Abstract

The hallmarks of spondyloarthritis (SpA) are type 3 immunity-driven inflammation and new bone formation (NBF). Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) was found to be a key driver of the pathogenesis of SpA by amplifying type 3 immunity, yet MIF-interacting molecules and networks remain elusive. Herein, we identified hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha (HIF1A) as an interacting partner molecule of MIF that drives SpA pathologies, including inflammation and NBF. HIF1A expression was increased in the joint tissues and synovial fluid of SpA patients and curdlan-injected SKG (curdlan-SKG) mice compared to the respective controls. Under hypoxic conditions in which HIF1A was stabilized, human and mouse neutrophils exhibited substantially increased expression of MIF and IL-23, an upstream type 3 immunity-related cytokine. Similar to MIF, systemic overexpression of IL-23 induced SpA pathology in SKG mice, while the injection of a HIF1A-selective inhibitor (PX-478) into curdlan-SKG mice prevented or attenuated SpA pathology, as indicated by a marked reduction in the expression of MIF and IL-23. Furthermore, genetic deletion of MIF or HIF1A inhibition with PX-478 in IL-23-overexpressing SKG mice did not induce evident arthritis or NBF, despite the presence of psoriasis-like dermatitis and blepharitis. We also found that MIF- and IL-23-expressing neutrophils infiltrated areas of the NBF in curdlan-SKG mice. These neutrophils potentially increased chondrogenesis and cell proliferation via the upregulation of STAT3 in periosteal cells and ligamental cells during endochondral ossification. Together, these results provide supporting evidence for an MIF/HIF1A regulatory network, and inhibition of HIF1A may be a novel therapeutic approach for SpA by suppressing type 3 immunity-mediated inflammation and NBF.

Keywords: Endochondral ossification, Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha, Interleukin-23, Macrophage migration inhibitory factor, Neutrophil, Spondyloarthritis

Subject terms: Chronic inflammation, Translational immunology

Introduction

Type 3 immunity plays pivotal roles in inflammation and osteoimmunology. Inflammatory conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis, often result in detrimental bone erosion, a well-documented consequence of the disease. However, spondyloarthritis (SpA) presents a paradoxical twist, where inflammation is intimately linked to new bone formation (NBF), particularly at entheseal sites [1]. This enigma is rooted in the profound influence of type 3 immunity, with the interleukin (IL)-23/IL-17 axis assuming a pivotal role [2, 3]. The emergence of pharmacological interventions targeting IL-23 or IL-17 has proven effective in alleviating inflammation in a substantial proportion of SpA patients [4, 5].

Within the intricate landscape of immunopathology in SpA, macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) has emerged as an amplifier of inflammation mediated by type 3 immunity, as elucidated in our previous study [6]. We also found that inhibition of MIF decreased SpA pathology in curdlan-injected SKG (curdlan-SKG) mice, a well-established preclinical SpA model [6]. Interestingly, we pinpointed neutrophils as the primary culprits, as they secrete larger amounts of MIF than other immune cells in the inflamed tissues of SKG mice [6].

Untangling the mechanisms surrounding MIF-interacting molecules may further pave the way for the discovery of novel pathways closely associated with type 3 immunity. Additionally, the role of MIF-producing neutrophils in NBF has not been explored. The elucidation of these intricate mechanisms is essential, as it will bridge the gaps in our understanding of SpA pathogenesis and steer us toward innovative therapeutic strategies.

MIF is known not only as a secreted molecule but also as an intracellular signaling and regulatory molecule [7] that can physically interact with hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha (HIF1A). In this study, we demonstrated that HIF1A plays essential roles in augmenting MIF and IL-23 expression and secretion in neutrophils. These processes significantly fuel inflammation in SpA. Furthermore, we revealed that the coexpression of HIF1A and MIF in osteochondroprogenitor cells promoted chondrogenesis during NBF development through STAT3 activation. Blocking HIF1A with a selective inhibitor (PX-478) effectively suppressed both inflammation and NBF in SKG mice by mitigating type 3 immunity and chondrogenesis. Thus, we provide a novel landscape of MIF/HIF1A regulatory networks and offer the first evidence that inhibition of HIF1A may provide a novel therapeutic strategy for suppressing the two major features of SpA.

Results

HIF1A interacts with MIF in multiple tissues

Following our discovery of MIF as a critical driver of type 3 immunity that mediates SpA pathologies [6], we sought to identify MIF-interacting molecules that could play important roles in the pathogenesis of SpA. We first explored known and predicted physical protein‒protein interactions (PPIs) and identified 172 proteins capable of interacting with MIF (159 with experimental evidence) in humans (Supplemental Data 1). Considering the multiple tissues affected in patients with SpA (Fig. S1A), we next studied MIF-interacting partners in specific tissues, cells, and conditions that are well acknowledged to be associated with SpA, including arthritis (bone inflammation, connective tissue diseases, and musculoskeletal systemic diseases) [1], bone/bone marrow [8], musculoskeletal muscle [9], adipose tissues [10], small intestine [11], articular cartilage [12], chondrocytes [13], synovial macrophages [14], synovial membrane [15], cardiovascular system diseases [16], and obesity [17]. Intriguingly, only 3 proteins (HIF1A, SOD1, and COX8A) were identified as MIF-interacting proteins commonly shared among these SpA-related tissues, cells, and conditions (Fig. 1A and Supplemental Data 2). Among these 3 proteins, the expression of the HIF1A gene, but not that of SOD1 or COX8A, was increased in synovial fluid (SF) cells obtained from SpA patients compared to those from OA patients (Fig. S2A). We also confirmed that MIF physically interacted with HIF1A in human neutrophils isolated from peripheral blood by immunoprecipitation (Fig. S2B). This result prompted us to further understand the role and therapeutic potential of HIF1A in driving type 3 immune responses and bone pathology in SpA.

Fig. 1.

Identification of HIF1A as a shared protein that interacts with MIF to increase the secretion of MIF and IL-23. A Schematic image showing the number of protein‒protein interactions (PPIs) with MIF based on a variety of spondyloarthritis (SpA)-related conditions, cells, and tissues. HIF1A was identified as a shared protein that interacts with MIF in all conditions, cells, and tissues. B Numbers of PPIs with MIF and species-based conservation rates relative to humans are shown. Representative images of immunohistochemistry (IHC) showing the expression of HIF1A around areas of NBF in curdlan- or PBS (control)-treated SKG mice (C) or human spinal entheses from SpA or osteoarthritis (OA) patients (D). E Representative images of immunofluorescence staining showing the expression of HIF1A and MIF in synovial fluid (SF) cells (N, neutrophils; Ly, lymphocytes) isolated from patients with SpA or OA. F Representative images of immunocytochemistry (ICC) showing the expression of HIF1A in SF cells isolated from patients with SpA or OA. G Representative images of ICC showing the expression of HIF1A and MIF in bone marrow (BM) cells from curdlan-injected SKG (curdlan-SKG) or PBS-injected SKG (PBS-SKG) mice. Representative immunoblot images showing the expression of HIF1A (H) and densitometric analysis of HIF1A adjusted to β-actin expression (I) in wild-type (WT; Mif+/+) or MIF knockout (MIF KO; Mif−/−) neutrophils treated with or without curdlan (10 µg/ml for 60 min, n = 6 samples per group). J Concentrations of MIF secreted into the culture media from SKG neutrophils (2 million cells per well in a 96-well plate) cultured under normoxic (21% O2) or hypoxic (2% O2) conditions with or without curdlan (10 µg/ml for 18 h) (n = 8 samples per group). K Representative immunoblot images showing the expression of MIF in the lysates of neutrophils cultured under normoxic or hypoxic conditions with or without PX-478 and curdlan. L‒O Fold changes in the expression of inflammatory cytokines in WT and MIF KO neutrophils cultured under normoxic or hypoxic conditions for 3 or 18 h (n = 6 samples per group). P Representative images of ICC showing the expression of IL-23 p19 in BM cells from curdlan-SKG or PBS-SKG mice. Q Fold changes in the expression of inflammatory cytokines in neutrophils cultured under normoxic or hypoxic conditions and treated with curdlan for 18 h (n = 6 samples per group). R Concentrations of IL-23 p19 secreted into culture media from WT SKG neutrophils (2 million cells per well in a 96-well plate) cultured under normoxic or hypoxic conditions (n = 8 samples per group). Representative immunoblot images showing the expression of IL-23 p19 and HIF1A (S) and the densitometry values adjusted to that of β-actin (T) in WT or MIF-KO neutrophils cultured under normoxic or hypoxic conditions for 18 h (n = 6 samples per group). U Expression of the Il23a mRNA in WT SKG neutrophils treated with or without PX-478 under hypoxic conditions for 18 h. Scale bars, 100 µm (C, D, E, G, P) or 10 µm (F). The data shown in I, J, L‒O, Q, R, T are presented as the means ± SEMs. Relative data were log-transformed before statistical analyses. Statistical analyses were performed using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests followed by the two-stage linear step-up procedure of Benjamini, Krieger and Yekutieli post hoc tests (I, T); Friedman tests followed by the two-stage linear step-up procedure of Benjamini, Krieger, and Yekutieli post hoc tests (J); two-tailed paired t tests (L‒O, Q, U); or Mann‒Whitney U tests (R). *P (or q) < 0.05 and **P (or q) < 0.01

A species-based analysis revealed that mice harbor most of the MIF-interacting molecules identified in humans, including HIF1A (Fig. 1B and Table S2). This result indicates that mouse models of SpA, including SKG mice, are suitable for recapitulating the majority of MIF PPIs in humans. Using immunohistochemistry (IHC), we detected increased expression of HIF1A in the ankle tissues of curdlan-SKG mice and in human spinal entheseal tissues from SpA patients compared to those from PBS-SKG mice or OA patients (Fig. 1C, D), respectively, supporting a potential role for HIF1A in the pathogenesis of SpA.

