Abstract

Purpose of review

To review the rationale for and the potential clinical benefits of an early approach to viral acute respiratory infections with NSAIDs to switch off the inflammatory cascade before the inflammatory process becomes complicated.

Recent findings

It has been shown that in COVID-19 as in other viral respiratory infections proinflammatory cytokines are produced, which are responsible of respiratory and systemic symptoms. There have been concerns that NSAIDs could increase susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection or aggravate COVID-19. However, recent articles reviewing experimental research, observational clinical studies, randomized clinical trials, and meta-analyses conclude that there is no basis to limit the use of NSAIDs, which may instead represent effective self-care measures to control symptoms.

Summary

The inflammatory response plays a pivotal role in the early phase of acute respiratory tract infections (ARTIs); a correct diagnosis of the cause and a prompt therapeutic approach with NSAIDs may have the potential to control the pathophysiological mechanisms that can complicate the condition, while reducing symptoms to the benefit of the patient. A timely treatment with NSAIDs may limit the inappropriate use of other categories of drugs, such as antibiotics, which are useless when viral cause is confirmed and whose inappropriate use is responsible for the development of resistance.

Keywords: acute respiratory infections, choice of NSAID, inflammatory response, NSAIDs

INTRODUCTION

Acute respiratory tract infections (ARTIs) have a significant morbidity and mortality burden worldwide and represent a global health concern. Throughout the world, more than 50% of ARTIs are caused by viruses, including, but not limited to, human rhinovirus, human coronavirus, influenza A and B viruses, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) [1,2]. Bacterial and viral ARTIs are often clinically indistinguishable and, even though the majority are of viral cause, they are by far the most common reason for prescribing an antibiotic in primary care [1]. In outpatient practice, these infections are mostly self-limiting and do not require antimicrobial therapy, but rather symptomatic treatment, keeping in mind that the symptoms are caused by a local and systemic inflammatory response [3]. In recent years, the experience with the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has strongly underlined the importance of etiological diagnosis of infections and suggested that a prompt control of inflammation with antiinflammatories may limit viral infections and prevent complications. Nowadays, the etiological diagnosis of respiratory infections is made more accessible thanks to the availability of specific diagnostic kits that allow the identification of different viruses and the discrimination between bacterial and viral etiology, simplifying the choice of the most appropriate therapy. Even though symptoms typically last less than 10 days, they may be troublesome and therefore treatment should be timely [4].

The host reaction plays a major role in the pathogenesis of viral ARTI symptoms and the similarities in their clinical presentation suggest a common inflammatory and immune response pattern to different etiologic agents. Once again, the COVID-19 pandemic allowed us to increase and consolidate our notions about the pathophysiology of respiratory infections [5]. The primary concept is that every infection induces an inflammatory response. Therefore, switching off the inflammation at the very first symptoms could be a winning strategy in the management of ARTIs.

In this article, we discuss the rationale for an early approach to viral ARTIs with NSAIDs as the most appropriate to switch off the inflammatory cascade resulting from the infection before the inflammatory process becomes complicated; this could help to limit the development of clinical complications and the excessive and inappropriate use of other classes of drugs, including antibiotics, when there is no specific indication to use them, with their major impact on the growing issue of resistance. We review here the pathophysiology of ARTIs, the subsequent development of a local and systemic inflammatory process, the main NSAIDs and their characteristics, and discuss their potential role in the early treatment of ARTIs.

Box 1.

no caption available

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF ACUTE RESPIRATORY TRACT INFECTIONS

Rather than the pathogen-specific damage, the host defense mechanisms in response to infection are responsible for the clinical symptoms of viral ARTIs. Inflammation is the initial body's physiological response to tissue damage caused by infection, and the clinical outcomes of ARTIs result from the immune response aimed at pathogen clearance or from exaggerated and prolonged inflammation.

Airway endothelial cells are responsible for regulating the immune response by recruiting innate immune cells and stimulating the production of innate chemokines and cytokines. The beginning of infection is characterized by the influx of polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs). As inflammation progresses, more cell types are activated by a signaling network and attracted to the inflamed tissue. Macrophages, mast cells, and dendritic cells trigger an acute phase response with production of proinflammatory cytokines.

