Highlights

-

•

A majority of participants held at least a slight belief in vaccine misinformation.

-

•

Positive attitude towards vaccination was linked with disbelief in vaccine conspiracy.

-

•

Endorsing vaccine misinformation was linked with negative attitude to vaccination.

Keywords: COVID-19 vaccination, Vaccine hesitancy, Attitudes, Misinformation, Vaccine conspiracy, Middle East

Abstract

Background

Vaccine hesitancy is a major barrier to infectious disease control. Previous studies showed high rates of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the Middle East. The current study aimed to investigate the attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination and COVID-19 vaccine uptake among adult population in Iraq.

Methods

This self-administered survey-based study was conducted in August–September 2022. The survey instrument assessed participants’ demographics, attitudes to COVID-19 vaccination, beliefs in COVID-19 misinformation, vaccine conspiracy beliefs, and sources of information regarding the vaccine.

Results

The study sample comprised a total of 2544 individuals, with the majority reporting the uptake of at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccination (n = 2226, 87.5 %). Positive attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination were expressed by the majority of participants (n = 1966, 77.3 %), while neutral and negative attitudes were expressed by 345 (13.6 %) and 233 (9.2 %) participants, respectively. Factors associated with positive attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination in multivariate analysis included disbelief in COVID-19 misinformation and disagreement with vaccine conspiracies. Higher COVID-19 vaccine uptake was significantly associated with previous history of COVID-19 infection, higher income, residence outside the Capital, disbelief in COVID-19 misinformation, disagreement with vaccine conspiracies, and reliance on reputable information sources.

Conclusion

COVID-19 vaccine coverage was high among the participants, with a majority having positive attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination. Disbelief in COVID-19 misinformation and disagreement with vaccine conspiracies were correlated with positive vaccine attitudes and higher vaccine uptake. These insights can inform targeted interventions to enhance vaccination campaigns.

1. Introduction

Vaccination represents a great achievement of modern science, with remarkable success in controlling the infectious diseases’ morbidity and mortality (Greenwood, 2014, Rodrigues and Plotkin, 2020, Toor et al., 2021). The success that accompanied the advent of several effective and safe vaccines is manifested in eradication of smallpox, and control of measles and poliomyelitis (Kayser and Ramzan, 2021).

Despite the role of vaccination as a central measure in infectious disease prevention, vaccine hesitancy emerged as a threatening challenge undermining the success of vaccination (Larson et al., 2022). Vaccine hesitancy, defined as the reluctance or rejection of vaccines despite their availability, has become a top threatening global health concern (MacDonald, 2015, Peretti-Watel et al., 2015, Galagali et al., 2022). The issue of vaccine hesitancy emerged long before the emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and the subsequent coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic (World Health Organization (WHO), 2023, Poland and Jacobson, 2001, Ramsay and White, 1998).

Previous studies indicated the wide range of factors linked with vaccination hesitancy, which is a place-, time-, and context-specific phenomenon (MacDonald, 2015, Larson et al., 2014, Schmid et al., 2017, Dubé et al., 2014). Nevertheless, the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the issue of vaccine hesitancy (Wiysonge et al., 2022, Sallam, 2021). Unsubstantiated conspiracy theories, myths, and mis-/dis-information surrounding the virus, preventive measures, and COVID-19 vaccines fueled the phenomenon of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, which was reported in various regions worldwide (Sallam, 2021, Sallam et al., 2022, Ullah et al., 2021). Thus, effective control of COVID-19 relies not only on the availability of effective and safe vaccines, but extends to involve positive attitudes and behaviors towards vaccination (Greyling and Rossouw, 2022).

The development and distribution of vaccines emerged as the promising measure to mitigate the negative impact of this unprecedented pandemic (Kashte et al., 2021, Clemente-Suárez et al., 2021). However, the success of COVID-19 vaccination campaigns extended beyond the issues of COVID-19 vaccine efficacy and safety, since the attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination played a major role in its uptake (Motta et al., 2021).

The infiltration of conspiracy beliefs and misinformation regarding various infectious diseases and vaccines —including COVID-19— has recently been notable in Arab countries (Sallam et al., 2022, Abdaljaleel et al., 2023, Al-Rawi et al., 2022). This included unsubstantiated claims which lacked credible scientific evidence. Examples include the idea that SARS-CoV-2 is a man-made virus, the claim that COVID-19 vaccination aimed to implant microchips for surveillance, and the misconception of vaccine-associated infertility (Sallam et al., 2022, Sallam et al., 2020, Sallam et al., 2021). The association between misinformation and adverse health behaviors has been documented in various settings including the recurring pattern of association between vaccine hesitancy and endorsement of conspiracy beliefs (Sallam et al., 2021, Oliver and Wood, 2014, Regazzi et al., 2023).

Iraq, a Middle Eastern country, has a diverse population of over 41 million in 2021, and the country serves as a distinctive case study with a versatile society (Commons, 2022). As of 18 October 2023, Iraq reported 2,465,545 cumulative COVID-19 cases and 25,375 cumulative deaths (WHO Health Emergency Dashboard, 2024). COVID-19 vaccination in Iraq started on 2 March 2021, with 19,600,00 vaccine doses administered, benefiting 11,332,925 individuals with at least one dose and 7,944,775 individuals with a complete primary vaccination series as of 26 November 2023 (WHO Health Emergency Dashboard, 2024). Four vaccine types —Pfizer/BioNTech, Oxford/AstraZeneca, Sinopharm, and Sputnik V— received approval for use in Iraq (VIPER Group COVID19 Vaccine Tracker Team, 2023). Several early studies from Iraq showed varying attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination and its associated determinants; nevertheless, the majority of these studies did not address the role of misinformation and conspiracies on COVID-19 vaccine uptake (Ghazi et al., 2021, Abdulah, 2021, Alatrany et al., 2023, Tahir et al., 2022, Shareef et al., 2022, Al-Qerem et al., 2022, Darweesh et al., 2022, Luma et al., 2022).

Therefore, the objectives of the current study included investigating possible factors associated with higher COVID-19 vaccine uptake and positive attitudes towards vaccination among adult Iraqi population. Specifically, we aimed to assess the role of vaccine conspiracies and COVID-19 misinformation in shaping vaccination attitudes and behaviors.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

This cross-sectional design study utilized a self-administered online questionnaire to collect data. Inclusion criteria included: being an Iraqi citizen, possessing proficiency in Arabic language, and age of 18-year or older.

Survey distribution took place during 5 August 2022–14 September 2022. The questionnaire was hosted in Google Forms in Arabic. Chain-referral sampling was used for survey distribution starting with the contacts of the authors from Iraq (N.K. and M.A.) using e-mails, the direct messaging application WhatsApp, and social media platforms (Facebook and Twitter). Additionally, the participants were asked to share the survey with their contacts. The survey was anonymous, and no incentives were offered for participation. For those who consented to participate, response to all items was mandatory to eliminate item non-response bias.

The minimum sample size was estimated at 2401 participants. Calculation of the minimum sample size was done using Epitools—Epidemiological Calculators, using the following assumptions: an estimated prevalence of 50 %, the desired precision of estimate at 2 %, and the Iraqi population size of about 41,179,351 people in 2021 (Commons, 2022, Epitools, 2022).

