Abstract

The transition from mitosis to meiosis is a critical event in the reproductive development of all sexually reproducing species. However, the mechanisms that regulate this process in plants remain largely unknown. Here, we find that the rice (Oryza sativa L.) protein RETINOBLASTOMA RELATED 1 (RBR1) is essential to the transition from mitosis to meiosis. Loss of RBR1 function results in hyper-proliferative sporogenous-cell-like cells (SCLs) in the anther locules during early stages of reproductive development. These hyper-proliferative SCLs are unable to initiate meiosis, eventually stagnating and degrading at late developmental stages to form pollen-free anthers. These results suggest that RBR1 acts as a gatekeeper of entry into meiosis. Furthermore, cytokinin content is significantly increased in rbr1 mutants, whereas the expression of type-B response factors, particularly LEPTO1, is significantly reduced. Given the known close association of cytokinins with cell proliferation, these findings imply that hyper-proliferative germ cells in the anther locules may be attributed to elevated cytokinin concentrations and disruptions in the cytokinin pathway. Using a genetic strategy, the association between germ cell hyper-proliferation and disturbed cytokinin signaling in rbr1 has been confirmed. In summary, we reveal a unique role of RBR1 in the initiation of meiosis; our results clearly demonstrate that the RBR1 regulatory module is connected to the cytokinin signaling pathway and switches mitosis to meiosis in rice.

Key words: RETINOBLASTOMA RELATED1, meiosis initiation, cytokinin, rice

This study provides evidence demonstrating that rice RBR1 serves as a molecular switch between mitosis and meiosis. The absence of LEPTO1 in rbr1-1 lepto1 exacerbates the impaired meiosis entry of rbr1 mutants, suggesting that RBR1 governs the transition from mitosis to meiosis through interactions with the cytokinin signaling pathway.

Introduction

Sexual reproduction is the predominant form of reproduction in eukaryotic species; it increases genetic diversity by initiating the meiotic cell cycle in the germline, thus improving evolutionary fitness at the population scale. The most important biological event in the reproductive development of all sexually reproducing species is the transition from the mitotic to the meiotic cell cycle in the germline, which is known as meiosis initiation. Although the regulatory mechanisms that control meiotic recombination are highly conserved among eukaryotes, the signaling cascade that triggers meiosis initiation varies greatly among species (Pawlowski et al., 2007; Böwer and Schnittger, 2021). For example, in both budding and fission yeast, decreased nutrient availability leads to inhibition of target of rapamycin complex I (TORC1), which activates inducer of meiosis 1 (IME1) in budding yeast but Ste11 in fission yeast. These transcription factors then activate multiple genes involved in meiotic entry and homologous recombination (Otsubo and Yamamoto, 2012; Weidberg et al., 2016). In mammals, meiotic entry displays sexual dimorphism, with differences in timing between male and female individuals. Despite the differences in meiotic entry timing, studies in mice have revealed that retinoic acid (RA) initiates meiosis in both sexes and that RA levels in the gonads are regulated by CYP26B1 (Bowles et al., 2006; Koubova et al., 2006). STIMULATED BY RETINOIC ACID GENE 8, a factor found only in vertebrates, is a downstream target of RA that has been shown to control premeiotic DNA replication and early meiotic processes, thus playing a pivotal role in meiosis initiation (Baltus et al., 2006; Anderson et al., 2008). Overall, studies performed to date have revealed a lack of interspecies conservation among meiosis-triggering signals and master regulators of meiosis entry.

In mammals, the germline is determined during the early stages of embryogenesis and remains the same throughout an organism’s lifespan (Juliano and Wessel, 2010). By contrast, plant somatic tissues initiate the germline de novo during post-embryonic development. In flowering plants, reproductive organs (ovules on the female side and anthers on the male side) are formed during the reproductive stage after embryogenesis. In these organs, a small proportion of somatic pluripotent stem cells acquire the reproductive fate and become archesporial cells (ARs) (Walbot and Egger, 2016; Pinto et al., 2019). This process of generating reproductive stem cells is referred to as germline stem cell initiation. ARs in anthers then undergo the mitotic cell cycle, producing sporogenous cells (SCs). Germline stem cells, including ARs and SCs, possess properties of both stem cells and germ cells, including continuous mitotic cell division, large cell and nucleus sizes, and high expression of germ-cell-specific genes. Eventually, these cells irreversibly differentiate into meiocytes called pollen mother cells (PMCs) in the anthers (Ma, 2005; Walbot and Egger, 2016). This process, known as meiosis initiation, is a special type of cell differentiation. Compared with that in yeast and mice, this cell fate transition in plants appears to be controlled by more complicated mechanisms, involving master transcription factors, epigenetic and post-transcriptional regulation, hormone and oxidative signaling, and the cell-cycle machinery (Böwer and Schnittger, 2021).

Previous studies have indicated that the classical nuclear protein SPOROCYTELESS (SPL) plays a pivotal role in the process of germline initiation. Loss of SPL function leads to the absence of megaspore mother cells (MMCs) and PMCs and to the formation of vacuolated sporangia. SPL, a transcriptional repressor, may regulate MMC formation by recruiting TOPLESS/TOPLESS-RELATED transcriptional corepressors to suppress expression of the CINCINNATA-like TEOSINTE BRANCHED 1/CYCLOIDEA/PCF transcription factors (Yang et al., 1999; Ren et al., 2018; Mendes et al., 2020). Furthermore, many studies have revealed that components of the RNA-dependent DNA methylation (RdDM) pathway are involved in female germline initiation and that SPL expression is regulated by the RdDM pathway (Mendes et al., 2020). Knockout of factors related to the RdDM pathway, such as RNA-DEPENDENT RNA POLYMERASE 6, some ARGONAUTE family members, SUPPRESSOR OF GENE SILENCING 3, MNEME, DOMAINS REARRANGED METHYLTRANSFERASE 1, and DOMAINS REARRANGED METHYLTRANSFERASE 2, leads to production of an ectopic MMC-like cell (Yoshikawa et al., 2005; Olmedo-Monfil et al., 2010; Matzke and Mosher, 2014; Hernandez-Lagana et al., 2016). In some mutants, including rdr6, drm1 drm2, and ago9, SPL expression in the ovule is significantly upregulated (She et al., 2013; Mendes et al., 2020). In addition, other proteins involved in epigenetic regulation, such as the THO complex, MEL1, and MEL2, are essential for germline formation (Nonomura et al., 2007, 2011; Su et al., 2020). The cytokinin and auxin signaling pathways are also known to be integral to germ cell fate acquisition. Cytokinin treatment can induce SPL and PIN1 expression, and SPL is required for PIN1 expression (Bencivenga et al., 2012). These findings imply that SPL is involved in mediating the auxin and cytokinin pathways to regulate female germline initiation. Furthermore, SPL is known to act downstream of the auxin biosynthesis factors TAA1 and TAR2 in the process of male germ cell formation in Arabidopsis anthers (Zheng et al., 2021). In rice, the cytokinin type-B response regulator LEPTOTENE1 (LEPTO1) is known to be critical in germ cell development (Zhao et al., 2018).

RETINOBLASTOMA (Rb) is a well-characterized mammalian tumor suppressor that is involved in controlling the cell cycle, cell differentiation, and stem cell behavior (Desvoyes and Gutierrez, 2020). Homologs in plants, designated RETINOBLASTOMA RELATED 1 (RBR1), are involved in similar processes, including germ cell formation (Ebel et al., 2004; Ingouff et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2009, 2011; Borghi et al., 2010; Zhao et al., 2017; Duan et al., 2019). In Arabidopsis, rbr1 mutants display abnormal germ cell initiation, as shown by the abnormal formation of multiple MMCs and PMCs. These rbr1 phenotypes are similar to those of the septuple KRP (KIP-RELATED PROTEIN) mutant and the krp4 krp6 krp7 triple mutant (Zhao et al., 2017). KRP genes encode cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors and function upstream of RBR1 to regulate germline initiation by repressing CDKA;1 expression. In addition, the E2F core cell-cycle regulators, which are canonical Rb-interacting proteins, are also implicated in germ cell formation. The e2fa e2fb e2fc triple mutant forms supernumerary MMCs, similar to those of rbr1 mutants (Yao et al., 2018). Interestingly, WUSCHEL (WUS) is abnormally accumulated in MMCs of ovules in the krp4 krp6 krp7 and rbr1 mutants. This is thought to result from direct binding of RBR1 to the WUS promoter region as a transcriptional repressor, and depletion of WUS can partially restore the wild-type phenotype in rbr1 mutants (Zhao et al., 2017). Collectively, these findings demonstrate the importance of cell-cycle-related factors in plant germline progression.

SPL and RBR1 are the central regulators of germline cell establishment, but other integral factors have been identified. One such factor is known as AMEIOTIC 1 (AM1) in maize and rice and as SWITCH1/DYAD in Arabidopsis (Golubovskaya et al., 1993; Mercier et al., 2001; Che et al., 2011). In rice, mutants for MICROSPORELESS 1, a CC-type glutaredoxin, are unable to produce germline cells in the anthers (Hong et al., 2012). In maize, loss of function of the MICROSPORELESS 1 homolog MSCA1 causes an analogous phenotype (Kelliher and Walbot, 2012). Moreover, the anther redox state is a known determinant of germ cell fate; ROXY1 and ROXY2, Arabidopsis CC-type glutaredoxins, play redundant roles in MMC formation (Xing and Zachgo, 2008). Abnormal redox states have previously been shown to affect germ cell initiation only in males, causing male sterility. However, it remains unknown whether redox regulation is also involved in female germline formation. In addition to the distinct regulatory mechanisms that control male and female germline formation, there is a lack of functional conservation in germline entry-related factors among species. The majority of studies related to germ cell specification have been performed in Arabidopsis and have largely focused on female germ cells. It is unclear whether information obtained from these studies can be applied to other species, especially with respect to male germ cells. Most critically, plants employ multiple intricate regulatory mechanisms to correctly induce meiotic cell fate, but the connections by which these pathways form an integrated regulatory network are unknown.

