Recent high profile scandals in the United Kingdom have highlighted the changing values by which the National Health Service is judged.1 The public expects, and the government has promised to deliver, a health service that is ever safer, constantly up to date, and focused on patients' changing needs. Successful health services in the 21st century must aim not merely for change, improvement, and response, but for changeability, improvability, and responsiveness.

Educators are therefore challenged to enable not just competence, but also capability (box). Capability ensures that the delivery of health care keeps up with its ever changing context. Education providers must offer an environment and process that enables individuals to develop sustainable abilities appropriate for a continuously evolving organisation. Recent announcements in the United Kingdom of a “university for the NHS,”2 a “national leadership programme,”3 and “workforce confederations”4 raise the question of what kind of education and training will help the NHS to deliver its goals

Capability is more than competence

Competence—what individuals know or are able to do in terms of knowledge, skills, attitude

Capability—extent to which individuals can adapt to change, generate new knowledge, and continue to improve their performance

Summary points

Traditional education and training largely focuses on enhancing competence (knowledge, skills, and attitudes)

In today's complex world, we must educate not merely for competence, but for capability (the ability to adapt to change, generate new knowledge, and continuously improve performance)

Capability is enhanced through feedback on performance, the challenge of unfamiliar contexts, and the use of non-linear methods such as story telling and small group, problem based learning

Education for capability must focus on process (supporting learners to construct their own learning goals, receive feedback, reflect, and consolidate) and avoid goals with rigid and prescriptive content

The principles of complexity theory introduced earlier in this series (box) are explicitly or implicitly espoused in a series of NHS documents covering continuing professional development and lifelong learning5; learning networks6; quality improvement and organisational learning7; evidence based practice8; information and knowledge management9; and interprofessional working.10 This article highlights specific areas where complexity theory can inform the development of new educational approaches.

Developing capability: transformational learning

Individuals and systems change because they learn.11 Indeed, pedagogical research has shown that adults choose to learn because they want to change.12 The process of developing new behaviours in the context of real life experiences enables individuals to adapt to or co-evolve with new situations, thereby supporting the transition from individual competence to personal capability.13

Complexity concepts applicable to education and training

Neither the system nor its external environment are, or ever will be, constant

Individuals within a system are independent and creative decision makers

Uncertainty and paradox are inherent within the system

Problems that cannot be solved can nevertheless be “moved forward”

Effective solutions can emerge from minimum specification

Small changes can have big effects

Behaviour exhibits patterns (that can be termed “attractors”)

Change is more easily adopted when it taps into attractor patterns

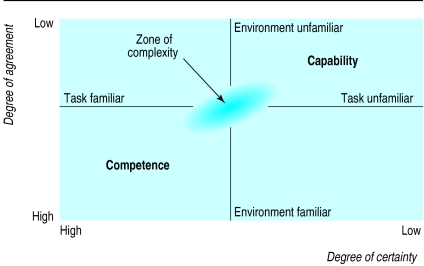

Learning takes place in the zone of complexity16 (figure), where relationships between items of knowledge are not predictable or linear, but neither are they frankly chaotic. Learning which builds capability takes place when individuals engage with an uncertain and unfamiliar context in a meaningful way. Those of us who recall trying to prepare for house jobs by reading the textbook beforehand will know that capability cannot be taught or passively assimilated: it is reached through a transformation process in which existing competencies are adapted and tuned to new circumstances. Capability enables one to work effectively in unfamiliar contexts.

For example, suppose a doctor is doing a locum in a contraceptive clinic and the patient is a sex worker who speaks little English and is suspected of being HIV positive. The task has changed from the typical “textbook” pill check requiring merely competence (familiar task in a familiar environment) to a complex consultation testing the doctor's capability (somewhat unfamiliar task in a somewhat unfamiliar environment). The doctor best able to cope with this is one whose training provided continual opportunities to be stretched by the uniqueness of each context, where knowledge had to be applied in ways the textbook did not anticipate, and where “expertise” was seen as the ability to access knowledge and make connections across seemingly disparate fields and life experiences.

