Abstract

There is a critical need to understand the effectiveness of serum elicited by different SARS-CoV-2 vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 variants. We describe the generation of reference reagents comprised of post-vaccination sera from recipients of different primary vaccines with or without different vaccine booster regimens in order to allow standardized characterization of SARS-CoV-2 neutralization in vitro. We prepared and pooled serum obtained from donors who received a either primary vaccine series alone, or a vaccination strategy that included primary and boosted immunization using available SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines (BNT162b2, Pfizer and mRNA-1273, Moderna), replication-incompetent adenovirus type 26 vaccine (Ad26.COV2.S, Johnson and Johnson), or recombinant baculovirus-expressed spike protein in a nanoparticle vaccine plus Matrix-M adjuvant (NVX-CoV2373, Novavax). No subjects had a history of clinical SARS-CoV-2 infection, and sera were screened with confirmation that there were no nucleocapsid antibodies detected to suggest natural infection. Twice frozen sera were aliquoted, and serum antibodies were characterized for SARS-CoV-2 spike protein binding (estimated WHO antibody binding units/ml), spike protein competition for ACE-2 binding, and SARS-CoV-2 spike protein pseudotyped lentivirus transduction. These reagents are available for distribution to the research community (BEI Resources), and should allow the direct comparison of antibody neutralization results between different laboratories. Further, these sera are an important tool to evaluate the functional neutralization activity of vaccine-induced antibodies against emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, vaccine, reference reagent, antibodies

INTRODUCTION

RNA viruses, including the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), have error-prone polymerases that result in high rates of genome mutation (1, 2). This results in progeny virus genomes that differ from their parental templates, leading to the generation of viral quasispecies within and between individuals (3). The rapid and ongoing spread of SARS-CoV-2 has led to the evolution of variants of concern (VOC) that contain genome mutations, including the gene that encodes the spike protein that mediates viral entry. These mutations may lead to enhanced transmissibility and new waves of infections (4), as seen with the Delta and Omicron VOC (5–8). Among VOC, a critical issue is their potential for altered pathogenicity and immune escape from naturally occurring or vaccine-induced antibodies (9).

As new SARS-CoV-2 variants emerge, there is an urgent need to understand the relative effectiveness of antibodies elicited by different SARS-CoV-2 vaccines to neutralize VOC replication. Post-vaccination serum is a critical tool for the study of antibodies that neutralize naturally occurring SARS-CoV-2 viral variants in live virus or model system assays such as pseudotyped virus assays. The availability of reference serum reagents obtained from vaccinated individuals, and produced in volumes large enough to allow distribution, is an important tool needed for in vitro characterization of antibody activity elicited by different vaccines. In addition to VOC characterization, these reagents serve as a general reference standard to permit comparison of results across laboratories allowing interpretation of study outcomes generated via neutralization and/or spike protein binding antibody assays between laboratories.

Efforts to source and generate reagents for continued assessment of SARS-CoV-2 evolution and track resistance have been championed by the Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines (ACTIV) Tracking Resistance and Coronavirus Evolution (TRACE) initiative (https://www.nih.gov/research-training/medical-research-initiatives/activ/tracking-resistance-coronavirus-evolution-trace). The ACTIV public-private partnership programs led by the National Institutes of Health and facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health focus on the identification of emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants, the evaluation of therapeutic and vaccine resistance, and the assessment of how genetic variation alters viral biology and impacts clinical approaches of disease prevention and treatment. The infrastructure and processes developed by ACTIV TRACE allow for SARS-CoV-2 variant monitoring and data sharing through five steps, including the monitoring of global emergence and circulation of viral mutations, providing a cross-reference of sequence data against experimental or clinical viral variant databases, characterization of prioritized variants in vitro using critical-path assays, and sharing these data in a rapid, open manner. An integral part of the ACTIV TRACE working group mission is to assess therapeutic efficacy in vitro, generating standardized protocols, reference reagents, and datasets to facilitate greater understanding of VOC impact on vaccine and therapeutic efficacy. Dissemination of SARS-CoV-2 datasets and preclinical assay overviews are freely available through the National Center for Advancing Translation Sciences (NCATS) Variant Therapeutic Data Summary (10) (https://opendata.ncats.nih.gov/covid19) and reagents are distributed via collaboration with BEI Resources.

