Abstract

Background

The World Health Organization's (WHO’s) Health Promoting Schools (HPS) framework is an holistic, settings‐based approach to promoting health and educational attainment in school. The effectiveness of this approach has not been previously rigorously reviewed.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of the Health Promoting Schools (HPS) framework in improving the health and well‐being of students and their academic achievement.

Search methods

We searched the following electronic databases in January 2011 and again in March and April 2013: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Campbell Library, ASSIA, BiblioMap, CAB Abstracts, IBSS, Social Science Citation Index, Sociological Abstracts, TRoPHI, Global Health Database, SIGLE, Australian Education Index, British Education Index, Education Resources Information Centre, Database of Education Research, Dissertation Express, Index to Theses in Great Britain and Ireland, ClinicalTrials.gov, Current controlled trials, and WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform. We also searched relevant websites, handsearched reference lists, and used citation tracking to identify other relevant articles.

Selection criteria

We included cluster‐randomised controlled trials where randomisation took place at the level of school, district or other geographical area. Participants were children and young people aged four to 18 years, attending schools or colleges. In this review, we define HPS interventions as comprising the following three elements: input to the curriculum; changes to the school’s ethos or environment or both; and engagement with families or communities, or both. We compared this intervention against schools that implemented either no intervention or continued with their usual practice, or any programme that included just one or two of the above mentioned HPS elements.

Data collection and analysis

At least two review authors identified relevant trials, extracted data, and assessed risk of bias in the trials. We grouped different types of interventions according to the health topic targeted or the approach used, or both. Where data permitted, we performed random‐effects meta‐analyses to provide a summary of results across studies.

Main results

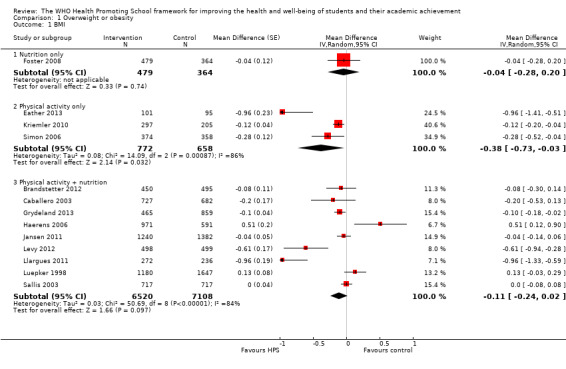

We included 67 eligible cluster trials, randomising 1443 schools or districts. This is made up of 1345 schools and 98 districts. The studies tackled a range of health issues: physical activity (4), nutrition (12), physical activity and nutrition combined (18), bullying (7), tobacco (5), alcohol (2), sexual health (2), violence (2), mental health (2), hand‐washing (2), multiple risk behaviours (7), cycle‐helmet use (1), eating disorders (1), sun protection (1), and oral health (1). The quality of evidence overall was low to moderate as determined by the GRADE approach. 'Risk of bias' assessments identified methodological limitations, including heavy reliance on self‐reported data and high attrition rates for some studies. In addition, there was a lack of long‐term follow‐up data for most studies.

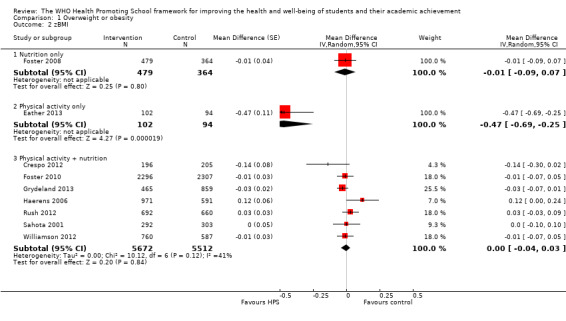

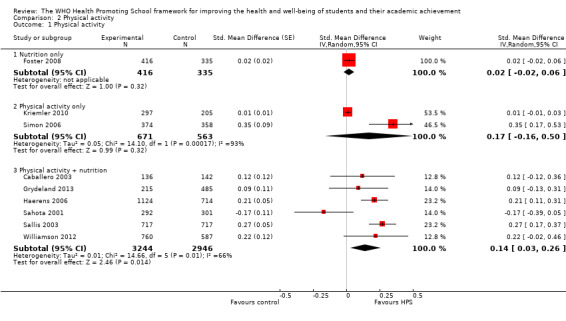

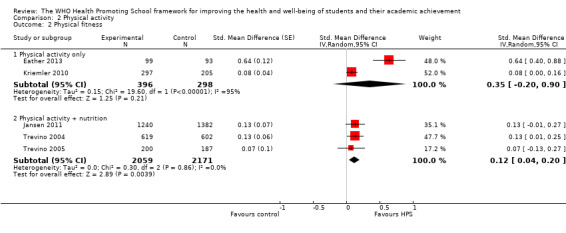

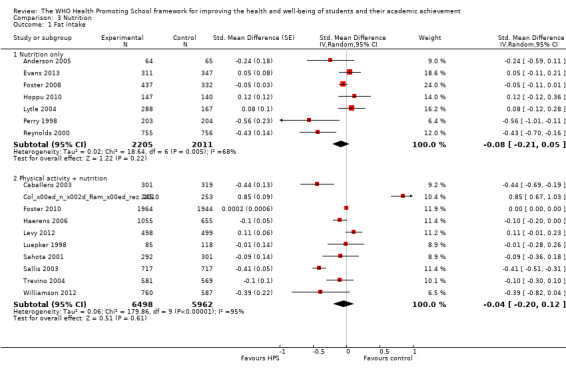

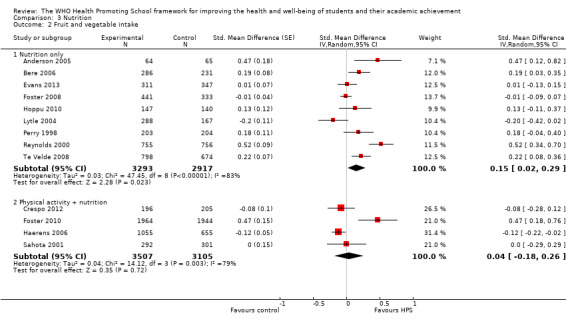

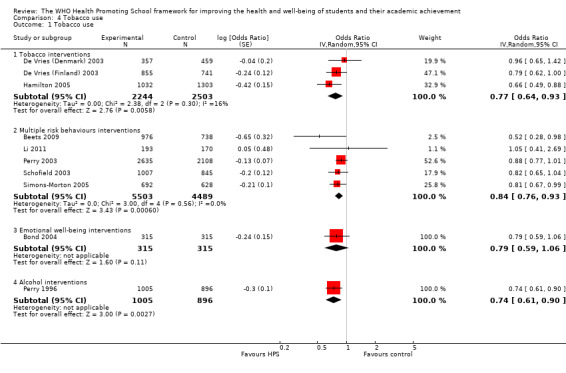

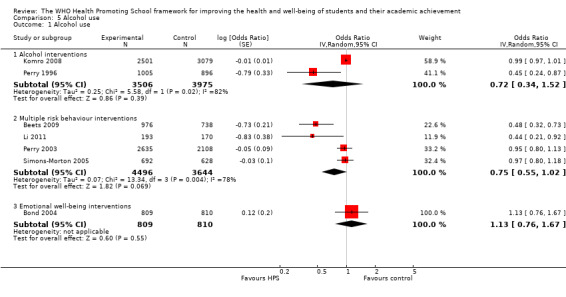

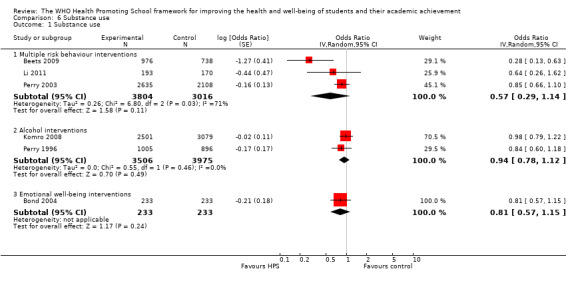

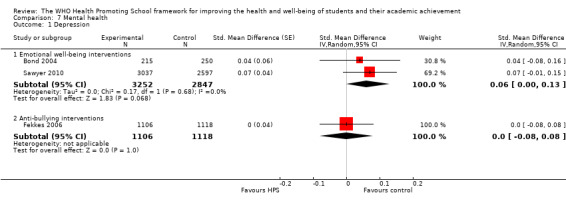

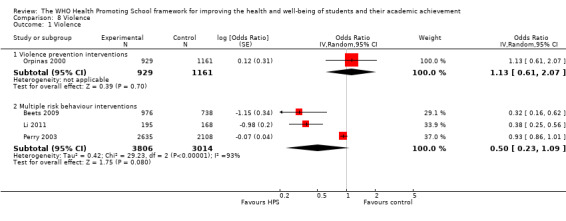

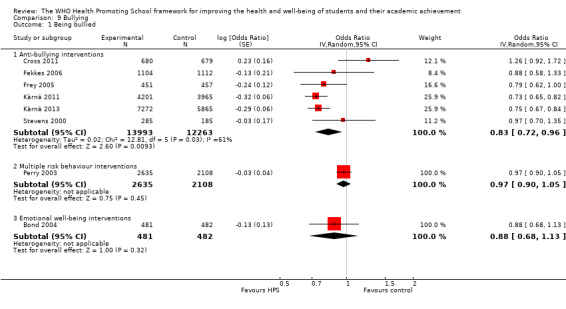

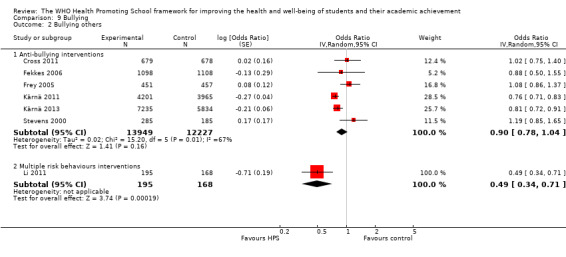

We found positive effects for some interventions for: body mass index (BMI), physical activity, physical fitness, fruit and vegetable intake, tobacco use, and being bullied. Intervention effects were generally small but have the potential to produce public health benefits at the population level. We found little evidence of effectiveness for standardised body mass index (zBMI) and no evidence of effectiveness for fat intake, alcohol use, drug use, mental health, violence and bullying others; however, only a small number of studies focused on these latter outcomes. It was not possible to meta‐analyse data on other health outcomes due to lack of data. Few studies provided details on adverse events or outcomes related to the interventions. In addition, few studies included any academic, attendance or school‐related outcomes. We therefore cannot draw any clear conclusions as to the effectiveness of this approach for improving academic achievement.