In complex adaptive systems the behaviour of the individual agents, and therefore of the system of which they are part, evolves in response to local feedback about the impact of actions. Similarly, the basis of transformational learning is the information that is fed back to learners about the impact of their own actions and those of others. An education process that provides feedback about performance as it takes place will enhance capability. One such initiative based on feedback is the Norwegian continuing medical education system, where doctors in a peer group state learning needs, discuss ways forward, take action, and then report back on the feedback from the action.

Reflective learners are receptive to feedback and able to adapt appropriately, while poor learners are either unreceptive to feedback or they adapt inappropriately.17,18 Reflective learners transform as the world around them changes: poor learners simply complain about it.

Relational learning

Not so long ago, knowledge was hard to come by and experts were people with a lot of it. These days, there is so much knowledge available that we risk drowning in it.19 The official exhortation to “feel good about not knowing everything”20 resonates well with complexity theory's acknowledgement of the uncertain and unknowable and with the need to be alert to emerging information from different sources. The modern expert is someone who knows how to access knowledge efficiently and judiciously and who can form conceptual links between seemingly unrelated areas. The successful diabetologist, for example, is not necessarily the individual who is au fait with the latest research on insulin kinetics but one who is able to draw appropriately on the wider literature of pharmacology, nephrology, ophthalmology, cardiovascular epidemiology, psychology, anthropology, economics, and informatics.

Learning how things are interconnected is often more useful than learning about the pieces. Traditional curriculums, based on a discrete and simplistic taxonomy of disciplines that focus on the acquisition of facts, usually highlight content without helping learners understand the interrelationships of the parts. Without this understanding of the interactions and relations between the pieces it is difficult to apply the learning in a unique context.

Non-linear learning

“Checklist driven” approaches to clinical care, such as critical appraisal, clinical guidelines, care pathways, and so on, are important and undoubtedly save lives. But what often goes unnoticed is that such approaches are useful only once the problem has been understood. For the practitioner to be able to make sense of problems in the first place requires intuition and imagination—both attributes in which humans, reassuringly, still have the edge over the computer.21 Education that makes use of the insights from complex systems helps to build on these distinctly human capabilities.

LIANE PAYNE

The complex real world is made up of messy, fuzzy, unique, and context embedded problems. Context and social interaction are critical components of adult learning.22 Adults need to know why they need to learn something and they learn best when the topic is of immediate value and relevance.23 This is particularly true in changing contexts where capability involves the individual's ability to solve problems—to appraise the situation as a whole, prioritise issues, and then integrate and make sense of many different sources of data to arrive at a solution. Problem solving in a complex environment therefore involves cognitive processes similar to creative behaviour.24 These observations are directly opposed to current approaches in continuing education for health professionals, where the predominant focus is on planned, formal events, with tightly defined, content oriented learning objectives.

For example, a typical course on asthma management for nurses might include a series of talks from experts on drugs, devices, monitoring, emergency care, and audit. Participants might be told that “on completion of this course, we expect that you will be able to advise a patient on the benefits and limitations of different inhaler devices,” and so on. This approach, while providing helpful information on content for the prospective delegate, ignores the fact that learners actively build, rather than passively consume, knowledge, and that learning simply does not progress via neat “building blocks” of factual content or skills training.

In reality a nurse who attended this asthma course might find that she didn't really understand the lecture on the use of steroids until a colleague explained some key points to her in the coffee queue, using examples drawn from her own patients. A more imaginative programme might have included a problem solving workshop on the broad theme of medication, with case studies brought by participants to stimulate group discussion, prioritise learning needs, and expose particular ambiguities (“what exactly don't you understand about this topic?”) before any specific content is introduced. Inclusion in the timetable of a structured reflection period towards the end of the workshop (for example, addressing the question “what have we learnt?”) enables the key learning points to be consolidated. A challenge for the proposed initiatives in the NHS will be to deliver vocational and learning oriented programmes without taking on the rigid features of more traditional “academic” curriculums.

