Abstract

Foundation models are transforming artificial intelligence (AI) in healthcare by providing modular components adaptable for various downstream tasks, making AI development more scalable and cost-effective. Foundation models for structured electronic health records (EHR), trained on coded medical records from millions of patients, demonstrated benefits including increased performance with fewer training labels, and improved robustness to distribution shifts. However, questions remain on the feasibility of sharing these models across hospitals and their performance in local tasks. This multi-center study examined the adaptability of a publicly accessible structured EHR foundation model (FMSM), trained on 2.57 M patient records from Stanford Medicine. Experiments used EHR data from The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) and Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care (MIMIC-IV). We assessed both adaptability via continued pretraining on local data, and task adaptability compared to baselines of locally training models from scratch, including a local foundation model. Evaluations on 8 clinical prediction tasks showed that adapting the off-the-shelf FMSM matched the performance of gradient boosting machines (GBM) locally trained on all data while providing a 13% improvement in settings with few task-specific training labels. Continued pretraining on local data showed FMSM required fewer than 1% of training examples to match the fully trained GBM’s performance, and was 60 to 90% more sample-efficient than training local foundation models from scratch. Our findings demonstrate that adapting EHR foundation models across hospitals provides improved prediction performance at less cost, underscoring the utility of base foundation models as modular components to streamline the development of healthcare AI.

Subject terms: Computer science, Machine learning

Introduction

Foundation models1, large-scale artificial intelligence (AI) models trained on massive amounts of unlabeled data using self-supervised learning, mark a paradigm shift for healthcare AI by moving away from bespoke, single-purpose models to generalist and more easily adaptable medical AI2. Foundation models open new opportunities to improve diagnostic and predictive capabilities, enable proactive interventions and improve patient care using a range of modalities including natural language3,4, imaging5, genomics6,7, and structured data from electronic health records (EHRs)8–11. Structured EHR foundation models, trained on tabular, timestamped event data for procedures, diagnoses, medications, and lab values as examples, offer distinct representational abilities over other modalities by focusing on encoding patients’ longitudinal medical history. This enables generating feature representations that summarize a patient’s entire medical history up to a specific time point, facilitating downstream tasks such as risk stratification and time-to-event modeling.

Recent EHR foundation models report state-of-the-art accuracy, require fewer labeled examples for task adaptation, and have demonstrated improved robustness to distribution shifts across time and patient subpopulations12,13. With model hubs (centralized repositories for pretrained model weights) playing a key role in modern AI development, sharing EHR foundation models across sites offers many practical advantages by providing a less expensive route for local hospitals to adapt a foundation model for their specific needs. More importantly, key properties of foundation models, such as their skills, domain knowledge, and biases, are highly dependent on the specific data used for pretraining14,15. Since large-scale EHR datasets (>1 million patients) are challenging to obtain for most researchers, sharing EHR foundation model weights becomes critical to advancing research into mitigating biases, improving robustness, and other properties intrinsic to a specific set of pretrained model weights. Finally, given recent arguments for regulatory oversight and quality assurance of healthcare AI models by public-private entities16, access to foundation model weights that have undergone some certification process may become a prerequisite for model deployment.

Adapting and improving existing foundation models (rather than pretraining from scratch) is the predominant workflow in domains such as NLP and computer vision. However, the absence of public structured EHR foundation models has hampered similar progress in EHR settings17. This creates challenges in advancing label/sample efficiency, few-shot learning, and general methods to improving EHR foundation models without access to the original pretraining data18. For example, work in other modalities has found that pre-training on large-scale, heterogeneous data generally improves robustness19 and that continued pretraining of existing models using in-domain data further improves performance in a target domain20. This offers a promising route to improving existing EHR foundation models at local hospitals but introduces potential challenges around catastrophic forgetting and other issues that have been underexplored due to the lack of large-scale, shared EHR models.

Although there is a growing body of work evaluating pretrained models across different hospital systems (GenHPF21, TransformEHR22) and transfer from EHR data to insurance claims (Med-BERT9), prior studies have focused on private foundation models, pretrained from scratch, and the role architectural choices play in transfer learning performance in downstream task adaptation. There has been limited exploration of label efficiency in EHR settings, where encoder-only/BERT-style models perform poorly on few-shot tasks. For example, Med-BERT required an average of 200–1000 training examples per adapted task to outperform their reported logistic regression baselines. To our knowledge, no prior work has investigated strategies for improving existing EHR foundation models via continued pretraining or evaluations on how such training impacts label efficiency in downstream, adapted task models.

To address these challenges, we present a multi-center study focused on the adaptability of CLMBR-T-base23, a recently released 141 M parameter, decoder-only Transformer model for structured EHR data. This publicly accessible foundation model was pretrained from scratch on longitudinal, structured medical records from 2.57 M patients from Stanford Medicine (FMSM) and is compatible with the widely adopted Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership Common Data Model (OMOP CDM). The model’s architecture has undergone extensive evaluation at Stanford Medicine across various settings8,12,13,23.

Our main contributions are summarized as follows:

The first multi-site evaluation of continued pretraining using a structured EHR foundation model. We evaluate cross-site, continued pretraining and adaptation for three foundation models trained from scratch and reflecting three different health systems: Stanford Medicine, SickKids (Toronto), and MIMIC-IV. We find continued pretraining improved performance in all models by an average of 3%.

We evaluate the impact of continued pretraining on few-shot performance using 8 clinician-curated evaluation tasks and training sizes ranging from 2 to 1024 examples. We find substantial improvements to label efficiency, where on average 128 training examples can match baseline performance of a GBM trained on all available task data. This significantly outperforms prior label efficiency experiments that used encoder-only architectures.

Continued pretraining results in foundation models that are similar in performance to those trained from scratch, but require 60 to 90% less patient data for pretraining.

Results

Cohort characteristics and outcome prevalence

Supplementary Fig. 1 illustrates the assignment of patients into the inpatient cohorts for the two datasets sourced from The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) in Toronto, Canada, and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) in Boston, United States. Table 1 presents patient demographic characteristics and prevalence for the 8 clinical prediction tasks within the SickKids and MIMIC inpatient cohorts. The prevalence of outcomes was highly skewed, with MIMIC having higher rates in 6/8 tasks (1.3–6 times larger than SickKids).

