Abstract

The best-known mode of action of calmodulin (CaM) is binding of Ca2+ to its N- and C-domains, followed by binding to target proteins. An underappreciated facet of this process is that CaM is typically bound to proteins at basal levels of free Ca2+, including the small, intrinsically disordered, neuronal IQ-motif proteins called PEP-19 and neurogranin (Ng). PEP-19 and Ng would not be effective competitive inhibitors of high-affinity Ca2+-dependent CaM targets at equilibrium because they bind to CaM with relatively low affinity, but they could influence the time course of CaM signaling by affecting the rate of association of CaM with high-affinity Ca2+-dependent targets. This mode of regulation may be domain specific because PEP-19 binds to the C-domain of CaM, whereas Ng binds to both N- and C-domains. In this report, we used a model CaM binding peptide (CKIIp) to characterize the preferred pathway of complex formation with Ca2+-CaM at low levels of free Ca2+ (0.25–1.5 μM), and how PEP-19 and Ng affect this process. We show that the dominant encounter complex involves association of CKIIp with the N-domain of CaM, even though the C-domain has a greater affinity for Ca2+. We also show that Ng greatly decreases the rate of association of Ca2+-CaM with CKIIp due to the relatively slow dissociation of Ng from CaM, and to interactions between the Gly-rich C-terminal region of Ng with the N-domain of CaM, which inhibits formation of the preferred encounter complex with CKIIp. These results provide the general mechanistic paradigms that binding CaM to targets can be driven by its N-domain, and that low-affinity regulators of CaM signaling have the potential to influence the rate of activation of high-affinity CaM targets and potentially affect the distribution of limited CaM among multiple targets during Ca2+ oscillations.

Significance

Calmodulin is a small, essential regulator of multiple cellular processes including growth and differentiation. Its best-known mode of action is to first bind calcium and then bind and regulate the activity of target proteins. Each domain of calmodulin has distinct calcium binding properties and can interact with targets in distinct ways. Here, we show that the N-domain of calmodulin can drive its association with targets, and that a small, intrinsically disordered regulator of calmodulin signaling called neurogranin can greatly decrease the rate of association of calmodulin with high-affinity Ca2+-dependent targets. These results demonstrate the potential of neurogranin, and other proteins, to modulate the time course of activation of targets by a limited intracellular supply of calmodulin.

Introduction

Calmodulin (CaM) is a highly conserved and ubiquitous Ca2+ sensor protein that is essential for the survival and function of all eukaryotic cells. The global structure of CaM consists of N- and C-terminal Ca2+ binding domains that are connected by a flexible linker. This simple design allows multiple modes of interaction with targets that can involve only one or both domains, and in the presence or absence of Ca2+ (1,2,3,4). The most familiar mode of interaction is high-affinity, Ca2+-dependent binding of both N- and C-domains of CaM to a relatively short and contiguous target sequence to form a compact structure that resembles two hands grasping a rope as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Pathways of interactions between Ca2+, CaM, and a CaM binding peptide. Important parameters are described in the text. Green and blue arrows indicate binding of Ca2+ or CKIIp to the N- or C-domains of CaM, respectively. The final complex has the peptide bound to CaM in an antiparallel orientation in which the N- and C-domains of CaM associate primarily with the C- or N-term of the CKIIp, respectively. However, a minor population of transient transition complexes may exist that have a parallel binding orientation. To see this figure in color, go online.

Interactions between CaM and Ca2+-dependent target proteins are primarily regulated by the amplitude and frequency of oscillations in intracellular free Ca2+ (Ca2+F) levels. However, the distribution of CaM among its multiple targets during Ca2+ oscillations will depend on target-specific rates of association and dissociation with Ca2+-CaM, and how targets affect the Ca2+ binding properties of CaM. In general, there is an inverse relationship between the rate of dissociation of Ca2+ from CaM and the affinity of a target for CaM, which results in slower release of Ca2+ and higher affinity when CaM is bound to high-affinity targets (5,6). Less is known about the rate of association of Ca2+-CaM with target proteins, and if the N- or C-domain plays a dominant role. Since the N- and C-domains can interact separately with CaM binding sites on proteins (7), formation of a final active complex could proceed via multiple pathways that are initiated by Ca2+ binding to either the N- or C-domains as shown in Fig. 1. Early models for association of CaM with binding peptides focused on formation of an initial encounter complex involving the C-domain of CaM along pathway 2C in Fig. 1 (6,7), primarily because the affinity of Ca2+ binding to the C-domain is greater than the N-domain (8). However, two factors suggest that the N-domain could play a dominant role in formation of the encounter complex along pathway 2N. First, the rate of Ca2+ association with the N-domain is a least 25-fold greater than the C-domain, and second the affinity of Ca2+ binding to both the N- and C-domains of CaM is greatly increased upon association with targets (5,6,9,10).

Two other factors can impact the mechanism and rate of association of Ca2+-CaM with targets. The first is that levels of Ca2+F can vary significantly in different subcellular compartments. Resting free Ca2+ is around 0.05 μM and can increase 10-fold or greater in response to a variety of stimuli. Peak levels of free Ca2+ in the bulk cytoplasm may increase to 1–2 μM, while it may be up to 100 μM near the surface of membranes where Ca2+ is released through channels. Interactions between CaM and targets at lower levels of free Ca2+ is of special interest because the distinct Ca2+ binding properties of the N- and C-domains may have a greater potential to influence the mechanism of association. The other factor that could modulate interactions between Ca2+-CaM and its targets are proteins that bind to apo-CaM. Two small intrinsically disordered IQ-motif proteins called PEP-19 and neurogranin (Ng) bind to either apo or Ca2+-CaM (11,12). PEP-19 binds selectively to the C-domain of CaM (13), whereas Ng interacts with both N- and C-domains (14). PEP-19 greatly increases the rates of Ca2+ association and dissociation at the C-domain without significantly affecting the KCa (13), which makes the kinetics of Ca2+ binding to the C-domain more similar to those of the N-domain. Ng also increases the rates of Ca2+ dissociation at the C-domain of CaM, but has a lesser effect on the Ca2+ association rate, thereby decreasing overall Ca2+ binding affinity (15). These properties of PEP-19 and Ng on CaM have the potential to regulate activation of Ca2+-dependent CaM target proteins by simple competition, or by modulating the rates of binding Ca2+ to CaM.

The goal of the current study was to use a novel experimental model system to first determine the kinetics and domain specificity of CaM binding to a model CaM binding peptide (CKIIp) in response to levels of free Ca2+ between 0.2 and 5 μM, and then determine if PEP-19 and/or Ng affect the rates of peptide binding. Our data show that the dominant pathway for association involves formation of an encounter complex between the N-domain of CaM and CKIIp. PEP-19 has minimal effect on the rate of binding CaM to CKIIp; however, Ng greatly decreases the rate of association, and this effect is most pronounced at the lower levels of free Ca2+. The effects of Ng are due to its ability to bind to the N-domain of CaM, which likely inhibits formation of the dominant encounter complex. These data demonstrate that Ng could have broad effects on CaM signaling pathways by modulating the rate of association of CaM with Ca2+-dependent targets.

Materials and methods

Protein and peptides

Wild-type mammalian calmodulin (CaM), CaM(K75C), Ng, and Purkinje cell protein 4 (PEP-19) were expressed and purified as described previously (13,15,16). Peptides Ng(26–49), comprising the IQ domain (ANAAAAKIQASFRGHMARKKIKSG), and Ng(13–49), comprising the IQ domain and adjacent acidic region (DDDILDIPLDDPGANAAAAKIQASFRGHMARKKIKSG). The peptide CKIIp, representing the CaM binding site of CaM kinase II (FNARRKLKGAILTTMLATTRN), and a modified version containing a C-terminal cysteine for fluorescent labeling (FNARRKLKGAILTTMLATTRNGC). Peptides were resuspended in 0.13% TFA and further purified on a reverse phase C18 column using a gradient of acetonitrile, 0.1% TFA. Fractions containing peptides were lyophilized and resuspended in water.

Buffers used for stopped flow experiments were decalcified by passage over a small column of Calcium Sponge. Indo-1 was used to determine the effectiveness of decalcification. CaM was decalcified using EDTA/BAPTA followed by desalting. Typically, 20–50 mg of CaM in 10 mL buffer was made to 5 mM in EDTA and 0.1 mM BAPTA, which was used as a chromophore to monitor desalting. The solution was desalted using a P6DG column in a mobile phase of 20 mM ammonium bicarbonate (pH 8.0) that was decalcified using Calcium Sponge. Effective separation of CaM from the chelators was monitored by UV absorbance. The decalcified CaM was lyophilized and weighed.

