Abstract

Black women experience persistent sexual pain that may often last longer than White women. Despite the value of sexual communication to alleviate sexual pain concerns, many women do not disclose sexual pain to their partners. Limited research explores barriers to disclosing sexual pain to partners among Black women. This study seeks to fill this gap. Relying on an integration of Sexual Script theory and Superwoman Schema, the study explored the barriers that premenopausal, cisgender Black women from the Southern USA perceived when disclosing sexual pain to their primary partners. We identified five common themes from women’s open-ended responses to an online survey: (a) distressing emotions associated with disclosure; (b) limited knowledge and communication skills; (c) protecting partner’s feelings and ego; (d) invading privacy; and (e) taking sole responsibility for managing sexual pain. Findings suggest a combination of intrapsychic, interpersonal and cultural factors influence Black women’s perceived ability to have direct and open dyadic communication about sexual pain with their partners. Implications for Black women’s sexual health and relationship outcomes are discussed.

Keywords: Sexual pain, Black women, partner communication, sexual scripts, Superwoman

Introduction

Although both Black and White women in the USA report similar rates of sexual pain (Harlow and Stewart, 2003), data from a nationally representative US sample indicate Black women experience persistent sexual pain1 that may last longer compared to White women (Townes et al. 2019). Sexual pain influences women’s sexual functioning, personal wellbeing and intimate relationships (Donaldson and Meana 2011). A woman’s sexual pain impacts her mind and body, as well as her sexual partner, who may witness the pain sex can bring (Sadownik et al. 2017). However, many women do not disclose sexual pain to their partners due to discomfort, embarrassment and fear of being harshly judged (Elmerstig, Wijma and Swahnberg 2013) and continue to engage in painful sexual activities (Carter et al. 2019).

Non-disclosure of sexual pain can impair sexual desire and arousal (Reissing et al. 2003), lead to hypersensitivity in the vulva and vagina area (Donaldson and Meana 2011), and create relationship strain between partners that can exacerbate sexual problems (Merwin et al. 2017; Pazmany et al. 2015). Given the negative effects of sexual pain, there is value in identifying barriers to pain disclosure among Black women (Townes et al 2019). Trepidation about disclosure is likely influenced by sexual scripts and cultural mores that inform the meaning Black women attach to sexual pain (Sadownik et al. 2017). For example, Black women may not disclose sexual pain to their partners due to gendered-racial socialisation to maintain silence around sex (Abrams, Hill and Maxwell 2019) and accept pain as normative (Jones, Robinson and Seedall 2018).

No research has explored the barriers to disclosure of sexual pain among Black women, whose pain is disproportionately prevalent and persistent compared to White women (Townes et al 2019). Thus, the current paper seeks to fill this gap in the literature informed by Sexual Script theory (Simon and Gagnon 1986) and Superwoman Schema (SWS; Woods-Giscombé 2010). This study explored if Black women perceived their sexual pain to be an issue and what cultural, interpersonal and intrapsychic barriers hinder Black women’s disclosure of sexual pain to their partners. Findings from the study can be used to inform sexual health interventions that address sexual pain and enhance sexual communication between Black women and their partners.

Sexual pain disparities

Although approximately one in five Black women in the USA reported pain during their last experience of sexual intercourse (Townes et al. 2019), Black women’s rates of sexual pain are likely underestimated due to underreporting symptoms, misinterpretation of pain and dismissive medical providers (Brown et al. 2015; Labuski 2017). Absence of reference to Black women’s sexual pain in the literature calls for special focus on this population, because without it, Black women will continue to suffer from sexually painful experiences that adversely impact their sexual, psychological and relational health. Feminist scholars studying the issue of medicalisation argue a need to consider social, cultural and political factors that influence sexual pain among women (Farrell and Cacchioni 2012). For Black women, patriarchal, racist and heterosexist interactions likely shape their reasons for continued engagement in painful sexual activities without disclosing this information to their partners. Due to racial disparities in painful sex and limited discussion of the intersectional stressors that influence Black women’s sexual health, an examination of barriers that limit sexual communication with their partners is warranted (Carter et al. 2019).

Sexual communication with partners

Previous qualitative research on primarily White samples demonstrates how social factors such as gender norms, conflict avoidance, and pain minimisation impact women’s decisions to not disclose sexual pain (Ayling and Ussher 2008). However, no research examines the factors that prohibit Black women’s sexual communication with their partners. Black women are often socialised not to expect pleasure from sexual experiences (Hargons et al. 2018), which may result in unwanted pain and discomfort. For example, Carter et al.’s (2019) study exploring reasons for non-disclosure of sexual pain highlights the robust association between a lack of sexually pleasurable experiences and non-disclosure of sexual pain to partners. The authors report several reasons for non-disclosure, including gendered relationship scripts and cultural norms. However, there was no discussion of the impact of race and other intersectional stressors on women’s reports of sexual pain.