Depending on the type of pathogen, release of a wide variety of cytokine groups occurs. In particular, the entry of respiratory viruses triggers the release of locally produced interleukin-8 (IL-8), which in turn increases the production of nasal secretions and stimulates the recruitment of neutrophils. Locally released vasoactive kinins contribute to the symptoms of respiratory virus infection increasing vascular permeability, vasodilation, and glandular secretion [3]. COVID-19 pathogenesis has been shown to be associated with excessive chemokines release – the so-called cytokine storm – as a result of the lysis of infected cells and SARS-CoV-2 replication in the host cells. Not only in SARS-CoV-2 infection but also in influenza virus infections, proinflammatory cytokines are produced, including IL-6, tumor necrosis factor- (TNF-α), interferon-α (IFN-α), IL-8, and IL-1β, resulting in the development of fever, nasopharyngeal mucous production, and respiratory and systemic symptoms [3,6▪,7,8].

Cell recruitment and the production of related mediators represent important defense mechanisms against infection. However, excessive early cytokine response and prolonged persistence of inflammation in the respiratory tissues eventually result in further tissue damage and worsening of the inflammatory process.

THE INFLAMMATORY PROCESS IN VIRAL ACUTE RESPIRATORY TRACT INFECTIONS

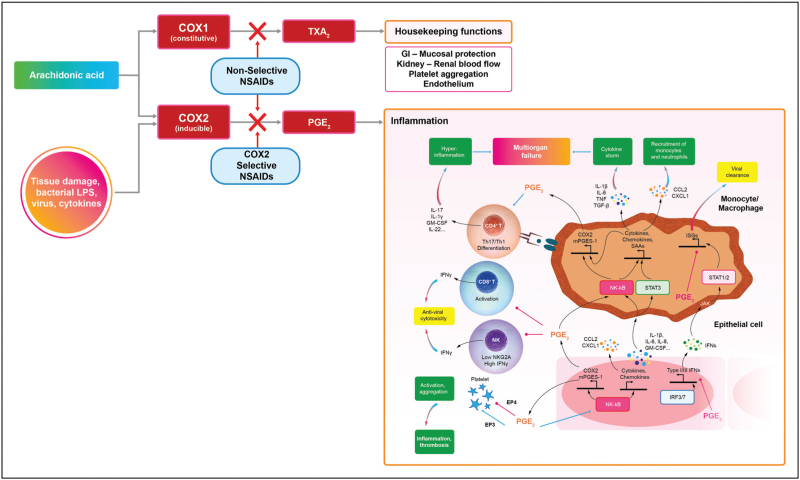

Cyclooxygenase (COX) is well known as a major structural enzyme in the production of inflammatory mediators. The COX1 and COX2 isoforms are closely related, sharing more than 60% sequence identity, and both catalyze the formation of prostaglandins and thromboxane A2 (TxA2) – named prostanoids – from arachidonic acid, which in turn is released from membrane phospholipids by phospholipase A2, once activated by inflammatory, physical, and chemical stimuli (Fig. 1). COX1 is a predominantly constitutive enzyme widely expressed in most tissues and involved in regulating the homeostasis of the gastrointestinal mucosa, endothelium, platelets, kidneys, and uterus [9▪▪]. COX2 is a predominantly inducible enzyme, considered to be mainly responsible for the production of prostanoids in inflammation, which are involved in vasodilation, increasing vascular permeability, and leukocyte chemotaxis. Prostaglandins have long been known to act as major physiological and pathological mediators in a number of therapeutic areas including inflammation, pain, pyrexia, cancer, and neurological diseases [10▪]. If not inhibited, COX-1 results in an increased inflammatory response and induces early release of proinflammatory cytokines. On the other hand, the role of COX-2 in inflammation is more complex; it has been shown to play a role not only in the pro-inflammatory pathway, but also in reducing inflammation and proinflammatory cytokines release [11▪], and this may explain some of the differences emerged in study findings. However, data on the role of PGE2 as an anti-inflammatory mediator seem insufficient to draw clear conclusions. The data indicating the anti-inflammatory impact of PGE2 comes from studies on macrophage differentiation, which mostly come from studies on mice and should be further confirmed on human material [12]. The need for further research in this area is indicated.

FIGURE 1.

The inflammatory cascade and anti-inflammatory drugs.

Inflammation starts as the body's physiological response to tissue damage caused by infection. As inflammation progresses, various cells are activated by a signaling network and attracted to the inflamed tissue. This process involves many mediators, including growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines. All the cells recruited at the site of damage are still part of the defense mechanism. However, their persistence or prolonged recruitment in the tissue will lead to further tissue damage, worsen inflammation and may make it systemic, regardless of its cause [10▪,13▪].