Here, we report the generation of pooled, large volume reference sera reagents obtained from individuals who received primary immunization with one of four COVID-19 vaccines, or who received booster vaccination following their primary series. Donors include recipients of the two SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines (BNT162b2, Pfizer and mRNA-1273, Moderna), a replication-incompetent human adenovirus type 26 vaccine (Ad26.COV2.S, Johnson & Johnson), and a recombinant trimeric spike protein expressed by baculovirus and incorporated into a nanoparticle vaccine plus Matrix-M adjuvant (NVX-CoV2373, Novavax). Donors had no evidence of prior infection based on history and nucleocapsid antibody testing, and passed screening tests required for blood donation. The pools of reference serum have been aliquoted and are available through BEI Resources (https://www.beiresources.org/Home.aspx).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects and serum collection

All subjects were enrolled following written informed consent. The study was approved by the University of Iowa Institutional Review Board (IRB, Committee A). Vaccinated subjects with no history of SARS-CoV-2 infection, who lacked detectable antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid but had antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 spike protein were recruited for a study of T cell responses to SARS-CoV-2. A medical history, whole blood, and peripheral blood mononuclear cells were obtained and processed as described (11). Subjects provided consent to havin their blood used for research studies involving viruses (specifically including but not limited to SARS-CoV-2, HIV, and GB virus type C), and to the release of de-identified materials to the research community. Volunteers who expressed interest were evaluated for blood donation at the Impact Life Blood Services (Coralville, IA). Following a second written informed consent process, each eligible donor donated one unit (~ 500 mL) of whole blood, which was collected into a “dry” bag without anticoagulant. Each unit was allowed to clot at room temperature for ≥ 4 hours, following which approximately 250 ml serum was recovered from each donor and transferred into a separate bag without anticoagulant. Each serum product was frozen at ≤ −20°C, and units from each vaccine recipient group were shipped together overnight to BEI Resources on frozen packs. Upon receipt, sera remained partially frozen. The sera were allowed to thaw before being pooled and stored in 1 mL (or 25 mL) labeled tubes for distribution by BEI. Pooled serum aliquots were frozen and stored at −20°C for subsequent distribution. Sera were not heat-inactivated.

Laboratory methods

Samples from each study volunteer and each pooled serum preparation were evaluated for spike antibody using the LIASON® SARS-CoV-2 S1/S2 IgG assays (Roche Cobas, Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland) at the University of Iowa Pathology Laboratory and nucleocapsid antibodies using either quantitative ELISA (IEQ-CoVN-IgG, IgM, RayBiotech, Peachtree, GA) for the sera obtained following primary vaccination as recommended by the manufacturer, or by the Elecsys Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Antibody Assay (Roche Diagnostics, Basel Switzerland) for those sera obtained following booster vaccination (12, 13). All samples were run in technical replicates. Roche anti-S antibody quantification (U/mL) were converted to estimated World Health Organization IU/mL using the formula recommended by Lukaszuk et al. (Roche U/ml / 0.972) (14).

The SARS-CoV-2 spike protein receptor binding domain (RBD) contains a receptor binding motif that interacts with angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) on the cell surface (15). Antibodies that block RBD binding to cell ACE2 correlate with neutralizing antibodies (15). Serum inhibition of RBD binding to ACE2 was measured using a SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD-ACE2 blocking antibody detection ELISA kit (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvars, MA) as recommended by the manufacturer (16).

