Abstract

Background:

The endothelial glycocalyx layer (EGL) is a complex meshwork of glycosaminoglycans and proteoglycans that protect the vascular endothelium. Cleavage or shedding of EGL-specific biomarkers, such as hyaluronic acid (HA) and syndecan-1 (SDC-1, CD138) in plasma, have been shown to be associated with poor clinical outcomes. However, it is unclear whether levels of circulating EGL biomarkers are representative of the EGL injury within the tissues. The objective of the present feasibility study was to describe a pathway for plasma and tissue procurement to quantify EGL components in a cohort of surgical patients with intra-abdominal sepsis. We sought to compare differences between tissue and plasma EGL biomarkers and to determine whether EGL shedding within the circulation and/or tissues correlated with clinical outcomes.

Methods:

This was a prospective, observational, single-center feasibility study of adult patients (N = 15) with intra-abdominal sepsis, conducted under an approved institutional review boards. Blood and resected tissue (pathologic specimen and unaffected peritoneum) samples were collected from consented subjects at the time of operation and 24–48 hours after surgery. Endothelial glycocalyx layer biomarkers (i.e., HA and SDC-1) were quantified in both tissue and plasma samples using a CD138 stain and ELISA kit, respectively. Pairwise comparisons were made between plasma and tissue levels. In addition, we tested the relationships between measured EGL biomarkers and clinical status and patient outcomes.

Results:

Fifteen patients with intra-abdominal sepsis were enrolled in the study. Elevations in EGL-specific circulating biomarkers (HA, SDC-1) were positively correlated with postoperative SOFA scores and weakly associated with resuscitative volumes at 24 hours. Syndecan-1 levels from resected pathologic tissue significantly correlated with SOFA scores at all time points (R = 0.69 and P < 0.0001) and positively correlated with resuscitation volumes at 24 hours (R = 0.41 and P = 0.15 for t = 24 hours). Tissue and circulating HA and SDC-1 positively correlated with SOFA >6.

Conclusions:

Elevations in both circulating and tissue EGL biomarkers were positively correlated with postoperative SOFA scores at 24 hours, with resected pathologic tissue EGL levels displaying significant correlations with SOFA scores at all time points. Tissue and circulating EGL biomarkers were positively correlated at higher SOFA scores (SOFA > 6) and could be used as indicators of resuscitative needs within 24 hours of surgery. The present study demonstrates the feasibility of tissue and plasma procurement in the operating room, although larger studies are needed to evaluate the predictive value of these EGL biomarkers for patients with intra-abdominal sepsis.

Keywords: Glycocalyx, sepsis, peritoneum tissue, hyaluronan, syndecan-1

INTRODUCTION

Sepsis is defined as a life-threatening spectrum of organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection (1). Despite improvements in management of the septic patient, hospital mortality remains an estimated 27% overall and 42% for those treated in the intensive care unit (ICU) setting with 5 million sepsis-related deaths annually worldwide (2,3). Sepsis has been identified as the most expensive condition in the hospital, with associated aggregate costs for all hospitalizations in the United States of more than $24 billion (2,4). While goal-directed care in the forms of treatment guidelines and early-detection scoring systems have made strides in the care of the septic patient, the management and outcomes of the disease state remain heterogeneous because of incompletely understood pathogenesis (5,6).

Recent investigation has demonstrated that microvascular endothelial injury is necessary for the development of end-organ failure and subsequent poor outcomes in critically ill patients (7–10). The endothelial glycocalyx layer (EGL) is a complex meshwork of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), including hyaluronic acid (HA), heparan sulfate, and chondroitin sulfate, and proteoglycans, such as syndecan-1 (SDC-1 or CD138), that protects the vascular endothelial cell layer (Fig. 1) (11). Under homeostatic conditions, the EGL participates in regulation of vasomotor tone, maintenance of blood fluidity, exchange of circulating components across the cell membrane, immunity, and angiogenesis (12). During states of shock, damage to the EGL is inflicted by elevated circulating catecholamines, cytokines, and tissue proteases, resulting in breakdown of the glycocalyx and capillary leakage between intercellular tight junctions (13,14). Elevations in EGL-specific circulating biomarkers, such as SDC-1 and HA, within the first 24 hours of sepsis have been associated with increased resuscitative volumes, intubation, organ failure, and mortality (15,16).

