of the axially applied primary loading via the electro-dynamic testing machine and of the secondary, passive load resulting from the tension mechanism. Figure 2 illustrates the biomechanical test setup.

Fig. 2.

Biomechanical test setup. The hemipelvis was mounted proximally via a sacrum substitute with a ball joint to an electro-dynamic test machine. Distally the hemipelvis was connected to a prosthesis stem with a femoral head. The hemipelvis, which was thus freely movable in all three axes, was stabilized by an additional tension mechanism via a plate at the os ilium

Testing protocol

A cyclic sinusoidal fatigue test protocol with periodically increasing loading forces was applied to the synthetic hemipelves as described by Becker et al. [42]. The lower level set point of the axially applied sinusoidal cyclic loading via the electro-dynamic testing machine was set to 50 N and the initial upper level set point was 250 N. The upper level set point was increased by 50 N every 1000 cycles up to a maximum of 1800 N. This resulted in a total of 32,000 cycles. The loading frequency was 1 Hz. The secondary, passive load ranged between 500 and 600 N when the final primary load of 1800 N were applied resulting in an effective load at the acetabulum of 2300–2400 N. These loading forces are comparable to the maximum resulting hip loads measured by Bergmann et al. with telemetric hip implants during normal walking [43–45]. A sudden loss of resistance and/or an (out-)breakage of the osteosynthesis construct were defined as stop criteria for the biomechanical testing.

Measurement system and measurement variables

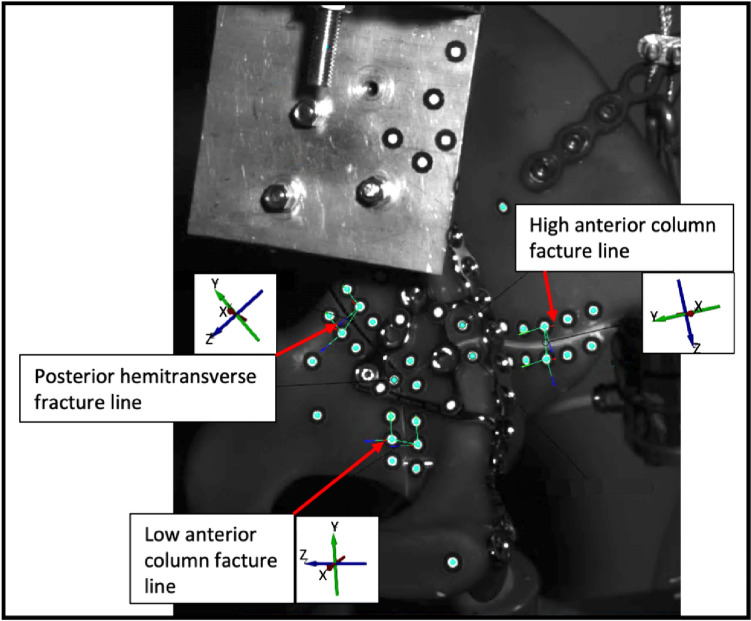

Measurements were performed with a 3D motion analysis video system (ARAMIS 5 M, Carl Zeiss GOM Metrology GmbH, Braunschweig, Germany) with tracked passive optical markers along the three main fracture lines: Posterior hemitransverse fracture line, high anterior column fracture line and low anterior column fracture line (Fig. 3). The GOM Correlate Pro software was used to analyze interfragmentary motion and interfragmentary rotation. Therefore, a six degrees of freedom (6-DoF) analysis was performed for each of the three fracture lines using the local coordinate systems and rigid-body motion correction. This results in three measurement variables for interfragmentary motion (LX [mm], LY [mm] and LZ [mm]) and three measurement variables for interfragmentary rotation (Phi(X) [°], Theta(Y) [°], Psi(Z) [°]) along each of the three axes. Additionally, shearXY [mm] was calculated according to the following formula:

Fig. 3.