Sexual communication has several benefits, including enhanced sexual arousal (Rancourt et al. 2016), increased orgasms (Blair et al. 2015), and mutually satisfying sexual experiences (Carter et al. 2019). Sexual communication is also strongly linked to relationship satisfaction through emotional closeness and intimacy (Merwin et al. 2017). For example, women’s experiences of sexual pain can be influenced by their partners’ response of attention, love and understanding (Blair et al. 2015). Being in a mutually supportive relationship serves as a protective factor against sexual pain as frequent sexual communication reduces the likelihood of sexual pain complications (Jones, Robinson and Seedall 2018). Although an intimate relationship does not eliminate sexual pain entirely, sexual communication between partners can lessen the negative physical, emotional and psychological distress associated with sexual pain (Awada et al. 2014).

Integrated theoretical framework

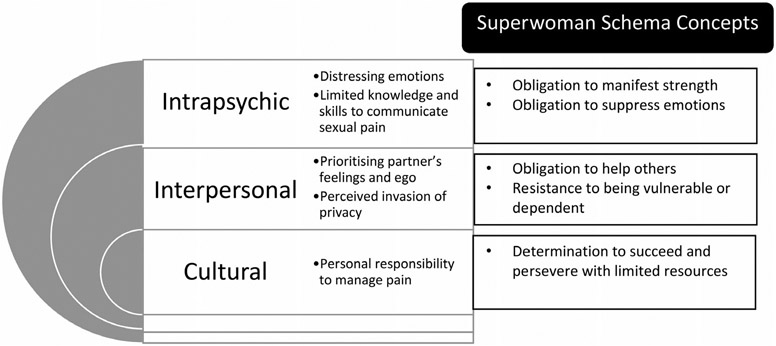

Sexual Script theory (Simon and Gagnon 1986) suggests sexual behaviour is influenced by an interplay of intrapsychic experiences, interpersonal scripts and cultural scenarios. Intrapsychic experiences are thoughts, desires and motives about how people want to behave. Interpersonal scripts include what sexual behaviours people do. Cultural scenarios are norms, beliefs and expectations about how individuals should act. These three factors determine what sexual behaviours are acceptable and expected, and thus impact Black women’s beliefs about their sexual activities. For example, Bowleg, Lucas and Tschann (2004) highlight how Black women in the USA typically enact interpersonal scripts wherein partners are viewed as holding power and control in sexual relationships, particularly related to condom use. Historically, the sexual scripts literature has centred heterosexual and monogamist relationship dynamics; however, recent research indicates sexual scripts can be more flexible as they resist and operate beyond heteronormative rules (Ekholm et al. 2021). Still, research exploring sexual scripts among Black sexually diverse women remains limited. In this study, we argue a power dynamic may emerge whereby Black women may not disclose their sexual pain to their partners because they feel obliged to manage their pain without complaint and prioritise their partners’ pleasure to sustain relationships.

To account for the unique gendered-racial experiences of Black women, we seek to integrate sexual script theory with the Superwoman Schema (SWS; Woods-Giscombé 2010) to demonstrate how Black cultural scripts regarding sex and pain are internalised and manifest interpersonally. Many Black women have been historically and culturally socialised to fulfil a Superwoman role by suppressing emotions, displaying strength, resisting vulnerability, succeeding despite limited resources, and caregiving at the expense of self-care to overcome life stressors (Woods-Giscombe et al. 2019). These teachings have been passed down intergenerationally from their foremothers who endured harsh experiences during slavery. Because cultural sexual scripts are learned indirectly and rarely questioned, it is likely some Black women have internalised racial biases and false narratives about their ability to handle sexual pain (Hoffman et al. 2016). We hypothesise false notions of high pain tolerance could be attributed to hip hop song lyrics that reinforce Black superwoman sexual scripts of women being subject to sexual aggression (e.g., ‘beating the p*ssy up’) and treated as sexual objects (Ward 2002). Furthermore, negative emotions associated with sexual pain among Black women may be ‘culturally fed and maintained by silence’, preventing sexual communication (Sadownik et al. 2017, 12). As Simon and Gagnon (1986) posit, people are partially scriptwriters, and Black women may adapt cultural scenarios of being superwomen by perceiving a need to withstand psychological distress and avoid vulnerability when choosing to disclose sexual pain to their partners. Although several studies have utilised sexual script theory to explore the intersection of culture, gender and sexuality, this is the first study of the authors’ knowledge to integrate sexual script theory and Superwoman Schema to understand factors that inhibit Black women’s disclosure of sexual pain (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

An integrated model of sexual scripts theory and superwoman schema to understand black women’s reasons for non-disclosure of sexual pain to partners.

The current study

Many women continue to engage in painful sex and choose to not reveal these experiences to their sexual partners (Thomtén and Linton 2013). However, limited research has explored barriers to communicating sexual pain to their partners. Since sexual pain can inhibit women’s ability to orgasm and experience sexual pleasure (De Graaff et al. 2016), as well as negatively affect sexual communication and relationships (Rancourt et al. 2017), there is a need to understand the factors that contribute to Black women’s silence regarding their sexual pain. Therefore, the current qualitative study sought to investigate the following research question, ‘what barriers do Black women encounter when disclosing their sexual pain to their primary partners?’ Findings from the study can inform culturally relevant, partner-specific interventions focused on communication to address sexual pain among this population.