MIF and HIF1A mutually increase the expression of each other in neutrophils

In the SKG mouse model of type 3 immunity-driven SpA, we recently reported increased MIF expression in neutrophils [6]. Considering the close association between MIF and HIF1A, we detected increased expression of both HIF1A and MIF in neutrophils isolated from the SF of SpA patients compared to those from OA patients, as determined using IF and IHC staining (Fig. 1E, F). Similarly, bone marrow (BM) cells expressing HIF1A and MIF were more abundant in curdlan-SKG mice than in PBS-SKG mice (Fig. 1G). Similarly, neutrophil depletion with an anti-Ly6G monoclonal antibody (mAb) in curdlan-SKG mice attenuated SpA features and decreased the expression of HIF1A and MIF in the ankle joints compared to those in mice treated with the isotype control IgG (Fig. S3).

Neutrophils were isolated from healthy (not curdlan-injected) wild-type (WT; Mif+/+) SKG mice or Mif knockout (Mif KO; Mif-/-) SKG mice and then treated with or without curdlan in vitro to test whether curdlan treatment directly increased HIF1A expression in MIF-expressing neutrophils. We observed increased expression of HIF1A in WT SKG neutrophils treated with curdlan compared to WT SKG neutrophils cultured without curdlan, but this increase was not evident in Mif KO SKG neutrophils (Fig. 1H, I), suggesting that MIF is essential for increasing the expression of HIF1A in neutrophils in response to curdlan. Next, we tested whether HIF1A increased the expression of MIF. Since a hypoxic environment stabilizes HIF1A in cells, WT SKG neutrophils were cultured under physiological hypoxic (2% O2) conditions [18]. Compared to the levels detected under normoxic conditions (21% O2), the secretion and expression of MIF were increased in neutrophils cultured under hypoxic conditions (Fig. 1J, K). Similarly, MIF expression was increased in human neutrophils isolated from the peripheral blood of SpA patients and cultured ex vivo under hypoxic conditions compared to those cultured under normoxic conditions (Fig. S4). Importantly, pharmacological inhibition of HIF1A with a selective inhibitor (PX-478) decreased the hypoxia-induced increase in MIF expression in neutrophils isolated from WT SKG mice (Fig. 1K). These results indicate that MIF and HIF1A mutually increase the expression of each other.

HIF1A increases the expression and secretion of IL-23 from neutrophils

Since inflammatory conditions create hypoxic environments in tissues [19–21] and neutrophils increase the expression of MIF and HIF1A under hypoxia, we next investigated the mechanism by which MIF/HIF1A-expressing neutrophils are pathogenic immune cells for SpA under inflammation-induced hypoxia. Enhanced MIF/HIF1A expression in hypoxic environments might also enhance the expression of other inflammatory cytokines in neutrophils. The mRNA expression of SpA-related inflammatory markers (Il1b, Il6, Il18, and Il23a) was significantly increased in WT SKG neutrophils cultured under physiological hypoxia than in those cultured under normoxia after 3 h of incubation, except for Tnfa (Fig. 1L). Interestingly, Mif KO SKG neutrophils did not show increased expression of any of these markers after 3 h of incubation (Fig. 1M). The expression of these markers was also tested after 18 h of incubation, and we found that Il23a expression was dramatically increased in WT SKG neutrophils, despite a milder increase or unchanged expression of other markers in both WT and Mif KO SKG neutrophils (Fig. 1N, O). BM cells isolated from curdlan-SKG mice exhibited increased numbers of cells expressing IL-23 p19 (Fig. 1P), and culturing neutrophils with curdlan under hypoxic conditions in vitro further increased Il23a expression (Fig. 1Q). The secretion of IL-23 p19 from neutrophils was also increased in response to hypoxia than under normoxic conditions (Fig. 1R).

Regarding the mechanism underlying the increased levels of IL-23 under hypoxic conditions, HIF1A has recently been reported to potentially bind to the promoter region of IL23 and to enhance IL-23 expression in macrophages [22]. Consistent with this report, we observed a significant increase in the expression of both HIF1A and IL-23 p19 in both SKG mice and human neutrophils under hypoxic conditions compared to normoxic conditions (Fig. 1S, T, and Fig. S4), and IL-23 p19 expression decreased in hypoxic neutrophils treated with the HIF1A inhibitor PX-478 (Fig. 1U). These results suggest that HIF1A may be a critical mediator of the increase in IL-23 expression in neutrophils under hypoxic conditions.

Pharmacological inhibition of HIF1A (PX-478) suppresses MIF and IL-23 expression and attenuates SpA-like pathologies

Since hypoxia-stabilized HIF1A intensified the expression and secretion of MIF and IL-23 from neutrophils, we next tested whether inhibition of HIF1A with PX-478 could suppress the expression of these cytokines and prevent or attenuate SpA pathology in curdlan-SKG mice. The pharmacological mechanisms by which PX-478 reduces HIF1A activity include the inhibition of HIF1A translation, reduction of HIF1A mRNA expression, and inhibition of HIF1A ubiquitination [23]. First, we tested the prophylactic effect of PX-478 by orally administering PX-478 (10 mg/kg, every 2 to 3 days; three times/week) beginning one week after curdlan injection and continued its administration for 3 weeks (Fig. 2A). Compared with control curdlan-SKG mice, curdlan-SKG mice treated with PX-478 exhibited a markedly reduced severity of arthritis, psoriasis-like dermatitis, and blepharitis, with smaller spleens and popliteal lymph nodes (PLNs) at 4 weeks postcurdlan injection (Fig. 2B–E). Interestingly, despite the suspension of PX-478 administration, the decrease in inflammation, as evidenced by decreased histological scores and gene expression of inflammatory mediators in the joints or tail vertebrae, was sustained until the experimental endpoint (Fig. 2F–K). This result suggested that PX-478 has a long-lasting effect on suppressing SpA-like pathologies when administered around the disease onset of SpA. Furthermore, PX-478 prevented NBF in the distal tibia of curdlan-SKG mice, as indicated by decreased expression of endochondral ossification (ECO)-related markers assessed using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, Safranin O/fast green (SO&FG) staining, and qPCR analysis (Fig. 2L–N).

Fig. 2.

Prophylactic effects of a HIF1A inhibitor (PX-478) on SpA pathology. A Schematic image of the effects of PX-478 or PBS treatment on curdlan-injected SKG (curdlan-SKG) mice. B Clinical scores of curdlan-SKG mice treated with PBS or PX-478 (10 mg/kg, oral gavage, three times/week, from 1 to 4 weeks postcurdlan injection; n = 6 mice per group). C–G Representative images of clinical features (C, D arthritis, dermatitis, and blepharitis 4 weeks postcurdlan treatment; F, G; arthritis, dermatitis, and blepharitis 8 weeks postcurdlan treatment; E spleen and popliteal lymph nodes 4 weeks postcurdlan or PBS treatment). Representative histological images (H&E staining; H, I) and scores (J; n = 6 mice per group) of the ankle joints and tail vertebrae of curdlan-SKG mice treated with PBS or PX-478 at 8 weeks after the curdlan injection. K Gene expression of inflammatory markers in ankle soft tissues isolated from SKG mice treated with PBS or PX-478 at 8 weeks after the curdlan injection (n = 5 mice per group). Representative histological images showing new bone formation [NBF, H&E (L) and safranin O/fast green (M) staining] in the ankle joints of curdlan-SKG mice treated with PBS or PX-478 at 8 weeks after the curdlan injection. N Gene expression of endochondral ossification (ECO) markers in ankle soft tissues isolated from curdlan-SKG mice treated with PBS or PX-478 at 8 weeks after the curdlan injection (n = 5 mice per group). Scale bars, 100 μm (H, I, L, M). The data shown in B, J, K, N are presented as the means ± SEMs. Relative data were log-transformed before statistical analyses. Statistical analyses were performed using Kruskal‒Wallis tests followed by the two-stage linear step-up procedure of Benjamini, Krieger and Yekutieli post hoc tests (B), Mann‒Whitney U-tests (J), or two-tailed paired t-tests (K, N). *P (or q) < 0.05 and **P (or q) < 0.01

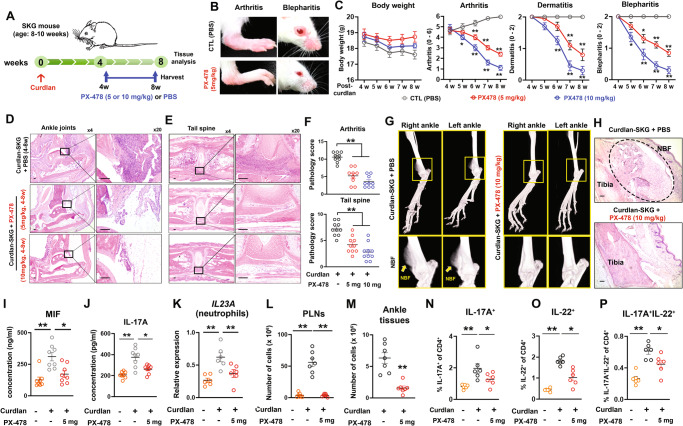

For clinical relevance, we tested the therapeutic effect of PX-478 by administering PX-478 (5 or 10 mg/kg, every 2 to 3 days; three times/week) from 4 to 8 weeks postcurdlan injection (Fig. 3A). PX-478 treatment (both 5 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg) reduced the severity of arthritis, psoriasis-like dermatitis, and blepharitis compared to that in control (PBS)-injected SKG mice after the curdlan injection (Fig. 3B, C). Histology and histopathology scores for arthritis and tail vertebrae also revealed a decreased severity of inflammation (Fig. 3D–F). Furthermore, microCT and histological images showed no evidence of NBF in curdlan-SKG mice treated with PX-478, while curdlan-SKG mice treated with PBS exhibited remarkable NBF in the distal tibia (Fig. 3G, H).

