Abstract

We compared the fidelity of wild-type human immunodeficiency virus type-1 (HIV-1) reverse transcriptase (RT) and two RT mutants, Y115F and Y115V. Although neither mutation had a large effect on the overall fidelity of the enzyme, both mutations altered the spectrum of mutations and the precise nature of the mutational hot spots. The effects of Y115V were greater than those of Y115F. When we compared the behavior of the wild-type enzyme with published data, we found that, in contrast to what has been published, misalignment/slippage could account for only a small fraction of the mutations we observed. We also found that a preponderance of the mutations (both transitions and transversions) resulted in the insertion of an A. Because we were measuring DNA-dependent DNA synthesis (plus-strand synthesis), this bias could contribute to the A-rich nature of the HIV-1 genome.

The replication of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) genome is error prone, giving rise to genetic variation. This genetic variation is important both for the ability of the virus to evade the host's immune system and for the emergence of drug-resistant variants. There are three steps in the viral life cycle in which mutations can occur: (i) when an infected cell divides, the proviral form of the viral genome is copied by the host's DNA replication machinery; (ii) when the virus is produced by an infected cell, the RNA genome of the virus is generated by the host's DNA-dependent RNA polymerase; and (iii) when the virus infects a cell, viral reverse transcriptase (RT) converts the RNA genome of the virus into DNA. The overall error rate for this process is relatively high (about 10−4 errors/bp in a single replication cycle); however, the relative contributions of the various steps and enzymes to this overall error rate are not known (see reference 23 for a review). It is likely that the host's DNA-dependent DNA polymerase, which has a high fidelity and an associated proofreading function, does not make a major contribution to the error rate in situations in which the virus is actively replicating. However, the relative roles played by RT and the host's DNA-dependent RNA polymerase in the generation of mutations are unclear.

One way to approach this problem is to study the fidelity of RT in vitro. Both biochemical and genetic approaches have been used to measure RT fidelity. Biochemical approaches involve mispair extension assays or assays measuring misincorporation on either a homopolymeric or a defined heteropolymeric template (18, 19, 26). Genetic fidelity approaches involve copying a DNA or RNA segment encoding an activity that can be conveniently assayed in vivo (usually, but not always, the segment encoding the α-complementing peptide of Escherichia coli β-galactosidase). In such genetic fidelity assays, the segment is copied in vitro and incorporated into a plasmid or the genome of a bacteriophage (or phagemid), usually an M13 derivative, and mutations are scored after transformation of a suitable E. coli host (see reference 6 for review).

Genetic assays have several advantages. They are not appreciably affected by the purity of individual deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) stocks which can be an important issue in certain biochemical fidelity assays. Furthermore, unlike mispair extension assays, genetic fidelity assays use normal polymerase substrates in which the template primer is fully base paired and all four dNTPs are present at normal concentrations. These advantages do not mean, however, that genetic fidelity assays are without problems. The E. coli host can make unwanted contributions to a genetic fidelity assay. Fortunately, the error rate for the host DNA replication machinery is low enough relative to the error rate of RT that the E. coli machinery does not significantly increase the overall mutation frequency for RT. If both the strand that has been copied in vitro and a complementary strand are introduced into E. coli, mutations generated by RT in vitro can be corrected against the complementary strand by the mismatch repair machinery of the bacterial host. If the two strands are corrected against each other with equal efficiency, the error rate is underestimated by a factor of 2. This outcome is not optimal but has a relatively modest effect on the measured error rate. However, if the segment generated in vitro by the DNA polymerase whose fidelity is being tested is introduced into a plasmid or viral genome in a way that leaves a nick on the strand synthesized in vitro, the presence of the nick can bias the mismatch repair. The E. coli repair machinery can selectively degrade the nicked strand and thus can correct the strand made in vitro against the intact strand, which can affect the error rate to a much greater extent.

After looking carefully at the available genetic assays for fidelity, we made modifications to the published procedures to try to minimize the problems associated with E. coli mismatch repair. The DNA segment that is used as a template for in vitro DNA synthesis is obtained from a Dut− Ung− strain, so that the template contains some deoxyuracil. In our modified assay, after the DNA segment is copied in vitro, it is cleaved with restriction enzymes, gel purified, and ligated to an appropriately cleaved plasmid. This ligated DNA is reintroduced into a strain of E. coli that will degrade uracil-containing DNA (U-DNA), ensuring that the strand created in vitro by RT is preserved.