Donor-labeled CaM was prepared by labeling CaM(K75C), CaM(D2C), or CaM(T110C) with 5-((((2-iodoacetyl)amino)ethyl)amino)naphthalene-1-sulfonic acid (IAEDANS) as described previously (17). In brief, CaM was reduced with TECP and then reacted with excess IAEDANS for at least 4 h. Labeled CaM was separated from free probe by desalting into 20 mM ammonium bicarbonate (pH 8), on a Bio-Rad P-6DG column followed by lyophilization. The extent of labeling was >80%. Donor-labeled CaM(K75C) is referred to simply as CaMD because the great majority of experiments used this derivative. The other donor-labeled CaMs are referred to as CaM(C2)D and CaM(C110)D.

Donor/acceptor labeled CaMD/A was prepared as described previously (18). In brief, CaM(T34,110C) was reduced with TECP and then reacted for at least 4 h with IAEDANS at a low CaM:probe ratio of 0.25:1 to minimize labeling both Cys residues with the donor probe. Excess acceptor N-[4-(dimethylamino)-3,5-dinitrophenyl]-maleimide (DDPM) was then added followed by desalting and lyophilization. CaM with DDPM at both C34 and C110 does not interfere with the assay because DDPM is not fluorescent. Only CaM with 1 IAEDANS and 1 DDPM probe will yield an FRET effect. The IAEDANS:CaM ratio was typically 0.2:1, which decreases the signal/noise ratio relative to CaMD, CaM(C2)D, or CaM(C110)D, which are fully labeled with IAEDANS.

DDPM was also used as an acceptor to label CKIIp with a GC extension at its C-terminal (CKIIpA), as well as human Ng, which has Cys at residues 3, 4, and 9 (NgA). CKIIp or Ng in 40 mM MOPS (pH 8.0), was first reduced with 2.5 mM TCEP, then reacted with a molar excess of DDPM for 4 h at room temperature. Labeled CKIIpA or NgA were purified on a C18 column, lyophilized, and resuspended in water. Powered DDPM was dissolved in DMSO since it has limited solubility in aqueous buffers. It was added to the labeling reactions slowly, drop by drop with immediate shaking.

Assay for the rate of association between CaM and a CKIIp

Several experimental systems were employed to determine the rate of association of CaM and CKIIp in the absence or presence of PEP-19 or Ng. The first system used changes in Tyr fluorescence that results from Ca2+-dependent conformational changes in the C-domain of CaM. Unlabeled CaM was excited at 280 nm and emission was monitored from 300 to 400 nm. The two other systems used FRET. The intermolecular FRET (inter-FRET) assay had the donor on CaMD and acceptor on CKIIpA, whereas the intramolecular FRET (intra-FRET) assay had the donor and acceptor on CaMD/A. IAEDANS-labeled proteins were excited at 340 nM, and FRET was monitored as a decrease in fluorescence 495 nm.

All rates were measured in an Applied Photophysics (Leatherhead, UK) model SV.17 MV sequential stopped-flow spectrofluorimeter with an instrument dead time of 1.7 ms. Reactions were initiated by rapidly mixing equal volumes of solutions from syringes A and B. The stopped-flow buffer (SFB) contained 20 mM MOPS (pH 7.5), 100 mM KCl, and 1 mM DTT. Syringe A contained SFB with 2.5 μM CaM, or its IAEDANS-labeled derivatives, along with 10 μM BAPTA to ensure that CaM was in the apo state. PEP-19 or Ng were also added to syringe A at concentrations of 40 and 20 μM, respectively, since Ng binds to CaM with higher affinity that PEP-19. Syringe B contained SFB with 5 μM CKIIp and either 5 mM EGTA, 5 mM CaCl2, or 5 mM HEDTA, with sufficient CaCl2 to achieve a desired free Ca2+ (Ca2+F). The concentration of CaCL2 added to the HEDTA buffers was based on Maxchelator Standard (available at Maxchelator Standard). The actual Ca2+F was then verified experimentally using 5,5′-dibromo BAPTA (Br2BAPTA) absorbance at 263 nm in a UV-vis spectrometer using the following equation:

where the KCa for Br2BAPTA is 1.59 μM, AbsS is the absorbance of the sample, Abs0 is absorbance in the absence of Ca2+, and Absmax is the absorbance in the presence of saturating 5 mM CaCl2.

A key requirement for stopped flow experiments with HEDTA/Ca2+ buffers is that binding of Ca2+ to CaM should not affect the equilibrium levels of Ca2+F in the buffered solutions. To test this, 5 μM Br2BAPTA was added to the Ca2+/HEDTA as a marker for free Ca2+ levels and then mixed with 10 μM EDTA to mimic 4 Ca2+ binding sites in 2.5 μM CaM. The absorbance of Br2BAPTA was unaffected, which indicated that the Ca2+F was not significantly changed by binding Ca2+ to EDTA. A second requirement is that the rate of replenishing the pool of Ca2+F as Ca2+ binds to CaM should not be a rate-limiting step. To confirm this requirement, we used the Ca2+ chromophore BAPTA, which binds Ca2+ with a Kd of 0.16 μM and kon of 450 μM−1 s−1. If replenishing the pool of Ca2+F is not rate limiting, then 10 μM BAPTA should be saturated with Ca2+ within 10 ms after mixing with 5 mM HEDTA buffers with Ca2+F set at 1–5 μM. Control experiments using BAPTA showed that replenishing the pool of Ca2+F is not rate-limiting in our experimental system.

Time-dependent changes in fluorescence were fit to the following equations with single, double, or triple exponential terms:

where F is the observed fluorescence intensity at time t, Finitial is fluorescence at t = 0, Ffinal is the final fluorescence, and kn are the observed rates.

CaM-Ng dissociation rate

Syringe A contained 20 mM MOPS (pH 7.5), 100 mM KCl, 5 mM CaCl2, 1 μM IAEDANS-labeled CaM(D2C), and 10 μM NgA. Syringe B contained 20 mM MOPS (pH 7.5), 100 mM KCl, 5 mM CaCl2, and 20 μM unlabeled CaM. The decrease in FRET (increase in fluorescence) was monitored as unlabeled CaM exchanged with labeled CaM.

NMR methodology

All NMR experiments were performed on a DRX 600 MHz spectrometer equipped with a 5 mm triple-resonance cryoprobe at 310 K. NMR buffer contained 10 mM imidazole, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM CaCl2, 0.1 mM [15N]CaM, 5 mM DTT, and 5% D2O at pH 6.3. When present, CKIIp, Ng, and PEP-19 were added at concentrations of 0.2, 0.8, and 1.6 mM, respectively. NMR spectra were collected using four scans and a spectral width of 32 ppm in the 15N dimension. Backbone assignments for free Ca2+-CaM were reported previously (13). All NMR data were processed and analyzed using Bruker Topspin 3.5. 1H chemical shifts were referenced to 2,2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulphonate.

Results

Dissociation of Ca2+ from CaM and the CaM/CKIIp complex

As a model system, we used a Ca2+-dependent CaM binding peptide (CKIIp) derived from amino acids 293–312 of CaM-dependent kinase II. The structural features of binding CKIIp to Ca2+-CaM are known in detail from x-ray crystallography (19). The peptide can be thought of as a bivalent CaM binding site because a single peptide binds to both the N- and C-domains of Ca2+-CaM. It has a 1-5-10 spacing of hydrophobic residues with Leu-299 and Leu-308 anchoring the peptide to the C- and N-domains of CaM, respectively, via hydrophobic interactions (3,19). CKIIp binds to Ca2+-CaM with very high affinity (Kd = 1.6 pM), with a rapid kon of 1.2 × 108 M−1 s−1 (16). This makes CKIIp a stringent test for the ability of PEP-19 and Ng to modulate the rate of association of a target with Ca2+-CaM.