Fig. 3.

Inhibition of HIF1A with PX-478 attenuates SpA pathology. A Schematic image of the effects of PX-478 (5 or 10 mg/kg, oral gavage, three times per week, from 4 to 8 weeks after the curdlan injection) or PBS (control; CTL) administration on curdlan-SKG mice. B Representative images of arthritis and blepharitis in curdlan-SKG mice treated with PBS or PX-478 (5 mg/kg) at 8 weeks postcurdlan injection. C Weekly clinical scores of the curdlan-SKG mice treated with PX-478 (5 or 10 mg/kg) or PBS for 8 weeks (n = 10 mice per group). D, E Histological images showing representative ankle joints and tail vertebrae (H&E staining) of curdlan-SKG mice treated with PX-478 (5 or 10 mg/kg) or PBS at 8 weeks after the curdlan injection. F Pathological scores for inflammation in the joints (arthritis) and tail vertebrae of curdlan-SKG mice treated with PX-478 (5 or 10 mg/kg) or PBS at 8 weeks after the curdlan injection (n = 9 or 10 mice per group). G, H Representative microCT and histological (H&E staining) images showing the ankle joints of curdlan-SKG mice treated with PX-478 (10 mg/kg, 4 to 8 weeks after administration) or PBS at 8 weeks after the curdlan injection. I, J Concentrations of MIF and IL-17A in serum isolated from SKG mice injected with or without PX-478 (5 mg/kg) after the curdlan injection (n = 8 mice per group). K Expression of the Il23a mRNA in neutrophils isolated from PBS- or curdlan-injected SKG mice treated with or without PX-478 at 8 weeks after the curdlan injection (n = 6 mice per group). L, M Total cell numbers in the popliteal lymph nodes (PLNs) or ankle soft tissues of curdlan-SKG mice treated with or without PX-478 (n = 7 mice per group). N–P Frequencies of CD4+ T cells expressing IL-17A, IL-22, and GM-CSF in PLNs isolated from PBS-SKG or curdlan-SKG mice treated with or without PX-478 at 8 weeks after the curdlan injection (n = 6 mice per group). Scale bars, 100 μm (D, E, H). The data shown in C, F, I–P are presented as the means ± SEMs. Relative data were log-transformed before statistical analyses. Statistical analyses were performed using the Kruskal‒Wallis test followed by the two-stage linear step-up procedure of Benjamini, Krieger and Yekutieli post hoc tests (C, F, I, J, L); Brown–Forsythe and Welch’s ANOVA tests followed by the two-stage linear step-up procedure of Benjamini, Krieger and Yekutieli post hoc tests (K, N–P); and Mann‒Whitney U-tests (M). *P (or q) < 0.05 and **P (or q) < 0.01

Since we found that HIF1A was a pivotal mediator of MIF and IL-23 secretion, we evaluated the expression of MIF, IL-23, and other type 3 immunity-related cytokines in curdlan-SKG mice treated with PX-478. Compared to PBS-injected curdlan-SKG mice, those treated with PX-478 had decreased serum MIF and IL-17A concentrations (Fig. 3I, J). Although IL-23 was not detectable in the serum of either treatment group using ELISA, IL23a mRNA expression in neutrophils isolated from ankle soft tissues was lower in PX-478-treated mice than in PBS-treated curdlan-SKG mice (Fig. 3K). The total number of CD4+ T cells isolated from the PLN and ankle soft tissue and the intracellular expression of IL-17A and IL-22 in the PLNs were substantially lower in PX-478-treated mice than in PBS-treated curdlan-SKG mice (Fig. 3L–P). These results indicate that HIF1A facilitates type 3 immunity-mediated inflammation and that blocking HIF1A activity with PX-478 is prophylactically and therapeutically effective at suppressing SpA pathology in SKG mice, at least in part by decreasing the expression of MIF and IL-23.

Overexpression of IL-23 is sufficient to induce type 3 immunity and SpA pathologies in SKG mice

Since MIF and HIF1A appear to be key molecules driving IL-23 production, we next sought to confirm the pathological role of IL-23 in SKG mice. SpA-induced pathology in SKG mice has already been reported to depend on IL-23 [24–26], as curdlan-injected SKG mice treated with anti-IL-23 antibodies showed a decreased severity of inflammation. To the best of our knowledge, no IL-23 studies have demonstrated the direct contribution of IL-23 to the induction of SpA pathology in SKG mice.

In this context, we generated IL-23-overexpressing SKG mice via hydrodynamic (HDD) injection of an IL-23 plasmid (PLM) into SKG mice (Fig. 4A). Overexpression of IL23 p19 was confirmed by IHC of livers isolated from mice injected with the control plasmid or the IL23 plasmid 4 weeks after plasmid injection (Fig. 4B). Similar to the findings in MIF-overexpressing SKG mice [6], we observed evident SpA features in SKG mice injected with IL-23 PLM (Fig. 4C–F). This finding confirmed that IL-23 overexpression alone (without curdlan injection) was adequate to induce SpA pathology in SKG mice. Histology and histopathological scoring revealed pronounced inflammation in the joint and tail vertebrae (Fig. 4G, H). Psoriasis-like dermatitis and blepharitis developed rapidly after the PLM injection, but the severity of the inflammation gradually decreased at 5 to 6 weeks after the IL-23 PLM injection (Fig. 4F). This decrease was likely due to the gradual reduction in the release of IL-23 from the liver over time, resulting in a subsequent decrease in the serum concentration of IL-17A (Fig. 4I). On the other hand, arthritis progressed slowly but continuously until 8 weeks (Fig. 4F). We also observed that the serum concentration of MIF peaked later than that of IL-17A after the IL-23 PLM injection (Fig. 4I). The temporal profile of psoriasis-like dermatitis corresponds to an increase in IL-17A levels, while that of arthritis correlates with MIF. This result suggests a potential difference in the clinical impacts of these two cytokines on SKG mice. Additionally, MIF expression appears to be inducible by IL-23 overexpression and is likely downstream of IL-23, consistent with a published report [27]. Furthermore, HIF1A expression was increased in the ankle joints of SKG mice injected with the IL-23 PLM (Fig. S5), suggesting that HIF1A expression is also induced by IL-23 overexpression.

Fig. 4.

IL-23-overexpressing SKG mice exhibit SpA pathology with enhanced type 3 immunity. A Schematic image of IL-23 plasmid (PLM) or CTL PLM administration to SKG mice. B Representative images of IHC staining showing the expression of IL-23 p19 in livers isolated from CTL PLM-injected mice or IL-23 PLM-injected SKG mice at 4 weeks after the PLM injection. C–E Representative images showing clinical symptoms (blepharitis, psoriasis-like dermatitis, and arthritis) in CTL PLM-injected or IL-23 PLM-injected SKG mice at 2, 5, and 8 weeks after the PLM injection. F Clinical scores of SKG mice injected with the CTL PLM or IL-23 PLM (n = 10 mice per group). G, H Representative histological images [hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining; G)] and scores (H; n = 10 mice per group) for ankle joints and tail vertebrae of SKG mice injected with the CTL PLM or IL-23 PLM at 8 weeks after the PLM injection. I Serum concentrations of IL-23 and IL-17A in SKG mice injected with the CTL PLM or IL-23 PLM over 8 weeks after the PLM injection (n = 5 mice per group). J, K Representative microCT images showing ankle joints and tail vertebrae in SKG mice injected with the CTL PLM or IL-23 PLM at 8 weeks after the PLM injection (the yellow arrow indicates NBF). L, M Representative histological images showing new bone formation [NBF, safranin O/fast green (SO/FG; L) staining] and SOX9 expression (IHC; M) in the ankle joints of SKG mice injected with the CTL PLM or IL-23 PLM at 8 weeks after the PLM injection. N–S Frequencies of CD4+ T cells expressing IL-17A, IL-22, IFN-γ, and GM-CSF in popliteal lymph nodes (PLNs) isolated from SKG mice at 8 weeks after the CTL PLM or IL-23 PLM injection (n = 5 mice per group). T Schematic image of IL-23 PLM or CTL PLM administration to Mif knockout (MIF KO; Mif−/−) SKG mice. U Clinical scores of MIF KO SKG mice injected with the CTL PLM or IL-23 PLM (n = 10 mice per group). V Representative images of the clinical symptoms of IL-23 PLM-injected MIF KO SKG mice at 8 weeks after the PLM injection. W, X Representative histological images (H&E staining; W) and scores (X; n = 10 mice per group) for ankle joints and tail vertebrae in MIF-KO SKG mice injected with the CTL PLM or IL-23 PLM at 8 weeks after the PLM injection. Y Representative microCT images showing ankle joints and tail vertebrae in MIF KO SKG mice injected with the CTL PLM or IL-23 PLM at 8 weeks after the PLM injection. Z Frequencies of CD4+ T cells expressing IL-17A, IL-22, IFN-γ, and GM-CSF in PLNs isolated from MIF KO SKG mice at 8 weeks after the CTL PLM or IL-23 PLM injection (n = 5 mice per group). Scale bars, 100 μm (B, G, L, M, W). The data shown in F, H, I, O, Q, S, U, X, Z are presented as the means ± SEMs. Relative data were log-transformed before statistical analyses. Statistical analyses were performed using Kruskal‒Wallis tests followed by the two-stage linear step-up procedure of Benjamini, Krieger and Yekutieli post hoc tests (F, I, U), Mann‒Whitney U-tests (H, X), or two-tailed paired t tests (O, Q, S, Z). *P (or q) < 0.05 and **P (or q) < 0.01

MicroCT images clearly showed NBF in the distal tibia of SKG mice injected with the IL-23 PLM (Fig. 4J), similar to what was observed in curdlan-SKG mice [6]. Notably, we also observed bridged tail vertebrae (ankylosis) in IL-23-overexpressing SKG mice (Fig. 4K), a feature not observed in curdlan-SKG mice at 8 weeks postcurdlan injection [6, 28]. This finding revealed that the overexpression of IL-23 is more potent at inducing NBF than is curdlan treatment in SKG mice. Furthermore, we noted that NBF occurred through ECO with substantial expression of proteoglycans and SOX9, as assessed by SO&FG staining and IHC, respectively (Fig. 4L, M).