In the present study, we discovered that RBR1 may regulate the transition from mitosis to meiosis in male germ cells of rice through interactions with the cytokinin signaling pathway. Loss of RBR1 function resulted in over-proliferative sporogenous-cell-like cells (SCLs) in the anther locules. These over-proliferative SCLs were unable to initiate meiosis, eventually stagnating and degrading at the late developmental stage. These results demonstrated that RBR1 served as a molecular switch between mitosis and meiosis. We also found that cytokinin contents were significantly increased and LEPTO1 was significantly downregulated in rbr1. Characterization of the rbr1-1 lepto1 double mutant revealed that the absence of LEPTO1 exacerbated the meiosis entry defect of the rbr1 mutants. Through this genetic approach, we confirmed the correlation between germ cell over-proliferation and disturbed cytokinin signaling in rbr1. This study reveals the precise molecular mechanism underlying the transition from mitosis to meiosis. These findings greatly advance our understanding of reproductive developmental biology and demonstrate previously unknown functions of RBR1 in plants.

Results

Meiosis initiation among germ cells in rice anthers

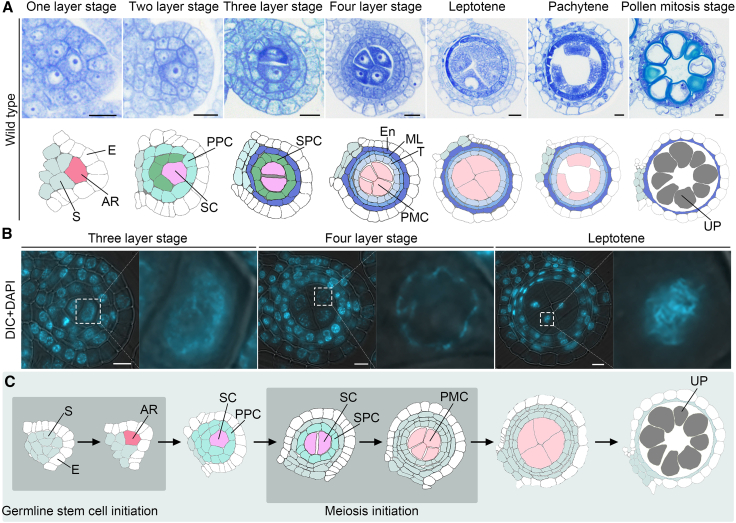

To assess the advancement of meiosis initiation in the male germ cells of rice, we observed transverse sections of anthers collected from wild-type plants. The anther primordium was quadrangular in shape, with the epidermis positioned as the outermost layer. This developmental stage was referred to as the one-layer stage. Stem cells situated at the four corners of the structure divided rapidly to form ARs, which were slightly larger than the surrounding cells. At the one-layer stage, an AR could be identified by its large nucleus and nucleolus (Figure 1A and Supplemental Figure 1A). However, the chromatin structure of most ARs resembled that of a typical mitotic interphase nucleus, with a loose, dispersed structure and an extensively non-condensed state. The process of producing ARs, a common type of reproductive stem cell, is referred to as germline stem cell initiation (Figure 1C). After one round of periclinal division, the ARs generated SCs and primary parietal cells (PPCs) (Figure 1A and Supplemental Figure 1A). The SCs were then encircled by two somatic cell layers, comprising PPCs and the epidermis; this state was termed the two-layer stage. PPCs are a type of stem cell and possess the ability to divide; following one round of periclinal division, two layers of secondary parietal cells (SPCs) were generated. At this point, the developing anther had a characteristic locule and a three-layer wall; this phase was therefore designated the three-layer stage (Figure 1A). At the two- and three-layer stages, the SCs situated in the innermost layer of the anther locule underwent multiple cycles of division, generating more SCs. These SCs still showed the typical mitotic nuclear state and chromatin structure, indicating that they had gone through mitotic cell division (Figure 1B). Following the three-layer stage, the outer layer of SPCs differentiated directly into the endothecium, whereas the inner layer of SPCs underwent periclinal cell division. This resulted in formation of the middle layer and the tapetum. The anthers now had four concentric somatic layers surrounding the SCs. From the outermost to the innermost layer, the layers were the epidermis, the endothecium, the middle layer, and the tapetum. This stage was therefore referred to as the four-layer stage (Figure 1A). Upon entering the four-layer stage, SCs terminated their stem cell fate and irreversibly differentiated into PMCs in a process that marked the transition from mitosis to meiosis, commonly known as meiosis initiation (Figure 1C). Once they entered meiosis, the centrally located PMCs displayed a chromosomal phenotype distinct from that of germline stem cells, with condensed chromatin that was hairy in appearance and formed a fuzzy outline. The four-layer stage was also referred to as pre-leptotene; PMC chromosomes formed thin threads in early leptotene, and these threads became more distinct at late leptotene (Figure 1B). Upon entering meiosis, PMCs initiated meiotic division to generate haploid gametes. During the late developmental stage of pollen maturation, the inner concentric somatic layers comprising the tapetum and the middle layer simultaneously initiated programmed cell death (Figure 1A and 1C).

Figure 1.

Meiosis initiation in male germ cells of rice.

(A) Transverse sections stained with toluidine blue (upper panel) and diagrammatic sketches (lower panel) of wild-type anthers during key developmental stages. AR, archesporial cell (red); E, epidermis (white); En, endothecium (dark blue); ML, middle layer (blue); PMC, pollen mother cell (light red); PPC, primary parietal cell (bright blue); SC, sporogenous cell (pink); SPC, secondary parietal cell (green); S, soma (dusty blue); T, tapetum (light blue); UP, unmatured pollen grain (gray). Scale bars, 5 μm.

(B) Transverse sections of wild-type anthers at key developmental stages stained with 4′,6-diamidino-phenylindole (DAPI). For each stage, the image on the right shows chromosome morphology in an enlarged view of the region outlined in white in the image on the left. Scale bars, 5 μm.

(C) Diagram showing the process of germline stem cell and meiosis initiation in male germ cells of rice. AR, archesporial cell (red); E, epidermis (white); PMC, pollen mother cell (light red); PPC, primary parietal cell (bright blue); SC, sporogenous cell (pink); SPC, secondary parietal cell (bright blue); S, soma (dusty blue); UP, unmatured pollen grain (gray).

Cytological characterization of the mei1 mutant

To gain insights into the molecular basis of meiosis initiation in rice, we performed a screen of microsporocyte-less mutants. The screened plants were derived from the progeny of mutants generated by 60Co γ-irradiation. One mutant that displayed complete sterility was selected for further study and named meiosis initiation 1 (mei1) (Figure 2A). mei1 plants were characterized by small, light-yellow anthers, and I2-KI staining confirmed the absence of pollen grains (Figure 2B–2D). Pollination of mei1 mutants with wild-type pollen failed to produce any seeds, indicating that the mei1 mutation had effects on both male and female fertility. There were no other substantial morphological differences between mei1 mutants and wild-type plants at maturity (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Characterization of the mei1 mutant and map-based cloning of the candidate gene.

(A–D) Phenotypic analysis of the mei1 mutant. (A) Similar vegetative growth of a representative wild-type and mei1 mutant plant. (B–D) Representative images of wild-type and mei1 anthers. mei1 mutants had small, light-yellow anthers with no pollen grains, as confirmed by I2-KI staining. Scale bars, 0.5 mm.

(E–K) Transverse sections of mei1 anthers at key developmental stages stained with toluidine blue. Anthers were collected at the (E) three-layer, (F) four-layer, (G–I) meiosis, and (J and K) pollen mitosis stages. Scale bars, 5 μm.

(L–O) Transverse sections of mei1 anthers at key developmental stages stained with DAPI. Anthers were collected at the (L) three-layer, (M) four-layer, and (N) early meiosis stages. (O) Magnified view of the regions outlined in white in (M), showing chromosome morphology in a representative somatic cell (upper) and sporogenous-cell-like cell (SCL) (lower). Scale bars, 5 μm.

(P) Relative quantification of divided cells per sac in wild-type and mei1 anthers at key developmental stages. Two-tailed Student’s t-tests. Data are shown as the mean ± standard deviation.

(Q) Diagrams showing mei1 anthers at key developmental stages. E, epidermis (white); En, endothecium (dark blue); ML, middle layer (blue); GCL, germ-cell-like cell (wine); SPC, secondary parietal cell (green); S, soma (dusty blue); T, tapetum (light blue).

(R) Linkage and physical maps showing the location of mei1. Genes within the target region are shown in red (the candidate gene) and green (other known genes). Rec, number of recombinant plants at the indicated locus.