Fig. 1. Representation of the EGL containing HA anchored to its cell surface receptor, CD44, and syndecan-1 (SDC-1, CD138), with associated heparan sulfate and chondroitin sulfate, during physiologic and pathophysiologic conditions.

HA and SDC-1 are cleaved by HYA, heparanases, and MMP during inflammation or mechanically disrupted during tissue injury, resulting in EGL component shedding into the blood stream (created on Biorender.com). EGL, endothelial glycocalyx layer; HA, hyaluronic acid; HYA, hyaluronidases (HYA); MMP, matrix metalloproteinases.

While the abdomen is the second most common source for sepsis behind the lung, it has the highest associated mortality (17,18). Patients with intra-abdominal infection are more likely to develop septic shock, coagulation failure, and renal failure compared with patients with respiratory infection (19). Furthermore, EGL degradation is more pronounced in patients with nonpulmonary versus pulmonary sepsis (20). To better understand the behavior of the EGL at the local and systemic levels during infection, we collected tissue and plasma EGL biomarkers in a cohort of patients with intra-abdominal sepsis. The objectives of the present feasibility study were (1) to demonstrate a pathway for procurement of human tissue and plasma, (2) compare tissue and plasma EGL biomarkers, and (3) determine whether EGL shedding at the tissue and plasma levels correlated with clinical outcomes in intra-abdominal sepsis.

METHODS

Study design

We performed a prospective observational feasibility study at a single academic center, Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center (AH-WFBMC), Winston-Salem, North Carolina. This study was approved by the internal review board at WFBMC (IRB# 00057321). Patients were prospectively enrolled in this study from May 2019 to May 2022. A pause in study enrollment occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic (March 2020–2021). Given the critical care state of these patients, consent was obtained by a member of the research team (S.P.C, R.D.A., or A.M.N.) under a partial waiver of informed consent, with the expectation that consent would be obtained within 72 hours of study enrollment. Written informed consent was obtained from all enrolled patients or their legally appointed representative as soon as possible. No specimen analysis was performed before obtaining written informed consent. Patient data were deidentified and only the subject numbers were used to label the data. Any collected patient identifying information corresponding to the unique study identifier was stored separately from the data, with access limited to designated study personnel.

Inclusion criteria were adult patients 18 years or older who met criteria for sepsis (≥2 SIRS criteria with an intra-abdominal source of infection) or septic shock (sepsis with requirement of vasopressor to maintain mean arterial pressure ≥65) and required operation for their disease (21). Intra-abdominal sources included appendicitis, diverticulitis, cholecystitis, ascending cholangitis, hepatic abscess, mesenteric ischemia, infectious colitis, peptic ulcer disease, and esophageal perforation. Patients were admitted through the Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center emergency department, directly transferred from an outside emergency department or inpatient-to-inpatient transfer from a referring facility. Patients younger than 18 years, immunosuppressed patients (i.e., posttransplantation, HIV, hepatitis, chronic steroid usage, rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis), major operation on current admission before enrollment, complication of previous major operation within 30 days, and concurrent treatment for infection other than abdominal sepsis were excluded.

Biospecimen and data collection

A total of 10 to 15 mL of blood was collected in citrated, EDTA, and/or heparin blood collection tubes from each patient at the time of operation, after induction of general anesthesia. Similarly, tissue specimens were collected from each patient, which comprised a piece of the excised pathologic specimen (approximately 2 cm in diameter, seromuscular biopsy of the excised hollow viscous) along with an additional similarly sized healthy-appearing peritoneal biopsy remote from the pathologic specimen at the time of operation. An additional blood sample was taken 24 to 48 hours after the operation. Tissue specimen collection was performed in the operating room by authors S.P.C, R.D.A., or A.M.N. for all patients. Both tissue specimens were placed in labeled 50-mL tubes containing 10% neutral buffered formalin fixative and placed in a study-designated receptacle for pickup by a laboratory technician within 24 to 48 hours from the Wake Forest Tumor Tissue Pathology Resource Shared Resource Laboratory for later immunohistochemical staining of key glycocalyx markers.