Table 1.

Cohort characteristics and outcome prevalence

| SickKids (n = 37,960) | MIMIC (n = 44,055) | |

|---|---|---|

| Median age [IQR] | 7 [2, 13] | 56 [35, 71] |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 20,507 (54.0%) | 17,329 (39.3%) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | b | 27,402 (62.2%) |

| Black or African American | b | 5338 (12.1%) |

| Asian | b | 1799 (4.1%) |

| Other | b | 5066 (11.5%) |

| Unknown or Unable to Obtain | b | 4450 (10.1%) |

| aOutcomes, n (%) | ||

| In-hospital Mortality | 216 (0.6%) | 1599 (3.6%) |

| Long LOS | 6115 (16.1%) | 12,215 (27.7%) |

| 30-day Readmission | 2275 (6.0%) | 259 (0.6%) |

| Hypoglycemia | 459 (1.2%) | 719 (1.6%) |

| Hyponatremia | 92 (0.2%) | 385 (0.9%) |

| Hyperkalemia | 352 (0.9%) | 375 (0.9%) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 726 (1.9%) | 1342 (3.1%) |

| Anemia | 1073 (2.9%) | 2954 (6.8%) |

IQR interquartile range, LOS length of stay, MIMIC Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care.

aRefer to text for outcome definitions.

bRace data is not routinely collected at SickKids.

Overall model performance

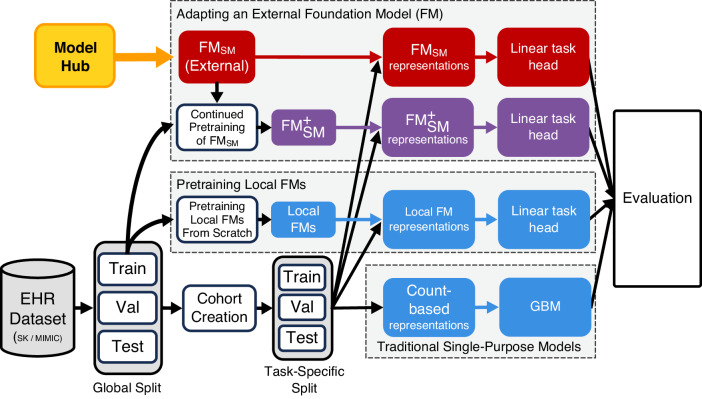

We evaluated the out-of-the-box performance of the CLMBR-T-base external foundation model (FMSM) and its performance with continued pretraining (). These results were compared against models that were locally trained from scratch, including baseline gradient boosting machines (GBMs) and local foundation models (FMs), as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Overview of model training and evaluation.

Patients in each dataset (SK and MIMIC) were globally split into training, validation, and test sets. An inpatient cohort was defined for patients in each dataset. We adopted an external FM (FMSM), CLMBR-T-base, pretrained on structured EHRs of 2.57 M patients from Stanford Medicine and used it to generate representations for each patient in the cohorts. We also conducted continued pretraining using FMSM on the global training set of each dataset and subsequently constructed patient representations using the resulting models ( and ). With these representations, we trained linear task heads (logistic regression) and compared them to locally trained models across the SK and MIMIC datasets and 8 evaluation tasks spanning operational outcomes and anticipated abnormal lab results. Abbreviations: EHR electronic health records, SK SickKids, MIMIC Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care, FM foundation model, FMSM external foundation model Stanford Medicine, CLMBR-T clinical language model based representation – transformer, GBM gradient boosting machines, Val validation.

Table 2 shows comparisons of mean area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) and expected calibration error (ECE) for FMSM and vs. the baseline GBMs. Supplementary Table 1 provides comparisons against locally trained FMs. had significantly better AUROC compared to GBM in both SickKids and MIMIC cohorts. ECE was also significantly better for FMSM and vs. GBMs in both cohorts.

Table 2.

Comparing discrimination and calibration of foundation models vs. baseline GBM approaches at each sitea

| Discrimination evaluation | Calibration evaluation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Mean AUROC | Difference [foundation model – GBM] | P-valueb | Mean ECE | Difference [foundation model - GBM] | P-valueb |

| SickKids | ||||||

| GBMSK |

0.855 [0.798, 0.904] |

0.015 [0.013, 0.017] |

||||

| FMSM |

0.880 [0.826, 0.928] |

0.024 [−0.009, 0.072] |

0.184 |

0.005 [0.003, 0.009] |

−0.010 [−0.012, −0.006] |

<0.001 |

|

0.901 [0.851, 0.944] |

0.044 [0.013, 0.099] |

0.002 |

0.006 [0.003, 0.009] |

−0.010 [−0.013, −0.006] |

<0.001 | |

| MIMIC | ||||||

| GBMMIMIC |

0.807 [0.733, 0.868] |

0.016 [0.015, 0.018] |

||||

| FMSM |

0.828 [0.775, 0.875] |

0.020 [−0.010, 0.062] |

0.230 |

0.007 [0.004, 0.012] |

−0.010 [−0.013, −0.005] |

0.002 |

|

0.848 [0.783, 0.895] |

0.039 [0.009, 0.075] |

0.006 |

0.005 [0.003, 0.009] |

−0.011 [−0.013, −0.008] |

<0.001 | |

AUROC area under the receiver operating characteristics curve, CI confidence interval, FMSM external foundation model Stanford Medicine, external foundation model Stanford Medicine with continued pretraining - SK or MIMIC, SK SickKids, MIMIC Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care, GBM gradient boosting machines.

aTable shows mean AUROC and ECE across tasks [95% hierarchical bootstrap CI].

bBolded values indicate P < 0.05.