To establish the precise point at which the mutant phenotype was first detectable and to identify affected cell types, we analyzed transverse sections of anthers collected from mei1 mutants. At the one- and two-layer stages, there were no noticeable discrepancies between the mei1 and wild-type anthers; both featured regular parietal cells and well-formed germline stem cells, including ARs and SCs (Supplemental Figure 1A). However, at the three-layer stage, there were distinct differences between mei1 and wild-type anthers. The mei1 anthers had the typical three somatic cell layers, but there were noticeably more germ-cell-like cells (GCLs) in each mei1 anther locule than in the wild-type anther locule (Figure 2E and 2Q). Specifically, there were an average of two germ cells per section in wild-type anthers at the three-layer stage, whereas mei1 anthers had an average of four GCLs per transverse locule section (Supplemental Figure 1B).

To gain insights into the cause of the excessive GCLs in mei1 anther locules, we observed GCL chromosome morphology in transverse sections of mei1 anthers stained with 4′,6-diamidino-phenylindole (DAPI). At the three-layer stage, ∼3.5% (n = 895) of germ cells in wild-type anther locules were in the mitotic phase, whereas ∼6.1% (n = 962) of GCLs were dividing in mei1 mutants (Figure 2L and 2P). This suggested that mei1 mutant GCLs had an enhanced cell-division capacity compared with GCLs in the wild type, resulting in an increased number of GCLs in the anther locule.

As development progressed, the observed structure of the four somatic cell layers formed and the SCs terminated the germ stem cell fate, differentiating into PMCs and initiating meiosis. At the four-layer stage, there were generally four PMCs per section in wild-type anthers, whereas mei1 anthers had an average of nine GCLs in the locule (Figure 2F, 2Q, and Supplemental Figure 1B). Because germ cell development is closely associated with somatic cell layer establishment, the number of somatic cell layers can indicate the developmental stage of the inner germ cells. When the four-layer stage was reached, the SCs generally irreversibly differentiated into PMCs. Chromosome morphology was distinct in PMCs compared with SCs, with a more condensed conformation (Figure 1B). However, a large proportion of GCLs (∼4.8%, n = 2024) were still in the mitotic division phase in the mei1 anther locules, suggesting that these cells still had stem cell properties and had not yet initiated meiosis (Figure 2M, 2O, and 2P). In addition, the more abundant GCLs observed in mei1 anthers were substantially smaller than the PMCs in wild-type anthers. After entering meiosis, the inner-located germ cells (the PMCs) grew significantly larger, and the chromosomes of wild-type cells formed thin thread-like structures during leptotene (Figure 1B). However, the GCLs in mei1 anther locules appeared to be arrested at the pre-meiosis stage, with chromosome morphology similar to that of mitotic interphase cells (Figure 2G, 2N, and 2Q). At this stage, there were an average of 11 GCLs per section in mei1 anther locules (Supplemental Figure 1B). The abundant GCLs in mei1 were then degraded during the late stages of anther development, at which time the swollen tapetal cells also degraded and disappeared. Eventually, mei1 anther locules shrank and became filled with cell debris; they were then enveloped by an intact layer of the epidermis and the somatic cells beneath it, forming anthers without pollen grains (Figures 2H–2K and 2Q).

MEI1 isolation

To identify the molecular functions underlying the mei1 mutant phenotypes, we performed a genetic analysis, which revealed that the mei1 phenotype was determined by a single recessive gene; one-fourth of the F2 progeny exhibited sterility. To identify the causative gene, we performed map-based cloning to isolate the MEI1 locus. Heterozygous mei1 mutants in the Oryza sativa subsp. indica cv. Zhongxian 3037 background were crossed with O. sativa subsp. japonica cv. Yandao 8. Sequences of the japonica cultivar Nipponbare and the indica cultivar Minghui 63 were compared to identify polymorphic loci and develop insertion/deletion mutation (indel) markers. The resulting markers were distributed across all 12 rice chromosomes. The corresponding regions were amplified for sequencing from the two parental lines and 22 homozygous recessive individuals in the F2 population. The results indicated that two indel markers, M1 and M2 (both located on the long arm of chromosome 8), were linked to the target gene, which was mapped to a 2.5-Mb region (Figure 2R). The same two indel markers were used to survey 574 sterile individuals from the F2–F6 populations, revealing 21 and 20 recombinants at M1 and M2, respectively. To fine map MEI1, we developed four additional indel markers (M3–M6) in the 2.4-Mb region, which narrowed the location of the target gene to a 63-kb interval between M5 and M6. The Rice Genome Annotation Project (http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu/) showed 10 predicted genes in this region. LOC_Os08g42600 was selected for further investigation on the basis of its high similarity to AtRBR1 (Figure 2R) (Ebel et al., 2004). Sequencing analysis identified a 2-bp deletion (GT) in the sixth exon of OsRBR1, resulting in a frame shift and formation of a premature termination codon at amino acid position 168 (Supplemental Figure 2A and 2B). Subsequently, RBR1 was amplified from 30 plants in the F2 population, both fertile and sterile, and the 2-bp deletion was found to co-segregate with sterile individuals. RBR1 was therefore classified as a candidate causative gene for the mei1 phenotype; the rice mei1 mutant was preliminarily designated rbr1-1 in further analyses.

Primers specific for the full-length RBR1 sequence were designed on the basis of data in the Rice Genome Annotation Project database. Both the full-length RBR1 genomic region and the corresponding coding sequence were amplified from wild-type panicles collected from the Zhongxian 3037 background. Gene structure analysis showed 18 exons and 17 introns in an open reading frame of 3036 nucleotides that encoded a protein of 1011 amino acids (Supplemental Figure 2A and 2B and Figure 3A).

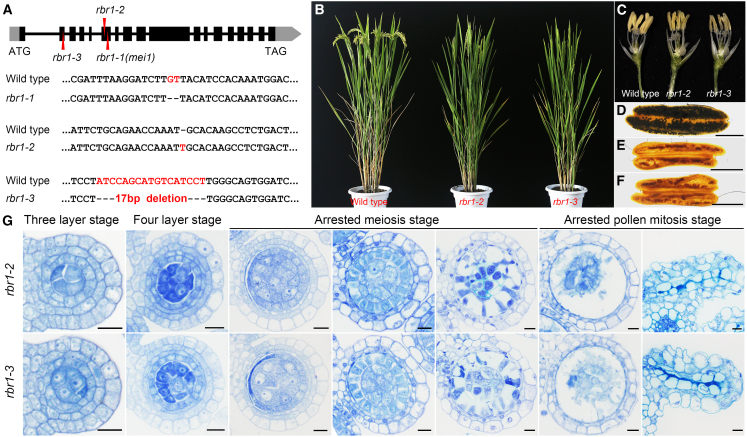

Figure 3.

RBR1 is responsible for the transition from mitosis to meiosis in rice.

(A) RBR1 gene structure and mutant sequences. Exons are represented by black boxes, introns by black lines, and untranslated regions (UTRs) by gray boxes. The mutated sites in select alleles are indicated with red arrowheads.

(B–F) Phenotypic analysis of rbr1-2 and rbr1-3 mutants. (B) Representative wild-type, rbr1-2, and rbr1-3 plants showing similar vegetative growth. (C–F) Representative images of wild-type, rbr1-2, and rbr1-3 anthers. The mutants exhibited small, light-yellow anthers with no pollen grains, as verified by I2-KI staining. Scale bars, 0.5 mm.

(G) Transverse sections of rbr1 anthers at key developmental stages stained with toluidine blue. Scale bars, 5 μm.

RBR1 is responsible for the transition from mitosis to meiosis in germline stem cells

To confirm that defects in meiosis initiation were caused by the RBR1 mutation, we used CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing to obtain two new RBR1 alleles, rbr1-2 and rbr1-3, in the Yandao 8 background. rbr1-2 had a 1-bp insertion in exon 6, resulting in a frame shift and a premature stop codon. rbr1-3 had a 17-bp deletion in exon 2, which also led to a frame shift and a premature stop codon (Figure 3A and Supplemental Figure 2A, 2C, and 2D). Phenotypic analyses showed no discernible differences between wild-type plants and rbr1-2 or rbr1-3 mutants during vegetative growth (Figure 3B). However, I2-KI staining revealed that the spikelets of both mutants contained small, light-yellow anthers with no pollen grains (Figure 3C–3F).

Observation of transverse sections of rbr1-1, rbr1-2, and rbr1-3 anthers revealed identical phenotypes. Defects were first detectable in the mutants at the three-layer stage, with hyper-proliferative GCLs prominent in the anther locules. The number of GCLs dramatically increased at the four-layer stage, with an average of nine cells per section. In addition, GCLs in the mutant anther locules were much smaller than PMCs were in wild-type plants during this stage. Subsequently, the mutant GCLs were unable to enter meiosis, causing swelling of the surrounding tapetal cells at the late developmental stage. Ultimately, the inner GCLs and the outer defective tapetal cells both decayed and vanished during the later stages of anther development, resulting in pollen-free anthers (Figure 3G).

We next performed an allelism test for rbr1-1 and rbr1-3. F1 plants exhibited normal vegetative growth but were completely sterile (Supplemental Figure 3A). Observation of the microsporangia revealed that all spikelets from F1 sterile plants contained small, light-yellow anthers (Supplemental Figure 3B). Examination of transverse sections of anthers from F1 sterile plants revealed the characteristic rbr1 mutant phenotype: an overabundance of GCLs in the anther locules during the early developmental stage, defective tapetal cells during the late developmental stage, and no pollen grains (Supplemental Figure 3C–3G). Collectively, these findings strongly support the conclusion that the absence of RBR1 is responsible for the defective phenotype of the mei1 mutant. Thus, these data clearly demonstrate that RBR1 is the gene that triggers the transition from mitosis to meiosis in rice.