2.2. Survey instrument

The survey instrument comprised seven sections with details presented in (Supplementary file S1). Briefly, the survey began with an introductory section including the mandatory electronic consent item.

Second, the socio-demographics section assessed age, sex, occupational category, governorate, educational level, monthly income of household in Iraqi dinar (IQD, 500,000 IQD ≅ 342.55529 US Dollars); (Xe Currency Converter, 2022, Iraq Ministry of Finance, 2022), and history of chronic disease.

Third, a section on COVID-19 history of infection and COVID-19 vaccine uptake. Fourth, a section on the attitude of the participants towards COVID-19 vaccination, comprising the following question: “In your personal opinion, how would you rate the importance of getting the vaccine to protect against COVID-19?”. The item was measured on a 5-point Likert scale: very important, important, neutral/no opinion, not important, and not important at all. Fifth, assessment of COVID-19 misinformation, with three items based on previous studies addressing COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the Middle East (Sallam et al., 2021, Sallam et al., 2021). Sixth, assessment of the sources of COVID-19 vaccine information. Finally, the seventh section on assessment of COVID-19 vaccine conspiracy beliefs using seven items based on the original vaccine conspiracy beliefs scale (VCBS) adopted from Shapiro et al. that was used previously in the assessment of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and influenza vaccine uptake (Sallam et al., 2021, Shapiro et al., 2016, Sallam et al., 2022). Content validity was assessed by the first and senior authors through reviewing the survey items with minor refinements to improve relevance and comprehensiveness. Subsequently, we conducted a pilot test involving six adult Iraqi individuals excluding these responses from final analysis. Additionally, construct validity was established by earlier work in the context of COVID-19 vaccination (Sallam et al., 2021, Sallam et al., 2021). The Cronbach α value for the VCBS was 0.893 indicating excellent internal consistency of the scale.

2.3. Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Scientific and Ethical Unit at Al-Kindy College of Medicine, University of Baghdad (approved by the Council of Al-Kindy College of Medicine in session No. 20, date: 6 July 2022) and complied to the guidelines for protection of participants’ safety and privacy An electronic informed consent was required for successful completion of the survey.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Data and statistical analyses were conducted using BM SPSS v26.0 for Windows. Univariate analyses were conducted employing the chi-squared (χ2) test. Associations with a significance level of p < 0.100 in univariate analyses were considered for inclusion in subsequent multivariate analysis. Multivariate analysis was conducted using multinomial logistic regression. The Nagelkerke R2 statistic was employed to assess the variance explained by the model. A significance threshold of p < 0.050 was applied to determine statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. Study sample characteristics, attitude towards COVID-19 vaccination, COVID-19 vaccine uptake and its associated variables

The study sample comprised a total of 2544 individuals. Characteristics of the study sample is shown in (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the study participants who were adult Iraqi citizens with data collected during August–September 2022 (N = 2544).

| Variable | Category | N 4 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 1230 (48.3) |

| Female | 1314 (51.7) | |

| Age | ≤ 27 years | 1218 (47.9) |

| > 27 years | 1326 (52.1) | |

| Occupation | HCW 2 | 262 (10.3) |

| Employed (non-HCW) | 1093 (43.0) | |

| Unemployed | 202 (7.9) | |

| Student | 987 (38.8) | |

| Place of residence | Baghdad | 1494 (58.7) |

| Outside Baghdad | 1050 (41.3) | |

| Education | High school or less | 180 (7.1) |

| Undergraduate | 1534 (60.3) | |

| Postgraduate | 830 (32.6) | |

| Income | ≤ 500 K IQD 3 | 668 (26.3) |

| > 500 K IQD | 1876 (73.7) | |

| History of chronic disease | Yes | 381 (15.0) |

| No | 2163 (85.0) | |

| History of COVID-19 1 | Confirmed infection | 1526 (60.0) |

| No history of confirmed infection | 1018 (40.0) | |

| How many times the participant got COVID-19? | 0 | 1018 (40.0) |

| 1 | 876 (34.4) | |

| 2 | 490 (19.3) | |

| 3 | 135 (5.3) | |

| 4 | 25 (1.0) | |

| COVID-19 vaccine uptake | Yes | 2226 (87.5) |

| No | 318 (12.5) | |

| Vaccine type received | Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine | 1651 (74.2) |

| Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine | 172 (7.7) | |

| Sinopharm BBIBP vaccine | 343 (15.4) | |

| Others | 9 (0.4) | |

| Mixed | 51 (2.3) | |

| Number of doses received | 0 | 318 (12.5) |

| 1 | 255 (10.0) | |

| 2 | 1800 (70.8) | |

| 3 | 166 (6.5) | |

| 4 | 5 (0.2) |

COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019; 2 HCW: Healthcare worker; 3 K IQD: 1000 Iraqi dinars; 4N: Number.

The overall attitude of the participants towards COVID-19 vaccination was mostly positive (n = 1966, 77.3 %), while neutral attitude was expressed by 345 participants (13.6 %), and negative attitude was expressed by 233 participants (9.2 %).

Using univariate analysis, the following factors were associated with a positive attitude towards COVID-19 vaccination: male sex, age > 27 years, being a healthcare worker (HCW), postgraduate education, and a monthly income > 500 K IQD (Table 2).

Table 2.

Associations between study variables with attitude to COVID-19 vaccination and COVID-19 vaccine uptake in univariate analysis among study participants who were adult Iraqi citizens with data collected during August–September 2022 (N = 2544).

| Variable | Category | Attitude towards COVID-19 vaccination |

p-value, χ2 | Self-reported history of COVID-19 vaccine uptake |

p-value, χ2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive N 4 (%) | Neutral N (%) | Negative N (%) | Yes N (%) | No N (%) | ||||

| Sex | Male | 991 (80.6) | 124 (10.1) | 115 (9.3) | <0.001, 24.695 | 1092 (88.8) | 138 (11.2) | 0.059, 3.570 |

| Female | 975 (74.2) | 221 (16.8) | 118 (9.0) | 1134 (86.3) | 180 (13.7) | |||

| Age | ≤ 27 years | 898 (73.7) | 206 (16.9) | 114 (9.4) | <0.001, 23.276 | 1069 (87.8) | 149 (12.2) | 0.697, 0.152 |

| > 27 years | 1068 (80.5) | 139 (10.5) | 119 (9.0) | 1157 (87.3) | 169 (12.7) | |||

| Occupation | HCW 2 | 222 (84.7) | 27 (10.3) | 13 (5.0) | <0.001, 24.264 | 248 (94.7) | 14 (5.3) | 0.002, 14.561 |

| Employed (non-HCW) | 869 (79.5) | 123 (11.3) | 101 (9.2) | 940 (86.0) | 153 (14.0) | |||

| Unemployed | 151 (74.8) | 32 (15.8) | 19 (9.4) | 176 (87.1) | 26 (12.9) | |||

| Student | 724 (73.4) | 163 (16.5) | 100 (10.1) | 862 (87.3) | 125 (12.7) | |||

| Place of residence | Baghdad | 1141 (76.4) | 214 (14.3) | 139 (9.3) | 0.364, 2.022 | 1274 (85.3) | 220 (14.7) | <0.001, 16.392 |

