Abstract

“Cases of SCMR” is a case series on the SCMR website (https://www.scmr.org) for the purpose of education. The cases reflect the clinical presentation, and the use of cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) in the diagnosis and management of cardiovascular disease. The 2022 digital collection of cases are presented in this manuscript.

Keywords: COVID-19, Coronary artery aneurysm, Cardio-oncology, Metastatic disease, Congenital Heart disease, Myocarditis, Vaccine associated myocarditis, Myocardial. infarction, Viability, Arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy, Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, Takotsubo, Hydatid disease

1. Introduction

It is a pleasure to present the Cases of Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance 2022 case series. Thank you to our fabulous team of Associate Editors and Reviewers for bringing such commitment, enthusiasm, and valuable experience and knowledge to Cases of SCMR. The United States, Europe, Australia, Asia and the Middle East contributed to the 2022 cases. These showcased pediatric and adult congenital heart disease (CHD), cardiomyopathies, cardiac masses, coronary anomalies and disease, and the impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection and vaccination. All cases demonstrated the importance of cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) in assessing and diagnosing cardiovascular disease, and thus providing essential information for clinical management. Please enjoy these cases, and we look forward to more new and exciting cases in the future. Please submit to https://scmr.org/page/SubmitCase. Cases that demonstrate the utility of CMR and its complimentary role to other imaging modalities are appropriate for submission [1], [2], [3].

2. Case 1: An infant with giant coronary artery aneurysm due to multisystem inflammatory syndrome following COVID-19

2.1. Clinical history

An eight-month-old boy with a history of recent COVID-19 infection (with positive real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test one month before presentation) was referred with symptoms of tachycardia, poor feeding, and respiratory distress. His symptoms for COVID-19 infection (one month before presentation) were mild fever, conjunctivitis, restlessness. Two other family members also tested positive for COVID-19. Conservative treatment had been considered due to his mild to moderate symptoms. Physical examination revealed fever (39 °C lasting more than 72 hours), faint friction rub, tachycardia, respiratory distress, and conjunctivitis as well as symptoms of gastroenteritis including mild diarrhea and abdominal pain. Laboratory data included an elevated C-reactive protein (80 mg/L; normal < 9 mg/L), elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (90 mm/hr; normal < 10 mm/hr), serum procalcitonin level of 1.25 ng/dl (normal <5 ng/dl), D-dimer of 2.56 ng/dl (normal < 50000 ng/dl), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level of 1700 U/L (normal 200 U/L), leukocytosis with 16.7 k/dl white blood cells (normal < 1.1 k/dl) and 900 lymphocyte count (normal 850 – 4800), and elevated cardiac troponin I level (2.13 ng/dL; normal range <0.03 ng/dL). The patient was treated for a diagnosis of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) following COVID-19 with prednisolone, intravenous immune globulin (IVIG), and aspirin. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) demonstrated a large pericardial effusion with evidence of tamponade by early diastolic right ventricular (RV) and right atrial (RA) collapse and septal bounce, and moderately reduced left ventricular (LV) systolic function (LV ejection fraction (LVEF) = 40%). After percutaneous pericardiocentesis, the patients’ symptoms alleviated and CMR was performed.

2.2. CMR findings

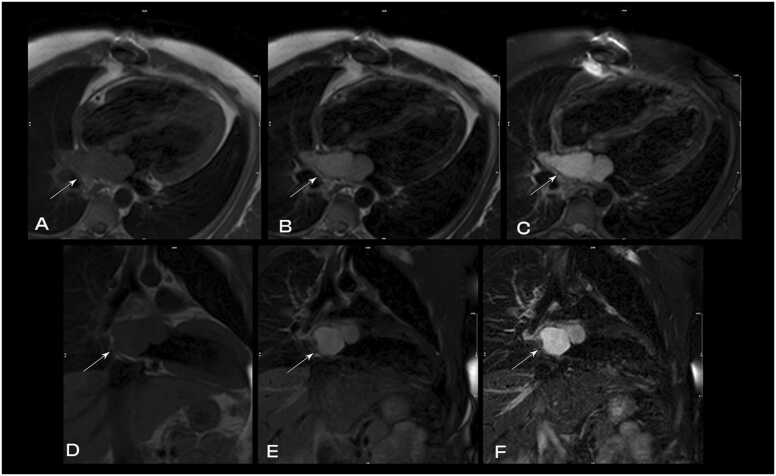

CMR was performed at 1.5 T (Avanto, Siemens Healthineers AG, Erlangen, Germany). Cine images revealed mild pericardial effusion and a giant aneurysm in the proximal segment of the left anterior descending artery (LAD) (Additional Movie Files 1 and 2). Using T2-weighted imaging, myocardial edema was also depicted (Fig. 1). Possible mid to epicardial late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) in the basal anterior and inferolateral wall was evident (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Case 1. Fig. 1. T2-weighted (T2w) double inversion recovery four chamber view. There is evidence of myocardial edema in the lateral left ventricular (LV) wall.

Fig. 2.

Case 1. Fig. 2. Short axis stack (A-C) and four (D), three (E), two (F) chamber late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) imaging. Possible mid to epicardial hyperenhancement is seen in the basal anterior and inferolateral wall was evident.

Supplementary material related to this article can be found online at doi:10.1016/j.jocmr.2023.100007.

The following is the Supplementary material related to this article Movie 1, Movie 2..

Case 1 Movie 1. Balanced steady-state free precession (bSSFP) cine coronal plane. A large aneurysm of LAD (green arrow) coronary artery next to the pulmonary artery is present. The giant aneurysm of the LAD has a comparable diameter to adjacent pulmonary artery.

Case 1 Movie 2. Short axis bSSFP cine at the base. The giant aneurysm of the LAD can be seen in the interventricular groove (red arrow).

2.3. Conclusion

Based on the ward policy to visualize possible clots within the coronary aneurysm and any potential congenital anomalies, the pediatric cardiologists obtained a computed tomography (CT) angiogram (CTA), confirming the aneurysmal dilation of the left main coronary artery (5 mm diameter), and multiple fusiform aneurysms with giant aneurysm at proximal portion (10 mm diameter) were depicted in the LAD (Fig. 3). Moreover, multiple fusiform aneurysms along the left circumflex coronary artery (LCx) (6.3 mm diameter) and fusiform dilation of origin of the right coronary artery (RCA; 3.7 mm diameter) were depicted (Additional Movie File 3).

Fig. 3.

Case 1. Fig. 3. Axial contrast-enhanced cardiac computed tomography (CT) angiography (CTA). Aneurysmal dilation of the left main coronary artery at 5 mm diameter, and multiple fusiform aneurysms in the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery with a giant aneurysm (10 mm diameter) at the proximal portion were depicted.

Supplementary material related to this article can be found online at doi:10.1016/j.jocmr.2023.100007.

The following is the Supplementary material related to this article Movie 3..

Case 1 Movie 3. Shaded surface display volume rendering creating a 3D visual illustration of CT volumetric data of the heart. Multiple fusiform aneurysms of coronary arteries are depicted.

Giant and widespread coronary artery aneurysms in an infant following COVID-19 infection are rarely reported in the literature; however, considering the possibility of fatal consequences, due regard should be given to this phenomenon. Moreover, previously, coronary artery aneurysms were depicted with coronary CMR angiography (CCMRA), nevertheless, in this case, giant coronary artery aneurysms were detected in CMR cine balanced steady state free precession (bSSFP) images. Subsequently treatment with infliximab, heparin, and warfarin was added to the patient’s treatment regime due to the coronary artery involvement, resulting in partial response over two months, and the patient continues to be followed up.

2.4. Perspective

Although COVID-19 is demonstrated to be less severe in children compared to adults, the reports of some devastating and fatal complications following COVID-19 in children and adolescents have generated considerable concern and the number of such reports is rapidly increasing [4]. Kawasaki disease (mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome) is characterized as the most common cause of coronary artery aneurysms in children [5], [6], [7]. Several studies have reported a Kawasaki-like illness following COVID-19 called MIS-C [8], [9], [10]. Although it is similar to Kawasaki disease and toxic shock syndrome, it does not have all features to fulfill the criteria of Kawasaki disease according to the American Heart Association (AHA) Kawasaki guideline (fever plus four of five criteria) [8].

The full spectrum of MIS-C is not clearly described yet but severe forms of the disease can lead to multiple organ failures including neurologic involvement and cardiogenic or vasoplegic shock [11]. Coronary artery dilation and aneurysm formation are reported in 14 - 48% of patients with MIS-C[12], [13], [14].

In the presented case the vasculitis and inflammatory symptoms of the patient overlapped with those of COVID-19, leading to late diagnosis and treatment initiation and subsequently widespread aneurysm formation in the coronary arteries. Two recent studies using CMR imaging in adult patients after recovering from COVID-19 have reported cardiovascular abnormalities in 56 to 78% of middle-aged adults [15]. In another similar study, 15% of college athletes developed cardiovascular abnormalities in CMR imaging. In contrast, cohort studies on children using CMR for follow-up of the patients revealed fewer complications. Webster et al. reported no significant cardiac disease by CMR in a small pediatric cohort of patients at least one month after recovering from acute symptomatic COVID-19 infection or MIS-C [16]. In another study after midterm follow-up (median of 7 months) in 16 children no patients had LGE in CMR imaging [17]. Blondiaux et al. reported diffuse myocardial edema on T2 short tau inversion recovery (STIR) sequences and native T1 mapping in four children after MIS-C, with no evidence of LGE [18].

Evidence is still scarce but rapidly emerging in the literature about the importance of performing CMR in patients with MIS-C. CMR can be considered as a safe and radiation-free imaging modality for evaluation of these patients – in particular the infants and children- and to identify myocarditis as well as functional abnormalities, myocardial ischemia and myocardial infarction (MI) [19]. CMR which is the mainstay in the diagnosis of suspected myocarditis helped us detect the myocarditis in our patient that would be missed if the workups were performed using other routine diagnostic modalities. Our case demonstrated the feasibility of detection of coronary artery aneurysm in CMR cine bSSFP images, especially those with larger sizes. Therefore, due regard should be given to the existence of possible coronary artery aneurysms upon evaluation of cine bSSFP images. Moreover, CCMRA can also be considered for the determination of the origin and course of coronary arteries in case of suspected coronary artery disorders in children. Several studies advocate the accuracy of CCMRA for the detection of coronary artery aneurysms in patients with Kawasaki disease[20], [21]. This technique can be regarded in such cases as a non-invasive and radiation-free imaging alternative when TTE image quality is insufficient, subsequently reducing the need for serial x-ray coronary angiography.

The CMR of Case 1 (Additional File CMR Link, https://www.cloudcmr.com/8757–1973-2018–0101/).

3. Case 2: A case of metastatic choroid malignant melanoma

3.1. Clinical history

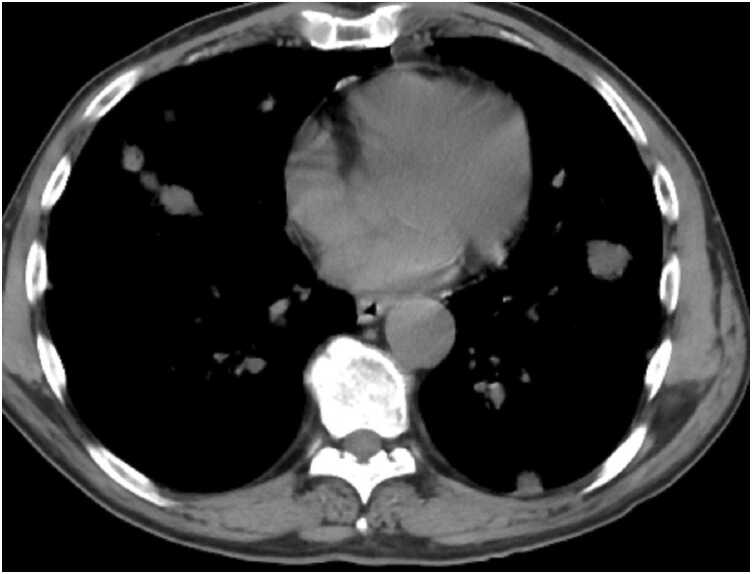

A 63-year-old male with a known past medical history of left choroid melanoma presented with increasing dyspnea, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, ongoing tobacco use, and progressive 30-pound weight loss and associated anorexia. Lab work was obtained indicating hyponatremia with a sodium of 128 mg/dL (normal 136–145 mg/dL), elevated LDH of 293 (normal < 250 U/L), and a leukocytosis of 21,300 k/uL (normal < 11,000 k/uL). A chest CT obtained two months prior to presentation identified numerous diffuse nodules throughout the lung fields with associated mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy (Fig. 4). A TTE showed a large (1.9 by 1.6 cm) echogenic mass in the LV attached to the anterior septal wall (Fig. 5). A second mass was located in the RV, but difficult to completely visualize (Fig. 5). CMR was requested to better define and characterize the masses.