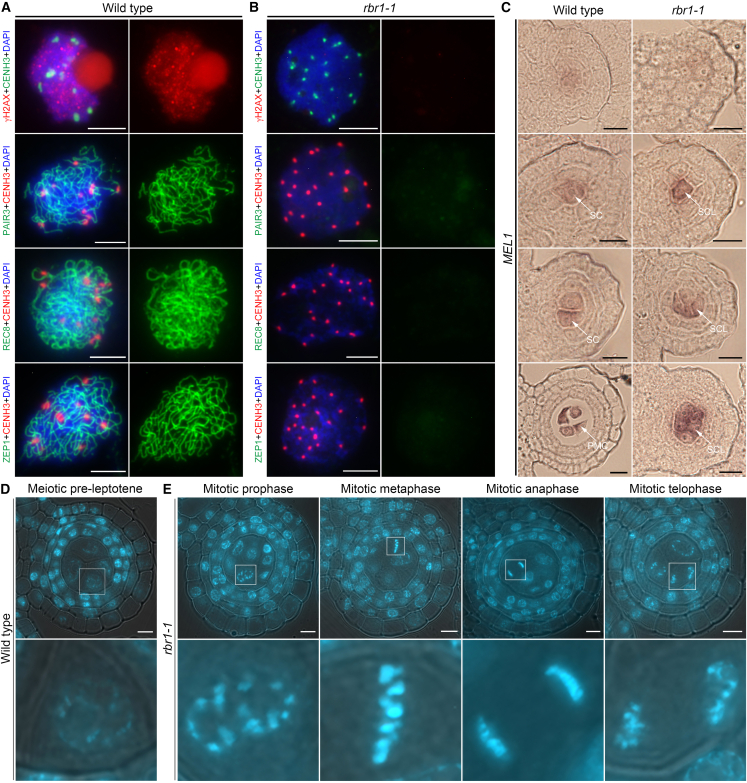

Meiosis entry was completely blocked in GCLs of rbr1 mutants

The cytological observations to this point led us to a hypothesis: the excessive number of GCLs in the anther locules of rbr1 mutants had been impeded from initiating meiosis. To verify this hypothesis, we closely observed the locations of meiosis-specific proteins in the nuclei of rbr1 mutants. To select anthers at the meiosis stage, we used spikelet length as a reference standard and performed dual immunolocalization experiments. CENH3, a histone H3 variant, displays a stronger signal in germline cells than in somatic cells and was therefore used to identify germ cells (Ren et al., 2018). Loading of γH2AX, a phosphorylated form of the histone variant H2AX that marks the sites of meiotic double-stranded breaks (DSBs) (Miao et al., 2021), was completely blocked in rbr1 mutants, demonstrating a lack of meiotic DSB formation. Furthermore, the axial element PAIR3, the meiosis-specific cohesion subunit REC8, and the central element of the synaptonemal complex ZEP1 in rice meiosis were absent from the chromosomes of rbr1 GCLs (Figure 4B) (Wang et al., 2010, 2011; Shao et al., 2011). This indicated that homologous recombination and synaptonemal complex formation were impaired in rbr1 mutants. By contrast, these meiosis-specific proteins were observed on the chromosomes of meiotic-stage germ cells in wild-type plants (Figure 4A). These data led us to conclude that key events in meiotic prophase I progression were not initiated in the absence of RBR1.

Figure 4.

Germ cells in rbr1 were arrested at the sporogenous cell stage.

(A) Dual immunolocalization of CENH3 and meiosis-specific proteins in wild-type germ cells. Chromosomes were stained with DAPI (blue). Left, merged signals. Right, signals from meiosis-specific proteins only. Scale bars, 5 μm.

(B) Dual immunolocalization of CENH3 and meiosis-specific proteins in rbr1-1 mutant germ cells. Chromosomes were stained with DAPI (blue). Left, merged signals. Right, signals from meiosis-specific proteins. Scale bars, 5 μm.

(C) In situ hybridization to detect MEL1 mRNA in wild-type and rbr1-1 mutant anthers. PMC, pollen mother cell; SC, sporogenous cell; SCL, sporogenous-cell-like cell. Scale bars, 5 μm.

(D) Transverse sections of wild-type anthers at the four-layer stage stained with DAPI. Regions outlined in white in the upper panels indicate individual germ cells located in the anther locule, which are shown enlarged in the lower panels. Scale bars, 5 μm.

(E) Transverse sections of rbr1-1 anthers at the four-layer stage stained with DAPI. Regions outlined in white in the upper panels indicate individual GCLs located in the anther locule, which are shown enlarged in the lower panels. Scale bars, 5 μm.

An important aspect of meiosis initiation is callose deposition in meiosis-stage anther locules. During this process, callose contributes to separation of PMCs from one another (Ren et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2018; Somashekar et al., 2023). To determine whether this process proceeded normally in rbr1 mutants, we examined transverse sections of anthers stained with aniline blue. In wild-type anthers, callose signals surrounding the PMCs became prominent at leptotene. A circle of callose was then present around the periphery of each individual PMC at pachytene. At the tetrad stage, the callose plate developed a cross wall between the four daughter cells, aiding their separation from one another. By contrast, no callose deposition was observed at any stage in rbr1 GCLs, which mirrored the conditions of the neighboring somatic cells (Supplemental Figure 4A). Even at the very late developmental stage when similarly sized spikelets in wild-type plants had already generated isolated microspores and deposited callose on the cell plate, GCLs in rbr1 anther locules showed no callose deposition (Supplemental Figure 4B). This failure to deposit callose in rbr1 GCLs suggested that meiosis initiation was blocked. Differential expression of callose metabolism-related genes in the wild type and rbr1 mutant revealed a significant reduction in expression of the callose synthesis-related gene GSL5 in the rbr1 mutant (Supplemental Figure 5). Essential for callose metabolism during meiosis, GSL5 is crucial for promoting anther callose deposition and maintaining meiosis initiation and progression (Somashekar et al., 2023). The reduced expression of GSL5 is associated with abnormal callose accumulation in the rbr1 mutant, providing additional evidence of disrupted callose metabolism in this mutant.

We next closely monitored chromosome behavior in rbr1 GCLs at the four-layer stage. Development of the somatic anther wall layer is highly correlated with germ cell maturation, and the four-layer stage is typically considered to signify the beginning of meiosis in germ cells. In wild-type plants, chromosome morphology of germ cells was distinct from that of the neighboring somatic cells, characterized by a more condensed structure at the four-layer stage (Figure 4D). By contrast, chromosome morphology was similar between centrally located GCLs of rbr1 microsporangia and the surrounding somatic cells, and no meiotic chromosome structure was observed at the four-layer stage. In addition, we noticed a great number of cells in the mitosis division stage, indicating that GCLs in the rbr1 anther locules had retained the mitotic stem cell fate and had not yet initiated meiosis (Figure 4E). On the basis of several factors (namely absence of meiosis-specific proteins, failure to deposit callose, and irregularity of the cell-division pattern), we concluded that meiosis initiation was completely blocked in rbr1 mutant GCLs.

rbr1 GCLs were arrested at the SC stage

As discussed above, rbr1 anther locules contained hyper-proliferative GCLs that maintained mitotic stem cell properties (e.g., continuous mitotic cell division). Somatic stem cells (PPCs and SPCs) and germline stem cells (ARs and SCs) both possessed this property in anthers. Thus, it was difficult to distinguish whether GCLs in rbr1 mutants were somatic stem cells or germline stem cells.

To address this issue, RNA in situ hybridization was used to assess MEL1 expression in rbr1 anthers. MEL1 signals are confined to germ cells from the two-layer stage to the early four-layer stage in rice, and MEL1 is therefore commonly employed as a germ cell marker (Hong et al., 2012; Ren et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2018). The MEL1 mRNA signal initially emerged in PSCs, then grew very strong in the SCs of wild-type anthers. The signal remained strong in early PMCs, then vanished until meiotic recombination began (Figure 4C and Supplemental Figure 6). Interestingly, MEL1 mRNA was also detectable in rbr1 anthers at the two-layer stage, and it was expressed at similar levels in rbr1 and wild-type anthers. At the three-layer stage, MEL1 was more highly expressed in the anther locules of rbr1 plants than wild-type plants. During this stage, wild-type anthers generally showed MEL1 labeling of only two SCs per section, compared with four or more germ cells in rbr1 mutants. MEL1 expression in GCLs increased dramatically in rbr1 mutants at the four-layer stage, at which point expression peaked; a minimum of nine GCLs per section expressed high levels of MEL1 (Figure 4C and Supplemental Figure 6), whereas there were usually four MEL1-labeled PMCs per section in wild-type plants. These findings directly demonstrated that the hyper-proliferative cells present in rbr1 anther locules were not somatic stem cells, but rather germline stem cells, likely SCs. Thus, the loss of RBR1 function caused germ cells in the anther locules to be arrested at the SC stage, causing a pattern of continuous mitotic cell division that resulted in hyper-proliferative germ cell formation and hindered meiosis initiation. These data therefore confirm that RBR1 was a vital element in the transition from mitosis to meiosis. Because germline stem cells in rbr1 were arrested at the SC stage, the hyper-proliferative GCLs in rbr1 anther locules are referred to as SCLs in further analyses.