Methods

Participants and procedures

Data were collected from phase one of a larger sequential mixed-methods project (Pain and Pleasure Study), which focused on sexual pain, pleasure and anxiety among N = 294 premenopausal cisgender Black women in the Southern region of the USA. Following institutional review board approval from the University of Kentucky, participants were recruited in November 2020 through social media platforms (e.g. Instagram and Facebook) and by word-of-mouth. Participant eligibility criteria included: (a) identifying as a Black cisgender woman, (b) being between 18-50 years of age, (c) being pre-menopausal, (d) living in a Southern US state, and (e) having previous experience of sexual intercourse.

Participants were asked to complete a 15-minute online survey consisting of Likert scale, multiple choice, and open-ended questions. For the purposes of this study, only participants who answered the follow-up open-ended question ‘Why haven’t you told your partner about your sexual pain?’ were included. Of the n = 179 Black women who reported experiencing sexual pain, n = 79 indicated they had not talked to their primary partner about their sexual pain concerns, and n = 65 provided reasons as to why not. Participants were between 21 and 44 years of age (M = 30.18, SD = 6.01). Most participants had a graduate or professional degree (n = 47, 59.5%), identified as heterosexual (n = 64, 81.0%), and indicated single as their relationship status (n = 44, 55.7%) (see Table 1). Approximately 41% (n = 32) of participants stated they never reached orgasm during painful sex. All participants who completed and entered their email at the end of the survey were entered into a raffle for one of three $25 Target gift cards.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics (N = 79).

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Ethnicity | |

| African American | 71 (89.9) |

| African | 5 (6.3) |

| Caribbean | 6 (7.6) |

| Latinx | 5 (6.3) |

| Biracial | 3 (3.8) |

| Education level | |

| Technical college | 1 (1.3) |

| Some college | 9 (11.4) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 22 (27.8) |

| Graduate/Professional Degree | 47 (59.5) |

| Sexual orientation | |

| Heterosexual | 64 (81.0) |

| Bisexual | 7 (8.9) |

| Gay/Lesbian | 2 (2.5) |

| Queer | 3 (3.8) |

| Pansexual | 3 (3.8) |

| Relationship status | |

| Single | 44 (55.7) |

| In a relationship | 13 (16.5) |

| Cohabitating | 4 (5.1) |

| Married | 9 (11.4) |

| Divorced | 3 (3.8) |

| Dating | 6 (7.6) |

Note: The measure of ethnicity was determined by response to an instruction ‘check all that apply’. Of the participants who reported being biracial, two were Black and Asian and one was Black and Native American.

Data analysis

A deductive approach was utilised to analyse the data corpus informed by sexual script and superwoman theory. Data were analysed by the first and second authors using Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-step process for thematic analysis. In step one, responses were reviewed and accompanied by written memos to highlight interviewer reactions. In step two, each response was initially coded to capture latent (what was hinted or suggested) and semantic (what was stated explicitly) regarding barriers to communicating about sexual pain. For instance, we identified invulnerability as a component of Superwoman Schema that influences interpersonal sexual scripts; therefore, we coded for invulnerability in participants’ responses. Because invulnerability emerged as a common experience among participants, it became a major theme to sexual pain disclosure. In step three, responses were re-read and codes regarding communication barriers were synthesised into preliminary themes. In step four, the preliminary themes were reviewed. The authors met regularly to discuss individual experiences that influenced coding analysis and theme development. For example, the authors, who all identify as Black women, discussed how their upbringing informed their willingness to disclose sexual pain with sexual partners. Any remaining codes that did not fit into themes were re-evaluated, and themes were re-arranged to capture all data. In step five, the first author generated theme names to capture similarities and differences across participants’ experiences and intended meanings. These themes were shared with the co-authors for validation. Finally, in step six, the agreed recurrent themes were used to structure this paper.

Data trustworthiness

To establish data trustworthiness of this study, the following methods were used: prolonged engagement with the data corpus; preparation of research memos to document thoughts, interpretations and reactions to responses about sexual pain; the use of an integrated framework to substantiate our codes and themes; team-based data coding; peer debriefing; and co-author validation of themes (Nowell et al. 2017).

Author subjectivities

The authors of the paper are Black cisgender women. One identifies as bisexual, another as queer, and the others identify as heterosexual. At the time of the study, four women were partnered and two were single. Each author has an interest in studying Black women’s sexualities and sexual behaviours.

Results

Informed by sexual script theory and superwoman schema, five themes reflecting gendered-racial sexual barriers were developed from the data: (a) distressing emotions associated with disclosure; (b) limited knowledge and communication skills; (c) protecting the partner’s feelings and ego; (d) invading privacy; and (e) taking sole responsibility for managing sexual pain (Figure 1).

Intrapsychic experiences

Black women described how distressing emotions (n = 11) impeded their disclosure of sexual pain to their partners. For example, participants noted the ‘embarrassment’, ‘shame’ and ‘discomfort and awkwardness’ that emerged when they thought about reporting their sexual pain. One woman shared, ‘every time I boost myself up to say something, I get anxious and choose not to’. Although she may have had intentions to communicate her sexual pain, her anxiety ultimately inhibited her disclosure. Other participants stated, ‘I don’t want to draw attention to the pain’ and ‘in the past it hasn’t been received well so I avoid sexual contact’ in sharing their strategies of distraction to minimise painful sensations and avoidance of self-disclosure to partners.