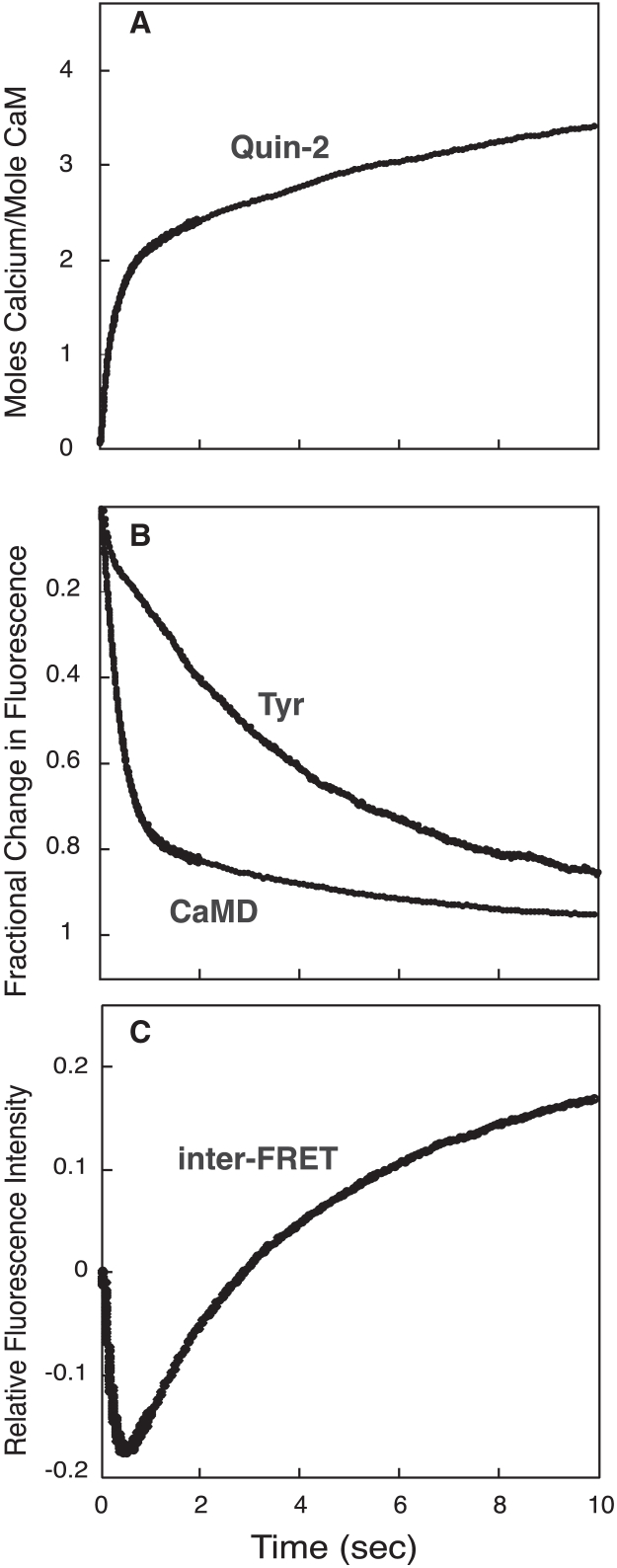

To validate our various assays, and to provide a complete set of kinetic parameters, we first determined the rates of dissociation of Ca2+ and CKIIp from CaM. Fluorescence from Tyr-99 and Tyr-138 is a well-established marker for Ca2+-dependent events in the C-domain of CaM. Fig. 2 A and Table 1 show the rate of change in Tyr florescence after free Ca2+-CaM is rapidly mixed with excess EGTA. A single rate of 9.2 s−1 was observed, which corresponds well to the rate of dissociation of Ca2+ from sites III and IV of CaM reported in previous studies (6,13). The Ca2+-sensitive fluorescent dye Quin-2 was also used because it is a direct measure of Ca2+ release and can be expressed as moles Ca2+ released per mol of CaM. Very rapid binding of free Ca2+ to Quin-2 upon mixing is not detected because it is complete within the 1.7 ms dead time of the stop flow fluorimeter. A subsequent biphasic change in fluorescence is then observed as Ca2+ is released from CaM and binds to Quin-2. Fig. 2 B and Table 1 show that most of the fast phase of Ca2+ release from CaM occurs in the dead time of the stop flow. Because of this, an accurate dissociation rate cannot be determined, but we estimate it is greater than 1000 s−1 and is due to release of Ca2+ from the N-domain. This is consistent with Peersen et al. (6). The slow phase of 8.9 s−1 corresponds well to the rate measured using Tyr fluorescence and is consistent with earlier results for Ca2+ dissociation from the C-domain. Nearly identical rates for Ca2+ release measured using both Tyr and Quin-2 demonstrates that the rate of conformational relaxation in the C-domain is tightly coupled with Ca2+ dissociation.

Figure 2.

Rate of dissociation of Ca2+ from free Ca2+-CaM. Ca2+ dissociation was detected by intrinsic Tyr fluorescence (A), the fluorescent Ca2+ chelator Quin-2 (B), or CaMD (C). Syringe A contained 5 μM CaM or CaMD and 200 μM CaCl2. Syringe B contained 5 mM EGTA (A and C) or 400 μM Quin-2 (B). The Quin-2 response was calibrated using an Orion Ca2+ standard. The slow phase of Ca2+ release in (B) corresponds to 2 mol Ca2+ released/mol CaM and could be used as a calibration control. (C) Shows a control experiment (upper data set) in which buffer B contained 200 μM CaCl2 rather than 5 mM EGTA. This provides an initial fluorescence value used to fit the fast phase of fluorescence shown in the inset of (C).

Table 1.

Rates of dissociation of Ca2+ from Ca2+-CaM in the absence or presence of CKIIp

| Free Ca2+-CaM |

Ca2+-CaM + CKIIp |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate 1 | Amp 1 | Rate 2 | Amp 2 | Rate 1 | Amp 1 | Rate 2 | Amp 2 | ||||

| Quin-2 | >1000 | 2 | 8.9 ± 0.1 | 2 | 6.3 ± 1 | 2.1 | 0.27 ± 0.04 | 2 | |||

| Tyrosine | – | – | 9.2 ± 0.2 | 1 | 5.5 ± 0.1 | 0.17 | 0.25 ± 0.01 | 0.83 | |||

| CaM(C75D) | >1000 | 0.86 | 5.2 ± 0.2 | 0.14 | 5.9 ± 0.1 | 0.79 | 0.34 ± 0.01 | 0.21 | |||

| FRET | 5.8 ± 0.8 | 0.37 | 0.23 ± 0.02 | 0.63 | |||||||

All rates are the average ±SD of four to nine independent experiments.

The amplitudes for data collected using Quin-2 indicate number of moles Ca2+ released/mol protein and were obtained by calibrating the response of Quin-2 with Ca2+ standards. The moles Ca2+ released/mol protein for the fast phase of free CaM could not be accurately fit since about 75% of the signal occurs during the dead time of the instrument. The value of 2 was assigned since CaM binds 4 mol Ca2+, and 2 mol Ca2+/mol protein were released during the slow phase.

The average amplitudes are given. Amplitudes for Tyr, CaM(C75)D, and FRET indicate the relative fractional amplitude of each phase with 1.0 defined as the total change in fluorescence. Absolute values are used to determine amplitudes for FRET.

– indicates that the best fit was a single exponential.

We also used IAEDANS-labeled CaM(K75C) (CaMD) to measure rates of Ca2+ release from free CaM. We showed previously that steady-state fluorescence from CaMD was sensitive to conformational changes caused by Ca2+ binding and subsequent binding to CKIIp (20). Fig. 2 C and Table 1 show that mixing Ca2+-CaMD with excess EGTA leads to a rapid decrease in fluorescence that occurs largely in the dead time of the stop flow, with a rate of >1000 s−1. This is followed by a second phase with a smaller amplitude and slower rate of 5.2 s−1. We interpret the fast and slow phases to correspond to release of Ca2+ from the N- and C-domains, respectively. The larger amplitude for the fast phase is consistent with the location of the donor probe on C75 in helix D near the N-domain of CaM.

We next used Quin-2, CaMD, and Tyr fluorescence to determine how CKIIp binding to Ca2+-CaM affects the rates of Ca2+dissociation as shown in Fig. 3, A and D and Table 1. All three experimental approaches detected a biphasic dissociation of Ca2+ from the CaM/CKIIp complex with rates that were greatly reduced relative to free CaM. The fast rate was 5.5–6.3 s−1, and the slow rate was 0.27–0.34 s−1. These values correspond well with rates reported previously for dissociation of Ca2+ from CaM bound to CaM kinase II peptides (5,6). We can confidently assign the fast and slow rates to dissociation of Ca2+ from the N- and C-domains, respectively, based on the amplitudes of responses. First, it is reasonable to conclude that the slow rate with the large amplitude (0.83) detected by Try fluorescence is due to conformational changes in the C-domain where the Tyr residues reside, whereas the faster rate with a much smaller amplitude (0.17) is due to an allosteric effect relayed through CKIIp to the C-domain when Ca2+ dissociates from the N-domain. Second, the fast rate observed using CaMD is associated with the largest amplitude (0.79), and this amplitude is comparable in magnitude to that observed due to dissociation of Ca2+ from the N-domain of free CaM. Similarly, the amplitudes of the slow rates observed using CaMD are similar in magnitude for both free CaM and the CaM/CKIIp complex.