We used this assay to measure the fidelity of wild-type HIV-1 RT and HIV-1 RTs with mutations at position 115, which is part of the dNTP-binding site (9, 10, 13). The two mutants studied, Y115F and Y115V, have overall error rates similar to the error rate for the wild-type enzyme. However, the spectrum of mutations made by the mutant RTs differs from the spectrum of mutations generated by the wild-type enzyme.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

Litmus 29 was obtained from New England BioLabs. The plasmid contains an M13 origin of replication and a restriction enzyme recognition site polylinker, including a recognition site for BamHI, 5′ of the coding region for the LacZα-complementing fragment. Litmus 29 was linearized with HpaI, ligated to NotI linkers (New England BioLabs), and recircularized to make Litmus 29 (Not). The new NotI recognition sequence is located 3′ of the lacZα-coding region.

Formation of single-strand uracil-containing DNA.

The construct Litmus 29 (Not) was introduced into the Dut− Ung− male E. coli strain CJ236 (New England BioLabs). This bacterial strain will introduce deoxyuracil residues into the plasmid DNA during replication. To generate single-stranded U-DNA Litmus 29 (Not), the helper phage M13K07 (New England BioLabs) was used according to the protocol suggested by New England BioLabs. In brief, 50 ml of Luria-Bertani medium supplemented with uridine (0.25 μg/ml) was inoculated with a colony of Litmus 29 (Not) in CJ236. The culture was incubated at 37°C with agitation until the solution was slightly turbid. The helper phage M13K07 was added to a final concentration of 108 PFU/ml. The culture was incubated at 37°C with agitation for an additional 60 min. Kanamycin was added to a final concentration of 70 μg/ml, and the culture was incubated overnight at 37°C.

Bacteria were removed by sedimentation twice at 8,000 rpm for 10 min. One-fifth volume of 2.5 M NaCl–20% PEG (polyethylene glycol) 6000-8000 (NaCl-PEG) was added to the supernatant, and the solution was incubated on ice for 2 h. The phage particles were isolated by centrifugation at 8,000 rpm for 10 min. The pellet was resuspended in 1.6 ml of 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0)–1.0 mM EDTA (TE) and divided into two tubes. The solution was cleared by centrifugation in a microcentrifuge at full speed to remove any trace of bacteria. MgCl2 was added to a final concentration of 10 mM, and DNase was added to the solution to remove both contaminating bacterial and double-stranded phage DNA released by bacterial lysis. Intact phage particles were isolated by the addition of 200 μl of NaCl-PEG solution to each tube and centrifugation in a microcentrifuge for 5 min at full speed. The phage pellet was resuspended in 300 μl of TE and extracted three times with phenol-chloroform. After the addition of NaCl to a final concentration of 50 mM, the phage DNA was precipitated with 1 volume of isopropanol, then resuspended in 400 μl of H2O, and stored at −20°C.

Fidelity assay.

The fidelity primer (5′ CCC ATG GTG AAG CTT GGA TCC ACG ATA TCC TGC AGG 3′; Life Technologies, Inc., Rockville, Md.) matches the sequence surrounding the BamHI recognition site in the Litmus 29 polylinker. For each fidelity assay, 2.5 μl from a 10.0-A260/ml stock of fidelity primer was annealed to 1.0 μg of single-stranded U-DNA (described above) by heating and slow cooling. Each sample was adjusted to consist of 25 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 75 mM KCl, 8.0 mM MgCl2, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 100 μg of bovine serum albumin per ml, 10 mM CHAPS {3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate}, and 20 μM each dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP. One microgram of either wild-type HIV-1 RT or the Y115F mutant was added, and the samples were incubated for 15, 20, or 30 min at 37°C. For Y115V, which is less processive than wild-type RT (18), longer incubation times (20, 30, or 45 min) were used. The reactions were stopped by the addition of 1 volume of phenol-chloroform, followed by isopropanol precipitation and a 70% ethanol wash. The extended template primers were digested with BamHI and NotI, and the resulting fragments were fractionated on a 2% SeaPlaque (FMC) low-melting-point agarose gel. If the wild-type or variant RT copied the lacZα portion of the template past the NotI recognition sequence, a band approximately 300 bp in size was visible in the gel. Primers that were not extended past the NotI site were annealed to phage DNA that was linearized with BamHI which migrated near the top of the gel. The BamHI/NotI fragment encoding LacZα was isolated from the gel and purified.

As described above, Litmus 29 (Not) contains a fully functional LacZα-coding region. Attempting to remove this fragment and replace it with the BamHI/NotI fragment generated by HIV-1 RT could lead to a high-background problem that would not be easily detected. Therefore, Litmus 29 (Not) was linearized with BamHI/NotI and ligated to a 1.7-kb fragment containing the coding region from HIV-1 RT and small flanking sequences to yield the construct B/N RT (His). The LacZα-coding region was completely removed from this vector. B/N RT (His) was linearized with BamHI and NotI, and the vector band was isolated from a 2% SeaPlaque low-melting-point agarose gel. This DNA segment was then ligated to the BamHI/NotI lacZα fragments described above. The ligation mixture was transformed into E. coli DH5α (Life Technologies, Inc.) and plated on NZY (10.0 g of NZ amine, 5.0 g of NaCl, 5.0 g of yeast extract, and 2.0 g of MgSO4 per liter)-ampicillin plates supplemented with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal; Life Technologies). The dark blue, light blue, and white colonies were then counted.

