Abstract

Background

Heterogeneity of reported outcomes can impact the certainty of evidence for prehabilitation. The objective of this scoping review was to systematically map outcomes and assessment tools used in trials of surgical prehabilitation.

Methods

MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsychInfo, Web of Science, CINAHL, and Cochrane were searched in February 2023. Randomised controlled trials of unimodal or multimodal prehabilitation interventions (nutrition, exercise, psychological support) lasting at least 7 days in adults undergoing elective surgery were included. Reported outcomes were classified according to the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research framework.

Results

We included 76 trials, mostly focused on abdominal or orthopaedic surgeries. A total of 50 different outcomes were identified, measured using 184 outcome assessment tools. Observer-reported outcomes were collected in 86% of trials (n=65), with hospital length of stay being most common. Performance outcomes were reported in 80% of trials (n=61), most commonly as exercise capacity assessed by cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Clinician-reported outcomes were included in 78% (n=59) of trials and most frequently included postoperative complications with Clavien–Dindo classification. Patient-reported outcomes were reported in 76% (n=58) of trials, with health-related quality of life using the 36- or 12-Item Short Form Survey being most prevalent. Biomarker outcomes were reported in 16% of trials (n=12) most commonly using inflammatory markers assessed with C-reactive protein.

Conclusions

There is substantial heterogeneity in the reporting of outcomes and assessment tools across surgical prehabilitation trials. Identification of meaningful outcomes, and agreement on appropriate assessment tools, could inform the development of a prehabilitation core outcomes set to harmonise outcome reporting and facilitate meta-analyses.

Keywords: enhanced recovery after surgery, perioperative outcomes, prehabilitation, rehabilitation, surgery

Editor's key points.

-

•

The evidence in support of prehabilitation for enhancing outcomes after surgery might be affected by heterogeneity of the outcomes measure reported.

-

•

This scoping review of randomised controlled trials of unimodal or multimodal prehabilitation interventions included 76 identified trials.

-

•

There is marked heterogeneity in reporting of outcomes across surgical prehabilitation trials.

-

•

Work is needed to identify meaningful outcomes and assessment tools that can inform development of a core outcomes set for future reporting and meta-analyses.

Every year, more than 300 million people require surgery.1 Major surgeries put patients under substantial physiological stress. To reduce this stress response, evidenced-based Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) pathways have been developed for more than 20 surgical specialties.2 Although these advances have improved recovery-related outcomes,3, 4, 5, 6 postoperative complications generally remain high. This sustained incidence of complications despite the introduction of evidenced-based perioperative surgical elements has prompted investigators to examine preoperative risk of postoperative morbidity, including modifiable patient-related factors.7 A large retrospective cohort (n=15,755) evaluating the relative contribution of the patient, surgeon, and hospital to postoperative clinical outcomes after elective colectomy (67.6% minimally invasive; 32.4% open) reported that preoperative patient factors contributed most to varying outcomes.8

Given that deviations from the ‘typical surgical trajectory’9 are highly associated with patients' preoperative status,8 there has been increasing interest in multimodal prehabilitation including preoperative exercise, psychological support, and nutritional interventions.7,10 A recent umbrella review of 55 systematic reviews of prehabilitation (n=381 individual studies) from 2004 to 2020 supported the effectiveness of prehabilitation (with moderate certainty) for improving functional recovery in patients with cancer undergoing surgery.11 Other positive effects of prehabilitation, such as reductions in postoperative complications, increases in the proportion of home discharges, and reductions of hospital length of stay (LOS), were graded with low or critically low certainty. The poor quality of the literature was explained by substantial methodological limitations of systematic reviews and primary studies, along with heterogeneity across interventions and reported outcomes. The authors concluded that key priorities to improve inconsistencies in prehabilitation evidence would be: (1) consensus for a core outcome set, (2) a common definition for surgical prehabilitation, and (3) additional high-quality studies.11 Heterogeneity in research reporting hinders the possibility to pool data together to support adequate meta-analyses of results, limiting the overall quality of the evidence to inform clinical practice and healthcare policies.12

Before developing a core outcome set for surgical prehabilitation, an important first step to guide consensus and achieve consistency is to have a clear understanding of what is currently being reported in prehabilitation trials. To address this gap, we conducted a scoping review with the purpose of systematically mapping outcomes reported across randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of unimodal (consisting of exercise, nutrition, or psychological support) and multimodal (two or more modalities) prehabilitation in adult patients undergoing elective surgery.

Methods

Design

To summarise and map the current prehabilitation literature, we conducted a scoping review. In contrast to a systematic review, a scoping review does not intend to critically appraise and summarise study results (related to a specific PICO: Population, Intervention, Control and Outcomes question), but rather provides an overview of how research is conducted, clarifies key concepts, or maps the evidence on broader topics within a specific field.13 Following the outlined framework by Arksey and O'Malley14 and recommendations of Levac and colleagues,13 this scoping review was performed in five key phases: (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) selecting studies, (4) charting the data, and (5) collating, summarising, and reporting the results. To develop the research questions and collect the appropriate information, an international and multidisciplinary team composed of prehabilitation health researchers and practitioners was established. The reporting of our findings followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist.15

Identifying the research question

The overarching objective of this scoping review was to systematically map outcomes in the surgical prehabilitation literature to inform the future development of a core outcome set to guide the conduct of future studies. Our research questions were: (1) what is the current landscape of outcomes and their specific outcome assessment tools across RCTs of unimodal (consisting of exercise, nutrition or psychological support) and multimodal (two or more modalities) prehabilitation lasting 7 days or more in adult patients undergoing elective surgery? (2) When and how were these specific outcome assessments reported?

Identifying relevant studies

As our primary goal was to map outcomes of surgical prehabilitation RCTs, we started by focusing our search to published ‘prehabilitation’ labelled (in the title, abstract, or keywords) trials, in which the participants were randomised (independent of the type and method of randomisation). We included trials that met the following working definition of prehabilitation16, 17, 18, 19: a unimodal intervention consisting of exercise, nutrition, or psychological support, or a multimodal intervention that combines exercise, nutrition, or psychological support with or without other interventions, undertaken for seven or more days before surgery (which is a period consistent with ERAS initiatives, not prehabilitation) to optimise patient preoperative condition and improve postoperative outcomes. The search strategy was created with the assistance of a librarian (GG; Supplementary Material 1) by following the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategy process.20 No date restriction was set to our search strategy, therefore all studies after 1946 were included. The first search was conducted on March 25, 2022,19 and was updated using the identical strategy with the same librarian on February 22, 2023, using MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsychInfo, Web of Science, CINAHL, and Cochrane (GG; Supplementary Material 1). Reference lists of all identified systematic reviews and meta-analyses of surgical prehabilitation were hand searched (DE and GDT) to include all relevant trials.

Study selection

Two independent reviewers used the Rayyan web-application (www.rayyan.ai, Cambridge, MA, USA) (in the initial search DE and GDT, for the updated search CG and CFG) to screen titles and abstracts for inclusion. Studies were considered for full-text review if the following criteria were met: (1) studies delivering a ‘prehabilitation’ labelled programme before surgery for adult patients (aged ≥18 yr) and in accordance with the above definition, and (2) were primary RCTs (including pilot and feasibility RCTs). Exclusion criteria were as follows: narrative reviews, editorials, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, scoping reviews, pooled analyses, secondary analyses, study protocols, consensus guidelines, conference abstracts, publications not in English or French, isolated medical treatments (e.g. medication management alone), and interventions conducted for <7 days before surgery. The reviewers then independently reviewed selected papers for full-text review. All disagreements were addressed by discussion until consensus was reached.