| Outside Baghdad | 825 (78.6) | 131 (12.5) | 94 (9.0) | 952 (90.7) | 98 (9.3) | |||

| Education | High school or less | 133 (73.9) | 30 (16.7) | 17 (9.4) | <0.001, 25.358 | 149 (82.8) | 31 (17.2) | 0.135, 4.002 |

| Undergraduate | 1145 (74.6) | 240 (15.6) | 149 (9.7) | 1346 (87.7) | 188 (12.3) | |||

| Postgraduate | 688 (82.9) | 75 (9.0) | 67 (8.1) | 731 (88.1) | 99 (11.9) | |||

| Income | ≤500 K IQD 3 | 481 (72.0) | 114 (17.1) | 73 (10.9) | 0.001, 14.561 | 557 (83.4) | 111 (16.6) | <0.001, 14.036 |

| >500 K IQD | 1485 (79.2) | 231 (12.3) | 160 (8.5) | 1669 (89.0) | 207 (11.0) | |||

| History of chronic disease | Yes | 292 (76.6) | 54 (14.2) | 35 (9.2) | 0.929, 0.148 | 340 (89.2) | 41 (10.8) | 0.266, 1.239 |

| No | 1674 (77.4) | 291 (13.5) | 198 (9.2) | 1886 (87.2) | 277 (12.8) | |||

| History of COVID-19 1 | Confirmed infection | 1171 (76.7) | 218 (14.3) | 137 (9.0) | 0.415, 1.758 | 1362 (89.3) | 164 (10.7) | 0.001, 10.714 |

| No history of confirmed infection | 795 (78.1) | 127 (12.5) | 96 (9.4) | 864 (84.9) | 154 (15.1) | |||

COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019; 2 HCW: Healthcare worker; 3 K IQD: 1000 Iraqi dinars; 4N: Number.

The majority of participants reported uptake of at least a single dose of COVID-19 vaccination (n = 2226, 87.5 %) while 318 participants had no self-reported history of COVID-19 vaccine uptake (12.5 %). Using univariate analysis, the following factors were associated with COVID-19 vaccine uptake: being an HCW, residence outside the Capital, income > 500 K IQD, and a history of confirmed COVID-19 infection (Table 2).

3.2. The belief in COVID-19 misinformation and the embrace of COVID-19 vaccine conspiracy beliefs

Regarding the belief in COVID-19 misinformation, the complete absence of such beliefs was reported among 731 participants (28.7 %), while a slight belief in misinformation was reported among 922 participants (36.2 %). Moderate belief in misinformation was reported among 576 participants (22.6 %), and the strong belief in COVID-19 misinformation was observed among 315 participants (12.4 %). For the attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine conspiracies, the majority of participants exhibited a neutral attitude (n = 1464, 57.5 %), with 607 participants showing the embrace of COVID-19 vaccine conspiracies (23.9 %), and 473 showing disagreement with such beliefs (18.6 %).

In univariate analysis, the strong belief in COVID-19 misinformation and the agreement with COVID-19 vaccine conspiracies were associated with both negative attitude to COVID-19 vaccination and less COVID-19 vaccine uptake (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association between attitude to vaccine conspiracies, COVID-19 misinformation and attitude to COVID-19 vaccination/COVID-19 vaccination uptake in univariate analysis among study participants who were adult Iraqi citizens with data collected during August–September 2022 (N = 2544).

| Variable | Category | Attitude towards COVID-19 vaccination |

p-value, χ2 | COVID-19 vaccine uptake |

p-value, χ2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive N 4 (%) | Neutral N (%) | Negative N (%) | Yes N (%) | No N (%) | ||||

| Misinformation score 1 | No belief in misinformation | 665 (91.0) | 51 (7.0) | 15 (2.1) | <0.001, 303.899 | 688 (94.1) | 43 (5.9) | <0.001, 75.253 |

| Slight belief in misinformation | 767 (83.2) | 102 (11.1) | 53 (5.7) | 820 (88.9) | 102 (11.1) | |||

| Moderate belief in misinformation | 381 (66.1) | 110 (19.1) | 85 (14.8) | 475 (82.5) | 101 (17.5) | |||

| Strong belief in misinformation | 153 (48.6) | 82 (26.0) | 80 (25.4) | 243 (77.1) | 72 (22.9) | |||

| Attitude towards COVID-19 2 vaccine conspiracy | Disagreement (VCBS 3: 7–20) | 455 (96.2) | 11 (2.3) | 7 (1.5) | <0.001, 346.968 | 452 (95.6) | 21 (4.4) | <0.001, 96.532 |

| Neutral (VCBS: 21–35) | 1168 (79.8) | 224 (15.3) | 72 (4.9) | 1308 (89.3) | 156 (10.7) | |||

| Agreement (VCBS: 36–49) | 343 (56.5) | 110 (18.1) | 154 (25.4) | 466 (76.8) | 141 (23.2) | |||

Misinformation score: Using three items to assess the belief in COVID-19 misinformation

COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019.

VCBS: Vaccine conspiracy beliefs scale.

N: Number.

3.3. Source of information about COVID-19 vaccines

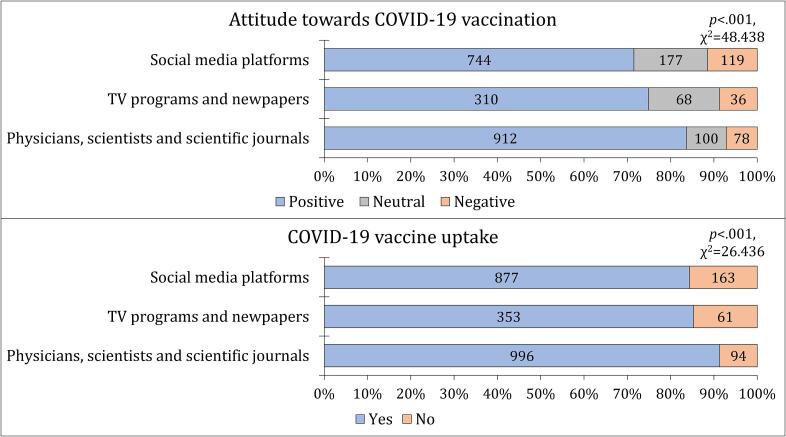

The main sources of information regarding COVID-19 vaccination included physicians, scientists, and scientific journals (n = 1090, 42.8 %), followed closely by social media platforms (n = 1040, 40.9 %), and finally TV programs and newspapers (n = 414, 16.3 %). The dependence on social media platforms was associated with both negative attitude to COVID-19 vaccination and less COVID-19 vaccine uptake (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The association between attitude towards COVID-19 vaccination, COVID-19 vaccine uptake and the main source of information regarding the vaccine among the study participants who were adult Iraqi citizens with data collected during August–September 2022 (N = 2544). COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019.

3.4. Multivariate analysis for the factors associated with positive attitude towards COVID-19 vaccination

The Nagelkerke R2 value of 0.245 indicated that the regression model explained 24.5 % of the variability observed in the data. For demographic variables, only males were significantly less likely to have a neutral attitude compared to females, with an adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of 0.64 (95 %CI: 0.44–0.92, p = 0.016).