Authors' conclusions

The results of this review provide evidence for the effectiveness of some interventions based on the HPS framework for improving certain health outcomes but not others. More well‐designed research is required to establish the effectiveness of this approach for other health topics and academic achievement.

Keywords: Adolescent; Child; Child, Preschool; Humans; Achievement; Health Behavior; School Health Services; Students; World Health Organization; Bullying; Health Promotion; Health Promotion/methods; Mental Health; Motor Activity; Obesity; Obesity/prevention & control; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Reproductive Health; Substance‐Related Disorders; Substance‐Related Disorders/prevention & control; Violence

Plain language summary

The WHO Health Promoting School framework for improving the health and well‐being of students and their academic achievement

Background

Health and education are strongly connected: healthy children achieve better results at school, which in turn are associated with improved health later in life. This relationship between health and education forms the basis of the World Health Organization's (WHO’s) Health Promoting Schools (HPS) framework, an approach to promoting health in schools that addresses the whole school environment. Although the HPS framework is used in many schools, we currently do not know if it is effective. This review aimed to assess whether the HPS framework can improve students’ health and well‐being and their performance at school.

Study characteristics

We searched 20 health, education, and social science databases, as well as trials registries and relevant websites, for cluster‐randomised controlled trials of school‐based interventions aiming to improve the health of young people aged four to 18 years. We only included trials of programmes that addressed all three points in the HPS framework: including health education in the curriculum; changing the school’s social or physical environment, or both; and involving students’ families or the local community, or both.

Key results

We found 67 trials, comprising 1345 schools and 98 districts, that fulfilled our criteria. These focused on a wide range of health topics, including physical activity, nutrition, substance use (tobacco, alcohol, and drugs), bullying, violence, mental health, sexual health, hand‐washing, cycle‐helmet use, sun protection, eating disorders, and oral health. For each study, two review authors independently extracted relevant data and assessed the risk of the study being biased. We grouped together studies according to the health topic(s) they focused on.

We found that interventions using the HPS approach were able to reduce students’ body mass index (BMI), increase physical activity and fitness levels, improve fruit and vegetable consumption, decrease cigarette use, and reduce reports of being bullied. However, we found little evidence of an effect on BMI when age and gender were taken into account (zBMI), and no evidence of effectiveness on fat intake, alcohol and drug use, mental health, violence, and bullying others. We did not have enough data to draw conclusions about the effectiveness of the HPS approach for sexual health, hand‐washing, cycle‐helmet use, eating disorders, sun protection, oral health or academic outcomes. Few studies discussed whether the health promotion activities, or the collection of data relating to these, could have caused any harm to the students involved.

Quality of the evidence

Overall, the quality of evidence was low to moderate. We identified some problems with the way studies were conducted, which may have introduced bias, including many studies relying on students’ accounts of their own behaviours (rather than these being measured objectively) and high numbers of students dropping out of studies. These problems, and the small number of studies included in our analysis, limit our ability to draw clear conclusions about the effectiveness of the HPS framework in general.

Conclusions

Overall, we found some evidence to suggest the HPS approach can produce improvements in certain areas of health, but there are not enough data to draw conclusions about its effectiveness for others. We need more studies to find out if this approach can improve other aspects of health and how students perform at school.

Background

Promoting health in schools

The influence of childhood experiences on health status later in life is well documented (Felitti 1998; Galobardes 2006; Kessler 2010; Poulton 2002; Wadsworth 1997; Wright 2001). There is evidence to suggest that attitudes, beliefs, and behaviours learned during these early years ‐ for example, those relating to smoking, physical activity, and food choices ‐ show strong ‘tracking’ into adulthood (Kelder 1994; Singh 2008; Whitaker 1997). Promoting healthy habits during these early formative years is therefore of key importance.

Recognition of this has led to an interest in using schools as a means of promoting healthy behaviours in children and young people. Children spend a large proportion of their time at school and thus schools have the potential to be a powerful domain of influence on children's health. Additionally, there is a strong link between children’s health status and their capacity to learn (Powney 2000; Singh 2008). Creating positive and healthy school environments, therefore, can have numerous benefits in improving health, well‐being, and academic achievement, and reducing inequities.

Promoting health has long been an important role of schools, but traditionally activities have focused on health education, whereby information about health topics is imparted to students via the formal school curriculum, or on the development of specific skills such as communication skills or refusal techniques (Lynagh 1997). While a few programmes appear to have had some short‐term impact, there is little evidence to demonstrate that such approaches can effect sustainable behavioural change in the long term (Brown 2009; Faggiano 2005; Foxcroft 2011; Waters 2011).

The WHO Health Promoting Schools Framework

In recognition of the limited success of these interventions, a new holistic approach to school health promotion was developed in the late 1980s, influenced and underpinned by the values set out in the World Health Organization's Ottawa Charter (WHO 1986). This charter marked a significant shift in WHO public health policy, from a focus on individual behaviour to recognition of the wider social, political, and environmental influences on health.

The application of these principles to the educational setting led to the idea of the ‘Health Promoting School’ (HPS) whereby health is promoted through the whole school environment and not just through ‘health education’ in the curriculum. Thus, a Health Promoting School aims to:

Promote the adoption of lifestyles conducive to good health

Provide an environment that supports and encourages healthy lifestyles

Enable students and staff to take action for a healthier community and healthier living conditions (Health Education Boards 1996).

No strict definition of a Health Promoting School exists and it has been described in various ways in different documents (Denman 1999; IUHPE 2008; Lister‐Sharp 1999; Lynagh 1997; Nutbeam 1992; Parsons 1996; St Leger 1998; WHO 1997; Young 1989). The International Union for Health Promotion and Education, for example, provide a six‐point definition of Health Promoting Schools (school health policies; physical environment; social environment; individual health skills and action competencies; community links; and health services) (IUHPE 2008). Elsewhere in the literature a simpler, three‐point definition is employed, which subsumes the six points above (Denman 1999; Deschesnes 2003; Lister‐Sharp 1999; Marshall 2000; Mũkoma 2004; Nutbeam 1992; Parsons 1996; Rogers 1998; Young 1989). Additionally, whilst some interventions are explicitly labelled as adopting a HPS approach, others do not use this name but nonetheless are implicitly based upon HPS principles. In the United States, for example, this type of approach is commonly known as 'Comprehensive School Health Education'.

For the purposes of this review, we use the broad, three‐point definition of the HPS model in our selection criteria to ensure the review is inclusive of the somewhat varied and earlier approaches to HPS. According to this model, Health Promoting Schools require change in three areas of school life:

1. Formal health curriculum

Health education topics are given specific time allocation within the formal school curriculum in order to help students develop the knowledge, attitudes, and skills needed for healthy choices;

2. Ethos and environment of the school

Health and well‐being of students and staff are promoted through the ‘hidden’ or ‘informal’ curriculum, which encompasses the values and attitudes promoted within the school, and the physical environment and setting of the school; and

3. Engagement with families or communities or both

Schools seek to engage with families, outside agencies, and the wider community in recognition of the importance of these other spheres of influence on children’s attitudes and behaviours.

How Health Promoting Schools might influence health

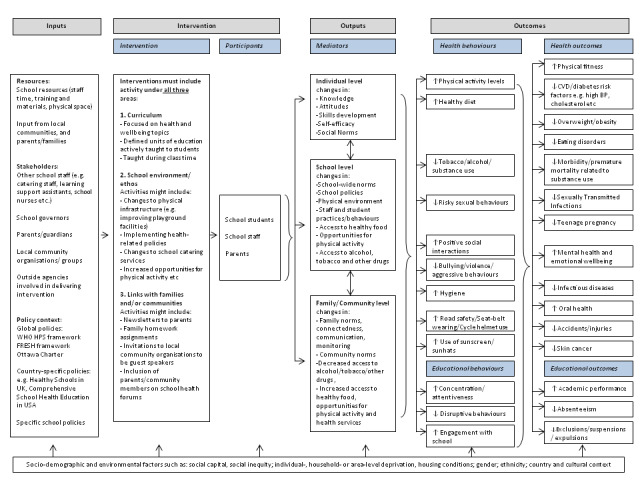

We developed a logic model to capture the ways in which the Health Promoting Schools framework might influence health and educational outcomes (Figure 1). We identified important policy documents relevant to the intervention (HPS framework, Ottawa Charter) to inform the logic model, outlining key inputs and mechanisms of action, and providing examples of hypothesised changes in health behaviours or outcomes or both. The review authors refined and agreed the logic model.

1.

Logic model

The Health Promoting Schools framework is based on an eco‐holistic model, recognising the physical, social, mental, emotional, and environmental dimensions of health and well‐being (Parsons 1996). The three domains described above recognise different levels of influence upon health ‐ moving from the individual, to the school environment, to the wider community context ‐ and emphasise the need to act upon all three levels in order to successfully influence health.

At the individual level, health education, through the formal curriculum, remains an important part of the HPS approach. Recognising that "to lead a healthy life is, to some degree, a matter of making the right choices" (Young 1989), students need accurate information about health issues in order to make informed choices. Thus, health education can increase knowledge and help establish positive attitudes and health behaviours. Developing the necessary skills in order to be able to act upon such information is also key; programmes may therefore emphasise communication skills, refusal techniques, and ways to promote self confidence and self efficacy. Ultimately improvements in knowledge, attitudes, and skills can enhance psychosocial health and help establish new positive social norms within the student population regarding health behaviours.

