The policies pursued by the Soviet Union and its satellites in central and eastern Europe have had profound implications for health.1,2 By 1990 the probability of people dying before the age of 65 in the Soviet Union was twice that for western Europe, and for the communist countries of central and eastern Europe it was 70% higher compared with western Europe.3

Men were especially susceptible to dying prematurely. Although men in all industrialised countries live shorter lives than women, in the Soviet Union the gap between the sexes was especially large. In 1990 the life expectancy of men living in the Soviet Union was only 64 years—nine years less than in western Europe. Soviet women could expect to live to 74 years—10 years longer than men and only six years less than women in western Europe. The disadvantage in life expectancy relative to western Europe was less for countries of central and eastern Europe, but even there the gap was six years for men and five years for women. The travel writer Colin Thubron, after meeting an old woman in a village in western Siberia, observed for himself the reality that “in her experience, men died young.”4

Summary points

Young men were especially vulnerable to the consequences of the policies pursued by the communist regimes in eastern Europe before 1990

The leading causes of the high mortality were injuries and violence and cardiovascular diseases

High levels of alcohol consumption, especially binge drinking, were an important underlying factor, but smoking and poor nutrition also played a part

Men who have experienced a rapid economic transition, who have least educational resources and least social support have been affected the most

The pattern of premature mortality seen among men in eastern Europe is not unique and there are many parallels among disadvantaged communities in western Europe

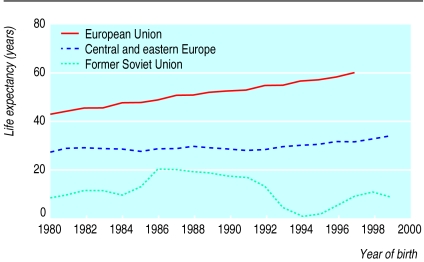

Understanding why men die

The present review draws on mortality data supplied by the World Health Organization and on the findings of a collaborative programme of research on health in central and eastern Europe.5 Mortality was higher in eastern Europe than in western Europe for men and women alike, suggesting that some factors contributing to death were common to both sexes, whereas other factors especially disadvantaged men. Considerable national diversity was also evident. For example, the life expectancy of men was lower in countries of the former Soviet Union than in the other Soviet block countries of central and eastern Europe (fig 1).3 A further division separates countries in central and eastern Europe that have seen marked improvements in health, such as Poland and the Czech Republic, from those that have not, such as Romania and Bulgaria. Similarly, in the former Soviet Union there are differences between the republics of Europe and central Asia.1

Figure 1.

Life expectancy of men in Europe3

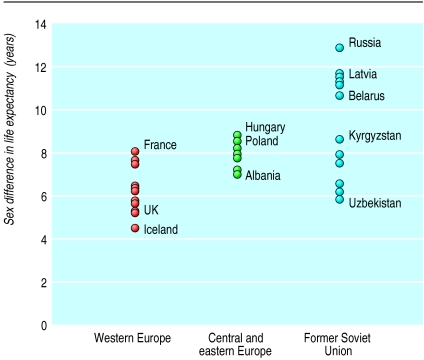

The variation between countries regarding the difference in life expectancy between men and women is shown in figure 2.3 A disadvantage for men, although more common in eastern Europe, is not unique to that region. Indeed, the eight year sex difference in France exceeds that of many central European countries. Sex differences in life expectancy are especially large in Poland, Hungary, Russia, and the European post-Soviet republics. In other countries, especially those in the southern part of the region or in central Asia, the difference is similar to that in western Europe. Interestingly, the sex difference in some western countries has narrowed since the early 1990s and reflects, predominantly, a rising level of smoking related mortality among women.6 Similarly, in some central Asian countries, it reflects a particularly low level of health among women, especially in rural areas.7

Figure 2.

Sex difference in life expectancy at birth in Europe (women−men).3 Named countries show top and bottom of ranges and several other examples

Immediate causes

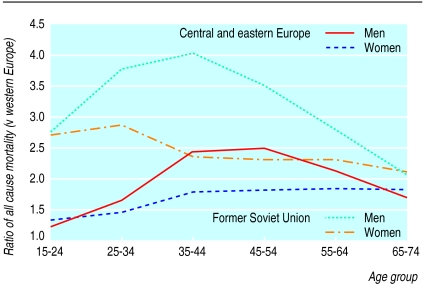

Some clues as to why men have shorter lives than women can be found from the age distribution of mortality in men. Mortality relative to western Europe is highest in the age group 35-44 years (fig 3). Many factors contribute to this peak but injuries, violence, and cardiovascular diseases make the greatest impact. Deaths in this age group, and deaths from these three causes of death, have also been extremely important in explaining the changes in overall mortality associated with the transition to democracy.8,9

Figure 3.