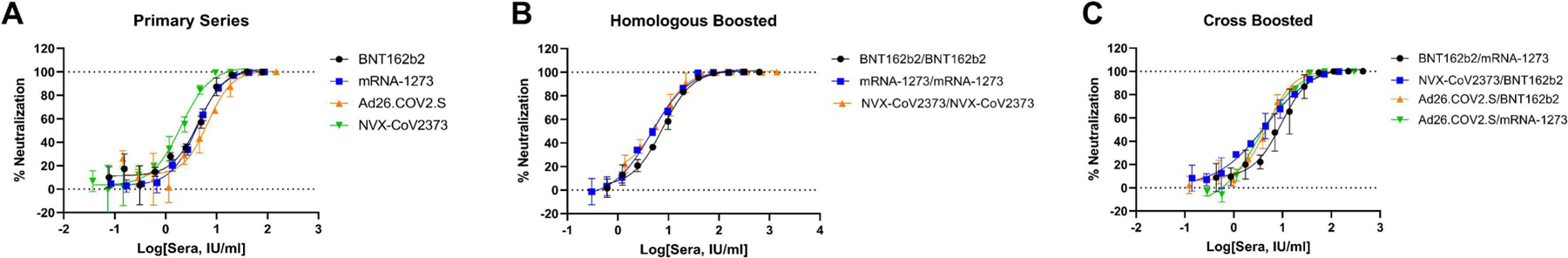

The SARS-CoV-2 spike protein pseudotyped virus (PV) neutralization assay was conducted as previously reported (17). Briefly, HEK293-ACE2-TMPRSS2 cells (18) were seeded at 6000 cells/well in 15 μl media (DMEM, 10% FBS, 1x L-glutamine, 1x P/S) in 384-well assay plates (Greiner #781073), and allowed to attach overnight at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Pooled sera were serially diluted 1:2 in media, then added to assay wells at 2 μl/well, and incubated for 1 hr at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Following that, 15 μl/well of SARS-CoV-2-S PV at 1:500 titration in media was added. SARS-CoV-2-S PV was prepared by Nexelis (Quebec, Canada) using an rVSV-ΔG-Luciferase system (Kerafast, Boston, MA), and pseudotyped with SARS-CoV-2 spike protein (Wuhan-Hu-1 sequence) with a C-terminal 19 amino acid deletion. PV-containing assay plates were spin-inoculated at 453 x g for 45 min at room temperature, then incubated for 24 hr at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Following supernatants removal using a Blue Washer (BlueCat Bio, Concord, MA), 20 μl/well of Bright-Glo Luciferase detection reagent (Promega #E2620) was dispensed to the assay plates, incubated for 5 min at room temperature, and luminescence was measured on a ViewLux Plate Reader (PerkinElmer, Ontario, Canada). Each sera was tested at 11-point 1:2 titrations with 3 biological replicates per experiment, in 3 separate experiments. All data was normalized with wells containing SARS-CoV-2-S PV only as 0% neutralization, and no PV control wells as 100% neutralization. Normalized data from the 3 biological replicates were used for dose response curve fitting (GraphPad Prism) to calculate EC50 and efficacy (% neutralization) (Table 2, Figure 1). Cytotoxicity was measured using an ATP content assay with the same protocol except media was added in lieu of PV.

Table 2.

Immunologic characterization of Serum Pools

| Primary Vaccine | Boost | Days post-final vaccine | Anti-S Ab* | Anti-Nucleocapsid Ab | RBD blocking IC90 | Neutralization EC50 (IU/ml) EC50 (IU/ml) EC50 (IU/ml) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BNT162b2 | 69 | 1,312 | Neg | 60 | 5.01 | 4.47 | 5.01 | |

| mRNA-1273 | 102 | 1,447 | Neg | 64 | 5.01 | 3.98 | 5.01 | |

| Ad26.COV2.S | 83 | 1,936 | Neg | 118 | 5.01 | 6.31 | 3.16 | |

| NVX-CoV2373 | 152† | 605 | Neg | 46 | 2.00 | 2.82 | 1.41 | |

| BNT162b2 | BNT152b2 | 63 | 10,062 | Neg | 6.6 × 104 | 8.91 | 7.94 | 10.00 |

| mRNA-1273 | mRNA-1273 | 89 | 4,959 | Neg | 1.1 × 106 | 4.47 | 5.01 | 3.55 |

| NVX-CoV2373 | NVX-CoV2373 | 46 | 22,572 | Neg | 2.5 × 106 | 6.31 | 3.55 | 7.94 |

| BNT162b2 | mRNA-1273 | 55 | 7,140 | Neg | 6.6 × 104 | 10.00 | 12.59 | 8.91 |

| NVX-CoV2373 | BNT162.b2 | 43 | 45,720 | Neg | 2.2 × 106 | 4.47 | 3.16 | 4.47 |

| Ad26.COV2. S | BNT162.b 2 | 178 | 2,014 | Neg | 4.3 × 104 | 3.98 | 3.98 | 5.01 |

| Ad26.COV2. S | mRNA-1273 | 126 | 9,342 | Neg | 1.4 × 106 | 3.98 | 6.31 | 3.16 |

Anti-S = anti-spike protein binding antibody,

W.H.O. IU/mL estimated (see text). ELISA,

NVX-CoV2373 in blinded clinical trial, result is estimated (see text). RBD = reciprocal of the serum dilution required to reduce receptor binding to ACE-2 by 90%. Data represent the results of experiments performed in triplicate

Figure 1.

