Abstract

Background

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) has established itself as the gold standard for serial assessment of systemic right ventricular (RV) performance but due to the lack of standardized RV reference values for hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) patients, the interpretation of RV volumetric data in HLHS remains difficult. Therefore, this study aimed to close this gap by providing CMR reference values for the systemic RV in HLHS patients.

Methods

CMR scans of 160 children, adolescents, and young adults (age range 2.2–25.2 years, 106 males) with HLHS were retrospectively evaluated. All patients were studied following total cavopulmonary connection. Short-axis stacks were used to measure RV end-diastolic and end-systolic volumes (RVEDV, RVESV), RV stroke volume (RVSV), RV ejection fraction (RVEF), and RV end-diastolic myocardial mass (RVEDMM). Univariable and multiple linear regression analyses were performed to assess associations between RV parameters and demographic and anthropometric characteristics. Following the results of the regression analysis, reference graphs and tables were created with the Lambda-Mu-Sigma method.

Results

Multiple linear regression analysis showed strong associations between body height and RVEDV, RVESV as well as RVSV. Age was highly associated with RVEDMM. Therefore, percentile curves and tables were created with respect to body height (RVEDV, RVESV, RVSV) and age (RVEDMM). The influence of demographic and anthropometric parameters on RVEF was mild, thus no percentile curves and tables for RVEF are provided.

Conclusion

We were able to define CMR reference values for RV volumetric variables for HLHS patients. These data might be useful for the assessment and interpretation of CMR scans in these patients and for research in this field.

Keywords: Hypoplastic left heart syndrome, Reference values, Children, Cardiovascular magnetic resonance

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) is a complex congenital heart defect that is typically treated by a three-stage surgical palliation [1]. The Norwood operation is the first surgical step and is followed by the creation of an upper cavopulmonary connection and a total cavopulmonary connection (TCPC) as the second and third surgical steps [1]. Survival rates for patients have increased over time [2], [3], but concerns about the long-term performance of the single right ventricle (RV) exist [4]. A current position statement for patients with a Fontan circulation recommends cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging to monitor serial changes in ventricular function [4]. This is supported by previous CMR studies from our group that showed a significant increase in RV volumes as well as a decrease in RV global longitudinal strain in HLHS patients after TCPC completion during serial follow-up and confirmed that CMR is well suited for serial RV follow-up [5], [6].

However, to interpret quantitative CMR results, disease-specific RV reference values are desirable that can be used for comparison especially in patients with no serial follow-up data [7], [8]. It was therefore the goal of this study to create CMR reference values for RV volumetric variables in patients with HLHS from early childhood to adulthood.

2. Methods

2.1. Study population

In this single-center study, patients with HLHS who underwent a clinical CMR study in our institution between 2006 and 2023 were retrospectively included. Inclusion criteria were the availability of a CMR short-axis cine stack, completion of the TCPC as well as an age between 2 and 25 years. In patients who had several CMR studies during their clinical follow-up, only one of these studies, which had the best image quality, was analyzed for this project.

Patients with poor CMR image quality that did not allow ventricular volumetry were excluded. Apart from CMR parameters, age at the time of the CMR study, sex body weight, body height, body surface area (BSA), body mass index (BMI), and heart rate were documented.

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the local ethics committee of the Christian-Albrechts-University (reference number: AZ D503/20). A general informed consent was available for all parents or legal guardians, as appropriate.

2.2. CMR acquisition

CMR was performed using a 3T and a 1.5T scanner (Philips Achieva and Philips Ingenia, Philips Healthcare, Hamburg, Germany; Siemens MAGNETOM Aera, Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany). Standard gradient echo or steady-state free precession cine imaging with retrospective electrocardiographic gating was used to acquire short-axis cine stacks with coverage of the systemic RV from base to apex (Fig. 1). Scan parameters were as follows: field of view 180–400 mm, slice thickness 5–8 mm (5 mm in small children, 6–8 mm in adolescents and adults), 25 cardiac phases, no slice gap, non-breath-hold in sedated patients, breath-hold in awake patients. Acquired temporal resolution ranged between 28.9 ms and 48.9 ms.

Fig. 1.