The second theme of limited knowledge and communication skills (n = 9) highlighted how some women lacked knowledge about the aetiology of their pain and struggled to communicate this uncertainty. For example, when asked why she chose not to disclose her sexual pain, one participant stated, ‘I don’t know what to tell him’. Another woman shared, ‘I don’t understand it [the pain], so I don’t want to make my partner feel like sex is completely off the table because I feel pain a good amount of the time’. Both participants were hesitant to reveal their sexual pain to their partners due a general lack of knowledge. More specifically, the latter participant expressed fear that her partner would stop having a sexual relationship with her if she revealed her sexual pain. Therefore, she silenced herself to avoid an altered sex life with her partner.

Interpersonal scripts

Because sexual pain is typically experienced within dyadic relationships, interpersonal factors also served as barriers to disclosing sexual pain to partners. The third theme of protecting partner’s feelings and ego (n = 14) indicated how some women did not reveal their sexual pain as part of an effort to ensure their partner’s psychological comfort and sexual pleasure. One participant noted, ‘it’s [the pain] not horrible, and I don’t want him to be self-conscious’. Another woman stated, ‘I don’t want them [partner] to think they are doing anything wrong’. Despite experiences of sexual pain, participants feared telling their partners about their role in aggravating or maintaining pain to protect their partners’ egos.

Other women expressed concern about how their partners would perceive them after disclosure. Two participants shared: ‘I don’t want him to think I’m dysfunctional’, and ‘I don’t think he would understand how I feel’ regarding their sexually painful experiences. Another participant refrained from shifting the blame of her sexual pain onto her partner. In explaining her rationale, she stated, ‘sex for me has been generally constructed around my partner’s pleasure, as I believe that should be the priority’. In hindering disclosure of their sexual pain, participants endorsed an interpersonal script that their partner’s sexual pleasure was priority, even while they simultaneously experienced sexual pain.

In contrast, the fourth theme of invading privacy (n = 9) revealed how women perceived disclosure of sexual pain as too difficult to share with their partners. Women reported, ‘I feel like it’s too personal’ and ‘I don’t feel obligated to tell him’, when asked about reasons for their non-disclosure of sexual pain. Another woman continued by saying, ‘It’s not their business and I don’t want to weird him out’. These women did not feel comfortable disclosing their sexual pain and believed doing so might result in them being judged. Another reason some women voiced privacy concerns was because they either had ‘no consistent partner to tell’ or they only had a sexual relationship with their partner in stating, ‘we’re not together’.

Cultural scenarios

As cultural norms concerning sex influence the ability to engage in sexual communication (Rose 2003), Black women may have internalised cultural beliefs about how they should communicate about sexual pain. Our fifth and final theme reflects Black women’s perceived sole responsibility to manage sexual pain (n = 20). Participants indicated that the reasons they refrained from discussing sexual pain were because, ‘it’s not bad enough’, ‘it’s not that serious’, and ‘it isn’t so bothersome that I feel like it warrants an intentional conversation’. Underlying these responses are culturally endorsed scripts of being strong Black women who only disclose and discuss sexual pain when it becomes overwhelmingly necessary to do so.

In addition to minimising the significance of pain, other participants emphasised their need to handle their sexual pain alone. For example, one woman said, ‘I just deal with the pain privately [otherwise] my partner will think I am weak or overthinking my pain’. This participant may have internalised the idea that endurance of sexual pain is a sign of strength from racialised gendered sexual scripts. Similarly, other participants indicated, ‘I feel like it’s [the pain] my problem, not theirs’, and ‘it’s not their responsibility to bear’, highlighting beliefs that addressing pain is a personal responsibility rather than an issue sexual partners can work together to solve. Another woman expressed the fear of being perceived as worrisome by asking, ‘there isn’t anything they can do about it [the pain], so why worry them?’ Overall, participants endorsed Superwoman cultural scripts of displaying strength, resisting emotional vulnerability, and persisting through their pain to maintain sexual relationships.

Discussion

This study sought to analyse the perceived barriers to communicating sexual pain between Black women and their partners. Findings reveal Black women encountered numerous barriers to disclosing sexual pain to their partners.

The first theme of distressing emotions demonstrates how Black women’s intrapsychic experiences of fear, anxiety, embarrassment and frustration hinder their sexual pain disclosure. This finding aligns with previous literature suggesting women’s psychological distress can inhibit sexual communication (Ayling and Ussher 2008; Donaldson and Meana 2011). According to the SWS, many Black women are socialised to suppress uncomfortable emotions (Woods-Giscombé et al. 2019). To avoid shame associated with sexual pain, participants in this study endorsed an intrapsychic sexual script of silencing themselves (Abrams, Hill and Maxwell 2019) to conquer sexual pain independently. Additional research indicates negative feelings resulting from sexual pain can lead to sexual self-consciousness (Thorpe et al. 2022) and poor dyadic sexual communication (Pazmany et al. 2015). Although sex can have stress-relieving elements (Meston and Buss 2007), Black women who encounter emotional barriers towards disclosing their sexual pain may not fully reap the psychological benefits of sex.