Statistically significant associations were observed between belief in misinformation and COVID-19 vaccine attitude. Participants with no belief in misinformation displayed a significantly higher likelihood of a positive attitude, with an aOR of 7.82 (95 %CI: 4.16–14.68), while those with slight belief exhibited an aOR of 3.75 (95 %CI: 2.46–5.71), and those with moderate belief an aOR of 1.58 (95 %CI: 1.07–2.31), all compared to strong belief (p < 0.001, Table 4). Similarly, those who disagreed with COVID-19 vaccine conspiracy beliefs (VCBS: 7–20) showed a higher likelihood of a positive attitude towards COVID-19 vaccination, with an aOR of 10.42 (95 %CI: 4.62–23.54), while those with a neutral attitude (VCBS: 21–35) displayed an aOR of 4.57 (95 %CI: 3.30–6.33), both compared to those who endorsed vaccine conspiracies (p < 0.001, Table 4). Additionally, the participants with a neutral vaccine conspiracy attitude (VCBS: 21–35) displayed a higher likelihood of a neutral attitude towards COVID-19 vaccination, with an aOR of 4.02 (95 %CI: 2.73–5.92), compared to those who endorsed vaccine conspiracies (p < 0.001, Table 4).

Table 4.

Associations between study variables with attitude to COVID-19 vaccination in multinomial logistic regression analyses, among study participants who were adult Iraqi citizens with data collected during August–September 2022 (N = 2544).

| Model | Nagelkerke R2 = 0.245 | aOR 6 (95 % CI 7) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive attitude vs. negative attitude towards COVID-19 vaccination | |||

| Sex | Male | 0.99 (0.73–1.35) | 0.951 |

| Female | Ref. | . | |

| Age | ≤ 27 years | 0.93 (0.60–1.45) | 0.763 |

| > 27 years | Ref. | . | |

| Occupation | HCW 3 | 1.52 (0.77–2.98) | 0.229 |

| Employed (non-HCW) | 1.04 (0.67–1.63) | 0.857 | |

| Unemployed | 1.03 (0.58–1.83) | 0.922 | |

| Student | Ref. | . | |

| Education | High school or less | 0.80 (0.42–1.54) | 0.506 |

| Undergraduate | 0.74 (0.50–1.10) | 0.139 | |

| Postgraduate | Ref. | . | |

| Income | ≤500 K IQD 4 | 1.03 (0.73–1.46) | 0.873 |

| >500 K IQD | Ref. | . | |

| Misinformation score 1 | No belief in misinformation | 7.82 (4.16–14.68) | <0.001 |

| Slight belief in misinformation | 3.75 (2.46–5.71) | <0.001 | |

| Moderate belief in misinformation | 1.58 (1.07–2.31) | 0.020 | |

| Strong belief in misinformation | Ref. | . | |

| Attitude towards COVID-19 2 vaccine conspiracy | Disagreement (VCBS 5: 7–20) | 10.42 (4.62–23.54) | <0.001 |

| Neutral (VCBS: 21–35) | 4.57 (3.30–6.33) | <0.001 | |

| Agreement (VCBS: 36–49) | Ref. | . | |

| Source of information regarding COVID-19 vaccination | Physicians, scientists and scientific journals | 1.26 (0.90–1.75) | 0.179 |

| TV programs and newspapers | 1.43 (0.93–2.19) | 0.105 | |

| Social media platforms | Ref. | . | |

| Neutral attitude vs. negative attitude towards COVID-19 vaccination | |||

| Sex | Male | 0.64 (0.44–0.92) | 0.016 |

| Female | Ref. | . | |

| Age | ≤ 27 years | 1.38 (0.83–2.31) | 0.217 |

| > 27 years | Ref. | . | |

| Occupation | HCW | 1.49 (0.69–3.21) | 0.314 |

| Employed (non-HCW) | 1.17 (0.69–1.96) | 0.562 | |

| Unemployed | 1.10 (0.57–2.11) | 0.774 | |

| Student | Ref. | . | |

| Education | High school or less | 1.31 (0.61–2.78) | 0.488 |

| Undergraduate | 1.17 (0.73–1.87) | 0.512 | |

| Postgraduate | Ref. | . | |

| Income | ≤500 K IQD 3 | 1.00 (0.68–1.49) | 0.987 |

| >500 K IQD | Ref. | . | |

| Misinformation score | No belief in misinformation | 1.74 (0.85–3.54) | 0.128 |

| Slight belief in misinformation | 1.09 (0.67–1.78) | 0.730 | |

| Moderate belief in misinformation | 0.89 (0.57–1.39) | 0.613 | |

| Strong belief in misinformation | Ref. | . | |

| Attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine conspiracy | Disagreement (VCBS 3: 7–20) | 1.71 (0.61–4.79) | 0.306 |

| Neutral (VCBS: 21–35) | 4.02 (2.73–5.92) | <0.001 | |

| Agreement (VCBS: 36–49) | Ref. | . | |

| Source of information regarding COVID-19 vaccination | Physicians, scientists and scientific journals | 0.85 (0.57–1.26) | 0.415 |

| TV programs and newspapers | 1.38 (0.85–2.25) | 0.191 | |

| Social media platforms | Ref. | . | |

Misinformation score: Using three items to assess the belief in COVID-19 misinformation.

COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019.

HCW: Healthcare worker.

K IQD: 1000 Iraqi dinars.

VCBS: Vaccine conspiracy beliefs scale.

aOR: Adjusted odds ratio.

CI: Confidence interval. Statistically significant p values are highlighted in bold style.

3.5. Multivariate analysis for the factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine uptake

The Nagelkerke R2 of 0.128 showed that the regression model explained 12.8 % of the variability observed in the data. Participants residing in Baghdad were less likely to have received the COVID-19 vaccine, as indicated by an aOR of 0.56 (95 %CI: 0.43–0.73, p < 0.001, Table 5), compared to those residing outside Baghdad. Employed individuals in non-healthcare roles were significantly less likely to have received the COVID-19 vaccine, with an aOR of 0.70 (95 %CI: 0.52–0.93, p = 0.015, Table 5) compared to university/college students. Individuals with a history of COVID-19 infection showed higher rates of COVID-19 vaccine uptake, with an aOR of 1.53 (95 %CI: 1.19–1.97, p = 0.001, Table 5). Additionally, participants with an income of ≤ 500 K IQD showed less likelihood of COVID-19 vaccine uptake, with an aOR of 0.66 (95 %CI: 0.50–0.88), compared to those with incomes exceeding 500 K IQD (p = 0.004, Table 5).

Table 5.