Assessment of ventricular volumes in HLHS patients without (A-C) and with (D-F) a visible left ventricle. HLHS, hypoplastic left heart syndrome

2.3. CMR postprocessing

CMR data analysis was performed using a commercially available postprocessing software (cvi42, Circle Cardiovascular Imaging Inc., Calgary, Alberta, Canada). Short-axis cine stacks were used to measure RV end-diastolic and RV end-systolic volumes (RVEDV, RVESV) and RV end-diastolic myocardial mass (RVEDMM) by manually drawing endocardial and epicardial RV borders at end-diastole and end-systole. RV trabeculations and papillary muscles were included into the RV blood pool. RV ejection fraction (RVEF), RV cardiac output, and RV cardiac index were calculated from the measured volumes [9]. The left ventricle was excluded from the volumetry in this study. Examples of RV chamber quantification in HLHS patients with and without a visible left ventricle are shown in Fig. 1.

Tricuspid regurgitation was assessed visually from CMR and echocardiographic images in all patients. Results from phase-contrast flow measurements were used to describe the degree of neo-aortic regurgitation.

2.4. Reproducibility

Intraobserver variability was assessed by repeated measurement of RV volumes and function parameter in 30 randomly chosen patients at least 1 month after the first measurements. In addition, interobserver variability was analyzed by repeating 30 measurements by a second observer with long-standing experience in CMR imaging. Different patients were chosen for inter- and intraobserver variability.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using MedCalc (version 19.3.1, MedCalc Software Ltd, Ostend, Belgium) and the software R (version 4.0.3, R Foundation, Vienna, Austria) [10].

All tests were performed two-sided and a significance level of p = 0.05 was used. To assess reproducibility, the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was calculated. The Lambda-Mu-Sigma (LMS)-method of Cole and Green was applied to create centile graphs and tables for RVEDV, RVESV, RVMM, and RVEF as described in previous studies [11], [12]. An extended version of this method is implemented in the R package GAMLSS which was used for the analysis [13]. In this method, it is assumed that the outcome (i.e., RVEDV, RVESV, RVMM, and RVEF) follows a certain distribution where different distributions can be chosen depending on the model fit. The parameters of the distribution, such as mean, variance, and skewness, are then modeled by a linear or non-linear function of the interesting influence variable (here body height or age).

The influence of factors on RVEDV, RVESV, RVSV, RVEF, and RVEDMM was analyzed for each influence variable separately and in a multiple fashion with linear regression models with and without interactions. The fit of the linear model was assessed with influence factor versus outcome plots, residual versus fitted plots, q-q plots, scale-location plots, and residual versus leverage plots as described before from this group [11]. The variables RVEDV, RVESV, RVSV, and RVEDMM were transformed by the logarithmic function to base e to achieve normality. The distribution of RVEF did not require any transformation. Influence variables were sex, BSA, age, body height, and body weight. Model selection was performed by backward selection and a p value threshold of 0.05.

The influence of the degree of tricuspid regurgitation was assessed with the Kruskal-Wallis test.

3. Results

One hundred and sixty patients with an age range of 2.2–25.2 years were included. Sedation with propofol and midazolam was used in small or uncooperative patients (n = 88) according to a standard protocol used in our hospital. All patients had reached the status of Fontan completion with a TCPC. Norwood procedure with a modified Blalock-Taussig shunt was performed in 152 patients, in 6 patients an aortopulmonary shunt was used and 2 patients had a Sano modification of the Norwood operation with a right ventricle-to-pulmonary artery shunt.

Tricuspid valve regurgitation was absent or mild in 146 patients. Seven patients had mild to moderate tricuspid valve regurgitation and seven patients had moderate tricuspid valve regurgitation. None of the patients had severe tricuspid regurgitation and the degree of tricuspid did impact not RV volumetric findings. Neo-aortic regurgitation was mild in 158 patients and moderate in 2 patients.

Patient characteristics and study composition are shown in Table 1 and Fig. 2. Strong correlations were observed between influence variables age, BSA, body weight, and body height (r = 0.9–0.99; Pearson correlation coefficient).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and CMR findings.

| Study population (n = 160) |

|

|---|---|

| Age, years | 10.2 [5.6; 14.9] |

| Female, n (%) | 54 (33.8) |

| Height, cm | 134.0 [114.0; 161.0] |

| Weight, kg | 30.0 [19.2; 50.5] |

| BSA, m2 | 1.1 [0.8; 1.6] |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 16.6 [15.1; 19.7] |

| Heart rate, beat/min RVEDV RVESV RVSV RVEF RVEDMM |

78.5 [69.0; 88.0] 100.3 [73.5; 159.7] 49.1 [34.7; 76.3] 51.4 [39.1; 76.6] 51.1 [45.0; 55.9] 49.2 [34.7; 68.2] |

BMI body mass index, BSA body surface area, RVEDMM right ventricular end-diastolic myocardial mass, RVEDV right ventricular end-diastolic volume, RVEF right ventricular ejection fraction, RVESV right ventricular end-systolic volume, RVSV right ventricular stroke volume.