Figure 3.

Rate of dissociation of Ca2+ from the Ca2+/CKIIp complex. (A) Shows the release of Ca2+ from the Ca2+/CKIIp complex detected using Quin-2. (B) Monitors conformational changes due to release of Ca2+ using fluorescence from Tyr or IAEDANS-labeled CaMD. (C) Uses a FRET assay to detect changes in distance between CaM and CKIIp after Ca2+ is removed. The FRET donor is IAEDANS-labeled CaM(C110)D, and the acceptor is DDPM-labeled CKIIpA. The experiments were performed as described in Fig. 2, except that 10 μM CKIIp was included with CaM and Ca2+ in syringe A.

We used a FRET assay to correlate the rates of dissociation of Ca2+ from the CaM/CKIIp complex with the rates of dissociation of CaM domains from CKIIp. The FRET acceptor, CKIIpA, has DDPM coupled to CKIIp with a Gly-Cys extension at its C-terminus. We predicted that the sequence of dissociation of CaM domains from CKIIpA would be coupled to the sequence of Ca2+ release, specifically, the N-domain would dissociate first followed by the C-domain. Therefore, the FRET donor was CaM(C110)D, which has IAEDANS attached to Cys110 in the C-domain to provide a robust signal for final dissociation of the complex. Fig. 3 C and Table 1 show that mixing Ca2+-CaM(C110)D/CKIIpA with excess EGTA causes an initial decrease in fluorescence, followed by a slower increase with rates of 5.8 and 0.23 s−1, respectively. Based on a comparison of rates shown in Table 1, we conclude that the decrease in fluorescence is due to dissociation of the N-domain of CaM(C110)D from the C-terminal portion of CKIIpA, which allows greater range of motion in the DDPM donor probe and a decrease the average distance between it and the acceptor probe in the C-domain of CaM(C110)D. The slower increase in fluorescence is due to elimination of FRET as the C-domain of CaM(C110)D is released to fully dissociate the complex. Importantly, the rates observed using FRET are essentially identical to those collected using Quin-2, which indicates tight coupling between dissociation of Ca2+ and release of CKIIp from the N- or C-domain of CaM.

Table 1 shows that binding CKIIp to Ca2+-CaM decreases the rate of Ca2+ dissociation from the N- and C-domains about 250- and 35-fold, respectively. The effects of Ca2+-dependent targets on the affinity of CaM for Ca2+ is thought to be largely due to effects on the Ca2+ dissociation rate. If CKIIp has little effect on the Ca2+ association rate, then the Kd for Ca2+ binding to the N- and C-domains of CaM in the presence of CKIIp are both about 0.06 μM. This is consistent with the values reported by Peersen et al. of 0.03–0.04 μM (6).

Measuring association rates at low levels of Ca2+F to mimic the intracellular milieu

Our general experimental design was to employ fluorescent reporters described above to monitor the overall rate of binding CKIIp to CaM after rapidly mixing apo CaM with solutions of CKIIp containing various levels of Ca2+F. A key feature of these experiments was to measure association rates at clamped Ca2+F levels of about 0.25–5 μM to mimic bulk cytoplasmic Ca2+F in response to stimuli (21). We postulated that this would allow us to detect formation of domain-specific encounter complexes, and to identify physiologically relevant effects of PEP-19 and Ng.

As described in detail in the materials and methods, sets of solutions were prepared using HEDTA (KCa ≈ 2.5 μM at pH 7.5) to buffer Ca2+. We used the Ca2+ chelators BAPTA and Br2BAPTA in control experiments to: 1) verify the actual concentration of Ca2+F, 2) confirm that the equilibrium level of Ca2+F is not changed by binding Ca2+ to CaM, and 3) to confirm that replenishing the pool of Ca2+F is not a rate-limiting step, which is necessary to maintain constant Ca2+F during the time course of binding Ca2+ to CaM. Multiple experiments using multiple sets of Ca2+ buffers, ranging from 0.1 to 12 μM Ca2+F, yielded consistent results. To allow ease of direct comparisons, the data presented in all tables reported here were collected using a set of buffers with Ca2+F ranging from 0.26 to 4.56 μM.

Fig. 4A and Table 2 show the rate of increase in Tyr fluorescence upon rapidly mixing free apo CaM with buffers of increasing concentrations of Ca2+F in the absence of CKIIp. The data best fit an exponential equation with a single rate at all levels of Ca2+F. Little change in fluorescence is observed at Ca2+F of 0.26–0.5 μM, and the change in fluorescence is about 84% of maximal at 4.6 μM Ca2+F. This is consistent with a KCa for the C-domain of free CaM of about 2 μM (6,8,22). Fig. 4 B shows a nonlinear relationship between Ca2+F and the rate of change in Tyr fluorescence. We concluded previously that this was due to cooperative binding of Ca2+ to the C-domain of CaM (22). The data in Fig. 4 B were fit to a quadratic function to derive apparent pseudo first-order rates (k) at specific levels of Ca2+F using the first derivative. We selected Ca2+F of 1 μM (k1.0) to compare pseudo first-order rates for data collected using fluorescence reporter assays because 1 μM is comparable with the elevated levels of Ca2+F in the bulk cytoplasm (21). The k1.0 derived from Tyr fluorescence experiments is 5.4 μM−1 s−1. This is in good agreement with the association rate of 4.5 μM−1 s−1 calculated for the C-domain using a KCa of 2 μM and koff of about 9 s−1 from Table 1.

Figure 4.

Rate of change of Tyr fluorescence from CaM upon association with Ca2+ in the absence or presence of CKIIp. (A) Shows the change in fluorescence when CaM (2.5 μM) was rapidly mixed with HEDTA solutions with Ca2+F buffered at 0, 0.26, 0.50 1.1, 2.19, 3.26, or 4.56 μM. No detectable change in Tyr fluorescence was observed at 0.26 μM Ca2+F. (B) Plots the rate of change of Tyr fluorescence (see Table 2) versus the Ca2+F. The line shows a fit to a quadratic equation. (C) Shows the same experiment as in (A) except that 5 μM CKIIp was added to the CaM solution. The apparent increased noise in the early time points of the decay curve is due to use of a split time frame data collection mode. This can also be seen in other figures.

Table 2.

Rates of association of CKIIp with Ca2+-CaM in the absence of PEP-19 or Ng

| Ca2+ (μM) | Tyrosine fluorescence |

Inter-FRET |

Intra-FRET |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free CaM |

CaM + CKIIp |

CaMD + CKIIpA |

CaMD/A + CKIIp |

|||||||||

| Rate (s−1) | Amp | Rate 1 (s−1) | Amp 1 | Rate 2 (s−1) | Amp 2 | Rate 1 (s−1) | Amp 1 | Rate 2 (s−1) | Amp 2 | Rate (s−1) | Amp | |

| 0.26 | nd | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 50 | 0.45 ± 0.01 | 49 | 13 ± 0.2 | 66 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 26 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 87 | |

| 0.50 | 8.2 ± 0.5 | 9 | 5.0 ± 0.2 | 45 | 1.51 ± 0.03 | 56 | 26 ± 0.3 | 76 | 4.0 ± 0.1 | 20 | 3.2 ± 0.3 | 95 |

| 1.10 | 11.4 ± 0.3 | 27 | 12.9 ± 0.4 | 50 | 4.75 ± 0.21 | 50 | 68 ± 0.5 | 80 | 8.2 ± 0.2 | 20 | 10.1 ± 0.5 | 100 |

| 2.19 | 17.8 ± 0.3 | 56 | 22.7 ± 0.8 | 93 | 163 ± 2.6 | 86 | 15.9 ± 0.4 | 14 | 30.2 ± 2.3 | 95 | ||

| 3.26 | 30.7 ± 0.5 | 68 | 43.2 ± 0.8 | 93 | 278 ± 2.5 | 85 | 27.2 ± 1.0 | 14 | 49.2 ± 2.5 | 86 | ||

| 4.56 | 46.5 ± 0.7 | 84 | 69.9 ± 0.7 | 87 | 377 ± 2.2 | 74 | 36.1 ± 1.2 | 16 | 73.1 ± 2.2 | 74 | ||

At least five stopped-flow traces were averaged and fitted using Applied Photophysics SX-Pro Data. The rates are shown with the estimated error of the fit.

