Post-traumatic stress disorder has attracted controversy and scepticism since its first appearance in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders in the 1980s.1 Over the years the diagnostic criteria have been refined and revised, but the causal relation between the diagnosis and an external trauma has remained fundamentally unchanged. Post-traumatic stress disorder is associated with clinically important distress that transcends ordinary misery and unhappiness as well as with disruption and impairment of daily functioning. We argue that the diagnosis is valid and important for both patients and doctors.

Summary points

Post-traumatic stress disorder is a valid and useful diagnosis but is not the only psychiatric response to trauma

Prevalence in the general population is estimated between 1% and 7.8%

The disorder is associated with high rates of psychiatric comorbidity and impairment in social and occupational functioning

Post-traumatic stress disorder can be differentiated from other psychiatric diagnoses by biochemical, neuroanatomical, and phenomenological characteristics

Concerns about the diagnosis in victims of chronic and lifelong trauma could be resolved by further refinement of the diagnostic criteria

Social or psychiatric diagnosis?

One of the main criticisms of the diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder is that it has been constructed out of sociopolitical ideas rather than psychiatric ones.2 However, most psychiatric conditions reflect changes in human thinking over time.3 For example, changes in the political climate and fashion were more influential than advances in medical research in altering the categorisation of homosexuality as a disease. Social factors such as poverty also contribute to mental illness, stress, suicide, family integration, and substance misuse.4 Sociocultural factors may determine whether the person is able to cope with the potentially traumatising experiences that set the stage for the development of post-traumatic stress disorder.5

What does diagnosis achieve?

The diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder was developed partly as an attempt to normalise the psychological, cognitive, and behavioural symptoms observed in many traumatised people. It redefined the symptoms of the disorder as a normal response to an abnormal event rather than a pathological condition. The diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder helped to deflect blame away from the sufferer and diminish his or her sense of guilt, shame, and failure. Nevertheless, the disorder is associated with low rates of referral for treatment and high rates of early drop out from treatment.6

The main purposes of a diagnostic classification are to facilitate communication between clinicians and researchers, promote research activity, encourage the development of specific treatments, provide information about prognosis, and allow services to be developed.7 The diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder meets these requirements. This contrasts with the diagnosis of personality disorder; not only is this a socially constructed condition, but the classification offers little guidance for treatment or diagnostic validity, and the diagnosis is, by definition, highly stigmatising.8

Validity of diagnosis

The fact that the diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder has been internationally recognised is an indication of its usefulness and perceived validity. However, awareness is increasing that the diagnosis has more validity for some groups of trauma survivors than others. People who have suffered repeated chronic trauma, including victims of torture, intrafamilial violence, or childhood abuse, tend to present with a more chronic and complex clinical picture.9 This is more closely embodied by the ICD-10 (international classification of diseases, 10th revision) diagnosis, “enduring personality change after catastrophic experience.”10 Post-traumatic stress disorder is now known to be only one of several possible psychiatric responses to trauma, and it should not be allowed to trump other equally serious and disabling mental disorders that may arise.11

Causes and effects of post-traumatic stress disorder

Although an external traumatic event is the central aetiological factor in the development of post-traumatic stress disorder, pre-existing vulnerability factors are important, particularly after less severe trauma.12 This is also true for psychiatric illnesses such as schizophrenia and depression, in which vulnerability factors may predispose the individual to develop the illness but do not influence the phenomenology and are not incorporated into the diagnostic criteria.