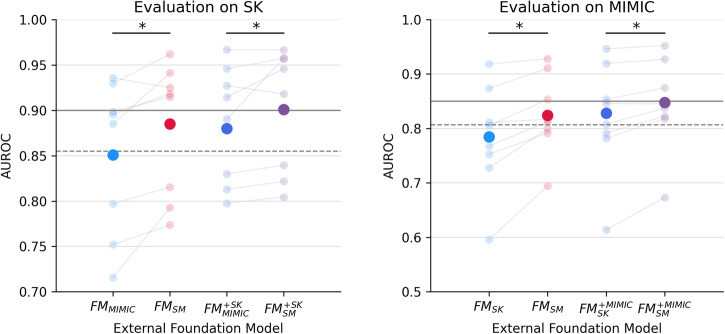

In an ablation experiment focusing on the adaptability of external foundation models across different hospitals, Fig. 2 demonstrates that FMSM and achieved significantly higher AUROC compared to FMSK and on the MIMIC dataset, and to FMMIMIC and on the SK dataset. See Table 3 for per-task AUROC and Supplementary Table 2 for per-task ECE.

Fig. 2. Comparison of external foundation models.

Comparing discrimination performance of external foundation models: FMSM vs. FMMIMIC on SK, and FMSM vs. FMSK on MIMIC. Gray lines indicate the performance of locally trained models, with the dashed lines indicating baseline GBMs and solid lines indicating the local foundation models. Bolded and faint dots indicate average and task-specific performance, respectively. Asterisks indicate significant differences at p < 0.05 evaluated using hierarchical bootstrapping. Abbreviations: AUROC area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, FMSM/FMSK/FMMIMIC external foundation model Stanford Medicine - SK or MIMIC, // external foundation model with continued pretraining – SK or MIMIC, SM Stanford Medicine, SK SickKids, MIMIC Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care.

Table 3.

Discrimination for task-specific models at two sitesa

| Model | In-hospital mortality | Long LOS | 30-day readmission | Hypoglycemia | Hyponatremia | Hyperkalemia | Thrombocytopenia | Anemia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dataset: SickKids | ||||||||

| GBMSK | 0.893 [0.815, 0.953] | 0.866 [0.853, 0.879] | 0.783 [0.755, 0.809] | 0.880 [0.830, 0.924] | 0.783 [0.579, 0.957] | 0.749 [0.687, 0.808] | 0.953 [0.928, 0.975] | 0.919 [0.898, 0.938] |

| FMMIMIC | 0.885 [0.814, 0.943] | 0.797 [0.782, 0.813] | 0.752 [0.724, 0.779] | 0.899 [0.866, 0.927] | 0.936 [0.889, 0.972] | 0.716 [0.655, 0.773] | 0.930 [0.900, 0.956] | 0.895 [0.870, 0.918] |

| 0.946 [0.912, 0.973] | 0.830 [0.816, 0.844] | 0.798 [0.773, 0.821] | 0.927 [0.901, 0.950] | 0.890 [0.789, 0.969] | 0.813 [0.767, 0.855] | 0.967 [0.953, 0.979] | 0.915 [0.892, 0.935] | |

| FMSM | 0.941 [0.902, 0.971] | 0.815 [0.800, 0.830] | 0.774 [0.747, 0.799] | 0.915 [0.879, 0.945] | 0.925 [0.880, 0.963] | 0.793 [0.743, 0.838] | 0.962 [0.946, 0.975] | 0.918 [0.897, 0.937] |

| 0.957 [0.922, 0.980] | 0.839 [0.825, 0.853] | 0.804 [0.780, 0.828] | 0.918 [0.883, 0.948] | 0.957 [0.933, 0.978] | 0.822 [0.781, 0.860] | 0.967 [0.950, 0.980] | 0.946 [0.932, 0.959] | |

| FMSK | 0.968 [0.952, 0.981] | 0.847 [0.834, 0.861] | 0.774 [0.746, 0.799] | 0.924 [0.891, 0.953] | 0.936 [0.882, 0.977] | 0.848 [0.812, 0.883] | 0.966 [0.953, 0.978] | 0.932 [0.912, 0.950] |

| Dataset: MIMIC | ||||||||

| GBMMIMIC | 0.905 [0.886, 0.922] | 0.831 [0.821, 0.841] | 0.619 [0.514, 0.719] | 0.790 [0.746, 0.830] | 0.798 [0.723, 0.863] | 0.700 [0.619, 0.775] | 0.915 [0.884, 0.943] | 0.878 [0.862, 0.893] |

| FMSK | 0.874 [0.852, 0.894] | 0.753 [0.741, 0.764] | 0.596 [0.49, 0.693] | 0.768 [0.728, 0.805] | 0.811 [0.762, 0.857] | 0.728 [0.657, 0.795] | 0.918 [0.896, 0.939] | 0.805 [0.786, 0.824] |

| 0.920 [0.904, 0.934] | 0.792 [0.781, 0.802] | 0.614 [0.507, 0.716] | 0.808 [0.774, 0.840] | 0.846 [0.801, 0.888] | 0.782 [0.726, 0.836] | 0.946 [0.929, 0.962] | 0.854 [0.837, 0.869] | |

| FMSM | 0.911 [0.894, 0.926] | 0.792 [0.781, 0.803] | 0.695 [0.601, 0.781] | 0.812 [0.779, 0.844] | 0.817 [0.771, 0.859] | 0.800 [0.739, 0.856] | 0.928 [0.909, 0.946] | 0.854 [0.836, 0.871] |

| 0.927 [0.912, 0.941] | 0.823 [0.813, 0.833] | 0.673 [0.564, 0.771] | 0.837 [0.802, 0.869] | 0.845 [0.806, 0.882] | 0.818 [0.762, 0.868] | 0.952 [0.939, 0.964] | 0.875 [0.859, 0.890] | |

| FMMIMIC | 0.93 [0.916, 0.944] | 0.826 [0.816, 0.836] | 0.690 [0.589, 0.784] | 0.838 [0.806, 0.869] | 0.845 [0.799, 0.887] | 0.814 [0.763, 0.862] | 0.950 [0.934, 0.964] | 0.887 [0.872, 0.900] |

AUROC area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, GBM gradient boosting machines, FMSM/FMSK/FMMIMIC foundation model Stanford Medicine, SickKids, or MIMIC, external foundation model with continued pretraining - SK or MIMIC, SK SickKids, MIMIC Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care, LOS length of stay, CI confidence interval.

aTable shows AUROC (95% bootstrap CI) for each task; bolded values indicate highest AUROC across models.