The NF-κB pathway induces expression of proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1b, IL-6, IL-8, and GM-CSF), chemokines (e.g., CCL2 and CXCL1), and in turn COX-2 and microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 (mPGES-1), resulting in increased PGE2 secretion. While suppressing production of type I (and possibly type III) IFNs, PGE2 further amplifies NF-κB signaling and production of cytokines and chemokines in a positive feedback loop. In monocytes/macrophages, activation of NF-κB and STAT3 mediates production of large amounts of inflammatory cytokines, which contributes to development of cytokine secretion syndrome (the ‘cytokine storm’), chemokines that recruit monocytes and neutrophils, inflammatory biomarkers (e.g., SAAs, CPR, and D-dimer), and PGE2. Here, PGE2 again represses IFN-induced expression of immune serum globulins, contributing to the delay of viral clearance. Importantly, PGE2 influences NF-κB-dependent monocyte/macrophage cytokine production in a context-dependent manner. PGE2 differentially regulates platelet aggregation via different receptors associated with inflammation and thrombosis. PGE2 also downregulates IFN-γ production and cytotoxicity of NK and CD8 T cells that kill cells infected with virus but promotes differentiation of proinflammatory Th17 and Th1 cells, the chief cellular sources of the cytokine storm at late stages of viral infection. NSAIDs, by inhibiting the activity of COX2, reduce the synthesis of PGE2 with evident benefits in the progression of the infectious disease.

COX1 and COX2 have thus crucial effects on the host immune response to viral infection. In particular, PGE2 produced by COX2 plays a critical role, through the regulation of the expression levels of many serum proteins, playing an important role in systemic inflammation and in alveolar pneumonia and interstitial pneumonia of viral origin. PGE2 was shown to have a major effect on pro-inflammatory cytokines and, which is even more important, its inhibition does not attenuate the immune response; on the contrary, its inhibition promotes viral clearance against viral diseases (Fig. 1) [14▪,15].

Altogether, the above observations indicate that it is crucial to modulate COX activity to the right extent and in the right time window to control inflammation in infections. The timing of the cytokine storm in respiratory infections also support this conclusion, given that a cytokine storm may occur when a viral infection is accompanied by an aggressive pro-inflammatory response combined with insufficient control of an anti-inflammatory response. This means that, when the acute inflammatory response in airway epithelial cells, with its activation of pro-inflammatory cytokines or chemokines and intense recruitment of inflammatory cells, is not promptly controlled, it may progress to severe inflammation associated with cytokine storm, more serious local tissue damage as well as systemic complications due to passage of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines in the circulation [16,17].

NSAIDs are a class of molecules very widely used to manage fever, pain, acute and chronic inflammatory conditions, which work through the inhibition of cyclooxygenase enzymes. In viral infections and influenza in particular, overexpression of COX2 and clinical benefits of NSAIDs have been demonstrated [18–22]. A more recent cohort study of adult patients hospitalized with influenza or influenza pneumonia concluded that the short-term use of NSAIDs was not associated with 30-day intensive care unit admission or death [23].

THE ROLE OF NSAIDS IN VIRAL ACUTE RESPIRATORY TRACT INFECTIONS

By targeting COX isoforms, NSAIDs affect the production of proinflammatory cytokines, as well as some intracellular signaling pathways in inflammatory cells potentially preventing the damage caused by cytokine storms and hyperinflammatory states associated with viral infections [24▪▪]. The inhibition of COX by NSAIDs leads to clinically relevant benefits: in addition to the reduction of inflammatory symptoms, NSAIDs have shown, if used promptly in the early phase of the infection, to have the potential of inhibiting disease progression towards complications and hospitalizations [25,26]. NSAIDs are typically divided into groups based on their chemical structure (Table 1) and selectivity (Table 2) [27].

Table 1.

Classification of NSAIDs based on chemical structure

| Group | Drugs |

| Acetic acids | Ketorolac, diclofenac, aceclofenac, indomethacin |

| Acetylated salicylates | Aspirin |

| Anthranilic acids | Meclofenamate, mefenamic acid |

| Diarylheterociles | Celecoxib, etoricoxib |

| Enolic acids | Piroxicam, meloxicam, tenoxicam |

| Nonacetylated salicylates | Diflunisal |

| Propionic acids | Flurbiprofen, ibuprofen, ketoprofen, naproxen |

| Pyrazolone derivatives | Phenylbutazone, oxyphenbutazone |

| Sulphonanilides | Nimesulide |

Table 2.

Classification of the most common NSAIDs considering the selective inhibition of cyclooxygenase enzymes [27]

| COX1 IC50 (μmol/l) |

WBA-COX2 IC50 (μmol/l) |

|

| ASA | 1.7 | >100 |

| Diclofenac | 0.075 | 0.038 |

| Ketorolac | 0.00019 | 0.086 |

| Ibuprofen | 7.6 | 7.2 |

| Ketoprofen | 0.047 | 2.9 |

| Naproxen | 9.3 | 28 |

| Nimesulide | 10 | 1.9 |

| Paracetamolo | >100 | 49 |

WBA, human whole blood assay.