DNA was isolated from the light blue and white colonies and tested by digestion with BamHI and NotI. Contaminating B/N RT (His) colonies were easily distinguished since plasmid DNA isolated from these colonies contained a 1.7-kb insert that was much larger than the approximately 300-bp lacZα insert. The remaining clones were then sequenced to determine the nature of the mutation.

RESULTS

Fidelity assay.

The fidelity assay that we have used involves the copying of a DNA segment that encodes the α-complementing peptide of E. coli β-galactosidase. As described in Materials and Methods, single-stranded template DNA from Litmus 29 (Not) was isolated from a Dut− Ung− E. coli strain. In such strains, deoxyuracil is incorporated into DNA. The template U-DNA was hybridized to a primer, which was extended in vitro by either the wild-type or mutant HIV-1 RT so that the DNA segment encoding the α-complementing peptide was copied. The resulting double-stranded DNA was digested, and the fragment containing the LacZα coding region was ligated to a plasmid and introduced into a Dut+ Ung+ E. coli strain, which ensures that the template DNA strand is preferentially degraded and that the DNA strand synthesized in vitro by HIV-1 RT is preferentially retained and copied, giving rise to the plasmids subsequently isolated from individual colonies. The transformed E. coli was grown on plates containing an indicator for β-galactosidase activity (X-Gal). Colonies that were either white or light blue were counted and grown up, and the plasmids were recovered. Segments encoding the LacZα peptide were sequenced (Materials and Methods). Since a percentage of mutations will be silent, this method necessarily underestimates the actual error rate. However, when RT copies the viral genome, a percentage of the mutations will also be silent. In addition, copying the lacZα-complementing DNA has been used by others to examine both the frequency of errors made by HIV-1 RT and the precise nature of the mutations.

The lacZα RNA transcript from Litmus 29 (Not) encodes a fusion protein. The LacZα peptide is the C-terminal part of the fusion protein; the N terminus, which makes no functional contribution to LacZα activity, is derived from the polylinker. A small part of the N-terminal region of this fusion protein is encoded with the NotI/BamHI fragment generated in vitro by RT. Because this region does not encode a functional part of LacZα, only mutations that create termination codons or frameshift mutations will be detected, potentially skewing the results. Therefore, we scored only mutations within the 174-bp region from the glycine codon GGA, which is the junction point between lacZα and the polylinker and the first termination codon at the end of lacZα.

Wild-type HIV-1 RT.