Fig. 4.

Case 2. Fig. 1. Chest CT without contrast in the axial plane. There are multiple lung masses present.

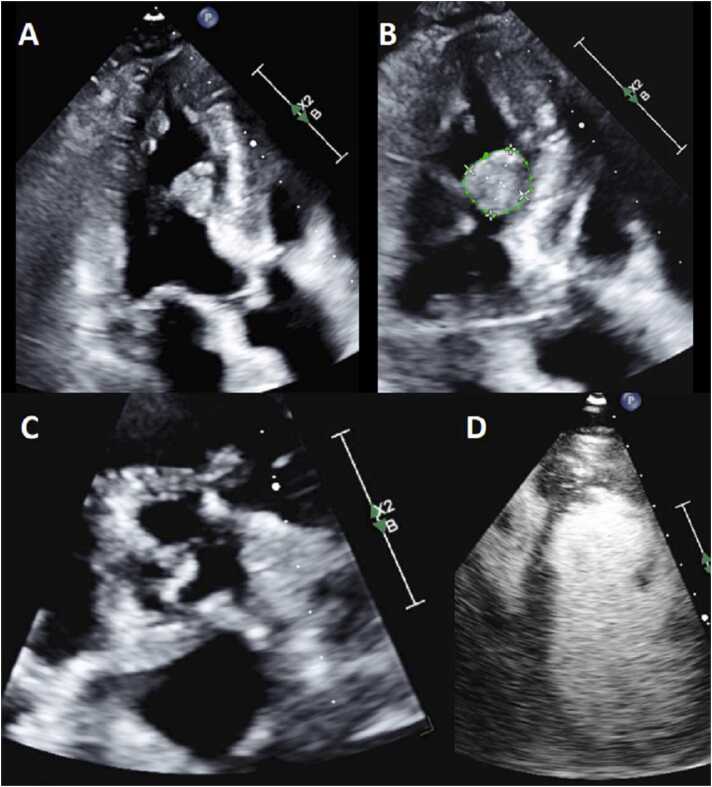

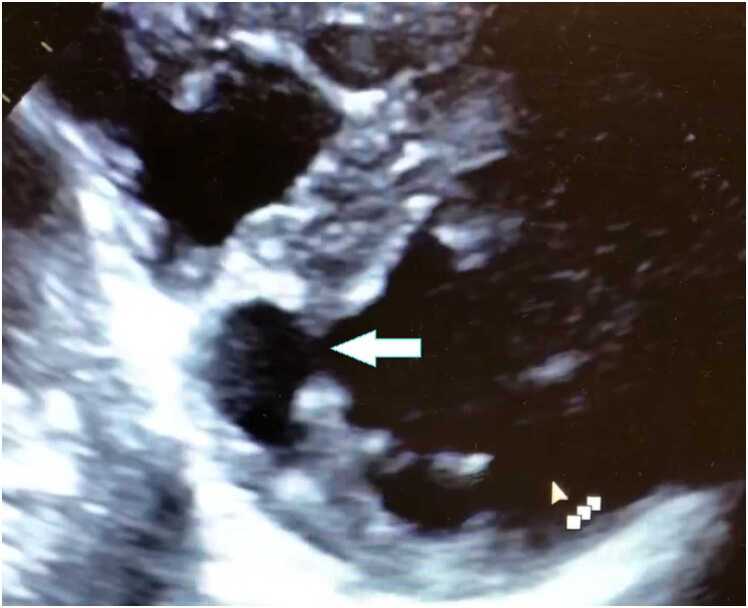

Fig. 5.

Case 2. Fig. 2. Transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) apical three chamber view (A,B), parasternal short axis (C), and a modified parasternal short axis with contrast enhancement (D). There is a large mass attached to the interventricular septum.

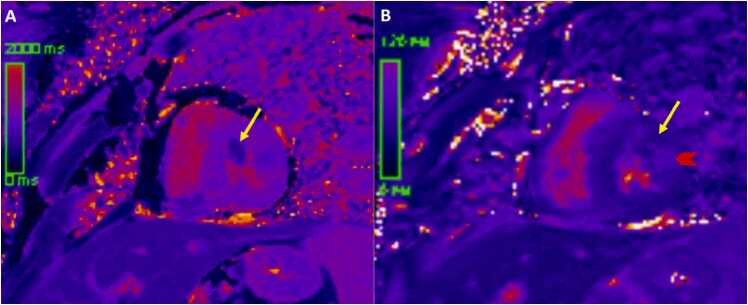

3.2. CMR findings

CMR performed at 1.5 T (Sola, Siemens Healthineers AG, Erlangen, Germany) demonstrated multiple intramyocardial masses in the interatrial septum, RA, LV, and RV; the largest mass measuring 16.5×13 mm in the lateral LV wall (Additional Movie File 4). An anterior mass bulges into the LV cavity and an additional mass is protruding into the RV outflow tract (RVOT) from the anterior septum. These heterogeneous, bulky, masses are hyperintense on cine bSSFP as well as T2 and T1 black blood imaging (Fig. 6). They were highly vascular on first pass rest perfusion (Additional Movie File 5 Case 2 Movie 2) and had profound enhancement on LGE imaging (Fig. 7), extending into the subendocardial and subepicardial layers. The appearance, however, was felt likely due to the native T1 times being significantly shortened by the presence of melanin, rather than profound uptake of gadolinium within the tumors. This same phenomenon can also be seen with mitral annular calcification with caseous necrosis with short native T1 times. Similar masses were also noted along the pericardium, as well as innumerably disseminated throughout the lung fields that have the same tissue characterization as the myocardial metastases. Mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy was also present. A low native T1 time of approximately 700ms was observed (Fig. 8). A moderate sized (5–10 mm) circumferential pericardial effusion was present. Real-time, free breathing sequences were utilized when possible due to the patient’s dyspnea and inability to adequately perform breath holds.

Fig. 6.

Case 2. Fig. 3. T1 weighted (T1w; A,B) and T2w (C,D) spectral adiabatic inversion recovery (SPAIR) images in mid short axis (A,C) and four chamber (B,D) views. Multiple hyperlucent masses in the LV and right ventricle (RV) on both T1 and T2 weighted images are present.

Fig. 7.

Case 2. Fig. 4. LGE in the basal short axis (A), two chamber (B), and four chamber (C) views. Multiple myocardial masses (arrows) with hyperenhancement are present.

Fig. 8.

Case 2. Fig. 5. Native T1 (A) and T2 (B) parametric mapping images from the mid short axis view. The measured T1 times of the myocardial masses (arrow) are low and T2 mapping times are variable with the yellow arrow at 52 msec and red arrow at 75 msec.

Supplementary material related to this article can be found online at doi:10.1016/j.jocmr.2023.100007.

The following is the Supplementary material related to this article Movie 4, Movie 5..

Case 2 Movie 1. Cine bSSFP short axis stack. There are multiple intramyocardial masses in the LV and RVs.

Case 2 Movie 2. Four chamber (A) and mid short axis (B) rest perfusion imaging. There is brisk uptake of contrast of the myocardial masses on first pass perfusion.

3.3. Conclusion

CMR findings were consistent with an underlying malignant process suggestive of a metastatic disease from the known prior primary left choroid melanoma. The presence of highly-melanin rich metastatic tumors affects T1 relaxation times. T1 relaxation times shorten and recover their signal faster than the surrounding normal myocardium that results in high signal on T1-weighted fast spin echo sequences. This is a quintessential finding that helps differentiate malignant melanoma from other metastatic cardiac tumors. T2-weighted images in this case also exhibited high signal which may or may not be elevated and is also dependent on the amount of surrounding edema. The T1 shortening effects of melanin dominate over the T1 prolongating effects of myocardial inflammation and edema. Malignant melanoma is unique in that it is one of the times where native T1 and T2 times are discordant despite the evidence of edema and necrosis. Given the highly vascularized nature of these tumors, the first pass perfusion is usually preserved, and appears as bright as normal myocardium due to high vascularity. A pericardial effusion is also present in most cases and traditionally exhibits hemorrhagic features. These complex features of the fluid consist of intermediate T2-weighted (T2w) signal intensity and high T1-weighted (T1w) signal intensity. The bSSFP cine images may identify loculations including fibrin strands and thrombi from the dissemination and seeding of the pericardium.

A suspicion of metastatic malignant melanoma was raised from the initial work-up given the findings on the chest CT scan and TTE. Given persistence of the patient’s symptoms in the setting of concerning findings on CMR suggesting disseminated malignant melanoma, he was admitted to the hospital for further management by hematology/oncology to initiate immunotherapy.

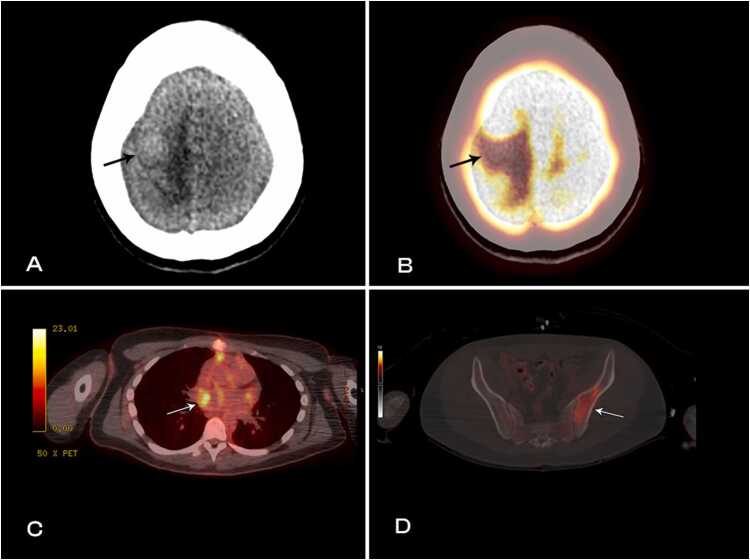

Based on CMR findings, a full body fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) CT imaging was performed confirming widespread metastatic disease including the central nervous system. The diagnosis of metastatic malignant melanoma was made and further management with nivolumab, ipilimumab, and allopurinol was implemented. The patient was discharged from the hospital and has elected to continue treatment as an outpatient.

3.4. Perspective

CMR tissue characterization is beneficial when identifying the etiology of myocardial masses. The dimensions, morphology, location and any associated hemodynamic or mass effect, mobility, vascularity, infiltration patterns, magnetic properties, and the presence of associated sequelae such as effusions can help with differentiating the underlying etiology of cardiac masses. The size of benign tumors rarely surpasses 5 cm [22]. Malignant tumors are more likely to infiltrate into the adjacent structures, extend with irregular borders, and demonstrate associated pericardial effusions [23]. The native magnetic properties of tumors as well as the effects of LGE can aid in non-invasive tissue characterization. All malignant tumors are likely to exhibit LGE and first pass resting perfusion imaging due to their vascularity can aid in differentiating malignancy from cardiac thrombi. Prolonged inversion times of greater than or equal to 422 msec have been shown to aid in the delineation of cardiac thrombi from masses on LGE imaging sequences [22]. When all the above is taken into account, diagnostic accuracy has been as high as 92 to nearly 100% in prior studies published [23].

Metastatic melanoma represents approximately 28% of metastatic malignancies involving the heart; most commonly the RA. This equates to an incidence of about 1–5% [22]. CMR has a pivotal role in the differential diagnosis of melanoma from the other disseminated malignancies given the melanin-rich characteristics of the tumors. These tumors are thought to be spread by hematogenous dissemination in most cases [24]. This results in multiple organ system involvement as seen in our case with the central nervous, pulmonary, lymphatic, and cardiac systems inundated with tumor burden.