For continuous variables, data are expressed as median and first and third quartiles. For categorical variables, the absolute frequencies and percentages are shown.

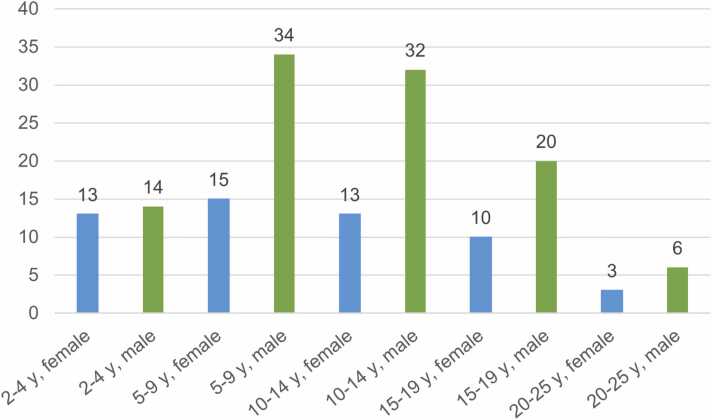

Fig. 2.

Barplot of the study population according to age and sex. y: years.

3.1. Regression analysis

Results of the univariable and multiple linear regression analysis are shown in Table 2. Univariable linear regression analysis showed that BSA, body weight, body height, and age were significantly associated with RVEDV, RVESV, RVSV, and RVEDMM. There was no significant influence of sex on RV measurements.

Table 2.

Results of the univariable and multiple linear regression analysis.

| Influence variable | Regression coefficient | Standard error | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| RVEDV (mL) | |||

| Sex, reference female | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.078 |

| BSA (m2) | 0.886 | 0.042 | <0.0001 |

| Body height (cm) | 1.29 | 0.07 | <0.0001 |

| Body weight (kg) | 0.02 | 0.001 | <0.0001 |

| Age (years) | 0.07 | 0.004 | <0.0001 |

| RVESV (mL) | |||

| Sex, reference female | 0.18 | 0.10 | 0.0635 |

| BSA (m2) | 1.07 | 0.06 | <0.0001 |

| Body height (cm) | 1.60 | 0.09 | <0.0001 |

| Body weight (kg) | 0.02 | 0.001 | <0.0001 |

| Age (years) | 0.08 | 0.005 | <0.0001 |

| RVSV (mL) | |||

| Sex, reference female | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.177 |

| BSA (m2) | 0.89 | 0.04 | <0.0001 |

| Body height (cm) | 1.29 | 0.07 | <0.0001 |

| Body weight (kg) | 0.02 | 0.001 | <0.0001 |

| Age (years) | 0.07 | 0.004 | <0.0001 |

| RVEDMM (g) | |||

| Sex, reference female | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.334 |

| BSA (m2) | 0.94 | 0.05 | <0.0001 |

| Body height (cm) | 1.38 | 0.07 | <0.0001 |

| Body weight (kg) | 0.02 | 0.001 | <0.0001 |

| Age (years) | 0.07 | 0.004 | <0.0001 |

| RVEF (%) | |||

| Sex, reference female | −1.47 | 1.36 | 0.282 |

| BSA (m2) | −3.63 | 1.42 | 0.0117 |

| Body height (cm) | −6.13 | 2.10 | 0.00397 |

| Body weight (kg) | −0.08 | 0.03 | 0.0183 |

| Age (years) | −0.28 | 0.11 | 0.013 |

Influence variables that remained significant in the multiple linear model are shown in bold.

BSA body surface area, RVEDMM right ventricular end-diastolic mass, RVEF right ventricular ejection fraction, RVEDV right ventricular end-diastolic volume, RVESV right ventricular end-systolic volume, RVSV right ventricular stroke volume.

In the multiple model, height and weight still showed significant associations with RVEDV, RVESV, and RVSV whereas for RVEDMM, age, and body weight remained in the final model.