We isolated CD4+ T cells from the popliteal lymph nodes (PLNs) of SKG mice injected with the IL-23 PLM or CTL PLM to assess the expression of type 3 immunity-related cytokines induced by IL-23 in vivo. We observed that the number of CD4+ T cells with intracellular expression of IL-17A and IL-22 was greater in the PLNs of SKG mice injected with the IL-23 PLM than in those of SKG mice injected with the CTL PLM, whereas no significant difference in the number of CD4+ T cells expressing IFN-γ was observed (Fig. 4N–Q), akin to that in SKG mice injected with curdlan or the MIF PLM [6]. Although the percentage of CD4+ T cells expressing granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) was not significantly increased, the percentage of CD4+ T cells expressing both IL-17A and GM-CSF, which are considered pathogenic in SpA [29], was increased in the PLNs of SKG mice injected with IL-23 PLM (Fig. 4R, S). These results suggest that IL-23 overexpression is sufficient to induce the clinical features and immunopathology of SpA in SKG mice, similar to other SpA mouse models [28, 30].

Deletion of MIF or inhibition of HIF1A suppresses the development of arthritis and NBF in IL-23-overexpressing SKG mice

Since our data suggest that MIF is, at least in part, a downstream cytokine induced by IL-23 signaling, we injected the IL-23 PLM into Mif KO SKG mice to test the role of IL-23 in the absence of MIF (Fig. 4T). Similar to the results from WT SKG mice, IL-23 overexpression caused comparable psoriasis-like dermatitis and blepharitis in Mif KO SKG mice (Fig. 4U, V). However, unlike in WT SKG mice, arthritis and spinal inflammation were not evident in Mif KO SKG mice injected with the IL-23 PLM (Fig. 4U–X). Moreover, microCT images of the ankle joint and tail vertebrae did not show NBF in Mif KO SKG mice injected with the IL-23 PLM (Fig. 4Y). Similar to the findings in Mif KO SKG mice, inhibition of HIF1A in IL-23-overexpressing SKG mice treated with PX-478 did not result in evident arthritis despite the presence of psoriasis-like dermatitis and blepharitis at 5 weeks post-IL-23 PLM injection (Fig. S6). These results suggest that while MIF and HIF1A may not be the dominant cytokines controlling dermatitis and blepharitis under continuous IL-23 stimulation, they may nonetheless be indispensable in causing arthritis and NBF in IL-23-overexpressing SKG mice.

Despite the lack of discernible arthritis, the intracellular expression of IL-17A, IFN-γ, IL-22, and GM-CSF was increased in CD4+ T cells from PLNs isolated from Mif KO SKG mice injected with the IL-23 PLM compared to their expression in cells from Mif KO SKG mice injected with the CTL PLM (Fig. 4Z), likely because PLNs drain skin tissue in addition to joint tissues.

NBF develops from periosteal and ligamentous areas through ECO in SKG mice

SpA patients develop NBF through the process of ECO, by which mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) transform into a cartilage intermediate, and the cartilage is subsequently replaced by bone [13, 31]. Despite extensive research [32], the role of MIF during ECO has not been well defined.

We observed NBF in the distal tibia of both curdlan-SKG mice and IL-23-overexpressing SKG mice but only found ankylosis in the tail vertebrae of IL-23-overexpressing SKG mice. We first tracked NBF in curdlan-SKG mice over 8 weeks after curdlan injection to identify the source of NBF (Fig. S7A, B). Through biweekly observations with histopathological assessments, we found that NBF developed from periosteal areas in the distal tibia and tibia-talus ligament (Fig. S7C–F). Indeed, periosteal and ligamentous/tendon areas are known to accommodate periosteal cells (PCs) and tendon stem/progenitor cells, respectively, and these cells possess MSC-like characteristics and are capable of differentiating into chondrocytes, osteoblasts, and adipocytes, depending on the specific microenvironment [33–35]. Specifically, we found that inflammatory cells began to infiltrate the periosteal area or ligament approximately 2 to 3 weeks after the curdlan injection, and chondrocytes began to form, followed by hypertrophic changes at approximately 4 to 6 weeks after the curdlan injection. Finally, the ossification process started at approximately 7 to 8 weeks postcurdlan injection (Fig. S7D, F). Increased gene and protein expression of ECO-related markers, such as SOX9, COL2A1, proteoglycans, FGF18, and RUNX2, further confirmed that NBF in curdlan-SKG mice developed through ECO (Fig. S7G–J), similar to that in SpA patients.

MIF increases the levels of chondrogenesis markers in PCs and ligamental cells

We found that neutrophils, along with those abundantly expressing IL-23, infiltrated the area of NBF in SKG mice, especially during cartilage formation (Fig. 5A–C). Since chondrogenesis during ECO is known to occur under hypoxic conditions [36], we hypothesized that the presence of MIF- and IL-23-secreting neutrophils in relatively hypoxic NBF areas might promote chondrogenesis.

Fig. 5.

Exogenous MIF stimulation enhances chondrogenesis in vitro and in vivo. A Representative image of new bone formation (NBF) detected with safranin O/fast green (SO/FG) staining in the distal tibia of curdlan-treated SKG (curdlan-SKG) mice. B Histological images of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining showing infiltrated neutrophils in the area of NBF of curdlan-SKG mice. C Representative image of IF staining showing the expression of Ly6G and IL-23 around the area of NBF in curdlan-SKG mice. D Schematic image of the isolation and cell culture of tibial periosteal cells (PCs) from SKG mice. E Representative micrographs showing PCs originating from the tibia over 15 days (the lower layer shows negative controls where PCs were removed from the bone surface before cell culture). F, G Gene expression of endochondral ossification (ECO) markers in PCs treated with recombinant mouse MIF (rmMIF; 0, 10, 50 and 100 ng/ml) (n = 4 samples per group). Representative immunoblot images showing the expression of SOX9 and RUNX2 (H) and densitometric analysis adjusted to the β-actin level (I) in PCs treated with or without rmMIF for 24 h (n = 4 samples per group). J Representative images of IF staining showing COL2A1 expression in PCs cultured in chondrogenic differentiation (ChD) media with or without rmMIF (50 ng/ml) for 12 days. K, L Representative immunoblot images showing the expression of SOX9, FGF18, and RUNX2 in SKG tibia-talus tenocytes treated with or without rmMIF for 24 h (K), and densitometry values adjusted to that of β-actin (L; n = 4 samples per group). M Representative images of IHC staining showing the expression of SOX9 in the periosteum of SKG mice injected with the MIF plasmid (MIF PLM; 5 µg/mouse). The arrows show cells positive for SOX9. N Representative images of IHC staining showing the expression of SOX9 in the entheses of control PLM- or MIF PLM-injected SKG mice. The arrow shows cells positive for SOX9. O Representative images of SO/FG staining showing the expression of proteoglycans in the entheses of SKG mice injected with the control PLM or MIF PLM. Scale bars, 100 µm [A, B (left and middle panels), E, J, and M to O] or 10 µm [B (right panel) and C]. The data shown in F, G, I, L are presented as the means ± SEMs. Relative data were log-transformed before statistical analyses. Statistical analyses were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests with Geisser–Greenhouse corrections followed by the two-stage linear step-up procedure of Benjamini, Krieger and Yekutieli post hoc tests (F, G) or two-tailed unpaired t-tests (I, L; n = 4 samples per group). *P (q) < 0.05 and **P (q) < 0.01. NS not significant

We first sought to define the specific effects of MIF on PCs during ECO. PCs were isolated from the tibias of healthy WT SKG mice, cultured for 2 weeks, and treated with or without recombinant mouse MIF (rmMIF; 0, 10, 50, or 100 ng/ml) for 24 h (Fig. 5D, E). A negative control was generated in which the surface of the tibia was scraped to remove PCs via treatment with collagenase D prior to culture to exclude the potential contamination of other cells in the culture media [33], and no cell growth or proliferation was observed (Fig. 5E). This result indicated that the proliferating cells originated from the periosteum of the isolated tibia. We stained PCs for GDF5, a marker of progenitor cells [37], to confirm the cell phenotype and observed that most of the cells expressed GDF5 (Fig. S8A, B). Similarly, the periosteal and enthesis areas in the distal tibia and tail vertebrae of SKG mice had abundant GDF5-positive cells (Fig. S8C, D).

We observed increased gene or protein expression of chondrogenesis (Sox9 and Sox6) and cartilage extracellular matrix (Col2a1) markers in PCs treated with rmMIF, while the expression of osteogenesis (Runx2) and ossification (Bmp2, Alpl, and Bglap) markers was either unchanged or decreased in response to rmMIF (Fig. 5F–I). PCs were cultured in chondrogenic differentiation (ChD) media supplemented with or without rmMIF for 12 days to further confirm the effect of MIF on chondrogenesis. We observed increased intracellular expression of the COL2A1 protein in PCs treated with rmMIF (Fig. 5J). The increased expression of chondrogenesis markers was not specific to SKG mice, as we also observed MIF-induced expression of SOX9 in PCs isolated from healthy BALB/c mice (Fig. S9). Similarly, tibia-talus ligamental cells expressing scleraxis (SCX; Fig. S10), a marker of tenocytes and ligamentocytes [38], exhibited increased expression of SOX9 in response to rmMIF, while no evident differences in the expression of RUNX2 and FGF18 were observed (Fig. 5K, L).