Charting the data

The research team collectively developed the data charting sheet (Excel, Microsoft 2010, Redmond, WA, USA). Both quantitative and qualitative data were extracted from the main manuscript and all referenced protocols and available Supplementary material. Quantitative data collection included baseline study (including author, year of publication, region, surgical specialty and cancer type, specifications of the intervention, primary outcomes), patient (sex or gender, risk stratification), and care characteristics (surgical approach, ERAS). Given that surgical outcomes vary based on individual patient characteristics (e.g. malnutrition), we also charted the reporting of patient characteristics for risk assessment.21,22

Outcomes were classified according to the conceptual framework of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR).23 Health outcomes were categorised as biomarkers, patient-reported, clinician-reported, observer-reported, and performance outcomes (see Table 1 for definitions). For each type of outcome, individual concepts of interest for measurement and their specific outcome assessments, also referred to as outcome measurement instruments,24 were identified. The ISPOR framework defines the concept of interest for measurement as what the outcome assessment intends to measure, while the specific outcome assessment is defined as the measuring instrument providing a rating or score (categorical or continuous) that represents some aspect of the patient's medical or health status.23 The term ‘outcome’ for concept of interest will be used to simplify terminology going forward; ‘outcome assessment’, ‘measurement instrument’ or ‘test’ will be used interchangeably to denote how the outcome was measured. As an example, health-related quality of life (concept of interest or outcome), can be measured using the EQ-5D questionnaire (specific outcome assessment or outcome measurement instrument). For each outcome, time points were collected and categorised according to the various phases of recovery as described by Lee and colleagues25 and modified by Gillis and colleagues.7 The pre-admission phase of recovery was defined as the time after completion of the prehabilitation intervention within a few days before surgery (i.e. this preoperative phase is a preparation for postoperative recovery),7 intermediate recovery was defined as the time from postanaesthesia care unit (PACU) discharge to discharge from hospital (i.e. within days after surgery), and late recovery described the phase from hospital discharge to return to the patient's usual function and activities (i.e. within weeks to months after surgery).25 Qualitative data collection included verbatim descriptions of how the identified outcomes assessments were collected.

Table 1.

Definitions and examples according to the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) framework.

| ISPOR terminology23 | Definition and alternative terminology | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Concept of interest for measurement |

|

Health-related quality of life (concept of interest for measurement) can be measured using the EQ-5D questionnaire (outcome assessment). |

| Outcome assessment |

|

|

| Clinical outcome assessment |

|

Any observer-, patient-, clinician-reported or performance outcomes. |

| Observer-reported outcome |

|

Hospital length of stay collected directly from a patient's medical chart. |

| Performance outcome |

|

Functional exercise capacity assessed with the 6-min walking test |

| Patient-reported outcome |

|

Anxiety and depression assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

| Clinician-reported outcome |

|

Complications classified according to the Clavien–Dindo grading system |

| Biomarker outcome |

|

Blood marker of glucose metabolism such as glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) |

After the first eight studies were extracted, the data charting form was reviewed by the multidisciplinary team to determine whether the approach was in accordance with the research question and adjustments were made accordingly. The charting form was continuously updated during the data extraction process to collect all reported outcomes from the studies. Three reviewers (CFG, NB, and LE) independently conducted data extraction, which was done in duplicate, and discrepancies were resolved by consensus discussion with senior authors (CG and LD).

Collating and summarising results

Outcomes (i.e. concepts of interest) and their specific outcome assessments (i.e. tests or instruments) were categorised according to the conceptual framework of the ISPOR task force report for clinical outcome assessments23 and according to the recovery periods described above.7,25 Quantitative data were analysed using descriptive statistics such as counts and frequencies. To map the current landscape of outcomes in surgical prehabilitation, type of outcome (biomarkers, patient-reported, clinician-reported, observer-reported, and performance outcomes and non-health-related outcome), individual outcomes and their assessments were counted. The total number of trials reporting a specific type of outcome were summarised as frequencies. However, given trials could have included more than one outcome assessment per outcome (e.g. quality of life measured with EQ-5D and 36-Item Short Form Survey), the denominator for outcome assessments was reported as the number of total outcome assessments per category and per individual outcome, rather than per trial. Outcomes were also stratified per surgical specialty. To map when outcomes were reported, timeframes per outcome type and per individual outcome (trials might have used multiple time points for one outcome) were counted. For the most prevalent outcomes, detailed qualitative descriptions were charted and analysed using summative content analysis to assess how they were reported.26 The members of the research team were consulted for the interpretation of the findings, mapping of the current state of reported outcomes, research gaps, and acknowledgment for future research opportunities.

Results

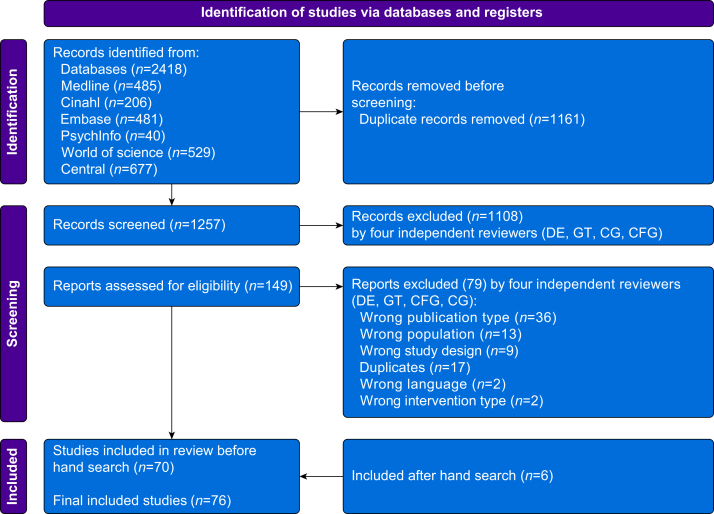

Our search identified 1257 unique articles (Fig. 1). After abstract screening, 149 articles were suitable for full-text review. A total of 79 articles were excluded because of publication type (n=36), population (n=13), study design (n=9), additional duplicates (n=17), language (n=2), and intervention type (n=2), leaving 70 articles. Hand searching produced six additional articles. A total of 76 articles were included in the final review (Supplementary Material 2).27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102

Fig 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Prehabilitation study and patient characteristics

Table 2 describes study and patient characteristics. Trials (n=76) were mostly conducted in Europe (n=35, 46%) and North America (Canada n=17, 22%; USA n=9, 12%). Only one trial was conducted across multiple countries (n=1, 1%). More than half were unimodal exercise interventions (n=41, 54%) and one-third were multimodal interventions (n=25, 33%). About one-quarter of RCTs (n=20, 26%) specified that they were conducted in an ERAS healthcare centre. The primary outcome was most frequently a performance outcome (n=26, 34%) or clinician-reported outcome (n=23, 30%). Only a few trials used a patient-reported (n=11, 15%), observer-reported outcome (n=3, 4%) or biomarker (n=2, 3%) as their primary outcome. Six studies specified multiple primary outcomes (n=6, 8%) and some did not specify a primary outcome (n=5, 7%). The sample included patients who underwent abdominal (n=26, 34%), orthopaedic (n=20, 26%), thoracic (n=14, 18%), cardiac (n=7, 9%), spinal (n=4, 5%), and other (n=5, 7%) surgeries. Of these trials, 46% were oncological-only resections (n=35) and 11% were mixed (n=8).

Table 2.

Baseline study and patient characteristics.

| Characteristics | Number of trials (n=76) n (%) |

|---|---|

| Study characteristics | |

| Country | |

| Europe | 35 (46) |

| Canada | 17 (22) |

| United States | 9 (12) |

| Asia | 10 (13) |

| Australia | 2 (3) |

| South America | 1 (1) |

| New Zealand | 1 (1) |

| Multiple countries | 1 (1) |

| Study design | |

| Primary RCT | 63 (83) |

| Pilot/feasibility RCT | 13 (17) |

| Type of prehabilitation program | |

| Exercise only | 41 (54) |

| Multimodal | 25 (33) |

| Nutrition only | 3 (4) |

| Cognitive only | 3 (4) |

| Respiratory only | 3 (4) |

| Pelvic floor training only | 1 (1) |

| Primary outcome | |

| Performance | 26 (34) |

| Clinician-reported | 23 (30) |

| Patient-reported | 11 (15) |

| Mixed | 6 (8) |

| Unclear/not specified | 5 (7) |

| Observer-reported | 3 (4) |

| Biomarker | 2 (3) |

| Enhanced Recovery After Surgery centre | |

| Yes | 20 (26) |

| No | 1 (1) |

| Not specified | 55 (72) |

| Patient characteristics | |

| Population included | |

| Oncological surgery | 35 (46) |

| Non-oncological surgery | 33 (43) |

| Mixed cohort | 8 (11) |

| Type of surgical population | |

| Abdominal surgery only | 26 (34) |

| Colorectal only | 16 (21) |

| Urological surgery only | 5 (7) |

| Hernia only | 1 (1) |

| Pancreatic only | 1 (1) |

| Hepatobiliary only | 1 (1) |

| Mixed abdominal | 2 (3) |

| Orthopaedic only | 20 (26) |

| Thoracic surgery | 14 (18) |

| Lung only | 12 (16) |

| Oesophageal only | 2 (3) |

| Cardiac surgery only | 7 (9) |

| Spinal surgery only | 4 (5) |

| Other | 5 (7) |

| Mixed cohort | 4 (5) |

| Breast only | 1 (1) |

Almost two-thirds of trials reported the surgical techniques used (e.g. minimally invasive surgery) (n=50, 66%) but few reported anaesthesia techniques (e.g. general anaesthesia) (n=6, 8%). To characterise patients at baseline, more than half used at least one graded comorbidity risk assessment tool (n=39, 51%) (e.g. n=35, 46% American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification system or n=12, 16% Charlson Comorbidity Index), and about one-third used a specific disease-related risk assessment tool (n=26, 34%) (e.g. n=9, 12% New York Heart Association Functional Classification or n=3, 4% ColoRectal Physiological and Operative Severity Score). Of the RCTs that included patients living with cancer (n=43), 58% reported the cancer stage (n=25/43) of their sample. Almost all trials reported the sex or gender (n=75, 98.7%) of participants (sex n=34, 45%; gender n=24, 32%; unclear n=17, 22%), but most did not explain how it was collected or defined (n=70, 92%).