RVEF was also significantly associated with BSA, body weight, body height, and age. Their influence on RVEF was only mild with large variations. Therefore, no percentile curves and tables are provided. There was a minimal change of RVEF by age. Median RVEF was 1) entire study population 51.1%, interquartile range (IQR) = [45.0; 55.9], 2) children between 2.2 and 7.0 years 50.7%, IQR = [45.4; 56.5], 3) children between 7.0 and 13.0 years 51.0%, IQR = [47.5; 56.1], and 4) patients between 13.0 and 25.0 years 51.2%, IQR = [43.2; 55.1]. Median cardiac output and cardiac index for the entire study population was 4.1 L/min, IQR = [3.0; 5.8] and 3.9 L/min/m2, IQR = [3.2; 4.8].

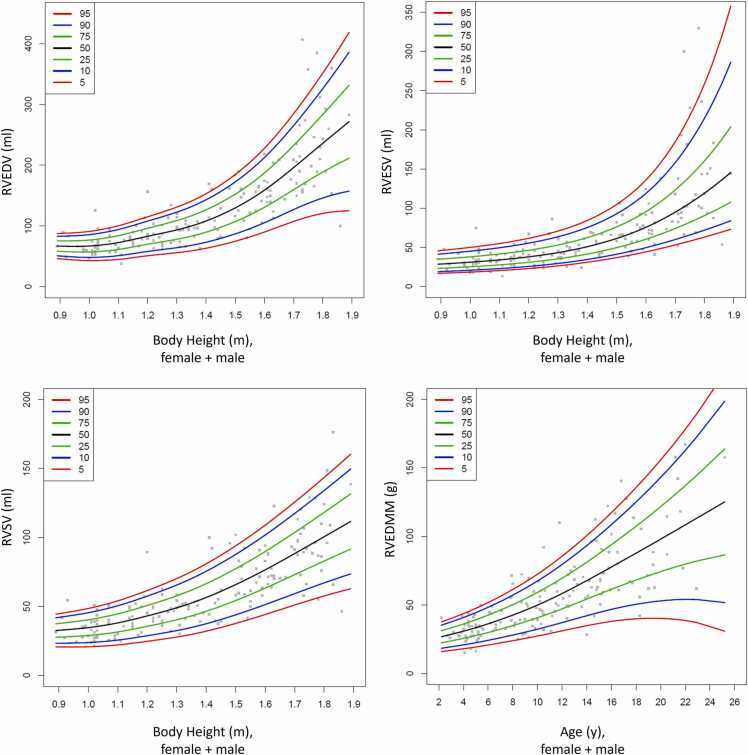

Following the results of the multiple regression analysis (Table 2), percentile curves and tables were created. As body height was the strongest influence variable for RVEDV, RVESV, and RVSV, percentile curves and tables for RVEDV, RVESV, and RVSV were created with respect to body height (Fig. 3, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6). Age was most strongly associated with RVEDMM. Therefore, percentile curves and tables for RVEDMM are shown with respect to age.

Fig. 3.

Percentile curves for RVEDV, RVESV, RVSV and RVEDMM with respect to body height or age. RVEDMM: right ventricular end-diastolic mass, RVEDV: right ventricular end-diastolic volume, RVESV: right ventricular end-systolic volume, RVSV: right ventricular stroke volume.

Table 3.

Centiles of the RVEDV for both genders. Data are shown in ml.

| RVEDV (mL) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body height (cm) | 5 | 10 | 25 | 50 | 75 | 90 | 95 |

| 90 | 46.0 | 50.6 | 58.3 | 66.9 | 75.4 | 83.2 | 87.8 |

| 100 | 43.1 | 48.4 | 57.2 | 67.1 | 76.9 | 85.8 | 91.1 |

| 110 | 45.1 | 51.2 | 61.4 | 72.7 | 84.1 | 94.3 | 100.4 |

| 120 | 51.1 | 58.1 | 70.0 | 83.1 | 96.2 | 108.0 | 115.1 |

| 130 | 56.1 | 64.3 | 78.2 | 93.4 | 108.9 | 122.8 | 131.1 |

| 140 | 63.3 | 73.2 | 89.8 | 108.2 | 126.5 | 143.1 | 153.0 |

| 150 | 74.9 | 87.0 | 107.3 | 129.8 | 152.2 | 172.5 | 184.6 |

| 160 | 90.1 | 105.3 | 130.7 | 159.0 | 187.2 | 212.6 | 227.8 |

| 170 | 107.5 | 127.0 | 159.7 | 196.1 | 232.4 | 265.1 | 284.7 |

| 180 | 120.7 | 146.1 | 188.7 | 236.1 | 283.4 | 326.0 | 351.5 |

| 190 | 125.1 | 158.3 | 213.9 | 275.6 | 337.4 | 392.9 | 426.2 |

RVEDV right ventricular end-diastolic volume.