The second theme of limited knowledge and communication skills reflects how some Black women did not understand the aetiology of their sexual pain and therefore struggled to communicate their concern to sexual partners. The struggle to disclose to partners may extend to reporting sexual pain to medical providers, who can also help address and alleviate pain-related sexual concerns (Townes et al. 2020). Several factors may influence Black women’s sexual communication skills. First, although nearly 20% of women encounter sexual pain, the public has limited access to sexual health information (Donaldson and Meana 2011) and painful sex can result from serious and complex health conditions. Second, a person’s comfort discussing sex, and more specifically sexual pain, can be informed by cultural norms (Jones, Robinson, and Seedall 2018). Sexual script theory suggests these norms shape sexual communication skills, or a lack thereof. Third, Black women encounter intersectional stressors due to their gendered-racial identities that influence how others, including how partners and medical providers (Labuski 2017) discuss and address their pain complications. Despite reporting sexual pain, Black women’s sexual pain is often unaddressed, minimised, and/or normalised when seeking treatment from medical providers, which may further exacerbate their decisions to not disclose their sexual pain unless specifically asked. Others may assume Black women do not encounter pain and thus choose not to inquire about painful sex (Hoffman et al. 2016). There is value in fostering conversations about Black women’s sexual pain to reduce stigma regarding this topic. Normalising discourse regarding sexual pain can also enhance dyadic communication skills and sexual health outcomes (Pazmany et al. 2015).

At an interpersonal level, our results indicated Black women avoided bringing attention to their sexual pain by protecting their partner’s feelings and/or engaging in selfprotection strategies. For example, some women refused to disclose their sexual pain to ensure their partners did not assume blame for their sexual pain. Participants endorsed an interpersonal script of prioritising their partner’s sexual pleasure (Bowleg, Lucas and Tschann 2004; French 2013). Through the SWS’s teaching of caregiving at the expense of one’s own needs (Woods-Giscombe 2010), Black women may feel obliged to be a source of sexual pleasure for others, while disregarding their own sexual health and functioning (Fasula, Carry and Miller 2014). Our findings align with prior research that suggests women, in general, endure sexual pain as part of their subservient role to sexually satisfy a partners (Carter et al. 2019). Internalised misogynoir and heteronormativity may play a role in Black women’s non-disclosure of sexual pain as well as partners’ responses to their disclosure in efforts to adhere to sexual scripts that prioritise men’s pleasure at their own expense. Although sexual scripts can vary depending on gendered and sexual relationship dynamics (Elkholm et al. 2021), Fahs (2014) suggests the desire to protect partners’ egos is a barrier against disclosure across diverse sexualities. The commonness of this interpersonal script highlights the impact of cultural messaging to practise caregiving at the expense of self-care experienced by many Black women.

Participants expressed worry that sexual pain disclosure could change relationship dynamics and result in a partner discontinuing sex and/or engaging in sex with others. A qualitative study about relationship scripts has highlighted many Black women believe men control relationship trajectories and infidelity is normative (Bowleg, Lucas and Tschann 2004). Therefore, women in our study may have refrained from self-disclosure to avoid being considered difficult or complaining (Carter et al. 2019). Furthermore, participants questioned the value of disclosure in fear their partners would not care, understand or adjust to alleviate their sexual pain. Yet, avoidance of sexual communication can lead to more problems (Rancourt et al. 2016). Poor sexual communication hinders an understanding of sexual preferences among partners, reducing sexual and relationship satisfaction (Pazmany et al. 2015). In contrast, honest and frequent sexual communication, in addition to trying different sexual positions, toys and mind-body interventions can increase sexual pleasure, reduce sexual pain, and improve relationship outcomes (Blair et al. 2015).

Surprisingly, some women in this study believed sexual pain disclosure was an invasion of privacy. Although we inquired about disclosure to primary sexual partners, some Black women believed casual sex did not warrant sexual communication due to limited emotional closeness (Dogan et al. 2018). An interpersonal script of emotional invulnerability is likely influenced by two factors: 1) casual sex is not associated with relationship investment, which hinders Black women’s willingness to disclose and solve sexual issues with their partners; and 2) Black women may feel obliged to display strength while engaging in painful sexual intercourse. Minimising the impact of sexual pain due to its tolerability or infrequency may encourage women to fake sexual enjoyment instead (Thomas et al. 2017). Furthermore, as some women indicated, not having a primary partner or not being in a committed relationship provides less relationship security to facilitate conversations about sexual pain.

Last, participants expressed the need to solely manage their sexual pain. This finding aligns with the Superwoman Schema which suggests that Black women should present themselves as strong, emotionally and psychologically resilient, and self-sufficient (Woods-Giscombe et al. 2019). In this study, participants felt obliged to carry the burden of managing sexual pain instead of seeking help from others, including their partners. Additionally, in healthcare settings, Black women report feeling shamed and met with racist stereotypes that influence being heard and treated equitably (Sacks 2018). From encounters where others likely minimise their reports of sexual pain, some Black women may have internalised the belief their pain does not matter. Therefore, they enact cultural scripts to minimise their pain and appear ‘stronger’ in the eyes of their partners, medical providers and the larger community. However, disclosing sexual problems can enhance intimacy among partners and encourage new sexual activities such as foreplay and masturbation, oral and anal sex, and phone or video sex to accommodate and alleviate pain (Merwin et al. 2017). Dyadic coping with sexual pain requires collaboration and interdependence to reduce sexual difficulties, psychological distress and relationship strain (Jones, Robinson and Seedall 2018). To move beyond binary options of disclosure and no sex and non-disclosure and painful sex, Black women and their partners could explore their limited conceptualisation of what sex is (i.e. penile-vaginal intercourse) and creatively work with the pain instead of hiding it.