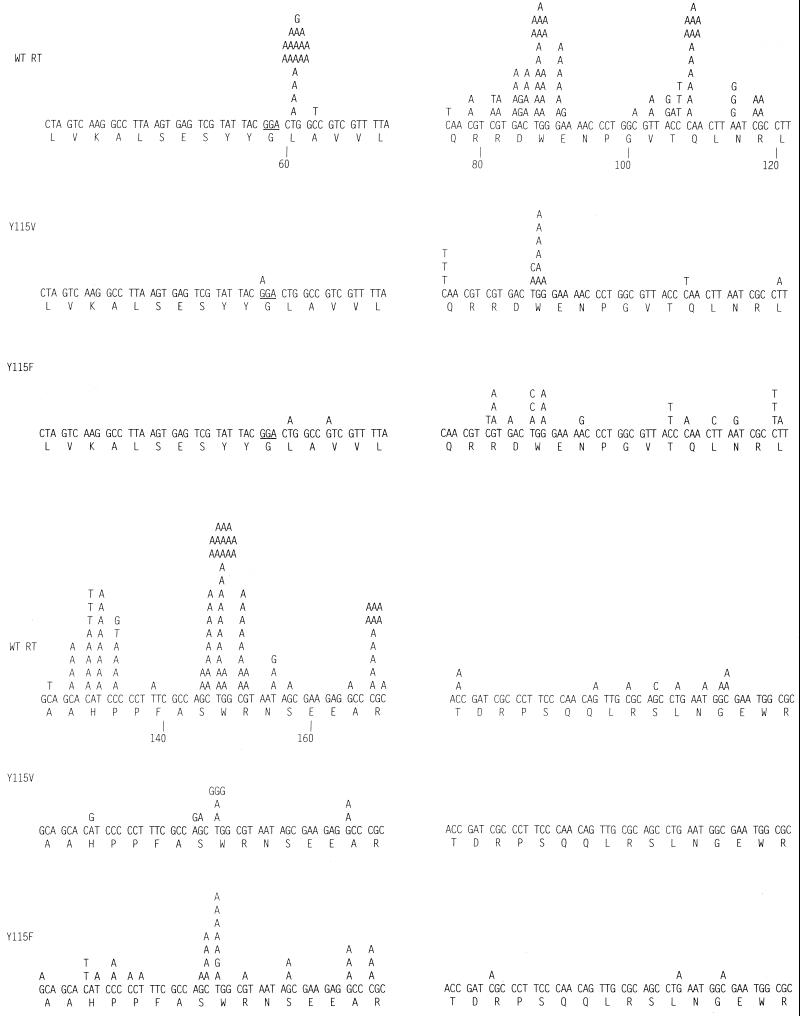

To facilitate a comparison of our results and those obtained by others, we first analyzed wild-type HIV-1 RT (Fig. 1 and 2; Tables 1 and 2). The overall measured error rate of 1.6 × 10−4 mutations/bp is within the range others have reported (3–8, 11, 21; see reference 23 for a review). Of 222 total mutations analyzed, 49 (22%) were transitions, 140 (63%) were transversions, and 33 (15%) were frameshifts (Table 2). Among the transitions and transversions, the majority of the mutations involved changes in which the base introduced into the sequence was an A (Table 3; Fig. 1). Of the missense mutations generated by wild-type HIV-1 RT, 88% (166 of 189) involved the replacement of another base with an A (Table 3). If this reflects what happens during plus-strand DNA synthesis in vivo (the step in which RT copies a DNA strand), it might help to account for the fact that the HIV-1 genome is A rich (see Discussion).

FIG. 1.

Comparison of missense mutations generated by wild-type HIV-1 RT and variants Y115V and Y115F. The numbering system under the coding sequence is taken from the system used by other groups (3) to allow easier comparison of their results and ours. The underlined GGA codon (glycine) indicates the point in the fusion protein between the coding sequence of the polylinker region and the start of the lacZα coding region. Some silent mutations (which do not alter the protein sequence, e.g., at position 101 in the wild-type HIV-1 RT mutation set) were detected and were invariably linked to another mutation that did alter the protein sequence. These silent changes were considered as part of the mutation frequency.

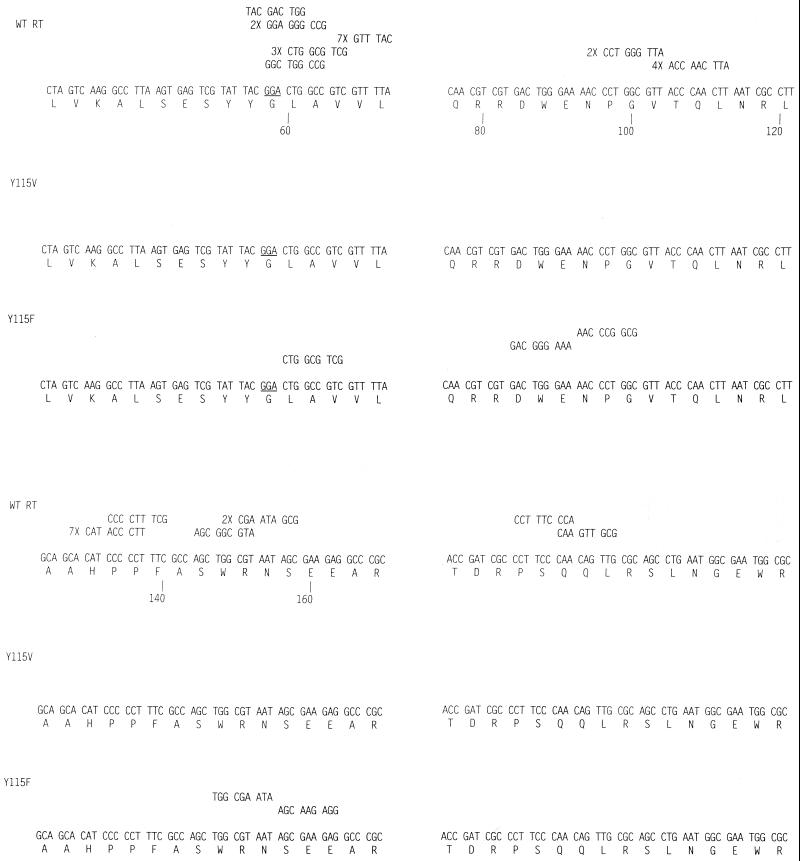

FIG. 2.

Comparison of frameshift mutations generated by wild-type HIV-1 RT and variant Y115F (Y115V did not generate any frameshift mutations).

TABLE 1.

Mutation frequencies and error rates of wild-type HIV-1 RT and variants Y115F and Y115Va

| RT | Total no. of mutations | Total no. of colonies | Mutation frequency | Error rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 222 | 7,990 | 278 × 10−4 | 1.6 × 10−4 |

| Y115F | 60 | 3,429 | 175 × 10−4 | 1.0 × 10−4 |

| Y115V | 25 | 3,041 | 82 × 10−4 | 4.7 × 10−5 |

Mutation frequency is the number of mutations detected during sequencing (including silent changes) divided by the total number of colonies screened. Error rate is the mutation frequency divided by the size of the target (in this case, the 174-bp lacZα coding region).