Ratio of age specific all cause mortality in men in central and eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union to mortality in the European Union, 1997. Source: WHO3

Injuries and violence

By 1997 mortality from all external causes in men before the age of 65 was five times higher in the countries of the former Soviet Union than in western Europe; in central and eastern Europe it was double that in western Europe. All causes of injury are more common in the former Soviet Union than in western Europe. For road traffic accidents, however, the difference between the two regions (50% higher in the Soviet Union) is small compared with the 3.4-fold difference for suicide and 19-fold difference for homicide.3 Other common causes of death in the former Soviet Union include drowning and deaths in fires.

Unfortunately, injuries and violence have received relatively little attention from policymakers in central and eastern Europe,10 and many factors underlie the high levels of injuries in this region.11 One factor is that these countries lack many of the design features promoting safety that are found in western Europe, such as adequate lighting and enforcement of regulations on building and equipment. Another is the weakness in the healthcare system, including poor communications, especially in rural areas, resulting in slow responses of ambulances to emergency calls. Trauma care is often of poor quality.

A key contributing factor to the high level of injuries and violence is the large consumption of alcohol. In Russia, the number of deaths from external causes closely reflects the number of deaths from alcohol poisoning, both geographically and over time.9,12 Many men who commit suicide show evidence of intoxication, and intoxication of at least one of the parties involved in a homicide is almost universal.13

Cardiovascular disease

Mortality due to cardiovascular disease is greatest, relative to western Europe, in the age group 35-44. Cardiovascular disease is understood differently in Russia, in several important aspects, than in western Europe. Thus, mortality for cardiovascular disease is especially high at young ages. Deaths are also more likely to be sudden,14 and many people who die show little evidence of the expected coronary artery lesions.15 The traditional risk factors identified in western epidemiological research, such as smoking, lipid levels, and physical activity, have little predictive value.16 Indeed, lipid metabolism appears to differ in Russians and Americans.17 Instead there is growing evidence that other factors are involved. Eastern European diets, for example, are characterised not only by large amounts of fat but also by very low quantities of fruit and vegetables. Correspondingly, antioxidant activity in the blood is extremely low.18,19 The role of micronutrients in macrophage adhesion and passage of cholesterol through arterial walls provides a mechanism by which this could cause heart disease.20 The rapid reduction in cardiovascular deaths in some countries, coinciding with changes in diet, offers support for this hypothesis.21,22 Poor nutrition is thus likely to be important in explaining the overall difference in mortality compared with western Europe. Although there are some differences in the diets of men and women,23 the differential impact on health is likely to be small.

Another factor that contributes to increased mortality due to cardiac disease is alcohol. Across northern Europe, but especially in Russia and some of its neighbours, alcohol is typically drunk as vodka and in binges,24 in contrast to a more steady consumption in southern and western Europe. A possible link with cardiac death was suspected following the observation that deaths in Moscow from cardiovascular disease increased at weekends, a finding incompatible with the effects of the traditional risk factors.25 (This was later replicated in Scotland,26 indicating the wider implications of research in eastern Europe). Binge drinking is associated with a marked increase in the risk of cardiovascular death, and in particular sudden cardiac death,27 reflecting different physiological responses to binge drinking and regular moderate consumption.28 A third factor, although one whose role is less well defined, is the high level of psychosocial stress.29

Alcohol and tobacco

Injuries and cardiovascular diseases account for a large part of the difference in mortality between eastern and western Europe, but several other causes, although less important numerically, are much more frequent in eastern Europe than in western Europe. These include various causes directly or indirectly associated with alcohol consumption. Direct causes include acute alcohol poisoning and cirrhosis; indirect causes include conditions such as stroke30 and pneumonia.31 High mortality from injuries, cardiovascular deaths, and acute alcohol poisoning is seen in countries where the drinking culture favours vodka. These countries also tend to have relatively low mortality from cirrhosis, possibly because death from other causes occurs before cirrhosis can develop. In southern parts of the region, however, in particular in a band stretching from Slovenia to Moldova, the acute effects of alcohol are less apparent (with the exception of deaths from road traffic accidents), but deaths from cirrhosis are extremely common. The reason for this is unclear. One possible explanation is found in the pattern of drinking, with many heavy drinkers drinking from early morning. Another is a low level of dietary micronutrients from fruit and vegetables, which could otherwise provide some protective effect.