RBR1 expression patterns and RBR1 subcellular localization

To better understand the molecular biological function of RBR1 in meiosis entry, we analyzed RBR1 expression patterns by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT–qPCR) and RNA in situ hybridization. RT–qPCR results demonstrated that RBR1 was expressed in all parts of the plant, particularly in young panicles, with a widespread presence in roots, stems, leaves, and sheaths (Supplemental Figure 7A). RNA in situ hybridization in wild-type anthers revealed that RBR1 mRNA was barely detectable at the one-layer stage and was first visible in SCs at the two-layer stage. RBR1 mRNA accumulation peaked at the three-layer stage, with expression predominantly in SCs and SPCs. The RBR1 signal was still detectable in PMCs and tapetum cells at the early four-layer stage, but expression had decreased and was below the detection threshold in all tissues during the late meiosis stage. No signal was observed when the sense probe was used in anther sections (Supplemental Figure 7B). The temporal limitation of RBR1 mRNA accumulation in germ cells to the three- and four-layer stages supported the idea that RBR1 functions at the specific time when germ cells transition from mitosis to meiosis. Moreover, a high concentration of RBR1 mRNA in the innermost somatic layer implied that RBR1 may play a significant role in anther wall development.

A BLASTP search of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database showed that RBR1 has substantial amino acid sequence similarity with Rb-related proteins from multiple species. SMART analysis demonstrated that RBR1 was composed of four conserved domains: an N-terminal domain; two pocket domains, RbP A and RbP B; and a C-terminal domain (Supplemental Figure 7D). Notably, the pocket domains were highly conserved across multiple plant species (Supplemental Figure 7E). As a major regulator of the cell cycle in mammals and plants, RBR1 plays pivotal roles in cell proliferation, differentiation, endoreplication, and stem cell biology. These functions are accomplished primarily through interactions with various transcription factors, including those in the E2F family and CDK/cyclin complexes (Desvoyes and Gutierrez, 2020; Polyn et al., 2015; van den Heuvel and Dyson, 2008).

To investigate whether RBR1 was present and functional in the rice nucleus, a transient expression assay was performed in rice protoplasts using an RBR1–GFP fusion protein. The results revealed that the green fluorescence signal of RBR1–GFP coincided with the red fluorescence signal of the OsMADS3–mCherry fusion protein, which was used as a nuclear localization marker (Supplemental Figure 7C) (Ren et al., 2018). This implied that OsRBR1 functioned in the same way as Rb proteins in other species, as typical nuclear-localized proteins. Given the high amino acid sequence conservation and the consistencies in subcellular localization, it appeared likely that OsRBR1 had the same molecular biological roles in rice as previously characterized homologs have in other model plant species.

Eliminating WUS function did not restore meiosis entry in rbr1 mutants

Studies in Arabidopsis have demonstrated that homozygous temperature-sensitive rbr1 mutants (Atrbr1-2) have more meiocytes in both their female and male reproductive organs compared with wild-type plants. Notably, Atrbr1-2 shows hyper-proliferative germ cells in the anther locule and is nearly indistinguishable from the rice rbr1 mutant phenotype. On the basis of similarity in anther phenotypes between rice and Arabidopsis rbr1 mutants, we postulated that the homologs used similar molecular regulatory mechanisms to control meiosis entry. Previous research in Arabidopsis has demonstrated that RBR1 is a direct suppressor of the stem cell factor WUS. WUS depletion in Atrbr1 mutants results in restoration of a typical meiocyte number in the ovules (Zhao et al., 2017). Consequently, if the molecular regulatory mechanisms in rice are comparable to those in Arabidopsis, WUS deletion would be expected to restore normal PMC numbers in each anther locule of rbr1 mutants.

To test this hypothesis, we constructed a rice rbr1-1 wus double mutant. The single wus mutant showed a typical monoculm plant architecture and abnormal panicle development (Supplemental Figure 8A and 8B) (Lu et al., 2015). Analysis of wus mutant spikelets showed that 43% were compromised, exhibiting empty stalks in the panicle; 15% had morphological defects such as partial glumes or a lack of anthers or stigmas; and 42% had normal morphology, with the typical two stigmas, six anthers, and integral glumes (Supplemental Figure 8C). I2-KI staining demonstrated that the pollen grains in the anthers of normal spikelets were viable, indicating that WUS was not essential for male germ cell development in correctly formed spikelets (Supplemental Figure 8D and 8E). The rbr1-1 wus double mutant displayed monoculm architecture with severely defective panicle development, identical to the wus single mutant (Figure 5A). However, contrary to our expectations, the double mutant did not show restoration of four PMCs per section in the anthers. The rbr1-1 wus mutant had hyper-proliferative SCLs in the anther locule and failed to produce pollen grains during the later stages of anther development (Figure 5B and 5C). The double-mutant phenotype was similar to that of the rbr1-1 single mutant, suggesting that the loss of WUS function did not restore meiosis entry in rice rbr1 mutants. To assess the potential dose effect of WUS in rice, we investigated the development of male germ cells in transverse sections of rbr1-1−/− wus+/− anthers. Our observations indicated that the phenotype of the rbr1-1−/− wus+/− mutants is indistinguishable from that of the rbr1-1 single mutants. In the rbr1-1−/− wus+/− mutants, initial defects were observed at the three-layer stage, characterized by hyper-proliferative SCLs in the anther locules. During the four-layer stage, there was a significant increase in the number of SCLs, averaging nine cells per section. This was followed by the mutant SCLs showing an inability to undergo meiosis, resulting in the swelling of the surrounding tapetal cells during the later stages of development (Supplemental Figure 9A). Statistical analysis showed no significant difference in the number of SCLs in the anther locules between rbr1-1−/− wus+/− and rbr1-1 single mutants at the four-layer stage (Supplemental Figure 9B). The results above indicate that the partial absence of WUS in rice rbr1-1 mutants does not demonstrate a dose-effect phenomenon, as observed in Arabidopsis.

Figure 5.

Cytokinin homeostasis and signaling pathway homeostasis were disrupted in rbr1 mutants.

(A–C) Phenotypic analysis of wus and rbr1-1 wus plants. (A) Both wus and rbr1-1 wus plants had monoculm architecture and unusual panicle development. (B) In contrast to the wild type and the wus mutants, rbr1 and rbr1-1 wus mutants exhibited small, light-yellow anthers with no pollen grains, as verified by I2-KI staining. Scale bars, 0.5 mm. (C) Transverse sections of wus and rbr1-1 wus anthers at key developmental stages stained with toluidine blue. Scale bars, 5 μm.

(D and E) Quantification of endogenous cytokinin contents in young, tender spikelets from wild-type and rbr1-1 plants. ∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p ≤ 0.01 (Student’s t-test). Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of five biological replicates. tZR, trans-zeatin riboside; cZR, cis-zeatin riboside; iP, isopentenyladenine; iPR, isopentenyladenine riboside; cZ, cis-zeatin; tZ, trans-zeatin; DZ, dihydrozeatin; DZ7G, dihydrozeatin 7-glucoside; DZ9G, dihydrozeatin 9-glucoside; iP7G, N6-isopentenyladenine-7-glucoside; tZROG, trans-zeatin riboside O-glucoside; tZOG, trans-zeatin O-glucoside; tZ7G, trans-zeatin 7-glucoside; tZ9G, trans-zeatin 9-glucoside; DZOG, dihydrozeatin O-glucoside; iP9G, N6-isopentenyladenine-9-glucoside; DZROG, dihydrozeatin riboside O-glucoside.

(F) Analysis of cytokinin type-B response factor expression in young, tender spikelets from wild-type and rbr1-1 plants. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation.

Ovule development in the rbr1 mutant differed from that in Atrbr1-2 mutants

Given the absence of functional conservation between male and female germline formation and the marked differences in the processes that regulate meiosis initiation among species, it was unsurprising that WUS did not restore meiosis entry in rice rbr1 mutants. Moreover, we noticed that ovule development differed between rice rbr1 mutants and Atrbr1-2 mutants.

In Atrbr1-2, additional MMCs were present and could initiate meiosis, leading to multiple embryo sacs per seed. However, in the ovules of Osrbr1 mutants, no embryo sac structure was observed at any point during reproductive development. In wild-type rice plants, a diploid AR was selected from a population of subepidermal cells. The AR then expanded and formed the MMC to initiate meiosis in the female reproductive organ. Subsequently, the germ cell (MMC) switched the mode of cell division from mitosis to meiosis. At the megasporocyte meiosis stage, the MMC divided meiotically to produce four haploid progeny in a linear arrangement. Of the four progeny cells, only the one located near the chalazal end developed into a functional megaspore, whereas the other three (nearer the micropylar end) degraded. After the functional megaspore was elongated and enlarged, it initiated three rounds of mitotic division, forming an eight-nucleate embryo sac. During embryo sac development, nuclei migrated and underwent cellularization, leading to formation of a mature embryo sac containing an egg cell, two polar nuclei, two synergids, and three antipodals (Supplemental Figure 10).

In contrast to wild-type rice, in which an MMC with a large nucleus and nucleoli was easily distinguishable from the surrounding somatic cells, the rbr1-1 mutant did not display MMC formation. During the early stage of ovule development, all cells in the megasporangium exhibited a homogeneous appearance, characterized by small cells and mitotic interphase nucleus structures. In contrast to wild-type plants, rbr1-1 mutants did not produce an embryo sac. In the megasporangium of rbr1-1 mutants, an imprint of cell debris (approximately the width of one cell and half the length of the major axis of the ovule), was observed in place of a fully formed embryo sac (Supplemental Figure 10). The ovule phenotype of rbr1 mutants, which lacked any reproductive cell structures, resulted in the observed complete female infertility.