Blood samples were then centrifuged to isolate plasma, buffy coat, and RBC, and subsequently stored at −80°C, until further analysis. Quantitation of key glycocalyx markers, namely syndecan-1 (SDC-1, Abcam ab46506 kit, Cambridge, MA) and hyaluronic acid (HA, K-1200 kit, Echelon Biosciences, Inc) were completed using commercially available ELISA kits.

From a review of participant medical records, we obtained the following: date of operation, operative surgeon, diagnosis, age, sex, race, body mass index, Glasgow Coma Scale on admission, type of operation, vital signs at the time of operation and 24 to 48 hours post-operatively, vasopressor requirements at 24 to 48 hours postoperatively, fluid resuscitative volumes 24 to 48 hours postoperatively, ICU days (or ICU free days), ventilator days (or ventilator free days), mortality, complications, sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score, and Charlson Comorbidity Index.

Histology and tissue processing

Tissue samples that were collected in the operating room were placed immediately in 10% neutral buffered formalin and fixed for 24 to 48 hours. The fixed tissue was then placed in an automated processor using a 12-hour schedule, embedded in paraffin wax, and sections were cut at 5 μm thick on Superfrost charged slides. A hematoxylin-eosin stain was performed on an automatic stainer using Epredia 7211 Hematoxylin and Epredia 7111 Eosin-Y. A second slide was sectioned at 5 μm for CD-138 staining in the Clinical Molecular Diagnostics lab.

CD138 protocol

Samples were stained for CD138 using the Leica Bond 3 Immunostainer. The detection system was the Polymer Refine DAB Detection kit (cat# DS9800) using Leica Epitope Retrieval 1 (cat# AR9961) for 20 minutes. The CD138 antibody is from CellMarque (cat# 138 M-18) clone B-A38, predilute. CD138-positive cells were quantified by a blinded pathologist at high-power field (HPF, 400×, 0.237 mm2).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs), and count data are presented as counts with proportions. To compare circulating versus tissue levels of EGL, we performed pairwise correlations. To determine the associations between EGL biomarker levels and patient outcomes, we performed linear and logistic regressions, while adjusting for age, sex, and body mass index. Significance (α) was set at the 0.05 level. Statistical analyses were conducted using STATA (version 12.1, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

This feasibility study included 15 emergency general surgery patients with a median age of 64 years (IQR, 59.5–72 years), body mass index 29.7 kg/m2 (IQR, 25.8–37 kg/m2), and 20% female (12 males, 3 females; Table 1). The median Charleson Comorbidity Index was 4 (IQR, 1.25–6). All patients underwent exploratory laparotomy, most commonly for bowel resection due to a perforated colon (approximately 33%). The variety of sources for intra-abdominal sepsis are listed in Table 2. All patients that met inclusion criteria were consented within the stipulated timeline and contributed data to the study.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Age, y | 64 (59.5–72) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 12(80%) |

| Female | 3 (20%) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 29.7 (25.8–37) |

| Charlson comorbidity index | 4 (1.3–6) |

| Hospital LOS, d | 13 (10–18.5) |

| ICU LOS, d | 7 (4.3–12.5) |

| Ventilator days | 2 (0–4) |

| Mortality. % | 3 (20%) |

Data are presented as group counts (n, %) or median (IQR).

Table 2.