The unusual pattern of melanoma and significantly reduced T1 relaxation times resulting in enhanced signal intensity is a hallmark feature differentiating it from other cardiac masses. Although rare, the survival rates are dismal with a 5-year survival rate of 15–20% although the rate of mortality is falling from of all malignant melanomas by 5.7%, annually [25]. The overall mean survival rate for stage 4 malignant melanoma was 9.2 months with a median survival of 6.3 months [26]. CMR aids in the diagnosis of malignant melanoma, and relevant implications on patients’ management, but unfortunately given the increased mortality risk associated with this disease, our patient’s overall prognosis is poor.

The CMR of Case 2 can be found here: https://www.cloudcmr.com/4857–1973-8858–0125/).

4. Case 3: Unguarded mitral orifice with double outlet right ventricle and normally related great arteries: CMR diagnosis (winner of ‘Cases of SCMR’s best case of 2022′)

4.1. Clinical history

This is a case of a 4-month-old girl, product of full term pregnancy and birth weight of 2 kg who was postnatally admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit for 25 days at a remote community hospital. She was subsequently discharged home in stable condition. At 3 months of age, she was referred to our center as a case of CHD.

Upon initial outpatient encounter, the patient’s weight was 2.5 kg with oxygen saturation of 90% in room air. On physical examination, she had subtle dysmorphic features with triangular face, hypertelorism, truncal hypotonia, weak cry and depressed deep tendon reflexes. She had mild tachypnea, a soft systolic ejection murmur at the left upper sternal border and the liver was felt 1 cm below the right costal margin. Her systemic examination was otherwise unremarkable. Electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed sinus rhythm and left axis deviation. Chest X-ray showed enlarged cardiac silhouette with mild central vascular congestion (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Case 3. Fig. 1. Chest x-ray anteroposterior projection. There is cardiomegaly with mild central vascular congestion.

TTE demonstrated situs solitus, levocardia, d-looped ventricles, double outlet right ventricle (DORV) with normally related great arteries, large primum atrial septal defect (ASD), small secundum ASD, and a moderate ventricular septal defect (VSD). Optimal interrogation of the VSD was technically challenging. The LV was suspected to be hypoplastic with mitral atresia and concern for a huge left atrial (LA) appendage (LAA) aneurysm with to and from flow associated with that structure (Fig. 10, Fig. 11, Additional Movie File 6).

Fig. 10.

Case 3. Fig. 2. TTE parasternal short axis (A), subcostal sagittal (B), and apical four chamber (C,D) views. The RV is anterior to the presumed hypoplastic LV, and a large posterior aneurysm is present. There is flow into the presumed left atrial (LA) appendage aneurysm and presumed hypoplastic LV and mitral atresia (MA).

Fig. 11.

Case 3. Fig. 3. TTE apical five chamber view in 2D (A) and color Doppler (B) and subcostal oblique view in 2D (C) and color Doppler (D). The aorta (Ao) arises from the RV. The pulmonary valve (PV) arises from the RV as well.

Supplementary material related to this article can be found online at doi:10.1016/j.jocmr.2023.100007.

The following is the Supplementary material related to this article Movie 6..

Case 3 Movie 1. Apical five chamber TTE view. There is a large, thin-walled, hypocontractile left sided chamber, concerning for a possible giant LA appendage aneurysm.

Understanding the patient's diagnosis and hemodynamics was challenging given the atypical left heart findings. For better evaluation of the “aneurysm” a CMR was performed under general anesthesia.

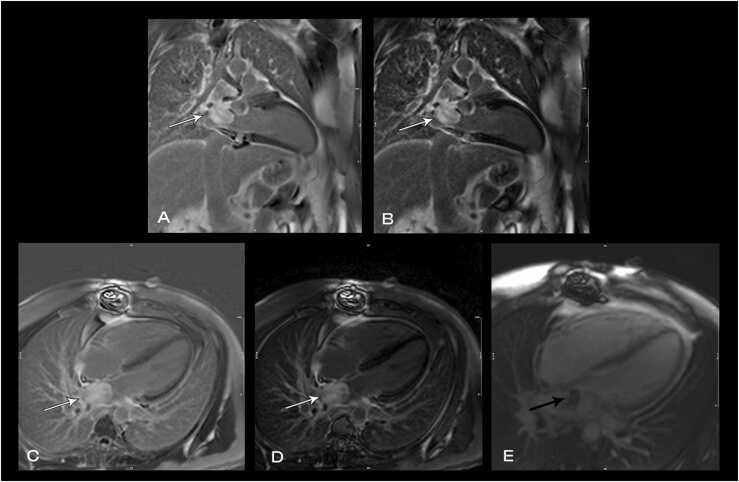

4.2. CMR findings

The study was performed on a 1.5 T CMR system (Avanto, Siemens Healthineers AG, Erlangen, Germany) with the patient's heart rate ranging from 91–100 beats per minute (bpm). Cine bSSFP imaging demonstrated viscero-atrial situs solitus, d-looped ventricles, DORV with normally related great arteries, small (4 mm) outlet VSD and left superior vena cava to an unroofed coronary sinus. Both atria were enlarged with a large primum ASD. The left atrioventricular (AV) junction was patent with dephasing artifacts across but absent mitral valve apparatus including leaflets, chordae and papillary muscles (Additional Movie File 7). The LAA appeared normal.

Supplementary material related to this article can be found online at doi:10.1016/j.jocmr.2023.100007.

The following is the Supplementary material related to this article Movie 7..

Case 3 Movie 2. Cine bSSFP four chamber view. There is a widely patent left atrioventricular junction with dephasing flow artifact present with absent mitral valve leaflets, chordae and papillary muscles.

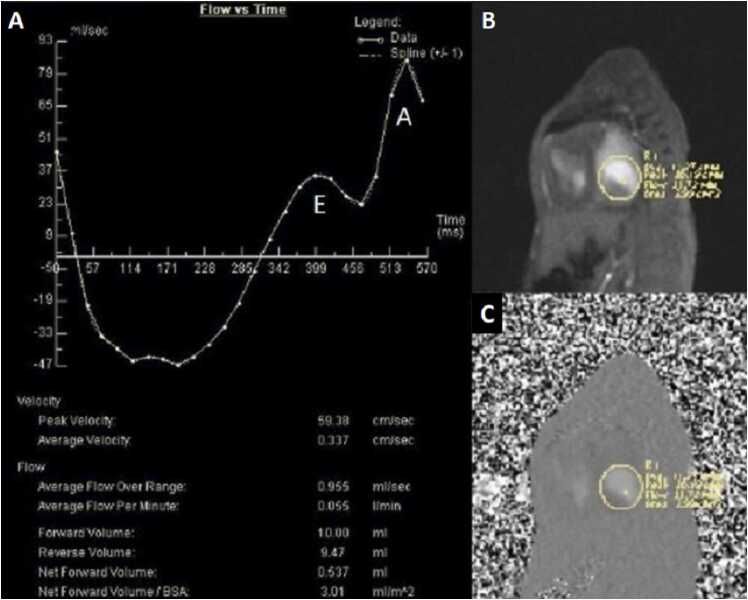

Phase contrast cine imaging demonstrated to-and-fro flow across the mitral annulus with transmitral E/A waveform reversal suggestive of diastolic dysfunction (Fig. 12). There was a net left to right shunt (Qp:Qs =2.4).

Fig. 12.

Case 3. Fig. 4. Flow versus time of the mitral valve annulus inflow (A), gradient echo of the mitral valve annulus en face (B) with corresponding phases contrast (C) image. There is an E and A wave during mitral valve inflow in diastole with flow reversal during systole.

The RV was significantly dilated (RV end-diastolic volume (RVEDV) indexed (RVEDVI) = 126 mL/m2; Z score + 11) with preserved global systolic function (RV ejection fraction (RVEF) 56%) and mild tricuspid regurgitation [27]. The LV was severely dilated (LV end-diastolic volume (LVEDV) indexed (LVEDVI) = 173.5 mL/m2; Z score + 16) with extremely thin anterior, inferior and lateral walls with moderately depressed global systolic function (LVEF 43%; normal 56–70%)) (Additional Move File 8).

The LV anteroseptal and inferoseptal segments had usual thickness and the basal anteroseptal segment connected to the outlet VSD. Following administration of gadolinium contrast, free breathing single shot LGE imaging from an axial projection demonstrated transmural hyperenhancement in the lateral LV wall suggestive of diffuse fibrosis (Fig. 13).

Fig. 13.

Case 3. Fig. 5. Four chamber LGE view. Myocardial fibrosis (arrows) in the lateral wall of the LV.

4.3. Conclusion

CMR findings of patent left AV junction, absent mitral valve apparatus, severely dilated, fibrosed, thin-walled LV in the setting of DORV are consistent with a diagnosis of unguarded mitral orifice (UMO).

4.4. Perspective

UMO is an exceedingly rare congenital cardiac anomaly characterized by absence of mitral valve leaflets, chordae and papillary muscles at the mitral annulus with severe thinning of the LV free wall [28], [29]. Being devoid of any mitral tissue leads to unrestricted to-and-fro flow across the left AV junction.

The etiology of UMO remains unclear. Embryologically, development of the mitral valve takes place between the fourth and fifth weeks of gestation. Mitral leaflets, chordae tendineae and papillary muscles form by undermining of the endomyocardial aspect of the LV inlet which occurs along with immersion of the AV sulcus [30]. Yasukochi et al. hypothesized that anomalies in undermining of the endomyocardial aspect of the LV may occur either by maldevelopment or apoptosis prior to leaflets separation from the ventricular myocardium [28]. This can lead to failure of delamination of valvular leaflets and thinning of ventricular wall, the end point of which is UMO with absence of the LV parietal myocardial layer. Another hypothesis by Howley et al. proposed that a defect in normal mitral valve development may result in valve deformity leading to early development of mitral valve incompetence that could alter normal LV development resulting in thinning and dilation [31].

The few reported cases of UMO in the literature are summarized in Table 1 Case 3 [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37]. Six cases had DORV and pulmonary atresia/stenosis, one DORV and interrupted aortic arch, one transposition and pulmonary atresia, one AV / ventriculoarterial (VA) concordance with hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) and aortic atresia, and one with AV / VA concordance and aortic atresia. Seven of eleven cases did not survive, two with unknown outcome and 2 underwent single ventricle pathway. All reported patients were diagnosed postnatally by TTE except one diagnosed prenatally by fetal echocardiogram.

Table 1.

Case 3. Summary of published cases of unguarded mitral orifice.

| Author (reference) | Year of case report | Age at diagnosis | Initial presentation | Cardiac Diagnosis | Management | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Johnson JN et al. | 2023 | 3 months | Respiratory distress | AV concordant, DORV, normally related great arteries, no aortic/pulmonary stenosis | Comfort care | Died at 4 months |

| Howley et. al. [31] | 2021 | Diagnosed prenatally | Respiratory distress, cyanosis and acidosis directly after birth. Atrial flutter |

Concordant AV and VA connections with aortic atresia | ECMO with bilateral pulmonary artery band (PAB) | Died at day 26 of life. |

| Banerji et. al. [37] | 2020 | Diagnosed after birth | Clinically stable after birth | Dextrocardia, discordant AV connections, DORV with pulmonary atresia. | Proposed a univentricular strategy but parents declined intervention | Unknown |

| Subramanian et al. [33] | 2019 | Postnatally | Cyanosis and respiratory distress | AV concordance, DORV, interrupted aortic arch | Comfort care | Died at home |

| Kishi et. al. [34] | 2017 | Diagnosed after birth | severe hypoxia and bradycardia | Asplenia, DORV, dysplastic tricuspid valve, and pulmonary stenosis. | Supportive | Died on the second day of life |

| Shati, et al. [35] | 2015 | Diagnosed after birth | supraventricular tachycardia | Concordant AV and discordant VA connections, and pulmonary atresia. | Surgical shunt aiming for single ventricle approach | Died postoperatively |

| Su, et. al. [36] | 2014 | Diagnosed after birth | Cyanosis | Concordant AV and VA connection, HLHS and aortic atresia. | Atrial septectomy and bilateral PAB on day 1 of life. Norwood procedure with Sano modification day 5 of life. | Unknown |

| Hwang et. al. [32] | 2010 | Diagnosed after birth | Cyanosis | Discordant AV connections, DORV with pulmonary atresia. | Modified left BTT shunt at 33 days old | Single ventricle pathway |

| Earing et. al. [29] | 2003 | 5 days old | Cyanosis | Discordant AV connections, DORV with pulmonary atresia. | Mee operation at 7 days old. Bidirectional Glenn shunt at 6 months old | Single ventricle pathway |

| Yasukochi et. al. [28] | 1999 | 9 months old | Cyanosis, CHF | Discordant AV connections, DORV with pulmonary stenosis. | At 15 months of age, left BTT shunt. | Died of congestive heart failure (CHF) and ventricular fibrillation at 17 years old. |

| Yasukochi et. al. [28] | 1999 | 9 days old | Cyanosis | Discordant AV connections, DORV with pulmonary stenosis. | Left BTT shunt at 23 days old | Died of CHF and ventricular fibrillation at 13 months old |

We report this unique case of congenital UMO in the setting of viscero-atrial situs solitus, AV concordance and DORV. Unlike other reported cases, the great arteries were normally related without aortic or pulmonary stenosis. The LV was severely dilated with extremely thin free walls and moderately depressed global LV systolic function. In our case, it was challenging to arrive at a definitive diagnosis by TTE and CMR was essential to establish a complete, final diagnosis. Our findings of diffuse fibrosis in the LV free wall has been demonstrated on previous autopsies [34]. To our knowledge, this is the first case of UMO that is reported with CMR images. Due to the patient’s clinical conditions, comfort care was provided for a several weeks after diagnosis. An autopsy was not performed.