Reported outcomes according to the ISPOR framework

We identified a total of 48 health and two non-health related outcomes (i.e. concepts of interest) across the 76 surgical prehabilitation RCTs. A total of 184 specific outcome assessments that included 164 clinical outcome assessments (including all assessment methods, instruments, and tests) and 20 unique biomarkers were reported (Table 3 and Supplementary Material 3).

Table 3.

Types of reported outcome assessments according to the ISPOR framework.

| Type of outcome assessments according to the ISPOR framework∗ | Total times reported across trials | Number of different outcome assessments | Number of trials reporting the outcome assessment (n=76) (n, %) | Description of timeframe according to phases of recovery† | Number of times an outcome was reported in a specific timeframe‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance outcome | 199 | 51 | 61 (80) | Pre-admission | 115 |

| Intermediate/hospital stay | 12 | ||||

| Late ≤30 days | 34 | ||||

| Late ≤90 days | 61 | ||||

| Late >90 days | 36 | ||||

| Observer-reported outcome | 175 | 24 | 65 (86) | Pre-admission | 18 |

| Intermediate/hospital stay | 59 | ||||

| Late ≤30 days | 41 | ||||

| Late >30 to ≤90 days | 16 | ||||

| Late >90 days | 5 | ||||

| Patient-reported outcome | 137 | 63 | 58 (76) | Pre-admission | 92 |

| Intermediate/hospital stay | 10 | ||||

| Late ≤30 days | 53 | ||||

| Late >30 to ≤90 days | 106 | ||||

| Late >90 days | 54 | ||||

| Clinician-reported outcome | 84 | 26 | 59 (78) | Pre-admission | 13 |

| Intermediate/hospital stay | 22 | ||||

| Late ≤30 days | 37 | ||||

| Late >30 to ≤90 days | 18 | ||||

| Late >90 days | 8 | ||||

| Biomarker outcome | 28 | 20 | 12 (16) | Pre-admission | 8 |

| Intermediate/hospital stay | 6 | ||||

| Late >30 to ≤90 days | 2 | ||||

| Late ≤90 days | 4 | ||||

| Late >90 days | 0 |

ISPOR, International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research. ∗Individual trials may have reported multiple outcomes within each type. †Phases of recovery: pre-admission: preparation period before surgery (after the prehabilitation intervention)7; intermediate: from after the post-anaesthesia care unit to discharge from hospital; late: from hospital discharge to return to the patient's usual function and activities.25‡Trials may have collected multiple outcomes per timeframe.

Observer-reported outcomes

Nearly all trials reported at least one observer-reported outcome (n=65/76, 86%), which were commonly reported during the intermediate/hospital stay (n=57/65) and late phases of recovery, mostly ≤30 days after surgery (n=41/65). Observer-reported outcomes were reported 175 times using 24 outcome assessments (Table 3). The most frequent outcomes were hospital LOS (n=52/175, 30%), hospital readmissions (n=24/175, 14%) and postoperative mortality (n=23/175, 13%). Both hospital LOS and postoperative mortality were measured using four different approaches. Among the trials that measured LOS (n=52), 89% (n=46/52) defined LOS as the number of days from surgery to hospital discharge, whereas 8% (n=4/52) included total time (in days) from preoperative admission until hospital discharge after surgery, and 4% (n=2/52) also reported the cumulative hospital LOS over a 30- or 90-day period. Postoperative mortality was mostly reported independently (n=15/23, 65%) or as part of a composite score such as grade V complication of the Clavien–Dindo classification (n=6/23, 26%). Of all observer-reported outcomes, discharge location was the most infrequently reported (n=6/175, 3%) (Supplementary Material 3).

Performance outcomes

At least one performance outcome was identified in 80% of RCTs (n=61/76). Of these trials (n=61), one or more performance outcomes was measured during the pre-admission recovery phase (preoperative period after the prehabilitation intervention) (n=115/61) and during the late phase of recovery, mostly within 30–90 days after surgery (n=61/61). In total, performance outcomes were reported 199 times using 51 specific outcome assessments (including tests) across trials (Table 3). Of all performance outcomes, exercise capacity during cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) (n=43/199, 22%), strength (n=34/199, 17%), functional exercise capacity (n=33/199, 17%), and pulmonary function (n=33/199, 17%) were the most frequently reported. Ten different outcome assessments were identified to measure exercise capacity during CPET (n=43 trials). Tests were all conducted on an electromagnetically braked cycle ergometer with breath-by-breath gas exchange collected throughout an incremental load exercise protocol until volitional exhaustion. Peak oxygen (VO2 peak) consumption was the most prevalent assessment (n=12/43, 28%), followed by peak workload (n=8/43, 19%) and oxygen consumption at the anaerobic threshold (AT) (VO2 at AT) (n=8/43, 19%). Of the trials that measured VO2 peak or VO2 at AT, 33% (n=4/12) and 63% (n=5/8) explicitly followed the POETTS consensus, respectively.103 Thirty-eight percent (n=3/8) reported how peak workload was collected and all studies used different methods (e.g. peak workload was collected during the last 30 s up to the last 2 min of CPET) (Table 4). Nine different outcome assessments were used to describe strength (n=34), which included handgrip (n=10/34, 29%), quadriceps (n=10/34, 29%), and hamstrings strength (n=4/34, 12%). Functional exercise capacity (n=33) was most commonly measured using the 6-min walk test (6MWT) (n=32/33, 97%), with one study using the 5-min walk test (5MWT). Of those using the 6MWT, more than half (n=18/32, 56%) referenced or explicitly reported following the American Thoracic Society 2002105 or European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society 2014 consensus guidelines.106 Despite reporting use of the consensus guidelines, the 6MWT was conducted on different length tracks such as hallways of 10 m (n=1/32, 3%), 15 m (n=4/32, 13%), 20 m (n=3/32, 9%), and 30 m (n=2/32, 6%), and on an oval continuous 36 m track (n=1/32, 3%) and a treadmill (n=1/32, 3%) (Table 4). Nine different pulmonary function tests were reported with the most common being the forced vital capacity and forced expiratory volume in 1 s (both n=9/33, 27%). Gait speed (n=4/199, 2%), balance, and physical function using the composite measure Short Physical Performance Battery (n=3/199, 2%) were the least reported performance outcomes (Supplementary Material 3).

Table 4.