The immune modulatory effects of NSAIDs

In cellular and animal models, NSAIDs have been shown to have immune modulatory effects through the inhibition of prostanoid synthesis, thus affecting the levels of various cytokines. These immune-modulating effects have shown to potentially impact outcomes in various clinical conditions and on various organ systems. However, in randomized clinical studies, the immune-modulatory effects are much less evident. This may be related to high heterogeneity and genetic variances among patients, the use of different concomitant medications, and the presence of comorbidities [28▪].

The role of NSAIDs in viral infections became particularly relevant during the COVID-19 pandemics, at the beginning of which concerns emerged that NSAIDs could increase susceptibility to infection or aggravate the disease. NSAIDs were found to cause more prolonged illness or complications when taken during respiratory tract infections [29–31]. It was reported that individuals assuming NSAIDs for fever or nonrheumatologic pain during the early stages of infection had an increased risk of severe bacterial superinfection [32,33]. It was hypothesized that that NSAIDs may possibly inhibit the host immune reactions against coronavirus replication and enhance the proinflammatory cytokine storm observed in lungs of COVID-19 patients by activation of inflammatory macrophages [34]. However, over time, epidemiological studies have suggested that exposure to NSAIDs did not increase the risk of having SARS-CoV-2 infection or the severity of COVID-19 disease, and that NSAID use might produce benefits, by reducing the risk of development of severe disease in COVID-19 patients, although results were not always fully clear [35,36].

The risks and benefits of NSAID administration should be weighed individually, taking into account the dosage and duration of treatment, which undoubtedly play a role. In these last years, extensive evidence has been accumulated – including experimental research, observational clinical studies, randomized clinical trials, and meta-analyses – that now confirms that NSAIDs are not associated with increased susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2, nor with worsening of COVID-19, and do not impair the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccinations. Therefore, recent reviews conclude that there is no basis to recommend limiting the use of NSAIDs [12,24▪▪,37▪▪,38]. In a large retrospective, multicenter cohort of inpatients diagnosed with COVID-19 from 1 March to 17 April 2020, 466 out of 1305 patients (35.7%) had assumed NSAIDs. Interestingly, patients using NSAIDs prior to hospitalization showed lower odds of mortality [odds ratio (OR) 0.55, 95% confidence interval (95% CI) 0.39–0.78] on multivariate regression analysis (OR: 0.56, 95% CI: 0.40–0.82), suggesting a protective effect on COVID-19 mortality [39].

TOLERABILITY OF NSAIDS

NSAIDs also are associated with side effects, strictly related to their effect of prostaglandin inhibition, which include gastrointestinal, renal, and cardiovascular effects. NSAID hypersensitivity is also to be taken into account, considering that the risk of cross-reactivity to COX-2 inhibitors varies by NSAID hypersensitivity phenotype. The most common side effects of NSAIDs are mild gastrointestinal events such as dyspepsia, heartburn, and nausea, mainly limited to the upper gastrointestinal tract [40,41]. The gastrointestinal side effects have been shown to be effectively controlled by various gastro-duodenal-protective approaches. Some benefits in reducing upper gastrointestinal disturbances have been claimed for enteric-coated NSAIDs; however, they have been shown to carry an increased risk of distal gastrointestinal toxicity. Other pharmaceutical technique approaches, such as certain forms of salification, have demonstrated protective effects resulting from pharmacokinetic improvements as well as better local tolerability. A typical example is the salification of ketoprofen with lysine that exerts a gastroprotective effect due to its specific ability to counteract the NSAIDS-induced oxidative stress and upregulate gastroprotective proteins [42].

The risk of developing renal adverse effects does not exceed the 1–5% of NSAID users and largely depends on dose and duration of therapy; acute forms of renal damage are usually reversible [43]. The risk of cardiovascular complications has been associated with NSAIDs since their introduction but has been highlighted since the emergence of COXIBs and the subsequent withdrawal of rofecoxib. The simple hypothesis is that the selective action of coxibs on COX2 increases the thrombotic risk due to failure to inhibit COX1, thus increasing the production of thromboxanes. Nonselective NSAIDs with a powerful but balanced action on COX1 and COX2, such as ketoprofen, have a good anti-inflammatory activity associated with better cardiovascular tolerability profile. However, this theory of balanced versus unbalanced COX inhibition, although very likely, is debated because nonselective NSAIDs, such as diclofenac, have also been associated with increased cardiovascular risk [44▪].