Pseudotyped virus (PV) neutralization concentration-response of (A) primary series sera, (B) boosted sera, and (C) cross-boosted sera. Data points show mean +/− standard deviation calculated from n=3 biological replicates. Raw data was normalized with wells containing SARS-CoV-2-S PV as 0% and wells without PV as 100% neutralization.

RESULTS

Study Subject Characteristics

One hundred fifty two subjects were evaluated at the Iowa City VA or the University of Iowa. All volunteers were healthy, between 18 and 68 years of age, 99 (65%) were female, 52 (34%) male, and 1 was a transgender female. The average age was 47 or 54 years for women and men, respectively. Consistent with local demographics, 5 subjects were African American, 6 were Asian/Pacific Islander, and the remaining 141 were Caucasian, six of whom were Latino ethnicity. No volunteers had a clinical history of COVID-19. The primary vaccination that the majority of subjects received was BNT162b2 (n=57), followed by mRNA-1273 (n=40), NVX-CoV2373 (n=37), and Ad26.COV2.S (n=18). Two subjects had not received vaccination upon screening.

One hundred seven subjects were excluded from participation in the large volume serum donation study for the following reasons: 29 were not interested in blood donation, 44 had baseline nucleocapsid antibodies detected indicating prior infection, 2 had not received COVID-19 vaccines, 7 were excluded due to failure to meet blood donation screening requirements, 1 was unable to complete donation, and 24 were excluded due to relatively low SARS-CoV-2 spike antibody levels (< 160 WHO IU/mL following primary vaccination, < 1,000 WHO IU/mL following booster vaccination). The remaining 45 subjects donated 1 unit of whole blood for serum preparation between June 23, 2021 and December 20, 2021 for primary vaccination groups and February 2, 2022 and April 8, 2022 for booster vaccination groups. All donors tested negative for Syphilis MHA-TP, HIV-1/2/group O antibody, HIV-1/2-group O RT-PCR, HCV RT-PCR, HCV antibody, HBV RT-PCR, HBsAg, Anti-HB-core antibody, WNV RT-PCR, Zika virus RT-PCR, Babesia RT-PCR if from an endemic state, Trypanosoma cruzi antibody, and HTLV-1/2 antibody.

Demographic characteristics of the donors included in each serum pool are shown in Table 1. Six donors received BNT162b2, mRNA-1273, or Ad26.COV2.S vaccines, and 5 donors received NVX-CoV2373. The final volume of each pool was approximately 1.5 L for BNT162b2, mRNA-1273, or Ad26.COV2.S and 1.2 L for NVX-CoV2373. Women accounted for 4 out of 6 of the BNT162b2 and NVX-CoV2373 pools, and 2 out of 6 in the mRNA-1273 pool. One of 5 Ad26.COV2.S donors were female. The age of donors in each pool obtained following primary vaccination ranged from 37 to 52, and the timing of the two vaccine doses of primary immunization were similar (range 24 – 29 days, Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Serum Donors

| Prime | Boost | F / M | Age* | Days between doses† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BNT162b2 | None | 4 / 2 | 44 | 24 |

| mRNA-1273 | None | 2 / 4 | 52 | 29 |

| Ad26.COV2.S | None | 1 / 5 | 37 | NA |

| NVX-CoV2373 | None | 1 / 4 | 46 | 28 |

| BNT162b2 | BNT152b2 | 3 / 2 | 35 | 218 |

| BNT162b2 | mRNA-1273 | 2 / 0 | 47 | 173 |

| mRNA-1273 | mRNA-1273 | 3 / 2 | 51 | 121 |

| NVX-CoV2373 | NVX-CoV2373 | 4 / 1 | 40 | 99 |

| NVX-CoV2373 | BNT162.b2 | 1 / 1 | 47 | 123 |

| Ad26.COV2.S | BNT162.b2 | 0 / 1 | 43 | 247 |

| Ad26.COV2.S | mRNA-1273 | 0 / 1 | 36 | 146 |

F=female, M=male,

average age at time of donation,

average number of days between final dose and penultimate dose of vaccine, NA = not applicable, single vaccination.

In those who received booster doses, five received BNT162b2 primary and homologous boost, two received BNT162b2 primary and mRNA-1273 boost, five received mRNA-1273 primary and homologous boost, five subjects received NVX-CoV2373 primary and homologous boost, two received NVX-CoV2373 primary and BNT162b2 boost, one received Ad26.COV2.S primary with BNT162b2 boost and one received Ad26.COV2.S followed by mRNA-1273. The final volume of each pool was approximately 0.25 L times the number of donors for each group (e.g. 1.25 L for BNT162b2 primary and homologous boost). Women accounted for 24 of the 45 serum donors (53%), and the average age of donors at the time of donation ranged from 35 to 52. The interval between the last donation and previous donation ranged from 24–29 days in those donating following primary vaccination, and 99 to 247 days for those between the primary vaccination and booster dosing (Table 1).