What children learn about health within the formal curriculum must be endorsed and promoted within the wider school environment to have credibility. The ‘hidden’ or ‘informal’ curriculum promoted within the school can help create a safe and supportive atmosphere that is conducive to healthy behaviours. Schools might, for example, provide secure cycle racks to promote active transport to school; implement a ‘no smoking’ policy; increase provision of healthy foods through the school catering service; develop peer mentoring approaches to tackle bullying; or increase student participation and engagement within schools through school councils.

Finally, it is important to recognise that the school environment is only one of the many domains of influence on children’s health. Families and the wider community in which children live also have an enormous impact on children’s health. It is necessary, therefore, to engage with the community beyond the school. To achieve this, schools should take into account the views and opinions of the families and communities they serve, and encourage their support and participation in health‐promoting activities. Health messages promoted at school need to be reinforced within the family and wider community settings if they are to have a significant impact on physical and social exposures and children’s behaviours.

Why it is important to do this review

A systematic review conducted in 1999 examined the impact of the HPS approach on a variety of student health outcomes (Lister‐Sharp 1999). However, the conclusions of this review were limited by the small number of studies available and weaknesses in their study designs. Results from these studies varied, but improvements in dietary intake, measures of physical fitness, self esteem, and rates of bullying were observed, and the authors concluded that there was "limited but promising" data to suggest that the HPS approach could have a positive impact on health (Lister‐Sharp 1999).

In the years since the Lister‐Sharp 1999 review was completed, interest in the HPS framework has continued to grow, with this approach being used in many countries in the absence of clear evidence of its effectiveness or potential harm. Focusing on studies with rigorous evaluation designs, we sought to re‐assess the current evidence of effectiveness of the Health Promoting Schools framework in order to inform future policy and research recommendations.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of the Health Promoting Schools (HPS) framework in improving the health and well‐being of students and their academic achievement.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Cluster‐randomised controlled trials (RCTs), where clusters were at the level of school, district or other geographical area. As the HPS framework is an holistic, whole‐school approach, we excluded any studies where clusters were at the classroom level. We also excluded feasibility and pilot RCTs and any trials where only one school was allocated to intervention and control groups.

Public health interventions are often highly complex and context‐dependent (Rychetnik 2002), and as such may require different types of evaluative approaches. Many evaluations of the HPS framework have not been conducted using RCT methodology and offer important insights into both process and implementation. While we acknowledge the value of this body of evidence, we focus this review on cluster‐randomised trials as the most reliable form of evidence for evaluating the relative effects of interventions (Green 2011). For an overview of other evidence on the HPS framework (including non‐randomised study designs), see IUHPE 2010, Stewart‐Brown 2006 and Lister‐Sharp 1999.

Types of participants

Children and young people aged four to 18 years attending schools or colleges (including special schools). We excluded studies which covered both pre‐school and school‐aged students.

We made a post hoc change to the types of participants focused on in this review. We had originally intended to examine the impact of the Health Promoting Schools framework on staff as well as student health (Langford 2011). However, the definition of HPS interventions (as described in the published literature, referenced above) requires there to be curricular input as an essential criterion. This therefore eliminated any studies that focus on staff health, as they would not contain any curricular element. Consequently, this review is focused exclusively on students’ health and well‐being.

Types of interventions

Interventions (of any duration) based upon the HPS framework that demonstrate active engagement of the school in health promotion activities ineach of the following areas.

School curriculum;

Ethos or environment of the school or both;

Engagement with families or communities or both.

We present more specific inclusion criteria for these three categories in Appendix 1. Interventions did not have to explicitly state that they were based upon the HPS framework to be eligible for inclusion. If they addressed the three domains of the intervention we included them. It was not an eligibility requirement that studies reported academic outcomes.

Control schools were schools that implemented either no intervention or continued with their usual practice, or schools that implemented an alternative intervention that included only one or two of the HPS criteria.

Types of outcome measures

The HPS framework is a highly complex, multi‐dimensional intervention, which presented particular methodological challenges for this systematic review. The intervention seeks to improve ‘health’ in general, and does not restrict itself to specific health issues; the focus of each intervention is determined by the schools and researchers according to need. Thus, while individual studies may focus on a specific health topic (for example, obesity or substance misuse), the range of topics included in the review is very broad. Consequently this review defined its primary outcome ‐ health ‐ to reflect the broad focus of the HPS framework (improving health in its widest sense) as well as educational outcomes.

Primary outcomes

Health

For each health topic, we identified both positive and potentially adverse outcomes (where reported). We categorised health outcomes into the following topic areas:

Obesity or overweight or body size: body mass index or standardised body mass index (BMI or zBMI), height‐for‐age, weight‐for‐age, and weight‐for‐height z‐scores, skin‐fold thickness measures, waist circumference

Physical activity or sedentary behaviours: accelerometry, multi‐stage fitness tests (for example, shuttle runs, step tests), self‐reported levels of physical activity or sedentary behaviours

Nutrition: self‐reported food intake (particularly focusing on consumption of fruits and vegetables, water, high fat or sugar foods), indicators of specific nutritional deficiencies (for example, iron, iodine, and vitamin A deficiencies)

Tobacco use: salivary cotinine, carbon monoxide levels, self‐reported use of cigarettes or other tobacco products

Alcohol use: self‐reported use of alcohol

Other drug use: self‐reported use of other drugs (legal or illegal)

Sexual health: incidence of sexually transmitted infections, pregnancy or abortion, self‐reported use of condoms or other contraception, abstinence or delaying of sexual intercourse

Mental health and emotional well‐being: validated scales of well‐being or quality of life or both, incidence of self harm or suicide, use of validated scales such as Rosenberg’s self esteem scale, Beck Depression Inventory, Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

Violence: self‐reported violence (for example, carried weapon, got into a fight)

Bullying: self‐reported incidence of being bullied or bullying others

Infectious diseases: incidence of diseases such as diarrhoea, cold or influenza, skin disease, worms, head lice; observation or self report of hand‐washing with soap after visiting toilet or before handling food

Safety and accident prevention: incidence of traffic accidents or other accidents or injuries in school or at home; observation or self report of cycle‐helmet use

Body image or eating disorders: student (or teacher or parent) reports of disordered eating habits, body size acceptance, self esteem

Skin or sun safety: observation or self report of sunscreen, behaviours to reduce exposure to the sun (for example, wearing hat, seeking shade, covering up)

Oral health: decayed, missing or filled teeth index; self‐reported dental hygiene behaviours such as regular tooth brushing, dental check‐ups; self‐reported consumption of sugary snacks or drinks

Within each health topic, we measured outcomes using:

a. Objective measures of health or health behaviours, for example, validated methods or techniques such as BMI, accelerometry.

b. Subjective measures of health or health behaviours, for example, observation or self reports of behaviour or subjective ratings of health.

c. Measures of knowledge or attitudes or self efficacy (for example, knowledge of causes or consequences of specific health issues; attitudes towards behaviours that are known risk or protective factors for health; perceptions of one's ability to perform a certain behaviour).

Where studies presented an outcome measured in more than one way (for example, smoking in last seven days and smoking in last 30 days), we chose the category that indicated the highest frequency of the (harmful) behaviour within each respective study, assuming that this would be of the greatest public health importance.

Academic outcomes

Academic outcomes focused on: student‐standardised academic test scores, IQ tests or other validated scales; school academic performance.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes focused on:

School attendance outcomes.

Non‐academic school outcomes: for example, ratings of school climate, attachment to school, satisfaction with school.

Process outcomes: fidelity, acceptability, reach, and intensity of the intervention delivery.

Curriculum outcomes: evidence of health education topics within the formal school curriculum.

School environment outcomes: evidence of changes to the school’s social or physical environment or both. Examples might include: implementing no‐smoking policies, improving school catering services, developing peer mentoring programmes to tackle bullying, playground redesign.

Engagement with families or communities or both: participation of parents or families in relevant school‐based activities; evidence of engagement with local community organisations.

Timing of outcome assessment

The primary end point for outcome data extraction was immediately postintervention (or the closest time point to this, up to a maximum of six months postintervention). We then categorised follow‐up data after the end of the intervention (if presented) as being either short‐ (12 months or less), medium‐ (12 to 24 months) or long‐term (24 months or more).

Economic data

Where provided, we extracted data on the costs and cost effectiveness of studies.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases in January 2011. We conducted updated searches in 2013, beginning on 15 March 2013 and completed on 22 April 2013. We did not apply any date or language restrictions to our searches. Studies were not excluded on the basis of publication status. Abstracts, conference proceedings, and other 'grey' literature were included if they met the inclusion criteria.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) 2013, Issue 3, part of The Cochrane Library.

Ovid MEDLINE, 1950 to 15 March 2013.

EMBASE,1980 to 2013 week 16.

ASSIA ‐ Applied Social Science Index and Abstracts, 1987 to 2011.

Australian Education Index, 1979 to current.

BEI – British Education Index, 1975 to current.

BiblioMap – Database of Health Promotion Research (eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/).

CAB Abstracts, 1973 to 2013 week 11.

Campbell Library of Systematic Reviews (campbellcollaboration.org/lib/).

CINAHL ‐ Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, 1982 to current.

Clinical Trials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov/).

Current Controlled Trials (controlled‐trials.com/mrct/)

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects 2013, Issue 1, part of The Cochrane Library.

Database of Education Research (eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/).

Dissertation Express (dissexpress.umi.com/dxweb/search.html).

ERIC – Education Resources Information Centre, 1966 to current.

Global Health Database.

IBSS – International Bibliography of Social Sciences, 1950 to current.

International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (who.int/ictrp/en/).

Index to Theses in Great Britain and Ireland.

PsycINFO, 1806 to 2013 week 10.

SIGLE – System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe (now known as OpenGrey) (www.opengrey.eu/).

Social Science Citation Index, 1956 to current.

Sociological Abstracts, 1952 to current.

TRoPHI ‐ Trials Register of Promoting Health Interventions (eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/).

