Editor—Rushton et al suggest that reference ranges for men should be used to assess iron status in women of childbearing age.1 They do, however, make some incorrect assumptions and do not consider the practical implications of such a change.

Women must have sufficient iron stores to prevent iron deficiency from menstrual blood loss or pregnancy. However, one in 150 people in the United Kingdom are homozygous for the C282Y mutation of the HFE gene, which is associated with haemochromatosis.2 Although the clinical penetrance of this genotype is low, widespread measures to increase the intake of iron in younger women will also increase the intake of men and postmenopausal women. It is therefore important that any changes in lower limits of indices of iron status are firmly supported by clinical and experimental evidence.

Rushton et al are incorrect in assuming that different lower limits for ferritin are used for detecting iron deficiency in young men and women. Although reference ranges (95%) in healthy young adults differ—for example, 35-220 μg/l for men and 9-136 μg/l for women2—the limit for iron deficiency used by clinicians is around 15 μg/l for both men and women, a value originally established by determining the highest value found in patients with iron deficiency anaemia.3

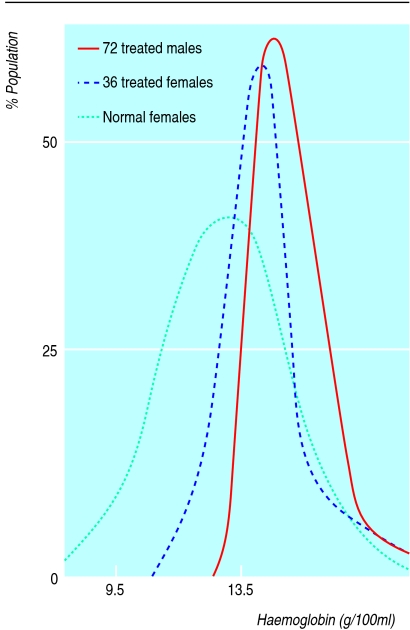

The national dietary and nutritional survey reported a median value for haemoglobin concentration in British women of childbearing age of 132 g/l. Increasing the lower cut-off point to 130 g/l, as used for men, would therefore define half the premenopausal adult female population of the United Kingdom as anaemic. Zhu and Haas found that in women with serum concentrations of ferritin <16 μg/l and haemoglobin >120 g/l, iron supplementation increased serum concentrations of ferritin but not haemoglobin.4 We also have to ask how the iron intake of all these women would be increased. A recent dietary intervention study showed that highly motivated people with mild iron deficiency can improve iron status through diet but that supplements are a more practical option.5 Supplements do, however, produce unpleasant side effects in a notable proportion of individuals, and any programme entailing the use of supplements is likely to have a detrimental effect on the wellbeing of a notable number of women.

We believe that there is no evidence to support reclassification of haemoglobin and serum concentrations of ferritin in women to normal values for men. Furthermore, we are unable to see how such a move could result in a positive outcome for women's health and welfare with no adverse effects.

References

- 1.Rushton DH, Dover R, Sainsbury AW, Norris MJ, Gilkes JJH, Ramsay ID. Why should women have lower reference limits for haemoglobin and ferritin concentrations than men? BMJ. 2001;322:1355–1357. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7298.1355. . (2 June.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jackson HA, Carter K, Darke C, Guttridge MG, Ravine D, Hutton RD, et al. HFE mutations, iron deficiency and overload in 10,500 blood donors. Br J Haematol. 2001;114:474–484. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Worwood M. Serum ferritin. In: Jacobs A, Worwood M, editors. Iron in biochemistry and medicine. II. London: Academic Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu YI, Haas JD. Response of serum transferrin receptor to iron supplementation in iron-depleted, nonanemic women. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;67:271–275. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/67.2.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heath A-LM, Skeaff CM, O'Brien SM, Williams SM, Gibson RS. Can dietary treatment of pre-anemic iron deficiency improve iron status? J Am Coll Nutr 2001 (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]