To allow comparisons of amplitudes obtained from biphasic fits, as well as fits for different levels of Ca2+F, the amplitudes are expressed relative to the overall amplitude at the Ca2+F that gave the largest overall change in fluorescence within the data set. In the absence of CKIIp, the largest change in fluorescence was at 5 mM Ca2+.

In striking contrast to free CaM, Fig. 4 C and Table 2 show that in the presence of CKIIp the increase in Try fluorescence approaches maximal even at the lowest Ca2+F. This is due to the large increase in Ca2+ binding affinity of CaM upon binding to CKIIp (6,7). This means that the large change in fluorescence at low Ca2+F reflects the rate of accumulation of the CKIIp/Ca2+-CaM complex as CKIIp binds to Ca2+-CaM and traps it in the Ca2+-bound form. The rate of change in Tyr fluorescence is significantly slower and more complex in the presence of CKIIp. The data in Fig. 4 C best fit an exponential equation with two rates up to 1.1 μM Ca2+F, but only a single rate above 1.1 μM (see Table 2). The faster rate observed at all levels of Ca2+F is generally comparable in magnitude with the single rate observed for CaM in the absence of CKIIp. The implication of this with respect to the sequence of interactions between CKIIp and CaM is presented in the discussion.

Use of inter-FRET to monitor association rates

We used an inter-FRET assay with a donor probe on CaM and the acceptor on CKIIp to monitor initial binding of CaM to CKIIp. Unlike Tyr fluorescence, the inter-FRET assay is a more direct sensor of association between CaM and CKIIp and has the potential to sense binding events at either the N- or C-domain. The acceptor was CKIIpA with DDPM coupled to its C-terminus. We were especially interested in the possibility that the N-domain of CaM initiates complex formation by binding to the C-terminal portion of CKIIpA, so we used CaMD as the FRET donor with IAEDANS bound to Cys75 near the N-domain. Based on the crystal structure of CKIIp bound to Ca2+-CaM (19), we anticipated that the greatest inter-FRET effect would occur when the N-domain of CaMD binds to the C-terminal portion of CKIIpA.

Fig. 5A shows that a robust inter-FRET response occurs within the first second of mixing apo-CaMD and CKIIp with Ca2+. Like Tyr fluorescence, the change in inter-FRET approaches maximal amplitude even at 0.26 μM Ca2+F. The time-dependent changes in inter-FRET are more complex than for Tyr fluorescence, and best fit a tri-exponential equation with the slowest rate representing <7% of the overall change in amplitude. Interestingly, Fig. S1 shows that a small, slow change in the inter-FRET signal is seen even when CaMD was mixed with CKIIpA in the presence of 5 mM Ca2+F and persists for at least 200 s, well after complex formation is complete. This very slow phase may be due to a Ca2+-independent conformational change in the Ca2+-CaMD/CKIIpA complex, or a subpopulation of complexes. One possible mechanism is that a small population of CKIIp binds to CaM in a parallel orientation and then rearranges to the preferred antiparallel complex. Torok et al. (23) invoked this mechanism to explain certain features of their model for binding CaM to CaM kinase II.

Figure 5.

Use of inter- and intra-FRET assays to monitor the rate of association of Ca2+-CaM with CKIIp. The inter-FRET assay in (A) shows the change in fluorescence when a solution of CaMD (2.5 μM) and CKIIpA (5 μM) was rapidly mixed with HEDTA solutions with the indicated concentrations of buffered Ca2+F. The intra-FRET assay in (B) shows the change in fluorescence when a solution of CaMD/A (2.5 μM) and CKIIp (5 μM) was rapidly mixed with HEDTA solutions with increasing concentrations of buffered Ca2+F.

Regardless of the mechanism that results in the minor slow rate, it occurs well after formation of the CaMD/CKIIpA complex. Thus, our data analysis focused on rates of change in inter-FRET fluorescence that are associated with the sequential binding of the N- or C-domain of CaMD to CKIIpA. As described in more detail in the discussion our conclusion is that the dominant pathway for binding CaM to CKIIp involves formation of an encounter complex between the N-domain of CaM via step 2N in Fig. 1.

Use of intra-FRET to monitor binding events

We also measured association rates using an intra-FRET assay that relies on FRET between donor and acceptor probes attached to the N- and C-domains of CaMD/A, which we used previously for assays performed under steady-state state conditions (17). Intuitively, intra-FRET would be most sensitive to step 4 in Fig. 1 because this involves a significant change in the relative distance between the N- and C-domains of CaM. Fig. 5 B shows the intra-FRET response at 0 to 1.1 μM Ca2+F. The data fit a single exponential equation; however, we cannot exclude the possibility that a second rate is obscured due to the low signal/noise ratio caused by a much lower probe/protein ratio of CaMD/A compared with CaMD. Table 2 shows that the single rate observed at all levels of Ca2+F are close in magnitude to the fast rate observed for Tyr fluorescence in the presence of CKIIp. The implications of these data with respect to the sequence of interactions between CKIIp and CaM are presented in the discussion.

Effects of PEP-19 on association of CKIIp with Ca2+-CaM

Fig. 6 shows the typical effect of PEP-19 and Ng on response curves for Tyr, inter-FRET, and intra-FRET assays collected at 1.1 μM Ca2+F. Tables 3 and 4 show rates derived at all levels of Ca2+F in the presence of PEP-19 or Ng, respectively. Fig. 6 A and Table 3 show that PEP-19 increased the rate observed using the Tyr fluorescence assay, and that two rates are observed at all levels of Ca2+F. The slow rate has the greatest amplitude at lower Ca2+F, whereas the fast rate dominates at higher Ca2+F. The slow rate is similar in magnitude to the rate seen at all levels of Ca2+F in the absence of PEP-19. The pseudo first-order rate constants in Table 5 show that, in the presence of PEP-19, the fast rate (k1.0R1) of 85.4 μM−1 s−1 is up to 16-fold greater than the two rates observed in the absence of PEP-19. Interestingly, Fig. 6 and Tables 2 and 3 show that PEP-19 has little effect on the apparent rate of association of CKIIp with CaM when measured using either the inter-FRET or intra-FRET assays. As described in more detail in the discussion, these results point to a mechanism in which PEP-19 decreases cooperative Ca2+ binding to sites III and IV in the C-domain of CaM, which allows distinct stages of association between Ca2+-CaM and CKIIp with the C-domain. The slower stage is both required and rate-limiting for formation of the final compact complex between CaM and CKIIp.

Figure 6.

Effect of PEP-19 and Ng on the rate of association of CKIIp with Ca2+-CaM. The experiments were performed as described in Figs. 4 and 5 except that the solutions of CaM and CKIIp in syringe A were prepared with or without 40 μM PEP-19 or 20 μM Ng. Syringe B contained an HEDTA solution with 1.1 μM Ca2+F. (A–C) Show the results using Tyr, inter-FRET, and intra-FRET assays, respectively. The effects of PEP-19 and Ng on rate obtained at other concentrations of Ca2+F are reported in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 3.

Rates of association of CKIIp with Ca2+-CaM in the presence of PEP-19

| Ca2+ (μM) | Tyrosine fluorescence + PEP-19 |

Inter-FRET + PEP-19 |

Intra-FRET + PEP-19 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate 1 (s−1) | Amp 1 | Rate 2 (s−1) | Amp 2 | Rate 1 (s−1) | Amp 1 | Rate 2 (s−1) | Amp 2 | Rate (s−1) | Amp | |

| 0.26 | 5.7 ± 0.5 | 33 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 62 | 12 ± 0.8 | 25 | 3.8 ± 0.1 | 66 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 79 |

| 0.50 | 17.9 ± 0.5 | 47 | 3.8 ± 0.6 | 55 | 19 ± 0.1 | 60 | 4.9 ± 0.8 | 35 | 3.9 ± 0.1 | 90 |

| 1.10 | 55 ± 4 | 47 | 14.4 ± 0.4 | 50 | 49 ± 0.6 | 86 | 7.2 ± 0.6 | 15 | 11.0 ± 0.3 | 100 |

| 2.19 | 158 ± 25 | 51 | 41 ± 2 | 56 | 136 ± 2 | 87 | 16.2 ± 1.2 | 15 | 30 ± 1 | 99 |

| 3.26 | 262 ± 26 | 73 | 58 ± 3 | 30 | 254 ± 7 | 81 | 32.7 ± 2.4 | 16 | 58 ± 4 | 80 |

| 4.56 | 346 ± 45 | 64 | 75 ± 5 | 20 | 414 ± 17 | 81 | 50.9 ± 3.6 | 18 | 99 ± 7 | 74 |

At least five stopped-flow traces were averaged and fitted using Applied Photophysics SX-Pro Data. The rates are shown with the estimated error of the fit.