The health effects of tobacco also contribute to the difference in mortality in men between eastern and western Europe,32 although these health effects have had less impact on recent changes than have alcohol and nutrition. Caution is required, however, because the effects of smoking become apparent only after many years. Mortality from lung cancer is currently falling in many former Soviet countries, reflecting the fact that fewer men began smoking during the austere period of the late 1940s and early 1950s.33 This fall will, however, be short lived. Tobacco contributes substantially to the sex difference in mortality in eastern Europe, especially in the former Soviet Union, where mortality from lung cancer is almost nine times higher among men than women, compared with a difference of 4.5 times in western Europe. It has traditionally been uncommon for women of the former Soviet Union to smoke, although this is now changing rapidly in response to massive marketing efforts by western tobacco companies.34

Abstinence from alcohol and tobacco often characterises the religious beliefs of populations in which mortality in men and women is similar.35,36 This indicates that basic biological differences, although clearly important in the aetiology of many specific diseases, may not be the most important factor in determining excess mortality in men. That alcohol and tobacco might contribute to sex differences in mortality is intuitive because the use of both is closely related to gender in most societies. In western societies, women are adopting behaviour traditionally associated with men, such as high rates of smoking. This means that the sex difference in life expectancy is narrowing, primarily because of a break in the previously upward trend in female life expectancy.

Other causes

Finally, there are some specific conditions that, although not numerically as important as those discussed above, also impact disproportionately on men in this region. The most important is tuberculosis, with mortality from this disease being more than nine times among Russian men than among women. A major factor is the high level of transmission of the disease in prisons,37 which have a population predominantly consisting of men. Worryingly, the prevalence of HIV infection is also increasing rapidly and although it is not yet a major cause of premature mortality, it probably will be within a few years. The emergence of large numbers of people with compromised immune status will exacerbate the effects of other infections, in particular the increasing level of drug resistant tuberculosis.

Underlying factors

The preceding paragraphs discuss the contribution of lifestyle related factors to the burden of premature death in men. Lifestyle choices are, however, heavily influenced by social circumstances and they can only be understood fully by considering the context in which they are made.

Not all men have been affected equally by the communist system and the subsequent transition. In Russia, when overall mortality was increasing rapidly in the early 1990s, the greatest increases in mortality were in regions experiencing the most rapid economic transition, as measured by gains and losses in employment.12 Men with poor education were especially vulnerable to the changes. Indeed, mortality among Russian men who were well educated was similar to levels in western countries in the 1980s and early 1990s. Overall mortality was much higher among men with the least education, the difference between the two groups being primarily due to external causes and cardiovascular diseases.38 The sex difference in mortality was also widest for men with poor education. The link between alcohol and mortality is also evident here, given that the gradient in mortality in relation to levels of education was especially steep for causes directly related to alcohol consumption.39 Other research emphasises the importance of lack of control over one's life40 and low levels of social support. Watson has explored the reasons why men, and particularly those who were unmarried, were rendered especially vulnerable in communist societies.41 They were confronted with a relentless feeling of impotence in a hostile and unresponsive world, unlike women, who could find fulfilling roles within the home.42 Thus the increase in mortality in men in central and eastern Europe in the 1980s was greatest among unmarried men.43,44

These findings paint a picture of societies in which young and middle aged men face social and economic disruption on a large scale, for which they are poorly prepared. For many, their options are constrained by low levels of education, and the societies of which they are a part have few systems of social support. Poor nutrition and high rates of smoking have already reduced their chances of a long life. The availability of cheap alcohol, however, provides a pathway not only to oblivion but often to premature death. To be drunk anywhere can be dangerous, but especially so in a society in which there are few people on whom one can depend and where many elements of the environment present lethal hazards. The dangers are exacerbated by an unwillingness by society to challenge a high level of violence.

Wider implications

The burden of premature mortality in men in the former communist countries stands out on account of its magnitude, but this phenomenon is not unique. In several western countries mortality among young men is rising. Mortality is driven to a considerable extent by injuries and other alcohol related causes, with the additional effect of AIDS.45,46 Elements of the pattern of premature mortality in eastern Europe can also be seen in certain disadvantaged minorities in otherwise affluent countries. Examples include native and African Americans and Australian aborigines. The east-west gradients in mortality from different causes and the social class gradient in the United Kingdom are strikingly similar.47

There are also millions of men in developing and middle income countries whose deaths are never recorded. The few studies that have provided insight into their lives suggest that they too face high levels of adult mortality.48,49 Those studies are important but are an inadequate substitute for the effective systems of vital statistics that will be needed to make their plight visible.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Naomi Fulop for helpful comments on an earlier draft and to Remis Prokhorskas for supplying age specific mortality data.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Forster DP, Jozan P. Health in Eastern Europe. Lancet. 1990;335:458–460. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90678-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKee M. The health effects of the collapse of the Soviet Union. In: Leon D, Walt G, editors. Poverty, inequality and health. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2001. pp. 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Health for All database. Copenhagen: WHO; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thubron C. In Siberia. London: Chatto & Windus; 1999. p. 29. [Google Scholar]

- 5.ECOHOST. www.lshtm.ac.uk/centres/ecohost/ (accessed 10 May 2001).