Qualitative description of common outcome assessments.

| Outcome | Common guidelines | Specific outcome assessments | Qualitative description | Frequency per outcome assessment (n, %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exercise capacity by CPET (n=43) | VO2 peak (n=12/43) | Defined as the average oxygen consumption over the last 20 s of peak load | 2/12 (17) | |

| Defined as the average oxygen consumption over the last 30 s of peak load | 4/12 (33) | |||

| Defined as oxygen consumption over the last 20–30 s of peak load and reaching a heart rate >95% of predicted and a respiratory exchange ratio >1.1 at peak exercise | 3/12 (25) | |||

| Not defined | 3/12 (25) | |||

| Peak workload (n=8/43) | Not defined | 5/8 (63) | ||

| Defined as workload maintained for the last 30 s | 1/8 (13) | |||

| Defined as workload maintained for the last 1 min | 1/8 (13) | |||

| Defined as workload maintained for the last 2 min | 1/8 (13) | |||

| VO2 at AT (n=8/43) | Defined using the three-criterion discrimination technique | 5/8 (63) | ||

| Not defined | 3/8 (38) | |||

| Strength (n=34) |

|

Handgrip strength (n=10/34) | Defined as maximal voluntary isometric contractions measured with a handheld dynamometer across measurements (e.g. maximum score of 3 trials) | 8/10 (80) |

| Not defined | 2/10 (20) | |||

| Lower body strength (n=18/34) | Defined as maximal voluntary isometric contractions measured with a dynamometer | 12/18 (67) | ||

| Defined as 1 to 6 RM on leg extension | 2/18 (11) | |||

| Defined as 1 to 6 RM on leg press | 2/18 (11) | |||

| Defined as 1 to 6 RM on leg curl | 1/18 (6) | |||

| Conducted with load cell | 1/18 (6) | |||

| Functional exercise capacity (n=33) | 6MWT (n=32/33) | Conducted in a 15 m hallway | 4/32 (13) | |

| Conducted in a 20 m hallway | 3/32 (9) | |||

| Conducted in a 30 m hallway | 2/32 (6) | |||

| Conducted in a 10 m hallway | 1/32 (3) | |||

| Conducted on a treadmill | 1/32 (3) | |||

| Conducted in a 36 m oval indoor course | 1/32 (3) | |||

| Not specified | 20/32 (63) | |||

| 5MWT (n=1/33) | Not specified | 1/1 (100) | ||

| Postoperative complications (n=51) |

|

Listed complications individually | 22/51 (43) | |

| Described severity/grading stratification (e.g. severe complications defined as CCI score >20) | 12/51(24) | |||

| Defined complications as ‘any deviation from the normal postoperative course’ | 5/51 (10) | |||

| Collected and defined postoperative pulmonary complications (PPC) (e.g. common criteria were: pneumonia confirmed by new infiltrates by X-ray imaging, WBC, temperature >38.5°C and purulent sputum, atelectasis, bronchopleural fistula, pleural effusion, prolonged chest tube (>7 days), prolonged mechanical vent [>24 h]). | 4/51 (8) | |||

5MWT, 5-min walk test; 6MWT, 6-min walk test; AT, anaerobic threshold; CPET, cardiorespiratory exercise testing; MICMD, minimally important clinical meaningful difference; RM, repetition maximum; VO2, oxygen consumption; WBC, white blood cells.

Patient-reported outcomes

At least one patient-reported outcome was included in 76% (n=58/76) of trials. Patient-reported outcomes were reported at multiple time points, including during the pre-admission recovery phase (n=92/58) and during the late recovery phase, mostly within 30–90 days after surgery (n=106/58). Of all outcome types, patient-reported outcomes were most frequently reported in the late recovery phase >90 days after surgery (n=54/58). Patient-reported outcomes were reported a total of 137 times using 63 unique instruments (Table 3). Health-related or general quality of life, reported in 22% (n=30/137) of trials, was measured using four different measurement instruments including the Short Form Survey (SF-12 or SF-36) (n=20/30, 67%), EQ-5D (EQ-5D-3L or -5L) (n=8/30, 27%), Quality of Well Being scale (n=1/30, 3%), and 15-dimensional instrument of health-realted qualtiy of life (n=1/30, 3%). Disease-specific quality of life was the second most common outcome (n=23/137, 17%) and was measured with 14 different instruments which included the EORTC QLQ-C30 (n=6/23, 26%), the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (all versions combined) (n=3/23, 13%), and the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis for orthopaedic surgery (n=5/23, 22%). Anxiety and depression were measured in 15% of trials (n=21/137) using six different instruments including the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (n=15/21, 71%) and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (n=2/21, 10%). Infrequent patient-reported outcomes were self-reported disability (n=8/137, 6%), patient treatment satisfaction (n=5/137, 4%), self-efficacy (n=5/137, 4%), and self-reported recovery (n=5/137, 4%) (Supplementary Material 3).

Clinician-reported outcomes

Seventy-seven percent (n=59/76) of trials included one or more clinician-reported outcome, which were mostly reported during the intermediate/hospital stay (n=22/59) and late phase of recovery, within 30 days (n=37/59). Very few RCTs reported clinician-reported outcomes in the late phase of recovery >90 days after surgery (n=8/59). Clinician-reported outcomes were reported 84 times overall using 26 specific outcome assessments (Table 3). Postoperative complications represented 61% of all clinician-reported outcomes (n=51/84). Almost half the trials reporting complications used the Clavien–Dindo classification (n=24/51, 47%), others used the Comprehensive Complication Index (n=8/51, 16%) or the Postoperative Morbidity Survey (n=2/51, 4%). Complications were stratified by graded severity (n=25/51, 49%), major/minor complications (n=9/51, 18%), surgical complications (n=6/51, 12%), medical complications (n=5/51, 10%), or provided frequencies of each individual complication (n=22/51, 43%) (Table 4). Twenty percent of trials (n=15/76) used at least one clinician-oriented nutrition measure such as nutritional status or dietary intake to describe baseline characteristics of patients or conduct a risk stratification for their intervention. However, very few reported a nutrition-related outcome post-prehabilitation (for nutritional status: n=3/84, 4%; for dietary intake: n=4/84, 5%). Time to achieve hospital discharge criteria (n=4/84, 3%), independence, and cognitive function (both n=2/84, 2%) were also reported infrequently (Supplementary Material 3).

Biomarker outcomes

Of the 76 RCTs, 12 reported at least one biomarker outcome (n=12/76, 16%). Biomarkers were measured mostly during the preoperative period (n=8/12) and during the intermediate/hospital stay phase of recovery (n=6/12). Biomarkers were reported a total of 28 times using 20 different biomarkers (Table 3). Inflammatory markers (n=11/28, 39%) were the most prevalent outcome, which was measured using seven unique biomarkers such as C-reactive protein (n=3/11, 27%), interleukin-6 (n=2/11, 18%) and tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) (n=2/11, 18%) (Supplementary Material 3).

Non-health outcomes

Adherence to prehabilitation interventions was collected in 70% of trials (n=53/76), but only 62% (n=47/76) reported the actual adherence data in their manuscript. Finally, 8% (n=6/76) reported a cost analysis-related outcome using all different assessment methods including cost of postoperative health service utilisation, cost of prehabilitation vs the cost of rehabilitation, in-hospital expenses such as daily nursing care fees, surgery-related expenses, and drug costs.