Limitations

This study is the first to examine barriers to sexual pain disclosure among premenopausal Black women located in the Southern USA. Despite making a unique contribution to existing literature, the study has several limitations. First, most women in our sample identified as single and heterosexual and reported their last sexual encounter with male partners. Although penetrative sex is associated with sexual pain (Bergeron et al. 2015), our results may not capture barriers to sexual pain disclosure among Black women who identify as LGBTQ, have same sex partners, and/or only engage in non-penetrative sex. Future research should also expand discussion of barriers to sexual communication among diverse couples with various relationship structures. Second, almost 60% of our sample had graduate degrees, which serves as an understudied population but likely influenced the context of our results. More years of education could inform how Black women communicate sexual pain with their partners based on their race-gender-class identities of having greater access to medical information and healthcare. Third, we did not collect data on the duration of participants’ relationships with their primary sexual partner, which may affect willingness to engage in sexual communication. Furthermore, we did not examine the data for factors such as mental health problems that might impact Black women’s sexual functioning and communication. Last, our findings come from secondary data analysis of open-ended responses elicited via an online survey; therefore, despite the quantity of data obtained, the study may have lost in-depth understanding of partner communication barriers without conducting face-to-face interviews.

Implications

The findings from this study have implications for sex and relationship research and practice. Black women’s sexuality is minimally represented in existing literature (Jenkins-Hall and Tanner 2016), with even fewer studies investigating their reports of sexual pain (Hargons et al. 2021). More research with diverse samples of Black women is needed to better understand the origins of their sexual pain and barriers to communicating this pain to partners. Future research may extend the aims of the current study by conducting dyadic interviews about sexual pain with couples. Including partners’ perspectives may provide further insight into how partners respond before, during and after sexual pain has been reported. Additionally, because Black women report high rates of reproductive health conditions such as uterine fibroids (Al-Hendy et al. 2017), endometriosis (Kyama et al. 2007) and polycystic ovarian syndrome (Ding et al. 2017), research is also needed to investigate sexual pain accompanied with these disorders to inform culturally relevant sexual health interventions.

Psychoeducation may be helpful in providing culturally relevant treatment and support. Two major aims of this study were to help Black women recognise if they believed their sexual pain has been normalised and minimised, and understand reasons (i.e. culture-based, gendered, sexual scripts) why they refrain from disclosing sexual pain to their partners. Recognising the onus is not solely on Black women to mitigate their pain, we recommend Black women and their partners, who are typically first points of contact, learn about sexual pain together through online resources, books and consultation and treatment from culturally mindful medical professionals such as pelvic floor therapists. Research suggests racial differences in Black women’s descriptions of pain compared to White women’s reports (Brown et al. 2015); therefore, clinicians should be aware of the cultural scripts that influence Black women’s discomfort disclosing sexual pain and minimisation of painful sexual experiences. Culturally relevant resources about sexual pain can be tailored to unique genderedracial socialisation practices such as displaying strength and resisting vulnerability that hinder Black women’s willingness to engage in sexual communication with their partners.

Interventions designed to highlight and counter cultural messaging that normalises sexual pain can help to reduce fear-based thoughts and sexual self-consciousness among Black women (Thorpe et al. 2022). After gaining personal insight into their sexual pain, Black women can develop and utilise strategies such as assertive sexual communication, foreplay and masturbation and non-penetrative activities such as oral sex to reduce painful sex (Malone et al. 2021). Overall, disseminating information about ways to address sexual pain can reduce stigma and create spaces for Black women to disclose their sexual concerns.

Conclusion

This study filled a gap in the literature by exploring barriers to disclosing sexual pain to partners among Black women. Findings extended prior research by elucidating the intrapsychic, interpersonal and cultural barriers that Black women report as hindrances to their disclosure of sexual pain. Black women need not suffer from sexual pain in silence. Addressing Superwoman schema messaging, promoting open sexual communication, and encouraging partner support in solving problems of sexual pain can increase Black women’s sexual satisfaction and relational well-being.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank the women who participated in this study and shared their sexual experiences with us.

Funding

This study was partially funded by a Center for Positive Sexuality’s Race and Sexuality grant.