Consistent with these in vitro findings, MIF-overexpressing SKG mice injected with the MIF PLM exhibited ECO with increased expression of SOX9 and proteoglycans in the periosteum and entheseal areas, as assessed using IHC and SO&FG staining (Fig. 5M–O). Cells were isolated from the spine (spinal process and facet joints) of SpA patients or OA patients and treated with or without recombinant human (rh) MIF to determine whether these findings are applicable to human samples. Similar to findings in mice, human spinal bone cells isolated from SpA patients, but not OA patients, showed increased in expression of the SOX9 mRNA and protein in response to rhMIF, with a maximum effect observed at 50 ng/ml. (Fig. S11). These results revealed that exogenous MIF stimulation increases the expression of SOX9 and cartilage ECM markers in PCs and ligaments, leading to the acceleration of chondrogenesis during ECO in both SKG mice and SpA patients.

IL-23 increases chondrogenesis marker expression in PCs in a MIF-dependent manner

Although the role of IL-23 in inflammation in the pathogenesis of SpA has been investigated [39–41], its contribution to NBF has been poorly studied or defined. Given that IL-23 overexpression resulted in more pronounced NBF than curdlan treatment (Fig. 4K) and that neutrophils expressing IL-23 infiltrated inflamed hypoxic joint tissues of SKG mice (Fig. 5C), in addition to the absence of ECO observed when neutrophils were depleted with an anti-Ly6G mAb (Fig. S12) [6], we hypothesized that IL-23 might also play a role in ECO. We observed that rmIL-23 stimulation increased the expression of the Sox9, Col2a1, Acan, and Bmp2 mRNAs and the expression of the SOX9 protein in PCs (Fig. 6A–C). In contrast, IL-17A, a major downstream cytokine of IL-23, did not increase the expression of any of these genes. Sox9 expression was even lower in PCs stimulated with IL-17A (Fig. 6A), which is consistent with a previous report showing a protective role of IL-17A in periosteal NBF in a K/BxN serum-transfer arthritis mouse model [42]. Notably, the IL-23-driven expression of SOX9 was not observed in Mif KO PCs (Fig. 6D), suggesting that MIF is crucial for SOX9 expression in response to IL-23. Additionally, compared with Mif KO PCs, WT PCs cultured in ChD media showed higher expression of the SOX9 mRNA and protein at 3, 6, and 12 days (Fig. 6E–G). The expression of Col2a1 and Acan, which are cartilage ECM markers, was also higher in WT PCs than in Mif KO PCs at 3 days and 12 days, respectively (Fig. 6E, G).

Fig. 6.

IL-23 promotes chondrogenesis in periosteal cells (PCs) in the presence of MIF. A Gene expression of endochondral ossification (ECO) markers in PCs treated with recombinant mouse (rm) IL-17A or IL-23 (0, 10, 50, 100 ng/ml) for 24 h (n = 4 samples per group). B, C Representative immunoblot image showing the expression of SOX9 in wild-type (WT; Mif+/+, B) PCs treated with rmIL-23 for 24 h (B), and densitometry value adjusted to that of GAPDH (C; n = 4 samples per group). D Representative immunoblot image showing the expression of SOX9 in MIF knockout (MIF KO; Mif−/−, D) PCs treated with rmIL-23 for 24 h. E–J Gene expression of ECO markers (Sox9, Col2a1, and Acan) and IL-23-binding receptors (Il23r and Il12rb1) in PCs cultured with rmMIF (50 ng/ml) and rmIL-23 (100 ng/ml) in chondrogenic differentiation (ChD) media under hypoxic conditions (2% O2) for 3 (E and H), 6 (F and I), and 12 (G, J) days (n = 3 samples per group). K Expression of the Sox9 mRNA in PCs treated with or without rmIL-23 in the presence or absence of anti-IL-23 p19 antibodies (n = 3 samples per group). L Representative immunoblot images showing SOX9 protein expression in PCs cultured with rmMIF (50 ng/ml) and rmIL-23 (100 ng/ml) in ChD media under hypoxic conditions (2% O2) for 3, 6, and 12 days. M Densitometry analysis of SOX9 protein expression in WT PCs cultured with or without rmMIF and rmIL-23 in ChD media under hypoxic conditions for 3 days (n = 3 samples per group). The data shown in A, C, E, K, M are presented as the means ± SEMs. Relative data were log-transformed before statistical analyses. Statistical analyses were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Geisser–Greenhouse corrections followed by the two-stage linear step-up procedure of Benjamini, Krieger and Yekutieli post hoc tests (A, K, M) or two-way ANOVA tests with Geisser–Greenhouse corrections (E–J). *P (q) < 0.05 and **P (q) < 0.01

We next aimed to exclude the possibility of quantitative differences in the expression of IL-23-binding receptors in Mif KO mice, and detected no differences in Il23r or Il12rb1 gene expression between WT and Mif KO PCs cultured in ChD media (Fig. 6H–J), suggesting that the decrease in Sox9 expression in Mif KO mice was not due to quantitative differences in the expression of these receptors. The IL-23-mediated increase in Sox9 gene expression in WT PCs on Day 3 was ameliorated by the anti-IL-23 p19 neutralizing mAb (Fig. 6K). The increased expression of SOX9 was also confirmed by protein expression assessed through immunoblotting (Fig. 6L, M). Taken together, these results suggest that IL-23 stimulation increases the expression of chondrogenesis markers in PCs in the presence of MIF.

The coexistence of HIF1A with MIF increases chondrogenesis via STAT3 in response to MIF and IL-23

Having established the importance of MIF, we next studied the role of HIF1A in ECO. We observed that HIF1A was coexpressed with MIF and SOX9 in chondrocytes at the NBF site in the distal tibia of SKG mice, as assessed using IF staining (Fig. 7A–D). We also confirmed the same results in PCs cultured in ChD media for 12 days (Fig. S13A) or in PCs stimulated with rmMIF (Fig. S13B) by performing an immunoprecipitation assay. Blocking the intracellular expression of HIF1A with PX-478 decreased SOX9 expression in PCs treated with or without rmIL-23 (Fig. 7E, F). In addition, the administration of PX-478 to SKG mice 6 to 8 weeks after the curdlan injection suppressed cartilage formation at the edge of NBF (Fig. S14), further suggesting that the intracellular expression of HIF1A is a critical mediator of chondrogenesis and cartilage formation during NBF in vivo.

Fig. 7.

MIF and HIF1A increase chondrogenesis and cell proliferation through the activation of STAT3. A Representative image of safranin O/fast green (SO/FG) staining showing new bone formation (NBF) through endochondral ossification (ECO) in the distal tibia of curdlan-SKG mice. Boxes indicate the chondrocyte area (area 1) and nonchondrocyte area (area 2) of NBF. B, C Representative images of immunofluorescence staining showing the expression of MIF and HIF1A around the chondrocyte or nonchondrocyte areas of NBF. D Representative image of IHC staining showing the expression of SOX9 around the chondrocyte or nonchondrocyte areas of NBF. Representative immunoblot images showing the expression of SOX9 and HIF1A in WT PCs stimulated with IL-23 (100 ng/ml) with or without PX-478 (5 µM) treatment for 96 h (E), and densitometry values (F) adjusted to the expression of β-actin (n = 4 samples per group). G In silico analysis identifying transcription factors (TFs) that target HIF1A (red dots indicate TFs previously identified in SpA GWASs). H Representative immunoblot images showing the expression of phospho-STAT3 (p-STAT3) and STAT3 in spinal bone-derived cells isolated from patients with osteoarthritis (OA) or spondyloarthritis (SpA (n = 5 samples per group). I Expression of the STAT3 mRNA in spinal bone-derived cells isolated from patients with OA or SpA (n = 5 samples per group). J Representative images of IHC staining showing STAT3-positive spinal bone tissues from patients with OA or SpA. K Representative images of H&E staining and IHC staining for p-STAT3 in curdlan-SKG mice. Representative immunoblot images showing the expression of p-STAT3, STAT3, C-MYC and PARP p85 in WT PCs treated with or without rmMIF (50 ng/ml) under normoxic (21% O2) conditions for 24 h (L), and densitometric analysis (M) adjusted to the GAPDH levels (n = 4 samples per group). N Representative immunoblot images showing the expression of p-STAT3, STAT3, and SOX9 in wild-type WT PCs treated with or without rmMIF (50 ng/ml) in the presence of a control (CTL) siRNA or STAT3 siRNA under normoxic (21% O2) conditions for 48 h. O Representative immunoblot images showing the expression of p-STAT3 and STAT3 in wild-type WT PCs treated with or without rmMIF (50 ng/ml) under normoxic (21% O2) or hypoxic (2% O2) conditions for 96 h. P Representative immunoblot images showing the expression of SOX9 and HIF1A in WT PCs treated with or without rmMIF (50 ng/ml) in the presence of the CTL siRNA or STAT3 siRNA under hypoxic (2% O2) conditions for 96 h. Scale bars, 100 µm [A, B, C (except for the right panel; 10 µm)], D, J, K]. The data shown in F, I, M are presented as the means ± SEMs. Relative data were log-transformed before statistical analyses. Statistical analyses were performed using two-way ANOVA with Geisser–Greenhouse corrections followed by the two-stage linear step-up procedure of Benjamini, Krieger and Yekutieli post hoc tests (F) or two-tailed paired t tests (I, M). *P (q) < 0.05 and **P (q) < 0.01