TABLE 2.

Frequency of missense mutations (transversions and transitions) and frameshift mutations of wild-type HIV-1 RT and the variants Y115F and Y115V

| RT | No. of missense mutations/no. of total mutations (%)

|

Absolute error rate

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transition | Transversion | Frameshifts | Transition | Transversion | Frameshifts | |

| Wild type | 49/222 (22) | 140/222 (63) | 33/222 (15) | 3.5 × 10−5 | 1 × 10−4 | 2.4 × 10−5 |

| Y115F | 29/60 (48) | 26/60 (43) | 5/60 (8) | 4.8 × 10−5 | 4.3 × 10−5 | 8 × 10−6 |

| Y115V | 19/25 (76) | 6/25 (24) | None | 3.5 × 10−5 | 1.1 × 10−5 | |

TABLE 3.

Spectrum of missense mutations generated by wild-type HIV-1 RT and variants Y115V and Y115F

| RT | Transitions

|

Transversions

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | No. | Type | No. | |

| Wild type | G→A | 28 | C→A | 70 |

| C→T | 11 | T→A | 68 | |

| A→G | 8 | T→G | 2 | |

| C→G | 1 | |||

| G→C | 1 | |||

| Y115F | G→A | 15 | C→A | 13 |

| C→T | 9 | T→A | 12 | |

| A→G | 2 | T→G | 1 | |

| T→C | 3 | |||

| Y115V | G→A | 12 | T→A | 3 |

| C→T | 4 | T→G | 3 | |

| A→G | 2 | |||

| T→C | 1 | |||

It has been suggested that misalignment/slippage at a homopolymeric stretch can account for hot spots where missense mutations occur at high frequency (3, 4, 16, 17). We found a number of hot spots for missense mutations; however, in most cases, these hot spots were not associated with homopolymeric regions in ways that would suggest that misalignment/slippage during synthesis could account for the observed mutations. There were two possible exceptions to this general observation (positions 90 and 108); however, the mutations at these two hot spots accounted for only about 10% of the total missense mutations. (There are 6 mutations at 90 and 13 at 108, i.e., 19 of a total of 189 missense mutations.) This finding suggests that in our system, other mechanisms are more important than misalignment/slippage in the generation of missense mutations. In contrast, most of the frameshift mutations were associated with homopolymeric stretches (if one counts two bases in a row as a short homopolymeric stretch) in a way that suggests the frameshift mutations we found can be explained by a misalignment/slippage mechanism.

Fidelity of the Y115F mutant.

Position 115 is part of the dNTP-binding pocket. In RTs from lentiviruses, the amino acid at this position is Y; in most other retroviral RTs, the amino acid at the equivalent position is F. In the case of HIV-1, the Y115F mutation is associated with low levels of resistance to the nucleotide analog 1592U89 (24). The change from Y to F at position 115 causes the loss of a hydroxyl group; however, the phenyl ring is preserved. The overall error rate for Y115F is 1.0 × 10−4/bp, which is slightly lower than the overall error rate of the wild-type enzyme (1.6 × 10−4/bp). We have compared the types of errors made by the wild-type and mutant enzymes in two ways: by calculating, for each class of mutations, the percentage of total errors and the absolute frequencies they represent (Table 2). Y115F makes a higher percentage of transitions (48%) and a lower percentage of transitions (48%) and a lower percentage of transversions and frameshifts (43 and 8%) than wild-type RT (43 and 8%). However, it may be more useful to compare absolute error rate for the two enzymes. This makes it clear that Y115F makes slightly more transitions than wild-type RT (4.8 × 10−5 versus 3.5 × 10−5); however, the real difference is in the numbers of transitions and frameshifts. Again, for the missense mutations, substitutions of A predominates (Table 3). This is a slightly lower percentage of A substitutions than for the wild type (73% versus 88%). Direct comparison of mutations obtained with Y115F to those made by wild-type RT revealed that there were hot spots for mutations with the wild-type enzyme (for example, positions 61, 87, 90, 108, 129, 131, 133, and 150) that are not hot spots for Y115F (Fig. 1). Two of these, 90 and 108, are positions where the mutations could be explained by a misalignment/slippage mechanism, suggesting that Y115F may be less prone to this type of error than the wild-type enzyme. Consistent with such an interpretation, the absolute rate of frameshift errors is reduced about threefold (from 2.4 × 10−5 to 8 × 10−6).

Fidelity of the Y115V mutant.