A list of sources of intra-abdominal sepsis encountered during the study

| Sources | n (%) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Perforated colon | 5 (33.3%) |

| Incarcerated hernia | 3 (20%) |

| Mesenteric ischemia | 2 (13.3%) |

| Bowel obstruction | 2 (13.3%) |

| Perforated gastric ulcer | 1 (7.7%) |

| Esophageal perforation | 1 (7.7%) |

| Perforated appendicitis | 1 (7.7%) |

Clinical outcomes

Three patients died during their admission (20%), and one was dispositioned to hospice. The median hospital length of stay (LOS) was 13 days (IQR, 10–18.5 days) and ICU LOS 7 days (IQR, 4.25–12.5 days). Patients required mechanical ventilation for a median of 2 days (IQR, 0–4 days) postoperatively. Median vital signs at the time of operation (i.e., T = 0, OR), 24 hours post-operatively and 48 hours postoperatively are summarized in Table 3. The number of patients requiring vasopressor decreased over the post-operative 48 hours (5 vs. 2). The median norepinephrine equivalents were 0.04 (IQR, 0.04–0.14) 24 hours postoperatively and 0.1 (IQR, 0.06–0.14) 48 hours postoperatively. Patients received a median of 3942.3 mL of fluid volume resuscitation (IQR, 2351.8–3942.3) by 24 hours postoperatively with an additional median 3318.9 mL (IQR, 1048.4–4871.6 mL) by 48 hours postoperatively. The SOFA scoring revealed a median of 4 (IQR, 2–7) at the time of operation, 4 (IQR, 3–5) 24 hours postoperatively, and 2.5 (IQR, 2–4) 48 hours post-operatively.

Table 3.

Summary of patient vital signs at the time of operation (t = 0, OR), 24 and 48 hours after operation

| OR | 24 h | 48 h | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Vital signs | |||

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 115 (106–135) | 127 (120–140) | 132 (116–146) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 66 (63–77) | 60 (58–72) | 62 (56–71) |

| Heart rate, beats per min | 112 (96–125) | 97 (86–105) | 96 (91–109) |

| Respiratory rate, breaths per min | 20 (17–23) | 19 (16–22) | 20 (17–25) |

| SpO2, % | 95 (94–98) | 95 (94–97) | 95 (94–98) |

| Temperature, F | 98.5 (97.8–98.7) | 98.9 (97.3–99.1) | 98.5 (98–99) |

| Patients requiring vasopressor | 5 | 2 | |

| Norepinephrine equivalents | 0.04 (0.04–0.14) | 0.1 (0.06–014) | |

| Fluid volume resuscitation, mL | 3,942 (2352–7,412) | 3,319 (1048–4,872) | |

| SOFA score | 4 (2–7) | 4 (3–5) | 2.5 (2–4) |

Data are presented as group counts or median (IQR).