The CMR of Case 3 can be found here: https://www.cloudcmr.com/6457–1973-0508–0124/Link does not work - please check.

5. Case 4: Left ventricular diverticulum masquerading as pseudoaneurysm

5.1. Clinical history

A 56-year-old African American male with known essential hypertension presented to the emergency department for an evaluation of elevated home blood pressure readings. On review of symptoms, patient reported mild, intermittent, self-limited, non-radiating mid chest tightness that would last for a few minutes and had been ongoing for past few days. There were no aggravating or relieving factors. Rest of review of symptoms were non-contributory. Patient denied any other medical problems and was currently not taking any medications. Patient denied any use of tobacco, alcohol, or any recreational substance. Family history was significant for history of stroke.

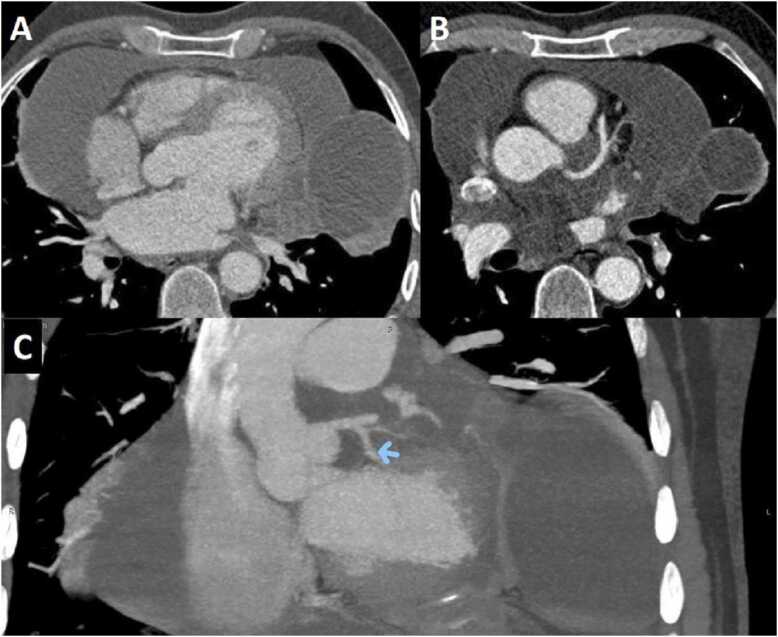

His vitals at presentation showed blood pressure of 175/114 mm Hg, heart rate of 76 beats per minutes, room air oxygen saturation of 96%; the patient was afebrile. Physical examination was within normal limits. His presentation ECG showed non-specific T wave inversions. His blood work including troponin were within normal limits except low-density lipoprotein was abnormal at 183 mg/dl (normal < 130 mg/dl), and D-dimer was minimally elevated. Chest CT with intravenous contrast excluded aortic dissection but demonstrated findings that were deemed concerning for LV pseudoaneurysm (Fig. 14). The patient was admitted for possible acute coronary syndrome and was treated with antihypertensive medications.

Fig. 14.

Case 4. Fig. 1. Coronal view CTA. There is a presumed LV pseudoaneurysm (arrow).

The next morning, repeat troponin had remained normal. TTE showed LV septal abnormality (Fig. 15 and Additional movie File 9). Subsequently, patient underwent regadenoson stress with myocardial perfusion single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) testing that did not demonstrate myocardial ischemia. He was discharged to home with plan to perform an outpatient CMR to better assess the LV septal abnormality.

Fig. 15.

Case 4. Fig. 2. Parasternal short axis 2D TTE view. There is a LV diverticulum of the inferoseptal wall.

Supplementary material related to this article can be found online at doi:10.1016/j.jocmr.2023.100007.

The following is the Supplementary material related to this article Movie 8, Movie 9..

Case 3 Movie 3. Cine bSSFP short axis view. There is severe LV dilation with extremely thin anterior, inferior, and lateral walls. The LV moves in synchrony with the RV but with moderate global hypokinesia.

Case 4 Movie 1. Parasternal short axis color Doppler TTE. There is color flow in and out of the LV diverticulum.

5.2. CMR findings

CMR performed at 1.5 T (Signa Excite, General Electric HealthCare, Chicago, Illinois, USA) demonstrated a pouch (21 ×31 mm) at basal to mid inferior and infero-septal segments with a narrow neck measuring 9 mm (Fig. 16, Additional Movie File 10). LGE acquisitions did not show evidence of infarction, and there was no evidence of any infiltrative or inflammatory process (Fig. 17).

Fig. 16.

Case 4. Fig. 3. Two chamber cine balanced steady state free precession (bSSFP) at end-diastole. There is a diverticulum with a narrow neck involving basal to mid inferior LV segments.

Fig. 17.

Case 4. Fig. 4. Two chamber LGE view. There is no LGE present of the myocardium surrounding the diverticulum.

Supplementary material related to this article can be found online at doi:10.1016/j.jocmr.2023.100007.

The following is the Supplementary material related to this article Movie 10..

Case 4 Movie 2. Two chamber (A), four chamber (B), and mid short axis (C) cine bSSFP. There is a LV diverticulum of the inferior basal to mid walls.

5.3. Conclusion

Initially, diagnosis of LV pseudoaneurysm was entertained and patient was referred for urgent left heart catheterization and surgical consultation. His left heart catheterization showed no obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD). He was offered surgical intervention, but declined. Subsequent, CMR at 4-month follow-up showed a stable aspect of the LV pseudoaneurysm (Additional Movie File 11).

Supplementary material related to this article can be found online at doi:10.1016/j.jocmr.2023.100007.

The following is the Supplementary material related to this article Movie 11..

Case 4 Movie 3. Four month follow-up mid short axis (A) and two chamber (B) cine bSSFP. The LV diverticulum of the basal to mid inferior wall is unchanged.

This case was discussed in multimodality imaging conference and with five different CMR experts. Given, no interval change at 4-month follow-up CMR, and absence of LGE, it was concluded that the abnormality represented congenital LV diverticulum rather than LV pseudoaneurysm. At 7-month follow-up from his initial presentation, patient continues to do well.

5.4. Perspective

LV diverticulum is a rare congenital abnormality that has been reported in 0.4% of cases at autopsy, with its first description dating back to 1816[38]. Congenital LV diverticulum has been classified into two different types [38], [39]. Muscular type, which contains mostly muscle fibers and usually arises from the LV apex and has synchronous contraction with the LV and has a narrow neck [38], [39]. This type may associate with other congenital defects such as Cantrell syndrome [38], [39]. The other type is fibrous diverticulum, which mostly consists of fibrous tissue and lacks contractile function[38], [39]. Fibrous diverticulum usually involves the inferior basal surface of the LV with a narrow neck [38], [39]. Congenital LV diverticulum may be incidentally discovered such as in our case or they may associate with other complications such as arrhythmias, systemic embolism, valvular regurgitation, and spontaneous rupture [38], [39], [40], [41], [42]. Optimal treatment for congenital LV diverticulum remains elusive with most authors choosing to observe if the patient remains asymptomatic [38], [39], [40], [41], [42].

It is imperative to make a clear distinction between LV congenital diverticulum, LV aneurysm, LV pseudoaneurysm, and LV crypts, see Table 2. LV pseudoaneurysm usually presents as a complication of MI and is defined as a contained myocardial rupture that is contained by adhering tissue, LV pseudoaneurysm depending on clinical circumstances may require a surgical intervention [38], [39], [40], [41], [42]. Pseudoaneurysm cavity has a narrow neck in sharp contrast to LV aneurysm, which contains all three layers of the LV that balloon out both in systole and diastole and has a wide neck [38], [39], [40], [41], [42]. LV aneurysm is medically managed in most cases [38], [39], [40], [41], [42]. Congenital LV diverticulum usually have a narrow neck and may be of muscular or fibrous type, but clinical presentation and LGE findings may differentiate this from LV pseudoaneurysm [38], [39], [40], [41], [42]. Finally, LV crypts are believed to be congenital in etiology and represent discrete fissures or clefts in compacted myocardium that may completely obliterate during systole[41]. Clinical significance of LV crypts remains unclear; however, they are frequently seen in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and in hypertensive heart disease[41], [42]. In summary, differentiating LV diverticulum from LV pseudoaneurysm, LV aneurysm, and LV crypts may influence clinical decision making and thus medical management.

Table 2.

Case 4. Summary of left ventricular aneurysm, pseudoaneurysm, diverticulum, and cleft.

| Location | Opening | Surrounding Wall | Contractility | Etiology and Associations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left ventricular aneurysm | Variable | Wide neck | Endocardium, myocardium, and epicardium-fibrotic walls | Akinetic or dyskinetic with ballooning of involved segments | Usually complication of coronary artery disease. Other causes may include sarcoidosis, HCM, iatrogenic, trauma, Chaga’s disease, mucopolysaccharidosis etc. |

| Left ventricular pseudo-aneurysm (Contained rupture) | Variable | Narrow neck | Pericardium | Akinetic | Usually complication of coronary artery disease, other causes may include iatrogenic, trauma, infective endocarditis etc. |

| Left ventricular fibrous diverticulum | Usually basal inferoseptal segment of the LV | Narrow neck | Fibrotic wall composed of reticulin fibers, may have some muscle fiber | Akinetic or dyskinetic | Congenital, and usually does not associate with other congenital anomalies |

| Left ventricular muscular diverticulum | Usually apical segment of the LV | Usually narrow neck but can have wide neck | Endocardium, myocardium, and epicardium | Contracts synchronously with the LV | Congenital, and may associate with midline thoraco-abdominal congenital abnormalities (Cantrell syndrome) |

| Left ventricular crypts/ clefts/ fissures/ crevices | Usually Inferior or septal wall of the LV | Usually narrow and may completely obliterate during systole | Discrete fissure or cleft in compacted myocardium lined by endocardium | Contracts synchronously with the LV | Congenital, frequently associate with HCM and hypertensive heart disease |

The CMR of Case 4 can be found here: https://www.cloudcmr.com/7957–1973-1598–0111/. The follow-up CMR can be found here: https://www.cloudcmr.com/3057–1973-3748–0142/). .