As might be expected, the pattern of mutations generated by the Y115V mutant differs from that of the wild-type enzyme to a greater degree than does the pattern generated by Y115F. The overall mutation rate for Y115V is lower (4.7 × 10−5 [Table 1]), and transitions are the most common type of mutation (19/25 [76%] [Table 2]). The remaining mutations are all transversions (6/25 [24%] [Table 3]); no frameshifts were seen in the sample we analyzed. Because the overall fidelity of Y115V is higher than that of wild-type HIV-1 RT, it is also useful to compare the absolute error frequencies. The rate of transitions is the same as for wild-type RT (3.5 × 10−5); however, the rate of transversions is almost an order of magnitude lower (1.0 × 10−4 for wild-type RT, 1.1 × 10−5 for Y115V). A substitution is still the most common type of missense mutation (15/25 [76%]); however, the pattern of mutational hot spots is different from that seen with either Y115F or wild-type HIV-1 RT (Fig. 1). At one of the sites that is a hot spot for Y115V (position 147), some, but not all, of the changes could be accounted for by a misalignment/slippage mechanism.

DISCUSSION

We chose to use the DNA segment encoding the α-complementing fragment of E. coli β-galactosidase because it is a convenient target and because it has been used by others, making it possible to directly compare our results with those already published. We modified the system to avoid bias in strand repair in E. coli that could preferentially cause degradation of the DNA strand synthesized by HIV-1 RT. The overall mutation rate that we measured for wild-type HIV-1 RT (1.6 × 10−4) is not dramatically different from what has been reported in the literature (reviewed in reference 23). However, when the mutations are examined directly, it is clear that our data differ substantially from what has been published.

Although we found hot spots in the lacZα sequence where mutations arise frequently, these hot spots are not the same as those reported previously. The spectrum of mutations that we observed is also different. Perhaps this difference is not surprising—two laboratories that both used the same assay reported relatively different patterns of mutations (4, 11). We found more transversions and fewer frameshifts than have been reported previously. It has been suggested that a large fraction of the errors made by wild-type HIV-1 RT in vitro (both missense and frameshift) involve misalignment/slippage followed by DNA synthesis (3, 4, 16, 17). Although we found some missense mutations that can be explained by such a mechanism, they represent a relatively small percentage of the total. In contrast, the majority of the frameshift mutations can be explained by a misalignment/slippage mechanism; however, we found that wild-type HIV-1 RT makes a lower percentage of frameshift mutations than has been reported earlier (3, 4), and the two mutant enzymes that we have tested produce fewer frameshift mutations than does wild-type HIV-1 RT.

We do not have a simple explanation for these differences. We made changes in the assay that were intended to prevent the E. coli mismatch machinery from correcting errors introduced by HIV-1 RT. However, the differences between our results and those reported previously are not so much in the frequency of mutation as in the exact nature of the mutations obtained.

In addition to the changes that we introduced to make the assay more reliable, we used a heterodimeric form of HIV-1 RT. Although most of the original work with genetic assays was done with homodimeric HIV-1 RT (1, 17, 22), it was reported that experiments done with heterodimeric RT obtained from virions gave results similar to those obtained with recombinant HIV-1 RT (3, 8, 22). This finding suggests that the explanation of the differences in the results lies in the differences in the assays. We considered the possibility that uracil in the template DNA strand would be mutagenic; however, this should give rise to an increase in error rate and, more specifically, to G→A transitions. We did find some G→A transitions, but these were not the most common mutations. Comparison of the data obtained with the two RT mutants to results obtained with wild-type HIV-1 RT showed that there are no hot spots in common at which the predominant mutation is G→A.

The most striking aspect of our results is the high percentage of mutations in which an A is substituted for another base in both transitions and transversions. The template that we have used is not particularly T rich; however, the product strand would become A rich if it were repeatedly copied using a polymerase that preferentially inserted A's for other bases. As mentioned in Results, the genome of HIV-1 is A rich. If, during reverse transcription in vivo, RT in the DNA-dependent DNA synthesis mode (copying minus-strand DNA, synthesizing plus-strand DNA) preferentially substitutes A's for other bases, this could introduce A's into the HIV-1 genome.

During viral replication in vivo, any errors made during plus-strand synthesis could be corrected by the DNA repair machinery of the host. However, there is no reason to expect that the host machinery could distinguish the viral strands; it seems reasonable to expect that there is an equal probability that the minus strand would be corrected based on the plus-strand sequence as for a correction in the opposite direction. This suggests, even if there is extensive mismatch correction, that the host DNA repair machinery would be expected to reduce the number of plus-strand mutations by no more than half. There are also other mechanisms which may make significant contributions to the A-rich nature of the HIV-1 genome. For example, it has been suggested that imbalances in the dNTP pools leads to G→A hypermutations (25); this could also contribute to an A-rich genome.