Few-shot performance

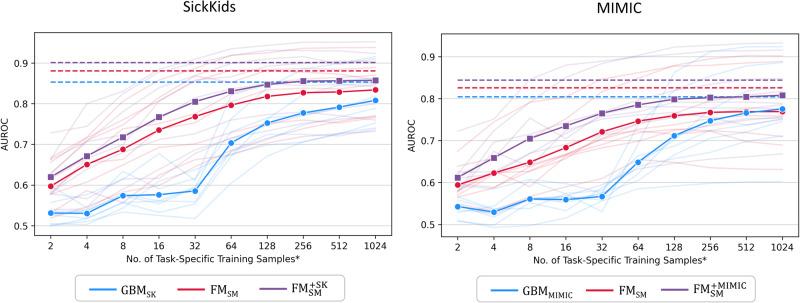

In the few-shot experiments, we evaluated the label efficiency of our models by limiting the number of task-specific training examples to values between 2 and 1024, increasing in powers of 2 (see Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 3). FMSM and consistently demonstrated significantly improved AUROC compared to GBM across almost all few-shot settings in both datasets (13% improvement on average for FMSM and 19% for ). Furthermore, matched mean AUROC of GBM using as little as 128 samples (64 samples per class; fewer than 1% of all training examples). Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 4 show that FMSM and generally demonstrated lower ECE against GBM although the difference was not statistically significant in some settings, for example in 32-, 512-, and 1024-shot settings for SK.

Fig. 3. Few-shot performance.

Discrimination of external foundation model (FMSM), external foundation model with continued pretraining () and baseline GBM using decreasing training samples at SickKids and MIMIC. Bolded and faint lines indicate average and task-specific performance, respectively. Dashed lines indicate mean AUROC of models trained on all training samples. * The number of training examples for each class is up to half of the number of task-specific training samples. Abbreviations: AUROC area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, FMSM external foundation model Stanford Medicine, external foundation model Stanford Medicine with continued pretraining – SK or MIMIC, SK SickKids, MIMIC Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care, GBM gradient boosting machines.

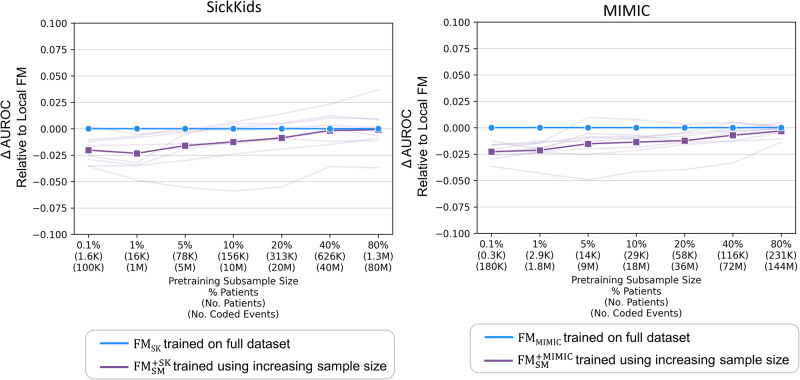

Performance with varying pretraining sample size

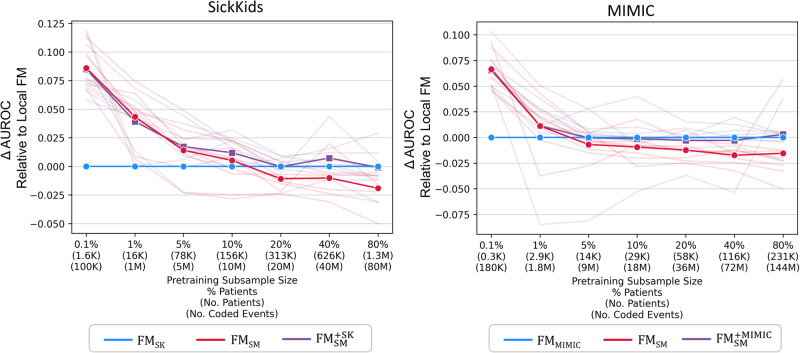

In the experiments examining the impact of varying pretraining sample sizes, we investigated the performance differences between the external foundation models (FMSM and ) and locally trained foundation models. Figure 4 and Supplementary Table 5 demonstrate that AUROCs for external foundation models were significantly better than local foundation models with very small subsamples (up to 1% for SickKids and 0.1% for MIMIC). Without continued pretraining, AUROC for FMSK was significantly better than FMSM when subsamples reached 80% for SickKids. In contrast, AUROC for local FMs and did not differ significantly across larger subsamples. Calibration results, detailed in Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 6, did not significantly vary between models.

Fig. 4. External vs. local foundation models with varying pretraining sample sizes.

Discrimination of external foundation model (FMSM) and external foundation model with continued pretraining () relative to local foundation model (FMSK and FMMIMIC) using decreasing pretraining sample size. Bolded and faint lines indicate average and task-specific performance relative to local foundation models, respectively. The subsample size is not relevant for FMSM, which did not undergo additional pretraining. Note, the model AUROC scores are relative to the baseline local models (FMSK and FMMIMIC) and the absolute AUROC does change across sample sizes. Abbreviations: AUROC area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, FMSM external foundation model Stanford Medicine, external foundation model Stanford Medicine with continued pretraining – SK or MIMIC, FMSK/FMMIMIC local foundation models – SK or MIMIC, SK SickKids, MIMIC Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care.

Figure 5 and Supplementary Table 7 show that the performance of continued pretraining with subsamples of 10% or more for SK and 40% or more for MIMIC did not significantly differ from that of local foundation models (FMSK and FMMIMIC) trained from scratch on all data. In addition, continued pretraining was more efficient than pretraining from scratch (70.2% faster than FMSK and 58.4% faster than FMMIMIC), as shown in Supplementary Fig. 4. Furthermore, as demonstrated in Supplementary Fig. 5, FMSM and generally processed fewer coded events (50.9% less in SK and 30.9% less in MIMIC) than local foundation models as a result of reduced code coverage.