Cytokinin signaling homeostasis was disturbed in rbr1 mutants

To gain further insights into the regulatory mechanisms by which RBR1 controlled rice meiosis initiation, we further analyzed the phenotypic characteristics of the rbr1 mutants. We hypothesized that RBR1 was involved in mitotic cell division because the typical phenotype of rbr1 anthers (hyper-proliferative germ cells) demonstrated a high level of mitotic cell division potential.

Phytohormones, particularly cytokinin, play key roles in plant mitotic cell division. We therefore evaluated the roles of the cytokinin signaling pathway in controlling germ cell initiation. Numerous studies have demonstrated that the cytokinin signaling pathway is critical to reproductive development (Ashikari et al., 2005; Terceros et al., 2020). To ascertain the role of cytokinin in meiosis entry of rice male germ cells, we used ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC)–tandem mass spectrometry to measure the cytokinin content in spikelets at the meiosis initiation stage (spikelets ≤ 1.5 mm) in wild-type and rbr1-1 mutant plants. Surprisingly, the majority of measured cytokinins (tZR, cZR, iP, iPR, cZ, tZ, DHZ, DZ7G, DZ9G, iP7G, tZROG, tZOG, tZ9G, DZOG, IP9G, and DZROG) were present at significantly higher levels in rbr1-1 than in wild-type spikelets. Notably, the active cytokinin forms (e.g., iP, cZ, and tZ) were significantly more abundant in rbr1-1 than in wild-type spikelets (by 3.1-, 3.0-, and 3.2-fold, respectively) (Figure 5D and 5E). The strong correlation between cell proliferation and cytokinin levels in plants suggested that the high cytokinin levels in rbr1 mutants could be the primary cause of hyper-proliferative SCL formation.

The cytokinin signaling pathway is a classical signal transduction system, involving several main steps: cytokinin biosynthesis, perception by receptors, transfer of a phosphoryl group by histidine phosphotransferases, and responses by two classes of response regulators (RRs). Type-A RRs are involved in negative feedback loops, whereas type-B RRs (ORRs) act as positive transcriptional regulators (Terceros et al., 2020). Because of the much higher levels of endogenous cytokinins in rbr1-1 mutant compared with wild-type spikelets, we investigated expression levels of type-A RRs and type-B ORRs in anthers during the meiotic initiation stage to determine whether cytokinin signaling was altered in the rbr1-1 mutants. Of the type-A RRs, RR1, RR2, RR6, and RR11 were significantly upregulated, whereas RR3, RR4, RR5, and RR7 were significantly downregulated in rbr1-1 (Supplemental Figure 11). This implied that each of the type-A RRs had a unique response to the increased cytokinin content. Interestingly, all six of the examined ORRs were substantially downregulated in rbr1-1 mutants. ORR4 (also known as LEPTO1) has an important role in initiating meiosis. When LEPTO1 function is impaired, the number of PMCs increases slightly and meiotic progress is severely impeded, ultimately leading to the production of anthers without pollen (Figure 5F) (Zhao et al., 2018). Given the highly similar phenotypes of lepto1 and rbr1 mutants and the significant downregulation of LEPTO1 in rbr1 anthers, we hypothesized that LEPTO1 may function downstream of RBR1. Downregulation of LEPTO1 could therefore be the origin of the meiosis entry defect observed in rbr1.

RBR1 regulated meiosis initiation by mediating the cytokinin signaling pathway

To test the hypothesis that RBR1 operates upstream of LEPTO1, we generated an rbr1-1 lepto1 double mutant. Transverse sectioning and staining were performed to observe anther development in lepto1 and rbr1-1 lepto1. At the three-layer stage, there were comparable numbers of SCs in lepto1 and wild-type anther locules, with two SCs typically present in both. However, at the four-layer stage, there was a slight increase in the number of germ cells in lepto1, with an average of five germ cells per section (Supplemental Figure 12A and Figure 6B). Examination of transverse sections stained with DAPI at the four-layer stage showed more condensed chromosomes (with a hairy appearance and fuzzy outlines) in lepto1 mutants than in rbr1 cells, indicating meiosis initiation. As development progressed, PMCs in lepto1 anther locules, which were slightly more abundant than in wild-type anthers, halted at the pre-leptotene stage and were unable to complete meiosis. Tapetal cells in lepto1 were markedly enlarged owing to the disruption of meiosis in PMCs, which ultimately led to tapetal cell degradation and disappearance. PMCs in lepto1 also subsequently degraded and vanished, resulting in formation of anthers without pollen grains (Supplemental Figure 12B and Figure 6B) (Zhao et al., 2018). Transverse sections of rbr1-1 lepto1 double-mutant anthers showed phenotypes similar to those of rbr-1 anthers, with hyper-proliferative SCLs in the center at the three-layer stage. Unexpectedly, there were more SCLs in rbr1-1 lepto1 than in rbr1-1 anthers (Figure 6A and 6B). At the four-layer stage, rbr1-1 lepto1 typically formed four layers of somatic anther walls, and the number of SCLs continued to grow, usually reaching 14 per section. After the four-layer stage, the hyper-proliferative SCLs in the rbr1-1 single mutant appeared to have lost their excessive cell-division capacities, usually leading to a maximum of 11 SCLs per anther section (Supplemental Figure 1 and Figure 1G and 1H). By contrast, rbr1-1 lepto1 double mutants maintained the excessive cell-division ability; this mutant averaged 26 SCLs per anther section, ∼2.4 times the number of SCLs in rbr1-1 (Figure 6A and 6B). Phenotypes of germ cell nuclei were examined in DAPI-stained transverse sections of rbr1-1 lepto1 anthers. This analysis revealed that the chromosome morphology was identical between the majority of over-proliferative SCLs and the corresponding cells in rbr1-1 single mutants, indicating that SCLs in rbr1-1 lepto1 mutants could not initiate meiosis (Supplemental Figure 12B). Our observations thus revealed that germ cells in rbr1-1 lepto1 mutants had SCL phenotypes comparable to those of rbr1-1 single mutants, confirming our hypothesis that RBR1 was positioned upstream of LEPTO1 in the control of meiosis initiation.

Figure 6.

Loss of LEPTO1 function greatly exacerbated defects in rbr1 mutants.

(A) Transverse sections of lepto1 rbr1-1 double-mutant anthers at key developmental stages stained with toluidine blue. Scale bars, 5 μm.

(B) Quantification of germ cells per section in lepto1, rbr1-1, and lepto1 rbr1-1 anther locules. There were significant differences between lepto1 rbr1-1 and lepto1 and between lepto1 rbr1-1 and rbr1-1 mutants. Two-tailed Student’s t-test. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation.

(C) Transverse sections of wild-type, rbr1-1, lepto1, and lepto1 rbr1-1 anthers after the four-layer stage stained with toluidine blue. The somatic cell layers are shaded in light red, with an enlarged view of the shaded area shown at right. 1, epidermal anther wall (dark blue); 2, endothecium (blue); 3, middle layer (dark green); 4, tapetum (green); 5, extra cell layer in lepto1 rbr1-1 mutants (yellow). Scale bars, 5 μm.

To understand the molecular basis of excessive SCL proliferation in rbr1-1 lepto1 mutants, we closely monitored germ cell division in the anther locules. Approximately 9.6% (n = 927) of SCLs in the rbr1-1 lepto1 mutants were in the mitotic division phase, whereas only an average of 6.1% (n = 891) and 4.3% (n = 962) of germ cells were in the division phase in rbr1-1 and lepto1 mutants, respectively, at the three-layer stage. At the four-layer stage, the percentage of dividing cells was ∼4.8% (n = 1563) in rbr1-1 mutants, but it was much lower in lepto1 mutants (0.3%, n = 924). Approximately 6.2% (n = 2125) of cells were in the mitotic division stage in rbr1-1 lepto1 double mutants. In addition, 1.3% (n = 2544) of SCLs in rbr1-1 lepto1 mutants were still capable of undergoing mitotic division after the four-layer stage, whereas none of the SCLs in rbr1-1 were capable of performing mitosis at the same stage (Supplemental Figure 12C). These findings clearly demonstrated that the loss of LEPTO1 function substantially improved the cell-division capacity of SCLs in rbr1-1 mutants, leading to a dramatic increase in the number of SCLs in rbr1-1 lepto1 double mutants. Hyper-proliferative SCLs in rbr1-1 lepto1 double mutants were also unable to initiate meiosis, leading to their degradation and the formation of pollen-free anthers.