Footnotes

In this paper, we define sexual pain as “recurring unwanted pain that occurs during sexual intercourse” and use this concept to capture various types of genito-pelvic conditions, including vulvar pain.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Abrams JA, Hill A, and Maxwell M. 2019. “Underneath the Mask of the Strong Black Woman Schema: Disentangling Influences of Strength and Self-Silencing on Depressive Symptoms among US Black Women.” Sex Roles 80 (9–10):517–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hendy A, Myers ER, and Stewart E. 2017. “Uterine Fibroids: Burden and Unmet Medical Need.” Seminars in Reproductive Medicine 35 (6):473–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awada N, Bergeron S, Steben M, Hainault V-A, and McDuff P. 2014. “To Say Or Not To Say: Dyadic Ambivalence over Emotional Expression and Its Associations with Pain, Sexuality, and Distress in Couples Coping with Provoked Vestibulodynia.” The Journal of Sexual Medicine 11 (5):1271–1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayling K, and Ussher JM. 2008. “‘If Sex Hurts, Am I Still a Woman?’ The Subjective Experience of Vulvodynia in Hetero-Sexual Women.” Archives of Sexual Behavior 37 (2):294–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergeron S, Corsini-Munt S, Aerts L, Rancourt K, and Rosen NO. 2015. “Female Sexual Pain Disorders: A Review of The Literature on Etiology And Treatment.” Current Sexual Health Reports 7 (3):159–169. [Google Scholar]

- Blair KL, Pukall CF, Smith KB, and Cappell J. 2015. “Differential Associations of Communication and Love in Heterosexual, Lesbian, and Bisexual Women’s Perceptions and Experiences of Chronic Vulvar and Pelvic Pain.” Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy 41 (5):498–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L, Lucas KJ, and Tschann JM. 2004. “The Ball Was Always in His Court’: An Exploratory Analysis of Relationship Scripts, Sexual Scripts, and Condom Use among African American Women.” Psychology of Women Quarterly 28 (1):70–82. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, and Clarke V. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Brown CS, Foster DC, Bachour CC, Rawlinson LA, Wan JY, and Bachmann GA. 2015. “Presenting Symptoms Among Black And White Women With Provoked Vulvodynia.” Journal of Women’s Health (2002) 24 (10):831–836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter A, Ford JV, Luetke M, Fu T-CJ, Townes A, Hensel DJ, Dodge B, and Herbenick D. 2019. “‘Fulfilling His Needs, Not Mine’: Reasons for Not Talking About Painful Sex and Associations with Lack of Pleasure in a Nationally Representative Sample of Women in the United States.” The Journal of Sexual Medicine 16 (12):1953–1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Graaff AA, Van Lankveld J, Smits LJ, Van Beek JJ, and Dunselman GAJ. 2016. “Dyspareunia and Depressive Symptoms Are Associated with Impaired Sexual Functioning in Women with Endometriosis, Whereas Sexual Functioning in Their Male Partners Is Not Affected.” Human Reproduction 31 (11):2577–2586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding T, Hardiman PJ, Petersen I, Wang F-F, Qu F, and Baio G. 2017. “The Prevalence of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome in Reproductive-Aged Women of Different Ethnicity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Oncotarget 8 (56):96351–96358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogan J, Hargons C, Meiller C, Oluokun J, Montique C, and Malone N. 2018. “ Catchin’ Feelings: Experiences of Intimacy During Black College Students’ Sexual Encounters.” Journal of Black Sexuality and Relationships 5 (2):81–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson RL, and Meana M. 2011. “Early Dyspareunia Experience in Young Women: Confusion, Consequences, and Help-seeking Barriers.” The Journal of Sexual Medicine 8 (3):814–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekholm E, Lundberg T, Carlsson J, Norberg J, Linton SJ, and Flink IK. 2021. “‘A Lot To Fall Back On’: Experiences Of Dyspareunia Among Queer Women.” Psychology & Sexuality :1–14. doi: 10.1080/19419899.2021.2007988 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elmerstig E, Wijma B, and Swahnberg K. 2013. “Prioritizing the Partner’s Enjoyment: A Population-Based Study on Young Swedish Women with Experience of Pain During Vaginal Intercourse .” Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology 34 (2):82–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahs B. 2014. “Coming to power: Women’s Fake Orgasms and Best Orgasm Experiences Illuminate the Failures of (Hetero)Sex and the Pleasures of Connection.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 16 (8):974–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell J, and Cacchioni T. 2012. “The Medicalization of Women’s Sexual Pain.” Journal of Sex Research 49 (4):328–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasula AM, Carry M, and Miller KS. 2014. “A Multidimensional Framework for the Meanings of the Sexual Double Standard and Its Application for the Sexual Health of Young Black Women in the US.” Journal of Sex Research 51 (2):170–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French B. 2013. “More than Jezebels and Freaks: Exploring How Black Girls Navigate Sexual Coercion and Sexual Scripts.” Journal of African American Studies 17 (1):35–50. [Google Scholar]

- Harlow BL, and Stewart EG. 2003. “A Population-Based Assessment of Chronic Unexplained Vulvar Pain: Have We Underestimated the Prevalence of Vulvodynia?” Journal of the American Medical Women’s Association (1972) 58 (2):82–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargons CN, Dogan J, Malone N, Thorpe S, Mosley DV, and Stevens-Watkins D. 2021. “Balancing the Sexology Scales: A Content Analysis of Black women’s sexuality research.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 23 (9):1287–1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargons CN, Mosley DV, Meiller C, Stuck J, Kirkpatrick B, Adams C, and Angyal B. 2018. “It Feels So Good”: Pleasure In Last Sexual Encounter Narratives of Black University Students.” Journal of Black Psychology 44 (2):103–127. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman KM, Trawalter S, Axt JR, and Oliver MN. 2016. “Racial Bias in Pain Assessment and Treatment Recommendations, and False Beliefs about Biological Differences between Blacks and Whites.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113 (16):4296–4301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins-Hall W, and Tanner AE. 2016. “US Black College Women’s Sexual Health in Hookup Culture: Intersections of Race and Gender.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 18 (11):1265–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones AC, Robinson WD, and Seedall RB. 2018. “The Role of Sexual Communication in Couples’ Sexual Outcomes: A Dyadic Path Analysis.” Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 44 (4):606–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyama CM, Mwenda JM Machoki J Mihalyi A Simsa P Chai DCD, and Hooghe TM 2007. “Endometriosis in African Women.” Women’s Health 3 (5):629–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labuski CM 2017. “A Black and White Issue? Learning to See the Intersectional and Racialized Dimensions of Gynecological Pain.” Social Theory & Health 15 (2):160–181. [Google Scholar]