The search strategies and search dates for these databases are shown in Appendix 2.

Searching other resources

We handsearched the reference lists of relevant articles and used citation tracking to identify and obtain relevant articles. In addition, we searched the following websites for relevant publications, including grey literature:

Australian Health Promoting Schools Association (www.ahpsa.org.au).

Barnardo’s (www.ahpsa.org.au).

Center for Disease Control and Prevention (www.cdc.gov).

Communities and Schools Promoting Health (www.safehealthyschools.org).

International Union for Health Promotion and Education (www.iuhpe.org).

International School Health Network (www.internationalschoolhealth.org).

National Centre for Social Research (www.natcen.ac.uk/).

National Children’s Bureau (www.ncb.org.uk).

National College for School Leadership (www.nationalcollege.org.uk).

National Foundation for Education Research (www.nfer.ac.uk).

National Healthy Schools Programme (home.healthyschools.gov.uk).

National Youth Agency (www.nya.org.uk).

Schools for Health in Europe (www.schoolsforhealth.eu).

School Health Education Unit (sheu.org.uk).

UNAIDS (www.unaids.org/).

UNFPA (www.unfpa.org).

UNICEF (www.unfpa.org).

World Bank (www.worldbank.org).

World Health Organization (www.who.int).

Several of the databases and the majority of websites that we searched in January 2011 yielded no or very few studies eligible for inclusion. The few eligible studies identified via these databases or websites were also identified through searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE, and PsycINFO. We therefore chose to exclude the following from our updated search in 2013: Global Health Database, Index to Theses in Great Britain and Ireland, Dissertation Express, SIGLE, Database of Educational Research, Bibliomap, and all websites. In addition, we no longer had access to ASSIA and therefore could not update our search of this database.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The initial search strategy produced over 35,000 reports, after removing duplicate records. A further 12,750 were retrieved in March and April 2013 after deduplication. One review author (RL) conducted an initial title screen to remove those which were obviously not pertinent to the review. For quality assurance purposes, a second review author (RC) double‐screened a random selection of 10% of these titles, yielding a kappa score of 0.88, reflecting excellent agreement. Thereafter, two authors independently screened all abstracts and full‐texts to determine eligibility. We resolved any disagreements regarding eligibility through discussion and, when necessary, in consultation with a third review author (usually RC).

Data extraction and management

For each study, two review authors (RL, and shared between LG, CB, SM, DM, and KK) independently completed data extraction forms created for the purposes of this review.

We extracted data pertaining to: basic study details (participant characteristics, study location, sample size, rates of attrition); study design and duration; intervention characteristics (including health focus, theoretical framework, content and activities, and details of any intervention offered to the control group); process evaluation of the intervention (including fidelity, acceptability, reach, intensity, and context of intervention); outcome measures postintervention and subsequent follow‐up; and costs of intervention. We used the PROGRESS PLUS check list to collect data relevant for equity (Kavanagh 2008).

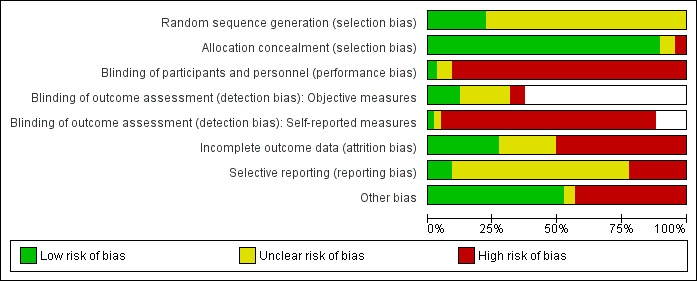

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed risk of bias within each included study using the tool outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). For each study two review authors (RL and DP) independently judged the likelihood of bias in the following domains: selection (sequence generation and allocation concealment), blinding (performance and detection bias), attrition (incomplete outcome data), reporting (selective outcome reporting), and any other potential sources of bias. For each domain, we rated studies as being at ‘high’, ‘low’ or ‘unclear’ risk of bias. We resolved any disagreements on categorisation through discussion, referring to a third review author when necessary (HJ).

Selection bias included an assessment of both adequate sequence generation and allocation concealment. We assessed sequence generation to be at low risk of bias when studies clearly specified a method for generating a truly random sequence. As all studies included in this review were cluster‐RCTs, we assessed studies as being at low risk of bias for allocation concealment if allocation was performed for all clusters at the start of the study.

The blinding domain covers both performance and detection bias. It was rarely (if ever) possible to blind students or staff to the fact that they were taking part in an intervention; we therefore assessed studies as being at high risk of performance bias unless authors explicitly stated that students were blind to group allocation. We assessed studies as being at low risk of detection bias if they clearly described the blinding of outcome assessors. If outcomes were assessed by self report, we rated the studies as being at high risk of bias where students were unlikely to have been adequately blinded.

In order to assess attrition bias we considered rates of attrition both overall and between groups, and considered whether this was likely to be related to intervention outcomes.

We assessed studies as being at low risk of reporting bias when a published protocol or study design paper was available and all prespecified outcomes were presented in the report. Where no protocol was available, we assessed studies as being at unclear risk of bias. If an outcome was specified in the study protocol but was not reported in any subsequent outcome papers, we assessed the study as being at high risk of bias.

We used the ‘other bias’ domain to note any additional concerns relating to study quality that did not fit into any of the previous five domains. For example, in this domain we included concerns about recruitment bias, baseline imbalances between groups, or selective reporting of subgroup analyses.

We assessed the overall quality of the body of evidence for each outcome using the GRADE approach (Schünemann 2011). Using this method, randomised trial evidence can be downgraded from high to moderate, low or very low quality on the basis of five factors: limitations in design or implementation (often indicative of high risk of bias); indirectness of evidence; unexplained heterogeneity; imprecision of results; or high probability of publication bias.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous (binary) data, we used odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to summarise results within each study. We summarised continuous outcomes using a mean difference (MD) with standard error. We extracted mean differences (adjusted for baseline) from an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model when these were presented. When ANCOVA results were not available we instead extracted or calculated mean differences based on final value measurements. We calculated a pooled standard deviation (SD) from intervention and control SDs at follow‐up.

Where studies used different scales to measure what we considered to represent the same underlying outcome, we first standardised results to a uniform scale by calculating standardised mean differences (SMDs). This involves dividing the estimated mean difference by the standard deviation of outcome measurements. Regardless of the method used to estimate the mean difference (ANCOVA or final values), standardisation was always performed using the standard deviation of outcome measurements at follow‐up. This was to avoid the problem of computed SMDs not being combinable across studies using different approaches to estimate the mean difference.

Where some studies reported an outcome as dichotomous and others provided a continuous measure, we converted results to the most commonly reported scale, assuming the underlying continuous measurement had an approximate logistic distribution, using methods described in Borenstein 2009 (Chapter seven).

Where data were presented separately by gender or age group, we combined these data using methods described in Borenstein 2009 (Chapter 23).

Unit of analysis issues

Interventions employing a 'whole school' approach require randomisation at the group (rather than individual) level. Where analysis took place at the school level (for example, school academic performance) no special statistical analysis is required. However, where studies reported results at the individual level, we determined whether or not the authors had accounted for the effect of clustering using appropriate statistical techniques such as multi‐level modelling. Where this had not been done (or it was not clear if it had been done), we attempted to contact the study authors to ask for the intra‐cluster correlation coefficient (ICC) and mean cluster size. This information allowed us to make an adjustment for clustering to their results before inclusion in the meta‐analyses (Higgins 2011b). If these data were not available, we examined the ICCs in similar studies. To be conservative, we selected the largest of these to adjust results prior to inclusion in the meta‐analyses.

When performing a meta‐analysis of SMDs from cluster‐RCTs, we had to decide whether to use the standard deviation of outcome measurements within clusters or the overall (‘total’) standard deviation across all individuals in a study (Grieve 2012; White 2005). The latter will be larger, since it also incorporates between‐cluster variability (specifically, Variance [total] = Variance [within clusters] + Variance [between clusters], White 2005), although the difference between the two measures is lessened if ICCs are small. Since within‐cluster standard deviations are rarely reported, we used the total standard deviation.

It is useful to have estimates of ICCs for different outcomes within different population groups to inform future research. Additional Table 1 presents the ICCs that were either reported in the included studies, or obtained via correspondence with study authors.

1. Intra‐cluster correlation coefficients.

| Study | Country | Age | Variable | Reported intra‐cluster correlation coefficient (ICC) | Published or correspondence |

| Bond 2004 | Australia | Grade 8 | Various ‐ including substance use, depressive symptoms and school engagement. | Not specifically reported for each outcome: ranged from 0.01 ‐ 0.06 | Published |

| Brandstetter 2012 | Germany | Grade 2 | BMI | 0.028 (NB this is the ICC for classroom, rather than school, clustering) | Correspondence |

| Crespo 2012 | USA | K‐Grade 2 | BMI | Not specifically reported for each outcome: ranged from 0 ‐ 0.019 | Published |

| Physical activity | |||||

| Eather 2013 | Australia | Grades 5 ‐ 6 | zBMI | 0.02 | Correspondence |

| BMI | 0.02 | ||||

| Eddy 2003 | USA | Grade 5 | Various substance use outcomes | Not specifically reported: ranged from 0 ‐ 0.01 | Published |

| Hoffman 2010 | USA | K‐Grade 1 | Portions of fruit and vegetables | 0.32 | Published |

| Hoppu 2010 | Finland | Grade 8 | Fat intake | 0.004 | Correspondence |

| Fruit consumption | 0.012 | ||||

| Vegetable consumption | 0.006 | ||||

| Jansen 2011 | Netherlands | Grade 3 ‐ 8 | BMI | < 0.01 | Published |

| Waist circumference | 0.014 | ||||

| Shuttle run | 0.166 | ||||

| Kriemler 2010 | Switzerland | Grade 1 and 5 | BMI | 0.01 | Published |

| MVPA (accelerometry) | 0.08 | ||||

| Shuttle run | 0.06 | ||||

| Llargues 2011 | Spain | 5 ‐ 6 year‐olds | BMI | 0.094 | Correspondence |

| Lytle 2004 | USA | Grades 7 ‐ 8 | Servings of fruits and vegetables | 0.0007 | Published |

| % energy as fat | 0.0217 | ||||

| % energy as saturated fat | 0.0134 | ||||

| Kärnä 2011 | Finland | Grades 4 ‐ 6 | Self‐reported victimisation | 0.02 | Published |

| Self‐reported bullying | 0.02 | ||||

| Well‐being at school | 0.03 | ||||

| Kärnä 2013 | Finland | Grades 2 ‐ 3 and 8 ‐ 9 | Self‐reported victimisation | Grade 2 ‐ 3: 0.05 Grade 8 ‐ 9: 0.03 |