To allow comparisons of amplitudes obtained from biphasic fits, as well as fits for different levels of Ca2+F, the amplitudes are expressed relative to the overall amplitude at the Ca2+F that gave the largest overall change in fluorescence within the data set.

Table 4.

Rates of association of CKIIp with Ca2+-CaM in the presence of Ng

| Ca2+ (μM) | Tyrosine fluorescence + Ng |

Inter-FRET + Ng |

Intra-FRET + Ng |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate 1 (s−1) | Amp 1 | Rate 2 (s−1) | Amp 2 | Rate 1 (s−1) | Amp 1 | Rate 2 (s−1) | Amp 2 | Rate (s−1) | Amp | |

| 0.26 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 17 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 54 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 33 | 0.19 ± 0.1 | 56 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 71 |

| 0.50 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 41 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 52 | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 25 | 0.68 ± 0.1 | 70 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 86 |

| 1.10 | 4.7 ± 0.2 | 45 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 56 | 9.6 ± 0.3 | 26 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 72 | 4.5 ± 0.2 | 95 |

| 2.19 | 15.3 ± 0.5 | 61 | 4.3 ± 0.1 | 40 | 51 ± 2 | 22 | 9.0 ± 0.1 | 76 | 17.5 ± 0.5 | 100 |

| 3.26 | 30.9 ± 1.4 | 72 | 11.1 ± 0.2 | 28 | 128 ± 10 | 28 | 20.3 ± 0.2 | 74 | 32.9 ± 1.4 | 93 |

| 4.56 | 59.1 ± 5.8 | 57 | 21.7 ± 0.4 | 40 | 246 ± 18 | 30 | 33.3 ± 0.4 | 71 | 48.0 ± 1.9 | 94 |

Table 5.

Pseudo first-order calcium-dependent association rate constants

| Tyr |

Tyr + CKIIp |

Inter-FRET |

Intra-FRET |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k1.0 | k1.0R1 | k1.0R2 | k1.0R1 | k1.0R2 | k1.0 | |

| CaM | 5.4 | 10.6 | 5.2 | 84.2 | 8.0 | 15 |

| CaM +PEP-19 | 85.5 | 17.9 | 62.1 | 6.6 | 13.8 | |

| CaM +Ng | 6.4 | 1.8 | 22.5 | 4.6 | 3.8 | |

Rates (k) were derived by first fitting the data in Tables 1, 2, and 3 to linear or quadratic functions. The best fits were used to calculate the first derivative (tangent) at 1.0 μM Ca2+F, which is the apparent pseudo first-order rate constant at that level of Ca2+F.

Numbers in bold indicate rates associated with the dominant amplitude.

Ng decreases the rate of association of CKIIp with Ca2+-CaM

Fig. 6 and Table 4 shows that Ng significantly decreases the overall rate of association of CKIIp with CaM when measured using all assays. This effect is most evident using the inter-FRET assay, and is most pronounced at lower levels of Ca2+F. It is reasonable to assume that the inter-FRET response with the fastest rate is due to formation of the preferred encounter complex along the pathway to final complex formation. Interestingly, the faster rate in the presence of Ng has a lower amplitude of fluorescence change relative to the absence of Ng, or the presence of PEP-19, which suggests a significant difference in the nature of the encounter complex in the presence of Ng. The rates observed for the intra-FRET assay in the presence of Ng is very similar in magnitude at all levels of Ca2+F to the faster rate seen using Tyr fluorescence.

Data for the inter-FRET assay in Tables 2 and 4 show that the relative amplitudes of the fast rates dominate in the absence of Ng, but the amplitudes are greater for the slow rate in the presence of Ng. The magnitude of this effect is also seen from k1.0 values in Table 5. For example, Ng decreases the dominate k1.0 rate observed using the inter-FRET assay from 84.2 to 4.6 s−1 μM−1.

Two rates are also detected by Tyr fluorescence in the presence of Ng at all levels of Ca2+F. Table 5 shows that the faster k1.0 of 6.4 s−1 μM−1 measured using Tyr fluorescence is comparable with the slower inter-FRET rate of 4.6 s−1 μM−1, and the single intra-FRET rate of 3.8 s−1 μM−1. This suggests that these rates are due to the same kinetic step and are likely due to the formation of a final compact complex between CaM and CKII.

Ng and PEP-19 cause a nonlinear relationship between Ca2+F and the rate of initial complex formation

An interesting feature of Fig. 4 B is the nonlinear relationship between Ca2+F and the rate of Ca2+ binding to free CaM measured using Tyr fluorescence. We observed this previously (22) and attribute it to cooperative binding of Ca2+ to the C-domain of CaM. This led us to ask whether the rate of initial binding of Ca2+-CaM to CKIIp also exhibits nonlinearity with respect to levels of Ca2+F. Fig. 7 shows the Ca2+ dependence of the fast rate observed using the inter-FRET assay, which is the best indicator of formation of the initial encounter complex. The linear relationship seen for CaM is consistent with complex formation being primarily driven by the N-domain, which binds Ca2+ with less cooperativity than the C-domain. Interestingly, in the presence of PEP-19 and especially Ng, the curves are nonlinear, which indicates apparent positive cooperativity. The inset shows the ratio of the pseudo first-order rate constants at 0.25 and 4.5 μM Ca2+F in the absence or presence of PEP-19 or Ng. A ratio of >20 in the presence of Ng means that the rate of initial complex formation is more responsive to Ca2+ at higher levels of Ca2+F.

Figure 7.

Ng and PEP-19 confer apparent cooperative binding of CKIIp to Ca2+-CaM. The curves show plots of Ca2+F versus the rates for the fast component (Rate 1) measured using the inter-FRET assay in the absence (○) or presence of PEP-19 (▪) or Ng (●). The inset shows the ratio of apparent pseudo first-order rate constants at 4.5 and 0.25 μM Ca2+F (k4.5/k0.25).

The Gly-rich C-terminal portion of Ng is required for its effect on association of CKIIp with CaM

The primary sequence of Ng has an IQ motif that is flanked on its N-terminal side by an acidic sequence and on its C-terminal side by a Gly-rich sequence. Interestingly, we concluded using NMR that the Gly-rich C-terminal region of Ng associates with the N-domain Ca2+-CaM, whereas PEP-19, which lacks a Gly-rich region, binds only to the C-domain of CaM (14,22). These observations led us to determine the effect of the Gly-rich region in Ng on the rate of association of CKIIp with Ca2+-CaM. Fig. 8 shows that Ng(13–49), which includes both the acidic and IQ motifs, but is missing the Gly-rich C-term sequence, only slightly slows the rate of association of CKIIp with CaM. Thus, the Gly-rich region of Ng that interacts with the N-domain of CaM is primarily responsible for decreasing the rate of association of CKIIp with CaM.

Figure 8.

The effect of Ng on the rate of association of CKIIp with Ca2+-CaM is due to its C-terminal Gly-rich sequence. The inter-FRET experiments were performed as described in Fig. 6B except that syringe A was prepared with or without 40 μM Ng or Ng(13–49). Syringe B contained an HEDTA solution with 1.1 μM Ca2+F.

Ng slowly dissociates from Ca2+-CaM

We used NMR to determine if Ng or PEP-19 effectively competes with CKIIp for binding to Ca2+-CaM. Fig. S2 shows that binding CKIIp causes large chemical shift perturbations for almost all backbone amides in the 1H-15N-HSQC spectrum of 15N-lableled Ca2+-CaM. Figs. S3 and S4 show that addition of excess PEP-19 or Ng to the Ca2+-CaM/CKIIp complex caused little or no change to the HSQC spectra. This indicates that CKIIp, Ng, and PEP-19 bind to the same or overlapping sites on Ca2+-CaM, and that association of CKIIp with Ca2+-CaM effectively prevents binding of Ng and PEP-19 under equilibrium conditions because its affinity for Ca2+-CaM is orders of magnitude greater than Ng or PEP-19.