In addition to the serious disruption of germ cell maturation, rbr1-1 lepto1 double mutants also showed irregular anther wall development. Upon entry into the four-layer stage, the somatic cell layers of the anther generally lose their stem cell identities and develop into four distinct layers. From the outermost to the innermost layer, these are the epidermis, the endothecium, the middle layer, and the tapetum. This phenomenon was observed in wild-type, rbr1-1, and lepto1 plants. Interestingly, rbr1-1 lepto1 double mutant showed unusual five-layered anther walls. From the outermost to the innermost layer, these were designated the epidermis, the endothecium, the middle layer, the middle-layer-like layer, and the tapetum-like layer (Figure 6C). Detailed analysis of the processes involved in anther wall formation indicated that the fifth anther wall layer developed through an additional periclinal division of the innermost anther wall layer at the four-layer stage. In wild-type plants, after the four-layered anther wall has formed, the innermost anther wall layer loses its stem cell fate and differentiates to become the tapetum. However, the innermost layer of somatic cells retained its cell-division ability in rbr1-1 lepto1 double mutants, leading to an additional periclinal division and formation of the observed five-layered anther walls (Figure 6C). Ultimately, the extra tapetum-like layer became swollen and disintegrated, similar to the fate of the tapetum in rbr1-1 and lepto1 anthers at the later stages of development (Figure 6A). In summary, the absence of functional LEPTO1 significantly increased the cell-division capacity of somatic cells in the rbr1-1 anther wall, resulting in formation of five-layered anther walls in rbr1-1 lepto1 double mutants. These results further demonstrated the close genetic interactions between RBR1 and LEPTO1. On the basis of the increased cytokinin levels in rbr1 mutants and the close genetic interactions between RBR1 and LEPTO1, we concluded that RBR1 functions in cooperation with the cytokinin signaling pathway to regulate meiosis initiation and anther wall formation.

Functions of RBR1 in the meiosis entry pathway

The meiosis regulatory pathway in male germ cells involves several key events, including initiation of germline stem cells, meiosis initiation, chromosome structure construction at leptotene, meiotic recombination initiation, transition from leptotene to zygotene, the pachytene checkpoint, and pollen grain maturation. All of these steps must be successfully completed for the final product of meiosis, viable gametes, to be produced.

It has previously been established that the classical transcriptional repressor SPL plays a major role in germline initiation. In the absence of SPL in rice, germ cell formation is significantly hindered and the somatic anther wall layers become irregular, implying that SPL is involved in the initial stages of germline initiation (Ren et al., 2018). To examine the relationship between SPL and RBR1, we generated the spl rbr1-1 double mutant. Inspection of transverse sections of spl rbr1-1 anthers revealed that the double-mutant phenotype was indistinguishable from that of the spl single mutant. In spl rbr1-1 double mutants, the typical four-layered somatic anther wall was not formed; instead, anther cells were distributed in an irregular pattern, leading to abnormally shaped cells that were randomly arranged beneath the epidermis. At the late developmental stage, vascular bundles were formed in the center of the anther section (Supplemental Figure 13). DAPI staining showed that the nuclear morphology in the center-located cells was consistent with typical mitotic phenotypes, demonstrating the absence of PMCs in the spl rbr1-1 double-mutant anthers (Figure 7A and 7B). These data indicated that SPL is positioned upstream of RBR1 in the regulation of germline formation.

Figure 7.

RBR1 acts as a gatekeeper in the transition from mitosis to meiosis.

(A and B) DAPI-stained transverse sections of (A)spl and (B)spl rbr1-1 anthers at key developmental stages. In the middle images, regions outlined in white each contain some vascular bundle cell-like cells situated in the anther locule, with enlarged views shown at right. Scale bars, 5 μm.

(C and D) Transverse sections of (C) am1 and (D) am1 rbr1-1 anthers stained with toluidine blue (left) or DAPI (middle and right). In the middle images, regions outlined in white each contain a germ cell situated in the anther locule, with enlarged views shown at right. Scale bars, 5 μm.

(E) RBR1 acts in coordination with LEPTO1 to regulate the transition from mitosis to meiosis. The regulatory pathway that controls meiosis initiation is illustrated for male germ cells in rice. AR, archesporial cell (red); DP, defective pollen grain (yellow); DPMC, defective pollen mother cell (wine); E, epidermis (dark blue); En, endothecium (blue); ML, middle layer (dark green); MLL, middle-layer-like layer (light green); PMC, pollen mother cell (light red); SC, sporogenous cell (pink); SCL, sporogenous-cell-like cell (wine); SPC, secondary parietal cell (green); S, soma (dusty blue); T, tapetum (light green); TL, tapetum-like layer (yellow); UP, unmatured pollen grain (gray).

AM1 plays a fundamental role in the formation of correct chromosome structure in the early stage of meiosis and is required for the leptotene–zygotene transition. In rice AM1 knockouts, the PMCs become arrested at leptotene, resulting in pollen-free anthers (Che et al., 2011). Given the similar anther phenotypes in the corresponding mutants, we sought to investigate the relationship between RBR1 and AM1. To this end, we generated am1 rbr1-1 double mutants. Analysis of stained transverse anther sections demonstrated that both double mutants had the same anther phenotype as rbr1-1 single mutants. am1 single mutants showed the typical average of four PMCs per section at the four-layer stage, whereas am1 rbr1-1 anthers had an average of eight hyper-proliferative SCLs per section. In am1 rbr1-1 anthers, chromosome morphology was comparable between germ cells and the surrounding somatic cells; all of these cells exhibited a loose, dispersed structure with an extensively non-condensed state. The germ cells ultimately deteriorated and vanished in the final stages of anther development in the am1 rbr1-1 mutant (Figure 7C and 7D). Taken together, these findings revealed that RBR1 functions upstream of AM1 in regulating germ cell development during meiosis.

After meiosis initiation, PMCs execute meiotic cell division. Meiotic recombination is a crucial occurrence in meiotic cell division, with SPO11-1 acting as the overall initiator of meiotic recombination by producing DSBs. Disruption of SPO11-1 activity results in a total lack of homologous chromosome pairing, causing defective pollen grain formation (Yu et al., 2010). Examination of transverse sections of spo11-1 rbr1-1 anthers showed that the spo11-1 rbr1-1 anther phenotype was indistinguishable from that of the rbr1-1 single mutant (Supplemental Figure 14A). Thus, the evidence suggested that RBR1 functions prior to meiotic recombination.

Discussion

RBR1 switches mitosis to meiosis in rice

RB is a tumor suppressor that was initially identified in individuals with eye tumors. It has been established as a key regulator of the cell cycle, in which it blocks the G1–S transition by interacting with E2F–DP complexes. RB is also necessary for many other biological processes, including stem cell maintenance, cell differentiation, permanent cell-cycle exit, DNA repair, and maintenance of genome stability (van den Heuvel and Dyson, 2008). Plant RB homologs, known as RBR1 proteins, possess many of the same characteristics and functions as their animal counterparts. These include protein complex formation, functional regulation via phosphorylation, and transcriptional suppression through hindrance of E2F transcription factor activity (Lendvai et al., 2007; Polyn et al., 2015). In addition to its roles in cell-cycle progression, RBR1 has been implicated in a range of other cellular processes such as endoreplication, transcriptional regulation, chromatin remodeling, cell growth, stem cell biology, and cell differentiation. RB thus functions as a “Swiss army knife” protein in a variety of biological processes (Gutzat et al., 2012; Desvoyes et al., 2014; Harashima and Sugimoto, 2016).

In plants, RBR1 proteins are also essential for reproductive development, and their activities are affected by both their abundance and the environment. For example, in Arabidopsis, homozygous rbr1 mutants are gametophytic lethal (Ebel et al., 2004). However, a specific rbr1 allele, rbr1-2, confers temperature sensitivity. Thus, homozygous rbr1-2 mutants can be obtained via growth at a restrictive temperature (Zhao et al., 2017). Interestingly, previous studies have demonstrated that homozygous rbr1-2 Arabidopsis plants can be obtained by decreasing the level of CDKA;1 in the heterozygous rbr1-2 background. The vegetative growth of rbr1-2 homozygous plants showed some differences compared to wild-type plants, but no dramatic effects were apparent. However, the rbr1-2 plants exhibited a significant reduction in fertility (Chen et al., 2009, 2011). Using a chemically activated RNA interference method, prior studies have shown that conditional AtRBR1 downregulation can affect inflorescence and floral meristem maintenance (Ingouff et al., 2006; Borghi et al., 2010). RBR1 is essential for male gametogenesis in Arabidopsis; loss of RBR1 function impedes or delays cell determination (Chen et al., 2009). Furthermore, RBR1 is essential for megasporogenesis. Cultivating homozygous rbr1-2 at a restrictive temperature causes meiocytes to go through multiple mitotic divisions, resulting in extra meiocytes that generate several reproductive units in each seed precursor (Zhao et al., 2017).

In rice, it was recently discovered that two RB genes, RBR1 and RBR2, are involved in reproductive development. Mutations in OsRBR1 inhibit development of floral meristem identity, causing a panicle-like structure or lemma-like organs to form in place of the lodicules, stamens, and pistils. OsRBR2 is primarily expressed in the stamens and is responsible for pollen formation. OsRBR2 mutation leads to abnormal anther morphology and a lack of pollen (Duan et al., 2019). Here, we observed that loss of RBR1 function in rice caused complete male and female sterility, although reproductive organ morphology was normal overall. Detailed analysis of cytological reproductive organ phenotypes revealed hyper-proliferative SCLs in the anther locules of rbr1 mutants during the early stages of anther development. This phenotype was similar to that of the previously characterized homozygous Atrbr1-2 mutant in Arabidopsis. In rice, the hyper-proliferative SCLs could not initiate meiosis, instead stagnating and degrading at the late developmental stage to form pollen-free anthers. By contrast, the hyper-proliferative PMC-like cells in Atrbr1-2 anther locules successfully mature into pollen grains, indicating successful meiosis initiation (Zhao et al., 2017). Consistent with the male reproductive organs, female reproductive organs in the rice rbr1 mutants manifested a similar yet distinguishable phenotype compared with that in Atrbr1-2 mutants. Ovule development is abnormal in Atrbr1-2 mutants because the MMCs undergo multiple mitotic divisions, thus creating extra meiocytes that give rise to many embryo sacs per ovule (Zhao et al., 2017). However, the defective ovule development in rice rbr1 mutants may have been caused by a failure of the germ cells to enter meiosis, resulting in the formation of abnormal ovules that contained only somatic-like cells and lacked an embryo sac (Supplemental Figure 10). These results suggested that RB has distinct functions in Arabidopsis and rice even as it carries out the same biological process, illustrating functional diversification of this protein after speciation.