Published |

| Self‐reported bullying | Grade 2 ‐ 3: 0.03 Grade 8 ‐ 9: 0.02 |

||||

| Perry 1996 | USA | Grades 6 ‐ 8 | Various – unclear if just referring to alcohol use or includes other substance use outcomes | Not specifically reported: ranged from 0.002 ‐ 0.03, with a median value of .015 | Published |

| Perry 1998 | USA | Grades 4 ‐ 5 | Fruit and vegetable consumption | 0.03 | Published |

| Sawyer 2010 | Australia | Grade 8 | Depression (CES‐D scores) | 0.02 | Published |

| Williamson 2012 | USA | Grades 4 ‐ 6 | % body fat | Not specifically reported: ranged from 0.0005 ‐ 0.026 | Published |

| zBMI | |||||

| Food intake | Not specifically reported: ranged from 0.15 ‐ 0.38 | ||||

| Physical activity | 0.05 | ||||

| Sedentary behaviour | 0.03 | ||||

| Wolfe 2009 | Canada | Grade 9 | Physical dating violence | 0.02 | Published |

Dealing with missing data

In the event of missing or unclear data within published studies, we attempted to contact the study authors. Where multi‐level model data were presented but authors did not provide standard errors or specific P values (and we were unable to obtain these from authors), we used final value outcome measurements and adjusted for clustering as described above (three cases). To calculate standardised mean differences, we needed to divide the effect estimate by the standard deviation of the sample. Where this was not available, we imputed the standard deviation from baseline or from another similar study (Higgins 2011b).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity among studies initially by visual inspection of forest plots. We performed Chi² tests to assess evidence of variation in effect estimates beyond that expected by chance. However, since this test has low power to detect heterogeneity when studies have small sample sizes or are few in number, we calculated I², which is an estimate of the percentage of variation due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error or chance, where a value greater than 50% indicates moderate to substantial heterogeneity (Deeks 2011). For meta‐analyses where I² was greater than 50%, we performed subgroup analyses to explore this heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

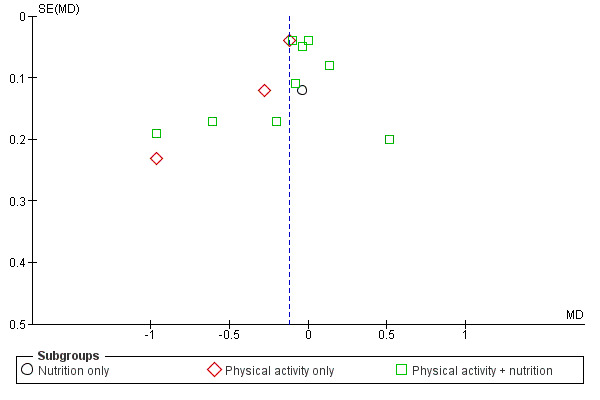

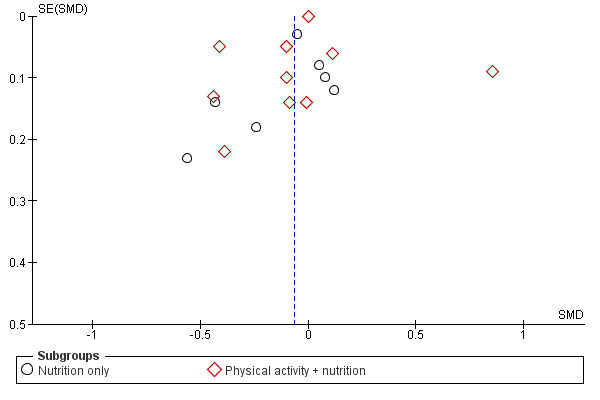

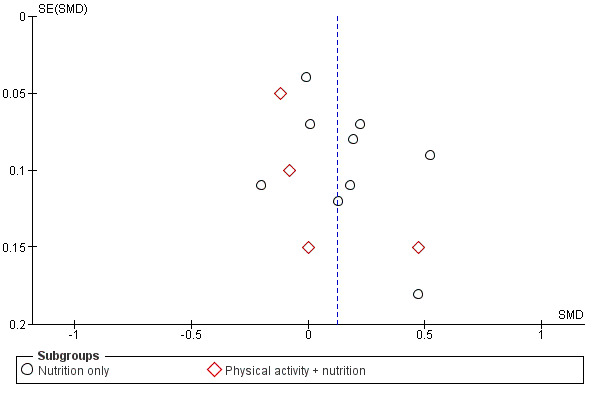

Where possible, we drew funnel plots to assess the presence of possible publication bias or small study effects (Sterne 2011).

Data synthesis

Quantitative data

The HPS framework is a flexible intervention, which can be used to target a wide range of health behaviours. We identified a number of different types of HPS interventions based broadly on the health topic(s) that the studies sought to tackle. However, we also differentiated between the different approaches that were taken to tackling specific health issues. For example, we distinguished between studies that sought to tackle overweight or obesity by targeting physical activity, those that targeted nutrition, and those that targeted both physical activity and nutrition. Similarly, we also identified what we have termed Multiple Risk Behaviour interventions (Hurrelman 2006), which sought to target multiple health outcomes with one intervention. We mapped the review outcomes to which these intervention types contributed data in Additional Table 2 and they are described in detail in Appendix 3.

2. Mapping of outcomes.

| Study ID | Intervention Name | Intervention outcomes | |||||||||||||||

| Overweight/ obesity | Physical activity | Nutrition | Tobacco | Alcohol | Drugs | Sexual health | Mental health | Violence | Bullying | Infectious disease | Safety/ accidents | Body image | Sun safety | Oral health | Aacdemic/ attendance/ school | ||

| Nutrition interventions | |||||||||||||||||

| Anderson 2005 | ‐ | X (MA) | |||||||||||||||

| Bere 2006 | Fruits and Vegetables Make the Mark | X (MA) | |||||||||||||||

| Evans 2013 | Project Tomato | X (MA) | |||||||||||||||

| Foster 2008 | School Nutrition Policy Initiative | X (MA) | X (MA) | X (MA) | |||||||||||||

| Hoffman 2010 | Athletes in Service, Fruit and Vegetable Promotion Program | X | |||||||||||||||

| Hoppu 2010 | ‐ | X (MA) | |||||||||||||||

| Lytle 2004 | TEENS | X (MA) | |||||||||||||||

| Nicklas 1998 | Gimme 5 | X | |||||||||||||||

| Perry 1998 | 5 A DAY Power Plus | X (MA) | |||||||||||||||

| Radcliffe 2005 | ‐ | X | |||||||||||||||

| Reynolds 2000 | High 5 | X (MA) | |||||||||||||||

| Te Velde 2008 | Pro Children Study | X (MA) | |||||||||||||||

| Physical activity interventions | |||||||||||||||||

| Eather 2013 | Fit 4 Fun | X (MA) | X (MA) | ||||||||||||||

| Kriemler 2010 | KISS | X (MA) | X (MA) | ||||||||||||||

| Simon 2006 | ICAPS | X (MA) | X (MA) | ||||||||||||||

| Wen 2008 | ‐ | X | |||||||||||||||

| Physical activity + nutrition interventions | |||||||||||||||||

| Arbeit 1992 | Heart Smart | X | |||||||||||||||

| Brandstetter 2012 | URMEL ICE | X (MA) | |||||||||||||||

| Caballero 2003 | Pathways | X (MA) | X (MA) | X (MA) | |||||||||||||

| Colín‐Ramírez 2010 | RESCATE | X | X (MA) | ||||||||||||||

| Crespo 2012 | Aventuras para Niños | X (MA) | X (MA) | ||||||||||||||

| Foster 2010 | HEALTHY | X (MA) | X (MA) | ||||||||||||||

| Grydeland 2013 | Health in Adolescents (HEIA) | X (MA) | X (MA) | ||||||||||||||

| Haerens 2006 | ‐ | X (MA) | X (MA) | X (MA) | |||||||||||||

| Jansen 2011 | Lekker Fit | X (MA) | X (MA) | ||||||||||||||

| Llargues 2011 | AVall | X (MA) | |||||||||||||||

| Luepker 1998 | CATCH | X (MA) | X | X (MA) | X | ||||||||||||

| Rush 2012 | Project Energize | X (MA) | |||||||||||||||

| Sahota 2001 | APPLES | X (MA) | X (MA) | X (MA) | X | ||||||||||||

| Sallis 2003 | M‐SPAN | X (MA) | X (MA) | X (MA) | |||||||||||||

| Levy 2012 | Nutrición en Movimiento | X (MA) | X | X (MA) | |||||||||||||

| Trevino 2004 | Bienestar (1) | X (MA) | |||||||||||||||

| Trevino 2005 | Bienestar (2) | X | X (MA) | X (MA) | |||||||||||||

| Williamson 2012 | Louisiana (LA) HEALTH | X (MA) | X (MA) | X (MA) | |||||||||||||