We believe that the imaginative dimension of professional capability is best developed through non-linear methods—those in which learners embrace a situation in all its holistic complexity. The most straightforward example of a non-linear method is the story.25 Doctors and nurses have long used story telling in professional training, and there is some evidence that clinical knowledge is stored in memory as stories (“illness scripts”) rather than as discrete facts.26 There has, however, been remarkably little formal research into how stories might be used more effectively in professional education and service development. More work needs to be done on the formal use of story telling in particularly complex situations where a holistic view is essential—such as significant event audit,27 exploring the extremes of illness experience (such as that of the profoundly disabled or traumatised patient28), and the management of patients from other cultures.29 The story can be told (as in a conventional case presentation), in the first person (as in a patient's own illness narrative30), or enacted (as in role play31).

Another well known non-linear method is small group, problem based learning, in which a case history forms the basis of an exploratory dialogue facilitated by the tutor, and an emerging action plan is worked out by a group of participants.32 The group is encouraged to share ideas, divide up any necessary research work, and reconvene after a few days to add emerging data to what is already known. Problem based learning is no panacea: while it is valued and enjoyed by students and improves their ability to solve problems, perhaps unsurprisingly it does not improve their content knowledge as assessed in written examinations,33 and it is debatable whether problem solving skills developed through artificial classroom situations will reliably transfer to behaviour in the real world. Clearly, the situation is not an “either or” choice but rather a dynamic balance, characteristic of a complex adaptive system, in which both content learning and non-linear learning methods are needed.

Process techniques

Complexity thinking maintains that an emergent behaviour, such as capability building, can be aided by some minimal structure (for example, minimum specifications and feedback loops). As education moves away from the potentially over structured “table d'hôte” menu of the predefined, content oriented syllabus designed for the mass market to the more “à la carte” menu designed for the complex, individual, self directed learner, attention needs to be focused on the process of learning.

Process-oriented learning methods29

Informal and unplanned learning

Experiential learning—shadowing, apprenticeship, rotational attachments

“Networking” opportunities—during formal conferences and workshops, through open plan poster exhibitions, or extended coffee and lunch breaks, for example

Learning activities—in structured course materials, such as reflection exercises, suggestions for group discussion

“Buzz groups” during intervals in lectures—the lecturer invites participants to turn to a neighbour and undertake a short task before the lecture resumes

Facilitated email list servers for professional interest groups

Teachback opportunities—newly skilled workers training others in new techniques and sharing their understanding

Feedback—responses that provide the learner with information on the real or projected outcome of their actions

Self directed learning

Mentoring—named individuals provide support and guidance to self directed learners

Peer supported learning groups—the small group process is used for mutual support and problem solving

Personal learning log—a structured form for identifying and meeting new learning needs as they arise

Appraisal—a regular, structured review of past progress and future goals

Flexible course planning that explicitly incorporates input from learners at key stages—using a ‘Post-it’ note exercise to add new learning objectives or amend a draft programme, for example

Modular courses with a high degree of variety and choice

Non-linear learning

Case based discussions—grand rounds, clinical case presentations, significant event audit

Simulations—opportunities to practise unfamiliar tasks in unfamiliar contexts by modelling complex situations

Role play

Small group, problem based learning (see text for definition)

Teambuilding exercises—activities focused on the group's emergent performance rather than that of the individual

The use of process techniques is the crucial distinction between learning which has a flexible and evolving content and learning which is simply disorganised and is unstructured, disjointed, and driven only by convenience or coincidence. When process techniques are used, learning is driven by needs and is characterised by a dynamic and emergent personal learning plan with explicit goals, protected time for reflection and study, mentoring or peer support, and perhaps a written learning log or record of achievement.34 Process oriented techniques such as those listed (box) provide boundaries for the learning and the opportunity for prompt and relevant feedback from tutors or peers. Tutors adopt the role of facilitator, rather than lecturer or trainer.

As noted above, a small group can be a powerful educational structure for solving complex problems and promoting capability. In a small group the combination of individuals can achieve more than the sum of the parts (non-linear effects in a complex system), as social interaction between members stimulates learning, raises individuals' confidence, and increases motivation.31 The group can also be a powerful source of both positive and negative feedback on an individual's actions. Discovering ways in which personal behaviour impacts on the system, focusing on and assessing relationships, and finding ways to harness skills of individuals and teams to increase the amount of feedback, and thus learning.