Associations between study variables with COVID-19 vaccine uptake in multinomial logistic regression analyses, among study participants who were adult Iraqi citizens with data collected during August–September 2022 (N = 2544).

| Model | Nagelkerke R2 = 0.128 | aOR 6 (95 % CI 7) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 vaccine uptake vs. no history of COVID-19 vaccination | |||

| Sex | Male | 1.27 (0.97–1.64) | 0.079 |

| Female | Ref. | . | |

| Place of residence | Baghdad | 0.56 (0.43–0.73) | <0.001 |

| Outside Baghdad | Ref. | . | |

| Occupation | HCW 3 | 1.69 (0.93–3.07) | 0.083 |

| Employed (non-HCW) | 0.70 (0.52–0.93) | 0.015 | |

| Unemployed | 1.00 (0.62–1.60) | 0.985 | |

| Student | Ref. | . | |

| History of COVID-19 | Yes | 1.53 (1.19–1.97) | 0.001 |

| No | Ref. | . | |

| Income | ≤500 K IQD 4 | 0.66 (0.50–0.88) | 0.004 |

| >500 K IQD | Ref. | . | |

| Misinformation score 1 | No belief in misinformation | 2.29 (1.45–3.61) | <0.001 |

| Slight belief in misinformation | 1.49 (1.04–2.15) | 0.031 | |

| Moderate belief in misinformation | 1.08 (0.75–1.54) | 0.687 | |

| Strong belief in misinformation | Ref. | . | |

| Attitude towards COVID-19 2 vaccine conspiracy | Disagreement (VCBS 5: 7–20) | 3.65 (2.16–6.18) | <0.001 |

| Neutral (VCBS: 21–35) | 2.06 (1.56–2.71) | <0.001 | |

| Agreement (VCBS: 36–49) | Ref. | . | |

| Source of information regarding COVID-19 vaccination | Physicians, scientists and scientific journals | 1.46 (1.10–1.94) | 0.009 |

| TV programs and newspapers | 1.13 (0.81–1.58) | 0.469 | |

| Social media platforms | Ref. | . | |

Misinformation score: Using three items to assess the belief in COVID-19 misinformation

COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019

HCW: Healthcare worker

K IQD: 1000 Iraqi dinars

VCBS: Vaccine conspiracy beliefs scale

aOR: Adjusted odds ratio

CI: Confidence interval. Statistically significant p values are highlighted in bold style.

Moreover, participants who reported no belief in COVID-19 misinformation exhibited a significantly higher likelihood of COVID-19 vaccine uptake, reflected in an aOR of 2.29 (95 %CI: 1.45–3.61) compared to those with strong beliefs in misinformation (p < 0.001). Also, participants with a slight belief in misinformation demonstrated a higher likelihood of COVID-19 vaccine uptake, with an aOR of 1.49 (95 %CI: 1.04–2.15, p = 0.031, Table 5). A higher likelihood of COVID-19 vaccine uptake was observed among the participants who disagreed with COVID-19 vaccine conspiracy beliefs (VCBS: 7–20) reflected by an aOR of 3.65 (95 %CI: 2.16–6.18), and among participants with neutral attitude towards vaccine conspiracies (VCBS: 21–35) with an aOR of 2.06 (95 %CI: 1.56–2.71) compared to those who endorsed vaccine conspiracies (p < 0.001 for both comparisons, Table 5). Finally, participants who relied on physicians, scientists, and scientific journals as their source of information regarding COVID-19 vaccination exhibited a significantly increased likelihood of COVID-19 vaccine uptake, as indicated by an aOR of 1.46 (95 %CI: 1.10–1.94, p = 0.009, Table 5) compared to those who relied on social media platforms.

4. Discussion

The current study revealed a clear distinct pattern in the possible factors influencing COVID-19 vaccination attitudes and uptake. Notably, lower vaccine uptake and negative attitudes towards the vaccine were significantly associated with endorsement of vaccine conspiracies and COVID-19 misinformation.

In comparison to previous studies in Iraq, the participants in the current study demonstrated a favorable attitude towards COVID-19 vaccination. For example, an earlier study indicated that 77.6% of respondents were willing to take the vaccine when available, a rate almost exactly the same of the current study findings which indicated that 77.3% displayed a positive attitude to COVID-19 vaccination (Ghazi et al., 2021). Another Iraqi study in 2021 reported a lower acceptance rate of 56.2% (Shareef et al., 2022). On the other hand, another survey study in July 2021 found that 88.6 % of respondents were willing to be vaccinated against COVID-19, with concerns about vaccine safety and the need for more information being the primary reasons for vaccine refusal (Al-Qerem et al., 2022).

From a global perspective, the acceptance rate observed in this study is slightly higher than the global average of 65–75% (Norhayati et al., 2021, Fajar et al., 2022). Despite the observed variability in the rates of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance which can be attributed to survey timing, phrasing the of the items assessing vaccination hesitancy, and possible sampling bias, the common pattern in line with our findings is the generally positive attitude towards COVID-19 vaccination in Iraq (Sallam, 2021, Shareef et al., 2022, Al-Qerem et al., 2022, Darweesh et al., 2022).

A notable aspect of this study was the discernible correlation between COVID-19 vaccine conspiracies, COVID-19 misinformation, and negative attitudes and behaviors towards COVID-19 vaccination. This manifested in significantly lower vaccine uptake and less favorable attitudes towards the vaccine. The government in Iraq has taken measures to combat COVID-19 misinformation, emphasizing the importance of vaccination and warning against spreading false information (Iraqi News Agency, 2023, Iraqi News Agency, 2023).

The Iraqi government adopted a non-mandatory approach regarding COVID-19 vaccination, refraining from imposing vaccine mandates due to the lack of legal support of this measure (Iraqi News Agency, 2023). Instead, the Iraqi Ministry of Health and Environment advocated for alternative public health strategies. In Iraq, the employees were encouraged to voluntarily provide either a weekly COVID-19 testing card or a vaccination card as a prerequisite for work attendance without punishing measures against unvaccinated employees (Iraqi News Agency, 2023). The Iraqi government also initiated vaccination campaigns to enhance COVID-19 vaccine coverage, with comprehensive plans to increase vaccine supply and to expand vaccination facilities, with a particular focus on vaccinating HCWs to counter vaccine-related misinformation effectively (Iraqi News Agency, 2023, WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, 2023).

The findings of the current study highlighted the significant association between conspiracy beliefs and negative health behavior manifested in lower COVID-19 vaccine uptake. Extensive evidence has consistently highlighted the widespread presence of medical conspiracy theories and their impact on various aspects of health-related behaviors, including the willingness to get vaccinated and actual vaccine uptake (Sallam et al., 2021, Sallam et al., 2022, Ripp and Röer, 2022, van Mulukom et al., 2022, van Prooijen et al., 2023, Alsanafi et al., 2023, Kowalska-Duplaga and Duplaga, 2023). The adoption of conspiracy theories can exert a direct influence on individual engagement behaviors, including health-related practices (van Prooijen and Douglas, 2018, Douglas et al., 2017, Bierwiaczonek et al., 2022). For example, the detrimental impact of embracing COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs on compliance with government-imposed restrictions, adherence to preventive measures, and willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccination was shown in a study from the U.S. (Romer and Jamieson, 2020). Similarly, research conducted in Finland demonstrated that the endorsement of COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs was associated with lower support for pandemic-related governmental restrictions (Pivetti et al., 2021). In the Arab countries of the Middle East, the COVID-19 vaccine conspiracies were shown to be associated with higher rates of vaccine hesitancy/rejection (Sallam et al., 2021, Sallam et al., 2021).

In the current study, an interesting observation was the striking contrast in the determinants of participants’ attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination compared to their actual vaccine uptake. Notably, the demographic variables appeared to play a minimal role in shaping attitudes, whereas several demographic variables were significantly correlated with actual vaccine uptake. This divergence between attitudes and behavior can be attributed to the inherent distinction between what people think or feel representing attitudes, and what they actually do manifested in behavior (Yuan et al., 2023). Attitudes often reflect abstract viewpoints and personal beliefs, while behavior could be influenced by a range of external factors, including governmental policies and societal expectations (Ajzen and Fishbein, 2005, Ajzen, 2020). Thus, it is conceivable that individuals may hold certain attitudes about vaccination but, when faced with practical circumstances, their behavior may align differently.