Two meta-analyses of randomized trials reported that both selective and nonselective COX2 inhibitors were associated with an increased risk of serious vascular ischaemic events, predominantly myocardial infarction. Myocardial failure was associated with etoricoxib, lumiracoxib, and rofecoxib as well as diclofenac and ibuprofen but not with naproxen [45,46].

These findings suggest that mechanisms other than COX2/COX1 selectivity may be implicated in cardiovascular toxicity. Interestingly, a recent study reports that diclofenac but not ketoprofen appears toxic to cardiac cells, despite the two drugs having comparable COX2/COX1 activity. Despite both drugs inducing an increase in ROS production, only diclofenac exposure shows a decrease of mitochondrial membrane potential decreasing in turn the proteasome 26S DC, leading to cell death [31]. Confirming this, a large epidemiological study derived from a database among 8.5 million new NSAID users, 79 553 AMI cases were identified. Among the NSAIDs with the greatest risk, in addition to Coxibs (rofecoxib, etoricoxib), we also find ketorolac and diclofenac, while ketoprofen appears to be the widely used drug with the least cardiovascular risk (Table 3) [47]. It could be hypothesized that NSAIDs derived from acetic acid have a greater cardiovascular risk.

Table 3.

| ASA | Diclofenac | Ibuprofen | Ketoprofen lysine salt | Naproxen | Nimesulide | |

| Antiinflammatory effect | +a | ++ | + | ++ | + | ++ |

| Analgesic effect | +a | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Antipyretic effect | ++a | + | ++ | ++ | + | + |

| Antiplatelet effect | +++ | + | -/+ | ++ | ++ | - |

| Liposolubility | + | -/+ | +++ | + | + | |

| GI tolerability | + | + | + | ++ | + | ++ |

| CV safety | ++ | -/+ | + | +++ | ++ | + |

| Possible co-administration with low-dose ASA | NA | yes | no | yes | no | no |

| Hepatic safety | + | - | + | + | + | - |

High dose; - very low, -/+ low, + medium, ++ high, +++ very high.

Anyway, gastrointestinal and renal side effects of NSAIDs are dose and duration-dependent. The acute administration required to control early inflammation in viral ARTIs is not likely to induce the toxicity of prolonged treatment. However, considering the toxicokinetic mechanism of NSAIDs, it must be admitted that a short treatment, as happens in infections, may not induce serious gastrointestinal problems but may induce serious cardiovascular problems. For this reason, good cardiovascular tolerability is very important for NSAIDs, especially in the elderly. Furthermore, different NSAIDs have different tolerability profiles (Table 3). Regarding specifically NSAIDs safety in respiratory infections, as previously mentioned, the wealth of evidence generated during the COVID-19 pandemics overall supports that NSAIDs do not increase susceptibility to infection, nor worsen disease outcomes [37▪▪,38,48▪▪].

CHOICE OF THE NSAID

The choice of the NSAID should be made considering both the pharmacodynamic (mechanism of action and efficacy) and pharmacokinetic (drug interactions and safety) characteristics, as well as the tolerability profile, in relation to the patient and the condition to be treated [49,50▪]. Table 3 summarizes the specific characteristics of the most used NSAIDs in terms of pharmacological activity, drug interactions, and safety.

As regards efficacy, there are most likely no differences between NSAIDs when used at equivalent doses, and, obviously, in the approved indications. However, there are differences in terms of tolerability. From the comparison summarized in Table 3, ketoprofen lysine salt (KLS) emerges as a NSAID with a favorable efficacy and safety profile. Ketoprofen was shown, in several clinical studies, to have the highest ratio between anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects, making it one of the most potent among nonselective NSAIDs [51,52].

Furthermore, from a tolerability point of view, it has been demonstrated that the L-lysine salification adds a gastroprotective effect to the ketoprofen molecule, by specifically counteracting the NSAID-induced oxidative stress and upregulating gastroprotective proteins [42,53].

Given the widespread use of low-dose acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) in cardiovascular prevention, another aspect to be considered in choosing a NSAID is its pharmacodynamic interaction with ASA. It has been shown that ibuprofen, indomethacin, naproxen, and tiaprofenic acid all block the antiplatelet effect of ASA [54], whereas ketoprofen and diclofenac do not interfere [55,56].