6. Case 5: COVID-19 vaccine-related myocarditis

6.1. Clinical History

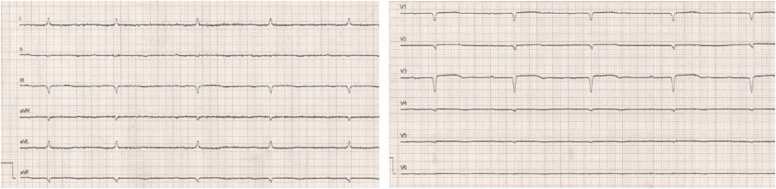

A 16-year-old male was referred for CMR 6 months after an episode of COVID-19 vaccine-related myocarditis (CVAM). He had previously been admitted to an outside hospital with mid-sternal chest pain three days after the second dose of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. There was no associated fever, shortness of breath, palpitations, or dizziness. Laboratory work-up revealed elevated inflammatory markers and troponin I level (peak = 9.78 ng/ml, normal value ≤0.08 ng/ml). The work-up was negative for other infectious, rheumatologic and toxicologic etiologies. There was no evidence of other end-organ damage. ECG showed ST segment elevations in precordial leads V4-V6 without arrhythmias.

TTE showed preserved global LV systolic function. Coronary angiography demonstrated normal coronary artery anatomy. CMR (images not available) obtained four days after the dose showed a normal LVEF, elevated native T1 and T2 values, and extensive subepicardial and midmyocardial LGE in the LV lateral wall. He was treated with IVIG. The patient was asymptomatic at discharge, with a significant decrease in troponin level to 0.24 ng/ml.

6.2. CMR findings

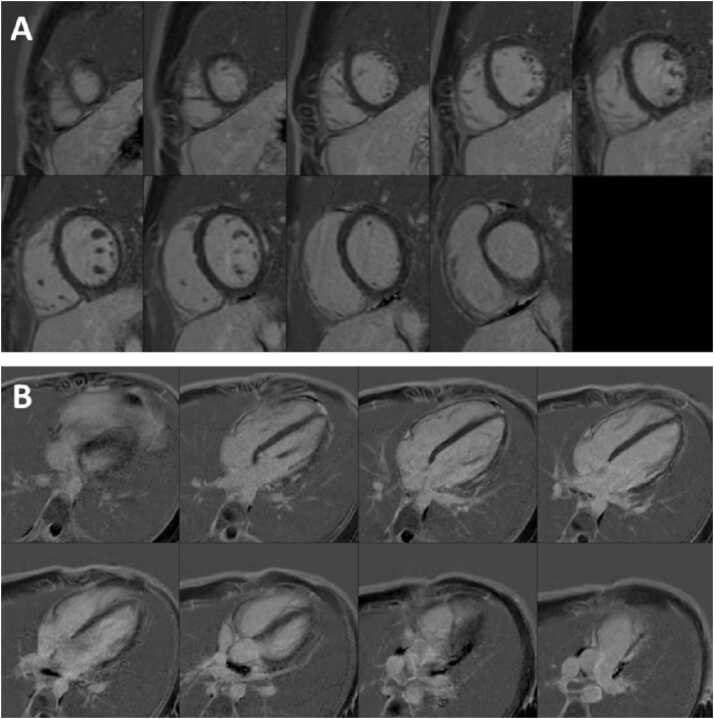

CMR obtained six months after the initial presentation showed normal LV and RV size and global systolic function (LVEF 64%, RVEF 61%), without evidence of regional wall motion abnormality (Additional Movie File 12). T2 STIR images demonstrated no evidence of focal edema (Fig. 18). Global extracellular volume (ECV) (29%; reference range 20–32%; Fig. 19) and T2 (48 ms) values were normal (Fig. 19), however focal ECV elevation was noted in the LV mid lateral wall (41%)[43]. Midmyocardial LGE was noted in the LV mid-to-basal lateral wall (Fig. 20).

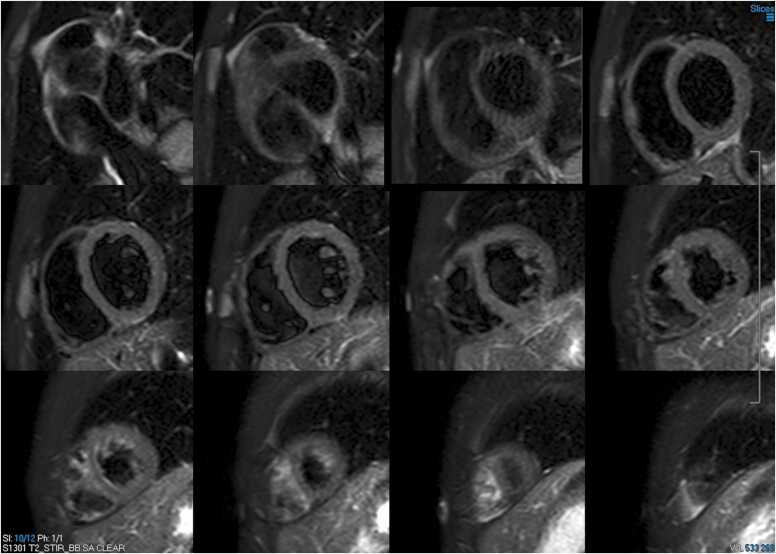

Fig. 18.

Case 5. Fig. 1. Short axis stack T2 short tau inversion recovery (STIR) images. There is no evidence of myocardial edema.

Fig. 19.

Case 5. Fig. 2. Native T1 (A), extracellular volume (ECV, B), and native T2 (C) maps mid short axis view. There is a regional increase in ECV along the LV lateral wall and normal T1 and T2 map values.

Fig. 20.

Case 5. Fig. 3. Short axis stack (A) and four chamber stack (B) LGE images. There is patchy subepicardial and midmyocardial enhancement in the mid-to basal LV lateral wall.

Supplementary material related to this article can be found online at doi:10.1016/j.jocmr.2023.100007.

The following is the Supplementary material related to this article Movie 12..

Case 5 Movie 1. Cine short axis stack bSSFP. There is normal LV and RV chamber size and global systolic function with no regional wall motion abnormalities present.

6.3. Conclusion

These findings are consistent with prior myocarditis with residual fibrosis. During the follow-up period, the patient reported occasional palpitations. However, serial Holter monitors did not reveal any arrhythmia. The long-term implications of residual fibrosis remain unknown, and the patient will require close follow-up.

6.4. Perspective

Since COVID-19 vaccines were approved for children aged 12 and older, multiple reports of CVAM have been published [44], [45], [46], [47], [48]. CVAM has predominantly affected white adolescent males. The vast majority of cases involved the messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) vaccines and presented after the second dose. The most common presenting symptom was chest pain. Most patients presented with normal LV systolic function. Two North American multicenter studies have shown that 51–88% of CMR studies in the acute phase met Lake Louise Criteria [47], [48]. Hospital course was relatively benign. Most hospitalizations lasted under a week, without the need for intensive care unit admission or inotropic support. Arrhythmias were rare. These findings differ from other forms of pediatric myocarditis, which overall have a higher rate of LV dysfunction, need for inotropic support, and arrhythmia burden [49]. The long-term prognosis of CVAM remains unknown. This case highlights the importance of close follow-up of these patients. The utility of CMR in the diagnosis of myocarditis is well established. In a pediatric population, the typical findings of myocarditis on CMR generally obviate the need for further dedicated coronary angiography. Despite having a relatively benign clinical course and normal TTE evaluations in follow-up period, this patient showed residual fibrosis six months after the onset of CVAM. The clinical significance of LGE after CVAM remains unknown. However, large outcome studies of myocarditis in adults have consistently shown adverse outcomes associated to LGE[50], [51], [52].

The CMR of Case 5 can be found here: https://www.cloudcmr.com/5557–1973-0898–0104/).

7. Case 6: Child with fulminant myopericarditis and tamponade after COVID-19

7.1. Clinical history

An 8-year-old previously healthy male with a past medical history of mild persistent asthma, unvaccinated against COVID-19, was admitted with abdominal pain, emesis, and bilateral hip and thigh pain. He was diagnosed with acute COVID-19 by initial rapid molecular testing which was subsequently confirmed by PCR testing with negative antibody testing. He had no preceding fevers. Physical examination was notable for poor peripheral perfusion. Initial inflammatory markers were normal, and an ECG demonstrated low voltages (Fig. 21). He required fluid resuscitation both in the emergency department and pediatric intensive care unit but eventually required inotropic support with epinephrine and milrinone. Chest CT showed extensive bilateral lung opacities and atelectasis, consistent with COVID-19 pneumonia (Fig. 22). Cardiac workup showed elevated troponin (peak 2.47 ng/ml; normal <0.029 ng/mL) and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) (peak 2.4 pg/ml; normal <60 pg/mL). Initial TTE showed severe LV systolic dysfunction (LVEF 31%) without LV dilation (LV end-diastolic diameter 3.57 cm, z-score −1.8) with a moderate-sized circumferential pericardial effusion (Additional Movie File 13) with a maximum dimension of 1 cm from subcostal imaging.

Fig. 21.

Case 6. Fig. 1. Twelve lead electrocardiogram (ECG) on admission. There is sinus tachycardia with diffuse low voltages present.

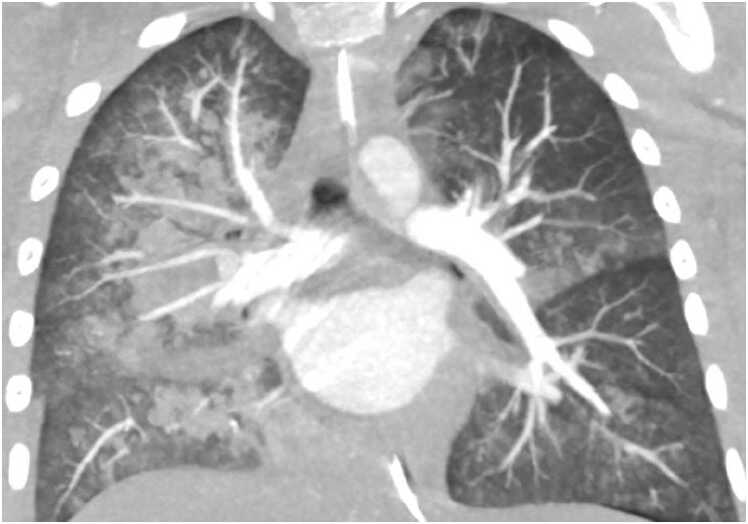

Fig. 22.

Case 6. Fig. 2. Coronal chest CTA. There are extensive bilateral lung opacities and atelectasis present.

Supplementary material related to this article can be found online at doi:10.1016/j.jocmr.2023.100007.

The following is the Supplementary material related to this article Movie 13..

Case 6 Movie 1. Parasternal short axis TTE view. There is severe LV systolic dysfunction and moderate pericardial effusion present.

The patient was treated with IVIG, remdesivir, and methylprednisolone. Due to increased air hunger, emesis, and aspiration, he suffered an in-hospital cardiac arrest requiring chest compressions with return of spontaneous circulation. For tenuous hemodynamics and persistent hypoxia, he was ultimately placed on venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) support on hospital day 5 with concomitant percutaneous pericardiocentesis. He was decannulated on hospital day 8 without incident, transferred to the ward on hospital day 11, and discharged home in stable condition on hospital day 16. His troponin and BNP levels peaked while on ECMO support, then trended down and normalized prior to discharge. CMR was performed within 2 weeks of discharge, but 7 weeks from onset of symptoms.

7.2. CMR findings

CMR was performed at 3 T (Magnetom Skyra, Siemens Healthineers AG, Erlangen, Germany) without sedation to evaluate cardiac function and for tissue characterization. There was normal bi-ventricular size and systolic function (LVEDVI 72 mL/m2, LVEF of 61%, RVEDVI 81 mL/m2) without significant residual pericardial effusion (Additional Movie File 14). T2w imaging showed increased signal intensity in the mid-LV inferior wall, extensive pericardial LGE, and elevated ECV (Fig. 23, Fig. 24, Fig. 25). Findings were consistent with myopericarditis.

Fig. 23.

Case 6. Fig. 3. T2w triple inversion recovery short axis mid slice. There is increased signal intensity in the inferior LV wall.

Fig. 24.

Case 6. Fig. 4. Short axis (A) and four chamber (B) LGE images. There is enhancement of the pericardium (arrows) consistent with pericarditis.

Fig. 25.

Case 6. Fig. 5. Native T1 (A), ECV (B), and native T2 (C) mid short axis slices. Normal global native T1 value of 1210 msec (institutional normal < 1270 msec), increased global ECV of 33% (institutional normal < 29%) with patchy areas of further hyperintensity at the mid-inferoseptal (33.9%) and lateral wall (34.8%, arrows). The increased ECV values in the clinical context was interpreted to represent residual myocardial inflammation and edema. The global T2 value was normal at 33 msec and this slice was not the same slice on T2 short tau inversion recovery (STIR).