As we found that HIF1A facilitates chondrogenesis in PCs, we further sought to identify an upstream factor that regulates HIF1A during this process. In our search for transcription factors (TFs) that upregulate HIF1A, we exploited an in silico analysis [Catrin Ver. 1 (http://ophid.utoronto.ca/catrin)], which identified 15 TFs targeting HIF1A (Fig. 7G and Supplemental Data 3), excluding the HIF1A-HIF1A interaction. Intriguingly, among these TFs, four (RELA, STAT3, NFKB, and ZNP36) have been reported by GWASs in SpA-related conditions, such as ankylosing spondylitis (AS) and Crohn’s disease (CD) [43, 44], suggesting their potential relevance to SpA. Among these four TFs, we focused on STAT3 as a potential upstream promoter of HIF1A expression in PCs, given that MIF and IL-23 are known to mediate STAT3-associated signaling pathways [45, 46] and that STAT3 is required for proliferation and anabolism in chondrocytes [47]. Additionally, a recent study showed that inhibition of STAT3 phosphorylation (p-STAT3) attenuated NBF in an AS mouse model [48]. Indeed, the expression of both the STAT3 mRNA and protein were increased in spinal bone-derived cells from SpA patients compared to those from OA patients (Fig. 7H–J). Similarly, we observed p-STAT3-positive cells around areas of NBF in curdlan-SKG mice (Fig. 7K). The expression of p-STAT3, STAT3 and C-MYC, but not the cellular apoptosis marker PARP p85, was also higher in tibia-talus ligamental cells treated with rmMIF than in those treated with PBS (Fig. 7L, M). Knockdown of STAT3 expression with an siRNA decreased the rmMIF-induced increase in SOX9 expression in PCs compared to that in PCs treated with the control siRNA (Fig. 7N). Moreover, an MIF-induced increase in p-STAT3 expression was observed in PCs under hypoxic conditions (Fig. 7O), whereas downregulation of STAT3 decreased SOX9 expression (Fig. 7P). Overall, these results suggest that MIF and IL-23 produced by neutrophils under hypoxia activate STAT3 in progenitor cells such as PCs, leading to increased chondrogenesis and cell proliferation through the upregulation of MIF and HIF1A (Fig. 8). Indeed, SKG-derived PCs cultured with hypoxia-incubated neutrophil-conditioned media exhibited increased Sox9 expression (Table S4), further suggesting that hypoxia-activated neutrophils contribute to the development of NBF through the upregulation of chondrogenesis.

Fig. 8.

Potential mechanisms of HIF1A-driven inflammation and new bone formation (NBF) in individuals with SpA. In low-oxygen areas of inflamed tissues, neutrophils increase the production of HIF1A, MIF, and IL-23. The MIF and IL-23 proteins trigger a type 3 immune response that boosts inflammation and causes psoriasis. In joint tissues, MIF and IL-23 increase the expression of HIF1A. Furthermore, MIF and IL-23 secreted from neutrophils also prompt the transformation of certain cell types, including mesenchymal stromal progeny, such as periosteal and tenocyte/ligamental cells, into chondrocytes. This process is mediated by STAT3 and involves increased expression of HIF1A. Therefore, inhibiting HIF1A with a pharmacological compound, such as PX-478, has the potential to reduce both inflammation and NBF in patients with SpA

Discussion

We found that HIF1A is a pivotal molecule that enhances type 3 immunity and promotes chondrogenesis, facilitating inflammation and NBF in individuals with SpA. Thus, HIF1A is a novel therapeutic target in SpA. Furthermore, the selective HIF1A blocker PX-478 was effective at preventing and attenuating SpA pathology, including arthritis and NBF, in curdlan-SKG mice. The therapeutic potential of PX-478 for patients with lymphoma and advanced solid tumors was previously evaluated in a clinical trial, and PX-478 was found to be well tolerated without dose-limiting toxicity (oral administration, dose range: 1–58.8 mg/m2) [49]. The therapeutic effect of PX-478 on immunomodulation was also shown in a preclinical model of lupus nephritis, with decreased autoantibody production and the prevention of T-cell–mediated tissue damage [50]. Furthermore, consistent with our findings in which PX-478 prevented chondrogenesis during ECO, PX-478 was reported to decrease posttraumatic and genetic heterotopic ossification by inhibiting mesenchymal condensations expressing SOX9 [51]. These results indicate that PX-478 has the potential to be a new therapy for SpA by modulating immune activation and chondrogenesis.

Although IL-23 is a pivotal upstream cytokine primarily produced by myeloid cells to activate type 3 immunity, its cellular regulatory activities remain unclear. We found that HIF1A, which is stabilized under hypoxic conditions, substantially increased the expression and secretion of IL-23 in neutrophils but only in the presence of MIF. An injection of PX-478 into curdlan-SKG mice significantly decreased the expression of IL-23 in neutrophils and the expression of downstream type 3 immunity-related cytokines. These results indicate that MIF and HIF1A positively regulate the expression and secretion of IL-23, further supporting the notion that pharmacological inhibition of HIF1A with PX-478 is a sensible treatment for SpA by suppressing type 3 immunity.

Neutrophils are the most abundant immune cells in the inflamed joints of curdlan-SKG mice and in the SF of SpA patients [6, 52]. Similar to our report [6], others have also emphasized the importance of neutrophils in the disease induction and progression of SpA in both preclinical models and humans. Consistent with our previous finding that MIF-secreting neutrophils have the potential to skew Tregs toward Th17-like cells [6], a recent report showed that neutrophil depletion at the disease onset of SpA resulted in reduced Th17 responses and no evident arthritis in SKG mice [53]. Neutrophils were also reported to be required for Th17 cell differentiation from human naive T cells [54, 55]. Although these findings clearly revealed the indispensable role of neutrophils in the onset of SpA in both humans and SKG mice, the specific mechanism by which neutrophils amplify type 3 immunity remains unclear. Our findings indicate that HIF1A intensifies the expression and secretion of IL-23 from neutrophils, leading to the activation of type 3 immunity.

Although neutrophils substantially increase IL-23 levels under hypoxia in the presence of MIF and HIF1A, delineating the individual contribution of IL-23 to SpA pathology in SKG mice is crucial. We found that IL-23 overexpression alone was sufficient to induce SpA-like phenotypes in WT SKG mice. Importantly, arthritis was not evident in IL-23-overexpressing Mif KO SKG mice or IL-23-overexpressing SKG mice treated with PX-478, despite the presence of psoriasis-like dermatitis, suggesting that MIF and HIF1A may be critical mediators of IL-23-primed arthritis. Previous studies have shown that the gene expression or protein concentrations of MIF and HIF are increased in psoriatic arthritis (PsA) patients and that an MIF gene polymorphism is associated with the relapse of arthritis in PsA patients [56–58]. Future studies are warranted to explore the roles of MIF and HIF1A in SpA patients.

While various processes of NBF have been proposed, recent studies using human spinal tissues revealed that ECO is the central mechanism in the development of NBF associated with SpA [13, 59]. Additionally, the importance of inhibiting chondrocyte differentiation to prevent NBF in patients with SpA has recently been highlighted [31]. Similar to our findings of infiltrated neutrophils around areas of NBF in SKG mice, a previous report showed that Gr1-positive neutrophils accumulated chiefly at the sites of the enthesis and the periosteum along with vimentin-positive mesenchymal cells in transmembrane TNF-overexpressing mice, a model with evident NBF in the spine and joints [60]. Human spinal entheseal tissues also accommodate neutrophils [61]. As these findings indicate that neutrophils may contribute to NBF in individuals with SpA, we explored the specific role of neutrophils producing MIF and IL-23 in the development of NBF. Intriguingly, we found that both MIF and IL-23 increased chondrogenesis by enhancing the expression of SOX9 in PCs or ligament tissues of SKG mice. These data suggest that inhibiting these cytokines may effectively prevent NBF in SpA patients. Notably, the IL-23-induced increase in SOX9 expression was absent in PCs isolated from Mif KO SKG mice, suggesting that MIF is also essential for the development of chondrogenesis during NBF. Consistent with our findings, a previous study showed that MIF translocated from the cytoplasm to the nucleus and increased SOX9 promoter activity in human cartilage endplate stem cells [62]. The potential contribution of IL-23 to NBF is noteworthy because controversy persists regarding whether pharmacological inhibition of IL-23 is a sensible therapeutic option for axial SpA [63, 64]. Our findings indicate the potential effectiveness of IL-23 inhibition in suppressing NBF, although additional studies are warranted.

A limitation of this study is that we did not test the direct impact of genetic deletion of HIF1A in SKG mice, as global HIF1A KO is embryonic lethal [65]. In addition, the commercially available background of HIF1A floxed mice is different from the BALB/c background of SKG mice, preventing us from efficiently generating an optimal model to test the preclinical contribution of HIF1A to SpA in SKG mice. Nevertheless, the use of PX-478 substantially suppressed the expression of the HIF1A mRNA and protein, which allowed us to evaluate the impact of the absence of HIF1A through various in vitro and in vivo assays. We also did not evaluate the effect of PX-478 on ileitis, a common extra-articular manifestation of SpA. The presence and severity of ileitis were not consistent in the curdlan-SKG mice in our facility, as previously reported [28], which hampered an accurate evaluation of the efficacy of PX-478 for treating ileitis. Finally, SpA presented a significant amount of heterogeneity. This complexity is reflected in the diversity of inflammatory pathways contributing to SpA, where patients might exhibit a significant dominance of IL-23-, MIF-, or HIF1A-driven inflammation, despite the interactions and connections among these mediators. Hence, recognizing that these diverse inflammatory drivers of SpA could result in distinct responses to treatment with HIF1A inhibitors is essential.