CONCLUSION

The inflammatory response plays a pivotal role in the early phase of ARTIs; a correct diagnosis of the etiology and a prompt therapeutic approach with NSAIDs can not only control the symptoms but also manage the pathophysiological mechanisms that may complicate the condition. Moreover, it is very important to choose the most appropriate molecule, based on the patients’ characteristics. In particular in patients at risk of or with cardiovascular diseases, NSAIDs that have been shown to have the most advantageous efficacy/safety profile, such as KLS, should be preferred. Furthermore, a timely intervention with NSAIDs allows early reduction of symptoms to the benefit of the patient and may also limit the inappropriate use of other categories of drugs that might not be indicated, such as antibiotics which are useless when viral cause is confirmed and whose inappropriate use is responsible for the development of resistance.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Renata Perego, MD, for her help in drafting the manuscript.

Financial support and sponsorship

The study was supported by Dompé Farmaceutici SPA through unconditioned grants.

Dompé Farmaceutici SPA did not have any role in design, planning, or execution of the review.

Conflicts of interest

M.B. has received research grants and/or advisor/consultant and/or Speaker/chairman from Advanz, Angelini, Bayer, Biomerieux, Cidara, Gilead, Menarini, Mundipharma, MSD, Pfizer, Shionogi.

M.A. has received honoraria from Gilead, Astra Zeneca, GSK, and Pfizer for participation in Advisory Board.

P.S. has received research grants from AstraZeneca, Edmondpharma, GSK, Air Liquide, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi Farmaceutici, Pfizer, and fees for lecturing, participation on advisory boards and consultancy from AstraZeneca, Dompé, Berlin-Chemie, Zambon Italia, Zambon Brasil, Boehringer Ingelheim, Guidotti, Edmondpharma, Sanofi, GSK, Gilead, Neopharmed. Valeas, Sanofi.

F.S. has received research grants from Pfizer, Chiesi Farmaceutici and fees for lecturing, participation on advisory boards and consultancy from Bayer, Dompé, Sanofi, GSK, Gilead, Firma, Angelini.

REFERENCES AND RECOMMENDED READING

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

▪ of special interest

▪▪ of outstanding interest

REFERENCES

- 1.Shahan B, Barstow C, Mahowald M. Respiratory conditions: upper respiratory tract infections. FP Essent 2019; 486:11–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Santus P, Radovanovic D, Gismondo MR, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus burden and risk factors for severe disease in patients presenting to the emergency department with flu-like symptoms or acute respiratory failure. Respir Med 2023; 218:107404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuchar E, Miśkiewicz K, Nitsch-Osuch A, Szenborn L. Pathophysiology of clinical symptoms in acute viral respiratory tract infections. Adv Exp Med Biol 2015; 857:25–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marseglia GL, Veraldi D, Ciprandi G. Study Group on Respiratory Infections in Adolescents. Ketoprofen lysine salt treatment in adolescents with acute upper respiratory infections: a primary-care experience. Minerva Pediatr (Torino) 2023; 75:890–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forchette L, Sebastian W, Liu T. A comprehensive review of COVID-19 virology, vaccines, variants, and therapeutics. Curr Med Sci 2021; 41:1037–1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6▪.Xiong Y, Liu Y, Cao L, et al. Transcriptomic characteristics of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and peripheral blood mononuclear cells in COVID-19 patients. Emerg Microbes Infect 2020; 9:761–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Present and future of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

- 7.Pedersen SG, Ho YC. SARS-CoV-2: a storm is raging. J Clin Invest 2020; 130:2202–2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pinto R, Herold S, Cakarova L, et al. Inhibition of influenza virus-induced NF-kappaB and raf/MEK/ERK activation can reduce both virus titers and cytokine expression simultaneously in vitro and in vivo. Antiviral Res 2011; 92:45–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9▪▪.Bacchi S, Palumbo P, Sponta A, Coppolino MF. Clinical pharmacology of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a review. Antiinflamm Antiallergy Agents Med Chem 2012; 11:52–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Interesting overview of NSAIDs pharmacology.

- 10▪.Megha KB, Joseph X, Akhil V, Mohanan PV. Cascade of immune mechanism and consequences of inflammatory disorders. Phytomedicine 2021; 91:153712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Review covering the importance of inflammatory responses and the significance of cytokines in inflammation.

- 11▪.Chamkouri N, Absalan F, Koolivand Z, Yousefi M. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in viral infections disease, specially COVID-19. Adv Biomed Res 2023; 12:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The article clarifies the fundamental yet contradictory roles of COX-1 and COX-2 in the host immune response to viral infection.