Antibody Characteristics of Serum Pools

The average number of days following the final vaccination dose until blood donation varied between vaccines: 69 days for BNT162b2, 102 days for mRNA-1273, and 83 days for Ad26.COV2.S recipients. Since NVX-CoV2373 donors had participated in a double blind, placebo controlled, cross over trial, the time range of the vaccination was either January to March 2021 or April to June 2021. Subjects who reported post-vaccination reactions in April or May were estimated to have their second vaccine in May 2021. If the subject had no reaction following May 2021, or a reaction in January or February, the subjects were estimated to have their second vaccine during their February visit. Based on this, the estimated average time from second NVX-CoV2373 receipt was 152 days (Table 2). The interval between final vaccination and blood donation ranged from 46 to 178 days in those who received booster doses (Table 2).

Spike protein binding antibody titers ranged from 1276 to 1882 estimated WHO IU/mL for serum pools following primary immunization with BNT162b2, mRNA-1273, and Ad26.COV2.S recipients (Table 2), and did not correlate with the type of final vaccine received. The NVX-CoV2373 recipients had the lowest spike antibody titer (estimated WHO IU/ml of 604, Table 2), which likely reflects the significantly longer time period between receipt of the final vaccine and the timing of serum collection. In contrast, following the booster dose, the binding antibody titers ranged from 2,014 IU/mL to 45,720 IU/mL and titers appeared to be associated with the time to donation following the last vaccine dose (Table 2). Nucleoprotein-specific antibodies were not detected in any of the serum pools. Inhibition of RBD binding to ACE-2 reflected total spike antibody concentration and were approximately 10,000-fold greater in those who received booster doses (Table 2).

The ability of sera to neutralize entry of VSV pseudotyped with SARS-CoV-2-S into HEK293-ACE2-TMPRSS2 cells was assessed (Table 2). Representative concentration-response curves from one of the three experiments for each serum preparation is shown in Figure 1. ATP content cytotoxicity assays did not identify any cytotoxicity (data not shown). All sera showed full neutralization at highest concentrations tested. Differences between highest and lowest EC50s for each sera ranges from 1.1-fold to 2.2-fold, which indicates good day-to-day reproducibility. The pseudotyped virus (PV) neutralizing activities of different sera showed somewhat similar EC50s in terms of Spike binding antibody IU/ml values measured by the Elecsys Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Antibody Assay, with EC50s ranging from 2.0 IU/ml for NVX-CoV2373 primary series only to 10.0 IU/ml for BNT162b2 primary boosted with mRNA-1273.

DISCUSSION

Although post-infection, convalescent sera reference reagents have been generated and made accessible through the National Institute for Biological Standards and Control (NIBSC), to our knowledge the serum pools described herein are the first vaccine-specific reference reagents available for characterizing SARS-CoV-2 spike protein antibodies. Reference reagents are essential for rapid determination of vaccine-specific antibody binding and neutralization of emerging SARS-CoV-2 VOC. The vaccine-specific sera developed represent four vaccines approved for either use or for emergency use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. The large quantity of these reference serum pools should provide continuity for testing current and future SARS-CoV-2 variants and help ascertain if there are differences in binding or function of antibodies generated by different vaccine technologies.

The SARS-CoV-2 spike protein coding sequence for all four vaccines involved in this study are derived from the same ancestral virus (Wuhan-Hu-1 SARS-CoV-2) with minor differences employed in cloning (reviewed in (19). Specifically, all four vaccines contain 2 mutations that prevent the conformational change of the more immunogenic pre-fusion spike protein structure into the post-fusion form. Ad26.COV2.S also contains two mutations at the S1/S2 furin cleavage site, which further stabilizes the S protein in the pre-fusion state. The S protein in NVX-CoV2373 has all of the Ad26.COV2.S changes in addition to a deletion in the furin cleavage site. Further, NVX-CoV2373 trimeric (and multi-trimeric) proteins are expressed and purified before formulation as a nanoparticle, which includes a saponin-based adjuvant (Matrix-M™)(19). Due to the high degree of similarity in the spike protein across all four vaccines, differences in antibody responses presumably relate to either host genetic variation, the time interval between vaccination and serum collection, and/or differences in vaccine platform (20). Thus, examination of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced antibody binding to their cognate spike protein or neutralization of the Wuhan-Hu-1 strain provides avenues to evaluate different vaccine platforms. In addition, examination of vaccine-specific antibodies binding to emerging VOC spike proteins and the ability of these antibodies to neutralize VOC, allows for an in vitro surrogate to aid in predicting vaccine effectiveness, and the sera pools obtained following primary vaccination series have already been distributed by BEI and utilized for this purpose (21, 22).