Analysis of interfragmentary motion and interfragmentary rotation of the three main fracture lines (posterior hemitransverse fracture line, high anterior column fracture line, low anterior column fracture line) with a 6-DoF measurement with regard to the corresponding coordinate systems shown

Figure 3 illustrates the three main fracture lines and their corresponding coordinate systems, on the basis of which interfragmentary motion and rotation were assessed.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis and data visualization were performed using GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Interfragmentary motion and rotation were compared between the APCS and the IAS group and were calculated as the difference between the 32,000th cycle with a primary load of 1800 N and the initial primary loading with 50 N at the start of cyclic loading protocol. Hence, the interfragmentary motion reported in this study represents a combined elastic–plastic deformation. Unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test was used for comparison. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation unless otherwise stated. Exact p-values are reported unless p < 0.001 and p-values of ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

A stop criterion of the biomechanical testing (sudden loss of resistance and/or (out-)breakage of the osteosynthesis construct) was not reached in any of the 12 hemipelves. Table 1 shows the comparison of interfragmentary motion and rotation for the three main fracture lines between the APCS group and the IAS group at a primary load with 1800 N after the 32,000th cycle in relation to the initial primary loading with 50 N at the start of cyclic loading protocol.

Table 1.

Comparison of interfragmentary motion and interfragmentary rotation along the three axes between the APCS group and the IAS group for the three main fracture lines

| Antegrade posterior column screw (n = 6) | Infraacetabular screw (n = 6) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Posterior hemitransverse fracture line | |||

| Interfragmentary motion | |||

| Shear XY [mm] | 0.305 ± 0.173 | 1.174 ± 0.356 | < 0.001 |

| LX [mm] | 0.284 ± 0.198 | 1.156 ± 0.337 | < 0.001 |

| LY [mm] | 0.049 ± 0.050 | 0.172 ± 0.169 | 0.119 |

| LZ [mm] | 0.121 ± 0.075 | 0.111 ± 0.096 | 0.840 |

| Interfragmentary rotation | |||

| Phi(X) [°] | 0.376 ± 0.241 | 0.244 ± 0.190 | 0.319 |

| Theta(Y) [°] | 0.381 ± 0.352 | 0.547 ± 0.486 | 0.513 |

| Psi(Z) [°] | 0.522 ± 0.486 | 0.643 ± 0.347 | 0.631 |

| High anterior column fracture line | |||

| Interfragmentary motion | |||

| Shear XY [mm] | 0.814 ± 0.205 | 0.966 ± 0.599 | 0.571 |

| LX [mm] | 0.800 ± 0.218 | 0.875 ± 0.639 | 0.792 |

| LY [mm] | 0.116 ± 0.076 | 0.324 ± 0.161 | 0.017 |

| LZ [mm] | 0.574 ± 0.339 | 0.708 ± 0.431 | 0.562 |

| Interfragmentary rotation | |||

| Phi(X) [°] | 0.315 ± 0.079 | 0.488 ± 0.279 | 0.174 |

| Theta(Y) [°] | 0.390 ± 0.316 | 0.293 ± 0.176 | 0.524 |

| Psi(Z) [°] | 0.267 ± 0.147 | 0.621 ± 0.408 | 0.074 |

| Low anterior column fracture line | |||

| Interfragmentary motion | |||

| Shear XY [mm] | 0.612 ± 0.152 | 0.183 ± 0.125 | < 0.001 |

| LX [mm] | 0.455 ± 0.130 | 0.177 ± 0.126 | 0.004 |

| LY [mm] | 0.408 ± 0.083 | 0.032 ± 0.037 | < 0.001 |

| LZ [mm] | 0.183 ± 0.060 | 0.072 ± 0.039 | 0.004 |

| Interfragmentary rotation | |||

| Phi(X) [°] | 0.271 ± 0.265 | 0.234 ± 0.199 | 0.789 |

| Theta(Y) [°] | 0.684 ± 0.394 | 0.474 ± 0.343 | 0.348 |

| Psi(Z) [°] | 0.306 ± 0.075 | 0.364 ± 0.349 | 0.696 |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. A p-value ≤ 0.05 is considered statistically significant. p-values indicating a statistically significant difference are highlighted in bold