Reported outcomes according to surgical type

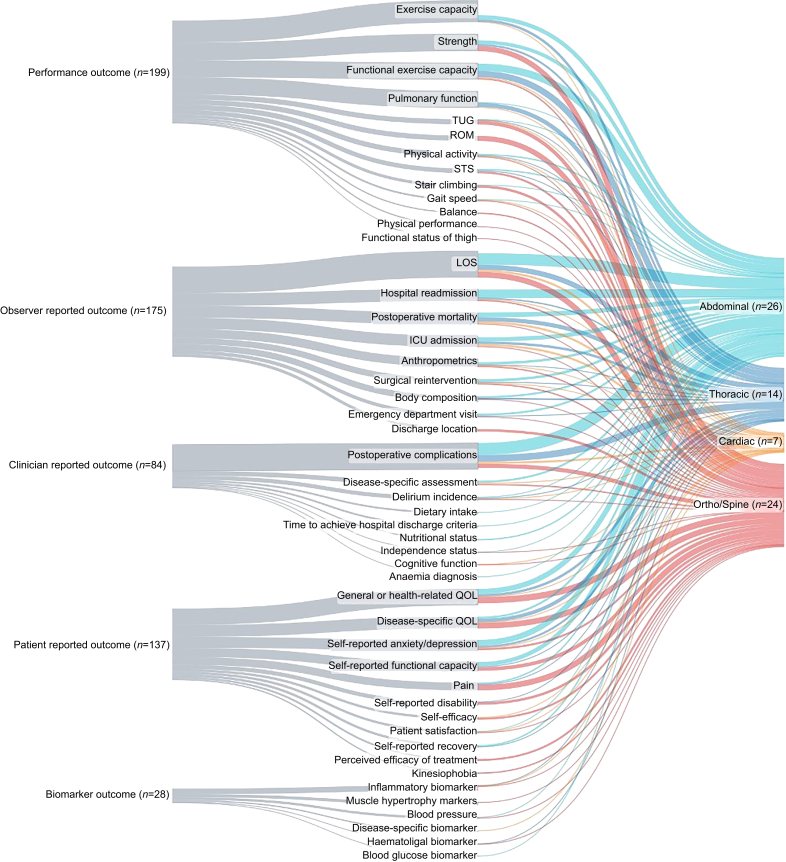

Figure 2 (and Supplementary Material 3) illustrates reported outcomes stratified by surgical specialty including abdominal (n=26), thoracic (n=14), cardiac (n=7), orthopaedic and spinal (n=24), and other (n=5) procedures. More than 80% of abdominal (n=26) and thoracic (n=14) surgeries reported at least one performance outcome, clinician-reported outcome, and observer-reported outcome with the most prevalent being functional exercise capacity, postoperative complications, and hospital LOS. At least one patient-reported outcome was reported in 81% of abdominal (n=21/26) and 71% of thoracic (n=10/14) surgeries, mostly as self-reported anxiety and depression and disease-specific quality of life. Almost all cardiac (n=7) prehabilitation trials included clinician-reported outcomes and observer-reported outcomes (n=6/7, 86%) of which postoperative complications, hospital LOS, intensive care unit admissions, and postoperative mortality were equally as prevalent (n=4/7, 57%). In general, orthopaedics and spinal surgeries (n=24) reported performance outcomes (n=19/24, 79%) as strength and range of motion (both n=10/24, 41.7%), observer-reported outcomes (n=17/24, 71%) as hospital LOS (n=10/24, 46%), and patient-reported outcomes (n=22/24, 92%) as health-related quality of life (n=12/24, 50%). Adherence was reported in most trials of abdominal procedures (n=22/26, 85%) and other surgical procedures (n=5/5, 100%). Cost analysis was infrequently reported among all surgical specialties with the highest rate being in orthopaedics and spinal (n=4/24, 17%).

Fig 2.

Sankey diagram describing the types of outcomes and concept of interest for measurement (outcome) using the ISPOR framework per surgical type.

ICU, intensive care unit; ISPOR, International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research; LOS, length of stay; QOL, quality of life; ROM, range of motion; STS, sit to stand; TUG, timed up and go.

Discussion

This scoping review of prehabilitation RCTs in adults undergoing surgery provides a comprehensive overview of all reported outcomes and the most frequently used outcome assessments (including instruments and test) across time points. The most striking finding is the heterogeneity of outcomes used to assess the efficacy of surgical prehabilitation. Using the ISPOR framework to categorise reported outcomes,23 we identified a total of 50 different outcomes (48 health and two non-health-related) using a total of 184 specific outcome assessments across 76 trials of surgical prehabilitation. Among all RCTs, the most common outcome was hospital LOS. Most trials (86%) reported at least one observer-reported outcome. We identified 24 different outcome assessments classified as observer-reported outcomes. Performance outcomes were reported in 80% of trials using a total of 51 different assessment tests. The most reported performance outcomes were measures of functional capacity such as exercise capacity assessed with CPET parameters and functional exercise capacity assessed with the 6MWT. Patient-reported outcomes were also prevalent across RCTs as they were reported in 76% of trials using 63 different outcome measurement instruments. The most commonly reported patient-reported outcome was generic health-related quality of life. Clinician-reported outcomes were reported in 78% of trials using 26 different outcome assessments with postoperative complications being the most reported.

Our findings indicate there is a great deal of variation in trial outcomes and lack of consistency in instruments, tests, and assessment methods used to measure these outcomes. Patient-reported outcomes were the most heterogeneous as they were captured with the greatest range of instruments; we identified two to 14 per outcome. Although use of several instruments may be necessary to capture a breadth of patient experience and outcome, measurement heterogeneity was identified among instruments measuring the same concept of interest. For example, self-reported anxiety and depression was assessed using six different instruments (Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale, Patient Health Questionnaire-9, Geriatric Depression Scale, Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale, Cardiac Anxiety Questionnaire, Beck Depression Inventory). These findings are not unique to prehabilitation. In fact, systematic reviews of health research/clinical trials have captured a large diversity of outcome reporting in oncological research,110 ulcerative colitis,111 cardiac arrest,112 and COVID-19 clinical studies.113 For example, a systematic review of RCTs of women living with stress-related urinary incontinence found a total of 119 different outcome assessments among the 108 trials included.114 Moreover, a systematic review of patient-reported outcomes in colorectal cancer surgery (n=104 studies, including RCTs and non-randomised studies) identified 58 different instruments,115 which is comparable to the 63 patient-reported outcomes identified in our scoping review.

Overall, the most prevalent outcome was hospital LOS, which was reported a total of 52 times. In most cases, hospital LOS was assessed as the number of days from surgery to discharge; however, some included pre-admission days and others combined the number of days patients remained in the hospital at 30 or 90 day after surgery. Furthermore, hospital LOS might not accurately reflect how prehabilitation affects the intermediate phase of recovery from a biological or physiological point of view25 as it can be influenced by institutional policies and culture, patient expectations, and availability for postoperative support.116,117 Readiness for (hospital) discharge, which is defined as the time from the day of surgery until the achievement of prespecified criteria (e.g. tolerance of oral intake, ability to mobilise and perform self-care),118 might be a more appropriate index of intermediate postoperative recovery,25,117,119 useful for explanatory trials, but was rarely reported in prehabilitation RCTs.

Performance outcomes measuring functional capacity were frequently reported among prehabilitation trials. These outcomes included exercise capacity (also known as aerobic capacity or exercise tolerance) assessed as VO2 peak or VO2 at AT during CPET, and functional exercise capacity measured almost exclusively with the 6MWT. Exercise capacity (CPET parameters) and functional exercise capacity (6MWT) were predominately measured during the pre-admission phase of recovery and only functional exercise capacity was commonly measured after hospital discharge ≤90 day after surgery (late phase of recovery). In our scoping review, most trials used CPET to assess changes in participants' fitness level after the prehabilitation intervention, while some used it to personalise aerobic exercise prescriptions28,32,74 and a few used it as a risk assessment method.31,84

CPET is the gold standard for objectively measuring aerobic exercise capacity and both the VO2 peak and AT are impacted by exercise training before surgery.120 However, CPET requires specialist equipment and expertise and not all centres may have access to it. The 6MWT can alternatively be used to evaluate the impact of therapeutic exercise interventions and does not require specialist equipment.121 Whichever measure of performance is used, it is essential that appropriate standardised methodology is used to ensure the correct interpretation and reproducibility of findings. In our review only half of the trials that reported CPET variables or used the 6MWT reported following the Perioperative Exercise Testing and Training Society consensus definitions for CPET103 or the American Thoracic Society or European Respiratory Society guidelines for the 6MWT.105,106 This is a concern because the method used to identify the AT can impact the reported value in a significant and clinically meaningful way.122 Furthermore, although guidelines state that the 6MWT should be performed indoors, along a flat, straight, hard surfaced and enclosed hallway no less than 20 m long, we found that trials conducted 6MWT in hallways ranging from 10 to 30 m, and on an oval continuous track and treadmill. A crossover RCT (n=21) comparing the 6MWT conducted in a hallway vs on a treadmill, found a significant difference between the distance walked by individual participants, suggesting these surfaces are not interchangeable nor comparable.123 Moreover, 63% of trials performing the 6MWT did not provide any details on how it was measured, limiting the reader's ability to assess for measurement bias.

Altogether, our findings indicate that surgical prehabilitation trials report a wide range of outcomes and outcome assessments, some of which are uncommon or non-validated, during the pre-admission, intermediate, and late phases of recovery. Although the evaluation of prehabilitation, which is a complex intervention,124 goes far beyond use of a single outcome, such heterogeneity across RCTs poses challenges to compare, contrast, and combine data together to reach strong and reliable conclusions.110 A possible strategy to mitigate these challenges is the development of a core outcome set (in collaboration with patients), which is an agreed standardised minimal collection of outcomes that should be measured and reported in trials of a specific field.125 The development of a core outcome set was a key priority identified by authors of a collaborative international Delphi study identifying the top research priorities in prehabilitation.126 In addition to guiding ‘what’ to measure and report, the selection of universally accepted and validated outcome assessments (measurement instruments, tests) and of appropriate recovery periods are crucial for mitigating the heterogeneity of ‘how’ and ‘when’ a given outcome is measured. The Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) and the Consensus-based Standards for the selection of health status Measurement Instruments (COSMIN) initiatives have developed guidelines on how to select relevant outcome assessments for core outcomes. These guidelines include the following four steps: (1) agree on detailed constructs (outcomes) to be measured for specific populations, (2) find all existing outcome assessments used for these constructs (such as our scoping review), (3) conduct a feasibility and quality assessment for the selection of outcome assessments, and (4) perform a consensus procedure for selecting core outcomes by including all relevant stakeholders.24 Developing a core outcome set with all important stakeholders, can increase consistency and facilitate the synthesis and pooling of meaningful outcomes for meta-analyses to ultimately guide clinical decision-making, care guidelines, and policy.125,127