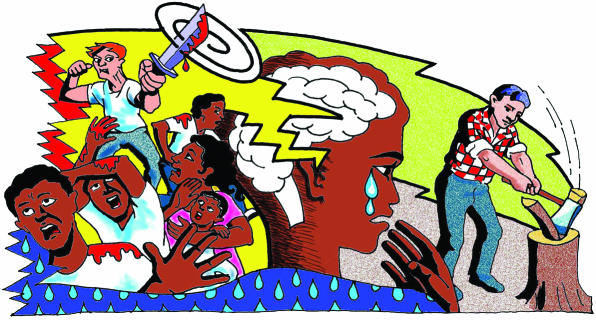

SUE SHARPLES

Epidemiological studies in the United States have found rates of post-traumatic stress disorder between 1% and 7.8%.13,14 There has been no study on the epidemiology of trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder in the United Kingdom, but comparative data from other developed countries suggest the rates of post-traumatic stress disorder are similar to those in the United States.15 People who have post-traumatic stress disorder are at increased risk of developing other psychiatric disorders14 and are at significantly increased risk of committing suicide.16 The effect of post-traumatic stress disorder on employment and work productivity is similar to that associated with depression and translates into an annual loss of productivity above $3bn (£2.1bn) in the United States.16 The national comorbidity survey identified increased odds of school and college failure, teenage pregnancy, marital instability, and current unemployment associated with a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder.14 Thus, the socioeconomic consequences, as well as the personal distress associated with diagnosis, are substantial.

Biochemical and anatomical evidence

Evidence is accumulating that post-traumatic stress disorder is a discrete nosological entity with biochemical, neuroanatomical, and phenomenological characteristics that differentiate it from other major psychiatric disorders. Dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in patients with post-traumatic stress disorder results in low urinary cortisol concentrations,17 raised concentrations of cerebrospinal fluid corticotrophin releasing factor,18 increased numbers of lymphocyte glucocorticoid receptor sites,17 and hypersuppression of cortisol with low dose dexamethasone.19 Recent research on the neurobiology of severe stress has shown a breakdown of the blood-brain barrier, changes in neuronal function, and altered gene expression and abnormal neurotransmitter production.20

Neuroanatomical abnormalities affecting the medial prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and visual association cortex have been identified in patients with post-traumatic stress disorder.21 These areas of the brain are involved in memory. Neurotransmitters and neuropeptides released during stress may result in overconsolidation of memory traces, giving rise to the intrusive memories of post-traumatic stress disorder.22 According to recent dual representation theory, vivid re-experiencing and ordinary biographical memories of trauma are represented by separate memory systems23 so that sensory data, associated with an emotionally important event, is stored in memory without cortical processing.

Litigation

In spite of this growing body of research supporting post-traumatic stress disorder as a separate and distinct psychiatric diagnosis, there is widespread criticism, not only of the diagnosis, but of the concept of a discrete psychiatric response to trauma. Much of this criticism has been focused on the sometimes indiscriminate use of the diagnosis in civil litigation and the apparent growth of a trauma industry. Post-traumatic stress disorder is the only psychiatric disorder for which compensation can be paid. It thus gives rise to the potential for malingering and the intentional production or exaggeration of psychiatric symptoms and disability. Although in some instances the legal process, and more specifically the promise of financial compensation, may promote and prolong psychiatric symptoms,24 the potential for secondary gain has been recognised for years in psychiatry, and studies of the effect of compensation on post-traumatic symptoms have been inconclusive.

Summerfield recently argued that in Britain, victims of trauma should resort to the “time honoured constructions” of “stiff upper lip” rather than importing the “blame culture” from the United States.2 Whether the increasing emotionality of the British people is to be applauded or deplored, depends on your political and philosophical viewpoint. However, the fact that something is not talked about does not mean that it doesn't exist, merely that we are not inconvenienced by having to think about or deal with it. It is only relatively recently, for example, that the extent and effects of domestic violence and childhood abuse have been recognised by health professionals. Before this, the problem was invisible because of the social pressure on women and children to deny their suffering. As with the arguments about psychological trauma, the increasing willingness in society for these issues to be discussed is not in itself responsible for causing the problem. Nor should the fact that many victims require treatment for a range of post-traumatic psychiatric symptoms be interpreted as an attempt by the psychiatric profession to medicalise normal human misery.