OR, operating room; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

Correlations between circulating and tissue EGL biomarkers

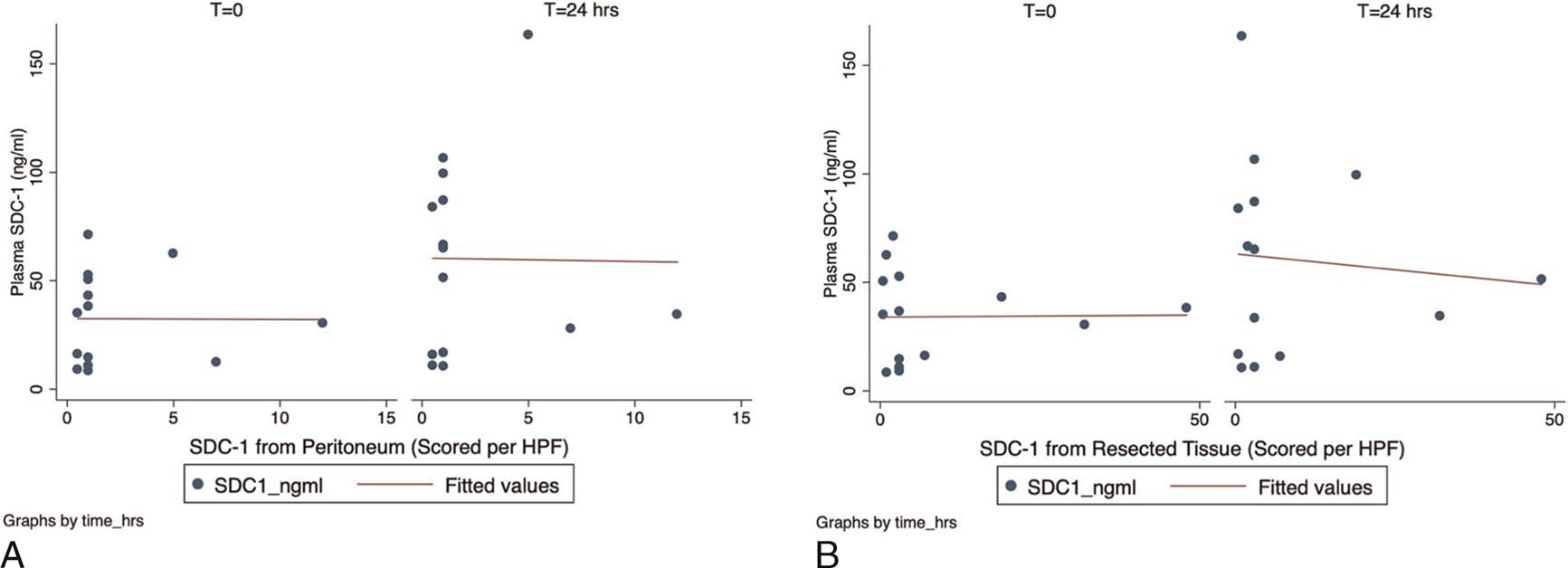

We collected plasma, peritoneum, and resected pathologic tissue from each subject and stained the tissue for SDC-1 (Table 4). To evaluate the relationship between circulating levels of SDC-1 in plasma and tissue levels, we performed pairwise correlations. While circulating SDC-1 levels tended to increase over time, we did not observe significant correlations between plasma and tissue levels (Fig. 2). In fact, the relationship between scored pathology tissue and plasma levels of SDC-1 was very weak throughout all study time points. Interestingly, within the plasma measurements, plasma HA levels were strongly correlated to plasma SDC-1 levels at t = 24 hours after operation (R = 0.5, P = 0.06).

Table 4.

Summary of tissue and EGL biomarker quantification at the time of operation (OR) and 24–48 hours after operation

| Assay | OR | 24–48 h |

|---|---|---|

| CD138 (peritoneum), cells per HPF | 1 (1) | |

| CD138 (pathology), cells per HPF | 3 (1–6) | |

| Hyaluronic acid (plasma), ng/mL | 537.9 (286.7–1032.6) | 423.6 (159.1–733.6) |

| Syndecan-1 (plasma), ng/mL | 35.2 (13.1–46.8) | 51.2 (19.6–85.6) |

CD138 positivity is presented as counts within a high-powered field (400 ×, 0.237 mm2) with IQR.

HPF, high-power field; OR, operating room; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

Fig. 2. Correlations between plasma and tissue levels of SDC-1.

(A) Comparison between plasma SDC-1 levels and peritoneum tissue. Weak correlations are observed. Correlation coefficient (R) is −0.035 at t = 0 and −0.156 at t = 24 hours, P > .9 for both comparisons. (B) Comparison between plasma SDC-1 levels and resected tissue. Correlation coefficient (R) is 0.019 at t = 0 and −0.293 at t = 24 hours, P > 0.7 for both comparisons. No significant correlations between plasma and tissue levels of SDC-1 were observed in patients with intra-abdominal sepsis. While circulating plasma levels of SDC-1 tended to increase at 24 hours, the correlations between tissue and plasma levels remained weak. This suggests that there is minimal overlap between the circulating and local/tissue levels of glycocalyx biomarkers.

Endothelial glycocalyx layer–specific circulating biomarkers and SOFA scoring

We evaluated EGL-specific circulating biomarkers (HA, SDC-1) at the time of operation (T = 0) and 24 hours after operation (T = 24 hours) in the context of SOFA scoring (Fig. 3). Circulating plasma levels of HA and SDC-1 were positively associated with postoperative SOFA scores, and the strength of the association was stronger (approximately 2–3× stronger, R = 0.36–0.35, respectively) at 24 hours. However, this relationship was not statistically significant, possibly because of our relatively small sample size.