Supplementary material related to this article can be found online at doi:10.1016/j.jocmr.2023.100007.

The following is the Supplementary material related to this article Movie 14..

Case 6 Movie 2. Two chamber (A) and four chamber (B) cine bSSFP views. There is normal bi-ventricular size and systolic function with mild mitral regurgitation and no significant residual pericardial effusion.

7.3. Conclusion

Clinical course was consistent with COVID-19 pneumonia with fulminant myopericarditis. CMR findings were consistent with pericarditis with evidence of residual myocardial inflammation/edema, but otherwise recovered cardiac function. Positive prognostic indicators were the paucity of LGE and normal strain values in the setting of normal LVEF. This case highlights the tumultuous course and cardiac involvement that can be seen, even in pediatric patients with severe COVID-19 illness, the recovery of cardiac function that can be seen during the convalescent phase of illness, and the spectrum of CMR findings in pediatric patients including pericardial involvement and myocardial inflammation/edema.

7.4. Perspective

One of the key findings is that acute COVID-19 can result in critical illness, even in children. Our 8-year-old patient unfortunately had fulminant myopericarditis with COVID-19, without evidence of MIS-C. CMR has two important roles in the management of this patient. First, results of parametric mapping, LGE imaging, and strain imaging have all been shown to be strong prognostic indicators in myocarditis [53]. Second, there is a clear association between mRNA vaccination against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and the rare complication of myocarditis/pericarditis, particularly in young males [54]. Current United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations state that mRNA vaccination should be deferred until the episode of myocarditis or pericarditis has completely resolved [55]. Given the excellent tissue characterization offered by CMR, even in young children, a follow-up CMR to ensure resolution of active myocardial and pericardial inflammation, particularly in this case with significant myocardial and pericardial abnormalities, may be prudent prior to vaccination.

Our patient met the diagnostic criteria for fulminant myocarditis based on the history of acute illness (presentation with COVID-19 pneumonia, negative SARS-CoV-2 antibodies) and cardiogenic shock requiring inotropic support [56]. While long-term outcome after survival from fulminant myocarditis is favorable in adults, these findings may not be applicable to pediatric patients [57]. After recovery and discharge from the hospital, the patient's CMR demonstrated normalization of biventricular function (Additional Movie File 14) and no myocardial LGE (Fig. 24). However, he was noted to have residual myocardial edema (Fig. 23) and ECV elevation (Fig. 25) 7 weeks from the onset of his symptoms. This may represent lingering subacute myocarditis, with the ECV elevation representing myocardial hyperemia/inflammation, especially in the setting of the persistent T2-STIR abnormality. Residual T1 and T2 abnormalities have been reported past 8 weeks in some patients [58]. However, continued elevation on follow-up may represent chronic indolent myocarditis, or possibly development of diffuse interstitial fibrosis, which is associated with worse outcomes over time[59]. Persistent myocardial abnormalities after acute COVID-19 infection have also been shown in several studies, and the true mechanism of myocardial injury after COVID-19 remains unknown [60], [61]. Fortunately, his myocardial deformation by strain encoded (SENC) imaging appears normal, with recent studies showing the additive value of strain assessment to predict prognosis, particularly in those with normal LVEF [62]. Both LV global longitudinal (GLS) (-18.3%; normal < −17%) and global circumferential (GCS) (-19%; normal < −18%) strain were normal [63].

The finding of pericardial LGE (Fig. 24) is an interesting finding given the association between mRNA COVID-19 vaccines and the development of myopericarditis. Although his biventricular function, cardiac biomarkers, and clinical symptoms have improved, he continued to demonstrate abnormalities on CMR, demonstrating its exceptional capabilities in myocardial tissue characterization. We plan to repeat CMR at 6 months to re-evaluate his myocardium and pericardium prior to clearing him to receive COVID-19 vaccinations. The family has continued to express support for vaccinating our patient, in part due to his severe illness.

The CMR of Case 6 can be found here: https://www.cloudcmr.com/8957–1973-4618–0189/). .

8. Case 7: RVOT thrombosis without valvular extension in a repaired tetralogy of Fallot patient

8.1. Clinical history

A 46-year-old female with a history of asthma and tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) was evaluated for progressive dyspnea, chest pain, and palpitations. She underwent transannular patch repair at age 8. Ten years prior to presentation, due to severe pulmonic regurgitation, RV dilation (RVEDVI 180 mL/m2; normal 57–95 ml/m2), and declining RV systolic function (RVEF 37%; normal 53–77%), she underwent bioprosthetic pulmonary valve replacement (PVR; 29 mm Mosaic bioprosthetic valve, (Medtronic, Dublin, Ireland)), aneurysmectomy, and RVOT revision with placement of a GORE-TEX patch (W.L. Gore & Associates, Newark, Delaware, USA) to enlarge the RVOT diameter.

On current presentation, the cardiovascular exam revealed a single S1, widely split S2 varying with respiration due to right bundle branch block (RBBB), 1/6 systolic ejection murmur and early-mid diastolic murmur best heard at the left sternal border. Holter monitor identified sinus rhythm with frequent premature atrial contractions, occasional ectopic atrial rhythm, occasional premature ventricular contractions, and one 10-beat run of asymptomatic ventricular tachycardia. TTE compared to prior TTE showed a 5–10% decline in LVEF due to global mild hypokinesis, mild-moderate aortic valve regurgitation, and mildly low RVEF due to akinesis of the RVOT. Furosemide was started, yielding resolution of paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea but dyspnea upon walking 25–50 meters on flat ground persisted. She was referred for right and left heart catheterization, which demonstrated mildly elevated right heart filling pressures (RV pressure 75/20 mmHg; RA mean 12 mmHg), moderate pulmonary arterial hypertension (59/33 mmHg, mean 41 mmHg), and severely elevated left-sided pressures (LV end diastolic pressure 41 mmHg) with systemic hypertension (aortic pressure 161/85 mmHg). Selective coronary angiography revealed no obstructive CAD. Intravenous diuretics and afterload reduction were initiated. CMR was obtained for a definitive assessment of biventricular volumes, function, and tissue characterization.

8.2. CMR findings

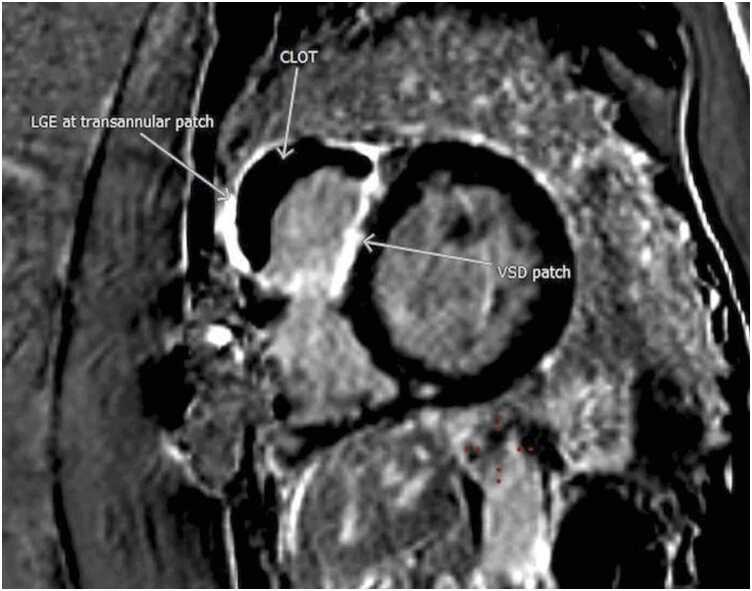

CMR at 1.5 T (Avanto, Siemens Healthineers AG, Erlangen, Germany) revealed a mildly dilated LV (LVEDVI 115 mL/m2; normal 58–94 ml/m2) with moderately depressed systolic function due to global hypokinesis (LVEF 35%, Fig. 26). The RV was mildly dilated (RVEDVI 108 mL/m2 (normal 57–95 ml/m2)) with severely depressed systolic function due to global hypokinesis and infundibular akinesis (RVEF 25%, Fig. 26). There was moderate-severe aortic regurgitation (22 mL, 40% regurgitant fraction, holodiastolic flow reversal in the descending thoracic aorta), moderate tricuspid regurgitation (30% regurgitant fraction), and well-seated 29 mm Mosaic bioprosthetic PVR with mild stenosis (peak velocity estimated 2.8 m/s) without significant regurgitation. A 15 × 53 mm, sessile, laminated thrombus without a mobile component was identified along the akinetic RVOT at the site of the GORE-TEX RVOT patch (Fig. 27, Fig. 28, Fig. 29).

Fig. 26.

Case 7. Fig. 1. Mid short axis (A), two chamber (B), basal short axis (C), and four chamber (D) cine bSSFP at end-diastole. There is a 15 × 53 mm mass in the RV outflow tract. The LV and RV are mildly dilated.

Fig. 27.

Case 7. Fig. 2. Mid short axis cine bSSFP (A), phase sensitive inversion recovery (PSIR) with inversion time (TI) 600 msec (B), and PSIR with null TI (C), and ECV map (D). The RV outflow tract thrombus (arrows) is well seen.

Fig. 28.

Case 7. Fig. 3. Short axis stack PSIR LGE imaging with dark blood technique. There is significant basal-mid RV outflow tract (RVOT), anterosuperior free wall, and RV endocardial anteroseptal at the ventricular septal defect (VSD) patch site hyperenhancement with a large, laminated RVOT thrombus (yellow arrows). There is a punctate apical inferolateral transmural hyperenhancement from prior LV vent site (blue arrows).

Fig. 29.

Case 7. Fig. 4. Basal short axis PSIR LGE image. The RVOT thrombus is interposed between transannular patch and VSD patch. Dense hyperenhancement is seen at the anterior right ventricular free wall, infundibulum, and endocardial septum.

8.3. Conclusion

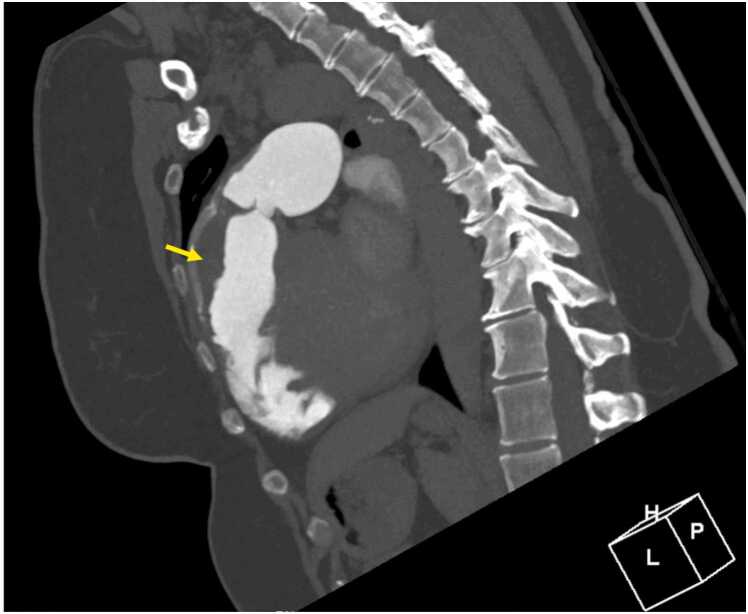

Prior to initiating therapeutic anticoagulation for the thrombus identified on CMR, chest CTA was performed and confirmed a laminated thrombus in the RVOT without peripheral embolic changes in either lung and without pseudoaneurysm, perforation, or RVOT disruption (Fig. 30 Case 7 Fig. 5). A direct oral anticoagulant and guideline-directed medical therapy for a nonischemic cardiomyopathy were initiated with apixaban and sacubitril/valsartan.

Fig. 30.

Case 7. Fig. 5. Off axis sagittal computed tomography angiogram. There is a thrombus (arrows) in the RVOT.