- Malone N, Thorpe S, Jester JK, Dogan JN, Stevens-Watkins D, and Hargons CN. 2021. “Pursuing Pleasure Despite Pain: A Mixed-Methods Investigation of Black Women’s Responses to Sexual Pain and Coping.” Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy 13:1–15. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2021.2012309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merwin KE, O’Sullivan LF, and Rosen NO. 2017. “We Need to Talk: Disclosure of Sexual Problems Is Associated with Depression, Sexual Functioning, and Relationship Satisfaction in Women.” Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy 43 (8):786–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meston CM, and Buss DM. 2007. “Why Humans Have Sex.” Archives of Sexual Behavior 36 (4):477–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, and Moules NJ. 2017. “Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 16 (1):160940691773384. [Google Scholar]

- Pazmany E, Bergeron S, Verhaeghe J, Van Oudenhove L, and Enzlin P. 2015. “Dyadic Sexual Communication in Pre-menopausal Women with Self-reported Dyspareunia and their Partners: Associations with Sexual Function, Sexual Distress and Dyadic Adjustment .” The Journal of Sexual Medicine 12 (2):516–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rancourt KM, Flynn M, Bergeron S, and Rosen NO. 2017. “It Takes Two: Sexual Communication Patterns and the Sexual and Relational Adjustment of Couples Coping with Provoked Vestibulodynia.” The Journal of Sexual Medicine 14 (3):434–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rancourt KM, Rosen NO, Bergeron S, and Nealis LJ. 2016. “Talking about Sex When Sex Is Painful: Dyadic Sexual Communication Is Associated with Women’s Pain, and Couples’ Sexual and Psychological Outcomes in Provoked Vestibulodynia.” Archives of Sexual Behavior 45 (8):1933–1944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reissing ED, Binik YM, Khalifé S, Cohen D, and Amsel R. 2003. “Etiological Correlates of Vaginismus: Sexual and Physical Abuse, Sexual Knowledge, Sexual Self-Schema, and Relationship Adjustment.” Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy 29 (1):47–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose T. 2003. Longing to Tell: Black Women Talk about Sexuality and Intimacy. New York: Picador, Farrar, Straus and Giroux. [Google Scholar]

- Sacks TK 2018. Invisible Visits: Black Middle-Class Women in the American Healthcare System. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sadownik LA, Smith KB, Hui A, and Brotto LA. 2017. “The Impact of a Woman’s Dyspareunia and Its Treatment on Her Intimate Partner: A Qualitative Analysis.” Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy 43 (6):529–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon W, and Gagnon JH. 1986. “Sexual Scripts: Permanence and Change.” Archives of Sexual Behavior 15 (2):97–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas EJ, Stelzl M, and Lafrance MN. 2017. “Faking to Finish: Women’s Accounts of Feigning Sexual Pleasure to End Unwanted Sex.” Sexualities 20 (3):281–301. [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe S, Dogan JN, Malone N, Jester JK, Hargons CN, and Stevens-Watkins D. 2022. “Correlates of Sexual Self-Consciousness Among Black Women.” Sexuality & Culture 26 (2):707–728. [Google Scholar]

- Thomtén J, and Linton SJ. 2013. “A Psychological View of Sexual Pain among Women: Applying the Fear-Avoidance Model.” Women’s Health 9 (3):251–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townes A, Fu T, Herbenick D, and Carter A. 2019. “070 Painful Sex Among White and Black Women in the United States: Results from a Nationally Representative Study.” The Journal of Sexual Medicine 16 (6):S26. [Google Scholar]

- Townes A, Rosenberg M, Guerra-Reyes L, Murray M, and Herbenick D. 2020. “Inequitable Experiences Between Black and White Women Discussing Sexual Health with Healthcare Providers: Findings from a US Probability Sample.” The Journal of Sexual Medicine 17 (8):1520–1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward LM 2002. “Does Television Exposure Affect Emerging Adults’ Attitudes And Assumptions About Sexual Relationships? Correlational and Experimental Confirmation.” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 31 (1):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Woods-Giscombé CL 2010. “Superwoman Schema: African American women’s views on stress, strength, and health.” Qualitative Health Research 20 (5):668–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods-Giscombe CL, Allen AM, Black AR, Steed TC, Li Y, and Lackey C. 2019. “The Giscombe Superwoman Schema Questionnaire: Psychometric Properties and Associations with Mental Health and Health Behaviors in African American Women.” Issues in Mental Health Nursing 40 (8):672–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]