| Tobacco interventions | |||||||||||||||||

| De Vries (Denmark) 2003 | ESFA (Denmark) | X (MA) | |||||||||||||||

| De Vries (Finland) 2003 | ESFA (Finland) | X (MA) | |||||||||||||||

| Hamilton 2005 | ‐ | X (MA) | |||||||||||||||

| Perry 2009 | Project MYTRI | X | |||||||||||||||

| Wen 2010 | ‐ | X | |||||||||||||||

| Alcohol interventions | |||||||||||||||||

| Komro 2008 | Project Northland (Chicago) | X (MA) | X (MA) | ||||||||||||||

| Perry 1996 | Project Northland (Minnesota) | X (MA) | X (MA) | X (MA) | |||||||||||||

| Multiple risk behaviour interventions | |||||||||||||||||

| Beets 2009 | Positive Action (Hawai’i) | X (MA) | X (MA) | X (MA) | X | X (MA) | X | ||||||||||

| Eddy 2003 | LIFT | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Flay 2004 | Aban Aya | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Li 2011 | Positive Action (Chicago) | X (MA) | X (MA) | X (MA) | X (MA) | X (MA) | X | ||||||||||

| Perry 2003 | DARE Plus | X (MA) | X (MA) | X (MA) | X (MA) | X (MA) | |||||||||||

| Schofield 2003 | Hunter Regions Health Promoting Schools Program | X (MA) | |||||||||||||||

| Simons‐Morton 2005 | Going Places | X (MA) | X (MA) | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Sexual health interventions | |||||||||||||||||

| Basen‐Engquist 2001 | Safer choices | X | |||||||||||||||

| Ross 2007 | MEMA Kwa Vijana | X | |||||||||||||||

| Mental health and emotional well‐being interventions | |||||||||||||||||

| Bond 2004 | Gatehouse | X (MA) | X (MA) | X (MA) | X (MA) | X (MA) | X | ||||||||||

| Sawyer 2010 | beyondblue | X (MA) | X | ||||||||||||||

| Violence interventions | |||||||||||||||||

| Orpinas 2000 | Students for Peace | X (MA) | |||||||||||||||

| Wolfe 2009 | Fourth R | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Ant‐bullying interventions | |||||||||||||||||

| Cross 2011 | Friendly Schools | X (MA) | |||||||||||||||

| Cross 2012 | Friendly Schools, Friendly Families | X | |||||||||||||||

| Fekkes 2006 | ‐ | X (MA) | X (MA) | X | |||||||||||||

| Frey 2005 | Steps to Respect | X (MA) | |||||||||||||||

| Kärnä 2011 | KiVa (1) | X (MA) | X | ||||||||||||||

| Kärnä 2013 | KiVa (2) | X (MA) | |||||||||||||||

| Stevens 2000 | ‐ | X (MA) | |||||||||||||||

| Hand‐washing interventions | |||||||||||||||||

| Bowen 2007 | ‐ | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Talaat 2011 | ‐ | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Miscellaneous interventions | |||||||||||||||||

| Hall 2004 | School Bicycle Safety Project / The Helmet Files | X | |||||||||||||||

| McVey 2004 | Healthy Schools ‐ Healthy Kids | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Olson 2007 | SunSafe | X | |||||||||||||||

| Tai 2009 | ‐ | X | |||||||||||||||

MA: included in meta analysis for this outcome

Our meta‐analyses present summaries of the results of these different intervention types in separate subgroups; we felt it was inappropriate to pool data overall, given the heterogeneity of approaches used to target different health outcomes. At times, subgroups may include only one study; we have, however, included these data in the forest plots so that comparisons may be made ‘by eye’ with the other intervention approaches taken.

As these complex interventions differed in terms of participants, focus, implementation, and setting, we expected the true effect of the interventions to vary between studies. We therefore performed a random‐effects meta‐analysis for each outcome on all studies reporting that outcome. As a sensitivity analysis, we also calculated fixed‐effect summary estimates. We compared the point estimates from fixed‐effect meta‐analysis to those from random‐effects meta‐analysis as a check for the influence of small study effects, as recommended in Higgins 2011b.

We present data not included in meta‐analyses in Additional Table 3. We were unable to synthesise these data in the meta‐analysis for one or more of the following reasons: we considered outcome data too different to be combined with other studies; the intervention was compared against an alternative intervention rather than standard practice or no intervention; or they were not one of the main outcomes on which this review focused.

3. Outcomes not included in meta‐analyses.

| Study ID | Name | Type | Outcome(s) | Authors’ conclusions |

| 1. Obesity or overweight or body size | ||||

| Brandstetter 2012 | URMEL‐ICE | Physical activity + nutrition | Skinfold thickness (tricep and subscapular), waist circumference | Intervention students had lower measures for waist circumference (‐0.64, 95% CI ‐1.25 to ‐0.02) and subscapular skinfold thickness (‐0.85, 95% CI ‐1.59 to ‐0.12). However, after adjusting for the time‐lag between baseline and follow‐up, this difference was no longer apparent. No effect was seen for tricep skinfold thickness. |

| Crespo 2012 | Aventuras para Niños | Physical activity + nutrition | zBMI | Postintervention follow‐up: Data at the end of the intervention and at 1 and 2‐years postintervention. No impact on zBMI at any time point.No difference between control and intervention groups for % body fat. Adjusted difference = 0.18; 95% CI ‐0.45 to 0.81, P value = 0.56. |

| Grydeland 2013 | Health in Adolescents (HEIA) | Physical activity + nutrition | Waist circumference, waist‐to‐hip ratio | No effect seen for waist circumference or waist‐to‐hip ratio for the total sample. |

| Kriemler 2010 | KISS | Physical activity | Skinfolds thickness, waist circumference | Children in intervention group showed smaller increases in the sum of 4 skinfold z‐score units (‐0.12, 95% CI ‐0.21 to ‐0.03, P value = 0.009). No effect was seen for waist circumference. |

| Luepker 1998 | CATCH | Physical activity + nutrition | Tricep and subscapular skinfold | No difference between intervention and control group for tricep skin folds (difference = 0.14 mm, 95% CI ‐0.24 to 0.52, P value = 0.47), or subscapular skinfolds (difference = 0.13 mm; 95% CI ‐0.29 to 0.54, P value = 0.553) |

| Simon 2006 | ICAPS | Physical activity | % body fat, Fat mass index, Fat‐free mass index | Among students who were not overweight at baseline, intervention students had lower fat mass index (‐0.2, 95% CI ‐0.39 to ‐0.01, P < 0.05). There was no difference for % body fat or fat‐free mass index. No differences were seen for any of these outcomes between the 2 groups for students who were initially overweight at baseline. Postintervention follow‐up: 2 years postintervention ‐ intervention students maintained lower age ‐ and gender‐adjusted BMI (0.37 kg/m², P value = 0.02) and waist circumference (1.6 cm, P < 0.01) than control counterparts. |

| Trevino 2004 | Bienestar (2) | Physical activity + nutrition | % body fat | No difference between control and intervention groups for % body fat. Adjusted difference = 0.18 (95% CI ‐0.45 to 0.81, P value = 0.56). |

| Williamson 2012 | LA Health | Physical activity + nutrition | % body fat | No difference between control and intervention (PP + PS group). |

| 2. Physical activity | ||||

| Arbeit 1992 | HEARTSMART | Physical activity + nutrition | 1 mile run or walk test | 5th grade boys’ 1 mile run or walk times decreased by 1.3 minutes in intervention group, but increased by 0.8 minutes in the control group (P < 0.01). |

| Colín‐Ramírez 2010 | RESCATE | Physical activity + nutrition | % children engaging in moderate and moderate‐to‐vigorous physical activity and TV or computer time. | A greater % of children in the intervention group reported being moderately physically active more than 3 days a week, compared to control children (40% I, 8% C, P value for difference between groups not given). No difference between groups for moderate‐to‐vigorous physical activity or TV or computer time. |

| Eather 2013 | Fit 4 Fun | Physical activity | Muscular fitness and flexibility | Positive treatment effects observed in intervention children for flexibility (sit and reach, adjusted mean difference, 1.52 cm, P value = 0.003), physical activity (adjusted mean difference, 3253 steps/day, P < 0.001) and 1 measure of muscular fitness (7‐stage sit‐up, adjusted mean difference, 0.62 stages, P value = 0.003). No effect was seen for 3 other measures of muscular fitness (basketball throw, push‐ups and standing jump). |

| Levy 2012 | Nutricion en Movimiento | Physical activity + nutrition | % children active | No difference between control and intervention group. |

| Llargues 2011 | Avall | Physical activity + nutrition | TV screen time (hours). Proportion of students taking exercise | No difference between control and intervention group for TV screen time. Intervention students were more likely to report exercising (15.7% versus 10.9%, P value = 0.036). |

| Luepker 1998 | CATCH | Physical activity + nutrition | PE lesson length. Energy expenditure and energy expenditure rate (during PE lesson) | No difference between intervention and control schools for PE lesson length. However, intervention students had greater rates of energy expenditure (0.20 kJ/kg, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.27) and a higher energy expenditure ratio (0.35 kJ/kg per hour, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.45) in PE lessons than controls. |

| Sallis 2003 | M‐SPAN | Physical activity + nutrition | Physical activity at school (observations) | There was a greater rate of increase in physical activity at school over time in intervention schools, compared to controls (d = 0.93). Subgroup analyses reveal the effect was significant only for boy (d = 1.1). |

| Simon 2006 | ICAPS | Physical activity | TV or video time, active commuting to and from school | Children in intervention group watched less television (‐15.71 minutes per day, 95% CI ‐28.49 to ‐2.92, P value = 0.02). No difference between groups for active commuting to and from schools (1.03 mins/day, 95% CI ‐2.16 to 4.22, P value = 0.53). Postintervention follow‐up: 2 years postintervention‐ intervention students spent less time watching television (29 mins/day, P < 0.01) and had higher active transport levels (+5 mins/days, P < 0.01). |

| Wen 2008 | ‐ | Physical activity | Self reports on travel to and from school | No difference between intervention and control groups in number of children walking to and from school. |

| Williamson 2012 | LA Health | Physical activity + nutrition | Sedentary behaviour | No difference between control and intervention (PP + PS group). |