Table 4.

Centiles of the RVESV for both genders. Data are shown in ml.

| RVESV (mL) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body height (cm) | 5 | 10 | 25 | 50 | 75 | 90 | 95 |

| 90 | 16.9 | 19.1 | 23.3 | 28.7 | 35.1 | 41.6 | 45.9 |

| 100 | 18.5 | 20.8 | 25.3 | 31.1 | 37.9 | 45.1 | 49.9 |

| 110 | 20.4 | 22.9 | 27.7 | 34.0 | 41.5 | 49.5 | 54.9 |

| 120 | 23.0 | 25.7 | 30.9 | 37.92 | 46.4 | 55.4 | 61.6 |

| 130 | 26.4 | 29.5 | 35.4 | 43.3 | 53.0 | 63.5 | 70.8 |

| 140 | 31.0 | 34.6 | 41.5 | 50.8 | 62.5 | 75.3 | 84.3 |

| 150 | 37.0 | 41.2 | 49.7 | 61.3 | 76.1 | 92.8 | 104.7 |

| 160 | 44.3 | 49.6 | 60.4 | 75.6 | 95.5 | 118.8 | 135.9 |

| 170 | 53.1 | 60.0 | 74.1 | 94.8 | 123.2 | 158.0 | 184.7 |

| 180 | 63.1 | 72.0 | 90.6 | 119.2 | 160.5 | 214.8 | 258.8 |

| 190 | 74.2 | 85.4 | 109.7 | 148.9 | 209.4 | 295.8 | 371.5 |

RVESV right ventricular end-systolic volume.

Table 5.

Centiles of the RVSV for both genders. Data are shown in ml.

| RVSV (mL) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body height (cm) | 5 | 10 | 25 | 50 | 75 | 90 | 95 |

| 90 | 20.7 | 23.4 | 27.8 | 32.7 | 37.7 | 42.1 | 44.8 |

| 100 | 20.8 | 23.9 | 29.0 | 34.7 | 40.4 | 45.5 | 48.5 |

| 110 | 22.1 | 25.7 | 31.5 | 38.1 | 44.6 | 50.5 | 54.1 |

| 120 | 24.8 | 28.8 | 35.6 | 43.2 | 50.7 | 57.5 | 61.5 |

| 130 | 27.9 | 32.5 | 40.4 | 49.0 | 57.7 | 65.5 | 70.2 |

| 140 | 32.1 | 37.5 | 46.5 | 56.5 | 66.5 | 75.5 | 80.9 |

| 150 | 37.7 | 43.9 | 54.3 | 65.8 | 77.4 | 87.7 | 93.9 |

| 160 | 44.2 | 51.3 | 63.3 | 76.6 | 89.8 | 101.9 | 108.9 |

| 170 | 51.1 | 59.3 | 73.1 | 88.3 | 103.6 | 117.4 | 125.6 |

| 180 | 57.6 | 67.1 | 82.9 | 100.6 | 118.2 | 134.0 | 143.5 |

| 190 | 63.4 | 74.3 | 92.6 | 112.9 | 133.1 | 151.4 | 162.3 |

RVSV right ventricular stroke volume.

Table 6.

Centiles of the RVEDMM for both genders. Data are shown in g.

| RVEDMM (g) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 5 | 10 | 25 | 50 | 75 | 90 | 95 |