Even though CKIIp will fully displace Ng or PEP-19 from Ca2+-CaM at equilibrium, the rate of dissociation of these modulators from Ca2+-CaM to expose binding sites for CKIIp could affect the rate at which equilibrium is achieved. This step does not seem to be rate limiting for PEP-19 because we used a FRET assay to show that PEP-19 fully disassociates from Ca2+-CaM within the dead time of the stopped-flow fluorimeter (24). Fig. 9 shows a similar FRET experiment to monitor the dissociation of Ng from Ca2+-CaM. The data best fit an exponential equation with two rates of 90 and 15 s−1, with approximately equal amplitudes. Both rates are significantly slower than the rate of dissociation of PEP-19 from Ca2+-CaM and are likely due to sequential dissociation Ng from the N- and C-domains of CaM. Together, these data show that Ng does not effectively compete with CKIIp for binding to Ca2+-CaM under steady-state conditions but could inhibit the rate of association due to its relatively slow rate of dissociation.

Figure 9.

Rate of dissociation of Ng from Ca2+-CaM. Syringe A contained 1 μM IAEDANS-labeled CaM(D2C) and 10 μM NgA. Syringe B contained 20 μM unlabeled CaM. Both syringes contained 5 mM Ca2+. The increase in fluorescence reflects the rate of dissociation of labeled CaM from NgA and subsequent binding of excess unlabeled CaM.

Discussion

Premise for the study

Binding Ca2+-CaM to target proteins can greatly increase its Ca2+ binding affinity due primarily to a decrease in the rate of dissociation of Ca2+ from the complex, and the magnitude of this effect is a function of the CaM binding sequence in the target (5,6,9,10). This phenomenon likely contributes to the differential inactivation of CaM targets as Ca2+ levels fall. However, much less is known about the rate of Ca2+-dependent association of Ca2+-CaM with targets during a rise in Ca2+ levels, or during oscillations in Ca2+. In this study we used a target peptide derived from CaM kinase II to provide a tractable model system to establish the mechanism and rate of association of both domains of Ca2+-CaM with a high-affinity target in the absence or presence of PEP-19 or Ng. Importantly, this was done at levels of free Ca2+ of around 1 μM to mimic the intracellular milieu, and to enhance the potential to observe functional consequences of divergent Ca2+ binding properties of the N- and C-domains of CaM.

The N-domain of Ca2+ can drive association with CKIIp

Our first goal was to establish a baseline model for the sequence of Ca2+-dependent interactions between CaM and CKIIp in the absence of Ng or PEP-19, with a special focus on whether formation of the initial encounter complex was driven by the N- or C-domain of CaM. Early models focused on initial contact between the C-domain of CaM and target peptides along pathway 2C in Fig. 1, primarily because the affinity of Ca2+ binding to the C-domain is greater than the N-domain (6,7). However, we anticipated that initial contact involving the N-domain along pathway 2N could dominate because the rate of association of Ca2+ with the N-domain is much greater than the C-domain, and because Table 1 shows that the Ca2+ binding affinity of the N-domain is increased about 250-fold (KCa = 0.06 μM) upon binding to CKIIp due to a large decrease in the rate of Ca2+ dissociation. We reasoned that an encounter complex formed between CKIIp and the N-domain of CaM would be stabilized and accumulate due to this increase in the Ca2+ binding affinity. The following logic supports this hypothesis.

Domain-specific interactions between CaM and CKIIp can be deduced by comparing the rates of change of Tyr fluorescence, which is an indicator of Ca2+ binding to the C-domain, with the rates of change observed using the inter-FRET and intra-FRET assays, which are primary indicators of initial binding and final complex formation, respectively. If initial binding of CKIIp is driven primarily via the C-domain of CaM, then the dominant inter-FRET rate should be similar or slightly slower than the rate of Ca2+ binding to the C-domain, but this is not the case. The data in Table 2 show that the dominant rate (greatest amplitude) of complex formation observed using the inter-FRET assay is much faster at all levels of Ca2+F than the rate of association of Ca2+ with the C-domain of CaM determined using Tyr fluorescence in the presence or absence of CKIIp. Moreover, the rate observed using the intra-FRET assay is comparable with the rate of binding Ca2+ to the C-domain in the presence of CKIIp. From this we conclude that the dominant pathway for complex formation is via step 2N in Fig. 1 and involves rapid binding of Ca2+ to the N-domain of CaM, followed by rapid binding of the N-domain to CKIIp and stabilization of the encounter complex due an increase in the Ca2+ binding affinity in the N-domain. This is followed by final complex formation along steps 3C and 4C, which correlates with slower Ca2+ binding to the C-domain. This sequence of interactions could differ within the context of intact target proteins due to factors such as different accessibilities of binding sites for the N- and C-domains of CaM; nevertheless, it provides a well-characterized baseline kinetic model for interpreting the effects of PEP-19 and Ng.

PEP-19 affects the cooperativity of Ca2+ binding to the C-domain of CaM

A comparison of data in Tables 2 and 3 shows that the inter-FRET rates and amplitudes are generally similar in the absence or presence of PEP-19 with the faster rate having the dominant amplitude, especially at higher levels of Ca2+F. Thus, PEP-19 does not greatly affect the dominant pathway for complex formation via step 2N in Fig. 1. This is not surprising because PEP-19 binds selectively to the C-domain (13), and we concluded above that initial contact with CKIIp is primarily driven by the N-domain. We were also not surprised that PEP-19 increased the Ca2+-dependent rate of Tyr fluorescence in the presence of CKIIp (see Fig. 6 A) because PEP-19 increases the rate of Ca2+ binding to the C-domain (13). However, we anticipated that PEP-19 would increase the rates observed using the intra-FRET or inter-FRET assays, but this was not seen. Modulation of cooperative Ca2+ binding to the C-domain may provide a mechanism to explain these results. We showed previously that PEP-19 decreases the cooperativity of Ca2+ binding to the C-domain (22). The data in Table 3 are consistent with this observation because Tyr fluorescence detects two events with fast and slow rates at all levels of Ca2+F in the presence of PEP-19 and CKIIp. Interestingly, the slow rate of change in Tyr fluorescence in the presence of PEP-19 (Rate 2 in Table 3) is similar in magnitude to both the fast rate in the absence of PEP-19 (Rate 1 in Table 2), and with the rates observed using inter-FRET in the absence or presence of PEP-19. These data support a model in which PEP-19 promotes rapid binding of Ca2+ to site III or IV in the C-domain, but that the 1-Ca2+ form of the C-domain is not competent to bind to CKIIp. Slower Ca2+ binding to the second site is required for the C-domain to associate with CKIIp and is detected by a second phase of change in Tyr fluorescence, as well as a change in the inter-FRET signal. Based on the NMR solution structure of PEP-19 bound to apo-CaM, we propose that Ca2+ binds first to site III and then site IV (25). The rapid rate of dissociation of PEP-19 from the C-domain of Ca2+-CaM (>400 s−1) (24) is consistent with this model because PEP-19 does not present a kinetic barrier that would inhibit or slow the rate of binding of CKIIp.

Ng greatly decreases the rate of association of CKIIp with Ca2+CaM

In contrast to PEP-19, all assays show that Ng significantly decreases the overall rate of association of CKIIp with CaM, and that this effect is especially striking at lower concentrations of Ca2+F. For example, Table 5 shows that Ng decreases the dominant k1.0 rate measured using inter-FRET by almost 20-fold from 84.2 to 4.6 s−1 μM−1. We conclude from Figs. 8 and 9 that this property of Ng is due to the combined effects of two factors. First, the Gly-rich C-terminal portion of Ng binds to the N-domain of CaM to inhibit interaction between the N-domain and CKIIp. Second, Ng dissociates relatively slowly from Ca2+-CaM to further inhibit the rate of binding to CKIIp. These two factors suggests that Ng directs CKIIp to bind initially to the C-domain by sterically blocking binding the CKIIp binding site in the N-domain. This would explain why the dominant amplitude seen for the inter-FRET assay in the presence of Ng is associated with the slower rate (Amp 2 in Table 4), instead of the faster rate (Amp 1 in Table 2) in the absence of Ng. It is also possible that the preferred pathway in the presence of Ng depends on the level of Ca2+F. For example, pathway 2C may be preferred at lower Ca2+F, whereas 2N dominates at higher Ca2+F. This would be consistent with the fact that Ng decreases the Ca2+ binding affinity of CaM (14). Regardless of the precise mechanism, it is clear that Ng greatly slows the rate of binding CKIIp to Ca2+-CaM and could differentially modulate the rate of activation of CaM target proteins in cells.