Fig. 3. Elevations in EGL-specific circulating biomarkers (HA, SDC-1) were positively correlated with postoperative SOFA scores at 24 hours in intra-abdominal sepsis.

Correlation coefficient (R) for HA versus SOFA scores were 0.11 at t = 0 ( P = 0.69) and 0.36 at t = 24 hours ( P = 0.20). Correlation coefficient (R) for SDC-1 versus SOFA scores were 0.19 at t = 0 ( P = 0.48) and 0.35 at t = 24 hours ( P = 0.23). While the strength of association increased at 24 hours, these correlations were not statistically significant ( P > 0.05), potentially because of our small sample size. EGL, endothelial glycocalyx layer; HA, hyaluronic acid; SOFA, sequential organ failure assessment.

Endothelial glycocalyx layer–specific circulating biomarkers and fluid resuscitative volumes

We next evaluated EGL-specific circulating biomarkers (HA, SDC-1) at the time of operation (T = 0) and 24 hours after operation (T = 24 hours) in the context of fluid resuscitative volumes (Fig. 4). Plasma levels of HA and SDC-1 were weakly associated with postoperative fluid resuscitative volumes at 24 hours. There was a positive correlation between the volume of albumin administered intraoperatively and the SDC-1 level at 24 and 48 hours (R = 0.64, P = 0.01; R = 0.60, P = 0.02). A single patient received blood transfusion and no patients received plasma transfusion.

Fig. 4. Elevations in EGL-specific circulating biomarkers (HA, SDC-1) were weakly correlated with postoperative fluid resuscitative volumes at 24 hours in intra-abdominal sepsis.

Correlation coefficient (R) was 0.12 for HA and resuscitation volume ( P = 0.67) and 0.07 for SDC-1 and resuscitation volumes ( P = 0.79). EGL, endothelial glycocalyx layer; HA, hyaluronic acid.

Correlations in tissue and circulating EGL-specific biomarkers, SOFA scoring

We evaluated the relationship between tissue syndecan-1 (CD138) levels (scored by pathology) and SOFA scores (Fig. 5). Tissue CD138 significantly correlated with SOFA scoring at all time points (R = 0.69, P < 0.0001) and positively correlated with resuscitative volumes at 24 hours (R = 0.41, P = 0.15). At higher SOFA scores (SOFA >6), there seems to be a positive correlation between EGL-specific circulating SDC-1 and resected tissue CD138, such that an individual with a SOFA score >6 has an average 24× higher tissue SDC-1 level than those with lower SOFA scores (0–6).

Fig. 5. (A) Tissue EGL biomarkers (CD138) from resected tissue significantly correlated with SOFA scores at all time points (R = 0.69 and P < 0.0001) and (B) positively correlated with resuscitation volumes at 24 hours (R = 0.41 and P = 0.15 for t = 24 hours).

(C) The correlation coefficient (R) is 0.53 where an individual with a SOFA score >6 has an average 24× higher tissue SDC-1 levels than those with lower SOFA scores (0–6). EGL, endothelial glycocalyx layer; HA, hyaluronic acid; SOFA, sequential organ failure assessment.

DISCUSSION

In this prospective feasibility study, we have demonstrated the appearance of a positive correlation between EGL-specific biomarkers (i.e., CD138) in the pathologic tissues and SOFA scoring of patients with intra-abdominal sepsis. Our data support prior findings in that EGL-specific circulating biomarkers (i.e., HA and SDC-1) were correlated with SOFA scoring at 24 hours. There were no strong correlations between plasma and tissue levels of SDC-1, although a positive relationship may exist in sicker patients (i.e., SOFA>6). These findings have an important impact as they lay the groundwork by which tissue and plasma may be procured in the operating room for characterization of these EGL biomarkers for future observational and interventional investigations with more patients.