But being part of a poorly functioning small group can be an unproductive, intimidating, and even traumatic experience. The biggest mistake made by facilitators of such groups is to assume that because the task is intended to be emergent and learner focused, there is no need for attention to process. In reality, a group will feel sufficiently secure to take risks and be creative only if clear boundaries and ground rules have been set. In particular, minimum specifications for a small group might cover such items as the nature and scope of the task, the rules of confidentiality, the time limit, any differentiation of roles (who will chair, keep notes, and so on), and the group's responsibility to its external stakeholders—the budget for a project or the details of what needs to be handed in at the end of the session, for example.31

Attention to process is the distinguishing characteristic of productive, non-linear learning. Future educational efforts, such as the university for the NHS or the leadership centre, almost certainly need fewer content experts and more tutors, mentors, and facilitators. The development of expertise in the learning process is itself a complex learning experience, and preliminary guidance has recently been published for both individual mentoring35 and group based learning.31

The future of learning in healthcare systems

The word “university” conjures up images of lecture theatres, files of notes, and examinations designed to test retained skills and knowledge. As the table shows, and the stirring rhetoric of recent policy documents acknowledges, the new university for the NHS will need to break from the bonds of this image and adopt learning processes that are coherent with the complex adaptive experience of health care. The “learning outcomes” in the new curriculum should focus on capabilities, not competencies.

Figure.

Competence and capability in complex adaptive systems (based on Stacey14 and Stephenson15)

Table.

| Traditional education and training | The future for education and training | |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | Knowledge is static, finite, linear, and private | Knowledge is dynamic, open ended, multidimensional, and public |

| Learning | Instructivist model (“facts” are transmitted from teachers to students) | Constructivist model (concepts are acquired, built and modified through social discourse, incorporated into appropriate schemes, and tested in action) |

| The university | Machine bureaucracy whose greatest resource is its stock of high-status knowledge | Adapting, dynamic and evolving organism whose greatest resource is its staff and the networks they maintain within and beyond its boundaries |

| The teacher | “Sage on the stage” | “Guide on the side” |

| Student population | Homogeneous (young, intellectually elite, full time) | Heterogeneous and shifting (wide range of ages, social and educational backgrounds, abilities, aims and expectations) |

| Student experience | Generally precedes definitive career choices and personal relationships | Lifelong learning means that education converges with (and is influenced by) work, family, and personal development |

| Assessment | Based on reproduction of facts | Based on analysis, synthesis, and problem solving |

| Course timetable | Teacher-centred, “Fordist” model lacking choice and flexibility | Learner centred model in which students mix and match options from different courses, departments, and even universities |

| Curriculum development | Historical model (students learn X because it's always been included) | “Outcomes” model (students learn X because employers require it as a competence) |

| Time and space utilisation | Synchronous, mass, single location learning (eg, lecture theatre, laboratory) | Asynchronous, individualised, with networked learning support |

| Quality assurance | Paperwork exercise that is resented by staff | Ongoing process of personal, professional, and organisational learning that is owned and driven by staff |

| Evaluation | Teacher focused (“what is being provided?”) | Learner focused (“what are the learners' needs and are they being met?”) |

| Relation between research and teaching | Discrete and hierarchical separation; addressed by different individuals, teams, and funding streams | Integrated model in which a major research question in any discipline is the nature of knowledge and how it can be effectively and efficiently acquired and utilised. |

| University funding | Mainly from block grants to institutions from a few official sources | Increasing reliance on diffuse and decentralised sources—including support for individual students, industrial sponsorship for bespoke courses, and partnerships with local businesses and services |

This is the last in a series of four articles

Footnotes

Series editors: Trisha Greenhalgh, Paul Plsek

Competing interests: SWF is an independent consultant receiving fees for work on this topic.

References

- 1.Smith R. All changed, changed utterly. British medicine will be transformed by the Bristol case. BMJ. 1998;316:1917–1918. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7149.1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomson A, Sanders C. Labour pledges NHS university. Times Higher Educ Suppl 2001 May 18:1. www.thes.co.uk/ (accessed 16 Aug 2001).