| 3 | 16.9 | 19.5 | 23.8 | 28.6 | 33.4 | 37.7 | 40.3 |

| 4 | 18.1 | 20.9 | 25.7 | 30.9 | 36.2 | 40.9 | 43.7 |

| 5 | 19.4 | 22.5 | 27.7 | 33.5 | 39.2 | 44.4 | 47.5 |

| 6 | 20.8 | 24.2 | 29.9 | 36.3 | 42.6 | 48.3 | 51.8 |

| 7 | 22.4 | 26.1 | 32.4 | 39.4 | 46.3 | 52.6 | 56.4 |

| 8 | 24.0 | 28.1 | 35.0 | 42.6 | 50.3 | 57.2 | 61.3 |

| 9 | 25.6 | 30.2 | 37.7 | 46.1 | 54.6 | 62.1 | 66.7 |

| 10 | 27.4 | 32.4 | 40.7 | 49.9 | 59.2 | 67.5 | 72.5 |

| 11 | 29.2 | 34.7 | 43.9 | 54.0 | 64.2 | 73.3 | 78.8 |

| 12 | 31.2 | 37.2 | 47.2 | 58.4 | 69.5 | 79.6 | 85.6 |

| 13 | 33.1 | 39.7 | 50.7 | 63.0 | 75.2 | 86.3 | 92.9 |

| 14 | 34.9 | 42.2 | 54.3 | 67.8 | 81.2 | 93.4 | 100.6 |

| 15 | 36.6 | 44.6 | 57.9 | 72.7 | 87.5 | 100.8 | 108.9 |

| 16 | 38.1 | 46.8 | 61.5 | 77.7 | 94.0 | 108.6 | 117.4 |

| 17 | 39.2 | 48.8 | 64.9 | 82.8 | 100.6 | 116.7 | 126.3 |

| 18 | 39.9 | 50.5 | 68.2 | 87.8 | 107.5 | 125.1 | 135.7 |

| 19 | 40.3 | 51.9 | 71.34 | 92.9 | 114.5 | 133.9 | 145.5 |

| 20 | 40.3 | 53.0 | 74.4 | 98.1 | 121.8 | 143.1 | 155.9 |

| 21 | 39.8 | 53.8 | 77.2 | 103.3 | 129.3 | 152.7 | 166.8 |

| 22 | 38.7 | 54.1 | 79.9 | 108.5 | 137.1 | 162.8 | 178.3 |

RVEDMM right ventricular end-diastolic mass.

In a supplement, we provide additional percentile curves and tables for females and males separately (Supplement Figs. 1 and 2, Supplement Table 1-8).

3.2. Intra- and interobserver reproducibility

Intra- and interobserver reproducibility measured by intraclass correlation was excellent for RV volumes, RVEF, and RVEDMM. The ICC values ranged from 0.94 to 0.99. Standard error of the measurement and minimal detectable difference were calculated and are shown in Supplement Table 9.

4. Discussion

In this study, we provide CMR reference values for RV volumetric variables derived from a large cohort of pediatric and young adult HLHS patients. Furthermore, we were able to show that the strongest anthropometric influence factor on RV volumes is body height whereas RV mass is highly associated with patient age.

As the population of HLHS patients is growing and aging, there is increasing concern about the performance of the systemic RV. Previous imaging studies, including research from this group, have shown that ventricular function in HLHS patients declines over the years [5], [14] although changes in functional parameters in pediatric and adolescent patients are relatively small [5], [6]. Others have shown that CMR-derived variables seem to be predictive of long-term outcomes in Fontan patients [14], [15], [16], [17]. It was shown that increased indexed end-diastolic volumes (EDVi) and rapid increase in EDVi predict adverse outcomes [14], [16], [17]. Even though these studies showed that CMR volumetry is helpful in guiding care of single ventricle patients with Fontan circulation [14], [15], [16], [17], mixed cohorts of Fontan patients were included with only a proportion being HLHS patients. As long-term outcomes in HLHS patients seem to be worse compared to other Fontan patients [18], it seems appropriate to consider this particularly vulnerable patient group separately and to provide reference values on RV size and function on this population at risk.

Regression results from this study show that height is strongly associated with RV volumes compared to other anthropometric or demographic parameters. Similar results were shown in a recently published study from our group in a cohort of healthy children and adolescents that showed that particularly height but also weight showed strong associations with ventricular volumes [12]. Furthermore, It is known that extreme weight (obesity or underweight) can affect CMR results [19]. In addition, in HLHS patients altered body composition with low skeletal muscle mass is a concern and indexing using BSA might be misleading [20]. Height or the calculation of the ideal BSA might therefore be more appropriate for indexing of CMR-derived volumetric measurements [19]. Taking into account these consideration, our results [12], and research from other groups [19], [21], it was decided to create reference curves and tables with respect to body height of HLHS patients. RV mass, however, was most strongly associated with patient age suggesting that time might be more important for RV myocardial changes. No reference curves or tables for RVEF are provided because similar to studies in healthy children the model quality from multiple linear regression analysis was insufficient [12]. Instead, mean values for different HLHS age groups are given (see Section 3) which indeed do not differ strongly in patients between 1 and 25 years of age.