For the posterior hemitransverse fracture line, interfragmentary motion along the X-axis (LX [mm]; APCS: 0.284 ± 0.198 vs. IAS: 1.156 ± 0.337; p < 0.001) and shear in XY direction (shearXY [mm]; APCS: 0.305 ± 0.173 vs. IAS: 1.174 ± 0.356; p < 0.001) were significantly higher in the IAS group compared to the APCS group. All other variables for interfragmentary motion and interfragmentary rotation did not show a significant difference between both groups regarding the posterior hemitransverse fracture line.

Interfragmentary motion and interfragmentary rotation at the high anterior column fracture line were also not significantly different between both groups, except of a significantly elevated interfragmentary motion along the Y-axis in the IAS group compared to the APCS group (LY [mm]; APCS: 0.116 ± 0.076 vs. IAS: 0.324 ± 0.161; p = 0.017).

For the low anterior column fracture line, interfragmentary motion along the X-axis (LX [mm]; APCS: 0.455 ± 0.130 vs. IAS: 0.177 ± 0.126; p = 0.004), Y-axis (LY [mm]; APCS: 0.408 ± 0.083 vs. IAS: 0.032 ± 0.037; p < 0.001) and Z-axis (LZ [mm]; APCS: 0.183 ± 0.060 vs. IAS: 0.072 ± 0.039; p = 0.004) as well as shear in XY direction (shearXY [mm]; APCS: 0.612 ± 0.152 vs. IAS: 0.183 ± 0.125; p < 0.001) were significantly higher in the APCS group compared to the IAS group. Interfragmentary rotation at the low anterior column fracture line was not significantly different between both groups. Figure 4 illustrates interfragmentary motion of the APCS group and IAS group for the three main fracture lines.

Fig. 4.

Interfragmentary motion along the three axes of the antegrade posterior column screw group and the infraacetabular screw group for the three main fracture lines. Columns represent mean and error bars indicate standard deviation. p-values ≤ 0.05 are considered statistically significant

Discussion

This biomechanical study revealed that an antegrade posterior column screw provides a superior biomechanical stability compared to an infraacetabular screw when focusing on the posterior column in acetabulum fractures. Therefore, the hypothesis that an infraacetabular screw has an inferior biomechanical stability compared to the antegrade posterior column screw in fixation of acetabulum fractures with posterior column involvement was confirmed. Consequently, the infraacetabular screw should not be mistaken as a possible replacement for the traditional antegrade posterior column screw.