Fig. 5. Continued pretraining of external foundation vs. fully trained local foundation model.

Discrimination of (external foundation model Stanford Medicine with continued pretraining) using increasing pretraining sample size relative to discrimination of local foundation models (FMSK and FMMIMIC) pretrained using all data. Bolded and faint lines indicate average and task-specific performance relative to local foundation models (FMSK and FMMIMIC), respectively. Abbreviations: AUROC area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, external foundation model Stanford Medicine with continued pretraining - SK or MIMIC, FMSK/FMMIMIC local foundation model – SK or MIMIC, SK SickKids, MIMIC Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care.

Discussion

Our multi-center study has demonstrated that adapting an off-the-shelf external foundation model (FMSM) can yield comparable discrimination and better calibration compared to baseline GBM models locally trained on all available data at each site, while providing 13% discrimination improvement in settings with few task-specific training labels. With continued pretraining on local data, significantly better discrimination and calibration were observed compared to baseline GBM models. In addition, label efficiency substantially improved, such that using only 128 training examples (64 samples per class; less than 1% of the total data), matched the performance of the GBMs training using all available data. Furthermore, continued pretraining of FMSM requires 60 to 90% less patient data than local pretraining from scratch to achieve the same level of performance, demonstrating better sample efficiency. Our findings also provided insights into when it is beneficial to adapt an existing EHR foundation model vs. pretraining from scratch, depending on data availability.

The development of single-purpose models entails significant costs24. These costs escalate further for EHR foundation models, which require access to extensive patient records and substantial computing resources. Our findings highlight the potential for cost savings by sharing and building upon pretrained EHR foundation models across hospitals. Adapting these models to new tasks significantly reduces the amount of training labels needed, thereby lowering label acquisition costs and speeding up the deployment of new applications. Moreover, for institutions equipped to conduct pretraining, the continued pretraining of an existing foundation model is considerably more data- and compute-efficient compared to pretraining from scratch.

Our results contribute to recent work demonstrating the robustness of EHR foundation models to various distribution shifts12,13. Compared to traditional single-purpose models that often fall short in adaptability across sites25,26, EHR foundation models demonstrate a notable capacity to encode patients’ longitudinal medical history and local care nuances. Despite challenges posed by dataset shifts, notably in patient populations and coding variations as evidenced by the number of unprocessed codes by FMSM across all patient timelines at each site, the external foundation model displayed robust performance. Moreover, our results indicate that pretraining on a larger and more diverse patient population improves the adaptability of the foundation model across healthcare settings. It is noteworthy that a single external foundation model consistently achieved strong performance across both a Canadian pediatric cohort and an American adult ICU-based cohort. Our findings point towards a paradigm where, instead of training bespoke models for each healthcare site from scratch, the focus shifts to the development and sharing of larger, general-purpose base foundation models and recipes for site-specific refinement, such as continued pretraining.

To leverage the transfer learning capabilities of pretrained foundation models, it is important to adhere to the underlying data schema and vocabulary of tokens used by these models. For this reason, we mapped our datasets to the OMOP CDM. Progress is required to define minimal schema requirements for training foundation models to mitigate costs associated with mapping to a common data model. Alternatively, developing EHR foundation models that are robust to schema shifts27, akin to multilingual language models, represents a valuable direction for future research.

Sharing foundation models across hospitals needs to address privacy and ethical use of the underlying data. For EHR foundation models, adopting measures such as training on data de-identified to HIPAA standards, acquiring patient consent, and restricting access to accredited individuals11 are important first steps. Despite these efforts, issues like potential misuse (e.g., for surveillance) and the challenge of algorithmic biases remain open research questions1,28, underscoring the ongoing challenges in maintaining privacy and mitigating risks in medical foundation models.

This study has several strengths and limitations. A primary strength of this study is that it represents one of the first external evaluation of a publicly available foundation model specifically for structured EHR data. Additionally, we have characterized the utility of the foundation model across diverse evaluation settings. On the limitation side, this study was conducted using a limited number of hospital datasets and tasks, which may not capture the full spectrum of EHR variability. We did not explore methods for harmonizing across schemas, which could impact the adaptability of the foundation model. We do not explore trade-offs of relative set sizes of training vs validation data when conducting few-shot learning, which may impact reported performance. We also did not explore questions on fairness and the propagation of biases potentially associated with sharing foundation models. Moreover, the study emphasized a specific foundation model, CLMBR-T-base, due to lack of publicly available structured EHR foundation models17. Lastly, while the benefits of continued pretraining are clear, they may not be accessible to institutions that lack resources to perform it, potentially limiting broader applicability.

In conclusion, our findings show that adapting a pretrained EHR foundation model for downstream tasks across hospitals can improve prediction performance at less cost, underscoring the effectiveness of sharing base foundation models as modular machine learning components to streamline the development of healthcare AI.

Methods

Hospital datasets

This retrospective multi-center study utilized EHR data collected from two institutions, The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) in Toronto, Canada, and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) in Boston, United States.

The SickKids (SK) dataset was sourced from the SickKids Enterprise-wide Data in Azure Repository (SEDAR)29 and contains EHR data for 1.8 M patients collected from June 2018 to March 2023. The MIMIC dataset (MIMIC-IV version 1.0)30,31 encompasses data from 340 K patients admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU) or the emergency department at BIDMC between 2008 and 2019. To meet the schema requirements of the external foundation model, both datasets are mapped to the widely adopted Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership Common Data Model (OMOP-CDM). Mapping for MIMIC was done using code from the MIMIC project as part of Observational Health Data Sciences and Informatics32.

The SickKids Research Ethics Board (REB) approved the use of SEDAR for this research (REB number: 1000074527). Data from MIMIC-IV was approved under the oversight of the Institutional Review Boards (IRB) of BIDMC and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Data access was credentialed under the oversight of the data use agreement through PhysioNet31.