Three months later, the patient reported improved dyspnea on exertion with no limitation while walking on flat ground. At 16 month follow-up, the patient reported resolution of all symptoms. CMR revealed mild LV dilatation (LVEDVI 111 ml/m2), normal LV systolic function (LVEF 55%), normal RV size (RVEDVI 90 ml/m2), low normal RV systolic function (RVEF 44%), mild-moderate aortic regurgitation (regurgitant fraction 16%), bioprosthetic PVR with ongoing mild pulmonic stenosis and no significant pulmonic regurgitation, and resolving, non-mobile, mural laminar thrombus along the RVOT patch measuring 7×40 mm (Fig. 31).

Fig. 31.

Case 7. Fig. 6. Mid short axis cine bSSFP follow-up. There is a 7 × 40 mm thrombus (arrow) along the RVOT patch.

8.4. Perspective

Isolated, in situ RVOT thrombosis has not previously been reported after RVOT patching in TOF, except in the setting of a large RVOT aneurysm[64]. The formation of RVOT thrombus in this case likely arose from multiple factors including flow distortions, prosthetic material/abnormal endothelium, and akinesia of the RV free wall. Gore-Tex cardiac patch is a prosthetic material composed of polytetrafluoroethylene that is used as a conduit in various congenital heart disease repairs, including transannular patch for TOF repair. Thrombosis associated with Gore-Tex material, although rare, has been reported previously involving a Blalock-Thomas-Taussig (BTT) shunt, a central shunt, and Fontan palliation [65], [66], [67].

CMR has been used to investigate flow dynamics in repaired TOF, and 4D flow studies have shown a variety of altered flow hemodynamics among these patients [68]. During RV systole, increased vortices can be observed in the RVOT because of pulmonary insufficiency countering antegrade systolic flow [69]. The interaction of the antegrade systolic jet with the pulmonary regurgitant jet may create variable intracardiac topology that forms shear layers and more turbulent-like flow [70]. Abnormal RV direct flow, a measure of blood entering and exiting the ventricle within the analyzed cycle and the main determinant of RV intracavity blood flow kinetic energy, has been shown to be lower in patients with repaired TOF in comparison to controls [71]. Thus, altered flow dynamics secondary to the nature of TOF disease along with RV dysfunction as evidenced by akinesia of the free ventricular wall were likely compounded by the presence of prosthetic material, leading to a milieu predisposing to thrombus formation.

With initiation of anticoagulation and guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) for non-ischemic cardiomyopathy, there has been sustained, marked improvement in biventricular function. Although counterintuitive at first take, LV systolic dysfunction is more common among adult CHD patients with biventricular repair and right-sided disease (like TOF) than those with left-sided disease (i.e. subaortic stenosis, coarctation of the aorta; 15% vs. 10%, p > 0.001) [72]. While prior studies have been equivocal about the association of GDMT with improved ventricular systolic function, Egbe et al. found that GDMT improved LVEF and lowered the risk of cardiovascular events among patients with right-sided lesions (including those with TOF) [72]. Mechanistically, LV recovery may be related to reductions in afterload to both pulmonary and systemic vascular systems (with normotension also helping reduce the degree of aortic regurgitation), improved ventriculo-ventricular interactions, such as improved LV twist, as well as decongestion given this patient’s presentation with hypervolemia and severely elevated left-sided filling pressures. Ventricular interdependence has previously been well-described with RV dysfunction and dilation adversely affecting LV function and geometry, and RV dysfunction secondary to the underlying substrate of repaired TOF with akinesia compounded by thrombus in the RVOT likely worsened biventricular dynamics [73]. Direct oral anticoagulant use likely aided in resolution of the RV thrombus based on a reduction in size seen on follow-up CMR. Impaired LV twist, not uncommon in TOF patients, is suggested by apical LGE in this patient, and it may also factor into LV dysfunction. CMR was therefore helpful in not only identifying the RVOT thrombus, but also quantifying ventricular performance and guiding medical therapy.

In repaired TOF patients, CMR is integral to follow-up imaging for characterization of volumetrics, function, tissue characterization, and flow dynamics while also having utility for evaluating other pathology such as tricuspid regurgitation and aortic regurgitation. CMR further aids in mortality risk prediction and can identify rare complications, such as the RVOT thrombus seen in this case[74].

The CMR of Case 7 can be found here: https://www.cloudcmr.com/7157–1973-2568–0187/).

9. Case 8: LGE in neonate

9.1. Clinical history

A near term newborn with maternal history of chorioamnionitis was admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit for respiratory distress after birth. He was managed as per the unit protocol for neonatal sepsis. He was soon noted to have persistent atrial tachycardia requiring rate control with medical therapy, after attempts at cardioversion with vagal maneuvers, adenosine and synchronized cardioversion failed. Initial TTE revealed normal cardiac anatomy with normal myocardial contractile function. He subsequently developed myocardial dysfunction and low cardiac output state requiring inotropic support. There was mild troponin leak (800 pg/ml, normal <45 pg/ml) and detection of enterovirus in blood by PCR raising suspicion of neonatal myocarditis.

A CMR (1.5 T, Ingenia, Philips Healthcare, Best, Netherlands) at 2 weeks of age revealed depressed LV contractile function (LVEF 41%) with no LGE (Fig. 32). The patient clinically improved with supportive therapy. Follow up serial TTE revealed improving LV systolic function with new findings of patchy subendocardial focal areas of brightness in the basal- and mid-septal walls. A repeat CMR was requested at 4 weeks of age.

Fig. 32.

Case 8. Fig. 1. Basal short axis LGE image. No hyperenhancement at the 2 week scan.

9.2. CMR findings

The repeat CMR using neonatal protocol was performed at 1.5 T (Ingenia, Philips Healthcare, Best, Netherlands) avoiding sedation using the ‘feed and swaddle’ method [75]. CMR revealed normal LV dimensions (LVEDVI 44 ml/m2, normal 36–53 ml/m2) with normal LV mass (LV mass indexed 41 g/m2, normal 27–42 g/m2) and systolic function (LVEF 71%; >54%). There was focal diminished systolic thickening of the basal anteroseptal and basal inferoseptal LV segments (AHA segments 2,3) (Additional Movie File 16).

Supplementary material related to this article can be found online at doi:10.1016/j.jocmr.2023.100007.

The following is the Supplementary material related to this article Movie 15, Movie 16..

Case 6 Movie 3. Four chamber strain encoded imaging measuring circumferential strain. The patient’s LV global longitudinal (GLS) and global circumferential strain (GCS) were both normal at −18.3% and −19%, respectively (institutional control data with normal values of LV GLS < −17% and LV GCS < −18%).

Case 8 Movie 1. Short-axis bSSFP cine from base to apex. Normal LV and RV size and global systolic function present. There was diminished systolic thickening of the basal septal segments.

LGE imaging was performed immediately after administration of gadolinium contrast [0.62 mmol (0.2 mmol/kg); Gadavist® (Bayer HealthCare, Berlin, Germany)] to account for the rapid washout of contrast in the setting of high neonatal heart rates. A respiratory motion-compensated free-breathing gradient echo T1w phase sensitive inversion recovery (PSIR) sequence was used. Inversion time was selected from a modified Look-Locker inversion recovery sequence (MOLLI) based on the inversion time where myocardium was best nulled. Thin (6 mm) myocardial slices in the short axis were acquired through the ventricles with a field-of-view of 200 mm and in plane spatial resolution of 1.6×1.9 mm.

Acceleration techniques included a sensitivity encoding (SENSE) factor of 1.8 and signal averaging of 2. Mid diastolic imaging with shortened read-out window (50ms) was obtained at every 4th R-R interval to account for the fast heart rate. This revealed sub-endocardial partial thickness LGE of the AHA segments 2 and 3 (Fig. 33). These findings were consistent with neonatal thromboembolic MI.

Fig. 33.

Case 8. Fig. 2. Magnitude and PSIR four chamber (A) and basal short axis (B) images. Sub-endocardial partial thickness LGE of the basal septal myocardium.

9.3. Conclusion

Neonatal MI in the infant is suspected to be the result of a perinatal thromboembolic event. Paradoxical embolism through the foramen ovale or the ductus arteriosus can occur in the fetus in association with umbilical cord hematoma, umbilical venous catheterization, prenatal renal vein thrombosis and many times, without obvious sources [76].

The patient continued to improve clinically with supportive therapy and was discharged at 4 weeks of age. Since then, he has been asymptomatic, showing normal growth and development, no arrythmias and normal cardiac function. He was continued on betablocker therapy for arrythmia control with no significant side effects.

9.4. Perspective

LGE CMR imaging sequence is increasingly used in the evaluation of pediatric cardiovascular disorders. It is seen as a result of extracellular space expansion, either from acute cell damage or chronic scarring or fibrosis. LGE imaging in neonates and young infants is challenging but feasible.

The challenge of imaging in the setting of high neonatal heart rates is overcome using acceleration techniques and adjusting the acquisition window (views per segment) to the heart rate [77], [78]. To account for the small heart size in neonates using a smaller field-of-view (200 mm) and thinner slices (5–6 mm) gives an adequate spatial resolution. These measures, however, decrease the voxel size resulting in a low signal-to-noise ratio. This is improved by using the smallest available coil (eg. a smaller pediatric multi-element cardiac phased-array coil) and signal averaging. Motion compensation is used to account for the respiratory motion.

Typically, 180-degree inversions are placed every two R-R intervals for LGE sequences to allow for recovery of the longitudinal signal between successive inversion pulses. However, this is not feasible at high heart rates and triggering is altered to every 4th R-R interval in neonates. This may require manually halving the heart rate to ‘trick’ the scanner into increasing the acquisition window. Lastly, neonates have a higher rate of wash out of the gadolinium contrast agent from the myocardium, necessitating minimal delay in obtaining the LGE images after contrast administration.

The CMR of Case 8 can be found here: https://www.cloudcmr.com/4857–1973-2758–0156/).

10. Case 9: Concomitant dual genetic cardiomyopathies in a patient complicated by stroke

10.1. Clinical history

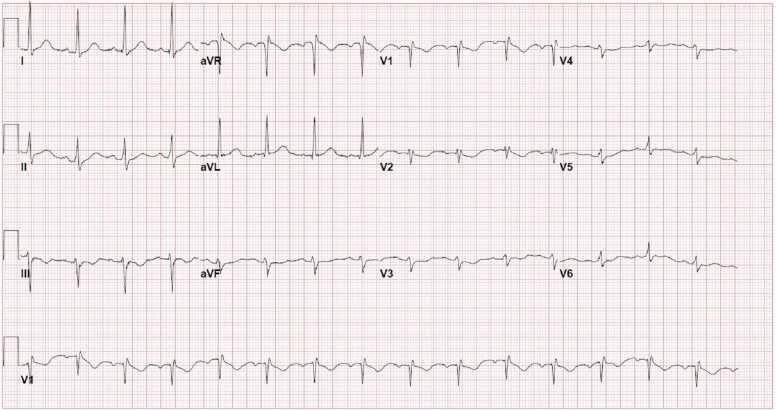

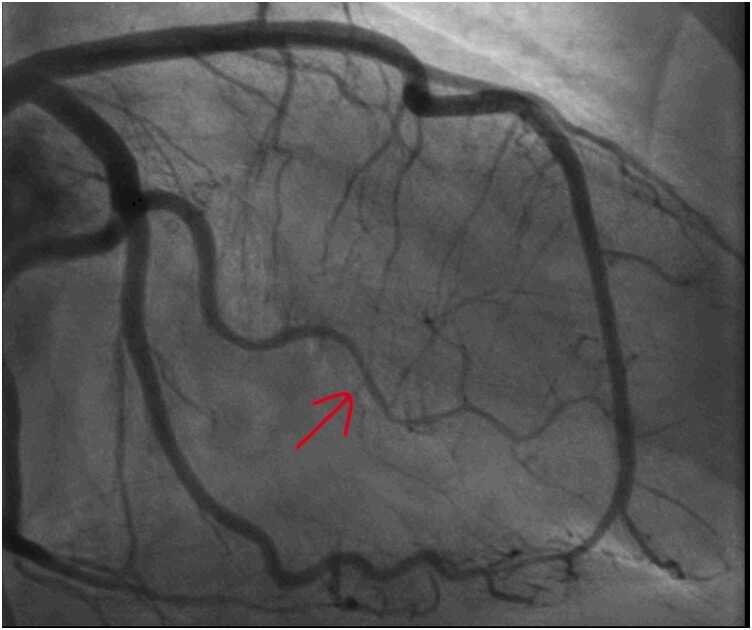

A 60 year-old female was referred to our cardiology clinic to investigate asymptomatic ECG abnormalities detected during workup for elective hemicolectomy for malignancy. Her medical history included rheumatoid arthritis, obstructive sleep apnea, osteoarthritis and obesity. Her younger half-brother died in his 50′s from sudden cardiac death whilst playing sports. Medications included metoprolol and warfarin. Physical examination was unremarkable. Her ECG demonstrated rightward-axis deviation, RBBB, T-wave inversion in leads V1 to V4 and small positive deflections at the end of the ECG in leads V3 to V5 (Fig. 34). Her TTE demonstrated severe asymmetrical LV wall thickening (provide wall thickness data), akinesis of all apical segments, and a mass in LV apex (Additional Movie File 17). Coronary angiography showed no significant CAD (Fig. 35). She was referred for CMR to further investigate her cardiomyopathy and suspected LV apical thrombus.