| 3. Nutrition | ||||

| Crespo 2012 | Aventuras Para Niños | Physical activity + nutrition | Consumption of sugary drinks and snacks | No effect seen for consumption of sugary drinks. There was an initial reduction in the number of snacks consumed by intervention group (‐0.38, SE 0.17). Postintervention follow‐up: This effect on snack consumption was not sustained at follow‐up. |

| Hoffman 2010 | Athletes in Service, Fruit and Vegetable Promotion Program | Nutrition | Fruit and vegetable intake | Children in intervention consumed a greater amount of fruit (34 g, 95% CI 30 to 39) than control students (23 g, 95% CI 18 to 28) (P < 0.001). |

| Llargues 2011 | AVall | Physical activity + nutrition | Consumption of fruit and vegetable, and sugary snacks or drinks | No difference between groups for proportion of children eating fruit or vegetables daily. However, there was an increase in the daily intake of > 1 piece of fruit per day (P value = 0.005). No difference between groups for consumption of sugary snacks/drinks. |

| Nicklas 1998 | GIMME FIVE | Nutrition | Fruit and vegetable intake, knowledge and confidence to eat more fruit and vegetables | Intervention students had higher fruit and vegetable consumption than controls for the first 2 years of the intervention (P < 0.05), but this effect was lost by the final year of the study. Intervention students had higher knowledge scores than controls in the final 2 years of intervention (P < 0.05 for both). No group effect was seen for student confidence in eating more fruit and vegetables. |

| Radcliffe 2005 | ‐ | Nutrition | % skipping breakfast. Healthy breakfast choices | No difference between groups for % of children skipping breakfast. No difference between groups for reported intake of any energy‐dense, micronutrient‐poor (EDMP) food or beverage breakfast choice. |

| Reynolds 2000 | High 5 | Nutrition | Fruit and vegetable intake | Postintervention follow‐up: The increased consumption of fruit and vegetables in intervention students observed at the end of the intervention was maintained 12 months later (3.2 versus 2.21 servings for intervention and control groups, respectively, P < 0.0001). |

| Sallis 2003 | M‐SPAN | Physical activity + nutrition | School‐level fat intake levels (observations) | No effect was seen on school levels of fat intake. |

| 4. Tobacco use | ||||

| Eddy 2003 | LIFT | Multiple risk behaviours | Tobacco initiation | Postintervention follow‐up: Intervention was associated with a reduced risk (10%, β = ‐0.1, P < 0.01) in tobacco use initiation. After controlling for hypothesized mediators, the intervention was associated with less likelihood of tobacco use initiation (LR Chi² = 6.69, P < 0.05). |

| Luepker 1998 | CATCH | Physical activity + nutrition | Current smoker | No difference between intervention and control students. |

| Perry 2009 | Project Mytri | Tobacco | Smoking in last 30 days, use of chewing tobacco and bidi. | The rates of smoking cigarettes, bidi smoking and any tobacco use increased over time in the control group; the rate of any tobacco use and bidi smoking decreased in the intervention group. Overall, tobacco use increased by 68% in the control group and decreased by 17% in the intervention group. |

| Wen 2010 | ‐ | Tobacco | Ever and regular smoking | No effect was seen for students ever trying smoking (OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.44 to 1.16, P value = 0.178) but intervention students were less likely than controls to become regular smoker (OR 0.38, 95% CI 0.16 to 0.93, P value = 0.035). |

| 5. Alcohol use | ||||

| Eddy 2003 | LIFT | Multiple risk behaviours | Alcohol use | Postintervention follow‐up: Intervention was associated with a reduced risk (7%, β = ‐0.07, P < 0.05) in alcohol use initiation. |

| 6. Drug use | ||||

| Eddy 2003 | LIFT | Multiple risk behaviours | Illicit drug use | Postintervention follow‐up: No difference between groups for illicit drug use. The intervention had a marginal effect on initiation (9%, β = ‐0.09, P < 0.10). |

| Flay 2004 | Aban Aya | Multiple risk behaviours | Substance use | Boys in intervention group were less likely than controls to report substance use (effect size 0.45, P value = 0.05, CIs not given) but this effect was of borderline significance. No effect was seen for girls. |

| Wolfe 2009 | Fourth R | Violence prevention | Problem substance use | No effect seen on problem substance use (Adj. OR 1.11, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.44 P value = 0.43). |

| 7. Sexual health | ||||

| Basen‐Engquist 2001 | Safer Choices | Sexual health | Delayed sexual initiation, condom use, number of partners | No difference between groups for incidence of sexual initiation (OR 0.83, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.27, P value = 0.39). Intervention students were less likely to have sex without a condom (effect size 0.63, P value = 0.05, CIs not given) and fewer partners with whom they had sex without a condom (effect size 0.73, P value = 0.02, CIs not given). |

| Beets 2009 | Positive Action (Hawai’i) | Multiple risk behaviours | Sexual activity | Intervention students were less likely to have had sex than control student (OR 0.18, 90% CI 0.09 to 0.36). |

| Flay 2004 | Aban Aya | Multiple risk behaviours | Recent sexual intercourse, Condom use. | Boys in the intervention group were less likely than controls to have had recent sexual intercourse (effect size 0.65, P value = 0.2) and more likely to use a condom (effect size 0.66, P value = 0.045, CIs not given). No effect was seen for girls. |

| Ross 2007 | MEMA Kwa Vijana | Sexual health | HIV incidence. Prevalence of other STIs. Incidence of pregnancy. Condom use. Number of partners | No difference between groups for HIV incidence or prevalence of syphilis, Chlamydia and Trichomonas. Prevalence of gonorrhoea was higher in intervention women than control (Adj. RR 1.93, 95% CI 1.01 to 3.71). There was no difference between groups in the number of pregnancies. Intervention men and women were more likely to have first used a condom during the follow‐up period than controls (men: Adj. RR 1.41, 95% CI 1.15 to 1.73; women: Adj. RR 1.30, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.63). Intervention men (but not women) were more likely than controls to have used a condom at last sex (Adj. RR 1.47, 95% CI 1.12 to 1.93) and less likely to have had >1 partner in past 12 months (Adj. RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.49 to 0.95). Postintervention follow‐up: ≈6 years postintervention ‐ no difference between groups for HIV prevalence or any other STIs, number of pregnancies and condom use. There was an increase in men reporting < 4 sexual partners (Adj. prevalence rate 0.87, 95% CI 0.78 to 0.97). |

| Wolfe 2009 | Fourth R | Dating violence prevention | Condom use | No difference seen between groups for condom use (Adj. OR 1.04 95% CI 0.51 to 2.2, P value = 0.91). |

| 8. Mental health or emotional well‐being | ||||

| Fekkes 2006 | ‐ | Anti‐bullying | Depression | No difference observed between groups for depression. Postintervention follow‐up: 1 year postintervention, no difference observed between groups for depression. |

| Sawyer 2010 | beyondblue | Emotional well‐being | Depression | Postintervention follow‐up: No difference between groups for depression. |

| 9. Violence | ||||

| Eddy 2003 | LIFT | Multiple risk behaviours | Physical aggression in playground | Postintervention follow‐up: Intervention students showed significant reductions in physical aggression in the playground, compared to controls (‐0.11, P < 0.01). |

| Flay 2004 | ABAN AYA | Multiple risk behaviours | Violence | Boys in intervention group were less likely than controls to report violent behaviour (effect size 0.41, P value = 0.02, CIs not given). No effect was seen for girls. |

| Simons‐Morton 2005 | Going Places | Multiple risk behaviours | Antisocial behaviour (including violence and other 'social' problems) | No effect seen for antisocial behaviour. |

| Wolfe 2009 | Fourth R | Dating violence prevention | Physical dating violence, peer violence | Postintervention follow‐up: (2½ years after start of intervention) No difference was seen for physical dating violence using unadjusted ORs (1.42, 95% CI, 0.87 to 2.33, P value = 0.15). When analyses were adjusted for baseline behaviour, stratifying variables and gender, intervention students were less likely to report physical dating violence (Adj. OR 2.42, 95% CI 1.00 to 6.02, P value = 0.05) but this effect was of borderline significance. No effect was seen for physical peer violence (OR 1.09, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.59). |

| 10. Bullying | ||||

| Cross 2012 | Friendly Schools, Friendly Families | Anti‐bullying | Being bullied, bullying others, told if saw bullying | At the end of intervention, Grade 4 students in the low‐intensity group (control) were more likely to report having been bullied than students in the high‐intensity group (OR 1.39, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.91) but no effect was seen for Grade 6 students. No effect was seen for ‘bullying others’ in either Grade cohort at the end of intervention. Grade 6 students were more likely to tell someone if they saw bullying (OR 1.78, 95% CI 1.21 to 2.62). Postintervention follow‐up: 1 year postintervention (collected for Grade 4 students only) low‐intensity group (control) students were more likely to report having been bullied (OR 1.64, 95% CI 1.06 to 2.53) or bullying others (OR 1.74, 95% CI 1.09 to 2.78). |

| Fekkes 2006 | ‐ | Anti‐bullying | Being bullied, active bullying | Postintervention follow‐up: 1 year postintervention, there were no differences between intervention and control students for being bullied (rate ratio 1.14, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.59) or active bullying (rate ratio 0.7, 95% CI 0.43 to 1.29). |

| 11. Infectious disease prevention: Hand‐washing | ||||

| Bowen 2007 | ‐ | Hygiene | Illness incidence | No difference seen between groups for overall illness incidence. However, intervention schools reported a 42% decrease in student absences.Intervention students were less likely than controls to be absent due to headaches (0.54 versus 0.73 episodes per 100 student weeks, P value = 0.04) and stomach aches (0 versus 0.3 episodes per 100 student weeks, P value = 0.03). |

| Talaat 2011 | ‐ | Hygiene | Absence caused by illness (influenza‐like infections, diarrhoea, conjunctivitis) | Overall, absences caused by illness were reduced by 21% in intervention schools (5.7 versus 7.2 median episodes). Absences due to influence‐like illness were reduced by 40% (0.3 versus 0.5 median episodes), diarrhoea by 33% (0.2 versus 0.3 median episodes) and conjunctivitis by 67% (0.1 versus 0.3 median episodes). P < 0.0001 for all. |