- 12.Kulesza A, Paczek L, Burdzinska A. The role of COX-2 and PGE2 in the regulation of immunomodulation and other functions of mesenchymal stromal cells. Biomedicines 2023; 11:445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13▪.Asa’ad F, Cho YD, Larson L. Editorial: on the inflammatory cascade-from bacteria through the epithelium to the connective tissue. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022; 12:936833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Important editorial on how bacteria influence the inflammatory cascade and the reaction of different tissues to their pathogenic effects.

- 14▪.Robb CT, Goepp M, Rossi AG, Yao C. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, prostaglandins, and COVID-19. Br J Pharmacol 2020; 177:4899–4920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Comprehensive survey of the potential roles that NSAIDs and PGs may play during SARS-CoV-2 infection.

- 15.Wright WR, Kirkby NS, Galloway-Phillipps NA, et al. Cyclooxygenase and cytokine regulation in lung fibroblasts activated with viral versus bacterial pathogen associated molecular patterns. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat 2013; 107:4–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hussell T, Goulding J. Structured regulation of inflammation during respiratory viral infection. Lancet Infect Dis 2010; 10:360–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tisoncik JR, Korth MJ, Simmons CP, et al. Into the eye of the cytokine storm. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2012; 76:16–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu L, Li R, Pan Y, et al. High-throughput screen of protein expression levels induced by cyclooxygenase-2 during influenza a virus infection. Clin Chim Acta 2011; 412:1081–1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee SM, Gai WW, Cheung TK, Peiris JS. Antiviral effect of a selective COX-2 inhibitor on H5N1 infection in vitro. Antiviral Res 2011; 91:330–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee SM, Gai WW, Cheung TK, Peiris JS. Antiviral activity of a selective COX-2 inhibitor NS-398 on avian influenza H5N1 infection. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2011; 5: (Suppl 1): 230–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee S, Cheung CY, Nicholls JM, et al. Hyperinduction of cyclooxygenase-2-mediated proinflammatory cascade: a mechanism for the pathogenesis of avian influenza H5N1 infection. J Infect Dis 2008; 198:525–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee MY, Cheung CY, Peiris JS. Role of cyclooxygenase-2 in H5N1 viral pathogenesis and the potential use of its inhibitors. Hong Kong Med J 2013; 19: (Suppl 4): 29–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lund LC, Reilev M, Hallas J, et al. Association of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and adverse outcomes among patients hospitalized with influenza. JAMA Netw Open 2020; 3:e2013880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24▪▪.Marcianò G, Muraca L, Rania V, Gallelli L. Ibuprofen in the management of viral infections: the lesson of COVID-19 for its use in a clinical setting. J Clin Pharmacol 2023; 63:975–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Interesting review of the role of NSAIDs in the management of viral symptoms.

- 25.Fazio S, Bellavite P, Zanolin E, et al. Retrospective study of outcomes and hospitalization rates of patients in Italy with a confirmed diagnosis of early COVID-19 and treated at home within 3 days or after 3 days of symptom onset with prescribed and non-prescribed treatments between November 2020 and August 2021. Med Sci Monit 2021; 27:e935379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hunt CM, Efird JT, Redding TS 4th, et al. Medications associated with lower mortality in a SARS-CoV-2 positive cohort of 26,508 Veterans. J Gen Intern Med 2022; 37:4144–4152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Warner TD, Giuliano F, Vojnovic I, et al. Nonsteroid drug selectivities for cyclo-oxygenase-1 rather than cyclo-oxygenase-2 are associated with human gastrointestinal toxicity: a full in vitro analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999; 96:7563–7568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28▪.Bosch DJ, Nieuwenhuijs-Moeke GJ, van Meurs M, et al. Immune modulatory effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the perioperative period and their consequence on postoperative outcome. Anesthesiology 2022; 136:843–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Although in clinical conditions different from respiratory infections, the article reviews comprehensively the immune modulatory effects of NSAIDs.

- 29.Basille D, Plouvier N, Trouve C, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may worsen the course of community-acquired pneumonia: a cohort study. Lung 2017; 195:201–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Voiriot G, Philippot Q, Elabbadi A, et al. Risks related to the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in community-acquired pneumonia in adult and pediatric patients. J Clin Med 2019; 8:786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stuart B, Venekamp R, Hounkpatin H, et al. NSAID prescribing and adverse outcomes in common infections: a population-based cohort study. BMJ Open 2024; 14:e077365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Micallef J, Soeiro T, Jonville-Béra A. French Society of Pharmacology, Therapeutics (SFPT). Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, pharmacology, and COVID-19 infection. Therapie 2020; 75:355–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sodhi M, Khosrow-Khavar F, FitzGerald JM, Etminan M. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the risk of pneumonia complications: a systematic review. Pharmacotherapy 2020; 40:970–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan. China. JAMA Intern Med 2020; 180:934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lund LC, Kristensen KB, Reilev M, et al. Adverse outcomes and mortality in users of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2: A Danish nationwide cohort study. PLoS Med 2020; 17:e1003308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.von Philipsborn P, Biallas R, Burns J, et al. Adverse effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in patients with viral respiratory infections: rapid systematic review. BMJ Open 2020; 10:e040990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37▪▪.Laughey W, Lodhi I, Pennick G, et al. Ibuprofen, other NSAIDs and COVID-19: a narrative review. Inflammopharmacology 2023; 31:2147–2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Extensive examination of the data relating to the effects of NSAIDs in COVID-19.