If the bias for substituting A's for other bases also occurs when RT copies the RNA genome, it would give rise to a T-rich genome. The error rate for HIV-1 RT copying an RNA polymerase generated RNA template has been measured (7, 8, 14, 15). However, the overall frequency measured in such experiments is a combination of two error rates: the error rate of the RT using the RNA template and the error rate of the DNA-dependent RNA polymerase used to generate the RNA template. Until the error rate of DNA-dependent RNA polymerases can be accurately measured, it will not be easy to determine how accurately RT copies an RNA template compared with a DNA template.

Comparing the results that we obtained with wild-type HIV-1 RT and the two mutants, Y115F and Y115V, the most striking differences are not in the rate of mutation but in the spectrum of mutations that were obtained and in the hot spots. Y115F is perhaps 1.5- to 2-fold less error prone than wild-type HIV-1 RT, and Y115V is 3- to 4-fold less error prone than wild-type HIV-1 RT; however, the major differences are in the nature of the mutations that were obtained. Both Y115F and Y115V make fewer frameshift errors than does the wild-type enzyme; both mutant enzymes seem less prone to make errors that involve a misalignment/slippage mechanism. Both make about as many transition errors as the wild-type enzyme but are less prone to make transversion errors.

We were especially interested in the fidelity of Y115V. Both the Y115V mutant of HIV-1 RT and the corresponding F155V mutant of murine leukemia virus (MLV) RT can incorporate UTP into DNA much more efficiently than the corresponding wild-type enzymes (9, 12). This raises a question: does this ability to incorporate ribonucleotides reflect a specific or a general change in enzyme specificity? Furthermore, does this change in the ability of the enzyme(s) to distinguish dNTPs and NTPs extend to an inability of the enzyme(s) to properly distinguish the individual dNTPs? It has been argued that the change in the F155V mutant of MLV RT specifically alters a “gate” that blocks the incorporation of ribonucleotides, which would not necessarily imply a loss of fidelity. However, there is a complex array of changes in the enzymatic properties of Y115V that are not all easily explained by a simple gate model (9). Moreover, some of the properties of the Y115V mutant of HIV-1 RT and the F155V mutant of MLV RT appear to be different (9, 12).

Previous reports on the fidelity of Y115 mutants were based either on a biochemical measure of misinsertion (Y115F) (18) or on mispair extension (Y115F and Y115V) (19). Both Y115F and Y115V were reported to be more error prone than the wild-type enzyme; in the mispair extension assay, Y115V had a lower fidelity than Y115F (19). Although mispair extension is a component of fidelity, it does not provide a measure of misincorporation but only a measure of the ability to extend a mispaired end. Moreover, recent reports have shown that HIV-1 RT can remove the 3′ terminus of a primer. This process involves the reversal of the normal polymerization reaction and can proceed with either pyrophosphate or an NTP acting as a pyrophosphate donor (2, 20). It is possible that this reaction can also proceed with a dNTP as a pyrophosphate donor, and the mispair extension assays may, in some cases, be affected by the ability of RT (either wild type or mutant) to carry out this unblocking reaction and then extend the primer. However, the concentrations of NTPs necessary for this reaction to be efficient are relatively high (millimolar), so the contribution of this mechanism to the standard mispair extension assays may be small.

Both the published data on the fidelity of Y115F and Y115V and our data suggest that the overall change in fidelity is relatively small. However, our data also show, despite a modest change in fidelity, that these two amino acid substitutions have a much more dramatic effect on the type(s) of errors. In this way, the effects of the Y115V mutant on fidelity are somewhat similar to the effects on fidelity of mutating another amino acid that is part of the dNTP-binding site of HIV-1 RT, M184. Substitution of the methionine at position 184 with I or V has a relatively modest effect on the overall error rate (∼4-fold) but a much greater effect on the spectrum of mutations that are obtained (11). Another mutation at the dNTP-binding site, Q151, has a modest effect on the spectrum of mutations (21). Taken together, these results suggest that making modest changes in the amino acids that form the dNTP-binding site affects both the types of errors and the precise sequences that are mutational hot spots to a much greater extent than the overall fidelity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Hilda Marusiodis for typing the manuscript, Marilyn Powers for help with the sequencing, and Anne Arthur for expert editorial assistance. We also thank Pat Clark and Peter Frank for purifying wild-type and mutant HIV-1 RT.