Overall, this study demonstrated that both MIF and HIF1A are pivotal molecules that exacerbate inflammation and NBF in SpA patients. Similar to our recent findings showing that MIF inhibition is effective in curdlan-SKG mice, we provide the first evidence that pharmacological inhibition of HIF1A, a robust MIF-interacting partner, substantially attenuates type 3 immunity-mediated inflammation and NBF in a preclinical SpA model. Further optimization of the administration frequencies and concentrations of the drug are warranted prior to clinical trials.

Materials and methods

Animal model, treatments, and clinical scoring

Female SKG mice (aged 8–10 weeks) were injected with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), curdlan [3 mg/mouse, intraperitoneally (i.p.)], an IL-23 minicircle plasmid [IL-23 PLM, 5 μg/mouse, intravenous (i.v.), Systemic Biosciences], MIF PLM [5 μg/mouse, i.v., Systemic Biosciences], or a control plasmid (CTL PLM, 5 μg/mouse, i.v., Systemic Biosciences) to induce a SpA phenotype and were observed weekly for clinical manifestations of inflammation and NBF over 8 weeks after curdlan or PLM treatment (n = 10 mice per group). Mif knockout (KO) SKG mice (aged 8–10 weeks) were also subjected to the IL-23 PLM or control PLM injection to observe clinical symptoms. The IL-23, MIF or control PLM was administered by HDD tail vein injection, as previously described [6].

One or 4 weeks after curdlan treatment, we orally administered a HIF1A inhibitor dissolved in PBS [PX-478; 5 or 10 mg/kg, three days per week (Monday, Wednesday, and Friday), Selleck biochemistry, cat# S76120] to assess the prophylactic and therapeutic effects of PX-478 on inflammation and NBF in curdlan-SKG mice for 8 weeks after curdlan injection. PX-478 was also administered to IL-23 PLM-injected SKG mice from 1 to 5 weeks post-PLM injection. Moreover, anti-Ly6G (catalog #: BP0075-1; Bio X Cell)/anti-κ IgG2 (catalog #: BE0122; Bio X Cell) monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) or isotype IgG control mAbs (catalog #: BP0089; Bio X Cell) were administered i.p. into curdlan-SKG mice from 4 to 6 weeks postcurdlan injection, as previously reported [66]. Clinical scores for SpA-related manifestations were assessed based on severity scales (Table S1; arthritis, maximum 6 points; dermatitis, maximum 2 points; and blepharitis, maximum 2 points). The scores were evaluated by at least two independent scorers in a blinded manner, and the final scores were calculated as the average of the observations, as we previously reported [6]. At the endpoint, popliteal lymph nodes (PLNs) were isolated for fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). One ankle was subsequently dissected prior to storage in RNAlater for quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), and the other ankle was kept intact and fixed with 10% neutral buffered formalin or optimal cutting temperature (OCT) embedding compound for histopathological assessment. The upper tail was also dissected and fixed with 10% neutral buffered formalin for histopathology. For ankle digestion, the skin was peeled off, and the toes (at the distal phalanges) and tibia (approximately 0.5 cm above the talus bone) were removed. The liver was isolated from a CTL PLM-injected mouse or an IL-23 PLM-injected SKG mouse at 4 weeks after PLM injection, fixed in OCT compound, cut, and stained for IL-23 p19.

Studies with human neutrophils and T cells were approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Board (REB) Committee, University Health Network, Toronto, Canada (approval #s: 20-5654 and 21-5572). The human spinal tissue study was approved by Hanyang University Seoul Hospital (IRB-2014-05-002) and Hanyang University Guri Hospital (IRB-2014-05-001), Seoul, Republic of Korea. The animal experiments were approved by the Animal Resources Centre, University Health Network, Toronto, Canada (approval #: 6068).

Human synovial fluid (SF) cells, neutrophils, and spinal tissues

SF cells (n = 5 per group) were freshly isolated from patients with SpA or knee osteoarthritis (OA; Kellgren & Lawrence grade 2 or 3) and immediately subjected to immunocytofluorescence (ICF) and immunocytochemical (ICC) staining assays. The remaining fresh cells (2 million cells/tube) were also incubated in TRIzol™ reagent (Invitrogen, cat# 15596018) until they were used for RNA extraction and subsequent gene expression assays. Peripheral blood neutrophils were isolated from healthy volunteers without any history of back pain, arthritis, joint injuries, or any other inflammatory conditions (n = 2, aged 25 and 38 years, males) and immediately used for assays. Spinal bone tissues (spinal process containing ligament or facet joints) and spinal bone-derived cells were obtained from patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS, a subtype of SpA) or OA (disease controls) and were used for IHC, WB, and qPCR, as previously described [6, 48].

Identification of MIF-interacting partners

The physical protein‒protein interaction (PPI) data for MIF (P14174) were downloaded from the Integrative Interactions Database (IID) ver. 2021-05 (https://ophid.utoronto.ca/iid) [67]. All experimentally measured (n = 119 out of 172) and predicted (n = 67 out of 172) interactions are included in Supplemental Data 1 (including interactions and their annotations). We focused on specific tissues, cells, and conditions that are well acknowledged to be associated with SpA, including arthritis (bone inflammation, connective tissue diseases, and musculoskeletal systemic diseases) [1], bone/bone marrow [8], musculoskeletal muscle [9], adipose tissues [10], small intestine [11], articular cartilage [12], chondrocytes [13], synovial macrophages [14], synovial membrane [15], cardiovascular system diseases [16], and obesity [17], to identify the most relevant PPIs to SpA (Supplemental Data 2). The number in each column indicates whether both interacting proteins have an annotation (shown as “2”), one of them has an annotation (shown as “1”), or none have an annotation (shown as “0”). We included only interacting proteins with an annotation of “2” when filtering PPIs to identify PPIs commonly shared in the same annotation. Supplemental Fig. 1 (Fig. S1) shows such tissue overlap (brown edges) and tissue-specific interactions (gray edges) for bone, spleen, chondrocytes and articular cartilage tissues. For this figure, we have only considered MIF/CD74 and major SpA-relevant molecules in bone, spleen, chondrocytes, and articular cartilage: CCL2, chemokine ligand 2; FGF18, fibroblast growth factor 18; RUNX2, Runt-related transcription factor 2; SOX9, SRY-Box transcription factor 9; and TNF, tumor necrosis factor. The species-based analysis was also performed based on the same database (Supplemental Data 2).

Transcription factors regulating HIF1A and MIF

Using Catrin Ver. 1 (https://ophid.utoronto.ca/catrin; accessed on 2020/09/08), we identified transcription factors regulating HIF1A (Supplemental Data 3). We used default parameters and all available sources (AURA, CTCFBSDB, ChEA, ENCODE, GTRD, HmChiP, ITFP, JASPAR, MSigDB, Nepth_et_al. PReMod, ReMap2018, TRED, and cistrome.org).

Histopathology

The ankle joints and tails were fixed with 10% neutral buffered formalin for at least 72 h, decalcified in 10% EDTA (BioShop) for 14–21 days, and embedded in paraffin. Serial sections (4 µm) were stained with H&E (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Safranin O/fast green (SO&FG) staining was applied to areas of NBF in the distal tibia or tail vertebrae to assess endochondral ossification, as previously described [6]. Histological scores were evaluated by two independent scorers in a blinded manner according to the histological assessments, as previously reported [6]. The final scores were calculated as the average of the observations. For frozen sectioning, ankle joints were harvested and immediately embedded in OCT compound. The tissues were then cryosectioned (10 µm) at 4 °C in a cryostat, mounted on slides, and used for immunofluorescence (IF) assays.

IHC

IHC was performed as previously described [6]. Specifically, 4-μm sections were deparaffinized in xylene followed by a graded series of alcohol washes. Following proteinase K treatment (10 μg/ml) for 15 min, endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% H2O2 for 30 min. Nonspecific IgG binding was blocked by incubating the sections with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS for 30 min. The sections were then incubated with primary antibodies against HIF1A (Abcam, cat# ab179483; dilution 1:330), SOX9 (Abcam, cat# ab185966; dilution 1:330), RUNX2 (Abcam, cat# ab192256; dilution 1:330), FGF18 (Invitrogen, cat# PA5-106562; dilution 1:330), GDF5 (Abcam, cat# 93855; dilution 1:330), IL-23 p19 (Invitrogen, cat# PA5-20238, dilution 1:330), STAT3 (Cell Signaling, cat#9139; dilution 1:330), phospho-STAT3 (Cell Signaling, cat# 9145; dilution 1:330; used for human spinal samples), or rabbit IgG (Invitrogen, cat# 02-610; dilution 1:330) as an isotype negative control in a humidified chamber overnight at 4 °C. After two washes with water, the sections were incubated with their respective biotinylated secondary antibodies for 30 min. The signal was amplified with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody followed by a Vectastain Elite ABC kit (Vector Laboratories, #PK-6100) and developed with a 3,3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB) HRP substrate kit without nickel (Vector Laboratories, #SK-4100) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Tissue sections were counterstained with hematoxylin (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Immunofluorescence (IF) staining

IF staining was performed as previously described [6]. Akin to the procedures used for IHC, 4 μm sections were deparaffinized in xylene followed by a graded series of alcohol washes. Nonspecific IgG binding was blocked by incubating sections with 1% BSA in PBS for 30 min. The sections were then incubated with primary antibodies against MIF (Abcam, cat# ab226166; dilution 1:330), HIF1A (Abcam, cat# ab179483; dilution 1:330), COL2A1 (Abcam, cat# ab34712; dilution 1:330), Scleraxis (Abcam, cat# ab58655; dilution 1:330), or rabbit IgG (Invitrogen, cat# 02-610; dilution 1:330) as an isotype negative control in a humidified chamber overnight at 4 °C. After two washes with water, the sections were incubated with secondary antibodies conjugated with either Texas Red (Abcam, cat# ab6719; dilution 1:200) or Alexa Fluor 488 (Abcam, cat# ab150113; dilution 1:200) for 30 min at room temperature. After washing, a diluted 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) solution was added to the sections on each slide and incubated for 2 min at room temperature. The sections were washed once with PBS and mounted with anti-fade mounting media (DAKO). The sections were visualized using either an EVOS FL Imaging System (Life Technologies) or a CYTATION5 imaging reader (Bio Tek).