These reference reagents provide an opportunity to compare results generated by different antibody binding, blocking, or neutralization assays across laboratories around the globe. A plethora of SARS-CoV-2 antibody methods have been developed for diagnostic and research purposes that utilize different platforms (ELISA, lateral flow immunoassays, chemiluminescent immunoassays, SARS-CoV-2 neutralization assays, spike protein pseudotyped neutralization assays, spike protein binding to ACE-2 inhibition, etc.) (23), and it is recognized that results obtained with one assay may vary considerably from that obtained by other laboratories, even when using the same methodology (24) . By making reference serum controls freely available, an improved understanding of the magnitude of the binding or neutralization measured should be gained, with ultimate improved harmonization of results between laboratories.

We foresee, on behalf of the ACTIV TRACE working group, the creation of additional pooled serum reference reagents. These reagents may include samples collected from other vaccination regimens (e.g. subjects who have received vaccine booster doses), vaccines involving variant spike protein sequences, or from post-infection convalescent serum with or without vaccination. As new reagents are made available, procedures, protocols, and characterizations will be made available. As a fundamental objective of the ACTIV TRACE initiative, we anticipate widespread distribution of the reagents described in this manuscript via BEI Resources (https://www.beiresources.org/Home.aspx). As reagent-related data are generated, they will be curated, summarized, and shared on the NCATS OpenData Portal (10), thus allowing for the comparison of assays across laboratories and informing on the reproducibility of the global research response to variants of SARS-CoV-2. Development and distribution of these reagents for investigative use against emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants is a driving factor for the ACTIV TRACE working group, as is the timely and open sharing of reagents, protocols, and data to further our understanding and to direct our therapeutic approaches against SARS-CoV-2 VOC as a scientific community.

IMPORTANCE.

The explosion of COVID-19 demonstrated how novel coronaviruses can rapidly spread and evolve following introduction into human hosts. The extent of vaccine- and infection-induced protection against infection and disease severity is reduced over time due to the fall in concentration, and due to emerging variants that have altered antibody binding regions on the viral envelope spike protein. Here, we pooled sera obtained from individuals who were immunized with different SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and who did not have clinical or serologic evidence of prior infection. The sera pools were characterized for direct spike protein binding, blockade of virus-receptor binding, and neutralization of spike protein pseudotyped lentiviruses. These sera pools were aliquoted and are available to allow inter-laboratory comparison of results and to provide a tool to determine the effectiveness of prior vaccines in recognizing and neutralizing emerging variants of concern.

ACKNOWLEGEMENTS

We thank Qing Chang and James McLinden, Ph.D. for helpful discussions, Michelle Rodenburg, Delilah Johnson, A.J. Carr, Shannon Micklewright, Susan Herman, Elizabeth Morgan, Deb Pfab, Angel Peguero (University of Iowa Vaccine Evaluation Unit), and Tara Dunahoo (Impact Life Blood Services) for assistance with subject recruitment, phlebotomy, and processing. We thank Crystal McClung, Anne Goodling and Gemma Spicka-Proffit at BEI Resources for coordinating shipments of the sera and aliquoting.

This work was supported by an intramural program at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, and the HHS Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) Countermeasures Acceleration Group (CAG). The work was also funded in part by the Veterans Administration Healthcare System by the VASEQCure program, and by a Veterans Administration Merit Review Grant (BX 000207, JTS), and with Federal funds from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under Contract No. HHSN272201600013C, managed by ATCC.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Footnotes

Part of this work was published as a preprint to expedite release of the reagents (medRxiv2022.01.24.22269773, doi https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.24.22269773)