The major finding in this study was demonstrating the association between vaccine conspiracy beliefs, misinformation, and negative attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination, as well as a reduced likelihood of vaccine uptake. Plausible explanations of this association could be based on the previous and recent evidence highlighting the impact of conspiracies and misinformation on vaccination behavior (van Mulukom et al., 2022, Bertin et al., 2020, Altman et al., 2023, Loomba et al., 2021). Conspiracy theories and misinformation have the potential to deter individuals from getting vaccinated through reducing vaccine confidence (Ullah et al., 2021, Jolley and Douglas, 2014). Endorsing conspiracy beliefs can undermine trust in healthcare systems, governmental agencies, and pharmaceutical companies (Milošević Đorđević et al., 2021, Bonetto and Arciszewski, 2021). Trust is an essential aspect in decision-making process to get vaccinated (Larson et al., 2018, Sapienza and Falcone, 2022). Hence, compromised trust could result in negative attitude towards vaccination due to fear of not being provided with accurate and safe preventive measures (Seddig et al., 2022).

Additionally, the current study showed that the source of information could play an important role in COVID-19 vaccine uptake. Health misinformation often spreads through channels that may lack credibility, such as social media platforms (Muhammed and Mathew, 2022, Pennycook and Rand, 2021, Suarez-Lledo and Alvarez-Galvez, 2021). When individuals rely on social media for health information, they may inadvertently expose themselves to distorted views on vaccine safety and efficacy (Ngai et al., 2022). The current study results were consistent with this point of view by revealing that COVID-19 vaccine uptake was lower among participants who relied on social media platforms compared to individuals who sought vaccine information from scientifically credible sources (e.g., physicians, scientists, etc.).

Besides the important roles of vaccine conspiracy beliefs and misinformation, it is worth mentioning the other factors were linked with actual COVID-19 vaccine uptake in this study. These factors could offer useful insights into the complexity of the vaccine uptake as a health behavior. First, participants living outside the Capital, Baghdad exhibited higher COVID-19 vaccine uptake. This suggests that targeted efforts should be made to prioritize vaccination campaigns in the Capital city. Additionally, lower income was associated with lower COVID-19 vaccine uptake, which emphasizes the importance of addressing socio-economic disparities to ensure equitable access to COVID-19 vaccination. Furthermore, the history of COVID-19 infection appeared to influence vaccination behavior, though the exact nature of this relationship is not discernible. It is possible that individuals who had experienced the disease may have been less complacent about vaccination due to their disease experience. However, establishing a direct cause-and-effect relationship in this regard can be challenging and requires further investigation. Finally, in this study, university/college students, as a group, exhibited higher COVID-19 vaccination rates. This aligns with previous research and can be attributed to the view that students are generally more informed and engaged in health-related matters (Sallam et al., 2021, Patrinely et al., 2020).

Lastly, it is essential to acknowledge the limitations of this study, which should be considered carefully in any attempt to generalize the results as follows. The possibility of response bias should be considered with participants who chose to respond to the survey being not representative of the entire adult population in Iraq. Additionally, individuals with stronger opinions, whether positive or negative, about COVID-19 vaccination might have been more motivated to participate in the study resulting in response bias, with subsequent over- or under-estimation of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy/resistance and misinformation levels. The study employed a cross-sectional design, which is helpful for elucidating associations but cannot establish causality. Additionally, the cross-sectional design precluded drawing definitive conclusions about the temporal trends in vaccination attitudes and behaviors. It is recommended to conduct longitudinal studies to establish causal relationships and to analyze the temporal trends. The current study utilized the chain-referral sampling method to recruit participants, which is a non-random sampling method possibly introducing selection bias; therefore, the sample may not be fully representative of the broader adult Iraqi population. In addition, the study inevitably excluded certain groups, such as individuals without internet access, further deepening the issue of possible selection bias. The findings of this study may not be easily generalizable to other regions or countries with different cultural, social, or healthcare contexts, based on the attributes of vaccine hesitancy as a phenomenon. Subsequently, this could compromise the generalizability of the study results on the global level. Social desirability bias should be considered since the participants might have provided what they believed as socially acceptable responses. This could have led to over-reporting positive attitudes towards vaccination and under-reporting negative vaccination attitudes endorsing conspiracy beliefs.

5. Conclusions

This study provided valuable insights into the interplay between COVID-19 vaccine conspiracies, COVID-19 misinformation, and negative health attitudes and behaviors, which were manifested in lower COVID-19 vaccine uptake and unfavorable attitudes towards the vaccine.

These results emphasized the critical need for targeted interventions aiming to address misinformation and to enhance COVID-19 vaccine literacy. Engaging HCWs as advocates for vaccination can play key role in improving vaccine acceptance and uptake among, highlighted by their significant role as a source of information among participants who had higher rates of COVID-19 vaccine uptake. Furthermore, tailoring communication strategies to specific demographics can be an important measure for effectively countering COVID-19 vaccine-related uptake challenges. Ultimately, these strategies can help to increase vaccine acceptance resulting in a positive impact on the global health.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Malik Sallam: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Nariman Kareem: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation. Mohammed Alkurtas: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2024.102791.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author (Malik Sallam).

References

- Abdaljaleel M., Barakat M., Mahafzah A., Hallit R., Hallit S., Sallam M. TikTok content on measles-rubella vaccine in Jordan: A cross-sectional study highlighting the spread of vaccine misinformation. JMIR Preprints. 2023 doi: 10.2196/preprints.53458. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abdulah D.M. Prevalence and correlates of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the general public in Iraqi Kurdistan: A cross-sectional study. J. Med. Virol. 2021;93:6722–6731. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies. 2020;2:314–324. doi: 10.1002/hbe2.195. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I., Fishbein M. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; Mahwah, NJ, US: 2005. The Influence of Attitudes on Behavior. The handbook of attitudes; pp. 173–221. [Google Scholar]