Curdlan or MIF treatment of cells and tissues

Neutrophils (2 × 106 per well) were isolated from the tibial bone marrow of WT or Mif KO SKG mice and cultured in a 96-well plate containing Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) supplemented with or without curdlan (10 µg/ml) in the presence or absence of PX-478 (5 μM, Selleck biochemistry cat# S7612) under normoxic (21% O2) or hypoxic conditions (2% O2) for 3 or 18 h.

PCs were isolated as previously reported by Duchamp et al. [33] Specifically, tibias were isolated from healthy WT or Mif KO SKG mice. After the bone marrow was removed, the tibia was cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (standard media) supplemented with 10% FBS (Wisent Bioproducts, cat# 080-150) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Wisent Bioproducts, cat# 450-200-EL). After 2 weeks, the tibia was removed, and the PCs that migrated from the tibia and proliferated were treated with or without recombinant mouse MIF (rmMIF; 0, 10, 50, or 100 ng/ml) and/or rmIL-23 (0, 10, 50, or 100 ng/ml) in standard or chondrogenic differentiation (ChD) media in the presence or absence of an anti-IL-23 p19 neutralizing antibody (0.2 μg/ml; R&D, cat# AF1619) under normoxic (21% O2) or hypoxic conditions (2% O2) for 1, 3, 6, or 12 days. Alternatively, PCs were transfected with or without a small interfering (si) RNA targeting STAT3 (50 nM; Santa Cruz, cat# sc-29494) or control siRNA (50 nM; Qiagen, cat# 1027280) using Lipofectamine® RNAiMAX Transfection Reagent (10 nM; Invitrogen) in 0.5% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin media under normoxic (21% O2) or hypoxic (2% O2) conditions for 24 hours, followed by treatment with or without rmIL-23 (100 ng/ml) for 24 h, as we previously reported [68]. RNA, protein, and culture supernatant were then extracted for qPCR, immunoblotting and ELISA, respectively. Similarly, tibia-talus tenocytes were isolated from WT SKG mice and treated with or without recombinant mouse MIF (rmMIF; 0, 10, 50, or 100 ng/ml) in standard DMEM for 24 h. Protein lysates were then used for immunoblotting assays.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was performed as we previously described [6]. Cells were stimulated with brefeldin A (BioLegend, cat# 420601) with or without phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) and ionomycin (BioLegend, cat# 423302) prior to detection of intracellular cytokines. Following stimulation, the cells were initially stained with a fixable live/dead stain (L/D NIR, Invitrogen, cat# L10119) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Subsequently, the cells were blocked with FcX (1:50, BioLegend, cat# 101320) in staining buffer (BioLegend, cat#420201) for 5 min at 4 °C prior to the addition of surface antibodies and staining for 20 min at 4 °C. The cells were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde buffer (BioLegend, cat# 420801) and permeabilized with intracellular staining buffer (BioLegend, cat# 421002). Then, intracellular staining was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The data were acquired on an LSR II or Canto II (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FlowJo (version 10.6, Becton Dickinson). The antibodies used for mouse samples are listed in Table S2.

Reverse transcription and qPCR

RNAs were isolated from mouse neutrophils and PCs or human SF cells and spinal bone-derived cells as previously reported [6]. RNA concentrations were determined using NanoVue (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). Following RNA quantification, equal amounts of RNA (1000 ng) were converted to cDNA using the QuantiTect Reverse Transcription PCR Kit for mRNA (Qiagen, cat# 205311), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For qPCR, 5 ng of RNA per well was used for the gene expression analysis with primers and SYBR Green Master Mix (Bio-Rad, cat# 1725271) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The reactions were incubated in a 96-well plate (Bio-Rad, cat# HSL9605) and performed in duplicate. The specificity of the amplified qPCR products was assessed by performing a melting curve analysis on a LightCycler 480 instrument (Roche). The relative expression of the PCR products was calculated using the 2−ΔCt method. All primers were designed using Primer3Plus online software (Table S3). The data were normalized to the levels of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh for mice or GAPDH for humans) or β-actin (Actb for mice or ACTB for humans) for mRNA analyses, as appropriate. The reference genes showed highly stable expression compared to other candidate reference genes, as previously reported [69, 70].

ELISA

The concentrations of IL-23, IL-17A and MIF in the serum of SKG mice and IL-23 secreted from SKG neutrophils into culture media were measured using a LEGEND MAX Mouse IL-23 ELISA Kit (BioLegend, cat# 433707), a LEGEND MAX Mouse IL-17A ELISA Kit (BioLegend, cat# 436207), and a LEGEND MAX Mouse MIF ELISA Kit (BioLegend, cat# 444107), respectively. The concentration of MIF secreted from human neutrophils was measured with a LEGEND MAX Human Active MIF ELISA Kit (BioLegend, cat# 438407). The samples were analyzed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Western blot analysis

Equal amounts of cell lysates in RIPA buffer (Sigma‒Aldrich, cat# R0278) were applied to SDS-polyacrylamide gels (4-20%; Bio-Rad, cat# 4561096) and electrophoresed, as previously reported [6]. The separated proteins were electroblotted onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. The membranes were blocked in 10 mM Tris-buffered saline (TBS; Bio-Basic, cat# A0027) containing 5% skim milk (BioShop, cat# SKI400) and probed for 1.5 h with rabbit IgG primary antibodies (1:250) specific for MIF (R&D, cat# MAB2892), HIF1A (Abcam, cat# ab179483), SOX9 (Abcam, cat# ab185966), RUNX2 (Abcam, cat# ab192256), FGF18 (Invitrogen, cat# PA5-106562), GAPDH (Abcam, cat# ab181602), STAT3 (Cell Signaling, cat# 4904; used for mouse samples), STAT3 (Cell Signaling, cat# 9145; used for human spinal samples), phospho-STAT3 (Cell Signaling, cat# 9145), C-MYC (Cell Signaling, cat# 5605), α-tubulin (Cell Signaling, cat# 2144), PARP p85 (Promega, cat# G7341), or mouse monoclonal IgG for β-actin (1:1000; Sigma‒Aldrich, cat# A1978) in blocking buffer. After washing the membranes with TBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBS-T; BioShop, cat#TWN510) three times, the membranes were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit (1:5000; Sigma‒Aldrich, cat# AP106P) or anti-mouse (1:10,000; Sigma‒Aldrich, cat# A2179) secondary antibodies in TBS containing 5% skim milk. The membranes were subsequently washed with TBS-T, and the protein bands were visualized with an enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (SuperSignal Western blot Enhancer, Thermo Fisher Science, cat# 46640) using a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc apparatus. The blots were scanned, and the signal intensity was quantified using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health).

Immunoprecipitation

Neutrophil immunoprecipitation was conducted according to the protocol outlined in the Immunoprecipitation Kit (ab206996) with a customized approach. Neutrophils cultured under hypoxic conditions (2%) overnight were first washed with cold PBS and then lysed using 1× Cell Lysis Buffer (Cell Signaling; 9803S) supplemented with protease inhibitors. Following lysate preparation, 500 μg of lysate was precleared with Protein A/G-Sepharose beads. The cleared supernatant was then subjected to an overnight incubation with either 5 µg of anti-MIF antibody (Thermo Fisher, 20415-1-AP) or control IgG (Abcam: ab37415). Immunocomplexes were subsequently purified by an incubation with 25 μl of Protein A/G-Sepharose beads for 1.5 h, followed by three washes with 1x wash buffer. Finally, the bound proteins were eluted by boiling with 30 μl of 2× Laemmli buffer for western blot analysis.

PCs isolated from the tibias of SKG mice were cultured in DMEM (standard) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin for 2 weeks as described above. After washing with ice-cold PBS, the PCs were lysed in RIPA buffer (Sigma‒Aldrich, cat# R0278), collected with cell scrapers, and gently transferred to a precooled microcentrifuge tube. The tube was then agitated for 30 min and centrifuged for 5 min at 4 °C. The aspirated supernatant was then incubated with an anti-mouse monoclonal MIF antibody (2 μg/ml; R&D, cat# MAB2892; clone: 932612) overnight at 4 °C with rotation. The sample was mixed with a Protein G-coupled Sepharose bead slurry (Abcam, cat# 193259) and incubated at 4 °C with rotation. After the supernatant was removed by centrifugation, the beads were washed extensively with PBS to remove unbound antibodies, and the proteins were eluted from the beads with glycine buffer. The proteins were then used for immunoblotting as described above.

Microcomputed tomography (microCT)

For assessments of NBF and the temporal profile of bone structural changes, in vivo longitudinal microCT (SkyScan 1276, Bruker Corporation) was performed on curdlan-treated SKG mice, IL-23 PLM-injected SKG mice, IL-23 PLM-injected Mif KO SKG mice, and PX-478-treated SKG mice, as well as mice in the respective control groups. After 8 weeks of curdlan or PLM treatment, the mice were euthanized with CO2 (1.3 L/min), and scans were performed. All microCT scans were reconstructed with InstaRecon software, and screenshots of volume-rendered CTvox (Bruker Corporation) images were captured, as we previously reported [6].

Statistical analysis