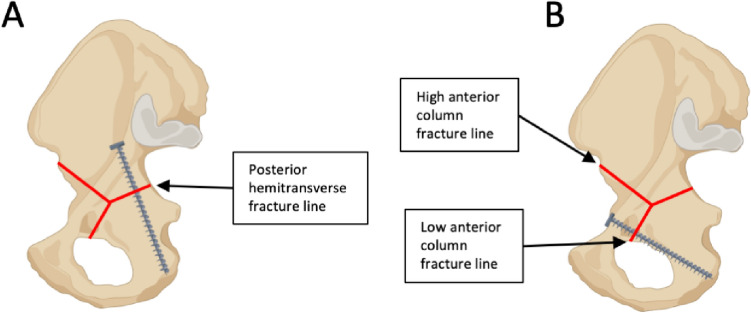

More precisely, it was demonstrated, that interfragmentary motion at the posterior hemitransverse fracture line (LX, shear XY) and at the high anterior column fracture line (LY) was significantly increased when an infraacetabular screw was used instead of an antegrade posterior column screw, each in combination with a suprapectineal plate. By contrast, fixation with an infraacetabular screw instead of an antegrade posterior column screw resulted in a reduced interfragmentary motion (LX, LY, LZ, shear XY) at the low anterior column fracture line. These results demonstrate that interfragmentary motion was increased at certain main fracture lines of the ACPHT fracture in both groups depending on the different screw courses. As it is illustrated in Fig. 5, the antegrade posterior column screw runs more perpendicular to the posterior hemitransverse fracture line and bridges the fracture line resulting in a higher fixation strength compared to the infraacetabular screw at this fracture line. In contrast, the infraacetabular screw runs more perpendicular to the low anterior column fracture line and bridges the fracture line resulting in a lower interfragmentary motion at this fracture line when an infraacetabular screw was used instead of an antegrade posterior column screw.

Fig. 5.

Screw courses of the antegrade posterior column screw (A) and of the infraacetabular screw (B) in relation to the three main fracture lines (red lines) of an ACPHT fracture. Created with BioRender.com

Besides an exact anatomical reduction, a biomechanically stable fracture fixation is one of the main predictors for the clinical and radiological outcome after surgically treated acetabulum fractures. Failure of osteosynthesis and secondary displacement due to an insufficient biomechanical stability increase the risk for a posttraumatic osteoarthritis of the hip joint [8, 11–13]. A remaining or secondary displacement was found to be clinically relevant only above 2–3 mm, since above this limit, the risk of a posttraumatic osteoarthritis is markedly increasing [8, 13]. The highest interfragmentary motions, which we measured in this biomechanical study, were 1.156 mm ± 0.337 mm (posterior hemitransverse fracture line, X-axis, IAS group) and 0.455 mm ± 0.130 mm (low anterior column fracture line, X-axis, APCS group) and thus were below the limit of 2–3 mm. Nevertheless, Hartel et al. showed that, especially in geriatric patients with osteoporotic bone, a biomechanically stable fixation of acetabulum fractures is pivotal for the radiological outcome [7]. In addition, a biomechanically stable fixation of acetabulum fractures is important to enable early mobilization of geriatric patients to avoid immobilization-associated complications [14–16]. It should be borne in mind that other factors also influence the risk for a posttraumatic osteoarthritis. For example, a dome impaction and a quadrilateral surface fragment, which were not considered in the ACPHT fracture model in this study, increase the risk for a posttraumatic osteoarthritis. Consequently, these risk factors should be included in the surgical planning and, particularly in geriatric patients, should be considered as a potential indication for primary arthroplasty [8, 46–48].

The increased interfragmentary motions observed in this study were not along the Z-axis, which would have led to compression of the fracture, but were shearing movements along the X-axis and Y-axis. It was shown that while axial compression on the fracture promotes bone healing, shear movements along the fracture line delay bone healing resulting in a decrease in mechanical stability [49, 50]. Thus, the increased interfragmentary motion at the main fracture lines along the X-axis and Y-axis could lead to a delayed union of the ACPHT fracture.

In addition to the conclusion from these data that an antegrade posterior column screw should not be replaced by an infraacetabular screw, it can be assumed that an infraacetabular screw as well as an antegrade posterior column screw may be used in combination to treat an ACPHT fracture, especially in cases where maximum stability is required. However, this hypothesis needs to be tested in further biomechanical studies. A FEA study of Wang et al. also demonstrated that an infraacetabular screw alone does not provide sufficient biomechanical stability for an isolated posterior column fracture but the biomechanical stability of a posterior column screw is increased with an additional infraacetabular screw [51]. This is in line with the concept of the infraacetabular screw, which was described by Culemann et al. in 2011: Closing of the periacetabular frame with an infraacetabular screw augments the biomechanical stability of acetabulum fractures involving both columns [35–39]. Graul et al. showed in a synthetic hemipelvis model with an ACPHT fracture that while the biomechanical stability of a two-dimensionally shaped conventional plate (J-plate) can be augmented with an infraacetabular screw, the addition of an infraacetabular screw does not result in an enhanced biomechanical stability of a three-dimensionally shaped plate, such as a suprapectineal plate with quadrilateral buttress [37]. In contrast, we demonstrated in this biomechanical analysis, that even when a suprapectineal plate is used, an infraacetabular screw significantly reduces interfragmentary motion at the low anterior column fracture line.