- Alatrany S.S.J., Falaiyah A.M., Zuhairawi R.H.M., Ogden R., Alsa H., Alatrany A.S.S., et al. A cross-sectional analysis of the predictors of COVID-19 vaccine uptake and vaccine hesitancy in Iraq. PLoS One. 2023;18 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0282523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Qerem W., Hammad A., Alsajri A.H., Al-Hishma S.W., Ling J., Mosleh R. COVID-19 Vaccination Acceptance and Its Associated Factors Among the Iraqi Population: A Cross Sectional Study. Patient Prefer. Adherence. 2022;16:307–319. doi: 10.2147/ppa.S350917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Rawi A., Fakida A., Grounds K. Investigation of COVID-19 Misinformation in Arabic on Twitter: Content Analysis. JMIR Infodemiology. 2022;2 doi: 10.2196/37007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsanafi M., Salim N.A., Sallam M. Willingness to get HPV vaccination among female university students in Kuwait and its relation to vaccine conspiracy beliefs. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2023;19:2194772. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2023.2194772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman J.D., Miner D.S., Lee A.A., Asay A.E., Nielson B.U., Rose A.M., et al. Factors Affecting Vaccine Attitudes Influenced by the COVID-19 Pandemic. Vaccines (basel) 2023;11:516. doi: 10.3390/vaccines11030516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertin P., Nera K., Delouvée S. Conspiracy Beliefs, Rejection of Vaccination, and Support for hydroxychloroquine: A Conceptual Replication-Extension in the COVID-19 Pandemic Context. Front. Psychol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.565128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierwiaczonek K., Gundersen A.B., Kunst J.R. The role of conspiracy beliefs for COVID-19 health responses: A meta-analysis. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022;46 doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonetto E., Arciszewski T. The Creativity of Conspiracy Theories. J. Creat. Behav. 2021;55:916–924. doi: 10.1002/jocb.497. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clemente-Suárez V.J., Navarro-Jiménez E., Moreno-Luna L., Saavedra-Serrano M.C., Jimenez M., Simón J.A., et al. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Social, Health, and Economy. Sustainability. 2021;6314 doi: 10.3390/su13116314. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Data Commons. Iraq: Country in Asia. Available online: https://datacommons.org/place/country/IRQ?utm_medium=explore&mprop=count&popt=Person&hl=en (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Darweesh O., Khatab N., Kheder R., Mohammed T., Faraj T., Ali S., et al. Assessment of COVID-19 vaccination among healthcare workers in Iraq; adverse effects and hesitancy. PLoS One. 2022;17 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0274526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas K.M., Sutton R.M., Cichocka A. The Psychology of Conspiracy Theories. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2017;26:538–542. doi: 10.1177/0963721417718261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubé E., Gagnon D., Nickels E., Jeram S., Schuster M. Mapping vaccine hesitancy–country-specific characteristics of a global phenomenon. Vaccine. 2014;32:6649–6654. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epitools - Epidemiological Calculators. Sample size to estimate a simple proportion (apparent prevalence). Available online: https://epitools.ausvet.com.au/oneproportion (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Fajar J.K., Sallam M., Soegiarto G., Sugiri Y.J., Anshory M., Wulandari L., et al. Global Prevalence and Potential Influencing Factors of COVID-19 Vaccination Hesitancy: A Meta-Analysis. Vaccines (basel) 2022;10:1356. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10081356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galagali P.M., Kinikar A.A., Kumar V.S. Vaccine Hesitancy: Obstacles and Challenges. Curr Pediatr Rep. 2022;10:241–248. doi: 10.1007/s40124-022-00278-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghazi H., Taher T., Alfadhul S., Al-Mahmood S., Hassan S., Hamoudi T., et al. Acceptance Of Covid-19 Vaccine Among General Population In Iraq: Acceptance Of Covid-19 Vaccine Among General Population In Iraq. Iraqi Nat. J. Med. 2021;3:93–103. Available from: https://www.iqnjm.com/index.php/homepage/article/view/45. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood B. The contribution of vaccination to global health: past, present and future. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2014;369:20130433. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greyling T., Rossouw S. Positive attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccines: A cross-country analysis. PLoS One. 2022;17 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0264994. e0264994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iraq Ministry of Finance. Payroll law (in Arabic). Available online: http://www.mof.gov.iq/pages/ar/SalaryLaw.aspx (accessed on 26 November 2022).

- Iraqi News Agency. [The Ministry of Interior reveals its measures against those spreading rumors on social media] in Arabic. Available online: https://www.ina.iq/132474--.html (accessed on 21 October 2023).

- Iraqi News Agency. [Health is taking measures against those who incite not to receive the vaccine] in Arabic. Available online: https://www.ina.iq/132234--.html (accessed on 21 October 2023).

- Iraqi News Agency. [Health resolves the controversy over compulsory vaccination of employees and identifies the groups excluded from vaccination] in Arabic. Available online: https://www.ina.iq/130053--.html (accessed on 21 October 2023).