The evaluation of the EGL during shock states has been an area of great research interest in recent years. Although the roots of septic shock resuscitation lay with protocolized care and guideline-based management, sepsis remains the most expensive condition in the hospital with a 42% mortality in the critically ill (2,5,22). This has driven interest toward EGL biomarkers as a diagnostic and prognostic opportunity (13). Ostrowski et al. (23) prospectively observed that plasma SDC-1 and soluble thrombomodulin increased with sepsis disease severity, as measured by SOFA, in a large cohort of ICU patients. Furthermore, significantly higher plasma values of SDC-1 and soluble thrombomodulin were observed in nonsurvivors versus survivors (23). These findings are similar to the present study in which circulating and tissue EGL biomarkers correlated in patients with higher disease severity (SOFA scores >6), but not in milder disease. However, circulating and tissue levels of EGL biomarkers were not associated with higher mortality in this cohort, potentially because of the small sample size. This observation raises the possibility of an inflection point, beyond which disease at the tissue level is unrecoverable and progressing down a pathway toward mortality. While organ-level biopsy, in the absence of an abdominal operation, is potentially less feasible, a larger study of intra-abdominal sepsis with criteria directed toward this sicker cohort may demonstrate more rigorous agreement in tissue and plasma values in correlation with disease severity. While therapeutic opportunities for EGL shedding are limited, preclinical data have demonstrated the potential value of plasma transfusion-based resuscitation, informing clinical trial design (24–26).

While abdominal infection constitutes the second-most common cause of hospitalized sepsis, it has the greatest potential for morbidity and mortality (17,19). As observed by Volakli et al. (19), critically ill patients with abdominal infections were more commonly admitted in septic shock and more likely to experience early coagulation and renal failure. A variety of recent preclinical investigations have suggested a causal relationship between prevention of EGL breakdown and mitigation of ensuing sepsis (27). Furthermore, treatment of abdominal sepsis with direct peritoneal resuscitation, or continuous irrigation of the abdomen postoperatively, resulted in decreased SOFA scores, fewer ventilator days, and shorter ICU LOS compared with controls in a randomized trial of critically ill patients (28). The available preclinical and clinical data provide a strong context for the peritoneum as a primary driver of septic shock in association with EGL breakdown. As we have demonstrated in the present study, tissue EGL biomarkers (i.e., CD138) significantly correlate to SOFA scores and may be associated with resuscitative volumes at 24 hours. The positive correlation between albumin transfusion volumes and SDC-1 may simply be a marker of illness and thus needs additional study. Taken together, a more complete understanding of the glycocalyx within the abdomen during sepsis will serve to inform future treatment strategies, applied systemically and directly to the abdomen.

There were several limitations to our study. First, the relatively small samples size. Shortly after the initiation of our study, the COVID-19 pandemic created severe delays in enrollment and challenges in getting tissues collected and processed by pathology. Although our initial projections suggested completing enrollment by 6 months, decreased presentation of qualifying patients to our center and decreased transfer from referring centers, because of issues of nursing shortages and hospital capacity, significantly prolonged the study. As with any prospective study, 24–7 patient screening by dedicated research staff is the ideal for rigorous capture of study patients. In the absence of this, project-affiliated surgical staff (S.P.C., R.D.A., or A.M.N.) were on-call for patient recruitment and specimen procurement, when notified by the in-house surgical team. Collectively, these challenges have been essential toward educating our surgical and research staff on the feasibility of larger study designs involving operative procurement of specimens on a multicenter platform.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the patients and families who agreed to participate in this study, D’Ann Hershel and her team of study coordinators, Tammy Sexton from the Wake Forest Tumor Tissue Pathology Resource Shared Resource Laboratory, Dr Wencheng Li from the Wake Forest Department of Pathology, the personnel from the Wake Forest Clinical Research Unit, and the laboratory of Dr Elaheh Rahbar without whom this effort would have not been possible.

The project described was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through grants KL2TR001421 and UL1TR001420. Dr Rahbar and Nathan Hauser were supported in part by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI K25 HL133611 and HL133611-S1).