Some limitations of this biomechanical study should be considered. Although the test setup was developed to simulate the physiological loading forces and angles, which were described by Bergmann et al. in vivo, as accurately as possible, it still requires some simplifications and therefore only provides an approximation. Nevertheless, preliminary tests confirmed that the loading forces and angles are comparable to those observed in vivo, especially when compared to other available test setups for acetabulum fractures, and main muscle forces are included in this test setup [42–45]. A cyclic loading protocol with a total of 32,000 cycles was used, which is closer to a classical fatigue loading protocol with simulation of the postoperative phase than the majority of other available biomechanical test setups for acetabulum fractures [45]. However, a classical fatigue loading protocol requires 100,000 cycles or more and Olson et al. concluded that 200,000–250,000 cycles are necessary to cover the postoperative time until fracture healing [45, 52]. When interpreting the interfragmentary motion reported in this study, particularly with regard to the influence of shear motion on fracture healing, it must be noted that it represents a combined elastic–plastic deformation, since it was calculated as the difference between the 32,000th cycle with a primary load of 1800 N and the initial primary loading with 50 N at the start of cyclic loading protocol. However, in our opinion, this best represents the complex processes in vivo in the first months after fracture fixation. Although ACPHT fractures, especially in geriatric patients, are often accompanied by a dome impaction and a quadrilateral surface fragment, we used a standardized and previously validated ACPHT fracture model without dome impaction or a quadrilateral surface fragment in this biomechanical study [2, 8, 41, 53]. The reason for this was to focus on the stability of the two main columns of the acetabulum and especially on the fixation of the posterior column when assessing the effect of replacing the antegrade posterior column screw with an infraacetabular screw as well as to increase comparability with previous biomechanical studies by using this standardized and validated fracture model. A synthetic bone model as used in this biomechanical study provides standardized biomechanical conditions with a high comparability and reproducibility. On the other hand, simulation of the structural and mechanical properties of bone in vivo, especially of osteoporotic bone in elderly patients, is limited with synthetic bone substitutes.

Conclusion

It was demonstrated that fixation of an ACPHT fracture with a suprapectineal plate combined with an infraacetabular screw instead of an antegrade posterior column screw resulted in an increased interfragmentary motion at the posterior hemitransverse fracture line and the high anterior column fracture line. Fixation with a suprapectineal plate combined with an antegrade posterior column screw but without an infraacetabular screw showed a higher interfragmentary motion at the low anterior column fracture line. Consequently, replacing the antegrade posterior column screw by an infraacetabular screw in the surgical treatment of acetabulum fractures with posterior column involvement can not be recommended. Future biomechanical studies may investigate whether the combination of an antegrade posterior column screw and an infraacetabular screw would be beneficial to obtain maximum stability.