- 3.Department of Health. The NHS plan. London: DoH; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department of Health. A service of all the talents: developing the NHS workforce. London: Department of Health; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Department of Health. Continuing professional development: quality in the new NHS. London: Department of Health; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Department of Health. Welcome to the NHS learning network: spreading good practice. London: NHS Executive; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Secretary of State for Health. A first class service: quality in the new NHS. London: Stationery Office; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Department of Health. Promoting clinical effectiveness: a framework for action in and through the NHS. Leeds: NHS Management Executive; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Secretary of State for Health. Working together with health information. London: Stationery Office; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Department of Health. “In the patient's interests”: multiprofessional working across organisational boundaries. Leeds: NHS Management Executive; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Senge P. The fifth discipline: the art and practice of the learning organization. New York: Doubleday/Currency; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenhalgh T. Intuition and evidence—uneasy bedfellows? Br J Gen Pract (in press). [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Hite J. Learning in chaos. Houston, TX: Gulf Publishing Company; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stacey RD. Strategic management and organizational dynamics. London: Pitman Publishing; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stephenson J. Capability and quality in higher education. In: Stephenson J, Yorke M, editors. Capability and quality in higher education. London: KoganPage; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Plsek P, Greenhalgh T. The challenge of complexity in health care. BMJ. 2001;323:625–628. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7313.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hull C. Principles of behavior. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1943. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thorndike E. The fundamentals of learning. New York: Teachers College Press; 1932. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wyatt JC. Reading journals and monitoring the published work. J R Soc Med. 2000;93:423–427. doi: 10.1177/014107680009300809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slawson DC, Shaughnessy AF, Bennet JH. Becoming a medical information master: feeling good about not knowing everything. J Fam Pract. 1994;38:505–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dreyfus HL, Dreyfus SE. Mind over machine: the power of human intuition and expertise in the era of the computer. Oxford: Blackwell; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lave J, Wenger E. Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knowles M. The adult learner: a neglected species. 3rd ed. Houston, Texas: Gulf Publishing; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Langley P, Simon H, Bradshaw G, Zytkow J. Scientific discovery: computational explorations of the creative processes. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenhalgh T, Hurwitz B. Narrative based medicine: why study narrative? BMJ. 1999;318:48–50. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7175.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cox K. Stories as case knowledge; case knowledge as stories. Med Educ. 2001;35:862–866. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.01016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pringle M, Bradley CP, Carmichael CM, Wallis H, Moore A. Significant event auditing: a study of the feasibility and potential of case-based auditing in primary care. London: RCGP; 1995. . (Occasional paper 70) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crossley ML, Crossley N. “Patient” voices, social movements and the habitus; how psychiatric survivors “speak out.”. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52:1477–1489. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00257-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skultans V. Anthropology and narrative. In: Greenhalgh T, Hurwitz B, editors. Narrative based medicine: dialogue and discourse in clinical practice. London: BMJ Publishing; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herxheimer A, McPherson A, Miller R, Shepperd S, Yaphe J, Ziebland S. Database of patients' experiences (DIPEx): a multi-media approach to sharing experiences and information. Lancet. 2000;355:1540–1543. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02174-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elwyn G, Greenhalgh T, Macfarlane F. Groups: a hands-on guide to small group work in health care, education, management and research. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bligh J. Problem-based, small group learning. BMJ. 1995;311:342–343. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7001.342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vernon DTA, Blake RL. Does problem-based learning work? A meta-analysis of evaluative research. Acad Med. 1993;68:550–563. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199307000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Challis M. Personal learning plans. Med Teach. 2000;22:225–236. [Google Scholar]

- 35.English National Board for Nursing, Midwifery and Health Visiting. Preparation of mentors and teachers—a new framework of guidance. London: Department of Health; 2001. http://tap.ccta.gov.uk/doh/point.nsf/publications (accessed 24/8/01). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Daniel JS. London: Kogan Page; 1996. The knowledge media. In Mega-universities and knowledge media. Technology strategies for higher education; pp. 101–135. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rowley DJ, Lujan HD, Dolence MG. Strategic choices for the academy: how demand for lifelong learning will re-create higher education. San Francisco: Jossey Bass; 1998. [Google Scholar]