- 6.Waldron I. Recent trends in sex mortality ratios for adults in developed countries. Soc Sci Med. 1993;36:451–462. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90407-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McKee M, Chenet L. Patterns of health. In: McKee M, Healy J, Falkingham J, eds. Health care in Central Asia. Buckingham: Open University press (in press).

- 8.Leon D, Chenet L, Shkolnikov VM, Zakharov S, Shapiro J, Rakhmanova G, et al. Huge variation in Russian mortality rates 1984-1994: artefact, alcohol, or what? Lancet. 1997;350:383–388. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)03360-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shkolnikov V, McKee M, Leon DA. Changes in life expectancy in Russia in the 1990s. Lancet. 2001;357:917–921. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04212-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McKee M, Zwi A, Koupilová I, Sethi D, Leon D. Health policy-making in central and eastern Europe: lessons from the inaction on injuries? Health Policy Plan. 2000;15:263–269. doi: 10.1093/heapol/15.3.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.ECOHOST. Childhood injuries: a priority area for the transition countries of central and eastern Europe and the newly independent states. London: London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walberg P, McKee M, Shkolnikov V, Chenet L, Leon DA. Economic change, crime, and mortality crisis in Russia: a regional analysis. BMJ. 1998;317:312–318. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7154.312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shkolnikov VM, Chervyakov VV. Policies for the control of the transition's mortality crisis. Moscow: United Nations Development Programme; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laks T, Tuomilehto J, Joeste E, Maeots E, Salomaa V, Palomaki P, et al. Alarmingly high occurrence and case fatality of acute coronary heart disease events in Estonia: results from the Tallinn AMI register 1991-94. J Intern Med. 1999;246:53–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1999.00505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vikhert AM, Tsiplenkova VG, Cherpachenko NM. Alcoholic cardiomyopathy and sudden cardiac death. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986;8:3A–11A. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(86)80023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perova NV, Oganov RG, Williams DH, Irving SH, Abernathy JR, Deev AD, et al. Association of high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol with mortality and other risk factors for major chronic noncommunicable diseases in samples of US and Russian men. Ann Epidemiol. 1995;5:179–185. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(94)00104-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shakhov YA, Oram JF, Perova NV, Alexandri AL, Kolpakova GV, Marcovina S, et al. Comparative study of the activity and composition of HDL3 in Russian and American men. Arterioscler Thromb. 1993;13:1770–1778. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.13.12.1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kristenson M, Zieden B, Kucinskiene Z, Elinder LS, Bergdahl B, Elwing B, et al. Antioxidant state and mortality from coronary heart disease in Lithuanian and Swedish men: concomitant cross sectional study of men aged 50. BMJ. 1997;314:629–633. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7081.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bobak M, Brunner E, Miller NJ, Skodova Z, Marmot M. Could antioxidants play a role in high rates of coronary heart disease in the Czech Republic? Eur J Clin Nutr. 1998;52:632–636. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chambers JC, Seddon MDI, Shah S, Kooner JS. Homocysteine—a novel risk factor for vascular disease. J Roy Soc Med. 2001;94:10–13. doi: 10.1177/014107680109400103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zatonski WA, McMichael AJ, Powles JW. Ecological study of reasons for sharp decline in mortality from ischaemic heart disease in Poland since 1991. BMJ. 1998;316:1047–1051. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7137.1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bobak M, Skodova Z, Pisa Z, Poledne R, Marmot M. Political changes and trends in cardiovascular risk factors in the Czech Republic, 1985-92. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1997;51:272–277. doi: 10.1136/jech.51.3.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pomerleau J, McKee M, Robertson A, Kadziauskiene K, Abaravicius A, Vaask S, et al. Macronutrient and food intake in the Baltic Republics. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2001;55:200–207. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bobak M, McKee M, Rose R, Marmot M. Alcohol consumption in a national sample of the Russian population. Addiction. 1999;94:857–866. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.9468579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chenet L, McKee M, Leon D, Shkolnikov V, Vassin S. Alcohol and cardiovascular mortality in Moscow, new evidence of a causal association. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52:772–774. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.12.772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Evans C, Chalmers J, Capewell S, Redpath A, Finlayson A, Boyd J, et al. “I don't like Mondays”—day of the week of coronary heart disease deaths in Scotland: study of routinely collected data. BMJ. 2000;320:218–219. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7229.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Britton A, McKee M. The relationship between alcohol and cardiovascular disease in Eastern Europe: explaining the paradox. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2000;54:328–332. doi: 10.1136/jech.54.5.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McKee M, Britton A. The positive relationship between alcohol and heart disease in eastern Europe: potential physiological mechanisms. J Roy Soc Med. 1998;91:402–407. doi: 10.1177/014107689809100802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bobak M, Marmot M. East-West mortality divide and its potential explanations: proposed research agenda. BMJ. 1996;312:421–425. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7028.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Gijn J, Stampfer MJ, Wolfe C, Algra A. The association between alcohol and stroke. In: Vershuren PM, editor. Health issues related to alcohol consumption. Brussels: International Life Sciences Institute Europe; 1993. pp. 43–79. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmidt W, Popham RE. The role of drinking and smoking in mortality from cancer and other causes in male alcoholics. Cancer. 1981;47:1031–1041. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810301)47:5<1031::aid-cncr2820470534>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peto R, Lopez AD, Boreham J, Thun M, Heath C. Mortality from smoking in developed countries 1950-2000. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shkolnikov V, McKee M, Leon D, Chenet L. Why is the death rate from lung cancer falling in the Russian Federation? Eur J Epidemiol. 1999;15:203–206. doi: 10.1023/a:1007546800982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McKee M, Bobak M, Rose R, Shkolnikov V, Chenet L, Leon D. Patterns of smoking in Russia. Tob Control. 1998;7:22–26. doi: 10.1136/tc.7.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leviatan U, Cohen J. Gender differences in life expectancy among kibbutz members. Soc Sci Med. 1985;21:545–551. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(85)90039-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jedrychowski W, Tobiasz-Adamczyk B, Olma A, Gradzikiewicz P. Survival rates among Seventh Day Adventists compared with the general population in Poland. Scand J Soc Med. 1985;13:49–52. doi: 10.1177/140349488501300201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stern V. Sentenced to die. the problem of TB in prisons in Eastern Europe and central Asia. London: International Centre for Prison Studies, King's College London; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shkolnikov VM, Leon D, Adamets S, Andreev E, Deev A. Educational level and adult mortality in Russia: an analysis of routine data 1979 to 1994. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47:357–369. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00096-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chenet L, Leon D, McKee M, Vassin S. Death from alcohol and violence in Moscow: Socio-economic determinants. Eur J Population. 1998;14:19–37. doi: 10.1023/a:1006012620847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bobak M, Pikhart H, Hertzman C, Rose R, Marmot M. Socioeconomic factors, perceived control and self-reported health in Russia. A cross-sectional survey. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47:269–279. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00095-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Watson P. Marriage and mortality in eastern Europe. In: Hertzman C, Kelly S, Bobak M, editors. East-West life expectancy gap in Europe: environmental and non-environmental determinants. Dordrecht: Kluwer; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rose R. Russia as an hour-glass society: a constitution without citizens. East European Constitutional Review. 1995;4:34–42. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hajdu P, McKee M, Bojan F. Changes in premature mortality differentials by marital status in Hungary and in England and Wales. Eur J Public Health. 1995;5:259–264. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Watson P. Explaining rising mortality among men in Eastern Europe. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41:923–934. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00405-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chenet L, McKee M, Otero A, Ausin I. What happened to life expectancy in Spain in the 1980s? J Epidemiol Community Health. 1997;51:510–514. doi: 10.1136/jech.51.5.510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ngongo KN, Nante N, Chenet L, McKee M. What has contributed to changing life expectancy in Italy in 1980-1992? Health Policy. 1999;48:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(99)00029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leon DA. Common threads: underlying components of inequalities in mortality between and within countries. In: Leon D, Walt G, editors. Poverty, inequality and health. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2001. pp. 58–87. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sibai AM, Fletcher A, Hills M, Campbell O. Non-communicable disease mortality rates using the verbal autopsy in a cohort of middle aged and older populations in Beirut during wartime, 1983-93. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001;55:271–276. doi: 10.1136/jech.55.4.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kitange HM, Machibya H, Black J, Mtasiwa DM, Masuki G, Whiting D, et al. Outlook for survivors of childhood in sub-Saharan Africa: adult mortality in Tanzania. Adult Morbidity and Mortality Project. BMJ. 1996;312:216–220. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7025.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]