Fig. 34.

Case 9. Fig. 1. Twelve lead ECG. There is rightward axis with right bundle branch block and epsilon waves in leads V3 to V5 (arrows).

Fig. 35.

Case 9. Fig. 2. Anteroposterior (A) and lateral (B) projections during invasive coronary angiography. There is normal left sided and right coronary artery anatomy.

Supplementary material related to this article can be found online at doi:10.1016/j.jocmr.2023.100007.

The following is the Supplementary material related to this article Movie 17..

Case 9 Movie 1. Four chamber TTE without (A) and with (B) contrast enhancement. There is asymmetric severe LV wall hypertrophy, akinesia of apical segment, and a small hypointense mass in the apex.

10.2. CMR findings

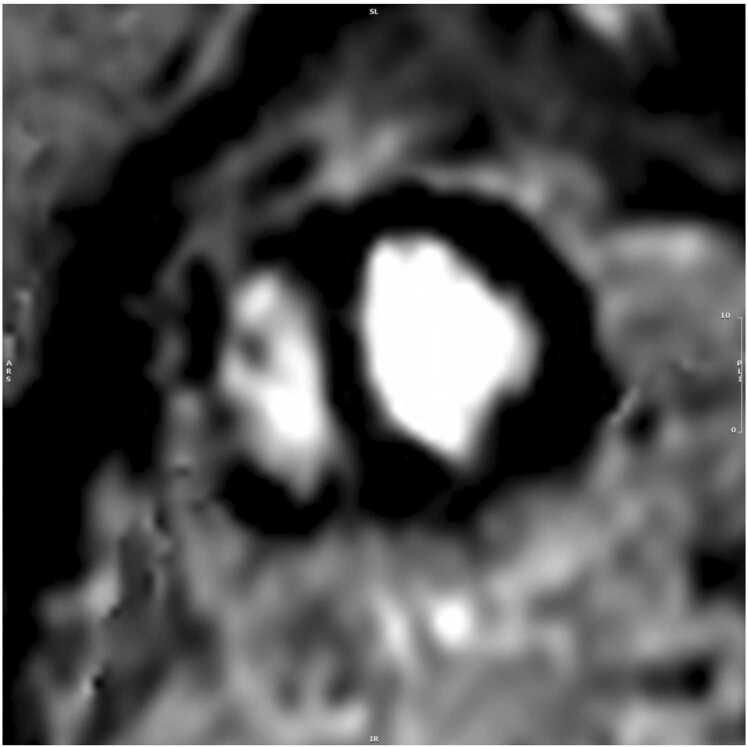

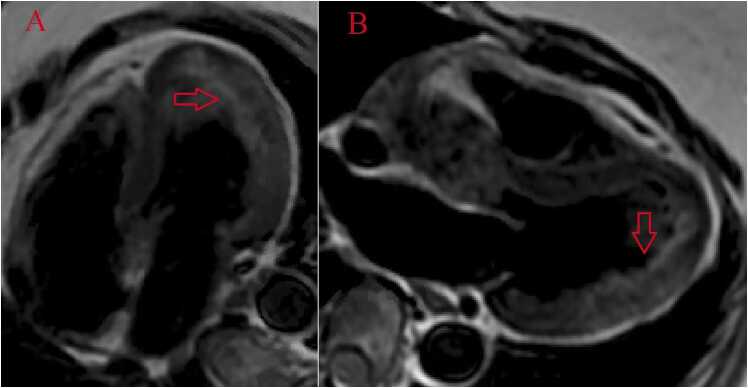

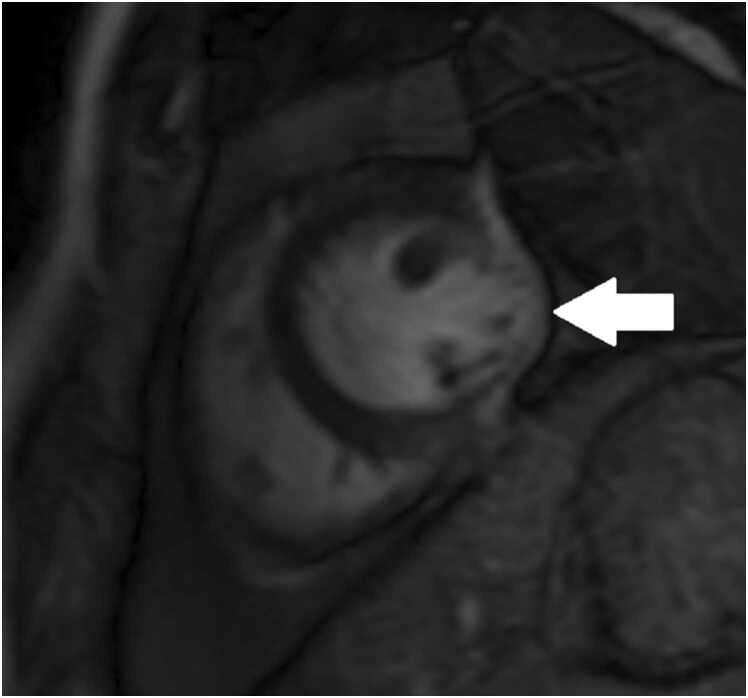

The CMR study was performed on 1.5 T (Magnetom Vida, Siemens Healthineers AG, Erlangen, Germany) with sinus rhythm of 72 bpm. Cine imaging demonstrated normal LV size (LVEDVI 78 ml/m2, normal 51–84 ml/m2) and normal LVEF of 55% (normal 53–77%) (Additional Movie File 18). Aneurysmal dilatation of LV apical segments was present with a 17×13 mm thrombus (Additional Movie File 19). There was no evidence of non-compaction. Increased LV wall thickness was seen in the basal-to-mid septal segments with maximal thickness of 21 mm (Additional Movie File 19). Papillary muscles demonstrated normal structure and attachment. Systolic anterior motion of mitral leaflets was present. The RV was dilated (RVEDV 240 mL) and RVEF was depressed at 27% (Additional Movie File 19). “Accordion” sign was present in the subtricuspid RV free wall and associated with dyskinesis and microaneurysmal changes (Additional Movie File 19). The “accordion sign” has been described in the literature as focal crinkling of the RV free wall, typically in the sub-tricuspid or the RVOT region, that is caused by multiple sequential outpouching that do not reach microaneurysmal size[79]. Parametric mapping was not available. LGE imaging demonstrated patchy mid-wall scar in the hypertrophied LV segments but no obvious confluent scar was seen in LV apex (Fig. 36). Myocardial scar comprised 14% of total LV myocardium. There was subtle LGE in the sub-tricuspid region of the RV free wall (Fig. 36).

Fig. 36.

Case 9. Fig. 3. Two chamber (A) and four chamber (B) (LGE images. There is patchy mid myocardial LGE in the LV inferior wall often seen in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. There is LV apical aneurysm without confluent myocardial scarring and presence of a thrombus confirmed by avascularity of the mass. There is subtle LGE in the sub-tricuspid region of the RV free wall often seen in arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (B).

Supplementary material related to this article can be found online at doi:10.1016/j.jocmr.2023.100007.

The following is the Supplementary material related to this article Movie 18, Movie 19..

Case 9 Movie 2. Cine bSSFP short axis stack. There is asymmetrically increased LV wall thickness (maximum diameter 21 mm) of basal to mid septal and anterior segments with LV apical aneurysm and probable thrombus. Small pericardial effusion is present.

Case 9 Movie 3. Cine bSSFP two chamber (A), three chamber (B), four chamber (C), and RV outflow tract (D) views. There is severe asymmetrical increased LV wall thickness (A-C) and systolic anterior motion of the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve with dynamic outflow tract obstruction (B). Mass seen in the LV apex likely representing a thrombus (A). Dyskinetic systolic bulging of a microaneurysm can be seen in the RV outflow tract free wall (B,D) and dyskinetic aneurysm in RV inferior wall (D). The RV is dilated with “accordion sign” in the sub-tricuspid “triangle of dysplasia” (C). Note that small outpouching of apical RV free wall is due to tethering by moderator band and is a normal variant that may be mistaken for regional wall motion abnormality (C).

10.3. Conclusion

Genetic analysis revealed a pathogenetic mutation in the Plakophillin 2 (PKP2) gene and a strong class 3 A variant of uncertain significance (VUS) in the formin homology 2 domain containing 3 (FHOD3) gene, which is a gene associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)[80]. Final diagnosis was concomitant genetic cardiomyopathies of arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy and HCM due to digenic inheritance complicated by large LV apical aneurysm and thrombus.

10.4. Perspective

Based on CMR findings, patient underwent further investigations. Electrophysiology review of ECGs confirmed presence of epsilon waves (Fig. 34, arrows). Warfarin had been stopped one month prior to her CMR based on contrast-enhanced TTE report that suggested absence of thrombus. Warfarin was subsequently restarted 3 weeks after her CMR study; however, one week after that she suffered a stroke with large frontoparietal and basal ganglia infarction demonstrated on brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Her international normalized ratio (INR) was subtherapeutic (INR 1.3) at time of stroke. She underwent prolonged rehabilitation course with excellent recovery. Family members were offered genetic counselling and cardiac screening every 3–5 years from childhood was recommended. Holter monitor showed sinus rhythm throughout with 0.5% burden of ventricular ectopics. From the arrhythmia specialist perspective, due to the patient being reluctant to consider an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) for primary prevention, the decision for a loop recorder with close rhythm monitoring was made with the option to upgrade to ICD implantation if further high-risk features were identified.

Arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy diagnosis is supported by ECG, imaging and genetic findings and meets 2010 Revised Taskforce Criteria for diagnosis of arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy [81]. Although it may be tempting to attribute both cardiomyopathic phenotypes to a single pathogenic gene variant, PKP2 pathogenic variants to date have not been associated with HCM phenotypes[82]. It is possible that cycles of temporarily ceasing and restarting anticoagulation based on alternating imaging modalities with differing sensitivities for thrombus may have contributed to thrombus instability and consequent stroke.

This case demonstrates coexistence of two separate cardiomyopathic phenotypes that is likely attributable to digenic inheritance and the presence of pathogenic variants in two different cardiomyopathy genes. Very little published literature is available regarding prevalence of co-existing cardiomyopathies.

If pathologic variants are inherited independently and assuming genetic cardiomyopathy prevalence of 0.2%, then it might be expected that 1 in 2500 individuals could have ≥ 2 pathogenic cardiac mutations. Features supporting a causal role of VUS in FHOD3 gene for HCM phenotype in this case include rarity of variant, in silico computational simulation predicts pathogenicity and comparable variant of uncertain significance examples display moderate pathogenicity. Further research in this clinical is needed. TTE imaging correctly identified presence of HCM but likely did not detect presence of persisting left thrombus presence and missed diagnostic imaging criteria for arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy.

This case also highlights the central role of CMR in investigation and diagnosis of RV pathology. Indeed, it was only in the context of CMR findings that several relevant pre-existing features such as epsilon waves on ECG were finally recognized. Prior studies have shown TTE can only identify 50% of arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy cases that are identified by CMR, which suggests that selective use of CMR may double number of identified cases of this potentially life-threatening disease [83], [84]. This case supports the concept that lowering testing threshold and improving access to advanced cardiac imaging can improve patient outcomes.