Acknowledgements

None

Author contributions

Conceptualization: NH, KHF, PA, MJH; Formal analysis: NH, DB, MM; Investigation: NH, DB, JD, MM, MJH; Methodology: NH, DB, JD, MM, PA, MJH; Project administration: NH, KHF, PA, MJH; Supervision: KHF, PA, MJH; Visualization: NH, DB, MM; Writing - original draft preparation and visualization: NH, MJH; Writing - review and editing: JD, DB, KHF. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rupp M, Walter N, Pfeifer C, Lang S, Kerschbaum M, Krutsch W, et al. The incidence of fractures among the adult population of Germany-an analysis from 2009 through 2019. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2021;118(40):665–669. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.m2021.0238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferguson TA, Patel R, Bhandari M, Matta JM. Fractures of the acetabulum in patients aged 60 years and older: an epidemiological and radiological study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(2):250–257. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B2.22488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rinne PP, Laitinen MK, Huttunen T, Kannus P, Mattila VM. The incidence and trauma mechanisms of acetabular fractures: a nationwide study in Finland between 1997 and 2014. Injury. 2017;48(10):2157–2161. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2017.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Letournel E, Judet R. Fractures of the acetabulum. 2. Berlin: Springer; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Firoozabadi R, Cross WW, Krieg JC, Routt MLC. Acetabular fractures in the senior population- epidemiology, mortality and treatments. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2017;5(2):96–102. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herath SC, Pott H, Rollmann MFR, Braun BJ, Holstein JH, Hoch A, et al. Geriatric acetabular surgery: letournel's contraindications then and now-data from the German pelvic registry. J Orthop Trauma. 2019;33(Suppl 2):S8–S13. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000001406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartel MJ, Naji T, Fensky F, Henes FO, Thiesen DM, Lehmann W, et al. The influence of bone quality on radiological outcome in 50 consecutive acetabular fractures treated with a pre-contoured anatomic suprapectineal plate. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2022;142(7):1539–1546. doi: 10.1007/s00402-021-03867-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tannast M, Najibi S, Matta JM. Two to twenty-year survivorship of the hip in 810 patients with operatively treated acetabular fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(17):1559–1567. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.00444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vipulendran K, Kelly J, Rickman M, Chesser T. Current concepts: managing acetabular fractures in the elderly population. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s00590-021-02931-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelly J, Ladurner A, Rickman M. Surgical management of acetabular fractures—a contemporary literature review. Injury. 2020;51(10):2267–2277. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2020.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mears DC, Velyvis JH, Chang CP. Displaced acetabular fractures managed operatively: indicators of outcome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;407:173–186. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200302000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zha GC, Sun JY, Dong SJ. Predictors of clinical outcomes after surgical treatment of displaced acetabular fractures in the elderly. J Orthop Res. 2013;31(4):588–595. doi: 10.1002/jor.22279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ziran N, Soles GLS, Matta JM. Outcomes after surgical treatment of acetabular fractures: a review. Patient Saf Surg. 2019;13:16. doi: 10.1186/s13037-019-0196-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kammerlander C, Pfeufer D, Lisitano LA, Mehaffey S, Bocker W, Neuerburg C. Inability of older adult patients with hip fracture to maintain postoperative weight-bearing restrictions. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100(11):936–941. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.17.01222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamel HK, Iqbal MA, Mogallapu R, Maas D, Hoffmann RG. Time to ambulation after hip fracture surgery: relation to hospitalization outcomes. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58(11):1042–1045. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.11.m1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Siu AL, Penrod JD, Boockvar KS, Koval K, Strauss E, Morrison RS. Early ambulation after hip fracture: effects on function and mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(7):766–771. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.7.766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khajavi K, Lee AT, Lindsey DP, Leucht P, Bellino MJ, Giori NJ. Single column locking plate fixation is inadequate in two column acetabular fractures. A biomechanical analysis. J Orthop Surg Res. 2010;5:30. doi: 10.1186/1749-799X-5-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ochs BG, Marintschev I, Hoyer H, Rolauffs B, Culemann U, Pohlemann T, et al. Changes in the treatment of acetabular fractures over 15 years: analysis of 1266 cases treated by the German Pelvic Multicentre Study Group (DAO/DGU) Injury. 