Interobserver and intraobserver variability demonstrated excellent agreement for RV volumetry parameters. An explanation might be the RV contouring approach that included the papillary muscles and the trabeculations, into the blood pool. Although excluding the papillary muscles and trabeculations from the blood pool might be more accurate [22], it has been shown that the inclusion of trabeculations and papillary muscles into the ventricular volume showed a better reproducibility for measurements of systemic RV volumes [23]. Especially the often highly trabeculated RV apex in HLHS patients might decrease the reproducibility when excluding trabeculations from the blood pool. Artificial intelligence (AI) contouring software tools might improve volumetry in HLHS and other single-ventricle patients. However, the currently commercially available AI contouring tools are not adequately trained for the ventricular contouring of the single right ventricle [24].

5. Limitations

This is a retrospective single-center study with all its inherent limitations, including the limited number of included HLHS patients and different HLHS types. The LMS method used for calculating the reference curves and tables is able to handle small sample sizes.

There are more male than female patients in the study cohort and this might have affected the study results. However, the constitution of the study population reflects the fact that HLHS is more common in male newborns [3], [25].

When using the provided reference values, the volumetric method must be considered. In this study, volumetric variables were measured from short-axis stacks and contouring was performed with inclusion of the papillary muscles and trabeculations into the blood pool. Therefore, the reference values provided here should only be used for comparison with data analyzed with a similar approach.

Furthermore, the change in scanner and sequence type and accordingly sequence parameters might have affected the volumetric results. In addition, the aortopulmonary collaterals were not studied.

Finally, we did not analyze relationships between CMR-derived variables and surgical parameters as well as clinical outcomes as this was not the purpose of this study.

6. Conclusions

CMR-derived RV volumes in HLHS patients are most strongly associated with patient height and RV mass is associated with patient age. Disease-specific CMR reference values are provided which should help to improve clinical reporting, future HLHS research, and ultimately patient care.

Funding

None.

Author contributions

Inga Voges: Writing – original draft, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Dominik Daniel Gabbert: Writing – review and editing, Supervision, Methodology. Anselm Uebing: Writing – review and editing, Supervision. Sylvia Krupickova: Writing – review and editing, Supervision. Amke Caliebe: Writing – review and editing, Validation, Methodology, Formal analysis. Andrik Ballenberger: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation.

Ethics approval and consent

The study was approved by the Local Research Ethics Committee. Parents or guardians signed a written consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Declaration of competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.jocmr.2024.101038.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material.

.

Supplementary material.