| 12. Safety or accident prevention | ||||

| Hall 2004 | School Bicycle Safety Project (Helmet Files) | Safety | Observed and self‐reported helmet use, helmet worn correctly | No effect seen on observed helmet use. Of those who reported not always wearing a helmet at baseline, intervention students were more likely to report always wearing a helmet at post‐test 1 (OR 1.76, 95% CI 1.09 to 2.85) but this effect disappeared at post‐test 2. |

| 13. Body image or eating disorders | ||||

| McVey 2004 | Healthy School – Healthy Kids | Body image | Student and teachers' body satisfaction, internalisation of media ideals, body size acceptance, weight‐based teasing, disordered eating, weight loss, muscle gaining behaviours | The intervention reported a positive effect in the "internalization of media ideals" for intervention students (F [2, 596] = 3.30, P value = 0.03) and a decrease in disordered eating (only measured in girls; F [2, 276) = 2.73, P value = 0.04). No effect was seen on body satisfaction, body size acceptance or perceptions of weight‐based teasing. Compared to controls, fewer intervention students were trying to lose weight at the end of the intervention (Chi² = 4.29, P value = 0.03) but this effect was lost at 6‐month follow‐up. No effect was seen at any point for muscle‐gaining behaviour. No effect was seen for teachers on any outcome. |

| 14. Sun safety | ||||

| Olson 2007 | Sunsafe in Middle Schools | Sun protection | % Body Surface Area covered up in sun, sunscreen application | No effect was seen on the % of body surface area covered up on observed adolescents or reported sunscreen use at first follow‐up. However, by the end of the 2nd year, students from intervention areas were likely to be more covered up than control participants (66.1% versus 56.8% body surface area covered, P < 0.01). They were also more likely to report using sunscreen at this time than control participants (47% versus 13.8%, P < 0.001). |

| 15. Oral health | ||||

| Tai 2009 | ‐ | Oral health | Net caries increment; Restoration, sealant, and decay score; Oral health care habits reported by mothers. | No difference between groups for number of decayed, missing or filled teeth (DMFT), although there was a slight reduction in number of decayed, missing or filled surfaces (DMFS) in intervention children (0.22 versus 0.35, P value = 0.013). Intervention students had a greater mean decrease in plaque index (0.32 versus 0.21, P value = 0.013) and sulcus bleeding index (0.14 versus 0.08, P value = 0.005). Intervention children were more likely than controls to have received restorants (10.3% versus 6.2%, P value = 0.006), have sealants placed (17.5% versus 4.1%, P < 0.001) and less likely to have untreated decay (7.6% versus 20.5%, P < 0.001). Mothers of children in intervention group were more likely to report their children brushed her or his teeth, had had a dental visit within the past year and used fluoride toothpaste (P < 0.001 for all). |

| 16. Academic, attendance, and school‐related outcomes | ||||

| Beets 2009 | Positive Action (Hawai'i ) | Multiple risk behaviours | Test scores for reading and maths, absenteeism, suspensions, retentions in grade, school climate variables | Intervention schools had higher maths and reading scores than control schools (Hawai'i Content and Performance Standards, P < 0.05 for both), lower absenteeism (P < 0.001) and fewer suspensions (P < 0.001). No effect seen for retentions in grade. The effects indicate a 2% advantage per year in the intervention group compared to the control group. Student, teacher and parent School Quality Composite scores were all higher in intervention schools compared to control (P value = 0.015, 0.006, 0.007, respectively). |

| Bond 2004 | Gatehouse Project | Emotional well‐being | Low school attachment | Unadjusted ORs revealed no effect seen on low school attachment. However, at final follow‐up, adjusted ORs suggest an improvement in school attachment in intervention students (Adj. OR 1.33, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.75). |

| Bowen 2007 | ‐ | Hygiene | Attendance | Intervention schools (expanded group) experienced 42% fewer absence episodes (P value = 0.03) and 54% fewer days of absence (P value = 0.03) than control schools. |

| Fekkes 2006 | ‐ | Anti‐bullying | School satisfaction variables | No effect seen for general satisfaction with school life; satisfaction with contact with other pupils; or satisfaction with contact with teachers. |

| Kärnä 2011 | KIVA (1) | Anti‐bullying | Well‐being at school | Intervention students reported higher levels of well‐being at school (0.096, P value = 0.011) compared to the control students. |

| Li 2011 | Positive Action (Chicago) | Multiple risk behaviours | Standardised test scores. Student and teacher reports of academic performance, motivation and disaffection. Absenteeism. | There was a significant decrease in student disaffection with learning in the intervention group compared to those in the control schools. No effect seen on teachers' ratings of students' academic performance but a positive effect on their rating of academic motivation was found. Lower rates of absenteeism found in intervention than in control schools (β= ‐0.16, one‐tailed P value = 0.015). No evidence of a programme effect on standardised test scores for reading and maths. |

| McVey 2004 | Healthy School, Healthy Kids | Body image | Teachers' perceptions of school's social, behavioural and nutrition or physical climate | No effect on teachers' perceptions of school climate. |

| Sahota 2001 | APPLES | Physical activity + nutrition | Self‐perceived scholastic competence | No effect on self‐perceived scholastic competence. |

| Sawyer 2010 | beyondblue | Emotional well‐being | Student and teacher ratings of school climate | No effect found for student rating of school climate. Teacher ratings significantly differed between intervention and control schools over time (β = 0.60, SE = 0.29, P value < 0.05). On average, school climate in intervention schools improved over time, while in control schools it declined. |

| Simons‐Morton 2005 | Going Places | Multiple risk behaviours | Students’ perceptions of school climate | No effect seen on students’ perceptions of school climate. |

| Talaat 2011 | ‐ | Hygiene | Attendance | Overall, absences caused by illness were reduced by 21% in intervention schools (5.7 versus 7.2 median episodes). |

CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; RR: risk ratio; SE: standard error; STI: sexually transmitted infection

Qualitative data

Few qualitative data were reported for any of the included studies outside of process evaluations. The exceptions to this were qualitative data collected during formative development of interventions for the studies conducted by Perry 2009 and Te Velde 2008. Given the paucity of qualitative data, and the differing populations, contexts, and focus of the interventions, we were unable to synthesise these data.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We conducted prespecified subgroup analyses concerning intervention duration and participants’ age to explore heterogeneity between studies where I² was greater than 50%. We formally tested for differences between subgroups using meta‐regression. We classified studies as either of short (12 months or less) or long (greater than 12 months) duration. We also broadly categorised studies into those that target ‘younger’ students (12 years of age and under) and those that target ‘older’ students (over 12 years of age). Where overlap between these groupings occurred, we grouped studies according to the predominant age group. For example, a study targeting grades five to seven (10 to 13 years) would be categorised in the ‘younger’ age group.

Sensitivity analysis

Where data permitted, we undertook sensitivity analyses to explore the robustness of our findings. We assessed the impact of risk of bias in studies by restricting analyses to: (a) studies deemed to be at low risk of selection bias (associated with sequence generation or allocation concealment); (b) studies deemed to be at low risk of performance bias (associated with issues of blinding); and (c) studies deemed to be at low risk of attrition bias (associated with completeness of data). We performed additional sensitivity analyses to examine the impact of methodological choices, including: the use of standard deviations imputed from another study where original standard deviations were not available; combining accelerometry and self‐reported physical activity levels; and the choice of ‘fruit’ versus ‘vegetable’ intake where these data were presented separately.

Results

Description of studies

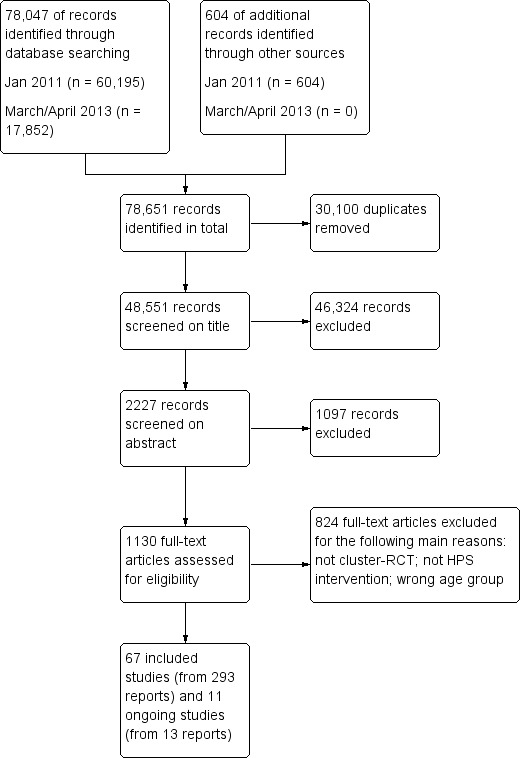

Figure 2 shows how references identified through searches were processed for this review. Our searches yielded 48,551 records after removal of duplicates. Of these, 46,324 were excluded on title, with a further 1097 excluded on abstract screening. We reviewed 1130 full‐text articles for eligibility. Sixty‐seven studies (from 293 reports) met the eligibility criteria for inclusion in the review.

2.

Study flow diagram

Excluded studies

We identified 43 studies that initially appeared to be of relevance to this review but that we subsequently excluded for a variety of reasons, as documented in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. These were studies that: were not randomised or were randomised at classroom level; were pilot or feasibility studies; did not fulfil the criteria for a HPS intervention; included the wrong age‐group; targeted specific ‘at risk’ groups; or involved only two schools (one intervention, one control).

Ongoing studies

We found 11 ongoing studies that are potentially eligible for this review. These are detailed in the Characteristics of ongoing studies. Nine of these studies focus on physical activity or nutrition or both. The remaining two studies are Multiple Risk Behaviour interventions focusing on tobacco, alcohol, and drug use. In future updates of this review, we will contact authors of these studies to confirm eligibility and obtain data for inclusion in the review.

Included studies