- Jolley D., Douglas K.M. The effects of anti-vaccine conspiracy theories on vaccination intentions. PLoS One. 2014;9:e89177. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashte S., Gulbake A., El-Amin Iii S.F., Gupta A. COVID-19 vaccines: rapid development, implications, challenges and future prospects. Hum. Cell. 2021;34:711–733. doi: 10.1007/s13577-021-00512-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayser V., Ramzan I. Vaccines and vaccination: history and emerging issues. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2021;17:5255–5268. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1977057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalska-Duplaga K., Duplaga M. The association of conspiracy beliefs and the uptake of COVID-19 vaccination: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2023;23:672. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-15603-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson H.J., Jarrett C., Eckersberger E., Smith D.M., Paterson P. Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: a systematic review of published literature, 2007–2012. Vaccine. 2014;32:2150–2159. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson H.J., Clarke R.M., Jarrett C., Eckersberger E., Levine Z., Schulz W.S., et al. Measuring trust in vaccination: A systematic review. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2018;14:1599–1609. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2018.1459252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson H.J., Gakidou E., Murray C.J.L. The Vaccine-Hesitant Moment. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022;387:58–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra2106441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loomba S., de Figueiredo A., Piatek S.J., de Graaf K., Larson H.J. Measuring the impact of COVID-19 vaccine misinformation on vaccination intent in the UK and USA. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021;5:337–348. doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luma A.H., Haveen A.H., Faiq B.B., Stefania M., Leonardo E.G. Hesitancy towards Covid-19 vaccination among the healthcare workers in Iraqi Kurdistan. Public Health Pract (oxf) 2022;3 doi: 10.1016/j.puhip.2021.100222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald N.E. Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;33:4161–4164. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milošević Đorđević J., Mari S., Vdović M., Milošević A. Links between conspiracy beliefs, vaccine knowledge, and trust: Anti-vaccine behavior of Serbian adults. Soc Sci Med. 2021;277 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motta M., Sylvester S., Callaghan T., Lunz-Trujillo K. Encouraging COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake Through Effective Health Communication. Frontiers in Political Science. 2021;3 doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.630133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muhammed T.S., Mathew S.K. The disaster of misinformation: a review of research in social media. International Journal of Data Science and Analytics. 2022;13:271–285. doi: 10.1007/s41060-022-00311-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngai C.S.B., Singh R.G., Yao L. Impact of COVID-19 Vaccine Misinformation on Social Media Virality: Content Analysis of Message Themes and Writing Strategies. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022;24 doi: 10.2196/37806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norhayati M.N., Che Yusof R., Azman Y.M. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of COVID-19 Vaccination Acceptance. Front Med (lausanne) 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.783982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver J.E., Wood T. Medical conspiracy theories and health behaviors in the United States. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014;174:817–818. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrinely J.R., Zakria D., Berkowitz S.T., Johnson D.B., Totten D.J. COVID-19: the Emerging Role of Medical Student Involvement. Medical Science Educator. 2020;30:1641–1643. doi: 10.1007/s40670-020-01052-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennycook G., Rand D.G. The Psychology of Fake News. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2021;25:388–402. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2021.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peretti-Watel P., Larson H.J., Ward J.K., Schulz W.S., Verger P. Vaccine hesitancy: clarifying a theoretical framework for an ambiguous notion. PLoS Curr. 2015:7. doi: 10.1371/currents.outbreaks.6844c80ff9f5b273f34c91f71b7fc289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pivetti M., Di Battista S., Paleari F.G., Hakoköngäs E. Conspiracy beliefs and attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccinations: A conceptual replication study in Finland. J. Pac. Rim Psychol. 2021;15 doi: 10.1177/18344909211039893. 18344909211039893. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poland G.A., Jacobson R.M. Understanding those who do not understand: a brief review of the anti-vaccine movement. Vaccine. 2001;19:2440–2445. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(00)00469-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay M., White J. MMR vaccine coverage falls after adverse publicity. Commun. Dis. Rep. CDR Wkly. 1998;8(41):4. doi: 10.2807/esw.02.06.01260-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regazzi L., Lontano A., Cadeddu C., Di Padova P., Rosano A. Conspiracy beliefs, COVID-19 vaccine uptake and adherence to public health interventions during the pandemic in Europe. Eur. J. Pub. Health. 2023;33:717–724. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckad089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ripp T., Röer J.P. Systematic review on the association of COVID-19-related conspiracy belief with infection-preventive behavior and vaccination willingness. BMC Psychology. 2022;10:66. doi: 10.1186/s40359-022-00771-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues C.M.C., Plotkin S.A. Impact of Vaccines; Health, Economic and Social Perspectives. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:1526. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romer D., Jamieson K.H. Conspiracy theories as barriers to controlling the spread of COVID-19 in the U.S. Soc Sci Med. 2020;263 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallam M. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Worldwide: A Concise Systematic Review of Vaccine Acceptance Rates. Vaccines (basel) 2021;9:160. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9020160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallam M., Dababseh D., Yaseen A., Al-Haidar A., Taim D., Eid H., et al. COVID-19 misinformation: Mere harmless delusions or much more? A knowledge and attitude cross-sectional study among the general public residing in Jordan. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0243264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallam M., Dababseh D., Eid H., Al-Mahzoum K., Al-Haidar A., Taim D., et al. High Rates of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Its Association with Conspiracy Beliefs: A Study in Jordan and Kuwait among Other Arab Countries. Vaccines. 2021;42 doi: 10.3390/vaccines9010042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallam M., Dababseh D., Eid H., Hasan H., Taim D., Al-Mahzoum K., et al. Low COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance Is Correlated with Conspiracy Beliefs among University Students in Jordan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;2407 doi: 10.3390/ijerph18052407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallam M., Al-Sanafi M., Sallam M. A Global Map of COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance Rates per Country: An Updated Concise Narrative Review. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2022;15:21–45. doi: 10.2147/jmdh.S347669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallam M., Eid H., Awamleh N., Al-Tammemi A.B., Barakat M., Athamneh R.Y., et al. Conspiratorial attitude of the general public in jordan towards emerging virus infections: A cross-sectional study amid the 2022 Monkeypox outbreak. Trop Med Infect. Dis. 2022;7 doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed7120411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallam M., Ghazy R.M., Al-Salahat K., Al-Mahzoum K., AlHadidi N.M., Eid H., et al. The Role of Psychological Factors and Vaccine Conspiracy Beliefs in Influenza Vaccine Hesitancy and Uptake among Jordanian Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Vaccines. 2022;1355 doi: 10.3390/vaccines10081355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapienza A., Falcone R. The Role of Trust in COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance: Considerations from a Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022;20:665. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20010665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid P., Rauber D., Betsch C., Lidolt G., Denker M.L. Barriers of Influenza Vaccination Intention and Behavior - A Systematic Review of Influenza Vaccine Hesitancy, 2005–2016. PLoS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seddig D., Maskileyson D., Davidov E., Ajzen I., Schmidt P. Correlates of COVID-19 vaccination intentions: Attitudes, institutional trust, fear, conspiracy beliefs, and vaccine skepticism. Soc Sci Med. 2022;302 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro G.K., Holding A., Perez S., Amsel R., Rosberger Z. Validation of the vaccine conspiracy beliefs scale. Papillomavirus Research. 2016;2:167–172. doi: 10.1016/j.pvr.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shareef L.G., Fawzi Al-Hussainy A., Majeed H.S. COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy among Iraqi general population between beliefs and barriers: An observational study. F1000Res. 2022;11:334. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.110545.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Lledo V., Alvarez-Galvez J. Prevalence of Health Misinformation on Social Media: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021;23 doi: 10.2196/17187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahir A.I., Ramadhan D.S., Piro S.S., Abdullah R.Y., Taha A.A., Radha R.H. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance, hesitancy and refusal among Iraqi Kurdish population. Int J Health Sci (qassim) 2022;16:10–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toor J., Echeverria-Londono S., Li X., Abbas K., Carter E.D., Clapham H.E., et al. Lives saved with vaccination for 10 pathogens across 112 countries in a pre-COVID-19 world. Elife. 2021;10 doi: 10.7554/eLife.67635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullah I., Khan K.S., Tahir M.J., Ahmed A., Harapan H. Myths and conspiracy theories on vaccines and COVID-19: Potential effect on global vaccine refusals. Vacunas. 2021;22:93–97. doi: 10.1016/j.vacun.2021.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Mulukom V., Pummerer L.J., Alper S., Bai H., Čavojová V., Farias J., et al. Antecedents and consequences of COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs: A systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2022;301 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Prooijen J.W., Douglas K.M. Belief in conspiracy theories: Basic principles of an emerging research domain. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2018;48:897–908. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Prooijen J.W., Etienne T.W., Kutiyski Y., Krouwel A.P.M. Conspiracy beliefs prospectively predict health behavior and well-being during a pandemic. Psychol. Med. 2023;53:2514–2521. doi: 10.1017/s0033291721004438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VIPER Group COVID19 Vaccine Tracker Team. IRAQ: 4 Vaccines Approved for Use in Iraq. Available online: https://covid19.trackvaccines.org/country/iraq/ (accessed on 21 October 2023).

- WHO Health Emergency Dashboard. Number of COVID-19 cases reported to WHO (cumulative total) Iraq. Available online: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/cases?m49=368&n=c (accessed on 17 May 2024).

- WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, Sultany A, Sabaa B. Iraq launches nationwide vaccination campaign to scale up immunity against COVID-19. Available online: https://www.emro.who.int/iraq/news/iraq-launches-nationwide-vaccination-campaign-to-scale-up-immunity-against-covid-19.html (accessed on 21 October 2023).

- Wiysonge C.S., Ndwandwe D., Ryan J., Jaca A., Batouré O., Anya B.M., et al. Vaccine hesitancy in the era of COVID-19: could lessons from the past help in divining the future? Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2022;18:1–3. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1893062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Vaccine hesitancy: A growing challenge for immunization programmes. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/18-08-2015-vaccine-hesitancy-a-growing-challenge-for-immunization-programmes (accessed on 20 October 2023).

- Xe Currency Converter. Convert Iraqi Dinars to US Dollars: Xe Currency Converter. Available online: https://www.xe.com/currencyconverter/convert/?Amount=500000&From=IQD&To=USD (accessed on 26 November 2022).

- Yuan Y., Sun R., Zuo J., Chen X. A New Explanation for the Attitude-Behavior Inconsistency Based on the Contextualized Attitude. Behav Sci (basel) 2023;13:223. doi: 10.3390/bs13030223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author (Malik Sallam).