.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Feinstein J.A., Benson D.W., Dubin A.M., Cohen M.S., Maxey D.M., Mahle W.T., et al. Hypoplastic left heart syndrome: current considerations and expectations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:S1–S42. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Best K.E., Miller N., Draper E., Tucker D., Luyt K., Rankin J. The improved prognosis of hypoplastic left heart: a population-based register study of 343 cases in England and Wales. Front Pedia. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.635776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wald R.M., Mertens L.L. Hypoplastic left heart syndrome across the lifespan: clinical considerations for care of the fetus, child, and adult. Can J Cardiol. 2022;38:930–945. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2022.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rychik J., Atz A.M., Celermajer D.S., Deal B.J., Gatzoulis M.A., Gewillig M.H., et al. Evaluation and management of the child and adult with fontan circulation: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;140:e234–e284. doi: 10.1161/cir.0000000000000696. Cir0000000000000696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kanngiesser L.M., Freitag-Wolf S., Boroni Grazioli S., Gabbert D.D., Hansen J.H., Uebing A.S., et al. Serial assessment of right ventricular deformation in patients with hypoplastic left heart syndrome: a cardiovascular magnetic resonance feature tracking study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11 doi: 10.1161/jaha.122.025332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sobh M., Freitag-Wolf S., Scheewe J., Kanngiesser L.M., Uebing A.S., Gabbert D.D., et al. Serial right ventricular assessment in patients with hypoplastic left heart syndrome: a multiparametric cardiovascular magnetic resonance study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2021;61:36–42. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezab232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawel-Boehm N., Hetzel S.J., Ambale-Venkatesh B., Captur G., Francois C.J., Jerosch-Herold M., et al. Reference ranges (“normal values”) for cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) in adults and children: 2020 update. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2020;22:87. doi: 10.1186/s12968-020-00683-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Voges I., Giordano R., Koestenberg M., Marchese P., Scalese M., Ait-Ali L., et al. Nomograms for cardiovascular magnetic resonance measurements in the pediatric age group: to define the normal and the expected abnormal values in corrected/palliated congenital heart disease: a systematic review. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2019;49:1222–1235. doi: 10.1002/jmri.26614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thiele H., Paetsch I., Schnackenburg B., Bornstedt A., Grebe O., Wellnhofer E., et al. Improved accuracy of quantitative assessment of left ventricular volume and ejection fraction by geometric models with steady-state free precession. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2002;4:327–339. doi: 10.1081/jcmr-120013298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.RCT . R Foundation for Statistical Computing,; Vienna, Austria: 2020. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cole T.J., Green P.J. Smoothing reference centile curves: the LMS method and penalized likelihood. Stat Med. 1992;11:1305–1319. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780111005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Voges I., Caliebe A., Hinz S., Boroni Grazioli S., Gabbert D.D., Daubeney P.E.F., et al. Pediatric cardiac magnetic resonance reference values for biventricular volumes derived from different contouring techniques. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2022;57:774–788. doi: 10.1002/jmri.28299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rigby R.A.S.D. Generalized additive models for location, scale and shape (with discussion) Appl Stat. 2005;54:507–554. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghelani S.J., Lu M., Sleeper L.A., Prakash A., Castellanos D.A., Clair M., et al. Longitudinal changes in ventricular size and function are associated with death and transplantation late after the Fontan operation. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2022;24:56. doi: 10.1186/s12968-022-00884-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alsaied T., Bokma J.P., Engel M.E., Kuijpers J.M., Hanke S.P., Zuhlke L., et al. Factors associated with long-term mortality after Fontan procedures: a systematic review. Heart. 2017;103:104–110. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2016-310108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghelani S.J., Harrild D.M., Gauvreau K., Geva T., Rathod R.H. Comparison between echocardiography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in predicting transplant-free survival after the Fontan operation. Am J Cardiol. 2015;116:1132–1138. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rathod R.H., Prakash A., Kim Y.Y., Germanakis I.E., Powell A.J., Gauvreau K., et al. Cardiac magnetic resonance parameters predict transplantation-free survival in patients with Fontan circulation. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;7:502–509. doi: 10.1161/circimaging.113.001473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson W.M., Valente A.M., Hickey E.J., Clift P., Burchill L., Emmanuel Y., et al. Outcomes of patients with hypoplastic left heart syndrome reaching adulthood after Fontan palliation: multicenter study. Circulation. 2018;137:978–981. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.117.031282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simpson S.A., Field S.L., Xu M., Saville B.R., Parra D.A., Soslow J.H. Effect of weight extremes on ventricular volumes and myocardial strain in repaired tetralogy of Fallot as measured by CMR. Pedia Cardiol. 2018;39:575–584. doi: 10.1007/s00246-017-1793-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baldini L., Librandi K., D'Eusebio C., Lezo A. Nutritional management of patients with Fontan circulation: a potential for improved outcomes from birth to adulthood. Nutrients. 2022;14 doi: 10.3390/nu14194055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maskatia S.A., Spinner J.A., Nutting A.C., Slesnick T.C., Krishnamurthy R., Morris S.A. Impact of obesity on ventricular size and function in children, adolescents and adults with Tetralogy of Fallot after initial repair. Am J Cardiol. 2013;112:594–598. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fratz S., Chung T., Greil G.F., Samyn M.M., Taylor A.M., Valsangiacomo Buechel E.R., et al. Guidelines and protocols for cardiovascular magnetic resonance in children and adults with congenital heart disease: SCMR expert consensus group on congenital heart disease. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2013;15:51. doi: 10.1186/1532-429x-15-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winter M.M., Bernink F.J., Groenink M., Bouma B.J., van Dijk A.P., Helbing W.A., et al. Evaluating the systemic right ventricle by CMR: the importance of consistent and reproducible delineation of the cavity. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2008;10:40. doi: 10.1186/1532-429x-10-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karimi-Bidhendi S., Arafati A., Cheng A.L., Wu Y., Kheradvar A., Jafarkhani H. Fully‑automated deep‑learning segmentation of pediatric cardiovascular magnetic resonance of patients with complex congenital heart diseases. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2020;22:80. doi: 10.1186/s12968-020-00678-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McBride K.L., Marengo L., Canfield M., Langlois P., Fixler D., Belmont J.W. Epidemiology of noncomplex left ventricular outflow tract obstruction malformations (aortic valve stenosis, coarctation of the aorta, hypoplastic left heart syndrome) in Texas, 1999-2001. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2005;73:555–561. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material.

Supplementary material.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.