2010;41(8):839–851. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gänsslen A, Müller M, Nerlich M, Lindahl J. Acetabular fractures—diagnosis, indications, treatment strategies. Stuttgart: Thieme; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suzuki T, Smith WR, Mauffrey C, Morgan SJ. Safe surgical technique for associated acetabular fractures. Patient Saf Surg. 2013;7(1):7. doi: 10.1186/1754-9493-7-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jung GH, Lee Y, Kim JW, Kim JW. Computational analysis of the safe zone for the antegrade lag screw in posterior column fixation with the anterior approach in acetabular fracture: a cadaveric study. Injury. 2017;48(3):608–614. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2017.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Le Quang H, Schmoelz W, Lindtner RA, Dammerer D, Schwendinger P, Krappinger D. Single column plate plus other column lag screw fixation vs both column plate fixation for anterior column with posterior hemitransverse acetabular fractures—a biomechanical analysis using different loading protocols. Injury. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2020.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jeffcoat DM, Carroll EA, Huber FG, Goldman AT, Miller AN, Lorich DG, et al. Operative treatment of acetabular fractures in an older population through a limited ilioinguinal approach. J Orthop Trauma. 2012;26(5):284–289. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e31821e10a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krappinger D, Schwendinger P, Lindtner RA. Fluoroscopically guided acetabular posterior column screw fixation via an anterior approach. Oper Orthop Traumatol. 2019;31(6):503–512. doi: 10.1007/s00064-019-00631-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hartel MJ, Althoff G, Wolter S, Ondruschka B, Dietz E, Frosch KH, et al. Full endoscopic anterior intrapelvic plate osteosynthesis: a cadaveric feasibility study. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2023;143(1):365–371. doi: 10.1007/s00402-022-04346-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bishop JA, Routt ML., Jr Osseous fixation pathways in pelvic and acetabular fracture surgery: osteology, radiology, and clinical applications. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72(6):1502–1509. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318246efe5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keel MJ, Ecker TM, Siebenrock KA, Bastian JD. Rationales for the Bernese approaches in acetabular surgery. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2012;38(5):489–498. doi: 10.1007/s00068-012-0229-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cole JD, Bolhofner BR. Acetabular fracture fixation via a modified stoppa limited intrapelvic approach description of operative technique and preliminary treatment results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;305:112–123. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199408000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sagi HC, Afsari A, Dziadosz D. The anterior intra-pelvic (modified rives-stoppa) approach for fixation of acetabular fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2010;24(5):263–270. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e3181dd0b84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuper MA, Rohm B, Audretsch C, Stockle U, Hoch A, Histing T, et al. Pararectus approach vs. Stoppa approach for the treatment of acetabular fractures—a comparison of approach-related complications and operative outcome parameters from the German Pelvic Registry. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2022;108(4):103275. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2022.103275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keel MJB, Siebenrock KA, Tannast M, Bastian JD. The pararectus approach: a new concept. JBJS Essent Surg Tech. 2018;8(3):e21. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.ST.17.00060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soni A, Gupta R, Sen R. Acetabulum fractures in elderly patients: a review. Chin J Traumatol. 2022;25(6):331–335. doi: 10.1016/j.cjtee.2021.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tannast M, Keel MJB, Siebenrock KA, Bastian JD. Open reduction and internal fixation of acetabular fractures using the modified Stoppa approach. JBJS Essent Surg Tech. 2019;9(1):e3. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.ST.18.00034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bastian JD, Savic M, Cullmann JL, Zech WD, Djonov V, Keel MJ. Surgical exposures and options for instrumentation in acetabular fracture fixation: Pararectus approach versus the modified Stoppa. Injury. 2016;47(3):695–701. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2016.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Culemann U, Marintschev I, Gras F, Pohlemann T. Infra-acetabular corridor–technical tip for an additional screw placement to increase the fixation strength of acetabular fractures. J Trauma. 2011;70(1):244–246. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181f45f91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marintschev I, Gras F, Schwarz CE, Pohlemann T, Hofmann GO, Culemann U. Biomechanical comparison of different acetabular plate systems and constructs–the role of an infra-acetabular screw placement and use of locking plates. Injury. 