Models

Our baseline approach employed a conventional count-based featurization approach33,34 to create representations for each patient, task, and cohort, detailed further in Supplementary Table 8. Using these representations, we trained GBM models using LightGBM35 on the task-specific training sets, resulting in GBMSK for SK and GBMMIMIC for MIMIC. We considered the choice of optimization algorithm as a hyperparameter. Detailed hyperparameter settings are available in Supplementary Table 9, with tuning performed on the task-specific validation sets to optimize for log loss.

For the external foundation model (FMSM), we selected CLMBR-T-base23 because it is the only publicly available EHR foundation model that has also undergone extensive evaluation8,12,13,23. FMSM processes sequences of clinical events as inputs, where each sequence represents the medical timeline of an individual patient, with each denoting the i-th code, encompassing any form of structured data obtained from the patient’s EHR, such as a diagnosis, procedure, medication, or lab test as examples. The architecture of the model comprises 12 stacked transformer layers with a local attention mechanism, totaling 141 million parameters. It was pretrained on structured EHRs from 2.57 million patients receiving care at Stanford Health Care and Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital between 2008 and 2022. CLMBR-T-base is a decoder-only model, autoregressively pretrained to predict the next clinical event based on the preceding sequence, similar to GPT pretraining. The vocabulary is defined as the top 65,536 codes from the union of all codes in 21 source ontology mappings (e.g. LOINC, SNOMED, RxNorm) provided by Athena’s OMOP vocabulary list. The top codes were selected based on global code frequency in the original pretraining dataset. Codes not in the vocabulary were dropped.

In our experiments, we used FMSM out-of-the-box as a frozen feature encoder, transforming the sequence of clinical events X for each patient into a dense vector representation , with the model’s parameters θ fixed during this encoding process. The obtained representations were then used to train linear task heads (also known as linear probes36) on the task-specific training sets. Specifically, we utilized L2-regularized logistic regression models from Sci-kit Learn37 with the LBFGS solver as our linear task heads. We conducted hyperparameter tuning on the task-specific validation sets (see Supplementary Table 2 for hyperparameter settings) to optimize for log loss.

In addition, we tailored FMSM to each dataset separately by performing continued pretraining, using patient timelines from each dataset, resulting in and . Continued pretraining uses the same next-code, autoregressive prediction task used during the original pretraining run. Pretraining resumed on the global training set, tuning the learning rate using global validation set performance. Pretraining continued for up to 10 million steps, with early stopping implemented if the validation loss did not improve for 15,000 steps. Once continued pretraining was complete, the training of linear task heads followed the same procedure as FMSM.

Lastly, we pretrained local foundation models from scratch on each dataset using up to 1.6 M patients (100 M coded events) for SK and 290 K (180 M coded events) for MIMIC, resulting in FMSK and FMMIMIC. FMSK and FMMIMIC shared the same architecture as FMSM. Hyperparameter tuning followed the same procedure as continued pretraining.

Computation resources

Pretraining was executed on an on-premises cluster of up to 4 Nvidia V100 GPUs.

Clinical prediction tasks, prediction times, and observation window

We defined 8 binary clinical prediction tasks. The binary classification setting is standard and particularly well-suited for the class of models being evaluated, and the tasks were selected based on clinical relevance, alignment with previous benchmarks13,23, and previous validation work38. The tasks were categorized into two groups: operational tasks and predicting clinically relevant abnormal lab results. Operational tasks encompassed in-hospital mortality, long length of stay of at least 7 days (long LOS), readmission within 30 days of discharge (30-day readmission). Tasks related to predicting abnormal lab-based results included hypoglycemia (serum glucose <3 mmol/L)39, hyponatremia (serum sodium <125 mmol/L)40, hyperkalemia (serum potassium >7 mmol/L)41, anemia (hemoglobin <70 g/L)42, and thrombocytopenia (platelet count <50 ×109/L).

The prediction time for the 30-day readmission task was set at midnight on the day of discharge. For all other tasks, the prediction time was set at midnight on the day of admission. The prediction window extended until discharge for all tasks, with the exception of the readmission task, which utilized a 30-day window post-discharge. The observation window for model input encompassed all available patient data up to the prediction time.

Inpatient cohort and data splitting procedure

SickKids inpatients were those 28 days of age or older at admission. MIMIC inpatients were those 18 years of age or older at admission. In cases where patients had multiple admissions, we randomly selected one admission for inclusion. We excluded admissions in which patient death or discharge occurred between admission and prediction time. Additionally, for each clinical prediction task, we excluded admissions in which the outcome occurred between admission (or discharge) and prediction time.

We defined global training, validation, and test sets for each dataset in a 70/15/15 ratio across all patients used for continued pretraining and local foundation models. Subsequently, for each inpatient cohort, we derived task-specific training, validation, and test sets. The task-specific sets were subsets of the global sets, thereby preserving the 70/15/15 distribution.

Experiments

We assessed models’ overall performance by comparing discrimination (AUROC) and calibration (expected calibration error, ECE) of FMSM and FMSM with continued pretraining ( vs. the baseline GBM across all clinical prediction tasks using the task-specific test set of each dataset. We also compared discrimination and calibration of FMSM and with local foundation models (FMSK and FMMIMIC). In an ablation experiment, we evaluated the adaptability of FMSM against FMSK and FMMIMIC, hypothesizing that FMSM’s training on a larger and more heterogenous patient population makes it more adaptable across healthcare sites. To this end, we examined the performance of FMSK on MIMIC and FMMIMIC on SK as external foundation models, including their performance with continued pretraining ( and ), compared to FMSM and .