Finally, high-quality healthcare should be safe, effective, and improve the patient experience.128 Yet, surgical research has historically focused on clinician-oriented (e.g. LOS, complications) rather than patient-oriented outcomes (e.g. quality of life).119 An international qualitative study on patient-defined recovery suggested that the traditional clinical outcomes important to clinicians and healthcare administrators are noticeably absent from patient definitions of successful recovery as patients value resolution of symptoms and return to daily activities after abdominal surgery.129 Our review suggests that traditional clinical outcomes continue to dominate the literature; however, in the field of surgical prehabilitation, patient-reported and performance outcomes are also quite prominent. It should be noted that, while this review is focused on outcome reporting, knowledge translation of prehabilitation trials into clinical practice requires comprehensive evaluation of whether (and how) the intervention is acceptable to stakeholders (including patients), cost-effective, implementable, and transferable across different patient populations.124

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first scoping review to systematically map outcomes and their outcome assessments of primary RCTs of surgical prehabilitation. Having a comprehensive understanding of what, when, and how outcomes are reported in the current literature is an important first step to guide consensus and achieve consistency of measurement in future research.125 All stages of the search, data extraction, and charting were conducted in duplicate by independent reviewers who followed Arksey and O'Malley's framework,14 and Levac and colleagues' recommendations13 for performing scoping reviews. The findings of this review are reported in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR checklist.15 Furthermore, the search strategy was conducted with the assistance of an experienced academic librarian (Supplementary Material 1). However, this scoping review is not without limitations. Firstly, given there is no universally accepted definition of prehabilitation, we included trials labelled as ‘prehabilitation’ (in title, abstract or keywords) and met our prespecified criteria describing prehabilitation. Secondly, we only included trials published in English and French, which could explain why the majority of the trials included were performed in Europe and North America, and may have resulted in the potential exclusion of relevant preoperative RCTs. Thirdly, we mapped outcomes according to the ISPOR framework which involves subjective categorisation. To mitigate bias, a multidisciplinary team composed of dietitians, physiotherapists, physicians, and health researchers collaborated during all steps of our scoping review. Fourthly, commonly used outcome assessments do not necessarily reflect consensus or accuracy and validity of the outcome that trials intended to measure. Finally, contrary to exercise and other modalities (psychological support, respiratory), the nutrition modality was poorly reported. For instance, nutrition-related outcomes such as nutritional status, anthropometrics and body composition, and dietary intake, other than for baseline measures, were infrequently reported at follow-up points making it challenging to evaluate.

Conclusions

This scoping review identified 50 different reported outcomes among surgical prehabilitation RCTs. These outcomes were measured using 184 outcome assessments (including all assessment methods, instruments, tests) across diverse time points. These results highlight the importance of identifying common, meaningful, and valid outcomes for both patients and health systems, and for developing a core outcome set to harmonise data reporting and enable meta-analyses of trial effects.

Authors’ contributions

Contributed to the study design: CFG, JFF, DIM, SC, JM, MPG, RC, DL, CSB, FC

Data acquisition: CFG, DE, GDT

Statistical analysis: CFG

Drafted the manuscript, figures, and tables: CFG

Co-designed the study, provided their expertise and guidance throughout: CG, LD

Edited the manuscript: CG, LD, NB, LE, DE, GDT

Data extraction: NB, LE

Data interpretation, and editing of the final manuscript: JFF, DIM, SC, JM, MPG, RC, DL, CSB, FC

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Genevieve Gore, Liaison Librarian, Schulich Library of Physical Sciences, Life Sciences, and Engineering, McGill University, for her assistance with developing and conducting the search strategy for this scoping review.

Declarations of interest

CG has received honoraria for giving educational talks sponsored by Abbott Nutrition, Nestle Nutrition, and Fresenius Kabi, which were unrelated to this manuscript. MPG is a member of the board of the British Journal of Anaesthesia.

Funding

There was no explicit funding for the development of this review. DIM receives salary support from The Ottawa Hospital Anesthesia Alternate Funds Association, the University of Ottawa Faculty of Medicine, and Physician Services Inc. MPG is supported in part by the NIHR (UK) Southampton Biomedical Research Centre and as part of the NIHR (UK) Senior Investigator Scheme.

Handling Editor: Hugh C Hemmings Jr

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2024.01.046.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Rose J., Weiser T.G., Hider P., Wilson L., Gruen R.L., Bickler S.W. Estimated need for surgery worldwide based on prevalence of diseases: a modelling strategy for the WHO Global Health Estimate. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3:S13–S20. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)70087-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ljungqvist O., De Boer H.D., Balfour A., et al. Opportunities and challenges for the next phase of enhanced recovery after surgery: a review. JAMA Surg. 2021;156:775–784. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.0586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lau C.S., Chamberlain R.S. Enhanced recovery after surgery programs improve patient outcomes and recovery: a meta-analysis. World J Surg. 2017;41:899–913. doi: 10.1007/s00268-016-3807-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Visioni A., Shah R., Gabriel E., Attwood K., Kukar M., Nurkin S. Enhanced recovery after surgery for noncolorectal surgery? A systematic review and meta-analysis of major abdominal surgery. Ann Surg. 2018;267:57–65. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhuang C.-L., Ye X.-Z., Zhang X.-D., Chen B.-C., Yu Z. Enhanced recovery after surgery programs versus traditional care for colorectal surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:667–678. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182812842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nelson G., Kiyang L.N., Crumley E.T., et al. Implementation of Enhanced Recovery after Surgery (ERAS) across a provincial healthcare system: the ERAS Alberta colorectal surgery experience. World J Surg. 2016;40:1092–1103. doi: 10.1007/s00268-016-3472-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gillis C., Ljungqvist O., Carli F. Prehabilitation, enhanced recovery after surgery, or both? A narrative review. Br J Anaesth. 2022;128:434–448. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2021.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bamdad M.C., Brown C.S., Kamdar N., Weng W., Englesbe M.J., Lussiez A. Patient, surgeon, or hospital: explaining variation in outcomes after colectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2022;234:300–309. doi: 10.1097/XCS.0000000000000063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carli F., Zavorsky G.S. Optimizing functional exercise capacity in the elderly surgical population. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2005;8:23–32. doi: 10.1097/00075197-200501000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Macmillan Cancer Support Principles and guidance for prehabilitation. 2019. https://www.macmillan.org.uk/healthcare-professionals/news-and-resources/guides/principles-and-guidance-for-prehabilitation [cited October 1st 2023]. Available from:

- 11.McIsaac D.I., Gill M., Boland L., et al. Prehabilitation in adult patients undergoing surgery: an umbrella review of systematic reviews. Br J Anaesth. 2021;128:244–257. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2021.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffmann T.C., Glasziou P.P., Boutron I., et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348:g1687. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levac D., Colquhoun H., O'Brien K.K. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:69. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arksey H., O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tricco A.C., Lillie E., Zarin W., et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scheede-Bergdahl C., Minnella E.M., Carli F. Multi-modal prehabilitation: addressing the why, when, what, how, who and where next? Anaesthesia. 2019;74(Suppl 1):20–26. doi: 10.1111/anae.14505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luther A., Gabriel J., Watson R.P., Francis N.K. The impact of total body prehabilitation on post-operative outcomes after major abdominal surgery: a systematic review. World J Surg. 2018;42:2781–2791. doi: 10.1007/s00268-018-4569-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gillis C., Buhler K., Bresee L., et al. Effects of nutritional prehabilitation, with and without exercise, on outcomes of patients who undergo colorectal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:391–410.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Engel D., Testa G., McIsaac D., et al. Reporting quality of randomized controlled trials in prehabilitation: a scoping review. Perioper Med. 2023;12:48. doi: 10.1186/s13741-023-00338-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGowan J., Sampson M., Salzwedel D.M., Cogo E., Foerster V., Lefebvre C. PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferreira V., Lawson C., Gillis C., Scheede-Bergdahl C., Chevalier S., Carli F. Malnourished lung cancer patients have poor baseline functional capacity but show greatest improvements with multimodal prehabilitation. Nutr Clin Pract. 2021;36:1011–1019. doi: 10.1002/ncp.10655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gillis C., Fenton T.R., Gramlich L., et al. Malnutrition modifies the response to multimodal prehabilitation: a pooled analysis of prehabilitation trials. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2022;47:141–150. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2021-0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walton M.K., Powers J.H., 3rd, Hobart J., et al. Clinical outcome assessments: conceptual foundation-report of the ISPOR clinical outcomes assessment - emerging good practices for Outcomes Research Task Force. Value Health. 2015;18:741–752. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2015.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prinsen C.A., Vohra S., Rose M.R., et al. How to select outcome measurement instruments for outcomes included in a “Core Outcome Set”–a practical guideline. Trials. 2016;17:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s13063-016-1555-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee L., Tran T., Mayo N.E., Carli F., Feldman L.S. What does it really mean to “recover” from an operation? Surgery. 2014;155:211–216. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hsieh H.-F., Shannon S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.An J., Ryu H.K., Lyu S.J., Yi H.J., Lee B.H. Effects of preoperative telerehabilitation on muscle strength, range of motion, and functional outcomes in candidates for total knee arthroplasty: a single-blind randomized controlled trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:6071. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18116071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Argunova Y., Belik E., Gruzdeva O., Ivanov S., Pomeshkina S., Barbarash O. Effects of physical prehabilitation on the dynamics of the markers of endothelial function in patients undergoing elective coronary bypass surgery. J Pers Med. 2022;12:471. doi: 10.3390/jpm12030471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ausania F., Senra P., Melendez R., Caballeiro R., Ouvina R., Casal-Nunez E. Prehabilitation in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2019;111:603–608. doi: 10.17235/reed.2019.6182/2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barberan-Garcia A., Ubre M., Roca J., et al. Personalised prehabilitation in high-risk patients undergoing elective major abdominal surgery: a randomized blinded controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2018;267:50–56. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berkel A.E.M., Bongers B.C., Kotte H., et al. Effects of community-based exercise prehabilitation for patients scheduled for colorectal surgery with high risk for postoperative complications: results of a randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2022;275:e299–e306. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blackwell J.E.M., Doleman B., Boereboom C.L., et al. High-intensity interval training produces a significant improvement in fitness in less than 31 days before surgery for urological cancer: a randomised control trial. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2020;23:696–704. doi: 10.1038/s41391-020-0219-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bousquet-Dion G., Awasthi R., Loiselle S.E., et al. Evaluation of supervised multimodal prehabilitation programme in cancer patients undergoing colorectal resection: a randomized control trial. Acta Oncol. 2018;57:849–859. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2017.1423180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brown K., Loprinzi P.D., Brosky J.A., Topp R. Prehabilitation influences exercise-related psychological constructs such as self-efficacy and outcome expectations to exercise. J Strength Cond Res. 2013;28:201–209. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e318295614a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown K., Topp R., Brosky J.A., Lajoie A.S. Prehabilitation and quality of life three months after total knee arthroplasty: a pilot study. Percept Mot Skills. 2012;115:765–774. doi: 10.2466/15.06.10.PMS.115.6.765-774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Calatayud J., Casana J., Ezzatvar Y., Jakobsen M.D., Sundstrup E., Andersen L.L. High-intensity preoperative training improves physical and functional recovery in the early post-operative periods after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25:2864–2872. doi: 10.1007/s00167-016-3985-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carli F., Bousquet-Dion G., Awasthi R., et al. Effect of multimodal prehabilitation vs postoperative rehabilitation on 30-day postoperative complications for frail patients undergoing resection of colorectal cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2020;155:233–242. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.5474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carli F., Charlebois P., Stein B., et al. Randomized clinical trial of prehabilitation in colorectal surgery. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1187–1197. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cavill S., McKenzie K., Munro A., et al. The effect of prehabilitation on the range of motion and functional outcomes in patients following the total knee or hip arthroplasty: a pilot randomized trial. Physiother Theory Pract. 2016;32:262–270. doi: 10.3109/09593985.2016.1138174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dunne D.F., Jack S., Jones R.P., et al. Randomized clinical trial of prehabilitation before planned liver resection. Br J Surg. 2016;103:504–512. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ferreira V., Lawson C., Carli F., Scheede-Bergdahl C., Chevalier S. Feasibility of a novel mixed-nutrient supplement in a multimodal prehabilitation intervention for lung cancer patients awaiting surgery: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Int J Surg. 2021;93 doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.106079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferreira V., Minnella E.M., Awasthi R., et al. Multimodal prehabilitation for lung cancer surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Thorac Surg. 2021;112:1600–1608. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fulop A., Lakatos L., Susztak N., Szijarto A., Banky B. The effect of trimodal prehabilitation on the physical and psychological health of patients undergoing colorectal surgery: a randomised clinical trial. Anaesthesia. 2021;76:82–90. doi: 10.1111/anae.15215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gillis C., Li C., Lee L., et al. Prehabilitation versus rehabilitation: a randomized control trial in patients undergoing colorectal resection for cancer. Anesthesiology. 2014;121:937–947. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gillis C., Loiselle S.E., Fiore J.F., Jr., et al. Prehabilitation with whey protein supplementation on perioperative functional exercise capacity in patients undergoing colorectal resection for cancer: a pilot double-blinded randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;116:802–812. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gloor S., Misirlic M., Frei-Lanter C., et al. Prehabilitation in patients undergoing colorectal surgery fails to confer reduction in overall morbidity: results of a single-center, blinded, randomized controlled trial. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2022;407:897–907. doi: 10.1007/s00423-022-02449-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Granicher P., Stoggl T., Fucentese S.F., Adelsberger R., Swanenburg J. Preoperative exercise in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Arch Physiother. 2020;10:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s40945-020-00085-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grant L.F., Cooper D.J., Conroy J.L. The HAPI 'Hip Arthroscopy Pre-habilitation Intervention' study: does pre-habilitation affect outcomes in patients undergoing hip arthroscopy for femoro-acetabular impingement? J Hip Preserv Surg. 2017;4:85–92. doi: 10.1093/jhps/hnw046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gravier F.E., Smondack P., Boujibar F., et al. Prehabilitation sessions can be provided more frequently in a shortened regimen with similar or better efficacy in people with non-small cell lung cancer: a randomised trial. J Physiother. 2022;68:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2021.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huang J., Lai Y., Zhou X., et al. Short-term high-intensity rehabilitation in radically treated lung cancer: a three-armed randomized controlled trial. J Thorac Dis. 2017;9:1919–1929. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2017.06.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang S.W., Chen P.H., Chou Y.H. Effects of a preoperative simplified home rehabilitation education program on length of stay of total knee arthroplasty patients. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2012;98:259–264. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Humeidan M.L., Reyes J.C., Mavarez-Martinez A., et al. Effect of cognitive prehabilitation on the incidence of postoperative delirium among older adults undergoing major noncardiac surgery: the Neurobics randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2021;156:148–156. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.4371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jahic D., Omerovic D., Tanovic A.T., Dzankovic F., Campara M.T. The effect of prehabilitation on postoperative outcome in patients following primary total knee arthroplasty. Med Arch. 2018;72:439–443. doi: 10.5455/medarh.2018.72.439-443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jensen B.T., Petersen A.K., Jensen J.B., Laustsen S., Borre M. Efficacy of a multiprofessional rehabilitation programme in radical cystectomy pathways: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Scand J Urol. 2015;49:133–141. doi: 10.3109/21681805.2014.967810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim D.J., Mayo N.E., Carli F., Montgomery D.L., Zavorsky G.S. Responsive measures to prehabilitation in patients undergoing bowel resection surgery. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2009;217:109–115. doi: 10.1620/tjem.217.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim S., Hsu F.C., Groban L., Williamson J., Messier S. A pilot study of aquatic prehabilitation in adults with knee osteoarthritis undergoing total knee arthroplasty – short term outcome. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2021;22:388. doi: 10.1186/s12891-021-04253-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lai Y., Huang J., Yang M., Su J., Liu J., Che G. Seven-day intensive preoperative rehabilitation for elderly patients with lung cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Surg Res. 2017;209:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2016.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liang M.K., Bernardi K., Holihan J.L., et al. Modifying risks in ventral hernia patients with prehabilitation: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2018;268:674–680. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Licker M., Karenovics W., Diaper J., et al. Short-term preoperative high-intensity interval training in patients awaiting lung cancer surgery: a randomized controlled trial. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12:323–333. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.09.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lindback Y., Tropp H., Enthoven P., Abbott A., Oberg B. PREPARE: presurgery physiotherapy for patients with degenerative lumbar spine disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Spine J. 2018;18:1347–1355. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2017.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu Z., Qiu T., Pei L., et al. Two-week multimodal prehabilitation program improves perioperative functional capability in patients undergoing thoracoscopic lobectomy for lung cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Anesth Analg. 2020;131:840–849. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.López-Rodríguez-Arias F., Sánchez-Guillén L., Aranaz-Ostáriz V., et al. Effect of home-based prehabilitation in an enhanced recovery after surgery program for patients undergoing colorectal cancer surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29:7785–7791. doi: 10.1007/s00520-021-06343-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lotzke H., Brisby H., Gutke A., et al. A person-centered prehabilitation program based on cognitive-behavioral physical therapy for patients scheduled for lumbar fusion surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2019;99:1069–1088. doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzz020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Marchand A.-A., Houle M., O’Shaughnessy J., Châtillon C.-É., Cantin V., Descarreaux M. Effectiveness of an exercise-based prehabilitation program for patients awaiting surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis: a randomized clinical trial. Sci Rep. 2021;11 doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-90537-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mat Eil Ismail M.S., Sharifudin M.A., Shokri A.A., Ab Rahman S. Preoperative physiotherapy and short-term functional outcomes of primary total knee arthroplasty. Singapore Med J. 2016;57:138. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2016055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Matassi F., Duerinckx J., Vandenneucker H., Bellemans J. Range of motion after total knee arthroplasty: the effect of a preoperative home exercise program. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22:703–709. doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-2349-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McKay C., Prapavessis H., Doherty T. The effect of a prehabilitation exercise program on quadriceps strength for patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled pilot study. PM R. 2012;4:647–656. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2012.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Minnella E.M., Awasthi R., Bousquet-Dion G., et al. Multimodal prehabilitation to enhance functional capacity following radical cystectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Eur Urol Focus. 2021;7:132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2019.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Minnella E.M., Awasthi R., Loiselle S.E., Agnihotram R.V., Ferri L.E., Carli F. Effect of exercise and nutrition prehabilitation on functional capacity in esophagogastric cancer surgery: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:1081–1089. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Minnella E.M., Ferreira V., Awasthi R., et al. Effect of two different pre-operative exercise training regimens before colorectal surgery on functional capacity: a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2020;37:969–978. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000001215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Morano M.T., Araújo A.S., Nascimento F.B., et al. Preoperative pulmonary rehabilitation versus chest physical therapy in patients undergoing lung cancer resection: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94:53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.08.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nguyen C., Boutron I., Roren A., et al. Effect of prehabilitation before total knee replacement for knee osteoarthritis on functional outcomes: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nielsen P.R., Jorgensen L.D., Dahl B., Pedersen T., Tonnesen H. Prehabilitation and early rehabilitation after spinal surgery: randomized clinical trial. Clin Rehabil. 2010;24:137–148. doi: 10.1177/0269215509347432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Northgraves M.J., Arunachalam L., Madden L.A., et al. Feasibility of a novel exercise prehabilitation programme in patients scheduled for elective colorectal surgery: a feasibility randomised controlled trial. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28:3197–3206. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-05098-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.O'Gara B.P., Mueller A., Gasangwa D.V.I., et al. Prevention of early postoperative decline: a randomized, controlled feasibility trial of perioperative cognitive training. Anesth Analg. 2020;130:586–595. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Onerup A., Andersson J., Angenete E., et al. Effect of short-term homebased pre- and postoperative exercise on recovery after colorectal cancer surgery (PHYSSURG-C): a randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2022;275:448–455. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Peng L.H., Wang W.J., Chen J., Jin J.Y., Min S., Qin P.P. Implementation of the pre-operative rehabilitation recovery protocol and its effect on the quality of recovery after colorectal surgeries. Chin Med J. 2021;134:2865–2873. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000001709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Santa Mina D., Hilton W.J., Matthew A.G., et al. Prehabilitation for radical prostatectomy: a multicentre randomized controlled trial. Surg Oncol. 2018;27:289–298. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2018.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Satoto H.H., Paramitha A., Barata S.H., et al. Effect of preoperative inspiratory muscle training on right ventricular systolic function in patients after heart valve replacement surgery. Bali Med J. 2021;10:340–346. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sawatzky J.A., Kehler D.S., Ready A.E., et al. Prehabilitation program for elective coronary artery bypass graft surgery patients: a pilot randomized controlled study. Clin Rehabil. 2014;28:648–657. doi: 10.1177/0269215513516475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sebio Garcia R., Yanez-Brage M.I., Gimenez Moolhuyzen E., Salorio Riobo M., Lista Paz A., Borro Mate J.M. Preoperative exercise training prevents functional decline after lung resection surgery: a randomized, single-blind controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31:1057–1067. doi: 10.1177/0269215516684179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shaarani S.R., O'Hare C., Quinn A., Moyna N., Moran R., O'Byrne J.M. Effect of prehabilitation on the outcome of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:2117–2127. doi: 10.1177/0363546513493594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Steinmetz C., Bjarnason-Wehrens B., Baumgarten H., Walther T., Mengden T., Walther C. Prehabilitation in patients awaiting elective coronary artery bypass graft surgery - effects on functional capacity and quality of life: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2020;34:1256–1267. doi: 10.1177/0269215520933950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tenconi S., Mainini C., Rapicetta C., et al. Rehabilitation for lung cancer patients undergoing surgery: results of the PUREAIR randomized trial. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2021;57:1002–1011. doi: 10.23736/S1973-9087.21.06789-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Topp R., Swank A.M., Quesada P.M., Nyl J., Malkani A. The effect of prehabilitation exercise on strength and functioning after total knee arthroplasty. PM R. 2009;1:729–735. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Vagvolgyi A., Rozgonyi Z., Kerti M., Agathou G., Vadasz P., Varga J. Effectiveness of pulmonary rehabilitation and correlations in between functional parameters, extent of thoracic surgery and severity of post-operative complications: randomized clinical trial. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10:3519–3531. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.05.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.IJmker-Hemink V.E., Wanten G.J.A., de Nes L.C.F., van den Berg M.G.A. Effect of a preoperative home-delivered, protein-rich meal service to improve protein intake in surgical patients: a randomized controlled trial. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2020;45:479–489. doi: 10.1002/jpen.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Waller E., Rahman S., Sutton P., Allen J., Saxton J., Aziz O. Randomised controlled trial of patients undergoing prehabilitation with wearables versus standard of care before major abdominal cancer surgery (Trial Registration: NCT04047524) Colorectal Dis. 2020;22:7. doi: 10.1007/s00464-021-08365-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wang X., Che G., Liu L. A short-term high-intensive pattern of preoperative rehabilitation better suits surgical lung cancer patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;25 [Google Scholar]