2012;43(4):470–474. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Graul I, Marintschev I, Pizanis A, Herath SC, Pohlemann T, Fritz T. The effect of an infra-acetabular screw for anatomically shaped three-dimensional plate or standard plate designs in acetabulum fractures: a biomechanical analysis. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s00068-021-01805-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.May C, Egloff M, Butscher A, Keel MJB, Aebi T, Siebenrock KA, et al. Comparison of fixation techniques for acetabular fractures involving the anterior column with disruption of the quadrilateral plate: a biomechanical study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100(12):1047–1054. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.17.00295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gras F, Marintschev I, Schwarz CE, Hofmann GO, Pohlemann T, Culemann U. Screw- versus plate-fixation strength of acetabular anterior column fractures: a biomechanical study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72(6):1664–1670. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182463b45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baumann F, Schmitz P, Mahr D, Kerschbaum M, Gansslen A, Nerlich M, et al. A guideline for placement of an infra-acetabular screw based on anatomic landmarks via an intra-pelvic approach. J Orthop Surg Res. 2018;13(1):77. doi: 10.1186/s13018-018-0786-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tanoglu O, Alemdaroglu KB, Iltar S, Ozmeric A, Demir T, Erbay FK. Biomechanical comparison of three different fixation techniques for anterior column posterior hemitransverse acetabular fractures using anterior intrapelvic approach. Injury. 2018;49(8):1513–1519. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2018.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Becker J, Winkler M, von Ruden C, Bliven E, Augat P, Resch H. Comparison of two reinforcement rings for primary total hip arthroplasty addressing displaced acetabular fractures: a biomechanical analysis. Arch Orthop Traum Su. 2020;140(12):1947–1954. doi: 10.1007/s00402-020-03433-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bergmann G, Deuretzbacher G, Heller M, Graichen F, Rohlmann A, Strauss J, et al. Hip contact forces and gait patterns from routine activities. J Biomech. 2001;34(7):859–871. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(01)00040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bergmann G, Graichen F, Rohlmann A. Hip joint loading during walking and running, measured in two patients. J Biomech. 1993;26(8):969–990. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(93)90058-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hinz N, Dehoust J, Munch M, Seide K, Barth T, Schulz AP, et al. Biomechanical analysis of fixation methods in acetabular fractures: a systematic review of test setups. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s00068-022-01936-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang BF, Zhuang Y, Liu L, Xu K, Wang H, Wang B, et al. Current indications for acute total hip arthroplasty in older patients with acetabular fracture: evidence in 601 patients from 2002 to 2021. Front Surg. 2022;9:1063469. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2022.1063469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou XF, Gu SC, Zhu WB, Yang JZ, Xu L, Fang SY. Quadrilateral plate fractures of the acetabulum: classification, approach, implant therapy and related research progress. World J Clin Cases. 2022;10(2):412–425. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i2.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lim EJ, Shon HC, Yang JY, Ahn J, Kim JJ, Kim JW. Surgical outcomes of acetabular fracture of elderly patients with superomedial dome impaction. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):19091. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-46652-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Augat P, Hollensteiner M, von Ruden C. The role of mechanical stimulation in the enhancement of bone healing. Injury. 2021;52(Suppl 2):S78–S83. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2020.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Augat P, Burger J, Schorlemmer S, Henke T, Peraus M, Claes L. Shear movement at the fracture site delays healing in a diaphyseal fracture model. J Orthop Res. 2003;21(6):1011–1017. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(03)00098-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang T, Zhao B, Yan J, Shao B, Mu W. Finite element analysis of infra-acetabular screw fixation for the treatment of acetabular posterior column fracture. Int Orthop. 2022;46(3):623–634. doi: 10.1007/s00264-021-05298-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Olson SA, Marsh JL, Anderson DD, Latta Pe LL. Designing a biomechanics investigation: choosing the right model. J Orthop Trauma. 2012;26(12):672–677. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e3182724605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.White G, Kanakaris NK, Faour O, Valverde JA, Martin MA, Giannoudis PV. Quadrilateral plate fractures of the acetabulum: an update. Injury. 2013;44(2):159–167. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.