Next, we compared FMSM and continued pretraining of FMSM against the baseline GBM in the setting of decreasing training samples to evaluate label efficiency. For each task, we varied the number of training examples (k) within (2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512, 1024). These examples consisted of an equal number of positive and negative instances, except for tasks with kp positive instances, where kp < k/2. For such tasks, we included all kp positive instances in our training data. The training examples were drawn from a subset of the task-specific training set, while validation and test sets remained the same. We do not k-sample the validation set under the assumption that hospitals, in practice, will have access to larger task sets for evaluating model performance. In order to ensure an unbiased performance estimate, we removed all task-specific training sets from pretraining for these experiments to ensure that pretraining is not unfairly advantaged by being able to see more examples of a particular task. The procedures for training baseline GBM and linear task heads for foundation models were kept consistent for the few-shot experiments. We performed 20 iterations of sampling, task-specific training, and evaluation for each value of k. Notably, our method of training linear task heads on FMSM and across all experiments does not involve fine-tuning the foundation model parameters, representing a conservative approach. In contrast, the baseline GBMs underwent extensive hyperparameter tuning, including adjustments to the optimization algorithm, to optimize performance.

Lastly, we evaluated the effect of decreasing pretraining sample size on the performance of continued pretraining ( and ) and pretraining local foundation models from scratch (FMSK and FMMIMIC). Our aims were twofold: 1) to provide insight into the decision of whether to employ or tailor (via continued pretraining) FMSM versus pretraining from scratch, depending on sample size availability; and 2) to determine if continued pretraining is more sample efficient than pretraining from scratch. For the first aim, we compared the performance of FMSM with and without continued pretraining against local FMs at each sample size. For the second aim, we assessed how continued pretraining at various sample sizes compared to local FMs trained on the entire dataset. The subsamples used varied from 0.1% to 80% of the global training set, for both continued pretraining and pretraining from scratch.

Model evaluation and statistical analysis

We evaluated each model’s discrimination performance in the task-specific test sets using the AUROC. Calibration was measured in terms of the ECE using 10 quantile bins for the predicted risks. To calculate ECE in the few-shots experiment, we determined the corrected predicted risk p’ based on the predicted risk p and the task-specific outcome rate b’ using Formula (1). The correction accounts for biases in the model’s predictions as a result of balanced sampling used during few-shot training43.

| 1 |

Differences between model performances were statistically evaluated using a hierarchical bootstrapping method, which samples both patients and outcomes with replacement44. In the few-shots experiments, we averaged the performance across all sampling iterations. For each statistical evaluation, we calculated a two-tailed P-value by multiplying the one-sided P-value by 2, where the one-sided P-value represents the smaller proportion of bootstrap differences either to the left of 0 (the null value) or to the right of 045. For all tests, a P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Joshua Lemmon and Jiro Inoue for their contributions to the curation of the datasets used in this study. We would like to also thank Stephen R. Pfohl for his contributions to model evaluation. L.S. is supported by the Canada Research Chair in Pediatric Oncology Supportive Care. No external funding was received for the study.

Author contributions

L.L.G. and J.F. are co-first authors. L.S. and N.S. are co-senior authors. L.L.G., J.F., and L.S. conceptualized and designed the study with input from E.S., S.F., K.M., C.A., J.P., and N.S. L.L.G. performed all experiments. E.S. contributed to the codebase. L.L.G., J.F., and L.S. analyzed and interpreted results with input from all authors. L.L.G. and J.F. wrote the manuscript. All authors revised and commented on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

The SickKids dataset cannot be made publicly available because of the potential risk to patient privacy. However, relevant data are available upon reasonable request. The MIMIC-IV dataset is available from https://mimic.mit.edu/docs/iv/. Details of the CLMBR-T-base external foundation model are available from https://ehrshot.stanford.edu/. Full model weights of CLMBR-T-base are available from https://huggingface.co/StanfordShahLab/clmbr-t-base.

Code availability

The code for the analyses conducted in this study is open-source and available at https://github.com/sungresearch/femr-on-sk and https://github.com/sungresearch/femr-on-mimic.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Lin Lawrence Guo, Jason Fries.

These authors jointly supervised this work: Nigam Shah, Lillian Sung.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41746-024-01166-w.

References

- 1.Bommasani, R. et al. On the opportunities and risks of foundation models. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2108.07258 (2021).

- 2.Moor M, et al. Foundation models for generalist medical artificial intelligence. Nature. 2023;616:259–265. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-05881-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singhal K, et al. Large language models encode clinical knowledge. Nature. 2023;620:172–180. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-06291-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singhal, K. et al. Towards Expert-Level Medical Question Answering with Large Language Models. Preprint at 10.48550/arXiv.2305.09617 (2023).

- 5.Azizi S, et al. Robust and data-efficient generalization of self-supervised machine learning for diagnostic imaging. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2023;7:756–779. doi: 10.1038/s41551-023-01049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nguyen, E. et al. HyenaDNA: long-range genomic sequence modeling at single nucleotide resolution. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS '23), 43177–43201 (Curran Associates Inc., Red Hook, NY, USA, 2024).

- 7.Cui, H. et al. scGPT: toward building a foundation model for single-cell multi-omics using generative AI. Nat Methods (2024). 10.1038/s41592-024-02201-0. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Steinberg E, et al. Language models are an effective representation learning technique for electronic health record data. J. Biomed. Inform. 2021;113:103637. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2020.103637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rasmy L, Xiang Y, Xie Z, Tao C, Zhi D. Med-BERT: pretrained contextualized embeddings on large-scale structured electronic health records for disease prediction. NPJ Digital Med. 2021;4:1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41746-021-00455-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Y, et al. BEHRT: transformer for electronic health records. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-62922-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steinberg, E., Xu, Y., Fries, J. & Shah, N. MOTOR: A Time-To-Event Foundation Model For Structured Medical Records. Preprint at 10.48550/arXiv.2301.03150 (2023).

- 12.Guo LL, et al. EHR foundation models improve robustness in the presence of temporal distribution shift. Sci. Rep. 2023;13:3767. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-30820-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lemmon, J. et al. Self-supervised machine learning using adult inpatient data produces effective models for pediatric clinical prediction tasks. J. Am. Med. Inf. Assoc., ocad175, 10.1093/jamia/ocad175 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Liang, P. et al. Holistic Evaluation of Language Models. Trans. Mach. Learn. Res. (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Chen, M.F. et al. Skill-it! A data-driven skills framework for understanding and training language models. Proc. Thirty-seventh Conf. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. (2023).