In addition to the similar yet distinct phenotypes of rice and Arabidopsis rbr1/rbr1-2 mutants, we also noticed discrepancies between previously reported Osrbr1 mutant phenotypes and those observed here. In rice, RBR1 inactivation has been reported to cause a loss of floral meristem identity and considerable defects in floral organ morphogenesis (Duan et al., 2019), a more severe phenotype than those of rbr1 mutants studied here. Plant RB proteins are highly sensitive to dosage and the environment, and the distinct phenotypes in rbr1 mutants may therefore be a result of differences in genetic backgrounds and growth conditions. Duan et al. (2019) generated rbr1 mutants in the indica cultivar Minhui86, whereas we generated rbr1 mutants in the Zhongxian 3037 (indica) and Yandao 8 (japonica) backgrounds. Furthermore, the precise mutation sites in our rbr1 mutants differed from those in the previous study. Finally, plants were previously grown in Fuzhou, China (26°N, 119°E; a subtropical zone) (Duan et al., 2019), whereas the plant materials used here were grown in Beijing, China (39°N, 116°E; a warm temperate zone). The distinct rbr1 mutant phenotypes present a fascinating topic for future study of the mechanisms by which RB responds to external and internal environmental stimuli. Compared with the previously reported functions of RBR1 in Arabidopsis and rice, we discovered a novel function of RBR1 in plant reproductive development: switching mitosis to meiosis in male germ cells. This function has not been reported previously, and its discovery enhances our understanding of RB. More importantly, delineation of the precise molecular regulatory mechanism used by RBR1 in the transition from mitosis to meiosis will open new possibilities in reproductive developmental biology.

The RBR1 regulatory module may be linked to the cytokinin pathway for regulation of meiosis entry

The regulation of meiosis initiation appears to be more intricate in plants than in yeast and mice, involving multiple regulatory pathways. In addition, the control of meiosis initiation in males and females is entirely non-conserved. In this study, we discovered that the RBR1–WUS regulatory module, which was identified through examination of female gametes, does not play a role in regulating the initiation of meiosis in male gametes. Moreover, there is a notable absence of conservation across species in various regulatory mechanisms associated with the initiation of meiosis. Notably, different phenotypes were observed in the male and female reproductive cells of the rice rbr1 mutant compared with those of the Atrbr1 mutant (Chen et al., 2009, 2011; Zhao et al., 2017). Furthermore, different abnormal phenotypes due to the absence of WUS were observed in the respective floral organs of rice and Arabidopsis (Leibfried et al., 2005; Lu et al., 2015; Tanaka et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2017). The absence of functional conservation between male and female germline formation, together with marked differences in the processes that regulate meiosis initiation among species, make it unsurprising that loss of WUS function did not restore the meiosis entry of male germ cells in rice rbr1 mutants.

Cytokinins are a class of phytohormones with a wide range of molecular structures. The importance of cytokinins in various developmental processes, including reproductive development, has been increasingly recognized in recent years (Ashikari et al., 2005; Terceros et al., 2020). For instance, the cytokinin receptors AHK2, AHK3, and AHK4/CRE1 are involved in integument and ovule development in Arabidopsis. The triple mutant ahk2-2 ahk3-3 cre1-12/ahk4 displays impaired integument initiation, causing some ovule primordia to remain in the form of long finger-like structures. In addition, two major transcription factors, BELL1 (BEL1) and SPL, significantly affect ovule development by interacting with the cytokinin signaling pathway (Brambilla et al., 2007; Bencivenga et al., 2012). The bel1 spl double mutant exhibits finger-like ovule structures without integuments, comparable to those of ahk2-2 ahk3-3 cre1-12 mutants; expression of both BEL1 and SPL is regulated by cytokinin (Ebel et al., 2004). Moreover, CKI1, a factor associated with cytokinin sensing, plays a vital role in cytokinin signaling and female gametophyte formation. cki1-5, cki1-6, and cki1-9 mutants all demonstrate lethality (Deng et al., 2010; Yuan et al., 2016). Furthermore, two types of Arabidopsis response regulators (ARRs) in the cytokinin pathway are associated with the designation of cells to become female gametophyte cells. The type-A ARR double mutant arr7 arr15 and the type-B ARR quadruple mutant arr1-3 arr2-2 arr10-2 arr12-1 both form a significant number of ovules with arrested gametophytes (Leibfried et al., 2005; Cheng et al., 2013). Type-B RRs are also important for rice reproductive development; rr21 rr22 rr23 triple mutants show reduced fertility as a consequence of defective stigma development. Absence of ORR4 (RR24 or LEPTO1) causes serious deficiencies in megasporogenesis and microsporogenesis, resulting in complete male and female infertility (Zhao et al., 2018; Worthen et al., 2019). These prior studies demonstrate that a number of factors related to the cytokinin pathway are involved in reproductive development. Notably, germline stem cell initiation and entry into meiosis are the most essential steps in this process. However, our understanding of the roles played by the cytokinin signaling pathway in these fundamental events is far from complete.

In the present study, we found that RBR1, a key cell-cycle controller, is indispensable for meiosis initiation in rice. Loss of RBR1 function caused excessive germ cell proliferation in anther locules during the early reproductive developmental stage. These aberrant germ cells were unable to initiate meiosis, instead undergoing mitotic division and ultimately deteriorating during the late developmental stage. rbr1 mutants also displayed a substantial increase in cytokinin content. The higher concentration of cytokinin in rbr1 spikelets may be closely associated with the overabundance of germ cells, given the strong correlation of cytokinin with cell proliferation. We further ascertained that cytokinin response factor expression was heavily compromised in the rbr1 mutants. In particular, expression levels of type-B response factors, especially LEPTO1, were significantly decreased in rbr1. These data suggest that disruptions in the cytokinin pathway are linked to impaired initiation of meiosis in rbr1. To examine this connection, we generated rbr1-1 lepto1 double mutants, which had an increased number of GCLs in the anther locules (∼2.4 times more than in rbr1-1 single mutants). In addition, rbr1-1 lepto1 double mutants contained an anomalous five-layered anther wall that resulted from an extra periclinal division of the innermost anther wall layer at the four-layer stage. Taken together, these findings strongly suggest that loss of LEPTO1 function significantly enhances the division rate of both germline stem cells and somatic stem cells in rbr1, resulting in hyper-proliferative germ cells in the center surrounded by a five-layered anther wall. Mutation of LEPTO1 significantly exacerbated the defects of rbr1, implying a close genetic relationship between these genes in the control of meiosis entry. We therefore hypothesized that excessive cytokinin content may have caused hyper-proliferation of germ cells and that downregulation of LEPTO1 may have been responsible for defective entry into meiosis in rbr1.

Male germ cells are an ideal system for investigating the transition from mitosis to meiosis

To date, a great deal of progress has been made in the field of plant germ cell development, largely through use of Arabidopsis MMCs as a model system (Pinto et al., 2019; Böwer and Schnittger, 2021). After ovule initiation in Arabidopsis, the essential events of female germline development take place in the distal area of the ovule. The first visible sign of germline development is the selection of a diploid AR from a cluster of pluripotent subepidermal cells. This process of AR selection in ovule primordia can also be defined as germline stem cell initiation. In the ovule, ARs act as meiocyte precursors and expand to directly form MMCs to initiate meiosis. Because ARs in the ovule differentiate into MMCs within a very short time and without any mitotic cell division, it is challenging to distinguish ARs from MMCs. This also poses difficulties in differentiating between germline stem cell initiation and meiosis initiation during female germ cell development. It is unclear to what extent the predecessor of an MMC is an AR, because there are no clear criteria to differentiate between ARs and MMCs. Furthermore, morphological and functional criteria are often mixed in studies of ovules, resulting in conflation of AR initiation and meiosis initiation (Pinto et al., 2019; Böwer and Schnittger, 2021). However, these two events are fundamentally different in their biological essence and likely to differ in their regulatory mechanisms.

In contrast to meiocyte formation in ovules, the ARs in male reproductive organs undergo multiple mitotic divisions, eventually forming PMCs in microsporangia. At the early stage of anther primordium initiation, one larger cell encircled by the epidermis is identified as an AR. The AR undergoes periclinal division to form PPCs and SCs. These PPCs and SCs then undergo successive periclinal and anticlinal divisions, forming a two-layered anther wall followed by a three-layered anther wall. Within the anther locules during the two- and three-layer stages, all germ cells are classified as SCs. Both ARs and SCs are reproductive stem cells, which can continue to divide through mitosis. At the four-layer stage, germ cells located in the anther locules are fated to become meiocytes and are designated PMCs. Because of the tight coordination between germ cell and somatic parietal cell growth, it is easy to distinguish among ARs, SCs, and PMCs in microsporangia (Ma, 2005; Walbot and Egger, 2016). The somatic cell layer of the anther wall is a standard by which the developmental stages of the germ cells situated inside can be distinguished, simplifying the recognition of two separate biological events: germline stem cell initiation and meiosis initiation. This attribute makes male germ cells an ideal system for investigating the transition from mitosis to meiosis.