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

REFERENCES

- 1.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour C, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315:801–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fleischmann-Struzek C, Mellhammar L, Rose N, et al. Incidence and mortality of hospital- and ICU-treated sepsis: results from an updated and expanded systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:1552–1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rudd KE, Kissoon N, Limmathurotsakul D, et al. The global burden of sepsis: barriers and potential solutions. Crit Care. 2018;22:232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rudd KE, Johnson SC, Agesa KM, et al. Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and mortality, 1990–2017: analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 2020;395:200–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans L, Rhodes A, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Crit Care Med. 2021;49:E1063–E1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lambden S, Laterre PF, Levy MM, et al. The SOFA score—development, utility and challenges of accurate assessment in clinical trials. Crit Care. 2019;23:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levi M, Van Der Poll T, Schultz M. Systemic versus localized coagulation activation contributing to organ failure in critically ill patients. Semin Immunopathol. 2012;34:167–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee WL, Slutsky AS. Sepsis and endothelial permeability. N Engl J Med. 2010;3637:689–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richter RP, Payne GA, Ambalavanan N, et al. The endothelial glycocalyx in critical illness: a pediatric perspective. Matrix Biol plus. 2022;14:100106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Becker BF, Chappell D, Bruegger D, et al. Therapeutic strategies targeting the endothelial glycocalyx: acute deficits, but great potential. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;87:300–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weinbaum S, Tarbell JM, Damiano ER. The structure and function of the endothelial glycocalyx layer. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2007;9:121–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aird WC. Endothelial cells in health and disease. Endothel Cells Heal Dis. 2005;1–486. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johansson PI, Stensballe J, Ostrowski SR. Shock induced endotheliopathy (SHINE) in acute critical illness—a unifying pathophysiologic mechanism. Crit Care. 2017;21:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chignalia AZ, Yetimakman F, Christiaans SC, et al. The glycocalyx and trauma: a review. Shock. 2016;45:338–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smart L, Macdonald SPJ, Burrows S, et al. Endothelial glycocalyx biomarkers increase in patients with infection during emergency department treatment. J Crit Care. 2017;42:304–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Puskarich MA, Cornelius DC, Tharp J, et al. Plasma syndecan-1 levels identify a cohort of patients with severe sepsis at high risk for intubation after large-volume intravenous fluid resuscitation. J Crit Care. 2016;36:125–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Q, Tong Y, Wang H, et al. Origin of Sepsis associated with the short-term mortality of patients: a retrospective study using the eICU collaborative research database. Int J Gen Med. 2021;14:10293–10301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Waele J, Lipman J, Sakr Y, et al. Abdominal infections in the intensive care unit: characteristics, treatment and determinants of outcome. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Volakli E, Spies C, Michalopoulos A, et al. Infections of respiratory or abdominal origin in ICU patients: what are the differences? Crit Care. 2010;14:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murphy LS, Wickersham N, McNeil JB, et al. Endothelial glycocalyx degradation is more severe in patients with non-pulmonary sepsis compared to pulmonary sepsis and associates with risk of ARDS and other organ dysfunction. Ann Intensive Care. 2017;7:102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, et al. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:1250–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, et al. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1368–1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ostrowski SR, Haase N, Müller RB, et al. Association between biomarkers of endothelial injury and hypocoagulability in patients with severe sepsis: a prospective study. Crit Care. 2015;19:191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peng Z, Pati S, Potter D, et al. Fresh frozen plasma lessens pulmonary endothelial inflammation and hyperpermeability after hemorrhagic shock and is associated with loss of syndecan 1. Shock. 2013;40:195–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kozar RA, Peng Z, Zhang R, et al. Plasma restoration of endothelial glycocalyx in a rodent model of hemorrhagic shock. Anesth Analg. 2011;112:1289–1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wei S, Kao LS, Wang HE, et al. Protocol for a pilot randomized controlled trial comparing plasma with balanced crystalloid resuscitation in surgical and trauma patients with septic shock. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2018;3:e000220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Drost CC, Rovas A, Kümpers P. Protection and rebuilding of the endothelial glycocalyx in sepsis—science or fiction? Matrix Biol Plus. 2021;12:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith JW, Neal Garrison R, Matheson PJ, et al. Adjunctive treatment of abdominal catastrophes and sepsis with direct peritoneal resuscitation: indications for use in acute care surgery. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;77:393–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]