- 16.Shah NH, et al. A Nationwide Network of Health AI Assurance Laboratories. JAMA. 2024;331:245–249. doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.26930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wornow M, et al. The shaky foundations of large language models and foundation models for electronic health records. npj Digital Med. 2023;6:135. doi: 10.1038/s41746-023-00879-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adila, D., Shin, C., Cai, L. & Sala, F. Zero-Shot Robustifi cation of Zero-Shot Models. Preprint at 10.48550/arXiv.2309.04344 (2023).

- 19.Hendrycks, D., Mazeika, M., Kadavath, S. & Song, D. Using self-supervised learning can improve model robustness and uncertainty. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32 (NeurIPS, 2019).

- 20.Gururangan, S. et al. Don’t Stop Pretraining: Adapt Language Models to Domains and Tasks. in Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (eds Jurafsky, D., Chai, J., Schluter, N., Tetreault, J.) 8342–8360 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2020). https://aclanthology.org/2020.acl-main.740.

- 21.Hur, K. et al. GenHPF: General Healthcare Predictive Framework for Multi-task Multi-source Learning. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inf. 1–12, 10.1109/JBHI.2023.3327951 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Yang Z, Mitra A, Liu W, Berlowitz D, Yu H. TransformEHR: transformer-based encoder-decoder generative model to enhance prediction of disease outcomes using electronic health records. Nat. Commun. 2023;14:7857. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-43715-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wornow, M., Thapa, R., Steinberg, E., Fries, J. & Shah, N. EHRSHOT: An EHR Benchmark for Few-Shot Evaluation of Foundation Models. Preprint at 10.48550/arXiv.2307.02028 (2023).

- 24.Sendak MP, Balu S, Schulman KA. Barriers to Achieving Economies of Scale in Analysis of EHR Data. A Cautionary Tale. Appl Clin. Inf. 2017;8:826–831. doi: 10.4338/ACI-2017-03-CR-0046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong A, et al. External validation of a widely implemented proprietary sepsis prediction model in hospitalized patients. JAMA Intern. Med. 2021;181:1065–1070. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.2626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang, H. et al. in Proceedings of the Conference on Health, Inference, and Learning 279–290 (Association for Computing Machinery, Virtual Event, USA, 2021).

- 27.Hur, K. et al. Unifying Heterogeneous Electronic Health Records Systems via Text-Based Code Embedding. Proc. Conf. Health Inference Learn. Proc. Mach. Learn. Res. 174, 183–203 (2022).

- 28.Jones, C. et al. No Fair Lunch: A Causal Perspective on Dataset Bias in Machine Learning for Medical Imaging. Preprint at 10.48550/arXiv.2307.16526 (2023).

- 29.Guo LL, et al. Development and validation of the SickKids Enterprise-wide Data in Azure Repository (SEDAR) Heliyon. 2023;9:e21586. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e21586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson, A. et al. MIMIC-IV (version 1.0). 10.13026/s6n6-xd98 (2021).

- 31.Goldberger A, et al. PhysioBank, PhysioToolkit, and PhysioNet: Components of a new research resource for complex physiologic signals. Circulation. 2000;101:e215–e220. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.101.23.e215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.OHDSI. MIMIC, https://github.com/OHDSI/MIMIC (2021).

- 33.Rajkomar A, et al. Scalable and accurate deep learning with electronic health records. NPJ Digital Med. 2018;1:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41746-018-0029-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reps JM, Schuemie MJ, Suchard MA, Ryan PB, Rijnbeek PR. Design and implementation of a standardized framework to generate and evaluate patient-level prediction models using observational healthcare data. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2018;25:969–975. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocy032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ke, G. et al. in LightGBM: a highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree, Proc. of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 3149–3157 (Curran Associates Inc., Long Beach, California, USA, 2017).

- 36.Kumar, A. et al. Fine-Tuning can Distort Pretrained Features and Underperform Out-of-Distribution. Proc. Int. Conf. Learn. Represent. (2022)

- 37.Pedregosa F, et al. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011;12:2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guo, L.L. et al. Characterizing the limitations of using diagnosis codes in the context of machine learning for healthcare. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 24, 51 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Abraham MB, et al. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2018: Assessment and management of hypoglycemia in children and adolescents with diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes. 2018;19:178–192. doi: 10.1111/pedi.12698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spasovski G, et al. Clinical practice guideline on diagnosis and treatment of hyponatraemia. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2014;170:G1–G47. doi: 10.1530/EJE-13-1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Daly K, Farrington E. Hypokalemia and hyperkalemia in infants and children: pathophysiology and treatment. J. Pediatr. Health Care. 2013;27:486–496. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Allali S, Brousse V, Sacri AS, Chalumeau M, de Montalembert M. Anemia in children: prevalence, causes, diagnostic work-up, and long-term consequences. Expert Rev. Hematol. 2017;10:1023–1028. doi: 10.1080/17474086.2017.1354696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Elkan, C. The foundations of cost-sensitive learning. In Proceedings of the 17th international joint conference on Artificial intelligence, 973–978 (ACM, 2001).

- 44.Sellam, T. et al. The MultiBERTs: BERT Reproductions for Robustness Analysis. Proc. Int. Conf. Learn. Represent. (2022).

- 45.Rousselet GA, Pernet CR, Wilcox RR. The Percentile Bootstrap: A Primer With Step-by-Step Instructions in R. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychological Sci. 2021;4:2515245920911881. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The SickKids dataset cannot be made publicly available because of the potential risk to patient privacy. However, relevant data are available upon reasonable request. The MIMIC-IV dataset is available from https://mimic.mit.edu/docs/iv/. Details of the CLMBR-T-base external foundation model are available from https://ehrshot.stanford.edu/. Full model weights of CLMBR-T-base are available from https://huggingface.co/StanfordShahLab/clmbr-t-base.

The code for the analyses conducted in this study is open-source and available at https://github.com/sungresearch/femr-on-sk and https://github.com/sungresearch/femr-on-mimic.