- 90.Woodfield J.C., Clifford K., Wilson G.A., Munro F., Baldi J.C. Short-term high-intensity interval training improves fitness before surgery: a randomized clinical trial. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2022;28:28. doi: 10.1111/sms.14130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yamana I., Takeno S., Hashimoto T., et al. Randomized controlled study to evaluate the efficacy of a preoperative respiratory rehabilitation program to prevent postoperative pulmonary complications after esophagectomy. Dig Surg. 2015;32:331–337. doi: 10.1159/000434758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Furon Y., Dang Van S., Blanchard S., Saulnier P., Baufreton C. Effects of high-intensity inspiratory muscle training on systemic inflammatory response in cardiac surgery-A randomized clinical trial. Physiother Theory Pract. 2024;40:778–788. doi: 10.1080/09593985.2022.2163212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Franz A., Ji S., Bittersohl B., Zilkens C., Behringer M. Impact of a six-week prehabilitation with blood-flow restriction training on pre-and postoperative skeletal muscle mass and strength in patients receiving primary total knee arthroplasty. Front Physiol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2022.881484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Heiman J., Onerup A., Wessman C., Haglind E., Olofsson Bagge R. Recovery after breast cancer surgery following recommended pre and postoperative physical activity:(PhysSURG-B) randomized clinical trial. Br J Surg. 2021;108:32–39. doi: 10.1093/bjs/znaa007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Milios J.E., Ackland T.R., Green D.J. Pelvic floor muscle training in radical prostatectomy: a randomized controlled trial of the impacts on pelvic floor muscle function and urinary incontinence. BMC Urol. 2019;19:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12894-019-0546-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]