This research was sponsored by the National Cancer Institute, DHHS, under contract with ABL, and by NIGMS.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbots J, Bebenek K, Kunkel T A. Mechanism of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Termination of processive synthesis on a natural DNA template is influenced by the sequence of the template-primer stem. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:10312–10323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arion D, Kaushik N, McCormick S, Borkow G, Parniak M A. Phenotypic mechanism of HIV-1 resistance to 3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine (AZT): increased polymerization processivity and enhanced sensitivity to pyrophosphate of the mutant viral reverse transcriptase. Biochemistry. 1998;37:15908–15917. doi: 10.1021/bi981200e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bebenek K, Abbotts J, Roberts J D, Wilson S H, Kunkel T A. Specificity and mechanism of error-prone replication by human immunodeficiency virus-1 reverse transcriptase. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:16948–16956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bebenek K, Abbotts J, Wilson S H, Kunkel T A. Error-prone polymerization by HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Contribution of template-primer misalignment, miscoding, and termination probability to mutational hot spots. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:10324–10334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bebenek K, Beard W A, Casas-Finet J R, Kim H-R, Darden T A, Wilson S H, Kunkel T A. Reduced frameshift fidelity and processivity of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase mutants containing alanine substitutions in helix H of the thumb subdomain. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:19516–19523. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.33.19516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bebenek K, Kunkel T A. Analyzing fidelity of DNA polymerases. Methods Enzymol. 1991;262:217–232. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)62020-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyer J C, Bebenek K, Kunkel T A. Analyzing the fidelity of reverse transcription and transcription. Methods Enzymol. 1996;275:523–537. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)75029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyer J C, Bebenek K, Kunkel T A. Unequal human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase error rates with RNA and DNA templates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:6919–6923. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.15.6919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyer P L, Sarafianos S G, Arnold E, Hughes S H. Analysis of mutations at positions 115 and 116 in the dNTP binding site of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:3056–3061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.7.3056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ding J, Das K, Hsiou Y, Sarafianos S G, Clark A D, Jr, Jacobo-Molina A, Tantillo C, Hughes S H, Arnold E. Structure and functional implications of the polymerase active site region in a complex of HIV-1 RT with a double-stranded DNA template-primer and an antibody Fab fragment at 2.8 Å resolution. J Mol Biol. 1998;284:1095–1111. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drosopoulos W C, Prasad V R. Increased misincorporation fidelity observed for nucleoside analog resistance mutations M184V and E89G in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase does not correlate with the overall error rate measured in vitro. J Virol. 1998;72:4224–4230. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4224-4230.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao G, Orlova M, Georgiadis M M, Hendrickson W A, Goff S P. Conferring RNA polymerase activity to a DNA polymerase: a single residue in reverse transcriptase controls substrate selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:407–411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang H, Chopra R, Verdine G L, Harrison S C. Structure of a covalently trapped catalytic complex of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase: implications for drug resistance. Science. 1998;282:1669–1675. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5394.1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hubner A, Kruhoffer M, Grosse F, Krauss G. Fidelity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase in copying natural RNA. J Mol Biol. 1992;223:595–600. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90975-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ji J, Loeb L A. Fidelity of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase copying RNA in vitro. Biochemistry. 1992;31:954–958. doi: 10.1021/bi00119a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kunkel T A. Misalignment-mediated DNA synthesis errors. Biochemistry. 1990;29:8003–8011. doi: 10.1021/bi00487a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kunkel T A, Soni A. Mutagenesis by transient misalignment. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:14784–14789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin-Hernandez A M, Domingo E, Menendez-Arias L. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase: role of Tyr115 in deoxynucleotide binding and misinsertion fidelity of DNA synthesis. EMBO J. 1996;15:4434–4442. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin-Hernandez A M, Gutierrez-Rivas M, Domingo E, Menendez-Arias L. Mispair extension fidelity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptases with amino acid substitutions affecting Tyr115. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:1383–1389. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.7.1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meyer P R, Matsuura S E, So A G, Scott W A. Unblocking of chain-terminated primer by HIV-1 reverse transcriptase through a nucleotide-dependent mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13471–13476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rezende L F, Curr K, Ueno T, Mitsuya H, Prasad V R. The impact of multidideoxynucleoside resistance-conferring mutations in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase on polymerase fidelity and error specificity. J Virol. 1998;72:2890–2895. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.2890-2895.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roberts J D, Bebenek K, Kunkel T A. The accuracy of reverse transcriptase from HIV-1. Science. 1988;242:1171–1173. doi: 10.1126/science.2460925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Telesnitsky A, Goff S P. Reverse transcription and the generation of retroviral DNA. In: Coffin J M, Hughes S H, Varmus H E, editors. Retroviruses. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 121–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tisdale M, Alnadaf T, Cousens D. Combination of mutations in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase required for resistance to the carbocyclic nucleoside 1592U89. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1094–1098. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vartanian J-P, Plikat U, Henry M, Mahieux R, Guillemot L, Meyerhans A, Wain-Hobson S. HIV genetic variation is directed and restricted by DNA precursor availability. J Mol Biol. 1997;270:139–151. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wainberg M A, Drosopoulos W C, Salomon H, Hsu M, Borkow G, Prniak M, Gu Z, Song Q, Manne J, Islam S, Castriota G, Prasad V R. Enhanced fidelity of 3TC-selected mutant HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Science. 1996;271:1282–1285. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5253.1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]