Ng tunes the Ca2+ sensitivity of complex formation

Fig. 7 shows that PEP-19, and especially Ng, causes a nonlinear relationship between Ca2+F and the rate of association between CaM and CKIIp. Essentially, the Ca2+ sensitivity of CaM binding to CKIIp is decreased at low levels of Ca2+F, and there is a disproportionate increase in the rate of association at higher levels of Ca2+F. This may be due to multiple factors, including different pathways to complex formation at low versus high Ca2+F. Regardless of the precise mechanism, the data demonstrate that Ng has the potential to modulate CaM signaling by tuning the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of complex formation. The extent of this phenomenon on the spectrum of CaM target proteins will likely depend on the mode of CaM binding, but Ng could, for example, provide a kinetic proof-reading mechanism to prevent unwanted activation of CaM targets under oscillating but subthreshold Ca2+ increases.

Potential effects on distribution of CaM among targets

Intracellular levels of CaM are limiting relative to the total number of CaM binding proteins (26). This condition establishes a competitive scenario in which the largest fraction of Ca2+-CaM will associate with the highest affinity targets at equilibrium. However, equilibrium with respect to Ca2+ is an elusive intracellular condition due to frequent oscillations in Ca2+ levels, and computational models predict that oscillating Ca2+ levels are sensed by the Ca2+ binding properties of CaM to achieve differential activation of target proteins (27). Shuffling of CaM between targets during Ca2+ oscillations will depend on the rate of association of Ca2+-CaM with target proteins, and the rate of dissociation of Ca2+ from Ca2+-CaM/target complexes. The rate of association of Ca2+-CaM with targets will depend on factors such as local levels of and rate of diffusion of Ca2+F, the local levels of free or bound CaM, and the accessibility of CaM binding sites on targets. The data presented here demonstrate that Ng can play a role in this process by significantly decreasing the rate of association of targets with Ca2+-CaM. This adds a new mechanism to modulate the distribution of CaM between targets during Ca2+ oscillations, one that can be regulated by phosphorylation of Ng, which inhibits binding to CaM (28).

Conclusion

Ng and PEP-19 are small, intrinsically disordered proteins with no known biological activity other than binding to CaM, yet they have the potential to regulate CaM signaling pathways via multiple mechanisms. One mechanism is their ability to modulate the Ca2+ binding properties of CaM (13,15). They bind CaM with relatively low affinity and would be poor steady-state competitive inhibitors of high-affinity intracellular CaM targets, but CaM has multiples modes of interaction with targets, so Ng and PEP-19 could function as inhibitors of low-affinity targets that bind primarily to the N- or C-domain of CaM. They could also modulate the activation/inactivation of targets such as the voltage gated Ca2+ channels on which the N- and C-domains of CaM shift among different binding sites (29). The data presented here demonstrate that inhibiting the rate of association of Ca2+-CaM with high-affinity targets is another mechanism by which Ng can impact CaM signaling. The magnitude of this effect will likely depend on the mode of interaction of Ca2+-CaM with different targets. Nevertheless, this mechanism of Ng could contribute to tuning the differential activation of targets in a complex cellular milieu where multiple targets compete for a limited supply of CaM. This mechanism could also influence the redistribution of CaM, and the coordinated activation of CaM targets during a train of Ca2+ oscillations.

Author contributions

J.A.P. designed the experiments, helped collect stop-flow data, prepared the figures and tables, and wrote the manuscript. L.H. and V.B. helped collect stop-flow data. X.W. collected and processed the NMR data. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. M. Neal Waxham for reviewing the manuscript and providing insightful comments. This work was supported in part by grant R01 GM104290 from the National Institutes of Health to J.A.P.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Editor: Judy Kim.

Footnotes

Supporting material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2024.05.010.

Supporting material

References

- 1.Persechini A., Kretsinger R.H. The central helix of calmodulin functions as a flexible tether. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:12175–12178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crivici A., Ikura M. Molecular and structural basis of target recognition by calmodulin. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 1995;24:85–116. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.24.060195.000505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamniuk A.P., Vogel H.J. Calmodulin's flexibility allows for promiscuity in its interactions with target proteins and peptides. Mol. Biotechnol. 2004;27:33–57. doi: 10.1385/MB:27:1:33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forest A., Swulius M.T., et al. Waxham M.N. Role of the N- and C-lobes of calmodulin in the activation of Ca(2+)/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Biochemistry. 2008;47:10587–10599. doi: 10.1021/bi8007033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson J.D., Snyder C., et al. Flynn M. Effects of myosin light chain kinase and peptides on Ca2+ exchange with the N- and C-terminal Ca2+ binding sites of calmodulin. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:761–767. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.2.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peersen O.B., Madsen T.S., Falke J.J. Intermolecular tuning of calmodulin by target peptides and proteins: Differential effects on Ca2+ binding and implications for kinase activation Protein. Science. 1997;6:794–807. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bayley P.M., Findlay W.A., Martin S.R. Target recognition by calmodulin: dissecting the kinetics and affinity of interaction using short peptide sequences. Protein Sci. 1996;5:1215–1228. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560050701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Linse S., Helmersson A., Forsén S. Calcium binding to calmodulin and its globular domains. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:8050–8054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olwin B.B., Storm D.R. Calcium binding to complexes of calmodulin and calmodulin binding proteins. Biochemistry. 1985;24:8081–8086. doi: 10.1021/bi00348a037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Persechini A., White H.D., Gansz K.J. Different mechanisms for Ca2+ dissociation from complexes of calmodulin with nitric oxide synthase or myosin light chain kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:62–67. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slemmon J.R., Feng B., Erhardt J.A. Small proteins that modulate calmodulin-dependent signal transduction: Effects of PEP-19, neuromodulin, and neurogranin on enzyme activation and cellular homeostasis. Mol. Neurobiol. 2000;22:99–113. doi: 10.1385/MN:22:1-3:099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerendasy D.D. Homeostatic tuning of the Ca2+ signal transduction by members of the calpacitin protein family. J. Neurosci. Res. 1999;58:107–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Putkey J.A., Kleerekoper Q., et al. Waxham M.N. A new role for IQ motif proteins in regulating calmodulin function. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:49667–49670. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300372200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoffman L., Chandrasekar A., et al. Waxham M.N. Neurogranin alters the structure and calcium binding properties of calmodulin. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:14644–14655. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.560656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaertner T.R., Putkey J.A., Waxham M.N. RC3/Neurogranin and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II produce opposing effects on the affinity of calmodulin for calcium. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:39374–39382. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405352200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waxham M.N., Tsai A.-L., Putkey J.A. A mechanism for calmodulin (CaM) trapping by CaM-kinase II defined by a family of CaM binding peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:17579–17584. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.28.17579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang X., Xiong L.W., et al. Putkey J.A. The Calmodulin Regulator Protein, PEP-19, Sensitizes ATP-induced Ca2+ J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:2040–2048. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.411314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiong L., Kleerekoper Q.K., et al. Hamilton S.L. Sites on calmodulin that interact with the C-terminal tail of Cav1.2 channel. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:7070–7079. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410558200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meador W.E., Means A.R., Quiocho F.A. Modulation of calmodulin plasticity in molecular recognition on the basis of X-Ray structures. Science. 1993;262:1718–1721. doi: 10.1126/science.8259515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Putkey J.A., Waxham M.N. A peptide model for calmodulin trapping by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:29619–29623. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.47.29619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clapham D.E. Calcium signaling. Cell. 2007;131:1047–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Putkey J.A., Waxham M.N., et al. Kleerekoper Q.K. Acidic/IQ motif regulators of calmodulin. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:1401–1410. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703831200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Torok K., Tzortzopoulos A., et al. Thorogate R. Dual effect of ATP in the activation mechanism of brain Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II by Ca2+/calmodulin. Biochemistry. 2001;40:14878–14890. doi: 10.1021/bi010920+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kleerekoper Q.K., Putkey J.A. PEP-19: An instrinsically disordered regulator of CaM signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:7455–7464. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808067200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang X., Putkey J.A. PEP-19 modulates calcium binding to calmodulin by electrostatic steering. Nat. Commun. 2016;7 doi: 10.1038/ncomms13583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Persechini A., Stemmer P.M. Calmodulin is a limiting factor in the cell. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2002;12:32–37. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(01)00144-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Slavov N., Carey J., Linse S. Calmodulin transduces Ca2+ oscillations into differential regulation of its target proteins. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2013;4:601–612. doi: 10.1021/cn300218d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gerendasy D.D., Herron S.R., et al. Sutcliffe J.G. Mutational and biophysical studies suggest RC3/neurogranin regulates calmodulin availability. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:22420–22426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ames J.B. L-type Ca(2+) Channel Regulation by Calmodulin and CaBP1. Biomolecules. 2021;11:1811. doi: 10.3390/biom11121811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.