- 38.Prada L, D Santos C, Baião RA, et al. Risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 severity associated with exposure to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Pharmacol 2021; 61:1521–1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Imam Z, Odish F, Gill I, et al. Older age and comorbidity are independent mortality predictors in a large cohort of 1305 COVID-19 patients in Michigan, United States. J Intern Med 2020; 288:469–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee MW, Katz PO. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, anticoagulation, and upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Clin Geriatr Med 2021; 37:31–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sostres C, Gargallo CJ, Arroyo MT, Lanas A. Adverse effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs, aspirin and coxibs) on upper gastrointestinal tract. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2010; 24:121–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brandolini L, d’Angelo M, Antonosante A, et al. Differential protein modulation by ketoprofen and ibuprofen underlines different cellular response by gastric epithelium. J Cell Physiol 2018; 233:2304–2312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harirforoosh S, Jamali F. Renal adverse effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2009; 8:669–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44▪.Schjerning AM, McGettigan P, Gislason G. Cardiovascular effects and safety of (nonaspirin) NSAIDs. Nat Rev Cardiol 2020; 17:574–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Review of the current evidence on the cardiovascular safety of NSAIDs.

- 45.Kearney PM, Baigent C, Godwin J, et al. Do selective cyclo- oxygenase-2 inhibitors and traditional non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs increase the risk of atherothrombosis? Meta- analysis of randomized trials. BMJ 2006; 332:1302–1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trelle S, Reichenbach S, Wandel S, et al. Cardiovascular safety of nonsteroidal anti inflammatory drugs: network meta-analysis. BMJ 2011; 342:c7086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Masclee GMC, Straatman H, Arfè A, et al. Risk of acute myocardial infarction during use of individual NSAIDs: a nested case-control study from the SOS project. PLoS One 2018; 13:e0204746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48▪▪.Moore N, Bosco-Levy P, Thurin N, et al. NSAIDs and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Saf 2021; 44:929–938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Review and meta-analysis on the theoretical risks of NSAIDs in SARS-CoV-2.

- 49.Kucharz EJ, Szántó S, Ivanova Goycheva M, et al. Endorsement by Central European experts of the revised ESCEO algorithm for the management of knee osteoarthritis. Rheumatol Int 2019; 39:1117–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50▪.Bassetti M, Giacobbe DR, Bruzzi P, et al. Italian Society of Antiinfective Therapy and the Italian Society of Pulmonology (SIP). Clinical management of adult patients with COVID-19 outside intensive care units: guidelines from the Italian Society of Anti-Infective Therapy (SITA) and the Italian Society of Pulmonology (SIP). Infect Dis Ther 2021; 10:1837–1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Latest guidelines on the clinical management of COVID-19 patients outside the ICUs.

- 51.Veys EM. 20 years’ experience with ketoprofen. Scand J Rheumatol Suppl 1991; 90:1–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Varrassi G, Alon E, Bagnasco M, et al. Towards an effective and safe treatment of inflammatory pain: a Delphi-guided expert consensus. Adv Ther 2019; 36:2618–2637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cimini A, Brandolini L, Gentile R, et al. Gastroprotective effects of L-lysine salification of ketoprofen in ethanol-injured gastric mucosa. J Cell Physiol 2015; 230:813–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gladding PA, Webster MW, Farrell HB, et al. The antiplatelet effect of six nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and their pharmacodynamic interaction with aspirin in healthy volunteers. Am J Cardiol 2008; 101:1060–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saxena A, Balaramnavar VM, Hohlfeld T, Saxena AK. Drug/drug interaction of common NSAIDs with antiplatelet effect of aspirin in human platelets. Eur J Pharmacol 2013; 721:215–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hohlfeld T, Saxena A, Schrör K. High on treatment platelet reactivity against aspirin by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs--pharmacological mechanisms and clinical relevance. Thromb Haemost 2013; 109:825–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]