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

COMPETING INTERESTS: The authors declare no competing interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Simmonds P, Domingo E. 2011. Virus evolution. Curr Opin Virol 1:410–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eckerle LD, Becker MM, Halpin RA, Li K, Venter E, Lu X, Scherbakova S, Graham RL, Baric RS, Stockwell TB, Spiro DJ, Denison MR. 2010. Infidelity of SARS-CoV Nsp14-exonuclease mutant virus replication is revealed by complete genome sequencing. PLoS Pathog 6:e1000896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Domingo E, Perales C. 2018. Quasispecies and virus. Eur Biophys J 47:443–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zeyaullah M, AlShahrani AM, Muzammil K, Ahmad I, Alam S, Khan WH, Ahmad R. 2021. COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2 Variants: Current Challenges and Health Concern. Front Genet 12:693916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dudas G, Hong SL, Potter BI, Calvignac-Spencer S, Niatou-Singa FS, Tombolomako TB, Fuh-Neba T, Vickos U, Ulrich M, Leendertz FH, Khan K, Huber C, Watts A, Olendraite I, Snijder J, Wijnant KN, Bonvin A, Martres P, Behillil S, Ayouba A, Maidadi MF, Djomsi DM, Godwe C, Butel C, Simaitis A, Gabrielaite M, Katenaite M, Norvilas R, Raugaite L, Koyaweda GW, Kandou JK, Jonikas R, Nasvytiene I, Zemeckiene Z, Gecys D, Tamusauskaite K, Norkiene M, Vasiliunaite E, Ziogiene D, Timinskas A, Sukys M, Sarauskas M, Alzbutas G, Aziza AA, Lusamaki EK, Cigolo JM, Mawete FM, Lofiko EL, Kingebeni PM, Tamfum JM, et al. 2021. Emergence and spread of SARS-CoV-2 lineage B.1.620 with variant of concern-like mutations and deletions. Nat Commun 12:5769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karim SSA, Karim QA. 2021. Omicron SARS-CoV-2 variant: a new chapter in the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 398:2126–2128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou Y, Zhi H, Teng Y. 2022. The outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron lineages, immune escape and vaccine effectivity. J Med Virol doi: 10.1002/jmv.28138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharif N, Alzahrani KJ, Ahmed SN, Khan A, Banjer HJ, Alzahrani FM, Parvez AK, Dey SK. 2022. Genomic surveillance, evolution and global transmission of SARS-CoV-2 during 2019–2022. PLoS One 17:e0271074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walensky RP, Walke HT, Fauci AS. 2021. SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Concern in the United States-Challenges and Opportunities. JAMA 325:1037–1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brimacombe KR, Zhao T, Eastman RT, Hu X, Wang K, Backus M, Baljinnyam B, Chen CZ, Chen L, Eicher T, Ferrer M, Fu Y, Gorshkov K, Guo H, Hanson QM, Itkin Z, Kales SC, Klumpp-Thomas C, Lee EM, Michael S, Mierzwa T, Patt A, Pradhan M, Renn A, Shinn P, Shrimp JH, Viraktamath A, Wilson KM, Xu M, Zakharov AV, Zhu W, Zheng W, Simeonov A, Mathe EA, Lo DC, Hall MD, Shen M. 2020. An OpenData portal to share COVID-19 drug repurposing data in real time. bioRxiv doi: 10.1101/2020.06.04.135046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chivero ET, Bhattarai N, Rydze RT, Winters MA, Holodniy M, Stapleton JT. 2014. Human pegivirus RNA is found in multiple blood mononuclear cells in vivo and serum-derived viral RNA-containing particles are infectious in vitro. J Gen Virol 95:1307–1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Remsik J, Wilcox JA, Babady NE, McMillen TA, Vachha BA, Halpern NA, Dhawan V, Rosenblum M, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Avila EK, Santomasso B, Boire A. 2021. Inflammatory Leptomeningeal Cytokines Mediate COVID-19 Neurologic Symptoms in Cancer Patients. Cancer Cell 39:276–283 e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Merrill AE, Jackson JB, Ehlers A, Voss D, Krasowski MD. 2020. Head-to-Head Comparison of Two SARS-CoV-2 Serology Assays. J Appl Lab Med 5:1351–1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lukaszuk K, Kiewisz J, Rozanska K, Podolak A, Jakiel G, Woclawek-Potocka I, Rabalski L, Lukaszuk A. 2021. Is WHO international standard for anti-SARS-CoV-2 immunoglobulin clinically useful? medRxiv doi: 10.1101/2021.04.29.21256246. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Welch JL, Xiang J, Chang Q, Houtman JCD, Stapleton JT. 2022. T-Cell Expression of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 and Binding of Severe Acute Respiratory Coronavirus 2. J Infect Dis 225:810–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cameroni E, Bowen JE, Rosen LE, Saliba C, Zepeda SK, Culap K, Pinto D, VanBlargan LA, De Marco A, di Iulio J, Zatta F, Kaiser H, Noack J, Farhat N, Czudnochowski N, Havenar-Daughton C, Sprouse KR, Dillen JR, Powell AE, Chen A, Maher C, Yin L, Sun D, Soriaga L, Bassi J, Silacci-Fregni C, Gustafsson C, Franko NM, Logue J, Iqbal NT, Mazzitelli I, Geffner J, Grifantini R, Chu H, Gori A, Riva A, Giannini O, Ceschi A, Ferrari P, Cippa PE, Franzetti-Pellanda A, Garzoni C, Halfmann PJ, Kawaoka Y, Hebner C, Purcell LA, Piccoli L, Pizzuto MS, Walls AC, Diamond MS, et al. 2021. Broadly neutralizing antibodies overcome SARS-CoV-2 Omicron antigenic shift. Nature doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04386-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu M, Pradhan M, Gorshkov K, Petersen JD, Shen M, Guo H, Zhu W, Klumpp-Thomas C, Michael S, Itkin M, Itkin Z, Straus MR, Zimmerberg J, Zheng W, Whittaker GR, Chen CZ. 2022. A high throughput screening assay for inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 pseudotyped particle entry. SLAS Discov 27:86–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neerukonda SN, Vassell R, Herrup R, Liu S, Wang T, Takeda K, Yang Y, Lin TL, Wang W, Weiss CD. 2021. Establishment of a well-characterized SARS-CoV-2 lentiviral pseudovirus neutralization assay using 293T cells with stable expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2. PLoS One 16:e0248348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heinz FX, Stiasny K. 2021. Distinguishing features of current COVID-19 vaccines: knowns and unknowns of antigen presentation and modes of action. NPJ Vaccines 6:104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miyamoto S, Arashiro T, Adachi Y, Moriyama S, Kinoshita H, Kanno T, Saito S, Katano H, Iida S, Ainai A, Kotaki R, Yamada S, Kuroda Y, Yamamoto T, Ishijima K, Park E-S, Inoue Y, Kaku Y, Tobiume M, Iwata-Yoshikawa N, Shiwa-Sudo N, Tokunaga K, Ozono S, Hemmi T, Ueno A, Kishida N, Watanabe S, Nojima K, Seki Y, Mizukami T, Hasegawa H, Ebihara H, Maeda K, Fukushi S, Takahashi Y, Suzuki T. 2022. Vaccination-infection interval determines cross-neutralization potency to SARS-CoV-2 Omicron 2 after breakthrough infection by other variants medRxiv doi: 10.1101/2021.12.28.21268481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deng W, Sweeney R 2022. Intramuscular injection of a mixture of COVID-19 peptide vaccine and tetanus vaccine in horse induced neutralizing antibodies against authentic virus of SARS-CoV-2 Delta Variant. SSRN doi: 10.2139/ssrn.4124253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sheward DJ, Kim C, Ehling RA, Pankow A, Castro Dopico X, Dyrdak R, Martin DP, Reddy ST, Dillner J, Karlsson Hedestam GB, Albert J, Murrell B. 2022. Neutralisation sensitivity of the SARS-CoV-2 omicron (B.1.1.529) variant: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Infect Dis 22:813–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stapleton JT. 2021. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Antibody Testing: Important but Imperfect. Clin Infect Dis 73:e3074–e3076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coussens NP, Sittampalam GS, Guha R, Brimacombe K, Grossman A, Chung TDY, Weidner JR, Riss T, Trask OJ, Auld D, Dahlin JL, Devanaryan V, Foley TL, McGee J, Kahl SD, Kales SC, Arkin M, Baell J, Bejcek B, Gal-Edd N, Glicksman M, Haas JV, Iversen PW, Hoeppner M, Lathrop S, Sayers E, Liu H, Trawick B, McVey J, Lemmon VP, Li Z, McManus O, Minor L, Napper A, Wildey MJ, Pacifici R, Chin WW, Xia M, Xu X, Lal-Nag M, Hall MD, Michael S, Inglese J, Simeonov A, Austin CP. 2018. Assay Guidance Manual: Quantitative Biology and Pharmacology in Preclinical Drug Discovery. Clin Transl Sci 11:461–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]