Conclusions

Post-traumatic stress disorder is precipitated by events that are distressing and disturbing not only to the person who recounts them but also to the listener. Denial of suffering may be one way of coping with distress and anxiety; accepting psychic trauma as a fact requires acknowledgement of our own vulnerability to trauma and victimisation. However, dismissing post-traumatic stress disorder as a valid diagnosis denies the ongoing suffering of people who have been exposed to severe and life threatening trauma. Although we recognise the current limitations of the diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder, especially across cultures and to victims of chronic lifelong trauma, we believe this is merely an argument for further refinement of the diagnosis, underpinned by high quality research. It is not an argument for abandoning the diagnosis altogether.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders-III. Washington, DC: APA; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Summerfield D. The invention of post-traumatic stress disorder and the social usefulness of a psychiatric category. BMJ. 2001;322:95–98. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7278.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sartorius N. International perspectives of psychiatric classification. Br J Psychiatry. 1988;152:9–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Bridging the gaps. Geneva: WHO; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Vries MW. Trauma in cultural perspective. In: Van der Kolk B, McFarlane A, Weisaeth L, editors. Traumatic stress. The effects of overwhelming experience on mind, body and society. London: Guilford Press; 1996. p. 400. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kessler RC, Zhao S, Katz SJ, Kouzis AC, Frank RG, Edlund M, et al. Past year use of outpatient services for psychiatric problems in the national comorbidity survey. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:115–123. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dilling H. Classification. In: Gelder M, Lopez-Ibor Jr JJ, Andreasen NC, editors. New Oxford textbook of psychiatry 2000. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 108–133. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dolan B, Coid J. Psychopathic and antisocial personality disorders. Treatment and research issues. London: Gaskell; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herman JL. Trauma and recovery. New York: Basic Books; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. ICD10: international classification of diseases (10th revision). Geneva: WHO; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green BL, Lindy JD, Grace MC, Leonard A. Chronic post-traumatic stress disorder and diagnostic comorbidity in a disaster sample. J Nervous Mental Dis. 1992;180:760–766. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199212000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McFarlane AC. The aetiology of post-traumatic morbidity: predisposing, precipitating and perpetuating factors. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;154:221–228. doi: 10.1192/bjp.154.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Helzer JE, Robins LN, McEvoy L. Post-traumatic stress disorder in the general population. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1630–1634. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198712243172604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes H, Nelson CB. Post-traumatic stress disorder in the national comorbidity survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kessler RC. Post-traumatic stress disorder: the burden to the individual and to society. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61:4–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kessler RC, Borges B, Walters EE. Prevalence and risk factors of lifetime suicide attempts in the national comorbidity survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:617–626. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yehuda R, Boisoneau, Mason J, Giller E. Glucocorticoid receptor number and cortisol excretion in mood, anxiety and psychotic disorders. Biological Psychiatry. 1993;34:18–25. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(93)90252-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bremner JD, Licinio J, Darnell A, Krystal J, Owens M, Southwick S, et al. Elevated CSF corticotrophin-releasing factor concentrations in post-traumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:624–629. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.5.624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stein M, Yehuda R, Koverola C, Hanna C. Enhanced dexamethasone suppression of plasma cortisol in adult women traumatised by childhood sexual abuse. Biological Psychiatry. 1997;42:680–686. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(96)00489-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaufer D, Friedman A, Seidman A, Soreq H. Acute stress facilitates long lasting changes in cholinergic gene expression. Nature. 1998;393:373–377. doi: 10.1038/30741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bremner JD, Randall P, Scott TM, Bronen RA, Seibyl JP, Southwick SM, et al. MRI-based measures of hippocampal volume in patients with PTSD. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:973–981. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.7.973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pitman RK. Post-traumatic stress disorder, hormones and memory. Biological Psychiatry. 1989;26:645–652. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(89)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brewin CR. A cognitive neuroscience account of post-traumatic stress disorder and its treatment. Behaviour Res Ther. 2001;39:373–393. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(00)00087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ehlers A, Mayou R, Bryant B. Psychological predictors of chronic PTSD after motor vehicle accidents. J Abnorm Psychol. 1998;107:508–519. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.3.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]